Beyond Bulk Metabolomics: Emerging Technologies for Defining Cell-Type Specific Metabolic Pathways in Health and Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

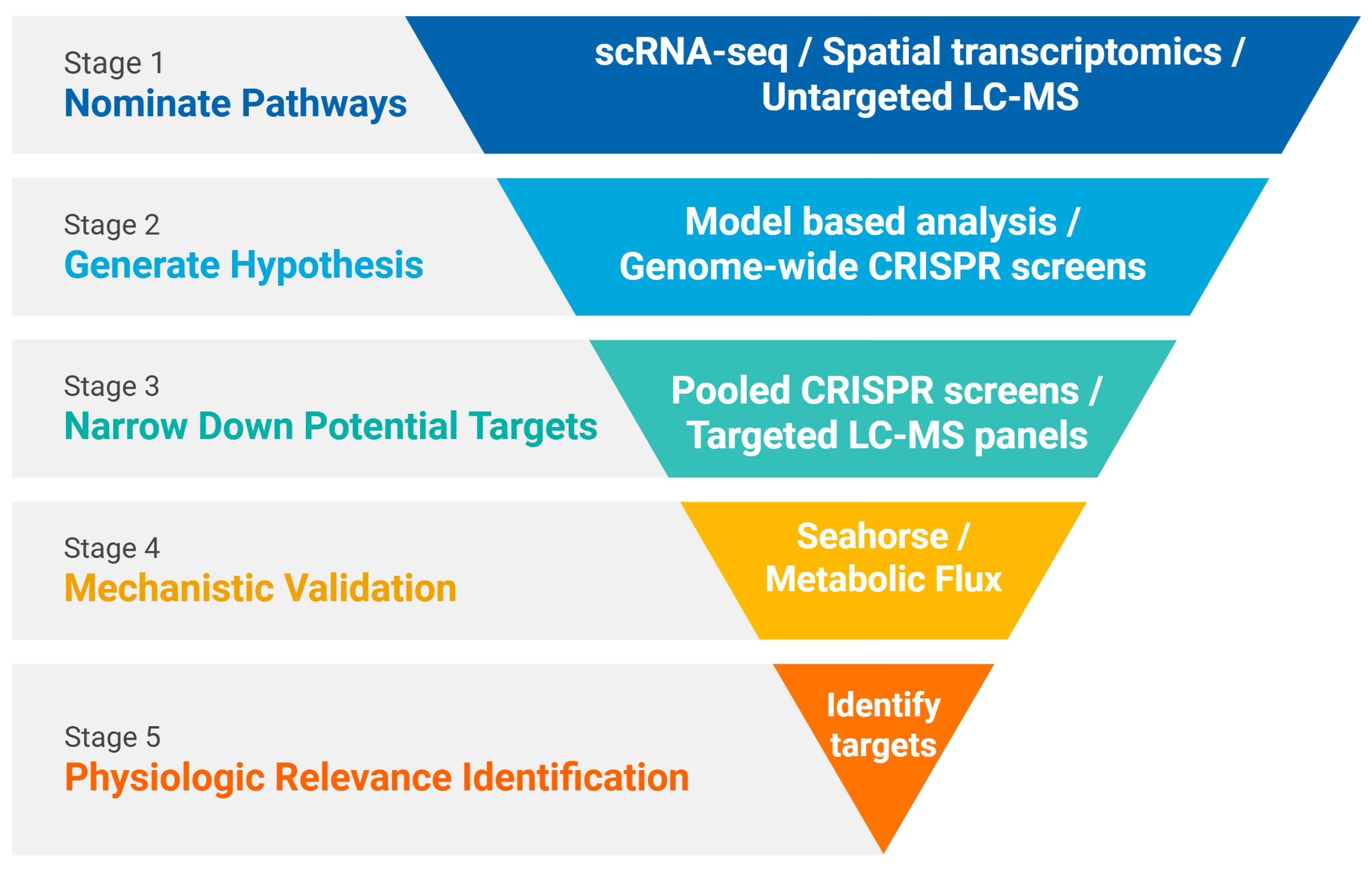

2. Transcriptomic-Based Approaches to Investigating Metabolism in Rare Immune Cells

3. Approaches to Assaying Real-Time Metabolic Flux in Rare Cell Populations

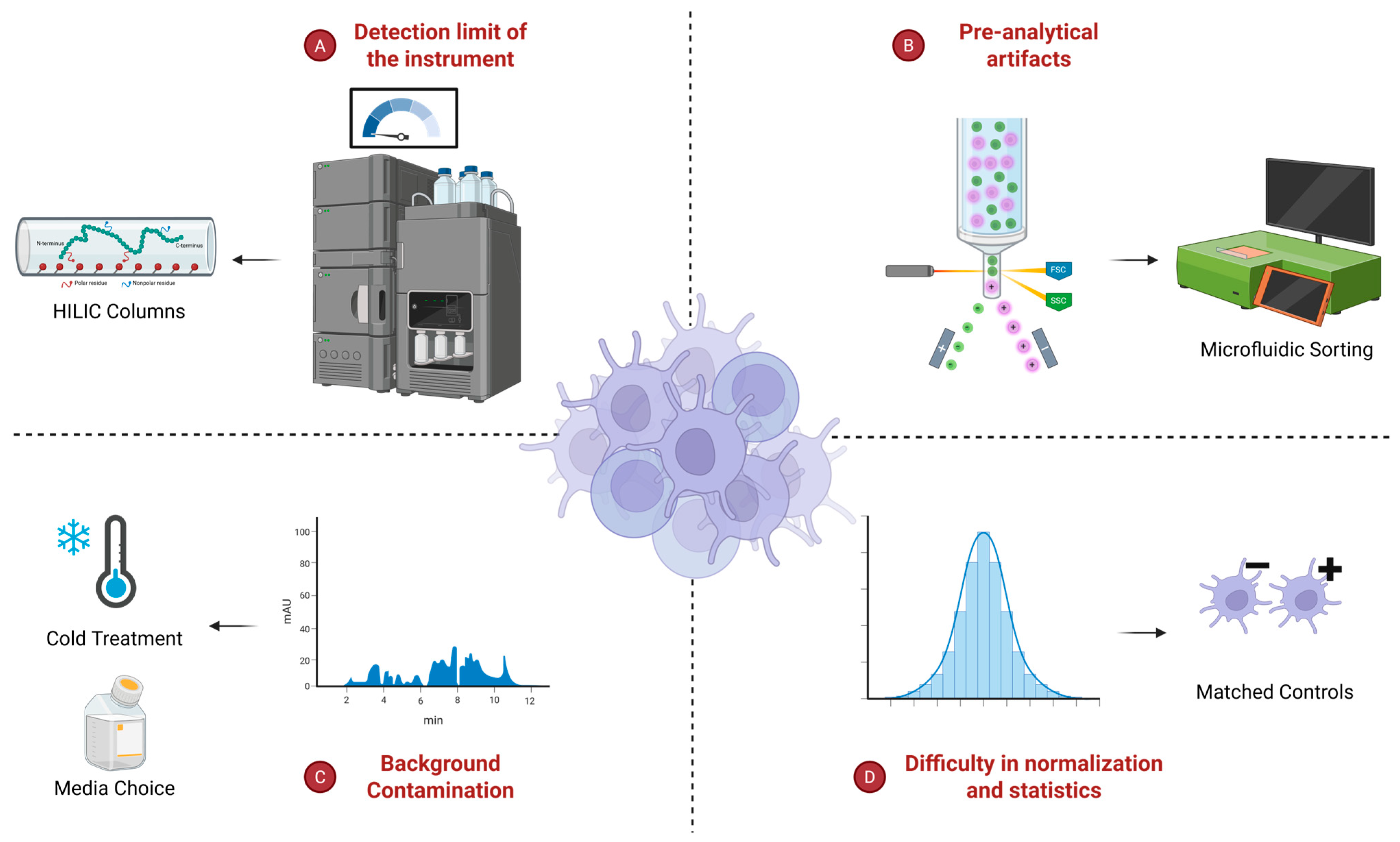

4. Emerging Metabolomic Approaches to Rare Cell Populations

5. Gaps Between Technical Limitations and Physiological Relevance

6. Unveiling the Spatial Landscape of Cellular Metabolism

7. From Correlation to Causation: CRISPR Screening Closes the Loop

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATP | Adenosine triphosphate |

| BiGG | Biochemically, Genetically and Genomically structured models database |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CCC | Cell–cell communication |

| CENCAT | Cellular energetics through noncanonical amino acid tagging |

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| CRISPRa | CRISPR activation |

| CRISPRi | CRISPR interference |

| CyESI-MS | Cytoplasmic electrospray ionization mass spectrometry |

| ECAR | Extracellular acidification rate |

| FACS | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting |

| FBA | Flux Balance Analysis |

| GEMs | Genome-scale metabolic models |

| GSH | Reduced glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized glutathione |

| HCA | Human Cell Atlas |

| hi-scMet | High-throughput single-cell metabolomics |

| HILIC | Hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography |

| HSCs | Hematopoietic stem cells |

| KO | Knockout |

| LC-MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| MEMs | Model Extraction Methods |

| mCCC | Metabolite-mediated cell–cell communication |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

| MS | Mass spectrometry |

| MSI | Mass spectrometry imaging |

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (oxidized) |

| NADH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (reduced) |

| NADP+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (oxidized) |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced) |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OCR | Oxygen consumption rate |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCLIMS | Single-cell live-cell imaging–mass spectrometry |

| SCENITH | Single-cell energetic metabolism by profiling translation inhibition |

| scFBA | Single-cell Flux Balance Analysis |

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell RNA sequencing |

| sgRNA | Single-guide RNA |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid cycle |

| TCR | T cell receptor |

| Th17 | T helper 17 cell |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TNF | Tumor necrosis factor |

| Treg | Regulatory T cell |

| UHPLC | Ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography |

| XF | Extracellular flux |

References

- Chandel, N.S. Evolution of Mitochondria as Signaling Organelles. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 204–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarty, R.P.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondria as Signaling Organelles Control Mammalian Stem Cell Fate. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S.E.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondria Reactive Oxygen Species Signaling in Immune Responses. Immunity 2025, 58, 1904–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H. Immunometabolism at the Intersection of Metabolic Signaling, Cell Fate, and Systems Immunology. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2022, 19, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.M.; Weinberg, S.E.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial Control of Immunity: Beyond ATP. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 608–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, H.; Sun, H.; Liao, H.; Li, Q.; Ma, X. Metabolic Regulation of Immunity in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 116463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llibre, A.; Kucuk, S.; Gope, A.; Certo, M.; Mauro, C. Lactate: A Key Regulator of the Immune Response. Immunity 2025, 58, 535–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, S.; Rosenthal, S.B.; Ishizuka, K.; Troutman, T.D.; Rohm, T.V.; Khader, N.; Aleman-Muench, G.; Sano, Y.; Archilei, S.; Soroosh, P.; et al. Lipid-Associated Macrophages’ Promotion of Fibrosis Resolution during MASH Regression Requires TREM2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2405746121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Rosenthal, S.B.; Liu, X.; Miciano, C.; Hou, X.; Miller, M.; Buchanan, J.; Poirion, O.B.; Chilin-Fuentes, D.; Han, C.; et al. Multi-Modal Analysis of Human Hepatic Stellate Cells Identifies Novel Therapeutic Targets for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. J. Hepatol. 2025, 82, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardam-Kaur, T.; Sun, J.; Borges da Silva, H. Metabolic Regulation of Tissue-Resident Memory CD8+ T Cells. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2021, 57, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanelli, P.; Sandoval, T.A.; Cubillos-Ruiz, J.R. Dendritic Cell Metabolism and Function in Tumors. Trends Immunol. 2019, 40, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M.; Dirschl, S.M.; Scherm, M.G.; Serr, I.; Daniel, C. Niche-Specific Control of Tissue Function by Regulatory T Cells—Current Challenges and Perspectives for Targeting Metabolic Disease. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Ye, F.; Guo, G. Revolutionizing Immunology with Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 16, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, A.; Wang, C.; Fessler, J.; DeTomaso, D.; Avila-Pacheco, J.; Kaminski, J.; Zaghouani, S.; Christian, E.; Thakore, P.; Schellhaass, B.; et al. Metabolic Modeling of Single Th17 Cells Reveals Regulators of Autoimmunity. Cell 2021, 184, 4168–4185.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Zhang, Y.; Tsuji, T.; Gao, X.; Shamsi, F.; Wagner, A.; Yosef, N.; Cui, K.; Chen, H.; Kiebish, M.A.; et al. MEBOCOST Maps Metabolite-Mediated Intercellular Communications Using Single-Cell RNA-Seq. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, gkaf569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickovic, S.; Eraslan, G.; Salmén, F.; Klughammer, J.; Stenbeck, L.; Schapiro, D.; Äijö, T.; Bonneau, R.; Bergenstråhle, L.; Navarro, J.F.; et al. High-Definition Spatial Transcriptomics for in Situ Tissue Profiling. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 987–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriques, S.G.; Stickels, R.R.; Goeva, A.; Martin, C.A.; Murray, E.; Vanderburg, C.R.; Welch, J.; Chen, L.M.; Chen, F.; Macosko, E.Z. Slide-Seq: A Scalable Technology for Measuring Genome-Wide Expression at High Spatial Resolution. Science 2019, 363, 1463–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Waingankar, T.P.; D’Silva, P. Seahorse Assay for the Analysis of Mitochondrial Respiration Using Saccharomyces Cerevisiae as a Model System. In Methods in Enzymology; Wiedemann, N., Ed.; Mitochondrial Translocases Part B; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2024; Volume 707, pp. 673–683. [Google Scholar]

- Damiani, C.; Maspero, D.; Filippo, M.D.; Colombo, R.; Pescini, D.; Graudenzi, A.; Westerhoff, H.V.; Alberghina, L.; Vanoni, M.; Mauri, G. Integration of Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data into Population Models to Characterize Cancer Metabolism. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1006733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Xiao, J.F.; Tuli, L.; Ressom, H.W. LC-MS-Based Metabolomics. Mol. Biosyst. 2012, 8, 470–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, A.C.A.; Vuckovic, D. Current Status and Advances in Untargeted LC-MS Tissue Lipidomics Studies in Cardiovascular Health. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vilbiss, A.W.; Zhao, Z.; Martin-Sandoval, M.S.; Ubellacker, J.M.; Tasdogan, A.; Agathocleous, M.; Mathews, T.P.; Morrison, S.J. Metabolomic Profiling of Rare Cell Populations Isolated by Flow Cytometry from Tissues. eLife 2021, 10, e61980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Ge, S.; Liao, T.; Yuan, M.; Qian, W.; Chen, Q.; Liang, W.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ju, Z.; et al. Integrative Single-Cell Metabolomics and Phenotypic Profiling Reveals Metabolic Heterogeneity of Cellular Oxidation and Senescence. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Leng, Y.; Li, X.; Meng, Y.; Yin, Z.; Hang, W. High Spatial Resolution Mass Spectrometry Imaging for Spatial Metabolomics: Advances, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 159, 116902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneemann, J.; Schäfer, K.-C.; Spengler, B.; Heiles, S. IR-MALDI Mass Spectrometry Imaging with Plasma Post-Ionization of Nonpolar Metabolites. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 16086–16094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niehaus, M.; Soltwisch, J.; Belov, M.E.; Dreisewerd, K. Transmission-Mode MALDI-2 Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Cells and Tissues at Subcellular Resolution. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 925–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argüello, R.J.; Combes, A.J.; Char, R.; Gigan, J.-P.; Baaziz, A.I.; Bousiquot, E.; Camosseto, V.; Samad, B.; Tsui, J.; Yan, P.; et al. SCENITH: A Flow Cytometry-Based Method to Functionally Profile Energy Metabolism with Single-Cell Resolution. Cell Metab. 2020, 32, 1063–1075.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrieling, F.; van der Zande, H.J.P.; Naus, B.; Smeehuijzen, L.; van Heck, J.I.P.; Ignacio, B.J.; Bonger, K.M.; Van den Bossche, J.; Kersten, S.; Stienstra, R. CENCAT Enables Immunometabolic Profiling by Measuring Protein Synthesis via Bioorthogonal Noncanonical Amino Acid Tagging. Cell Rep. Methods 2024, 4, 100883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, P.J.; Hopkins, R.A.; Xiang, W.W.; Au, B.; Kaliaperumal, N.; Fairhurst, A.-M.; Connolly, J.E. Met-Flow, a Strategy for Single-Cell Metabolic Analysis Highlights Dynamic Changes in Immune Subpopulations. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yao, Q.J.; Wu, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, L.; Liu, W.; Qian, K.; Wan, J.-J.; Zhou, B.O. Deciphering the Metabolic Heterogeneity of Hematopoietic Stem Cells with Single-Cell Resolution. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 209–221.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.G.; Chudnovskiy, A.; Baudrier, L.; Prizer, B.; Liu, Y.; Ostendorf, B.N.; Yamaguchi, N.; Arab, A.; Tavora, B.; Timson, R.; et al. Functional Genomics In Vivo Reveal Metabolic Dependencies of Pancreatic Cancer Cells. Cell Metab. 2021, 33, 211–221.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manguso, R.T.; Pope, H.W.; Zimmer, M.D.; Brown, F.D.; Yates, K.B.; Miller, B.C.; Collins, N.B.; Bi, K.; LaFleur, M.W.; Juneja, V.R.; et al. In Vivo CRISPR Screening Identifies Ptpn2 as a Cancer Immunotherapy Target. Nature 2017, 547, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shifrut, E.; Carnevale, J.; Tobin, V.; Roth, T.L.; Woo, J.M.; Bui, C.T.; Li, P.J.; Diolaiti, M.E.; Ashworth, A.; Marson, A. Genome-Wide CRISPR Screens in Primary Human T Cells Reveal Key Regulators of Immune Function. Cell 2018, 175, 1958–1971.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnas, O.; Jovanovic, M.; Eisenhaure, T.M.; Herbst, R.H.; Dixit, A.; Ye, C.J.; Przybylski, D.; Platt, R.J.; Tirosh, I.; Sanjana, N.E.; et al. A Genome-Wide CRISPR Screen in Primary Immune Cells to Dissect Regulatory Networks. Cell 2015, 162, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A.; Parnas, O.; Li, B.; Chen, J.; Fulco, C.P.; Jerby-Arnon, L.; Marjanovic, N.D.; Dionne, D.; Burks, T.; Raychowdhury, R.; et al. Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens. Cell 2016, 167, 1853–1866.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doench, J.G. Am I Ready for CRISPR? A User’s Guide to Genetic Screens. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, C.; Kim, G.B.; Kim, W.J.; Kim, H.U.; Lee, S.Y. Current Status and Applications of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norsigian, C.J.; Pusarla, N.; McConn, J.L.; Yurkovich, J.T.; Dräger, A.; Palsson, B.O.; King, Z. BiGG Models 2020: Multi-Strain Genome-Scale Models and Expansion across the Phylogenetic Tree. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D402–D406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Novère, N.; Bornstein, B.; Broicher, A.; Courtot, M.; Donizelli, M.; Dharuri, H.; Li, L.; Sauro, H.; Schilstra, M.; Shapiro, B.; et al. BioModels Database: A Free, Centralized Database of Curated, Published, Quantitative Kinetic Models of Biochemical and Cellular Systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D689–D691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, N.C.; Becker, S.A.; Jamshidi, N.; Thiele, I.; Mo, M.L.; Vo, T.D.; Srivas, R.; Palsson, B.Ø. Global Reconstruction of the Human Metabolic Network Based on Genomic and Bibliomic Data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 1777–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, I.; Swainston, N.; Fleming, R.M.T.; Hoppe, A.; Sahoo, S.; Aurich, M.K.; Haraldsdottir, H.; Mo, M.L.; Rolfsson, O.; Stobbe, M.D.; et al. A Community-Driven Global Reconstruction of Human Metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 419–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunk, E.; Sahoo, S.; Zielinski, D.C.; Altunkaya, A.; Dräger, A.; Mih, N.; Gatto, F.; Nilsson, A.; Preciat Gonzalez, G.A.; Aurich, M.K.; et al. Recon3D Enables a Three-Dimensional View of Gene Variation in Human Metabolism. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lötscher, J.; Balmer, M.L. Sensing between Reactions—How the Metabolic Microenvironment Shapes Immunity. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2019, 197, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-P.; Lei, Q.-Y. Metabolite Sensing and Signaling in Cell Metabolism. Sig Transduct. Target. Ther. 2018, 3, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H.J.; Angiari, S. Metabolite Transporters as Regulators of Immunity. Metabolites 2020, 10, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, G.A.; Fayard, E.; Picard, F.; Auwerx, J. Nuclear Receptors and the Control of Metabolism. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2003, 65, 261–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opdam, S.; Richelle, A.; Kellman, B.; Li, S.; Zielinski, D.C.; Lewis, N.E. A Systematic Evaluation of Methods for Tailoring Genome-Scale Metabolic Models. Cell Syst. 2017, 4, 318–329.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.A.; Palsson, B.O. Context-Specific Metabolic Networks Are Consistent with Experiments. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2008, 4, e1000082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zur, H.; Ruppin, E.; Shlomi, T. iMAT: An Integrative Metabolic Analysis Tool. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 3140–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Eddy, J.A.; Price, N.D. Reconstruction of Genome-Scale Metabolic Models for 126 Human Tissues Using mCADRE. BMC Syst. Biol. 2012, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabula Sapiens. Available online: https://tabula-sapiens.sf.czbiohub.org/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Pan, L.; Parini, P.; Tremmel, R.; Loscalzo, J.; Lauschke, V.M.; Maron, B.A.; Paci, P.; Ernberg, I.; Tan, N.S.; Liao, Z.; et al. Single Cell Atlas: A Single-Cell Multi-Omics Human Cell Encyclopedia. Genome Biol. 2024, 25, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-H.; Wen, R.; Yang, N.; Zhang, T.-N.; Liu, C.-F. Roles of Protein Post-Translational Modifications in Glucose and Lipid Metabolism: Mechanisms and Perspectives. Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M.; Hammarén, H.M.; Savitski, M.M.; Baek, S.H. Control of Protein Stability by Post-Translational Modifications. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, E.; Flamholz, A.; Bar-Even, A.; Davidi, D.; Milo, R.; Liebermeister, W. The Protein Cost of Metabolic Fluxes: Prediction from Enzymatic Rate Laws and Cost Minimization. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1005167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, H.; Shaytan, A.; Panchenko, A.R. Physicochemical Mechanisms of Protein Regulation by Phosphorylation. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, I.; Ahn, I.; Lee, J.; Lee, N. Extracellular Flux Assay (Seahorse Assay): Diverse Applications in Metabolic Research across Biological Disciplines. Mol. Cells 2024, 47, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Neilson, A.; Swift, A.L.; Moran, R.; Tamagnine, J.; Parslow, D.; Armistead, S.; Lemire, K.; Orrell, J.; Teich, J.; et al. Multiparameter Metabolic Analysis Reveals a Close Link between Attenuated Mitochondrial Bioenergetic Function and Enhanced Glycolysis Dependency in Human Tumor Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2007, 292, C125–C136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrick, D.A.; Neilson, A.; Beeson, C. Advances in Measuring Cellular Bioenergetics Using Extracellular Flux. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayberry, C.L.; Wilson, J.J.; Sison, B.; Chang, C.-H. Protocol to Assess Bioenergetics and Mitochondrial Fuel Usage in Murine Autoreactive Immunocytes Using the Seahorse Extracellular Flux Analyzer. STAR Protoc. 2024, 5, 102971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desousa, B.R.; Kim, K.K.; Jones, A.E.; Ball, A.B.; Hsieh, W.Y.; Swain, P.; Morrow, D.H.; Brownstein, A.J.; Ferrick, D.A.; Shirihai, O.S.; et al. Calculation of ATP Production Rates Using the Seahorse XF Analyzer. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e56380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher Scientific. Agilent Technologies XFp Real-Time ATP Rate Assay Kit, Catalog No. 103591-100. Available online: https://www.fishersci.ca/shop/products/xfp-real-time-atp-rate-assay-kit/103591100 (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Gu, X.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wan, Q. Measurement of Mitochondrial Respiration in Adherent Cells by Seahorse XF96 Cell Mito Stress Test. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, E.M.; Furtado Bruza, B.; Danchine, V.D.; Grant, R.A.; Vasan, K.; Kharel, A.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, W.; Szibor, M.; Weinberg, S.E.; et al. Mitochondrial Respiration Is Necessary for CD8+ T Cell Proliferation and Cell Fate. Nat. Immunol. 2025, 26, 1267–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.; Leblanc, P.; Hong, Y.J.; Kim, K.-S. Integrative Analysis of Mitochondrial Metabolic Dynamics in Reprogramming Human Fibroblast Cells. STAR Protoc. 2022, 3, 101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedhart, N.B.; Simon-Molas, H. Metabolic Profiling of Tumor and Immune Cells Integrating Seahorse and Flow Cytometry. In Cancer Immunosurveillance: Methods and Protocols; López-Soto, A., Folgueras, A.R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 103–126. ISBN 978-1-0716-4558-1. [Google Scholar]

- Wishart, C.L.; Spiteri, A.G.; Tan, J.; Counoupas, C.; Triccas, J.A.; Macia, L.; King, N.J.C. Deep Metabolic Profiling of Immune Cells by Spectral Flow Cytometry—A Comprehensive Validation Approach. iScience 2025, 28, 112894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mülling, N.; de Graaf, J.F.; Heieis, G.A.; Boss, K.; Wilde, B.; Everts, B.; Arens, R. Metabolic Profiling of Antigen-Specific CD8+ T Cells by Spectral Flow Cytometry. Cell Rep. Methods 2025, 5, 101185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clish, C.B. Metabolomics: An Emerging but Powerful Tool for Precision Medicine. Mol. Case Stud. 2015, 1, a000588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, C.; Chen, L.; Rabinowitz, J.D. Metabolomics and Isotope Tracing. Cell 2018, 173, 822–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, W.B.; Broadhurst, D.; Begley, P.; Zelena, E.; Francis-McIntyre, S.; Anderson, N.; Brown, M.; Knowles, J.D.; Halsall, A.; Haselden, J.N.; et al. Procedures for Large-Scale Metabolic Profiling of Serum and Plasma Using Gas Chromatography and Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2011, 6, 1060–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckonert, O.; Keun, H.C.; Ebbels, T.M.D.; Bundy, J.; Holmes, E.; Lindon, J.C.; Nicholson, J.K. Metabolic Profiling, Metabolomic and Metabonomic Procedures for NMR Spectroscopy of Urine, Plasma, Serum and Tissue Extracts. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2692–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idle, J.R.; Gonzalez, F.J. Metabolomics. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, Q.-H.; Nguyen, H.; Oh, E.C.; Nguyen, T. Current Approaches and Outstanding Challenges of Functional Annotation of Metabolites: A Comprehensive Review. Brief. Bioinform. 2024, 25, bbae498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keun, H.C.; Athersuch, T.J. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)-Based Metabolomics. In Metabolic Profiling: Methods and Protocols; Metz, T.O., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 321–334. ISBN 978-1-61737-985-7. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, C.; Le, A. The Limitless Applications of Single-Cell Metabolomics. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2021, 71, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Abouleila, Y.; Shimizu, Y.; Hiyama, E.; Emara, S.; Mashaghi, A.; Hankemeier, T. Single-Cell Metabolomics by Mass Spectrometry: Advances, Challenges, and Future Applications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 120, 115436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Huang, S.C.-C.; Sergushichev, A.; Lampropoulou, V.; Ivanova, Y.; Loginicheva, E.; Chmielewski, K.; Stewart, K.M.; Ashall, J.; Everts, B.; et al. Network Integration of Parallel Metabolic and Transcriptional Data Reveals Metabolic Modules That Regulate Macrophage Polarization. Immunity 2015, 42, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Astapova, I.; Zhang, G.; Cangelosi, A.L.; Ilkayeva, O.; Marchuk, H.; Muehlbauer, M.J.; George, T.; Brozinick, J.; Herman, M.A.; et al. Integration of Metabolomic and Transcriptomic Analyses Reveals Regulatory Functions of the ChREBP Transcription Factor in Energy Metabolism. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maan, K.; Baghel, R.; Dhariwal, S.; Sharma, A.; Bakhshi, R.; Rana, P. Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Based Multi-Omics Integration Reveals Radiation-Induced Altered Pathway Networking and Underlying Mechanism. npj Syst. Biol. Appl. 2023, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandor, S.; Agilent Technologies Inc. Extracellular Flux Analysis and 13C Stable-Isotope Tracing Reveals Metabolic Changes in LPS-Stimulated Macrophages; Agilent Technologies, Inc.: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Llufrio, E.M.; Wang, L.; Naser, F.J.; Patti, G.J. Sorting Cells Alters Their Redox State and Cellular Metabolome. Redox Biol. 2018, 16, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, K.; Rose, R.E.; Jones, D.R.; Lopez, P.A. Sheath Fluid Impacts the Depletion of Cellular Metabolites in Cells Afflicted by Sorting Induced Cellular Stress (SICS). Cytom. Part A 2021, 99, 921–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönberger, K.; Mitterer, M.; Glaser, K.; Stecher, M.; Hobitz, S.; Schain-Zota, D.; Schuldes, K.; Lämmermann, T.; Rambold, A.S.; Cabezas-Wallscheid, N.; et al. LC-MS-Based Targeted Metabolomics for FACS-Purified Rare Cells. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 4325–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekermanjian, J.P.; Shaddox, E.; Nandy, D.; Ghosh, D.; Kechris, K. Mechanism-Aware Imputation: A Two-Step Approach in Handling Missing Values in Metabolomics. BMC Bioinform. 2022, 23, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Wang, J.; Jia, E.; Chen, T.; Ni, Y.; Jia, W. GSimp: A Gibbs Sampler Based Left-Censored Missing Value Imputation Approach for Metabolomics Studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2018, 14, e1005973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Yadab, M.K.; Ali, M.M. Emerging Role of Extracellular pH in Tumor Microenvironment as a Therapeutic Target for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cells 2024, 13, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.-H.; Qiu, J.; O’Sullivan, D.; Buck, M.D.; Noguchi, T.; Curtis, J.D.; Chen, Q.; Gindin, M.; Gubin, M.M.; van der Windt, G.J.W.; et al. Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell 2015, 162, 1229–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmlinger, G.; Yuan, F.; Dellian, M.; Jain, R.K. Interstitial pH and pO2 Gradients in Solid Tumors in Vivo: High-Resolution Measurements Reveal a Lack of Correlation. Nat. Med. 1997, 3, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Simon, M.C. Cancer Cells Don’t Live Alone: Metabolic Communication within Tumor Microenvironments. Dev. Cell 2020, 54, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gika, H.; Virgiliou, C.; Theodoridis, G.; Plumb, R.S.; Wilson, I.D. Untargeted LC/MS-Based Metabolic Phenotyping (Metabonomics/Metabolomics): The State of the Art. J. Chromatogr. B 2019, 1117, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallart-Ayala, H.; Teav, T.; Ivanisevic, J. Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (HILIC–MS) Approaches for Probing the Polar Metabolome. In Advanced Mass Spectrometry-Based Analytical Separation Techniques for Probing the Polar Metabolome; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, M.; Lamont, L.; Maas, P.; Harms, A.C.; Beekman, M.; Slagboom, P.E.; Dubbelman, A.-C.; Hankemeier, T. Matrix Effect Evaluation Using Multi-Component Post-Column Infusion in Untargeted Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Plasma Metabolomics. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1740, 465580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Fedorova, M. Evaluation of Lipid Quantification Accuracy Using HILIC and RPLC MS on the Example of NIST® SRM® 1950 Metabolites in Human Plasma. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2020, 412, 3573–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, M.; Li, M.; Qin, S.; Miao, D.; Bai, Y. Dynamic Single-Cell Metabolomics Reveals Cell-Cell Interaction between Tumor Cells and Macrophages. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, N.; Yao, L.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, R.; Qian, J.; Hou, Y.; Guo, W.; Fan, S.; Liu, S.; et al. Moderate UV Exposure Enhances Learning and Memory by Promoting a Novel Glutamate Biosynthetic Pathway in the Brain. Cell 2018, 173, 1716–1727.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.H.; Verway, M.J.; Johnson, R.M.; Roy, D.G.; Steadman, M.; Hayes, S.; Williams, K.S.; Sheldon, R.D.; Samborska, B.; Kosinski, P.A.; et al. Metabolic Profiling Using Stable Isotope Tracing Reveals Distinct Patterns of Glucose Utilization by Physiologically Activated CD8+ T Cells. Immunity 2019, 51, 856–870.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, F.K.; Premkumar, V.; Zecha, J.; Boyd, J.; Gaynor, A.S.; Guo, Z.; Martin, T.; Cimbro, R.; Allman, E.L.; Hess, S. Multiomics Characterization of a Less Invasive Microfluidic-Based Cell Sorting Technique. J. Proteome Res. 2024, 23, 3096–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, M.; Potter, A.S.; Potter, S.S. Psychrophilic Proteases Dramatically Reduce Single-Cell RNA-Seq Artifacts: A Molecular Atlas of Kidney Development. Development 2017, 144, 3625–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wije Munige, S.; Bhusal, D.; Peng, Z.; Chen, D.; Yang, Z. Developing a Cell Quenching Method to Facilitate Single Cell Mass Spectrometry Metabolomics Studies. JACS Au 2025, 5, 2379–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.; Mousavi, F.; Blum, B.C.; Heckendorf, C.F.; Lawton, M.; Lampl, N.; Hekman, R.; Guo, H.; McComb, M.; Emili, A. PANAMA-Enabled High-Sensitivity Dual Nanoflow LC-MS Metabolomics and Proteomics Analysis. Cell Rep. Methods 2024, 4, 100803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, M.E.; Grinias, J.P.; Edwards, J.L. Evaluation of Nanospray Capillary LC-MS Performance for Metabolomic Analysis in Complex Biological Matrices. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1670, 462952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broeckhoven, K.; Desmet, G. The Future of UHPLC: Towards Higher Pressure and/or Smaller Particles? TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2014, 63, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanquish Neo UHPLC System—Beyond Brilliant—US. Available online: https://www.thermofisher.com/us/en/home/products-and-services/promotions/industrial/vanquish-neo-beyond-brilliant.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Aichler, M.; Walch, A. MALDI Imaging Mass Spectrometry: Current Frontiers and Perspectives in Pathology Research and Practice. Lab. Investig. 2015, 95, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Li, T.; Song, X.; Huang, L.; Zang, Q.; Xu, J.; Bi, N.; Jiao, G.; Hao, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Spatially Resolved Metabolomics to Discover Tumor-Associated Metabolic Alterations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, K.H.; Ebbini, M.; Huang, P.; Lu, H.; Li, L. Mass Spectrometry Imaging for Spatially Resolved Multi-Omics Molecular Mapping. Npj Imaging 2024, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unlu, G.; Prizer, B.; Erdal, R.; Yeh, H.-W.; Bayraktar, E.C.; Birsoy, K. Metabolic-Scale Gene Activation Screens Identify SLCO2B1 as a Heme Transporter That Enhances Cellular Iron Availability. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2832–2843.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birsoy, K.; Wang, T.; Chen, W.; Freinkman, E.; Abu-Remaileh, M.; Sabatini, D.M. An Essential Role of the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain in Cell Proliferation Is to Enable Aspartate Synthesis. Cell 2015, 162, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimitou, E.P.; Cheng, A.; Montalbano, A.; Hao, S.; Stoeckius, M.; Legut, M.; Roush, T.; Herrera, A.; Papalexi, E.; Ouyang, Z.; et al. Multiplexed Detection of Proteins, Transcriptomes, Clonotypes and CRISPR Perturbations in Single Cells. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 409–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datlinger, P.; Rendeiro, A.F.; Schmidl, C.; Krausgruber, T.; Traxler, P.; Klughammer, J.; Schuster, L.C.; Kuchler, A.; Alpar, D.; Bock, C. Pooled CRISPR Screening with Single-Cell Transcriptome Readout. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 297–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Replogle, J.M.; Saunders, R.A.; Pogson, A.N.; Hussmann, J.A.; Lenail, A.; Guna, A.; Mascibroda, L.; Wagner, E.J.; Adelman, K.; Lithwick-Yanai, G.; et al. Mapping Information-Rich Genotype-Phenotype Landscapes with Genome-Scale Perturb-Seq. Cell 2022, 185, 2559–2575.e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Extended Approaches | Cell Input Requirement | Throughput | Rare Cell Type Suitability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scRNA-seq | Computational scRNA-seq prediction (e.g., Compass)/Spatial transcriptomics (e.g., slide-seq) | 500 sequenced cells from specific population | High | Good | [13,14,15,16,17] |

| Extracellular flux analysis | scFBA | Depends on cell types 1 × 104 tumor cells/well 1 × 105 immune cells/well | Low | Low | [18,19] |

| MS | HILIC-MS/SCLIMS/MSI for spatial information | Conventional bulk LC-MS: 1 × 105~1 × 107 cells/sample Optimized targeted methods: 1 × 104 | Moderate-High | Bulk LC-MS: Low MSI/HILIC-MS: Good | [20,21,22,23,24,25,26] |

| Flow cytometry | Spectral flow cytometry-based panels (e.g., SCENITH, CENCAT)/hi-scMet | as low as 500 cells, depends on panel | High | Good | [27,28,29,30] |

| CRISPR screen | Perturb-seq | 1 × 106 cells | Very high | Good | [31,32,33,34,35,36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, Y.; Weinberg, S. Beyond Bulk Metabolomics: Emerging Technologies for Defining Cell-Type Specific Metabolic Pathways in Health and Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121687

Gong Y, Weinberg S. Beyond Bulk Metabolomics: Emerging Technologies for Defining Cell-Type Specific Metabolic Pathways in Health and Disease. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121687

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Yichen, and Samuel Weinberg. 2025. "Beyond Bulk Metabolomics: Emerging Technologies for Defining Cell-Type Specific Metabolic Pathways in Health and Disease" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121687

APA StyleGong, Y., & Weinberg, S. (2025). Beyond Bulk Metabolomics: Emerging Technologies for Defining Cell-Type Specific Metabolic Pathways in Health and Disease. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121687