Proteomic Analysis of Liver Injury Induced by Deoxynivalenol in Piglets

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Protein Extraction

2.3. Protein Sample Preparation, Digestion, and Peptide Clean-Up

2.4. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis

2.5. Database Search

2.6. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.7. Western Blot (WB) Analysis

2.8. Elisa Analysis

3. Results

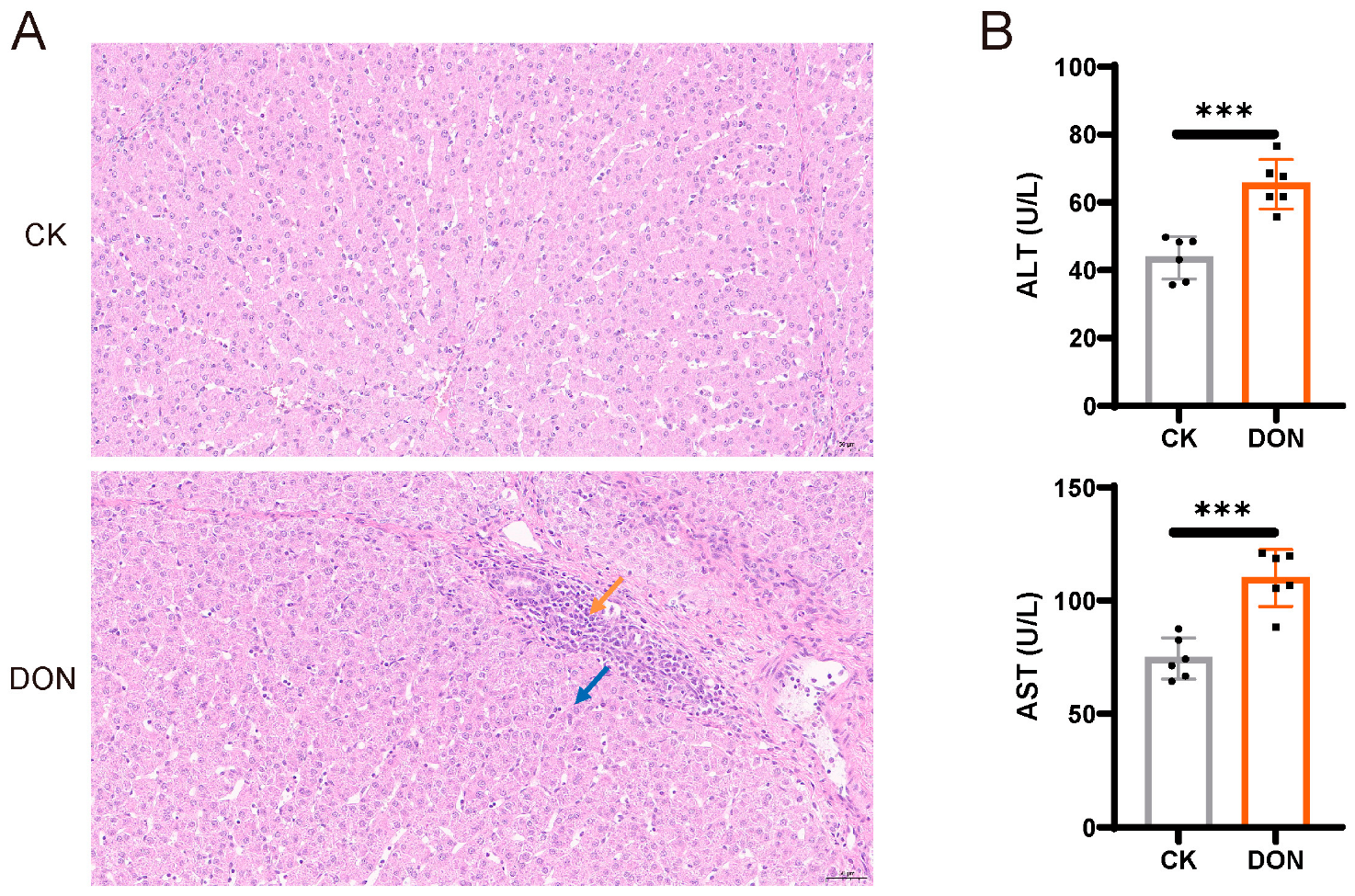

3.1. DON Treatment Causes Porcine Liver Injury

3.2. Protein Identification Using LC-MS/MS

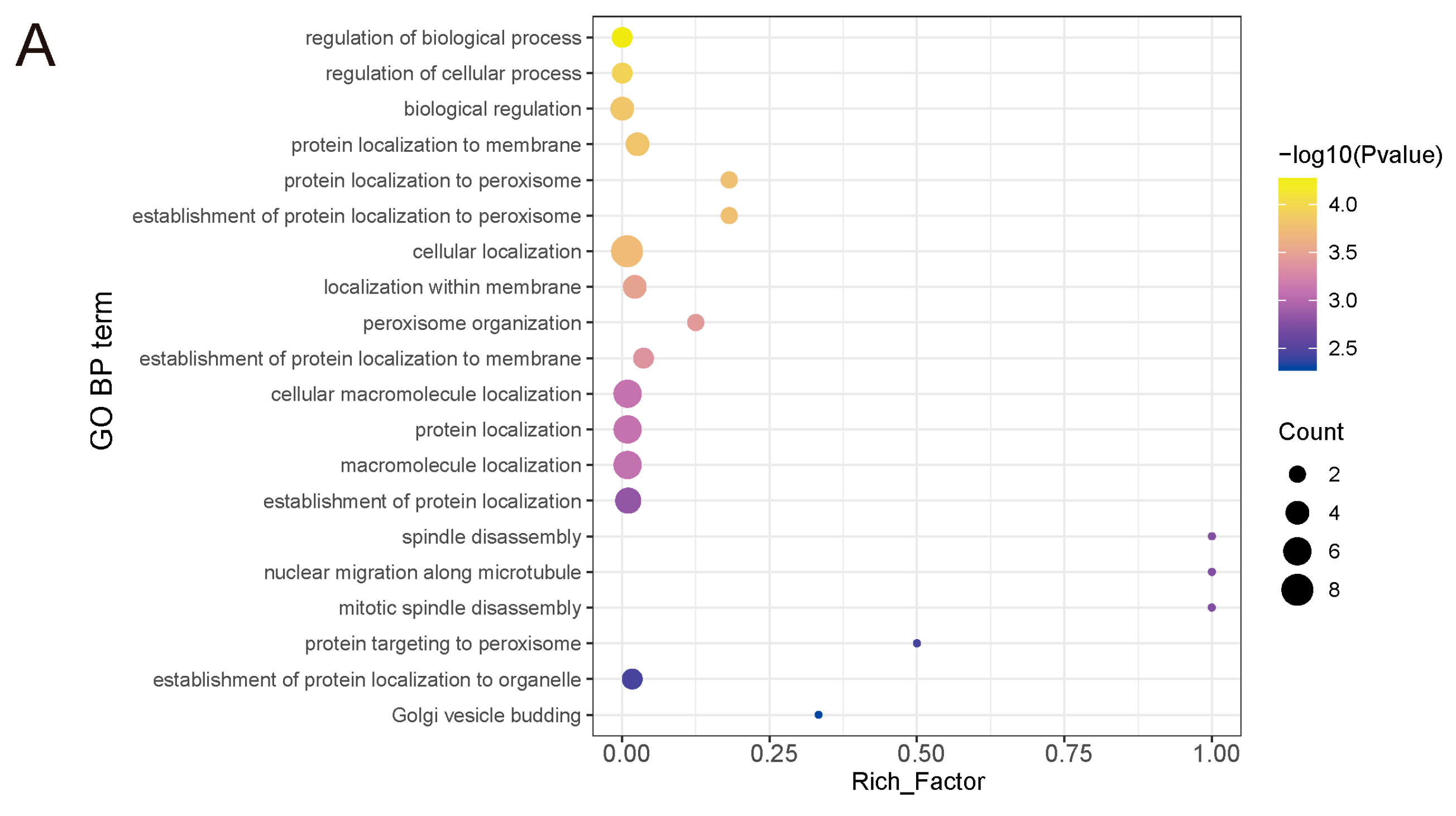

3.3. DON-Exposed Interfered Protein Expression in Liver

3.4. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Analysis

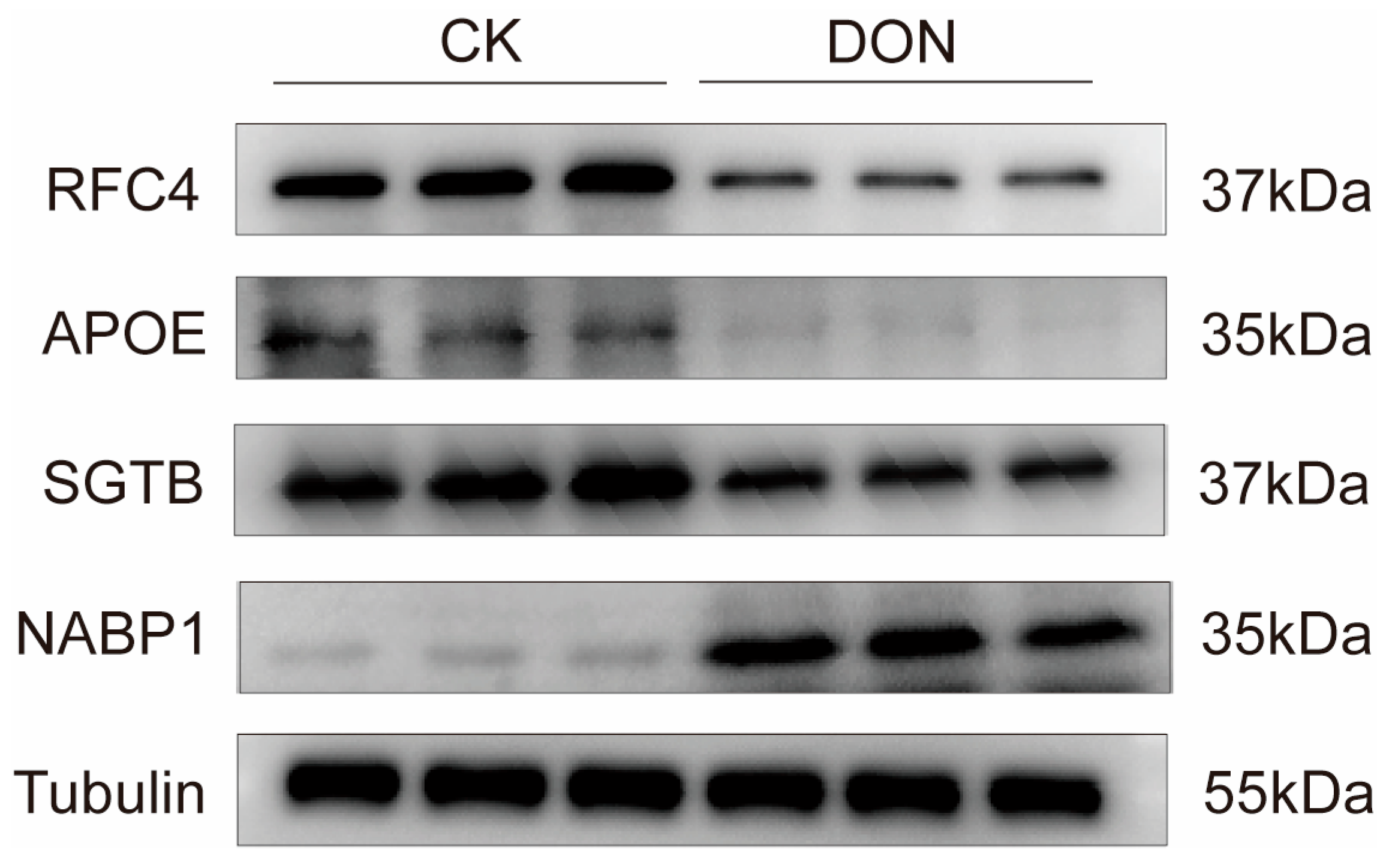

3.5. Western Blot (WB) Validation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, R.; Xu, Q. Deoxynivalenol in Food and Feed: Recent Advances in Decontamination Strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1141378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waché, Y.J.; Valat, C.; Postollec, G.; Bougeard, S.; Burel, C.; Oswald, I.P.; Fravalo, P. Impact of Deoxynivalenol on the Intestinal Microflora of Pigs. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2009, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alizadeh, A.; Braber, S.; Akbari, P.; Garssen, J.; Fink-Gremmels, J. Deoxynivalenol Impairs Weight Gain and Affects Markers of Gut Health after Low-Dose, Short-Term Exposure of Growing Pigs. Toxins 2015, 7, 2071–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Ji, J.; Wang, J.-S.; Sun, X. Deoxynivalenol: Masked Forms, Fate During Food Processing, and Potential Biological Remedies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 895–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, J.; Chen, B.; Rao, J. Occurrence and Preventive Strategies to Control Mycotoxins in Cereal-Based Food. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 928–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Xin, W.; Jiang, J.; Shan, A.; Ma, J. Low-Dose Deoxynivalenol Exposure Inhibits Hepatic Mitophagy and Hesperidin Reverses This Phenomenon by Activating Sirt1. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 468, 133854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Dai, J.; Karrow, N.A.; Sun, L. Occurrence of Aflatoxin B1, Deoxynivalenol and Zearalenone in Feeds in China During 2018–2020. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; He, Q.; Tang, Y.; Liu, H.; Su, Y.; Yin, Y.; Liao, P. Aflatoxin B1, Zearalenone and Deoxynivalenol in Feed Ingredients and Complete Feed from Different Province in China. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthiller, F.; Crews, C.; Dall’Asta, C.; Saeger, S.D.; Haesaert, G.; Karlovsky, P.; Oswald, I.P.; Seefelder, W.; Speijers, G.; Stroka, J. Masked Mycotoxins: A Review. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 57, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumarah, M.W. The Deoxynivalenol Challenge. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9619–9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feizollahi, E.; Roopesh, M.S. Mechanisms of Deoxynivalenol (Don) Degradation During Different Treatments: A Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 5903–5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, Y.; Sakai, E.; Sato, K.; Sugiyama, E.; Mima, K.; Taneno, A.; Shimomura, H.; Cui, L.; Hirai, Y. Erratum: Author Correction: Induction of Mucosal Humoral Immunity by Subcutaneous Injection of an Oil-Emulsion Vaccine against Salmonella Enterica Subsp. Enterica Serovar Enteritidis in Chickens. Food Saf. 2019, 7, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, D.K.; Kang, J.I.; Bajpai, V.K.; Kim, K.; Lee, H.; Sonwal, S.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Xiao, J.; Ali, S.; Huh, Y.S.; et al. Mycotoxins in Food and Feed: Toxicity, Preventive Challenges, and Advanced Detection Techniques for Associated Diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 63, 8489–8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.-N.; Tang, M.; Nüssler, A.K.; Liu, L.; Yang, W. Regulation of Pvt-Cea Circuit in Deoxynivalenol-Induced Anorexia and Aversive-Like Emotions. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2417068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, L.; Mo, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Karrow, N.A.; Wu, H.; Sun, L. Ferroptosis Is Involved in Deoxynivalenol-Induced Intestinal Damage in Pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 14, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofalo, M.; Payros, D.; Taieb, F.; Oswald, E.; Nougayrède, J.-P.; Oswald, I.P. From Ribosome to Ribotoxins: Understanding the Toxicity of Deoxynivalenol and Shiga Toxin, Two Food Borne Toxins. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 65, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhou, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Ruan, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, J. 18β-Glycyrrhetinic Acid Protects against Deoxynivalenol-Induced Liver Injury Via Modulating Ferritinophagy and Mitochondrial Quality Control. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 471, 134319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Ruan, Y.; Liu, X.; Ma, J.; Chen, H. Ferritinophagy Is Critical for Deoxynivalenol-Induced Liver Injury in Mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 6660–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasuda, A.L.; Person, E.; Khoshal, A.K.; Bruel, S.; Puel, S.; Oswald, I.P.; Bracarense, A.P.F.R.L.; Pinton, P. Deoxynivalenol Induces Apoptosis and Inflammation in the Liver: Analysis Using Precision-Cut Liver Slices. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 163, 112930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Ye, Y.; Ji, J.; Wang, J.-S.; Huang, Z.; Sun, J.; Sheng, L.; Sun, X. Pi3k/Akt/Foxo Pathway Mediates Antagonistic Toxicity in Hepg2 Cells Coexposed to Deoxynivalenol and Enniatins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 8214–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Q.; Li, K.; Qu, H.; Hu, P.; Xu, C.; Wang, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.-Y.; Cai, D.; et al. Sodium Butyrate Ameliorates Deoxynivalenol-Induced Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Porcine Liver Via Nr4a2-Mediated Histone Acetylation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 10427–10437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, M.; Lin, S.; Jian, R.; Li, X.; Chan, J.; Dong, G.; Fang, H.; Robinson, A.E.; Snyder, M.P. A Quantitative Proteome Map of the Human Body. Cell 2020, 183, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB13078-2017; Hygienical Standard for Feeds. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China and Chinese National Committee on Standardization: Beijing, China, 2017.

- National Research Council. Nutrient Requirements of Swine; NRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T39235-2020; Nutrient requirements of swine. National Market Supervision Administration and China National Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2020.

- Fan, S.; Guan, J.; Tian, F.; Ye, H.; Wang, Q.; Lv, L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, X. Global Profiling of Protein Β-Hydroxybutyrylome in Porcine Liver. Biology 2025, 14, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhou, R.; Yin, Z.; Ren, D.; Fan, S. Role of Ferroptosis in the Redox Biology of Mycotoxins. FASEB J. 2025, 39, e70916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Solano, B.; Lizarraga Pérez, E.; González-Peñas, E. Monitoring Mycotoxin Exposure in Food-Producing Animals (Cattle, Pig, Poultry, and Sheep). Toxins 2024, 16, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, M.; Yan, M.; Chu, X.; Li, Y. Identification of DNA Repair-Related Genes Predicting Pathogenesis and Prognosis for Liver Cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Xie, X. Rfc4 Promotes the Progression and Growth of Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma in vivo and vitro. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2021, 35, e23761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, Q.; Song, T. Replication Factor C4 in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Potent Prognostic Factor Associated with Cell Proliferation. Biosci. Trends 2021, 15, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, M.; Kondoh, N.; Imazeki, N.; Hada, A.; Hatsuse, K.; Matsubara, O.; Yamamoto, M. The Knockdown of Endogenous Replication Factor C4 Decreases the Growth and Enhances the Chemosensitivity of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Liver Int. 2008, 29, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasken, M.B.; Morton, D.J.; Kuiper, E.G.; Jones, S.K.; Leung, S.W.; Corbett, A.H. The Rna Exosome and Human Disease. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2062, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, R.; Palo, A.; Dixit, M. Role of Frg1 in Predicting the Overall Survivability in Cancers Using Multivariate Based Optimal Model. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.S.; Beak, J.Y.; Kim, Y.-S.; Petrovich, R.M.; Collins, J.B.; Grissom, S.F.; Jetten, A.M. Nabp1, a Novel Rorgamma-Regulated Gene Encoding a Single-Stranded Nucleic-Acid-Binding Protein. Biochem. J. 2006, 397, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cao, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, S.; Liu, Y.; Liang, R.; Zhu, R.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Sun, Y. Enhanced Interactions within Microenvironment Accelerates Dismal Prognosis in Hbv-Related Hcc after Tace. Hepatol. Commun. 2024, 8, e0548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Q.; Yu, Q.; Lu, S.; Yang, M.; Fan, X.; Su, H.; Kong, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wang, R.; Lv, Z. The Inhibition of Zc3h13 Attenuates G2/M Arrest and Apoptosis by Alleviating Nabp1 M6a Modification in Cisplatin-Induced Acute Kidney Injury. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.; Zeng, X.; Wang, H.; Tan, X.; Tian, Y.; Hu, H.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Sethi, G.; Huang, H.; Duan, C. Pgc-1α Loss Promotes Mitochondrial Protein Lactylation in Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury Via the Ldhb-Lactate Axis. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 205, 107228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, J.; Zhu, Z.; Mao, Q.; Xu, Z.; Singh, P.K.; Rimayi, C.C.; Moreno-Yruela, C.; Xu, S.; Li, G.; et al. Lysine L-Lactylation Is the Dominant Lactylation Isomer Induced by Glycolysis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2025, 21, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lin, X.; Fu, X.; An, Y.; Zou, Y.; Wang, J.-X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, T. Lactate Metabolism in Human Health and Disease. Signal. Transduct. Target Ther. 2022, 7, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, S.; Kong, C.; Zhou, R.; Zheng, X.; Ren, D.; Yin, Z. Protein Post-Translational Modifications Based on Proteomics: A Potential Regulatory Role in Animal Science. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 6077–6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.; Salwan, R.; Sharma, P.N.; Gulati, A. Integrated Translatome and Proteome: Approach for Accurate Portraying of Widespread Multifunctional Aspects of Trichoderma. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, Biology and Role in Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xue, X.; Wu, P.; Fan, S.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, X. Proteomic Analysis of Liver Injury Induced by Deoxynivalenol in Piglets. Biology 2025, 14, 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121721

Xue X, Wu P, Fan S, Yin Z, Zhang X. Proteomic Analysis of Liver Injury Induced by Deoxynivalenol in Piglets. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121721

Chicago/Turabian StyleXue, Xiaoshu, Ping Wu, Shuhao Fan, Zongjun Yin, and Xiaodong Zhang. 2025. "Proteomic Analysis of Liver Injury Induced by Deoxynivalenol in Piglets" Biology 14, no. 12: 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121721

APA StyleXue, X., Wu, P., Fan, S., Yin, Z., & Zhang, X. (2025). Proteomic Analysis of Liver Injury Induced by Deoxynivalenol in Piglets. Biology, 14(12), 1721. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121721