Direct Synthesis of Single-Crystalline Bilayer Graphene on Dielectric Substrate

Abstract

1. Introduction

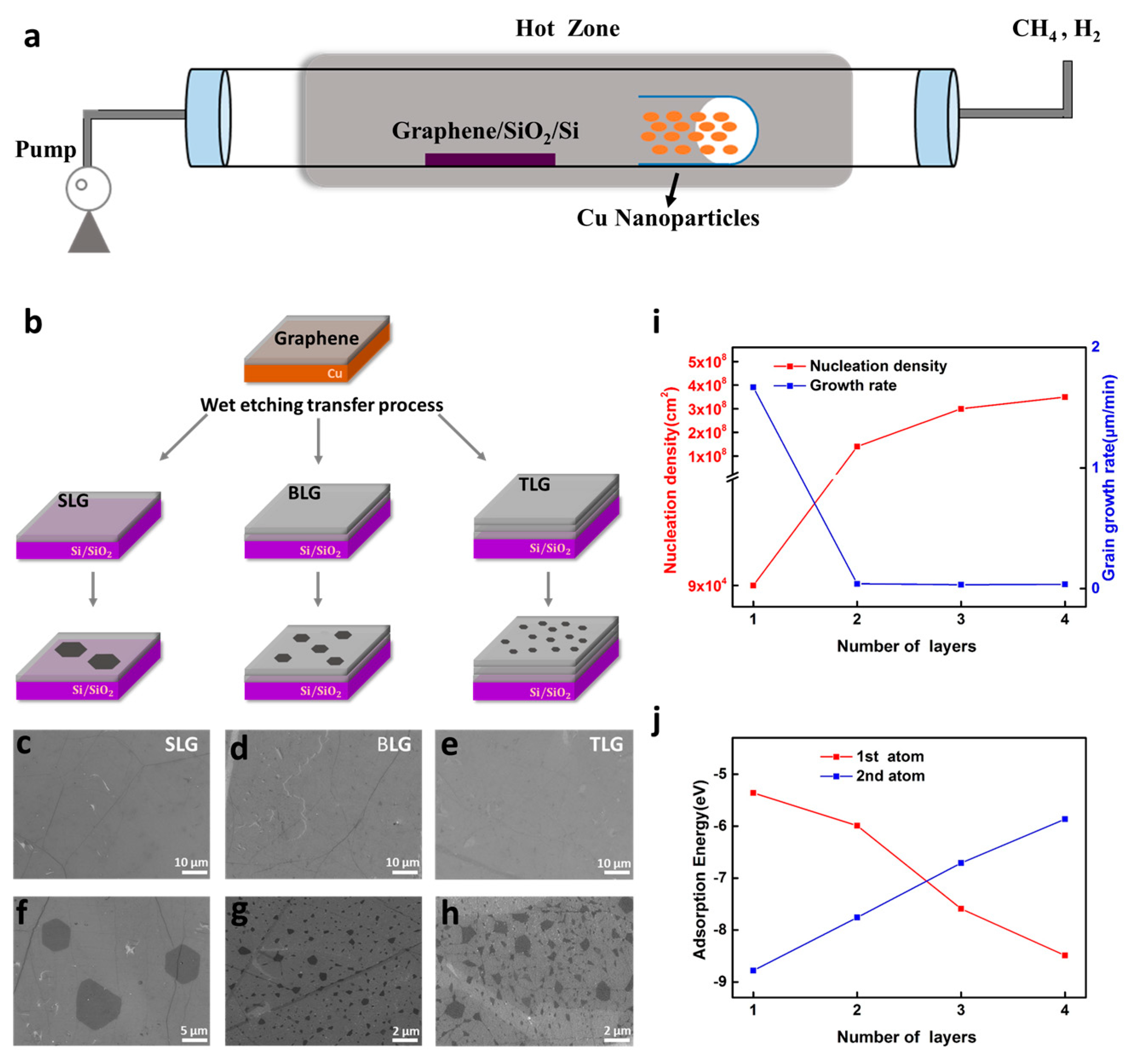

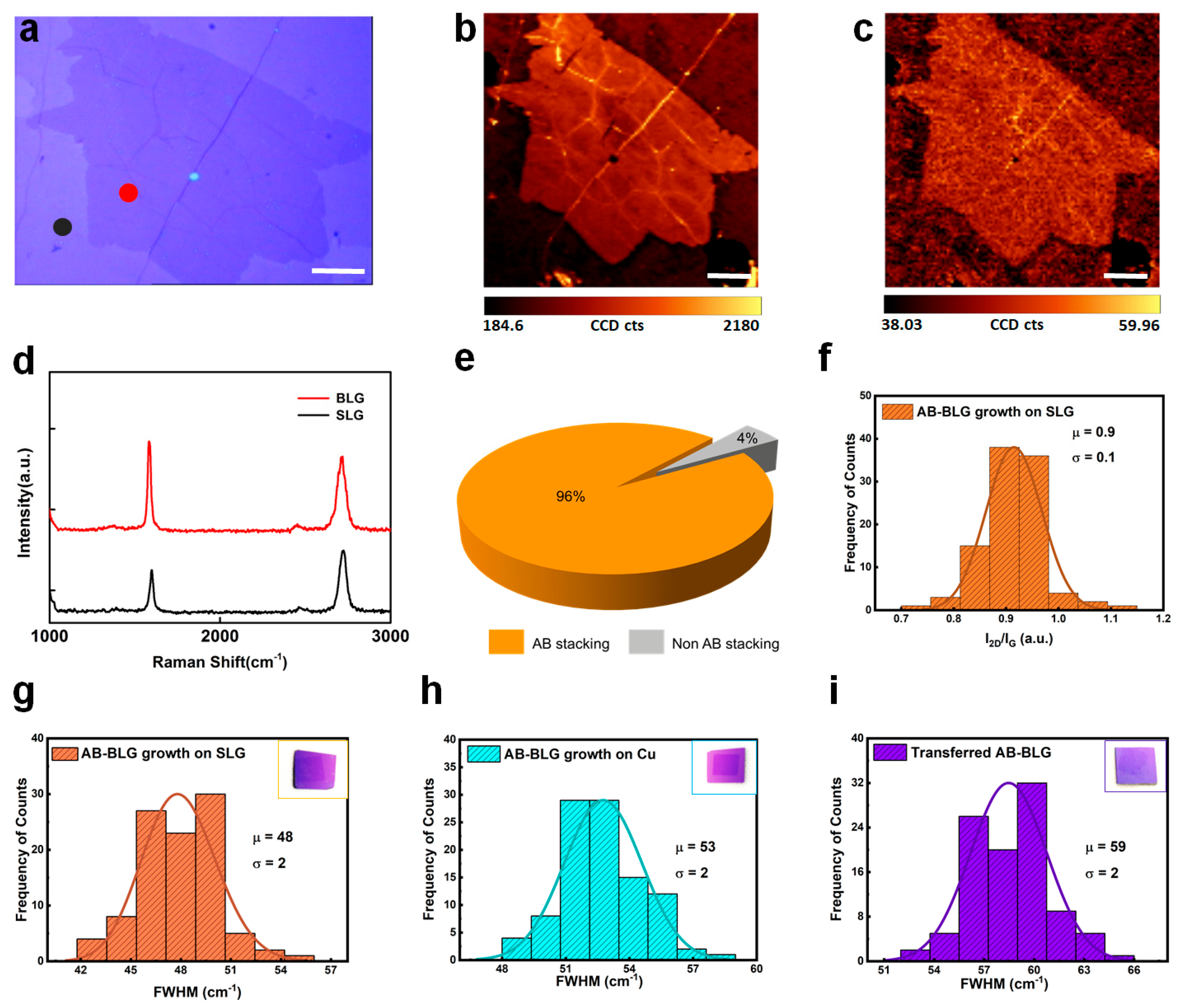

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Preparation of Single-Crystalline SLG Template

2.2. Synthesis of Single-Crystalline BLG

2.3. Characterizations

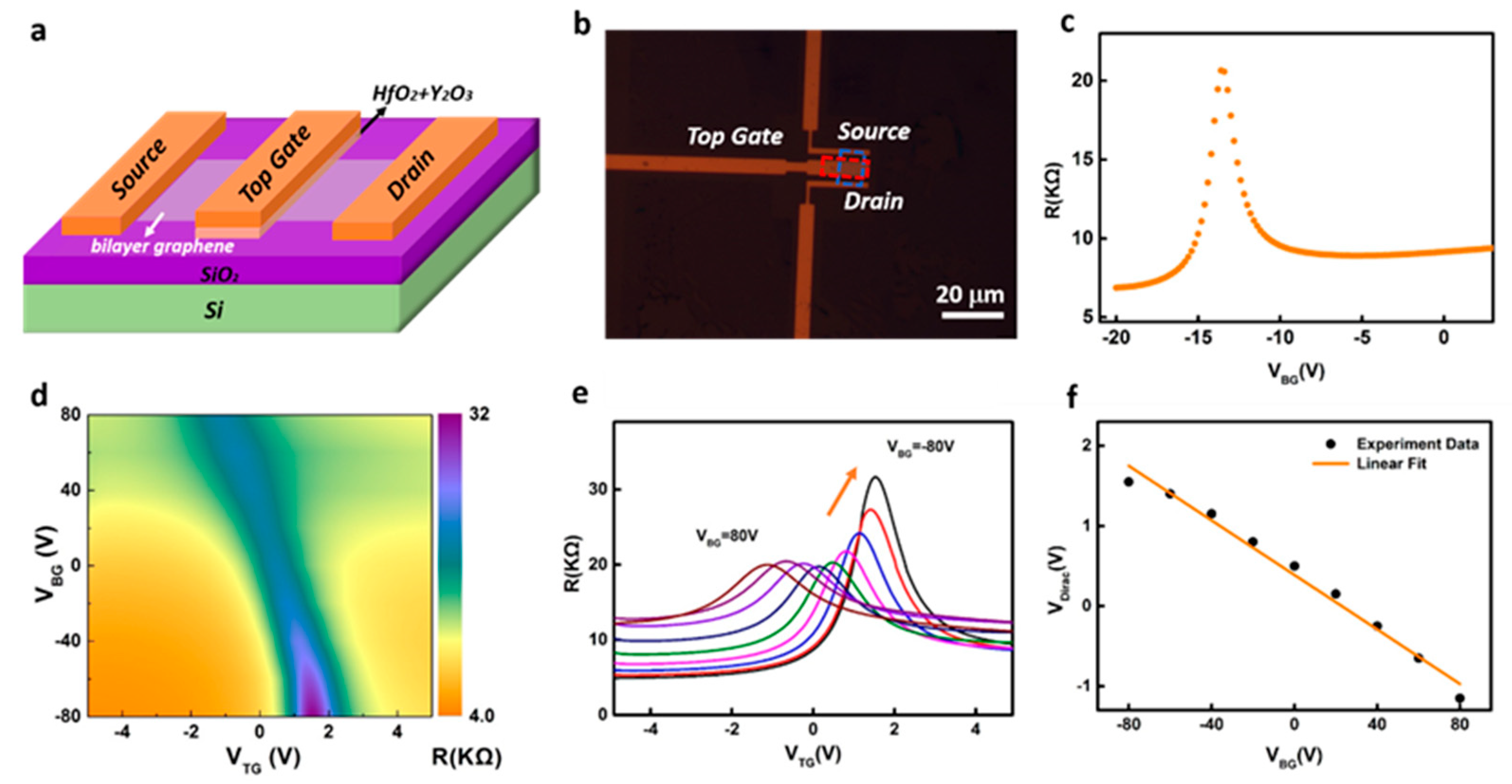

2.4. Device Fabrication and Electrical Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, K.; Fu, H.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Zhu, J. High-temperature quantum valley Hall effect with quantized resistance and a topological switch. Science 2024, 385, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Polski, R.; Thomson, A.; Lantagne-Hurtubise, E.; Lewandowski, C.; Zhou, H.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Alicea, J.; Nadj-Perge, S. Enhanced superconductivity in spin-orbit proximitized bilayer graphene. Nature 2023, 613, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorashi, S.A.A.; Dunbrack, A.; Abouelkomsan, A.; Sun, J.; Du, X.; Cano, J. Topological and Stacked Flat Bands in Bilayer Graphene with a Superlattice Potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2023, 130, 196201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, G.Q.; Jing, F.M.; Hao, T.Y.; Jiang, S.L.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Cao, G.; Song, X.X.; Guo, G.P. Switching Spin Filling Sequence in a Bilayer Graphene Quantum Dot through Trigonal Warping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2025, 134, 036301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denisov, A.O.; Reckova, V.; Cances, S.; Ruckriegel, M.J.; Masseroni, M.; Adam, C.; Tong, C.; Gerber, J.D.; Huang, W.W.; Watanabe, K.; et al. Spin–valley protected Kramers pair in bilayer graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2025, 20, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.; Ginzel, F.; Kurzmann, A.; Garreis, R.; Ostertag, L.; Gerber, J.D.; Huang, W.W.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Burkard, G.; et al. Three-Carrier Spin Blockade and Coupling in Bilayer Graphene Double Quantum Dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppens, F.H.; Mueller, T.; Avouris, P.; Ferrari, A.C.; Vitiello, M.S.; Polini, M. Photodetectors based on graphene, other two-dimensional materials and hybrid systems. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 780–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccorso, F.; Sun, Z.; Hasan, T.; Ferrari, A.C. Graphene photonics and optoelectronics. Nat. Photonics 2010, 4, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, R.; Ta, H.Q.; Sun, J.; Wang, W.; Zhu, W.; Fang, T.; Jia, K.; et al. Fast synthesis of large-area bilayer graphene film on Cu. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Kim, S.; Chen, X.; Einarsson, E.; Wang, M.; Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Chiashi, S.; Xiang, R.; Maruyama, S. Equilibrium chemical vapor deposition growth of Bernal-stacked bilayer graphene. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 11631–11638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, R.; Yu, W.J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Shaw, J.; Zhong, X.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. High-Yield Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth of High-Quality Large-Area AB-Stacked Bilayer Graphene. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 8241–8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Pan, J.; Tan, Z.; Li, Y.; Cui, Y. In Situ Growth Dynamics of Uniform Bilayer Graphene with Different Twisted Angles Following Layer-by-Layer Mode. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2022, 13, 11201–11207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Bakharev, P.V.; Wang, Z.-J.; Biswal, M.; Yang, Z.; Jin, S.; Wang, B.; Park, H.J.; Li, Y.; Qu, D.; et al. Large-area single-crystal AB-bilayer and ABA-trilayer graphene grown on a Cu/Ni(111) foil. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Naylor, C.H.; Kim, Y.; Abidi, I.H.; Ping, J.; Ducos, P.; Zauberman, J.; Zhao, M.-Q.; Rappe, A.M.; et al. Crystalline Bilayer Graphene with Preferential Stacking from Ni-Cu Gradient Alloy. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 2275–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Kraemer, S.; Sarkar, D.; Li, H.; Ajayan, P.M.; Banerjee, K. Controllable and Rapid Synthesis of High-Quality and Large-Area Bernal Stacked Bilayer Graphene Using Chemical Vapor Deposition. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, C.; Hajnal, Z.; Deák, P.; Frauenheim, T.; Suhai, S. Theoretical investigation of carbon defects and diffusion in α-quartz. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 085333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Teixeira, C.B.; Sun, L.; Morais, P.C. Magnetic nanoparticle film reconstruction modulated by immersion within DMSA aqueous solution. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanton, M.A.; Robinson, J.A.; Puls, C.; Liu, Y.; Hollander, M.J.; Weiland, B.E.; LaBella, M.; Trumbull, K.; Kasarda, R.; Howsare, C.; et al. Characterization of Graphene Films and Transistors Grown on Sapphire by Metal-Free Chemical Vapor Deposition. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 8062–8069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, Y.; Jiang, L.; Xu, Z.; Huang, L.; Xue, Y.; Geng, D.; Wu, B.; Hu, W.; Yu, G.; et al. Near-equilibrium chemical vapor deposition of high-quality single-crystal graphene directly on various dielectric substrates. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 1348–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xue, X.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Geng, D.; Cai, L.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z.; Yu, G. Primary Nucleation-Dominated Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth for Uniform Graphene Monolayers on Dielectric Substrate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 11004–11008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, Y.; Xu, X.; Park, J.S.; Zheng, Y.; Balakrishnan, J.; Lei, T.; Kim, H.R.; Song, Y.I.; et al. Roll-to-roll production of 30-inch graphene films for transparent electrodes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010, 5, 574–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yuan, Y.; Lanza, M.; Abate, I.; Tian, B.; Zhang, X. Nonepitaxial Wafer-Scale Single-Crystal 2D Materials on Insulators. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2310921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, F.; Deng, J.; Dong, Y.; Xu, C.; Hu, L.; Fu, G.; Chang, P.; Xie, Y.; Sun, J. Transfer-Free CVD Growth of High-Quality Wafer-Scale Graphene at 300 degrees °C for Device Mass Fabrication. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 53174–53182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Villanueva, S.; Mendoza, F.; Instan, A.A.; Katiyar, R.S.; Weiner, B.R.; Morell, G. Graphene Growth Directly on SiO2/Si by Hot Filament Chemical Vapor Deposition. Nanomaterials 2021, 12, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Song, I.; Park, C.; Son, M.; Hong, M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.S.; Shin, H.-J.; Baik, J.; Choi, H.C. Copper-Vapor-Assisted Chemical Vapor Deposition for High-Quality and Metal-Free Single-Layer Graphene on Amorphous SiO2 Substrate. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 6575–6582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, P.-Y.; Lu, C.-C.; Akiyama-Hasegawa, K.; Lin, Y.-C.; Yeh, C.-H.; Suenaga, K.; Chiu, P.-W. Remote Catalyzation for Direct Formation of Graphene Layers on Oxides. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, J.; Chu, J.H.; Choi, J.-K.; Park, S.-D.; Go, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Park, K.; Kim, S.-D.; Kim, Y.-W.; Yoon, E.; et al. Near room-temperature synthesis of transfer-free graphene films. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, S.; Ma, L.-P.; Chen, M.-L.; Liu, Z.; Ma, W.; Sun, D.-M.; Cheng, H.-M.; Ren, W. Water-assisted rapid growth of monolayer graphene films on SiO2/Si substrates. Carbon 2019, 148, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, N.; Zhang, R.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Yu, J.; Xu, X.; Jiang, H.; Li, X. Direct growth of graphene film on the silicon substrate with a nickel-ring remote catalyzation. Vacuum 2025, 238, 114275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, J.S.; Singh, A.; Agarwal, P. Work function tuning of directly grown multi-layer graphene on silicon by PECVD and fabrication of Ag/ITO/Gr/n-Si/Ag solar cell. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 155, 112271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Peng, Z.; Sun, Z.; Yao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Ajayan, P.M.; Tour, J.M. Growth of Bilayer Graphene on Insulating Substrates. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 8187–8192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, R.; López-Elvira, E.; Munuera, C.; Carrascoso, F.; Xie, Y.; Çakıroğlu, O.; Pucher, T.; Puebla, S.; Castellanos-Gomez, A.; García-Hernández, M. Low T direct plasma assisted growth of graphene on sapphire and its integration in graphene/MoS2 heterostructure-based photodetectors. Npj 2D Mater. Appl. 2023, 7, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, M.; Samad, A.; Dong, H.; Ray, A.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, X.; Schwingenschlogl, U.; Domke, J.; Chen, C.; et al. Wafer-scale single-crystal monolayer graphene grown on sapphire substrate. Nat. Mater. 2022, 21, 740–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Xie, C.; Wang, W.; Zhao, J.; Liu, B.; Shan, J.; Wang, X.; Hong, M.; Lin, L.; Huang, L.; et al. Direct growth of wafer-scale highly oriented graphene on sapphire. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabk0115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismach, A.; Druzgalski, C.; Penwell, S.; Schwartzberg, A.; Zheng, M.; Javey, A.; Bokor, J.; Zhang, Y. Direct Chemical Vapor Deposition of Graphene on Dielectric Surfaces. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 1542–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Zeng, M.; Wu, Q.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Zhang, T.; Eckert, J.; Rümmeli, M.H.; Fu, L. Direct Growth of Ultrafast Transparent Single-Layer Graphene Defoggers. Small 2015, 11, 1840–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Sun, Z.; Cui, K.; Xue, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, W.; Gu, W.; Zheng, K.; Liu, R.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Self-Aided Batch Growth of 12-Inch Transfer-Free Graphene Under Free Molecular Flow. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 33, 2210771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Peng, Z.; Sun, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Ci, H.; Liu, B.; Cheng, Y.; Jiang, B.; Hu, J.; et al. CO2-promoted transfer-free growth of conformal graphene. Nano Res. 2022, 16, 6334–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wang, H.; Gu, W.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Z.; Nie, Y.; Tan, C.; Ci, H.; Wei, N.; Cui, L.; et al. Oxygen-assisted direct growth of large-domain and high-quality graphene on glass targeting advanced optical filter applications. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 260–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.S.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, X.; Cong, C.; Xie, H.; Liu, X.; Zhou, X.; Huang, F.; et al. Silane-catalysed fast growth of large single-crystalline graphene on hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Chen, G.; Shi, Z.; Liu, C.C.; Zhang, L.; Xie, G.; Cheng, M.; Wang, D.; Yang, R.; Shi, D.; et al. Epitaxial growth of single-domain graphene on hexagonal boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 792–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Meyer, J.C.; Scardaci, V.; Casiraghi, C.; Lazzeri, M.; Mauri, F.; Piscanec, S.; Jiang, D.; Novoselov, K.S.; Roth, S.; et al. Raman spectrum of graphene and graphene layers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 187401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cançado, L.G.; Jorio, A.; Ferreira, E.H.M.; Stavale, F.; Achete, C.A.; Capaz, R.B.; Moutinho, M.V.O.; Lombardo, A.; Kulmala, T.S.; Ferrari, A.C. Quantifying Defects in Graphene via Raman Spectroscopy at Different Excitation Energies. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3190–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Peng, H.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, Z. Formation of bilayer bernal graphene: Layer-by-layer epitaxy via chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 1106–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Magnuson, C.W.; Venugopal, A.; Tromp, R.M.; Hannon, J.B.; Vogel, E.M.; Colombo, L.; Ruoff, R.S. Large-area graphene single crystals grown by low-pressure chemical vapor deposition of methane on copper. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 2816–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Ji, H.; Chou, H.; Li, Q.; Li, H.; Suk, J.W.; Piner, R.; Liao, L.; Cai, W.; Ruoff, R.S. Millimeter-Size Single-Crystal Graphene by Suppressing Evaporative Loss of Cu During Low Pressure Chemical Vapor Deposition. Adv. Mater. 2013, 25, 2062–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, W.; Wang, L.; Chen, S. Layer-by-layer synthesis of bilayer and multilayer graphene on Cu foil utilizing the catalytic activity of cobalt nano-powders. Carbon 2019, 146, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Robertson, J. Interpretation of Raman spectra of disordered and amorphous carbon. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 14095–14107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon, F.H.; Coaquira, J.A.; Villegas-Lelovsky, L.; da Silva, S.W.; Cesar, D.F.; Nagamine, L.C.; Cohen, R.; Menendez-Proupin, E.; Morais, P.C. Evolution of the doping regimes in the Al-doped SnO2 nanoparticles prepared by a polymer precursor method. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2015, 27, 095301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.C.; Basko, D.M. Raman spectroscopy as a versatile tool for studying the properties of graphene. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2013, 8, 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.C.; Geim, A.K.; Katsnelson, M.I.; Novoselov, K.S.; Booth, T.J.; Roth, S. The structure of suspended graphene sheets. Nature 2007, 446, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.H.; Rummeli, M.H.; Bachmatiuk, A.; Buchner, B. Atomic resolution imaging and topography of boron nitride sheets produced by chemical exfoliation. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 1299–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Lee, K.; Zhong, Z. Wafer scale homogeneous bilayer graphene films by chemical vapor deposition. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 4702–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Perebeinos, V.; Lin, Y.M.; Wu, Y.; Avouris, P. The origins and limits of metal-graphene junction resistance. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taychatanapat, T.; Jarillo-Herrero, P. Electronic transport in dual-gated bilayer graphene at large displacement fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 166601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Nah, J.; Jo, I.; Shahrjerdi, D.; Colombo, L.; Yao, Z.; Tutuc, E.; Banerjee, S.K. Realization of a high mobility dual-gated graphene field-effect transistor with Al2O3 dielectric. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 062107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Peng, L.M. Top-gated graphene field-effect transistors with high normalized transconductance and designable dirac point voltage. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 5031–5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Ding, L.; Zeng, Q.; Yang, L.; Pei, T.; Liang, X.; Gao, M.; et al. Growth and performance of yttrium oxide as an ideal high-kappa gate dielectric for carbon-based electronics. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2024–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.J.; Liao, L.; Chae, S.H.; Lee, Y.H.; Duan, X. Toward tunable band gap and tunable dirac point in bilayer graphene with molecular doping. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 4759–4763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, T.-T.; Girit, C.; Hao, Z.; Martin, M.C.; Zettl, A.; Crommie, M.F.; Shen, Y.R.; Wang, F. Direct observation of a widely tunable bandgap in bilayer graphene. Nature 2009, 459, 820–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, Z.; Xing, X.; Fang, Y.; Huang, L.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, S. Direct Synthesis of Single-Crystalline Bilayer Graphene on Dielectric Substrate. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15211629

Tan Z, Xing X, Fang Y, Huang L, Wu S, Zhang Z, Wang L, Chen X, Chen S. Direct Synthesis of Single-Crystalline Bilayer Graphene on Dielectric Substrate. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(21):1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15211629

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Zuoquan, Xianqin Xing, Yimei Fang, Le Huang, Shunqing Wu, Zhiyong Zhang, Le Wang, Xiangping Chen, and Shanshan Chen. 2025. "Direct Synthesis of Single-Crystalline Bilayer Graphene on Dielectric Substrate" Nanomaterials 15, no. 21: 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15211629

APA StyleTan, Z., Xing, X., Fang, Y., Huang, L., Wu, S., Zhang, Z., Wang, L., Chen, X., & Chen, S. (2025). Direct Synthesis of Single-Crystalline Bilayer Graphene on Dielectric Substrate. Nanomaterials, 15(21), 1629. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15211629