Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Cosmetics: Building a Framework for Safety, Efficacy, and Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Definition, Composition, and Functional Roles of EVs in Plants

3. PDEV Versus Liposomes: Structure and Function Comparison

4. Sources of PDEVs: Raw Biomass or In Vitro Cultures

4.1. PDEVs Derived from Raw Plant Material

4.2. Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles from In Vitro Cultures: Definition and Production

5. PDEV Extraction Methods

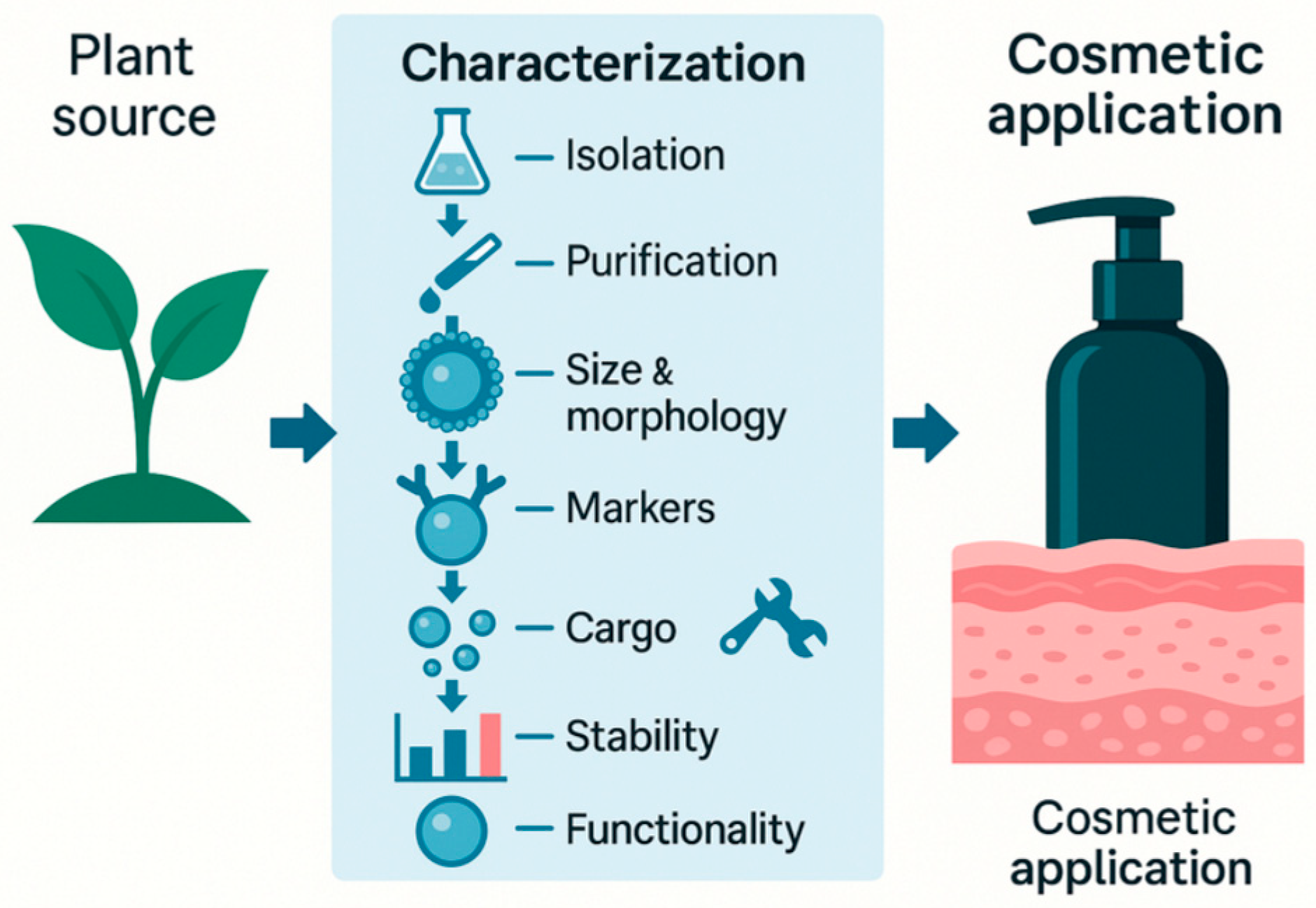

6. Minimal Characterization for PDEVs

6.1. Physical and Chemical Characterization of Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

6.2. Cargo Characterization of Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

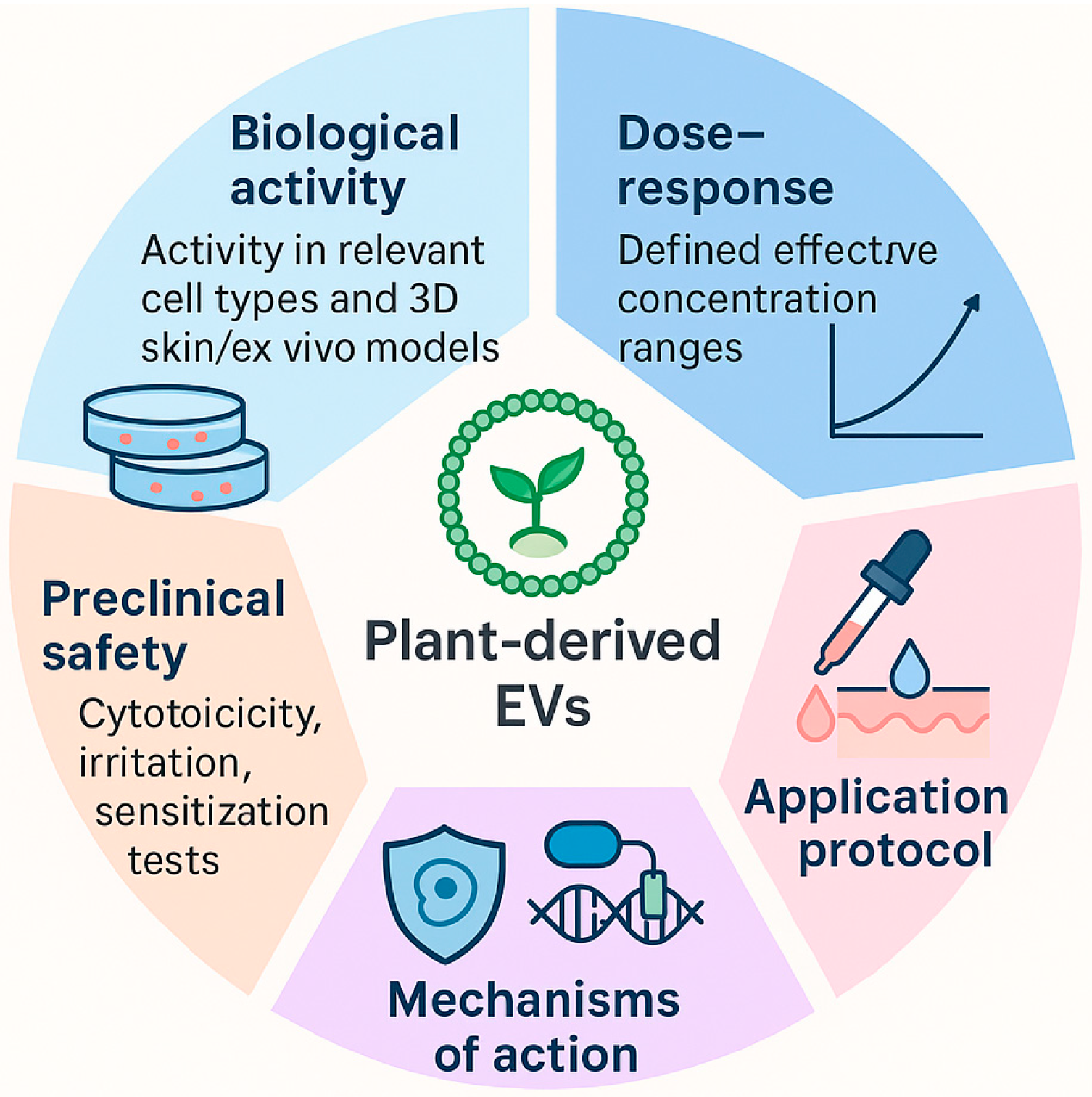

7. Functional Testing and Biological Relevance of PDEVs in Cosmetics

7.1. Cellular Uptake and Competency to Deliver Cargo

7.2. Intracellular Calcium Dynamics (Proximal Activation and Signaling Competence)

7.3. Antioxidant and Photoprotective Activity

7.4. Anti-Inflammatory and Soothing Effects

7.5. Barrier Integrity and Homeostasis

7.6. Regeneration and Remodeling of Extracellular-Matrix

7.7. Angiogenesis and Vascular Support (Wound-Healing Relevance)

7.8. Pigmentation and Photo-Evenness (Optional, Claim-Dependent)

7.9. Microbiome-Aware Endpoints (Skin Ecology)

7.10. Advanced Models for Translational Relevance

8. Regulatory for PDEVs

9. Stability and Storage Considerations for PDEVs

10. Future Perspectives

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation List

| 2,4-D | 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid |

| AF4 | asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation |

| AFM | atomic force microscopy |

| BAP | 6-benzylaminopurine |

| CapEx | capital expenditure |

| CFD | computational fluid dynamics |

| CMC | chemistry, manufacturing, and control |

| CoA | certificate of analysis |

| DC | differential centrifugation |

| DGDG | digalactosyldiacyl-glycerol |

| DLS | dynamic light scattering |

| DO | dissolved oxygen |

| DoE | design of experiments |

| dPCR | digital Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| ECM | extracellular matrix |

| ELN | elastin |

| ELS/LDV | electrophoretic light scattering/laser Doppler velocimetry |

| EVs | extracellular vesicles |

| GAGs | glycosaminoglycans |

| GC | gas chromatography |

| GIPCs | glycosyl inositol phosphorylceramides |

| HACCP | hazard analysis and critical control points |

| IF | immunofluorescence |

| JA | jasmonic acid |

| LC | liquid chromatography |

| LLOQ | lower limit of quantification |

| LOD | limit of detection |

| LOQ | limit of quantification |

| LOR | limit of reporting |

| MGDG | monogalactosyldiacylglycerol |

| MMP-1 | matrix metalloproteinase-1 |

| MS | mass spectrometry |

| NGS | Next Generation Sequencing |

| NTA | nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OpEx | operational expenditure |

| PA | phosphatidic acid |

| PAT | process analytical technology |

| PC | phosphatidylcholine |

| PDI | polydispersity index |

| PE | phosphatidylethanolamine |

| PEG | polyethylene glycol |

| PGRs | plant growth regulators |

| PI | phosphatidylinositol |

| QC | quality control |

| CQA | critical quality attributes |

| QMS | quality management system |

| RHE | reconstructed human epidermis |

| ROM | reactive oxygen metabolites |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RT-qPCR: | Reverse Transcription quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| SA | salicylic acid |

| SEC | size-exclusion chromatography |

| SOPs | standard operating procedures |

| SPE | solid-phase extraction |

| TAMC | total aerobic microbial count |

| TEER | transepithelial electrical resistance |

| TEM | transmission electron microscopy |

| TFF | tangential flow filtration |

| TG | Test Guideline |

| TIMP-1 | tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 |

| TJ | tight junction |

| TRPS | tunable resistive pulse sensing |

| TYMC | total yeast and mold count |

| UC | ultracentrifugation |

| UF | ultrafiltration |

| VIC | vacuum infiltration–centrifugation |

References

- Imafuku, A.; Sjoqvist, S. Extracellular Vesicle Therapeutics in Regenerative Medicine. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2021, 1312, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferroni, L.; Gardin, C.; D’Amora, U.; Calzà, L.; Ronca, A.; Tremoli, E.; Ambrosio, L.; Zavan, B. Exosomes of mesenchymal stem cells delivered from methacrylated hyaluronic acid patch improve the regenerative properties of endothelial and dermal cells. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 139, 213000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferroni, L.; D’Amora, U.; Gardin, C.; Leo, S.; Dalla Paola, L.; Tremoli, E.; Giuliani, A.; Calzà, L.; Ronca, A.; Ambrosio, L.; et al. Stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles embedded into methacrylated hyaluronic acid wound dressings accelerate wound repair in a pressure model of diabetic ulcer. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardin, C.; Ferroni, L.; Erdoğan, Y.K.; Zanotti, F.; De Francesco, F.; Trentini, M.; Brunello, G.; Ercan, B.; Zavan, B. Nanostructured Modifications of Titanium Surfaces Improve Vascular Regenerative Properties of Exosomes Derived from Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Preliminary In Vitro Results. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, T.S.; Saiganesh, R.; Sivagnanavelmurugan, M.; Diomede, F. Human Skin Microbiota-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Their Cosmeceutical Possibilities-A Mini Review. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 34, e70073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chachques, J.C.; Gardin, C.; Lila, N.; Ferroni, L.; Migonney, V.; Falentin-Daudre, C.; Zanotti, F.; Trentini, M.; Brunello, G.; Rocca, T.; et al. Elastomeric Cardiowrap Scaffolds Functionalized with Mesenchymal Stem Cells-Derived Exosomes Induce a Positive Modulation in the Inflammatory and Wound Healing Response of Mesenchymal Stem Cell and Macrophage. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, J.A.; Goberdhan, D.C.I.; O’Driscoll, L.; Buzas, E.I.; Blenkiron, C.; Bussolati, B.; Cai, H.; Di Vizio, D.; Driedonks, T.A.P.; Erdbrügger, U.; et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles (MISEV2023): From basic to advanced approaches. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batsukh, S.; Oh, S.; Lee, J.M.; Joo, J.H.J.; Son, K.H.; Byun, K. Extracellular Vesicles from Ecklonia cava and Phlorotannin Promote Rejuvenation in Aged Skin. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Ren, Y.; Sayed, M.; Hu, X.; Lei, C.; Kumar, A.; Hutchins, E.; Mu, J.; Deng, Z.; Luo, C.; et al. Plant-Derived Exosomal MicroRNAs Shape the Gut Microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 2018, 24, 637–652.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabay, A.Z.; Barar, J.; Hekmatshoar, Y.; Rahbar Saadat, Y. Multifaceted Therapeutic Potential of Plant-Derived Exosomes: Immunomodulation, Anticancer, Anti-Aging, Anti-Melanogenesis, Detoxification, and Drug Delivery. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.K.; Choi, Y.C.; Cho, S.H.; Choi, J.S.; Cho, Y.W. The Antioxidant Effect of Small Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Aloe vera Peels for Wound Healing. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2021, 18, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, F.; Wang, J.; Lu, R. Techniques and Applications of Animal- and Plant-Derived Exosome-Based Drug Delivery System. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2020, 16, 1543–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Gao, J.; He, Y.; Jiang, L. Plant extracellular vesicles. Protoplasma 2020, 257, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.B.; Deng, X.; Shen, L.S.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ye, L.; Chen, S.-B.; Yang, D.-J.; Chen, G.-Q. Advances in plant-derived extracellular vesicles: Isolation, composition, and biological functions. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 11319–11341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nsairat, H.; Khater, D.; Sayed, U.; Odeh, F.; Al Bawab, A.; Alshaer, W. Liposomes: Structure, composition, types, and clinical applications. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozak, A.; Lavrih, E.; Mikhaylov, G.; Turk, B.; Vasiljeva, O. Navigating the Clinical Landscape of Liposomal Therapeutics in Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Zaidi, S.S.; Fatima, F.; Ali Zaidi, S.A.; Zhou, D.; Deng, W.; Liu, S. Engineering siRNA therapeutics: Challenges and strategies. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, N.; Li, J.; Zeng, L.; You, J.; Li, R.; Qin, A.; Liu, X.; Yan, F.; Zhou, Z. Plant-Derived Exosome-Like Nanovesicles: Current Progress and Prospects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 4987–5009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanidou, T.; Tsouknidas, A. Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Therapeutic Nanocarriers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, J.; Brigger, F.; Leroux, J.C. Extracellular vesicles versus lipid nanoparticles for the delivery of nucleic acids. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2024, 215, 115461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggio, L.; Arrabito, G.; Ferrara, V.; Vivarelli, S.; Paternò, G.; Marchetti, B.; Pignataro, B.; Iraci, N. Mastering the Tools: Natural versus Artificial Vesicles in Nanomedicine. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2020, 9, e2000731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Zheng, W.; Sun, Z.; Luo, T.; Li, Z.; Lai, W.; Jing, M.; Kuang, M.; Su, H.; Tan, W.; et al. Plant-derived exosomes: Unveiling the similarities and disparities between conventional extract and innovative form. Phytomedicine 2025, 145, 157087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iriawati, I.; Vitasasti, S.; Rahmadian, F.N.A.; Barlian, A. Isolation and characterization of plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles from Carica papaya L. fruit and their potential as anti-inflammatory agent. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, X.; Wang, H.; Tie, H.; Liao, J.; Luo, Y.; Huang, W.; Yu, R.; Song, L.; Zhu, J. Novel plant-derived exosome-like nanovesicles from Catharanthus roseus: Preparation, characterization, and immunostimulatory effect via TNF-α/NF-κB/PU.1 axis. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaeva, L.; Tolstyko, E.; Putevich, E.; Kil, Y.; Spitsyna, A.; Emelianova, S.; Solianik, A.; Yastremsky, E.; Garmay, Y.; Komarova, E.; et al. Microalgae-Derived Vesicles: Natural Nanocarriers of Exogenous and Endogenous Proteins. Plants 2025, 14, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giancaterino, S.; Boi, C. Alternative biological sources for extracellular vesicles production and purification strategies for process scale-up. Biotechnol. Adv. 2023, 63, 108092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, L.T.; Ng, C.Y.; Al-Masawa, M.E.; Foo, J.B.; How, C.W.; Ng, M.H.; Law, J.X. Extracellular Vesicles in Facial Aesthetics: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahm, W.J.; Nikas, C.; Goldust, M.; Horneck, N.; Cervantes, J.A.; Burshtein, J.; Tsoukas, M. Exosomes in Dermatology: A Comprehensive Review of Current Applications, Clinical Evidence, and Future Directions. Int. J. Dermatol. 2025, 64, 1995–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocholatá, M.; Malý, J.; Kříženecká, S.; Janoušková, O. Diversity of extracellular vesicles derived from calli, cell culture and apoplastic fluid of tobacco. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perut, F.; Roncuzzi, L.; Avnet, S.; Massa, A.; Zini, N.; Sabbadini, S.; Giampieri, F.; Mezzetti, B.; Baldini, N. Strawberry-Derived Exosome-Like Nanoparticles Prevent Oxidative Stress in Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, J. Exosome-like Nanoparticles from Ginger Rhizomes Inhibited NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 2690–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regente, M.; Pinedo, M.; San Clemente, H.; Balliau, T.; Jamet, E.; de la Canal, L. Plant extracellular vesicles are incorporated by a fungal pathogen and inhibit its growth. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 5485–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, M.; Nawaz, J.; Duan, X. Regulatory Mechanisms of Natural Active Ingredients and Compounds on Keratinocytes and Fibroblasts in Mitigating Skin Photoaging. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 1943–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Raimo, R.; Mizzoni, D.; Aloi, A.; Pietrangelo, G.; Dolo, V.; Poppa, G.; Fais, S.; Logozzi, M. Antioxidant Effect of a Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles’ Mix on Human Skin Fibroblasts: Induction of a Reparative Process. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruk, G.; Del Giudice, R.; Rigano, M.M.; Monti, D.M. Antioxidants from Plants Protect against Skin Photoaging. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 1454936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Park, J.H. Isolation of Aloe saponaria-Derived Extracellular Vesicles and Investigation of Their Potential for Chronic Wound Healing. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Xiong, F.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, Y. Tea-derived exosome-like nanoparticles prevent irritable bowel syndrome induced by water avoidance stress in rat model. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 39, 2690–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, T.; Hou, L.; Cao, Y.; Li, M.; Sheng, X.; Cheng, W.; Yan, L.; Zheng, L. Tea Extracellular Vesicle-Derived MicroRNAs Contribute to Alleviate Intestinal Inflammation by Reprogramming Macrophages. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 6745–6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orefice, N.S.; Di Raimo, R.; Mizzoni, D.; Logozzi, M.; Fais, S. Purposing plant-derived exosomes-like nanovesicles for drug delivery: Patents and literature review. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2023, 33, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trentini, M.; Zanolla, I.; Tiengo, E.; Zanotti, F.; Sommella, E.; Merciai, F.; Campiglia, P.; Licastro, D.; Degasperi, M.; Lovatti, L.; et al. Link between organic nanovescicles from vegetable kingdom and human cell physiology: Intracellular calcium signalling. J. Nanobiotechnology 2024, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trentini, M.; Zanolla, I.; Zanotti, F.; Tiengo, E.; Licastro, D.; Dal Monego, S.; Lovatti, L.; Zavan, B. Apple Derived Exosomes Improve Collagen Type I Production and Decrease MMPs during Aging of the Skin through Downregulation of the NF-κB Pathway as Mode of Action. Cells 2022, 11, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trentini, M.; Zanotti, F.; Tiengo, E.; Camponogara, F.; Degasperi, M.; Licastro, D.; Lovatti, L.; Zavan, B. An Apple a Day Keeps the Doctor Away: Potential Role of miRNA 146 on Macrophages Treated with Exosomes Derived from Apples. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logozzi, M.; Di Raimo, R.; Mizzoni, D.; Fais, S. Nanovesicles from Organic Agriculture-Derived Fruits and Vegetables: Characterization and Functional Antioxidant Content. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, G.; Logozzi, M.; Mizzoni, D.; Di Raimo, R.; Cerio, A.; Dolo, V.; Pasquini, L.; Screnci, M.; Ottone, T.; Testa, U.; et al. Ex Vivo Anti-Leukemic Effect of Exosome-like Grapefruit-Derived Nanovesicles from Organic Farming-The Potential Role of Ascorbic Acid. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 15663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Leal, C.A.; Puente-Garza, C.A.; García-Lara, S. In vitro plant tissue culture: Means for production of biological active compounds. Planta 2018, 248, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, O.; Sukhikh, S.; Pungin, A.; Ivanova, S.; Asyakina, L.; Prosekov, A. Modern Trends in the In Vitro Production and Use of Callus, Suspension Cells and Root Cultures of Medicinal Plants. Molecules 2020, 25, 5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traverse, K.K.F.; Mortensen, S.; Trautman, J.G.; Danison, H.; Rizvi, N.F.; Lee-Parsons, C.W.T. Generation of Stable Catharanthus roseus Hairy Root Lines with Agrobacterium rhizogenes. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2469, 129–144. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, M.E.; Wang, X.Y.; Escalona, M.; Yan, L.; Huang, L.F. Somatic embryogenesis of Arabica coffee in temporary immersion culture: Advances, limitations, and perspectives for mass propagation of selected genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 994578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höll, J.; Lindner, S.; Walter, H.; Joshi, D.; Poschet, G.; Pfleger, S.; Ziegler, T.; Hell, R.; Bogs, J.; Rausch, T. Impact of pulsed UV-B stress exposure on plant performance: How recovery periods stimulate secondary metabolism while reducing adaptive growth attenuation. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, R.J.; Fichman, Y.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Mittler, R. Jasmonic acid and salicylic acid modulate systemic reactive oxygen species signaling during stress responses. Plant Physiol. 2023, 191, 862–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wawrosch, C.; Zotchev, S.B. Production of bioactive plant secondary metabolites through in vitro technologies-status and outlook. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 6649–6668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A. Hairy Root Culture an Alternative for Bioactive Compound Production from Medicinal Plants. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2021, 22, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, M.; Jin, X.; Chen, S.; Yang, N.; Feng, G. Plant-derived extracellular vesicles -a novel clinical anti-inflammatory drug carrier worthy of investigation. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 169, 115904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashant, S.P.; Bhawana, M. An update on biotechnological intervention mediated by plant tissue culture to boost secondary metabolite production in medicinal and aromatic plants. Physiol. Plant. 2024, 176, e14400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nix, C.; Sulejman, S.; Fillet, M. Development of complementary analytical methods to characterize extracellular vesicles. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2024, 1329, 343171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsbury, N.J.; McDonald, K.A. Quantitative evaluation of E1 endoglucanase recovery from tobacco leaves using the vacuum infiltration-centrifugation method. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 483596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.J.; Wang, M.H.; Kuo, C.Y.; Pan, M.H. Optimizing Isolation Methods and Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Lotus-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Modulating Inflammation and Promoting Wound Healing. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2025, 11, 4424–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Song, Q.; Shaw, P.C.; Wu, Y.; Zuo, Z.; Yu, R. Tangerine Peel-Derived Exosome-Like Nanovesicles Alleviate Hepatic Steatosis Induced by Type 2 Diabetes: Evidenced by Regulating Lipid Metabolism and Intestinal Microflora. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 10023–10043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kırbaş, O.K.; Sağraç, D.; Çiftçi, Ö.; Özdemir, G.; Öztürkoğlu, D.; Bozkurt, B.T.; Derman, Ü.C.; Taşkan, E.; Taşlı, P.N.; Özdemir, B.S.; et al. Unveiling the potential: Extracellular vesicles from plant cell suspension cultures as a promising source. Biofactors 2025, 51, e2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzaneque-López, M.C.; González-Arce, A.; Pérez-Bermúdez, P.; Soler, C.; Marcilla, A.; Sánchez-López, C.M. Pasteurization and lyophilization affect membrane proteins of pomegranate-derived nanovesicles reducing their functional properties and cellular uptake. Food Chem. 2025, 483, 144303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.K.; Rhee, W.J. Antioxidative Effects of Carrot-Derived Nanovesicles in Cardiomyoblast and Neuroblastoma Cells. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeyen, E.; Van Mol, K.; Baggerman, G.; Willems, H.; Boonen, K.; Rolfo, C.; Pauwels, P.; Jacobs, A.; Schildermans, K.; Cho, W.C.; et al. Ultrafiltration and size exclusion chromatography combined with asymmetrical-flow field-flow fractionation for the isolation and characterisation of extracellular vesicles from urine. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2018, 7, 1490143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López de Las Hazas, M.C.; Tomé-Carneiro, J.; Del Pozo-Acebo, L.; Del Saz-Lara, A.; Chapado, L.A.; Balaguer, L.; Rojo, E.; Espín, J.C.; Crespo, C.; Moreno, D.A.; et al. Therapeutic potential of plant-derived extracellular vesicles as nanocarriers for exogenous miRNAs. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 198, 106999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Tong, L.; Dong, M.; Xu, T.; Li, Z. Optimized AF4 combined with density cushion ultracentrifugation enables profiling of high-purity human blood extracellular vesicles. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2024, 13, e12470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.T.; Wunsch, B.H.; Dogra, N.; Ahsen, M.E.; Lee, K.; Yadav, K.K.; Weil, R.; Pereira, M.A.; Patel, J.V.; Duch, E.A.; et al. Integrated nanoscale deterministic lateral displacement arrays for separation of extracellular vesicles from clinically-relevant volumes of biological samples. Lab. Chip 2018, 18, 3913–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.S.; Ha, J.H.; Jeong, S.H.; Lee, J.I.; Lee, B.W.; Jeong, Y.J.; Kim, C.Y.; Park, J.-Y.; Ryu, Y.B.; Kwon, H.-J.; et al. Immunological Effects of Aster yomena Callus-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Potential Therapeutic Agents against Allergic Asthma. Cells 2022, 11, 2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-López, C.M.; Manzaneque-López, M.C.; Pérez-Bermúdez, P.; Soler, C.; Marcilla, A. Characterization and bioactivity of extracellular vesicles isolated from pomegranate. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 12870–12882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lyden, D. Asymmetric-flow field-flow fractionation technology for exomere and small extracellular vesicle separation and characterization. Nat. Protoc. 2019, 14, 1027–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Chavda, V.P.; Vaghela, D.A.; Bezbaruah, R.; Gogoi, N.R.; Patel, K.; Kulkarni, M.; Shen, B.; Singla, R.K. Plant-derived exosomes in therapeutic nanomedicine, paving the path toward precision medicine. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanao, E.; Wada, S.; Nishida, H.; Kubo, T.; Tanigawa, T.; Imami, K.; Shimoda, A.; Umezaki, K.; Sasaki, Y.; Akiyoshi, K.; et al. Classification of Extracellular Vesicles Based on Surface Glycan Structures by Spongy-like Separation Media. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 18025–18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xiao, S.; Wang, D.; Qin, C.; Wei, H.; Li, D. A review on separation and application of plant-derived exosome-like nanoparticles. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, e2300669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantarcıoğlu, M.; Yıldırım, G.; Akpınar Oktar, P.; Yanbakan, S.; Özer, Z.B.; Sarıca, D.Y.; Kürekçi, A.E. Coffee-Derived Exosome-Like Nanoparticles: Are They the Secret Heroes? Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 34, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longjohn, M.N.; Christian, S.L. Characterizing Extracellular Vesicles Using Nanoparticle-Tracking Analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2022, 2508, 353–373. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Li, Q.; Liang, Y.; Zu, M.; Chen, N.; Canup, B.S.B.; Luo, L.; Wang, C.; Zeng, L.; Xiao, B. Natural exosome-like nanovesicles from edible tea flowers suppress metastatic breast cancer. Acta Pharm. Sin. B. 2022, 12, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, S.L.; Broekman, M.L.; de Vrij, J. Tunable Resistive Pulse Sensing for the Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1545, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Vogel, R.; Savage, J.; Muzard, J.; Camera, G.D.; Vella, G.; Law, A.; Marchioni, M.; Mehn, D.; Geiss, O.; Peacock, B.; et al. Measuring particle concentration of multimodal synthetic reference materials and extracellular vesicles with orthogonal techniques: Who is up to the challenge? J. Extracell. Vesicles 2021, 10, e12052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizmar, P.; Yuana, Y. Detection and Characterization of Extracellular Vesicles by Transmission and Cryo-Transmission Electron Microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1660, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Linares, R.; Tan, S.; Gounou, C.; Brisson, A.R. Imaging and Quantification of Extracellular Vesicles by Transmission Electron Microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1545, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Skliar, M.; Chernyshev, V.S. Imaging of Extracellular Vesicles by Atomic Force Microscopy. J. Vis. Exp. 2019, 15, 59254. [Google Scholar]

- Parisse, P.; Rago, I.; Ulloa Severino, L.; Perissinotto, F.; Ambrosetti, E.; Paoletti, P.; Ricci, M.; Beltrami, A.P.; Cesselli, D.; Casalis, L. Atomic force microscopy analysis of extracellular vesicles. Eur. Biophys. J. 2017, 46, 813–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midekessa, G.; Godakumara, K.; Ord, J.; Viil, J.; Lättekivi, F.; Dissanayake, K.; Kopanchuk, S.; Rinken, A.; Andronowska, A.; Bhattacharjee, S.; et al. Zeta Potential of Extracellular Vesicles: Toward Understanding the Attributes that Determine Colloidal Stability. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 16701–16710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.Z.; Xu, H.M.; Liang, Y.J.; Xu, J.; Yue, N.N.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, C.-M.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.-S.; Nie, Y.-Q.; et al. Edible exosome-like nanoparticles from Portulaca oleracea L. mitigate DSS-induced colitis via facilitating double-positive CD4. J. Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zini, J.; Saari, H.; Ciana, P.; Viitala, T.; Lõhmus, A.; Saarinen, J.; Yliperttula, M. Infrared and Raman spectroscopy for purity assessment of extracellular vesicles. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 172, 106135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, K.; Martin, K.; FitzGerald, S.P.; O’Sullivan, J.; Wu, Y.; Blanco, A.; Richardson, C.; Mc Gee, M.M. A comparison of methods for the isolation and separation of extracellular vesicles from protein and lipid particles in human serum. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearfield, N.; Brotherton, D.; Gao, Z.; Inal, J.; Stotz, H.U. Establishment of an experimental system to analyse extracellular vesicles during apoplastic fungal pathogenesis. J. Extracell. Biol. 2025, 4, e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Huo, Y.; Yi, G.; Liu, C.; Jamil, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; et al. Isolation, Characterization, and Proteomic Analysis of Crude and Purified Extracellular Vesicles Extracted from. Plants 2024, 13, 3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taşkan, E.; Kırbaş, O.K.; Sağraç, D.; Kayı, Ş.; Hilal, İ.; Şahin, F.; Taşlı, P.N. Celery root-plant derived vesicles: Comprehensive isolation, characterization and proteomic analysis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Li, L.; Deng, J.; Ai, J.; Mo, S.; Ding, D.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhu, D.; Li, Q.; et al. Lipidomic analysis of plant-derived extracellular vesicles for guidance of potential anti-cancer therapy. Bioact. Mater. 2025, 46, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Yi, G.; Cao, G.; Midgley, A.C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, G. Dual-Carriers of Tartary Buckwheat-Derived Exosome-Like Nanovesicles Synergistically Regulate Glucose Metabolism in the Intestine-Liver Axis. Small 2025, 21, e2410124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, K.; Mongrand, S.; Beney, L.; Simon-Plas, F.; Gerbeau-Pissot, P. Differential effect of plant lipids on membrane organization: Specificities of phytosphingolipids and phytosterols. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 5810–5825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.J.; Wang, N.; Bao, J.J.; Zhu, H.X.; Wang, L.J.; Chen, X.Y. Lipidomic Analysis Reveals the Importance of GIPCs in Arabidopsis Leaf Extracellular Vesicles. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, N.; Hou, L.; Chen, X.; Bao, J.; Chen, F.; Cai, W.; Chen, X. Arabidopsis TETRASPANIN8 mediates exosome secretion and glycosyl inositol phosphoceramide sorting and trafficking. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, S.; Wada, H.; Kobayashi, K. Role of Galactolipids in Plastid Differentiation Before and After Light Exposure. Plants 2019, 8, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; He, B.; Jin, H. Isolation of Extracellular Vesicles from Arabidopsis. Curr. Protoc. 2022, 2, e352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, E.R.; Ortmannová, J.; Donald, N.A.; Alvim, J.; Blatt, M.R.; Žárský, V. Synergy among Exocyst and SNARE Interactions Identifies a Functional Hierarchy in Secretion during Vegetative Growth. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 2951–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocsfalvi, G.; Turiák, L.; Ambrosone, A.; Del Gaudio, P.; Puska, G.; Fiume, I.; Silvestre, T.; Vékey, K. Protein biocargo of citrus fruit-derived vesicles reveals heterogeneous transport and extracellular vesicle populations. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 229, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanly, C.; Moubarak, M.; Fiume, I.; Turiák, L.; Pocsfalvi, G. Membrane Transporters in Citrus clementina Fruit Juice-Derived Nanovesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez de Lope, M.M.; Sánchez-Pajares, I.R.; Herranz, E.; López-Vázquez, C.M.; González-Moro, A.; Rivera-Tenorio, A.; González-Sanz, C.; Sacristán, S.; Chicano-Gálvez, E.; de la Cuesta, F. A Compendium of Bona Fide Reference Markers for Genuine Plant Extracellular Vesicles and Their Degree of Phylogenetic Conservation. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2025, 14, e70147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Ma, L.; Pei, Y.; Qi, B.; Li, Y. Exploring oleosin allergenicity: Structural insights, diagnostic challenges, and advances in purification and solubilization. Food Chem. 2025, 490, 145153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Z.; Jin, H.; Tzfira, T.; Li, J. Multiple mechanism-mediated retention of a defective brassinosteroid receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2008, 20, 3418–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, L.; Cui, Y. Extracellular Vesicle Isolation and Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomic Analysis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Methods Mol. Biol. 2024, 2841, 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Ku, C.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, S.H.; Han, H.; Kim, M.J. The Role of miRNA167 in Skin Improvement: Insight from Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Rock Samphire. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betti, F.; Ladera-Carmona, M.J.; Weits, D.A.; Ferri, G.; Iacopino, S.; Novi, G.; Svezia, B.; Kunkowska, A.B.; Santaniello, A.; Piaggesi, A.; et al. Exogenous miRNAs induce post-transcriptional gene silencing in plants. Nat. Plants. 2021, 7, 1379–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.; Chen, B.; Jia, J.; Liu, J. Relationship between Protein, MicroRNA Expression in Extracellular Vesicles and Rice Seed Vigor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez Fajardo, C.; Morote, L.; Moreno-Giménez, E.; López-López, S.; Rubio-Moraga, Á.; Díaz-Guerra, M.J.M.; Diretto, G.; Jiménez, A.J.L.; Ahrazem, O.; Gómez-Gómez, L. Exosome-like nanoparticles from Arbutus unedo L. mitigate LPS-induced inflammation via JAK-STAT inactivation. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 11280–11290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleti, R.; Andriantsitohaina, R.; Martinez, M.C. Impact of polyphenols on extracellular vesicle levels and effects and their properties as tools for drug delivery for nutrition and health. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2018, 644, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Cao, X.; Wu, W.; Han, L.; Wang, F. Investigating the proliferative inhibition of HepG2 cells by exosome-like nanovesicles derived from Centella asiatica extract through metabolomics. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 176, 116855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Tian, Y.; Xue, C.; Niu, Q.; Chen, C.; Yan, X. Analysis of extracellular vesicle DNA at the single-vesicle level by nano-flow cytometry. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsergent, E.; Grisard, E.; Buchrieser, J.; Schwartz, O.; Théry, C.; Lavieu, G. Quantitative characterization of extracellular vesicle uptake and content delivery within mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanò, M.; Boselli, D.; Ragni, E.; de Girolamo, L.; Villa, C. Setting a Successful Sorting for Extracellular Vesicle Isolation. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 212, e67232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleri, M.P.; Pusceddu, T.; Sileo, L.; Ardondi, L.; Vitali, I.; Cappucci, I.P.; Basile, L.; Pezzotti, G.; Fiorica, F.; Ferroni, L.; et al. When Fat Talks: How Adipose-Derived Extracellular Vesicles Fuel Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, M.G.; Gardin, C.; Zamparini, F.; Ferroni, L.; Esposti, M.D.; Parchi, G.; Ercan, B.; Manzoli, L.; Fava, F.; Fabbri, P.; et al. Mineral-Doped Poly(L-lactide) Acid Scaffolds Enriched with Exosomes Improve Osteogenic Commitment of Human Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Yang, X.; Qiu, T.; An, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Q.; Jiang, L.; Yang, G.; Cao, J.; Sun, X.; et al. Exosomal miR-181a-2-3p derived from citreoviridin-treated hepatocytes activates hepatic stellate cells trough inducing mitochondrial calcium overload. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 358, 109899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.I.; Jo, Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.J.; Park, K.S. Photinia glabra-derived exosome-like nanovesicles mitigate skin inflammaging via dual regulation of inflammatory signaling and calcium homeostasis. Nanomedicine 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirosawa, K.M.; Sato, Y.; Kasai, R.S.; Yamaguchi, E.; Komura, N.; Ando, H.; Hoshino, A.; Yokota, Y.; Suzuki, K.G.N. Uptake of small extracellular vesicles by recipient cells is facilitated by paracrine adhesion signaling. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Li, Z.; Han, X.; Zhen, L.; Luo, C.; Liu, M.; Yu, K.; Ren, Y. Tumor-derived nanovesicles promote lung distribution of the therapeutic nanovector through repression of Kupffer cell-mediated phagocytosis. Theranostics 2019, 9, 2618–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Wu, T.; Jin, J.; Li, Z.; Cheng, W.; Dai, X.; Yang, K.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; et al. Exosome-like nanovesicles derived from Phellinus linteus inhibit Mical2 expression through cross-kingdom regulation and inhibit ultraviolet-induced skin aging. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Raimo, R.; Mizzoni, D.; Spada, M.; Dolo, V.; Fais, S.; Logozzi, M. Oral Treatment with Plant-Derived Exosomes Restores Redox Balance in H. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilasoniya, A.; Garaeva, L.; Shtam, T.; Spitsyna, A.; Putevich, E.; Moreno-Chamba, B.; Salazar-Bermeo, J.; Komarova, E.; Malek, A.; Valero, M.; et al. Potential of Plant Exosome Vesicles from Grapefruit (Citrus × paradisi) and Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) Juices as Functional Ingredients and Targeted Drug Delivery Vehicles. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Shin, H.Y.; Park, M.; Ahn, K.; Kim, S.J.; An, S.H. Exosome-Like Vesicles from Lithospermum erythrorhizon Callus Enhanced Wound Healing by Reducing LPS-Induced Inflammation. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 35, e2410022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Liu, F.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Li, X.; Yue, Q.; Su, L.; Yang, S.; Zhao, L. Lavender Exosome-Like nanoparticles attenuate UVB-Induced Photoaging via miR166-Mediated inflammation and collagen regulation. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Kim, J.G.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, H.C.; Kim, M.J. miRNA408 from Camellia japonica L. Mediates Cross-Kingdom Regulation in Human Skin Recovery. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Cao, F.; Cheng, J.; Pan, C.; Wei, Y.; Liu, T.; Jin, Y.; Yang, G. miR166u -enriched Polygonatum sibiricum exosome-like nanoparticles alleviate colitis by improving intestinal barrier through the TLR4/AKT pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 318 Pt 1, 144802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Liao, T.; Zeng, Z.; Mei, J.; Wu, B.; Lin, S.; Zhao, Y.; Tan, Y.; Li, N.; Xiu, Q.; et al. Natural Turmeric-Derived Nanovesicles-Laden Metal-Polyphenol Hydrogel Synergistically Restores Skin Barrier in Atopic Dermatitis via a Dual-Repair Strategy. Adv. Heal. Mater. 2025, 14, e2500081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, S.P.; Paolini, A.; D’Oria, V.; Sarra, A.; Sennato, S.; Bordi, F.; Masotti, A. Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Citrus sinensis Modulate Inflammatory Genes and Tight Junctions in a Human Model of Intestinal Epithelium. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 778998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Perini, G.; Minopoli, A.; Palmieri, V.; De Spirito, M.; Papi, M. Plant-derived extracellular vesicles as a natural drug delivery platform for glioblastoma therapy: A dual role in preserving endothelial integrity while modulating the tumor microenvironment. Int. J. Pharm. X 2025, 10, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miya, M.B.; Ashutosh Maulishree Dey, D.; Pathak, V.; Khare, E.; Kalani, K.; Chaturvedi, P.; Kalani, A. Accelerated diabetic wound healing using a chitosan-based nanomembrane incorporating nanovesicles from Aloe barbadensis, Azadirachta indica, and Zingiber officinale. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 310 Pt 2, 143169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savcı, Y.; Kırbaş, O.K.; Bozkurt, B.T.; Abdik, E.A.; Taşlı, P.N.; Şahin, F.; Abdik, H. Grapefruit-derived extracellular vesicles as a promising cell-free therapeutic tool for wound healing. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 5144–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Hu, Q.X.; Li, J.P.; Su, H.B.; Li, Z.Y.; He, J.; You, Q.; Yang, Y.-L.; Zhang, H.-T.; Zhao, K.-W. Morinda Officinalis-Derived Extracellular Vesicle-like Particles Promote Wound Healing via Angiogenesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 30454–30464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, E.; Yang, Y.; Cong, S.; Chen, D.; Chen, R.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, W. Lemon-derived nanoparticle-functionalized hydrogels regulate macrophage reprogramming to promote diabetic wound healing. J. Nanobiotechnology 2025, 23, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Rhee, W.J. Targeted Atherosclerosis Treatment Using Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 Targeting Peptide-Engineered Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, S.J.; Park, S.H.; Yuk, J.M.; Jeong, J.C.; Ryu, Y.B.; Kim, W.S. Multifunctional cosmetic potential of extracellular vesicle-like nanoparticles derived from the stem of Cannabis sativa in treating pigmentation disorders. Mol. Med. Rep. 2025, 31, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, T.; Morisawa, S.; Jobu, K.; Kawada, K.; Yoshioka, S.; Miyamura, M. Atractylodes lancea rhizome derived exosome-like nanoparticles prevent alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone-induced melanogenesis in B16-F10 melanoma cells. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2023, 35, 101530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, K.A.; Park, Y.; Oh, S.; Batsukh, S.; Son, K.H.; Byun, K. Co-Treatment with Phlorotannin and Extracellular Vesicles from Ecklonia cava Inhibits UV-Induced Melanogenesis. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.G.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, H.; Choi, E.J.; Lee, E.J.; Park, P.J.; Ko, J.; Kim, K.P.; Baek, H.S. Panax ginseng -Derived Extracellular Vesicles Facilitate Anti-Senescence Effects in Human Skin Cells: An Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Way to Use Ginseng Substances. Cells 2021, 10, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborowska, M.; Taulé Flores, C.; Vazirisani, F.; Shah, F.A.; Thomsen, P.; Trobos, M. Extracellular Vesicles Influence the Growth and Adhesion of Staphylococcus epidermidis Under Antimicrobial Selective Pressure. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sileo, L.; Cavaleri, M.P.; Lovatti, L.; Pezzotti, G.; Ferroni, L.; Zavan, B. Dermatologically Tested Apple-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Safety, Anti-Aging, and Soothing Benefits for Skin Health. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2025, 24, e70254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alépée, N.; Grandidier, M.H.; Tornier, C.; Cotovio, J. An integrated testing strategy for in vitro skin corrosion and irritation assessment using SkinEthic™ Reconstructed Human Epidermis. Toxicol. Vitr. 2015, 29, 1779–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsch, A.; Gerberick, G.F. Integrated skin sensitization assessment based on OECD methods (I): Deriving a point of departure for risk assessment. ALTEX 2022, 39, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritacco, G.; Hilberer, A.; Lavelle, M.; Api, A.M. Use of alternative test methods in a tiered testing approach to address photoirritation potential of fragrance materials. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2022, 129, 105098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluxen, F.M.; Grégoire, S.; Schepky, A.; Hewitt, N.J.; Klaric, M.; Domoradzki, J.Y.; Felkers, E.; Fernandes, J.; Fisher, P.; McEuen, S.F.; et al. Dermal absorption study OECD TG 428 mass balance recommendations based on the EFSA database. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 108, 104475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrz, J.; Hošíková, B.; Svobodová, L.; Očadlíková, D.; Kolářová, H.; Dvořáková, M.; Kejlová, K.; Malina, L.; Jírová, G.; Vlková, A.; et al. Comparison of methods used for evaluation of mutagenicity/genotoxicity of model chemicals-parabens. Physiol Res. 2020, 69 (Suppl. 4), S661–S679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreoli, C.; Dusinska, M.; Bossa, C.; Battistelli, C.L.; Silva, M.J.; Louro, H. Regulatory practices on the genotoxicity testing of nanomaterials and outlook for the future. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 162, 105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.; Rovida, C.; Kreiling, R.; Zhu, C.; Knudsen, M.; Hartung, T. Continuing animal tests on cosmetic ingredients for REACH in the EU. ALTEX 2021, 38, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makris, S.L.; Kim, J.H.; Ellis, A.; Faber, W.; Harrouk, W.; Lewis, J.M.; Paule, M.G.; Seed, J.; Tassinari, M.; Tyl, R. Current and future needs for developmental toxicity testing. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011, 92, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, A.; Parveen, B.; Parveen, R.; Ahmad, S. Challenges and guidelines for clinical trial of herbal drugs. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2015, 7, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J. Cosmetic Coloration: A Review. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2021, 72, 442–498. [Google Scholar]

- Rawat, S.; Arora, S.; Dhondale, M.R.; Khadilkar, M.; Kumar, S.; Agrawal, A.K. Stability Dynamics of Plant-Based Extracellular Vesicles Drug Delivery. J. Xenobiot. 2025, 15, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Park, J.; Sohn, Y.; Oh, C.E.; Park, J.H.; Yuk, J.M.; Yeon, J.-H. Stability of Plant Leaf-Derived Extracellular Vesicles According to Preservative and Storage Temperature. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelibter, S.; Marostica, G.; Mandelli, A.; Siciliani, S.; Podini, P.; Finardi, A.; Furlan, R. The impact of storage on extracellular vesicles: A systematic study. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F.; Li, Y.M.; Wang, Z. Preserving extracellular vesicles for biomedical applications: Consideration of storage stability before and after isolation. Drug Deliv. 2021, 28, 1501–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, C.; Porcello, A.; Chemali, M.; Raffoul, W.; Marques, C.; Scaletta, C.; Lourenço, K.; Abdel-Sayed, P.; Applegate, L.A.; Vatter, F.P.; et al. Medicalized Aesthetic Uses of Exosomes and Cell Culture-Conditioned Media: Opening an Advanced Care Era for Biologically Inspired Cutaneous Prejuvenation and Rejuvenation. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ahumada, A.L.; Bayraktar, E.; Schwartz, P.; Chowdhury, M.; Shi, S.; Sebastian, M.M.; Khant, H.; de Val, N.; Bayram, N.N.; et al. Enhancing oral delivery of plant-derived vesicles for colitis. J. Control Release 2023, 357, 472–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kürtösi, B.; Kazsoki, A.; Zelkó, R. A Systematic Review on Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles as Drug Delivery Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Görgens, A.; Corso, G.; Hagey, D.W.; Jawad Wiklander, R.; Gustafsson, M.O.; Felldin, U.; El Andaloussi, S. Identification of storage conditions stabilizing extracellular vesicles preparations. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2022, 11, e12238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, S.; de Beaurepaire, L.; Allard, M.; Mosser, M.; Heichette, C.; Chrétien, D.; Jegou, D.; Bach, J.-M. Trehalose prevents aggregation of exosomes and cryodamage. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; Liu, K. Plant-derived extracellular vesicles as oral drug delivery carriers. J. Control. Release 2022, 350, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nueraihemaiti, N.; Dilimulati, D.; Baishan, A.; Hailati, S.; Maihemuti, N.; Aikebaier, A.; Zhou, W. Advances in Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicle Extraction Methods and Pharmacological Effects. Biology 2025, 14, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutter, B.D.; Innes, R.W. Growing pains: Addressing the pitfalls of plant extracellular vesicle research. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Attribute | Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles | Liposomes |

|---|---|---|

| Origin/ Biogenesis | Natural vesicles secreted by plant cells via regulated pathways (endosomal/exosome-like, microvesicle shedding); Exist in vivo in tissues and diet. | Artificially engineered phospholipid vesicles assembled in vitro (thin-film hydration, ethanol injection, microfluidics). |

| Structural architecture | Lipid bilayer with complex native composition (phospholipids, sphingolipids, sterols) plus embedded proteins/glycans; Heterogeneous nano-assemblies. | Primarily phospholipid bilayer(s); Composition defined by formulation; Typically protein-free unless functionalized. |

| Cargo | Endogenous multi-omic cargo: proteins/enzymes, small RNAs (miRNA/siRNA), mRNA, metabolites (polyphenols, carotenoids, lipid mediators); Pre-loaded by biology. | No intrinsic cargo; Requires exogenous loading of active pharmaceutical ingredient (hydrophilic in core, lipophilic in membrane). |

| Surface markers | Natural ligands (proteins, lipids, glycans) enabling selective uptake and cross-kingdom signaling; Potential tissue tropism. | Lack native recognition motifs; targeting achieved via synthetic ligands such as PEG, peptides, antibodies, if added. |

| Uptake/ Targeting | Multiple routes (endocytosis, membrane fusion) with context-specific specificity; Evidence for functional delivery of RNAs/metabolites. | Primarily nonspecific endocytosis/fusion; Targeting depends on engineered surface modifications. |

| Functional bioactivity | Inherent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, barrier-reinforcing, and regenerative signals from native cargo. | Carrier itself generally inert (unless composition confers effects); Function determined by loaded actives. |

| Stability | Biological membranes with stabilizing proteins/lipids; Sensitive to storage/oxidation; Can be stabilized (lyophilization/cryoprotectants). | Stability tunable by composition (cholesterol, saturated lipids); Susceptible to leakage/aggregation without optimization. |

| Standardization/reproducibility | Sensitive to source, season, and process (for raw-derived); In vitro-derived improves consistency but remains biologically variable. | Highly reproducible once process is fixed (defined lipids, controlled assembly, tight CQA). |

| Scalability/ Manufacturing | Raw: dependent on biomass; In vitro: bioreactors with TFF or SEC; Process complexity and QC burden higher. | Scalable, modular manufacturing; Well-established unit operations and supply chains. |

| Contaminant risk | Raw: agrochemical/microbial co-isolation risk (mitigable via organic sourcing/QC). In vitro: residual media components (PGRs, antibiotics) risk. | Low intrinsic contamination risk; Residual solvents/detergents from process must be controlled. |

| Safety/ Biocompatibility | Evolutionary/dietary familiarity; Good tolerability reported; Must control contaminants and variability. | Generally safe carriers; Immunogenicity/irritation depends on lipids and surface chemistries (e.g., PEG). |

| Regulatory familiarity | Emerging category; Requires detailed characterization and provenance disclosure; Fewer precedents in cosmetics. | Well-known excipient class with established guidance; Easier to justify from CMC standpoint. |

| Customization/ Engineering | Limited direct engineering; Can modulate via source selection and elicitation; Post-isolation modification possible but delicate. | High tunability: size, charge, composition, surface ligands, stimuli-responsive designs. |

| Loading and release control | Primarily intrinsic cargo; Exogenous loading possible (electroporation, incubation) with variable efficiency. | Designed for controlled loading/release (remote loading, ion gradients, prodrug strategies). |

| Target product profile fit | Authentic, multifunctional bioactives; Ideal for ‘natural/organic’ lines and biologically rich claims. | Precise, standardized delivery vehicles; Ideal where strict uniformity and targeted delivery are required. |

| QC/ Characterization | Multi-omic fingerprints (proteomics, lipidomics, small RNAs), NTA or TRPS, functional potency assays; Broader CQA set. | Physicochemical QC (size, PDI, zeta potential), stability, release kinetics; Narrower, well-defined CQA set. |

| Key limitations | Variability (raw), contaminant control (raw/in vitro), complex analytics, scalability vs. authenticity trade-offs. | Limited intrinsic bioactivity; Potential rapid clearance and nonspecific uptake; Need for active loading and targeting. |

| Headline advantages | Nature-derived, preloaded, multimodal activity; cross-kingdom communication potential; consumer alignment with ‘natural’. | Manufacturing control, reproducibility, regulatory familiarity, precise engineering and targeting options. |

| Cosmetic use cases | Antioxidant and anti-reactive oxygen metabolites serums, barrier-repair creams, soothing and anti-redness products, regenerative and anti-aging lines. | Targeted delivery of defined actives, photostability enhancement, controlled-release formulations, sensitive-skin minimal-ingredient lines. |

| Origin | Recommended Labeling | Key Advantages | Main Limitations | Mitigation Strategies | Value Enhancement Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic (certified) raw plant material | “Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles (PDEVs) from [botanical species] (fruit/leaf/root/seed), organically cultivated (certifying body and ID), geographical origin, harvest season/year, extraction method, batch/lot ID, pesticide panel (LC-MS/MS: not detected), microbiological compliance, vesicle QC profile (size distribution, EV markers, omics fingerprint).” | Highest natural authenticity and continuity with diet (vesicles ingested with fruits/vegetables). Stress-enriched cargo: polyphenols, carotenoids, lipid mediators, stress-responsive small RNAs. Strong consumer trust due to “organic” origin. Broad functional profile: antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, barrier-supporting, regenerative. | Batch-to-batch variability (seasonality, terroir, post-harvest handling). Stability issues (oxidation of lipids/polyphenols). Possible microbial burden from raw tissues. Co-extraction of unwanted molecules (e.g., polysaccharides, proteins). | Supply-chain standardization (cultivar selection, harvest timing). Strict post-harvest SOPs (temperature, atmosphere). Controlled blending of micro-batches. Advanced QC (multi-omics, Raman, TRPS). Stabilization via lyophilization or cryoprotectants. HACCP-based microbial controls. | Publish data dossiers on antioxidant/anti-inflammatory efficacy (ROM assays, cytokine modulation). Highlight barrier reinforcement (TEER, TJ proteins). Titrate active content (polyphenols, carotenoids, lipids). Provide QR code links to full CoA and methods. Support claims with ex vivo/clinical tolerability studies. |

| Conventional (non-organic) raw plant material | “Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles (PDEVs) from [species] (tissue), conventional cultivation; origin; harvest season; extraction method; lot ID; pesticide and agrochemical residue panel (LC-/GC-MS with compound list and thresholds); detoxification/clean-up steps applied; vesicle QC profile (NTA or TRPS, EV markers).” | Wide availability of raw material. Lower production cost. Bioactivity still present (depending on natural agronomic stress exposure). | Risk of pesticide/fungicide residues incorporated into vesicles (lipophilic molecules co-partitioning in bilayers). Marked variability between batches. Lower consumer perception of “naturalness”. Potential regulatory hurdles due to xenobiotic residues. | Rigorous supplier selection (reduced pesticide input). Systematic residue screening (LC/GC-MS/MS for neonicotinoids, organophosphates, azoles, glyphosate/AMPA, carbamates, DDT derivatives). Preparative clean-up (solid-phase extraction, diafiltration). Strict acceptance thresholds. Batch-level traceability. | Demonstrate functional comparability to organic PDEVs with robust in vitro/ex vivo data. Highlight QC-driven standardization (controlled blending, validated acceptance criteria). Ensure full transparency with CoAs. Publish third-party validations and methodological white papers. |

| Origin | Recommended Labeling | Key Advantages | Main Limitations/Critical Issues | Mitigation Strategies | Value Enhancement Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDEVs from in vitro plant cell/tissue cultures (callus, suspensions, organoid-like tissues, hairy roots) | “Plant-Derived Extracellular Vesicles (PDEVs) from in vitro plant cell culture (species; cell line/callus/hairy root ID; tissue of derivation), culture mode (solid vs. suspension; bioreactor type), media class (chemically defined vs. complex), PGRs/elicitors used (names/grades), antibiotics/antifungals policy, process scale (batch/fed-batch/continuous), purification train (e.g., TFF, SEC, gradient), lot ID, residuals panel (LC/GC-MS: PGRs, antibiotics, solvents; LOQ/LOR), microbiological specs (TAMC/TYMC, endotoxin), vesicle QC (mode size, P/particle, lipid/particle, markers, omics fingerprint).” | High reproducibility and batch consistency (decoupled from season/terroir). Scalable (stirred-tank/wave bioreactors; DoE optimization). Lower risk of agrochemical residues vs. raw materials. GMP-like documentation feasible (SOPs, validation). | Biological distance from native tissues: cargo may lack stress-enriched complexity (polyphenols, carotenoids, stress-miRNAs). Residual culture components (PGRs like 2,4-D/BAP; antibiotics/antifungals; complex supplements) may co-purify. Compositional skew from dedifferentiated cells: potential shear-induced artifacts in reactors. Consumer perception: less “natural/authentic”. | Use chemically defined, antibiotic-free media and qualify suppliers (pharma-grade inputs). Implement residuals control (LC/GC-MS/MS for PGRs, antibiotics, solvents; strict acceptance <LOQ). Orthogonal purification (diafiltration and SEC and SPE for lipophiles). Control shear/oxygen/light; PAT for pH/DO; CFD-informed bioreactor settings. Identity–purity–potency matrices (TRPS/NTA; markers; Raman/lipidomics; small-RNA profiling). | Elicitation programs (JA/SA pulses, UVB/blue light, hypoxia, nutrient shifts) to re-introduce stress-enriched cargo while retaining batch control. Publish comparability data vs. raw-derived PDEVs (anti-ROM, cytokine modulation, barrier assays). Transparency narrative (cleaner xenobiotic profile; full CoA data). Develop fit-for-purpose release assays (TEER, TJ proteins, irritation/sensitization surrogates). |

| Aspect | Raw-Material: Advantages | Raw-Material: Disadvantages | In Vitro Culture: Advantages | In Vitro–Culture: Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source and definition | Isolated directly from intact plant tissues (fruit/leaf/root/seed); captures in vivo biology and stress-driven signaling. | Subject to agronomic and environmental variability; Heterogeneous tissue inputs. | Secreted by plant cells grown under controlled conditions (callus/suspensions/hairy roots/organoid-like) with defined media and PGRs. | Artificial, extra-organismic system far from native tissue context; Dedifferentiated biology. |

| Bioactive cargo profile | Stress-enriched fingerprint (polyphenols, carotenoids, lipid mediators, stress-responsive small RNAs); Dietary familiarity. | Cargo fluctuates with season/terroir/post-harvest; Potential co-extraction of undesired macromolecules. | Tunable via elicitation (JA/SA, light, hypoxia) while maintaining control; More uniform cargo distribution. | Baseline cargo may lack ecological complexity and stress signatures seen in field tissues. |

| Efficacy (cosmetic relevance) | Robust antioxidant/anti-ROM, anti-inflammatory, barrier-reinforcing and regenerative signals (when well-sourced). | Batch-to-batch potency differences; Efficacy claims harder to generalize without extensive QC. | Batch-consistent functional readouts; Amenable to fit-for-purpose release assays (TEER, cytokine modulation). | May show narrower activity spectrum unless elicited; Biological equivalence to raw not guaranteed. |

| Contaminants risk | When organic: minimal agrochemical residues; Aligns with ‘clean beauty’. | Conventional crops: risk of pesticides/fungicides (lipophilic) co-partitioning into vesicles; Microbial burden from biomass. | Lower risk of field agrochemicals; Cleaner xenobiotic profile possible. | Risk of residual media components: PGRs (2,4-D/BAP), antibiotics/antifungals, complex supplements; Shear-induced fragments. |

| Standardization and reproducibility | Authenticity and ecological legitimacy; Can be standardized with strict supply-chain control and blending. | High intrinsic variability from biology and supply chain; More demanding QC to release. | High batch-to-batch reproducibility; DoE-driven optimization; GMP-like documentation feasible. | Requires stringent control to remove culture-derived residuals; Identity may diverge from native vesicles. |

| Scalability and cost | Abundant biomass for some crops; Upcycling of by-products (peels/pomace). | Seasonal availability; Logistics/post-harvest constraints; Cost of rigorous QC and decontamination. | Continuous production in bioreactors; Predictable supply; Efficient upstream/downstream workflows. | CapEx/OpEx for bioreactors and sterile operations; Media costs; Process complexity. |

| Safety narrative and perception | Highest perceived naturalness; Continuity with diet (ingested vesicles). | Conventional residues can undermine safety perception if not rigorously screened. | Transparency on absence of agrochemicals; Traceable, controlled manufacturing. | Consumers may view as less ‘natural’; Unfamiliar vesicles from dedifferentiated cells. |

| Regulatory alignment | Organic sourcing and robust QC facilitate safety dossiers; Strong alignment with natural-origin claims. | Residue management and variability increase regulatory scrutiny; Need extensive documentation. | Process control, SOPs, acceptance criteria suit cosmetic QMS; Clear CoA framework. | Must document removal of media residuals; Justify biological relevance vs. native tissues. |

| QC and release testing | Multi-omics fingerprinting (Raman/lipidomics/miRNA), NTA/TRPS, pesticide panels (LC/GC-MS), microbiology; batch blending. | Higher analytical burden to ensure comparability across seasons/lots. | Defined residuals panels (PGRs/antibiotics/solvents), orthogonal purity assays, potency assays tailored to skin. | Complex residuals control mandatory; Orthogonal purification (diafiltration/SEC/SPE). |

| Best-fit use cases | Premium ‘natural/organic’ lines; claims built on stress-enriched bioactivity and provenance storytelling. | Products requiring extreme uniformity without blending may struggle. | Large-scale lines needing high consistency; Platforms requiring precise tech dossiers and audits. | Applications tolerant to engineered elicitation; When transparency on in vitro origin is acceptable. |

| Technique | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Apoplastic fluid recovery | Low intracellular carryover; High extracellular specificity; Good purity–integrity balance for soft tissues. | Moderate throughput; Requires dedicated setup; Less suitable for hard tissues. |

| Cold-press/juice or homogenate extraction | High feed throughput; Compatible with agro by-products (peels/pomace); Versatile across matrices. | Complex co-extracts (pectins, pigments, proteins) demand robust downstream polishing. |

| DC or sedimentation | Universal, gentle front-end; Simplifies complex fluids prior to fine separations. | Poor selectivity among nanoscale species; must be paired with selective steps. |

| Sequential microfiltration | Reduces bioburden and coarse debris; Stabilizes feed for membranes or chromatography. | Risk of fouling and retention of large EV aggregates; Pressure control needed. |

| UF and TFF | Scalable capture and buffer exchange; Low shear; Efficient removal of small solutes. | Potential non-specific adsorption; Performance sensitive to shear or transmembrane pressure control. |

| UC (pellet or cushion) | Widely available; Rapid enrichment when chromatography is limited. | Co-pellets proteins/aggregates; Possible mechanical stress on EVs. |

| Buoyant-density UC | High resolving power; Separates EVs from lipoprotein-like particles and aggregates. | Time- and equipment-intensive; Added complexity and lower throughput. |

| SEC | Gentle, low-shear polishing; Efficiently depletes proteins and polysaccharides; Preserves bioactivity. | Fraction dilution requires reconcentration; Performance depends on column and load. |

| AF4 | High-resolution, stationary-phase-free fractionation; Profiles EV subpopulations. | Specialized instrumentation; Limited preparative throughput. |

| Immunoaffinity capture | High selectivity for targeted subsets; Powerful for mechanism-driven fractions. | Limited capacity; Higher cost; Potential conflicts with clean-label claims. |

| Lectin affinity capture | Enriches glyco-defined subsets; Informative for plant-specific membrane biology. | Possible co-capture of non-vesicular glycoproteins; Requires gentle elution. |

| Heparin or GAG affinity capture | Robust, easy-to-implement orthogonal selector; Can sharpen overall purity. | Lower specificity than antibodies; Strong ionic-strength dependence. |

| Microfluidic separations | Very gentle, label-free sorting; Integrable into continuous compact pipelines. | Current throughput modest; Requires bespoke devices and know-how. |

| Polymer precipitation | High apparent recovery; Minimal setup and cost. | Low specificity; Co-precipitates proteins and polysaccharides; Generally unsuitable for premium products. |

| Parameter | Why | Techniques | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Value Target | Reporting Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle size, size distribution and concentration | Core identity of vesicular domain; affects uptake, tissue diffusion, biodistribution, and formulation behavior. | NTA (single-particle size histograms and particles/mL); DLS (hydrodynamic diameter, PDI); TRPS (single-particle size and count via nanopore). | NTA: resolves polydispersity and gives absolute counts. DLS: fast, low volume. TRPS: calibrated, high precision. | NTA: operator-sensitive; fluorescence often needed. DLS: biased by large aggregates; PDI conflates multimodality. TRPS: narrow pore ranges; per-sample optimization. | Mode/mean size: ~50–300 nm. DLS PDI: ≤0.2–0.3 (well-resolved). Working stocks: 109–1011 particles/mL (method-dependent). | Pair size with concentration; specify buffer/temperature; Disclose isolation (e.g., clarify with TFF capture followed by SEC polish with or without gradient or AF4). |

| Morphology and membrane integrity | Confirms vesicular architecture; Excludes non-vesicular colloids and aggregates. | TEM (negative stain); Cryo-TEM (vitrified, near-native). | TEM: high contrast, throughput. Cryo-TEM: preserves native morphology. | TEM: dehydration artifacts (cup shape). Cryo-TEM: lower contrast, higher expertise/instrument burden. | TEM: spherical/ovoid vesicles with intact bilayer, minimal debris; Cryo-TEM: Absence of crystalline/precipitate artifacts. | Use imaging to corroborate sizing data; Include representative micrographs and prep conditions. |

| Zeta (ζ) potential and surface electrokinetics | Proxy for surface charge and colloidal stability; Influences aggregation, interfacial interactions, excipient compatibility. | ELS/LDV; TRPS-derived zeta (mobility-based). | ELS/LDV: standardized, fast. TRPS-zeta: single-particle resolution. | ELS/LDV: strongly buffer-dependent (pH/ionic strength), sensitive to contaminants. TRPS: narrow dynamic window, pore calibration needed. | Typically −10 to −30 mV in low-salt, near-neutral buffers. | Always report pH, ionic strength, temperature, interpret shifts with formulation changes. |

| Protein content and purity indices | Contextualizes yield and co-purified solubles; Supports batch comparability. | BCA/micro-BCA (total protein); Particle-to-protein ratio (NTA/TRPS ÷ protein); SDS-PAGE; LC-MS/MS proteomics. | BCA: robust, simple. Particle-to-protein: quick purity proxy. SDS-PAGE and LC-MS: fingerprints cargo vs. contaminants. | BCA: totals vesicular and non-vesicular proteins. Particle-to-protein: no universal cutoff. Omics: higher analytical overhead. | Higher particle-to-protein ratios indicate cleaner preps (no single gold value—benchmark vs. your TFF or SEC lots). | Report assay, standards, linearity; Compare ratios across lots; Include representative gel/omics profiles. |

| Minimal “EV vs. lipid vesicle” differentiation (physical layer) | Support bona fide EV claim vs. empty/synthetic lipid particles. | Concordant EV size domain with TEM/Cryo-TEM bilayer; Physical/biochemical cargo evidence (endogenous macromolecules); ζ-potential consistent with membranes. | Orthogonal, non-invasive, foundational for identity. | Not sufficient alone: must be integrated with biochemical markers and functional assays. | EV-like size; Intact bilayer; ζ within stable window; Endogenous macromolecules present. | State that physical identity is the minimum layer; follow with marker panels and functional tests. |

| Formulation-relevant physicochemical parameters | Ensure safety/compatibility and preserve vesicle structure within the vehicle. | pH (meter); Osmolality (osmometer); Viscosity/rheology (rotational); Optionally surface tension. | Straightforward QC; Informs excipient optimization. | Excipients can drift values over time; Stability monitoring required. | Skin-compatible pH ~4.5–6.5; Osmolality/viscosity tuned to vehicle (e.g., gels, serums). | Report pre- and post-spike values (after EV addition), assess under ICH-like conditions. |

| Stability and storage (physical QA) | Verify that size/ζ/morphology remain within acceptance criteria across shelf life. | Time-course NTA/DLS; ζ-tracking; repeat TEM/Cryo-TEM; stress tests (freeze–thaw, agitation, thermal). | Anticipates failure modes; supports label claims. | Added testing burden; container/extractables can confound. | No universal cutoffs—define lot-specific specs (e.g., Δ size, Δ ζ thresholds). | Prefer cold chain; Consider trehalose for frozen stocks; Avoid repeated freeze–thaw; Specify container/closure system. |

| Documentation and transparency | Enable reproducibility, comparability, and regulatory review. | Full source and process disclosure; unified analytics across lots; controlled blending if used. | Builds trust; facilitates audits and tech transfer. | Under-reporting undermines claims. | — | Disclose species/tissue: organic vs. conventional vs. in vitro; Isolation train (e.g., clarify with TFF capture followed by SEC polish with or without gradient or AF4); Buffer/pH/ionic strength; Storage; Define acceptance criteria for size/PDI, ζ, particle-to-protein, morphology. |

| Class | Markers to Target | Assay/Readout | Rationale | Notes/Acceptance Logic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids: membrane hallmarks | Phytosterols: β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol; Sphingolipids: glycosylceramides, GIPCs; Phospholipids: PC, PE, PA, PI; Galactolipids: MGDG, DGDG (context-dependent) | LC-MS/MS (shotgun or targeted) for class/species quantification; ratios (PA/PC/PE); presence/absence of sphingomyelin. | Plant-specific membrane chemistry supports vesicular lineage; Phytosterols/GIPCs and PA-rich profiles align with plant EV biology. | Expect phytosterol/GIPC signatures and low or absent sphingomyelin; track oxidation markers and chain-length distributions for batch comparability. |

| Enriched proteins (positive markers) | Tetraspanin-like (e.g., TET8/TET13, species-dependent); Secretory/traffic (PEN1/SYP121, EXO70 isoforms); Aquaporins (PIP1/PIP2); Annexins; Heat-shock proteins (HSP70/HSP90). | SDS-PAGE/Western blot; ELISA; label-free or targeted LC-MS/MS; protease protection (with or without detergent) to map luminal vs. surface. | Recurrently detected in plant EV studies; Indicate membrane origin, secretion machinery, and stress adaptability. | Use species-aware panels; Require enrichment vs. source matrix and co-depletion of negatives. |

| Depleted proteins (negative controls) | Chloroplast: RuBisCO (RbcL/RbcS); ER: Calnexin, BiP; Mitochondria: VDAC, Cytochrome c; Nucleus: Histone H3; Cytoskeleton: Actin, Tubulin; Oil bodies: Oleosin; Peroxisome: Catalase. | Western blot; ELISA; LC-MS/MS; set depletion thresholds (absent or less compared to source). | Rules out organelle carryover and non-vesicular contaminants (e.g., oil bodies, cytoskeletal debris). | Clean PDEVs show absence or strong depletion; Persistent signals trigger process optimization (clarify by TFF, SEC, or gradient). |

| RNA cargo: identity and plausibility | Small RNAs: miR156, miR159, miR160, miR166, miR167, miR168, miR172; siRNAs; tRNA-derived fragments; mRNA fragments (contextual). | Small-RNA NGS with spike-ins; RNase protection (with or without detergent) to prove encapsulation; RT-qPCR or dPCR for sentinel miRNAs. | RNA cargo is a defining EV feature and underpins cross-kingdom signaling narratives. | Require encapsulation evidence; Report library QC and mapping; Use endogenous references or spike-ins for lot release. |

| Small-molecule bioactives: cosmetic relevance | Polyphenols: quercetin and kaempferol glycosides, catechins, chlorogenic, ferulic, and caffeic acids; Isoprenoids: carotenoids (β-carotene, lutein), tocopherols; Triterpenoids: ursolic and oleanolic acids. | LC-MS/GC-MS metabolomics (targeted/untargeted); Stability tracking across processing and storage. | Support claimed activities (antioxidant, soothing, barrier support); Often co-packaged with PDEVs. | Demonstrate retention through isolation and shelf-life; Link dose to in vitro potency (anti-ROS/ROM, cytokines, TEER). |

| Glycan features: supportive | GIPC headgroups; lectin-reactive glycan motifs (e.g., ConA, WGA, PNA species-dependent). | LC-MS for glycosphingolipids; Western blot, ELISA or bead capture for lectin. | Plants exhibit distinctive glycosylation; Supports plant membrane identity. | Lectin data are supportive, not definitive; Consider cross-reactivity and gentle elution. |

| Process/quality indices (contextual) | Particle-to-protein ratio; Lipid-per-particle; Enrichment factors for positives; Depletion factors for negatives. | Combine NTA or TRPS with BCA assay; Lipid quantification with particle counts; Define acceptance criteria in SOPs. | Quantifies purity and comparability beyond single markers. | No universal cutoffs: benchmark against your TFF and SEC (with or without gradient or AF4) platform and specific in lot-release criteria. |

| Class | Markers to Target | Assay/Readout | Rationale | Species/Tissues Examples | Acceptance Thresholds (Lot Release) | Notes/Acceptance Logic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipids: membrane hallmarks | Phytosterols (β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol); Plant sphingolipids (glycosylceramides, GIPCs); Phospholipids (PC, PE, PI, PA); Galactolipids (MGDG, DGDG, context-dependent). | LC-MS/MS (shotgun/targeted) with class/species quant; PA/PC/PE ratios; presence/absence of sphingomyelin. | Plant-specific membrane chemistry; Phytosterols/GIPCs and PA-rich profiles support plant vesicular lineage and trafficking roles. | Ginger rhizome vesicles: PA-enriched profiles; Grapefruit/grape vesicles: phytosterols and glycosylceramides recurrent; Spinach/leaf vesicles: GIPCs abundant; Tomato/fruit vesicles: galactolipids detectable depending on process. | Phytosterols and GIPCs present (≥ref lot median ± 2 SD); sphingomyelin ≤ LOD; PA/PC ratio within platform window (e.g., ref median ±20%); lipid hydroperoxides ≤ 5% of total unsaturated lipids. | Track oxidation (hydroperoxides) and chain-length distributions; compare to SEC or TFF-polished reference lots. |

| Enriched proteins (positive markers) | Tetraspanin-like (TET8/TET13, species-dependent); Secretory/traffic (PEN1/SYP121, EXO70 isoforms); Aquaporins (PIP1/PIP2); Annexins; HSP70/HSP90. | SDS-PAGE/Western blot; ELISA; LC-MS/MS (label-free/targeted); Protease protection (with or without detergent). | Recurrently detected in plant EV studies; Indicate membrane origin, secretion machinery, and stress adaptability. | Arabidopsis apoplast: TET8-like and PEN1/SYP121; Citrus peel vesicles: annexins and HSP70/90; Grape skin vesicles: PIP2 aquaporins by proteomics. | Positives enriched ≥3–5× vs. source matrix (or ≥ref median ± 2 SD); Protease protection indicates partial luminal localization for a subset. | Use species-aware panels; Evidence of enrichment should co-occur with depletion of organelle negatives. |

| Depleted proteins (negative controls) | Chloroplast: RuBisCO (RbcL/RbcS); ER: Calnexin, BiP; Mitochondria: VDAC, Cytochrome c; Nucleus: Histone H3; Cytoskeleton: Actin, Tubulin; Oil bodies: Oleosin; Peroxisome: Catalase. | Western blot; ELISA; LC-MS/MS; define depletion thresholds (absent or less compared to source). | Rules out organelle carryover and non-vesicular contaminants (oil bodies, cytoskeletal debris). | Leaf-derived: RuBisCO is common. It must be strongly depleted; Seed/fruit oils: oleosin must be absent to exclude oleosomes; Roots: VDAC/cytochrome-c flags mitochondrial leakage. | Negatives: absent or ≤10% of source-normalized signal (or ≤ref lot median ± 2 SD); oleosin not detected by Western blot or MS. | Persistent negatives trigger process optimization (clarify, TFF, SEC, or gradient); Document LOD/LOQ for each assay. |

| RNA cargo: identity and plausibility | Small RNAs: miR156, miR159, miR160, miR166, miR167, miR168, miR172; siRNAs; tRNA-derived fragments; mRNA fragments (contextual). | Small-RNA NGS with spike-ins; RNase protection (with or without detergent) to prove encapsulation; RT-qPCR or dPCR for sentinel miRNAs. | RNA cargo is a defining EV feature and underpins cross-kingdom signaling narratives. | Fruit vesicles (grape, grapefruit, orange): miR156/159/168 families; Ginger vesicles: abundant small RNAs with RNase protection; Rice/wheat apoplast: siRNAs in stress contexts. | RNase protection index ≥ 70% retention (with or without detergent control); sentinel miRNAs detected with Ct ≤ 30 (qPCR) or copies above LLOQ (dPCR); library QC within platform metrics (e.g., % adapter-dimers ≤ spec). | Report encapsulation controls; Map reads with host-matrix depletion; Set lot-release Cp/Ct windows around reference lots. |

| Small-molecule bioactives: cosmetic relevance | Polyphenols (quercetin or kaempferol glycosides; catechins; chlorogenic, ferulic, or caffeic acids); Isoprenoids (carotenoids, as β-carotene and lutein; tocopherols); Triterpenoids (ursolic or oleanolic acids). | LC-MS/GC-MS metabolomics (targeted/untargeted); Stability tracking across processing and storage. | Support claimed activities (antioxidant, soothing, barrier support); Often co-packaged with PDEVs. | Apple peel: chlorogenic acid, phloridzin, quercetin glycosides; Grapes: resveratrol and catechins; Citrus: hesperidin/naringin; Tomato: lycopene; Green tea: EGCG-family catechins. | Marker retention ≥ 70% of post-SEC baseline over intended shelf-life; Oxidation products ≤ platform threshold (e.g., ≤10% of parent area). | Tie marker levels to in vitro potency (anti-ROS/ROM, cytokines, TEER) and monitor under ICH-like stability. |

| Glycan features: supportive | GIPC headgroups; lectin-reactive motifs (ConA, WGA, PNA—species-dependent). | LC-MS for glycosphingolipids; Western blot, ELISA or bead capture for lectin. | Plants exhibit distinctive glycosylation; Supports plant membrane identity. | Arabidopsis: GIPC-rich PM mirrored in EVs; Wheat/rice EVs: WGA-reactive GlcNAc motifs; Citrus peel vesicles: lectin profiles consistent with glycosphingolipid enrichment. | Lectin enrichment factor ≥ 2× vs. buffer and non-EV fractions; Cross-reactivity assessed with negative controls. | Lectin data are supportive, not definitive; Ensure gentle elution to preserve membranes. |

| Process/quality indices (contextual) | Particle-to-protein ratio; lipid-per-particle; enrichment/depletion factors for positives/negatives. | Combine NTA or TRPS with BCA assay; lipid quantification with particle counts; define acceptance criteria in SOPs. | Quantifies purity and comparability beyond single markers. | Grape/citrus lots (TFF and SEC) show higher particle-to-protein than pelleting-only; Ginger vesicles maintain lipid-per-particle with controlled oxidation. | Particle-to-protein ≥ platform cutoff (e.g., ≥ref median ± 2 SD); Lipid-per-particle within ± 20% of reference; negatives at/below LOD. | No universal cutoffs: benchmark vs. your platform; Lock lot-release specs and document calculation methods. |

| Module | What to Include | Acceptance Thresholds | Notes/Design Details |

|---|---|---|---|