Molecular Chaperones: Molecular Assembly Line Brings Metabolism and Immunity in Shape

Abstract

:1. Introduction

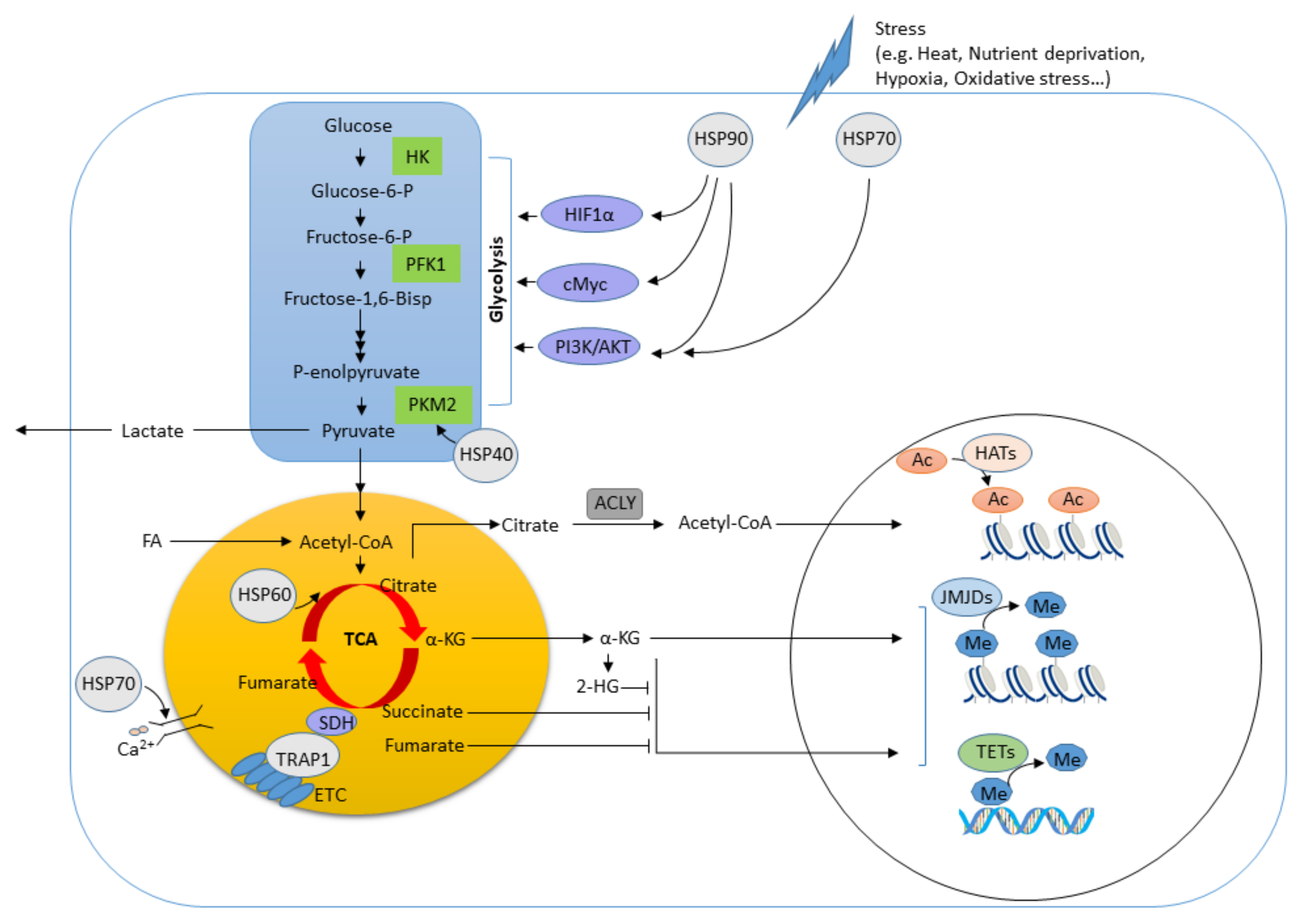

2. Overview of Molecular Chaperones

3. Roles of Molecular Chaperones in Metabolism and Immune Function

3.1. HSP90

3.2. HSP70

3.3. HSP60

3.4. HSP40

3.5. Small HSPs

3.6. Extracellular HSPs

4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, Y.E.; Hipp, M.S.; Bracher, A.; Hayer-Hartl, M.; Hartl, F.U. Molecular chaperone functions in protein folding and proteostasis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 323–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartl, F.U.; Bracher, A.; Hayer-Hartl, M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature 2011, 475, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, B.; Pockley, A.G. Molecular chaperones and protein-folding catalysts as intercellular signaling regulators in immunity and inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2010, 88, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vabulas, R.M.; Wagner, H.; Schild, H. Heat shock proteins as ligands of toll-like receptors. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2002, 270, 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Zininga, T.; Ramatsui, L.; Shonhai, A. Heat Shock Proteins as Immunomodulants. Molecules 2018, 23, 2846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ganeshan, K.; Chawla, A. Metabolic regulation of immune responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 32, 609–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Neill, L.A.; Pearce, E.J. Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. J. Exp. Med. 2016, 213, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Dikshit, M. Metabolic Insight of Neutrophils in Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftus, R.M.; Finlay, D.K. Immunometabolism: Cellular Metabolism Turns Immune Regulator. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zasłona, Z.; O’Neill, L.A.J. Cytokine-like Roles for Metabolites in Immunity. Mol. Cell. 2020, 78, 814–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lio, C.J.; Ching-Cheng Huang, S. Circles of Life: Linking metabolic and epigenetic cycles to immunity. Immunology 2020, 16, 13207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabinsky, R.A.; Mason, G.A.; Queitsch, C.; Jarosz, D.F. It’s not magic-Hsp90 and its effects on genetic and epigenetic variation. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 88, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacs, J.S. Hsp90 as a "Chaperone" of the Epigenome: Insights and Opportunities for Cancer Therapy. Adv. Cancer Res. 2016, 129, 107–140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Etchegaray, J.P.; Mostoslavsky, R. Interplay between Metabolism and Epigenetics: A Nuclear Adaptation to Environmental Changes. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reid, M.A.; Dai, Z.; Locasale, J.W. The impact of cellular metabolism on chromatin dynamics and epigenetics. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritossa, F. A new puffing pattern induced by temperature shock and DNP in drosophila. Experientia 1962, 18, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tissiéres, A.; Mitchell, H.K.; Tracy, U.M. Protein synthesis in salivary glands of Drosophila melanogaster: Relation to chromosome puffs. J. Mol. Biol. 1974, 84, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M. Patterns of puffing activity in the salivary gland chromosomes of Drosophila. Chromosoma 1970, 31, 356–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthan, J.; Goldberg, A.; Voellmy, R. Abnormal proteins serve as eukaryotic stress signals and trigger the activation of heat shock genes. Science 1986, 232, 522–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmingsen, S.M.; Woolford, C.; van der Vies, S.M.; Tilly, K.; Dennis, D.T.; Georgopoulos, C.P.; Hendrix, R.W.; Ellis, R.J. Homologous plant and bacterial proteins chaperone oligomeric protein assembly. Nature 1988, 333, 330–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampinga, H.H.; Hageman, J.; Vos, M.J.; Kubota, H.; Tanguay, R.M.; Bruford, E.A.; Cheetham, M.E.; Chen, B.; Hightower, L.E. Guidelines for the nomenclature of the human heat shock proteins. Cell Stress Chaperones 2009, 14, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vabulas, R.M.; Raychaudhuri, S.; Hayer-Hartl, M.; Hartl, F.U. Protein folding in the cytoplasm and the heat shock response. Cold Spring Harb Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorger, P.K. Heat shock factor and the heat shock response. Cell 1991, 65, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, M.; Nakai, A. The heat shock factor family and adaptation to proteotoxic stress. FEBS J. 2010, 277, 4112–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Guo, Y.; Guettouche, T.; Smith, D.F.; Voellmy, R. Repression of Heat Shock Transcription Factor HSF1 Activation by HSP90 (HSP90 Complex) that Forms a Stress-Sensitive Complex with HSF1. Cell 1998, 94, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vabulas, R.M.; Ahmad-Nejad, P.; da Costa, C.; Miethke, T.; Kirschning, C.J.; Hacker, H.; Wagner, H. Endocytosed HSP60s use toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) and TLR4 to activate the toll/interleukin-1 receptor signaling pathway in innate immune cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 31332–31339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asea, A.; Rehli, M.; Kabingu, E.; Boch, J.A.; Bare, O.; Auron, P.E.; Stevenson, M.A.; Calderwood, S.K. Novel signal transduction pathway utilized by extracellular HSP70: Role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 15028–15034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franco, L.H.; Wowk, P.F.; Silva, C.L.; Trombone, A.P.F.; Coelho-Castelo, A.A.M.; Oliver, C.; Jamur, M.C.; Moretto, E.L.; Bonato, V.L.D. A DNA vaccine against tuberculosis based on the 65 kDa heat-shock protein differentially activates human macrophages and dendritic cells. Genet. Vaccines Ther. 2008, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, M.; Zhao, H.; Li, M.; Yue, Y.; Xiong, S.; Xu, W. Intranasal Vaccination with Mannosylated Chitosan Formulated DNA Vaccine Enables Robust IgA and Cellular Response Induction in the Lungs of Mice and Improves Protection against Pulmonary Mycobacterial Challenge. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, R.J. Heat-shock protein-based vaccines for cancer and infectious disease. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2008, 7, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, R.J.; Han, D.K.; Srivastava, P.K. CD91: A receptor for heat shock protein gp96. Nat. Immunol. 2000, 1, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, M.D.; Sowell, R.T.; Kaech, S.M.; Pearce, E.L. Metabolic Instruction of Immunity. Cell 2017, 169, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Raines, L.N.; Huang, S.C.-C. Carbohydrate and Amino Acid Metabolism as Hallmarks for Innate Immune Cell Activation and Function. Cells 2020, 9, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Philip, M.; Fairchild, L.; Sun, L.; Horste, E.L.; Camara, S.; Shakiba, M.; Scott, A.C.; Viale, A.; Lauer, P.; Merghoub, T.; et al. Chromatin states define tumour-specific T cell dysfunction and reprogramming. Nature 2017, 545, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, T.; Takeuchi, O.; Vandenbon, A.; Yasuda, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Kumagai, Y.; Miyake, T.; Matsushita, K.; Okazaki, T.; Saitoh, T.; et al. The Jmjd3-Irf4 axis regulates M2 macrophage polarization and host responses against helminth infection. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 936–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Mitochondrial TCA cycle metabolites control physiology and disease. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franco, F.; Jaccard, A.; Romero, P.; Yu, Y.-R.; Ho, P.-C. Metabolic and epigenetic regulation of T-cell exhaustion. Nat. Metab. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baardman, J.; Licht, I.; de Winther, M.P.; Van den Bossche, J. Metabolic-epigenetic crosstalk in macrophage activation. Epigenomics 2015, 7, 1155–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Phan, A.T.; Goldrath, A.W.; Glass, C.K. Metabolic and Epigenetic Coordination of T Cell and Macrophage Immunity. Immunity 2017, 46, 714–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoter, A.; El-Sabban, M.E.; Naim, H.Y. The HSP90 Family: Structure, Regulation, Function, and Implications in Health and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prodromou, C. Mechanisms of Hsp90 regulation. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 2439–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jackson, S.E. Hsp90: Structure and Function. In Molecular Chaperones; Jackson, S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 155–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schopf, F.H.; Biebl, M.M.; Buchner, J. The HSP90 chaperone machinery. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratt, W.B.; Toft, D.O. Regulation of Signaling Protein Function and Trafficking by the hsp90/hsp70-Based Chaperone Machinery. Exp. Biol. Med. 2003, 228, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsan, M.F.; Gao, B. Heat shock proteins and immune system. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2009, 85, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oura, J.; Tamura, Y.; Kamiguchi, K.; Kutomi, G.; Sahara, H.; Torigoe, T.; Himi, T.; Sato, N. Extracellular heat shock protein 90 plays a role in translocating chaperoned antigen from endosome to proteasome for generating antigenic peptide to be cross-presented by dendritic cells. Int. Immunol. 2011, 23, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Imai, T.; Kato, Y.; Kajiwara, C.; Mizukami, S.; Ishige, I.; Ichiyanagi, T.; Hikida, M.; Wang, J.Y.; Udono, H. Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) contributes to cytosolic translocation of extracellular antigen for cross-presentation by dendritic cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 16363–16368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basu, S.; Srivastava, P.K. Fever-like temperature induces maturation of dendritic cells through induction of hsp90. Int. Immunol. 2003, 15, 1053–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graner, M.W. HSP90 and Immune Modulation in Cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2016, 129, 191–224. [Google Scholar]

- Multhoff, G.; Pockley, A.G.; Streffer, C.; Gaipl, U.S. Dual role of heat shock proteins (HSPs) in anti-tumor immunity. Curr. Mol. Med. 2012, 12, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, A.J.; Mandal, A.K.; Theodoraki, M.A. Molecular chaperones and protein kinase quality control. Trends Cell Biol. 2007, 17, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Buchner, J. Structure, function and regulation of the hsp90 machinery. Biomed. J. 2013, 36, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ambade, A.; Catalano, D.; Lim, A.; Mandrekar, P. Inhibition of heat shock protein (molecular weight 90 kDa) attenuates proinflammatory cytokines and prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lazaro, I.; Oguiza, A.; Recio, C.; Lopez-Sanz, L.; Bernal, S.; Egido, J.; Gomez-Guerrero, C. Interplay between HSP90 and Nrf2 pathways in diabetes-associated atherosclerosis. Clin. Investig. Arter. 2017, 29, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Xu, G.; Zhan, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fu, S.; Qin, N.; Hou, X.; Ai, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Carnosol inhibits inflammasome activation by directly targeting HSP90 to treat inflammasome-mediated diseases. Cell Death. Dis. 2020, 11, 2020–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choudhury, A.; Bullock, D.; Lim, A.; Argemi, J.; Orning, P.; Lien, E.; Bataller, R.; Mandrekar, P. Inhibition of HSP90 and activation of HSF1 diminishes macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome activity in alcoholic liver injury. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 13, 14338. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, R.; Marchenko, N.D.; Holembowski, L.; Fingerle-Rowson, G.; Pesic, M.; Zender, L.; Dobbelstein, M.; Moll, U.M. Inhibiting the HSP90 chaperone destabilizes macrophage migration inhibitory factor and thereby inhibits breast tumor progression. J. Exp. Med. 2012, 209, 275–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.H.; Oh, S.J.; Kim, S.; Cho, H.; Lee, H.J.; Song, J.S.; Chung, J.Y.; Cho, E.; Lee, J.; Jeon, S.; et al. HSP90A inhibition promotes anti-tumor immunity by reversing multi-modal resistance and stem-like property of immune-refractory tumors. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 14019–14259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, Y.C.; Angelin, A.; Lisanti, S.; Kossenkov, A.V.; Speicher, K.D.; Wang, H.; Powers, J.F.; Tischler, A.S.; Pacak, K.; Fliedner, S.; et al. Landscape of the mitochondrial Hsp90 metabolome in tumours. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Yi, Y.; Guo, Q.; Sun, Y.; Ma, S.; Xiao, S.; Geng, J.; Zheng, Z.; Song, S. Hsp90 interacts with AMPK and mediates acetyl-CoA carboxylase phosphorylation. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 859–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Tu, J.; Dou, C.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Lei, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; et al. HSP90 promotes cell glycolysis, proliferation and inhibits apoptosis by regulating PKM2 abundance via Thr-328 phosphorylation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 017–0748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycielska, M.E.; Moser, C.; Wagner, C.; Scheiffert, E.; Geissler, E.K.; Schlitt, H.J.; Lang, S.A. Abstract 3211: Inhibition of Hsp90 impairs expression of VDAC in plasma and mitochondrial membrane influencing cancer cell metabolism. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.Q.; Liu, Q.H.; Chen, X.; Yang, Q.; Xu, Z.Y.; Hu, F.; Wang, L.; Li, J.M. Hsp90 inhibitor 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldanamycin inhibits the proliferation of ARPE-19 cells. J. Biomed. Sci. 2010, 17, 1423–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dang, C.V. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 2012, 149, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, R.; Dillon, C.P.; Shi, L.Z.; Milasta, S.; Carter, R.; Finkelstein, D.; McCormick, L.L.; Fitzgerald, P.; Chi, H.; Munger, J.; et al. The transcription factor Myc controls metabolic reprogramming upon T lymphocyte activation. Immunity 2011, 35, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paul, I.; Ahmed, S.F.; Bhowmik, A.; Deb, S.; Ghosh, M.K. The ubiquitin ligase CHIP regulates c-Myc stability and transcriptional activity. Oncogene 2013, 32, 1284–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Regan, P.L.; Jacobs, J.; Wang, G.; Torres, J.; Edo, R.; Friedmann, J.; Tang, X.X. Hsp90 inhibition increases p53 expression and destabilizes MYCN and MYC in neuroblastoma. Int J. Oncol. 2011, 38, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minet, E.; Mottet, D.; Michel, G.; Roland, I.; Raes, M.; Remacle, J.; Michiels, C. Hypoxia-induced activation of HIF-1: Role of HIF-1alpha-Hsp90 interaction. FEBS Lett. 1999, 460, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.W.; Kao, J.K.; Wu, C.Y.; Wang, S.T.; Lee, H.C.; Liang, S.M.; Chen, Y.J.; Shieh, J.J. Targeting aerobic glycolysis and HIF-1alpha expression enhance imiquimod-induced apoptosis in cancer cells. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 1363–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Corcoran, S.E.; O’Neill, L.A. HIF1α and metabolic reprogramming in inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 3699–3707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Liu, H.; Lian, G.; Zhang, S.Y.; Wang, X.; Jiang, C. HIF1α-Induced Glycolysis Metabolism Is Essential to the Activation of Inflammatory Macrophages. Mediat. Inflamm. 2017, 9029327, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantsch, J.; Chakravortty, D.; Turza, N.; Prechtel, A.T.; Buchholz, B.; Gerlach, R.G.; Volke, M.; Gläsner, J.; Warnecke, C.; Wiesener, M.S.; et al. Hypoxia and Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1α Modulate Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Dendritic Cell Activation and Function. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 4697–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redlak, M.J.; Miller, T.A. Targeting PI3K/Akt/HSP90 signaling sensitizes gastric cancer cells to deoxycholate-induced apoptosis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2011, 56, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frauwirth, K.A.; Riley, J.L.; Harris, M.H.; Parry, R.V.; Rathmell, J.C.; Plas, D.R.; Elstrom, R.L.; June, C.H.; Thompson, C.B. The CD28 Signaling Pathway Regulates Glucose Metabolism. Immunity 2002, 16, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, W.; Hu, H.; Chang, R.; Zhong, J.; Knabel, M.; O’Meally, R.; Cole, R.N.; Pandey, A.; Semenza, G.L. Pyruvate kinase M2 is a PHD3-stimulated coactivator for hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell 2011, 145, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Palsson-McDermott, E.M.; Curtis, A.M.; Goel, G.; Lauterbach, M.A.; Sheedy, F.J.; Gleeson, L.E.; van den Bosch, M.W.; Quinn, S.R.; Domingo-Fernandez, R.; Johnston, D.G.; et al. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates Hif-1α activity and IL-1β induction and is a critical determinant of the warburg effect in LPS-activated macrophages. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Angiari, S.; Runtsch, M.C.; Sutton, C.E.; Palsson-McDermott, E.M.; Kelly, B.; Rana, N.; Kane, H.; Papadopoulou, G.; Pearce, E.L.; Mills, K.H.G.; et al. Pharmacological Activation of Pyruvate Kinase M2 Inhibits CD4(+) T Cell Pathogenicity and Suppresses Autoimmunity. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 391–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, W.; Wang, F.; Yu, Z.; Xin, F. Epigenetics and Cellular Metabolism. Genet. Epigenet. 2016, 8, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, W.; Xia, Y.; Hawke, D.; Li, X.; Liang, J.; Xing, D.; Aldape, K.; Hunter, T.; Alfred Yung, W.K.; Lu, Z. PKM2 phosphorylates histone H3 and promotes gene transcription and tumorigenesis. Cell 2012, 150, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, X.; Wang, H.; Yang, J.J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.R. Pyruvate kinase M2 regulates gene transcription by acting as a protein kinase. Mol. Cell 2012, 45, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Raghavan, A.; Nandiwada, S.L.; Curtsinger, J.M.; Bohjanen, P.R.; Mueller, D.L.; Mescher, M.F. Gene regulation and chromatin remodeling by IL-12 and type I IFN in programming for CD8 T cell effector function and memory. J. Immunol. 2009, 183, 1695–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Araki, Y.; Fann, M.; Wersto, R.; Weng, N.P. Histone acetylation facilitates rapid and robust memory CD8 T cell response through differential expression of effector molecules (eomesodermin and its targets: Perforin and granzyme B). J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 8102–8108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masgras, I.; Sanchez-Martin, C.; Colombo, G.; Rasola, A. The Chaperone TRAP1 As a Modulator of the Mitochondrial Adaptations in Cancer Cells. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matassa, D.S.; Agliarulo, I.; Avolio, R.; Landriscina, M.; Esposito, F. TRAP1 Regulation of Cancer Metabolism: Dual Role as Oncogene or Tumor Suppressor. Genes 2018, 9, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Im, C.N. Past, present, and emerging roles of mitochondrial heat shock protein TRAP1 in the metabolism and regulation of cancer stem cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joshi, A.; Dai, L.; Liu, Y.; Lee, J.; Ghahhari, N.M.; Segala, G.; Beebe, K.; Jenkins, L.M.; Lyons, G.C.; Bernasconi, L.; et al. The mitochondrial HSP90 paralog TRAP1 forms an OXPHOS-regulated tetramer and is involved in mitochondrial metabolic homeostasis. BMC Biol. 2020, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sciacovelli, M.; Guzzo, G.; Morello, V.; Frezza, C.; Zheng, L.; Nannini, N.; Calabrese, F.; Laudiero, G.; Esposito, F.; Landriscina, M.; et al. The Mitochondrial Chaperone TRAP1 Promotes Neoplastic Growth by Inhibiting Succinate Dehydrogenase. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoshida, S.; Tsutsumi, S.; Muhlebach, G.; Sourbier, C.; Lee, M.-J.; Lee, S.; Vartholomaiou, E.; Tatokoro, M.; Beebe, K.; Miyajima, N.; et al. Molecular chaperone TRAP1 regulates a metabolic switch between mitochondrial respiration and aerobic glycolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E1604–E1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daugaard, M.; Rohde, M.; Jäättelä, M. The heat shock protein 70 family: Highly homologous proteins with overlapping and distinct functions. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 3702–3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenzweig, R.; Nillegoda, N.B.; Mayer, M.P.; Bukau, B. The Hsp70 chaperone network. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 665–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, M.R.; Valpuesta, J.M. Hsp70 chaperone: A master player in protein homeostasis. F1000Research 1000, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hightower, L.E.; Guidon, P.T., Jr. Selective release from cultured mammalian cells of heat-shock (stress) proteins that resemble glia-axon transfer proteins. J. Cell Physiol. 1989, 138, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vabulas, R.M.; Ahmad-Nejad, P.; Ghose, S.; Kirschning, C.J.; Issels, R.D.; Wagner, H. HSP70 as endogenous stimulus of the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor signal pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 15107–15112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, R.; Town, T.; Gokarn, V.; Flavell, R.A.; Chandawarkar, R.Y. HSP70 enhances macrophage phagocytosis by interaction with lipid raft-associated TLR-7 and upregulating p38 MAPK and PI3K pathways. J. Surg Res. 2006, 136, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, T.J.; Lopes, R.L.; Pinho, N.G.; Machado, F.D.; Souza, A.P.; Bonorino, C. Extracellular Hsp70 inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine production by IL-10 driven down-regulation of C/EBPbeta and C/EBPdelta. Int. J. Hyperth. 2013, 29, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocki, P.; Wang, X.N.; Dickinson, A.M. Inducible heat shock protein 70 reduces T cell responses and stimulatory capacity of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 12387–12394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Detanico, T.; Rodrigues, L.; Sabritto, A.C.; Keisermann, M.; Bauer, M.E.; Zwickey, H.; Bonorino, C. Mycobacterial heat shock protein 70 induces interleukin-10 production: Immunomodulation of synovial cell cytokine profile and dendritic cell maturation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2004, 135, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, S.; Ambade, A.; Fulham, M.A.; Deshpande, J.; Catalano, D.; Mandrekar, P. Moderate alcohol induces stress proteins HSF1 and hsp70 and inhibits proinflammatory cytokines resulting in endotoxin tolerance. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 1975–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schildkopf, P.; Frey, B.; Ott, O.J.; Rubner, Y.; Multhoff, G.; Sauer, R.; Fietkau, R.; Gaipl, U.S. Radiation combined with hyperthermia induces HSP70-dependent maturation of dendritic cells and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines by dendritic cells and macrophages. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 2011, 101, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padwad, Y.S.; Mishra, K.P.; Jain, M.; Chanda, S.; Ganju, L. Dengue virus infection activates cellular chaperone Hsp70 in THP-1 cells: Downregulation of Hsp70 by siRNA revealed decreased viral replication. Viral Immunol. 2010, 23, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, L.; Luo, L.; Xue, B.; Lu, C.; Zhang, X.; Yin, Z. Hsp70 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-kappaB activation by interacting with TRAF6 and inhibiting its ubiquitination. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 3145–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ding, X.Z.; Fernandez-Prada, C.M.; Bhattacharjee, A.K.; Hoover, D.L. Over-expression of hsp-70 inhibits bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced production of cytokines in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Cytokine 2001, 16, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brykczynska, U.; Geigges, M.; Wiedemann, S.J.; Dror, E.; Boni-Schnetzler, M.; Hess, C.; Donath, M.Y.; Paro, R. Distinct Transcriptional Responses across Tissue-Resident Macrophages to Short-Term and Long-Term Metabolic Challenge. Cell Rep. 2020, 30, 1627–1643.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, J.; Nguyen, A.K.; Henstridge, D.C.; Holmes, A.G.; Chan, M.H.; Mesa, J.L.; Lancaster, G.I.; Southgate, R.J.; Bruce, C.R.; Duffy, S.J.; et al. HSP72 protects against obesity-induced insulin resistance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 1739–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henstridge, D.C.; Whitham, M.; Febbraio, M.A. Chaperoning to the metabolic party: The emerging therapeutic role of heat-shock proteins in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Literati-Nagy, B.; Kulcsar, E.; Literati-Nagy, Z.; Buday, B.; Peterfai, E.; Horvath, T.; Tory, K.; Kolonics, A.; Fleming, A.; Mandl, J.; et al. Improvement of insulin sensitivity by a novel drug, BGP-15, in insulin-resistant patients: A proof of concept randomized double-blind clinical trial. Horm. Metab. Res. 2009, 41, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asea, A.; Kraeft, S.-K.; Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Stevenson, M.A.; Chen, L.B.; Finberg, R.W.; Koo, G.C.; Calderwood, S.K. HSP70 stimulates cytokine production through a CD14-dependant pathway, demonstrating its dual role as a chaperone and cytokine. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.K.; Anand, E.; Bleck, C.K.; Anes, E.; Griffiths, G. Exosomal Hsp70 induces a pro-inflammatory response to foreign particles including mycobacteria. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, 0010136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noessner, E.; Gastpar, R.; Milani, V.; Brandl, A.; Hutzler, P.J.S.; Kuppner, M.C.; Roos, M.; Kremmer, E.; Asea, A.; Calderwood, S.K.; et al. Tumor-Derived Heat Shock Protein 70 Peptide Complexes Are Cross-Presented by Human Dendritic Cells. J. Immunol. 2002, 169, 5424–5432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Millar, D.G.; Garza, K.M.; Odermatt, B.; Elford, A.R.; Ono, N.; Li, Z.; Ohashi, P.S. Hsp70 promotes antigen-presenting cell function and converts T-cell tolerance to autoimmunity in vivo. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaglom, J.A.; Gabai, V.L.; Sherman, M.Y. High levels of heat shock protein Hsp72 in cancer cells suppress default senescence pathways. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 2373–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Multhoff, G.; Pfister, K.; Gehrmann, M.; Hantschel, M.; Gross, C.; Hafner, M.; Hiddemann, W. A 14-mer Hsp70 peptide stimulates natural killer (NK) cell activity. Cell Stress Chaperones 2001, 6, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, C.; Schmidt-Wolf, I.G.; Nagaraj, S.; Gastpar, R.; Ellwart, J.; Kunz-Schughart, L.A.; Multhoff, G. Heat shock protein 70-reactivity is associated with increased cell surface density of CD94/CD56 on primary natural killer cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 2003, 8, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, C.; Koelch, W.; DeMaio, A.; Arispe, N.; Multhoff, G. Cell surface-bound heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) mediates perforin-independent apoptosis by specific binding and uptake of granzyme B. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 41173–41181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodd, K.; Nance, S.; Quezada, M.; Janke, L.; Morrison, J.B.; Williams, R.T.; Beere, H.M. Tumor-derived inducible heat-shock protein 70 (HSP70) is an essential component of anti-tumor immunity. Oncogene 2015, 34, 1312–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wachstein, J.; Tischer, S.; Figueiredo, C.; Limbourg, A.; Falk, C.; Immenschuh, S.; Blasczyk, R.; Eiz-Vesper, B. HSP70 enhances immunosuppressive function of CD4(+)CD25(+)FoxP3(+) T regulatory cells and cytotoxicity in CD4(+)CD25(-) T cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kottke, T.; Sanchez-Perez, L.; Diaz, R.M.; Thompson, J.; Chong, H.; Harrington, K.; Calderwood, S.K.; Pulido, J.; Georgopoulos, N.; Selby, P.; et al. Induction of hsp70-mediated Th17 autoimmunity can be exploited as immunotherapy for metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 11970–11979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dang, E.V.; Barbi, J.; Yang, H.-Y.; Jinasena, D.; Yu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Bordman, Z.; Fu, J.; Kim, Y.; Yen, H.-R.; et al. Control of TH17/Treg Balance by Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1. Cell 2011, 146, 772–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Ni, L.; Wan, S.; Zhao, X.; Ding, X.; Dejean, A.; Dong, C. Febrile Temperature Critically Controls the Differentiation and Pathogenicity of T Helper 17 Cells. Immunity 2020, 52, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cwiklinska, H.; Cichalewska-Studzinska, M.; Selmaj, K.W.; Mycko, M.P. The Heat Shock Protein HSP70 Promotes Th17 Genes’ Expression via Specific Regulation of microRNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2823. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, A.; He, K.; Liu, P.; Xu, L.X. Cryo-thermal therapy elicits potent anti-tumor immunity by inducing extracellular Hsp70-dependent MDSC differentiation. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Schumann, U.; Liu, Y.; Prokopchuk, O.; Steinacker, J.M. Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) inhibits oxidative phosphorylation and compensates ATP balance through enhanced glycolytic activity. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985, 113, 1669–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, H.; Yao, R.; Lian, S.; Liu, P.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.Y.; Yang, H.; Li, S. Regulating glycolysis, the TLR4 signal pathway and expression of RBM3 in mouse liver in response to acute cold exposure. Stress 2019, 22, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kong, Q.; Li, N.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Cao, X.; Qi, T.; Dai, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; et al. HSPA12A Is a Novel Player in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis via Promoting Nuclear PKM2-Mediated M1 Macrophage Polarization. Diabetes 2019, 68, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, L.; Hasin, N.; Cuskelly, D.D.; Wolfgeher, D.; Doyle, S.; Moynagh, P.; Perrett, S.; Jones, G.W.; Truman, A.W. Rapid deacetylation of yeast Hsp70 mediates the cellular response to heat stress. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ouyang, Y.-B.; Giffard, R.G. ER-Mitochondria Crosstalk during Cerebral Ischemia: Molecular Chaperones and ER-Mitochondrial Calcium Transfer. Int. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 2012, 493934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayat, B.; Kapuganti, R.S.; Padhy, B.; Mohanty, P.P.; Alone, D.P. Epigenetic silencing of heat shock protein 70 through DNA hypermethylation in pseudoexfoliation syndrome and glaucoma. J. Hum. Genet. 2020, 65, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappello, F.; Conway de Macario, E.; Marasà, L.; Zummo, G.; Macario, A.J.L. Hsp60 expression, new locations, functions, and perspectives for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008, 7, 801–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso Bavisotto, C.; Scalia, F.; Pitruzzella, A.; Górska-Ponikowska, M.; Marino, C.; Taglialatela, G. Hsp60 in Modifications of Nervous System Homeostasis and Neurodegeneration. In Heat Shock Protein 60 in Human Diseases and Disorders; Asea, A.A.A., Kaur, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 241–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, L.; Martinus, R.D. Hyperglycaemia and oxidative stress upregulate HSP60 & HSP70 expression in HeLa cells. Springerplus 2013, 2, 1801–2193. [Google Scholar]

- Martinus, R.D.; Goldsbury, J. Endothelial TNF-α induction by Hsp60 secreted from THP-1 monocytes exposed to hyperglycaemic conditions. Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanagamage, D.; Martinus, R.D. Role of Mitochondrial Stress Protein HSP60 in Diabetes-Induced Neuroinflammation. Mediat. Inflamm. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Syldath, U.; Bellmann, K.; Burkart, V.; Kolb, H. Human 60-kDa Heat-Shock Protein: A Danger Signal to the Innate Immune System. J. Immunol. 1999, 162, 3212–3219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flohé, S.B.; Brüggemann, J.; Lendemans, S.; Nikulina, M.; Meierhoff, G.; Flohé, S.; Kolb, H. Human Heat Shock Protein 60 Induces Maturation of Dendritic Cells Versus a Th1-Promoting Phenotype. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 2340–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kol, A.; Lichtman, A.H.; Finberg, R.W.; Libby, P.; Kurt-Jones, E.A. Cutting Edge: Heat Shock Protein (HSP) 60 Activates the Innate Immune Response: CD14 Is an Essential Receptor for HSP60 Activation of Mononuclear Cells. J. Immunol. 2000, 164, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Osterloh, A.; Kalinke, U.; Weiss, S.; Fleischer, B.; Breloer, M. Synergistic and Differential Modulation of Immune Responses by Hsp60 and Lipopolysaccharide. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 4669–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breloer, M.; Dorner, B.; Moré, S.H.; Roderian, T.; Fleischer, B.; Bonin, A.V. Heat shock proteins as ’danger signals’: Eukaryotic Hsp60 enhances and accelerates antigen-specific IFN-γ production in T cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001, 31, 2051–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin-Zhorov, A.; Cahalon, L.; Tal, G.; Margalit, R.; Lider, O.; Cohen, I.R. Heat shock protein 60 enhances CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell function via innate TLR2 signaling. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 2022–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quintana, F.J.; Cohen, I.R. The HSP60 immune system network. Trends Immunol. 2011, 32, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eden, W.; van der Zee, R.; Prakken, B. Heat-shock proteins induce T-cell regulation of chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2005, 5, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Kleer, I.M.; Kamphuis, S.M.; Rijkers, G.T.; Scholtens, L.; Gordon, G.; De Jager, W.; Hafner, R.; van de Zee, R.; van Eden, W.; Kuis, W.; et al. The spontaneous remission of juvenile idiopathic arthritis is characterized by CD30+ T cells directed to human heat-shock protein 60 capable of producing the regulatory cytokine interleukin-10. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 2001–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, S.; Chen, L.; Xu, R.; Lv, Y.; Wu, D.; Guo, M.; et al. HSP60-regulated Mitochondrial Proteostasis and Protein Translation Promote Tumor Growth of Ovarian Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 019–48992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, C.; Sun, H.; Zheng, C.; Gao, J.; Fu, Q.; Hu, N.; Shao, X.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, J.; Nie, K.; et al. Oncogenic HSP60 regulates mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to support Erk1/2 activation during pancreatic cancer cell growth. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 017–0196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Teng, R.; Liu, Z.; Tang, H.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; Chen, L.; Song, J.; Liu, X.; Deng, H. HSP60 silencing promotes Warburg-like phenotypes and switches the mitochondrial function from ATP production to biosynthesis in ccRCC cells. Redox Biol. 2019, 24, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.B.; Shao, Y.M.; Miao, S.; Wang, L. The diversity of the DnaJ/Hsp40 family, the crucial partners for Hsp70 chaperones. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2006, 63, 2560–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, C.Y.; Lee, S.; Cyr, D.M. Mechanisms for regulation of Hsp70 function by Hsp40. Cell Stress Chaperones 2003, 8, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, A.; Tomoyasu, T.; Matsui, H.; Yamamoto, T. The DnaK/DnaJ chaperone machinery of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium is essential for invasion of epithelial cells and survival within macrophages, leading to systemic infection. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 1364–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cui, J.; Ma, C.; Ye, G.; Shi, Y.; Xu, W.; Zhong, L.; Wang, J.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H. DnaJ (hsp40) of Streptococcus pneumoniae is involved in bacterial virulence and elicits a strong natural immune reaction via PI3K/JNK. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 83, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.N.; Bansal, A.; Shukla, D.; Paliwal, P.; Sarada, S.K.; Mustoori, S.R.; Banerjee, P.K. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of DnaJ (hsp40) of Streptococcus pneumoniae against lethal infection in mice. Vaccine 2006, 24, 6225–6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gong, Y.; Niu, S.; Yin, N.; Yao, R.; Xu, W.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; He, Y.; et al. Immunization with DnaJ (hsp40) could elicit protection against nasopharyngeal colonization and invasive infection caused by different strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Vaccine 2011, 29, 1736–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukaj, S.; Kotlarz, A.; Jozwik, A.; Smolenska, Z.; Bryl, E.; Witkowski, J.M.; Lipinska, B. Hsp40 proteins modulate humoral and cellular immune response in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Cell Stress Chaperones 2010, 15, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhao, X.; Huang, G. HSP40 interacts with pyruvate kinase M2 and regulates glycolysis and cell proliferation in tumor cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.H.; Shyu, R.Y.; Wu, C.C.; Chen, M.L.; Lee, M.C.; Lin, Y.Y.; Wang, L.K.; Jiang, S.Y.; Tsai, F.M. Tazarotene-Induced Gene 1 Interacts with DNAJC8 and Regulates Glycolysis in Cervical Cancer Cells. Mol. Cells 2018, 41, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Webster, J.M.; Darling, A.L.; Uversky, V.N.; Blair, L.J. Small Heat Shock Proteins, Big Impact on Protein Aggregation in Neurodegenerative Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslbeck, M.; Franzmann, T.; Weinfurtner, D.; Buchner, J. Some like it hot: The structure and function of small heat-shock proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005, 12, 842–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.P.; Benjamin, I.J. Small heat shock proteins: A new classification scheme in mammals. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005, 38, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousman, S.S.; Tomooka, B.H.; van Noort, J.M.; Wawrousek, E.F.; O’Conner, K.; Hafler, D.A.; Sobel, R.A.; Robinson, W.H.; Steinman, L. Protective and therapeutic role for αB-crystallin in autoimmune demyelination. Nature 2007, 448, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Guo, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, M.; Huang, Y.; Wen, D.; Song, J.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, M.; et al. Small heat shock protein CRYAB inhibits intestinal mucosal inflammatory responses and protects barrier integrity through suppressing IKKβ activity. Mucosal. Immunol. 2019, 12, 1291–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Noort, J.M.; Bsibsi, M.; Nacken, P.; Gerritsen, W.H.; Amor, S. The link between small heat shock proteins and the immune system. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44, 1670–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Noort, J.M.; Bsibsi, M.; Gerritsen, W.H.; van der Valk, P.; Bajramovic, J.J.; Steinman, L.; Amor, S. αB-Crystallin Is a Target for Adaptive Immune Responses and a Trigger of Innate Responses in Preactive Multiple Sclerosis Lesions. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 69, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, M.F.; Singh, D.; Taiyab, A.; Ramakrishna, T.; Raman, B.; Rao Ch, M. Selective Cu2+ binding, redox silencing, and cytoprotective effects of the small heat shock proteins alphaA- and alphaB-crystallin. J. Mol. Biol. 2008, 382, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.S.; Reddy, P.Y.; Sreedhar, B.; Reddy, G.B. αB-crystallin-assisted reactivation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase upon refolding. Biochem. J. 2005, 391, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De, A.K.; Kodys, K.M.; Yeh, B.S.; Miller-Graziano, C. Exaggerated Human Monocyte IL-10 Concomitant to Minimal TNF-α Induction by Heat-Shock Protein 27 (Hsp27) Suggests Hsp27 Is Primarily an Antiinflammatory Stimulus. J. Immunol. 2000, 165, 3951–3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Laudanski, K.; De, A.; Miller-Graziano, C. Exogenous heat shock protein 27 uniquely blocks differentiation of monocytes to dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007, 37, 2812–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, N.; Nasti, T.H.; Huang, C.M.; Huber, B.S.; Jaleel, T.; Lin, H.Y.; Xu, H.; Elmets, C.A. Heat shock proteins HSP27 and HSP70 are present in the skin and are important mediators of allergic contact hypersensitivity. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salari, S.; Seibert, T.; Chen, Y.-X.; Hu, T.; Shi, C.; Zhao, X.; Cuerrier, C.M.; Raizman, J.E.; O’Brien, E.R. Extracellular HSP27 acts as a signaling molecule to activate NF-κB in macrophages. Cell Stress Chaperones 2013, 18, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rayner, K.; Chen, Y.X.; Siebert, T.; O’Brien, E.R. Heat shock protein 27: Clue to understanding estrogen-mediated atheroprotection? Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2010, 20, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Chi, Z.; Jiang, D.; Xu, T.; Yu, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Q.; Guo, X.; et al. Cholesterol Homeostatic Regulator SCAP-SREBP2 Integrates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Cholesterol Biosynthetic Signaling in Macrophages. Immunity 2018, 49, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duewell, P.; Kono, H.; Rayner, K.J.; Sirois, C.M.; Vladimer, G.; Bauernfeind, F.G.; Abela, G.S.; Franchi, L.; Nuñez, G.; Schnurr, M.; et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 2010, 464, 1357–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chopra, S.; Giovanelli, P.; Alvarado-Vazquez, P.A.; Alonso, S.; Song, M.; Sandoval, T.A.; Chae, C.S.; Tan, C.; Fonseca, M.M.; Gutierrez, S.; et al. IRE1α-XBP1 signaling in leukocytes controls prostaglandin biosynthesis and pain. Science 2019, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlen, P.; Kretz-Remy, C.; Préville, X.; Arrigo, A.P. Human hsp27, Drosophila hsp27 and human alphaB-crystallin expression-mediated increase in glutathione is essential for the protective activity of these proteins against TNFalpha-induced cell death. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 2695–2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadono, T.; Zhang, X.Q.; Srinivasan, S.; Ishida, H.; Barry, W.H.; Benjamin, I.J. CRYAB and HSPB2 deficiency increases myocyte mitochondrial permeability transition and mitochondrial calcium uptake. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2006, 40, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldens, L.; van Genesen, S.T.; Hanssen, L.L.; Hageman, J.; Kampinga, H.H.; Lubsen, N.H. Protein refolding in peroxisomes is dependent upon an HSF1-regulated function. Cell Stress Chaperones 2012, 17, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wanders, R.J.A.; Waterham, H.R.; Ferdinandusse, S. Metabolic Interplay between Peroxisomes and Other Subcellular Organelles Including Mitochondria and the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yarosz, E.L.; Chang, C.H. The Role of Reactive Oxygen Species in Regulating T Cell-mediated Immunity and Disease. Immune. Netw. 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista-Gonzalez, A.; Vidal, R.; Criollo, A.; Carreño, L.J. New Insights on the Role of Lipid Metabolism in the Metabolic Reprogramming of Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Levy, B.D. Resolvins in inflammation: Emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2657–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cara, F.; Andreoletti, P.; Trompier, D.; Vejux, A.; Bülow, M.H.; Sellin, J.; Lizard, G.; Cherkaoui-Malki, M.; Savary, S. Peroxisomes in Immune Response and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2019, 20, 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chu, B.B.; Liao, Y.C.; Qi, W.; Xie, C.; Du, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Miao, H.H.; Li, B.L.; Song, B.L. Cholesterol transport through lysosome-peroxisome membrane contacts. Cell 2015, 161, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ma, X.; Bi, E.; Lu, Y.; Su, P.; Huang, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Yang, M.; Kalady, M.F.; Qian, J.; et al. Cholesterol Induces CD8(+) T Cell Exhaustion in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransen, M.; Nordgren, M.; Wang, B.; Apanasets, O. Role of peroxisomes in ROS/RNS-metabolism: Implications for human disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Cara, F.; Sheshachalam, A.; Braverman, N.E.; Rachubinski, R.A.; Simmonds, A.J. Peroxisome-Mediated Metabolism Is Required for Immune Response to Microbial Infection. Immunity 2018, 48, 832–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Reddy, V.S.; Madala, S.K.; Trinath, J.; Reddy, G.B. Extracellular small heat shock proteins: Exosomal biogenesis and function. Cell Stress Chaperones 2018, 23, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, E.A.; Ono, K.; Eguchi, T. Roles of Extracellular HSPs as Biomarkers in Immune Surveillance and Immune Evasion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Maio, A.; Vazquez, D. Extracellular heat shock proteins: A new location, a new function. Shock 2013, 40, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weng, D.; Song, B.; Koido, S.; Calderwood, S.K.; Gong, J. Immunotherapy of radioresistant mammary tumors with early metastasis using molecular chaperone vaccines combined with ionizing radiation. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gong, J.; Zhang, Y.; Durfee, J.; Weng, D.; Liu, C.; Koido, S.; Song, B.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Calderwood, S.K. A heat shock protein 70-based vaccine with enhanced immunogenicity for clinical use. J. Immunol. 2010, 184, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delneste, Y.; Magistrelli, G.; Gauchat, J.; Haeuw, J.; Aubry, J.; Nakamura, K.; Kawakami-Honda, N.; Goetsch, L.; Sawamura, T.; Bonnefoy, J.; et al. Involvement of LOX-1 in dendritic cell-mediated antigen cross-presentation. Immunity 2002, 17, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pucci, S.; Polidoro, C.; Greggi, C.; Amati, F.; Morini, E.; Murdocca, M.; Biancolella, M.; Orlandi, A.; Sangiuolo, F.; Novelli, G. Pro-oncogenic action of LOX-1 and its splice variant LOX-1Δ4 in breast cancer phenotypes. Cell Death. Dis. 2019, 10, 1018–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kataoka, H.; Kume, N.; Miyamoto, S.; Minami, M.; Moriwaki, H.; Murase, T.; Sawamura, T.; Masaki, T.; Hashimoto, N.; Kita, T. Expression of lectinlike oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 in human atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation 1999, 99, 3110–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.F.; Fan, J.; Fedesco, M.; Guan, S.; Li, Y.; Bandyopadhyay, B.; Bright, A.M.; Yerushalmi, D.; Liang, M.; Chen, M.; et al. Transforming growth factor alpha (TGFalpha)-stimulated secretion of HSP90alpha: Using the receptor LRP-1/CD91 to promote human skin cell migration against a TGFbeta-rich environment during wound healing. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 28, 3344–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, J.S.; Hsu, Y.M.; Chen, C.C.; Chen, L.L.; Lee, C.C.; Huang, T.S. Secreted heat shock protein 90alpha induces colorectal cancer cell invasion through CD91/LRP-1 and NF-kappaB-mediated integrin alphaV expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 25458–25466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ogden, C.A.; deCathelineau, A.; Hoffmann, P.R.; Bratton, D.; Ghebrehiwet, B.; Fadok, V.A.; Henson, P.M. C1q and mannose binding lectin engagement of cell surface calreticulin and CD91 initiates macropinocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2001, 194, 781–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlacek, A.L.; Younker, T.P.; Zhou, Y.J.; Borghesi, L.; Shcheglova, T.; Mandoiu, I.I.; Binder, R.J. CD91 on dendritic cells governs immunosurveillance of nascent, emerging tumors. JCI Insight. 2019, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pawaria, S.; Binder, R.J. CD91-dependent programming of T-helper cell responses following heat shock protein immunization. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Actis Dato, V.; Chiabrando, G.A. The Role of Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 1 in Lipid Metabolism, Glucose Homeostasis and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bettigole, S.E.; Glimcher, L.H. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 33, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.; Finkel, T. Mitohormesis. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Angebault, C.; Fauconnier, J.; Patergnani, S.; Rieusset, J.; Danese, A.; Affortit, C.A.; Jagodzinska, J.; Mégy, C.; Quiles, M.; Cazevieille, C.; et al. ER-mitochondria cross-talk is regulated by the Ca(2+) sensor NCS1 and is impaired in Wolfram syndrome. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, eaaq1380. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Jiang, M.; Chen, W.; Zhao, T.; Wei, Y. Cancer and ER stress: Mutual crosstalk between autophagy, oxidative stress and inflammatory response. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 118, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filadi, R.; Theurey, P.; Pizzo, P. The endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling in health and disease: Molecules, functions and significance. Cell Calcium 2017, 62, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, H.; Raines, L.N.; Huang, S.C.-C. Molecular Chaperones: Molecular Assembly Line Brings Metabolism and Immunity in Shape. Metabolites 2020, 10, 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10100394

Zhao H, Raines LN, Huang SC-C. Molecular Chaperones: Molecular Assembly Line Brings Metabolism and Immunity in Shape. Metabolites. 2020; 10(10):394. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10100394

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Haoxin, Lydia N. Raines, and Stanley Ching-Cheng Huang. 2020. "Molecular Chaperones: Molecular Assembly Line Brings Metabolism and Immunity in Shape" Metabolites 10, no. 10: 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo10100394