Comparative Analysis of Symbiotic Bacterial Diversity and Sublethal Effects of Nitenpyram Against Two Different Cotton Aphids

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Rearing and Insecticide

2.2. Bioassays

2.3. Sublethal Effects of Nitenpyram on Aphis gossypii and Acyrthosiphon gossypii

2.4. Determination of Symbiotic Bacteria in Aphis gossypii and Acyrthosiphon gossypii Using Nitenpyram

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Toxicity of Nitenpyram to Aphis gossypii and Acyrthosiphon gossypii

3.2. Sublethal Effects of Nitenpyram on Fecundity and Longevity of Aphis gossypii and Acyrthosiphon gossypii Parents (G0)

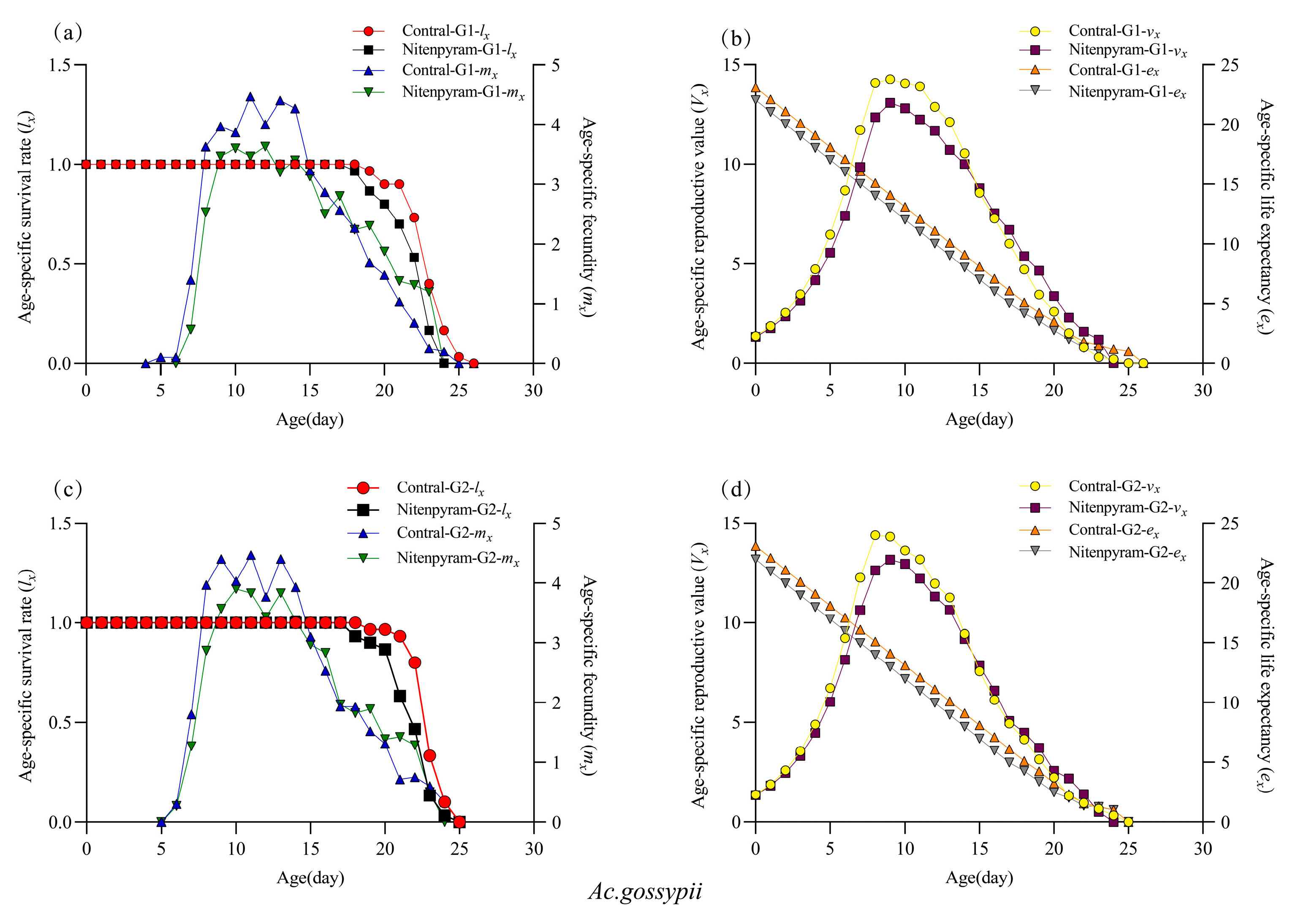

3.3. Sublethal Effects of Nitenpyram on Aphis gossypii and Acyrthosiphon gossypii, G1–G3 Generation

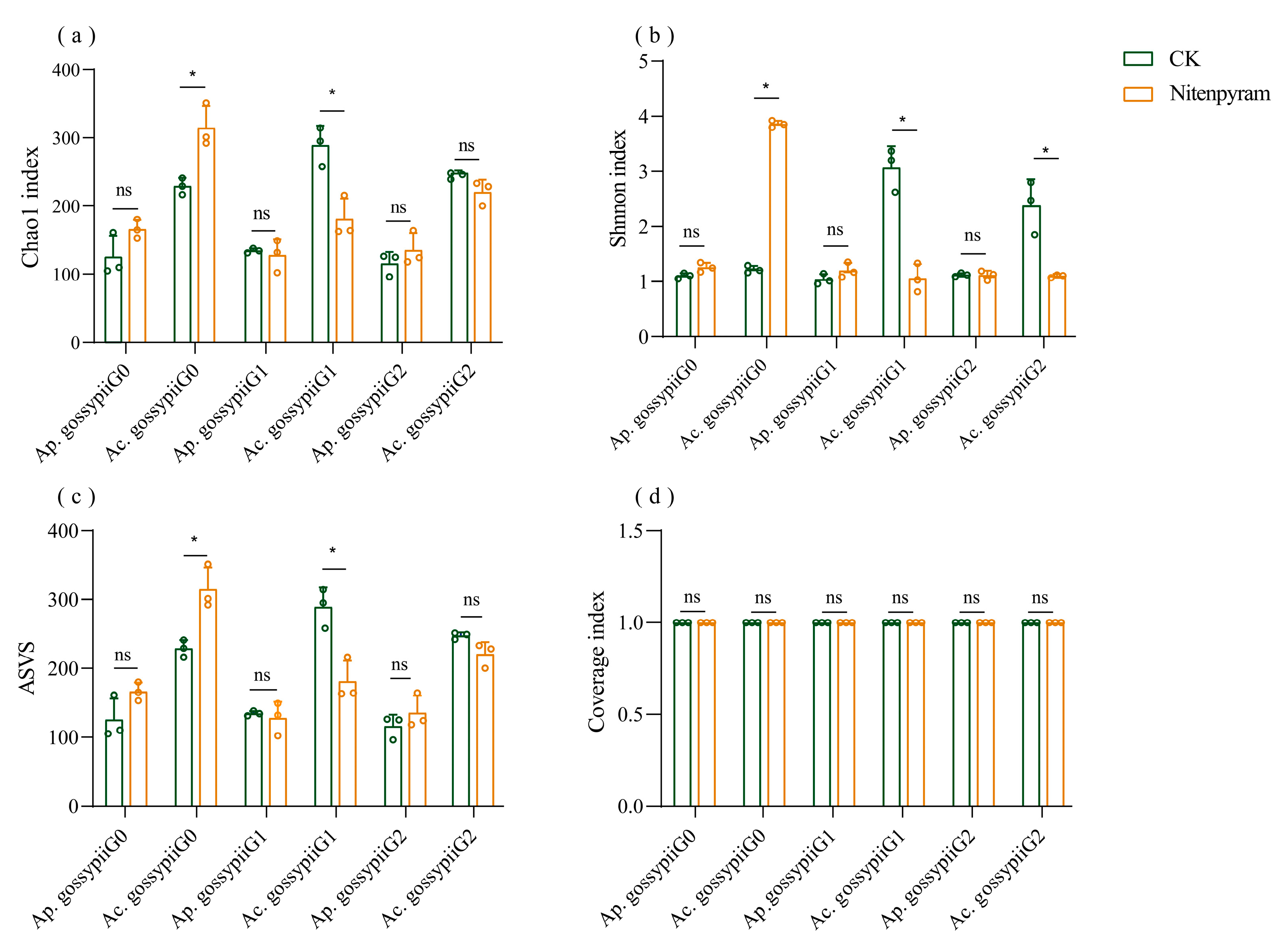

3.4. Diversity of Symbiotic Bacteria of Aphis gossypii and Acyrthosiphon gossypii Under Nitenpyram Exposure

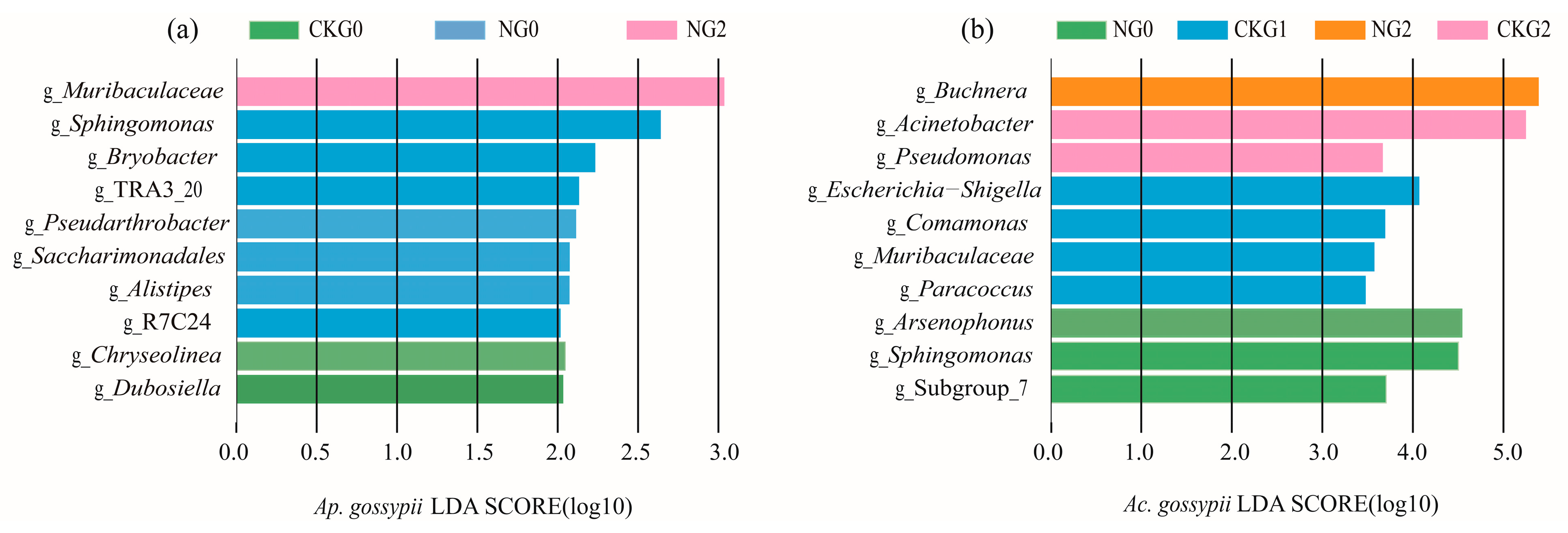

3.5. Microbial Community of Aphis gossypii and Acyrthosiphon gossypii Under Nitenpyram Exposure

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, G.Z.; Lv, Z.Z.; Sun, P.; Xia, D.P. Effects of high temperature on the mortality and fecundity of two co-existing cotton aphid species Aphis gossypii Glover and Acyrthosiphon gossypii Mordvilko. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao 2012, 23, 506–510. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W.J.; Zhu, Y.Y.; Zhang, Y.D.; Wu, N.; Zhang, Q.C.; Wang, J.G. Effect of feeding by two aphid species on the feeding behavior of Acyrthosiphon gossypii and Aphis gossypii on cotton. Plant Prot. 2024, 50, 146–151+158. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.P.; Wang, C.; Desneux, N.; Lu, Y.H. Impact of temperature on survival rate, fecundity, and feeding behavior of two aphids, Aphis gossypii and Acyrthosiphon gossypii, when reared on cotton. Insects 2021, 12, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hullé, M.; Chaubet, B.; Turpeau, E.; Simon, J.C. Encyclop’Aphid: A website on aphids and their natural enemies. Entomol. Gen. 2020, 40, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, J.; Wei, X.Z.; Wang, H.Q.; Wang, P.L. A technical regulation for integrated control of cotton aphids in Xinjiang. China Cotton 2022, 49, 38–41. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.Z.; Tian, C.Y.; Song, Y.D. Relationship between Aphis gossypii and Acyrthosiphon gossypii on cotton in Xinjiang. China Cotton 2002, 29, 11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Desneux, N.; Decourtye, A.; Delpuech, J.M. The sublethal effects of pesticides on beneficial arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2007, 52, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomizawa, M.; Casida, J.E. Selective toxicity of neonicotinoids attributable to specificity of insect and mammalian nicotinic receptors. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2003, 48, 339–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, P.; Tian, Y.A.; Biondi, A.; Desneux, N.; Gao, X.W. Short-term and transgenerational effects of the neonicotinoid nitenpyram on susceptibility to insecticides in two whitefly species. Ecotoxicology 2012, 21, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbert, A.; Haas, M.; Springer, B.; Thielert, W.; Nauen, R. Applied aspects of neonicotinoid uses in crop protection. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 1099–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.K.; Zhang, X.L.; Ali, E.; Liao, X.; Jin, R.Z.; Ren, Z.J.; Wan, H.; Li, J.H. Characterization of nitenpyram resistance in Nilaparvata lugens (Stål). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2019, 157, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, H.; Fu, B.; Tan, Q.; Hu, J.; Yang, J.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Y. Field-evolved resistance to nitenpyram is associated with fitness costs in whitefly. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 5684–5693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, N.W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.C.; Liu, Z.Y.; Song, X.Y.; Pei, X.G.; Wu, S.F.; Gao, C.F. Area-wide survey and monitoring of insecticide resistance in the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Stål), from 2020 to 2023 in China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 205, 106173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.L.; Wang, S.L.; Han, G.J.; Du, Y.Z.; Wang, J.J. Lack of cross-resistance between neonicotinoids and sulfoxaflor in field strains of Q-biotype of whitefly, Bemisia tabaci, from eastern China. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2016, 136, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Q.; Dong, Q.Q.; Wang, T.T.; Deng, D.; Ding, Y.T.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, X.D.; Ge, L.Q. Effects of sublethal concentrations of nitenpyram on resistance substances in rice and reproductive parameters of the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens. J. Plant Prot. 2024, 51, 719–730. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, C.; Wang, R. Insecticide resistance and its management in two invasive cryptic species of Bemisia tabaci in China. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puinean, A.M.; Foster, S.P.; Oliphant, L.; Denholm, I.; Field, L.M.; Millar, N.S.; Williamson, M.S.; Bass, C. Amplification of a cytochrome P450 gene is associated with resistance to neonicotinoid insecticides in the aphid Myzus persicae. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffar, S.; Ahmad, S.; Lu, Y.Y. Contribution of insect gut microbiota and their associated enzymes in insect physiology and biodegradation of pesticides. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 979383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.B.; Jiang, L.L.; Wang, H.Y.; Qiao, K.; Wang, D.; Wang, K.Y. Toxicities and sublethal effects of seven neonicotinoid insecticides on survival, growth and reproduction of imidacloprid-resistant cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 1528–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.D.; Luo, C.; Lv, H.X.; Zhang, L.; Desneux, N.; You, H.; Li, J.H.; Ullah, F.; Ma, K.S. Impact of sublethal and low lethal concentrations of flonicamid on key biological traits and population growth associated genes in melon aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. Crop Prot. 2022, 152, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.H.; Zheng, X.S.; Gao, X.W. Sublethal effects of imidacloprid on the fecundity, longevity, and enzyme activity of Sitobion avenae (Fabricius) and Rhopalosiphum padi (Linnaeus). Bull. Entomol. Res. 2016, 106, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Gul, H.; Desneux, N.; Qu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Khattak, A.M.; Gao, X.; Song, D. Acetamiprid-induced hormetic effects and vitellogenin gene (Vg) expression in the melon aphid, Aphis gossypii. Entomol. Gen. 2019, 39, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Gul, H.; Desneux, N.; Gao, X.; Song, D. Imidacloprid-induced hormesis effects on demographic traits of the melon aphid, Aphis gossypii. Entomol. Gen. 2019, 39, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Qi, Y.F.; Desneux, N.; Shi, X.Y.; Biondi, A.; Gao, X.W. Sublethal and transgenerational effects of short-term and chronic exposures to the neonicotinoid nitenpyram on the cotton aphid Aphis gossypii. J. Pest Sci. 2017, 90, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, H.; Güncan, A.; Ullah, F.; Ning, X.; Desneux, N.; Liu, X. Sublethal concentrations of thiamethoxam induce transgenerational hormesis in cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover. CABI Agric. Biosci. 2023, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jie, M.L.; Gao, Y.H.; Kuang, D.H.; Shi, Y.S.; Wang, H.H.; Jing, W.W. Relationship between imidacloprid residues and control effect on cotton aphids in arid region. Environ. Geochem. Health 2021, 43, 1941–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.L.; Fu, Z.X.; Zhu, Y.F.; Gao, X.W.; Liu, T.X.; Liang, P. Sublethal and transgenerational effects of afidopyropen on biological traits of the green peach aphid Myzus persicae (Sluzer). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 180, 104981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.D.; Su, Y.; Han, X.; Guo, W.F.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, Y.S. Evaluation of transgenerational effects of sublethal imidacloprid and diversity of symbiotic bacteria on Acyrthosiphon gossypii. Insects 2023, 14, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welte, C.U.; De Graaf, R.M.; Van den Bosch, T.J.M.; Op den Camp, H.J.; van Dam, N.M.; Jetten, M.S. Plasmids from the gut microbiome of cabbage root fly larvae encode SaxA that catalyses the conversion of the plant toxin 2-phenylethyl isothiocyanate. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 1379–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.F.; Guo, Z.J.; Riegler, M.; Liang, G.W.; Xu, Y.J. Gut symbiont enhances insecticide resistance in a significant pest, the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). Microbiome 2017, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Xue, Z.X.; Lv, S.L.; Cai, Y.H.; Zhang, L.; Gao, X.W. Corynebacterium sp. 2-TD mediated toxicity of 2-tridecanone to Helicoverpa armigera. Toxins 2022, 14, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, K.M.; Degnan, P.H.; Burke, G.R.; Moran, N.A. Facultative symbionts in aphids and the horizontal transfer of ecologically important traits. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2010, 55, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunbar, H.E.; Wilson, A.C.C.; Ferguson, N.R.; Moran, N.A. Aphid thermal tolerance is governed by a point mutation in bacterial symbionts. PLoS Biol. 2007, 5, e96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grundmann, C.O.; Guzman, J.; Vilcinskas, A.; Pupo, M.T. The insect microbiome is a vast source of bioactive small molecules. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2024, 41, 935–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, J.D.; Banks, J.E. Population-level effects of pesticides and other toxicants on arthropods. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2003, 48, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.W.; Cui, M.; Xia, L.Y.; Yu, Q.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Y. Age-stage, two-sex life tables of the predatory mite Cheyletus Malaccensis Oudemans at different temperatures. Insects 2020, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakde, A.; Patel, K.; Tayade, S. Role of life table in insect pest management-A review. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2014, 7, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.S.; Tang, Q.L.; Liang, P.Z.; Li, J.H.; Gao, X.W. A sublethal concentration of afidopyropen suppresses the population growth of the cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nossa, C.W.; Oberdorf, W.E.; Yang, L.; Aas, J.A.; Paster, B.J.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Brodie, E.L.; Malamud, D.; Poles, M.A.; Pei, Z.H. Design of 16S rRNA gene primers for 454 pyrosequencing of the human foregut microbiome. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Kavousi, A.; Gharekhani, G.; Atlihan, R.; Özgökçe, M.S.; Güncan, A.; Gökçe, A.; Smith, C.L.; Benelli, G.; Guedes, R.N.C. Advances in theory, data analysis, and application of the age-stage, two-sex life table for demographic research, biological control, and pest management. Entomol. Gen. 2023, 43, 705–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir-Maafi, M.; Chi, H.; Chen, Z.Z.; Xu, Y.Y. Innovative bootstrap-match technique for life table set up. Entomol. Gen. 2022, 42, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Güncan, A.; Kavousi, A.; Gharakhani, G.; Atlihan, R.; Özgökçe, M.S.; Shirazi, J.; Amir-Maafi, M.; Maroufpoor, M.; Taghizadeh, R. TWOSEX- MSChart: The key tool for life table research and education. Entomol. Gen. 2022, 42, 845–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.B.; Chi, H. Assessing the application of the jackknife and bootstrap techniques to the estimation of the variability of the net reproductive rate and gross reproductive rate: A case study in Bactrocera cucurbitae (Coquillettidae) (Diptera: Tephritidae). J. Agric. For. 2012, 61, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Thukral, A.K. A review on measurement of alpha diversity in biology. Agric. Res. J. 2017, 54, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Dong, F.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Y. Effects of trifluralin on the soil microbial community and functional groups involved in nitrogen cycling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 353, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.J.; Guo, L.Z.; Xue, Y.Y.; Wang, M.; Li, C.W.; Zhang, R.K.; Zhang, S.W.; Xia, X.M. Life parameters and physiological reactions of cotton aphids Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae) to sublethal concentrations of afidopyropen. Agronomy 2024, 14, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Jiang, Y.T.; Guo, T.X.; Zhang, P.; Li, X.; Kong, F.B.; Zhang, B.Z. Sublethal effects of imidacloprid on the fitness of two species of wheat aphids, Schizaphis graminum (R.) and Rhopalosiphum padi (L.). PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Q.; Lu, Z.B.; Li, L.L.; Yu, Y.; Dong, S.; Men, X.Y.; Ye, B.H. Sublethal effects of imidacloprid on the performance of the bird cherry-oat aphid Rhopalosiphum padi. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.Y.; He, Y.Q.; Wu, J.X.; Tang, Y.M.; Gu, J.T.; Ding, W.; Zhang, Y.Q. Sublethal effects of cyantraniliprole and imidacloprid on feeding behaviour and life table parameters of Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2016, 109, 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, H.N.; Lee, S.W.; Yun, S.H.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, G.H. Feeding response of the cotton aphid, Aphis gossypii, to sublethal rates of flonicamid and imidacloprid. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2015, 154, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, T.; Barsi, A.; Ducrot, V. Hormesis on life-history traits: Is there such thing as a free lunch? Ecotoxicology 2013, 22, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallqui, K.V.; Vieira, J.; Guedes, R.; Gontijo, L. Azadirachtin-induced hormesis mediating shift in fecundity-longevity trade-off in the Mexican bean weevil (Chrysomelidae: Bruchinae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2014, 107, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, J.S.; Wang, Q.Q.; Ji, X.J.; Wang, W.J.; Huang, W.L.; Rui, C.H.; Cui, L. Hormesis effects of sulfoxaflor on Aphis gossypii feeding, growth, reproduction behaviour and the related mechanisms. Sci. Tota. Environ. 2023, 872, 162240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, A.N.; Xu, L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Zhang, J.B.; Zhao, K.J.; Han, L.L. Effects of acetamiprid at low and median lethal concentrations on the development and reproduction of the soybean aphid Aphis glycines. Insects 2022, 13, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyanath, M.M.; Cutler, G.C.; Scott-Dupree, C.D.; Sibley, P.K. Transgenerational shifts in reproduction hormesis in green peach aphid exposed to low concentrations of imidacloprid. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.E. Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbioses: Aphids and their symbiotic bacteria Buchnera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1998, 43, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, J.A.; Khan, M.M.; Bamisile, B.S.; Hafeez, M.; Qasim, M.; Rasheed, M.T.; Rasheed, M.A.; Ahmad, S.; Shahid, M.I.; Xu, Y.J. Role of insect gut microbiota in pesticide degradation: A review. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 870462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.T.; Sanchez, L.G.; Fierer, N. A cross-taxon analysis of insect-associated bacterial diversity. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, R.; Charnley, K. Mutualism between the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria and its gut microbiota. Res. Microbiol. 2002, 153, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.H.; Berdy, B.M.; Velasquez, O.; Jovanovic, N.; Alkhalifa, S.; Minbiole, K.P.; Brucker, R.M. Changes in microbiome confer multigenerational host resistance after sub-toxic pesticide exposure. Cell Host Microbe. 2020, 27, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.H.; Cheng, S.Y.; Desneux, N.; Gao, X.W.; Xiu, X.J.; Wang, F.L.; Hou, M.L. Transgenerational hormesis effects of nitenpyram on fitness and insecticide tolerance/resistance of Nilaparvata lugens. J. Pest Sci. 2023, 96, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.K.; Gong, Y.J.; Chen, J.C.; Shi, P.; Cao, L.J.; Yang, Q.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Wei, S.J. Increased density of endosymbiotic Buchnera related to pesticide resistance in yellow morph of melon aphid. J. Pest Sci. 2020, 93, 1281–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Yao, Y.S.; Chen, L.L.; Zhu, X.Z.; Niu, L.; Gao, X.K.; Luo, J.Y.; Ji, J.C.; Cui, J.J. Sublethal exposure to deltamethrin stimulates reproduction and alters symbiotic bacteria in Aphis gossypii. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 15097–15107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.F.; Ren, Y.J.; Chen, J.C.; Cao, L.J.; Qiao, G.H.; Zong, S.X.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Wei, S.J.; Yang, Q. Effects of fungicides on fitness and Buchnera endosymbiont density in Aphis gossypii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 4282–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A.C.; Ashton, P.D.; Calevro, F.; Charles, H.; Colella, S.; Febvay, G.; Jander, G.; Kushlan, P.F.; Macdonald, S.J.; Schwartz, J.F.; et al. Genomic insight into the amino acid relations of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum, with its symbiotic bacterium Buchnera aphidicola. Insect Mol. Biol. 2010, 19, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, A.E. Multiorganismal insects: Diversity and function of resident microorganisms. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015, 60, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koskinen, R.; Ali-Vehmas, T.; Kämpfer, P.; Laurikkala, M.; Tsitko, I.; Kostyal, E.; Atroshi, F.; Salkinoja-Salonen, M. Characterisation of Sphingomonas isolates from Finnish and Swedish drinking water distribution systems. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 89, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Zhan, R.L.; He, Z.Q. First report of bacterial dry rot of mango caused by Sphingomonas sanguinis in China. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahal, A.G.; Moussa, L.A. Degradation of 2, 4, 6-trinitrotoluene (TNT) by soil bacteria isolated from TNT contaminated soil. Aus. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bending, G.D.; Lincoln, S.D.; Sørensen, S.R.; Morgan, J.A.W.; Aamand, J.; Walker, A. In-field spatial variability in the degradation of the phenyl- urea herbicide isoproturon is the result of interactions between degradative Sphingomonas spp. and soil pH. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 827–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Masai, E.; Kitayama, H.; Harada, K.; Katayama, Y.; Fukuda, M. Characterisation of the 5-carboxyvanillate decarboxylase gene and its role in lignin-related biphenyl catabolism in Sphingomonas paucimobilis SYK-6. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 4407–4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miethling, R.; Karlson, U. Accelerated mineralization of pentachlorophenol in soil upon inoculation with Mycobacterium chlorophenolicum PCP1 and Sphingomonas chlorophenolica RA2. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 4361–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Lv, S.L.; Hu, M.F.; Yang, Z.Y.; Xiao, Y.Y.; Wang, X.G.; Liang, P.; Zhang, L. Sphingomonas bacteria could serve as an early bioindicator for the development of chlorantraniliprole resistance in Spodoptera frugiperda. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 201, 105891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, N.N.; Li, R.; Cheng, S.H.; Zhang, L.; Liang, P.; Gao, X.W. The gut symbiont Sphingomonas mediates imidacloprid resistance in the important agricultural pest Aphis gossypii Glover. BMC Biol. 2023, 21, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, J.; Dua, A.; Saxena, A.; Sangwan, N.; Mukherjee, U.; Pandey, N.; Rajagopal, R.; Khurana, P.; Khurana, J.P.; Lal, R. Genome sequence of Acinetobacter sp. strain HA, isolated from the gut of the polyphagous insect pest Helicoverpa armigera. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Insecticides | Aphid Species | LC20 (mg-L−1) (95%CL) | LC50 (mg-L−1) (95%CL) | Slope ± SE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitenpyram | Ap. gossypii | 8.73 (6.04–11.49) | 28.62 (22.50–37.64) | 2.34 ± 0.26 | 0.98 |

| Ac. gossypii | 2.49 (0.78–4.31) | 10.12 (6.34–17.08) | 1.41 ± 0.31 | 0.98 |

| Parameters | Ap. gossypii-G1 | Ac. gossypii-G1 | Ap. gossypii-G2 | Ac. gossypii-G2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | Nitenpyram | p | CK | Nitenpyram | p | CK | Nitenpyram | p | CK | Nitenpyram | p | |

| APOP | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 0.009 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | <0.001 | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 0.20 ± 0.07 | 0.046 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.690 |

| TPOP | 6.20 ± 0.18 | 5.93 ± 0.13 | 0.260 | 7.40 ± 0.14 | 8.03 ± 0.12 | <0.001 | 6.30 ± 0.13 | 6.10 ± 0.11 | 0.231 | 7.17 ± 0.11 | 7.70 ± 0.14 | 0.004 |

| Longevity | 21.87 ± 0.47 | 20.93 ± 0.23 | 0.072 | 23.10 ± 0.28 | 22.03 ± 0.31 | 0.012 | 21.53 ± 0.42 | 21.87 ± 0.44 | 0.595 | 23.10 ± 0.22 | 21.97 ± 0.30 | 0.002 |

| Fecundity | 53.00 ± 2.03 | 58.40 ± 0.98 | 0.017 | 45.67 ± 1.10 | 39.83 ± 1.20 | <0.001 | 49.37 ± 1.92 | 55.07 ± 1.80 | 0.032 | 44.80 ± 0.99 | 40.27 ± 1.03 | 0.001 |

| R0 | 53.00 ± 2.03 | 58.40 ± 0.98 | 0.017 | 45.67 ± 1.10 | 39.83 ± 1.20 | <0.001 | 49.37 ±1.92 | 55.07 ± 1.80 | 0.032 | 44.80 ± 0.99 | 40.27 ± 1.03 | 0.001 |

| rm | 0.36 ± 0.007 | 0.38 ± 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.31 ± 0.004 | 0.29 ± 0.004 | <0.001 | 0.35 ± 0.005 | 0.37 ± 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.32 ± 0.004 | 0.30 ± 0.005 | 0.006 |

| λ | 1.43 ± 0.011 | 1.46 ± 0.008 | 0.021 | 1.36 ± 0.006 | 1.33 ± 0.005 | <0.001 | 1.42 ± 0.007 | 1.44 ± 0.007 | 0.013 | 1.37 ± 0.006 | 1.35 ± 0.007 | 0.006 |

| T | 11.03 ± 0.26 | 10.69 ± 0.16 | 0.256 | 12.29 ± 0.19 | 12.88 ± 0.15 | 0.015 | 11.22 ± 0.17 | 10.98 ± 0.17 | 0.315 | 11.97 ± 0.16 | 12.34 ± 0.19 | 0.133 |

| Parameters | Ap. gossypii-G3 | Ac. gossypii-G3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CK | Nitenpyram | p | CK | Nitenpyram | p | |

| APOP | 0.33 ± 0.09 | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 0.671 | 0.07 ± 0.05 | 0.10 ± 0.05 | 0.810 |

| TPOP | 6.17 ± 0.13 | 6.13 ± 0.18 | 0.940 | 7.47 ± 0.12 | 7.20 ± 0.17 | 0.210 |

| Longevity | 22.03 ± 0.54 | 19.90 ± 0.44 | 0.003 | 22.13 ± 0.25 | 22.87 ± 0.25 | 0.044 |

| Fecundity | 54.70 ± 2.29 | 57.30 ± 1.70 | 0.361 | 43.17 ± 1.23 | 44.63 ± 0.90 | 0.337 |

| R0 | 54.70 ± 2.29 | 57.30 ± 1.70 | 0.361 | 43.17 ± 1.23 | 44.63 ± 0.90 | 0.337 |

| rm | 0.37 ± 0.005 | 0.38 ± 0.009 | 0.286 | 0.31 ± 0.004 | 0.32 ± 0.005 | 0.070 |

| λ | 1.44 ± 0.007 | 1.46 ± 0.013 | 0.286 | 1.36 ± 0.006 | 1.38 ± 0.007 | 0.070 |

| T | 10.92 ± 0.17 | 10.72 ± 0.23 | 0.500 | 12.26 ± 0.17 | 11.90 ± 0.19 | 0.158 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Cao, W.; Wei, X.; Hu, D.; Yuan, K.; Zhang, R.; Yao, Y. Comparative Analysis of Symbiotic Bacterial Diversity and Sublethal Effects of Nitenpyram Against Two Different Cotton Aphids. Biology 2025, 14, 1684. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121684

Li W, Cao W, Wei X, Hu D, Yuan K, Zhang R, Yao Y. Comparative Analysis of Symbiotic Bacterial Diversity and Sublethal Effects of Nitenpyram Against Two Different Cotton Aphids. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1684. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121684

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wenjie, Wei Cao, Xuanling Wei, Dongsheng Hu, Kailong Yuan, Renfu Zhang, and Yongsheng Yao. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of Symbiotic Bacterial Diversity and Sublethal Effects of Nitenpyram Against Two Different Cotton Aphids" Biology 14, no. 12: 1684. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121684

APA StyleLi, W., Cao, W., Wei, X., Hu, D., Yuan, K., Zhang, R., & Yao, Y. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Symbiotic Bacterial Diversity and Sublethal Effects of Nitenpyram Against Two Different Cotton Aphids. Biology, 14(12), 1684. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121684