Listen Closely: Self-Supervised Phoneme Tracking for Children’s Reading Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Research Questions

- 1.

- Feasibility of Accurate Phonetic Recognition: Is it feasible to achieve accurate phonetic recognition in children’s speech using a Wav2Vec2 model fine-tuned with less than 25 h of data, and what are the key factors that influence this performance?

- 2.

- Trade-off Between Data Quality and Quantity: How does the trade-off between data quality and quantity affect phoneme recognition performance in children’s speech? This question explores whether it is more helpful to fine-tune a pretrained Wav2Vec2 model with a small amount of high-quality data or with a larger amount of lower-quality data.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Measuring and Analyzing Reading Fluency

- SoapBox Labs offers a speech recognition engine optimized for children’s voices, designed as backend technology for integration into educational tools. It handles mispronunciations, accents, and noise, providing real-time feedback on pronunciation, fluency, and pace, and supports multiple languages including German, English, Spanish, and Mandarin [8].

- Ello is an AI reading tutor for kindergarten to Grade 3, with over 700 decodable e-books tailored to a child’s level and interests. It listens to children reading aloud, giving real-time feedback, and supports both digital and physical books. Currently, it is only available in English and targets the US market [9].

- Microsoft Reading Coach provides AI-driven, individualized reading support, identifying words or patterns students struggle with and offering targeted exercises. Integrated with Microsoft Teams and Reading Progress, it helps track progress and reduce teacher workload [10].

- Google Read Along listens to children reading aloud, highlights mistakes, and integrates with Google Classroom for task assignment and progress tracking. It supports several languages, including English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Hindi, but not German [11].

2.2. Speech Recognition for Reading Assessment

2.2.1. Fundamentals of Speech Recognition

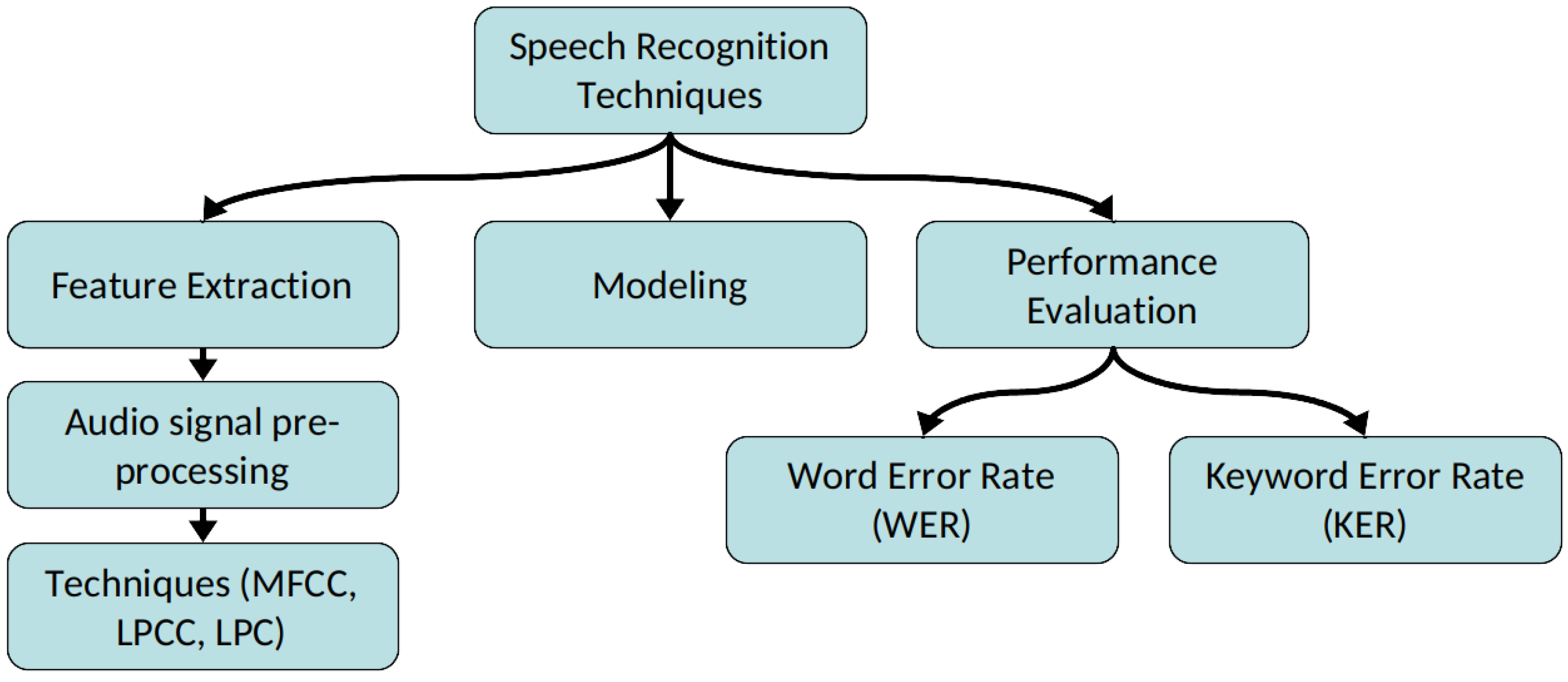

Feature Extraction

Modeling

- Acoustic-Phonetic Approach: This is one of the oldest strategies and based on linguistic knowledge, assuming that speech consists of finite phones. These units can be identified using formant analysis and time-domain processing. Early ASR systems used handcrafted linguistic principles by manually defining phoneme transition rules.

- Pattern Recognition Approach: This approach treats speech recognition as a classification problem. Statistical models learn patterns in phoneme pronunciation from large speech datasets. There exist two different methods. The template matching approaches which simply tries to find the best match compared to a already existing record and the stochastic approach. Examples for this are the Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and Dynamic Time Warping described in a upcoming Section 2.2.4. These techniques enhanced ASR performance, they required extensive manual tuning and struggled with generalization.

- Deep Learning Approach: Modern ASR systems use deep learning models to learn speech representations directly from data. This eliminates the need for handcrafted phonetic rules. These models handle noisy environments, multiple languages, and real-time speech processing with unprecedented accuracy. A more detailed look into this is again taken in a later Section 2.2.5.

Performance Evaluation Techniques

- Word Error Rate (WER): The most common metric, quantifying the percentage of words inserted, deleted, or substituted in the ASR transcript. Lower WER indicates better performance compared to the reference transcript.

- Phoneme Error Rate (PER): Focuses on errors at the phoneme level rather than entire words. This is useful for analyzing systems working with languages having complex phonetic structures.

- Sentence Error Rate (SER): Assesses the correctness of full sentences, providing a broader evaluation of ASR accuracy in conversational speech.

2.2.2. Challenges in Children’s Speech Recognition

- Physiological and Anatomical Differences: As children grow, both their physical development and speech characteristics change. These changes are largely influenced by the differences in the structure of their vocal tract compared to adults. The smaller size of children’s vocal folds and shorter vocal tracts result in higher pitch and sound frequencies in their speech. These physiological differences contribute to the distinct sound of children’s voices, making their speech sound different from that of adults. Additionally, children have less control over speech features like tone, rhythm, and intonation due to the ongoing development of their vocal control mechanisms. As they grow older, when around 12 to 14 years old, their speech becomes more similar to adult speech [15,16].

- Pronunciation Variability: When it comes to pronunciation, younger children often struggle with articulating words accurately due to their limited experience with language. Children’s vocabulary tends to be smaller than that of adults, and they often rely on their imagination to create words [15].

- Limited Training Data: There isn’t enough good-quality speech data from children to train ASR systems. Collecting this kind of data is hard because of privacy issues and other challenges. As a result, ASR models struggle to understand children’s speech since they weren’t trained on enough examples from children [13].

2.2.3. Augmentation Techniques for Children’s Speech

- Vocal Tract Length Normalization (VTLN): VTLN specifically addresses the physiological differences between adult and child vocal tracts. Since children have shorter vocal tracts, their formant frequencies are shifted higher. VTLN applies a warping function to the frequency axis of the speech spectrum to normalize these differences. Potamianos and Narayanan demonstrated that VTLN alone could reduce WER by 10–20% relative for children’s speech.

- Maximum Likelihood Linear Regression (MLLR): MLLR adapts the parameters of a GMM-HMM system by applying a linear transformation to the mean vectors of the Gaussian components. This technique can adapt to both speaker-specific characteristics and acoustic conditions. For children’s speech, MLLR helps the model adjust to the higher pitch and formant frequencies characteristic of children’s voices.

- SpecAugment: SpecAugment, introduced by Park et al. in 2019 [17] from the Google Brain team, is a data augmentation method used to make automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems more robust. It works directly on log mel spectrograms and applies three simple changes: time warping, frequency masking, and time masking. These changes imitate missing or noisy parts of speech, helping the model become more flexible and better at handling different audio conditions. According to the initial paper, SpecAugment led to much lower word error rates on often compared benchmarks like the LibriSpeech and reached strong results without using extra language models.

2.2.4. Traditional Speech Recognition Approaches

Dynamic Time Warping (DTW)

- 1.

- A reference template is created for each word or phoneme in the vocabulary

- 2.

- The input speech is converted to a sequence of acoustic feature vectors

- 3.

- A distance matrix is computed between the input sequence and each reference template

- 4.

- The algorithm finds the path through this matrix that minimizes the total distance while satisfying continuity constraints

- 5.

- The template with the lowest distance score is selected as the recognized word

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) with Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs)

- 1.

- Breaking Speech into Frames: The speech signal is split into short time frames (typically 25 ms each). This helps analyze speech as a sequence of small, overlapping sound units.

- 2.

- Extracting Features: Instead of working directly with the raw audio waveform, the system extracts important characteristics from each frame. A common method for this is Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCCs), which were already mentioned previously.

- 3.

- Modeling Speech Sequences with HMMs: Speech is not just a set of isolated sounds, it follows a structured order. HMMs help capture this structure by representing speech as a sequence of hidden states. Each state corresponds to a phoneme. The system learns how likely it is for one sound to follow another by analyzing large amounts of training data.

- 4.

- Modeling Sound Variability with GMMs: People pronounce the same word in different ways depending on their accent, speed, and tone. GMMs help handle this variation by modeling the probability distribution of acoustic features within each HMM state.

- 5.

- Recognizing Speech: Once the model is trained, it can analyze new speech samples. Given a sequence of extracted features, the system determines the most likely sequence of HMM states that match the observed speech. The Viterbi algorithm, a well-known dynamic programming method, is commonly used to find this optimal sequence.

2.2.5. Deep Learning & the Transformer Architecture

Wav2Vec2-Self-Supervised Speech Recognition

- Raw Audio Input: The model begins with continuous raw audio waveforms sourced from large-scale, predominantly unlabeled multilingual speech datasets. These corpora encompass a wide range of speaking styles, recording conditions, and linguistic diversity, including read speech, conversational speech, and spontaneous speech. Examples include Common Voice, Multilingual LibriSpeech, and VoxPopuli, which together provide hundreds of thousands of hours of audio across dozens of languages. This extensive variability enables the model to develop robust, language-agnostic acoustic representations.

- Feature Extraction with CNN: A convolutional neural network (CNN) processes the raw waveform into a sequence of latent acoustic features. The CNN progressively downsamples the audio while preserving salient temporal and spectral cues, effectively converting high-frequency waveform information into a compact representation. This front-end captures low-level characteristics such as energy contours, pitch variations, and local phonetic structure, producing features suitable for higher-level contextual modeling.

- Transformer: The extracted feature sequence is then passed to a Transformer network, which models contextual relationships across long temporal spans. Through self-attention mechanisms, the Transformer integrates information distributed across entire utterances, allowing the model to infer dependencies between distant acoustic events such as syllable structure, prosody, and cross-phoneme transitions. This stage is crucial for capturing long-range linguistic patterns that cannot be represented by local convolution alone.

- Self-Supervised Learning: During pre-training, a subset of the Transformer’s input representations is randomly masked. The model is then trained to reconstruct the masked segments using a quantization module that maps continuous embeddings to a finite set of learned discrete speech units. This contrastive prediction task encourages the model to learn phonetic and subphonetic regularities without any labeled supervision, allowing it to generalize across languages and domains. By predicting masked content, the model develops internally consistent, language-independent acoustic abstractions.

- Fine-Tuning Layer: After self-supervised pre-training, the learned speech representations can be adapted to downstream tasks through the addition of lightweight task-specific output layers. Fine-tuning is performed on labeled datasets tailored to the target task, enabling the model to specialize in speech recognition, speech-to-text translation, speaker or language classification, or other speech processing objectives. Because the bulk of the model is already pretrained, only modest amounts of labeled data are required to achieve strong performance across a wide range of applications.

Alternative Deep-Learning Models

- HuBERT (Hidden-Unit BERT), introduced by Hsu et al. [26] in 2021, is a self-supervised model that clusters audio segments via k-means to create pseudo-labels, then predicts these labels for masked segments. This approach learns phonetic and linguistic structures without transcripts and has shown strong performance in phoneme recognition.

- WavLM, presented by Chen et al. [27] in 2022, extends Wav2Vec2 with improved masking, denoising objectives, and training on larger, more diverse datasets. It performs well in noisy conditions and supports tasks such as speaker diarization and speech separation.

- Whisper, developed by OpenAI [28] in 2023, is a supervised model trained on 680,000 h of labeled speech. It handles transcription, translation, and language identification across many languages and noisy environments, but is less suited for small phoneme-level tasks.

2.2.6. Deep Learning Models Applied to Children’s Speech Recognition

- Implementing Wav2Vec2 into an Automated Reading Tutor: Mostert et al. [29] integrated Wav2Vec2 models into a Dutch automated reading tutor to detect mispronunciations in children’s speech. Two variants were trained on a Dutch speech therapy corpus and 20 h of children’s speech: an end-to-end phonetic recognizer and a phoneme-level mispronunciation classifier. Both outperformed the baseline Goodness-of-Pronunciation detector in phoneme-level accuracy and F-score, yielding modest gains in phone-level error detection but little change in word-level accuracy. The study suggests Wav2Vec2 can enhance fine-grained phonetic feedback.

- Phoneme Recognition for French Children: Medin et al. [30] compared Wav2Vec2.0, HuBERT, and WavLM to a supervised Transformer baseline for phoneme recognition in French-speaking children. Models were trained on 13 h of child speech, with cross-lingual English data offering no benefit. WavLM achieved the lowest phoneme error rate (13.6%), excelling on isolated words and pseudo-words, and proved most robust under noise (31.6% vs. baseline 40.6% at SNR < 10 dB). Results show self-supervised models, especially WavLM, improve phoneme recognition in noisy conditions.

- Adaptation of Whisper models to child speech recognition: Jain et al. [31] fine-tuned Whisper-medium and large-v2 on 65 h of child speech (MyST and PF-STAR) and compared them to Wav2Vec2. Fine-tuning reduced Whisper-medium’s WER on MyST from 18.1% to 11.7%, with large-v2 reaching 3.1% on PF-STAR. Wav2Vec2 achieved the best matched-domain results (2.9% PF-STAR, 10.2% MyST), while Whisper generalized better to unseen domains.

- Benchmarking Children’s ASR: Fan et al. [32] benchmarked Whisper, Wav2Vec2, HuBERT, and WavLM on MyST (133 h) and OGI Kids (50 h) datasets. In zero-shot tests, large Whisper models performed well (12.5% WER on MyST), with fine-tuning further reducing errors (Whisper-small: 9.3%, WavLM: 10.4%). On OGI, Whisper-small achieved 1.8% WER. Data augmentation gave small, consistent gains. Overall, fine-tuned Whisper models generally outperformed self-supervised models of similar size.

2.3. Summary and Research Gap

2.3.1. Summary

2.3.2. Research Gap

3. Approach and Methodology

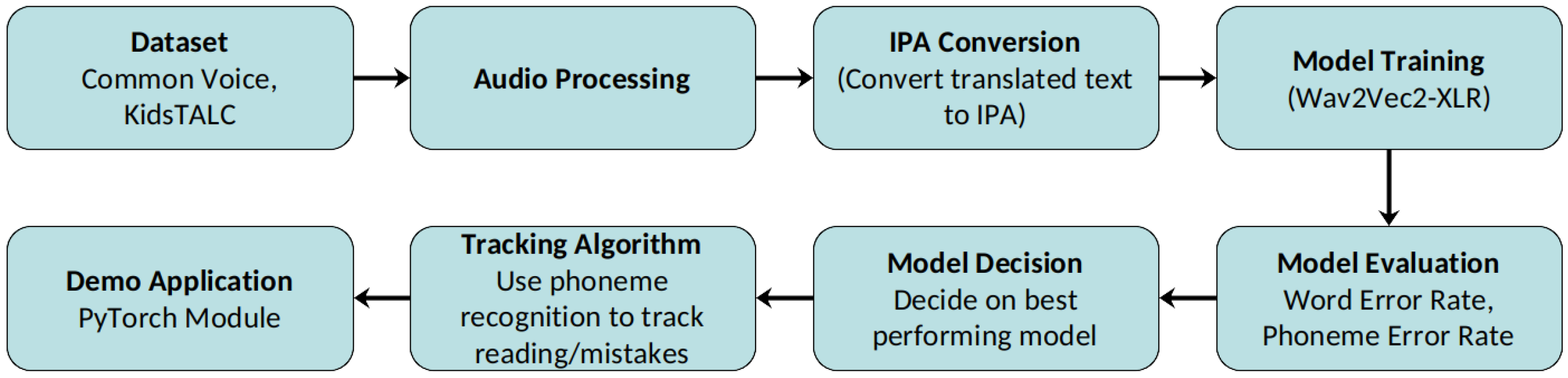

3.1. System Overview

3.2. Datasets and Resources

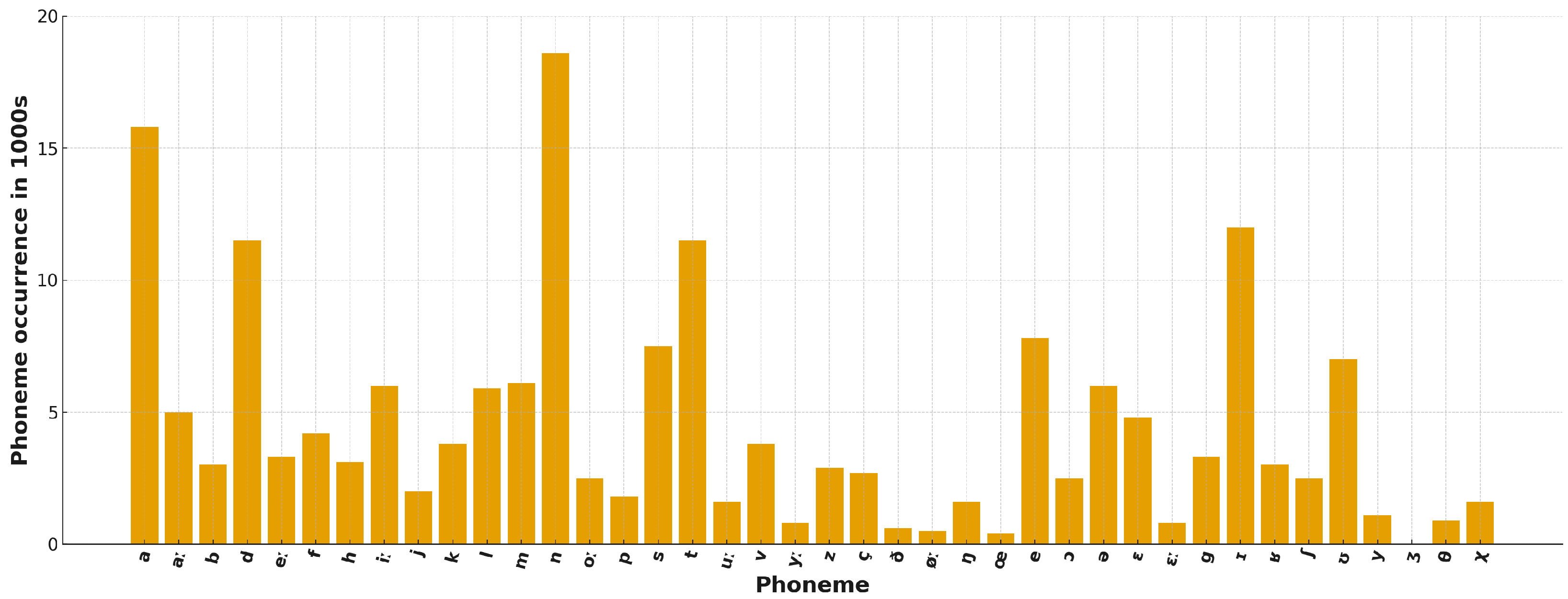

3.2.1. Word and Phoneme Occurrence

3.2.2. Limitations

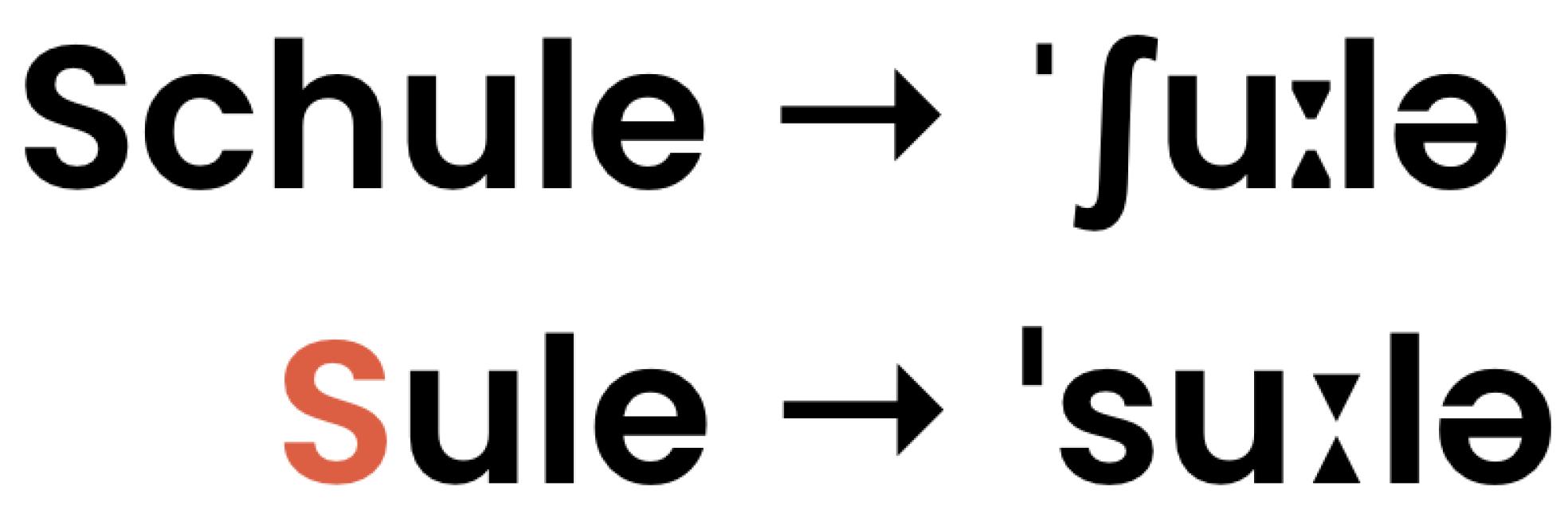

3.3. IPA and Phoneme-Level Annotation

- /ʃ/

- represents the “sh” sound, as heard in the English word “shoe” or the German word “schön”. It is produced by placing the tongue near the roof of the mouth without touching it and letting air flow through.

- /uː/

- is a long “oo” sound, like in the English word “food” or the german word “gut”. It is produced with rounded lips and the tongue positioned high and towards the back of the mouth.

- /l/

- corresponds to the familiar “l” sound, as in “Lampe”. It is made by touching the tip of the tongue to the area just behind the upper front teeth.

- /ə/

- is known as a schwa, a very short and neutral vowel sound. It often occurs in unstressed syllables, such as the second syllable in the German word “bitte”. The tongue remains in a relaxed, central position.

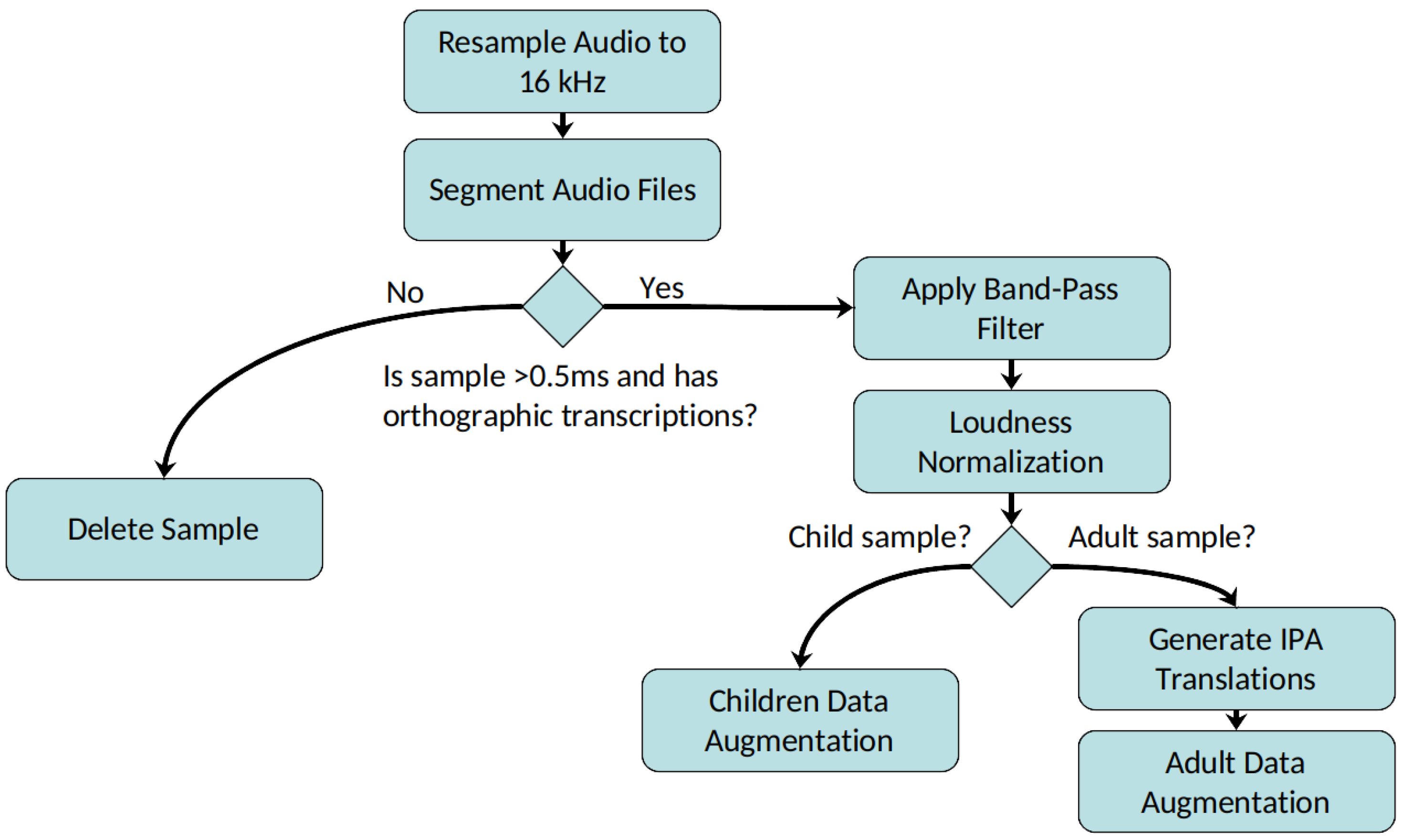

3.4. Data Preparation & Augmentation

3.4.1. Data Preprocessing

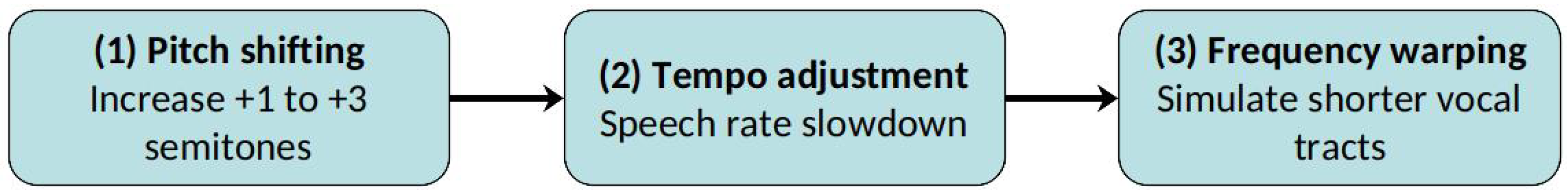

3.4.2. Data Augmentation

- Pitch Shift: Applied randomly within a narrow range to child samples and with stronger upward shifts for adults to increase similarity to the higher pitch of children’s voices.

- Vocal Tract Length Normalization (VTLN): Is a speaker-normalization technique that reduces variability in speech signals by compensating for differences in speakers’ vocal tract lengths, which affect the resonance patterns of the vocal tract and thus the observed spectral characteristics. The method operates by applying a child-specific warping of the frequency axis, typically parameterized by a single scalar warp factor that stretches or compresses the spectrum so that speakers with different tract lengths are mapped to a common acoustic space. This warp factor is usually estimated through maximum-likelihood procedures, where the value that best aligns the child’s speech features with an acoustic model is selected.

- Speed Perturbation: Applied to both groups. For children, only small variations were introduced. For adults, a slower speed was used more frequently to resemble the typically slower speech rate of children.

3.5. Model Architecture

3.5.1. Model Choice and Justification

3.5.2. Fine-Tuning Setup

3.6. Evaluation Setup

- Substitutions (S): a predicted token is incorrect (e.g., /b/ instead of /p/).

- Deletions (D): a token from the reference is missing in the predicted output.

- Insertions (I): an extra token appears in the predicted output that is not present in the reference.

3.6.1. Phoneme Error Rate (PER)

3.6.2. Word Error Rate (WER)

3.6.3. Evaluation Procedure

4. Practical Implementation

4.1. Data Preparation and Preprocessing

4.2. Audio Processing

4.3. Data Augmentation

4.3.1. Adult Speech Data and “Childrenization”

4.3.2. Data Augmentation for Children’s Speech

4.4. Implementation of Wav2Vec2

- Tokenizer: The tokenizer is responsible for converting text into a sequence of token IDs and vice versa. For Wav2Vec2, a special CTC tokenizer is used which is based on a custom vocabulary file (vocab.json) which all the phonetic symbols of the target text like shown in [35]. In addition, two special tokens for unknown characters and padding have been added.

- Feature Extractor: The feature extractor transforms the raw audio samples into a format suitable for input to the Wav2Vec2 model. This preprocessing step typically involves resampling, normalization and segmenting the waveform into smaller frames.

- Trainer: At its core, the system uses the pretrained facebook/wav2vec2-xls-r-300m checkpoint, a multilingual model with 300 million parameters trained in a self-supervised fashion. Instantiating it appends a linear classification layer to the Transformer encoder which head maps the model’s hidden representations to phoneme-level tokens and is trained during the fine-tuning process. The Trainer is set up with the training and evaluation datasets, the model and training arguments. To monitor performance and adjust training behavior, a custom metric computation function has been added to ensure that the model is evaluated using PER and WER, as described in Section 3.6.

4.5. Hyper-Parameter Tuning

4.6. Overfitting Avoidance

4.7. Training Configurations and Model Variants

- (1)

- Mixed Data Model: The first model trained was based on the idea that more data, regardless of quality, might improve generalization. This version used a large and diverse training set created from the KidsTALC dataset, combining both children’s and adult speech, along with various augmented versions of each. The dataset also included samples of mixed quality, such as recordings with background noise or unclear articulation. This model aimed to make full use of all available data and test whether the model could still learn useful speech patterns despite inconsistencies.

- (2)

- Child-Only Model: The second model was trained exclusively on child speech data from the KidsTALC dataset, including both original and augmented recordings. No adult speech was used. This variant focused on learning the specific acoustic and phonetic characteristics of young speakers. By removing adult voices, the model could specialize more closely in the types of speech it is expected to analyze during real-world use.

- (3)

- Combined Clean Children + Adult Model (No Augmentation): The final model used a carefully filtered subset of the KidsTALC dataset, containing only clean, original recordings from both children and adults. All samples marked as hard to understand, noisy, or overlapping were excluded and no data augmentation was applied. This variant was designed to test whether using only high-quality, natural speech would lead to more stable and accurate recognition, particularly in contrast to the larger but noisier training sets used in the previous models.

4.8. Experiment Tracking with Weights & Biases

4.9. Model Evaluation

5. Evaluation and Results

5.1. Model Performance Analysis

5.1.1. Overall Performance of the Models

Model 1: Mixed Data

Model 2: Child-Only Data

Model 3: Clean Data

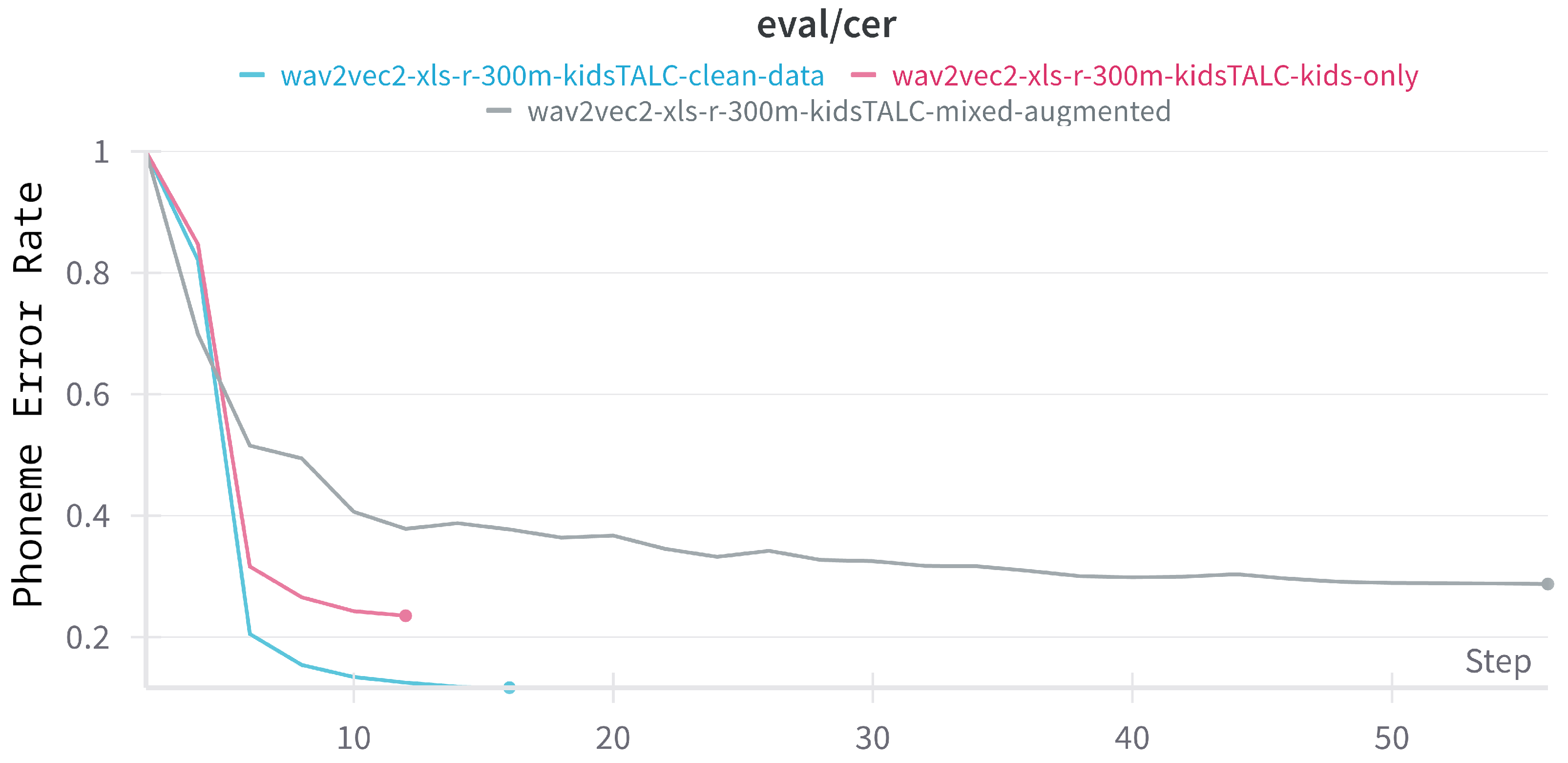

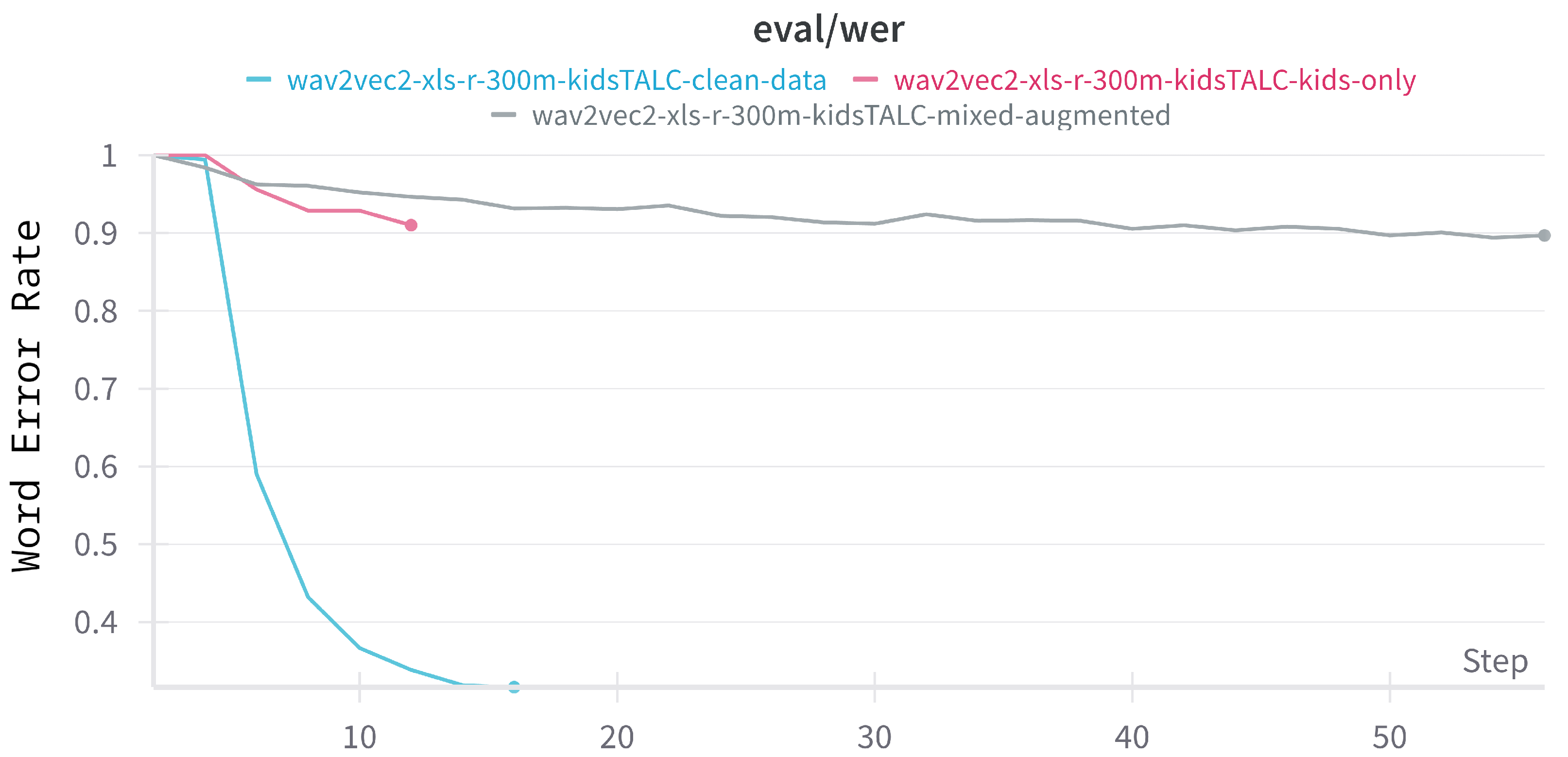

5.1.2. Phoneme and Word Error Rate Progression During Training

Phoneme Error Rate (PER)

Word Error Rate (WER)

5.1.3. Best Model Analysis

Vowel Confusions

Word-Final Deletions

Short Utterance Misrecognition

Word Boundary Errors

5.2. Comparison with Existing Solutions

5.2.1. Comparison with Self-Supervised Solutions

French Child Speech with WavLM

Comparison to Common Benchmarks: Timit Dataset

5.2.2. Comparison with Previous KidsTALC Results

5.2.3. Comparison with Human Performance

5.3. Addressing the Research Questions

5.3.1. Is Accurate Phoneme-Level Recognition Possible with Limited Clean Data?

5.3.2. How Does the Trade-Off Between Data Quality and Quantity Affect Phoneme Recognition Performance in Children’s Speech?

6. Discussion

6.1. System Analysis

6.1.1. Strengths

- Recognition Accuracy with Limited Data: One of the system’s most notable achievements is its high phoneme recognition accuracy, despite being trained on a relatively small dataset. This success is largely due to the use of self-supervised learning with the Wav2Vec2-XLSR model, which was fine-tuned on a carefully selected and cleaned subset of children’s speech. By including both child and adult speech in the fine-tuning phase, the model was able to generalize well, including those not seen during training. This shows that a combination of high-quality data and diversity can compensate for limited training volume when fine-tuning a strong pre-trained model.

- Phoneme-Level Output and IPA Representation: Another technical strength of the system is its ability to produce phoneme-level transcriptions using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). This allows it to detect subtle pronunciation errors that word-level models might overlook. In combination with a matching algorithm, the model could be able to provide feedback on partial word production, sound substitutions or mispronounced endings. The use of IPA also makes the system adaptable for other languages or multilingual settings, improving its long term flexibility.

- Educational Value and Scalability: From an educational perspective, the system offers detailed and objective feedback that can assist teachers, researchers, or digital learning tools. It identifies which sounds individual children struggle with, supports tracking of progress over time, and helps recognize patterns in reading development. Since its accuracy approaches the level of human transcription, the system can serve as a scalable assessment assistant. Unlike a teacher, it can be used by multiple learners at once, making it practical for classroom settings or large-scale studies.

6.1.2. Limitations

- Phoneme Confusions and Speech Variability: One challenge lies in distinguishing between similar sounding phonemes, particularly consonant pairs that differ only in voicing, such as [b] vs. [p] and [e] vs. [ε].

- Speaker and Recording Variability: The model is also sensitive to variations in recording conditions. Background noise, microphone quality, and overall audio clarity can significantly influence performance. This may limit the reliability of the system in uncontrolled environments, such as homes or busy classrooms. Furthermore, the KidsTALC dataset used in training contains recordings collected under relatively uniform conditions, which may not generalize well to more diverse real-world settings.

- Model Size and Deployment Constraints: A significant practical limitation is the model’s size. The fine-tuned Wav2Vec2 model used is approximately 1.3 GB, making it unsuitable for deployment on most mobile devices or tablets. Without further optimization, the model requires server-based processing, which complicates deployment in classrooms or homes.

6.2. Key Findings

6.3. Future Work and Improvements

6.3.1. More Data and Variability

6.3.2. Utilize Data from Similar Languages

6.3.3. Reading Mistake Classification

6.3.4. Fine-Grained Error Analysis

6.3.5. Extended Evaluation on Unseen Data

6.3.6. Streaming ASR Development

6.3.7. Model Compression and Deployment

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, Y.J.; Sahakian, B.J.; Langley, C.; Yang, A.; Jiang, Y.; Kang, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, C.; Cheng, W.; Feng, J. Early-initiated childhood reading for pleasure: Associations with better cognitive performance, mental well-being and brain structure in young adolescence. Psychol. Med. 2024, 54, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ORF Science. Lesende Kinder Werden Zufriedene Jugendliche. 2023. Available online: https://science.orf.at/stories/3219992/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Der Standard. PIRLS-Studie: Jedes fünfte Kind in Österreich hat Probleme beim Lesen. 2023. Available online: https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000146458792/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Statista. Mediennutzung von Kindern-Statistiken und Umfragen. 2024. Available online: https://de.statista.com/themen/2660/mediennutzung-von-kindern/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- The Access Center. Early Reading Assessment: A Guiding Tool for Instruction. 2024. Available online: https://www.readingrockets.org/topics/assessment-and-evaluation/articles/early-reading-assessment-guiding-tool-instruction (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Professional Development Service for Teachers (PDST). Running Records. 2015. Available online: https://www.pdst.ie/sites/default/files/Running%20Records%20Final%2015%20Oct.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Bildung durch Sprache und Schrift (BiSS). Salzburger Lesescreening für die Schulstufen 2–9 (SLS 2–9). 2023. Available online: https://www.biss-sprachbildung.de/btools/salzburger-lesescreening-fuer-die-schulstufen-2-9/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- SoapBox Labs. Children’s Speech Recognition & Voice Technology Solutions. Available online: https://www.soapboxlabs.com/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Hello Ello. Read with Ello. Available online: https://www.ello.com/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Ravaglia, R. Microsoft Reading Coach—Seamless AI Support For Students and Teachers. Forbes. 2024. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/rayravaglia/2024/01/18/microsoft-reading-coach-seamless-ai-support-for-students-and-teachers/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Google. Read Along. Available online: https://readalong.google.com/ (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Basak, S.; Agrawal, H.; Jena, S.; Gite, S.; Bachute, M.; Pradhan, B.; Assiri, M. Challenges and limitations in speech recognition technology: A critical review of speech signal processing algorithms, tools and systems. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2023, 135, 1053–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, G.; Alwan, A. On the difficulties of automatic speech recognition for kindergarten-aged children. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2018, Hyderabad, India, 2–6 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcy, S.; Russell, M.J. A comparison of human and computer recognition accuracy for children’s speech. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2005, Lisbon, Portugal, 4–8 September 2005; pp. 2197–2200. [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj, V.; Ben Othman, M.T.; Kukreja, V.; Belkhier, Y.; Bajaj, M.; Goud, B.S.; Rehman, A.U.; Shafiq, M.; Hamam, H. Automatic speech recognition (asr) systems for children: A systematic literature review. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, M.J.; D’Arcy, S. Challenges for computer recognition of children’s speech. SLaTE 2007, 108, 111. [Google Scholar]

- Park, D.S.; Chan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chiu, C.C.; Zoph, B.; Cubuk, E.D.; Le, Q.V. SpecAugment: A Simple Data Augmentation Method for Automatic Speech Recognition. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2019, Graz, Austria, 15–19 September 2019; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoe, H.; Chiba, S. Dynamic programming algorithm optimization for spoken word recognition. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1978, 26, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Alam, M.A. Dynamic time warping (dtw) algorithm in speech: A review. Int. J. Res. Electron. Comput. Eng. 2018, 6, 524–528. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiner, L.R. A tutorial on hidden Markov models and selected applications in speech recognition. Proc. IEEE 1989, 77, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. Study on a CNN-HMM approach for audio-based musical chord recognition. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1802, 032033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kushwaha, N. A Basic High-Level View of Transformer Architecture & LLMs from 35000 Feet. Python Plain Engl. 2023. Available online: https://python.plainenglish.io/a-basic-high-level-view-of-transformer-architecture-llms-from-35000-feet-c036dd2f7c25 (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Baevski, A.; Zhou, Y.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M. wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 12449–12460. [Google Scholar]

- Conneau, A.; Khandelwal, K.; Goyal, N.; Chaudhary, V.; Wenzek, G.; Guzmán, F.; Grave, E.; Ott, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Unsupervised Cross-lingual Representation Learning at Scale. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; Jurafsky, D., Chai, J., Schluter, N., Tetreault, J., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 8440–8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.N.; Bolte, B.; Tsai, Y.H.H.; Lakhotia, K.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Mohamed, A. Hubert: Self-supervised speech representation learning by masked prediction of hidden units. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 3451–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Li, J.; Kanda, N.; Yoshioka, T.; Xiao, X.; et al. Wavlm: Large-scale self-supervised pre-training for full stack speech processing. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2022, 16, 1505–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust speech recognition via large-scale weak supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; PMLR. pp. 28492–28518. [Google Scholar]

- Mostert, N. Implementing Wav2Vec 2.0 into an Automated Reading Tutor. Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Medin, L.B.; Pellegrini, T.; Gelin, L. Self-Supervised Models for Phoneme Recognition: Applications in Children’s Speech for Reading Learning. In Proceedings of the 25th Interspeech Conference (Interspeech 2024), Kos Island, Greece, 1–5 September 2024; Volume 9, pp. 5168–5172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Barcovschi, A.; Yiwere, M.; Corcoran, P.; Cucu, H. Adaptation of Whisper models to child speech recognition. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.13008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, R.; Shankar, N.B.; Alwan, A. Benchmarking Children’s ASR with Supervised and Self-supervised Speech Foundation Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.10507. [Google Scholar]

- Rumberg, L.; Gebauer, C.; Ehlert, H.; Wallbaum, M.; Bornholt, L.; Ostermann, J.; Lüdtke, U. kidsTALC: A Corpus of 3- to 11-year-old German Children’s Connected Natural Speech. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2022, Incheon, Republic of Korea, 18–22 September 2022; pp. 5160–5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardila, R.; Branson, M.; Davis, K.; Kohler, M.; Meyer, J.; Henretty, M.; Morais, R.; Saunders, L.; Tyers, F.; Weber, G. Common Voice: A Massively-Multilingual Speech Corpus. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020; Calzolari, N., Béchet, F., Blache, P., Choukri, K., Cieri, C., Declerck, T., Goggi, S., Isahara, H., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., et al., Eds.; European Language Resources Association: Reykjavik, Iceland, 2020; pp. 4218–4222. [Google Scholar]

- International Phonetic Association. The International Phonetic Alphabet (2020 Revision). Available online: https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/IPAcharts/IPA_chart_orig/pdfs/IPA_Kiel_2020_full.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Bernard, M.; Titeux, H. Phonemizer: Text to Phones Transcription for Multiple Languages in Python. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, T.; Debut, L.; Sanh, V.; Chaumond, J.; Delangue, C.; Moi, A.; Cistac, P.; Rault, T.; Louf, R.; Funtowicz, M.; et al. Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Biewald, L. Experiment Tracking with Weights and Biases. 2020. Available online: https://wandb.ai/site/experiment-tracking/ (accessed on 11 December 2025).

| Age | Sex | Duration in Minutes | Number of Speakers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3–4 years | f | 101.3 | 6 |

| m | 85.3 | 4 | |

| 5–6 years | f | 176.0 | 8 |

| m | 166.1 | 8 | |

| 7–8 years | f | 36.6 | 2 |

| m | 58.3 | 3 | |

| 9–10 years | f | 40.3 | 3 |

| m | 85.9 | 5 |

| Augmentation Parameter | Adult | Child | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pitch Shift (in semitones) | 1.0–3.0 | −1.0–1.0 | Simulate child-like speech and add variation |

| VTLN Factor (in percent) | 120–150% | 95–105% | Adapt formant profile to simulate shorter vocal tract |

| Speed Factor (in percent) | 85–95% | 90–110% | Reflect slower speech rate or natural variability |

| Augmentation Ratio | 1:1 | 2:1 | Increase training diversity and robustness |

| Amount of Augmented Samples | 6514 | 14,452 |

| Hyperparameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Learning rate | 3 | This controls how big the steps are when the model learns. A small learning rate means the model learns slowly but more carefully. |

| Batch size | 8 | This is how many examples the model looks at before updating itself. Smaller batches use less memory but can make learning a bit noisier (the updates might jump around more because each batch gives a less overview of the whole dataset). |

| Number of epochs | 45 | Number of complete passes through the training dataset. |

| Evaluation steps | 500 | Specifies how often (in number of training steps) the model is evaluated on the validation set. |

| Warmup ratio | 0.1 | Fraction of total training steps used to gradually increase the learning rate from zero. This helps to stabilize early training. |

| Learning rate scheduler | Linear | Gradually decreases the learning rate linearly after the warm-up phase, which helps stabilize training as convergence is approached. |

| Optimizer | AdamW | An optimizer is responsible for updating model weights to minimize the loss. AdamW builds on the Adam optimizer by using adaptive learning rates and applying a regularization technique to help prevent overfitting. |

| Data Type | Mixed Data | Child-Only | Combined Clean |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kids Data | × | × | × |

| Kids Augmented | × | × | |

| Adult Data | × | × | |

| Adult Augmented | × | ||

| Hard to understand | × | × | |

| Total Samples | ~34,000 | ~21,000 | ~10,000 |

| Model | PER | WER | Data Size | Training Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Mixed Data | 28.7% | 89.1% | ≈25.5 h | 10 h 12 min |

| Model 2: Child-Only Data | 23.5% | 91.3% | ≈16 h | 6 h 17 min |

| Model 3: Clean Data | 14.3% | 31.6% | ≈7.5 h | 4 h 5 min |

| Model | PER | WER Trend | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clean Data | 11.8% | Below 30% | Best overall performance; steady learning; sharp WER drop once PER < 20%. |

| Child-Only Data | 25% | Moderate improvement | Fast early learning but plateaus; worse than clean data. |

| Mixed Data | 29% | High throughout | Slow learning; large dataset but augmentation not helpful; highest PER and WER. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ollmann, P.; Sonnleitner, E.; Kurz, M.; Krösche, J.; Selinger, S. Listen Closely: Self-Supervised Phoneme Tracking for Children’s Reading Assessment. Information 2026, 17, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010040

Ollmann P, Sonnleitner E, Kurz M, Krösche J, Selinger S. Listen Closely: Self-Supervised Phoneme Tracking for Children’s Reading Assessment. Information. 2026; 17(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleOllmann, Philipp, Erik Sonnleitner, Marc Kurz, Jens Krösche, and Stephan Selinger. 2026. "Listen Closely: Self-Supervised Phoneme Tracking for Children’s Reading Assessment" Information 17, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010040

APA StyleOllmann, P., Sonnleitner, E., Kurz, M., Krösche, J., & Selinger, S. (2026). Listen Closely: Self-Supervised Phoneme Tracking for Children’s Reading Assessment. Information, 17(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010040