Enhanced Light–Matter Interaction in Porous Silicon Microcavities Structurally Optimized Using Theoretical Simulation and Experimental Validation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Models

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

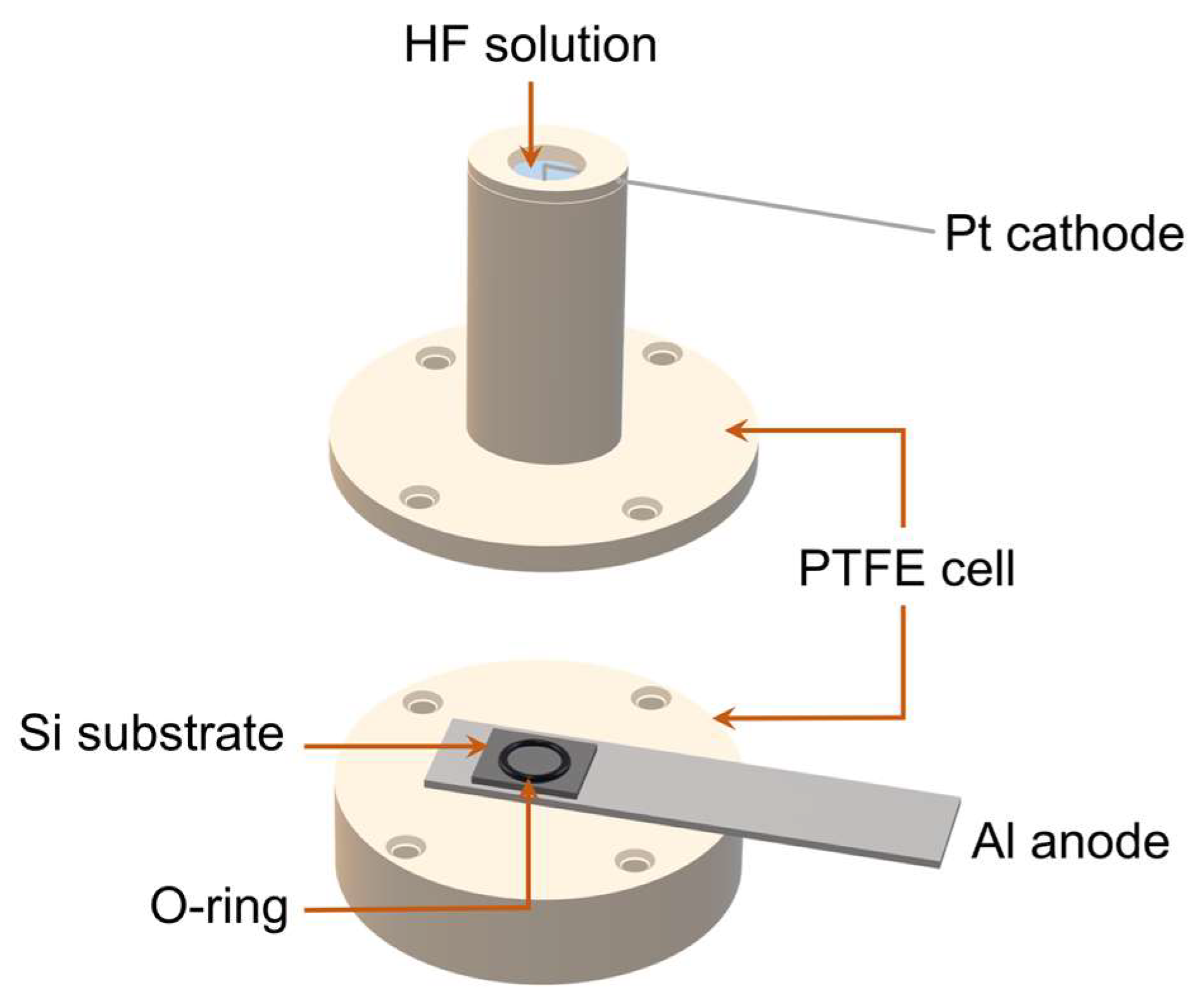

3.2. Experimental Procedure

3.3. Characterization

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Optimization of the Etching Time

4.2. Optimization of the Refractive Index Contrast and Layer Arrangement

4.3. Embedment of a Fluorescent Dye into Optimized Porous Silicon Microcavities

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CaF2 | Calcium fluoride |

| DBRs | Distributed Bragg reflectors |

| FEM | Finite element method |

| FDTD | Finite-difference time-domain |

| FP | Fabry–Pérot |

| FWHM | Full width at half maximum |

| HF | Hydrofluoric acid |

| IUPAC | International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry |

| β-LG | β-Lactoglobulin |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| PMLs | Perfectly matched layers |

| pSi | Porous silicon |

| pSiMC | Porous silicon microcavity |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoroethylene |

| R6G | Rhodamine 6G |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TMM | The transfer matrix model |

| QF | Quality factor |

| QD | Quantum dot |

| WGM | Whispering-gallery mode |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

References

- Guo, Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, Y.; Tian, B.; Fan, X.; He, Y.; Liu, M.; Peng, L.; Tang, N.; Tan, T.; et al. Optical Microcavities Empowered Biochemical Sensing: Status and Prospects. Adv. Devices Instrum. 2024, 5, 0041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibben, D.J.; Bonin, G.O.; Cho, I.; Lakhwani, G.; Hutchison, J.; Gómez, D.E. Molecular Energy Transfer Under the Strong Light–Matter Interaction Regime. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 8044–8068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, T.; Dhawan, A.R.; Marshall, A.R.; Ghorbal, A.; Son, W.; Snaith, H.J.; Smith, J.M.; Taylor, R.A. Ultranarrow Line Width Room-Temperature Single-Photon Source from Perovskite Quantum Dot Embedded in Optical Microcavity. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 10667–10673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granizo, E.; Samokhvalov, P.; Nabiev, I. Functionalized Optical Microcavities for Sensing Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koya, A.N. Plasmonic Nanoarchitectures for Single-Molecule Explorations: An Overview. Adv. Photonics Res. 2022, 3, 2100325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausaite-Minkstimiene, A.; Popov, A.; Ramanaviciene, A. Ultra-Sensitive SPR Immunosensors: A Comprehensive Review of Labeling and Interface Modification Using Nanostructures. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 170, 117468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ming, H. Review of Surface Plasmon Resonance and Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor. Photonic Sens. 2012, 2, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Guo, Z. Integrated Sensor with a Whispering-Gallery Mode and Surface Plasmonic Resonance for the Enhanced Detection of Viruses. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2021, 38, 2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, Y.; Ma, L.; Schmidt, O.G. Recent Progress on Optoplasmonic Whispering-Gallery-Mode Microcavities. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chaudhary, B.; Upadhyay, A.; Sharma, D.; Ayyanar, N.; Taya, S.A. A Review on Various Sensing Prospects of SPR Based Photonic Crystal Fibers. Photonics Nanostructures-Fundam. Appl. 2023, 54, 101119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganami, Y.; Oshikiri, T.; Shi, X.; Misawa, H. Water Oxidation under Modal Ultrastrong Coupling Conditions Using Gold/Silver Alloy Nanoparticles and Fabry–Pérot Nanocavities. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 18438–18442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perin, G.; Ruel, L.; Dumeige, Y.; Féron, P.; Trebaol, S. High-Q Whispering-Gallery-Modes Microresonators for Laser Frequency Locking in the Near-Ultraviolet Spectral Range. J. Light. Technol. 2024, 42, 5214–5222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lohrey, T.; Nguyen, P.-D.; Min, Z.; Tang, Y.; Ge, C.; Sercel, Z.P.; McLeod, E.; Stoltz, B.M.; Su, J. Part-per-Trillion Trace Selective Gas Detection Using Frequency Locked Whispering-Gallery Mode Microtoroids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 42430–42440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, F.; Golmohammadi, S.; Bahador, H.; Soofi, H. Design of a High-Sensitivity Graphene-Silicon Hybrid Micro-Disk in a Square Cavity Whispering Gallery Mode Biosensor. J. Nanopart Res. 2023, 25, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halendy, M.; Ertman, S. Whispering-Gallery Mode Micro-Ring Resonator Integrated with a Single-Core Fiber Tip for Refractive Index Sensing. Sensors 2023, 23, 9424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Will, E.; Masters, L.; Rauschenbeutel, A.; Scheucher, M.; Volz, J. Coupling a Single Trapped Atom to a Whispering-Gallery-Mode Microresonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 126, 233602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Guo, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Luo, M.; Wu, X. Optical Whispering-Gallery-Mode Microbubble Sensors. Micromachines 2022, 13, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkis, R.; Reinis, P.K.; Milgrave, L.; Draguns, K.; Salgals, T.; Brice, I.; Alnis, J.; Atvars, A. Wavelength Sensing Based on Whispering Gallery Mode Mapping. Fibers 2022, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gong, H.; He, X.; Xu, B.; Zhao, C.; Shen, C. Temperature and Humidity Sensor Based on PMMA Microsphere Whispering-Gallery-Mode Resonator. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 41244–41250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinidis, N.; Giouni, P.; Sarakatsianos, V.; Korakas, N.; Pissadakis, S. A Study on the Photo-Elasticity of Potassium Ion-Exchanged Borosilicate Glass, Using Whispering Gallery Mode Resonation. Opt. Mater. 2025, 168, 117392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, D.; Avino, S.; Gagliardi, G. Direct Nanoparticle Sensing in Liquids with Free-Space Excited Optical Whispering-Gallery-Mode Microresonators. Sensors 2025, 25, 5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min’kov, K.N.; Shitikov, A.E.; Danilin, A.N.; Lobanov, V.E.; Bilenko, I.A. Fabrication of High-Q Crystalline Whispering Gallery Mode Microcavities Using Single-Point Diamond Turning. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Optics + Laser Science 2021, Washington, DC, USA, 1–4 November 2021; Optica Publishing Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; p. JTu1A.102. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Xie, C.; Wang, M.; Cai, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wei, B.; Shi, J.; He, X. Brillouin-Kerr Optical Frequency Comb in Microcavity of Calcium Fluoride Crystal. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavatamane, V.K.; Carvalho, N.C.; El-Hamamsy, A.; Zohari, E.; Barclay, P.E. Reversing Annealing-Induced Optical Loss in Diamond Microcavities. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.03585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazuryk, J.; Paszke, P.; Pawlak, D.A.; Kutner, W.; Sharma, P.S. Fabrication, Characterization, and Sensor Applications of Polymer-Based Whispering Gallery Mode Microresonators. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 5314–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhao, J.; Lv, R.; Han, B.; Zhao, Y. Design of a Vernier Effect Assisted Optical Fiber WGM Microbottle for a Highly Sensitive Temperature Measurement. Opt. Lett. 2025, 50, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Ozdemir, S.K.; Zhu, J.; Yang, L. Scatterer Induced Mode Splitting in Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Coated Microresonators. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 221101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, A.; Wu, Y.; Ji, J.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, X.; Sang, S. Low Cell Concentration Detection by Fabry-Pérot Resonator with Sensitivity Enhancement by Dielectrophoresis. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 331, 112977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, C.; Hou, S.; Lian, J.; Si, Q.; Gao, F.; Zhang, F. Vibrational Coupling with O–H Stretching Increases Catalytic Efficiency of Sucrase in Fabry–Pérot Microcavity. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 652, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinoglu, G.E.; Quan, D.; Rokhsat, E.; Hutchison, J.A. Tensile Control of Vibrational Strong Light-Matter Coupling with Flexible Polyester Films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2403657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menghrajani, K.S.; Chen, M.; Dholakia, K.; Barnes, W.L. Probing Vibrational Strong Coupling of Molecules with Wavelength-Modulated Raman Spectroscopy. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 10, 2102065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, K.; Andell Hutchison, J.; Uji-i, H. Optical Cavity Design and Functionality for Molecular Strong Coupling. Chem. A Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202303110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandini, V.L.; Malini, V.L.; Mathias, R.; Veena, P.N.; Raju, R.K.; Rodriguez, C.; Islam, S. One-Dimensional Defect Micro-Cavity Optical Bragg Reflector Biosensor for the Detection of CHIKV Virus. J. Opt. 2024, 53, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiβ, W.; Henkel, S.; Arntzen, M. Connecting Microscopic and Macroscopic Properties of Porous Media: Choosing Appropriate Effective Medium Concepts. Thin Solid Film. 1995, 255, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gryga, M.; Ciprian, D.; Hlubina, P. Distributed Bragg Reflectors Employed in Sensors and Filters Based on Cavity-Mode Spectral-Domain Resonances. Sensors 2022, 22, 3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serov, Y.M.; Galimov, A.I.; Toropov, A.A. Investigation of the Biexciton Radiative Cascade in a Single InAs/GaAs Quantum Dot Embedded in a High-Q Microcavity. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2023, 87, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, G.; Coviello, V.; Persichetti, G.; Bernini, R. High Performance Polymeric Fabry-Pérot Microcavities for Sensing and Lasing Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntyi, O.; Zozulya, G.; Shepida, M. Porous Silicon Formation by Electrochemical Etching. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, e1482877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlir, A. Electrolytic Shaping of Germanium and Silicon. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1956, 35, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.R. Electropolishing Silicon in Hydrofluoric Acid Solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1958, 105, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canham, L.T. Silicon Quantum Wire Array Fabrication by Electrochemical and Chemical Dissolution of Wafers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1990, 57, 1046–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A.S.; Teplinskaia, A.S. Thermal Properties of Porous Silicon Nanomaterials. Materials 2022, 15, 8678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriukova, I.S.; Granizo, E.A.; Knysh, A.A.; Samokhvalov, P.S.; Nabiev, I.R. Controlling the Luminescence of Quantum Dots in Hybrid Structures Based on Porous Silicon. Phys. At. Nucl. 2024, 87, 1750–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretta, R.; De Stefano, L.; Terracciano, M.; Rea, I. Porous Silicon Optical Devices: Recent Advances in Biosensing Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, R.H.; Baek, S.W.; Oh, C.-K.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, D. Recent Advances of Macrostructural Porous Silicon for Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 5609–5626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naiyeju, I.S.; Bimbo, L.M. Biocompatibility of Porous Silicon. In Porous Silicon for Biomedical Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 149–180. ISBN 978-0-12-821677-4. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, N.; Renka, S.; Raić, M.; Ristić, D.; Ivanda, M. Effects of Thermal Oxidation on Sensing Properties of Porous Silicon. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layouni, R.; Choudhury, M.H.; Laibinis, P.E.; Weiss, S.M. Thermally Carbonized Porous Silicon for Robust Label-Free DNA Optical Sensing. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khung, Y.L. Hydrosilylation of Porous Silicon: Unusual Possibilities and Potential Challenges. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 338, 103416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girel, K.; Burko, A.; Zavatski, S.; Barysiuk, A.; Litvinova, K.; Eganova, E.; Tarasov, A.; Novikov, D.; Dubkov, S.; Bandarenka, H. Atomic Layer Deposition of Hafnium Oxide on Porous Silicon to Form a Template for Athermal SERS-Active Substrates. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harraz, F.A. Porous Silicon Chemical Sensors and Biosensors: A Review. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 202, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.L.; Collins, S.D. Porous Silicon Formation Mechanisms. J. Appl. Phys. 1992, 71, R1–R22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo-Taboada, L.H.; Chiñas-Castillo, F.; Caballero-Caballero, M.; Camacho-López, S.; Méndez-Blas, A.; Jiménez-Jarquín, J.F.; Feria-Reyes, R.; Suarez-Martínez, R.; Serrano-de La Rosa, L.E.; Barranco-Cisneros, J.; et al. Hybrid Micro and Nanostructured Silicon Surfaces Fabricated by Laser Ablation and Electrochemistry. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 3275–3282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, F.; Ma, M.; Liu, Z. Fabrication of Highly Ordered Macropore Arrays in P-Type Silicon by Electrochemical Etching: Effect of Wafer Resistivity and Other Etching Parameters. Micromachines 2025, 16, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.-Y.; Hsu, H.-H.; Muhammed Musthafa, A.; Lin, I.-A.; Chou, C.-M.; Hsiao, V.K.S. Tuning Multi-Wavelength Reflection Properties of Porous Silicon Bragg Reflectors Using Silver-Nanoparticle-Assisted Electrochemical Etching. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhusaini, Q.; Scheld, W.S.; Jia, Z.; Das, D.; Afzal, F.; Müller, M.; Schönherr, H. Bare Eye Detection of Bacterial Enzymes of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa with Polymer Modified Nanoporous Silicon Rugate Filters. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.T.; Bui, H.; Hoang, T.H.C.; Pham, V.H.; Loan, N.T.; Le, L.V.; Pham, T.B.; Duc, C.V.; Do, T.C.; Kim, T.J.; et al. Silver Nanoparticles-Decorated Porous Silicon Microcavity as a High-Performance SERS Substrate for Ultrasensitive Detection of Trace-Level Molecules. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, I.; Skryshevsky, V.; Belarouci, A. Engineering Porous Silicon-Based Microcavity for Chemical Sensing. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 21265–21276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Gao, Y.; Wang, J.; Aili, T.; Jia, Z.; Lv, X.; Huang, X.; Yang, J. Detection of β-Lactoglobulin by a Porous Silicon Microcavity Biosensor Based on the Angle Spectrum. Sensors 2022, 22, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yue, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, J.; Jia, Z.; Lv, X.; Huang, X. Gibberellins Detection Based on Fluorescence Images of Porous Silicon Microcavities. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 9049–9057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, J.L.M.; Huanca, D.R.; Oliveira, A.F. One-Dimensional Porous Silicon Photonic Crystals for Chemosensors: Geometrical Factors Influencing the Sensitivity. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2023, 364, 114784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryukova, I.S.; Dovzhenko, D.S.; Rakovich, Y.P.; Nabiev, I.R. Enhancement of the Quantum Dot Photoluminescence Using Transfer-Printed Porous Silicon Microcavities. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1461, 012076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, V.; Guerrero, S.E.; Lara-García, H.A.; Bryche, J.-F.; Del Rocío Nava Lara, M.; Morris, D.; Reyes-Esqueda, J.-A. Room-Temperature Strong Coupling for CsPbBr3 Quantum Dots and Porous-Silicon Cavities: Cavity-Detuning Control and Polariton Redundancy. In Proceedings of the Frontiers in Optics + Laser Science 2023 (FiO, LS), Tacoma, WA, USA, 9–12 October 2023; Optica Publishing Group: Tacoma, WA, USA, 2023; p. JTu5A.11. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, J.; Ren, X.; Zhang, X.; Lai, W.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, G.; Zha, N.; Ye, Y.; Xu, S.; et al. In Situ Ring Opening Polymerization of High-Performance Full-Color CsPbX3 @PDMS (X = Cl, Br, I) Nanospheres Toward Wide-Color-Gamut Displays. Small 2025, 21, 2410180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Lai, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Ye, Y.; Xu, S.; Yan, Q.; et al. Pushing Patterning Limits of Drop-On-Demand Inkjet Printing with Cspbbr3/PDMS Nanoparticles. Laser Amp. Photonics Rev. 2024, 18, 2400298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrovsky, A.; Svyakhovskiy, S.; Bogdanov, A.; Shibaev, V.; Cigl, M.; Hamplová, V.; Bubnov, A. Photocontrollable Photonic Crystals Based on Porous Silicon Filled with Photochromic Liquid Crystalline Mixture. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2001267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, H.N.; Nayef, U.M.; Mutlak, F.A.-H.; Muslim, A.M.; Muayad, M.W. Synthesis of Fe3O4 NPs on Porous Silicon for Photoluminescence-Based Humidity Sensor. Plasmonics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Alfaro, H.F.; Barranco-Cisneros, J.; Torres-Rosales, A.A.; Del Pozo-Zamudio, O.; Solís-Macías, J.; Ariza-Flores, A.D.; Cerda-Méndez, E.A. In Situ and Real-Time Optical Study of Passive Chemical Etching of Porous Silicon and Its Impact on the Fabrication of Thin Layers and Multilayers. J. Appl. Phys. 2023, 134, 085305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, S.E.; Kan, P.Y.Y.; Finstad, T.G. Single Beam Determination of Porosity and Etch Rate in Situ During Etching of Porous Silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 114909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepela, L.; Lishchuk, P.; Shevchenko, V.; Kuryliuk, V.; Polishchuk, E.; Kuzmich, A.; Teselko, P.; Matushko, I.; Borovyi, M. Fabrication and Photoacoustic Characterization of Multilayered Structures Based on Porous Silicon. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 41st International Conference on Electronics and Nanotechnology (ELNANO), Kyiv, Ukraine, 10–14 October 2022; IEEE: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022; pp. 178–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Gutierrez, C.F.; Lujan-Cabrera, I.A.; Isaza, C.; Anaya Rivera, E.K.; Rodriguez-Garcia, M.E. In Situ Photoacoustic Study of Optical Properties of P-Type (111) Porous Silicon Thin Films. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.; Zhang, S.; Fan, Q.; Ni, X.; Fan, Y.; Fan, D.; Zhang, S.; Tao, L.; Gu, X. Proximal Light Field Control in Red InGaN Micro-LEDs via Evolution-Algorithm-Designed Multilayer Stacks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 127, 133504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, D.; Horak, P. Evolutionary Algorithm to Design High-Cooperativity Optical Cavities. New J. Phys. 2022, 24, 073028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Vazquez, E.; Lujan-Cabrera, I.A.; Isaza, C.; Rizzo-Sierra, J.A.; Ramirez-Gutierrez, C.F. Design of Broadband Modulated One-Dimensional Photonic Crystals Based on Porous Silicon Using Evolutionary Search. Optik 2022, 260, 169002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Lee, H.; Ju, C.; Han, H. Enhanced DBR Mirror Design via D3QN: A Reinforcement Learning Approach. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0307211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, D.V.; Kurdiumov, S.; Horak, P. Convolutional Neural Networks for Mode On-Demand High Finesse Optical Resonator Design. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 15567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Cao, J.; Liu, J. Harnessing Artificial Neural Networks for Inverse Design and Analysis of MEMS-Based Fabry–Pérot Filters. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 373, 115433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujan-Cabrera, I.A.; Isaza, C.; Anaya-Rivera, E.K.; Ramirez-Gutierrez, C.F. Inverse Design of Incommensurate One-Dimensional Porous Silicon Photonic Crystals Using 2D-Convolutional Mixture Density Neural Networks. Photonics Nanostructures-Fundam. Appl. 2024, 59, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granchi, N.; Spalding, R.; Lodde, M.; Petruzzella, M.; Otten, F.W.; Fiore, A.; Intonti, F.; Sapienza, R.; Florescu, M.; Gurioli, M. Near-Field Investigation of Luminescent Hyperuniform Disordered Materials. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2022, 10, 2102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggeman, D.A.G. Berechnung Verschiedener Physikalischer Konstanten von Heterogenen Substanzen. I. Dielektrizitätskonstanten Und Leitfähigkeiten Der Mischkörper Aus Isotropen Substanzen. Ann. Der Phys. 1935, 416, 636–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swe, S.K.; Noh, H. Inverse Design of Reflectionless Thin-Film Multilayers with Optical Absorption Utilizing Tandem Neural Network. Photonics 2024, 11, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, I.V.; Eliseeva, S.V.; Sementsov, D.I. Transmission and Reflection Spectra of a Bragg Microcavity Filled with a Periodic Graphene-Containing Structure. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, D.W.; Heinrich, J.C. The Finite Element Method: Basic Concepts and Applications with MATLAB®, MAPLE, and COMSOL, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-39510-4. [Google Scholar]

- Oskooi, A.F.; Roundy, D.; Ibanescu, M.; Bermel, P.; Joannopoulos, J.D.; Johnson, S.G. Meep: A Flexible Free-Software Package for Electromagnetic Simulations by the FDTD Method. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2010, 181, 687–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotkovskiy, G.E.; Kuzishchin, Y.A.; Martynov, I.L.; Chistyakov, A.A.; Nabiev, I. The Photophysics of Porous Silicon: Technological and Biomedical Implications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 13890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vokhmintcev, K.V.; Samokhvalov, P.S.; Nabiev, I. Charge Transfer and Separation in Photoexcited Quantum Dot-Based Systems. Nano Today 2016, 11, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, J.; Arganda-Carreras, I.; Frise, E.; Kaynig, V.; Longair, M.; Pietzsch, T.; Preibisch, S.; Rueden, C.; Saalfeld, S.; Schmid, B.; et al. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vercauteren, R.; Scheen, G.; Raskin, J.-P.; Francis, L.A. Porous Silicon Membranes and Their Applications: Recent Advances. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021, 318, 112486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubin, R.F.; Fletcher, A.N. Fluorescence Quantum Yields of Some Rhodamine Dyes. J. Lumin. 1982, 27, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruminski, A.M.; Barillaro, G.; Chaffin, C.; Sailor, M.J. Internally Referenced Remote Sensors for HF and Cl2 Using Reactive Porous Silicon Photonic Crystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2011, 21, 1511–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, W.H.; Létant, S.; Sailor, M.J. Electrochemical Formation and Modification of Nanocrystalline Porous Silicon. In Electrochemistry of Nanomaterials; Hodes, G., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 141–167. ISBN 978-3-527-29836-5. [Google Scholar]

- Arshavsky-Graham, S.; Massad-Ivanir, N.; Segal, E.; Weiss, S. Porous Silicon-Based Photonic Biosensors: Current Status and Emerging Applications. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, E.M. Spontaneous Emission Probabilities at Radio Frequencies. In Confined Electrons and Photons; Burstein, E., Weisbuch, C., Eds.; NATO ASI Series; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; Volume 340, p. 839. ISBN 978-1-4613-5807-7. [Google Scholar]

- Huanca, D.R.; Gomes, A.M.C. Fabrication and Optical Characterization of Porous Silicon Heterostructure as Matrix for Sensing Organic Solvent via Resonance Peak and Q Factor Shift. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 379, 115962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Mo, J.; Zhong, F.; Lv, C.; Ma, J.; Jia, Z. Hybridization Assay of Insect Antifreezing Protein Gene by Novel Multilayered Porous Silicon Nucleic Acid Biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 39, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanueva, J.L.M.; Huanca, D.R.; Oliveira, A.F. Thickness and Porosity Characterization in Porous Silicon Photonic Crystals: The Etch-Stop Effect. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 307, 128070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovzhenko, D.; Krivenkov, V.; Kriukova, I.; Samokhvalov, P.; Karaulov, A.; Nabiev, I. Enhanced Spontaneous Emission from Two-Photon-Pumped Quantum Dots in a Porous Silicon Microcavity. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 5364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cencha, L.G.; Antonio Hernández, C.; Forzani, L.; Urteaga, R.; Koropecki, R.R. Optical Performance of Hybrid Porous Silicon–Porous Alumina Multilayers. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 183101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenie, S.N.A.; Pace, S.; Sciacca, B.; Brooks, R.D.; Plush, S.E.; Voelcker, N.H. Lanthanide Luminescence Enhancements in Porous Silicon Resonant Microcavities. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 12012–12021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Robbiano, V.; Paternò, G.M.; Carnicella, G.; Debrassi, A.; La Mattina, A.A.; Mariani, S.; Minotto, A.; Egri, G.; Dähne, L.; et al. Nanoscale Photoluminescence Manipulation in Monolithic Porous Silicon Oxide Microcavity Coated with Rhodamine-Labeled Polyelectrolyte via Electrostatic Nanoassembling. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2021, 9, 2100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriukova, I.S.; Krivenkov, V.A.; Samokhvalov, P.S.; Nabiev, I.R. Weak Coupling between Light and Matter in Photonic Crystals Based on Porous Silicon Responsible for the Enhancement of Fluorescence of Quantum Dots under Two-Photon Excitation. Jetp Lett. 2020, 112, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovzhenko, D.; Osipov, E.; Martynov, I.; Samokhvalov, P.; Eremin, I.; Kotkovskii, G.; Chistyakov, A. Porous Silicon Microcavity Modulates the Photoluminescence Spectra of Organic Polymers and Quantum Dots. Mater. Today Proc. 2016, 3, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reece, P.J.; Lérondel, G.; Zheng, W.H.; Gal, M. Optical Microcavities with Subnanometer Linewidths Based on Porous Silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 81, 4895–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghulinyan, M.; Oton, C.J.; Bonetti, G.; Gaburro, Z.; Pavesi, L. Free-Standing Porous Silicon Single and Multiple Optical Cavities. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 9724–9729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugall, J.T.; Singh, A.; Van Hulst, N.F. Plasmonic Cavity Coupling. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, M.; Semenov, A.; Ochoa, M.A.; Nitzan, A. Strong Coupling in Infrared Plasmonic Cavities. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 9673–9678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Ozdemir, S.K.; Xiao, Y.-F.; Li, L.; He, L.; Chen, D.-R.; Yang, L. On-Chip Single Nanoparticle Detection and Sizing by Mode Splitting in an Ultrahigh-Q Microresonator. Nat. Photon 2010, 4, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Lu, Q.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, X.; Xie, S. Combining Whispering Gallery Mode Optofluidic Microbubble Resonator Sensor with GR-5 DNAzyme for Ultra-Sensitive Lead Ion Detection. Talanta 2020, 213, 120815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granizo, E.; Kriukova, I.; Escudero-Villa, P.; Samokhvalov, P.; Nabiev, I. Microfluidics and Nanofluidics in Strong Light–Matter Coupling Systems. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspnes, D.E.; Studna, A.A. Dielectric Functions and Optical Parameters of Si, Ge, GaP, GaAs, GaSb, InP, InAs, and InSb from 1.5 to 6.0 eV. Phys. Rev. B 1983, 27, 985–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malitson, I.H. Interspecimen Comparison of the Refractive Index of Fused Silica*,†. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1965, 55, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, B.E.A.; Teich, M.C. Fundamentals of Photonics, 1st ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-471-83965-1. [Google Scholar]

- Topasna, D.M.; Topasna, G.A. Numerical Modeling of Thin Film Optical Filters. In Proceedings of the Education and Training in Optics and Photonics, St. Asaph, UK, 5–7 June 2009; OSA: St. Asaph, North Wales, 2009; p. EP5. [Google Scholar]

- Kajikawa, K.; Okamoto, T. Optical Electromagnetic Field Analysis Using Python: Practical Application in Metallic and Dielectric Nanostructures, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; ISBN 978-1-003-35767-4. [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes, S.J. Multilayer Optical Calculations. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1603.02720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovzhenko, D.; Martynov, I.; Samokhvalov, P.; Osipov, E.; Lednev, M.; Chistyakov, A.; Karaulov, A.; Nabiev, I. Enhancement of Spontaneous Emission of Semiconductor Quantum Dots inside One-Dimensional Porous Silicon Photonic Crystals. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 22705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granizo, E.; Kriukova, I.; Escudero-Villa, P.; Samokhvalov, P.; Nabiev, I. Enhanced Fluorescence Emission of a Single Quantum Dot in a Porous Silicon Photonic Crystal—Plasmonic Hybrid Resonator. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2796, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microcavity Fabrication Technique | Wafer Type | Eigenmode Wavelength, nm | Eigenmode FWHM, nm | QF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-optimized | 0.001–0.005 Ω·cm (S1) | 684 | 9.8 | 69.8 |

| 0.004–0.006 Ω·cm (S2) | 644 | 8.05 | 80 | |

| Optimized | 0.001–0.005 Ω·cm (S1) | 678 | 4.8 | 141.3 |

| 0.004–0.006 Ω·cm (S2) | 644 | 5.6 | 115.6 |

| Microcavity Fabrication Technique | Structure | Eigenmode Wavelength, nm | Eigenmode FWHM, nm | QF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-optimized | (LH)5L2(HL)20 | 651 | 6.6 | 95.5 |

| (LH)6L2(HL)10 | 653 | 5.4 | 121.1 | |

| Optimized | (LH)6L2(HL)10 | 648 | 4.8 | 135.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Granizo, E.; Kriukova, I.S.; Knysh, A.A.; Sokolov, P.M.; Samokhvalov, P.S.; Nabiev, I.R. Enhanced Light–Matter Interaction in Porous Silicon Microcavities Structurally Optimized Using Theoretical Simulation and Experimental Validation. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1808. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231808

Granizo E, Kriukova IS, Knysh AA, Sokolov PM, Samokhvalov PS, Nabiev IR. Enhanced Light–Matter Interaction in Porous Silicon Microcavities Structurally Optimized Using Theoretical Simulation and Experimental Validation. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1808. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231808

Chicago/Turabian StyleGranizo, Evelyn, Irina S. Kriukova, Aleksandr A. Knysh, Pavel M. Sokolov, Pavel S. Samokhvalov, and Igor R. Nabiev. 2025. "Enhanced Light–Matter Interaction in Porous Silicon Microcavities Structurally Optimized Using Theoretical Simulation and Experimental Validation" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1808. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231808

APA StyleGranizo, E., Kriukova, I. S., Knysh, A. A., Sokolov, P. M., Samokhvalov, P. S., & Nabiev, I. R. (2025). Enhanced Light–Matter Interaction in Porous Silicon Microcavities Structurally Optimized Using Theoretical Simulation and Experimental Validation. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1808. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231808