Mechanistic Insights into the Metabolic Pathways and Neuroprotective Potential of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids: In-Depth Analysis of Betulin, Betulinic, and Ursolic Acids

Abstract

1. Introduction

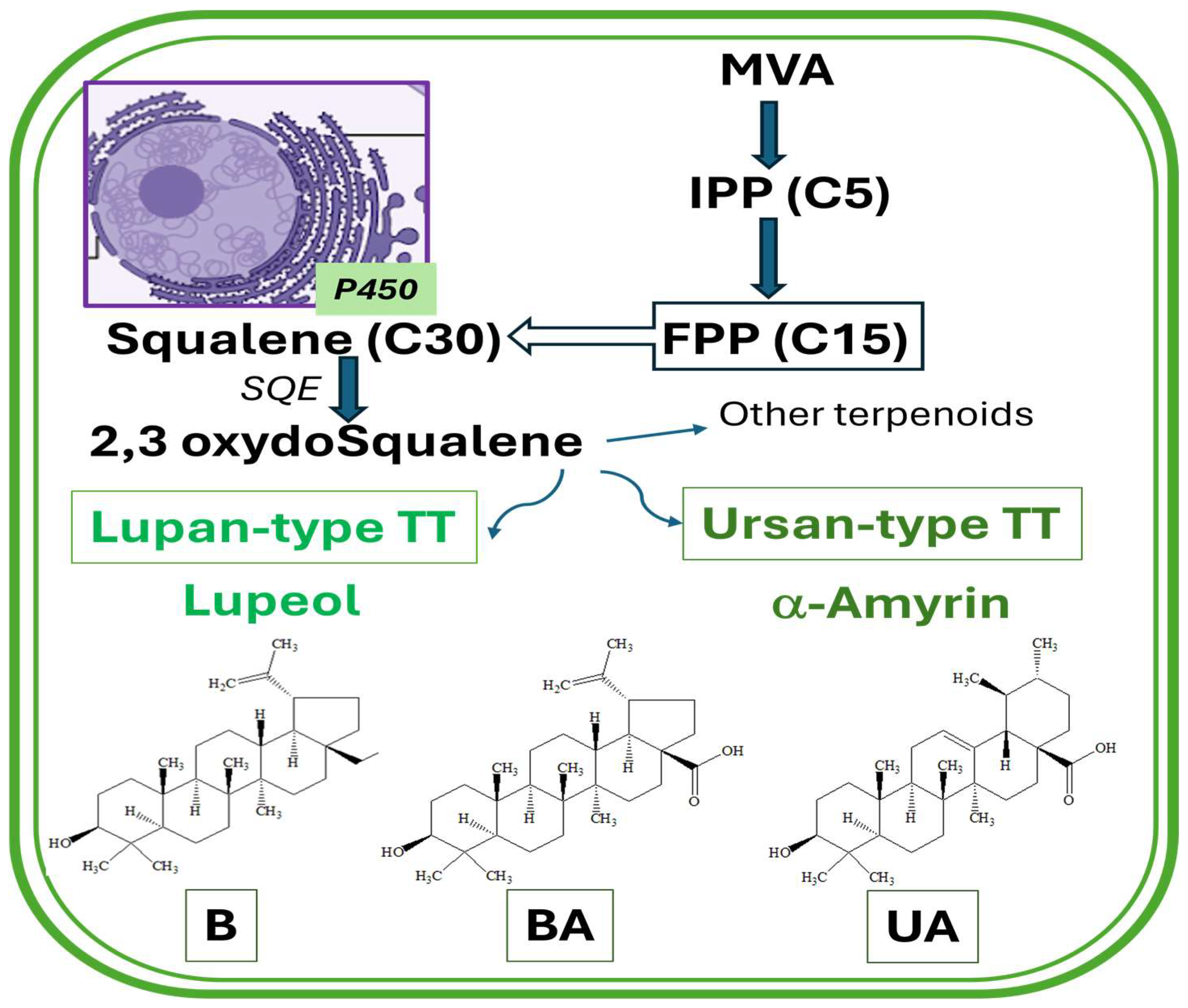

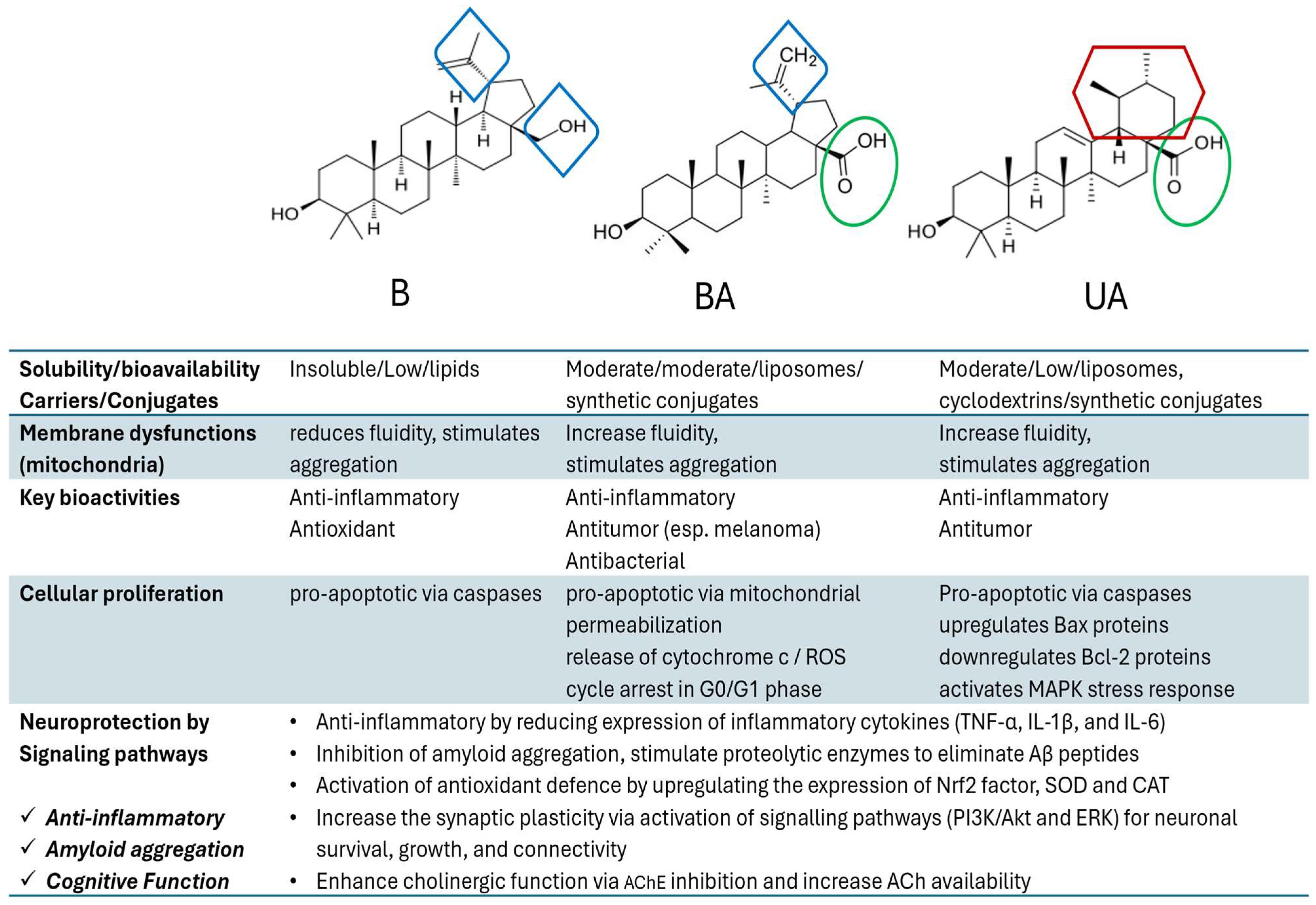

2. Pentacyclic Triterpenoids: Biosynthesis and Bioavailability

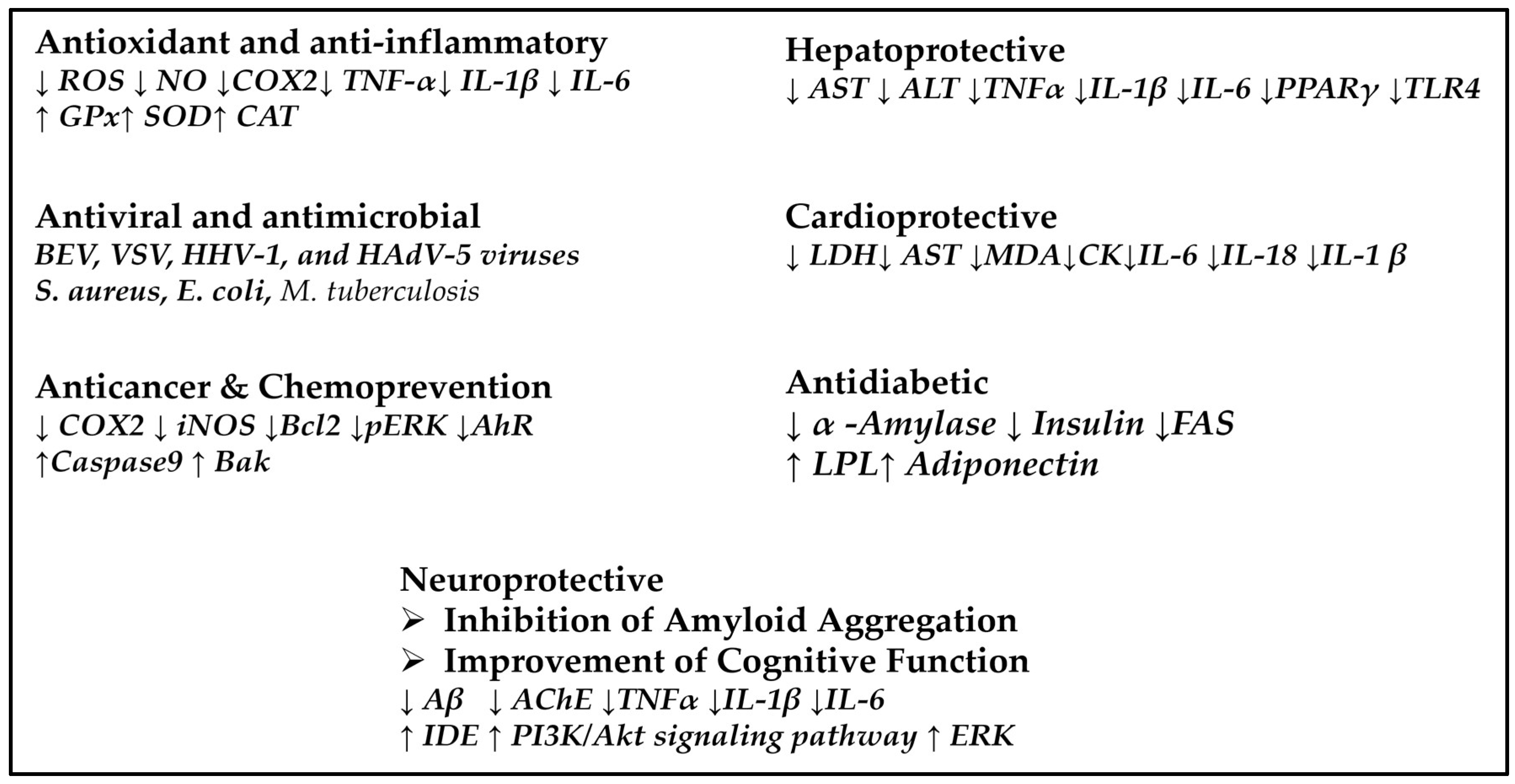

3. Biological Activity and Pharmacological Potential

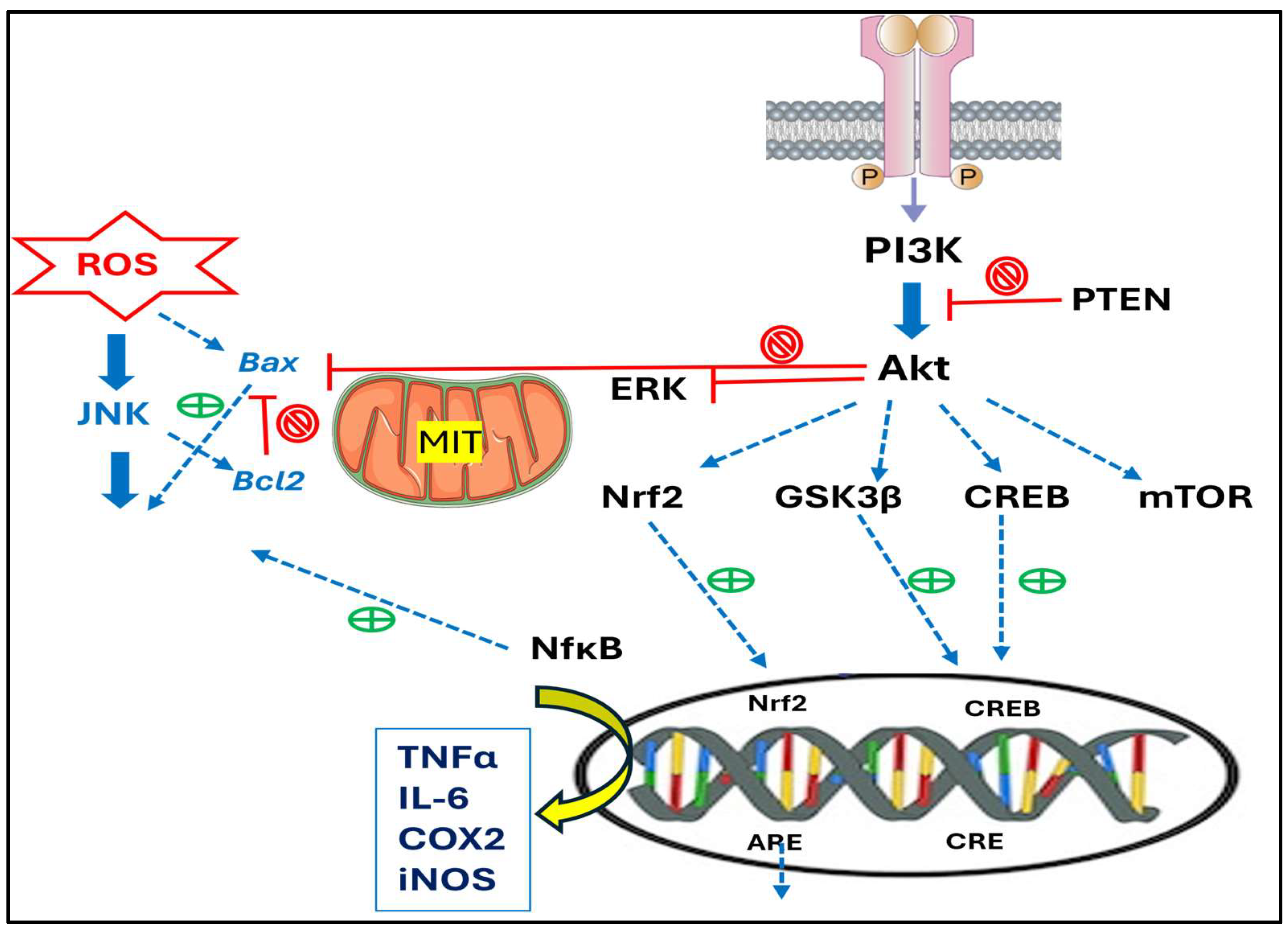

4. Mechanisms and Pathways Involved in Their Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Effects

5. Toxicity Versus Cytotoxicity

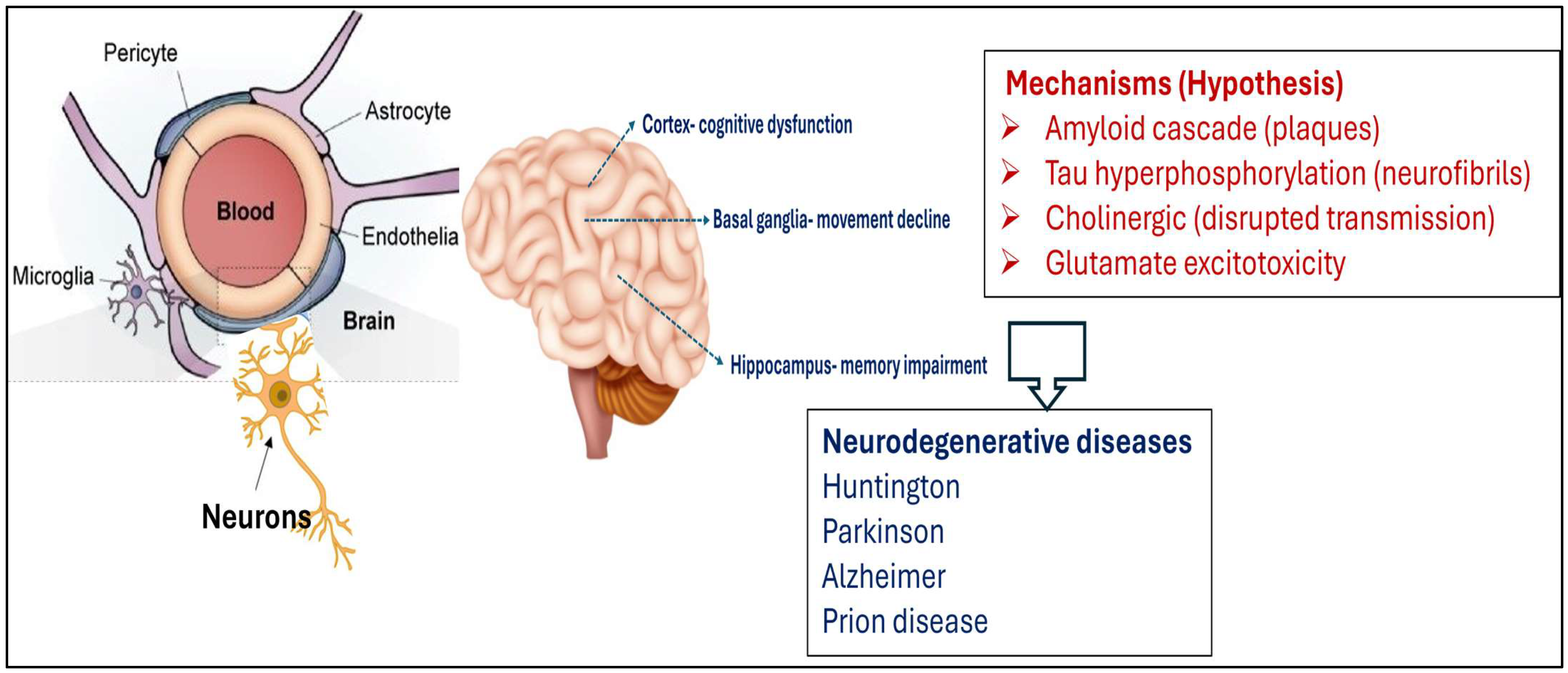

6. Neurodegeneration: General Mechanisms and Diseases

7. Neuroprotection: Experimental Data and Mechanisms of Action

- Anti-inflammatory activity. Since neuroinflammation and oxidative stress are central mechanisms to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, at the molecular level, TTs exert anti-inflammatory effects mainly by inhibiting key pro-inflammatory pathways, including the NFκB pathway. This inhibition leads to the reduced expression of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and interleukins IL-1β and IL-6. Additionally, TTs activate antioxidant defense mechanisms by upregulating the expression of nuclear factor Nrf2, which enhances the transcription of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and CAT. These actions reduce oxidative stress, considered a major contributor to neuronal damage and neurodegeneration, and therefore, TTs can modulate these pathways and can contribute to neuronal integrity and function.

- Inhibition of amyloid aggregation. Since the accumulation of Aβ plaques is a hallmark of AD, at the molecular level, TTs proved to interact directly with Aβ peptides, preventing their misfolding and subsequent aggregation into toxic oligomers and fibrils. These compounds disrupt the β-sheet-rich structure of Aβ aggregates and enhance the activity of proteolytic enzymes to eliminate the Aβ peptides. This dual action not only prevents new plaque formation but also promotes the degradation and removal of existing plaques, reducing neurotoxicity and supporting neuronal health.

- Improvement of Cognitive Function. First, TTs increase the synaptic plasticity via signaling pathways (PI3K/Akt and ERK), which are crucial for neuronal survival, growth, and connectivity. Secondly, TTs enhance the cholinergic function via inhibition of AChE and increase the availability of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter vital for learning and memory. Collectively, these actions synergistically support the preservation and enhancement of cognitive abilities.

8. Challenges and Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Name |

| A-Syn | Alpha-Synuclein |

| Ache | Acetylcholinesterase |

| AD | Alzheimer Disease |

| Aβ | Amyloid-Beta |

| Akt | Protein Kinase B |

| AMD3100 | A Chemokine Receptor CXCR4 Antagonist |

| B | Betulin |

| BA | Betulinic Acid |

| BAH | Betulinic Acid Hydroxamate |

| BAM | Betulinic Amine |

| BAX | Bcl2- Associated X |

| Bcl-2 | B-Cell Lymphoma 2 |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CREB | cAMP-Response Element Binding Protein |

| CT | Computer Tomogaphy |

| ER | Endoplasmic Reticulum |

| FT | Frontotemporal Dementia |

| Gpx | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Beta |

| GSSG | Glutathione Disulfide |

| HIF | Hypoxia-Nducing Factor |

| ICAM- 1 | Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1 |

| IDE | Insulin-Degrading Enzyme |

| IL1β | Interleukin -1β |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| I.H. | Intra-Hippocampal |

| I.V. | Intra-Venous |

| Inos | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| HD | Huntington’s Disease |

| IPP | Isopentenyl Diphosphate |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MEP | Methylerythritol Phosphate |

| MIT | Mitochondria |

| MMP | Matrix Metalloproteinase- |

| Mtco1 | Mitochondria Cytochrome Oxidase |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MVA | Cytosolic Mevalonic Acid |

| Mtor | Mammalian Target of Rapamycin |

| NF-Κb | Nuclear Factor-Κb |

| Nrf2 | Erythroid 2-Related Factor |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| Oscs | Oxidosqualene Cyclases |

| P450s | Cytochrome P450 Monooxygenases |

| PBS | Phosphate-Buffer Saline |

| PD | Parkinson Disease |

| PET | Tomography with Positron Emission |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PI | Phosphatydyl Inositol |

| Phds | Prolyl-Hydroxylases |

| PP2A | Phosphatase 2A |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| Shcs | Squalene-Hopene Cyclases |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| TBI | Traumatic Brain Injury |

| TLR4 | Toll-Like Receptor 4 |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-A |

| TyrOHase | Tyrosine Hydroxylase |

| UA | Ursolic Acid |

| UA-THP | Ursolic Acid Tetrahydroyridine Derivative |

References

- Bruce, S.O. In Secondary Metabolites from Natural Products; Vijayakumar, R., Sudalaimuthu Raja, S.S., Eds.; Secondary Metabolites—Trends and Reviews (Chapter 4). Intech Open: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Song, W.; Li, M.; Hua, X.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Xue, Z. Natural products of pentacyclic triterpenoids: From discovery to heterologous biosynthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 1303–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, M.E.; Davis, B.; Phillips, M.A. Medically Useful Plant Terpenoids: Biosynthesis, Occurrence, and Mechanism of Action. Molecules 2019, 24, 3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, C.; Abd El-Aty, A.M. Edible pentacyclic triterpenes: A review of their sources, bioactivities, bioavailability, self-assembly behavior, and emerging applications as functional delivery vehicles. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 64, 5203–5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, S.K.; Sharma, T.P.; Airao, V.B.; Bhatt, R.; Aghara, R.; Chavda, S.; Rabadiya, S.O.; Gangwal, A.P. Neuropharmacological effects of triterpenoids. Phytopharmacology 2013, 4, 354–372. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Bai, L.; Chen, L.; Tong, R.; Feng, Y.; Shi, J. Terpenoid natural products exert neuroprotection via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1036506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankar, A.A.; Nagulwar, V.P.; Kotagale, N.R.; Inamdar, N.N. Neuroprotective prospectives of triterpenoids. Explor. Neurosci. 2024, 3, 231–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Kwon, R.J.; Lee, H.S.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Jeong, H.-S.; Park, S.-J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, T.; Yoon, S.H. The Role of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: The Mechanisms of Action and Therapeutic Potential. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimmer, Z. Selected Pentacyclic Triterpenoids and Their Derivatives as Biologically Active Compounds. Molecules 2025, 30, 3106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawai, S.; Saito, K. Triterpenoid biosynthesis and engineering in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2011, 2, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinday, S.; Ghosh, S. Recent advances in triterpenoid pathway elucidation and engineering. Biotech. Adv. 2023, 68, 108214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanani, M.; Fukushima, E.O.; Sawai, S.; Tang, J.; Ishimori, M.; Sudo, H.; Ohyama, K.; Seki, H.; Saito, K.; Muranaka, T. Molecular Basis of C-30 Product Regioselectivity of Legume Oxidases Involved in High-Value Triterpenoid Biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas, P.D.; Almeida, A.; Bak, S. Evolution of Structural Diversity of Triterpenoids. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 486054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimmappa, R.; Geisler, K.; Louveau, T.; O’Maille, P.; Osbourn, A. Triterpene biosynthesis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014, 65, 225–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunanithi, P.S.; Zerbe, P. Terpene Synthases as Metabolic Gatekeepers in the Evolution of Plant Terpenoid Chemical Diversity. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunha, A.B.; Batista, R.; Castro, M.Á.; David, J.M. Chemical strategies towards the synthesis of betulinic acid and its more potent antiprotozoal analogues. Molecules 2021, 26, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.Y.; Lee, S.R.; Heo, J.W.; No, M.H.; Rhee, B.D.; Ko, K.S.; Kwak, H.B.; Han, J. Ursolic acid in health and disease. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2018, 22, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, J. Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases; United States Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Shinbo, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Altaf-Ul-Amin, M.; Asahi, H.; Kurokawa, K.; Arita, M.; Saito, K.; Ohta, D.; Shibata, D.; Kanaya, S. KNApSAcK: A comprehensive species-metabolite relationship database. In Plant Metabolomics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ayeleso, T.B.; Matumba, M.G.; Mukwevho, E. Oleanolic Acid and Its Derivatives: Biological Activities and Therapeutic Potential in Chronic Diseases. Molecules 2017, 22, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, N.; Singh, N.; Singh, A.P.; Singh, A.P. Medicinal Uses of Maslinic Acid: A Review. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2021, 11, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Wang, H.; Mu, X.; He, X.; Zhao, F.; Meng, Q. Advances in research on the preparation and biological activity of maslinic acid. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2021, 21, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Liu, L.; Huang, X.; Quan, Z.-S.; Shen, Q.-K.; Guo, H.-Y. Bioactivities and structure-activity relationships of maslinic acid derivatives: A review. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202301327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, Z.; Imran, M.; Hussain, M.; Saeed, F.; Imran, A.; Umar, M.; Abdelgawad, M.A.; El-Ghorab, A.H.; Ahmed, A.; Alsagaby, S.A.; et al. Asiatic acid: A review on its polypharmacological properties and therapeutic potential against various Maladies. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 1244–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoof, G.F.A.; Mohamed, K.Y. In Studies in Natural Products Chemistry; Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Natural Products for the Management of Diabetes. Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 59, pp. 323–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahnt, M.; Heller, L.P.; Grabandt, P.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Csuk, R. Platanic acid: A new scaffold for the synthesis of cytotoxic agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 143, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teng, W.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, J.; Guo, Q. Recent Advances of Natural Pentacyclic Triterpenoids as Bioactive Delivery System for Synergetic Biological Applications. Foods 2024, 13, 2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bag, B.G.; Majumdar, R. Self-assembly of Renewable Nano-sized Triterpenoids. Chem. Rec. 2017, 17, 841–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socaciu, C.; Socaciu, M.A. Microscopy of betulins’ nanoformulations: Solubility and sizes. Biodiatech RTD, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2025 (manuscript in preparation).

- Adepoju, F.O.; Duru, K.C.; Li, E.; Kovaleva, E.G.; Tsurkan, M.V. Pharmacological Potential of Betulin as a Multitarget Compound. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šiman, P.; Bezrouk, A.; Tichá, A.; Kozáková, H.; Hudcovic, T.; Kučera, O.; Niang, M. Promising Protocol for In Vivo Experiments with Betulin. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, N.A.J.C.; Pirson, L.; Edelberg, H.; Miranda, L.M.; Loira-Pastoriza, C.; Preat, V.; Larondelle, Y.; André, C.M. Pentacyclic Triterpene Bioavailability: An Overview of In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Molecules 2017, 22, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszewski, B.; Jelonek, K.; Kasperczyk, J. Drug Delivery Systems of Betulin and Its Derivatives: An Overview. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Socaciu, C.; Fetea, F.; Socaciu, M.A. Synthesis and Characterization of PEGylated Liposomes and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers with Entrapped Bioactive Triterpenoids: Comparative Fingerprints and Quantification by UHPLC-QTOF-ESI+-MS, ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy, and HPLC-DAD. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 18, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugină, D.; Socaciu, M.A.; Nistor, M.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Cenariu, M.; Tabaran, F.A.; Socaciu, C. Liposomal and Nanostructured Lipid Nanoformulations of a Pentacyclic Triterpenoid Birch Bark Extract: Structural Characterization and In Vitro Effects on Melanoma B16-F10 and Walker 256 Tumor Cells Apoptosis. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nistor, M.; Rugină, D.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Socaciu, C.; Socaciu, M.A. Pentacyclic Triterpenoid Phytochemicals with Anticancer Activity: Updated Studies on Mechanisms and Targeted Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payamnoor, V.; Mohammadi, H.; Pourashouri, P.; Kavosi, M.R.; Nazari, J. Nanoliposomal encapsulation approach for enhancing the anticancer biological compounds produced in birch callus cell extracts. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2025, 161, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowski, A.; Jaromin, A.; Migdał, P.; Olczak, E.; Zygmunt, A.; Zaremba-Czogalla, M.; Pawlik, K.; Gubernator, J. Design and Development of a New Type of Hybrid PLGA/Lipid Nanoparticle as an Ursolic Acid Delivery System against Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, J.; Mandal, S.C. Pentacyclic triterpenoids: Diversity, distribution and their propitious pharmacological potential. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 24, 4791–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalimunthe, A.; Gunawan, M.C.; Utari, Z.D.; Dinata, M.R.; Halim, P.; Pakpahan, N.E.S.; Sitohang, A.I.; Sukarno, M.A.; Harahap, Y.; Setyowati, E.P.; et al. In-depth analysis of lupeol: Delving into the diverse pharmacological profile. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1461478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, A.A.M.; Hossain, T.; Rahaman, A.; Rahman, P.; Hasan, M.S.; Das, R.C.; Khan, K.; Sikder, M.H.; Alam, M.; Uddin, J.; et al. Molecular pharmacology and therapeutic advances of the pentacyclic triterpene lupeol. Phytomedicine 2022, 99, 154012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hordyjewska, A.; Ostapiuk, A.; Horecka, A. Betulin and betulinic acid: Triterpenoids derivatives with a powerful biological potential. Phytochem. Rev. 2019, 18, 929–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolstikov, G.A.; Flekhter, O.B.; Shultz, E.E.; Baltina, L.A.; Tolstikov, A.G. Betulin and Its Derivatives. Chemistry and Biological Activity. Chem. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 13, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Jäger, S.; Laszczyk, M.; Scheffler, A. A Preliminary Pharmacokinetic Study of Betulin, the Main Pentacyclic Triterpene from Extract of Outer Bark of Birch (Betulae alba cortex). Molecules 2008, 13, 3224–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, M.G.; Ahmad, F.B.H.; Kermani, A.S. Biological activity of betulinic acid: A review. Pharmacol. Pharm. 2012, 3, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Qin, P.; Cheng, X.; Wu, L.; Wang, R.; Gao, W. Ursolic acid: Biological functions and application in animal husbandry. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1251248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlala, S.; Oyedeji, A.O.; Gondwe, M.; Oyedeji, O.O. Ursolic acid and its derivatives as bioactive agents. Molecules 2019, 24, 2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Xiong, Y. Recent Advances in Antiviral Activities of Triterpenoids. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chudzik, M.; Korzonek-Szlacheta, I.; Król, W. Triterpenes as Potentially Cytotoxic Compounds. Molecules 2015, 20, 1610–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loboda, A.; Rojczyk-Golebiewska, E.; Bednarczyk-Cwynar, B.; Zaprutko, L.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J. Targeting Nrf2-mediated gene transcription by triterpenoids and their derivatives. Biomol. Ther. 2012, 20, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, M.K.; Sung, B.; Aggarwal, B.B. Betulinic acid suppresses STAT3 activation pathway through induction of protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP1 in human multiple myeloma cells. Int. J. Cancer 2010, 127, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.Y.; Zhang, M.; Fang, G.; Cheng, C.J.; Wang, M.K.; Han, Y.M.; Hou, X.T.; Hao, E.W.; Hou, Y.Y.; Bai, G. Ursolic acid reduces hepatocellular apoptosis and alleviates alcohol-induced liver injury via irreversible inhibition of CASP3 in vivo. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.W.C.; Soon, C.Y.; Tan, J.B.L.; Wong, S.K.; Hui, Y.W. Ursolic Acid: An Overview on Its Cytotoxic Activities Against Breast and Colorectal Cancer Cells. J. Integr. Med. 2019, 17, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Meng, R.Y.; Nguyen, T.V.; Chai, O.H.; Park, B.H.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.M. Inhibition of colorectal cancer tumorigenesis by ursolic acid and doxorubicin is mediated by targeting the Akt signaling pathway and activating the Hippo signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 27, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.U.; Luo, L.; Namani, A.; Wang, X.J.; Tang, X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, N.A.; Alshammari, S.O.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Alshammari, Q.A.; Elkamhawy, A. Therapeutic potential of natural products in inflammation: Underlying molecular mechanisms, clinical outcomes, technological advances, and future perspectives. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 2857–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safayhi, H.; Sailer, E.-R. Antinflammatory actions of pentacyclic triterpenes. Planta Med. 1997, 63, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantiniotou, M.; Athanasiadis, V.; Kalompatsios, D.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.I. Therapeutic Capabilities of Triterpenes and Triterpenoids in Immune and Inflammatory Processes: A Review. Compounds 2025, 5, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anikina, L.V.; Tolmacheva, I.A.; Vikharev, Y.B.; Grishko, V.V. The immunotropic activity of lupane and oleanane 2,3-seco-triterpenoids. Russ. J. Bioorganic Chem. 2010, 36, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemli, E.; Saricaoglu, B.; Kirkin, C.; Ozkan, G.; Capanoglu, E.; Habtemariam, S.; SharifRad, J.; Calina, D. Chemopreventive and Chemotherapeutic Potential of Betulin and Betulinic Acid: Mechanistic Insights From In Vitro, In Vivo and Clinical Studies. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 10059–10069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuli, H.S.; Sak, K.; Gupta, D.S.; Kaur, G.; Aggarwal, D.; Parashar, N.C.; Choudhary, R.; Yerer, M.B.; Kaur, J.; Kumar, M.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Anticancer Properties of Birch Bark-Derived Betulin: Recent Developments. Plants 2021, 10, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laavola, M.; Haavikko, R.; Hämäläinen, M.; Leppänen, T.; Nieminen, R.; Alakurtti, S.; Moreira, V.M.; Yli-Kauhaluoma, J.; Moilanen, E. Betulin Derivatives Effectively Suppress Inflammation In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Nat. Prod. 2016, 79, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, C.; Jin, J.; Hu, W.; Chen, Q.; Yang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, L.; Gao, W.; Zhang, X.; et al. Betulin Alleviates the Inflammatory Response in Mouse Chondrocytes and Ameliorates Osteoarthritis via AKT/Nrf2/HO-1/NF-B Axis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 754038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Niu, S.; Sun, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J. Antinflammatory action of betulin and its potential as a dissociated glucocorticoid receptor modulator. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 157, 112539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Zhao, Q.F.; Fang, N.N.; Yu, J.G. Betulin inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokines expression through activation STAT3 signaling pathway in human cardiac cells. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 19, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prakash, D.; Chaudhary, A.; Chaudhary, A. Betulin-NLC-hydrogel for the Treatment of Psoriasis like Skin Inflammation: Optimization, Characterisation, and In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2025, 22, 627–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osunsanmi, F.O.; Zharare, G.E.; Mosa, R.A.; Ikhile, M.I.; Shode, F.O.; Opoku, A.R. Antoxidant, antinflammatory and antacetylcholinesterase activity of betulinic acid and 3β-acetoxybetulinic acid from Melaleuca bracteata Revolution Gold. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2019, 18, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, C.P.; Núñez, M.J.; Jiménez, I.A.; Busserolles, J.; Alcaraz, M.J.; Bazzocchi, I.L. Activity of lupane triterpenoids from Maytenus species as inhibitors of nitric oxide and prostaglandin E2. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seca, A.M.L.; Pinto, D.C.G.A. Plant Secondary Metabolites as Anticancer Agents: Successes in Clinical Trials and Therapeutic Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markov, A.; Logashenko, E.; Zenkova, M. Modulation of Tumour-Related Signaling Pathways By Natural Pentacyclic Triterpenoids and Their Semisynthetic Derivatives. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 1277–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- In New Approaches to Natural Anticancer Drugs; Saeidnia, S., Ed.; Anticancer Terpenoids. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhimli, B.; Sovan, S.; Rubai, A.; Sandeep, D.K. Bioactive Pentacyclic Triterpenes Trigger Multiple Signalling Pathways for Selective Apoptosis Leading to Anticancer Efficacy: Recent Updates and Future Perspectives. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2023, 24, 820–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghante, M.H.; Jamkhande, P.G. Role of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in Chemoprevention and Anticancer Treatment: An Overview on Targets and Underling Mechanisms. J. Pharmacopunct. 2019, 22, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laszczyk, M.N. Pentacyclic triterpenes of the lupane, oleanane and ursane group as tools in cancer therapy. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, M.; Nguyen, A.H.; Kumar, A.P.; Tan, B.; Sethi, G. Targeted inhibition of tumor proliferation, survival, and metastasis by pentacyclic triterpenoids: Potential role in prevention and therapy of cancer. Cancer Lett. 2012, 320, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Similie, D.; Minda, D.; Bora, L.; Kroškins, V.; Lugiņina, J.; Turks, M.; Dehelean, C.A.; Danciu, C. An Update on Pentacyclic Triterpenoids Ursolic and Oleanolic Acids and Related Derivatives as Anticancer Candidates. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, S.S.; Rouz, S.K.; Kumar, S.; Swamy, N.; Deshmukh, L.; Hussain, A.; Haque, S.; Tuli, H.S. Ursolic acid: A pentacyclic triterpenoid that exhibits anticancer therapeutic potential by modulating multiple oncogenic targets. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2023, 39, 729–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.-X.; Kang, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, H.-F.; Bao, Y.-R.; Li, Y.-W.; Li, X.-Z.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, G. Triterpenoids from Liquidambar Fructus induced cell apoptosis via a PI3K-AKT related signal pathway in SMMC7721 cancer cells. Phytochemistry 2020, 171, 112228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswathy, M.; Vijayan, A.; Daimary, U.D.; Girisa, S.; Radhakrishnan, K.V.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Betulinic acid: A natural promising anticancer drug, current situation, and future perspectives. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2022, 36, e23206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Liang, N.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, M.-S. Recent progress on betulinic acid and its derivatives as antitumor agents: A mini review. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2021, 19, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Song, G.; Jin, N.; Fang, J.; Han, J.; et al. Betulinic acid inhibits growth of hepatoma cells through activating the NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 102, 105441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morparia, S.; Metha, C.; Suvarna, V. Recent advancements of betulinic acid-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy (2002–2023). Nat. Prod. Res. 2024, 39, 3260–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Switalska, M.; Chrobak, E.; Kadela-Tomanek, M.; Wietrzyk, J.; Bebenek, E. Betulin Hippuric Acid Conjugates: Chemistry, Antiproliferative Activity and Mechanism of Action. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłos, P.; Chlubek, D. Plant-Derived Terpenoids: A Promising Tool in the Fight Against Melanoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grudzinska, M.; Stachnik, B.; Galanty, A.; Sołtys, A.; Podolak, I. Progress in Antimelanoma Research of Natural Triterpenoids and Their Derivatives: Mechanisms of Action, Bioavailability Enhancement and Structure Modifications. Molecules 2023, 28, 7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aly, S.H.; Elbadry, A.M.M.; Doghish, A.S.; El-Nashbar, H.A.S. Unveiling the pharmacological potential of plant triterpenoids in breast cancer management: An updated review. NaunySchmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 5571–5596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, R.; Dalal, B.; Shankarkumar, A.; Devarajan, P.V. Innovative Betulin Nanosuspension exhibits enhanced anticancer activity in a Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cell line and Zebrafish angiogenesis model. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 600, 120511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajbhiye, S.A.; Patil, M.P. Breast cancer cell targeting of L-leuciPLGA conjugated hybrid solid lipid nanoparticles of betulin via L-amino acid transport system-1. J. Drug Target. 2025, 33, 1432–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yim, N.H.; Jung, Y.P.; Kim, A.; Kim, T.; Ma, J.Y. Induction of apoptotic cell death by betulin in multidrug-resistant human renal carcinoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 34, 1058–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drag, M.; Surowiak, P.; Drag-Zalesinska, M.; Dietel, M.; Lage, H.; Oleksyszyn, J. Comparision of the cytotoxic effects of birch bark extract, betulin and betulinic acid towards human gastric carcinoma and pancreatic carcinoma drug-sensitive and drug-resistant cell lines. Molecules 2009, 14, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej, M.; Gola, J.; Chrobak, E. Synthesis, Pharmacological Properties, and Potential Molecular Mechanisms of Antitumor Activity of Betulin and Its Derivatives in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bębenek, E.; Chrobak, E.; Piechowska, A.; Głuszek, S.; Boryczka, S. Betulin: A natural product with promising anticancer activity against colorectal cancer cells. Stud. Med. 2020, 36, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Liu, H.; Song, Z.; Chen, W. Phytochemical compounds targeting on Nrf2 for chemoprevention in colorectal cancer. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 887, 173588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Wang, D.; Sennari, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Baba, R.; Morimoto, H.; Kitamura, N.; Nakanishi, T.; Tsukada, J.; Ueno, M.; et al. Pentacyclic triterpenoid ursolic acid induces apoptosis with mitochondrial dysfunction in adult T-cell leukemia MT-4 cells to promote surrounding cell growth. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, T.; Yuan, H.; Li, D.; Lou, H.; Fan, P. Mitochondria-Targeted Lupane Triterpenoid Derivatives and Their Selective Apoptosis Inducing Anticancer Mechanisms. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 6353–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubinin, M.V.; Semenova, S.A.A.; Ilzorkina, A.I.; Mikheeva, I.B.; Yashin, V.A.; Penkov, N.V.; Vydrina, V.A.; Ishmuratov, G.I.; Sharapov, V.A.; Khoroshavina, E.I.; et al. Effect of betulin and betulonic acid on isolated rat liver mitochondria and liposomes. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2020, 1862, 183383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubinin, M.V.; Semenova, A.A.; Nedopekina, D.A.; Davletshin, E.V.; Spivak, A.Y.; Belosludtsev, K.N. Effect of F16-Betulin Conjugate on Mitochondrial Membranes and Its Role in Cell Death Initiation. Membranes 2021, 11, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsepaeva, O.V.; Salikhova, T.I.; Ishkaeva, R.A.; Kundina, A.V.; Abdullin, T.I.; Laikov, A.V.; Tikhomirova, M.V.; Idrisova, L.R.; Nemtarev, A.V.; Mironov, V.F. Bifunctionalized Betulinic Acid Conjugates with C-3-Monodesmoside and C-28-Triphenylphosphonium Moieties with Increased Cancer Cell Targetability. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 1939–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarova, M.; Shikov, A.; Avdeeva, O.I.; Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Makarenko, I.; Makarov, V.G.; Djachuk, G.I. Evaluation of acute toxicity of betulin. Planta Medica 2011, 77, 1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Soren, A.D.; Yadav, A.K. Toxicological evaluations of betulinic acid and ursolic acid; common constituents of Houttuynia cordata used as an anthelmintic by the Naga tribes in North-east India. Futur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 7, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, W.K.; Gomidec, A.B.; Costae, E.T.; Junqueira, H.C.; Stolf, B.S.; Itri, R.; Baptista, M.S. Membrane damage by betulinic acid provides insights into cellular aging. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2017, 1861, 3129–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitler, A.D.; Dhillon, P.; Shorter, J. Neurodegenerative disease: Models, mechanisms, and A new hope. Dis. Model. Mech. 2017, 10, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.M.; Ke, Y.D.; Vucic, S.; Ittner, L.M.; Seeley, W.; Hodges, J.R.; Piguet, O.; Halliday, G.; Kiernan, M.C. Physiological changes in neurodegeneration—Mechanistic insights and clinical utility. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patabendige, A.; Janigro, D. The role of the blood–brain barrier during neurological disease and infection. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2023, 51, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullotta, G.S.; Costantino, G.; Sortino, M.A.; Spampinato, S.F. Microglia and the Blood–Brain Barrier: An External Player in Acute and Chronic Neuroinflammatory Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, J.D.; Seeher, K.M.; Schiess, N.; Nichols, E.; Cao, B.; Servili, C.; Cavallera, V.; Cousin, E.; Hagins, H.; Moberg, M.E.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol. 2024, 23, 344–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolmaleky, H.M.; Zhou, J.R. Underlying Mechanisms of Brain Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases as Potential Targets for Preventive or Therapeutic Strategies Using Phytochemicals. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruszkowski, P.; Bobkiewicz-Kozlowska, T. Natural Triterpenoids and their Derivatives with Pharmacological Activity Against Neurodegenerative Disorders. MiniRev. Org. Chem. 2014, 11, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belgacem, Y.H.; Borodinsky, L. CREB at the crossroads of activity dependent regulation of nervous system development and function. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1015, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominiak, A.; Gawinek, E.; Banaszek, A.A.; Wilkaniec, A. Mitochondrial Quality Control in Neurodegeneration and Cancer: A Common Denominator, Distinct Therapeutic Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beal, M.F. Therapeutic approaches to mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2009, 15, S189–S194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, A.; Ziemichód, W.; Herbet, M.; Piątkowska-Chmiel, I. The Role of Diet as a Modulator of the Inflammatory Process in Neurological Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, J.R.; Puri, S.; Meyers, S.P. Multimodality imaging of neurodegenerative disorders with a focus on multiparametric magnetic resonance and molecular imaging. Insights Imaging 2023, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, P.N.E.; Estarellas, M.; Coomans, E.; Srikrishna, M.; Beaumont, H.; Maass, A.; Venkataraman, A.V.; Lissaman, R.; Jiménez, D.; Betts, M.J.; et al. Imaging biomarkers in neurodegeneration: Current and future practices. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Cho, E.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, J. Development of Neurodegenerative Disease Diagnosis and Monitoring from Traditional to Digital Biomarkers. Biosensors 2025, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Lankatillake, C.; Dias, D.A.; Docea, A.D.; Fawzi, M.; Lobine, D.; Chazot, P.L.; Begüm, K.; Tugba, T.; Moreira, A.; et al. Impact of Natural Compounds on Neurodegenerative Disorders: From Preclinical to Pharmacotherapeutics. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, D.W.; Lee, J.-E.; Lee, C.; Kim, Y.T. Natural Products and Their Neuroprotective Effects in Degenerative Brain Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Chen, X.; Li, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, Z.; Yu, X. Advances in Pharmacological Activities of Terpenoids. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20903555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, E.P.; Laurindo, L.F.; Catharin, V.C.S.; Direito, R.; Tanaka, M.; German, I.J.S.; Lamas, C.B.; Guiguer, E.L.; Araújo, A.C.; Fiorini, A.M.R.; et al. Polyphenols, Alkaloids, and Terpenoids Against Neurodegeneration: Evaluating the Neuroprotective Effects of Phytocompounds Through a Comprehensive Review of the Current Evidence. Metabolites 2025, 15, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Ahmed, I.; Mubarika, A.; Khan, F.; Khan, H. In Phytonutrients and Neurological Disorders; Khan, H., Aschner, M., Mirzaei, H., Eds.; Neuroprotective effect of terpenoids, Chapter 8. Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2023; pp. 227–244. ISBN 9780128244678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhri, S.; Iranpanah, A.; Gravandi, M.M.; Moradi, S.Z.; Ranjbari, M.; Majnooni, M.B.; Echeverría, J.; Qi, Y.; Wang, M.; Liao, P. Natural products attenuate PI3k/AKT/mtor signaling pathway: A promising strategy in regulating neurodegeneration. Phytomedicine 2021, 91, 153664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, B.; Mukerjee, N.; Maitra, S.; Zehravi, M.; Mukherjee, D.; Ghosh, A.; Massoud, E.E.S.; Rahman, M.H. Therapeutic Potential of Different Natural Products for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 6873874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Drew, J.; Berney, W.; Lei, W.J.C. Neuroprotective natural products for Alzheimer’s disease. Cells 2021, 10, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Lv, N.; Wang, L.; Gan, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; Yang, L. Therapeutic Candidates for Alzheimer’s Disease: Saponins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Rehman, I.U.; Choe, K.; Ahmad, R.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, M.O. A Triterpenoid Lupeol as an Antioxidant and AntNeuroinflammatory Agent: Impacts on Oxidative Stress in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzan, M.; Farzan, M.; Shahrani, M.; Navabi, S.P.; Vardanjani, H.R.; AminKhoei, H.; Shabani, S. Neuroprotective properties of Betulin, Betulinic acid, and Ursolic acid as triterpenoids derivatives: A comprehensive review of mechanistic studies. Nutr. Neurosci. 2024, 27, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habtemariam, S. Antioxidant and Antinflammatory Mechanisms of Neuroprotection by Ursolic Acid: Addressing brain injury, cerebral ischemia, cognition deficit, anxiety, and depression. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 512048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaidery, N.A.; Banerjee, R.; Yang, L.; Smirnova, N.A.; Hushpulian, D.M.; Liby, K.T.; Williams, C.R.; Yamamoto, M.; Kensler, T.W.; Ratan, R.R.; et al. Targeting Nrf2-mediated gene transcription by extremely potent synthetic triterpenoids attenuate dopaminergic neurotoxicity in the MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2013, 18, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Cui, J.; Sun, Z.; Chen, F.; He, X. Exploring the protective effect and molecular mechanism of betulin in Alzheimer’s disease based on network pharmacology, molecular docking and experimental validation. Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 30, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudoityte, E.; Arandarcikaite, O.; Mazeikiene, I.; Bendokas, V.; Liobikas, J. Ursolic and oleanolic acids: Plant metabolites with neuroprotective potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Ai, Q.; Shi, A.; Wang, N.; Wang, L.; Wei, Y. Oleanolic acid and ursolic acid: Therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative diseases, neuropsychiatric diseases and other brain disorders. Nutr. Neurosci. 2022, 26, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, L.; Gaire, B.P.; Kim, S.-Y.; Parveen, A. Nitric Oxide as a Target for Phytochemicals in Anti-Neuroinflammatory Prevention Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Xiao, C.; Zheng, J.; Ye, C.; Dai, Z.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J.; Strappe, P.; Zhou, Z. Terpenoids of Ganoderma lucidum reverse cognitive impairment through attenuating neurodegeneration via suppression of PI3K/AKT/mTOR expression in vivo model. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 73, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valotto Neto, L.J.; Reverete de Araujo, M.; Moretti Junior, R.C.; Mendes Machado, N.; Joshi, R.K.; dos Santos Buglio, D.; Barbalho Lamas, C.; Direito, R.; Fornari Laurindo, L.; Tanaka, M.; et al. Investigating the Neuroprotective and Cognitive-Enhancing Effects of Bacopa monnieri: A Systematic Review Focused on Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Apoptosis. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.J.; Park, H.J.; Yoo, H.M.; Cho, N. Betulin Protects HT-22 Hippocampal Cells against ER Stress through Induction of Heme Oxygenase-1 and Inhibition of ROS Production. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X19896684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, J.P.; Mei, J.H.; Li, S.J.; Shi, L.Q.; Lin, Z.H.; Xie, B.Y.; Sun, W.G.; Wang, Z.Y.; Yang, X.L.; et al. Betulin isolated from Pyrola incarnata Fisch. inhibited lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced neuroinflammation with the guidance of computer-aided drug design. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 30, 127193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakrzeska, A.; Kołodziejczyk, A.; Komorowski, P.; Sokołowska, P.; Rokita, B.; Wach, R.A.; Siatkowska, M. Neuroprotective Potential of Betulin and Its Drug Formulation with Cyclodextri In Vitro Assessment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.L.; Kuzmanoff, K.L.; Ling-Indeck, L.; Pezzuto, J.M. Betulinic acid induces apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cell lines. Eur. J. Cancer 1997, 33, 2007–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fulda, S.; Debatin, K.M. Betulinic acid induces apoptosis through a direct effect on mitochondria in neuroectodermal tumors. Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 2000, 35, 616–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salau, V.F.; Erukainure, O.L.; Ayeni, G.; Ibeji, C.U.; Olasehinde, T.A.; Chukwuma, C.I.; Koorbanally, N.A.; Islam, S. Betulinic Acid Modulates Redox Imbalance and Dysregulated Metabolisms, While Ameliorating Purinergic and Cholinergic Activities in Iron-Induced Neurotoxicity. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2023, 33, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, H.; Feng, Y.; Tang, F.; Hoi, M.P.M.; He, C.; Ma, D.; Zhao, C.; Lee, S.M.Y. Inhibitory Effects of Betulinic Acid on LP-Induced Neuroinflammation Involve M2 Microglial Polarization via CaMKKβ-Dependent AMPK Activation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, B.R.R.; Aragão-França, L.S.; Sampaio, G.L.A.; Nonaka, C.K.V.; Oliveira, M.S.; Campos, G.S.; Sardi, S.I.; Dias, B.R.S.; Menezes, J.P.B.; Rocha, V.P.C.; et al. Betulinic Acid Exerts Cytoprotective Activity on Zika Virus Infected Neural Progenitor Cells. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 558324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prados, M.E.; Correa-Sáez, A.; UncitBroceta, J.D.; Garrido-Rodríguez, M.; Jimenez-Jimenez, C.; Mazzone, M.; Minassi, A.; Appendino, G.; Calzado, M.A.; Muñoz, E. Betulinic Acid Hydroxamate is Neuroprotective and Induces Protein Phosphatase 2A-Dependent HIF-1α Stabilization and Post-transcriptional Dephosphorylation of Prolyl Hydrolase 2. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.H.K.; Youn, C.T.; Ho, M.V.; Karwe, W.S.; Jeong, W.-S.; Jun, M. p-Coumaric acid and ursolic acid from Corni fructus attenuated β-amyloid(25–35)-induced toxicity through regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in PC12 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4911–4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-Y.; Jeong, W.-S.; Jun, M. Protective Effects of the Key Compounds Isolated from Corni fructus against β-Amyloid-Induced Neurotoxicity in PC12 Cells. Molecules 2012, 17, 10831–10845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-W.; Tsai, R.-T.; Liu, S.-P.; Chen, C.-S.; Tsai, M.-C.; Chien, S.-H.; Hung, H.-S.; Lin, S.-Z.; Shyu, W.-C.; Fu, R.-H. Neuroprotective Effects of Betulin in Pharmacological and Transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell Transplant. 2018, 26, 1903–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A.S.; Görücü Yílmaz, Ş. Ferroptotic Potency of ISM1 Expression in the Drug-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease-Like Phenotype Under the Influence of Betulin. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 96, 1565–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Long, H. Protective effect of betulin on cognitive decline in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats. Neurotoxicology 2016, 57, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navabi, S.P.; Sarkaki, A.; Mansouri, E.; Badavi, M.; Ghadiri, A.; Farbood, Y. The effects of betulinic acid on neurobe-havioral activity, electrophysiology and histological changes in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2018, 337, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Peng, B.; Chen, Z.; Yu, J.; Deng, G.; Bao, Y.; MA, C.; Du, F.; Sheu, W.; Kimberly, W.; et al. Brain targeting, acid-responsive antioxidant nanoparticles for stroke treatment and drug delivery. Bioact. Mater. 2022, 16, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, S.; Zhu, H.; He, P.; Teng, J. Betulinic acid protects against cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury by activating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 84, 1533–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.K.; Nanda, A.; Gautam, A.S.; Singh, R.K. Betulinic acid protects against lipopolysaccharide and ferrous sul-fate-induced oxidative stress, ferroptosis, apoptosis, and neuroinflammation signaling relevant to Parkinson’s Disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 233, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaundal, M.; Zameer, S.; Najmi, A.K.; Parvez, S.; Akhtar, M. Betulinic acid, a natural PDE inhibitor restores hippocampal cAMP/cGMP and BDNF, improve cerebral blood flow and recover memory deficits in permanent BCCAO induced vascular dementia in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 832, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Gao, L.; Tan, Y.; Cai, J.; Ye, Z.; Chen, A.T.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Tong, S.; et al. Betulinic acid self-assembled nanoparticles for effective treatment of glioblastoma. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wang, H.; Zhu, L.; Wei, W. Ursolic Acid Ameliorates Early Brain Injury After Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury in Mice by Activating the Nrf2 Pathway. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Su, J.; Guo, B.; Zhu, T.; Wang, K.; Li, X. Ursolic acid alleviates early brain injury after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage by suppressing TLR4-mediated inflammatory pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 23, 585–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Su, J.; Wang, K.; Zhu, T.; Li, X. Ursolic acid reduces oxidative stress to alleviate early brain injury following experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 579, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahu, S.; Li, R.; Kadeyala, P.K.; Liu, S.; Schachner, M. The human natural killer-1 (HNK-1) glycan mimetic ursolic acid promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury in mouse. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 55, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Cui, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Ji, H.; Du, Y. Ursolic acid promotes the neuroprotection by activating Nrf2 pathway after cerebral ischemia in mice. Brain Res. 2013, 1497, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshattiwara, V.; Mukea, S.; Kaikinia, A.; Baglea, S.; Dighe, V.; Sathaye, S. Mechanistic evaluation of ursolic acid against rotenone induced Parkinson’s disease—Emphasizing the role of mitochondrial biogenesis. Brain Res. Bull. 2020, 160, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, S.N.; Zahra, W.; Singh, S.S.; Birla, H.; Keswani, C.; Dilnashin, H.; Rathore, A.S.; Singh, R.; Singh, R.K.; Singh, S.P. Antiinflammatory activity of ursolic acid in MPTP-induced parkinsonian mouse model. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 36, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name (TTs Group) | Main Plant Resources | Biological Activities | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

Oleanolic acid (oleanane group) FDB013034 | Oleaceae family (mainly olive) Cranberry, cloves Thyme, sage | Anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, hepatoprotective Anti-diabetic, anti-hypertensive Anti-microbial, anti-parasitic | [9,18,19,20] |

Maslinic acid (oleanane group) FDB013041 | Virgin olive oil Hawthorn, pomegranate Eggplant, spinach, mustard | Anti-viral, Anti-fungal, Anti-bacterial Antioxidant Anti-diabetic, Anti-inflammatory Cardio protective, Neuroprotection | [9,18,19,21,22,23] |

Asiatic acid (ursane group) FDB014909 | Edible and medicinal plants, e.g., centella asiatica, Guava/pomegranate | Stimulates collagen production Wound healing, anti-diabetic, Neuroprotective, cardioprotective, anti-microbial, anti-tumor | [9,18,19,24] |

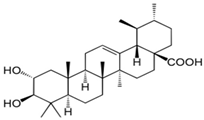

| Corosolic acid (ursane group) FDB013735  | Banaba (Lagerstroemia speciosa) from tropical areas | Reduction in the gluconeogenesis, impairment of starch and sucrose hydrolysis, and enhancement of the cellular uptake of glucose | [9,10,19,25] |

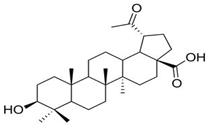

| Platanic acid (nor lupane) No FDB-ID  | Low content in sycamore trees (Platanus sp.), Melaleuca leucadendra Obtained by partial synthesis from B or BA | Used as a scaffold for the synthesis of cytotoxic derivatives (amines, amides, and oximes) and their screening for cytotoxicity | [9,26] |

| Molecules Studied | Mechanisms and Effects | References |

|---|---|---|

| Betulin and derivatives | Selective inhibition of TNF, MMPs, iNOS expression, NO inhibition, and suppression of the expression of interleukins | [62] |

| Betulin | Reduced inflammation in mouse chondrocytes, amelioration of osteoarthritis via AKT/Nrf2/HO-1/NF-B axis | [63] |

| Betulin | Modulator of the Glucocorticoid Receptor | [64] |

| Betulin | Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines via STAT3 signaling in human cardiac cells | [65] |

| Betulin-NLC-hydrogel | Skin anti-psoriatic activity, enhanced skin hydration and lipid restoration, and reduction in cytokine levels | [66] |

| Betulinic acid | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-AChE activity of betulinic acid and 3β-acetoxybetulinic acid from Melaleuca bracteata | [67] |

| Lupane-TTs (Maytenus sp.) | Inhibition of NO and PGE2 | [68] |

| TTs | Cell Line/Animal Model | Concentration | Mechanism of Action | Biochemical Markers | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro studies | |||||

| Betulin | Neuronal hippocampal HT22 cell line | 10 µM | antioxidant activity reduced cellular damage protection from ER stress increase HO-1 expression | ↓ ROS ↓ Caspase12 genes ↑ HO-1 genes ↓ CHOP genes | [135] |

| microglial cell BV2—LPS induced neuroinflammation | 250 μg/mL | reduction in iNOS expression cytokines’ inhibition downregulated NFκB/p65 phosphorylation | ↓ NO production ↓ NfκB ↓ TNFα, IL6, IL1β | [136] | |

| differentiated SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells | 1–30 µM | protective effects against H2O2-induced oxidative stress Inhibition of apoptosis | ↓ ROS ↓ apoptotic cells vs. H2O2-treated cells | [137] | |

| 9 human neuroblastoma cell lines | 0–20 µg/mL, 6 days | morphological changes in 3 days. Reduced axonic-like extensions, non-adherent, and condensed cells typical of apoptosis DNA fragmentation (ladder formation in the 100–1200 bp region in neuroblastoma cells | ↑ apoptosis ↑ DNA fragments | [138] | |

| neuroectodermal tumor cells (neuroblastoma, medulloblastoma, glioblastoma and Ewing sarcoma cells) | direct effect on mitochondria, independent of p53 protein accumulation death-inducing ligand/receptor systems such as CD95 mitochondrial perturbations antitumor activity on neuroblastoma cells resistant to CD95/on doxorubicin-triggered apoptosis | ↑ apoptosis ↑ cytochrome c ↑ caspases ↑ Bcl-2 ↓ proliferation | [139] | ||

| brain tissue homogenates treated ex vivo with 0.1 mM FeSO4 for 30 min at 37 °C | 10µM | pro-apoptotic effect reversal of suppressed levels of GSH, SOD, CAT, and ectonucleotidase activities. induction of oxidative neurotoxicity Bypass resistance to apoptosis-inducing agents (CD95 or doxorubicin). | ↓ MDA ↓ NO ↓ ATPase ↓ AcChol ↓ α-chymotrypsin ↓ seleno- metabolism ↓ PI-signaling | [140] | |

| Betulinic acid | BV2 microglial cells | 10 µM | suppress M1 phenotype expression promote microglia M2 polarization anti-neuroinflammatory effects via CaMKKβ-dependent AMPK activation. | ↓ TNFα release ↑ IL10 release ↓ IL6 ↓ IL1β ↓ mRNA ↓ iNOS ↓ CD16 ↓ CD68 | [141] |

| ZIKV infected Neural Cells | 50 µM | antiviral activity via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | ↑ PI3K/Akt signaling pathway | [142] | |

| HD models in vitro: HEK-293T and NIH 3T3 cell lines In vivo: C57BL/6 male mice | BAH 5–20 µM In vivo (30 mg/kg) | inhibition of HIF and PHD2 HIF activation Action via protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A). Reduced striatal neurodegeneration | ↓ PHD2 phosphorylation ↑ HIF-1α activation stability | [143] | |

| Ursolic acid | PC12 nervous cells with Aβ25–35 induced toxicity | 20 µM | anti-inflammatory effect nuclear translocation of the p65 subunit of NFκB inhibition of proteins’ phosphorylation | ↓ iNOS ↓ COX2 ↓ IκBα ↓ ERK1/2 phosphorylation ↓ p38 ↓ JNK phosphorylation | [144] |

| PC12 cell line | 50 and 125 µM | antioxidant activity attenuate DNA fragmentation attenuate Aβinduced apoptosis | ↓ ROS ↓ caspase3 | [145] | |

| In vivo studies | |||||

| Betulin | transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans (roundworm nematode) as models of PD | 0.5 mM | Anti-PD activity: protection from 6-hydroxydopamine degeneration decreased inflammation increased life span downregulation of the apoptosis gene pathway egl-1 enhancement of proteasome activity by promoting Rpn1 expression | ↓ αsyn nuclei ↓ Monocyte chemotactic protein1 ↓ PGsynthase2 ↓ iNOS ↓ egl-1 genes | [146] |

| AD model Wistar albino male rats with okadaic acid | 20 mg/kg/day, i.p). | Regulation of adipokine gene expression and iron accumulation, reduced hippocampal oxidative metabolism | ↑ Antioxidant ↓ iron accumulation | [147] | |

| Rats with Diabetus induced with streptozotocin (30 mg/kg, ip). | 20 mg/kg, 40 mg/kg | restored SOD activity upregulation of Nrf2, HO1 expression protective effect on cognitive decline through the HO1/Nrf2/NFκB pathway improved glucose intolerance and learning performance | ↓ cytokines ↓ MDA ↓ cytokines ↓ IκB, NFκB phosphorylations | [148] | |

| Betulinic acid | Wistar rats with AD induced with Aβ (0.1 μM/5 μlPBS/rat | 0.2 and 0.4 μM/10 μL DMSO/rat (i.h.) | restored memory and anxiety, anxiolytic and antidepressant effects prevention of AD-induced neurobehavior prevention of LTP deficits at a molar ratio of 1:4 (Aβ:BA). | ↑ proteasome ↑ hippocampal potentiation ↑ LTP parameters | [149] |

| Induced stroke Wistar rats model (Middle cerebral artery occlusion) i.v.adm with AMD3100, for delivery of NA1 | 1 mg BAM | targeted BA release in acidic ischemic tissue improved recovery from stroke efficacy enhanced by encapsulated NA1 increased survival | Enhance the efficacy of the neuroprotective peptide NA1 | [150] | |

| Wistar Rats with oxygen and glucose deprivation to induce neuronal injury | Pretreatment with BA | Attenuation of hippocampal neuronal injury, up-regulation of Bcl-2, downregulation of Bax, inactivation of caspase-3 | ↓ MDA ↓ ROS ↓ Bax ↑ Bcl-2 ↓ Caspase-3 | [151] | |

| Wistar rats as a PD model induced with LPS and FeSO4. | BA 10 mg/kg | reversed behavioral deficits mitigated immunohistopathological and biochemical abnormalities reduce ferroptosis, and apoptosis biomarkers implicated in neurodegeneration | ↑ TyrOHase ↓ α-syn ↓ SOD | [152] | |

| Wistar rats with vascular dementia induced by carotid artery occlusion | Oral, 10 and 15 mg/kg/day for 1 week | neuroprotective effect in a dose-dependent manner re-established cerebral blood flow, restored behavioral parameters fewer pathological abnormalities reduced inflammatory parameters. decrease in microgliosis | ↑ cAMP, cGMP ↓ inflamation ↓ oxidative stress | [153] | |

| Glioblastoma cells and intracranial xenograft glioblastoma mouse models. | Nanoemulsion of BA in DMSO, Ethyl acetate, and polyvinyl acid 0–15 µg/mL | suppression of glioma cell proliferation, arrest the cell cycle in the G0/G1 phase. Downregulated Akt/NFκB-p65 signaling pathway cross the BBB and increase the survival time, anti-tumor effect | ↑ apoptosis ↑ CB1/CB2 receptors ↓ Akt/NfκB-p65. | [154] | |

| Ursolic acid | Mice model of Traumatic Brain Injury | 100, 150 mg/kg | antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects reduce brain oedema reduced neurological insufficiencies | ↑ Nrf2 ↑ pAKT ↓ MDA ↑ SOD ↑ GPx | [155] |

| Rats model of subarachnoid hemorrhage brain injury | 50 mg/kg | antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects: inhibition of apoptosis improved neuronal survival inhibition of caspases 3 and 9 | ↓ ICAM ↓ NFκB ↓ IL1β, IL6 ↓ TNF α ↓ TLR4 ↓ iNOS ↓ MMP9 ↓ MDA, SOD, CAT ↑ GSH/GSSG ratio | [156,157] | |

| Mice model of spinal cord injury | 25, 50 mg/kg | neuro regeneration recover motor functions recover axonal regrowth decrease astrogliosis | ↓ IL6 ↓ TNF α | [158] | |

| Nrf2 and wildtype mice | 130 mg/kg | improved neurological deficit in acute stroke reduce infarct volume prevent ischemic damage antioxidant and anti-inflammatory responses | ↑ Nrf2 mRNA ↑ HO1 mRNA ↓ TLR4 ↓ NFkB | [159] | |

| Rat PD model established by rotenone infusions | 30-day Adm of 5, 10 mg/kg | improved mitochondrial enzymatic activity and MtCO1 gene expression | ↑ CAT, ↑ SOD, ↑ GSH, ↓ MDA ↓ TNF-α, ↑ TyrOHase positive neurons | [160] | |

| PD Wistar rat model | UA-THP i.v. 25 mg/kg for 21 d | Activation of PP2A/PHD2/HIF pathway Reduction in oxidative stress Stimulation of TyrOHase-positive neurons Prevent neuronal loss Decrease in reactive astrogliosis and microglial activation | ↓ glial fibrillary protein ↑ CAT,↑ GSH, ↓ MDA ↓ NF-κB, ↓ TNF-α, ↓ IFN- ↓ IL-12, ↑ IL-4, -10 | [161] | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Socaciu, M.A.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Rugina, D.; Socaciu, C.; Moldovan, R.; Clichici, S. Mechanistic Insights into the Metabolic Pathways and Neuroprotective Potential of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids: In-Depth Analysis of Betulin, Betulinic, and Ursolic Acids. Biomolecules 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010025

Socaciu MA, Diaconeasa Z, Rugina D, Socaciu C, Moldovan R, Clichici S. Mechanistic Insights into the Metabolic Pathways and Neuroprotective Potential of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids: In-Depth Analysis of Betulin, Betulinic, and Ursolic Acids. Biomolecules. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleSocaciu, Mihai Adrian, Zorita Diaconeasa, Dumitrita Rugina, Carmen Socaciu, Remus Moldovan, and Simona Clichici. 2026. "Mechanistic Insights into the Metabolic Pathways and Neuroprotective Potential of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids: In-Depth Analysis of Betulin, Betulinic, and Ursolic Acids" Biomolecules 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010025

APA StyleSocaciu, M. A., Diaconeasa, Z., Rugina, D., Socaciu, C., Moldovan, R., & Clichici, S. (2026). Mechanistic Insights into the Metabolic Pathways and Neuroprotective Potential of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids: In-Depth Analysis of Betulin, Betulinic, and Ursolic Acids. Biomolecules, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom16010025