Shanghai Tianma Radio Telescope and Its Role in Pulsar Astronomy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. TMRT and Pulsar Observation Systems

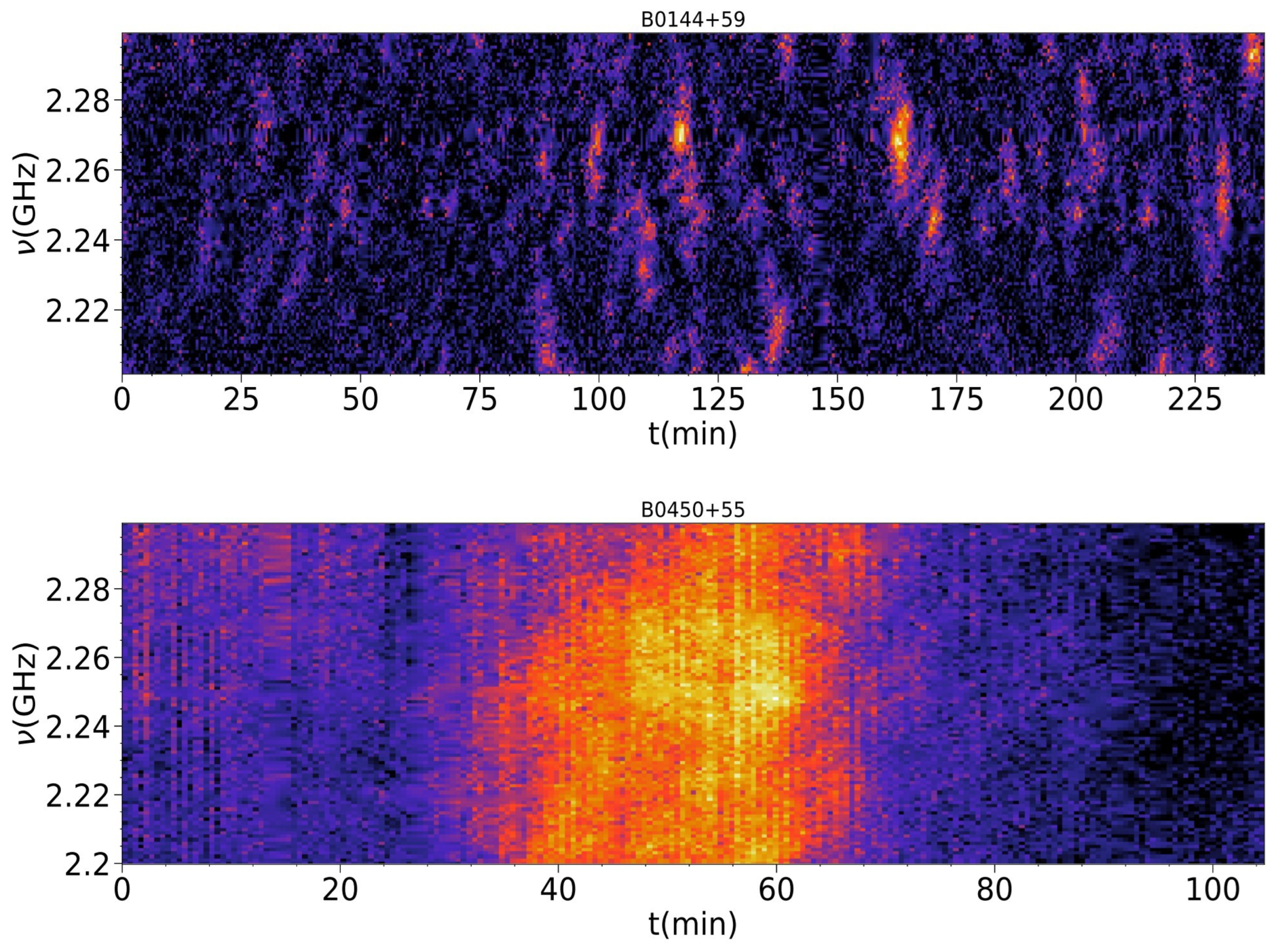

3. Pulsar Observation Projects and Related Results

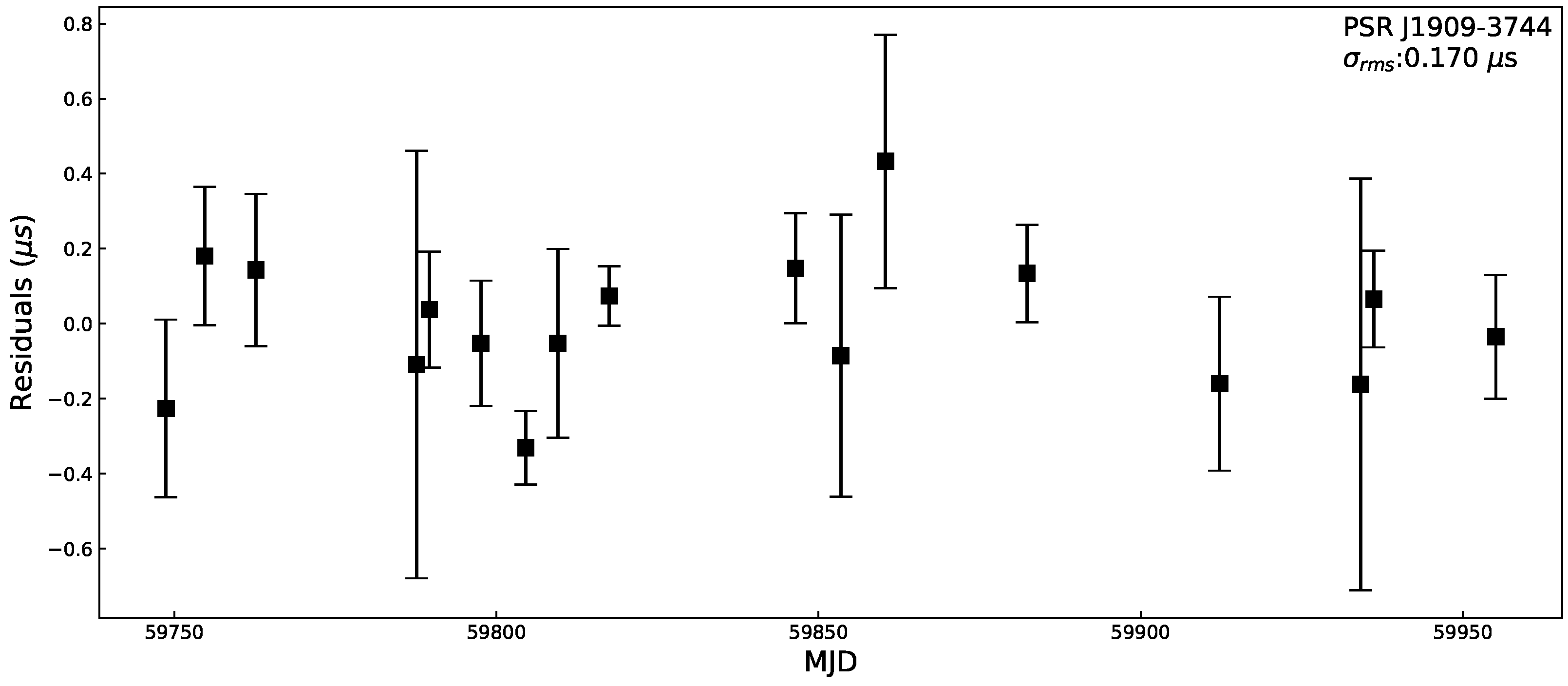

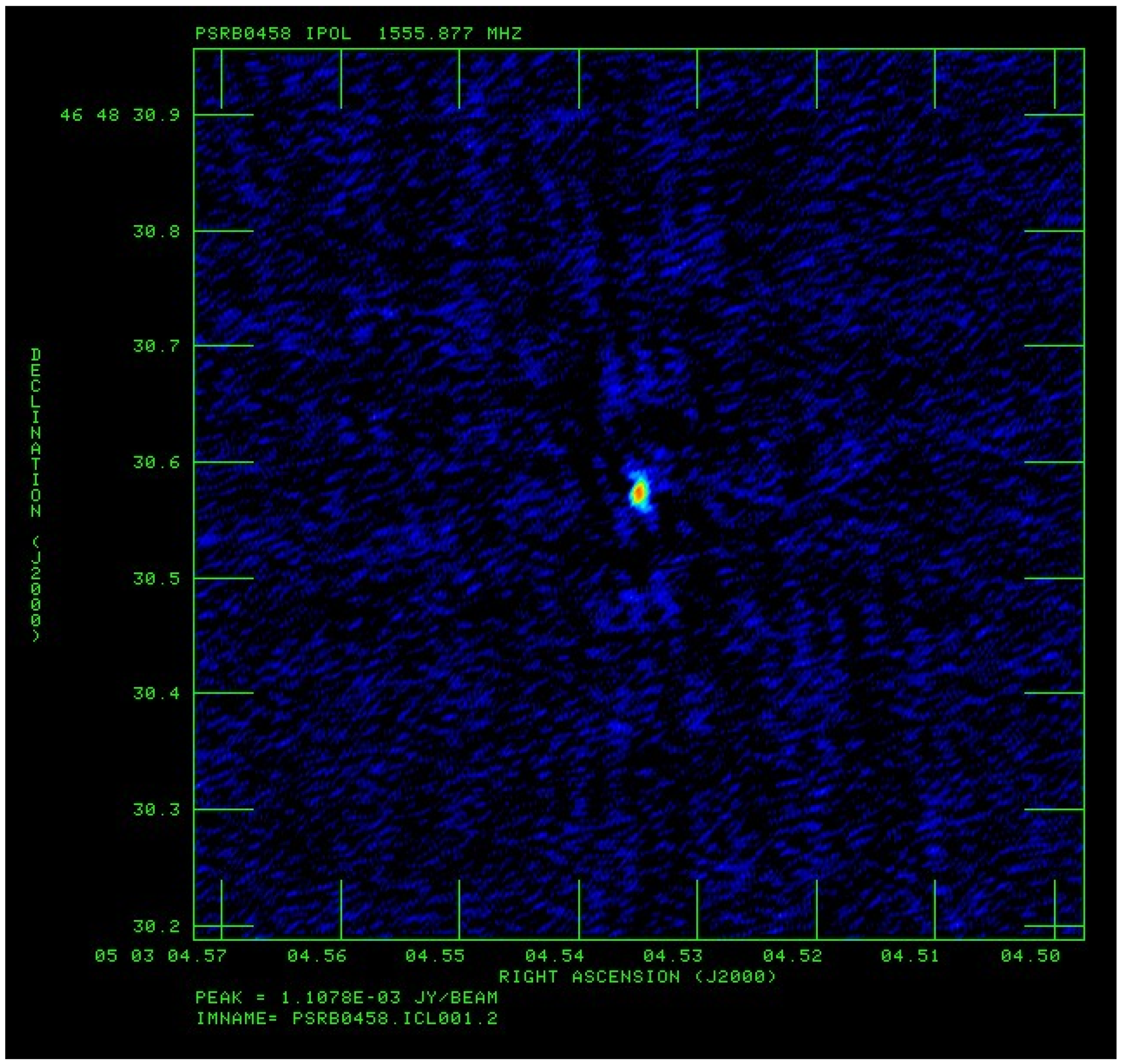

3.1. Long-Term Pulsar Timing

3.2. Magnetar Monitoring

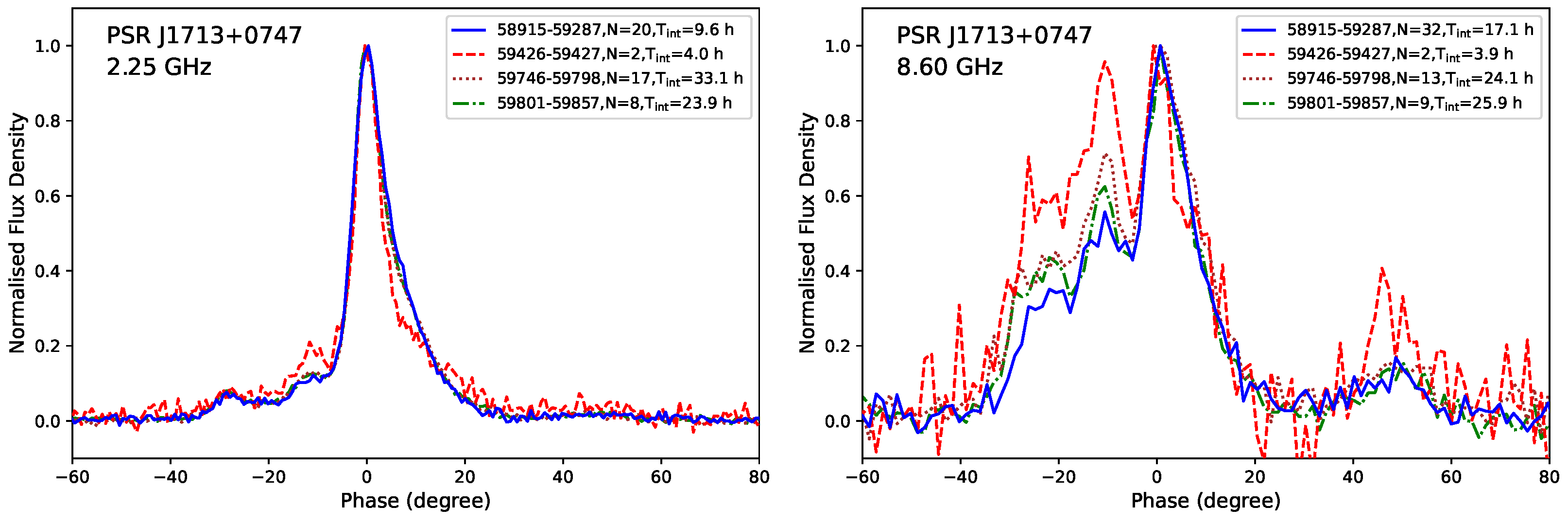

3.3. Multi-Frequency (or High-Frequency) Observations and Pulsar Radiation

4. Pulsar Interstellar Scintillation Observations

5. Pulsar VLBI Observations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| MSP | Millisecond pulsar |

| S1400 | Flux density at 1400 MHz |

| TMRT | Tianma Radio Telescope |

| SEFD | System equivalent flux density |

| DIBAS | Digital backend system |

| NRAO | National Radio Astronomy Observatory |

| GBT | Green Bank Telescope |

| VEGAS | Versatile GBT Astronomical Spectrometer |

| CASPER | Collaboration for Astronomy Signal Processing and Electronics Research |

| GUPPI | Green Bank Ultimate Pulsar Processing Instrument |

| ADC | Analog-to-digital converter |

| HPC | High-performance computing |

| FRB | Fast radio burst |

| VLBI | Very-long-baseline interferometry |

| DBBC2 | Digital Base Band Converter-2 |

| CDAS | Chinese VLBI Data Acquisition System |

| PSRFITS | Pulsar data format based on flexible image transport system |

| TOAs | Pulse times of arrival |

| RFM | Radius-to-frequency mapping |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| 2DFS | Two-dimensional fluctuation spectrum |

| CVN | Chinese VLBI Network |

| EVN | European VLBI Network |

| EAVN | East Asia VLBI Network |

References

- Hewish, A.; Bell, S.J.; Pilkington, J.D.H.; Scott, P.F.; Collins, R.A. Observation of a Rapidly Pulsating Radio Source. Nature 1968, 217, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester, R.N.; Hobbs, G.B.; Teoh, A.; Hobbs, M. The Australia Telescope National Facility Pulsar Catalogue. Astron. J. 2005, 129, 1993–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, J.; Kramer, M.; Lazio, T.; Stappers, B.; Backer, D.; Johnston, S. Pulsars as tools for fundamental physics & astrophysics. New Astron. Rev. 2004, 48, 1413–1438. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.X. Pulsars and Quark Stars. Chin. J. Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 6, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickett, B.J. Radio Propagation through the Turbulent Interstellar Plasma. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 1990, 28, 561–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.L.; Manchester, R.N.; Lyne, A.G.; Qiao, G.J.; van Straten, W. Pulsar rotation measures and the large-scale structure of the Galactic magnetic field. Astrophys. J. 2006, 642, 868–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, D.J.; Zic, A.; Shannon, R.M.; Hobbs, G.B.; Bailes, M.; Di Marco, V.; Kapur, A.; Rogers, A.F.; Thrane, E.; Askew, J.; et al. Search for an Isotropic Gravitational-wave Background with the Parkes Pulsar Timing Array. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2023, 951, L6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agazie, G.; Anumarlapudi, A.; Archibald, A.M.; Arzoumanian, Z.; Baker, P.T.; Bécsy, B.; Blecha, L.; Brazier, A.; Brook, P.R.; Burke-Spolaor, S.; et al. The NANOGrav 15 yr Data Set: Evidence for a Gravitational-wave Background. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2023, 951, L8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chen, S.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, J.; Wang, B.; Xu, J.; Xue, Z.; Nicolas Caballero, R.; Yuan, J.; Xu, Y.; et al. Searching for the Nano-Hertz Stochastic Gravitational Wave Background with the Chinese Pulsar Timing Array Data Release I. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 23, 075024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, G.; Coles, W.; Manchester, R.N.; Keith, M.J.; Shannon, R.M.; Chen, D.; Bailes, M.; Bhat, N.D.R.; Burke-Spolaor, S.; Champion, D.; et al. Development of a pulsar-based timescale. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 427, 2780–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulse, R.A.; Taylor, J.H. Discovery of a pulsar in a binary system. Astrophys. J. Lett. 1975, 195, L51–L53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.H., Jr. Binary pulsars and relativistic gravity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1994, 66, 711–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolszczan, A.; Frail, D.A. A planetary system around the millisecond pulsar PSR1257 + 12. Nature 1992, 355, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, M.; Queloz, D. A Jupiter-mass companion to a solar-type star. Nature 1995, 378, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faucher-Giguère, C.A.; Kaspi, V.M. Birth and Evolution of Isolated Radio Pulsars. Astrophys. J. 2006, 643, 332–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattimer, J.M.; Prakash, M. The Physics of Neutron Stars. Science 2004, 304, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippov, A.; Kramer, M. Pulsar Magnetospheres and Their Radiation. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2022, 60, 495–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester, R.N. Observational Properties of Pulsars. Science 2004, 304, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorimer, D.R. Binary and Millisecond Pulsars. Living Rev. Relativ. 2008, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beskin, V.S. Radio pulsars: Already fifty years! Phys. Uspekhi 2018, 61, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zic, A.; Reardon, D.J.; Kapur, A.; Hobbs, G.; Mandow, R.; Curyło, M.; Shannon, R.M.; Askew, J.; Bailes, M.; Bhat, N.D.R.; et al. The Parkes Pulsar Timing Array third data release. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2023, 40, e049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadis, J.; Arumugam, P.; Arumugam, S.; Babak, S.; Bagchi, M.; Bak Nielsen, A.S.; Bassa, C.G.; Bathula, A.; Berthereau, A.; Bonetti, M.; et al. [EPTA Collaboration; InPTA Collaboration]. The second data release from the European Pulsar Timing Array. III. Search for gravitational wave signals. Astron. Astrophys. 2023, 678, A50. [Google Scholar]

- Altschuler, D.R.; Salter, C.J. The Arecibo Observatory: Fifty astronomical years. Phys. Today 2013, 66, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransom, S.M. Pulsars in Globular Clusters. In Proceedings of the Dynamical Evolution of Dense Stellar Systems; Vesperini, E., Giersz, M., Sills, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; Volume 246, pp. 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, R.S. The Green Bank North Celestial Cap Pulsar Survey: Status and Future. In Proceedings of the Pulsar Astrophysics the Next Fifty Years; Weltevrede, P., Perera, B.B.P., Preston, L.L., Sanidas, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Volume 337, pp. 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Barr, E.D.; Champion, D.J.; Kramer, M.; Eatough, R.P.; Freire, P.C.C.; Karuppusamy, R.; Lee, K.J.; Verbiest, J.P.W.; Bassa, C.G.; Lyne, A.G.; et al. The Northern High Time Resolution Universe pulsar survey-I. Setup and initial discoveries. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 435, 2234–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyne, A.; Morison, I. The Lovell Telescope and its role in pulsar astronomy. Nat. Astron. 2017, 1, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester, R.N.; Lyne, A.G.; Camilo, F.; Bell, J.F.; Kaspi, V.M.; D’Amico, N.; McKay, N.P.F.; Crawford, F.; Stairs, I.H.; Possenti, A.; et al. The Parkes multi-beam pulsar survey-I. Observing and data analysis systems, discovery and timing of 100 pulsars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2001, 328, 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.; Tang, N.Y.; Hou, L.G.; Liu, M.T.; Krčo, M.; Qian, L.; Sun, J.H.; Ching, T.C.; Liu, B.; Duan, Y.; et al. The fundamental performance of FAST with 19-beam receiver at L band. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 20, 064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Dickey, J.M.; Liu, S. Preface: Planning the scientific applications of the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical radio Telescope. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 19, 016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.L.; Wang, C.; Wang, P.F.; Wang, T.; Zhou, D.J.; Sun, J.H.; Yan, Y.; Su, W.Q.; Jing, W.C.; Chen, X.; et al. The FAST Galactic Plane Pulsar Snapshot survey: I. Project design and pulsar discoveries. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 21, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Qian, L.; Ma, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, L.; Luo, J.; Yan, Z.; Ransom, S.; Lorimer, D.; Li, D.; et al. FAST Globular Cluster Pulsar Survey: Twenty-four Pulsars Discovered in 15 Globular Clusters. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2021, 915, L28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xiong, F.; Yu, C.; Zhang, J.; Guo, L.; Fan, Q. Precise determination of the reference point coordinates of Shanghai Tianma 65-m radio telescope. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2014, 59, 2558–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zuo, X.; Michael, K.; Zhao, R.; Yu, L.; Jiang, Y.; Gou, W.; Jiang, Y.; Guo, W. TM65 m radio telescope microwave holography. Sci. Sin. Phys. Mech. Astron. 2017, 47, 099502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Fu, L.; Liu, Q.; Shen, Z. Measuring and analyzing thermal deformations of the primary reflector of the Tianma radio telescope. Exp. Astron. 2018, 45, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Wu, Y.J.; Zhao, R.B.; Liu, Q.H. Pulsar studies with Shanghai tian ma radio telescope. In Proceedings of the 2017 XXXIInd General Assembly and Scientific Symposium of the International Union of Radio Science (URSI GASS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 19–26 August 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Wu, Y.J.; Zhao, R.B.; Zhao, R.S.; Liu, J.; Huang, Z.P.; Liu, Q.H.; Wu, X.J. Pulsar research with the newly built Shanghai tian ma radio telescope. URSI Radio Sci. Bull. 2018, 2018, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Prestage, R.M.; Bloss, M.; Brandt, J.; Creager, R.; Demorest, P.; Ford, J.; Jones, G.; Luo, J.; McCullough, R.; Ransom, S.M.; et al. Experiences with the Design and Construction of Astronomical Instrumentation using CASPER: The Digital Backend System. In American Astronomical Society Meeting Abstracts #223; The American Astronomical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Volume 223, p. 148.30. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Wu, X.J.; Manchester, R.N.; Weltevrede, P.; Wu, Y.J.; Zhao, R.B.; Yuan, J.P.; Lee, K.J.; Fan, Q.Y.; et al. Single-pulse Radio Observations of the Galactic Center Magnetar PSR J1745-2900. Astrophys. J. 2015, 814, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankins, T.H. Coherent Dedispersion: History and Results. In Proceedings of the Pulsar Astrophysics the Next Fifty Years; Weltevrede, P., Perera, B.B.P., Preston, L.L., Sanidas, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; Volume 337, pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hotan, A.W.; van Straten, W.; Manchester, R.N. PSRCHIVE and PSRFITS: An Open Approach to Radio Pulsar Data Storage and Analysis. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2004, 21, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yan, Z.; Yuan, J.P.; Zhao, R.S.; Huang, Z.P.; Wu, X.J.; Wang, N.; Shen, Z.Q. One large glitch in PSR B1737-30 detected with the TMRT. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 19, 073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H.G.; Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Tong, H.; Huang, Z.P.; Zhao, R.S. Pulse Profile Variations Associated with the Glitch of PSR B2021+51. Astrophys. J. 2021, 912, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damour, T.; Taylor, J.H. Strong–Field Tests of Relativistic Gravity and Binary Pulsars. Phys. Rev. D 1992, 45, 1840–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.; Xu, R.X.; Song, L.M.; Qiao, G.J. Wind Braking of Magnetars. Astrophys. J. 2013, 768, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.F.; Li, X.D.; Wang, N.; Yuan, J.P.; Wang, P.; Peng, Q.H.; Du, Y.J. Constraining the braking indices of magnetars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2016, 456, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olausen, S.A.; Kaspi, V.M. The McGill Magnetar Catalog. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2014, 212, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppusamy, R.; Stappers, B.W.; Serylak, M. A low frequency study of PSRs B1133+16, B1112+50, and B0031-07. Astron. Astrophys. 2011, 525, A55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoto, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Younes, G.; Hu, C.P.; Ho, W.C.G.; Gendreau, K.; Arzoumanian, Z.; Guver, T.; Guillot, S.; Altamirano, D.; et al. NICER detection of 1.36 sec periodicity from a new magnetar, Swift J1818.0-1607. Astron. Telegr. 2020, 13551, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, P.; Rea, N.; Borghese, A.; Coti Zelati, F.; Viganò, D.; Israel, G.L.; Tiengo, A.; Ridolfi, A.; Possenti, A.; Burgay, M.; et al. A Very Young Radio-loud Magnetar. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2020, 896, L30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, D.; Cognard, I.; Cruces, M.; Desvignes, G.; Jankowski, F.; Karuppusamy, R.; Keith, M.J.; Kouveliotou, C.; Kramer, M.; Liu, K.; et al. High-cadence observations and variable spin behaviour of magnetar Swift J1818.0-1607 after its outburst. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2020, 498, 6044–6056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.P.; Strohmayer, T.E.; Ray, P.S.; Enoto, T.; Guver, T.; Guillot, S.; Jaisawal, G.K.; Younes, G.; Gendreau, K.; Arzoumanian, Z.; et al. NICER follow-up observation and a candidate timing anomaly from Swift J1818.0-1607. Astron. Telegr. 2020, 13588, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.P.; Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Tong, H.; Lin, L.; Yuan, J.P.; Liu, J.; Zhao, R.S.; Ge, M.Y.; Wang, R. Simultaneous 2.25/8.60 GHz observations of the newly discovered magnetar-Swift J1818.0-1607. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 505, 1311–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotthelf, E.V.; Halpern, J.P.; Alford, J.A.J.; Mihara, T.; Negoro, H.; Kawai, N.; Dai, S.; Lower, M.E.; Johnston, S.; Bailes, M.; et al. The 2018 X-Ray and Radio Outburst of Magnetar XTE J1810-197. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2019, 874, L25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.; Lyne, A.G.; Desvignes, G.; Eatough, R.P.; Karuppusamy, R.; Kramer, M.; Mickaliger, M.; Stappers, B.W.; Weltevrede, P. Spin frequency evolution and pulse profile variations of the recently re-activated radio magnetar XTE J1810-197. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2019, 488, 5251–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.P.; Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Tong, H.; Yuan, J.P.; Lin, L.; Zhao, R.B.; Wu, Y.J.; Liu, J.; Wang, R.; et al. Simultaneous 2.25/8.60 GHz Observations of the Magnetar XTE J1810-197. Astrophys. J. 2023, 956, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, J.M. Toward an empirical theory of pulsar emission. VI. The geometry of the conal emission region. Astrophys. J. 1993, 405, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyne, A.G.; Manchester, R.N. The shape of pulsar radio beams. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1988, 234, 477–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.G.; Pi, F.P.; Zheng, X.P.; Deng, C.L.; Wen, S.Q.; Ye, F.; Guan, K.Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.Q. A Fan Beam Model for Radio Pulsars. I. Observational Evidence. Astrophys. J. 2014, 789, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, J.M. Toward an Empirical Theory of Pulsar Emission. III. Mode Changing, Drifting Subpulses, and Pulse Nulling. Astrophys. J. 1986, 301, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.S.; Wu, X.J.; Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Manchester, R.N.; Qiao, G.J.; Xu, R.X.; Wu, Y.J.; Zhao, R.B.; Li, B.; et al. TMRT Observations of 26 Pulsars at 8.6 GHz. Astrophys. J. 2017, 845, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.S.; Yan, Z.; Wu, X.J.; Shen, Z.Q.; Manchester, R.N.; Liu, J.; Qiao, G.J.; Xu, R.X.; Lee, K.J. 5.0 GHz TMRT Observations of 71 Pulsars. Astrophys. J. 2019, 874, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, O.; Serylak, M.; Kijak, J.; Krzeszowski, K.; Mitra, D.; Jessner, A. Pulse-to-pulse flux density modulation from pulsars at 8.35 GHz. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 555, A28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, H.; Huang, Y.X.; Burgay, M.; Champion, D.; Cognard, I.; Guillemot, L.; Jang, J.; Karuppusamy, R.; Kramer, M.; Lackeos, K.; et al. A sustained pulse shape change in PSR J1713+0747 possibly associated with timing and DM events. Astron. Telegr. 2021, 14642, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.W.; Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Tong, H.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, R.B.; Wu, Y.J.; Huang, Z.P.; Wang, R.; Liu, J. Observations of nine millisecond pulsars at 8600 MHz using the TMRT. Astrophys. J. 2023, 961, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.G.; Du, Y.J.; Hao, L.F.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Z.Y.; Lee, K.J.; Qiao, G.J.; Shang, L.H.; Wang, M.; Xu, R.X.; et al. Multi-frequency Radio Profiles of PSR B1133+16: Radiation Location and Particle Energy. Astrophys. J. 2016, 816, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.H.; Xu, X.; Dang, S.J.; Zhi, Q.J.; Bai, J.T.; Zhu, R.H.; Lin, Q.W.; Yang, H. A Simulation of Radius-frequency Mapping for PSR J1848-0123 with an Inverse Compton Scattering Model. Astrophys. J. 2021, 916, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltevrede, P.; Wright, G.A.E.; Stappers, B.W.; Rankin, J.M. The bright spiky emission of pulsar B0656+14. Astron. Astrophys. 2006, 458, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Manchester, R.N.; Ng, C.Y.; Weltevrede, P.; Wang, H.G.; Wu, X.J.; Yuan, J.P.; Wu, Y.J.; Zhao, R.B.; et al. Simultaneous 13 cm/3 cm Single-pulse Observations of PSR B0329+54. Astrophys. J. 2018, 856, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.G.; Yuen, R.; Wang, N.; Tu, Z.Y.; Yan, Z.; Yuan, J.P.; Yan, W.M.; Chen, J.L.; Wang, H.G.; Shen, Z.Q.; et al. Observations of Bright Pulses from Pulsar B0031-07 at 4.82 GHz. Astrophys. J. 2021, 918, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stinebring, D.R.; Smirnova, T.V.; Hankins, T.H.; Hovis, J.S.; Kaspi, V.M.; Kempner, J.C.; Myers, E.; Nice, D.J. Five Years of Pulsar Flux Density Monitoring: Refractive Scintillation and the Interstellar Medium. Astrophys. J. 2000, 539, 300–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuer, P.A.G. Amplitude variations of pulsed radio sources. Nature 1968, 218, 920–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickett, B.J. Frequency structure of pulsar intensity fluctuations. Nature 1969, 221, 158–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.; Lyne, A.G.; Peckham, R.J. Proper Motions of Six Pulsars. Nature 1975, 258, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouw, W.N.; Spoelstra, T.A.T. Linear polarization of the galactic background at frequencies between 408 and 1411 MHz. Reductions. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 1976, 26, 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bartel, N.; Ratner, M.I.; Shapiro, I.I.; Cappallo, R.J.; Rogers, A.E.E.; Whitney, A.R. Pulsar Astrometry via VLBI. Astron. J. 1985, 90, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomalont, E.B.; Goss, W.M.; Beasley, A.J.; Chatterjee, S. Sub-Milliarcsecond Precision of Pulsar Motions: Using In-Beam Calibrators with the VLBA. Astron. J. 1999, 117, 3025–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brisken, W.F.; Benson, J.M.; Goss, W.M.; Thorsett, S.E. Very Long Baseline Array Measurement of Nine Pulsar Parallaxes. Astrophys. J. 2002, 571, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, A.T.; Tingay, S.J.; Bailes, M.; West, C. DiFX: A Software Correlator for Very Long Baseline Interferometry Using Multiprocessor Computing Environments. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2007, 119, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.Q.; Yuan, J.P.; Wang, N.; Rottmann, H.; Alef, W. Very long baseline interferometry astrometry of PSR B1257+12, a pulsar with a planetary system. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 433, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, Z.; Shen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, R.; Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Wang, R.; Wang, X.; Liu, Q.; Li, B.; et al. Shanghai Tianma Radio Telescope and Its Role in Pulsar Astronomy. Universe 2024, 10, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe10050195

Yan Z, Shen Z, Wu Y, Zhao R, Liu J, Huang Z, Wang R, Wang X, Liu Q, Li B, et al. Shanghai Tianma Radio Telescope and Its Role in Pulsar Astronomy. Universe. 2024; 10(5):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe10050195

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Zhen, Zhiqiang Shen, Yajun Wu, Rongbing Zhao, Jie Liu, Zhipeng Huang, Rui Wang, Xiaowei Wang, Qinghui Liu, Bin Li, and et al. 2024. "Shanghai Tianma Radio Telescope and Its Role in Pulsar Astronomy" Universe 10, no. 5: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe10050195

APA StyleYan, Z., Shen, Z., Wu, Y., Zhao, R., Liu, J., Huang, Z., Wang, R., Wang, X., Liu, Q., Li, B., Wang, J., Zhong, W., Jiang, W., & Xia, B. (2024). Shanghai Tianma Radio Telescope and Its Role in Pulsar Astronomy. Universe, 10(5), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/universe10050195