HCMV as an Oncomodulatory Virus in Ovarian Cancer: Implications of Viral Strain Heterogeneity, Immunomodulation, and Inflammation on the Tumour Microenvironment and Ovarian Cancer Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Ovarian Cancer (OC)

1.2. Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV)

1.3. Prevalence of HCMV in Ovarian Cancer

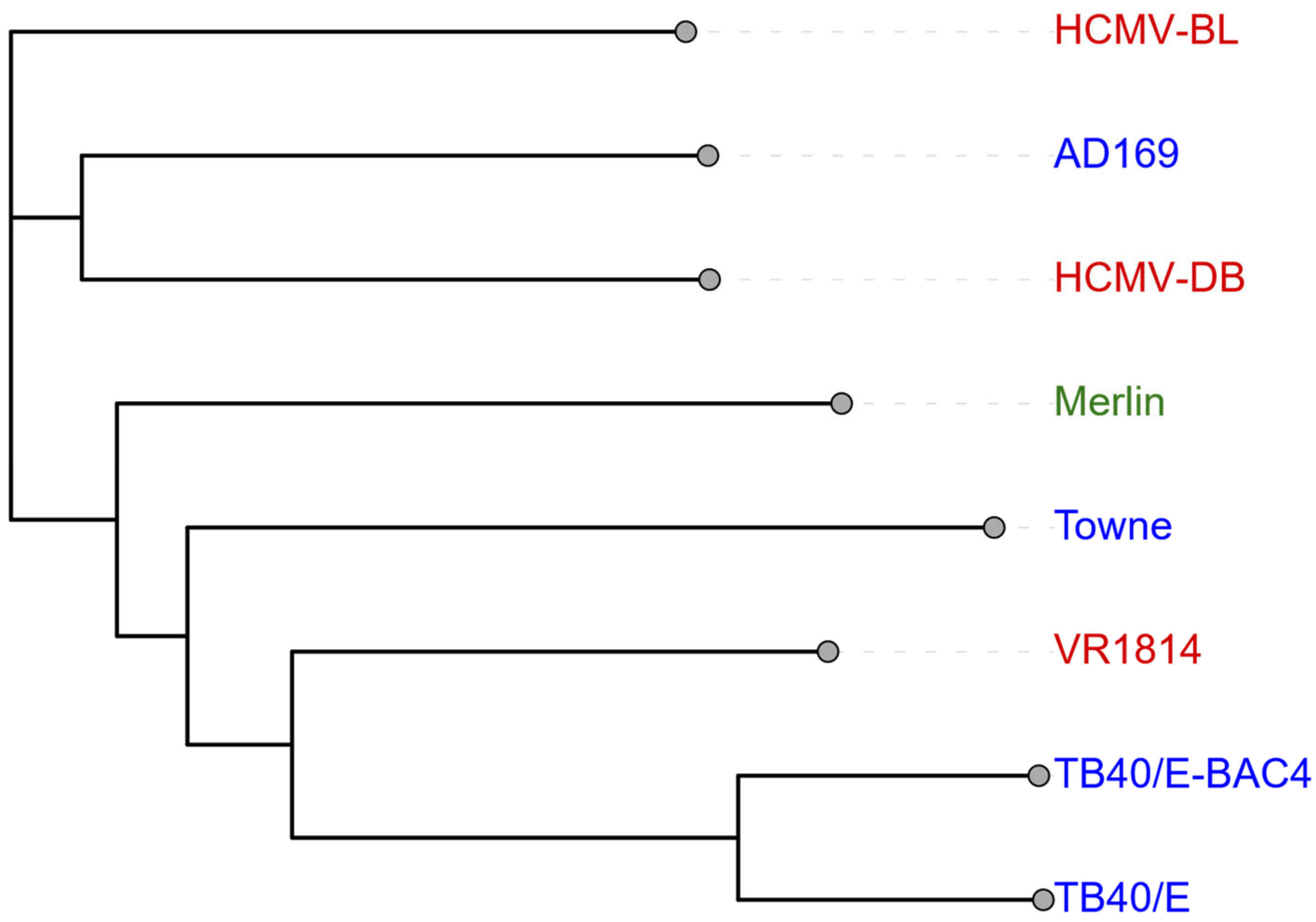

2. HCMV Viral Strain Heterogeneity and Oncogenic Potential in Ovarian Cancer

Research Limitations Due to Strain Variability

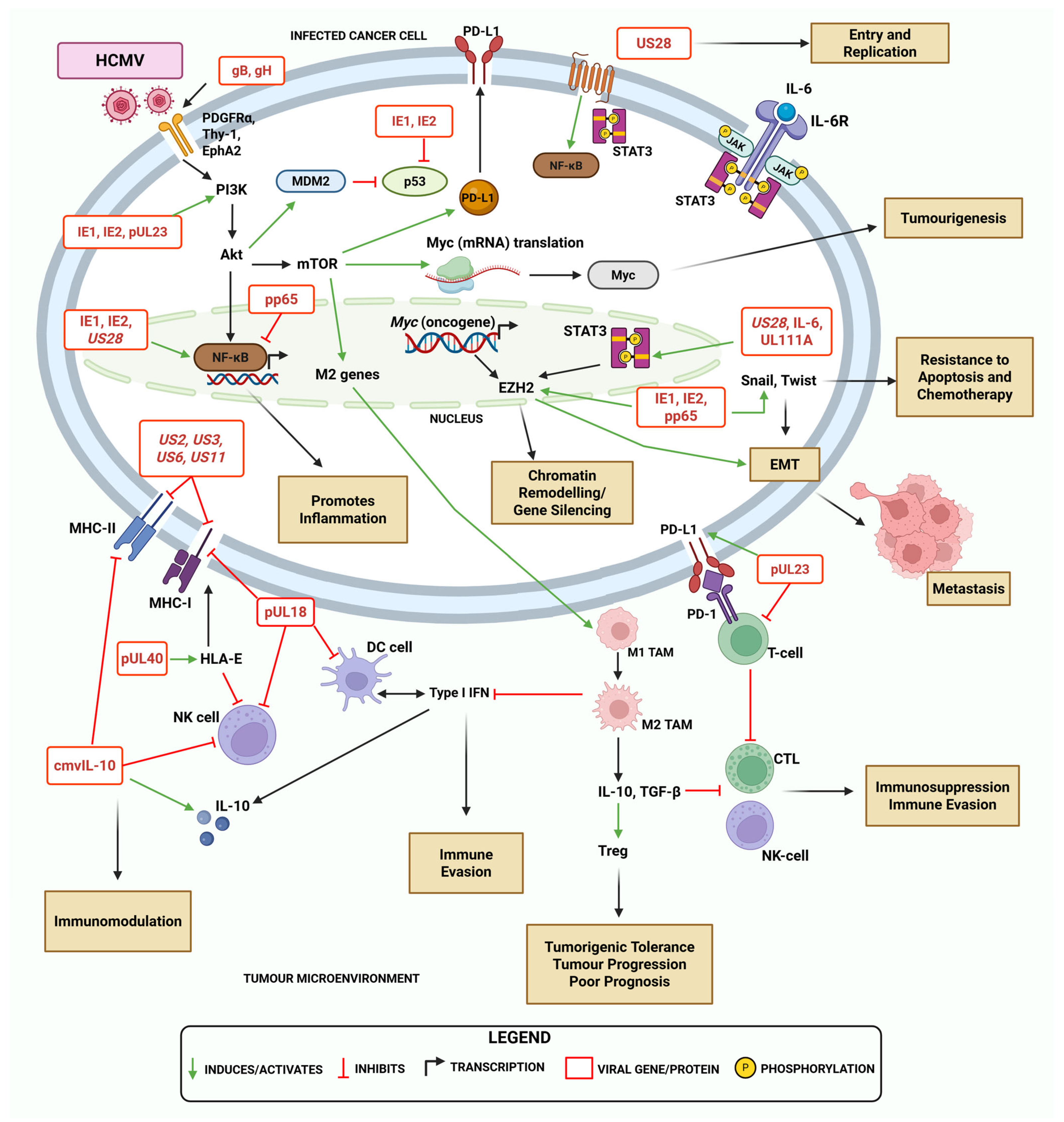

3. Overview of HCMV Genes and Proteins in Immunomodulation and Oncogenesis

| Gene | Protein | Function/Role | Stage of Infection |

|---|---|---|---|

| UL123, UL122 | IE1, IE2 | Transcription factors—activate Myc/EZH2, drive inflammation, cell proliferation, genomic instability, apoptosis, and immune evasion [7,12,16,35,56] | Immediate Early |

| UL83 | pp65 | Tegument protein—sequesters IE1, promotes immune evasion, inflammation, proliferation, and genomic instability [6,51,56] | Structural |

| US28 | US28 | Viral GPCR—activates NF-κB, binds chemokines, enhances immune evasion, tumour growth, cell survival [32,55,59,60] | Early/late * |

| UL54 | pUL54 | Viral DNA polymerase—essential for viral replication [12] | Early |

| UL111A | cmvIL-10 | IL-10 mimic—suppresses MHC-II, T/NK cell function, enhances immunosuppression, migration, and metastasis [7,12,61,62] | Late * |

| UL97 | pUL97 | Viral kinase—promotes reactivation, progeny release, and immune evasion [56] | Late |

| UL55 | gB, gH | Envelope glycoproteins—facilitate viral adhesion, entry, and fusion [7] | Structural |

| UL40 | pUL40 | MHC-I signal mimic—stabilises MHC (HLA-E) to inhibit NK cells via CD94/NKG2A receptor, supports tumour survival and immunosuppressive TME [1,7,63] | Late * |

| UL18 | pUL18 | MHC-I homologue—binds LIR-1 to inhibit NK cells, downregulates MHC-II, impairs dendritic cell development, and suppresses T-cell responses [1,7,63,64] | Late |

| UL138 | pUL138 | Latency-associated protein—establishes and maintains latency in vitro, supporting infected cell survival, and suppressing viral replication [61,62] | Latency |

| LUNA | LUNA | Latency Unique Natural Antigen (LUNA)—regulates viral reactivation, and latency-associated gene transcription [62,65,66] | Latency |

4. HCMV-Mediated Mechanisms of Immune Modulation and Evasion in Ovarian Cancer

4.1. Viral Induction of Cancer Stemness and Stem Cell Expansion

4.1.1. HCMV Infection on Thy-1 and PDGFRα in Cancer

4.1.2. Potential Dual Role of PDGFRα on Promoting Ovarian Tumour Aggressiveness in HCMV Infection

4.1.3. HCMV May Induce Tumorigenic Properties and Stemness Pathways in OC

4.2. Impacts of HCMV on Antigen Presentation and Immune Checkpoint Modulation

4.2.1. Upregulation of PD-L1 by HCMV in Cancer

4.2.2. HCMV-Induced Reprogramming of Macrophages Towards a Pro-Tumour Phenotype in the OC TME

4.2.3. HCMV Exploits the Human Leukocyte Antigen-E (HLA-E)/NKG2A Immune Checkpoint Axis to Evade T-Cell-Mediated Killing

4.2.4. Interferon-γ Signalling as a Key Feedback Regulator in HCMV Infection and Cancer Progression

4.2.5. The Duality of HCMV’s Potential Protective and Immunosuppressive Roles in Immune Checkpoint Blockade Therapy

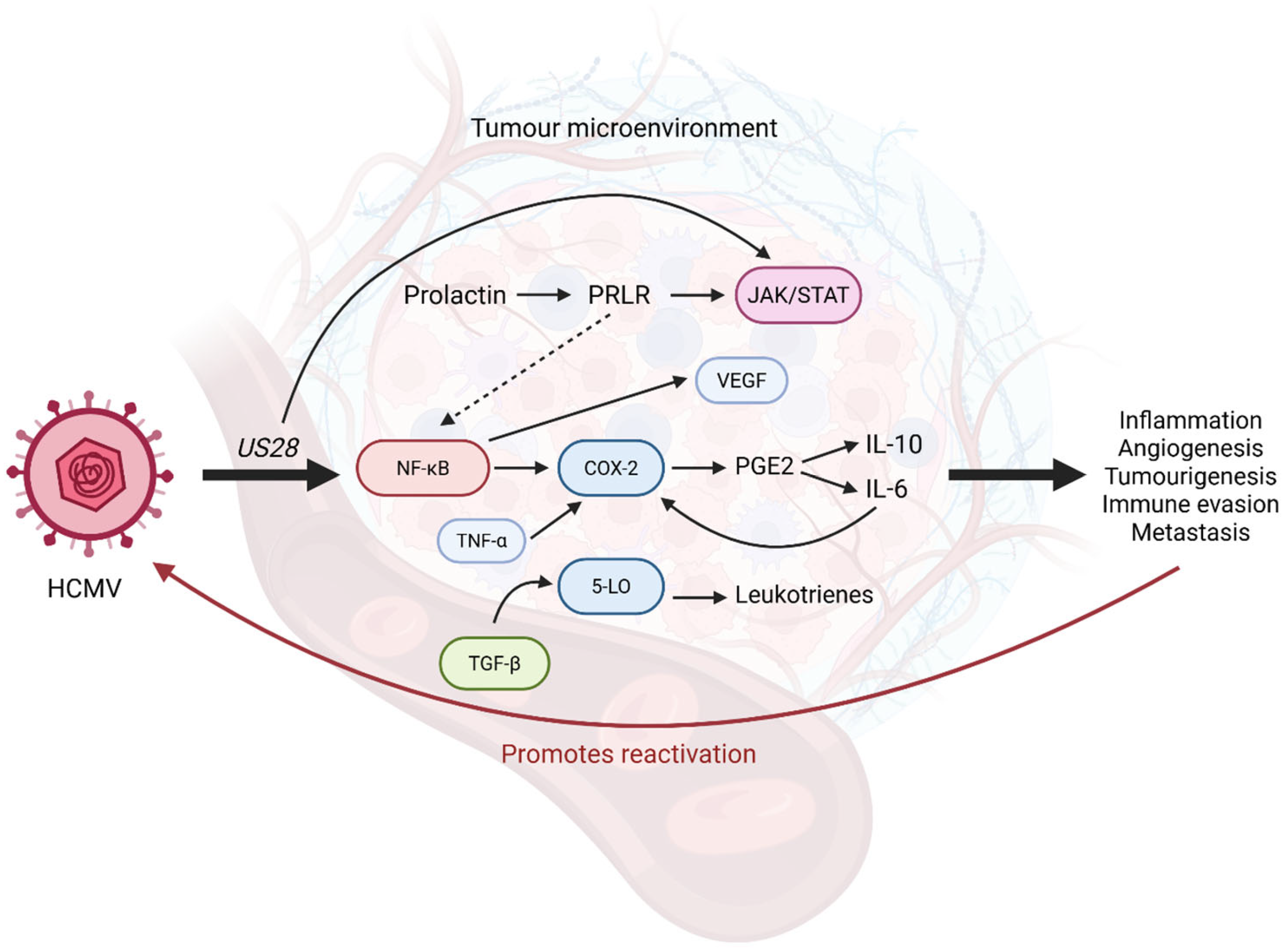

4.3. Viral Promotion of Inflammation and Its Effects in the TME

4.3.1. Viral Activation of NF-κB Drives Production of Inflammatory Cytokines

4.3.2. Inflammatory Signalling Pathways in Ovarian Cancer and Their Modulation by HCMV

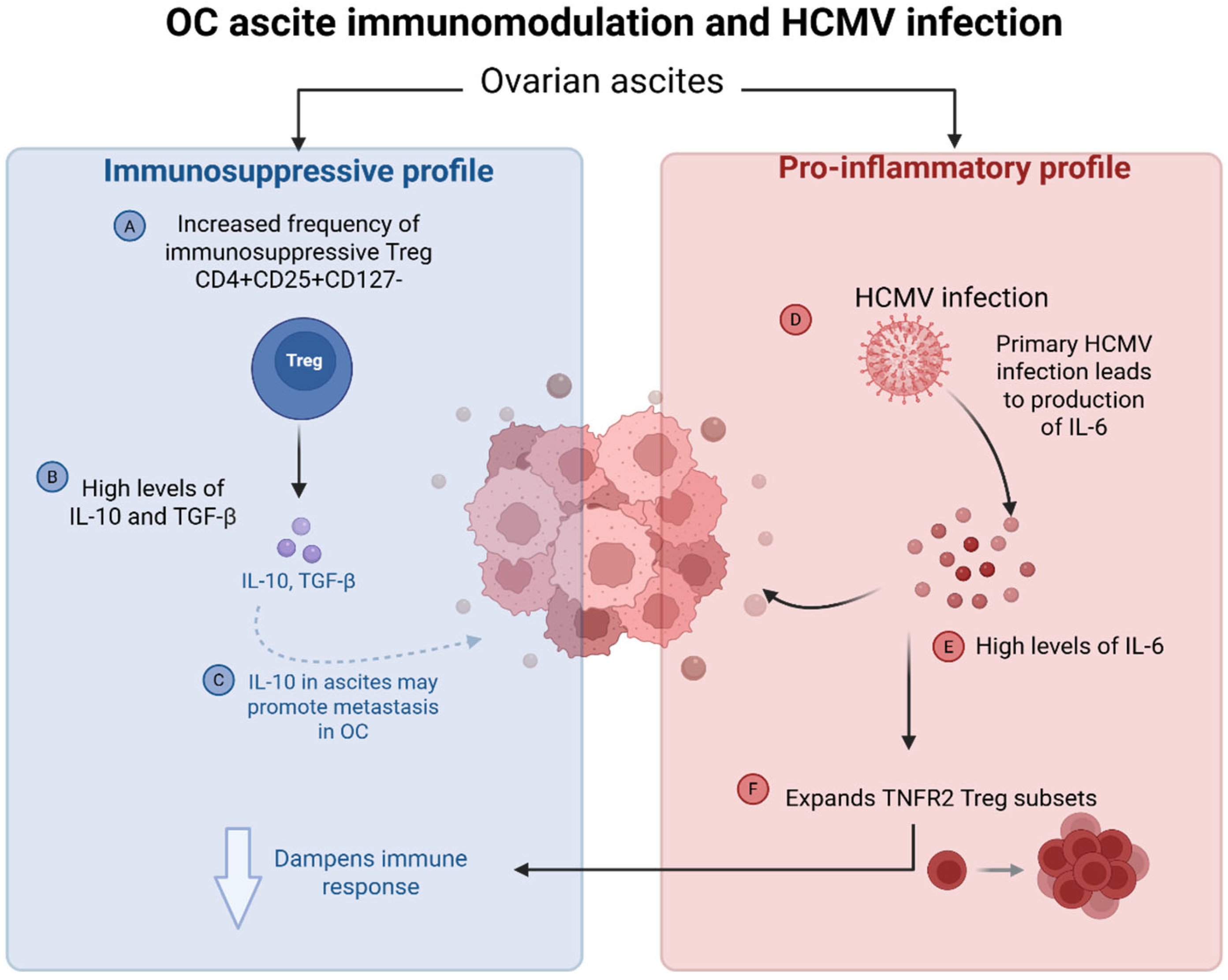

4.3.3. HCMV-Induced Cytokine Dysregulation in Ovarian Cancer Ascites and Impact on the Tumour Microenvironment

5. Persistent HCMV Infection on Immunosenescence in OC Patients

6. Therapeutic Implications

Limitations and Clinical Considerations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 5-LO | 5-lipoxygenase |

| ACT | Adoptive cell therapy |

| Akt | Protein kinase B |

| APEC | Antibody-peptide epitope conjugates |

| BC | Breast cancer |

| BOT | Borderline ovarian tumour |

| CAR | Chimeric antigen receptor |

| CD90 | Cluster of differentiation 90 (also known as Thy-1) |

| CmvIL-10 | Cytomegalovirus-encoded human interleukin-10 |

| COX-2 | Cycloxygenase-2 |

| CSC | Cancer stem cells |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| DFS | Disease-free survival |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| EMT | Epithelial-to-mesenchymal |

| EphA2 | Ephrin receptor A2 |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 |

| EZH2 | Enhancer of zeste homologue 2 |

| gB | Envelope glycoprotein-B |

| GBM | Glioblastoma multiforme |

| gH | Envelope glycoprotein-H |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| HCMV | Human cytomegalovirus |

| HGSOC | High-grade serous ovarian cancer |

| HLA-E | Human leukocyte antigen-E |

| HPC | Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells |

| HPV | Human papillomavirus |

| i.t | Intra-tumoural |

| ICB | Immune checkpoint blockade |

| IE1/2 | Immediate early protein 1/2 |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IRP | Immune risk profile |

| JAK | Janus-associated kinases |

| MDSC | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MET | Mesenchymal-to-epithelial |

| MHC-I | Major histocompatibility complex class I |

| MHC-II | Major histocompatibility complex class II |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor-κB |

| NK | Natural killer cell |

| OC | Ovarian cancer |

| OCSC | Ovarian cancer stem cells |

| OS | Survival outcomes |

| PDGFRα | Platelet-derived growth factor receptor α |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein-1 |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death ligand-1 |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| PGCC | Polyploid giant cancer cells |

| pp65 | 65 kDa tegument protein |

| pRB | Phosphorylated retinoblastoma protein |

| PRL | Prolactin |

| PRLR | Prolactin receptor |

| SC | Stem cell |

| SLC | Stem-like cells |

| STAT3 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 |

| TAM | Tumour-associated macrophages |

| TAP | Peptide transporter associated with antigen processing |

| TCR | T-cell receptor |

| TEDbodies | T-cell epitope delivering antibodies |

| TEMRA | Terminally differentiated effector memory T-cells re-expressing CD45RA |

| TGF-β | Transforming growth factor-beta |

| Thy-1 | Thy-1 cell surface antigen (also known as CD90) |

| TIL | Tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes |

| TLR2 | Toll-like receptors 2 |

| TME | Tumour microenvironment |

| TNF-α | Tumour necrosis factor-alpha |

| Treg | Regulatory T-cell |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Cox, M.; Kartikasari, A.E.R.; Gorry, P.R.; Flanagan, K.L.; Plebanski, M. Potential Impact of Human Cytomegalovirus Infection on Immunity to Ovarian Tumours and Cancer Progression. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momenimovahed, Z.; Tiznobaik, A.; Taheri, S.; Salehiniya, H. Ovarian cancer in the world: Epidemiology and risk factors. Int. J. Womens Health 2019, 11, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer Council Victoria. Ovarian Cancer Statistics. Available online: https://www.cancervic.org.au/cancer-information/statistics/ovarian-cancer.html (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Grabarek, B.O.; Ossowski, P.; Czarniecka, J.; Ożóg, M.; Prucnal, J.; Dziuba, I.; Ostenda, A.; Dziobek, K.; Boroń, D.; Peszek, W.; et al. Detection and Genotyping of Human Papillomavirus (HPV16/18), Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), and Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV) in Endometrial Endometroid and Ovarian Cancers. Pathogens 2023, 12, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, H.; Akbarabadi, P.; Dadfar, A.; Tareh, M.R.; Soltani, B. A comprehensive overview of ovarian cancer stem cells: Correlation with high recurrence rate, underlying mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rådestad, A.F.; Estekizadeh, A.; Cui, H.L.; Kostopoulou, O.N.; Davoudi, B.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Carlson, J.; Rahbar, A.; Söderberg-Naucler, C. Impact of Human Cytomegalovirus Infection and its Immune Response on Survival of Patients with Ovarian Cancer. Transl. Oncol. 2018, 11, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Baba, R.; Herbein, G. Immune landscape of CMV infection in cancer patients: From “canonical” diseases toward virus-elicited oncomodulation. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 730765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, H.; Peper, J.K.; Bösmüller, H.-C.; Röhle, K.; Backert, L.; Bilich, T.; Ney, B.; Löffler, M.W.; Kowalewski, D.J.; Trautwein, N.; et al. The immunopeptidomic landscape of ovarian carcinomas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E9942–E9951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guyon, J.; Haidar Ahmad, S.; El Baba, R.; Le Quang, M.; Bikfalvi, A.; Daubon, T.; Herbein, G. Generation of glioblastoma in mice engrafted with human cytomegalovirus-infected astrocytes. Cancer Gene Ther. 2024, 31, 1070–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, A.; Orrego, A.; Peredo, I.; Dzabic, M.; Wolmer-Solberg, N.; Strååt, K.; Stragliotto, G.; Söderberg-Nauclér, C. Human cytomegalovirus infection levels in glioblastoma multiforme are of prognostic value for survival. J. Clin. Virol. 2013, 57, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baba, R.; Pasquereau, S.; Haidar Ahmad, S.; Monnien, F.; Abad, M.; Bibeau, F.; Herbein, G. EZH2-Myc driven glioblastoma elicited by cytomegalovirus infection of human astrocytes. Oncogene 2023, 42, 2031–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branch, K.M.; Garcia, E.C.; Chen, Y.M.; McGregor, M.; Min, M.; Prosser, R.; Whitney, N.; Spencer, J.V. Productive Infection of Human Breast Cancer Cell Lines with Human Cytomegalovirus (HCMV). Pathogens 2021, 10, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baba, R.; Pasquereau, S.; Haidar Ahmad, S.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Herbein, G. Oncogenic and Stemness Signatures of the High-Risk HCMV Strains in Breast Cancer Progression. Cancers 2022, 14, 4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taher, C.; Frisk, G.; Fuentes, S.; Religa, P.; Costa, H.; Assinger, A.; Vetvik, K.K.; Bukholm, I.R.K.; Yaiw, K.-C.; Smedby, K.E.; et al. High Prevalence of Human Cytomegalovirus in Brain Metastases of Patients with Primary Breast and Colorectal Cancers. Transl. Oncol. 2014, 7, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, H.; Touma, J.; Davoudi, B.; Benard, M.; Sauer, T.; Geisler, J.; Vetvik, K.; Rahbar, A.; Söderberg-Naucler, C. Human cytomegalovirus infection is correlated with enhanced cyclooxygenase-2 and 5-lipoxygenase protein expression in breast cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 2083–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.H.; Pasquereau, S.; El Baba, R.; Nehme, Z.; Lewandowski, C.; Herbein, G. Distinct Oncogenic Transcriptomes in Human Mammary Epithelial Cells Infected With Cytomegalovirus. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 772160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouezzedine, F.; El Baba, R.; Haidar Ahmad, S.; Herbein, G. Polyploid Giant Cancer Cells Generated from Human Cytomegalovirus-Infected Prostate Epithelial Cells. Cancers 2023, 15, 4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, W.H.; Chen, H.-P.; Huang, J.C.; Chan, Y.-J. Human cytomegalovirus infection enhances cell proliferation, migration and upregulation of EMT markers in colorectal cancer-derived stem cell-like cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2017, 51, 1415–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classon, J.; Stenudd, M.; Zamboni, M.; Alkass, K.; Eriksson, C.-J.; Pedersen, L.; Schörling, A.; Thoss, A.; Bergh, A.; Wikström, P.; et al. Cytomegalovirus infection is common in prostate cancer and antiviral therapies inhibit progression in disease models. Mol. Oncol. 2025, 19, 3035–3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantalone, M.R.; Martin Almazan, N.; Lattanzio, R.; Taher, C.; De Fabritiis, S.; Valentinuzzi, S.; Bishehsari, F.; Mahdavinia, M.; Verginelli, F.; Rahbar, A.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus infection enhances 5-lipoxygenase and cycloxygenase-2 expression in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2023, 63, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baba, R.; Haidar Ahmad, S.; Monnien, F.; Mansar, R.; Bibeau, F.; Herbein, G. Polyploidy, EZH2 upregulation, and transformation in cytomegalovirus-infected human ovarian epithelial cells. Oncogene 2023, 42, 3047–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baba, R.; Haidar Ahmad, S.; Vanhulle, C.; Vreux, L.; Plant, E.; Van Lint, C.; Herbein, G. Formation of Polyploid Giant Cancer Cells and the Transformative Role of Human Cytomegalovirus IE1 Protein. Cancer Lett. 2025, 630, 217824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouezzedine, F.; Baba, R.E.; Morot-Bizot, S.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Herbein, G. Cytomegalovirus at the crossroads of immunosenescence and oncogenesis. Explor. Immunol. 2023, 3, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbs, C. Cytomegalovirus is a tumor-associated virus: Armed and dangerous. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 39, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, J.W.; Rådestad, A.F.; Söderberg-Naucler, C.; Rahbar, A. Human cytomegalovirus in high grade serous ovarian cancer possible implications for patients survival. Medicine 2018, 97, e9685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanmughapriya, S.; Senthilkumar, G.; Vinodhini, K.; Das, B.; Vasanthi, N.; Natarajaseenivasan, K. Viral and bacterial aetiologies of epithelial ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 31, 2311–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Chen, A.; Zhao, F.; Ji, X.; Li, C.; Wang, G. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer and its impacts on survival. Infect. Agents Cancer 2020, 15, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, A.; Pantalone, M.R.; Religa, P.; Rådestad, A.F.; Söderberg-Naucler, C. Evidence of human cytomegalovirus infection and expression of 5-lipoxygenase in borderline ovarian tumors. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 4023–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowska, E.; Jabłońska, A.; Studzińska, M.; Wilczyński, M.; Wilczyński, J.R. Detection and genotyping of CMV and HPV in tumors and fallopian tubes from epithelial ovarian cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.H.; El Baba, R.; Herbein, G. Polyploid giant cancer cells, cytokines and cytomegalovirus in breast cancer progression. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Baba, R.; Herbein, G. EZH2-Myc Hallmark in Oncovirus/Cytomegalovirus Infections and Cytomegalovirus’ Resemblance to Oncoviruses. Cells 2024, 13, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehme, Z.; Pasquereau, S.; Haidar Ahmad, S.; El Baba, R.; Herbein, G. Polyploid giant cancer cells, EZH2 and Myc upregulation in mammary epithelial cells infected with high-risk human cytomegalovirus. EBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, C.; Gatherer, D.; Hilfrich, B.; Baluchova, K.; Dargan, D.J.; Thomson, M.; Griffiths, P.D.; Wilkinson, G.W.; Schulz, T.F.; Davison, A.J. Sequences of complete human cytomegalovirus genomes from infected cell cultures and clinical specimens. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renzette, N.; Gibson, L.; Bhattacharjee, B.; Fisher, D.; Schleiss, M.R.; Jensen, J.D.; Kowalik, T.F. Rapid intrahost evolution of human cytomegalovirus is shaped by demography and positive selection. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patro, A.R.K. Subversion of Immune Response by Human Cytomegalovirus. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Hong, W.; Wei, X. The molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of EMT in tumor progression and metastasis. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberstein, A.; Shenk, T. Cellular responses to human cytomegalovirus infection: Induction of a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) phenotype. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E8244–E8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, G.W.; Davison, A.J.; Tomasec, P.; Fielding, C.A.; Aicheler, R.; Murrell, I.; Seirafian, S.; Wang, E.C.; Weekes, M.; Lehner, P.J.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus: Taking the strain. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2015, 204, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussawi, F.A.; Kumar, A.; Pasquereau, S.; Tripathy, M.K.; Karam, W.; Diab-Assaf, M.; Herbein, G. The transcriptome of human mammary epithelial cells infected with the HCMV-DB strain displays oncogenic traits. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galitska, G.; Coscia, A.; Forni, D.; Steinbrueck, L.; De Meo, S.; Biolatti, M.; De Andrea, M.; Cagliani, R.; Leone, A.; Bertino, E.; et al. Genetic Variability of Human Cytomegalovirus Clinical Isolates Correlates With Altered Expression of Natural Killer Cell-Activating Ligands and IFN-γ. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 532484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.M.; Kaneshima, H.; Mocarski, E.S. Dramatic Interstrain Differences in the Replication of Human Cytomegalovirus in SCID-hu Mice. J. Infect. Dis. 1995, 171, 1599–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; Yu, D.; Grimwood, J.; Schmutz, J.; Dickson, M.; Jarvis, M.A.; Hahn, G.; Nelson, J.A.; Myers, R.M.; Shenk, T.E. Coding potential of laboratory and clinical strains of human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 14976–14981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, C.J.; Ferreira Castro, F.L.; de Aguiar, R.B.; Menezes, I.G.; Santos, A.C.; Paulus, C.; Nevels, M.; Carlan da Silva, M.C. Impact of human cytomegalovirus on glioblastoma cell viability and chemotherapy treatment. J. Gen. Virol. 2018, 99, 1274–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchut-Maya, J.M.; Bartek, J.; Bartkova, J.; Galanos, P.; Pantalone, M.R.; Lee, M.; Cui, H.L.; Shilling, P.J.; Brøchner, C.B.; Broholm, H.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus hijacks host stress response fueling replication stress and genome instability. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 1639–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Hu, M.; Xing, F.; Wang, M.; Wang, B.; Qian, D. Human cytomegalovirus infection promotes the stemness of U251 glioma cells. J. Med. Virol. 2017, 89, 878–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Qaffas, A.; Camiolo, S.; Vo, M.; Aguiar, A.; Ourahmane, A.; Sorono, M.; Davison, A.J.; McVoy, M.A.; Hertel, L. Genome sequences of human cytomegalovirus strain TB40/E variants propagated in fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, Z.; Ross, S.A.; Patro, R.K.; Pati, S.K.; Kumbla, R.A.; Brice, S.; Boppana, S.B. Cytomegalovirus Strain Diversity in Seropositive Women. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 882–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touma, J.; Pantalone, M.R.; Rahbar, A.; Liu, Y.; Vetvik, K.; Sauer, T.; Söderberg-Naucler, C.; Geisler, J. Human Cytomegalovirus Protein Expression Is Correlated with Shorter Overall Survival in Breast Cancer Patients: A Cohort Study. Viruses 2023, 15, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-Munoz, N.; El Najjar, F.; Dutch, R.E. Chapter Three-Viral cell-to-cell spread: Conventional and non-conventional ways. In Advances in Virus Research; Kielian, M., Mettenleiter, T.C., Roossinck, M.J., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 108, pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodkin-Gal, D.; Hulot, S.L.; Korioth-Schmitz, B.; Gombos, R.B.; Zheng, Y.; Owuor, J.; Lifton, M.A.; Ayeni, C.; Najarian, R.M.; Yeh, W.W.; et al. Efficiency of cell-free and cell-associated virus in mucosal transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 13589–13597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderberg-Nauclér, C. New mechanistic insights of the pathogenicity of high-risk cytomegalovirus (CMV) strains derived from breast cancer: Hope for new cancer therapy options. eBioMedicine 2022, 81, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbein, G. The Human Cytomegalovirus, from Oncomodulation to Oncogenesis. Viruses 2018, 10, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; He, S.; Zhu, W.; Ru, P.; Ge, X.; Govindasamy, K. Human cytomegalovirus in cancer: The mechanism of HCMV-induced carcinogenesis and its therapeutic potential. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1202138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomtishen 3rd, J.P. Human cytomegalovirus tegument proteins (pp65, pp71, pp150, pp28). Virol. J. 2012, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishna, B.A.; Humby, M.S.; Miller, W.E.; O’Connor, C.M. Human cytomegalovirus G protein-coupled receptor US28 promotes latency by attenuating c-fos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1755–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisser, P.S.; Laurent, L.; Virelizier, J.L.; Michelson, S. Human cytomegalovirus chemokine receptor gene US28 is transcribed in latently infected THP-1 monocytes. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 5949–5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Zhu, H.; Shenk, T. Human cytomegalovirus IE1 and IE2 proteins are mutagenic and mediate “hit-and-run” oncogenic transformation in cooperation with the adenovirus E1A proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 3341–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Liu, D.; Fang, S.; Ma, W.; Wang, Y. Cytomegalovirus and Glioblastoma: A Review of the Biological Associations and Therapeutic Strategies. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimato, G.; Zhou, X.; Brune, W.; Frascaroli, G. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein variants governing viral tropism and syncytium formation in epithelial cells and macrophages. J. Virol. 2024, 98, e0029324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maussang, D.; Langemeijer, E.; Fitzsimons, C.P.; Stigter-van Walsum, M.; Dijkman, R.; Borg, M.K.; Slinger, E.; Schreiber, A.; Michel, D.; Tensen, C.P.; et al. The Human Cytomegalovirus–Encoded Chemokine Receptor US28 Promotes Angiogenesis and Tumor Formation via Cyclooxygenase-2. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 2861–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrum, F.; Reeves, M.; Sinclair, J.; High, K.; Shenk, T. Human cytomegalovirus sequences expressed in latently infected individuals promote a latent infection in vitro. Blood 2007, 110, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, E.; Lau, J.; Groves, I.; Roche, K.; Murphy, E.; Carlan da Silva, M.; Reeves, M.; Sinclair, J. The Human Cytomegalovirus Latency-Associated Gene Product Latency Unique Natural Antigen Regulates Latent Gene Expression. Viruses 2023, 15, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossini, G.; Cerboni, C.; Santoni, A.; Landini, M.P.; Landolfo, S.; Gatti, D.; Gribaudo, G.; Varani, S. Interplay between human cytomegalovirus and intrinsic/innate host responses: A complex bidirectional relationship. Mediat. Inflamm. 2012, 2012, 607276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.S.; Walther-Jallow, L.; Buentke, E.; Ljunggren, H.-G.; Achour, A.; Chambers, B.J. Human cytomegalovirus-derived protein UL18 alters the phenotype and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2007, 83, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bego, M.G.; Keyes, L.R.; Maciejewski, J.; St Jeor, S.C. Human cytomegalovirus latency-associated protein LUNA is expressed during HCMV infections in vivo. Arch. Virol. 2011, 156, 1847–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M.; Woodhall, D.; Compton, T.; Sinclair, J. Human Cytomegalovirus IE72 Protein Interacts with the Transcriptional Repressor hDaxx To Regulate LUNA Gene Expression during Lytic Infection. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 7185–7194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, G.W.G.; Tomasec, P.; Stanton, R.J.; Armstrong, M.; Prod’homme, V.; Aicheler, R.; McSharry, B.P.; Rickards, C.R.; Cochrane, D.; Llewellyn-Lacey, S.; et al. Modulation of natural killer cells by human cytomegalovirus. J. Clin. Virol. 2008, 41, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, L.; Di Benedetto, S. Immunosenescence and Cytomegalovirus: Exploring Their Connection in the Context of Aging, Health, and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crawford, L.B. Hematopoietic stem cells and betaherpesvirus latency. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1189805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wilkie, A.R.; Weller, M.; Liu, X.; Cohen, J.I. THY-1 Cell Surface Antigen (CD90) Has an Important Role in the Initial Stage of Human Cytomegalovirus Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukowati, C.H.; Anfuso, B.; Torre, G.; Francalanci, P.; Crocè, L.S.; Tiribelli, C. The expression of CD90/Thy-1 in hepatocellular carcinoma: An in vivo and in vitro study. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e76830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomuleasa, C.; Soritau, O.; Rus-Ciuca, D.; Ioani, H.; Susman, S.; Petrescu, M.; Timis, T.; Cernea, D.; Kacso, G.; Irimie, A.; et al. Functional and molecular characterization of glioblastoma multiforme-derived cancer stem cells. J. Buon 2010, 15, 583–591. [Google Scholar]

- Lobba, A.R.M.; Carreira, A.C.O.; Cerqueira, O.L.D.; Fujita, A.; DeOcesano-Pereira, C.; Osorio, C.A.B.; Soares, F.A.; Rameshwar, P.; Sogayar, M.C. High CD90 (THY-1) expression positively correlates with cell transformation and worse prognosis in basal-like breast cancer tumors. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, E.V.; Saygin, C.; Braley, C.; Wiechert, A.C.; Karunanithi, S.; Crean-Tate, K.; Abdul-Karim, F.W.; Michener, C.M.; Rose, P.G.; Lathia, J.D.; et al. Thy-1 predicts poor prognosis and is associated with self-renewal in ovarian cancer. J. Ovarian Res. 2019, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avril, T.; Etcheverry, A.; Pineau, R.; Obacz, J.; Jegou, G.; Jouan, F.; Le Reste, P.-J.; Hatami, M.; Colen, R.R.; Carlson, B.L. CD90 expression controls migration and predicts dasatinib response in glioblastoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 7360–7374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahnassy, A.A.; Fawzy, M.; El-Wakil, M.; Zekri, A.-R.N.; Abdel-Sayed, A.; Sheta, M. Aberrant expression of cancer stem cell markers (CD44, CD90, and CD133) contributes to disease progression and reduced survival in hepatoblastoma patients: 4-year survival data. Transl. Res. 2015, 165, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buccisano, F.; Rossi, F.M.; Venditti, A.; Poeta, G.D.; Cox, M.C.; Abbruzzese, E.; Rupolo, M.; Berretta, M.; Degan, M.; Russo, S. CD90/Thy-1 is preferentially expressed on blast cells of high risk acute myeloid leukaemias. Br. J. Haematol. 2004, 125, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abeysinghe, H.R.; Cao, Q.; Xu, J.; Pollock, S.; Veyberman, Y.; Guckert, N.L.; Keng, P.; Wang, N. THY1 expression is associated with tumor suppression of human ovarian cancer. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2003, 143, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiegel, H.C.; Kaifi, J.T.; Quaas, A.; Varol, E.; Krickhahn, A.; Metzger, R.; Sauter, G.; Till, H.; Izbicki, J.R.; Erttmann, R. Lack of Thy1 (CD90) expression in neuroblastomas is correlated with impaired survival. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2008, 24, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lung, H.L.; Bangarusamy, D.K.; Xie, D.; Cheung, A.K.L.; Cheng, Y.; Kumaran, M.K.; Miller, L.; Liu, E.T.-B.; Guan, X.-Y.; Sham, J.S. THY1 is a candidate tumour suppressor gene with decreased expression in metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncogene 2005, 24, 6525–6532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanarsdall, A.L.; Wisner, T.W.; Lei, H.; Kazlauskas, A.; Johnson, D.C. PDGF Receptor-α Does Not Promote HCMV Entry into Epithelial and Endothelial Cells but Increased Quantities Stimulate Entry by an Abnormal Pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8, e1002905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Prager, A.; Boos, S.; Resch, M.; Brizic, I.; Mach, M.; Wildner, S.; Scrivano, L.; Adler, B. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein complex gH/gL/gO uses PDGFR-α as a key for entry. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Tang, X.; McMullen, T.P.W.; Brindley, D.N.; Hemmings, D.G. PDGFR? Enhanced Infection of Breast Cancer Cells with Human Cytomegalovirus but Infection of Fibroblasts Increased Prometastatic Inflammation Involving Lysophosphatidate Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soroceanu, L.; Akhavan, A.; Cobbs, C.S. Platelet-derived growth factor-α receptor activation is required for human cytomegalovirus infection. Nature 2008, 455, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stegmann, C.; Rothemund, F.; Sampaio, K.L.; Adler, B.; Sinzger, C. The N Terminus of Human Cytomegalovirus Glycoprotein O Is Important for Binding to the Cellular Receptor PDGFRα. J. Virol. 2019, 93, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cenciarelli, C.; Marei, H.E.; Felsani, A.; Casalbore, P.; Sica, G.; Puglisi, M.A.; Cameron, A.J.; Olivi, A.; Mangiola, A. PDGFRα depletion attenuates glioblastoma stem cells features by modulation of STAT3, RB1 and multiple oncogenic signals. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, S.; Snyder, C.S.; Wang, A.; McLean, K.; Zamarin, D.; Buckanovich, R.J.; Mehta, G. Carcinoma-Associated Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote Chemoresistance in Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells via PDGF Signaling. Cancers 2020, 12, 2063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciosa, G.; Nieddu, V.; Battistini, C.; Caffarini, M.; Lupia, M.; Colombo, N.; Fusco, N.; Olsen, J.V.; Cavallaro, U. Quantitative Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics Analysis of Patient-Derived Ovarian Cancer Stem Cells. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2025, 24, 100965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szubert, S.; Moszynski, R.; Szpurek, D.; Romaniuk, B.; Sajdak, S.; Nowicki, M.; Michalak, S. The expression of Platelet-derived Growth factor receptors (PDGFRs) and their correlation with overall survival of patients with ovarian cancer. Ginekol. Pol. 2019, 90, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, R.; Muñoz, J.P. Molecular Insights into HR-HPV and HCMV Co-Presence in Cervical Cancer Development. Cancers 2025, 17, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.-D.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, C.; Liu, S.-X.; Duan, H.; Cui, R.; Zhong, Q.; Mou, Y.-G.; Wen, L. EphA2 is a functional entry receptor for HCMV infection of glioblastoma cells. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psilopatis, I.; Pergaris, A.; Vrettou, K.; Tsourouflis, G.; Theocharis, S. The EPH/Ephrin System in Gynecological Cancers: Focusing on the Roots of Carcinogenesis for Better Patient Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbein, G. High-Risk Oncogenic Human Cytomegalovirus. Viruses 2022, 14, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Fan, Z.; Huang, W.; Huo, X.; Yang, X.; Ran, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, H. Human cytomegalovirus UL23 exploits PD-L1 inhibitory signaling pathway to evade T cell-mediated cytotoxicity. mBio 2024, 15, e01191-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuessler, A.; Walker, D.G.; Khanna, R. Cytomegalovirus as a Novel Target for Immunotherapy of Glioblastoma Multiforme. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanc-Durand, F.; Clemence Wei Xian, L.; Tan, D.S.P. Targeting the immune microenvironment for ovarian cancer therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1328651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, S.; Wei, J.; Bai, J. Construction of an Immune Cell Infiltration Score to Evaluate the Prognosis and Therapeutic Efficacy of Ovarian Cancer Patients. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 751594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Feng, W.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Lu, M.; Xue, X.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus tegument protein UL23 promotes gastric cancer immune evasion by facilitating PD-L1 transcription. Mol. Med. 2025, 31, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milotay, G.; Little, M.; Watson, R.A.; Muldoon, D.; MacKay, S.; Kurioka, A.; Tong, O.; Taylor, C.A.; Nassiri, I.; Webb, L.M.; et al. CMV serostatus is associated with improved survival and delayed toxicity onset following anti-PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Nat. Med. 2025, 31, 2350–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Fang, X.; Qian, D.; Liu, X.; Liu, T.; Li, L.; Yu, H.; et al. TLR3 regulates PD-L1 expression in human cytomegalovirus infected glioblastoma. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018, 11, 5318–5326. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, J.; Sun, Q.; Tian, Q.; Shi, H.; Yang, H.; Ren, J. Human papillomavirus 16 E6/E7 contributes to immune escape and progression of cervical cancer by regulating miR-142–5p/PD-L1 axis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2022, 731, 109449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ge, J.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, F.; Guo, J.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, L.; Deng, X.; Gong, Z.; Zhang, S.; et al. EBV miRNAs BART11 and BART17-3p promote immune escape through the enhancer-mediated transcription of PD-L1. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Sun, L.; Li, G.; Liang, J.; Hu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; et al. Molecular and clinical characterization of PD-L1 expression at transcriptional level via 976 samples of brain glioma. Oncoimmunology 2016, 5, e1196310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohaegbulam, K.C.; Assal, A.; Lazar-Molnar, E.; Yao, Y.; Zang, X. Human cancer immunotherapy with antibodies to the PD-1 and PD-L1 pathway. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parry, R.V.; Chemnitz, J.M.; Frauwirth, K.A.; Lanfranco, A.R.; Braunstein, I.; Kobayashi, S.V.; Linsley, P.S.; Thompson, C.B.; Riley, J.L. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Receptors Inhibit T-Cell Activation by Distinct Mechanisms. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 9543–9553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.H.; Gillett, M.D.; Cheville, J.C.; Lohse, C.M.; Dong, H.; Webster, W.S.; Krejci, K.G.; Lobo, J.R.; Sengupta, S.; Chen, L.; et al. Costimulatory B7-H1 in renal cell carcinoma patients: Indicator of tumor aggressiveness and potential therapeutic target. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17174–17179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisoni, E.; Imbimbo, M.; Zimmermann, S.; Valabrega, G. Ovarian Cancer Immunotherapy: Turning up the Heat. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jiang, B.; Zhou, H.; Yang, S.; Yang, L.; Hong, Y. Development of a prognostic immune cell-based model for ovarian cancer using multiplex immunofluorescence. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiko, K.; Matsumura, N.; Hamanishi, J.; Horikawa, N.; Murakami, R.; Yamaguchi, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Baba, T.; Konishi, I.; Mandai, M. IFN-γ from lymphocytes induces PD-L1 expression and promotes progression of ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamanishi, J.; Mandai, M.; Iwasaki, M.; Okazaki, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Yamaguchi, K.; Higuchi, T.; Yagi, H.; Takakura, K.; Minato, N.; et al. Programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes are prognostic factors of human ovarian cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 3360–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwai, Y.; Hamanishi, J.; Chamoto, K.; Honjo, T. Cancer immunotherapies targeting the PD-1 signaling pathway. J. Biomed. Sci. 2017, 24, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darb-Esfahani, S.; Kunze, C.A.; Kulbe, H.; Sehouli, J.; Wienert, S.; Lindner, J.; Budczies, J.; Bockmayr, M.; Dietel, M.; Denkert, C.; et al. Prognostic impact of programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and PD-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression in cancer cells and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in ovarian high grade serous carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 1486–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, J.R.; Milne, K.; Kroeger, D.R.; Nelson, B.H. PD-L1 expression is associated with tumor-infiltrating T cells and favorable prognosis in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. 2016, 141, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, J.S.; Paliwal, S.; Singhvi, G.; Taliyan, R. Immunological challenges and opportunities in glioblastoma multiforme: A comprehensive view from immune system lens. Life Sci. 2024, 357, 123089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, E.V.; Collins-McMillen, D.; Kim, J.H.; Cieply, S.J.; Bentz, G.L.; Yurochko, A.D. HCMV reprogramming of infected monocyte survival and differentiation: A Goldilocks phenomenon. Viruses 2014, 6, 782–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Chen, N.G. miR-146a: Overcoming coldness in ovarian cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2023, 31, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R.F.; Verweij, M.C.; Nair, S.S.; Morrow, D.; Mansouri, M.; Chakravarty, D.; Beechwood, T.; Meyer, C.; Uebelhoer, L.; Lauron, E.J.; et al. CD8+ T cell targeting of tumor antigens presented by HLA-E. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadm7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Tang, Y.; Zhuang, X.; Feng, W.; Boor, P.P.C.; Buschow, S.; Sprengers, D.; Zhou, G. Unlocking the therapeutic potential of the NKG2A-HLA-E immune checkpoint pathway in T cells and NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer 2024, 12, e009934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Guan, X.; Meng, X.; Tong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xie, S.; Guo, L.; Lu, R. IFN-γ in ovarian tumor microenvironment upregulates HLA-E expression and predicts a poor prognosis. J. Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbrecht, M.; Martinozzi, S.; Grzeschik, M.; Hengel, H.; Ellwart, J.W.; Pla, M.; Weiss, E.H. Cutting Edge: The Human Cytomegalovirus UL40 Gene Product Contains a Ligand for HLA-E and Prevents NK Cell-Mediated Lysis1. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 5019–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasec, P.; Braud, V.M.; Rickards, C.; Powell, M.B.; McSharry, B.P.; Gadola, S.; Cerundolo, V.; Borysiewicz, L.K.; McMichael, A.J.; Wilkinson, G.W.G. Surface Expression of HLA-E, an Inhibitor of Natural Killer Cells, Enhanced by Human Cytomegalovirus gpUL40. Science 2000, 287, 1031–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.-Y.; Lv, Y.-G.; Wang, L.; Shi, S.-J.; Yang, F.; Zheng, G.-X.; Wen, W.-H.; Yang, A.-G. Predictive value of HLA-G and HLA-E in the prognosis of colorectal cancer patients. Cell. Immunol. 2015, 293, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Z.-J.; Ling, J.-Y.; Cai, Y.; Luo, W.-B.; He, Y.-J. Impact of HLA-E gene polymorphism on HLA-E expression in tumor cells and prognosis in patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Med. Oncol. 2013, 30, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, E.M.; Bianchini, M.; Von Euw, E.M.; Barrio, M.M.; Bravo, A.I.; Furman, D.; Domenichini, E.; Macagno, C.; Pinsky, V.; Zucchini, C.; et al. Human leukocyte antigen-E protein is overexpressed in primary human colorectal cancer. Int. J. Oncol. 2008, 32, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kruijf, E.M.; Sajet, A.; van Nes, J.G.H.; Natanov, R.; Putter, H.; Smit, V.T.H.B.M.; Liefers, G.J.; van den Elsen, P.J.; van de Velde, C.J.H.; Kuppen, P.J.K. HLA-E and HLA-G Expression in Classical HLA Class I-Negative Tumors Is of Prognostic Value for Clinical Outcome of Early Breast Cancer Patients. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 7452–7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrbac, T.; Kopkova, A.; Siegl, F.; Vecera, M.; Ruckova, M.; Kazda, T.; Jancalek, R.; Hendrych, M.; Hermanová, M.; Vybíhal, V. HLA-E and HLA-F are overexpressed in glioblastoma and HLA-E increased after exposure to ionizing radiation. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2022, 19, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morinaga, T.; Iwatsuki, M.; Yamashita, K.; Matsumoto, C.; Harada, K.; Kurashige, J.; Iwagami, S.; Baba, Y.; Yoshida, N.; Komohara, Y. Evaluation of HLA-E expression combined with natural killer cell status as a prognostic factor for advanced gastric cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 29, 4951–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooden, M.; Lampen, M.; Jordanova, E.S.; Leffers, N.; Trimbos, J.B.; van der Burg, S.H.; Nijman, H.; van Hall, T. HLA-E expression by gynecological cancers restrains tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10656–10661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E.; Poschke, I.; Villabona, L.; Carlson, J.W.; Lundqvist, A.; Kiessling, R.; Seliger, B.; Masucci, G.V. Non-classical HLA-class I expression in serous ovarian carcinoma: Correlation with the HLA-genotype, tumor infiltrating immune cells and prognosis. OncoImmunology 2016, 5, e1052213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagana, A.; Ruan, D.F.; Melnekoff, D.; Leshchenko, V.; Perumal, D.; Rahman, A.; Kim-Schultze, S.; Song, Y.; Keats, J.J.; Yesil, J. Increased HLA-E expression correlates with early relapse in multiple myeloma. Blood 2018, 132, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sætersmoen, M.; Kotchetkov, I.S.; Torralba-Raga, L.; Mansilla-Soto, J.; Sohlberg, E.; Krokeide, S.Z.; Hammer, Q.; Sadelain, M.; Malmberg, K.-J. Targeting HLA-E-overexpressing cancers with a NKG2A/C switch receptor. Med 2025, 6, 100521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, C.; Déchanet-Merville, J.; Capone, M. γδ T Cell-Mediated Immunity to Cytomegalovirus Infection. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Sheng, J.; Vu, G.-P.; Liu, Y.; Foo, C.; Wu, S.; Trang, P.; Paliza-Carre, M.; Ran, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Human cytomegalovirus UL23 inhibits transcription of interferon-γ stimulated genes and blocks antiviral interferon-γ responses by interacting with human N-myc interactor protein. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1006867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmberg, K.-J.; Levitsky, V.; Norell, H.; Matos, C.T.d.; Carlsten, M.; Schedvins, K.; Rabbani, H.; Moretta, A.; Söderström, K.; Levitskaya, J.; et al. IFN-γ protects short-term ovarian carcinoma cell lines from CTL lysis via a CD94/NKG2A-dependent mechanism. J. Clin. Investig. 2002, 110, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Conejo-Garcia, J.R.; Katsaros, D.; Gimotty, P.A.; Massobrio, M.; Regnani, G.; Makrigiannakis, A.; Gray, H.; Schlienger, K.; Liebman, M.N.; et al. Intratumoral T Cells, Recurrence, and Survival in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shinawi, M.; Mohamed, H.T.; El-Ghonaimy, E.A.; Tantawy, M.; Younis, A.; Schneider, R.J.; Mohamed, M.M. Human Cytomegalovirus Infection Enhances NF-κB/p65 Signaling in Inflammatory Breast Cancer Patients. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, C.; Schafer, X.; Martínez-Sobrido, L.; Munger, J. The Human Cytomegalovirus UL26 Protein Antagonizes NF-κB Activation. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 14289–14300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, L.; Joo, D.; Sun, S.C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2017, 2, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soroceanu, L.; Matlaf, L.; Bezrookove, V.; Harkins, L.; Martinez, R.; Greene, M.; Soteropoulos, P.; Cobbs, C.S. Human cytomegalovirus US28 found in glioblastoma promotes an invasive and angiogenic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 6643–6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahbar, A.; AlKharusi, A.; Costa, H.; Pantalone, M.R.; Kostopoulou, O.N.; Cui, H.L.; Carlsson, J.; Rådestad, A.F.; Söderberg-Naucler, C.; Norstedt, G. Human Cytomegalovirus Infection Induces High Expression of Prolactin and Prolactin Receptors in Ovarian Cancer. Biology 2020, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkharusi, A.; Lesma, E.; Ancona, S.; Chiaramonte, E.; Nyström, T.; Gorio, A.; Norstedt, G. Role of Prolactin Receptors in Lymphangioleiomyomatosis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, S.; Laganà, A.S.; Casarin, J.; Raffaelli, R.; Cromi, A.; Franchi, M.; Barra, F.; Alkatout, I.; Ferrero, S.; Ghezzi, F. Secondary and tertiary ovarian cancer recurrence: What is the best management? Gland. Surg. 2020, 9, 1118–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmi, Y.; Jalali, L.; Khalid, S.; Shokati, A.; Tyagi, P.; Ozturk, A.; Nasimfar, A. The effects of prolactin on the immune system, its relationship with the severity of COVID-19, and its potential immunomodulatory therapeutic effect. Cytokine 2023, 169, 156253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodrigo, J.F.; Ortiz, G.; Martínez-Díaz, O.F.; Furuzawa-Carballeda, J.; Ruíz-Herrera, X.; Macias, F.; Ledesma-Colunga, M.G.; Martínez de la Escalera, G.; Clapp, C. Prolactin Inhibits or Stimulates the Inflammatory Response of Joint Tissues in a Cytokine-dependent Manner. Endocrinology 2023, 164, bqad156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampan, N.C.; Madondo, M.T.; McNally, O.M.; Stephens, A.N.; Quinn, M.A.; Plebanski, M. Interleukin 6 Present in Inflammatory Ascites from Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients Promotes Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 2-Expressing Regulatory T Cells. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonetti, C.R.; de Souza-Araújo, C.N.; Yoshida, A.; da Silva, R.F.; Alves, P.C.M.; Mazzola, T.N.; Derchain, S.; Fernandes, L.G.R.; Guimarães, F. Ovarian Cancer-Associated Ascites Have High Proportions of Cytokine-Responsive CD56bright NK Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Gong, H.; Zou, K.; Li, B.; Ran, X.; Wen, W.; Li, Z. IL-10 in Advanced Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Ascites Could Promote the Metastasis and Invasion of Ovarian Cancer Cells Via STAT3 and ERK1/2 Phosphorylation. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinartz, S.; Finkernagel, F.; Adhikary, T.; Rohnalter, V.; Schumann, T.; Schober, Y.; Nockher, W.A.; Nist, A.; Stiewe, T.; Jansen, J.M.; et al. A transcriptome-based global map of signaling pathways in the ovarian cancer microenvironment associated with clinical outcome. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Tang, X.; Hasing, M.E.; Pang, X.; Ghosh, S.; McMullen, T.P.W.; Brindley, D.N.; Hemmings, D.G. Human Cytomegalovirus Seropositivity and Viral DNA in Breast Tumors Are Associated with Poor Patient Prognosis. Cancers 2022, 14, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.M.; Glaser, R.; Malarkey, W.B.; Beversdorf, D.Q.; Peng, J.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. Inflammation and reactivation of latent herpesviruses in older adults. Brain Behav. Immun. 2012, 26, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K.; Son, M.-J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-A.; Ko, D.-H.; Yoo, S.; Kim, C.-H.; Kim, Y.-S. Antibody-mediated delivery of a viral MHC-I epitope into the cytosol of target tumor cells repurposes virus-specific CD8+ T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millar, D.G.; Ramjiawan, R.R.; Kawaguchi, K.; Gupta, N.; Chen, J.; Zhang, S.; Nojiri, T.; Ho, W.W.; Aoki, S.; Jung, K. Antibody-mediated delivery of viral epitopes to tumors harnesses CMV-specific T cells for cancer therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yan, C.; Millar, D.G.; Yang, Q.; Heather, J.M.; Langenbucher, A.; Morton, L.T.; Sepulveda, S.; Alpert, E.; Whelton, L.R.; et al. Antibody-Peptide Epitope Conjugates for Personalized Cancer Therapy. Cancer Res. 2022, 82, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britsch, I.; van Wijngaarden, A.P.; Helfrich, W. Applications of Anti-Cytomegalovirus T Cells for Cancer (Immuno)Therapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çuburu, N.; Bialkowski, L.; Pontejo, S.M.; Sethi, S.K.; Bell, A.T.F.; Kim, R.; Thompson, C.D.; Lowy, D.R.; Schiller, J.T. Harnessing anti-cytomegalovirus immunity for local immunotherapy against solid tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2116738119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Urak, R.; Walter, M.; Guan, M.; Han, T.; Vyas, V.; Chien, S.H.; Gittins, B.; Clark, M.C.; Mokhtari, S.; et al. Large-scale manufacturing and characterization of CMV-CD19CAR T cells. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.Y.; Anderson, A.D.; Natori, Y.; Raja, M.; Morris, M.I.; Jimenez, A.J.; Beitinjaneh, A.; Wang, T.; Goodman, M.; Lekakis, L.; et al. Incidence and outcomes of cytomegalovirus reactivation after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Blood Adv. 2024, 8, 3813–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, H.E.; Bruce, K.; Stevenson, P.G. A Live Olfactory Mouse Cytomegalovirus Vaccine, Attenuated for Systemic Spread, Protects against Superinfection. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0126421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kschonsak, M.; Johnson, M.C.; Schelling, R.; Green, E.M.; Rougé, L.; Ho, H.; Patel, N.; Kilic, C.; Kraft, E.; Arthur, C.P. Structural basis for HCMV Pentamer receptor recognition and antibody neutralization. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabm2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-J.; Wang, S.-C.; Chen, Y.-C. Challenges, Recent Advances and Perspectives in the Treatment of Human Cytomegalovirus Infections. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, T.; Hò, G.T.; Pump, W.C.; Blasczyk, R.; Bade-Doeding, C. Battle between Host Immune Cellular Responses and HCMV Immune Evasion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryawno, N.; Rahbar, A.; Wolmer-Solberg, N.; Taher, C.; Odeberg, J.; Darabi, A.; Khan, Z.; Sveinbjörnsson, B.; FuskevÅg, O.M.; Segerström, L.; et al. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in medulloblastomas reveals a potential therapeutic target. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 4043–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantalone, M.R.; Rahbar, A.; Söderberg-Naucler, C.; Stragliotto, G. Valganciclovir as Add-on to Second-Line Therapy in Patients with Recurrent Glioblastoma. Cancers 2022, 14, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stragliotto, G.; Pantalone, M.R.; Rahbar, A.; Bartek, J.; Söderberg-Naucler, C. Valganciclovir as Add-on to Standard Therapy in Glioblastoma Patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 4031–4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieberler, M.; Reuning, U.; Reichart, F.; Notni, J.; Wester, H.-J.; Schwaiger, M.; Weinmüller, M.; Räder, A.; Steiger, K.; Kessler, H. Exploring the Role of RGD-Recognizing Integrins in Cancer. Cancers 2017, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhi, M.K.; Rizvi, I.; Rickard, B.; Polacheck, W.J. Integrins in Ovarian Cancer: Survival Pathways, Malignant Ascites and Targeted Photochemistry. In Recent Advances, New Perspectives and Applications in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer; Friedrich, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Batich, K.A.; Reap, E.A.; Archer, G.E.; Sanchez-Perez, L.; Nair, S.K.; Schmittling, R.J.; Norberg, P.; Xie, W.; Herndon, J.E.; Healy, P. Long-term survival in glioblastoma with cytomegalovirus pp65-targeted vaccination. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 1898–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, S.K.; De Leon, G.; Boczkowski, D.; Schmittling, R.; Xie, W.; Staats, J.; Liu, R.; Johnson, L.A.; Weinhold, K.; Archer, G.E. Recognition and killing of autologous, primary glioblastoma tumor cells by human cytomegalovirus pp65-specific cytotoxic T cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 2684–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Prototype/Wild-Type | Clinical Isolate | Laboratory Strain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Strains | Merlin | HCMV-DB, HCMV-BL, VR1814, Toledo | AD169, Towne, TB40/E, and TB40/E-BAC4 |

| Genomic Mutations | RL13, UL128 [38,39] | RL13, UL9, UL128, UL141 [38,39,40] | RL13, * UL128, UL130, UL131A, IRS1, US1, US2, UL40, UL1 [38,39] |

| Cellular Tropism and Replication | Closest match to clinical wild-type Broad cellular tropism [38] | Broad cellular tropism with macrophage preference Strong replication potential and transformative ability [16,39,41] | Growth restricted to fibroblasts with loss of broad tropism Widely used in research [38,39,42] |

| Oncogenic Potential | Limited data available, baseline for comparison with various strains | Activates oncogenic pathways (growth, survival, metastasis) Induces cellular transformation and EMT Causes epigenetic dysregulation Associated with tumour progression [13,16,21,32,39,40] | Induces genomic instability and DNA damage Promotes stem cell properties Associated with MET Mixed clinical outcomes (enhanced chemotherapy response vs. reduced GBM viability) [37,43,44,45] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giatrakis, C.; Kartikasari, A.E.R.; Angelovich, T.A.; Flanagan, K.L.; Churchill, M.J.; Scott, C.L.; Telukutla, S.R.; Plebanski, M. HCMV as an Oncomodulatory Virus in Ovarian Cancer: Implications of Viral Strain Heterogeneity, Immunomodulation, and Inflammation on the Tumour Microenvironment and Ovarian Cancer Progression. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121685

Giatrakis C, Kartikasari AER, Angelovich TA, Flanagan KL, Churchill MJ, Scott CL, Telukutla SR, Plebanski M. HCMV as an Oncomodulatory Virus in Ovarian Cancer: Implications of Viral Strain Heterogeneity, Immunomodulation, and Inflammation on the Tumour Microenvironment and Ovarian Cancer Progression. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121685

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiatrakis, Chrissie, Apriliana E. R. Kartikasari, Thomas A. Angelovich, Katie L. Flanagan, Melissa J. Churchill, Clare L. Scott, Srinivasa Reddy Telukutla, and Magdalena Plebanski. 2025. "HCMV as an Oncomodulatory Virus in Ovarian Cancer: Implications of Viral Strain Heterogeneity, Immunomodulation, and Inflammation on the Tumour Microenvironment and Ovarian Cancer Progression" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121685

APA StyleGiatrakis, C., Kartikasari, A. E. R., Angelovich, T. A., Flanagan, K. L., Churchill, M. J., Scott, C. L., Telukutla, S. R., & Plebanski, M. (2025). HCMV as an Oncomodulatory Virus in Ovarian Cancer: Implications of Viral Strain Heterogeneity, Immunomodulation, and Inflammation on the Tumour Microenvironment and Ovarian Cancer Progression. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121685