Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study of Deposition Behavior for Cold-Sprayed Nano-Structured HA/70wt.%Ti Composite Coating

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

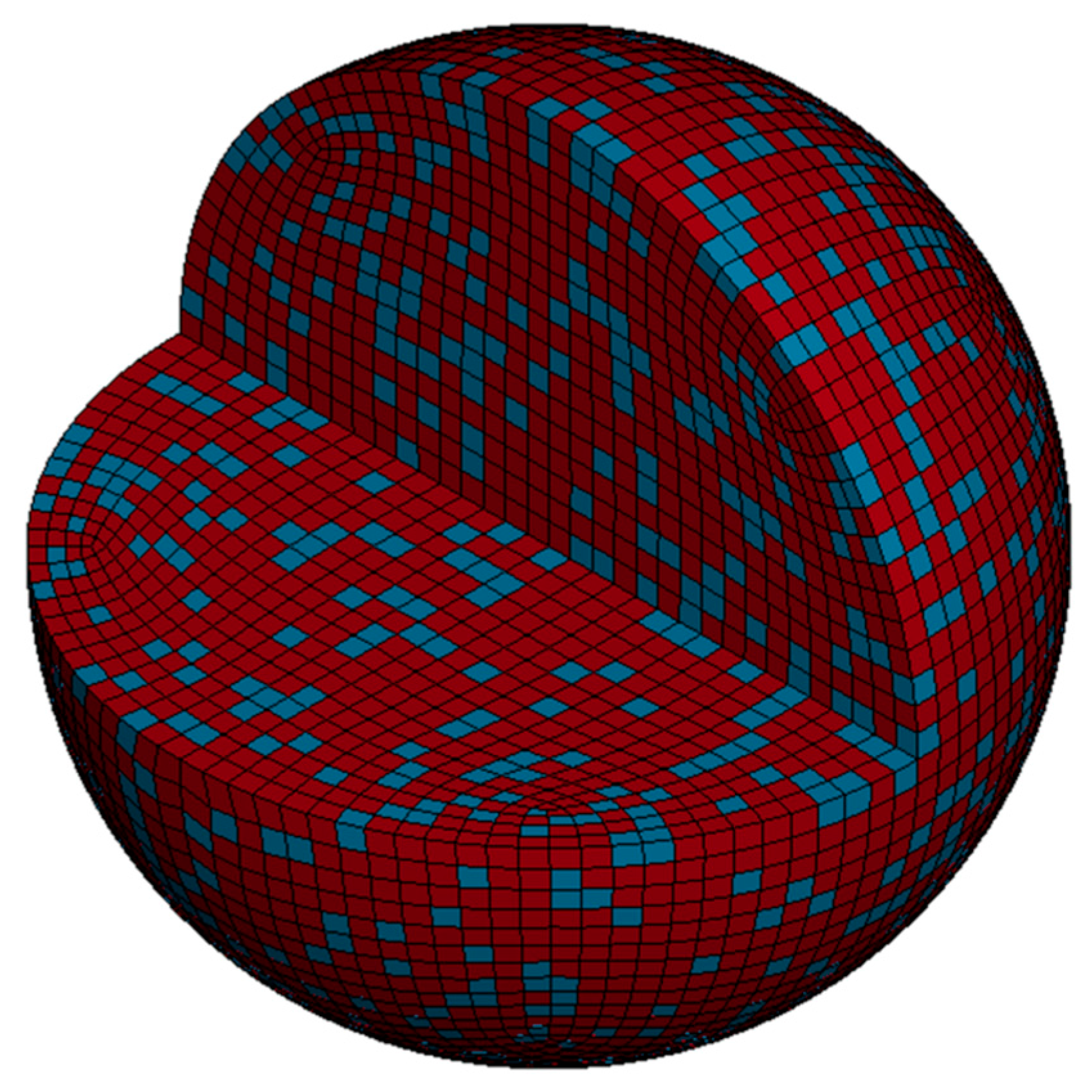

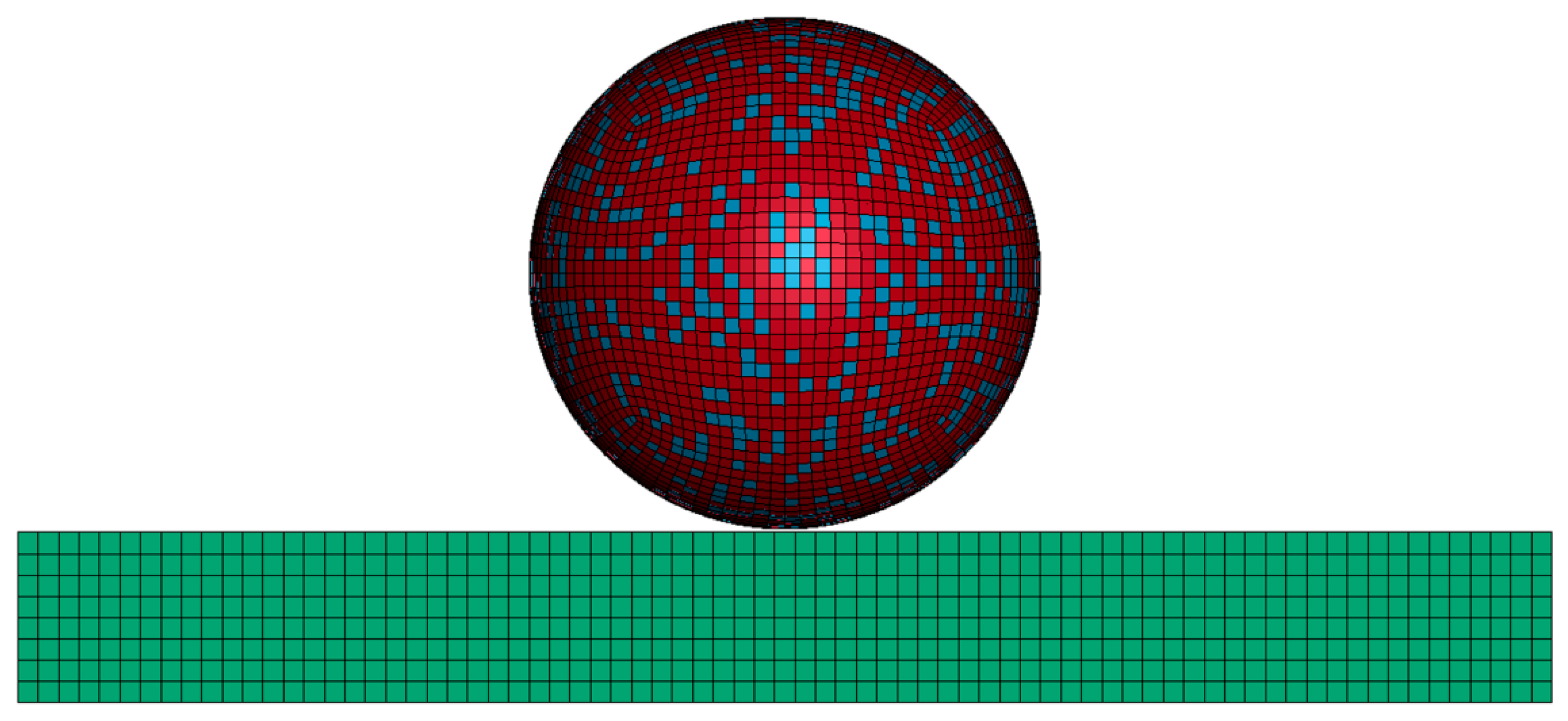

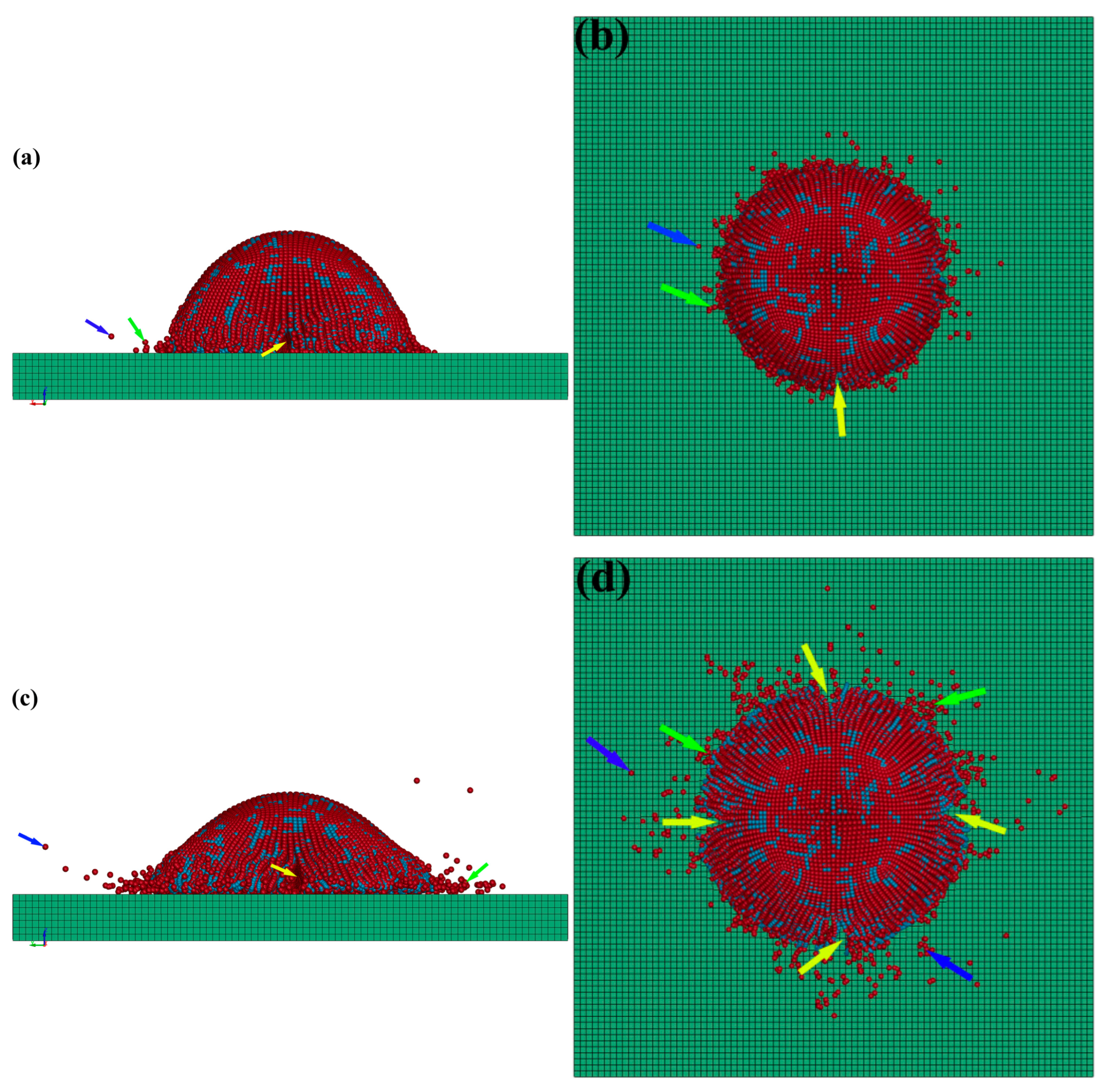

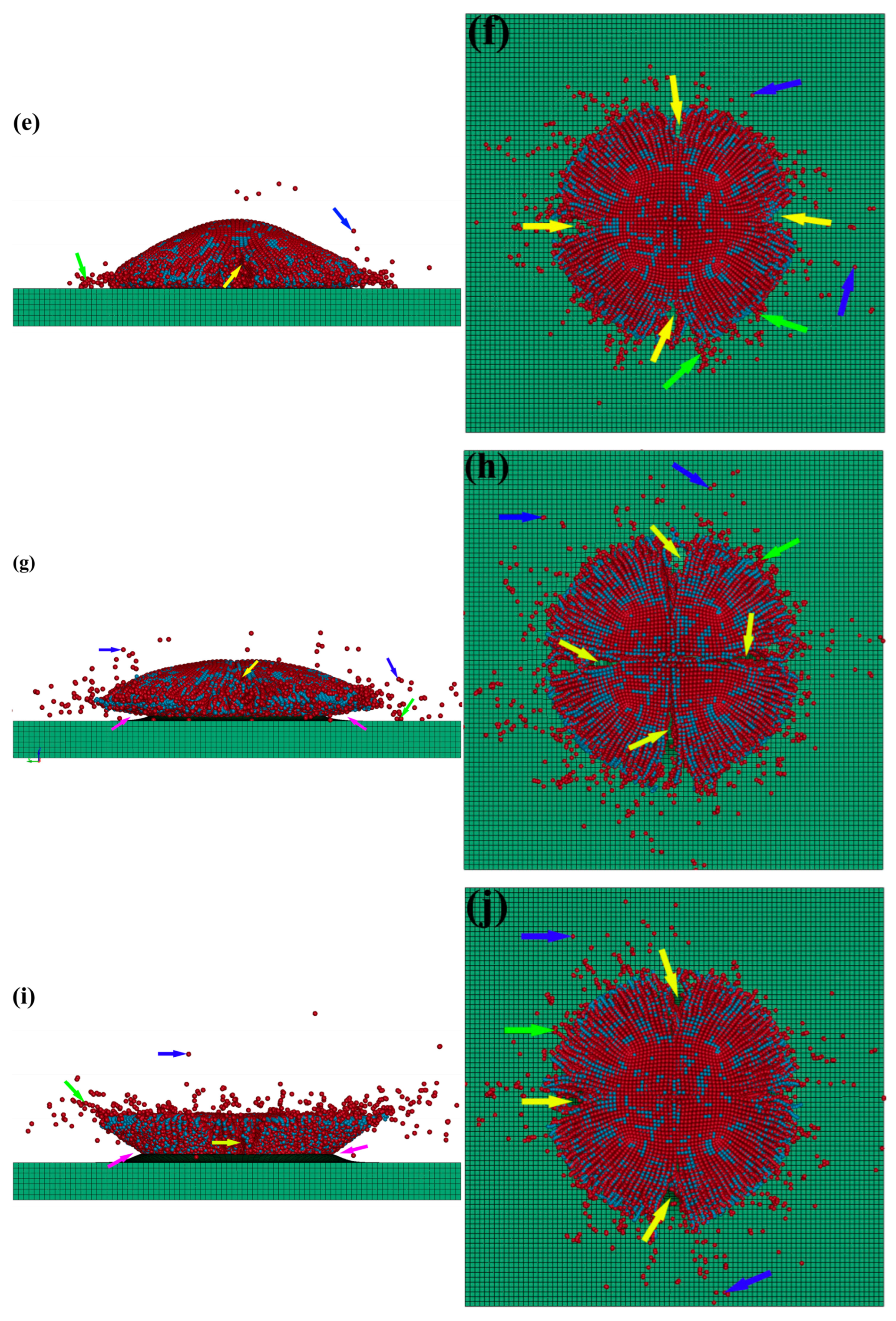

3.1. Numerical Simulation of Deposition Behavior for Individual Composite Particles at Varying Particle Velocities

3.2. Deposition Behavior Analysis of Cold-Sprayed Single nHA/Ti Composite Particle

3.3. Deposition Behavior Analysis of Cold-Sprayed Multiple nHA/Ti Composite Particles

3.4. Microstructure of Cold-Sprayed nHA/Ti Composite Coatings

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tian, Y.S.; Qian, X.L.; Chen, M.Q. Effect of saturated steam treatment on the crystallinity of plasma-sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2015, 266, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.G.; Yang, Z.R.; Cheng, J. Preparation, characterization and antibacterial properties of cerium substituted hydroxyapatite nanoparticle. J. Rare Earth 2007, 25, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.L.; Zou, Y.L.; Bai, X.B.; Wang, H.T.; Ji, G.C.; Chen, Q.Y. Microstructures, mechanical properties and electrochemical behaviors of nano-structured HA/Ti composite coatings deposited by high-velocity suspension flame spray (HVSFS). Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 13024–13030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.L.; Wang, H.T.; Bai, X.B.; Ji, G.C.; Chen, Q.Y. Improvement in mechanical properties of nano-structured HA/TiO2 multilayer coatings deposited by high velocity suspension flame spraying (HVSFS). Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 342, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, W.S.M.; Asri, R.I.M.; Alias, J.; Zulkifli, F.H.; Kadirgama, K.; Ghani, S.A.C.; Shariffuddin, J.H.M. A comprehensive review of hydroxyapatite-based coatings adhesion on metallic biomaterials. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 1250–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, C.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Lu, W.W.; Lam, R.W.M.; Chen, X.F.; Chiu, K.Y.; Ye, J.D.; Wu, G.; Wu, Z.H. Nano-structural bioactive gradient coating fabricated by computer controlled plasma-spraying technology. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2006, 17, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xiao, G.Y.; Chen, C.Z.; Lu, Y.P. Nanostructured hydroxyapatite coating obtained from scholzite with improved corrosion resistance. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 6928–6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordi, G.M.; Núria, C.; Miquel, P.; Cano, I.G.; Gil, F.J.; Guilemany, J.M.; Dosta, S. Porous titanium-hydroxyapatite composite coating obtained on titanium by cold gas spray with high bond strength for biomedical applications. Colloids Surf. B 2019, 180, 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.J. Properties and immersion behavior of magnetron-sputtered multi-layered hydroxyapatite/titanium composite coatings. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4233–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.N.D.; Nguyen, V.B.; Phuong, P.T.M.D.; Pham, S.H.; Tran, V.D.D.; Pham, A.T.; Pham, V.H.; Nguyen, T.T.H.; Nguyen, T.L.D.; Pham, V.H. Preparation and properties of Hydroxyapatite-Ti composite thin films by co-sputtering method for biocompatibility applications. Mater. Res. Express 2024, 11, 085404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morteza, F. Electrophoretic deposition of fiber hydroxyapatite/titania nanocomposite coatings. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 622–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.X.; Pei, X.B.; Yang, S.Y.; Qin, H.; Cai, H.; Hu, S.S.; Sui, L.; Wan, Q.B.; Wang, J. Graphene oxide/hydroxyapatite composite coatings fabricated by electrochemical deposition. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 286, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Raza, M.S.; Datta, S.; Saha, P. Synthesis and characterization of nickel free titanium–hydroxyapatite composite coating over Nitinol surface through in-situ laser cladding and alloying. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 358, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.B.; Wang, J.; Wan, Q.B.; Kang, L.; Xiao, M.; Hong, B. Functionally graded carbon nanotubes/hydroxyapatite composite coating by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2011, 205, 4380–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, R.R.; Hasan, A.; Sankar, M.R.; Pandey, L.M. Laser cladding with HA and functionally graded TiO2-HA precursors on Ti-6Al-4V alloy for enhancing bioactivity and cyto-compatibility. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 352, 420–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Singh, G.; Chawla, V. Characterization and mechanical behaviour of reinforced hydroxyapatite coatings deposited by vacuum plasma spray on SS-316L alloy. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2018, 79, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Khor, K.A.; Cheang, P. Effect of the powders’melting state on the properties of HVOF sprayed hydroxyapatite coatings. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2000, 293, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, G.C.; Zou, Y.L.; Chen, Q.Y.; Yao, H.L.; Bai, X.B.; Yang, C.; Wang, H.T.; Wang, F. Mechanical properties of warm sprayed HATi bio-ceramic composite coatings. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 27021–27030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.Y.; Zhang, B.T.; Gong, Y.F.; Zhou, P.; Li, H. Mechanical properties of nanodiamond-reinforced hydroxyapatite composite coatings deposited by suspension plasma spraying. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 439, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.Y.; Jiang, R.R.; Huang, C.J.; Zhang, Z.H.; Feng, Y. Effect of cold sprayed Al coating on mechanical property and corrosion behavior of friction stir welded AA2024-T351 joint. Mater. Design 2015, 65, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suo, X.K.; Yu, M.; Li, W.Y.; Planche, M.P.; Liao, H.L. Effect of substrate preheating on bonding strength of cold-sprayed Mg coatings. J. Therm. Spray Technol. 2012, 21, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Xie, X.L.; Xie, Y.C.; Yan, X.C.; Huang, C.J.; Deng, S.H.; Ren, Z.M.; Liao, H.L. Metallization of polyether ether ketone (PEEK) by copper coating via cold spray. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 342, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.J.; Li, W.Y. Deposition characteristics of titanium coating in cold spraying. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 167, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Voisey, K.T.; Hussain, T. High temperature chlorine-induced corrosion of Ni50Cr coating: HVOLF, HVOGF, cold spray and laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 337, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.J.; Li, C.J.; Liao, K.X.; He, X.L.; Li, S.; Fan, S.Q. Influence of gas flow during vacuum cold spraying of nano-porous TiO2 film by using strengthened nanostructured powder on performance of dye-sensitized solar cell. Thin Solid Films 2011, 519, 4709–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, H.T.; Ji, G.C.; Bai, X.B.; Deng, Z.X. Deposition behavior of nanostructured WC-23Co particles in cold spraying process. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2016, 31, 1507–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.H.; Li, C.J.; Yang, G.J.; Li, Y.G.; Li, C.X. Influence of substrate hardness on deposition behavior of single porous WC-12Co particle in cold spraying. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2008, 203, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, F.S.; Cinca, N.; Dosta, S.; Cano, I.G.; Couto, M.; Guilemany, J.M.; Benedetti, A.V. Corrosion behavior of WC-Co coatings deposited by cold gas spray onto AA 7075-T6. Corros. Sci. 2018, 136, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, C.H.; Hwang, S.Y. Superhard nano WC-12%Co coating by cold spray deposition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 391, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ji, G.C.; Bai, X.B.; Yao, H.L.; Chen, Q.Y.; Zou, Y.L. Microstructures and properties of cold spray nanostructured HA coatings. J. Therm. Spray. Technol. 2018, 27, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.Y.; Zou, Y.L.; Chen, X.; Bai, X.B.; Ji, G.C.; Yao, H.L.; Wang, H.T.; Wang, F. Morphological, structural and mechanical characterization of cold sprayed hydroxyapatite coating. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2019, 357, 910–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilardell, A.M.; Cinca, N.; Garcia-Giralt, N.; Dosta, S.; Cano, I.G.; Nogués, X.; Guilemany, J.M. Functionalized coatings by cold spray: An in vitro study of micro- and nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite compared to porous titanium. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2018, 87, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajdelsztajn, L.; Schoenung, J.M.; Jodoin, B.; Kim, G.E. Cold spray deposition of nanocrystalline aluminum alloys. Met. Mat. Trans. A 2005, 36, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judd, K.G.; Sharma, M.M.; Eden, T.J. Multifunctional bioceramic composite coatings deposited by cold spray. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 813, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Chen, X.; Wu, Z.C.; Li, C.D.; Deng, X.F. Numerical simulation and experimental study of deposition behavior for cold sprayed dual nano HA/30 wt.% Ti composite particle. Coatings 2024, 14, 1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Accelerating nitrogen gas pressure | MPa | 2.0 |

| Powder-feeding nitrogen gas pressure | MPa | 2.2 |

| Gas temperature for individual nHA/Ti splats | °C | 300 ± 10, 500 ± 10, 700 ± 10 |

| Gas temperature for nHA/Ti coating | °C | 500 ± 30, 700 ± 30 |

| Gas temperature for Ti buffer layer | °C | 200 ± 30 |

| Transverse speed for individual nHA/Ti splats | mm/s | 500 |

| Transverse speed for nHA/Ti coating | mm/s | 30 |

| Transverse speed for Ti buffer layer | mm/s | 150 |

| Spray distance | mm | 20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Li, C.; Zhu, S.; Ao, P.; Hu, Y. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study of Deposition Behavior for Cold-Sprayed Nano-Structured HA/70wt.%Ti Composite Coating. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231807

Chen X, Li C, Zhu S, Ao P, Hu Y. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study of Deposition Behavior for Cold-Sprayed Nano-Structured HA/70wt.%Ti Composite Coating. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231807

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiao, Chengdi Li, Shuangxia Zhu, Peiyun Ao, and Yao Hu. 2025. "Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study of Deposition Behavior for Cold-Sprayed Nano-Structured HA/70wt.%Ti Composite Coating" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231807

APA StyleChen, X., Li, C., Zhu, S., Ao, P., & Hu, Y. (2025). Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study of Deposition Behavior for Cold-Sprayed Nano-Structured HA/70wt.%Ti Composite Coating. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231807