Insights on the Pedagogical Abilities of AI-Powered Tutors in Math Dialogues

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- To what extent are a given dimension of analysis (e.g., linguistic, emotional, etc.) and its associated set of features useful to characterize the guidance provided by tutors in their responses to students? In other words, can pedagogically competent responses from tutors be distinguished along a specific dimension of analysis?

- RQ2:

- To what extent do the responses of LLM tutors differ in a certain dimension among themselves and with respect to human tutors?

2. Related Works

2.1. AI Tutors in the Math Domain

2.2. Pedagogical Aspects of AI Tutors

2.3. Evaluation of Pedagogical Aspects in AI Tutors

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Description

3.2. Analyzed Dimensions and Feature Extraction

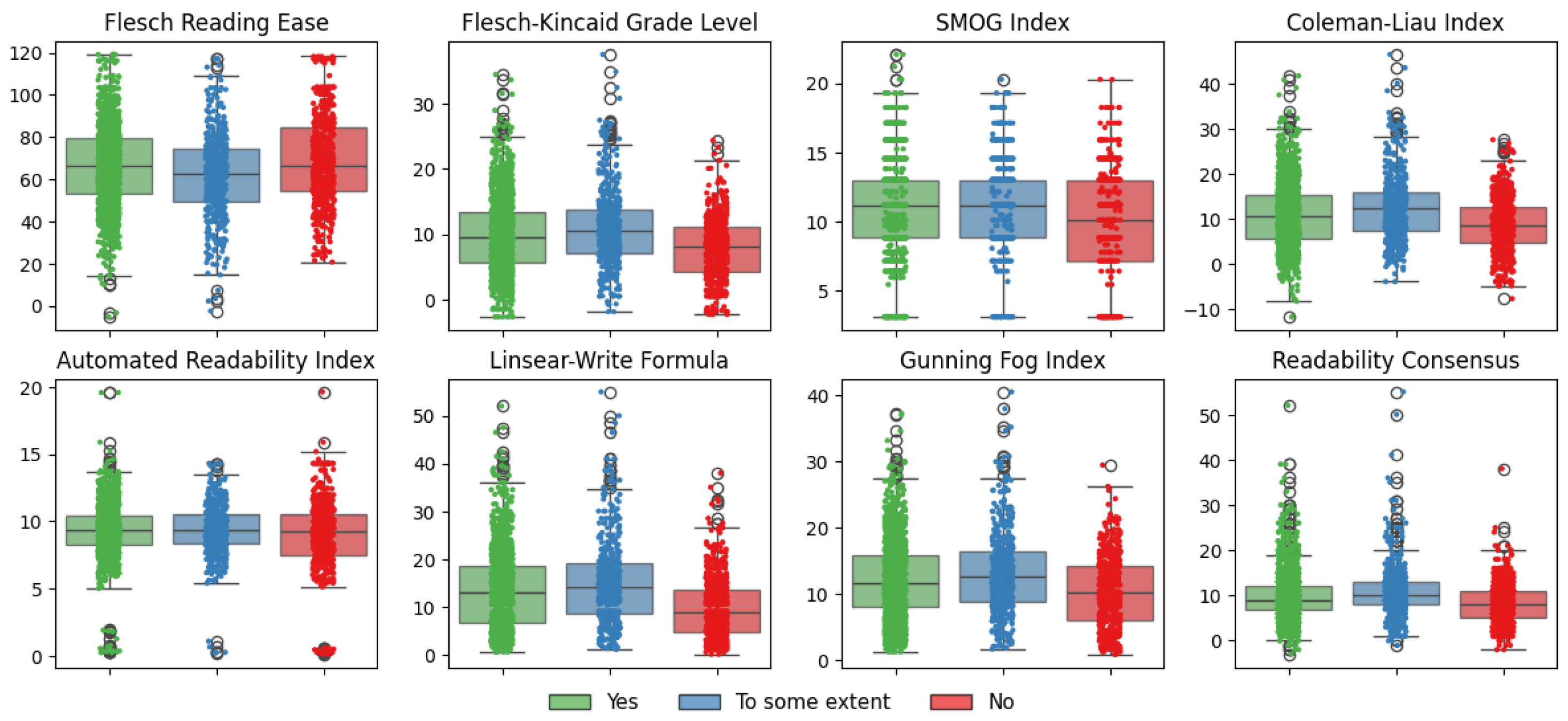

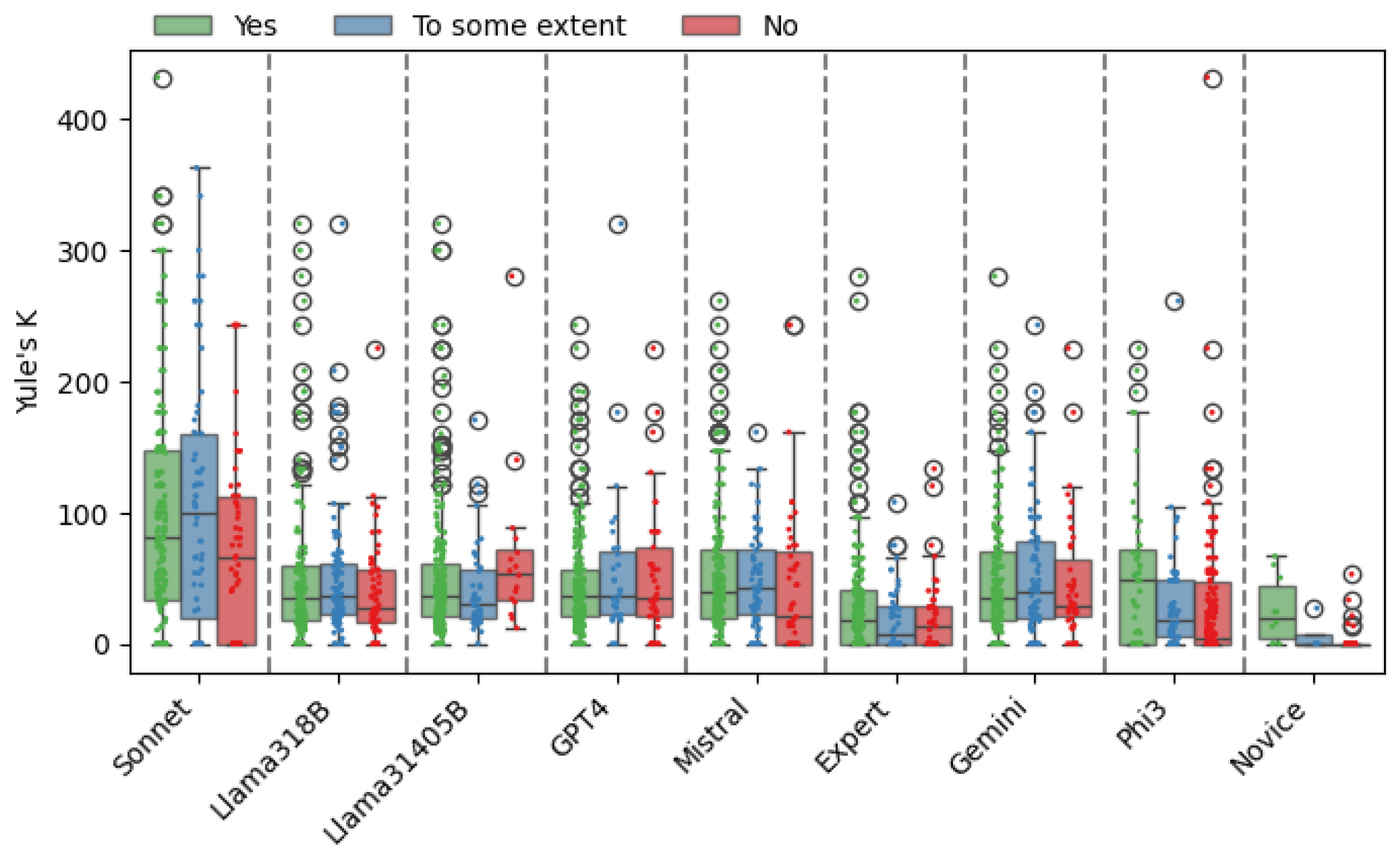

- Readability and lexical richness: these features are oriented to determine the level of difficulty and richness in the vocabulary of a tutor response. The examination of this dimension is grounded in the premise that tutors should provide answers understandable to students, taking into account their academic level and background. It aims to evaluate how the AI tutor performs with respect to the second principle of the taxonomy, namely adaptation to students’ goals and needs. The readability of a piece of text allows to determine its difficulty regarding the level of instruction needed to understand it. Different readability formulas are typically applied to texts to quantify this aspect, including the Flesch Reading Ease and Automated Readability Index (ARI), among others. Most readability formulas work by analyzing the length of sentences, syllables, or letters. Shorter sentences and words with fewer letters and syllables are considered simpler and easier to read. Additionally, the diversity of vocabulary employed in texts is a common parameter used as a proxy for establishing the level of language sophistication, starting from the information on the occurrences of unique words. In other words, the more unique words appearing in the text produced by a tutor, the higher the language sophistication it exhibits.

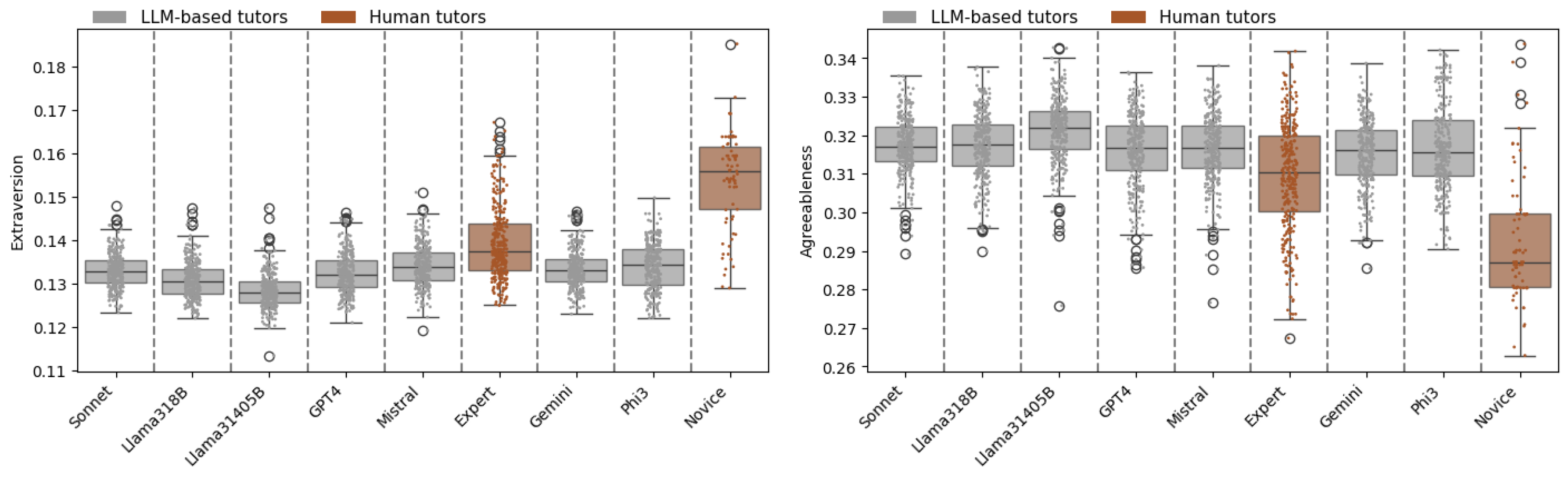

- Sentiment, emotions, and personality: these dimensions explore human-likeness of responses as effective tutoring requires that students feel a connection with the tutor, which is more likely when the responses appear human-like rather than robotic [3,7]. This dimension explores the four principles of the taxonomy, including how the AI tutor fosters motivation and stimulates curiosity. In order to extract features describing the behavior of LLM tutors in this dimension, we leverage several available lexicons and pre-trained models. Sentiment-related scores were extracted with VADER (Valence Aware Dictionary and sEntiment Reasoner) [31], a lexicon- and rule-based sentiment analysis tool. Emotions were obtained with EmoRoBERTa [32], a detection model based on the RoBERTa architecture and designed to identify 28 different emotional categories. Personality traits within the Big Five model (agreeableness, extraversion, openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism) were also analyzed based on the predictions of a pre-trained model.

- Coherence and uptake: this aspect highlights the alignment of the response with the ongoing dialogue between tutor and student; i.e., it is intended to determine whether the response effectively functions as a follow-up within the dialogue thread. According to [3,6], high-quality responses from tutors should be logically consistent with the student’s previous communications. Two principles of the taxonomy are associated with this dimension: encouraging active learning and managing cognitive load while enhancing metacognitive skills. To assess this coherence, we measure the similarity between the text of the response and the preceding dialogue, assuming that a semantic relationship should exist between them. Models for assessing textual semantic similarity were employed with this goal, both a general-purpose one as well as a math-specific one. Beyond overlapping and similarity, there is a more complex notion of uptake referring to how a teacher recognizes, interprets, and responds to a student’s contributions during instruction. For example, if a student provides a partial answer, teacher uptake is related to the ability to acknowledge the correct part and extend the explanation or reframe the question to enhance the learning experience. This interaction is fundamental for effective teaching as it reflects the responsiveness of teachers to the student’s process of thinking and understanding. For assessing this important factor in the interaction with tutors, a model specifically trained for predicting uptake in math dialogues was applied [33].The exploration of uptake was further complemented by observing the cognitive processes appearing in responses as defined by the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) [34], which include the presence of words related to insight, causation, discrepancy, differentiation, tentativeness, and certainty.

- RQ1.1/RQ2.1:

- To what extent do LLM-powered tutors adapt readability and lexical level to the targeted students, and how do they compare with human tutors?

- RQ1.2/RQ2.2:

- Can LLM-based tutors exhibit human-like characteristics that foster motivation and curiosity, and how do they compare with human tutors in this regard?

- RQ1.3/RQ2.3:

- How do LLM-based tutors manage uptake in dialogue to support active learning and the development of metacognitive skills?

4. Results

4.1. Readability and Lexical Richness

- RQ1:

- readability seems to be inversely proportional to the quality of the guidance that is provided. The difficulty in understanding an answer when it is a supportive one is higher, and it probably involves more mathematical terms and requires deeper reading and understanding. The results regarding lexical richness, on the other hand, despite showing some evidence that a richer vocabulary is used when better guidance is provided, remain inconclusive.

- RQ2:

- there is a notable difference in the readability of LLMs and human tutors, as can be deduced from the previous results. Both expert and novice tutors’ utterances are more readable and require less instruction to be understood regardless of whether they are providing high-quality guidance or not. This implies that, for the same dialogue, teachers can provide more adapted answers, fostering the student’s comprehension and, consequently, learning. In lexical richness, there is no noticeable difference between the two.

4.2. Sentiment, Emotions, and Personality

- RQ1:

- sentiment and emotion analysis offers a perspective of human-likeliness of AI-powered tutors. From the obtained results, it can be deduced that AI tutors tend to be positive on their interventions in every case. However, the need to indicate errors and offer adequate guidance drives them toward less positive writing. Likewise, emotions are generally positive, although they are less intense in responses that provide good guidance. This is also reflected in personality traits: responses that do not provide guidance display lower agreeableness and, more prominently, lower openness.

- RQ2:

- personality traits extracted from the responses of LLM-based tutors differ from those obtained from human tutors. LLMs exhibit similar scores across the two mentioned traits, whereas human tutors tend to be less agreeable and more extraverted in their responses. A possible explanation is that LLMs are trained and aligned to be user-pleasing, which may account for the consistency observed in their personality trait profiles. In contrast, the responses of human tutors tend to convey more authentic human-like personality features, distinguishing them from the more uniform LLM-generated responses.

4.3. Coherence and Uptake

- RQ1:

- Coherence, denoted by both the similarity between the ongoing dialogue (textual and math-related) and the uptake of the response, is a clear differential factor of answers providing guidance. Specifically, uptake appears to be a robust marker of answers that reflect attention to this pedagogical dimension. In addition, the appearance of differentiation and discrepancy, and to some extent tentativeness introduced by tutors, is indicative of answers intending to help students.

- RQ2:

- Human tutors also have distinguishable behavior in terms of uptake with respect to LLM-based tutors as they are more volatile in this aspect, showing greater variability and providing poor guidance when uptake is absent.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parra, V.; Sureda, P.; Corica, A.; Schiaffino, S.; Godoy, D. Can Generative AI Solve Geometry Problems? Strengths and Weaknesses of LLMs for Geometric Reasoning in Spanish. Int. J. Interact. Multimed. Artif. Intell. 2024, 8, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal Chowdhury, S.; Zouhar, V.; Sachan, M. AutoTutor meets Large Language Models: A Language Model Tutor with Rich Pedagogy and Guardrails. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM Conference on Learning @ Scale (L@S’24), Atlanta, GA, USA, 18–20 July 2024; pp. 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, K.K.; Srivatsa, K.A.; Petukhova, K.; Kochmar, E. Unifying AI Tutor Evaluation: An Evaluation Taxonomy for Pedagogical Ability Assessment of LLM-Powered AI Tutors. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 29 April–4 May 2025; pp. 1234–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Tack, A.; Piech, C. The AI Teacher Test: Measuring the Pedagogical Ability of Blender and GPT-3 in Educational Dialogues. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.07540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tack, A.; Kochmar, E.; Yuan, Z.; Bibauw, S.; Piech, C. The BEA 2023 Shared Task on Generating AI Teacher Responses in Educational Dialogues. In Proceedings of the 18th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2023), Toronto, ON, Canada, 13 July 2023; pp. 785–795. [Google Scholar]

- Macina, J.; Daheim, N.; Chowdhury, S.P.; Sinha, T.; Kapur, M.; Gurevych, I.; Sachan, M. MathDial: A Dialogue Tutoring Dataset with Rich Pedagogical Properties Grounded in Math Reasoning Problems. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023; pp. 5602–5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, Q.; Robinson, C.; Loeb, S.; Demszky, D. Bridging the Novice-Expert Gap via Models of Decision-Making: A Case Study on Remediating Math Mistakes. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 1: Long Papers), Mexico City, Mexico, 16–21 June 2024; pp. 2174–2199. [Google Scholar]

- Caccavale, F.; Gargalo, C.L.; Gernaey, K.V.; Krühne, U. Towards Education 4.0: The role of Large Language Models as virtual tutors in chemical engineering. Educ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 49, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Yoo, H.; Myung, J.; Kim, M.; Lim, H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, T.Y.; Hong, H.; Kim, J.; Ahn, S.Y.; et al. LLM-as-a-tutor in EFL Writing Education: Focusing on Evaluation of Student-LLM Interaction. In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Customizable NLP: Progress and Challenges in Customizing NLP for a Domain, Application, Group, or Individual (CustomNLP4U), Miami, FL, USA, 16 November 2024; pp. 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajala, J.; Hukkanen, J.; Hartikainen, M.; Niemelä, P. Call me Kiran—ChatGPT as a Tutoring Chatbot in a Computer Science Course. In Proceedings of the 26th International Academic Mindtrek Conference (Mindtrek ’23), Tampere, Finland, 3–6 October 2023; pp. 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, S.; Löffler, F.; Maciol, M.; Ridder, F.; Schmitz, M.; Spanagel, J.; Wienkamp, J.; Burgahn, C.; Schilling, M. Evaluating the Impact of Advanced LLM Techniques on AI Lecture Tutors for Robotics Course. In AI in Education and Educational Research; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Lieb, A.; Goel, T. Student Interaction with NewtBot: An LLM-as-tutor Chatbot for Secondary Physics Education. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA ’24), Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Reddig, J.; Calò, T.; Weitekamp, D.; MacLellan, C.J. Beyond Final Answers: Evaluating Large Language Models for Math Tutoring. In Artificial Intelligence in Education; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 323–337. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzadeh, S.I.; Alizadeh, K.; Shahrokhi, H.; Tuzel, O.; Bengio, S.; Farajtabar, M. GSM-Symbolic: Understanding the Limitations of Mathematical Reasoning in Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Learning Representations, Singapore, 24–28 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Xie, Y.; Hao, Z.; Wang, X.; Mallick, T.; Su, W.J.; Taylor, C.J.; Roth, D. A Peek into Token Bias: Large Language Models Are Not Yet Genuine Reasoners. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Miami, FL, USA, 12–16 November 2024; pp. 4722–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaee, P.; Mirzadeh, I.; Alizadeh, K.; Horton, M.; Bengio, S.; Farajtabar, M. The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.06941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chudziak, J.A.; Kostka, A. AI-Powered Math Tutoring: Platform for Personalized and Adaptive Education. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIED 2025), Palermo, Italy, 22–26 July 2025; pp. 462–469. [Google Scholar]

- Kestin, G.; Miller, K.; Klales, A.; Milbourne, T.; Ponti, G. AI tutoring outperforms in-class active learning: An RCT introducing a novel research-based design in an authentic educational setting. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, M.T.H.; Wylie, R. The ICAP Framework: Linking Cognitive Engagement to Active Learning Outcomes. Educ. Psychol. 2014, 49, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarlatos, A.; Liu, N.; Lee, J.; Baraniuk, R.; Lan, A. Training LLM-Based Tutors to Improve Student Learning Outcomes in Dialogues. In Proceedings of the Artificial Intelligence in Education, Palermo, Italy, 22–26 July 2025; pp. 251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Macina, J.; Daheim, N.; Hakimi, I.; Kapur, M.; Gurevych, I.; Sachan, M. MathTutorBench: A Benchmark for Measuring Open-ended Pedagogical Capabilities of LLM Tutors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.18940. [Google Scholar]

- Kochmar, E.; Maurya, K.; Petukhova, K.; Srivatsa, K.A.; Tack, A.; Vasselli, J. Findings of the BEA 2025 Shared Task on Pedagogical Ability Assessment of AI-powered Tutors. In Proceedings of the 20th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2025), Vienna, Austria, 31 July–1 August 2025; pp. 1011–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikal, B.; Basem, M.; Oshallah, I.; Hamdi, A. MSA at BEA 2025 Shared Task: Disagreement-Aware Instruction Tuning for Multi-Dimensional Evaluation of LLMs as Math Tutors. In Proceedings of the 20th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2025), Vienna, Austria, 31 July–1 August 2025; pp. 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Fu, X.; Liu, B.; Zong, X.; Kong, C.; Liu, S.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L.; Fan, H.; et al. BLCU-ICALL at BEA 2025 Shared Task: Multi-Strategy Evaluation of AI Tutors. In Proceedings of the 20th Workshop on Innovative Use of NLP for Building Educational Applications (BEA 2025), Vienna, Austria, 31 July–1 August 2025; pp. 1084–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. The Claude 3 Model Family: Opus, Sonnet, Haiku. Available online: https://www-cdn.anthropic.com/de8ba9b01c9ab7cbabf5c33b80b7bbc618857627/Model_Card_Claude_3.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Grattafiori, A.; Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; et al. The Llama 3 Herd of Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.21783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; et al. GPT-4 Technical Report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.06825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Georgiev, P.; Lei, V.I.; Burnell, R.; Bai, L.; Gulati, A.; Tanzer, G.; Vincent, D.; Pan, Z.; Wang, S.; et al. Gemini 1.5: Unlocking multimodal understanding across millions of tokens of context. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.05530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdin, M.; Aneja, J.; Awadalla, H.; Awadallah, A.; Awan, A.A.; Bach, N.; Bahree, A.; Bakhtiari, A.; Bao, J.; Behl, H.; et al. Phi-3 Technical Report: A Highly Capable Language Model Locally on Your Phone. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.14219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, C.J.; Hutto, E. VADER: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM-14), Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, R.; Ghoshal, A.; Eswaran, S.; Honnavalli, P. An Enhanced Context-based Emotion Detection Model using RoBERTa. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies (CONECCT), Bangalore, India, 8–10 July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demszky, D.; Liu, J.; Mancenido, Z.; Cohen, J.; Hill, H.; Jurafsky, D.; Hashimoto, T. Measuring Conversational Uptake: A Case Study on Student-Teacher Interactions. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers), Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 1638–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennebaker, J.W.; Francis, M.E.; Booth, R.J. Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count: LIWC 2001; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahway, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dubay, W. Smart Language: Readers, Readability, and the Grading of Text; Impact Information: Costa Mesa, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Collins-Thompson, K. Computational assessment of text readability: A survey of current and future research. ITL—Int. J. Appl. Linguist. 2014, 165, 97–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, P.M.; Jarvis, S. vocd: A theoretical and empirical evaluation. Lang. Test. 2007, 24, 459–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong Wang, K.S. Continuous Output Personality Detection Models via Mixed Strategy Training. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.16223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, N.; Gurevych, I. Sentence-BERT: Sentence Embeddings using Siamese BERT-Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Hong Kong, China, 3–7 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeldt, C.; Mihaljević, H. Evaluation and Domain Adaptation of Similarity Models for Short Mathematical Texts. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Intelligent Computer Mathematics (CICM 2024), Montreal, QC, Canada, 5–9 August 2024; pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajja, R.; Sermet, Y.; Cwiertny, D.; Demir, I. Integrating AI and Learning Analytics for Data-Driven Pedagogical Decisions and Personalized Interventions in Education. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 2025; online first. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Parra, V.; Corica, A.; Godoy, D. Insights on the Pedagogical Abilities of AI-Powered Tutors in Math Dialogues. Information 2026, 17, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010051

Parra V, Corica A, Godoy D. Insights on the Pedagogical Abilities of AI-Powered Tutors in Math Dialogues. Information. 2026; 17(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleParra, Verónica, Ana Corica, and Daniela Godoy. 2026. "Insights on the Pedagogical Abilities of AI-Powered Tutors in Math Dialogues" Information 17, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010051

APA StyleParra, V., Corica, A., & Godoy, D. (2026). Insights on the Pedagogical Abilities of AI-Powered Tutors in Math Dialogues. Information, 17(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/info17010051