AlN Passivation-Enhanced Mg-Doped β-Ga2O3 MISIM Photodetectors for Highly Responsive Solar-Blind UV Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

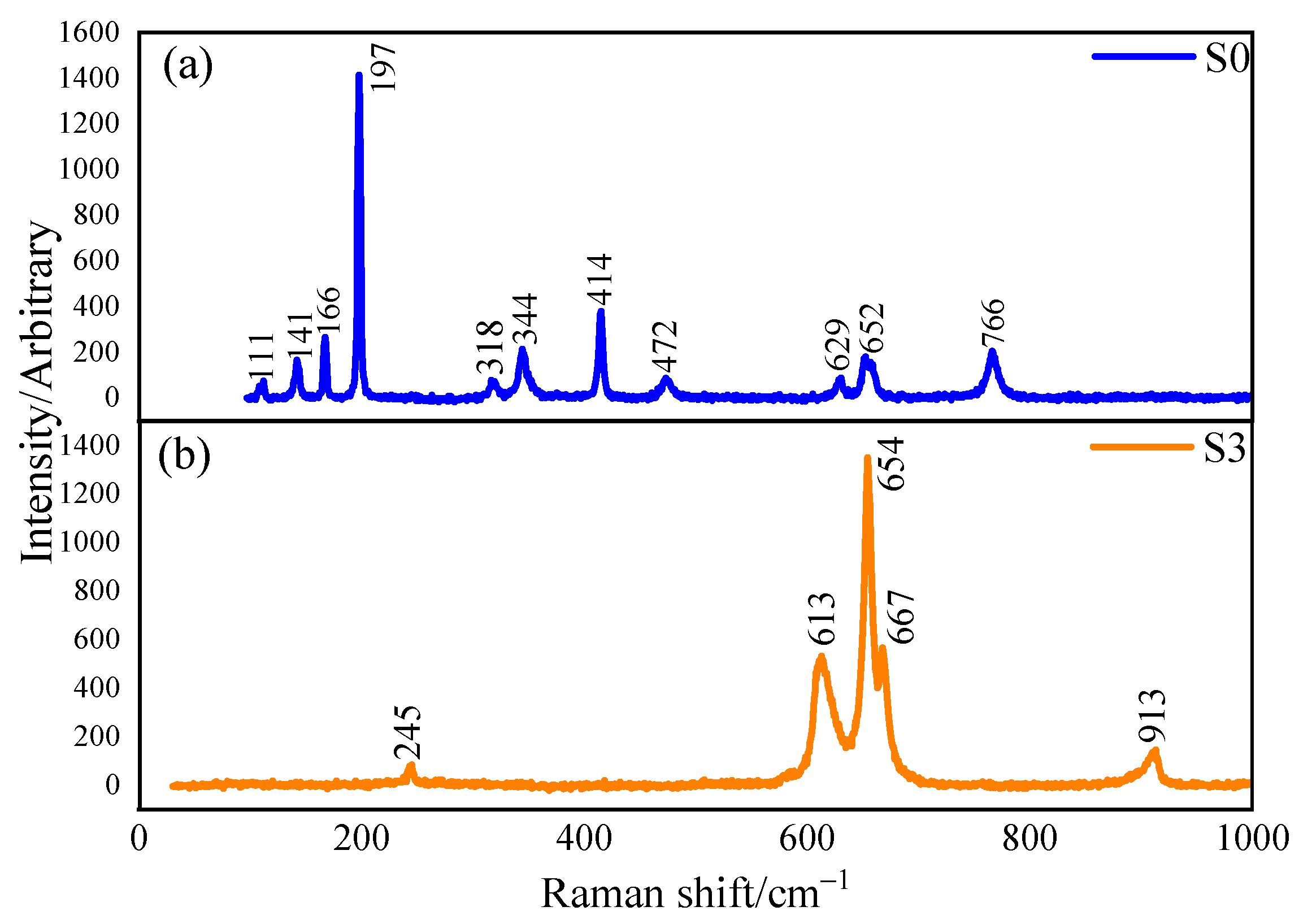

3. Results and Discussions

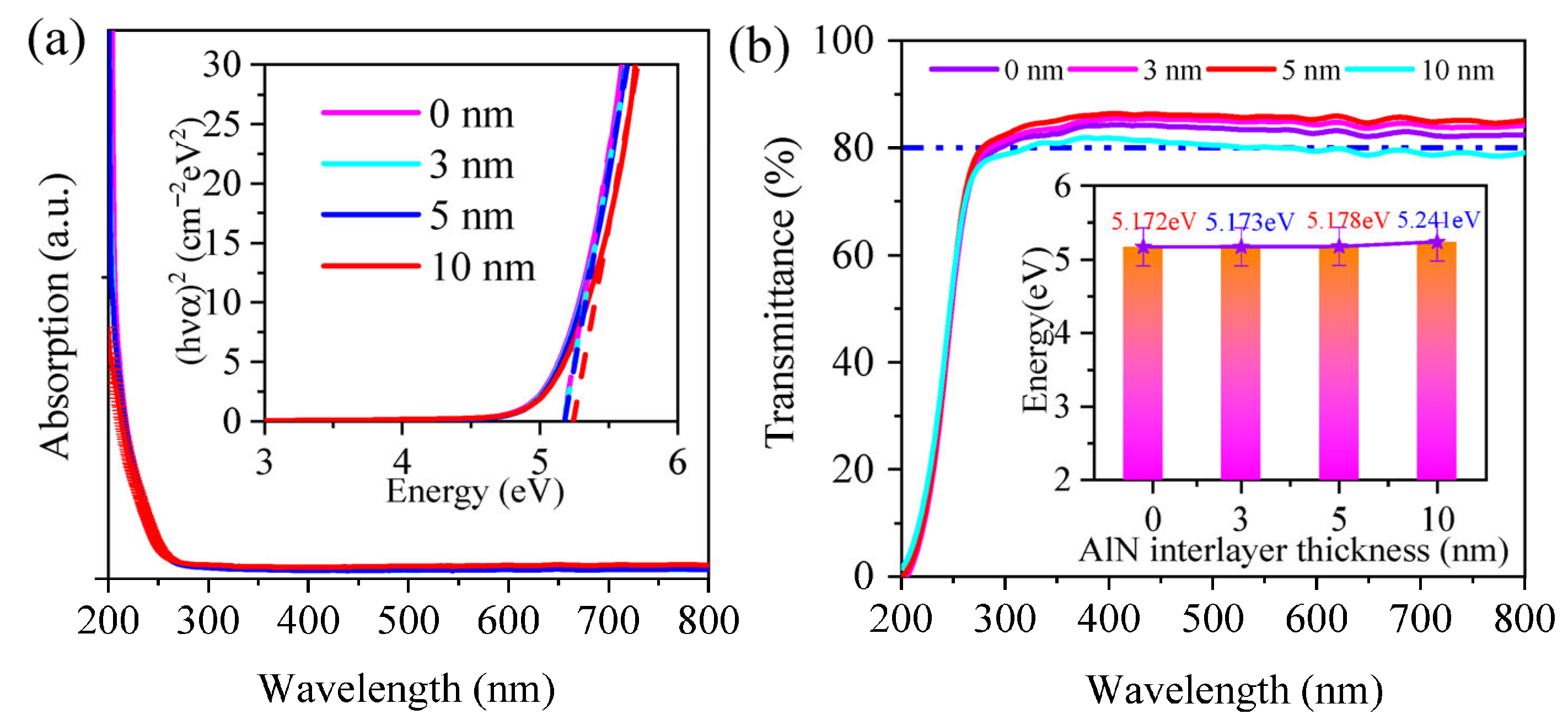

3.1. Light Absorption and Bandgap

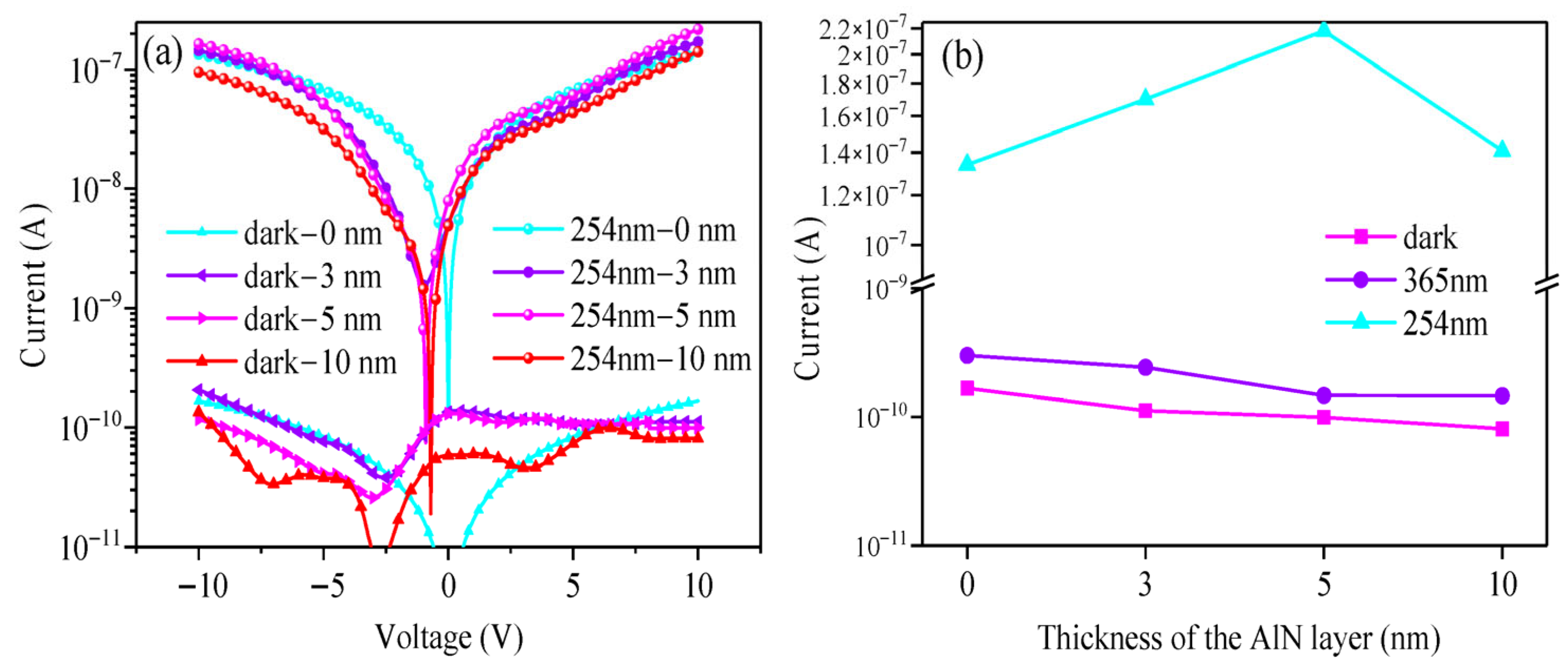

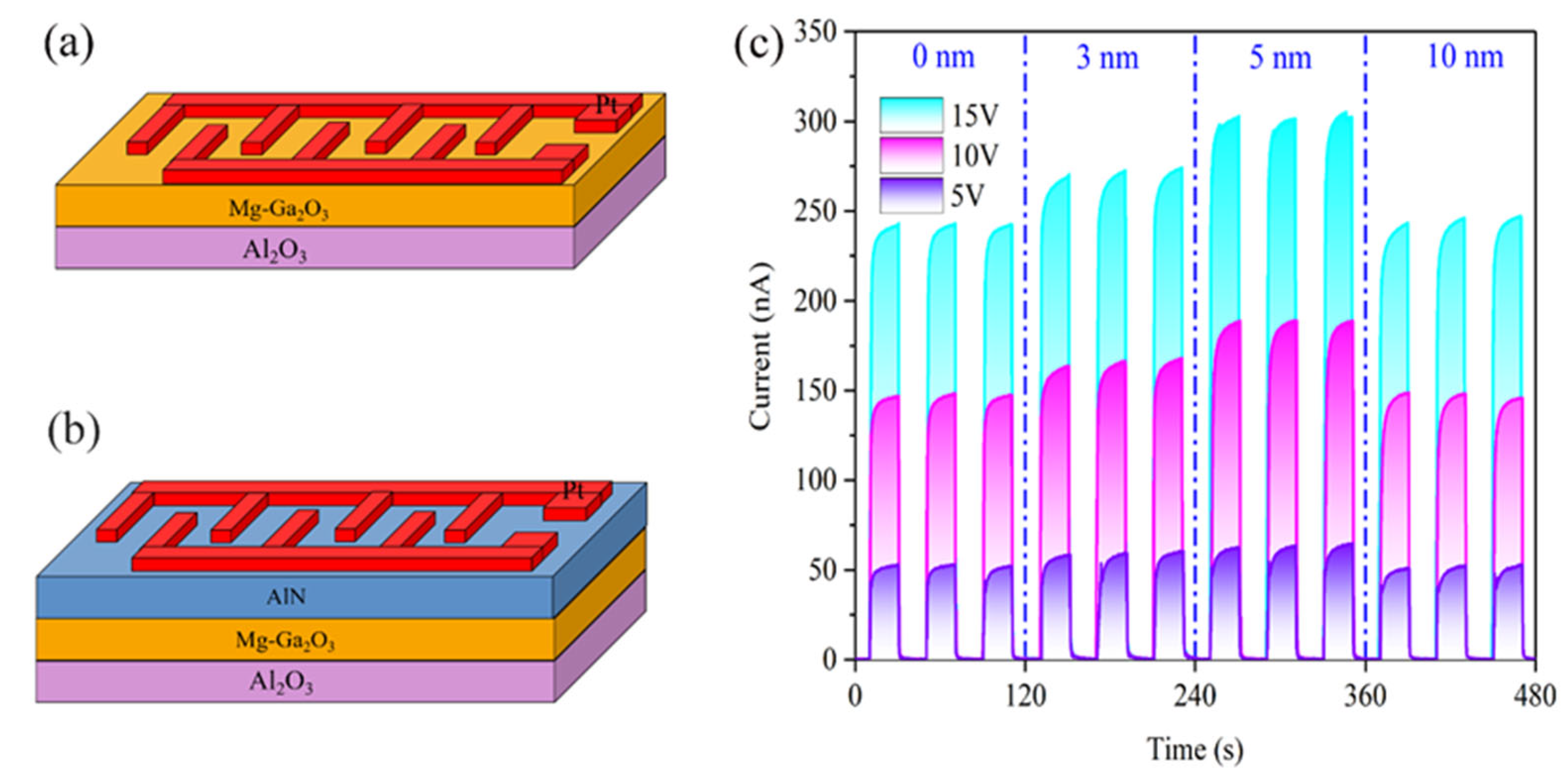

3.2. I-V Curve and I-T Response Curve

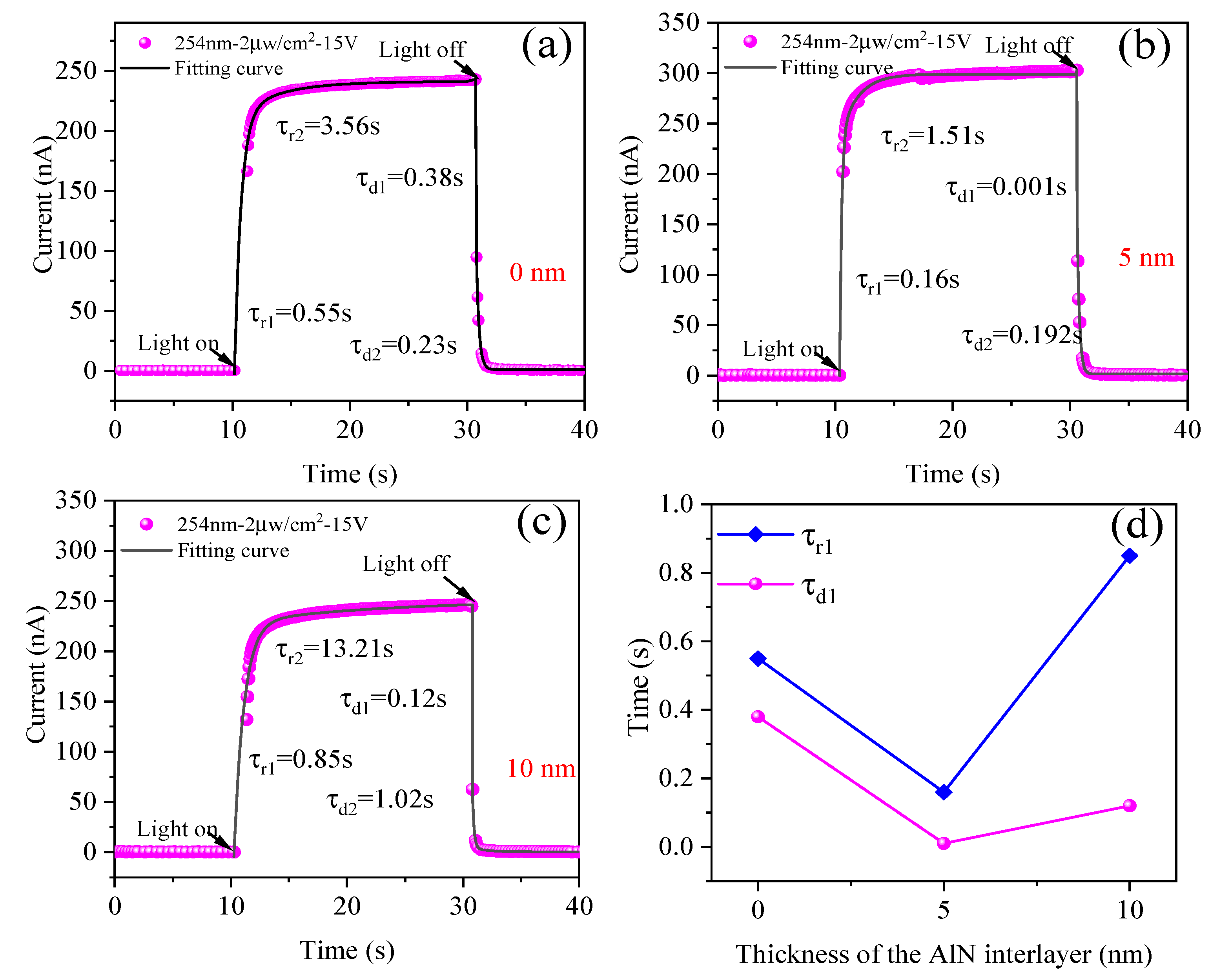

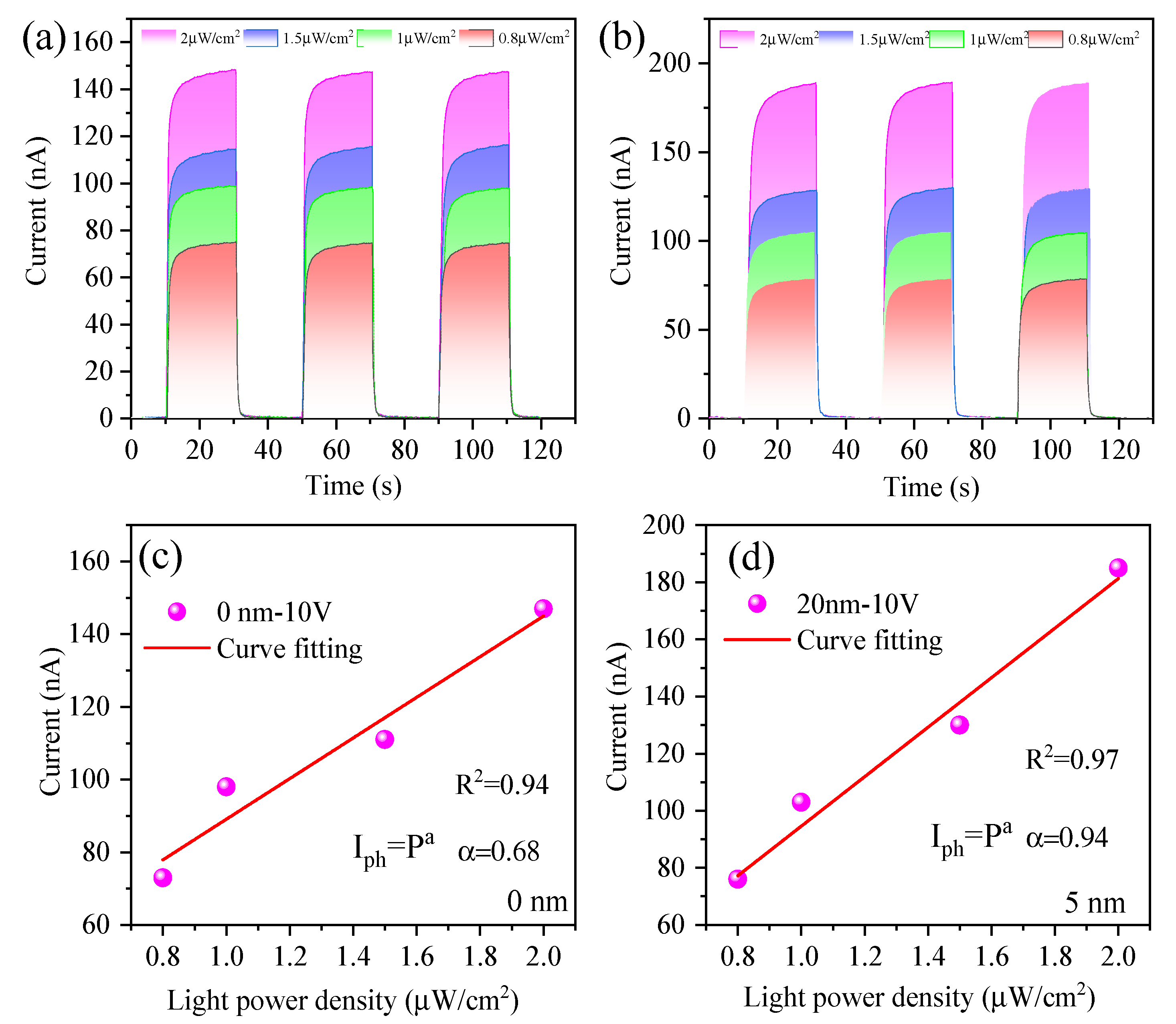

3.3. Transient Response Characteristics and Photoconductive Gain

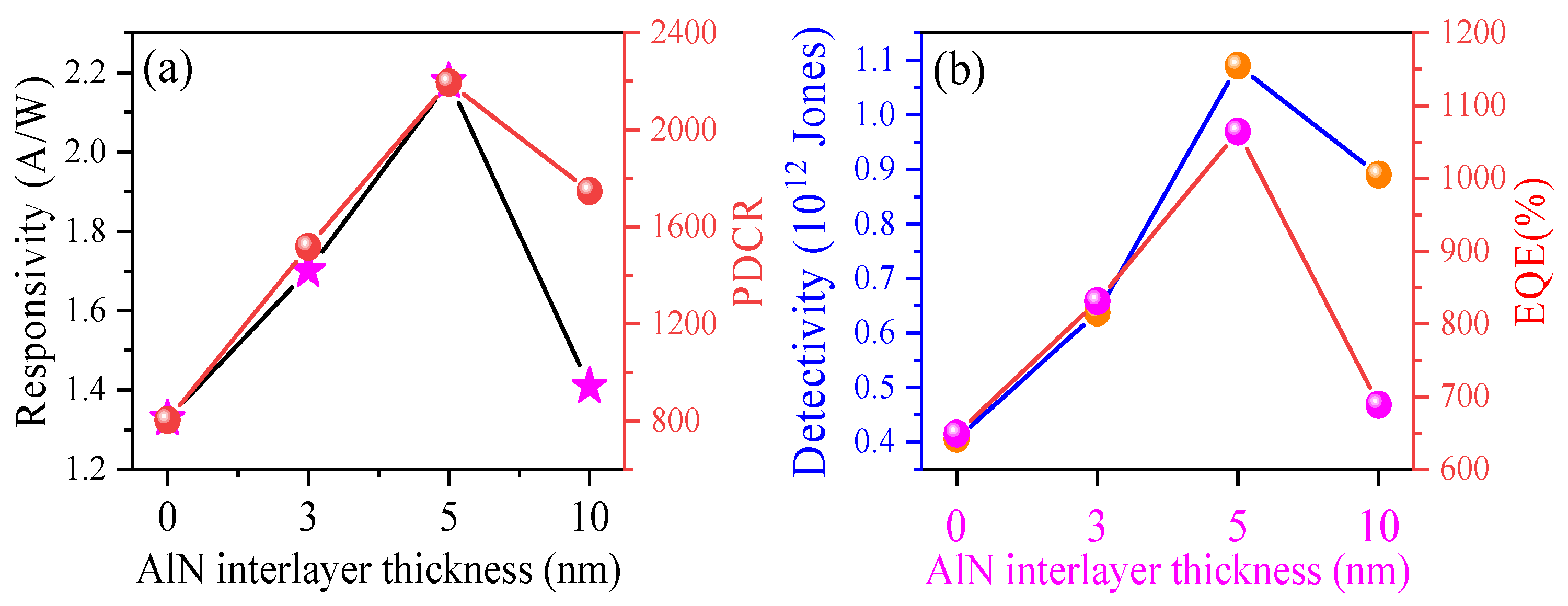

3.4. Key Response Parameters of Optoelectronic Devices

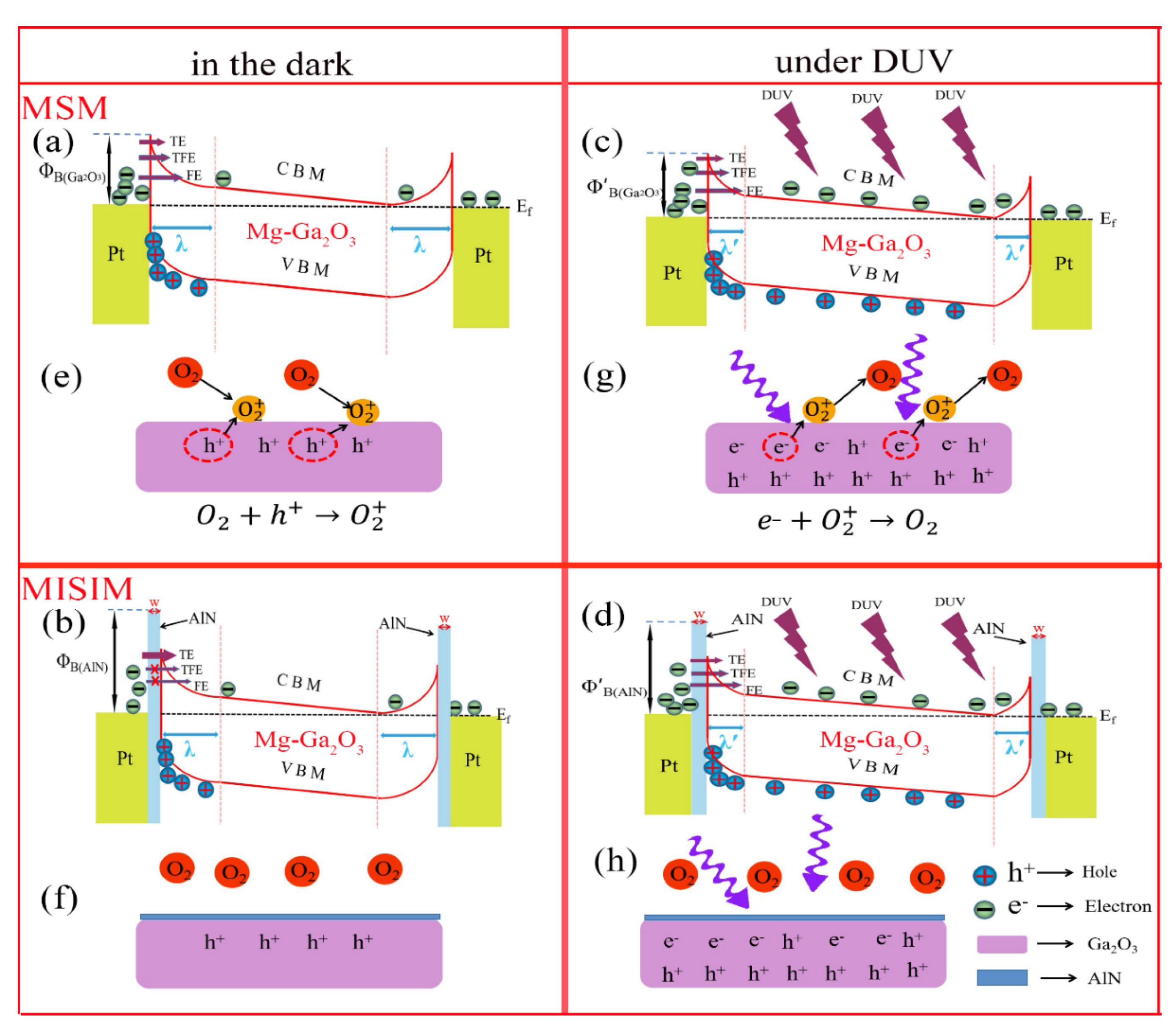

3.5. Mechanism Analysis of Photoelectric Detection Enhancement

4. Conclusions

- Mg-doped β-Ga2O3 films with AlN layers exhibit strong UV absorption in the 200–300 nm solar-blind region. A thinner AlN layer has little effect on the bandgap, whereas increasing the thickness to 10 nm causes a noticeable increase. The light transmittance for samples S0, S1, and S2 appears to be fairly high and increases with thickness, while for sample S3 the transmittance shows a decrease due to excessive thickness.

- The dark current of MISIM photodetectors is relatively less affected by bias voltage. At 10 V voltage, with the increase in AlN thickness, the photocurrent first increases and then decreases, and the dark current gradually decreases. The thickness of the AlN passivation layer also has a significant impact on the response characteristics of the detector, and the response characteristics of the device are best when the AlN passivation layer is 5 nm. The AlN passivation layer enhances the photoconductive gain of the detector, which is attributed to its modulation of interface state density, carrier transport, and the internal electric field.

- The photocurrent increases with light intensity, and the presence of the AlN layer strengthens this linear relationship while reducing surface defect states, thereby improving photocarrier dynamics. The AlN layer inhibits the adsorption and desorption processes between the photogenerated electron–hole pair and O2, thereby retaining more photogenerated non-equilibrium carriers, which is also helpful in enhancing the photoelectric detection performance.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MISIM | Metal–insulator–semiconductor–insulator–metal |

| MSM | Metal–semiconductor–metal |

| DUV | Deep ultraviolet |

| PDs | Solar-blind photodetectors |

| UV-Vis | Ultraviolet-visible absorption spectroscopy |

| SBPDs | Schottky barrier photodetectors |

| TE | Thermal electron |

| FE | Field emission |

| TFE | Thermionic field emission |

| PDCR | Light-to-dark current ratio |

| R | Responsivity |

| D* | Detectivity |

| EQE | External quantum efficiency |

References

- Razeghi, M. Short-wavelength solar-blind detectors-status, prospects, and markets. Proc. IEEE 2002, 90, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zou, Y.; Ding, M.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, X.; Tan, P.; Yu, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, X.; et al. Review of polymorphous Ga2O3 materials and their solar-blind photodetector applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 043001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, H.; Ye, L.; Xiong, Y.; Yu, P.; Li, W.; Yang, X.; Li, H.; Kong, C. Ultrasensitive fully transparent amorphous Ga2O3 solar-blind deep-ultraviolet photodetector for corona discharge detection. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 305104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhao, X.; Hou, X.; Yu, S.; Chen, R.; Zhou, X.; Tan, P.; Liu, Q.; Mu, W.; Jia, Z.; et al. High-Performance β-Ga2O3 Solar-Blind Photodetector With Extremely Low Working Voltage. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2021, 42, 1492–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Wu, C.; Wang, S.; Wu, F.; Tan, C.K.; Guo, D. Enhancing plasticity in optoelectronic artificial synapses: A pathway to efficient neuromorphic computing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 124, 021101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Hu, W.; Hou, L.; Jiang, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J. Performance enhancement of solar-blind UV photodetector by doping silicon in β-Ga2O3 thin films prepared using radio frequency magnetron sputtering. Vacuum 2024, 227, 113399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Ji, X.; Qi, X.; Li, S.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, P.; Wu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Tang, W. Low MOCVD growth temperature controlled phase transition of Ga2O3 films for ultraviolet sensing. Vacuum 2022, 203, 111270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.-R.; Zhang, H.; Mo, H.-L.; Liu, H.-W.; Xiong, Y.-Q.; Li, H.-L.; Kong, C.-Y.; Ye, L.-J.; Li, W.-J. Effect of N-doping on performance of β-Ga2O3 thin film solar-blind ultraviolet detector. Acta Phys. Sin. 2021, 70, 178503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, D.; Ren, F.; Zhou, J.; Bai, S.; Lu, H.; Gu, S.; Zhang, R.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Carrier Transport and Gain Mechanisms in β–Ga2O3-Based Metal–Semiconductor–Metal Solar-Blind Schottky Photodetectors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2019, 66, 2276–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Qi, N.; Lv, M.; Zhang, M. Enhancing solar-blind ultraviolet photodetection performance of room-temperature sputtered amorphous Ga2O3 thin films by doping zinc. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 72, 107402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, M.; Ma, X.; Lv, M.; Zhou, X. Investigation of electronic structure, photoelectric and thermodynamic properties of Mg-doped β-Ga2O3 using first-principles calculation. Vacuum 2025, 235, 114145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ma, X.; Zhang, S.; Hou, L.; Kim, K.H. One-step fabrication of wear resistant and friction-reducing Al2O3/MoS2 nanocomposite coatings on 2A50 aluminum alloy by plasma electrolytic oxidation with MoS2 nanoparticle additive. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 497, 131796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Shang, L.; Jiang, K.; Li, Y.; Zhu, L.; Hu, Z.; Chu, J. High Quality P-Type Mg-Doped β-Ga2O3–δ Films for Solar-Blind Photodetectors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 2022, 43, 580–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi-Darkhaneh, H.; Shekarnoush, M.; Arellano-Jimenez, J.; Rodriguez, R.; Colombo, L.; Quevedo-Lopez, M.; Banerjee, S.K. High-quality Mg-doped p-type Ga2O3 crystalline thin film by pulsed laser. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2022, 33, 24244–24259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.P.; Guo, D.Y.; Chu, X.L.; Shi, H.Z.; Zhu, W.K.; Wang, K.; Huang, X.K.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.L.; Li, P.G.; et al. Mg-doped p-type β-Ga2O3 thin film for solar-blind ultraviolet photodetector. Mater. Lett. 2017, 209, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchikova, Y.; Nazarovets, S.; Popov, A.I. Ga2O3 solar-blind photodetectors: From civilian applications to missile detection and research agenda. Opt. Mater. 2024, 157, 116397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchechko, A.; Vasyltsiv, V.; Kostyk, L.; Tsvetkova, O.; Popov, A.I. Shallow and deep trap levels in X-ray irradiated β-Ga2O3: Mg. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2019, 441, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Sun, W.C.; Wei, S.Y.; Yu, S.M. Investigation of TiO2-Based MISIM Ultraviolet Photodetectors With Different Insulator Layer Thickness by Ultrasonic Spray Pyrolysis Deposition. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2016, 63, 2424–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhi, Y.; Wang, X.; Wu, Z.; Li, P.; Tang, W. Construction of a β-Ga2O3-based metal–oxide–semiconductor-structured photodiode for high-performance dual-mode solar-blind detector applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 5071–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Song, X.; Yang, S.; Chen, B.; Lei, S.; Zhang, X.; Qian, L.-X. Comprehensively Enhanced Performance of MISIM β-Ga2O3 Solar-Blind Photodetector Inserted With an Ultrathin Al2O3 Passivation Layer. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2024, 71, 3746–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tian, C.; Wei, S.; Cai, Z.; Long, H.; Zhang, J.; Hong, R.; Yang, W. High-Performance β-Ga2O3 MISIM Solar-Blind Photodetectors With an Interfacial AlN Layer. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2024, 36, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.-M.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.-Y.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Y.-T.; Xia, H.-C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Wu, Z.-P. Ga2O3-based metal-insulator-semiconductor solar-blind ultraviolet photodetector with HfO2 inserting layer. Acta Phys. Sin. 2023, 72, 097302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-H.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J.; Xing, S.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.-Z.; Li, S.-Y.; Wang, C.-J. Effect of film thickness on photoelectric properties of β-Ga2O3 films prepared by radio frequency magnetron sputtering. Acta Phys. Sin. 2022, 71, 048501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, G.; Dong, C.; Wen, L. Amorphous TiO2 films with high refractive index deposited by pulsed bias arc ion plating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 7252–7258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Peng, Y.; Wang, J.; Saleem, M.F.; Wang, W.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W. Temperature Dependence of Stress and Optical Properties in AlN Films Grown by MOCVD. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-N.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, P.; Hu, W.-B. Investigation of electronic structure and optoelectronic properties of Si-doped β-Ga2O3 using GGA+U method based on first-principle. Acta Phys. Sin. 2024, 73, 017102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Ma, X.; Zhang, M. Enhancing solar-blind UV photodetection of Ga2O3-based photodetectors by using AlN passivation layer. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2025, 715, 417651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabzehmeidani, M.M.; Gafari, S.; Jamali, S.; Kazemzad, M. Concepts, fabrication and applications of MOF thin films in optoelectronics: A review. Appl. Mater. Today 2024, 38, 102153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, H.K.; Ganesh, V.A.; Nair, A.S.; Ramakrishna, S. Anti-reflective coatings: A critical, in-depth review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3779–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Song, W.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Zhu, W.; Wang, L. Self-powered asymmetric metal–semiconductor–metal AlN deep ultraviolet detector. Opt. Lett. 2022, 47, 637–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrano, J.C.; Li, T.; Grudowski, P.A.; Eiting, C.J.; Dupuis, R.D.; Campbell, J.C. Comprehensive characterization of metal–semiconductor–metal ultraviolet photodetectors fabricated on single-crystal GaN. J. Appl. Phys. 1998, 83, 6148–6160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhi, Y.-S.; Du, L.; Fang, J.-P.; Li, S.; Yu, J.-G.; Zhang, M.-L.; Yang, L.-L.; Zhang, S.-H.; et al. Gallium oxide thin film-based deep ultraviolet photodetector array with large photoconductive gain. Acta Phys. Sin. 2022, 71, 208501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.Y.; Zhao, X.L.; Zhi, Y.S.; Cui, W.; Huang, Y.Q.; An, Y.H.; Li, P.G.; Wu, Z.P.; Tang, W.H. Epitaxial growth and solar-blind photoelectric properties of corundum-structured α-Ga2O3 thin films. Mater. Lett. 2016, 164, 364–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.-T.; Cong, L.-J.; Ma, J.-G.; Chen, M.-Z.; Song, D.-Y.; Wang, H.-B.; Li, P.; Li, B.-S.; Xu, H.-Y.; Liu, Y.-C. High-performance high-temperature solar-blind photodetector based on polycrystalline Ga2O3 film. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 847, 156536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Armin, A.; Meredith, P.; Huang, J. Accurate characterization of next-generation thin-film photodetectors. Nat. Photonics 2019, 13, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yang, D.; Ma, D.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Z.Y. Preparation of AZO:PDIN hybrid interlayer materials and application in high-gain polymer photodetectors with spectral response from 300 nm to 1700 nm. Org. Electron. 2019, 68, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamat, P.V. Quantum Dot Solar Cells. The Next Big Thing in Photovoltaics. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 908–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibu, E.S.; Hamada, M.; Nakanishi, S.; Wakida, S.-I.; Biju, V. Photoluminescence of CdSe and CdSe/ZnS quantum dots: Modifications for making the invisible visible at ensemble and single-molecule levels. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2014, 263–264, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Guo, D.; Li, P.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhi, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Z.; et al. Ultrasensitive, Superhigh Signal-to-Noise Ratio, Self-Powered Solar-Blind Photodetector Based on n-Ga2O3/p-CuSCN Core–Shell Microwire Heterojunction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 35105–35114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, W.; Carrascoso-Plana, F.; Jie, W.; Wang, T.; Castellanos-Gomez, A.; Frisenda, R. The role of traps in the photocurrent generation mechanism in thin InSe photodetectors. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Jiang, W.; Feng, M.; He, Y. High-responsivity, self-driven photodetectors based on monolayer WS2/GaAs heterojunction. Photon. Res. 2020, 8, 1368–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Zheng, W.; Hu, P.; Cao, W.; Yang, B. Synthesis of two-dimensional β-Ga2O3 nanosheets for high-performance solar blind photodetectors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 3254–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, J.; Alamo, J.A.D.; Chowdhury, U.; Chou, T.M.; Tserng, H.Q.; Jimenez, J.L. Measurement of Channel Temperature in GaN High-Electron Mobility Transistors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2009, 56, 2895–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Ge, R.; Wen, J.; Du, T.; Zhai, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, L.; Qin, Y. Highly sensitive strain sensors based on piezotronic tunneling junction. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tak, B.R.; Garg, M.; Dewan, S.; Torres-Castanedo, C.G.; Li, K.-H.; Gupta, V.; Li, X.; Singh, R. High-temperature photocurrent mechanism of β-Ga2O3 based metal-semiconductor-metal solar-blind photodetectors. J. Appl. Phys. 2019, 125, 144501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.-Y.; Wu, G.-A.; Wang, K.-Y.; Zhang, T.-F.; Zou, Y.-F.; Wang, D.-D.; Luo, L.-B. Graphene-β-Ga2O3 Heterojunction for Highly Sensitive Deep UV Photodetector Application. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 10725–10731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, J.-Y.; Ji, X.-Q.; Li, S.; Qi, X.-H.; Li, P.-G.; Wu, Z.-P.; Tang, W.-H. Dramatic reduction in dark current of β-Ga2O3 ultraviolet photodectors via β-(Al0.25Ga0.75)2O3 surface passivation. Chin. Phys. B 2023, 32, 016701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Ren, F.; Oh, S.; Jung, Y.; Kim, J.; Mastro, M.A.; Hite, J.K.; Eddy, C.R., Jr.; Pearton, S.J. Elevated temperature performance of Si-implanted solar-blind β-Ga2O3 photodetectors. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 2016, 34, 041207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Feng, Q.-J.; Yi, Z.-Q.; Yu, C.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.-M.; Sui, X.; Liang, H.-W. Preparation and ultraviolet detection performance of Cu doped β-Ga2O3 thin films. Acta Phys. Sin. 2023, 72, 198503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Du, Z.; Ma, M.; Zheng, W.; Liu, S.; Huang, F. Enhanced performance of solar-blind ultraviolet photodetector based on Mg-doped amorphous gallium oxide film. Vacuum 2019, 159, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Type | R(A/W) | EQE | D* (Jones) | PDCR | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Ga2O3 | MSM | 0.74 | 3.603% | 0.34 × 1011 | 103 | [45] |

| β-Ga2O3 | MSM | 1.48 | 727% | — | 340 | [46] |

| β-Ga2O3 | MISIM | 4.12 | 4000% | — | — | [47] |

| Al2O3-β-Ga2O3 | MISIM | 83.3 | — | 1.35 × 1015 | — | [20] |

| HfO2-β-Ga2O3 | MIS | 1.2 | 600% | 2.39 × 1012 | 1.2 × 103 | [22] |

| Si-β-Ga2O3 | MSM | 5 | 2500% | — | 9 | [48] |

| Cu-β-Ga2O3 | MSM | 1.73 | 841% | 5.56 × 1012 | 372 | [49] |

| Mg-β-Ga2O3 | MSM | 0.14 | — | — | 338 | [50] |

| Mg-β-Ga2O3 | MSM | 1.3 | 750% | 0.4 × 1012 | 800 | This work |

| Mg-β-Ga2O3 | MISIM | 2.17 | 1100% | 1.09 × 1012 | 2200 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, J.; Yi, L.; Lv, M.; Zhang, M.; Bai, S. AlN Passivation-Enhanced Mg-Doped β-Ga2O3 MISIM Photodetectors for Highly Responsive Solar-Blind UV Detection. Coatings 2025, 15, 1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15111312

Tan J, Yi L, Lv M, Zhang M, Bai S. AlN Passivation-Enhanced Mg-Doped β-Ga2O3 MISIM Photodetectors for Highly Responsive Solar-Blind UV Detection. Coatings. 2025; 15(11):1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15111312

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Jiaxin, Lin Yi, Mingyue Lv, Min Zhang, and Suyuan Bai. 2025. "AlN Passivation-Enhanced Mg-Doped β-Ga2O3 MISIM Photodetectors for Highly Responsive Solar-Blind UV Detection" Coatings 15, no. 11: 1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15111312

APA StyleTan, J., Yi, L., Lv, M., Zhang, M., & Bai, S. (2025). AlN Passivation-Enhanced Mg-Doped β-Ga2O3 MISIM Photodetectors for Highly Responsive Solar-Blind UV Detection. Coatings, 15(11), 1312. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15111312