3.2.1. Consider the Velocity Erosion Analysis of the Stokes Number

Onshore wind turbines generate electricity at wind speeds ranging from approximately 3–4 m/s to 20–25 m/s. The maximum power output range starts at a rated wind speed of approximately 12–15 m/s and ends at a cut-out wind speed of approximately 20–25 m/s [

47]. Therefore, the speed settings in subsequent simulations will basically follow the actual conditions in industry.

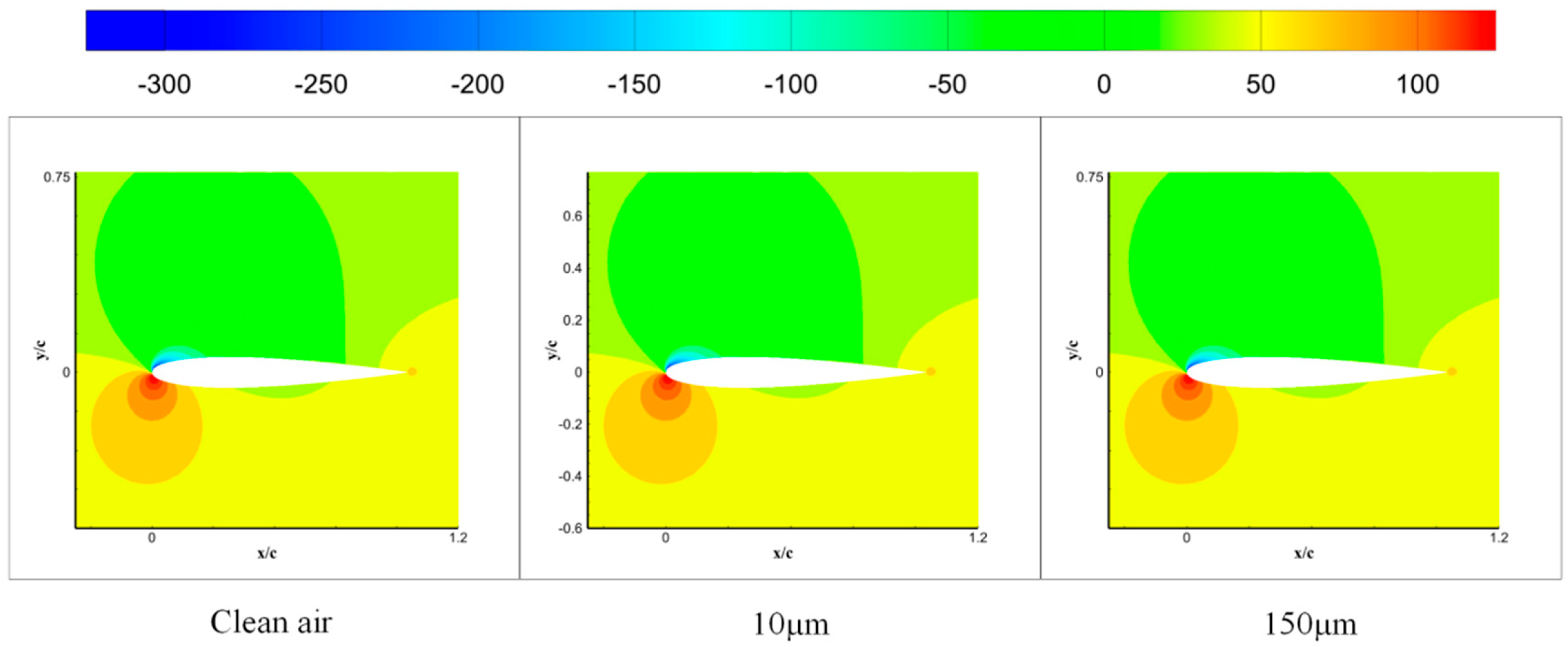

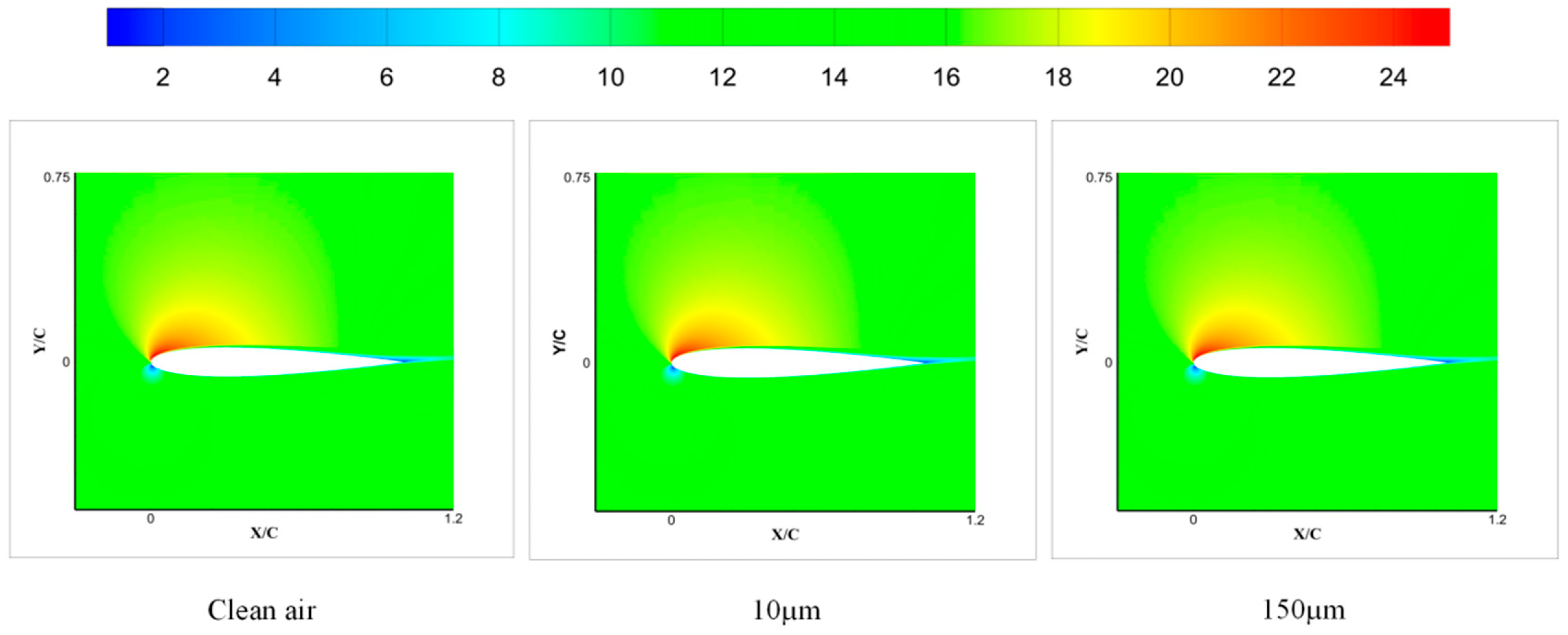

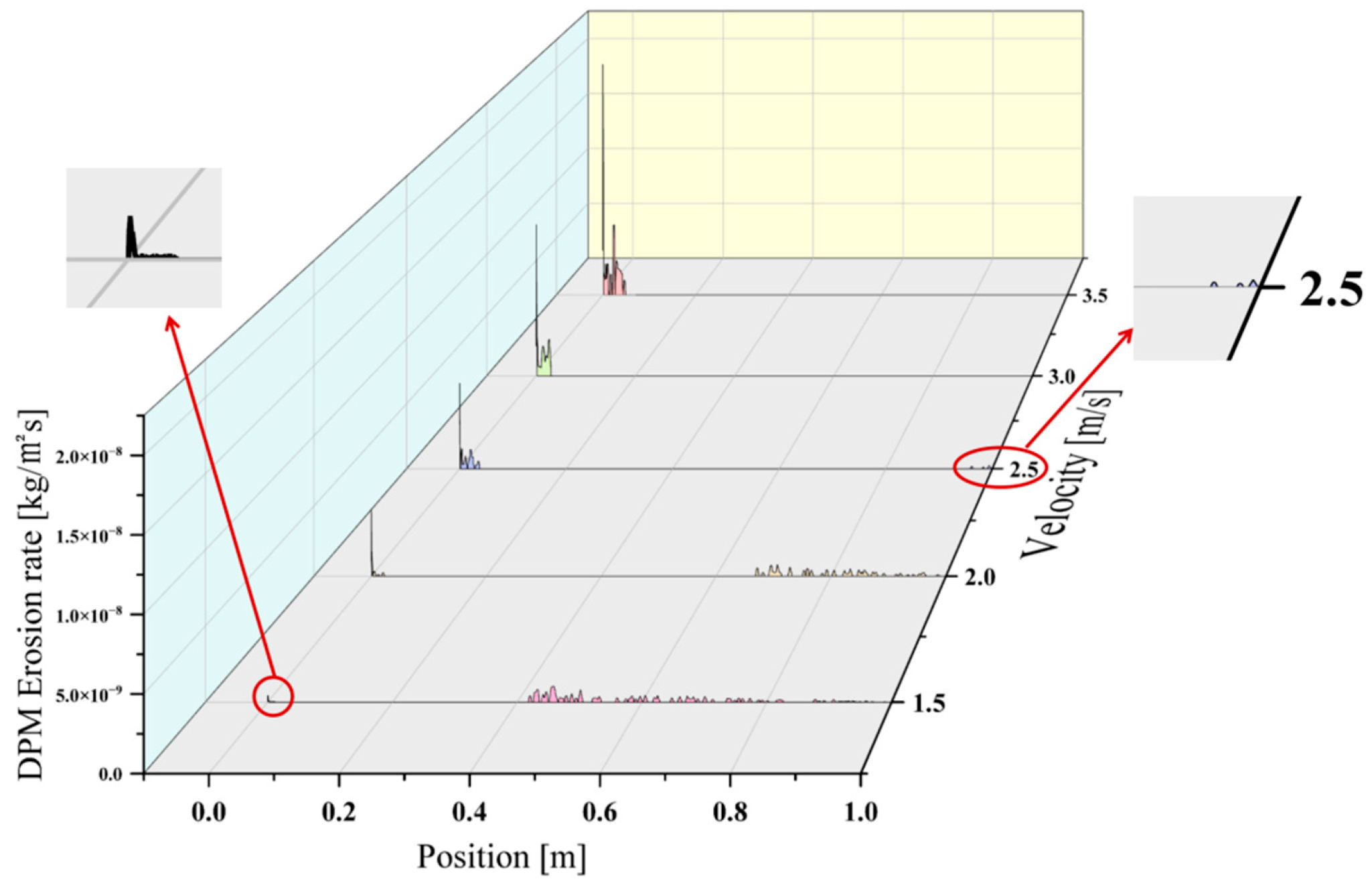

Figure 9 shows the erosion rate distribution of particles with a density of 2800 kg/m

3 and a diameter of 50 μm under conditions of 1.5 m/s, 2 m/s, 2.5 m/s, 3 m/s, and 3.5 m/s, respectively, under the condition of

Stk << 1. As shown in the figure, at a speed of 1.5 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.03 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.45 m from the leading edge. The average erosion rate across the wing is 2.43 × 10

−10 kg/m

2s. As the speed increases, when the speed reaches 2 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 4.81 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0001 m from the leading edge. The average erosion rate across the wing is 4.32 × 10

−10 kg/m

2s. When the speed increases to 2.5 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 6.59 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 1.03 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0001 m from the leading edge. When the speed increases to 3 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.25 × 10

−8 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0005 m from the leading edge. The average erosion rate across the wing is 2.74 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. When the speed was increased to 3.5 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.04 × 10

−8 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0005 m from the leading edge. The average erosion rate across the wing surface is 3.98 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s.

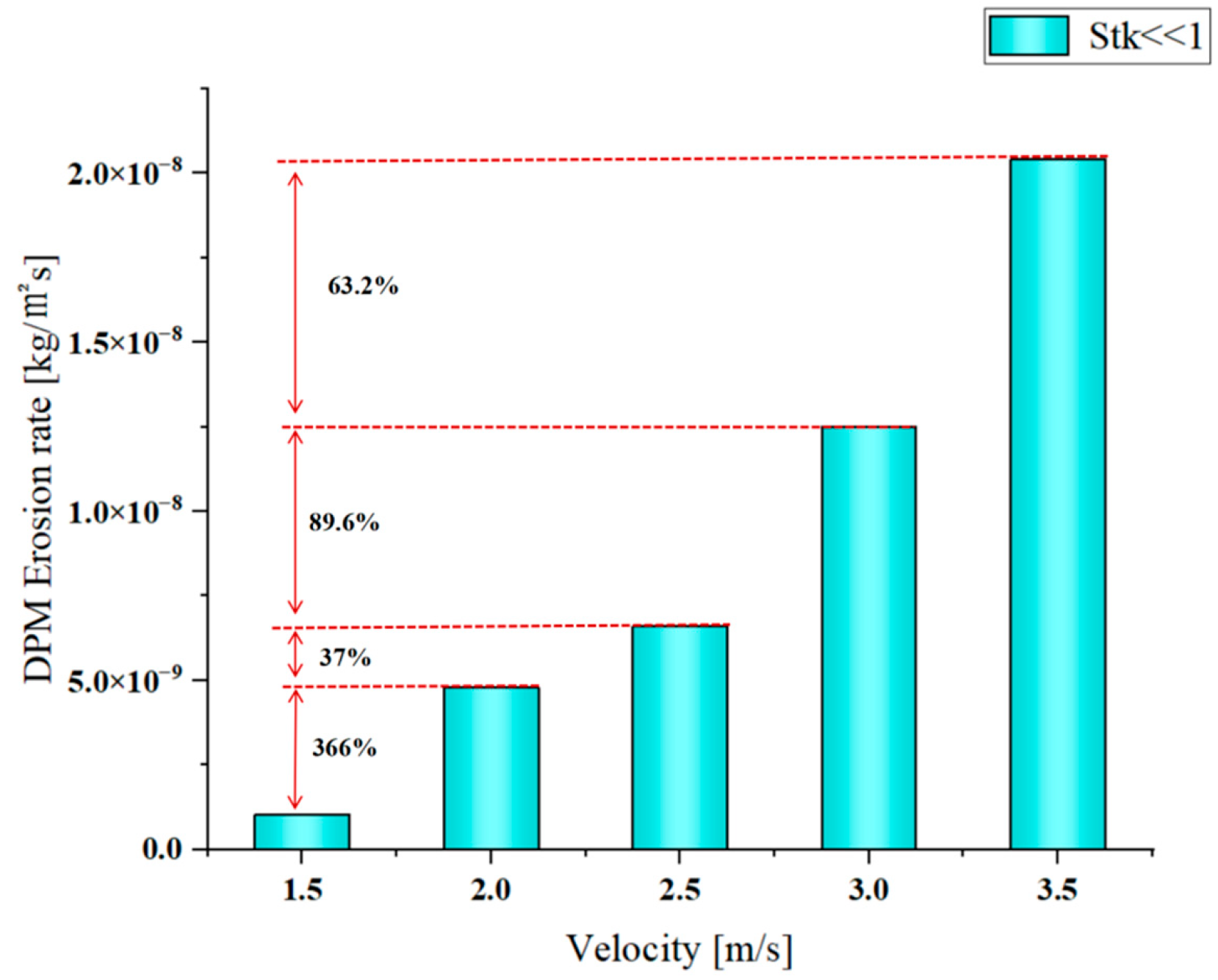

As shown in

Figure 10, when

Stk << 1, both the maximum erosion rate of the airfoil and the average erosion rate of the airfoil as a whole show a trend of increasing erosion rate with increasing speed. Therefore, the highest erosion rate occurs at a speed of 3.5 m/s. Taking a speed of 1.5 m/s as the baseline, when the speed is increased to 3.5 m/s, the maximum erosion rate increases to 19.4 times the baseline, and the average erosion rate on the wing surface increases to 15.4 times the baseline. The main reason for this situation is the combined effect of the Stokes number, Reynolds number, and particle kinetic energy. Particles can move well along streamlines at low

Stk, but

Stk increases with increasing velocity, indicating that the inertial effect of particles gradually increases, and more particles may collide with the wing surface. At a speed of 1.5 m/s, the boundary layer is relatively thick at approximately 3.12 mm, and the flow tends to be laminar. Particles can penetrate the boundary layer, but their inertia is low, so most particles follow the streamlines around the airfoil, resulting in a low collision rate. As the speed increases, the flow enters the transition zone, where laminar separation bubbles or partial turbulence occur. The boundary layer thins to approximately 2.4 mm, increasing particle inertia and causing more particles to collide with the surface, thereby increasing the erosion rate. As the speed continues to increase, turbulence effects intensify, and turbulent separation occurs at the trailing edge of the upper surface of the airfoil. The separation zone causes a reduction in local flow velocity and a shallower impact angle, thereby reducing the probability of particles colliding with the trailing edge of the airfoil.

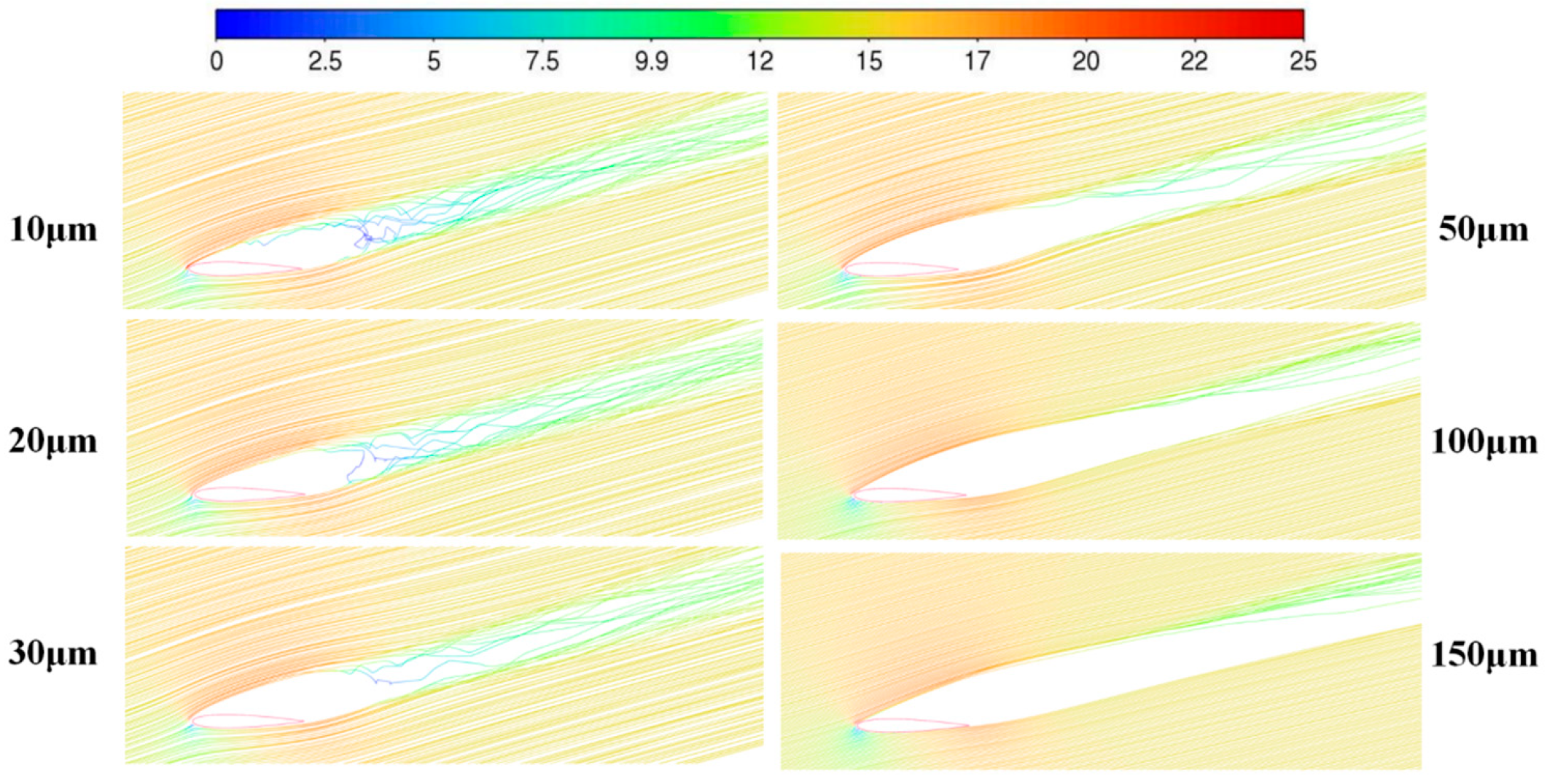

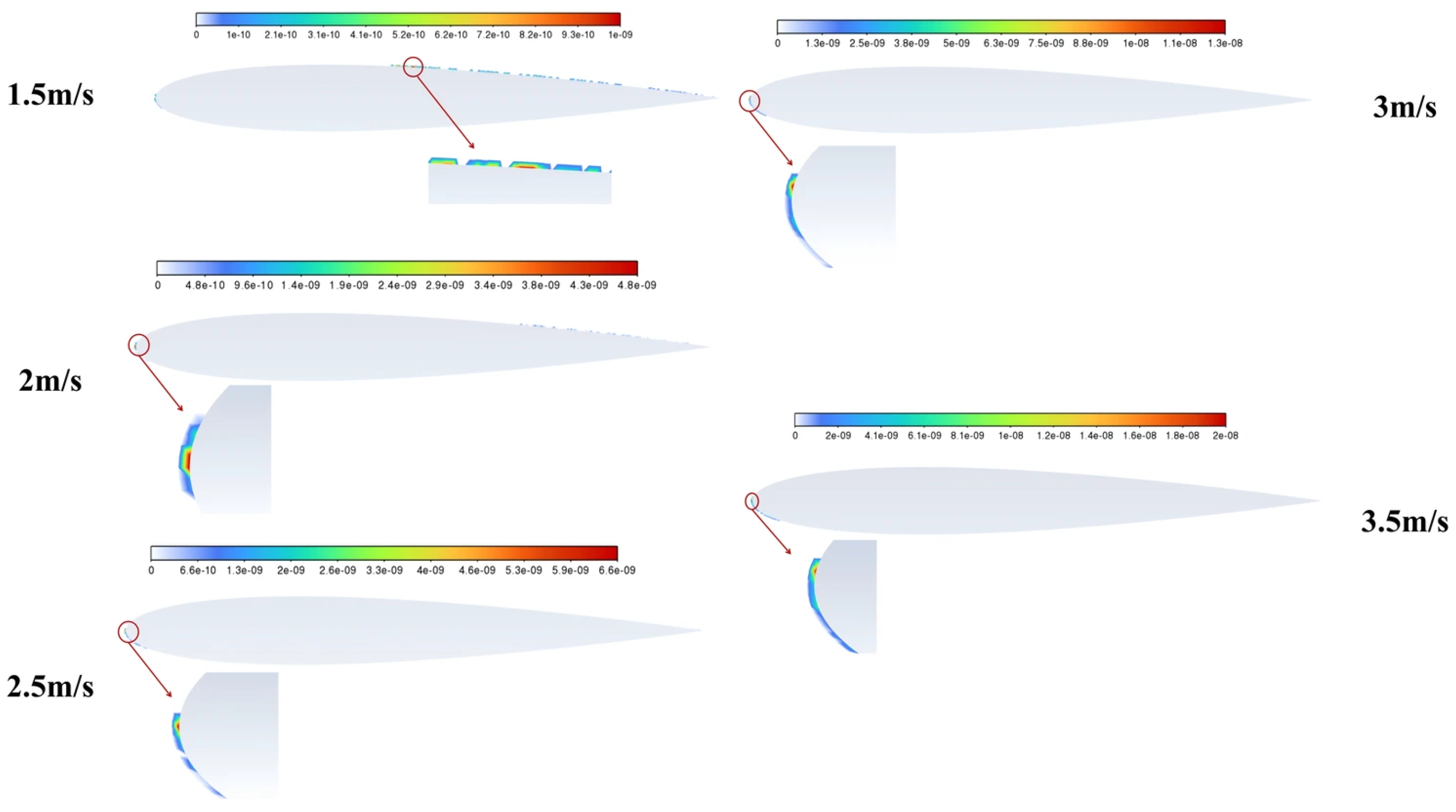

As shown in

Figure 11, as the speed increases from 1.5 m/s, the location of erosion also changes significantly. When the speed is 1.5 m/s, erosion mainly occurs in the rear part of the airfoil, at approximately 45% to 100% of the chord length. As speed increases, the area of erosion in the middle of the wing profile gradually decreases. When the speed increases to 2.5 m/s, erosion mainly occurs at the 5% chord length position before the leading edge of the airfoil and the 90% chord length position after the trailing edge. As the speed continues to increase, the collision between the rear edge particles and the airfoil gradually disappears, and erosion no longer occurs at the rear edge of the airfoil. Only erosion occurs at the leading edge. The reason for this phenomenon is that when the speed is 1.5 m/s, the flow field is in the laminar flow dominant zone, and NACA 0012 undergoes long laminar separation bubbles at an angle of attack of 6°. While particles in this regime closely follow the mean streamlines, they can still exhibit weak preferential accumulation in the high-strain-rate region near the flow reattachment point. The point of separation occurs roughly between 5% and 10% from the leading edge, while the reattachment location is situated approximately between 40% and 60% of the chord length from the leading edge. The flow velocity in the reattachment zone increases dramatically, accelerating particles and causing them to collide with the surface. The low-speed flow in the separation zone at the trailing edge causes the particles to settle, greatly increasing the probability of collision between the particles and the airfoil. This localized concentration enhancement, combined with particle acceleration upon reattachment, gives rise to the distinct erosion band observed at 45%–100% chord length.

When the speed reaches 2.5 m/s, the flow field enters the critical transition zone, with the separation point moving forward to 2%–5% of the chord length at the leading edge, and the reattachment point moving forward to 20%–30% of the chord length, while the separation bubble shortens. The shortening of the separation bubble causes an increase in the curvature of the leading edge streamline, while the increase in Stk causes the particles to collide with the leading edge due to inertia, resulting in erosion of the leading edge. Due to the forward shift in the reattachment point, the central particles flow close to the surface without any violent acceleration or diffusion collision phenomena occurring. The trailing edge is located in the turbulent separation zone, causing particles to be sucked in and collide with the wing surface, resulting in erosion. Concurrently, the effective Stk of the particles increases. For particles with Stk on the order of 0.1–1, the mechanism of clustering becomes most effective in the high-strain regions generated by the strong curvature of the flow around the leading edge. Consequently, the particle impacts become concentrated in the stagnation region and immediately downstream on the upper and lower surfaces, causing the erosion hotspot to shift decisively to the leading edge. When the speed increases to 3.5 m/s, the flow field becomes turbulent, the separation point moves forward significantly, and the separation bubble disappears. The streamlines bend sharply at the leading edge, and as Stk continues to increase, the particles cannot follow the streamlines and collide with the leading edge. The separation resistance of the rear edge turbulent boundary layer is enhanced, and the separation point disappears. As particles move along the surface to the trailing edge, their velocity decreases, and there is no separation zone to capture the particles, thus preventing erosion from occurring.

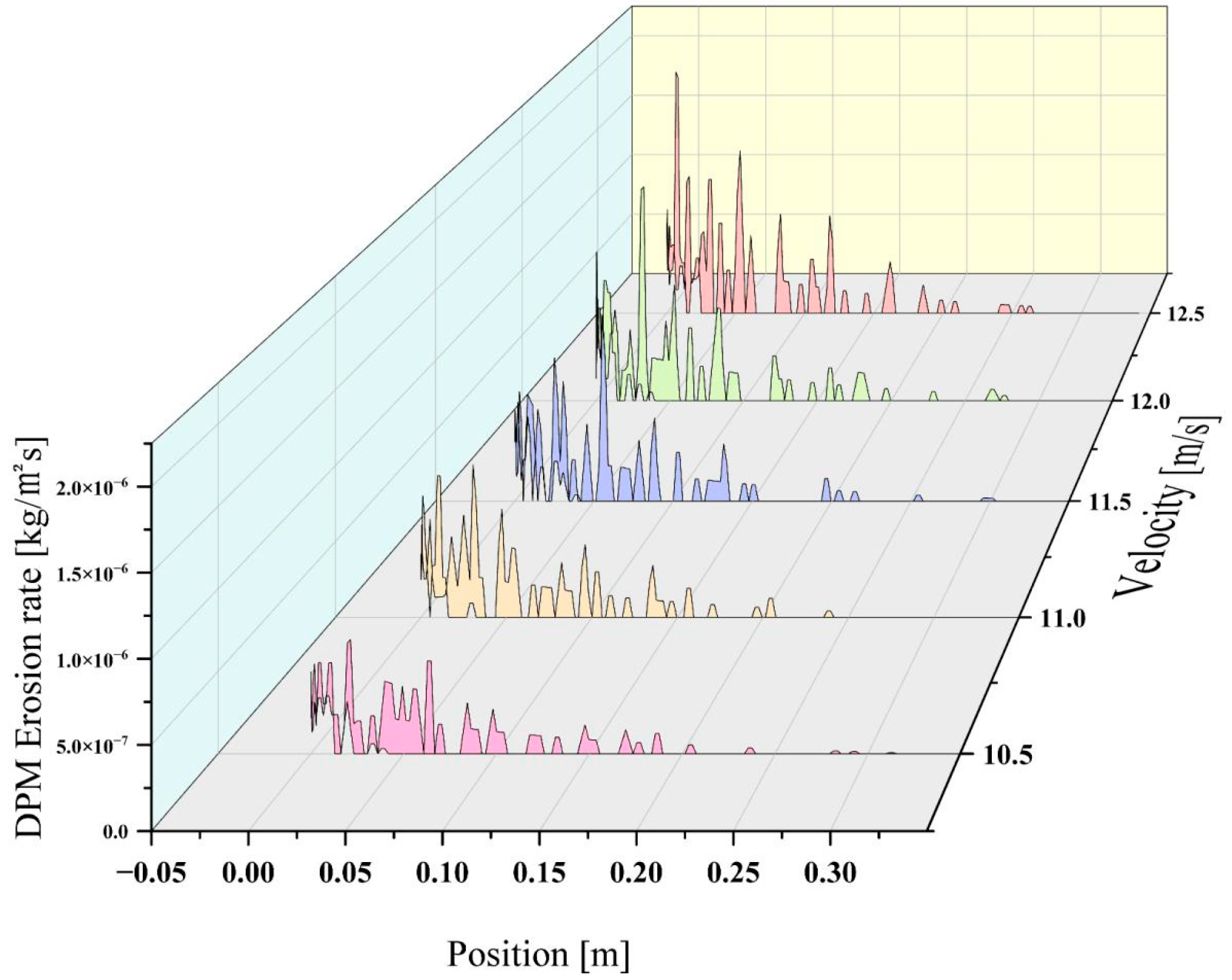

Figure 12 shows the erosion rate distribution of particles with a density of 2800 kg/m

3 and a diameter of 100 μm under conditions of 10.5 m/s, 11 m/s, 11.5 m/s, 12 m/s, and 12.5 m/s, respectively, under

Stk ≈ 1 conditions. At this point, the

Stk ranges from 0.91 to 1.09. At a speed of 10.5 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 6.93 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s, and the average erosion rate across the wing is 2.19 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.021 m from the leading edge. At a speed of 11 m/s, erosion occurs 0.03 m from the leading edge. The peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.01 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 2.98 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. When the speed reaches 11.5 m/s, the highest erosion point occurs at a distance of 0.05 m from the leading edge, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.28 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 3.27 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. When the speed reaches a maximum of 12.5 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.97 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing surface is 4.33 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.006 m from the leading edge.

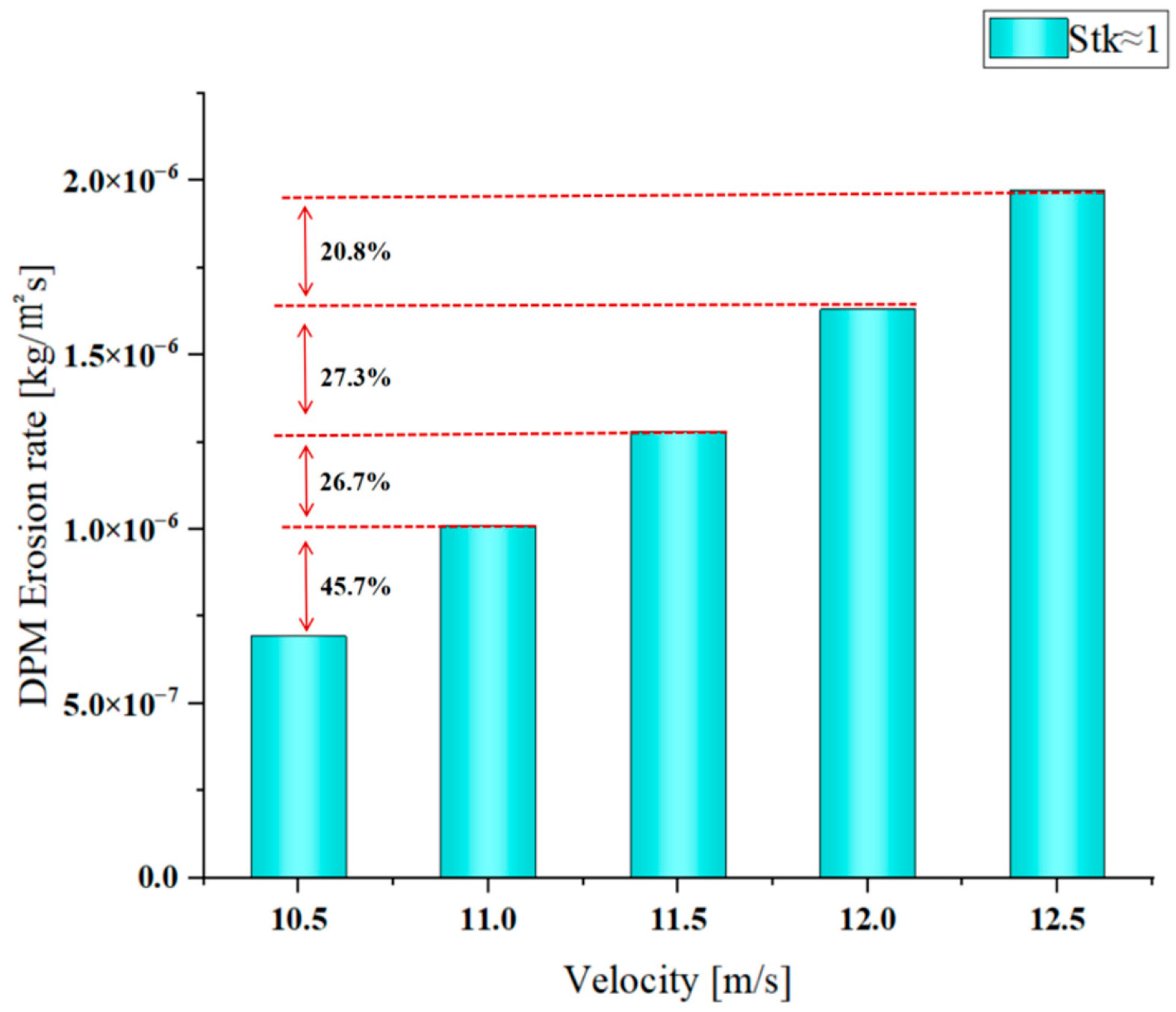

As shown in

Figure 13, with the speed gradually increasing from 10.5 m/s, the maximum erosion rate and the erosion rate of the airfoil surface show a clear trend of increasing with speed. When the speed increased from 10.5 m/s to 12.5 m/s, the maximum erosion rate increased by 180% and the average erosion rate increased by 97%. The reasons for this phenomenon are as follows: From the perspective of particle characteristics,

Stk ≈ 1 indicates that the particles partially follow the fluid, but compared to

Stk << 1, the inertial effect is significant, causing the particles to collide with the surface at a higher energy. As speed increases, particle inertia increases, increasing the frequency and kinetic energy of collisions, thereby increasing the erosion rate. Under a small attack angle, the particles collide in a “sliding” manner, increasing the cutting effect. As the velocity increases, the ability of particles to penetrate the surface boundary layer is enhanced, resulting in more particles effectively impacting the surface and increasing the overall erosion rate.

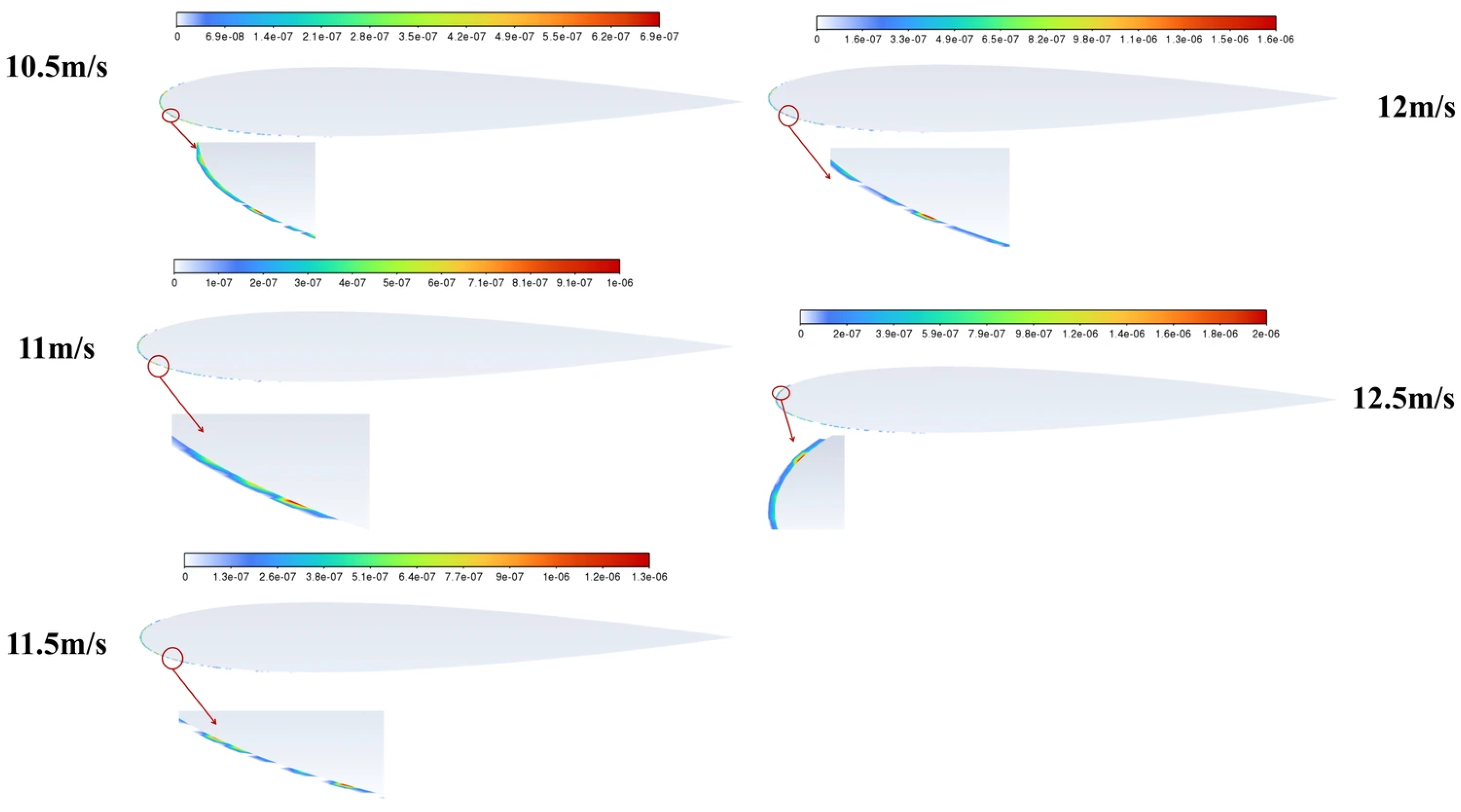

As shown in

Figure 12 and

Figure 14, erosion occurs at the leading edge of the airfoil under all speed conditions. However, as speed increases, there is a tendency for erosion to gradually concentrate toward the leading edge. This situation occurs because particles are more likely to follow curved streamlines at a speed of 10.5 m/s. Some particles bypass the leading edge, resulting in fewer impacts in the stagnation zone and relatively divergent erosion locations. As particle velocity increases, the Stokes number gradually increases, and the particle inertia becomes greater, making it difficult to deflect along the streamline. This situation leads to more particles colliding with the surface, with impacts concentrated in the landing zone and higher energy, while the area of the high-damage core zone shrinks slightly. The “impact width” near the stagnation point increases, and erosion extends to both sides of the leading edge and part of the downstream area. At the leading edge of the wing profile, the streamline curvature is most pronounced. As speed increases, fluid acceleration increases and streamline curvature increases. The erosion cloud map shows that the location of the highest erosion rate has changed from the leading edge of the lower surface to the leading edge of the upper surface. The reason for this phenomenon is that as speed increases, the inertial separation of the high curvature area on the upper surface becomes more intense, and the impact on the upper surface becomes more concentrated, resulting in an increase in the erosion rate at a single location on the leading edge of the upper surface. The flat streamlined lower surface allows particles to slide easily and disperse energy, while the erosion rate at a single position at the leading edge of the lower surface decreases. Under these conditions, collision position transition occurs.

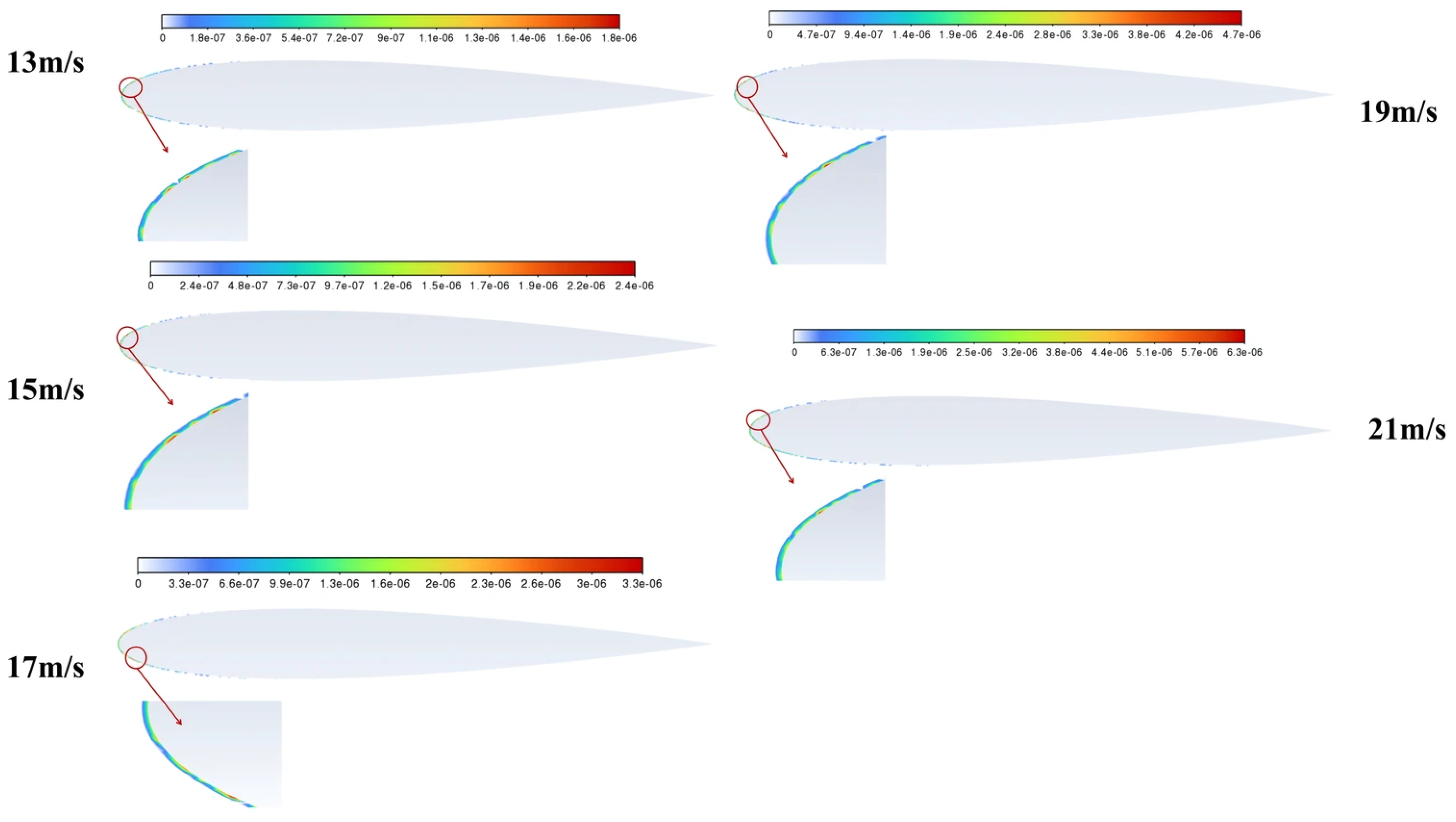

Figure 15 shows the erosion rate distribution of particles with a density of 2800 kg/m

3 and a diameter of 300 μm under conditions of 13 m/s, 15 m/s, 17 m/s, 19 m/s, and 21 m/s, respectively, under conditions of

Stk >> 1. As shown in the figure, at a velocity of 13 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.79 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 5.17 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.016 m from the leading edge. As the velocity rises to 15 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.42 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 7.86 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.02 m from the leading edge. As the velocity rises to 17 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 3.29 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 1.08 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.025 m from the leading edge. As the velocity rises to 19 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 4.7 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 1.32 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0016 m from the leading edge. When the speed was increased to 21 m/s, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 6.31 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 1.74 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0012 m from the leading edge.

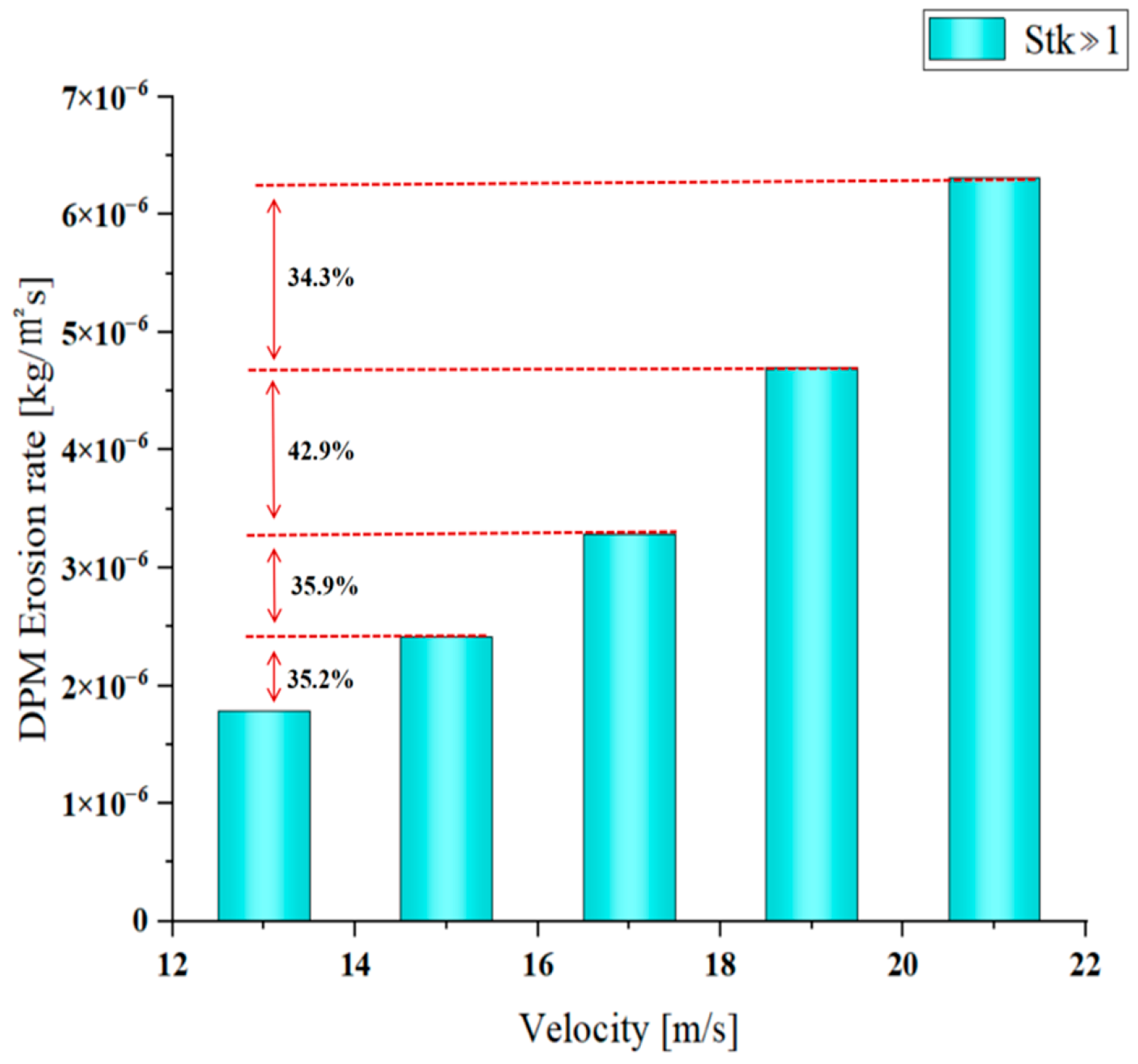

As shown in

Figure 16, when

Stk >> 1, both the maximum erosion rate of the airfoil and the average erosion rate of the airfoil as a whole show a trend of increasing erosion rate with increasing speed. Therefore, the highest erosion rate occurs at a speed of 21 m/s. Based on a speed of 13 m/s, when the speed is increased to 21 m/s, the maximum erosion rate increases by 252%, and the average erosion rate of the airfoil surface increases by 234%. From the perspective of particle characteristics, when

Stk >> 1, it indicates that the particles cannot completely follow the airflow streamlines but tend to collide with the wing surface. Especially at an angle of attack of 6 degrees, the leading edge and upper surface are susceptible to impact. As the speed increases, the

Stk increases accordingly, improving collision efficiency and intensifying erosion. At small attack angles, shallow-angle impacts tend to produce micro-cutting effects, which can easily cause noticeable collision effects. At the same time, an increase in the tangential momentum of the particles amplifies this cutting effect, resulting in a higher erosion rate. Given that air serves as a fluid medium, when exposed to high-inertia particles such as gravel, the fluid’s drag force acting on these particles is relatively weak, causing their motion to be predominantly governed by inertia. Therefore, when the speed increases, the change in particle kinetic energy is more directly converted into impact energy rather than being dissipated by the fluid. Three factors combined to cause an increase in erosion rates.

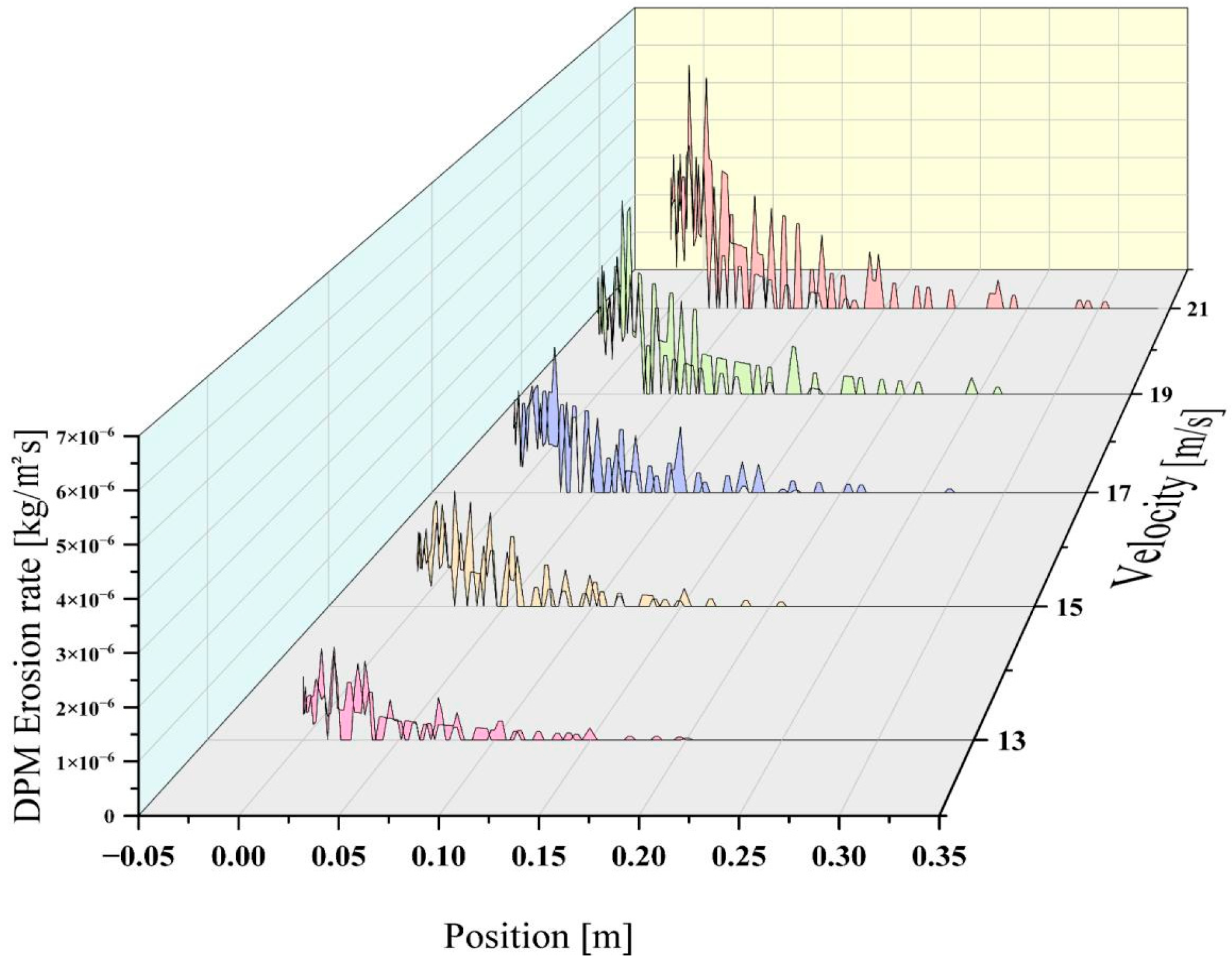

As can be seen from

Figure 15 and

Figure 17, with the increase in speed, the erosion area on the fan blade surface expands progressively. Combining the erosion cloud diagrams at different speeds in

Figure 17, it becomes evident that erosion spread across the wing surface is predominantly concentrated on the wing’s lower side, while the erosion area on the upper surface remains basically unchanged. When

Stk >> 1, particle inertia dominates, and particles cannot completely follow the airflow streamlines. As speed increases,

Stk increases, particle inertia becomes stronger, and particles are more likely to deviate from the streamlines and collide with surfaces. At an angle of attack of 6°, for a symmetrical airfoil such as NACA0012, the airflow on the upper surface accelerates, and the streamline curvature is small, especially in the middle of the chord length to the trailing edge. Particles tend to maintain linear motion under the influence of inertia, but due to the straight streamlines, the impact location is concentrated near the leading edge. In the middle and rear sections, the streamlines are straight, and the particles are easily carried away by the airflow, with no significant change in the impact range. The airflow slows down on the lower surface, and the streamlines have a large curvature, making it difficult for particles to follow the curved airflow due to inertia. Some small inertial particles can follow the airflow around the surface. As the speed increases, it becomes more difficult for the particles to follow the airflow, and they are more likely to collide, causing the erosion area to expand toward the middle and rear edges.

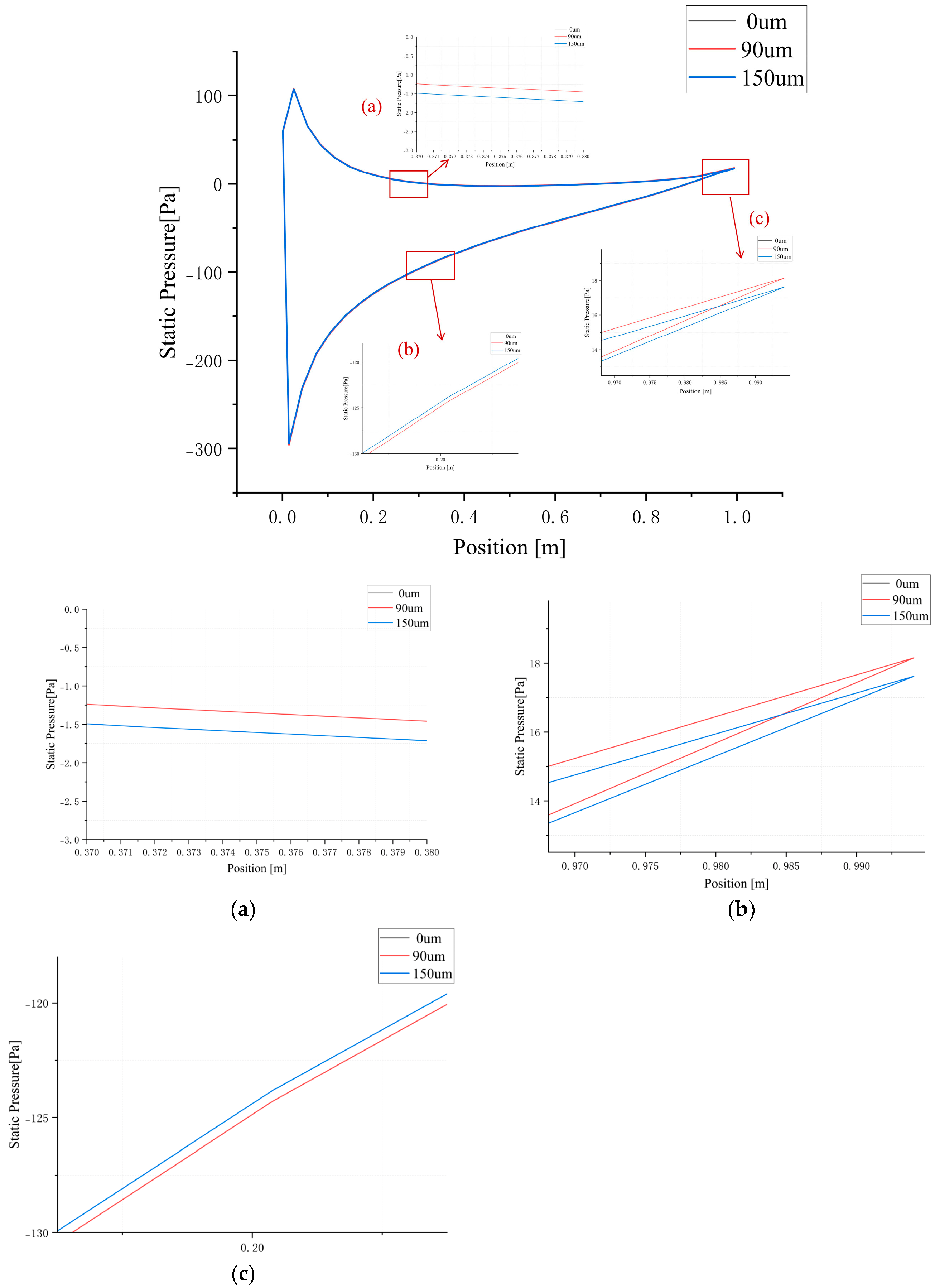

3.2.2. Particle Density Erosion Analysis Considering the Stokes Number

To explore the impact of particle density on wind turbine blade erosion in real-world conditions, dust samples were collected from the airfoils of a wind farm in a certain region of Xinjiang and subjected to physical property analysis. The composition of the particles was analyzed using XRD, and by comparing with standard PDF cards, it was determined that the dust mainly consisted of quartz, magnesite, and limestone. Therefore, these three substances will be used as materials for analyzing the effect of particle density on wind turbine erosion in subsequent studies. Among them, the density distribution of silicon dioxide, calcium carbonate, and magnesium oxide is set at 2650 kg/m

3, 2800 kg/m

3, and 3580 kg/m

3, respectively. Bagnold [

48] explicitly adopted 2650 kg/m

3 as the standard density value for sand particles in his classic wind tunnel experiments and theoretical derivations. Shao [

49] clearly pointed out that the typical density of sand grains is 2650 kg/m

3 when discussing particle kinetic parameters.

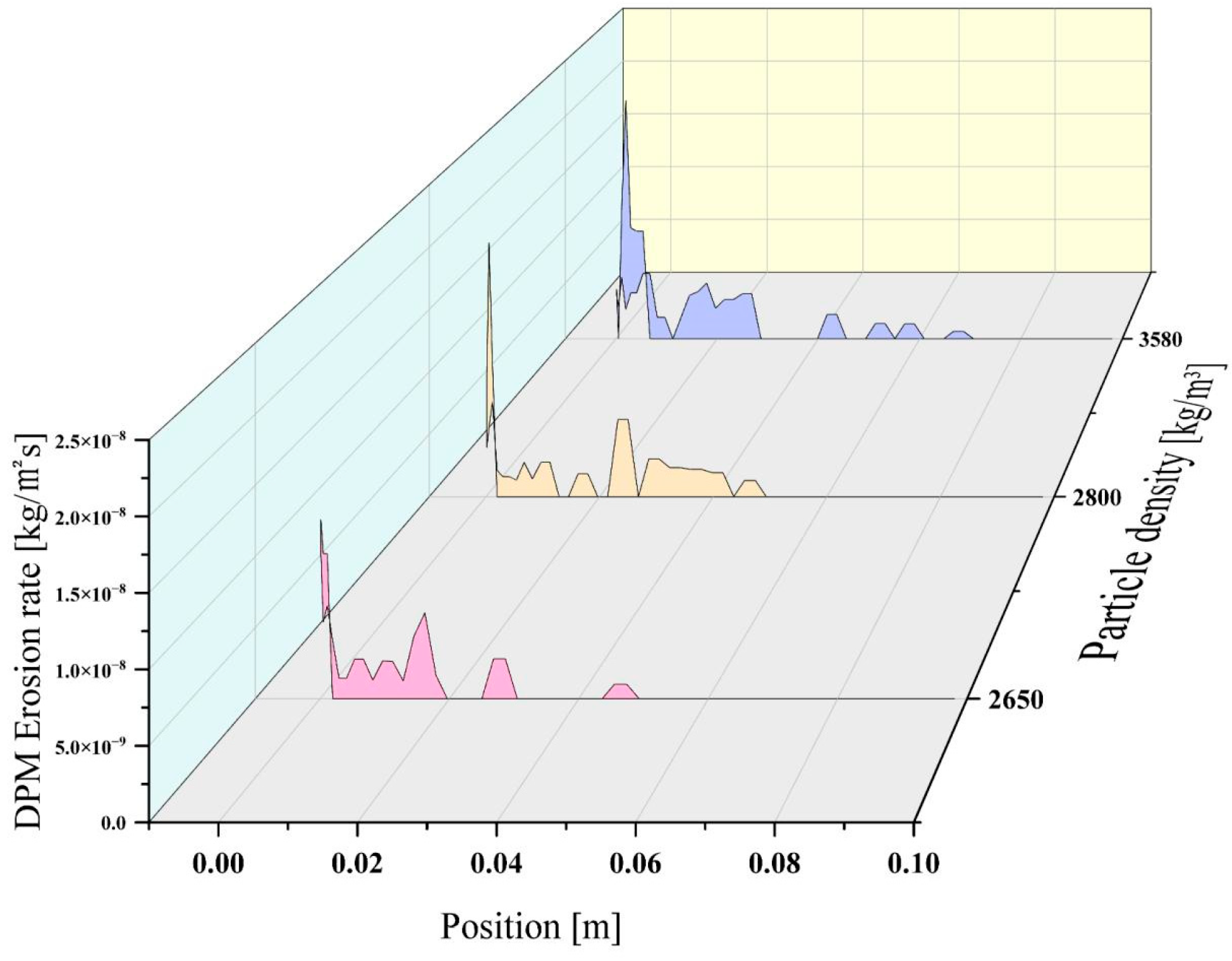

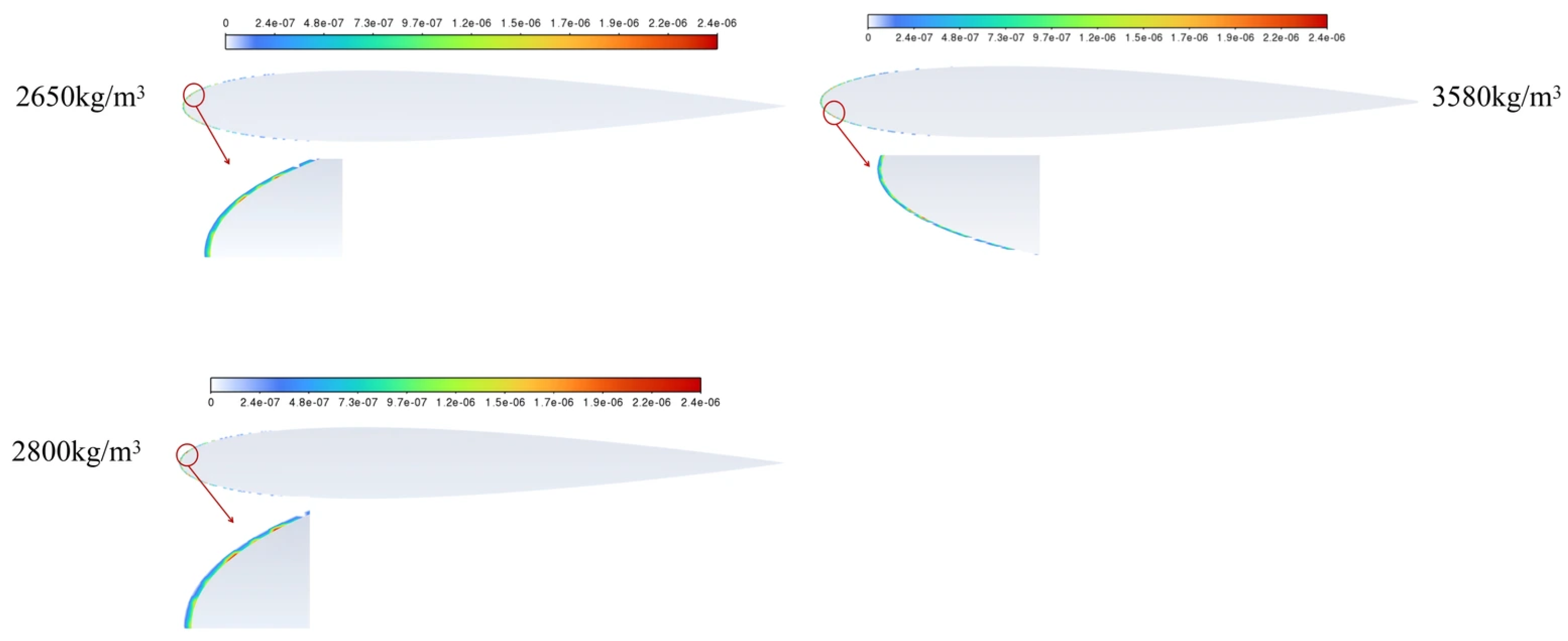

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 show the erosion rate distribution and erosion cloud map for particles with densities of 2650 kg/m

3, 2800 kg/m

3, and 3580 kg/m

3, respectively, and a particle size of 50 μm, when the incident velocity is 3.5 m/s and

Stk << 1. Erosion occurs within the first 1% of the chord length of the airfoil under all three particle density conditions. As shown in the figure, when the particle density is 2650 kg/m

3,the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.26 × 10

−8 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 3.98 × 10

−10 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0001 m from the leading edge. As the particle density increases, when the density reaches 2800 kg/m

3, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.04 × 10

−8 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 4.32 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0005 m from the leading edge. When the particle density increases to 3580 kg/m

3, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.14 × 10

−8 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 4.53 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0019 m from the leading edge.

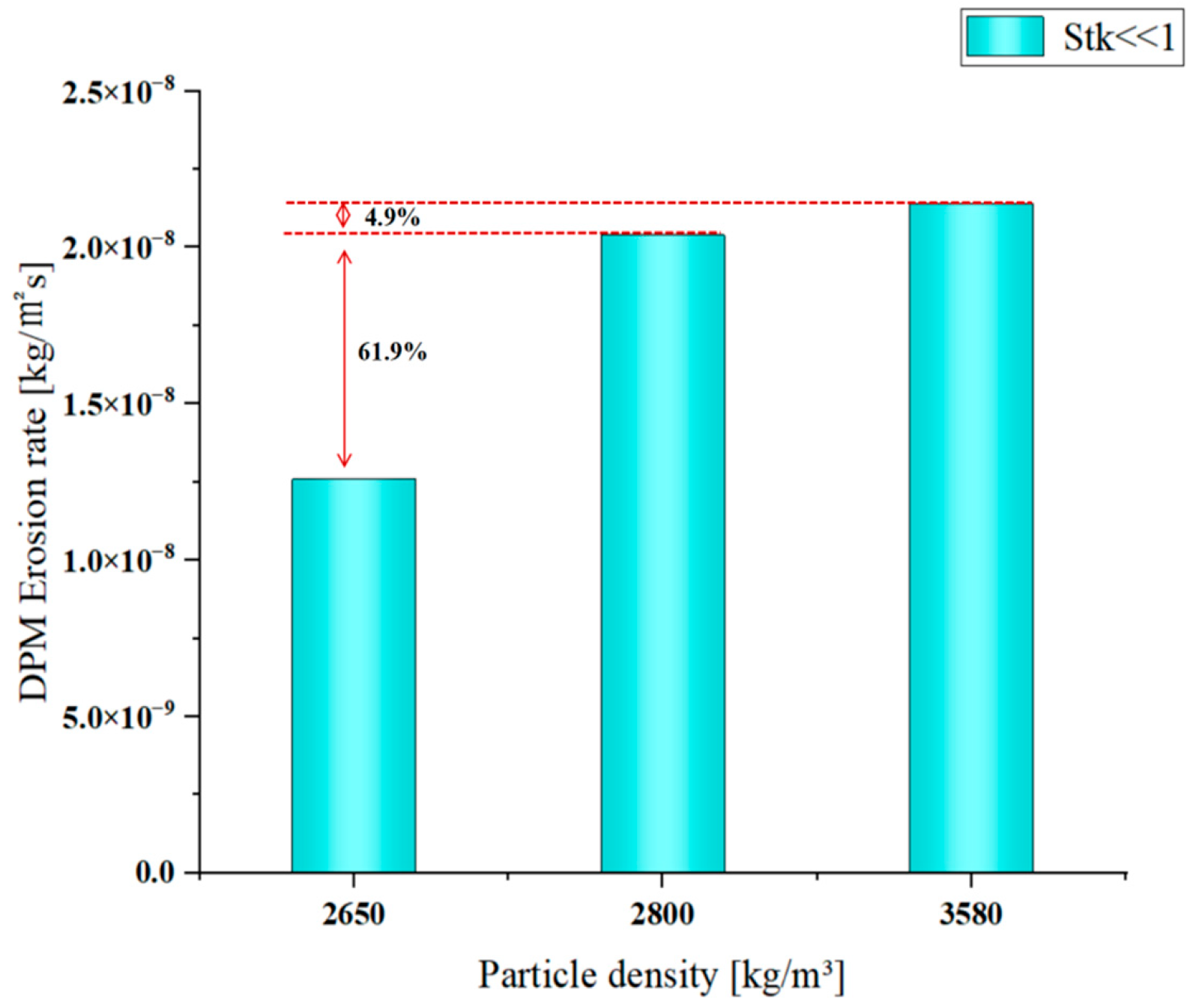

Based on particles with a density of 2650 kg/m

3, when the particle density increases to 3580 kg/m

3, the maximum erosion rate increases by only 69.8%. As shown in

Figure 18 and

Figure 20, with increasing particle density, both the peak and the average erosion rate on the airfoil surface increase. As shown in

Figure 20, the location of the highest erosion rate tends to shift slightly backward as density increases. The erosion rate mainly depends on the kinetic energy of the particles hitting the surface and the frequency of impact. When the particle density increases from 2650 kg/m

3 to 3580 kg/m

3, the particle mass increases, resulting in a significant increase in the kinetic energy of the particles impacting the wing. Each impact transfers more energy to the wing surface, resulting in more significant erosion. In addition, because the particle concentration, fluid velocity, and flow field structure did not change, the collision frequency remained unchanged. Therefore, the increase in erosion rate is mainly driven by the increase in kinetic energy. The rearward shift in the maximum erosion rate position is related to the inertial behavior of particles and can be explained by the Stokes number. When

Stk << 1, the particles follow the streamlines, but inertia cannot be ignored. An increase in

Stk indicates that the particles have greater inertia and it is more difficult to follow the curvature of the fluid streamlines. In the flow field of an airfoil with an angle of attack of 6°, the fluid streamlines bend near the leading edge. When the particle density is low, it is easier to follow the streamline, and the impact points are concentrated at the leading edge or slightly forward. When the particle density is high, inertia is stronger, and particles tend to move in a straight line, causing the point of impact to move toward the rear. Therefore, there is a tendency for the location of the highest erosion rate to move backward, while the area of erosion on the wing surface also increases slightly.

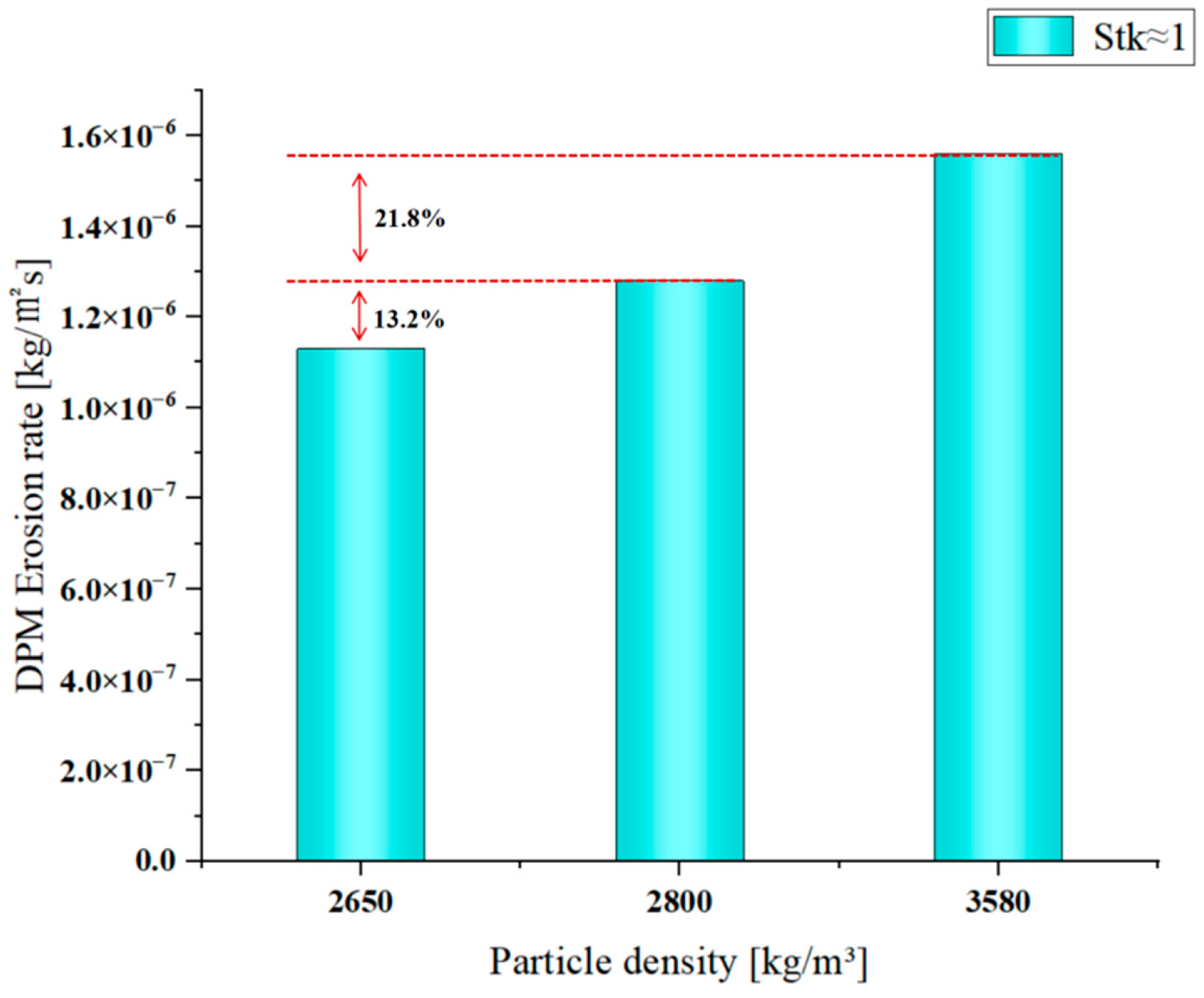

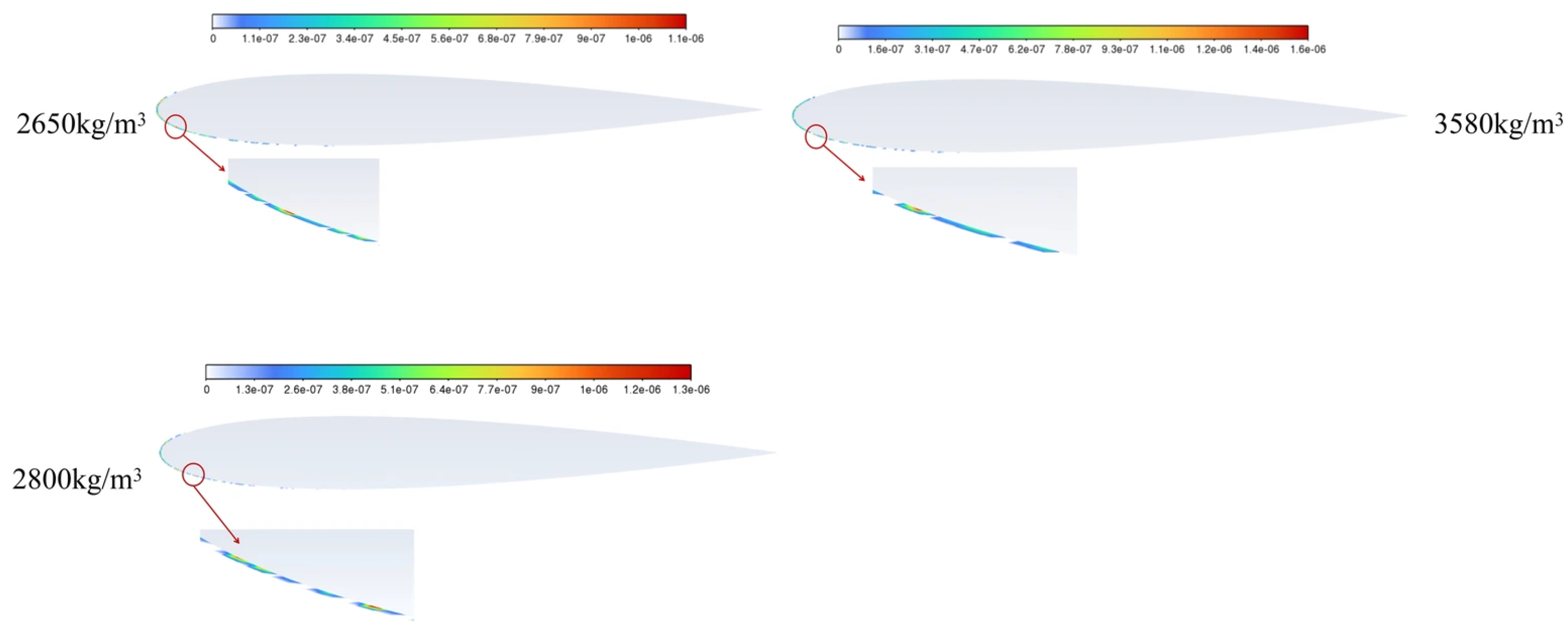

Figure 21,

Figure 22 and

Figure 23 show the erosion rate distribution diagrams, the highest erosion rate bar charts, and the erosion cloud diagrams for particles with densities of 2650 kg/m

3, 2800 kg/m

3, and 3580 kg/m

3, respectively, as well as a particle size of 100 μm, when the incident velocity is 11.5 m/s and

Stk ≈ 1. As illustrated in the figure, compared with particle erosion at low speeds, erosion range of the three types of particles expanded under conditions of increased speed and particle size. The erosion area has expanded to within the first 30% of the chord length of the airfoil. As shown in the figure, when the particle density is 2650 kg/m

3, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.13 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing surface is 4.53 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.03 m from the leading edge. As the particle density increases, when the density reaches 2800 kg/m

3, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.28 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 3.31 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.055 m from the leading edge. When the particle density increases to 3580 kg/m

3 the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.56 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 3.36 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.03 m from the leading edge. It can be seen that as the particle density increases, both the peak and the average erosion rate on the wing surface increase. The location of the highest erosion rate tends to shift slightly backward as density increases. Based on particles with a density of 2650 kg/m

3, when the particle density increases to 3580 kg/m

3, the maximum erosion rate increases by only 38%.

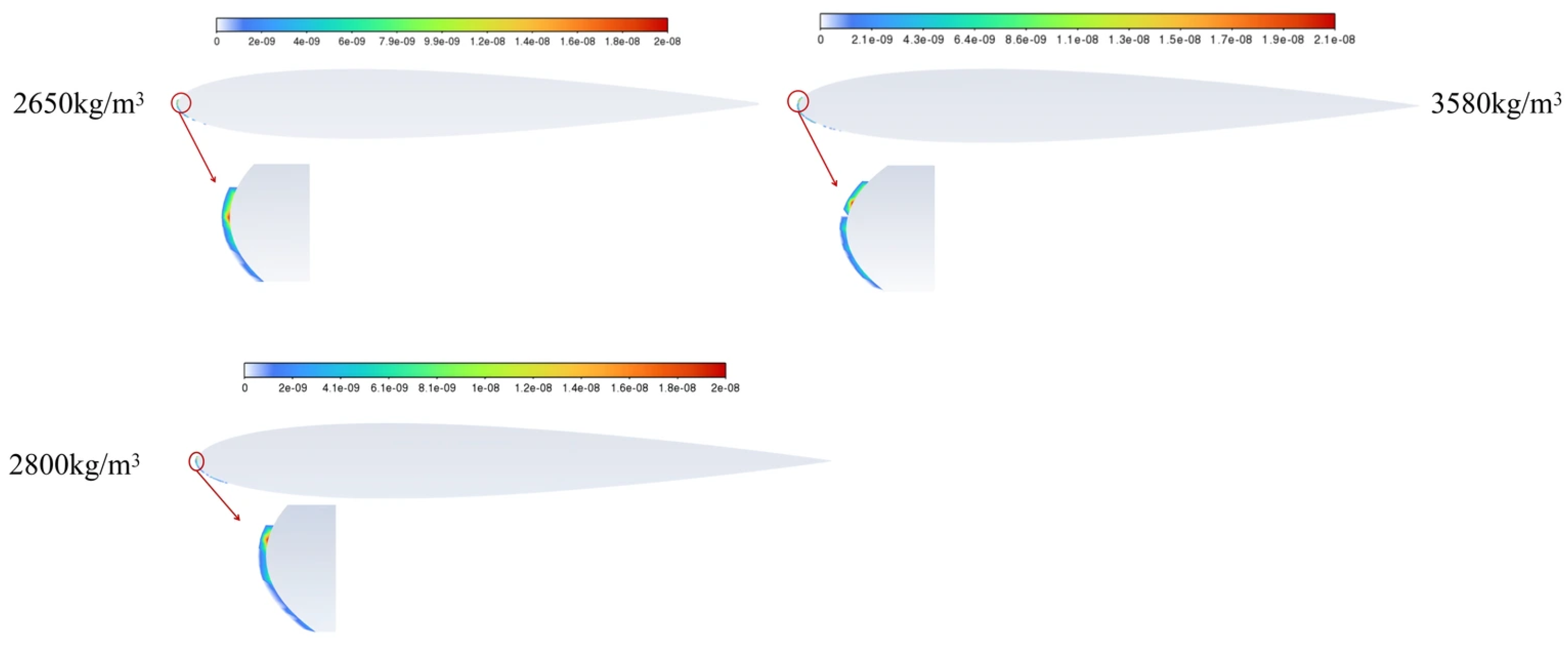

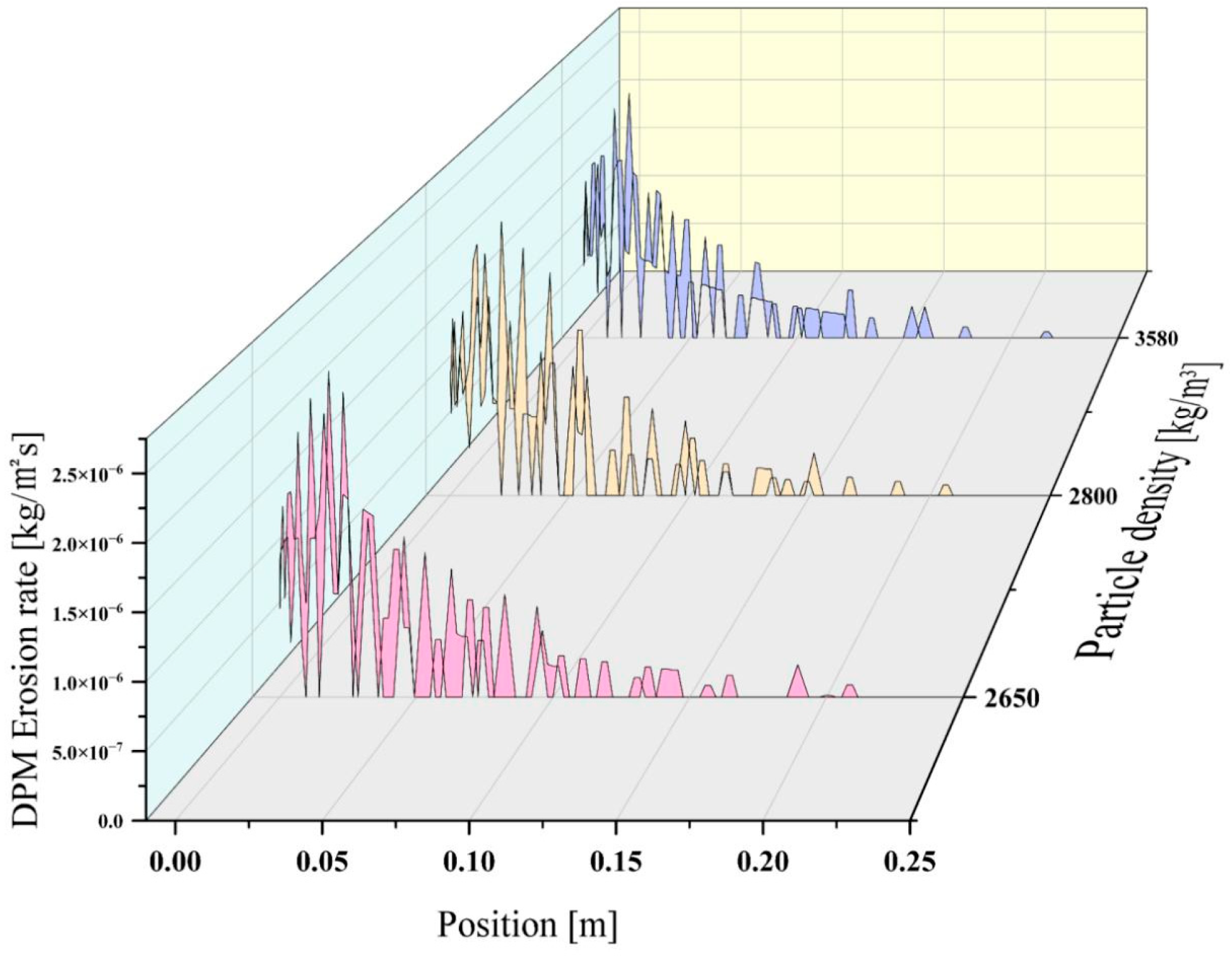

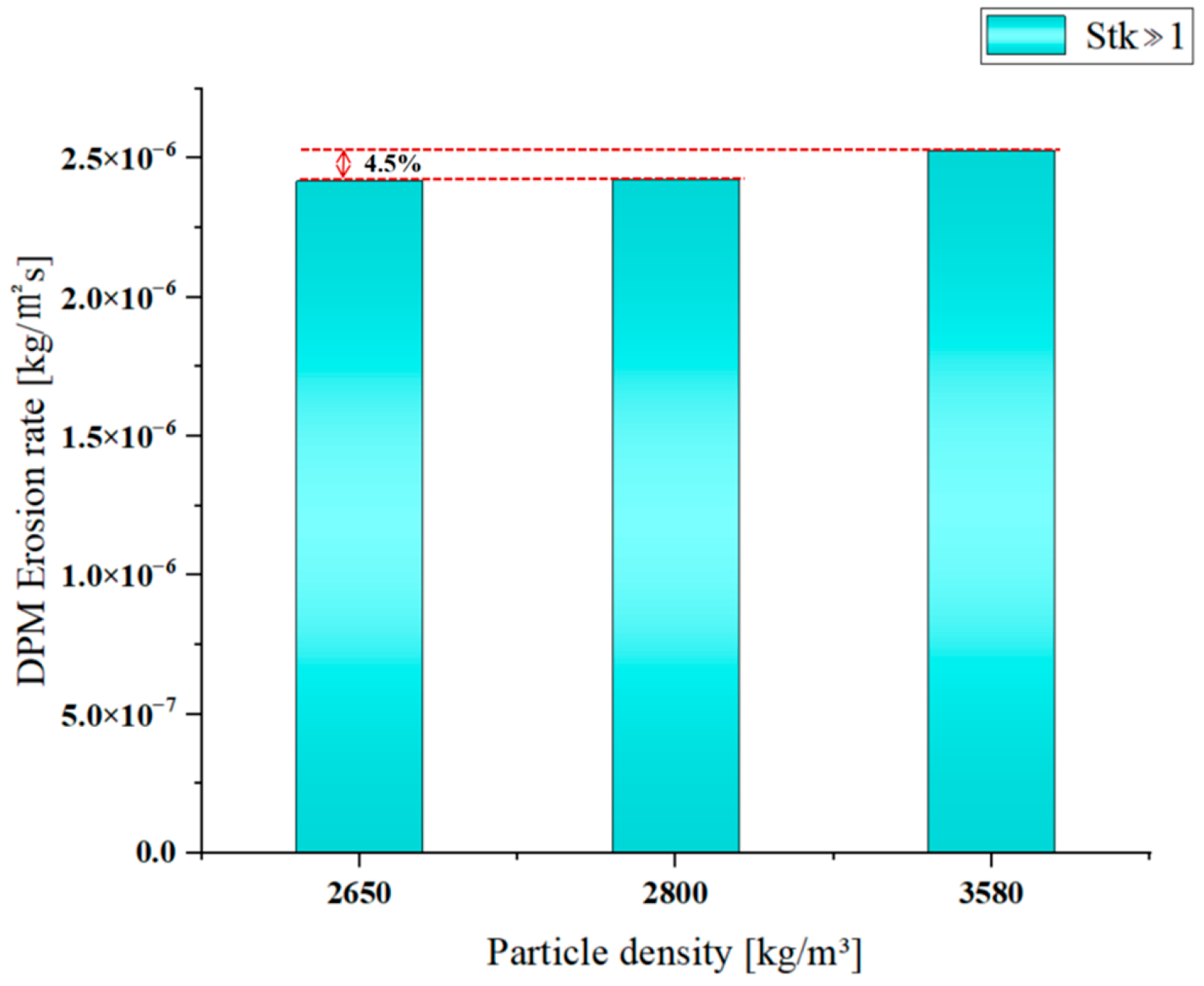

Figure 24,

Figure 25 and

Figure 26 show the erosion rate distribution, the highest erosion rate bar chart, and the erosion cloud chart for particles with densities of 2650 kg/m

3, 2800 kg/m

3, and 3580 kg/m

3, respectively, and a particle size of 300 μm, when the incident velocity is 15 m/s and

Stk >> 1. As shown in the figure, when the particle density is 2650 kg/m

3, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.417 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 7.69 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.017 m from the leading edge. As the particle density increases, when the density reaches 2800 kg/m

3, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.424 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 7.86 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.021 m from the leading edge. When the particle density increases to 3580 kg/m

3, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.53 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 7.78 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.21 m from the leading edge. It can be seen that as the particle density increases, both the maximum erosion rate and the average erosion rate on the wing surface change very little. The location of the highest erosion rate tends to shift slightly backward as density increases. Based on particles with a density of 2650 kg/m

3, when the particle density increases to 3580 kg/m

3, the maximum erosion rate increases by only 4.5%.

The simulation results show that as particle size and impact velocity increase, the effect of particle density on erosion rate significantly weakens. From the perspective of particle characteristics, the Stokes number effect dominates the motion trajectory: when the particle size and velocity are small, Stk is low, and the particles mainly move along the streamlines, with a limited number of particles colliding with the wall surface. At this point, increasing the particle density significantly increases Stk, causing more particles to deviate from the streamline and collide with the wall surface, thereby significantly increasing the erosion rate. However, when the particle size and velocity increase to Stk >> 1, the inertia of the particles dominates their motion, and almost all particles deviate from the streamline control and collide with the wall surface in an approximately straight trajectory. Under these conditions, further increasing the density continues to increase Stk, but the effect on the particle-wall collision probability is negligible. The impact frequency mainly depends on the particle flux rather than the density. Impact kinetic energy dominates the degree of damage: when particle size and velocity are small, particle impact kinetic energy is low, and erosion rate is also low. At this point, increasing the particle density can proportionally increase the impact kinetic energy, thereby significantly improving the erosion rate. However, when the particle size and velocity are sufficiently large, the impact kinetic energy increases dramatically, with kinetic energy ∝ρd3v2, and the damage caused by a single collision is significantly enhanced. In this high-kinetic energy region, the relative change in kinetic energy caused by density changes (Δρ/ρ) is insignificant compared to the enormous kinetic energy base effect caused by changes in particle size (d3) and velocity (v2). At the same time, the sensitivity of erosion rates to changes in kinetic energy may tend to saturate at high kinetic energy levels. Therefore, the relative influence of particle density on erosion rate is more significant under conditions of low particle size and low velocity. However, under conditions of high particle size and high velocity, this effect weakens, and the erosion rate is mainly determined by particle flux, particle size, and velocity, with density becoming a secondary parameter

3.2.3. Particle Size Erosion Analysis Considering the Stokes Number

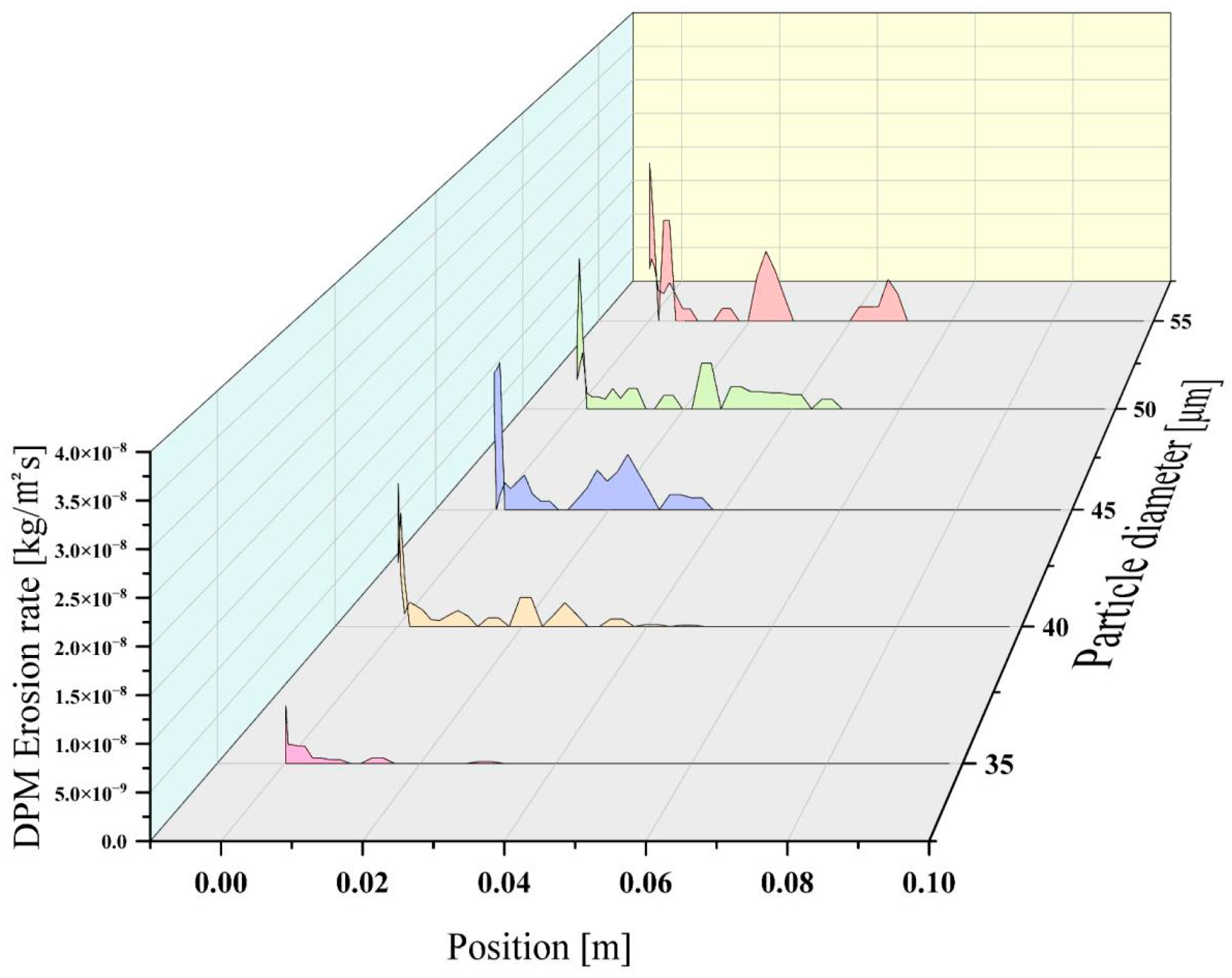

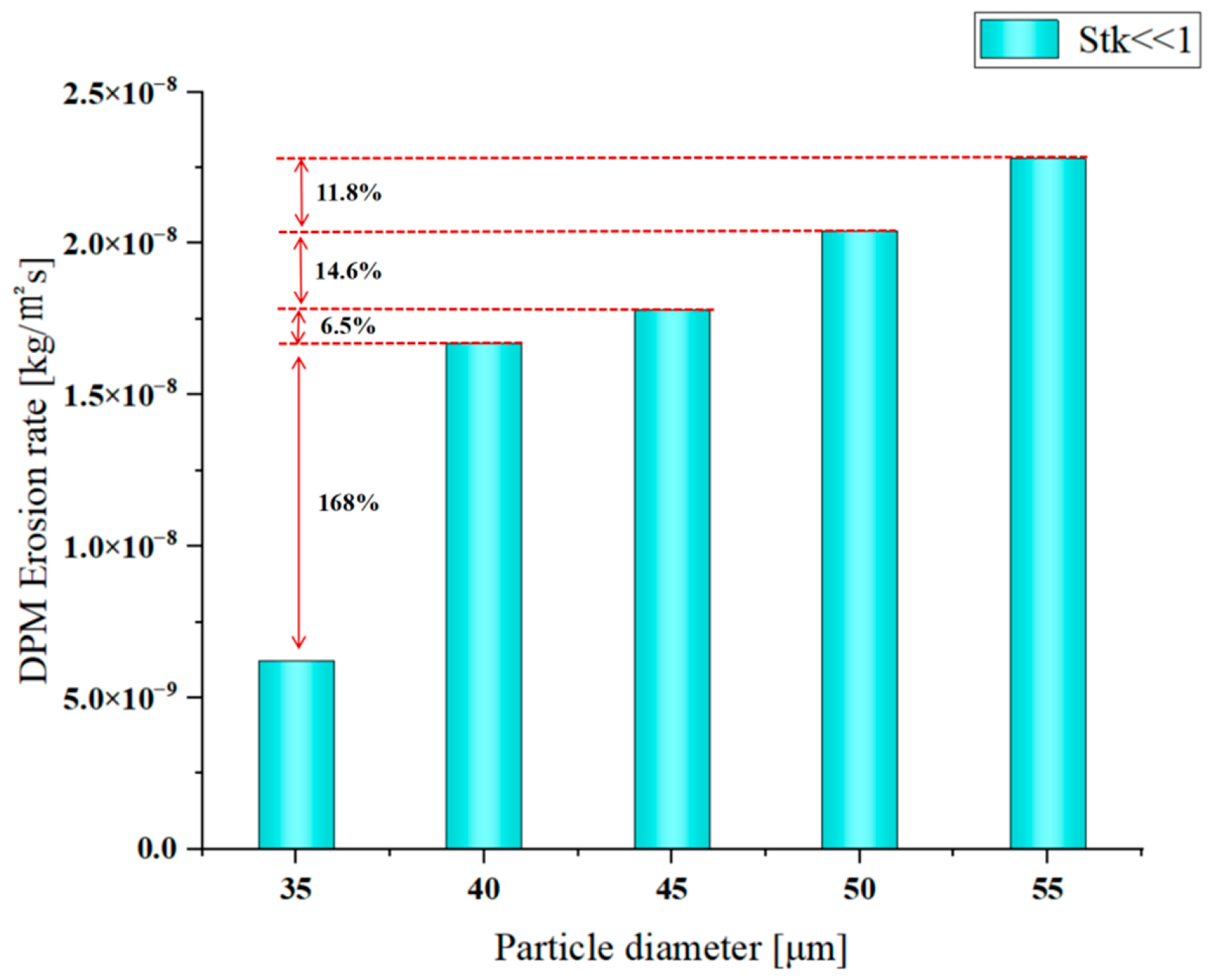

Figure 27 shows the evolution of erosion within the low Stokes number regime (

Stk << 1), investigated using particles of 35, 40, 45, 50, and 55 μm in diameter. These particle sizes were selected to systematically vary the Stokes number while remaining within the low-inertia regime. As shown in the figure, when the particle size is 35 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 6.23 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s, and the average erosion rate across the wing surface is 1.35 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. The erosion occurs at a distance of 0.0001 m from the leading edge of the airfoil. As the particle size increases, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.67 × 10

−8 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 2.99 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0001 m from the leading edge. When the diameter grows to 45 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.78 × 10

−8 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 3.45 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0005 m from the leading edge. When the diameter grows to 50 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.04 × 10

−8 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate across the wing is 3.93 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.0005 m from the leading edge. When the diameter grows to 55 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.28 × 10

−8 kg/m

2s, the average erosion rate of the wing is 4.72 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. The erosion occurs at a distance of 0.0005 m from the leading edge of the airfoil. As shown in

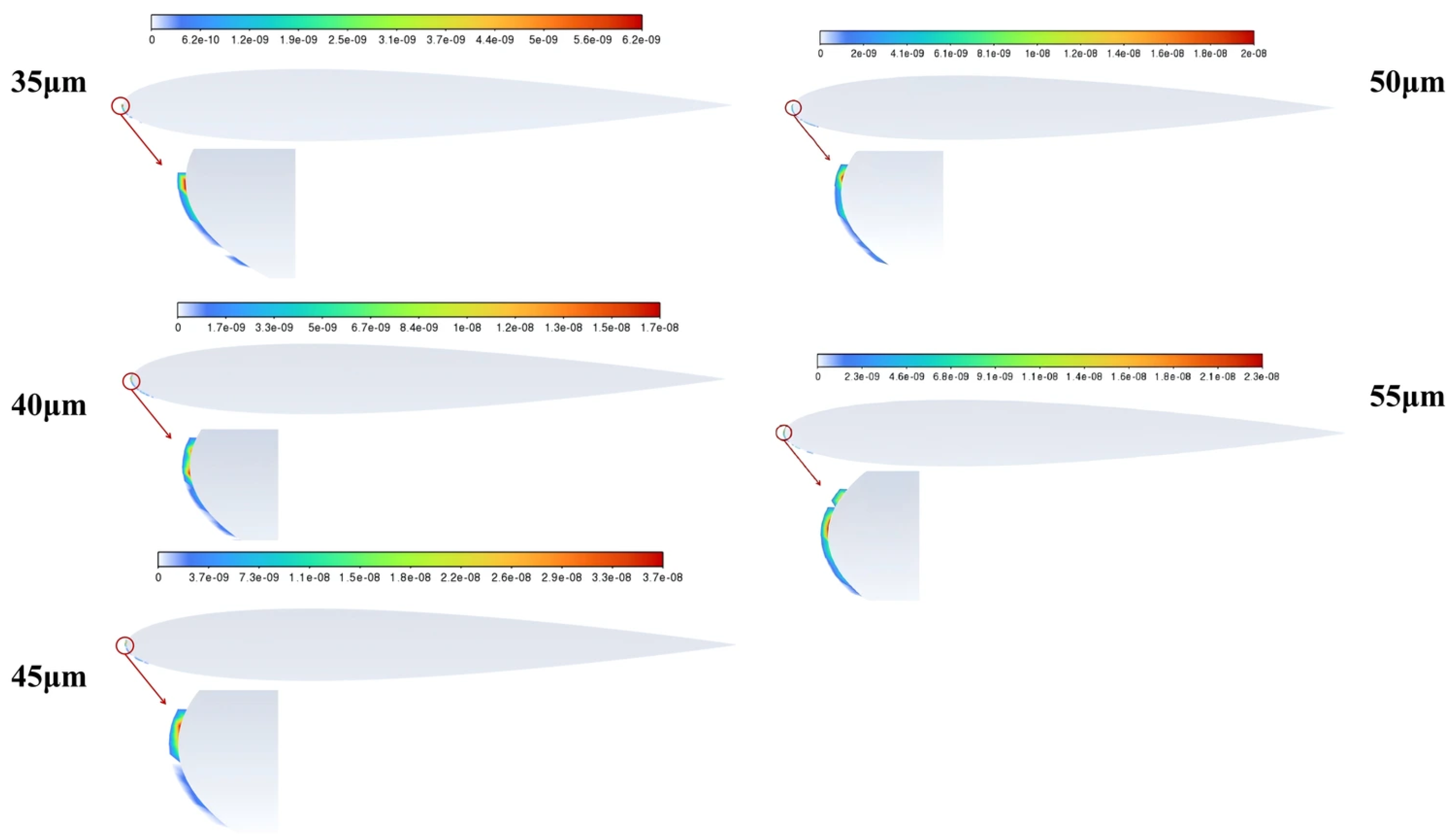

Figure 27 and

Figure 28, within the low Stokes number regime (Stk << 1), both the maximum and the average erosion rate exhibit a strong positive correlation with the Stokes number. Since the Stokes number scales with the square of the particle diameter, this trend manifests as a significant increase in erosion with increasing particle size. The highest erosion rate occurs when the particle size attains 55 μm. This translates to a 265% increase in the maximum erosion rate when the particle size increases from 35 μm to 55 μm, which corresponds to a 2.47 increase in the Stokes number, and the average erosion rate on the wing surface increases by 249%. An increase in particle size from 35 μm to 55 μm significantly exacerbated erosion damage to the surface of the NACA 0012 airfoil. The main manifestations are increased material removal rates and increased depth and severity of damage morphology at the leading edge of the airfoil. This change is mainly driven by the cubic increase in single-particle collision kinetic energy, while also being influenced by the collision efficiency caused by particle inertia. At this point, although the absolute value of

Stk is still much less than 1, the particles can still follow the fluid streamlines relatively well, but the increased Stk causes the particles to be slightly more sensitive to local flow field disturbances. The streamline curvature is relatively large in the stagnation zone at the leading edge of the airfoil and in the reverse pressure gradient zone on the upper surface. Larger Stk causes particles to deviate slightly from the streamline due to limited inertia, increasing the probability of collision with the airfoil surface. As the particle size increases, the particle mass increases. When the impact velocity remains unchanged, the kinetic energy transmitted to the material surface by a single impact is greatly increased. Higher impact energy is more likely to cause increased erosion.

As shown in

Figure 29, the erosion area expands slightly as the particle size increases. The minor enlargement of the erosion region results from the growth in particle dimensions. Essentially, it is the non-linear manifestation in space of the local streamline deviation effect caused by the increase in particle relaxation time. Although the global

Stk is still small, in specific high-gradient flow field regions induced by airfoil geometry and angle of attack, increased inertia enhances the sensitivity of particle trajectories to local disturbances, resulting in a slight broadening of the spatial distribution function of collision efficiency. This is particularly evident in areas with high streamline curvature or weak separation at the boundary. It shows that even under low Stokes number conditions, particle size changes can still have a certain impact on the spatial distribution of collisions by modulating the interaction between particles and shear layers.

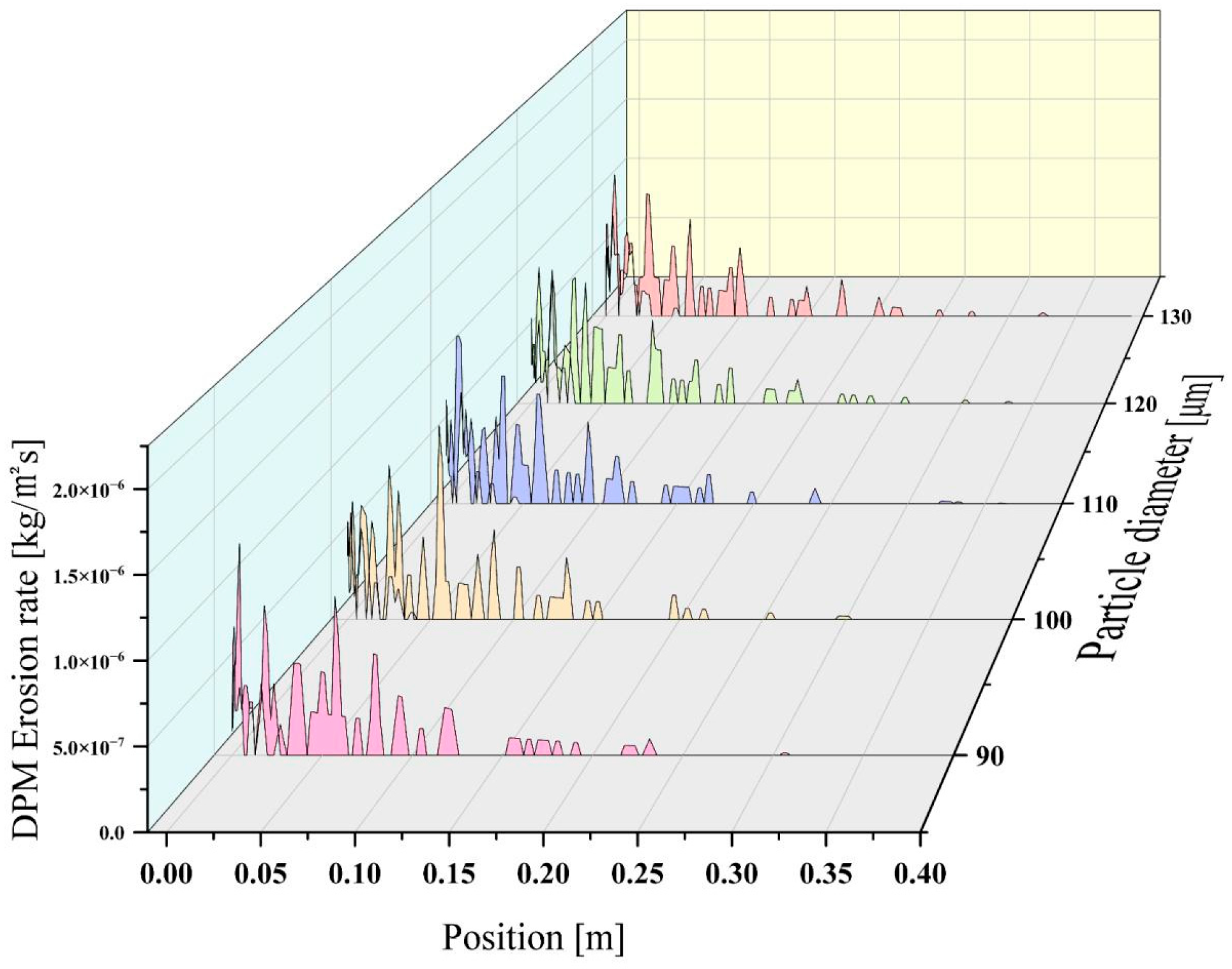

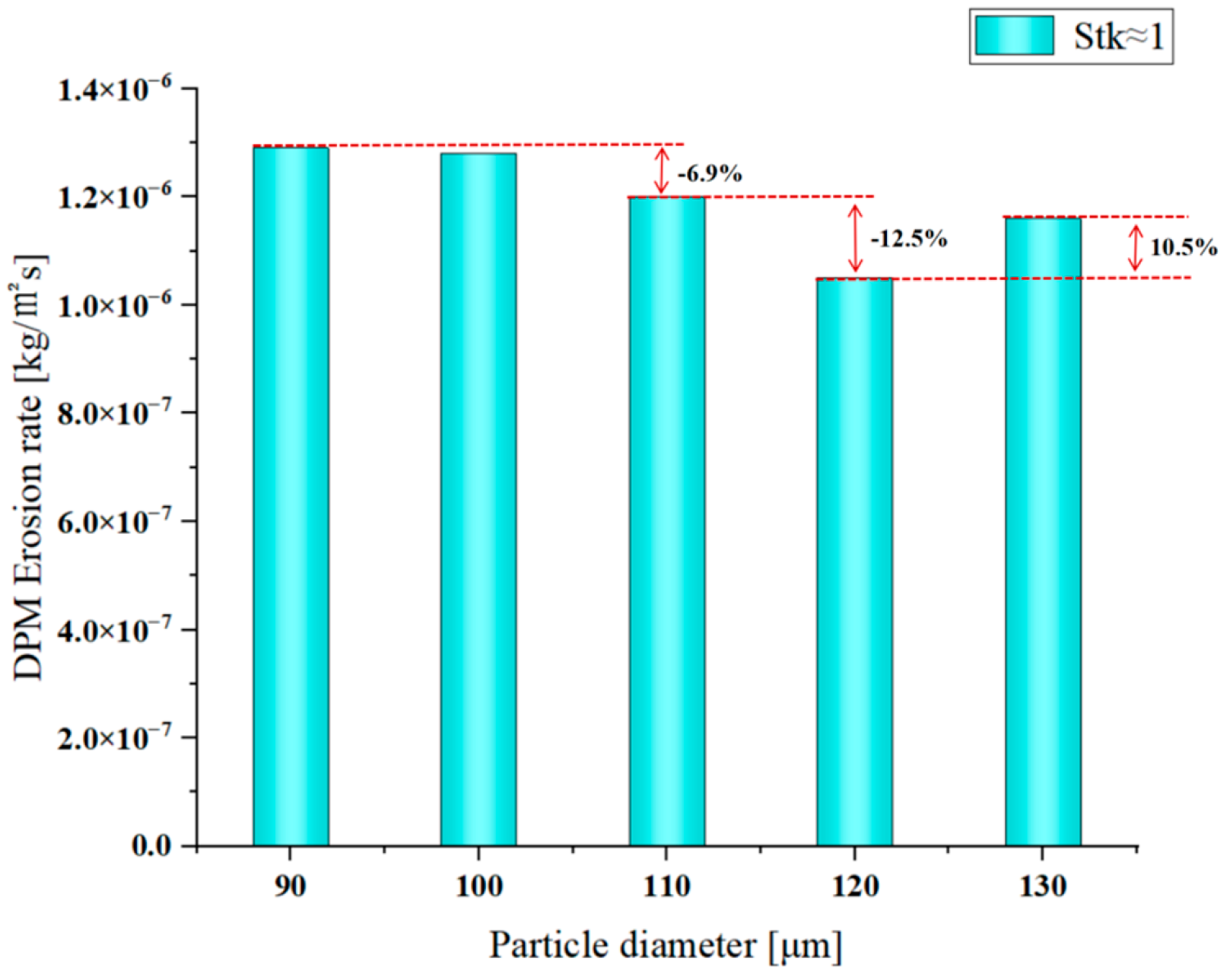

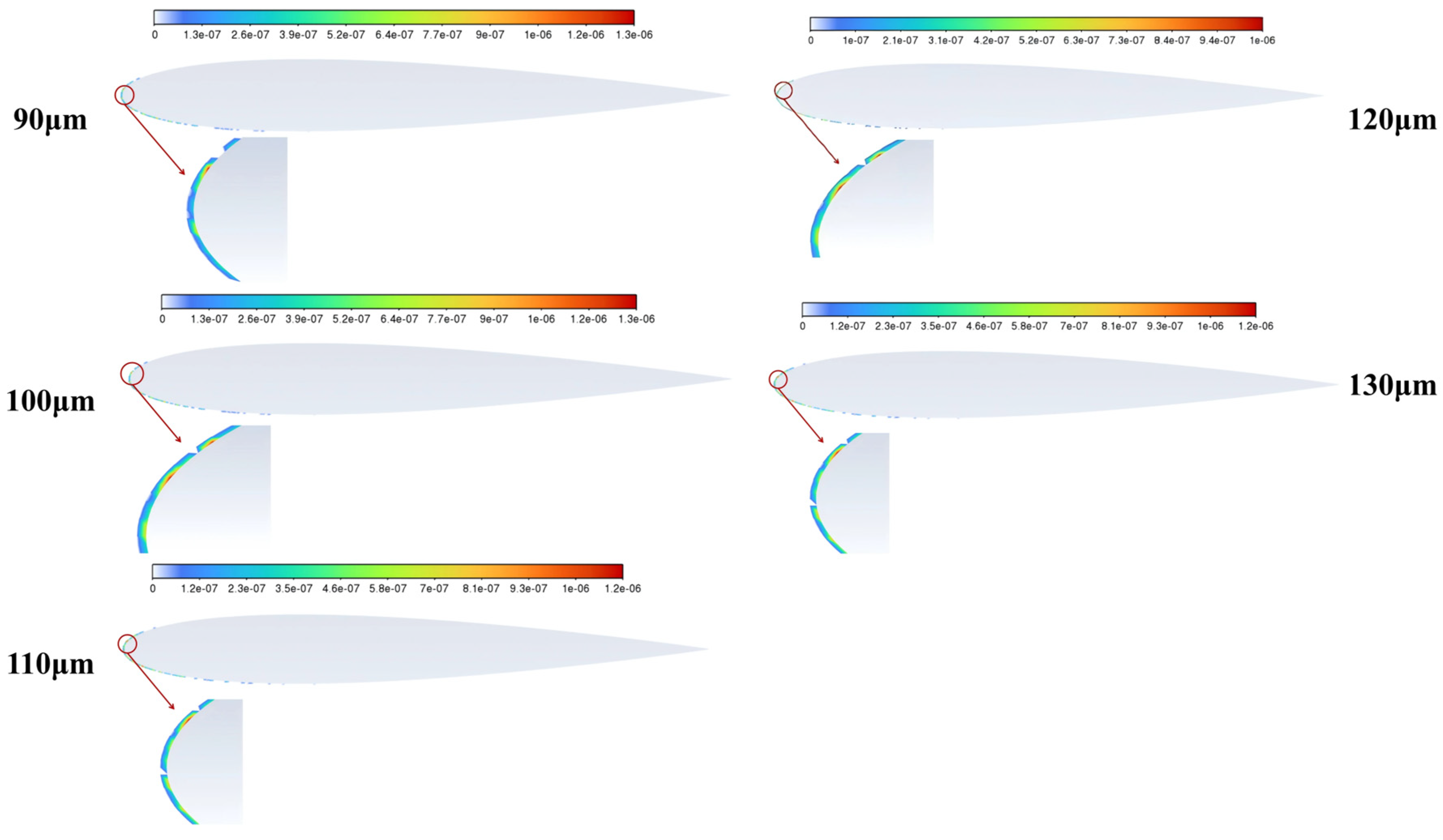

Figure 30,

Figure 31 and

Figure 32 show the erosion rate distribution diagrams, maximum erosion rate bar charts, and erosion cloud diagrams for particles with particle sizes of 90 μm, 100 μm, 110 μm, 120 μm, and 130 μm, respectively, under conditions of a particle density of 2800 kg/m

3 and an incident velocity of 11.5 m/s, with

Stk ≈ 1. As shown in the figure, when the particle size is 90 μm, the highest erosion rate is 1.29 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate on the airfoil is 2.95 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.005 m from the leading edge. As the particle size increases, when the diameter grows to 100 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.28 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate on the surface is 3.27 × 10

−9 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.005 m from the leading edge. When the diameter grows to 110 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.2 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate on the airfoil is 3.27 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.008 m from the leading edge. When the diameter grows to 120 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.05 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate on the airfoil is 3.4 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.005 m from the leading edge. When the diameter grows to 130 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 1.16 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. The average erosion rate on the airfoil is 3.41 × 10

−7 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.006 m from the leading edge. It is evident that the maximum erosion rate in the transition regime (

Stk ≈ 1) peaks at a critical Stokes number of

Stk ≈ 0.8. This peak effect is demonstrated by comparing different particle sizes: the erosion rate for 90 μm particles (

Stk = 0.8) is 21% higher than that for 120 μm particles (

Stk = 1.4). This conclusively shows that the erosion peak is intrinsically governed by the Stokes number itself. The mean erosion rate on the wing surface rises as the particle size increases, with the highest erosion rate occurring at a particle size of 130 μm. This phenomenon originates from the peak effect of collision efficiency in the Stokes number range of 0.5–1.0. When the particle size is 90 μm,

Stk = 0.81, and the inertia of the particles causes them to deviate significantly from the streamlines and collide with the wall surface. This phenomenon originates from the peak effect of collision efficiency coupled with intense preferential concentration in the Stokes number range of 0.5–1.0. It is well-established that particles with

Stk ≈ 1 exhibit the strongest clustering in turbulent flows because their response time matches the characteristic time of the most energetic turbulent eddies. In the context of our airfoil flow, this means that 90 μm particles (

Stk = 0.8) are not only inertially likely to impact the surface but are also actively ‘focused’ into regions like the leading edge stagnation zone and the separated shear layer at higher angles of attack. This dramatic increase in local particle concentration significantly amplifies the impact frequency on specific surface areas, leading to the observed peak in erosion rate.

When the particle size increases to 120 μm,

Stk = 1.44. An increase in the Stokes number leads to a decrease in collision efficiency due to excessive inertia of the particles. Owing to the reduced curvature radius at the leading edge of the NACA 0012 airfoil, the characteristic flow scale is diminished, leading to the formation of small-scale vortices that trap solid particles and thereby intensify localized erosion effects. At the same time, the flow separation effect induced by the angle of attack is enhanced, and the separation vortex generated can significantly enrich particles with

Stk < 1 and intensify local collisions. At the leading edge and separation zone of the NACA0012 airfoil, the erosion rate at

Stk = 0.8 was 21% higher than at

Stk = 1.4, a finding that is highly consistent with the peak erosion behavior reported in the literature [

50], further validating the Stokes number as the governing parameter. These findings further validate the impact of

Stk on the erosion peak behavior of the airfoil.

The data shows that as particle size increases, leading to a higher Stokes number, the average erosion rate tends to increase due to enhanced inertial impaction. The essence lies in the fact that an increase in particle size leads to a significant increase in the Stokes number, thereby weakening the streamline following ability of particles and enhancing the inertial collision effect. An increase in particle size increases the relaxation time of particles, leading to a significant increase in the Stokes number. Particles are more likely to detach from the streamline in areas where the curvature of the wing profile changes, increasing the probability of collision with the wall surface. Increasing the particle size not only enhances the single-impact destruction strength but also increases the effective impact particle flux due to the convergence of particle trajectories toward the windward side, thereby improving particle collision efficiency. In the critical region where Stk ≈ 1, particle motion is in a transitional state between streamline following and inertia domination. At this point, even slight changes in particle size significantly alter the interaction between particles and vortex structures, enhancing the centrifugal effect of particles in the separation shear layer and further promoting particle transport toward the wall. Therefore, under the combined effects of multiple factors, the probability of collisions between the wing surface and particles increases, and the collision effects become more pronounced, leading to an increase in the average erosion rate.

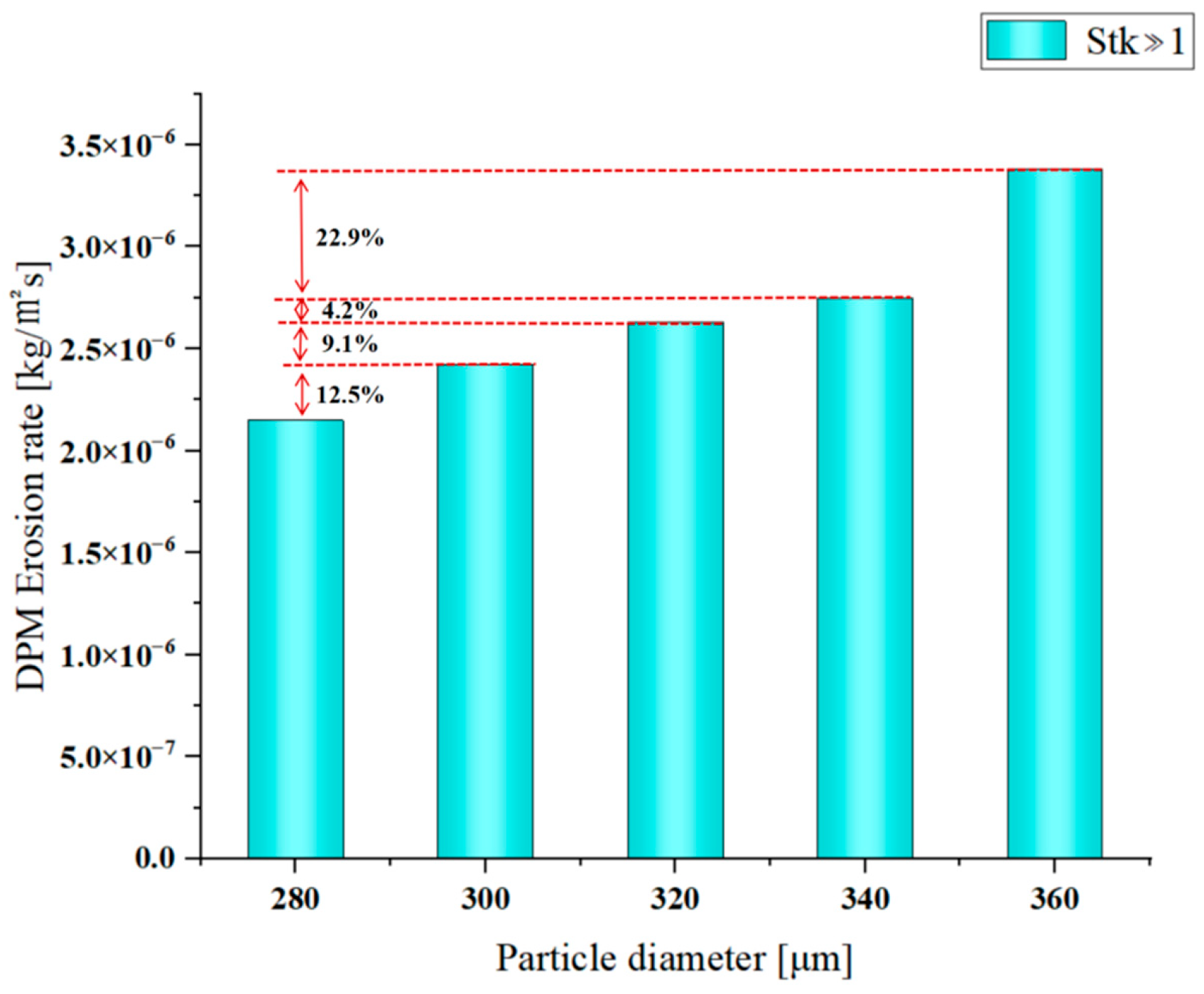

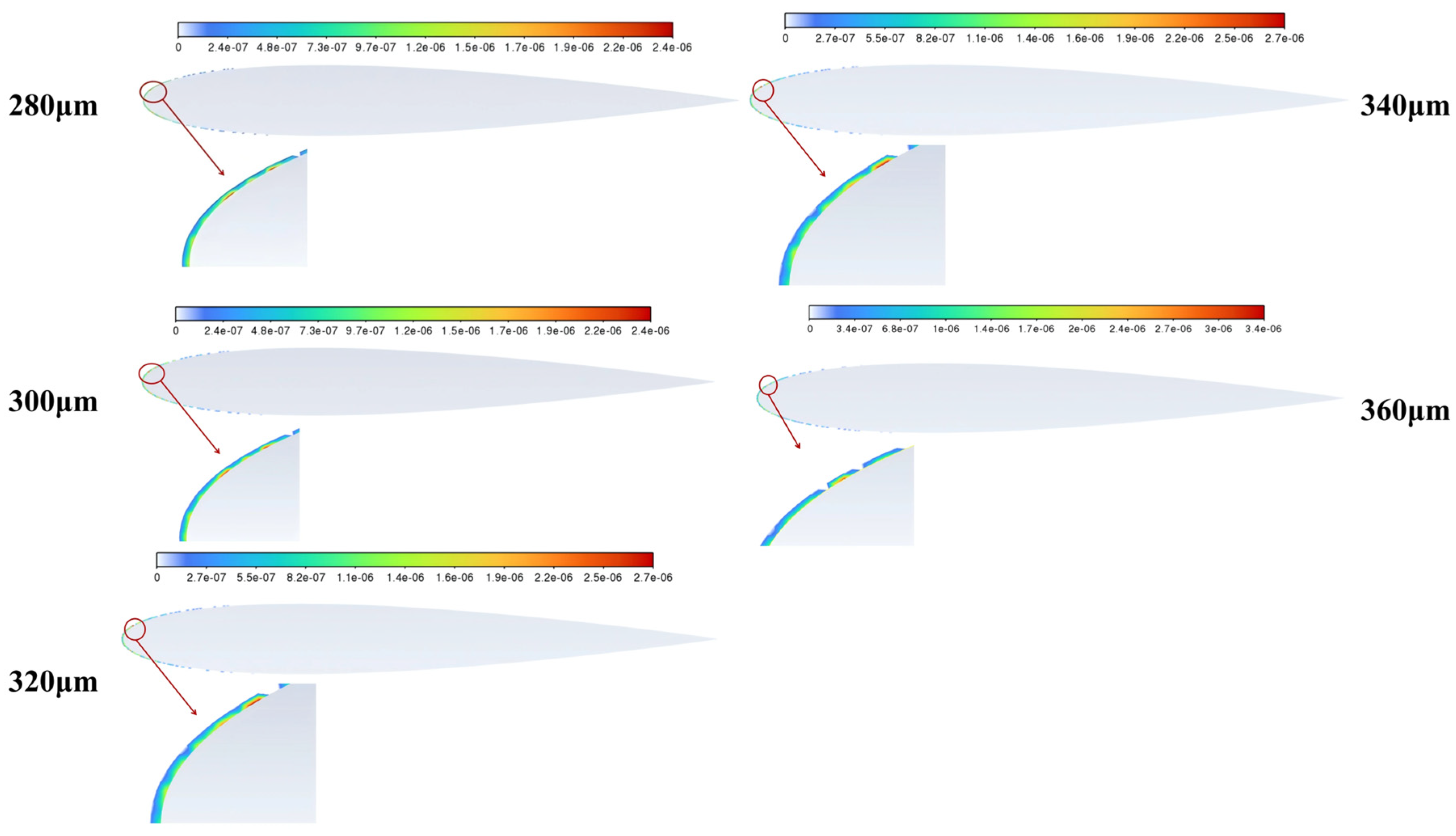

Figure 33,

Figure 34 and

Figure 35 show the erosion rate distribution diagrams, maximum erosion rate bar charts, and erosion cloud diagrams for particles with particle sizes of 280 μm, 300 μm, 320 μm, 340 μm, and 360 μm, respectively, under conditions of a particle density of 2800 kg/m

3 and an incident velocity of 15 m/s, with

Stk >> 1. As shown in the figure, when the particle size is 280 μm, the highest erosion rate is 2.15 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.017 m from the leading edge. As the particle size increases, when it reaches 300 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.42 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.021 m from the leading edge. When it reaches 320 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.64 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.011 m from the leading edge. When it reaches 340 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 2.75 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.012 m from the leading edge. When it reaches 360 μm, the peak erosion rate reaches a value of 3.38 × 10

−6 kg/m

2s. Erosion occurs 0.014 m from the leading edge. It is evident that when

Stk >> 1, the peak erosion rate on the airfoil rises as the particle size becomes larger. Under these conditions, the highest erosion rate occurs when the particle size is 360 μm. This corresponds to a 57% increase in erosion rate when the particle size increases from 280 μm to 360 μm, which is driven by a 65.3% increase in Stokes number and a 112.5% increase in particle kinetic energy. At this point, surface erosion of the NACA0012 airfoil significantly intensifies at an angle of attack of 6°. The depth of erosion pits and material loss rate in the leading edge and approximately 10%–30% of the chord length of the upper surface significantly increase, and the erosion distribution area expands in the chord direction. As the particle size increases from 280 μm to 360 μm, the Stokes number increases by 66%. The inertial effect of the particles is enhanced, and the probability of them deviating from the streamline and colliding with the wall surface is significantly increased. The collision efficiency increases from 60% to 85%, representing a significant increase in collision efficiency. Particle kinetic energy increases cubically, with 360 μm particles having 2.12 times the kinetic energy of 280 μm particles, exacerbating plastic deformation and erosion of the material. Enhanced boundary layer penetration capability allows larger particles to more easily break through the airflow barrier and collide with the surface, especially at an angle of attack of 6°, where a high-speed low-pressure zone forms at the front end of the upper surface, creating a concentrated erosion hot spot. In summary, under the combined effects of particle inertia, increased kinetic energy, and improved boundary layer penetration, an increase in particle size will lead to a significant deterioration in erosion damage to the surface of the NACA 0012 airfoil.