Research Progress of Passively Mode-Locked Fiber Lasers Based on Saturable Absorbers

Abstract

1. Introduction

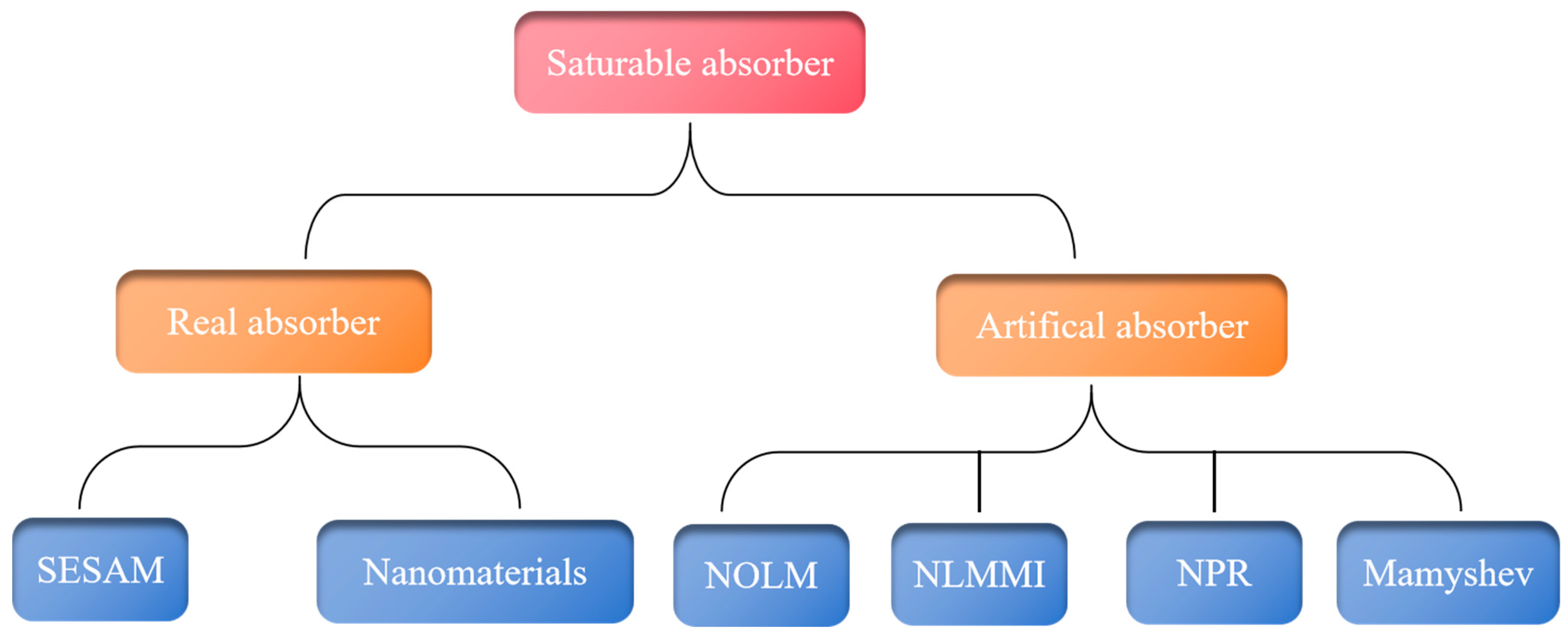

2. Characteristics of SAs

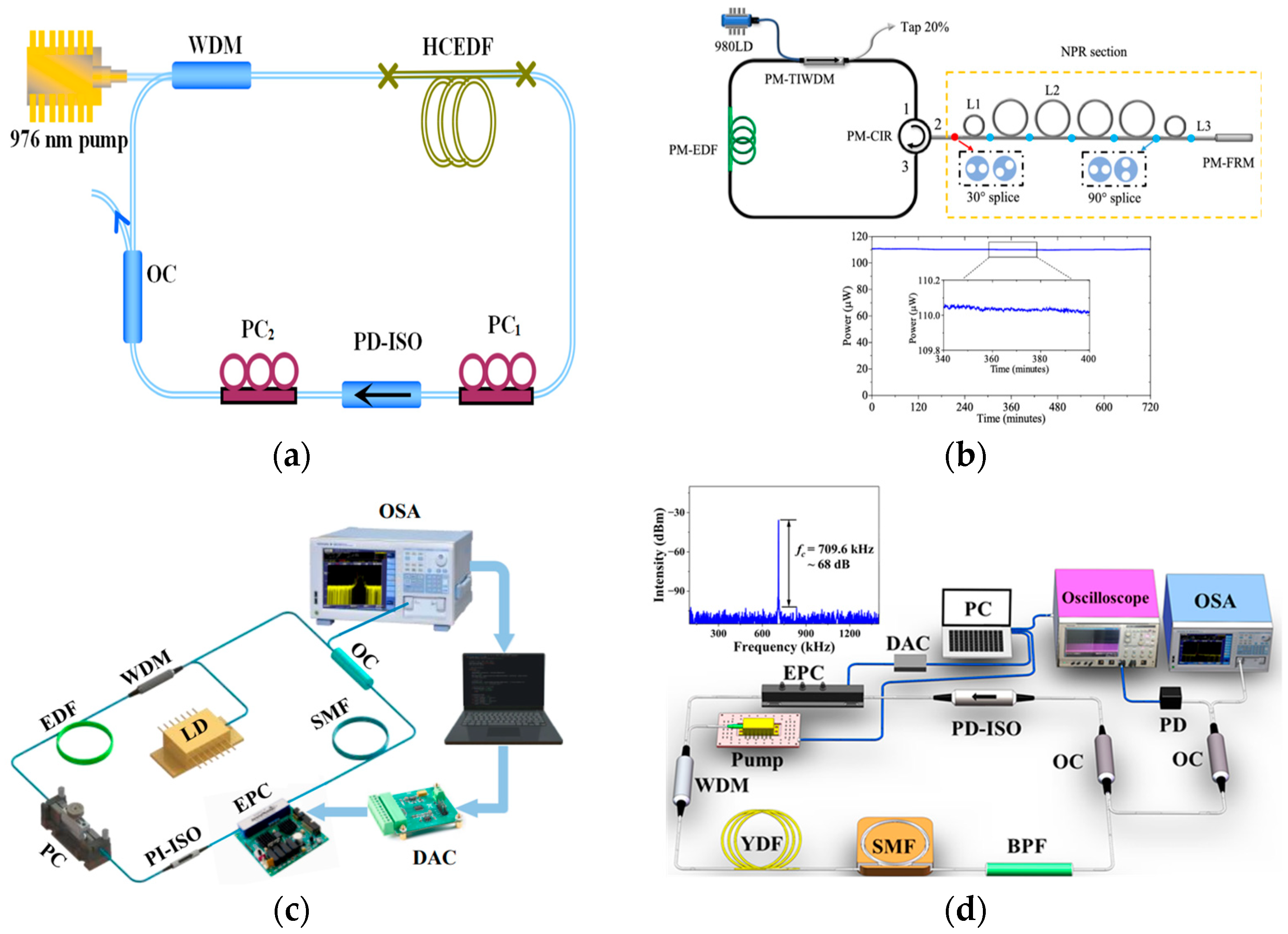

3. Real SA

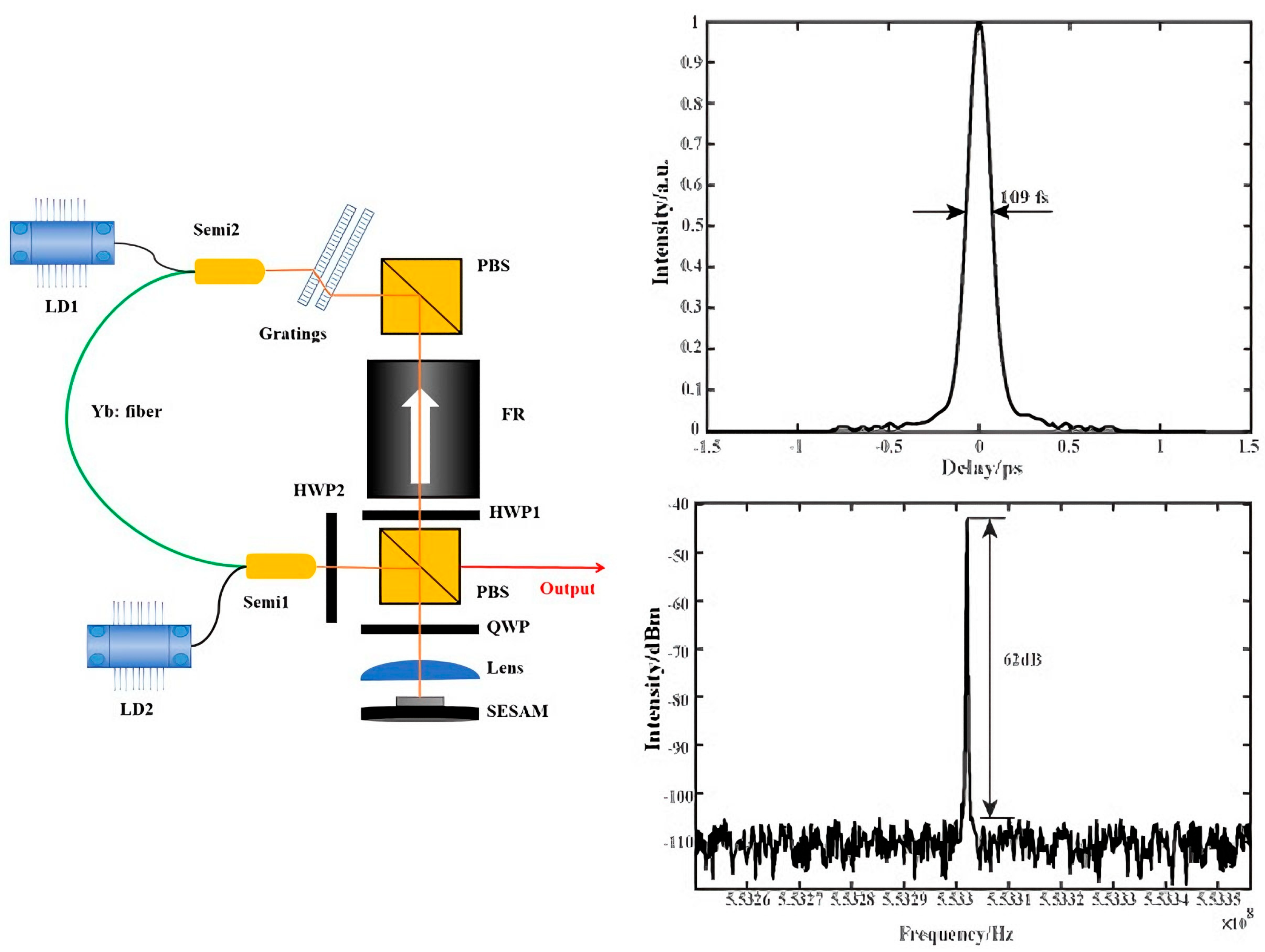

3.1. Semiconductor Saturable Absorber Mirror

3.2. Nanomaterials

3.2.1. Carbon Nanotubes

3.2.2. Graphene

3.2.3. Black Phosphorus

3.2.4. Topological Insulators

3.2.5. Transition Metal Dichalcogenides

4. Artificial SA

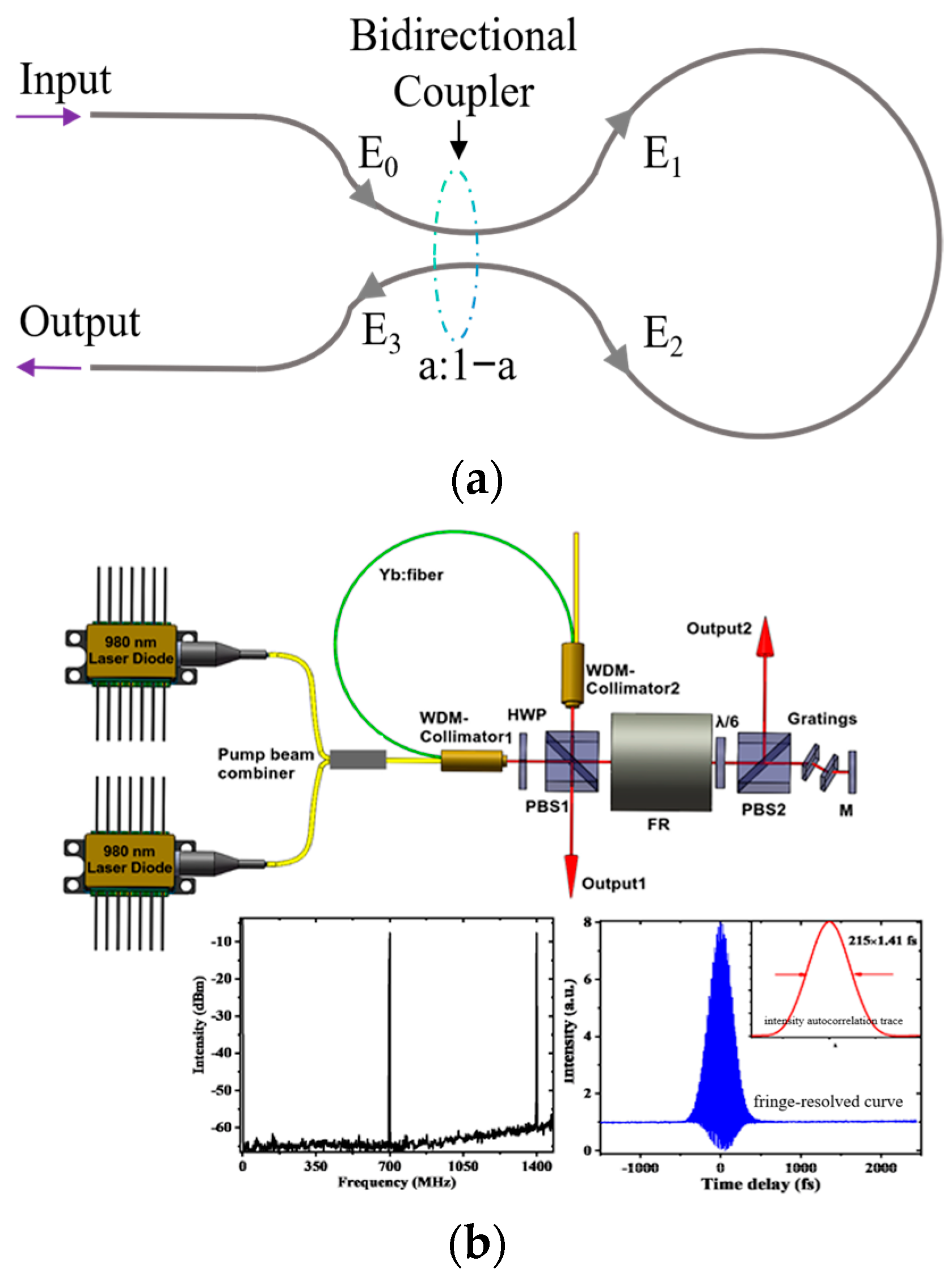

4.1. Nonlinear Optical Loop Mirror

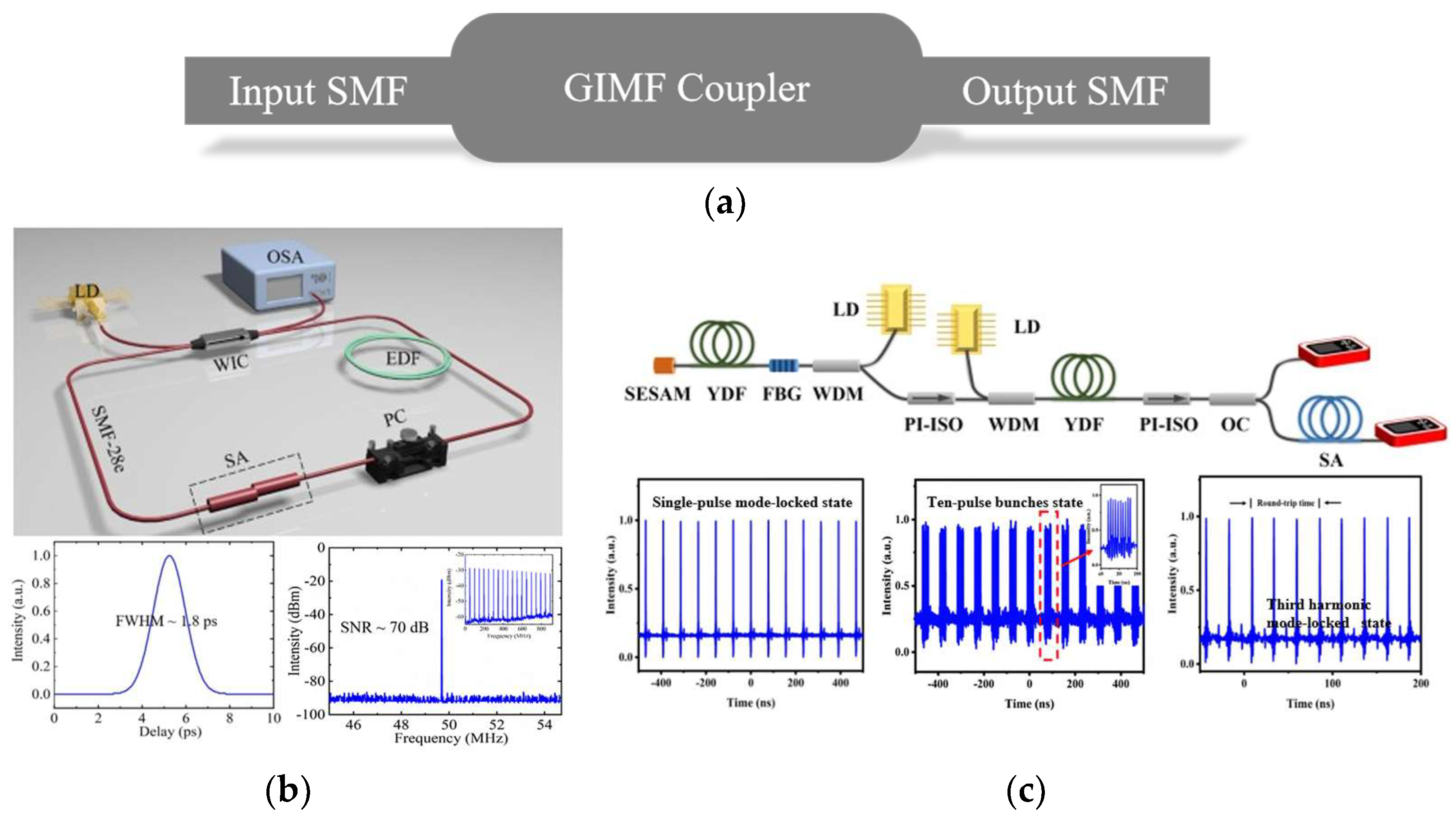

4.2. Nonlinear Multimode Interference

4.3. Nonlinear Polarization Rotation

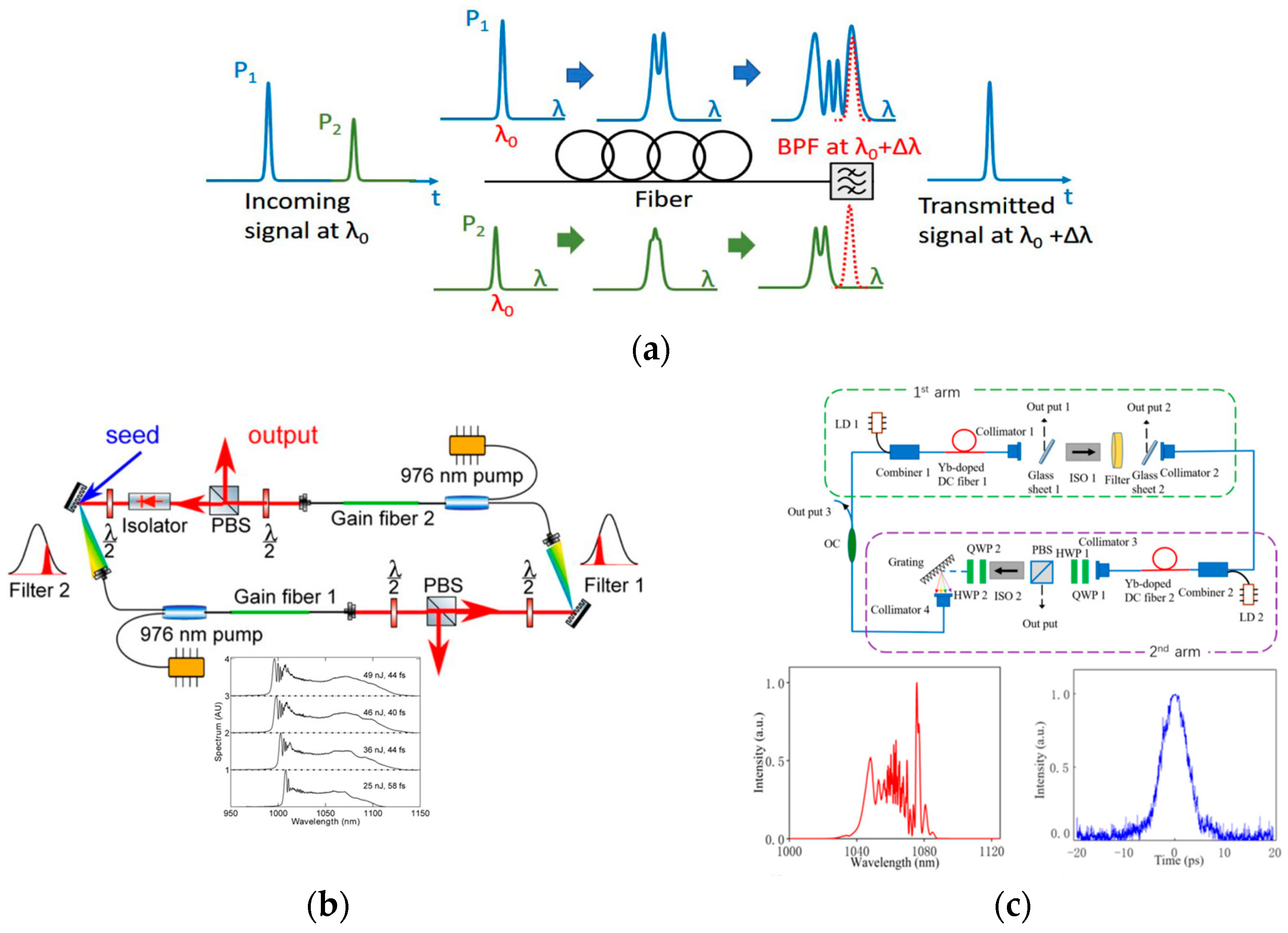

4.4. Mamyshev Oscillator

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zamfirescu, M.; Ulmeanu, M.; Jipa, F.; Anghel, I.; Simion, S.; Dabu, R.; Ionita, I. Laser processing and characterization with femtosecond laser pulses. Rom. Rep. Phys. 2010, 62, 594–609. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Xiong, Q.; Lin, J.; Wong, A.K.; Wang, M.; Kwok, W. Ultrafast excited state dynamics of isocytosine unveiled by femtosecond broadband time-resolved spectroscopy combined with density functional theoretical study. Photochem. Photobiol. 2023, 100, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.; Wang, R.; Cao, H.; Wen, X.; Dai, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. Coded information storage pulsed laser based on vector period-doubled pulsating solitons. Opt. Laser Technol. 2022, 158, 108894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraïso, T.K.; Woodward, R.I.; Marangon, D.G.; Lovic, V.; Yuan, Z.; Shields, A.J. Advanced Laser Technology for Quantum Communications (Tutorial Review). Adv. Quantum Technol. 2021, 4, 2100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpert, J.; Hädrich, S.; Rothhardt, J.; Krebs, M.; Eidam, T.; Schreiber, T.; Tünnermann, A. Ultrafast fiber lasers for strong-field physics experiments. Laser Photon. Rev. 2011, 5, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, R.; Loiko, P.; Mateos, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, M.H.; Rotermund, F.; Yasukevich, A.; et al. Passive Q-switching of microchip lasers based on Ho:YAG ceramics. Appl. Opt. 2016, 55, 4877–4887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Guo, B. Active mode locking with a hybrid neodymium laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 70, 3501–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kues, M.; Reimer, C.; Wetzel, B.; Roztocki, P.; Little, B.E.; Chu, S.T.; Hansson, T.; Viktorov, E.A.; Moss, D.J.; Morandotti, R. Passively mode-locked laser with an ultra-narrow spectral width. Nat. Photon. 2017, 11, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churin, D.; Olson, J.; Norwood, R.A.; Peyghambarian, N.; Kieu, K. High-power synchronously pumped femtosecond Raman fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 2529–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiman, T.H. Stimulated Optical Radiation in Ruby. Nature 1960, 187, 493–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, U.; Weingarten, K.; Kartner, F.; Kopf, D.; Braun, B.; Jung, I.; Fluck, R.; Honninger, C.; Matuschek, N.; der Au, J.A. Semiconductor saturable absorber mirrors (SESAM’s) for femtosecond to nanosecond pulse generation in solid-state lasers. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 1996, 2, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Hou, L.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Lin, Q.; Bai, Y.; Bai, J. Tunable Ytterbium-Doped Mode-Locked Fiber Laser Based on Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. J. Light. Technol. 2019, 37, 2370–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, L.-Y.; Li, Z.-Y.; Lin, J.-H.; Song, Y.-F.; Zhang, H. Wavelength tunable passive-mode locked Er-doped fiber laser based on graphene oxide nano-platelet. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 140, 106932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, W.; Shi, X.; Wang, J.; Ding, X.; Zhang, K.; Peng, J.; Wu, J.; Zhou, P. Black phosphorus-enabled harmonic mode locking of dark pulses in a Yb-doped fiber laser. Laser Phys. Lett. 2019, 16, 085102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, S.; Ganguly, R.; Mondal, K. Topological Insulators: An In-Depth Review of Their Use in Modelocked Fiber Lasers. Ann. Phys. 2021, 533, 2000564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.; Park, J.; Lee, J.; Jhon, Y.M.; Lee, J.H. Femtosecond harmonic mode-locking of a fiber laser at 327 GHz using a bulk-like, MoSe_2-based saturable absorber. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 10575–10589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, C.; Luo, H.; Cui, L.; Zhang, T.; Jia, Z.; Li, J.; Qin, W.; Qin, G. Silver Nanowires with Ultrabroadband Plasmon Response for Ultrashort Pulse Fiber Lasers. Adv. Photon. Res. 2021, 3, 2100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Samion, M.; Kamely, A.; Ismail, M. Mode-locked thulium doped fiber laser with zinc oxide saturable absorber for 2 μm operation. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2019, 97, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lan, D.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, T. TiN nanoparticles deposited onto a D-shaped fiber as an optical modulator for ultrafast photonics and temperature sensing. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 16608–16614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Ma, C.; Wei, S.; Kuklin, A.V.; Zhang, H.; Ågren, H. Applications of Few-Layer Nb2C MXene: Narrow-Band Photodetectors and Femtosecond Mode-Locked Fiber Lasers. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabec, T.; Krausz, F. Intense few-cycle laser fields: Frontiers of nonlinear optics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2000, 72, 545–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Xia, W. All-fiber passively mode-locked laser using nonlinear multimode interference of step-index multimode fiber. Photon. Res. 2018, 6, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andral, U.; Fodil, R.S.; Amrani, F.; Billard, F.; Hertz, E.; Grelu, P. Fiber laser mode locked through an evolutionary algorithm. Optica 2015, 2, 275–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-C.; Yang, S.; Zhu, Z.-W.; Lau, K.-Y.; Li, L. 72-fs Er-doped Mamyshev Oscillator. J. Light. Technol. 2021, 40, 2123–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermann, M.E.; Hartl, I. Ultrafast fibre lasers. Nat. Photon. 2013, 7, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, M.; Karirinne, S.; Guina, M.; Grudinin, A.; Okhotnikov, O. Femtosecond Neodymium-Doped Fiber Laser Operating in the 894–909-nm Spectral Range. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2004, 16, 1029–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivistö, S.; Puustinen, J.; Guina, M.; Okhotnikov, O.; Dianov, E. Tunable modelocked bismuth-doped soliton fibre laser. Electron. Lett. 2008, 44, 1456–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Sucha, G.; Fermann, M.E.; Jimenez, J.; Harter, D.; Dagenais, M.; Fox, S.; Hu, Y. Nonlinearly limited saturable-absorber mode locking of an erbium fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 1999, 24, 1074–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumenyuk, R.; Vartiainen, I.; Tuovinen, H.; Okhotnikov, O.G. Dissipative dispersion-managed soliton 2 μm thulium/holmium fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 2011, 36, 609–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ober, M.H.; Keiler, U.; Chiu, T.H.; Hofer, M. Self-starting diode-pumped femtosecond Nd fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 1993, 18, 1532–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Gu, X.; Feng, Y. SESAM Mode-Locked, Environmentally Stable, and Compact Dissipative Soliton Fiber Laser. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2014, 26, 1314–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okhotnikov, O.G.; Grudinin, A.B. Ultrafast fiber systems based on SESAM technology: New horizons and application. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Optics, Rochester, NY, USA, 12–15 October 2004; p. FWS4. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, Z.; Ming-Lie, H.; You-Jian, S.; Xin, Z.; Lu, C.; Qing-Yue, W. An Yb-doped large-mode-area photonic crystal fiber mode-locking laser with free output coupler. Acta Phys. Sin. 2009, 58, 7727–7734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Ou, S.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Q.; Sui, Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, N.; Liu, H.; Shum, P.P. 109 fs, 553 MHz pulses from a polarization-maintaining Yb-doped ring fiber laser with SESAM mode-locking. Opt. Commun. 2022, 522, 128520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Tang, M.; Shum, P.P.; Gong, Y.; Lin, C.; Fu, S.; Zhang, T. High-energy laser pulse with a submegahertz repetition rate from a passively mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 1432–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, P. High Repetition-Rate Narrow Bandwidth SESAM Mode-Locked Yb-Doped Fiber Lasers. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2011, 24, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmat, M.J.; Gholami, A.; Omoomi, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Bagheri, A.; Normohammadi, H.; Kanani, M.; Ebrahimi, A. Ultra-short pulse generation in a linear femtosecond fiber laser using a Faraday rotator mirror and semiconductor saturable absorber mirror. Laser Phys. Lett. 2018, 15, 025101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, S.; Yu, Z.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, N.; Liu, H.; Shum, P.P. GHz-repetition-rate fundamentally mode-locked, isolator-free ring cavity Yb-doped fiber lasers with SESAM mode-locking. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 43543–43550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Luo, H.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Soliton Mode-Locked Fluoride Fiber Laser at ∼3.5 μm Using an InAs/GaSb Superlattice SESAM. J. Light. Technol. 2025, 43, 6904–6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armas-Rivera, I.; Rodríguez-Morales, L.; Durán-Sánchez, M.; Ibarra-Escamilla, B. Easy wavelength-tunable passive mode-locked fiber laser through a Lyot filter with a SESAM. Optik 2024, 311, 171904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Cong, Z.; Gao, G.; Zhang, A.; Guo, H.; Yao, G.; Liu, Z. Stable 5-GHz fundamental repetition rate passively SESAM mode-locked Er-doped silica fiber lasers. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 9021–9029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, P.; Duval, S.; Fortin, V.; Vallee, R.; Bernier, M. Towards Ultrafast All-Fiber Laser at 2.8 μm Based on a SESAM and a Fiber Bragg Grating. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics Europe & European Quantum Electronics Conference (CLEO/Europe-EQEC), Munich, Germany, 23–27 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, T.; Lin, J.; Gu, C.; Yao, P.; Xu, L. Switchable and tunable dual-wavelength passively mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2022, 68, 102750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.C.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M. Drawing conclusions from graphene. Phys. World 2006, 19, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H. Carbon nanotubes: Opportunities and challenges. Surf. Sci. 2002, 500, 218–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.-Z.; Stenger, J.; Zimmermann, J.; Bachilo, S.M.; Smalley, R.E.; Weisman, R.B.; Fleming, G.R. Ultrafast carrier dynamics in single-walled carbon nanotubes probed by femtosecond spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 3368–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prechtel, L.; Song, L.; Manus, S.; Schuh, D.; Wegscheider, W.; Holleitner, A.W. Time-Resolved Picosecond Photocurrents in Contacted Carbon Nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2010, 11, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Wang, K.; Szydłowska, B.M.; Baker-Murray, A.A.; Wang, J.J.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Blau, W.J. Ultrafast Nonlinear Optical Properties of a Graphene Saturable Mirror in the 2 μm Wavelength Region. Laser Photon. Rev. 2017, 11, 201700166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miró, P.; Audiffred, M.; Heine, T. An atlas of two-dimensional materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 6537–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, X.; Wang, H.; Huang, S.; Xia, F.; Dresselhaus, M.S. The renaissance of black phosphorus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 4523–4530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.; Soklaski, R.; Liang, Y.; Yang, L. Layer-controlled band gap and anisotropic excitons in few-layer black phosphorus. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 89, 235319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, V.; Fei, R.; Yang, L. Quasiparticle energies, excitons, and optical spectra of few-layer black phosphorus. 2D Mater. 2015, 2, 044014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Hao, Q.; Wang, H.; Yu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, B.; Li, L. 2D Materials-Based Pulsed Solid-State Laser: Status and Prospect. Laser Photon. Rev. 2024, 18, 202300588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski, K.J.; Wessells, C.D.; Reed, B.W.; Cha, J.J.; Kong, D.; Cui, Y. Chemical Intercalation of Zerovalent Metals into 2D Layered Bi2Se3 Nanoribbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13773–13779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, Z.; Zang, Y.; Gong, Y.; Zheng, X.; He, K.; Cheng, X.; Jiang, T. Thickness-dependent carrier and phonon dynamics of topological insulator Bi_2Te_3 thin films. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 14635–14643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.H.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Kis, A.; Coleman, J.N.; Strano, M.S. Electronics and optoelectronics of two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2012, 7, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Liang, T.; Shi, M.; Chen, H. Graphene-Like Two-Dimensional Materials. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3766–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, S.-C.; Leburton, J.-P. Electronic structures of defects and magnetic impurities in MoS2 monolayers. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2014, 9, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iijima, S. Helical microtubules of graphitic carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Set, S.; Yaguchi, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Jablonski, M. Laser Mode Locking Using a Saturable Absorber Incorporating Carbon Nanotubes. J. Light. Technol. 2004, 22, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-W.; Yamashita, S.; Goh, C.S.; Set, S.Y. Carbon nanotube mode lockers with enhanced nonlinearity via evanescent field interaction in D-shaped fibers. Opt. Lett. 2006, 32, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-W.; Morimune, K.; Set, S.Y.; Yamashita, S. Polarization insensitive all-fiber mode-lockers functioned by carbon nanotubes deposited onto tapered fibers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 021101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A.; Zhou, K.; Bennion, I.; Yamashita, S. Passive mode-locked lasing by injecting a carbon nanotube-solution in the core of an optical fiber. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 11008–11014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, J.H.; Choi, S.Y.; Rotermund, F.; Yeom, D.-I. All-fiber Er-doped dissipative soliton laser based on evanescent field interaction with carbon nanotube saturable absorber. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 22141–22146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, H.; De Souza, E. Bandwidth optimization of a Carbon Nanotubes mode-locked Erbium-doped fiber laser. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2012, 18, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, X.; Lv, S.; Duan, D. Passively mode-locked C-band fiber laser employing carbon nanotubes as saturable absorbers. Front. Phys. 2025, 20, 032205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Z.; Yan, Y.; Shen, Z.X.; Loh, K.P.; Tang, D.Y. Atomic-Layer Graphene as a Saturable Absorber for Ultrafast Pulsed Lasers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2009, 19, 3077–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K.Y.; Abidin, N.H.Z.; Abu Bakar, M.H.; A Latif, A.; Muhammad, F.D.; Huang, N.M.; Omar, M.F.; A Mahdi, M. Passively mode-locked ultrashort pulse fiber laser incorporating multi-layered graphene nanoplatelets saturable absorber. J. Phys. Commun. 2018, 2, 075005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, T.; Zhang, B.; Li, M.; Lu, Y.; Chen, K.P. All-fiber passively mode-locked thulium-doped fiber ring laser using optically deposited graphene saturable absorbers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2013, 102, 131117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Tang, D.; Knize, R.J.; Zhao, L.; Bao, Q.; Loh, K.P. Graphene mode locked, wavelength-tunable, dissipative soliton fiber laser. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 111112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Yan, L.; Song, Y.; Jia, X.; Feng, X.; Hou, L.; Bai, J. Switchable single- and dual-wavelength femtosecond mode-locked Er-doped fiber laser based on carboxyl-functionalized graphene oxide saturable absorber. Chin. Opt. Lett. 2021, 19, 111405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.K.; Lau, K.Y.; Lee, H.K.; Yusoff, N.M.; Sarmani, A.R.; Omar, M.F.; Mahdi, M.A. L-band femtosecond fiber laser based on a reduced graphene oxide polymer composite saturable absorber. Opt. Mater. Express 2020, 11, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, T.A.; Adwan, S.; Arof, H.; Harun, S.W. Black Phosphorus Coated D-Shape Fiber as a Mode-Locker for Picosecond Soliton Pulse Generation. Crystals 2023, 13, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Song, Y.; Tian, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, Z.; Fang, X. Mode-locked ytterbium-doped fiber laser based on topological insulator: Bi_2Se_3. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 24055–24061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Huang, J.; Du, L.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Liu, D.; Miao, L.; Zhao, C. Highly stable soliton and bound soliton generation from a fiber laser mode-locked by VSe2 nanosheets. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 6838–6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, G.; Chen, S.; Guo, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Bao, Q.; Wen, S.; Tang, D.; et al. Mechanically exfoliated black phosphorus as a new saturable absorber for both Q-switching and Mode-locking laser operation. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 12823–12833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotor, J.; Sobon, G.; Kowalczyk, M.; Macherzynski, W.; Paletko, P.; Abramski, K.M. Ultrafast thulium-doped fiber laser mode locked with black phosphorus. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 3885–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, B.; Wu, K.; Wang, K.; Hanlon, D.; Coleman, J.N.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L.; et al. Size-dependent saturable absorption and mode-locking of dispersed black phosphorus nanosheets. Opt. Mater. Express 2016, 6, 3159–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Xie, G.; Zhao, C.; Wen, S.; Yuan, P.; Qian, L. Mid-infrared mode-locked pulse generation with multilayer black phosphorus as saturable absorber. Opt. Lett. 2015, 41, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Hai, T.; Xie, G.; Ma, J.; Yuan, P.; Qian, L.; Li, L.; Zhao, L.; Shen, D. Black phosphorus Q-switched and mode-locked mid-infrared Er:ZBLAN fiber laser at 35 μm wavelength. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 8224–8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, S.; Ahmed, T.; Balendhran, S.; Bansal, V.; Sriram, S.; Bhaskaran, M.; Walia, S. Black phosphorus: Ambient degradation and strategies for protection. 2D Mater. 2018, 5, 032001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jhon, Y.I.; Lee, J.; Jhon, Y.M.; Lee, J.H. Topological Insulators for Mode-locking of 2-μm Fiber Lasers. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2018, 24, 2811903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Tang, D.; Cheng, T.; Lu, C. Nanosecond square pulse generation in fiber lasers with normal dispersion. Opt. Commun. 2007, 272, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, F.; Zhang, H.; Gorza, S.-P.; Emplit, P. Towards mode-locked fiber laser using topological insulators. In Proceedings of the Nonlinear Photonics, Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 17–21 June 2012; p. NTh1A.5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Qi, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wen, S.; Tang, D. Ultra-short pulse generation by a topological insulator based saturable absorber. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 211106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotor, J.; Sobon, G.; Grodecki, K.; Abramski, K.M. Mode-locked erbium-doped fiber laser based on evanescent field interaction with Sb2Te3 topological insulator. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 251112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, H.; Jin, T.S.; Batumalay, M.; Muhammad, A.R.; Sampe, J.; Markom, A.M.; Zain, H.A.; Harun, S.W.; Hasnan, M.M.I.M.; Saad, I. Single and Bunch Soliton Generation in Optical Fiber Lasers Using Bismuth Selenide Topological Insulator Saturable Absorber. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Yu, G.; Wang, Y.; Huang, P.; Wang, X.; Si, S.; Cheng, C.; Li, D. Nonlinear optical properties of Bi2Se2Te for harmonic mode-locked and broadband Q-switched pulses generation. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 31179–31192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, J.; Fan, J.; Lotya, M.; O’nEill, A.; Fox, D.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, Q.; et al. Ultrafast Saturable Absorption of Two-Dimensional MoS2 Nanosheets. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 9260–9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, S.B.; Zheng, J.; Du, J.; Wen, S.C.; Tang, D.Y.; Loh, K.P. Molybdenum disulfide (MoS_2) as a broadband saturable absorber for ultra-fast photonics. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 7249–7260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Howe, R.C.T.; Woodward, R.I.; Kelleher, E.J.R.; Torrisi, F.; Hu, G.; Popov, S.V.; Taylor, J.R.; Hasan, T. Solution processed MoS2-PVA composite for sub-bandgap mode-locking of a wideband tunable ultrafast Er:fiber laser. Nano Res. 2015, 8, 1522–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Su, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Mao, D.; Si, J. Femtosecond Passively Er-Doped Mode-Locked Fiber Laser With WS2 Solution Saturable Absorber. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2016, 23, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.-L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Lin, J.-T.; Li, X.; Kuan, P.-W.; Zhou, Y.; Liao, M.-S.; Gao, W.-Q. Mode-locked fiber laser with MoSe 2 saturable absorber based on evanescent field. Chin. Phys. B 2019, 28, 014207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Yan, M.; Chai, L.; Song, Y.; Hu, M. (INVITED)A diverse set of soliton molecules generation in a passively mode-locked Er-doped fiber laser with a saturable absorber of WSe2 nanofilm. Results Opt. 2022, 7, 100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.K.; Tang, C.Y.; Ahmed, S.; Qiao, J.; Zeng, L.-H.; Tsang, Y.H. Utilization of group 10 2D TMDs-PdSe 2 as a nonlinear optical material for obtaining switchable laser pulse generation modes. Nanotechnology 2020, 32, 055201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Li, H.; Lan, C.; Li, C.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Graphene/WS2 heterostructure saturable absorbers for ultrashort pulse generation in L-band passively mode-locked fiber lasers. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 11514–11523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Shi, L.; Xu, B.; Weng, R.; Wang, J.; Zhou, C.; Fan, M.; Tang, W.; Xia, W. Generation of Bright-Dark soliton pairs in mode-locked fiber laser based on WSe2/MoSe2 heterojunction. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2023, 136, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, D.; Wang, Y.; Ma, C.; Han, L.; Jiang, B.; Gan, X.; Hua, S.; Zhang, W.; Mei, T.; Zhao, J. WS2 mode-locked ultrafast fiber laser. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, srep07965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishizawa, N.; Jin, L.; Kataura, H.; Sakakibara, Y. Dynamics of a Dispersion-Managed Passively Mode-Locked Er-Doped Fiber Laser Using Single Wall Carbon Nanotubes. Photonics 2015, 2, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, W.; Hu, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Gao, C.; Shen, D.; et al. Yb-doped passively mode-locked fiber laser based on a single wall carbon nanotubes wallpaper absorber. Opt. Laser Technol. 2013, 47, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wu, G.; Wang, Q.; Han, Y.; Gao, B.; Tian, X.; Guo, S.; Liu, L. Dynamics of solitons in NOLM based all-normal dispersion Yb-doped mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Fiber Technol. 2023, 81, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duling, I.N. All-fiber ring soliton laser mode locked with a nonlinear mirror. Opt. Lett. 1991, 16, 539–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jiang, X.; Wang, A.; Chang, G.; Kaertner, F.; Zhang, Z. Robust 700 MHz mode-locked Yb:fiber laser with a biased nonlinear amplifying loop mirror. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 26003–26008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguergaray, C.; Broderick, N.G.R.; Erkintalo, M.; Chen, J.S.Y.; Kruglov, V. Mode-locked femtosecond all-normal all-PM Yb-doped fiber laser using a nonlinear amplifying loop mirror. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 10545–10551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Gu, X. 32-nJ 615-fs Stable Dissipative Soliton Ring Cavity Fiber Laser With Raman Scattering. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2015, 28, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Song, Y.; Liao, R.; Liu, B.; Hu, M.; Chai, L.; Wang, Q. Research on Modified Nonlinear Amplifying Loop Mirror Mode-Locked Lasers. Chin. J. Lasers 2015, 42, 1202002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Dong, C.; Wang, H.; Du, T.; Luo, Z. Towards visible-wavelength passively mode-locked lasers in all-fibre format. Light. Sci. Appl. 2020, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Pang, X.; Luo, Z. All-Fiber Mode-Locked Deep-Red Laser by a Phase-Biased NOLM. J. Light. Technol. 2025, 43, 4981–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallais, L.; Douti, D.-B.; Commandré, M.; Batavičiūtė, G.; Pupka, E.; Ščiuka, M.; Smalakys, L.; Sirutkaitis, V.; Melninkaitis, A. Wavelength dependence of femtosecond laser-induced damage threshold of optical materials. J. Appl. Phys. 2015, 117, 223103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Lin, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gu, C.; Yao, P.; Xu, L. Er-doped mode-locked fiber lasers based on nonlinear polarization rotation and nonlinear multimode interference. Opt. Laser Technol. 2020, 130, 106337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Yu, Q.; Qi, Y.; Jia, S.; Bai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lu, Z. Multipulse bunches in the Yb-doped mode-locked fiber laser based on NLMMI-NPR hybrid mode locked mechanism. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2024, 144, 105646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazemosadat, E.; Mafi, A. Nonlinear multimodal interference and saturable absorption using a short graded-index multimode optical fiber. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2013, 30, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Song, W.; Lee, Y.L.; Lee, J.H.; Shin, W. A passively mode locked thulium doped fiber laser using bismuth telluride deposited multimode interference. Laser Phys. Lett. 2016, 13, 55103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Dong, Z.; Dong, T.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, C.; Yao, P.; Gu, C.; Xu, L. Wavelength switchable all-fiber mode-locked laser based on nonlinear multimode interference. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 141, 107093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.; Li, X.; Zhang, S.; Han, M.; Han, H.; Yang, Z. L-band wavelength-tunable dissipative soliton fiber laser. Opt. Express 2016, 24, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsas, V.; Newson, T.; Richardson, D.; Payne, D. Selfstarting passively mode-locked fibre ring soliton laser exploiting nonlinear polarisation rotation. Electron. Lett. 1992, 28, 1391–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.-Q.; Song, Y.-R.; Dong, Z.-K.; Li, K.-X.; Tian, J.-R. Compact Yb-doped mode-locked fiber laser with only one polarized beam splitter. Appl. Opt. 2017, 56, 1674–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Lu, X.; Jiang, T.; Lu, Y.; Yu, S. Simple and efficient nonlinear polarization evolution mode-locked fiber laser by three-dimensionally manipulating a polarization beam splitter. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 3301–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Pang, M.; Menyuk, C.R.; Russell, P.S.J. Sub-100-fs 187 GHz mode-locked fiber laser using stretched-soliton effects. Optica 2016, 3, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Chow, K.K.; Liu, B.; Dai, M.; Ma, Y.; Shirahata, T.; Yamashita, S.; Set, S.Y. L-band mode-locked fiber laser using all polarization-maintaining nonlinear polarization rotation. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 4729–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X. Intelligent Control of Mode-Locked Fiber Laser via Residual Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics Europe & European Quantum Electronics Conference (CLEO/Europe-EQEC), Munich, Germany, 23–27 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, L.-Y.; Li, T.-J.; Zhu, Q.-B.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Z.-R.; Luo, Z.-C. Intelligent multi-parameter control of a rectangular pulse in a passively mode-locked fiber laser. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 43214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermann, M.E.; Stock, M.L.; Andrejco, M.J.; Silberberg, Y. Passive mode locking by using nonlinear polarization evolution in a polarization-maintaining erbium-doped fiber. Opt. Lett. 1993, 18, 894–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamyshev, P. All-optical data regeneration based on self-phase modulation effect. In Proceedings of the ECOC ’98—24th European Conference on Optical Communication, Madrid, Spain, 20–24 September 1998; pp. 475–476. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, W.; Wright, L.G.; Sidorenko, P.; Backus, S.; Wise, F.W. Several new directions for ultrafast fiber lasers [Invited]. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 9432–9463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ziegler, Z.M.; Wright, L.G.; Wise, F.W. Megawatt peak power from a Mamyshev oscillator. Optica 2017, 4, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Chen, N.-K.; Zhang, L.; Xie, Y.; Tian, Z.; Yao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X. Output Pulse Characteristics of a Mamyshev Fiber Oscillator. Photonics 2021, 8, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitois, S.; Finot, C.; Provost, L.; Richardson, D.J. Generation of localized pulses from incoherent wave in optical fiber lines made of concatenated Mamyshev regenerators. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2008, 25, 1537–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regelskis, K.; Želudevičius, J.; Viskontas, K.; Račiukaitis, G. Ytterbium-doped fiber ultrashort pulse generator based on self-phase modulation and alternating spectral filtering. Opt. Lett. 2015, 40, 5255–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Ren, B.; Li, C.; Wu, J.; Su, R.; Ma, P.; Luo, Z.-C.; Zhou, P. Over 80 nJ Sub-100 fs All-Fiber Mamyshev Oscillator. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2021, 27, 3094508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorenko, P.; Fu, W.; Wright, L.G.; Olivier, M.; Wise, F.W. Self-seeded, multi-megawatt, Mamyshev oscillator. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 2672–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, M.; Boulanger, V.; Guilbert-Savary, F.; Sidorenko, P.; Wise, F.W.; Piché, M. Femtosecond fiber Mamyshev oscillator at 1550 nm. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 851–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repgen, P.; Schuhbauer, B.; Hinkelmann, M.; Wandt, D.; Wienke, A.; Morgner, U.; Neumann, J.; Kracht, D. Mode-locked pulses from a Thulium-doped fiber Mamyshev oscillator. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 13837–13844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Escobar, E.; Bello-Jiménez, M.; Pottiez, O.; Ibarra-Escamilla, B.; López-Estopier, R.; Duran-Sánchez, M.; Ramírez, M.A.G.; A Kuzin, E. Elimination of continuous-wave component in a figure-eight fiber laser based on a polarization asymmetrical NOLM. Laser Phys. 2017, 27, 075105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Z.; Luo, H.; Liu, Y.; Yan, Z.; Mou, C.; Zhang, L.; Turitsyn, S.K. All-fiber passively mode-locked Tm-doped NOLM-based oscillator operating at 2-μm in both soliton and noisy-pulse regimes. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 7875–7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Zhu, L. Generation of transition of dark into bright and harmonic pulses in a passively Er-doped fiber laser using nonlinear multimodal interference technique. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2021, 112, 103607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Cai, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zong, W.; Chen, L.; Zhang, Z. 374 fs pulse generation in an Er:fiber laser at a 225 MHz repetition rate. Opt. Lett. 2010, 35, 2858–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.; Luo, J.; Ng, B.P.; Yu, X. Dispersion-compensation-free femtosecond Tm-doped all-fiber laser with a 248 MHz repetition rate. Opt. Lett. 2016, 41, 4052–4055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, R.; Pan, D.; Li, Q.; Fu, H.Y. 115-MHz Linear NPE Fiber Laser Using All Polarization-Maintaining Fibers. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 2020, 33, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotor, J.; Sobon, G.; Tarka, J.; Pasternak, I.; Krajewska, A.; Strupinski, W.; Abramski, K.M. Passive synchronization of erbium and thulium doped fiber mode-locked lasers enhanced by common graphene saturable absorber. Opt. Express 2014, 22, 5536–5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotor, J.; Martynkien, T.; Schunemann, P.G.; Mergo, P.; Rutkowski, L.; Soboń, G. All-fiber mid-infrared source tunable from 6 to 9 μm based on difference frequency generation in OP-GaP crystal. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 11756–11763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Liu, S.; Liang, W.; Luo, S.; He, Z.; Ge, Y.; Wang, H.; Cao, R.; Zhang, F.; Wen, Q.; et al. Broadband Nonlinear Photonics in Few-Layer MXene Ti3C2Tx (T = F, O, or OH). Laser Photon. Rev. 2017, 12, 1700229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guo, Q.; Qiu, J. Emerging Low-Dimensional Materials for Nonlinear Optics and Ultrafast Photonics. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 201605886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, G.; Zhang, L.; Hu, W.; Yi, L. Automatic mode-locking fiber lasers: Progress and perspectives. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2020, 63, 160404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Configuration | Pulse Width (ps) | Pulse Energy (nJ) | Peak Power (W) | Wavelength (nm) | Pulse Profile | Repetition Rate (MHz) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring | 0.109 | 0.44 | 4000 | 1034.4 | Soliton | 50 | [34] |

| Linear | 0.135 | 4000 | 14,000 | 1582 | Soliton | 25.8 | [37] |

| Ring | 0.26 | 0.08 | 473 | 1060 | SP | 553 | [30] |

| Ring | 0.177 | 0.12 | 680 | 1034 | Soliton | 0.3971 | [38] |

| Linear | 1.52 | 2.9 | 1680 | 3434.2 | Soliton | 490 | [39] |

| Ring | 0.753 | 0.0041 | 5.4 | 1561.9 | Soliton | 23.5 | [40] |

| Linear | 3.6 | 2.4 × 10−4 | 0.062 | 1561 | Soliton | 5000 | [41] |

| Linear | 15 | 2.7 | 180 | 2791.3 | Soliton | 17.2 | [42] |

| Linear | 21 | 0.034 | 1.6 | 1064.1 | NGP | 1048 | [36] |

| Linear | 24 | 2.1 | 87.5 | 1034 | DS | 10.57 | [31] |

| Linear | 576 | 0.101 | 0.15 | 1061 | DS | 55 | [43] |

| Linear | 910 | 4.3 | 4.7 | 1068.76 | DS | 9.89 | [35] |

| Type | CNTs | Graphene | BP | TIs | TMDs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [44,45,46,47] | [48,49] | [50,51,52] | [53,54,55] | [56,57,58] | |

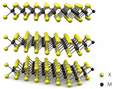

| Atomic structure |  |  |  |  |  |

| Bandgap | 0.5–1 eV | 0 eV | 0.35–2 eV | 0–0.7 eV | 1–2.5 eV |

| Carrier lifetime | Fast: <1 ps Slow: ~250 ps | Fast: <200 fs Slow: ~1 ps | Fast: 360 fs Slow: 1.36 ps | Fast: 0.3–2 ps Slow: 3–23 ps | Fast: 1–3 ps Slow: 70–400 ps |

| Configuration | SA | Pulse Width (ps) | Pulse Energy (nJ) | Peak Power (W) | Wavelength (nm) | Spectral Bandwidth (nm) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring | SWCNT | 0.226 | 2.35 | 10.4 × 103 | 1561.8 | 13.9 | [64] |

| Ring | SWCNT | 0.249 | 0.221 | 83.3 | 1550 | 9.3 | [100] |

| Linear | CNT-PVA | 0.816 | - | - | 1562.3 | 3.6 | [66] |

| Ring | CNTs | 0.829 | - | - | 1565 | 3.1 | [62] |

| Ring | CNTs | 0.9 | 0.59 | 1.06 × 103 | 1560 | 2.8 | [63] |

| Ring | SWCNT | 276 | 0.103 | 0.373 | 1064 | 0.57 | [101] |

| Ring | Graphene | 0.694 | 0.507 | 731 | 1558.35 | 4.21 | [69] |

| Ring | Graphene | 0.756 | 1.12 | 1.48 × 103 | 1565 | 5 | [68] |

| Ring | Graphene | 2.1 | 0.08 | 38.1 | 1953.3 | 2.2 | [70] |

| Ring | BP | 0.335 | 0.119 | 173 | 1561 | 8.4 | [79] |

| Ring | BP | 0.739 | 0.0407 | 55 | 1910 | 5.8 | [78] |

| Ring | BP | 0.786 | - | - | 1565 | 3.8 | [77] |

| Ring | BP | 1.17 | 5.4 | 4.7 × 103 | 1556.2 | 2.2 | [74] |

| Linear | BP | 42 | 25.5 | 610 | 2783 | 2.8 | [80] |

| Linear | BP | - | - | - | 3489 | 4.7 | [81] |

| Ring | Sb2Te3 | 0.27 | 0.029 | 95 | 1561 | 10.3 | [87] |

| Ring | Bi2Se2Te | 0.583 | 29.62 | 5.08 × 103 | 1561.5 | 3.6 | [89] |

| Ring | Bi2Se3 | 0.63 | 0.211 | 334.9 | 1565 | 7.9 | [88] |

| Ring | Bi2Te3 | 1.21 | - | - | 1158.4 | 2.69 | [86] |

| Ring | Bi2Te3 | 1.26 | - | - | 1909.5 | 5.64 | [83] |

| Linear | Bi2Se3 | 46 | 0.756 | 16.4 × 103 | 1031.7 | 2.5 | [75] |

| Ring | WS2 | 0.66 | - | - | 1557 | 4.0 | [93] |

| Ring | VSe2 | 0.67 | 0.441 | 620 | 1561.5 | 4.1 | [76] |

| Ring | WSe2 | 0.698 | 0.21 | 300.6 | 1555.2 | 4.6 | [95] |

| Ring | PdS2 | 0.766 | 0.045 | 58.5 | 1566 | 4.16 | [96] |

| Linear | MoS2-PVA | 0.96 | 0.065 | 67.7 | 1535–1565 | 3.0 | [92] |

| Linear | MoSe2 | 1 | 0.123 | 12.3 | 1558.35 | 2.9 | [94] |

| Linear | MoS2 | 800 | 1.41 | 1.76 | 1054.3 | 2.7 | [91] |

| Configuration | SA | Pulse Width (ps) | Pulse Energy (nJ) | Peak Power (W) | Wavelength (nm) | Repetition Rate (MHz) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ring | NALM | 0.215 | 0.214 | 1 × 103 | 1030 | 700.1 | [104] |

| Ring | NALM | 0.344 | 0.3 | 870 | 1027 | 10 | [105] |

| Ring | NALM | 0.615 | 32 | 52 × 103 | 1030 | 2.47 | [106] |

| Ring | NOLM | 1.39 | 0.718 | 51.6 × 105 | 1559.7 | 0.8 | [135] |

| Ring | NOLM | 2.8 | 0.0838 | 29.9 | 2017.33 | 1.51 | [136] |

| Ring | NALM | 57.3 | 2.85 | 23 | 717.5 | 14.58 | [109] |

| Ring | NLMMI | 1.8 | 0.0305 | 19.1 | 1559 | 49.8 | [111] |

| Linear | NLMMI | 2.3–2.5 | - | - | 1529/1558 | 5.66 | [115] |

| Ring | NLMMI | 46 | 0.0368 | 0.8 | 1958 | 8.58 | [114] |

| Ring | NLMMI | 136 | - | - | 1562 | 40 | [137] |

| Linear | NLMMI + NPR | - | - | - | 1064 | 12.8 | [112] |

| Ring | NPR | 0.037 | 0.31 | 8.29 × 103 | 1550 | 225 | [138] |

| Linear | NPR | 0.117 | 0.06 | 513 | 1550 | 12.1 | [120] |

| Ring | NPR | 0.276 | 1.51 | 5.16 × 103 | 1584.8 | 32.5 | [119] |

| Ring | NPR | 0.89 | 0.75 | 840 | 1950 | 248 | [139] |

| Linear | NPR | 1.2 | 0.11 | 91.7 | 1573 | 115 | [140] |

| Ring | NPR | 1.25 | 0.0262 | 100 | 1584.2 | 3.9 | [121] |

| Ring | Mamyshev | 0.056 | 83.5 | 1.15 × 106 | 1022.2 | 9.43 | [131] |

| Ring | Mamyshev | 0.093 | 31.3 | 60 × 103 | 1550 | 7.35 | [133] |

| Linear | Mamyshev | 0.208 | 3.55 | 17.1 × 103 | 1965 | 15.027 | [134] |

| Linear | Mamyshev | 3.1 | 0.73 | 235 | 1060 | 14.52 | [130] |

| Linear | Mamyshev | 4.16 | 8.6 | 2.07 × 103 | 1062.53 | 15.18 | [128] |

| Ring | Mamyshev | 6 | 50 | 1 × 106 | 1035 | 17 | [127] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xie, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, F.; Liu, W. Research Progress of Passively Mode-Locked Fiber Lasers Based on Saturable Absorbers. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231819

Xie J, Liu T, Liu X, Wang F, Liu W. Research Progress of Passively Mode-Locked Fiber Lasers Based on Saturable Absorbers. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231819

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Jiayi, Tengfei Liu, Xilong Liu, Fang Wang, and Weiwei Liu. 2025. "Research Progress of Passively Mode-Locked Fiber Lasers Based on Saturable Absorbers" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231819

APA StyleXie, J., Liu, T., Liu, X., Wang, F., & Liu, W. (2025). Research Progress of Passively Mode-Locked Fiber Lasers Based on Saturable Absorbers. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1819. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231819