Effect of Nd:YAG Nanosecond Laser Ablation on the Microstructure and Surface Properties of Coated Hardmetals

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

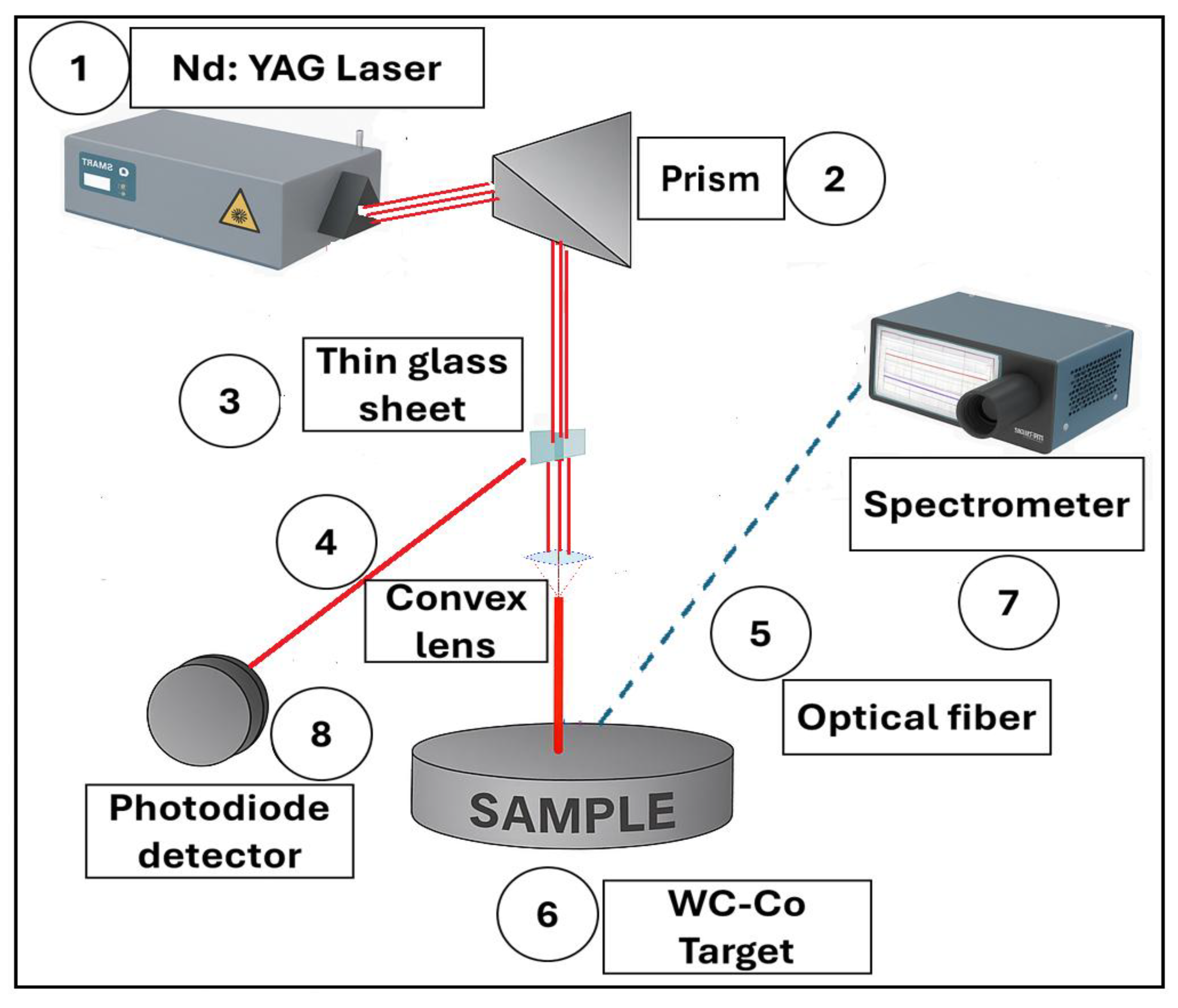

2.2. Experimental Procedure

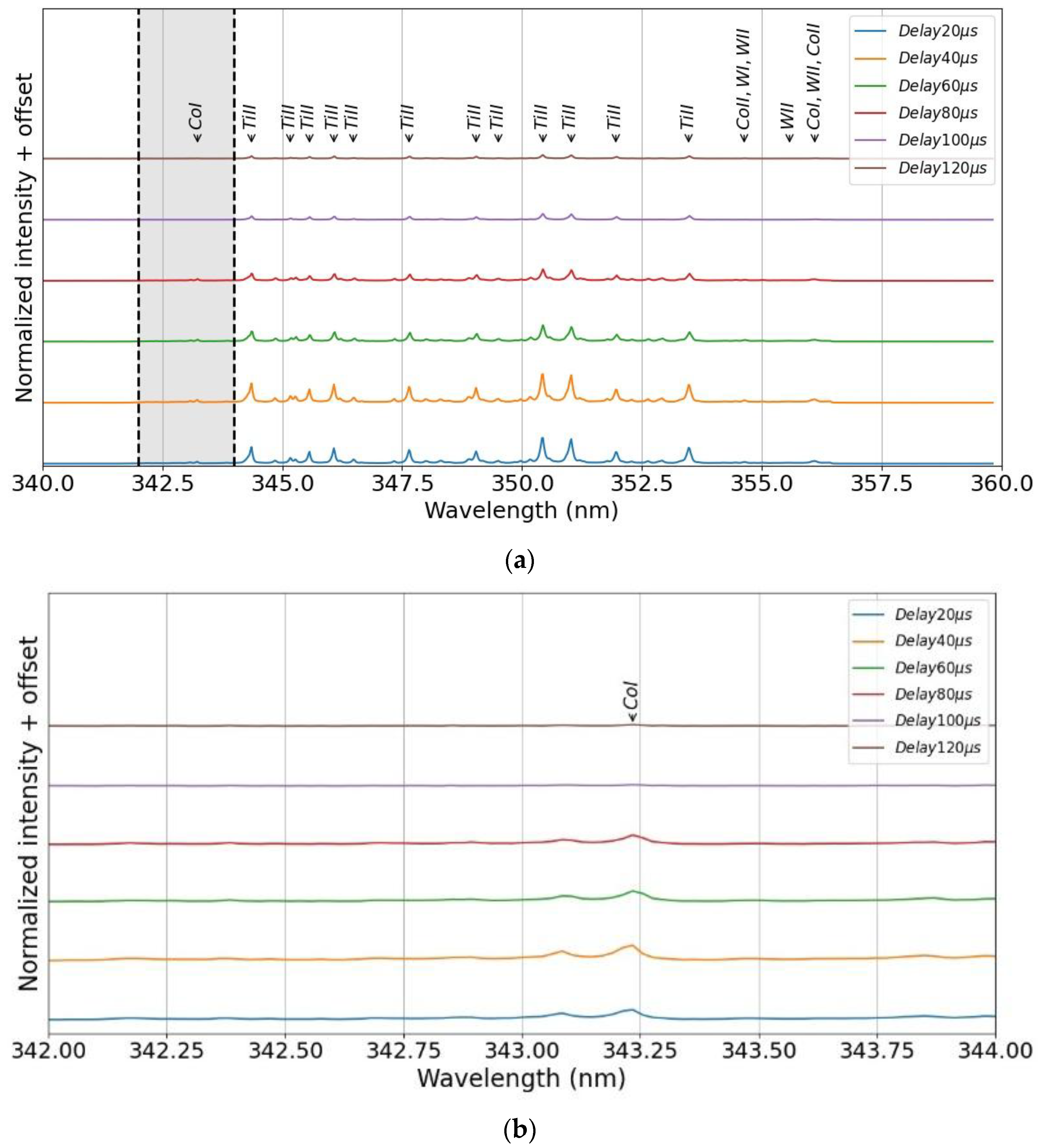

- Oxford Instruments Spectrometer Shamrock SR-500, Concord, MA, USA by Andor. Atomic spectrum varying energy and number of pulses with the following laser conditions: pulses 10-laser (variable energy) TD2-TI8, grid 2399l-nm, shutter 12 µm, ablations 10. Energy Signal 6 decreases to signal 1, from 120 to 20 delay.

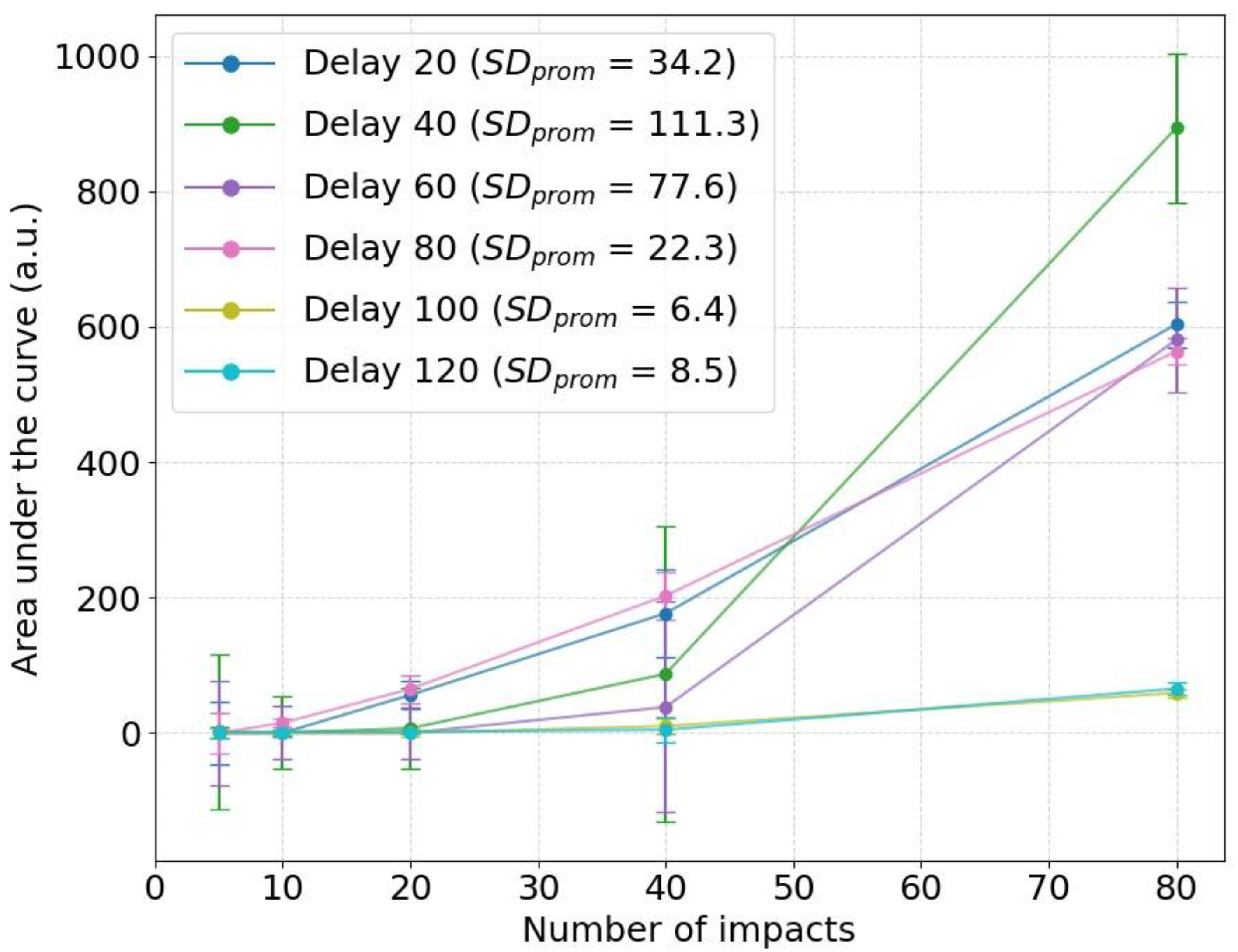

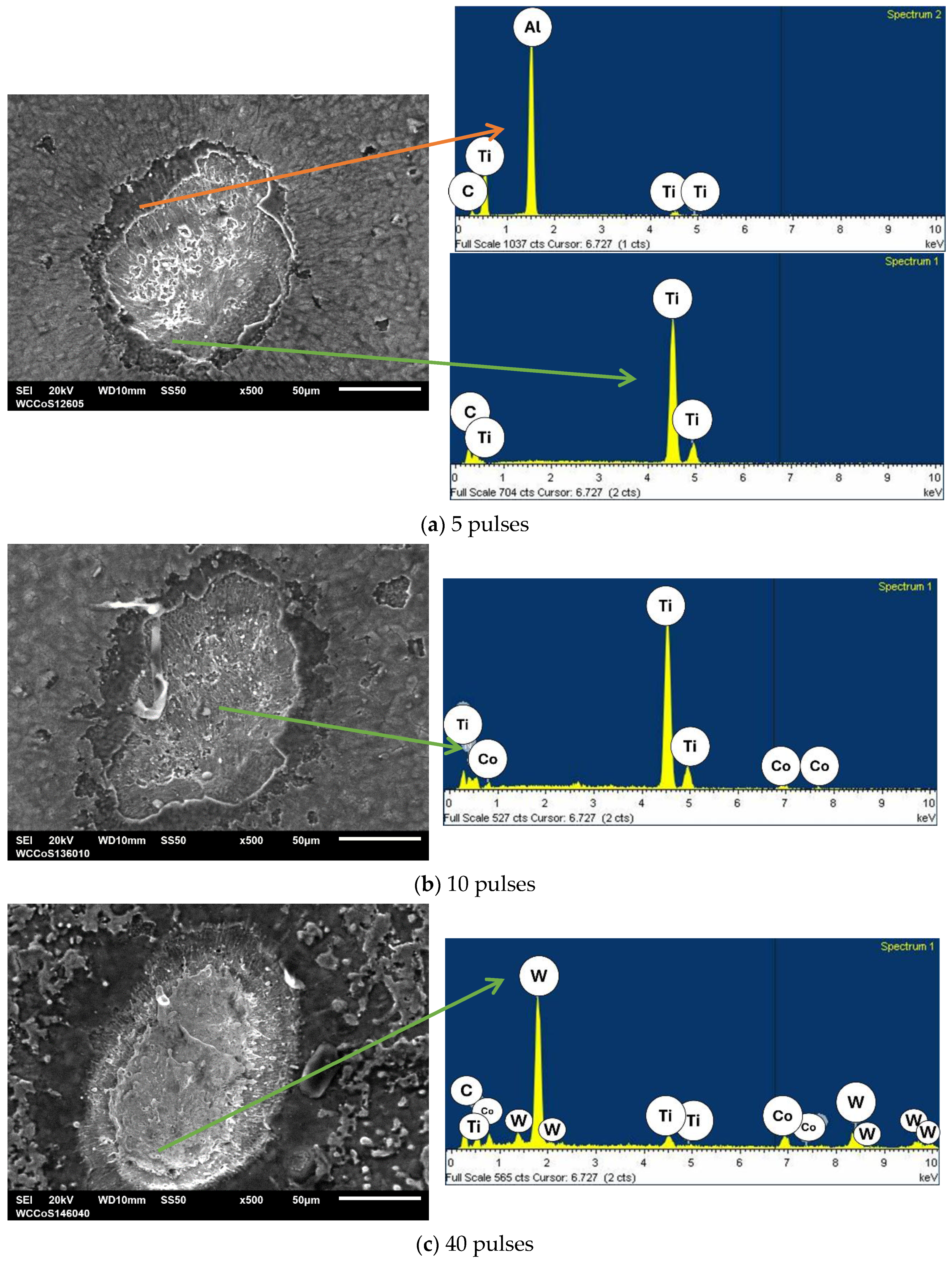

- Zeiss (Oberkochen, Germany) EVO MA 10 Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), equipped with EDS for surface and compositional analysis.

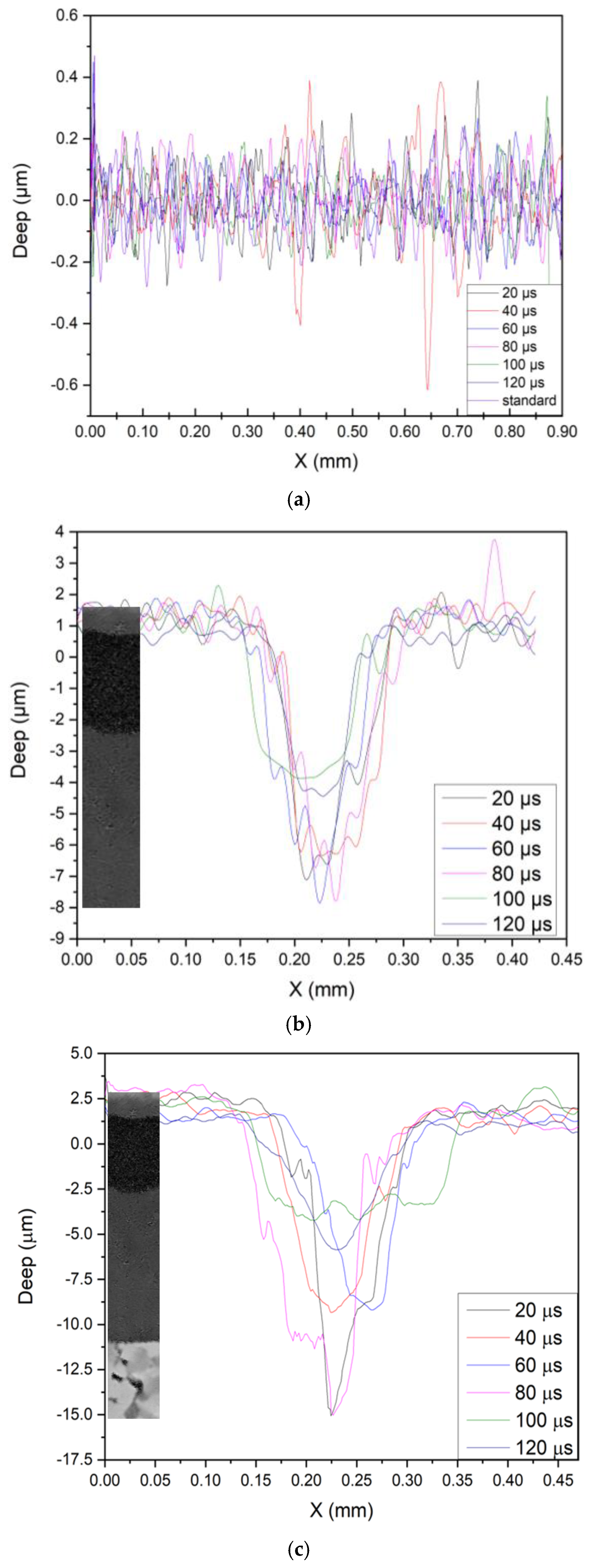

- Bruker (Billerica, MA, USA) 3D ContourX-100 Optical profilometry (Gwyddion software 2.37) to quantify ablation depth and surface roughness.

3. Results

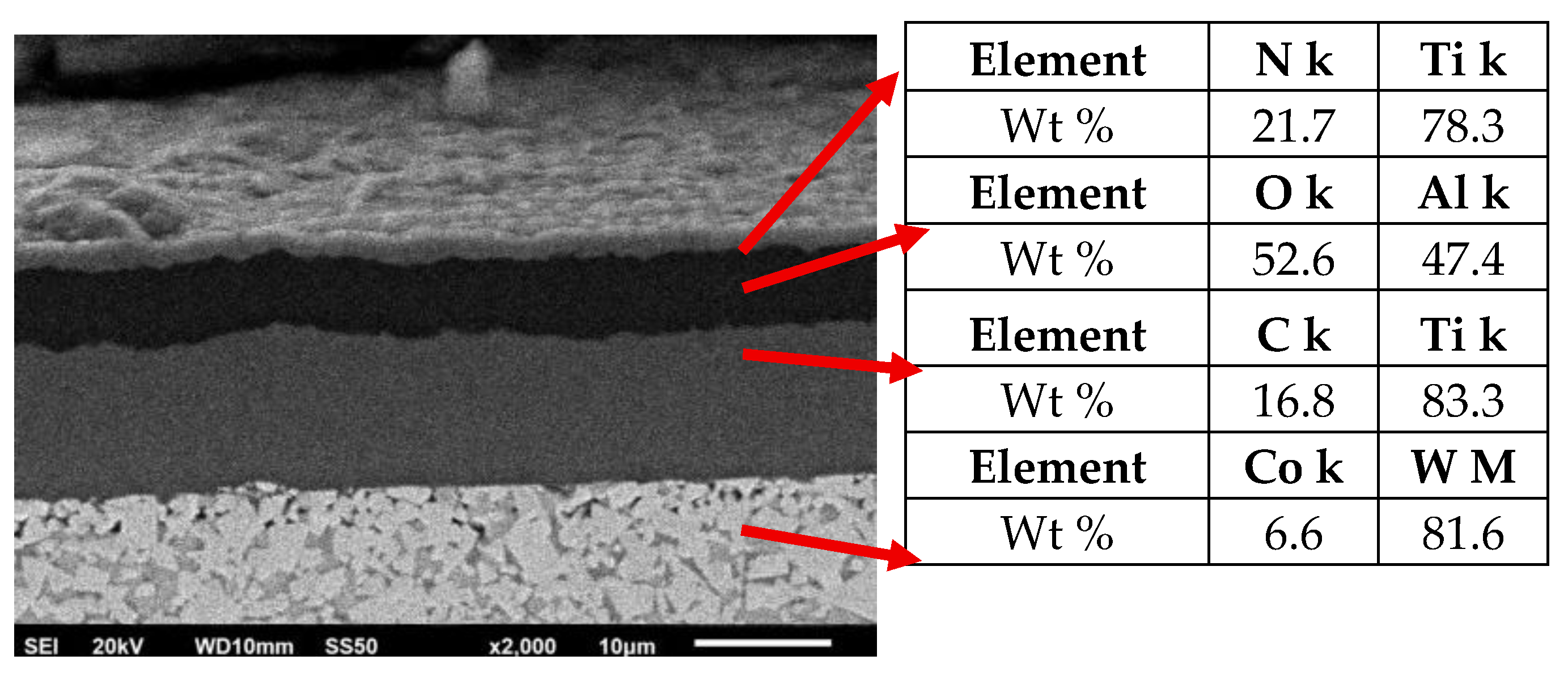

- Titanium and Nitrogen signals

- Aluminum and Oxygen

- Cobalt and Tungsten

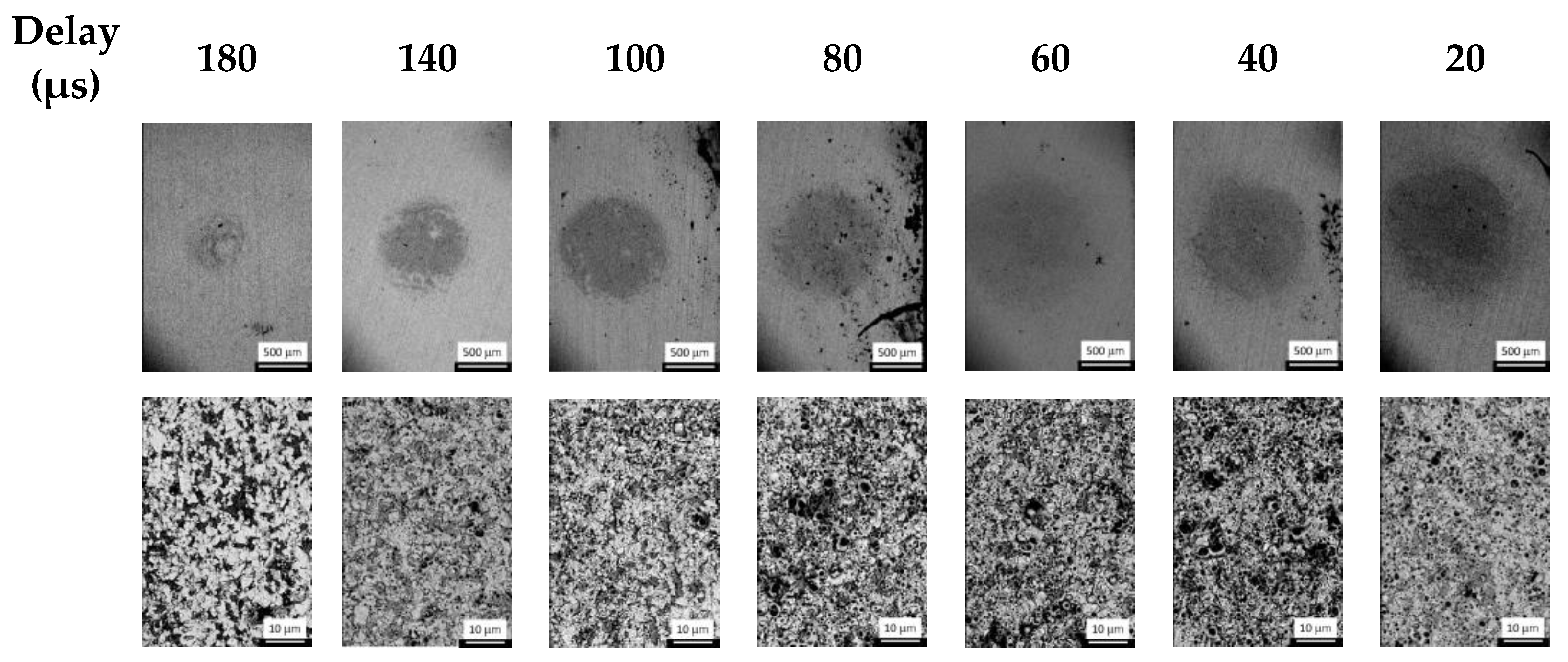

- Effect of Delay Time

Surface Morphology and Profilometry

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fudger, S.J.; Luckenbaugh, T.L.; Hornbuckle, B.C.; Darling, K.A. Mechanical Properties of Cemented Tungsten Carbide with Nanocrystalline FeNiZr Binder. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2024, 118, 106465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Membrado, L.; Liu, C.; Cabezas, L.; Lin, L.L.; Mahani, S.F.; Wang, M.S.; Jiménez-Piqué, E.; Llanes, L. Fracture Mechanics Analysis of Hardmetals by Using Artificial Small-Scale Flaws Machined at the Surface through Short-Pulse Laser Ablation. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2023, 111, 106084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarev, S.S.; Shatov, A.V.; Mikhailov, A.A.; Firstov, S.A. Carbon Distribution in WC Based Cemented Carbides. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2015, 49, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mégret, A.; Vitry, V.; Delaunois, F. Study of the Processing of a Recycled WC–Co Powder: Can It Compete with Conventional WC–Co Powders? J. Sustain. Met. 2021, 7, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini, A.; Lupi, F.; Rossi, A.; Seggiani, M.; Lanzetta, M. Direct Recycling of WC-Co Grinding Chip. Materials 2023, 16, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczyk, A.H.; Bartl, A.; Amato, A.; Lapkovskis, V.; Petranikova, M. Sustainability Evaluation of Essential Critical Raw Materials: Cobalt, Niobium, Tungsten and Rare Earth Elements. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2018, 51, 203001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, P.K.; Randhawa, N.S. A Comprehensive Review on Recycling Methods for Cemented Tungsten Carbide Scraps Highlighting the Electrochemical Techniques. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2020, 90, 105251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Kariminejad, A.; Antonov, M.; Goljandin, D.; Klimczyk, P.; Hussainova, I. Progress in Sustainable Recycling and Circular Economy of Tungsten Carbide Hard Metal Scraps for Industry 5.0 and Onwards. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Nam, H.K.; Watanabe, S.; Park, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, Y.-J.; Fushinobu, K.; Kim, S.-W. Selective Laser Ablation of Metal Thin Films Using Ultrashort Pulses. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.—Green Technol. 2021, 8, 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Na, S. Metal Thin Film Ablation with Femtosecond Pulsed Laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2007, 39, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostendorf, A.; Gurevich, E.L.; Shizhou, X. Selective Ablation of Thin Films by Pulsed Laser. In Fundamentals of Laser-Assisted Micro-and Nanotechnologies; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 201–219. [Google Scholar]

- Riu, G.; Monclús, M.A.; Slawik, S.; Cinca, N.; Tarrés, E.; Mücklich, F.; Llanes, L.; Molina-Aldareguia, J.M.; Guitar, M.A.; Roa, J.J. Microstructural and Mechanical Properties at the Submicrometric Length Scale under Service-like Working Conditions on Ground WC-Co Grades. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2023, 116, 106359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretschmer, A.; Jaszfi, V.; Dalbauer, V.; Schott, V.; Benedikt, S.; Eriksson, A.O.; Limbeck, A.; Mayrhofer, P.H. Designing Selective Stripping Processes for Al-Cr-N Hard Coatings on WC-Co Cemented Carbides. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 472, 129914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, A.A.; Turcu, R.N.; Pencea, I.; Herghelegiu, E.; Petrescu, M.I.; Niculescu, F. Comparative Characterization of the TiN and TiAlN Coatings Deposited on a New WC-Co Tool Using a CAE-PVD Technique. Crystals 2023, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila, L.C.; Moreno, C.M.; Sánchez, J.M. Electrolytic Removal of Chromium Rich PVD Coatings from Hardmetals Substrates. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2010, 28, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavola, F.; Gaudenzi, G.P.D.; Bidinotto, G.; Casamichiela, F.; Pola, A.; Tedeschi, S.; Bozzini, B. Efficient and Sustainable Electrochemical Demolition of Hard-Metal Scrap with Co-Rich Binder. ChemSusChem 2025, 18, e202402218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Lu, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y. Study of the Electrochemical Recovery of Cobalt from Spent Cemented Carbide. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 22036–22042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebolé, R.; Martínez, A.; Rodriguez, R.; Fuentes, G.G.; Spain, E.; Watson, N.; Avelar-Batista, J.C.; Housden, J.; Montalá, F.; Carreras, L.J.; et al. Microstructural and Tribological Investigations of CrN Coated, Wet-Stripped and Recoated Functional Substrates Used for Cutting and Forming Tools. Thin Solid Film. 2004, 469–470, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xi, X.; Zhang, L.; Feng, M.; Nie, Z.; Ma, L. The Electrochemical Dissolution Mechanism and Treatment Process in the Molten-Salt Electrolytic Recovery of WC-Co Two-Phase Scraps. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2021, 896, 115219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LI, N.; HAREFA, E.; ZHOU, W. Nanosecond Laser Preheating Effect on Ablation Morphology and Plasma Emission in Collinear Dual-Pulse Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2022, 24, 115507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirk, M.D.; Molian, P.A.; Malshe, A.P. Ultrashort Pulsed Laser Ablation of Diamond. J. Laser Appl. 1998, 10, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B, J.C.D.; Ivanov, D.; Bilmes, G.M. Laser Ablation Thresholds of Thin Aluminium Films. In Proceedings of the Ultrafast Optics 2023—UFOXIII, Bariloche, Argentina, 26–31 March 2023; Optica Publishing Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; p. P2.17. [Google Scholar]

- Zawadzka, A.; Plociennik, P.; Lukasiak, Z.; Bartkiewicz, K.; Korcala, A.; Ouazzani, H.E.; Sahraoui, B. Laser Ablation and Thin Film Deposition. In Proceedings of the 2011 13th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks, Stockholm, Sweden, 26–30 June 2011; IEEE: Ln Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Furberg, A.; Fransson, K.; Zackrisson, M.; Larsson, M.; Arvidsson, R. Environmental and Resource Aspects of Substituting Cemented Carbide with Polycrystalline Diamond: The Case of Machining Tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primus, T.; Hlavinka, J.; Zeman, P.; Brajer, J.; Šorm, M.; Čermák, A.; Kožmín, P.; Holešovský, F. Investigation of Multiparameter Laser Stripping of Altin and Dlc c Coatings. Materials 2021, 14, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzakis, K.D.; Michailidis, N.; Skordaris, G.; Bouzakis, E.; Biermann, D.; M’Saoubi, R. Cutting with Coated Tools: Coating Technologies, Characterization Methods and Performance Optimization. CIRP Ann.—Manuf. Technol. 2012, 61, 703–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marimuthu, S.; Kamara, A.M.; Whitehead, D.; Mativenga, P.; Li, L.; Yang, S.; Cooke, K. Laser Stripping of TiAlN Coating to Facilitate Reuse of Cutting Tools. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2011, 225, 1851–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, F.; Yi, J.; Eckert, J. Effect of Laser Power on Microstructure and Properties of WC-12Co Composite Coatings Deposited by Laser-Based Directed Energy Deposition. Materials 2024, 17, 4215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, M.; Whitehead, D.; Mativenga, P.T.; Li, L.; Cooke, K.E. Excimer Laser Decoating of Chromium Titanium Aluminium Nitride to Facilitate Re-Use of Cutting Tools. Opt. Laser Technol. 2009, 41, 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, A.; Fischer, C.; Watkins, K.G.; Glasmacher, M.; Kheyrandish, H.; Brown, A.; Steen, W.M.; Beahan, P. Laser Removal of Oxides from a Copper Substrate Using Q-Switched Nd:YAG Radiation at 1064 Nm, 532 Nm and 266 Nm. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1998, 127–129, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, J.E.; Canioni, L.; Bousquet, B. Good Practices in LIBS Analysis: Review and Advices. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2014, 101, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.F.; Pereira-Filho, E.R.; Amarasiriwardena, D. Current Trends in Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy: A Tutorial Review. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2021, 56, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Joshi, H.C. Review on Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy: Methodology and Technical Developments. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2024, 59, 124–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, B.; Han, J.; Huang, S.; Qian, J.; Vleugels, J.; Castagne, S. Femtosecond Laser Processing of Cemented Carbide for Selective Removal of Cobalt. Procedia CIRP 2022, 113, 576–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von der Heide, C.; Grein, M.; Bräuer, G.; Dietzel, A. Methodology of Selective Metallic Thin Film Ablation from Susceptible Polymer Substrate Using Pulsed Femtosecond Laser. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 33413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prochazka, D.; Pořízka, P.; Novotný, J.; Hrdlička, A.; Novotný, K.; Šperka, P.; Kaiser, J. Triple-Pulse LIBS: Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy Signal Enhancement by Combination of Pre-Ablation and Re-Heating Laser Pulses. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2020, 35, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Lou, Q.; Dong, J.; Wei, Y.; Liu, J. Selective Removal of Cobalt Binder in Surface Ablation of Tungsten Carbide Hardmetal with Pulsed UV Laser. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2001, 145, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Ou, T.; Wang, M.; Lin, Z.; Lv, C.; Qin, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, H.; Zhao, N.; Zhang, Q. A Brief Review of Calibration-Free Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. Front. Phys. 2022, 10, 887171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Asghar, H.; Shah, S.K.H.; Naeem, M.; Abbasi, S.A.; Ali, R. Elemental Analysis of Sage (Herb) Using Calibration-Free Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtonen, J.; Aaltonen, T. Using Generated LIBS Data as a Base for Neural Network Architecture Development. In Proceedings of the 2023 46th MIPRO ICT and Electronics Convention (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 22–26 May 2023; IEEE: Ln Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1125–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Vereschaka, A.; Grigoriev, S.; Sitnikov, N.; Oganyan, G.; Sotova, C. Influence of Thickness of Multilayer Composite Nano-Structured Coating Ti-TiN-(Ti,Al,Cr)N on Tool Life of Metal-Cutting Tool. Procedia CIRP 2018, 77, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaca, G.R.G.; Hurtado, L.S.; Reyes, C.S. Laser Ablation of Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) Coatings Applied on EN AW-5251 Substrates; Ablacion Laser de Recubrimientos de Politetrafluoretileno (PTFE) Aplicados Sobre Sustratos EN AW-5251. Rev. De Met. 2014, 50, e027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denkena, B.; Dittrich, M.A.; Liu, Y.; Theuer, M. Automatic Regeneration of Cemented Carbide Tools for a Resource Efficient Tool Production. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 21, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, K.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Cui, W.; Song, C.; Wang, C.; Jia, X.; et al. CW Laser Damage of Ceramics Induced by Air Filament. Opto-Electron. Adv. 2025, 8, 240296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahdy, A.; Kotadia, H.R.; Sharp, M.C.; Opoz, T.T.; Mullett, J.; Ahuir-Torres, J.I. Effect of Surface Roughness on the Surface Texturing of 316 l Stainless Steel by Nanosecond Pulsed Laser. Lasers Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 10, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebentrost, P.; Engel, A.; Metzner, D.; Lampke, T.; Weißmantel, S. Case Study for the Formation of a Surface Alloy on Cemented Tungsten Carbide Using Ultrashort MHz to GHz Burst-Pulses. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 641, 158418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, D.A.; Chinni, R.C. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy—Capabilities and Limitations. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2009, 44, 457–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musazzi, S.; Perini, U. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy. In Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy: Theory and Applications.’ Springer Series in Optical Sciences; Agenzia Regionale Per La Protezione Dell’ambiente Della: Reggio Calabria, Italy, 2014; Volume 182, pp. E1–E2. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Li, N.; Tian, Y.; Guo, J.; Zheng, R. Study of Interpulse Delay Effects on Orthogonal Dual-Pulse Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy in Bulk Seawater. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2020, 35, 2351–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, L.; Detalle, V.; Sabsabi, M. Enhanced Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy Using the Combination of Fourth-Harmonic and Fundamental Nd: YAG Laser Pulses. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2002, 57, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radziemski, L.J. From LASER to LIBS, the Path of Technology Development. Spectrochim. Acta Part B At. Spectrosc. 2002, 57, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Delay−Pulse (μs) | Measured Energy (mJ) | Transmitted Energy (mJ) | Fluence (J/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 41.0 | 367.3 | 11.7 |

| 40 | 35.7 | 294.5 | 9.4 |

| 60 | 27.2 | 221.7 | 7.1 |

| 80 | 18.6 | 150.4 | 4.8 |

| 100 | 11.6 | 85.3 | 2.7 |

| 120 | 7.3 | 56.8 | 1.8 |

| 140 | N.D | 37.7 | 1.2 |

| 160 | N.D | 6.4 | 0.2 |

| 180 | N.D | 3.1 | 0.1 |

| Delay (µs) | Roughness (Ra) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Impact | 5 Impacts | 10 Impacts | 40 Impacts | |

| 20 | 0.27 | 1.10 | 2.27 | 8.12 |

| 40 | 0.31 | 1.32 | 2.05 | 4.44 |

| 60 | 0.28 | 1.76 | 2,40 | 6.65 |

| 80 | 0.32 | 1.70 | 3.44 | 9.13 |

| 100 | 0.33 | 1.41 | 1.32 | 4.44 |

| 120 | 0.37 | 1.04 | 2.15 | 3.51 |

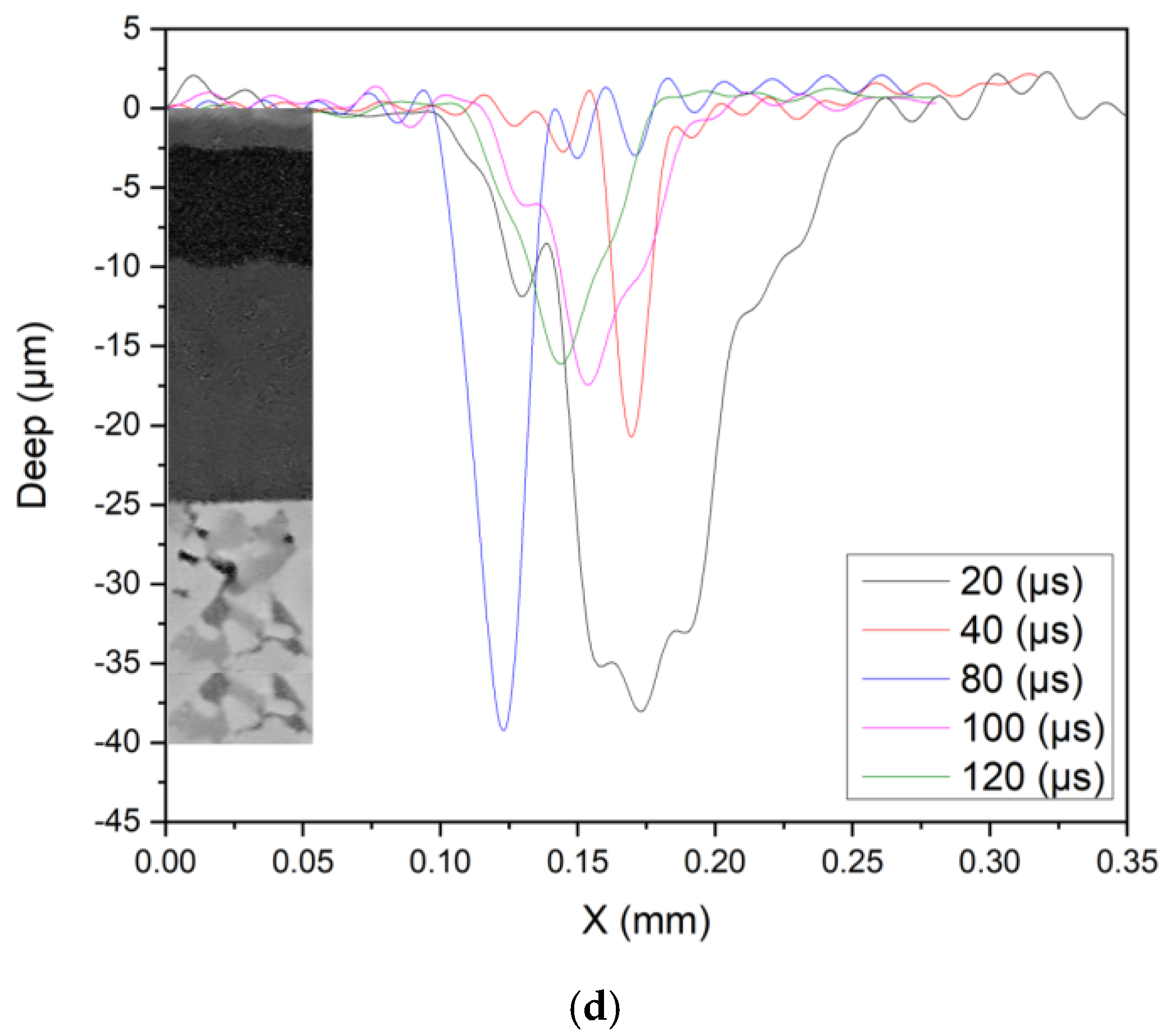

| Delay (µs) | Slope (m) | Std. Dev. Residuals (σr) | R2 | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 8.21 | 51.48 | 0.96 | y = 8.21x − 87.41 |

| 40 | 11.95 | 162.75 | 0.87 | y = 11.95x − 172.41 |

| 60 | 7.74 | 114.30 | 0.85 | y = 7.74x − 116.11 |

| 80 | 7.64 | 31.48 | 0.98 | y = 7.64x − 67.68 |

| 100 | 0.80 | 8.91 | 0.91 | y = 0.80x − 11.05 |

| 120 | 0.85 | 12.77 | 0.85 | y = 0.86x − 11.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Leal, G.A.; Moreno, C.M.; Hernández, R.C.; Mejía-Ospino, E.; Ardila, L.C. Effect of Nd:YAG Nanosecond Laser Ablation on the Microstructure and Surface Properties of Coated Hardmetals. Coatings 2025, 15, 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121413

Leal GA, Moreno CM, Hernández RC, Mejía-Ospino E, Ardila LC. Effect of Nd:YAG Nanosecond Laser Ablation on the Microstructure and Surface Properties of Coated Hardmetals. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121413

Chicago/Turabian StyleLeal, G. A., C. M. Moreno, R. C. Hernández, E. Mejía-Ospino, and L. C. Ardila. 2025. "Effect of Nd:YAG Nanosecond Laser Ablation on the Microstructure and Surface Properties of Coated Hardmetals" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121413

APA StyleLeal, G. A., Moreno, C. M., Hernández, R. C., Mejía-Ospino, E., & Ardila, L. C. (2025). Effect of Nd:YAG Nanosecond Laser Ablation on the Microstructure and Surface Properties of Coated Hardmetals. Coatings, 15(12), 1413. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121413