Opinion Formation at Ising Social Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Data Sets and Model Description

3. Results

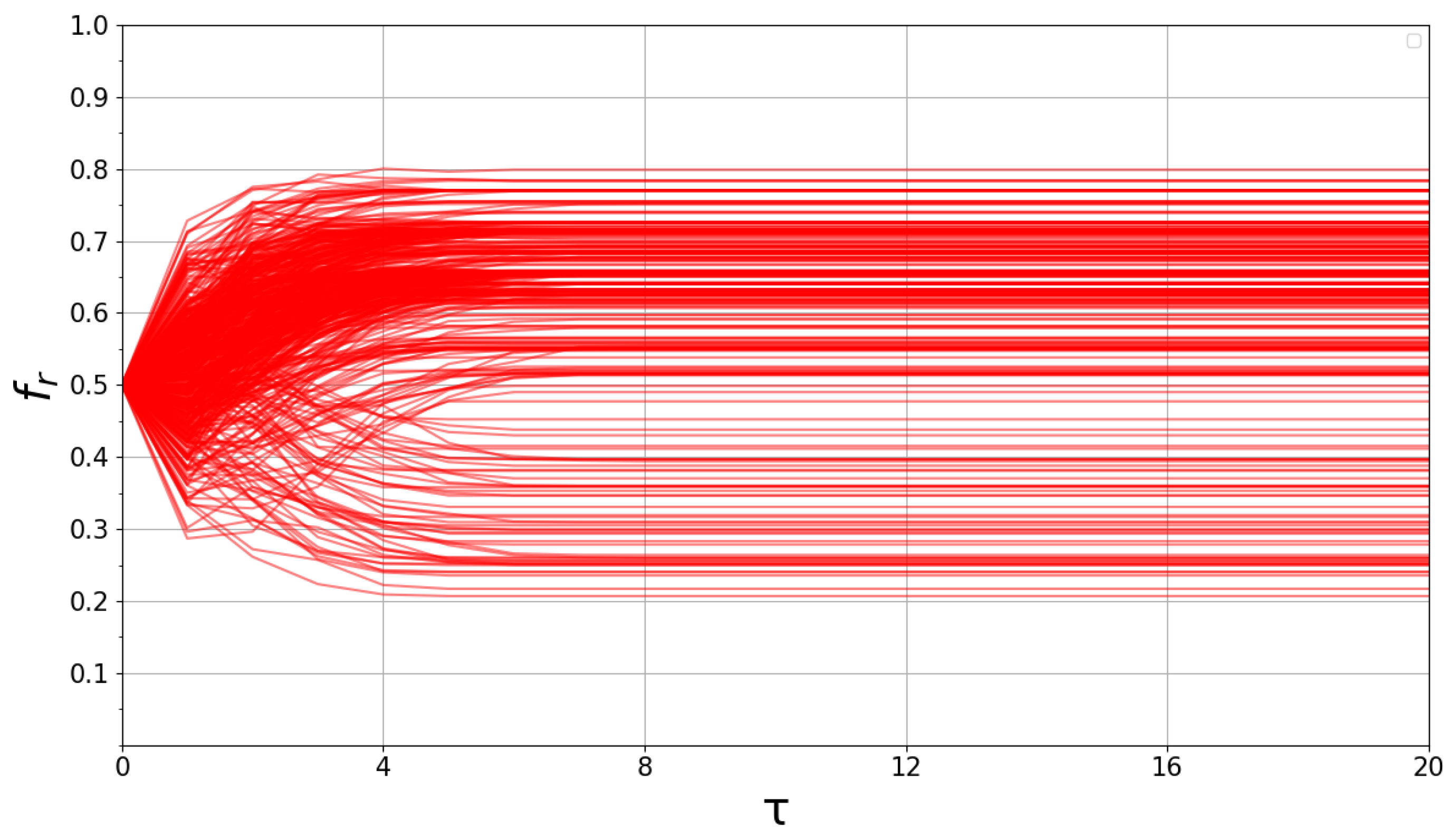

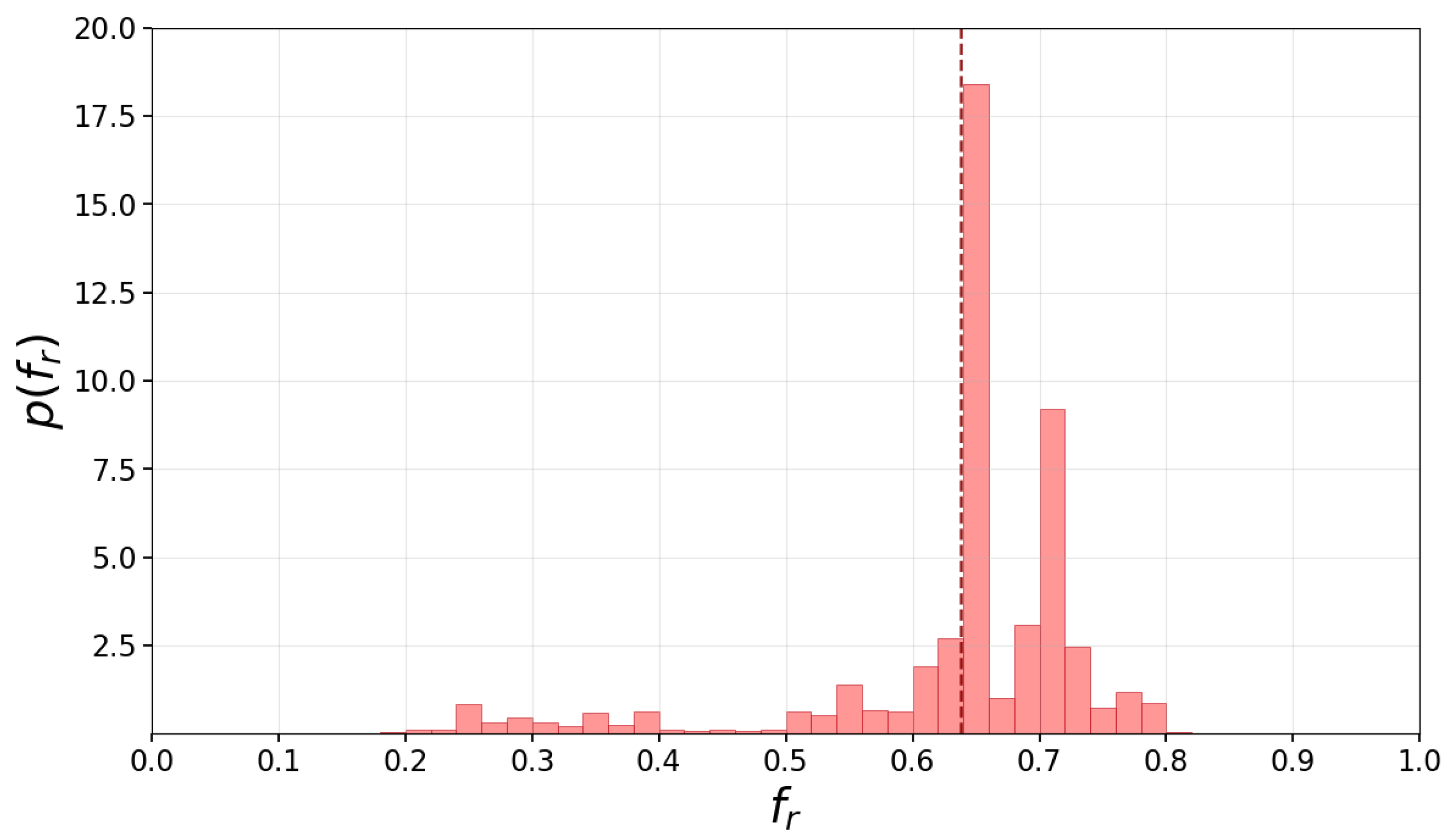

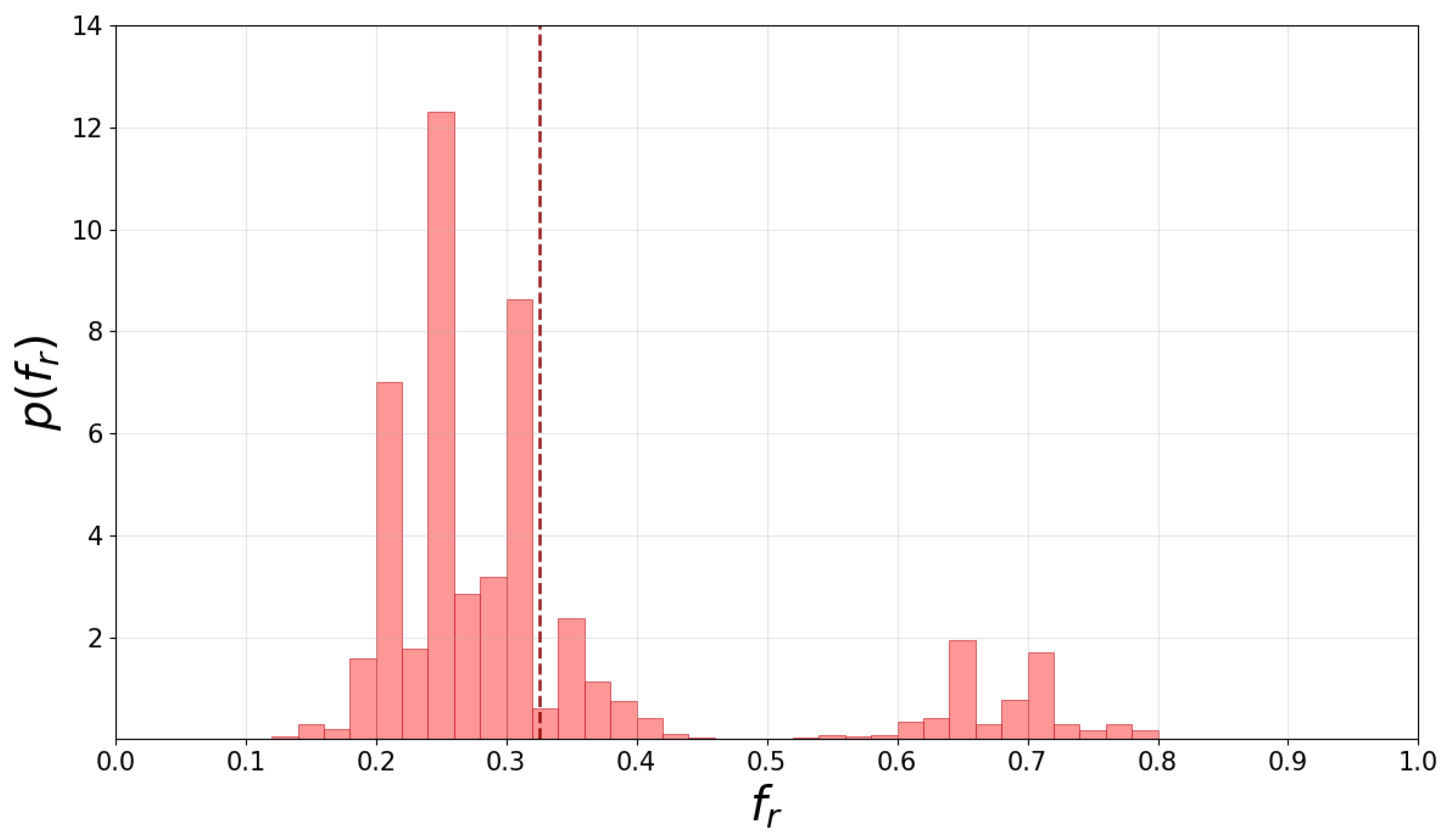

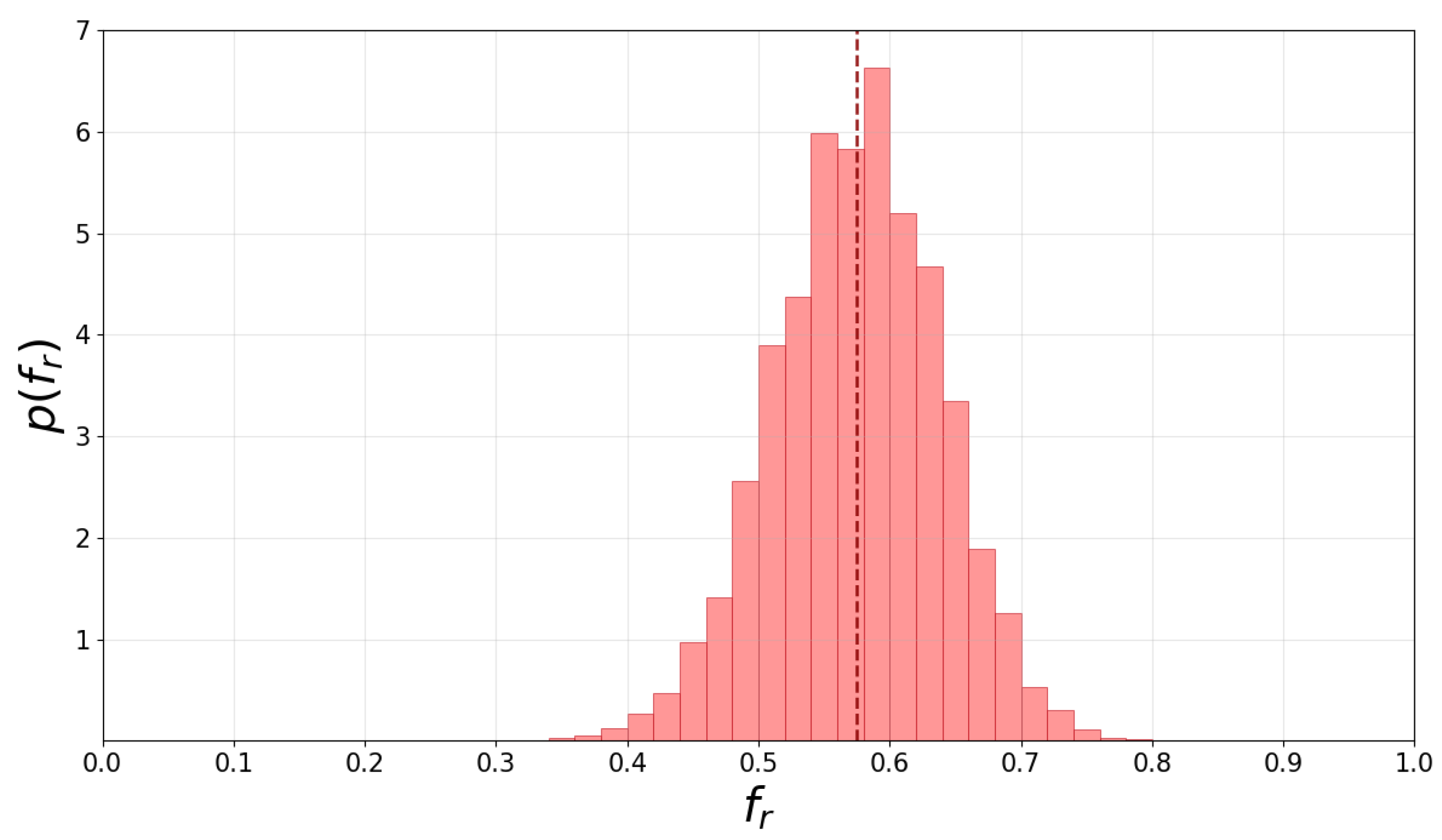

3.1. INOF Results with White Notes

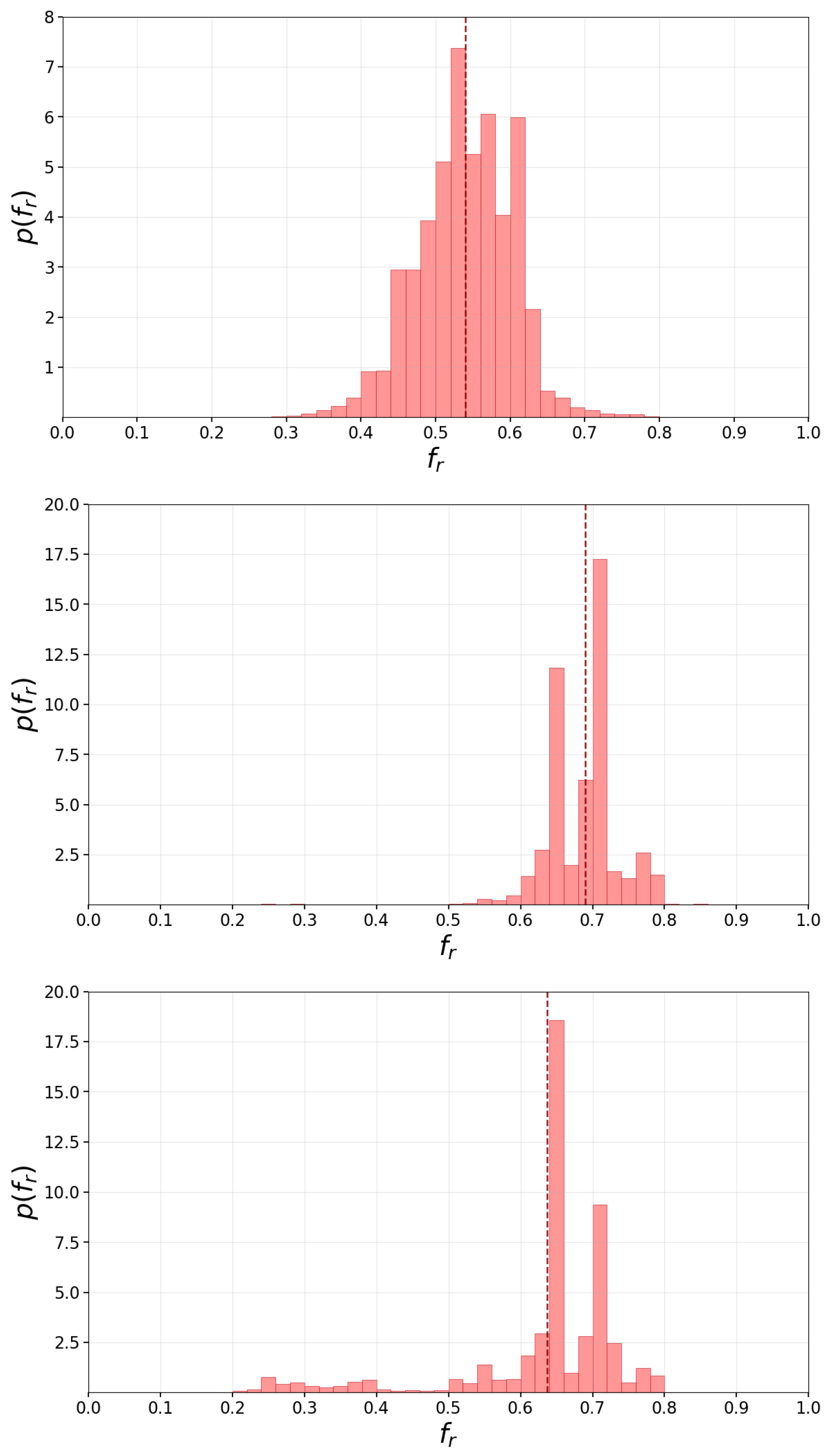

3.2. Effects of Opinion Conviction Threshold in GINOF

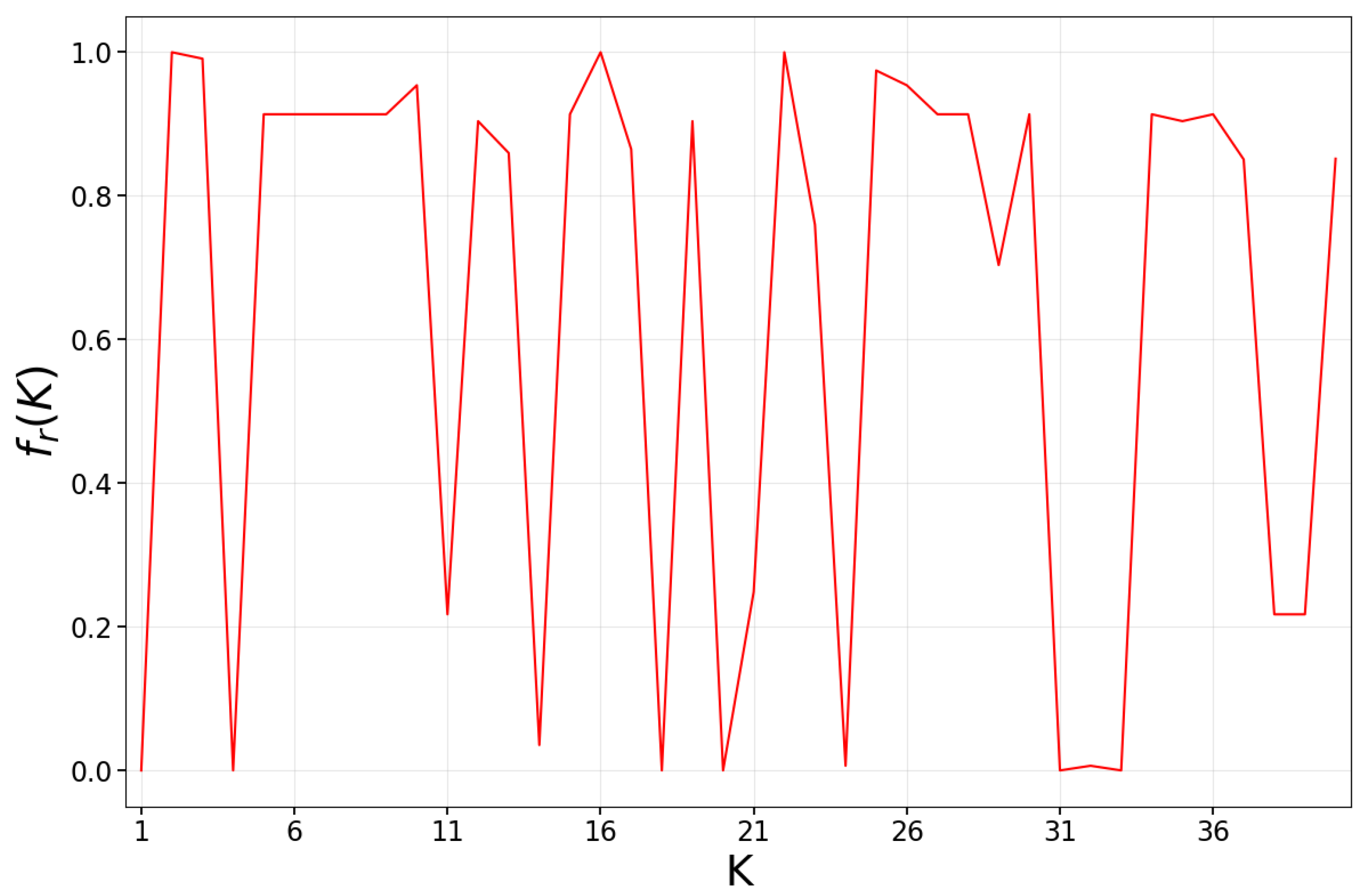

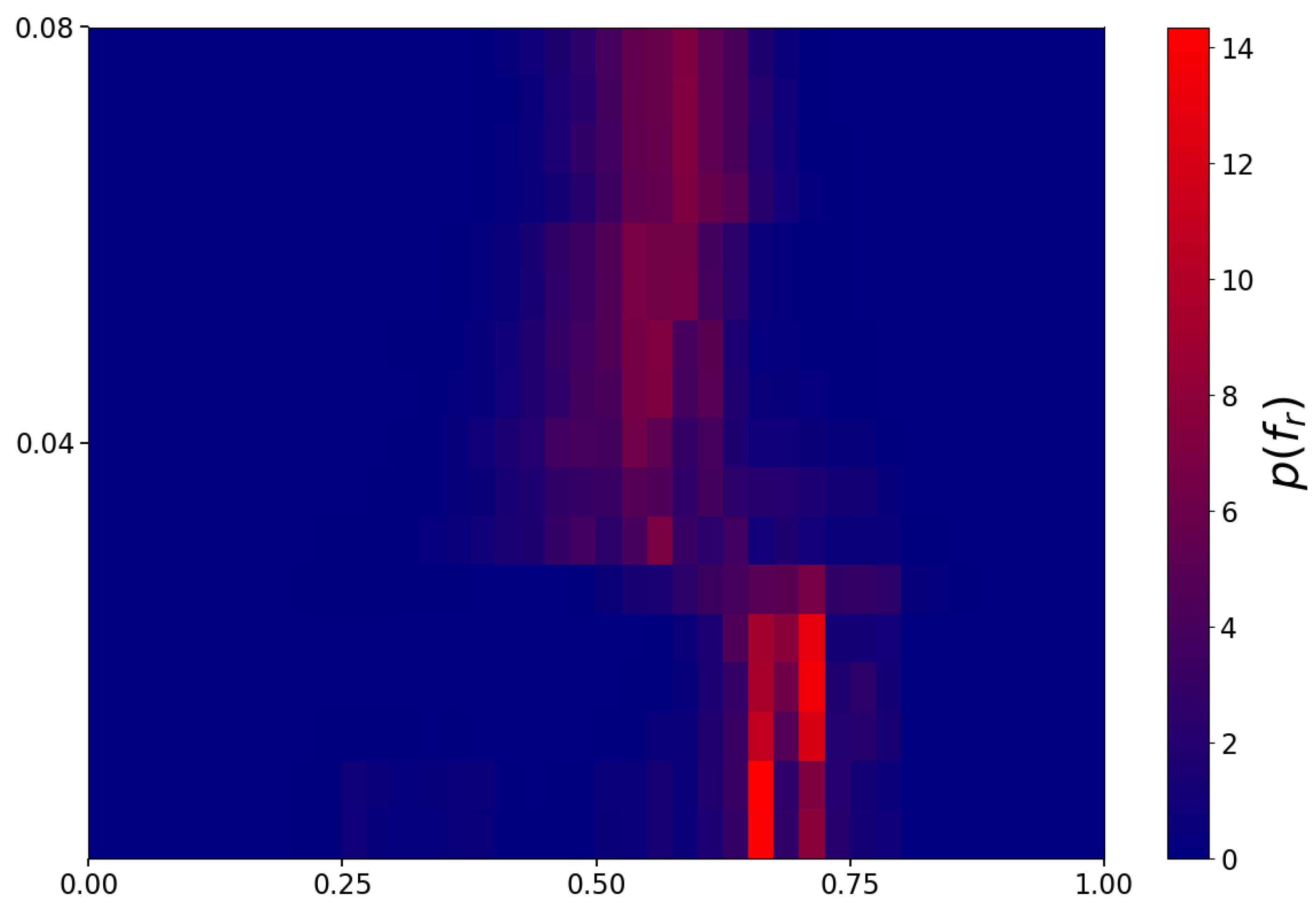

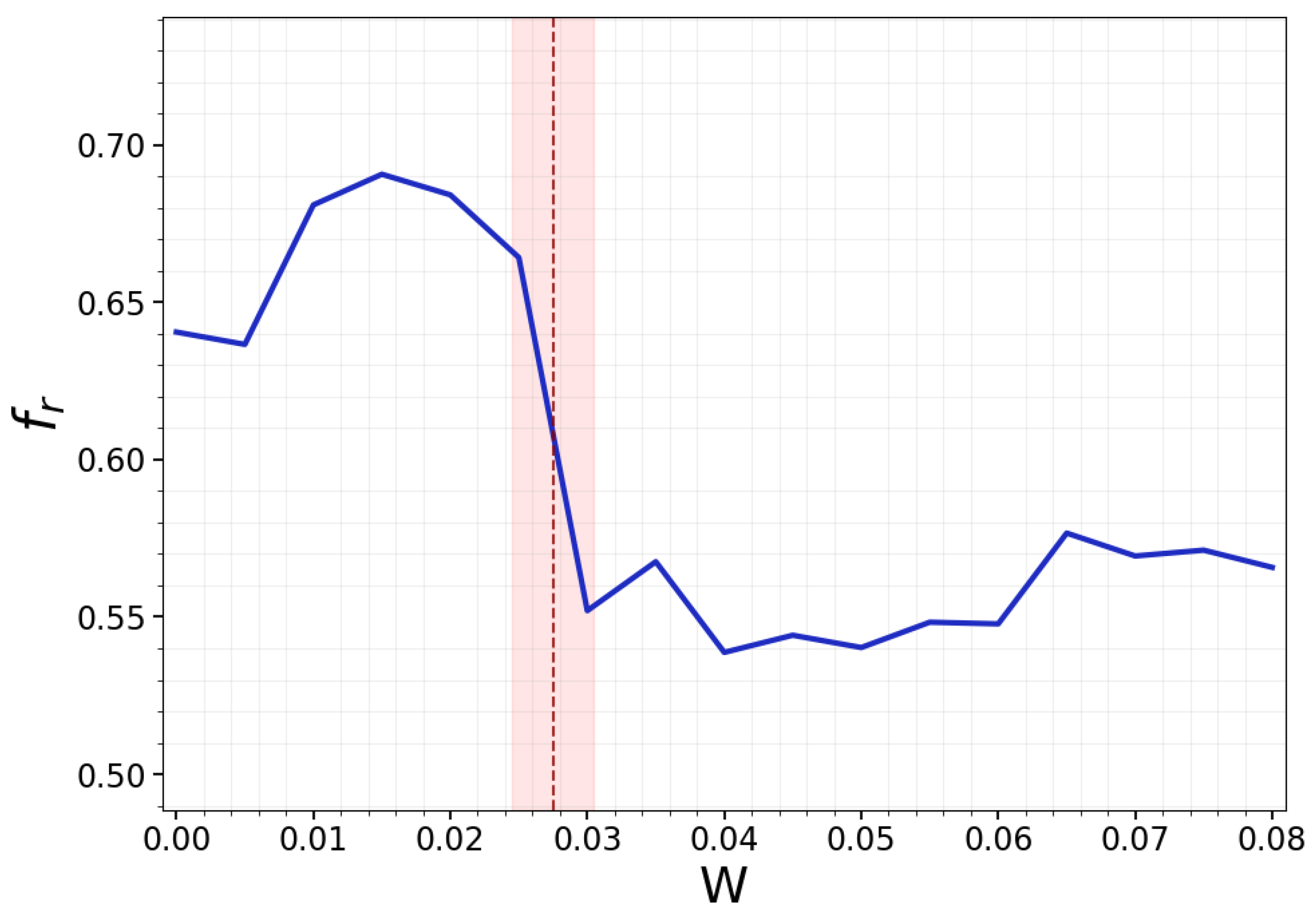

3.3. Phase Transition of Opinion Formation

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castellano, C.; Fortunato, S.; Loreto, V. Statistical physics of social dynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorogovtsev, S. Lectures in Complex Networks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, M. Networks; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia Contributors. Social Media Use in Politics. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_media_use_in_politics (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Fujiwara, T.; Muller, K.; Schwarz, C. The Effect of Social Media on Elections: Evidence from The United States. J. Eur. Economi Ass. 2023, 22, 1495–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galam, S.; Gefen, Y.; Shapir, Y. Sociophysics: A new approach of sociological collective behaviour. I. Mean-behaviour description of a strike. J. Math. Sociol. 1982, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galam, S. Majority rule, hierarchical structures, and democratic totalitarianism: A statistical approach. J. Math. Psychol. 1986, 30, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznajd-Weron, K.; Sznajd, J. Opinion evolution in closed community. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 2000, 11, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, V.; Redner, S. Voter Model on Heterogeneous Graphs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 178701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, D.J.; Dodds, P.S. Influentials, Networks, and Public Opinion Formation. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galam, S. Sociophysics: A review of Galam models. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 2008, 19, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandiah, V.; Shepelyansky, D.L. PageRank model of opinion formation on social networks. Phys. A 2012, 391, 5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopfield, J.J. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, M.; Carillo, L.; Marinari, E.; Mezard, M. Eigenvector dreaming. J. Stat. Mech. 2024, 013302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozum, J.C.; Campbell, C.; Newby, E.; Nasrollahi, F.S.F.; Albert, R. Boolean Networks as Predictive Models of Emergent Biological Behaviors; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastva, S.; Park, K.H.; Huvar, O.V.; Rozum, J.C.; Albert, R. An open problem: Why are motif-avoidant attractors so rare in asynchronous Boolean networks? J. Math. Biol. 2025, 91, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coquide, C.; Lages, J.; Shepelyansky, D.L. Prospects of BRICS currency dominance in international trade. Appl. Netw. Sci. 2023, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermann, L.; Frahm, K.M.; Shepelyansky, D.L. Opinion formation in Wikipedia Ising networks. Information 2025, 16, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorogovtsev, S.N.; Goltsev, A.V.; Mendes, F.F. Ising model on networks with an arbitrary distribution of connections. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 016104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, G. Mean field solution of the Ising model on a Barabási–Albert network. Phys. Lett. A 2002, 303, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J. Scientific collaboration networks. II. Shortest paths, weighted networks, and centrality. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 64, 016132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M.E.J. Finding community structure in networks using the eigenvectors of matrices. Phys. Rev. E 2006, 74, 036104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, M.E.J. Network Data. Available online: http://www.umich.edu/~mejn/netdata (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Newman, M.E.J. Community Centrality. Available online: http://www.umich.edu/~mejn/centrality (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Frahm, K.M.; Shepelyansky, D.L. Wealth thermalization hypothesis and social networks. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.17720. [Google Scholar]

- Langville, A.M.; Meyer, C.D. Google’s PageRank and Beyond: The Science of Search Engine Rankings; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, R.; Thakar, J. Boolean modeling: A logic-based dynamic approach for understanding signaling and regulatory networks and for making useful predictions. WIREs Syst. Biol. Med. 2014, 6, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Kessler, D.A.; Levine, H. Biological Networks Regulating Cell Fate Choice Are Minimally Frustrated. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 088101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frahm, K.M.; Kotelnikova, E.; Kunduzova, O.; Shepelyansky, D.L. Fibroblast-Specific Protein-Protein Interactions for Myocardial Fibrosis from MetaCore Network. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozemberczki, B.; Davies, R.; Sarkar, R.; Sutton, C. GEMSEC: Graph Embedding with Self Clustering. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.03997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Luo, F.; Gao, J. Networks with Ricci Flow. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 9984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galam, S. Spontaneous Symmetry Breaking, Group Decision Making and Beyond 2: Distorted Polarization and Vulnerability. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radicchi, F.; Fortunato, S.; Markines, B.; Vespignani, A. Diffusion of scientific credits and the ranking of scientists. Phys. Rev. E 2009, 80, 056103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegselmann, R.; Krause, U. Opinion dynamics and bounded confidence models, analysis, and simulation. J. Artifical Soc. Soc. Simul. (JASSS) 2002, 5, 1–33. Available online: https://jasss.soc.surrey.ac.uk/5/3/2.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Hegselmann, R.; Krause, U. Opinion dynamics under the influence of radical groups, charismatic leaders, and other constant signals: A simple unifying model. Netw. Heterog. Media 2015, 10, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, E.; Varsakelis, N.; Antoniou, I. Promoters versus Adversaries of Change: Agent-Based Modeling of Organizational Conflict in Co-Evolving Networks. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, C.A.; Glass, D.H. Social Influence of Competing Groups and Leaders in Opinion Dynamics. Comput. Econ. 2021, 58, 799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facebook. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- VK. Available online: https://vk.com/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- STRING. Available online: https://string-db.org/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bukina, K.; Shepelyansky, D.L. Opinion Formation at Ising Social Networks. Information 2026, 17, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010041

Bukina K, Shepelyansky DL. Opinion Formation at Ising Social Networks. Information. 2026; 17(1):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010041

Chicago/Turabian StyleBukina, Kristina, and Dima L. Shepelyansky. 2026. "Opinion Formation at Ising Social Networks" Information 17, no. 1: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010041

APA StyleBukina, K., & Shepelyansky, D. L. (2026). Opinion Formation at Ising Social Networks. Information, 17(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010041