Soil Ca2SiO4 Supplying Increases Drought Tolerance of Young Arabica Coffee Plants

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

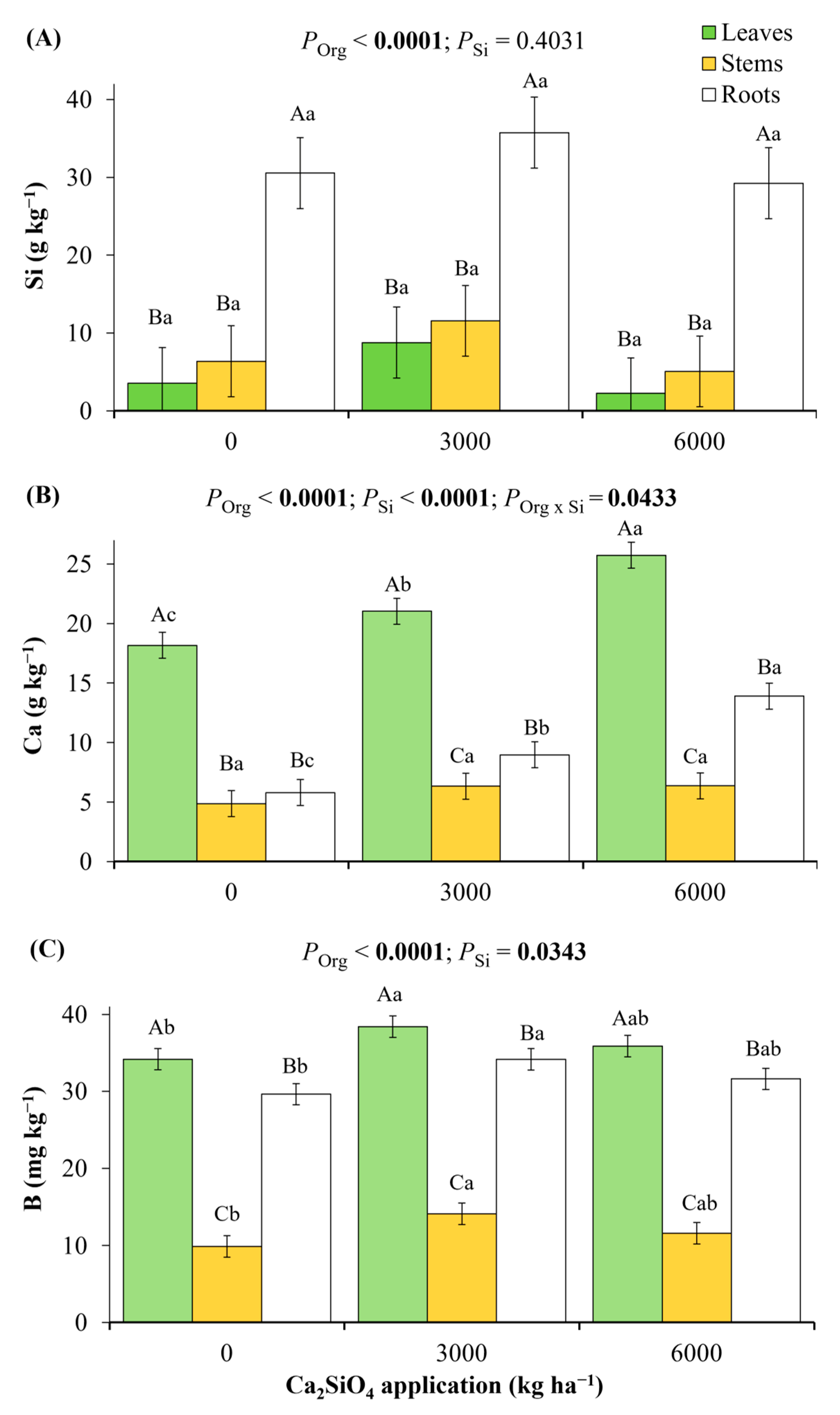

2.1. Nutritional Status in Young Coffee Plants Grown Under Ca2SiO4 Application

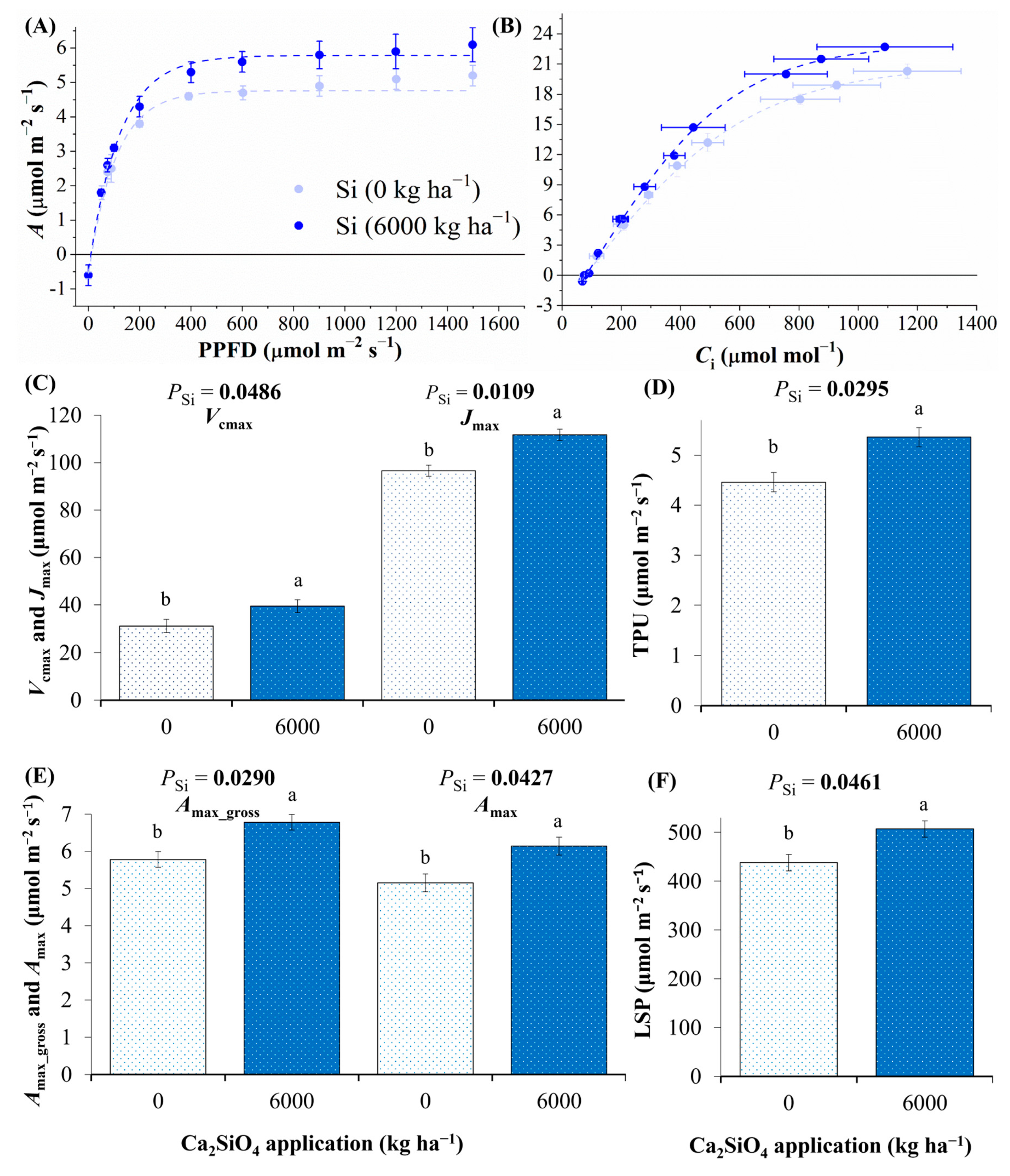

2.2. Photosynthesis as Affected by Ca2SiO4 Application

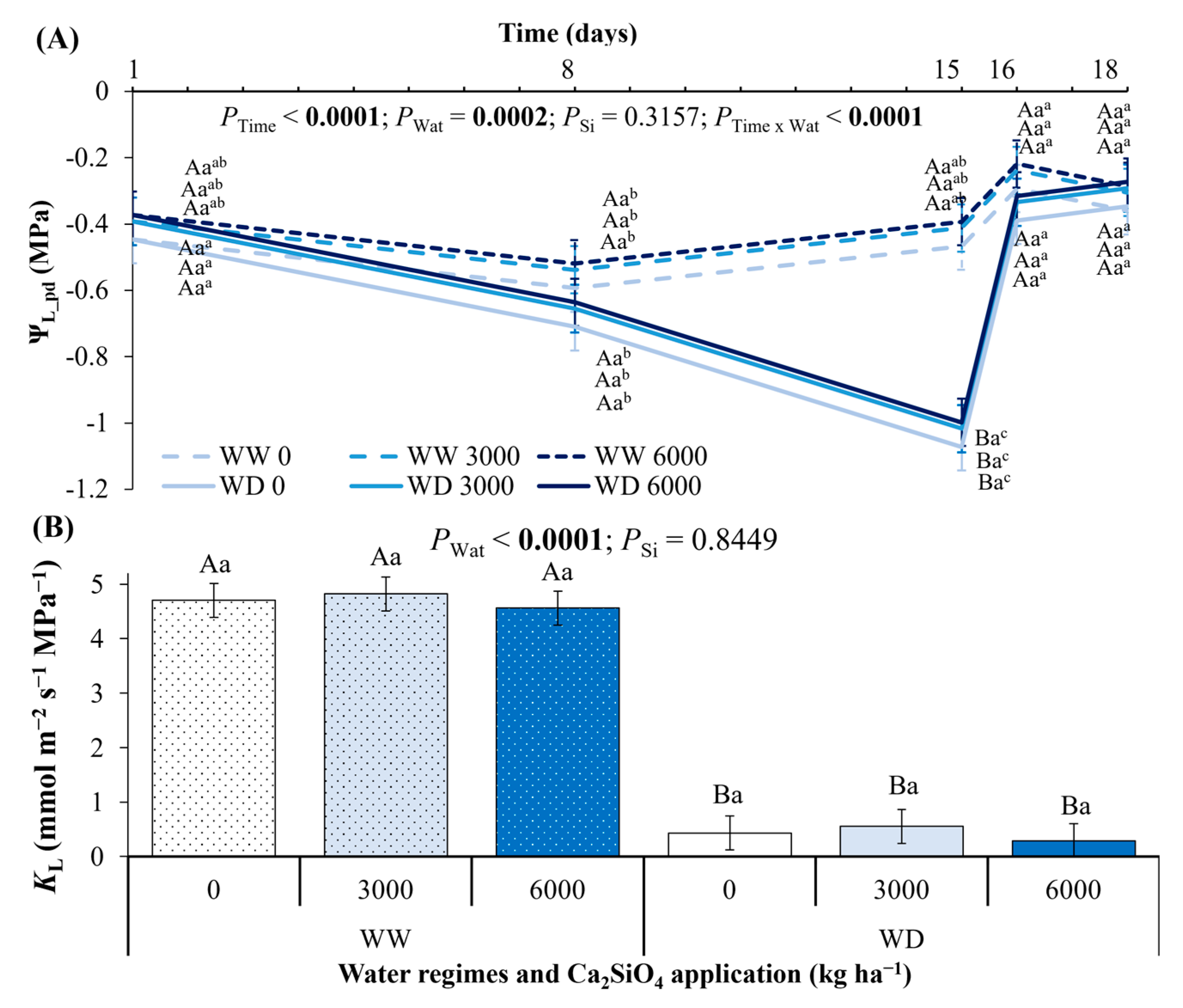

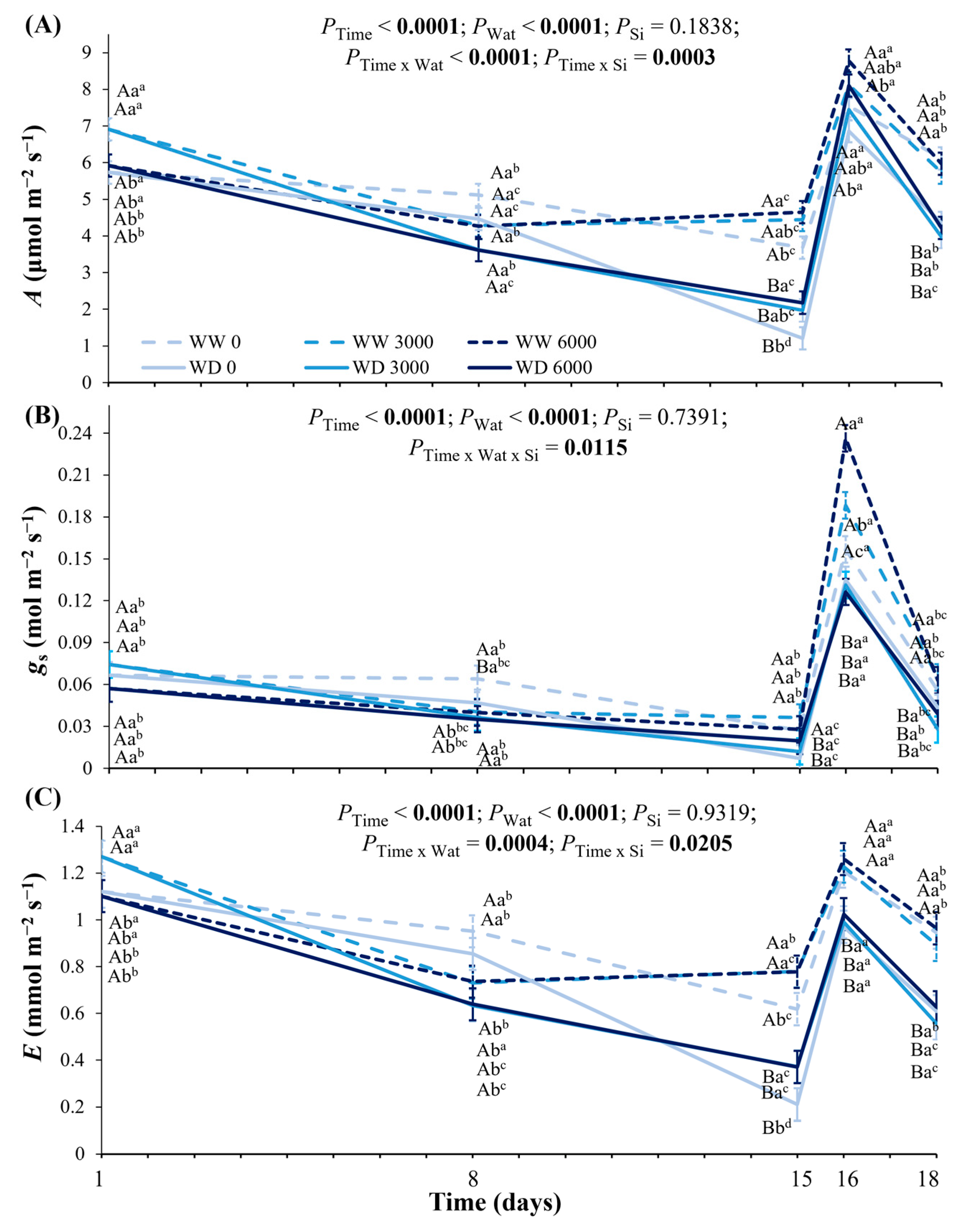

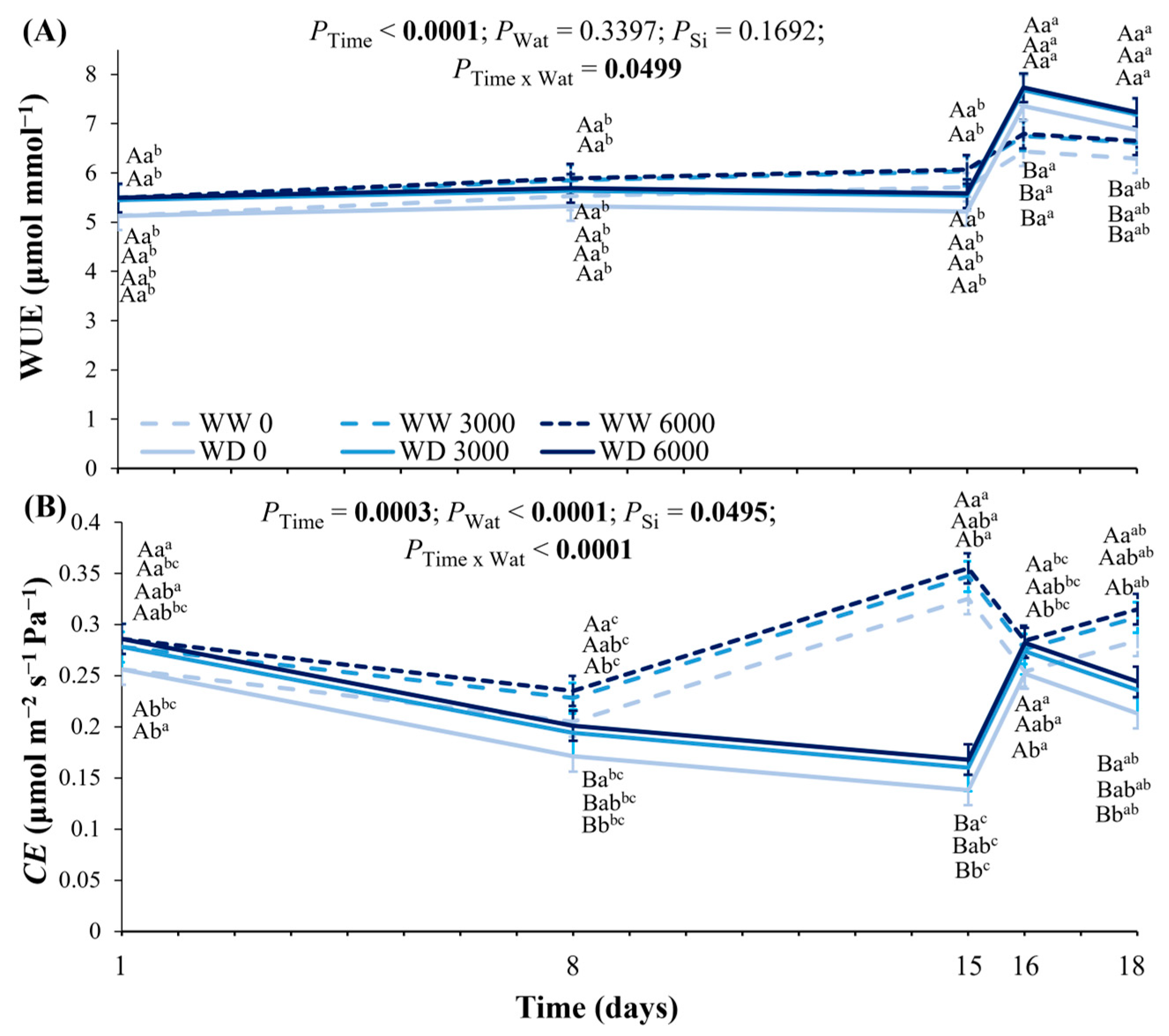

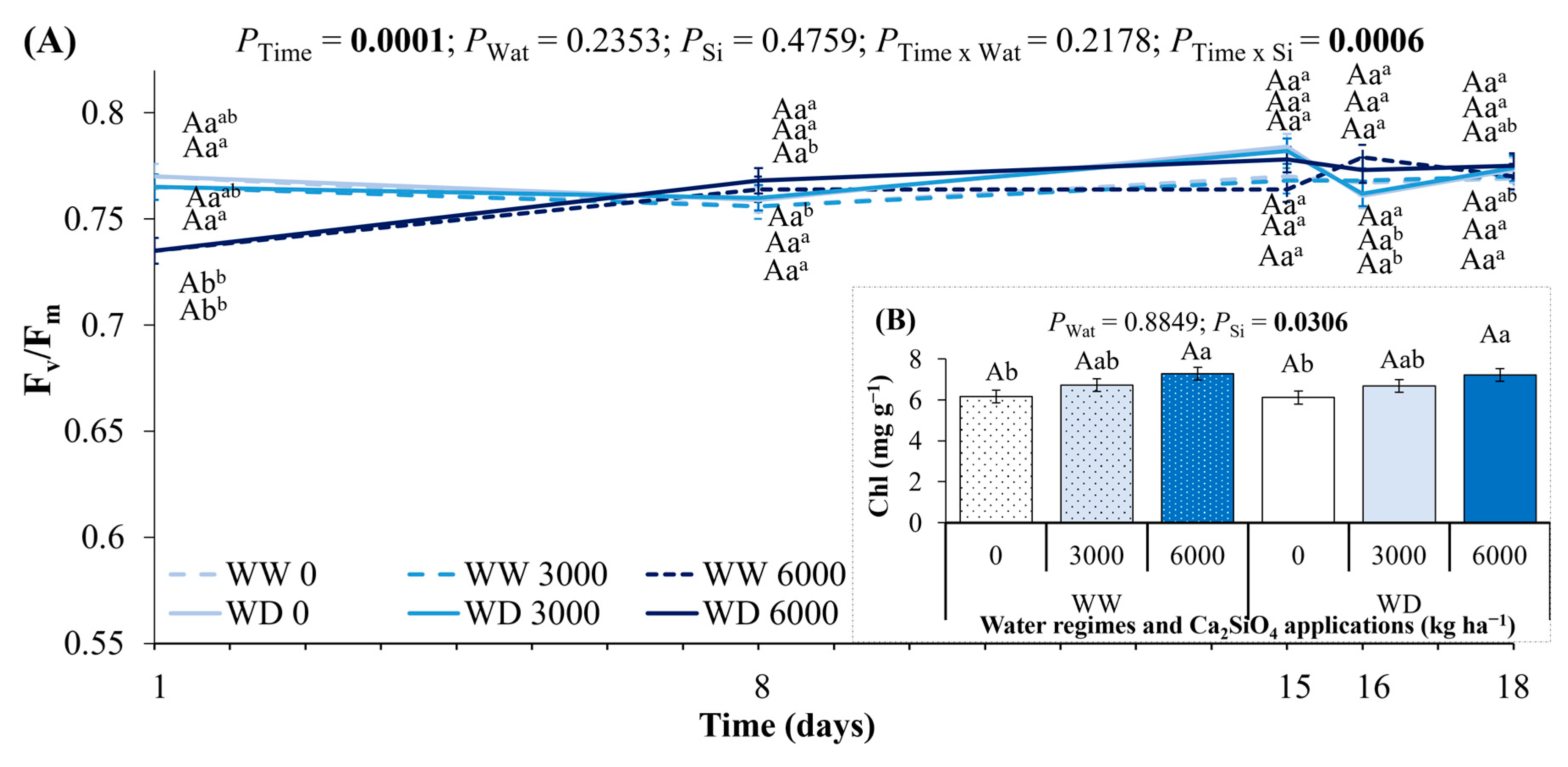

2.3. Leaf Water Potential, Leaf Hydraulic Conductance, Leaf Gas Exchange, and Photochemistry Under Ca2SiO4 Application and Water Deficit

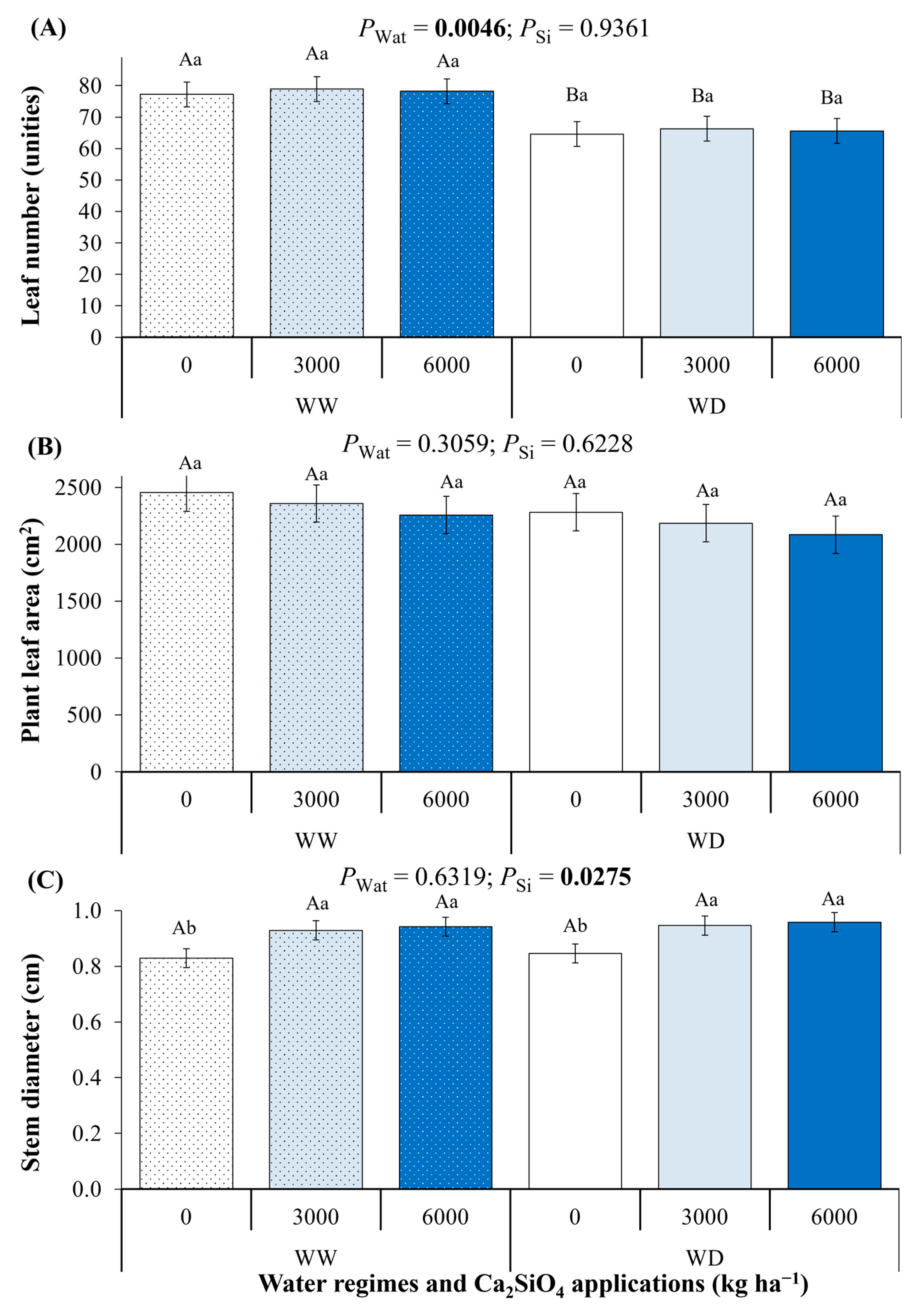

2.4. Plant Morphology Under Ca2SiO4 Application and Water Deficit

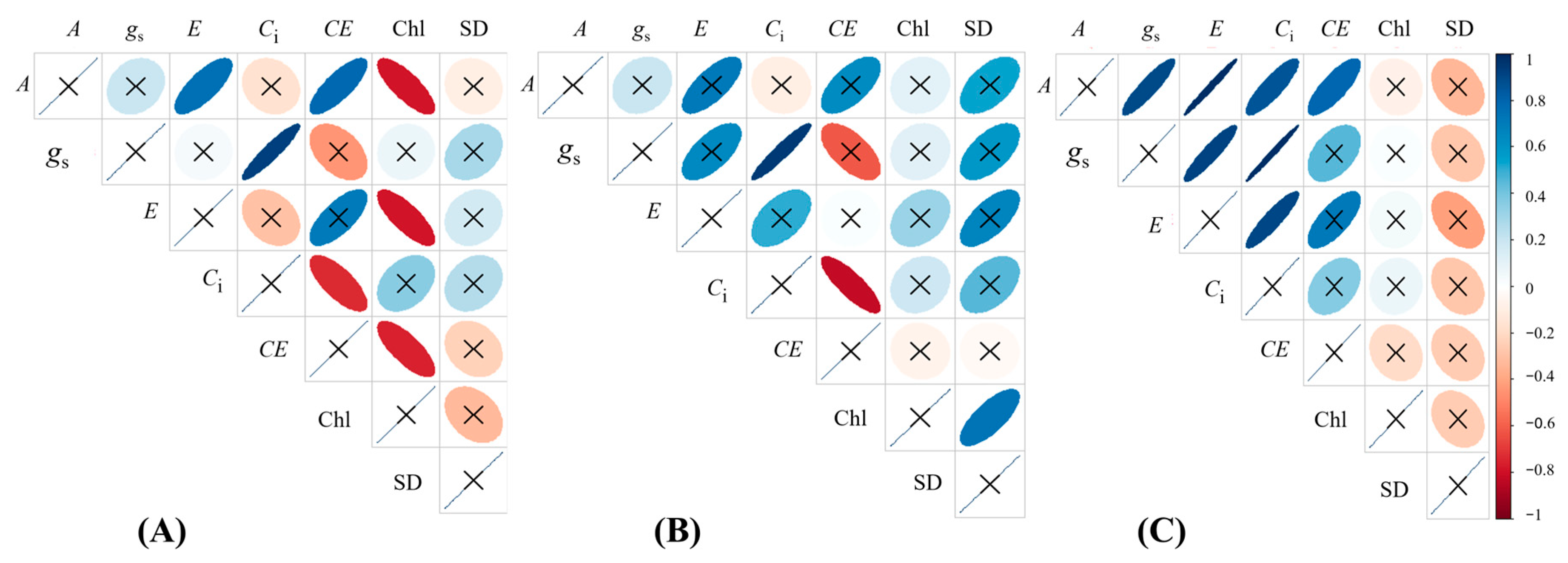

2.5. Correlation Analysis Among Variables Changed by Ca2SiO4 Supplying

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

4.2. Experimental Procedure

4.2.1. Plant Nutritional Analyses

4.2.2. Photosynthetic Responses to Light and Air CO2 Concentration

4.2.3. Leaf Gas Exchange and Photochemistry

4.2.4. Leaf Water Potential and Hydraulic Conductance

4.2.5. Morphological Measurements

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A | Leaf CO2 assimilation |

| A-Ci curves | Curves of leaf CO2 assimilation (A) to increasing intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) |

| Amax | Maximum photosynthesis under natural CO2 and saturating light conditions |

| Amax_gross | Maximum gross photosynthesis under natural CO2 and saturating light conditions |

| A-PPFD curves | Curves of leaf CO2 assimilation (A) to increasing photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) |

| CE | Instantaneous carboxylation efficiency |

| Chl | Chlorophyll |

| Ci | Intercellular CO2 concentration |

| E | Leaf transpiration |

| Fv/Fm | Maximum quantum efficiency of PSII |

| Φ | Apparent quantum yield efficiency |

| gs | Stomatal conductance |

| Jmax | Maximum rate of electron transport-dependent RuBP regeneration |

| KL | Leaf hydraulic conductance |

| LCP | Light compensation point |

| LSP | Light saturation point |

| PPFD | Photosynthetic photon flux density |

| ΨL_pd | Leaf water potential measured at pre-dawn |

| ΨL_14 | Leaf water potential measured at 14h00 |

| Rd | Daily dark respiration |

| SD | Stem diameter |

| Si | Silicon |

| TPU | Maximum rate of triose phosphate use |

| Vcmax | Maximum carboxylation rate of RuBisCO |

| VPDL | Leaf-to-air vapor pressure deficit |

| WD | Water deficit |

| WUE | Instantaneous water use efficiency |

| WW | Well-watered conditions |

References

- Pozza, E.A.; Pozza, A.A.A.; Botelho, D.M.S. Silicon in plant disease control. Rev. Ceres 2015, 62, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, J.; Berni, R.; Hausman, J.F.; Guerriero, G. A review on the beneficial role of silicon against salinity in non-accumulator crops: Tomato as a model. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etesami, H.; Noori, F.; Jeong, B.R. (Eds.) Directions for future research to use silicon and silicon nanoparticles to increase crops tolerance to stresses and improve their quality. In Silicon and Nano-Silicon in Environmental Stress Management and Crop Quality Improvement; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, J.; Samardzic, J.; Maksimović, V.; Timotijevic, G.; Stevic, N.; Laursen, K.H.; Hansen, T.H.; Husted, S.; Schjoerring, J.K.; Liang, Y.; et al. Silicon alleviates iron deficiency in cucumber by promoting mobilization of iron in the root apoplast. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, H.; Greger, M. A review on Si uptake and transport system. Plants 2019, 8, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Yamaji, N. A cooperative system of silicon transport in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2015, 20, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zexer, N.; Kumar, S.; Elbaum, R. Silica deposition in plants: Scaffolding the mineralization. Ann. Bot. 2023, 131, 897–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandlik, R.; Thakral, V.; Raturi, G.; Shinde, S.; Nikolić, M.; Tripathi, D.K.; Sonah, H.; Deshmukh, R. Significance of silicon uptake, transport, and deposition in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 6703–6718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guntzer, F.; Keller, C.; Meunier, J.-D. Benefits of plant silicon for crops: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 32, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, R.J. Significance and role of Si in crop production. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Volume 146, pp. 83–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muneer, S.; Park, Y.G.; Manivannan, A.; Soundararajan, P.; Jeong, B.R. Physiological and proteomic analysis in chloroplasts of Solanum lycopersicum L. under silicon efficiency and salinity stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 21803–21824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.N.; Chen, Z.-H.; Rowe, R.C.; Tissue, D.T. Field application of silicon alleviates drought stress and improves water use efficiency in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1030620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahire, M.L.; Mundada, P.S.; Nikam, T.D.; Bapat, V.A.; Penna, S. Multifaceted roles of silicon in mitigating environmental stresses in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 169, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manivannan, A.; Soundararajan, P.; Jeong, B.R. Silicon: A “quasi-essential” element’s role in plant physiology and development. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1157185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerriero, G.; Hausman, J.-F.; Legay, S. Silicon and the plant extracellular matrix. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Gao, L.; Dong, S.; Sun, Y.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. Role of silicon on plant–pathogen interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhousari, F.; Greger, M. Silicon and mechanisms of plant resistance to insect pests. Plants 2018, 7, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, F.E.; Peiffer, M.; Ray, S.; Tan, C.-W.; Felton, G.W. Silicon-mediated enhancement of herbivore resistance in agricultural crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 631824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, G.J.; Yang, Y. Mechanisms of silicon-induced fungal disease resistance in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 165, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrič Čermelj, A.; Golob, A.; Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Germ, M. Silicon mitigates negative impacts of drought and UV-B radiation in plants. Plants 2022, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emamverdian, A.; Ding, Y.; Xie, Y.; Sangari, S. Silicon mechanisms to ameliorate heavy metal stress in plants. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8492898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, F.; Noreen, S.; Malik, Z.; Kamran, M.; Riaz, M.; Dawood, M.; Parveen, A.; Afzal, S.; Ahmad, I.; Ali, M. Chapter 8—Silicon improves salinity tolerance in crop plants: Insights into photosynthesis, defense system, and production of phytohormones. In Silicon and Nano-Silicon in Environmental Stress Management and Crop Quality Improvement; Etesami, H., Al Saeedi, A.H., El-Ramady, H., Fujita, M., Pessarakli, M., Hossain, M.A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandon, E.; Nualkhao, P.; Vibulkeaw, M.; Tisarum, R.; Samphumphuang, T.; Sun, J.; Chaum, S.; Yooyongwech, S. Mitigating excessive heat in Arabica coffee using nanosilicon and seaweed extract to enhance element homeostasis and photosynthetic recovery. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Latef, A.A.; Tran, L.-S.P. Impacts of priming with silicon on the growth and tolerance of maize plants to alkaline stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfiqar, B.; Raza, M.A.S.; Akhtar, M.; Zhang, N.; Hussain, M.; Ahmad, J.; Abdel-Maksoud, M.A.; Ebaid, H.; Iqbal, R.; Aslam, M.U.; et al. Combined application of biochar and silicon nanoparticles enhance soil and wheat productivity under drought: Insights into physiological and antioxidant defense mechanisms. Curr. Plant Biol. 2024, 40, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osundinakin, M.; Keshinro, O.; Atoloye, E.; Adetunji, O.; Afariogun, T.; Adekoya, I. Enhancing drought resistance in African yam bean (Sphenostylis stenocarpa (Hochst. ex A. Rich.) Harms) through silicon nanoparticle priming: A multi-accession study. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 13, 100166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.A.; Wani, A.H.; Mir, S.H.; Ul Rehman, I.; Tahir, I.; Ahmad, P.; Rashid, I. Elucidating the role of silicon in drought stress tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 165, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Reis, A.R.; Gonzalez-Porras, C.V.; Ferreira, P.M.; da Silva, P.G.; Freire, F.B.S.; Morais, E.G. Unlocking resilience: Physiological roles of benefit elements silicon, selenium and cobalt to enhance tolerance of crop plants against abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229 Pt B, 110515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Lang, D.; Xu, Z.; Ma, X.; Bai, Q.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Q. Bacillus pumilus G5 combined with silicon enhanced flavonoid biosynthesis in drought-stressed Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. by regulating jasmonate, gibberellin and ethylene crosstalk. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 220, 109560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabdallah, N.M.; Saleem, K.; Al-Shammari, A.S.; AlZahrani, S.S.; Raza, A.; Asghar, M.A.; Javed, H.H.; Yong, J.W.H. Unfolding the role of silicon dioxide nanoparticles (SiO2NPs) in inducing drought stress tolerance in Hordeum vulgare through modulation of root metabolic, nutritional, and hormonal profiles. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2025, 177, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, A.; Yadav, S.; Hussain, S.; Kataria, S.; Hajihashemi, S.; Kumari, P.; Yang, X.; Brestic, M. Does silicon really matter for the photosynthetic machinery in plants…? Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 169, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayade, R.; Ghimire, A.; Khan, W.; Lay, L.; Attipoe, J.Q.; Kim, Y. Silicon as a smart fertilizer for sustainability and crop improvement. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GAIN. 2025. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Coffee+Annual_Brasilia_Brazil_BR2025-0013.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Martinati, J.C.; Harakava, R.; Guzzo, S.D.; Tsai, S.M. The potential use of a silicon source as a component of an ecological management of coffee plants. J. Phytopathol. 2008, 156, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carré-Missio, V.; Rodrigues, F.A.; Schurt, D.A.; Resende, R.S.; Souza, N.F.A.; Rezende, D.C.; Moreira, W.R.; Zambolim, L. Effect of foliar applied potassium silicate on coffee leaf infection by Hemileia vastatrix. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2014, 164, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozza, A.A.A.; Alves, E.; Pozza, E.A.; de Carvalho, J.G.; Montanari, M.; Guimarães, P.T.G.; Santos, D.M. Efeito do silício no controle da cercosporiose em três variedades de cafeeiro. Fitopatol. Bras. 2004, 29, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, T.H.P.; Figueiredo, F.C.; Guimarães, P.T.G.; Botrel, P.P.; Rodrigues, C.R. Efeito da associação silício líquido solúvel com fungicida no controle fitossanitário do cafeeiro. Coffee Sci. 2008, 3, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Toledo, M.A.; Reis, P.R. Study of potassium silicate spraying in coffee plants to control Oligonychus ilicis (McGregor) (Acari: Tetranychidae). Adv. Entomol. 2018, 6, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, J.; Jeong, B.R. Drenched silicon suppresses disease and insect pests in coffee plant grown in controlled environment by improving physiology and upregulating defense genes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, A.C.M.C.M.; de Oliveira, M.L.; Caballero, E.C.; Martinez, H.E.P.; Fontes, P.C.R.; Pereira, P.R.G. Growth and nutrient uptake of coffee seedlings cultivated in nutrient solution with and without silicon addition. Rev. Ceres 2012, 59, 392–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, R.V.; da Silva, L.; Ramos, R.A.; de Andrade, C.A.; Zambrosi, F.C.B.; Pereira, S.P. High soil silicon concentrations inhibit coffee root growth without affecting leaf gas exchange. Rev. Bras. Cienc. Solo 2011, 35, 939–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parecido, R.J.; Soratto, R.P.; Guidorizzi, F.V.C.; Perdoná, M.J.; Gitari, H.I. Soil application of silicon enhances initial growth and nitrogen use efficiency of Arabica coffee plants. J. Plant Nutr. 2022, 45, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parecido, R.J.; Soratto, R.P.; Perdoná, M.J.; Gitari, H.I. Foliar-applied silicon may enhance fruit ripening and increase yield and nitrogen use efficiency of Arabica coffee. Eur. J. Agron. 2022, 140, 126602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meddich, A.; Sadouki, A.; Yallouli, N.E.E.; Chagiri, H.; Khalisse, H.; Oudra, B. Performance of slag-based fertilizers in improving durum wheat tolerance to water deficit. Gesunde Pflanz. 2023, 75, 2541–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, D.C.; de Melo, A.S.; de Andrade, W.L.; de Lima, L.M.; Melo, Y.L.; Santos, A.R. Silicon foliar application attenuates the effects of water suppression on cowpea cultivars. Ciênc. Agrotecnologia 2019, 43, e023019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Aguilar, L.A.; Alvarado-Camarillo, D.; Solórzano-Martínez, P.; García-Cerda, L.A.; Vera-Reyes, I. Synergistic effects of zinc and silicon dioxide nanoparticles improve cucumber (Cucumis sativus L) drought tolerance. Plant Nano Biol. 2025, 13, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Abdelghany, A.E.; Zhang, H.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, S.; Zhang, F.; Li, Z.; Fan, J. Exogenous silicon application improves fruit yield and quality of drip-irrigated greenhouse tomato by regulating physiological characteristics and growth under combined drought and salt stress. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 321, 112352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Y.; Cui, G.; Zhang, X. Exogenous silicon improved the cell wall stability by activating non-structural carbohydrates and structural carbohydrates metabolism in salt and drought stressed Glycyrrhiza uralensis stem. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283 Pt 3, 137817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, N.; Altaf, M.A.; Ning, J.; Shu, H.; Fu, H.; Lu, X.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Z. Silicon improves the drought tolerance in pepper plants through the induction of secondary metabolites, GA biosynthesis pathway, and suppression of chlorophyll degradation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 214, 108919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordrostami, M.; Ghasemi-Soloklui, A.A.; Hossain, M.A.; Mostofa, M.G. Breaking barriers: Selenium and silicon-mediated strategies for mitigating abiotic stress in plants. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2023, 92, 2713–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, R.; Mur, L.A.J.; Ruan, J.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. Functions of silicon in plant drought stress responses. Hortic. Res. 2021, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W.; Feng, R.; Hu, Y.; Guo, J.; Gong, H. Silicon enhances water stress tolerance by improving root hydraulic conductance in Solanum lycopersicum L. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, J.; Kostic, L.; Bosnic, P.; Kirkby, E.A.; Nikolic, M. Interactions of silicon with essential and beneficial elements in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 697592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etesami, H.; Jeong, B.R. Silicon (Si): Review and future prospects on the action mechanisms in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses in plants. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 147, 881–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, C.; Arkoun, M.; Jamois, F.; Schwarzenberg, A.; Yvin, J.C.; Etienne, P.; Laîné, P. Silicon promotes growth of Brassica napus L. and delays leaf senescence induced by nitrogen starvation. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gou, T.; Yang, L.; Hu, W.; Chen, X.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, J.; Gong, H. Silicon improves the growth of cucumber under excess nitrate stress by enhancing nitrogen assimilation and chlorophyll synthesis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 152, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Builes, V.H.; Küsters, J.; de Souza, T.R.; Simmes, C. Calcium nutrition in coffee and its influence on growth, stress tolerance, cations uptake, and productivity. Front. Agron. 2020, 2, 590892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Tuna, L.; Higgs, D. Effect of silicon on plant growth and mineral nutrition of maize grown under water-stress conditions. J. Plant Nutr. 2007, 29, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Chen, K. The regulatory role of silicon on water relations, photosynthetic gas exchange and carboxylation activities of wheat leaves in field drought conditions. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2012, 34, 1589–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emam, M.M.; Khattab, H.E.; Helal, N.M.; Deraz, A.E. Effect of selenium and silicon on yield quality of rice plant grown under drought stress. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2014, 8, 596–605. [Google Scholar]

- Kutasy, E.; Diósi, G.; Buday-Bódi, E.; Nagy, P.T.; Melash, A.A.; Forgács, F.Z.; Virág, I.C.; Vad, A.M.; Bytyqi, B.; Buday, T.; et al. Changes in plant and grain quality of winter oat (Avena sativa L.) varieties in response to silicon and sulphur foliar fertilization under abiotic stress conditions. Plants 2023, 12, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, C.W.A.; de Souza Nunes, G.H.; Preston, H.A.F.; da Silva, F.B.V.; Preston, W.; Loureiro, F.L.C. Influence of silicon fertilization on nutrient accumulation, yield and fruit quality of melon growth in Northeastern Brazil. Silicon 2020, 12, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ługowska, M. Effect of bio-stimulants on the yield of cucumber fruits and on nutrient content. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 14, 2112–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadas, W.; Kondraciuk, T. Effect of silicon on micronutrient content in new potato tubers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shireen, F.; Nawaz, M.A.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Sohail, H.; Sun, J.; Cao, H.; Huang, Y.; Bie, Z. Boron: Functions and approaches to enhance its availability in plants for sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, S.; Kapoor, D. Fascinating regulatory mechanism of silicon for alleviating drought stress in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 1044–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koentjoro, Y.; Purwanto, E.; Purnomo, D. The role of silicon on content of proline, protein and abscisic acid on soybean under drought stress. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Sustainable Agriculture and Environment, Surakarta, Indonesia, 25–27 August 2020; IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Volume 637, p. 012086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazim, M.; Li, X.; Anjum, S.; Ahmad, F.; Ali, M.; Muhammad, M.; Shahzad, K.; Lin, L.; Zulfiqar, U. Silicon nanoparticles: A novel approach in plant physiology to combat drought stress in arid environment. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2024, 58, 103190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yang, Z.; Song, Z.; Wang, N.; Guo, N.; Niu, J.; Liu, A.; Bai, B.; Ahammed, G.J.; Chen, S. Silicon enhances plant resistance to Fusarium wilt by promoting antioxidant potential and photosynthetic capacity in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1011859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, V.M.d.A.; Scalon, S.d.P.Q.; Santos, C.C.; Linné, J.A.; Silverio, J.M.; Cerqueira, W.M.; de Almeida, J.L.d.C.S. Do silicon and salicylic acid attenuate water deficit damage in Talisia esculenta Radlk seedlings? Plants 2023, 12, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detmann, K.C.; Araújo, W.L.; Martins, S.C.V.; Sanglard, L.M.V.P.; Reis, J.V.; Detmann, E.; Rodrigues, F.Á.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Fernie, A.R.; DaMatta, F.M. Silicon nutrition increases grain yield, which, in turn, exerts a feed-forward stimulation of photosynthetic rates via enhanced mesophyll conductance and alters primary metabolism in rice. New Phytol. 2012, 196, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovis, V.L.; Machado, E.C.; Ribeiro, R.V.; Magalhães Filho, J.R.; Marchiori, P.E.R.; Sales, C.R.G. Roots are important sources of carbohydrates during flowering and fruiting in ‘Valencia’ sweet orange trees with varying fruit load. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 174, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, A.R.M.; Martins, S.C.V.; Batista, K.D.; Celin, E.F.; DaMatta, F.M. Varying leaf-to-fruit ratios affect branch growth and dieback, with little to no effect on photosynthesis, carbohydrate or mineral pools, in different canopy positions of field-grown coffee trees. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2012, 77, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Cao, B.; Xu, K. Uncovering the dominant role of root lignin accumulation in silicon-induced resistance to drought in tomato. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259 Pt 1, 129075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, W.B.S.; Teixeira, G.C.M.; de Mello Prado, R.; Rocha, A.M.S. Silicon mitigates nutritional stress of nitrogen, phosphorus, and calcium deficiency in two forages plants. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, G.C.M.; de Mello Prado, R.; Oliveira, K.S.; D’Amico-Damião, V.; Sousa Junior, G.S. Silicon increases leaf chlorophyll content and iron nutritional efficiency and reduces iron deficiency in sorghum plants. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Choudhary, A.; Kaur, H.; Singh, K.; Guha, S.; Choudhary, D.R.; Sonkar, A.; Mehta, S.; Husen, A. Exploring the role of silicon in enhancing sustainable plant growth, defense system, environmental stress mitigation and management. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Raij, B.; Andrade, J.C.; Cantarella, H.; Quaggio, J.A. Análise Química Para Avaliação da Fertilidade de Solos Tropicais; IAC: Campinas, Brazil, 2001; 284p. [Google Scholar]

- van Raij, B.; Cantarella, H.; Quaggio, J.A.; Furlani, A.M.C. Recomendação de Adubação e Calagem Para o Estado de São Paulo; Fundação IAC: Campinas, Brazil, 1997; 285p. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, R.A. Regime Térmico e Relação Fonte-Dreno em Laranjeiras: Dinâmica de Carboidratos, Fotossíntese e Crescimento. Master’s Thesis, Instituto Agronômico, Campinas, Brazil, 2009; 52p. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, D.L.; Snyder, G.H.; Martin, F.G. Multi-year response of sugarcane to calcium silicate slag on everglades histosols. Agron. J. 1991, 83, 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, O.A.; Moniz, A.C.; Jorge, J.A.; Valadares, J.M.A.S. Métodos de Análise Química e Física de Solos do IAC; Boletim técnico; Fundação IAC: Campinas, Brazil, 1986; Volume 106, 94p. [Google Scholar]

- Colman, E.A. A laboratory procedure for determining the field capacity of soils. Soil Sci. 1947, 67, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataglia, O.C.; Furlani, A.M.C.; Teixeira, J.P.F.; Furlani, P.R.; Gallo, J.R. Métodos de Análise Química de Plantas; Boletim Técnico; IAC: Campinas, Brazil, 1983; Volume 78, 48p. [Google Scholar]

- Korndörfer, G.H.; Pereira, H.S.; Nolla, A. Análise de Silício: Solo, Planta e Fertilizante; Boletim Técnico; GPSi/ICIAG/UFU: Uberlândia, Brazil, 2004; Volume 2, 50p. [Google Scholar]

- Long, S.P.; Hallgren, J.E. Measurement of CO2 assimilation by plants in the field and the laboratory. In Photosynthesis and Production in a Changing Environment; Hall, D.O., Scurlock, J.M.O., Bolhàr-Nordenkampf, H.R., Leegood, R.C., Long, S.P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrech, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 129–167. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, G.D.; von Caemmerer, S.; Berry, J.A. A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 1980, 149, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, T.D. What gas exchange data can tell us about photosynthesis? Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1161–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, H.K.; Wellburn, A.R. Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 1983, 11, 591–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.; Marchiori, P.E.R.; Maciel, C.P.; Machado, E.C.; Ribeiro, R.V. Fotossíntese, relações hídricas e crescimento de cafeeiros jovens em relação à disponibilidade de fósforo. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2010, 45, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rakocevic, M.; Ribeiro, R.V. Soil Ca2SiO4 Supplying Increases Drought Tolerance of Young Arabica Coffee Plants. Plants 2025, 14, 3666. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233666

Rakocevic M, Ribeiro RV. Soil Ca2SiO4 Supplying Increases Drought Tolerance of Young Arabica Coffee Plants. Plants. 2025; 14(23):3666. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233666

Chicago/Turabian StyleRakocevic, Miroslava, and Rafael Vasconcelos Ribeiro. 2025. "Soil Ca2SiO4 Supplying Increases Drought Tolerance of Young Arabica Coffee Plants" Plants 14, no. 23: 3666. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233666

APA StyleRakocevic, M., & Ribeiro, R. V. (2025). Soil Ca2SiO4 Supplying Increases Drought Tolerance of Young Arabica Coffee Plants. Plants, 14(23), 3666. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants14233666