Mindfulness practice, defined as paying attention to the present moment without feelings of judgement or overwhelm (

Kabat-Zinn 1982), has received growing interest because of the potentially advantageous outcomes that mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) afford for everyday tasks. More specifically, many researchers have argued that mindfulness practice exerts beneficial effects on different aspects of attention, including sustained attention, inhibitory control, and cognitive flexibility (for a recent review, see

Verhaeghen 2021). These claimed benefits are perhaps unsurprising given that attentional mechanisms are proposed to be core to engaging in mindfulness practice and necessary to improve non-judgemental awareness, overall self-regulation, and positive behavioural outcomes (

Lindsay and Creswell 2017;

Tang et al. 2015). Although the terminology involved in models of mindfulness has differed over the past decade (e.g., encompassing notions such as awareness, cognitive flexibility, emotional regulation and acceptance), it is nevertheless the case that the concept of attention continues to be pivotal for understanding the mechanisms that are engaged by mindfulness practice. As such, it seems important to examine further the role that attention plays in influencing how mindfulness impacts cognition, and to extend these investigations to advancing an understanding of the benefit of mindfulness for important real-world activities such as creative cognition. The research reported in the present paper aimed to address these issues, with a specific focus on the potentially positive impact of brief mindfulness practice on sustained attention, attentional inhibition and creative performance, as well as the mediating role played by attentional mechanisms for creativity outcomes.

It is noteworthy that in the literature, attentional mechanisms such as executive functioning are proposed to be highly associated with creative thinking processes (

Sharma and Babu 2017). Creative thinking is often conceptualised as comprising two core components: (i) divergent thinking, the ability to generate multiple novel ideas or solutions; and (ii) convergent thinking, the ability to identify a single, appropriate solution to a problem (

Guilford 1967;

Runco and Acar 2012). These components are not equivalent to creativity itself but are widely accepted as being key indices or cognitive markers of the creative process. Divergent thinking is often assessed through tasks that measure the fluency, flexibility, and originality of idea generation (e.g., the Alternative Uses Task, where participants are asked to come up with novel uses for a common, everyday object), while convergent thinking is typically assessed through tasks requiring insight and precision, such as the Compound Remote Associates Test or rebus puzzles, which have also been argued to tap into insight-based problem solving (

Lee and Therriault 2013;

Salvi et al. 2016).

Recent research has started to disentangle how mindfulness might influence these distinct components of creative thinking. For example, mindfulness has been associated with enhanced divergent thinking via mechanisms such as increased openness to experience and emotional regulation.

Giancola et al. (

2024) demonstrated that both cognitive reappraisal and dispositional mindfulness mediated the positive relationship between openness and divergent thinking, highlighting the affective and attentional pathways through which mindfulness may support idea generation. However, other studies have pointed to possible benefits of mindfulness for convergent thinking, particularly through improved executive attention and cognitive control (e.g.,

Ostafin and Kassman 2012;

Zedelius and Schooler 2016).

The seemingly central role of attention in both mindfulness practice and creative cognition raises an important question as to whether mindfulness can facilitate convergent or divergent thinking through attentional enhancement. Although some meta-analytical reviews (e.g.,

Lebuda et al. 2016) support a general positive association between mindfulness and creative thinking, the field still lacks consensus on the generalisability and underlying mechanisms of these effects. Indeed, a more recent meta-analysis by

Hughes et al. (

2023), which presents an extensive and systematic review of the relationship between mindfulness and creative thinking, demonstrates stronger and more consistent positive effects of mindfulness on convergent thinking than on divergent thinking. This supports the notion that attentional mechanisms enhanced by mindfulness may be more directly involved in convergent rather than divergent thinking tasks, with the former typically requiring greater cognitive control and goal-directed attention (

Hughes et al. 2023).

Given this emerging pattern of evidence, the present study focuses specifically on convergent thinking as a key outcome of mindfulness practice. In doing so, we adopt the position that convergent thinking is one measurable index of creative cognition, and that it may benefit from the attentional enhancements provided by mindfulness. The current experiment therefore investigates whether the attentional pathways associated with mindfulness (e.g., sustained attention and attentional inhibition) can contribute to enhanced convergent thinking performance, and whether these attentional mechanisms mediate this effect.

1.1. Mindfulness and Attention

Mindfulness has been associated with improved performance on tasks that measure attention, regardless of the length of practice (e.g.,

Mak et al. 2018;

Verhaeghen 2021). However, the picture is complicated because of the range of attention-related tasks that have been utilised across studies. One attention-related construct that has been subjected to particularly close scrutiny in the mindfulness literature is that of sustained attention (e.g.,

Verhaeghen 2021;

Wimmer et al. 2020), which is the ability to focus on an activity or stimulus over a long period of time (

Oken et al. 2006). Extensive findings are consistent with the view that mindfulness can serve as an effective tool to improve people’s ability to sustain attention (

Schuman-Olivier et al. 2020), as evidenced by people’s higher accuracy and faster reaction times following mindfulness practice on classic tasks such as the Sustained Attention to Response Task (SART), where participants must respond to frequent non-target stimuli while withholding responses to rare target stimuli, thus also engaging in a degree of attentional inhibition (

Bauer et al. 2020).

Several studies have also focused very directly on examining the influence of mindfulness practice on attentional inhibition, a key executive function involving the ability to suppress irrelevant or interfering stimuli. As an umbrella term, inhibition is the suppression of covert responses to prevent incorrect overt responses from arising (

Verbruggen and Logan 2009) and can be measured using tasks like the flanker task (

Eriksen and Eriksen 1974;

Robertson et al. 1997), which is described later, and the Stroop colour-word task (cited in

Stroop 1935), which involves naming the colour in which a word is written while ignoring the word itself, which typically represents the name of a conflicting colour. For example,

Jensen et al. (

2012) used the Stroop colour-word task to measure attention inhibition in the following groups: (i) a mindfulness group; (ii) an active control group, where participants engaged in the Health Enhancement Programme, a non-meditative intervention incorporating activities such as physical exercise, music therapy, and nutritional education designed to match the mindfulness programme in structure and time commitment without involving meditation; and (iii) an inactive control group, where participants received no comparison treatment during the study (also referred to as a no-treatment control group; see

Kinser and Robins 2013).

Jensen et al. (

2012) reported significant improvements in performance on the Stroop task in the mindfulness group compared to both control groups following a long-term, eight-week mindfulness course.

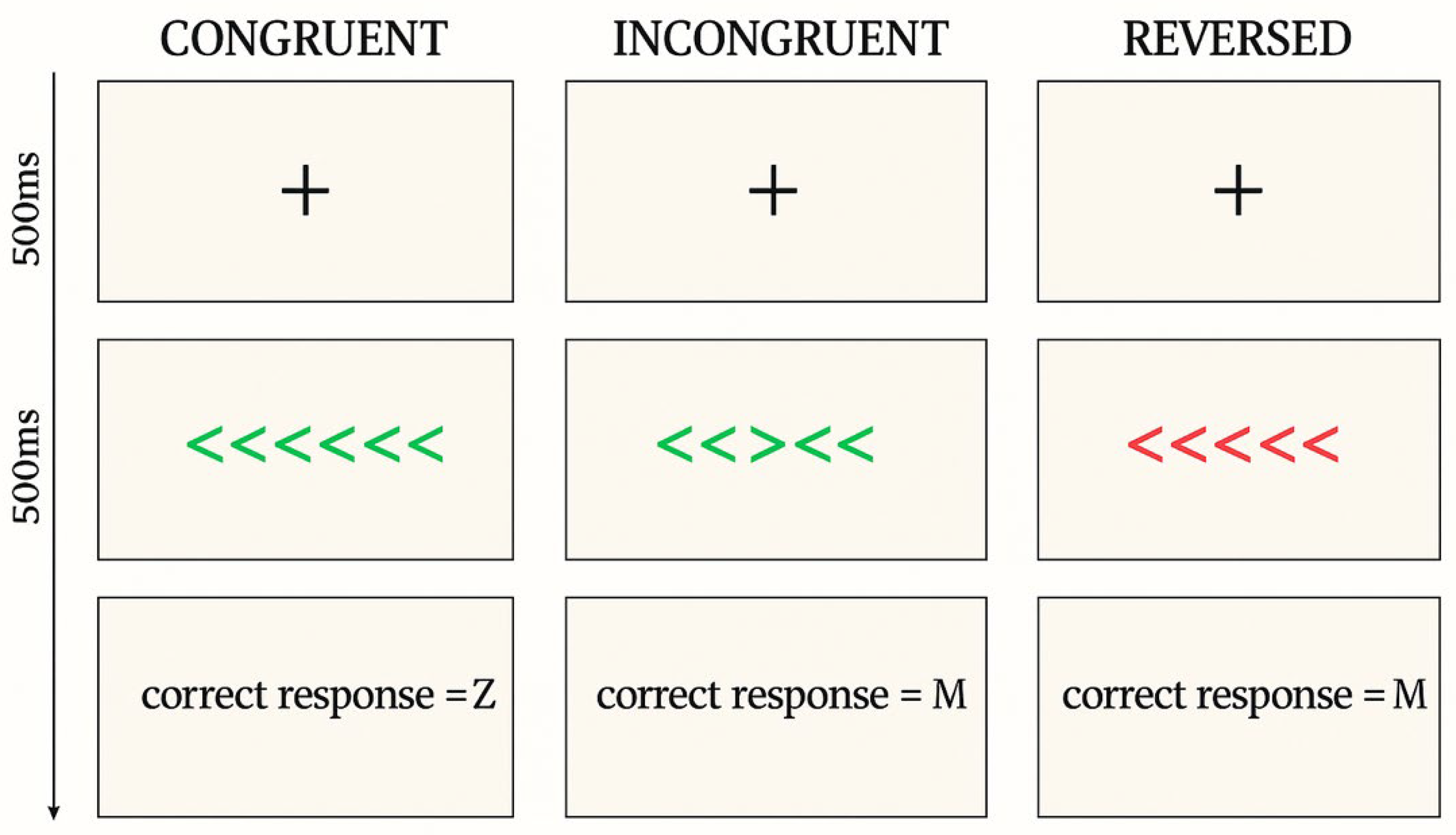

Positive outcomes on attentional inhibition have also been reported from mindfulness practice utilising conflict paradigms like the flanker task, developed by

Eriksen and Eriksen (

1974), which requires participants to focus on a central target while ignoring potentially distracting flankers. Critical to the flanker task is the occurrence of “incongruent” trials, where flankers are mapped to the opposite response category to the central target, thereby creating conflict (e.g., < < > < <), as opposed to “congruent “trials, where the flankers are mapped to the same response category as the central target (e.g., < < < < <). This manipulation typically results in slower reaction times and lower accuracy rates for incongruent relative to congruent trials (

Heuer et al. 2023;

Kałamała et al. 2018), with potential explanations rooted in conflict monitoring and cognitive control theories (

Botvinick et al. 2001;

Carter and Van Veen 2007), along with strategic influences, including the “utility principle”, which suggests that individuals allocate cognitive resources based on the anticipated costs and benefits of their responses (e.g.,

Gratton et al. 1992;

Lehle and Hübner 2008). Studies using the flanker task have shown that mindfulness interventions can improve performance on both congruent and incongruent trials, which has been taken to indicate enhanced inhibition and executive attention (

Jha et al. 2007;

Norris et al. 2018). However, not all studies replicate these findings, with the suggestion being that outcomes may be influenced by moderating factors, such as baseline mood, levels of stress, overall wellbeing, and personality characteristics, including conscientiousness or openness (

Larson et al. 2013;

Lin et al. 2019).

The flanker task has been used extensively by cognitive researchers for many years and has been modified in various ways to manipulate task demands, including through the use of dual-task conditions (e.g.,

Hogg et al. 2022) and alterations in stimulus timing (e.g.,

Melara et al. 2018). One intriguing manipulation is the use of “reversed” trials in which participants must respond with the “opposite” key to that required for the standard response for congruent and incongruent trials. Participants are alerted to reversed trials when the arrow stimuli are presented in a different colour to the standard trials (see

Section 2.3.2 for additional detail and an example figure). Reversed trials introduce an additional level of difficulty (

Bugg 2008;

Simon and Wolf 1963), because they require interference suppression and response inhibition, such that a previous stimulus-response mapping needs to be suppressed. Although few studies have employed the flanker paradigm with this type of modification, there is evidence that reversed flanker trials increase task demands, thereby leading to slower reaction times compared to standard congruent and incongruent trials (

Richardson et al. 2018). The use of reversed trials adds an additional layer of cognitive load by requiring participants to override automatic response tendencies, which arguably mimics real-world scenarios more accurately (

Braver et al. 2009). Furthermore, incorporating reversed trials can help to differentiate between basic reaction time improvements and genuine enhancements in cognitive flexibility and control mechanisms (

Egner 2008;

Hommel 2011). As such, in the study that we report below we decided to include reverse trials alongside congruent and incongruent trials.

To conclude this section, we note that although there seems to be ample evidence to support the effectiveness of mindfulness practice in improving attentional processes on the SART as well as the flanker task, it remains important to acknowledge that these tasks differ fundamentally in their cognitive demands. Modifications such as reversed trials add to the complexity that more closely mimics real-world scenarios that require interference suppression and response inhibition. By incorporating such tasks and modifications, the present research seeks to build on prior findings and provide a more nuanced understanding of how mindfulness practice influences performance across distinct attentional domains.

1.2. Attention and Convergent Thinking

There is extensive evidence suggesting that creative cognition is reliant on executive and sustained attention (

De Dreu et al. 2012;

Gilhooly et al. 2015). Specifically, convergent thinking—the process of identifying a single creative solution—has been found to correlate with working memory capacity (WMC;

Lee and Therriault 2013;

Takeuchi et al. 2020), which reflects an individual’s ability to maintain focus on a task while suppressing distracting or irrelevant thoughts (

Keller et al. 2019). Convergent thinking therefore relies heavily on the “executive control network”, which facilitates the focus required to narrow down possibilities to a single, optimal solution (

Beaty et al. 2015).

A common method for measuring convergent thinking is to present participants with a series of rebus puzzles to solve, whereby each puzzle requires a phrase or saying to be deciphered from a combination of visual, spatial, verbal, or numerical cues (

Threadgold et al. 2018). As illustrated in

Figure 1, each rebus puzzle has a single correct solution. Sustained attention is essential when attempting such puzzles to resist attentional drift while synthesising the various presented cues into a coherent representation and a possible solution response (

Robertson et al. 1997). In other words, sustained attention minimises errors from lapses in concentration, thereby acting as a stabilising force during the problem-solving process (

Unsworth et al. 2014). Furthermore, attentional inhibition is also central to the solution process with rebus puzzles to enable the filtering out of distractions and competing stimuli as well as task-irrelevant representations (

Beaty and Silvia 2012). In this way, inhibitory control ensures the maintenance of a task-relevant cognitive environment, which is crucial for preventing cognitive overload and for refining a broad array of possibilities into a single, actionable solution (

Benedek et al. 2014).

In sum, it would appear that sustained attention and attentional inhibition work together to enable people to solve convergent creative problems such as rebus puzzles. The present study focuses on the outcomes of mindfulness for these two core attentional processes and seeks to understand how these processes may be linked to convergent thinking, as assessed using rebus puzzles.

1.3. Overview of the Current Experiment

As we have discussed, extensive research has examined the cognitive advantages of mindfulness as a long-term structured experience consisting of repeated daily practice (e.g., in the form of a multi-week, mindfulness-based stress reduction course;

Hargus et al. 2010). Such studies have provided a good level of support for the benefits of long-term mindfulness interventions on sustained attention (

Bauer et al. 2020) and attentional inhibition (

Prakash et al. 2020). More recently, however, researchers have shown increased interest in examining the potentially beneficial outcomes of short-term mindfulness practice (i.e., a single session) on attentional processes, thereby avoiding the need for time-consuming, extensive and expensive long-term interventions. This has led to shorter-term mindfulness interventions, sometimes referred to as “inductions”, receiving more focus in the recent literature.

We define short-term mindfulness interventions as being those that take place over one session only. The timeframe of the sessions that have been used in the literature are seen to vary from as little as 10 min (

Norris et al. 2018) up to 90 min (

Wimmer et al. 2020), but the critical defining features of short-term interventions is that they involve neither breaks nor follow-up training sessions. When we consider these short interventions, there has been very little interest in their use until recently, perhaps due to reservations that such brief interventions are unlikely to produce any worthwhile outcomes on cognition (

Prakash et al. 2020). Surprisingly, though, research has started to reveal that interventions of only 10 min can elicit the same kinds of beneficial outcomes on cognition, including attentional control tasks, that are observed from long-term courses (

Norris et al. 2018;

Thompson et al. 2021). However, despite some limited evidence, the literature investigating interventions of less than 20 min remains sparse. The current experiment therefore builds upon the well-documented associations between mindfulness practice and its benefits for sustained attention and attentional inhibition (e.g.,

Chiesa et al. 2011;

Whitfield et al. 2022), but with a specific focus on short mindfulness practice and the role of any resulting benefits of enhanced attentional processes for creative cognition, as measured in terms of convergent thinking performance.

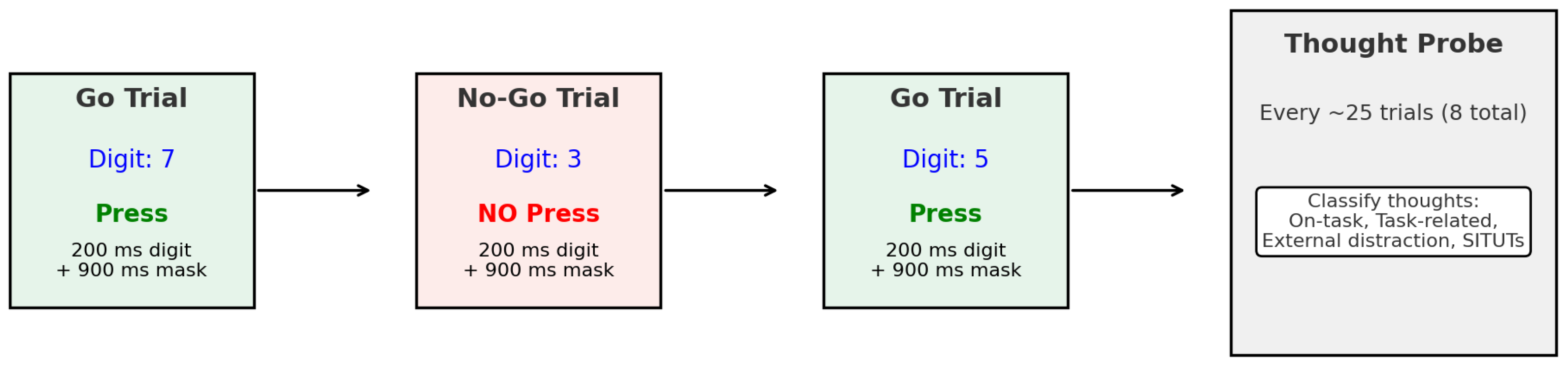

To assess sustained attention, we employed the Sustained Attention to Response Task (SART) with embedded thought probes. This task not only measures participants’ ability to maintain focus over time but also provides insight into the prevalence of “mind-wandering” through the use of the thought probes that serve as a proxy for attentional lapses, which mindfulness practice is reported to reduce (

Verhaeghen 2021). The SART’s relatively low cognitive demand makes it ideal for examining mind-wandering episodes. Research has consistently shown that lower task demands correlate with higher frequencies of mind wandering, as attentional resources are less fully engaged (e.g.,

Brosowsky et al. 2021). By incorporating thought probes, we aimed to directly measure participants’ self-reported attention during the task, providing a nuanced understanding of how brief mindfulness interventions influence sustained attention and whether this is evidenced by mitigated task-irrelevant thoughts.

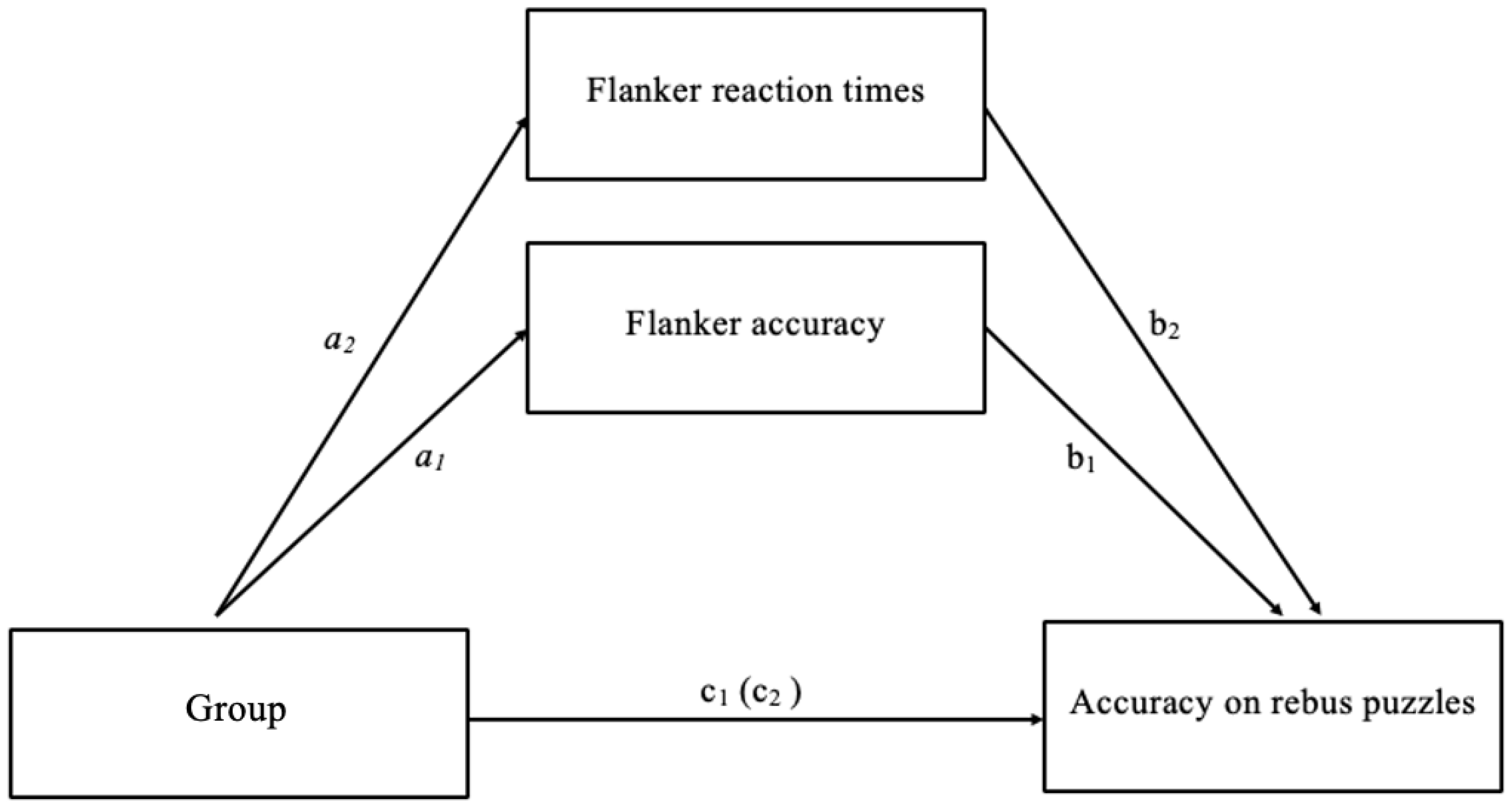

To assess attentional inhibition in our experiment, we adopted a flanker task. As we discussed above, this task requires participants to focus on a central target while ignoring distracting flankers. The inclusion of both congruent and incongruent trials, alongside novel “reversed” trials, enabled a detailed examination of inhibitory control under varying levels of cognitive demand. The outcomes of this task are particularly relevant for understanding how mindfulness practice may enhance an individual’s ability to suppress irrelevant stimuli and resolve cognitive conflict, both of which are essential for successful convergent thinking.

We predicted that on the SART, the mindfulness group would be more accurate, reflecting enhanced sustained attention and less task-irrelevant thoughts caused by mind wandering (as measured using mind-wandering probes). Turning to the flanker task, we predicted that participants in the mindfulness group would exhibit faster reaction times and higher accuracy compared to the control group, particularly for incongruent trials, which require attentional inhibition, as well as for reversed trials, which require the inhibition of a previously associated response mapping. In congruent trials, although both groups would be expected to perform well, we reasoned that the mindfulness group may demonstrate improved performance due to improved attentional focus. In relation to our convergent thinking measure, we expected that the mindfulness group would have higher accuracy on rebus puzzles, drawing on evidence that mindfulness practice improves convergent thinking through enhanced sustained attention and attentional inhibition, which are essential for the process of generating single correct responses in convergent thinking tasks. We planned to assess the role of sustained attention and attentional inhibition in mediating the link between mindfulness and creative performance by undertaking a statistical mediation analysis. In summary, we hypothesise the following:

- (i)

Sustained attention and attentional inhibition will be higher in the mindfulness group relative to the control group.

- (ii)

Convergent thinking performance will be higher in the mindfulness group relative to the control group.

- (iii)

Attentional improvements will mediate any observed link between mindfulness and convergent thinking.