Generating Sacred Space beyond Architecture: Stacked Stone Pagodas in Sixth-Century Northern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

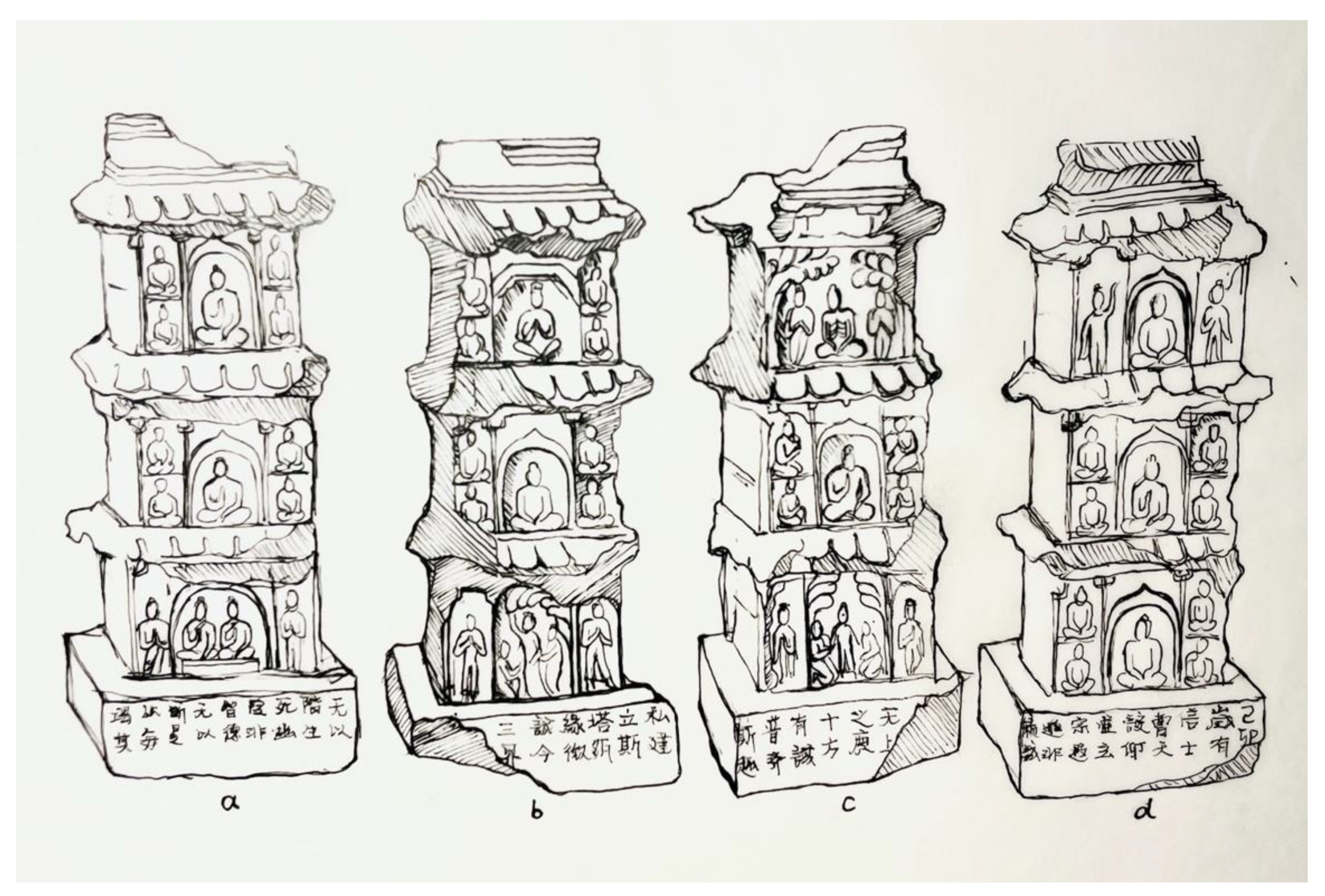

2. Stacked Pagodas from Gansu and Shanxi

2.1. Gansu

2.2. Shanxi

2.3. Between Gansu and Shanxi

3. Architectural Elements in Absence, Buddhist Imagery in Presence

4. Pictorial Programs on Stone Pagodas of the Northern Dynasties

5. Individual Image, Collective Patronage

6. Dissolving the Structure: From Multilevel Pagoda to Stone Image

7. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Regarding the region’s history of Buddhism and the role played by ethnic groups, see Hou Xudong (Hou 2008); Wei and Wu (2009); Song (2009); Gansu Beishikusi Wenwu Baohu Yanjiusuo (2013); Zheng et al. (2014); Wang (2015). Eastern Gansu and the bordering Shaanxi has formed an important center since the fourth century, where Buddhism flourished during the rule of the non-Han Chinese dynasties, including the Former Qin 前秦 (351–394), Later Qin 後秦 (384–417), and Xiongnu Da Xia 匈奴大夏 (407–431) before the Northern Wei’s capture of Chang’an. For the area’s history and its non-Han culture, see (Ma 1985). |

| 2 | The discussion on the initial appearance of stūpas is vast. See (Hawkes and Shimada 2009; Fogelin 2012, 2015). |

| 3 | Each of “stūpa” and “pagoda” has a broader reference and a more contested history of use in various research contexts. The terminological ambiguity has persisted through the field over the past century. To avoid ambiguity, this study uses pagoda to refer to multistory structures whereas stūpa refers to all other forms. The last section in this introduction will provide a more detailed discussion of the terminology. For related discussion, also see Miu (2012), Miller (2014), Mukai (2020). Meanwhile, a second-century relief carving of a multistory structure from Sichuan is considered by scholars as one among the earliest depictions of pagoda. See Xie (1987). |

| 4 | They are usually named “stūpa” due to the hemispherical dome. |

| 5 | |

| 6 | It has been preserved in the Chongfu 崇福 Monastery in northwest Shanxi, but was originally commissioned at Pingcheng, the capital city of Northern Wei. Its pedestal and tower body were taken to Japan during World War II and later returned to Taiwan after the war, while the ornamental top was preserved by a local person in Shuozhou. See (Shi 1980; Wang 2011b). |

| 7 | At the Nannieshui Museum, a stone piece with a roof imitating wooden structure is placed on top of a stacked pagoda. Yet it remains uncertain how universal this practice is, without any more similar pieces located. |

| 8 | For instance, the inscription found on a stone block from Xiejiamiao in eastern Gansu reads, “永熙三年太歲在寅八月十四日弟子/縣張生德為忘息大奴敬/造石佛圖三劫願上生天上/諸佛下生人間口王長壽若/三速令解脫善願從心” (On the fourteenth day of the eighth month, the third year of the Yongxi era [the year of the Tiger], Zhang Shengde from the county of ... dedicated a three-story stone pagoda for his deceased Danu for his ascension into the heaven…Buddhas descend to the mundane world…longevity…achieve emancipation from…to follow what the heart desires…) The stacked pagoda that this stone block belongs to dates 534, Northern Wei. There is no archaeological report, but a general overview, on the group of statues found in the Xiejiamiao site ever published. Current studies weigh on the ethnic group of the donors for this group. See (Wang 2015, 2016; Zhang 2000, pp. 108–12). |

| 9 | The difference between the three words is generally attributed to the distinctive strategies of translation used between the third and the eighth century. Both futu 浮屠 and futu 浮圖 are used to refer to the Buddha in early Chinese historical texts, denoting an interchangeable relationship between the Buddha and the sacred structure. The usage is considered a result of phonetic confusion caused by the transliteration of Sanskrit phrases. In Hou Han shu 後漢書, futu is described as miraculous images that appear together with Laozi 老子, the indigenous saint who later became a quasi-deity of Daoism. Additionally, both futu and Laozi are housed in ci 祠 or miao 廟, which both refer to a ritual shrine in Chinese. See (Hou Han shu 1984, p. 16). For recent studies of the three terms’ literal meanings, see (Greene 2018). |

| 10 | Miniature pagodas and pagoda reliefs have been examined as evidence for the study of early Chinese architectural history in almost all major studies in the field. These studies contributed to many aspects, but their discussion on these miniatures and pagoda images is in the form of an overview. For major works, see (Liang 1961, 1962; Ledderose 1980; Seckel 1980; Sun 1984; Xiao 1989; Wang 2011a; Steinhardt 2011, 2014, 2019). In recent years, we have also seen discussions focusing on miniatures; however, the discussion is still confined in the scope of developing a typological system based on their structural traits (Wang 2006; Tang 2016; Xu 2016). Further studies in light of the study of Chinese miniatures in other forms and recent theoretical discussion of miniaturization is much needed. See (Ledderose 1983, 2000; Stein 1990; Steward 1993; Selbitschka 2005; Guo 2010; Hong 2015; Wu 2015; Luo 2016; Graves 2018; Martin and Langin-Hooper 2018; Davy and Dixon 2019; Elsner 2020). |

| 11 | To employ the term “hybridity,” some clarification should be made in response to recent scholarly discourse on the topic in the field of archaeology. Scholars have rectified the perception of hybridity by examining the issue of receptivity. See Stockhammer (2013), Andreeva (2018). To summarize within the scope of this footnote, this research confines the definition of hybridity within the scope of specific styles and motifs that have been developed and transmitted in northern China, as displayed by major Buddhist artworks. It agrees with the strand of scholarship that challenges the narrative of uninterrupted transmission of dominant styles and motifs in provincial areas. Rather, this study showcases the complexity about the way how styles and motif of various origins were combined unevenly in subordinate regions in sixth-century northern China. |

| 12 | From the east to the west, five of the seven counties of Pingliang are Lingtai 靈台, Jingchuan 涇川, Chongxin 崇信, Huating 華亭, and Zhuanglang 莊浪, all of which boast several Buddhist cave-temples as well. See (Gansu Sheng Wenwu Gongzuodui and Qingyang Bei Shiku Wenwu Baoguansuo 1987; Zhang 1994; Cheng 1998, p. 41; Dong 2008). |

| 13 | See footnote 1. |

| 14 | A total number of 209 cave-temples are carved out of the cliffs, dated from the Later Qin and Western Qin of the Sixteen States to the Tang dynasty. See (Yan 1984; Wei 2005; Gansu Sheng Wenwu Gongzuodui 1987; Steinhardt 2014, pp. 90–92). |

| 15 | The 503 stone block’s inscription reads, “景明四年太/歲在癸未/太陰在/巳大將軍/在午白虎/在寅青龍/在子四月癸馬” (In the fourth month of the fourth year of the Jingming era, the year at Guiwei and the lunar cycle at Si, the Great General is in the year of the Horse, the White Tiger in the year of the Tiger, the Dragon in the year of the Rat, the fourth month…Kui…Horse…) See (Zhang 2000, pp. 98–104; Gansu Sheng Wenwu Ju 2014, pp. 58–59). |

| 16 | Its inscription reads, “延昌三/年十五日/亥/涇州郡” (The third year of the Yanchang era…the fifth day…the year of the Pig…Jingzhou Prefecture…). See (Zhang 2000, p. 101). |

| 17 | Its inscription reads, “神龜元…孫亡…天上亡…” (The first year of the Shengui era…Sun…deceased…deceased in the heaven). See (Zhang 2000, p. 102). |

| 18 | The earliest identified Twin Buddhas motif is found in Cave 169 of the Binglingsi 炳靈寺 Cave-temples in Gansu. Cave 169 was commissioned during the Western Qin 西秦 Dynasty (385–431 CE) in the early fifth century. In the scene, two Buddhas are sitting side by side below a niche, above which three chattra-like elements protruding upwards. It was thus considered the earliest representation of the Twin Buddhas concept and of the “Jeweled Stūpa” chapter from the Lotus Sūtra. Yet the motif was not depicted frequently until the 470s. See, among many other sources, (Davidson 1954; Wong 2004, chp. 8; Wang 2005, chp. 1; Hurvitz 2009; Williams 2009). |

| 19 | Huating has been an important regional economic hub along the Silk Road. The pit’s location matches the historical site of a temple of the Northern dynasties. There is no archaeological report, but a general overview, on the group of statues found in the Xiejiamiao site ever published. Current studies weigh in on the ethnic group of the donors for this group. See (Zhang 2000, pp. 108–12; Wang 2016). |

| 20 | The inscription of the 516 piece reads, “熙平元年/太歲/在申/為張/何迥/張雙/清信士供養河門/大小/張永/奴//河門大小/者得” (On the first year of the Xiping era, the year of Shen, this…is dedicated to Zhang Hejiong, Zhang Shuang, men of pure faith…Zhang Yongnu of Hemen…to follow what the heart desires…from Hemen…) See (Wang 2016, Figure 1). That of the 558 piece reads “二年歲次戊寅六月癸寅朔十七日己丑清/信弟子路为夫长功曹南从/中敬造石像一區愿三涂地/愿一切众生龙花三会得成佛道所/所愿从心/佛弟子安家大小常住三宝” (On the seventeenth day [jichou], of the sixth month [guiyin], the second year [wuyin], Lu Weifu, a man of pure faith…dedicated a stone image…Samadhi…Wish all the beings achieve the Buddhahood…to follow what the heart desires…the Buddhist disciple…) See (Zhang 2000, p. 110; Gansu Sheng Wenwu Ju 2014, pp. 55–56). |

| 21 | Su Bai has discussed this feature briefly. In addition to examples from Longmen and Gongxian, a statue from the White Horse Temple of Luoyang also features the Buddha’s right foot in the manner. It is on display in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. See (Su 1996, pp. 153–76). |

| 22 | For more Zhuanglang pieces that are not examined in this section, see (Zhang 2000, p. 107; Gansu Sheng Wenwu Ju 2014, pp. 48–49, 51–52; E and Yang 2014a, 2014b). |

| 23 | One of the five stone blocks was found in the first half of the twentieth century while the other four were discovered in 1974. See (Cheng and Ding 1997; Zhang 2000, pp. 113–24; Wang 2004; E 2011; Gansu Sheng Wenwu Ju 2014, pp. 49–50). |

| 24 | See (Ding 2016, pp. 68–69). Another piece, brought to the US by the expedition of Warner in 1923, is currently in the repository at the Fogg Museum, Harvard. On Warner’s expedition, see (Warner 1926; Jayne 1929; Liu 2000). Jayne’s work was translated into Chinese by Liang Xuping. See also (Wang and Mrozowski 1990; Ding 2016, p. 74). |

| 25 | See footnote 2. |

| 26 | A record of the original excavation is helpful in exploring the original purpose of these hoarding pits. For instance, the excavation of hoarding pits located in Qingzhou, Shandong, shows that the statues and steles had been deposited in the pit in several layers, with the well-preserved items in the center, and fragments in the surrounding area. See (Nickel 2002, p. 35). |

| 27 | The period of Eastern Wei is not specified here due to its short life. Works produced during the Eastern Wei are usually grouped with the Northern Wei or the Northern Qi based on stylistic affinity. |

| 28 | On the origin of the Lushui hu, see (Tang 1955; Zhou 1963, pp. 156–57; Wang 1985; Zhao 1986; Wang 1997; Hou 2008; Liu 2008, pp. 9–11). |

| 29 | This study does not agree with any absolute reconstruction of the way in which each side of the five stone blocks is aligned. However, for convenience of discussion, I refer to each side based on the way the pagoda is currently displayed. |

| 30 | The Gandhāran tradition depicts the horse at center with the prince standing aside in ordinary royal dress, while the prince of northern China is featured dominantly in the conventional look of a pensive figure, who has one leg pendant and the other raised and brought across to rest upon the knee of the pendant leg, and with one arm raised towards the face. The Great Departure scene appears first in reliefs at Yungang in the 490s among fifteen other narrative episodes of the Buddha’s life story. There are sixteen scenes depicting episodes related to the Buddha’s birth on the central pillar of the Yungang Cave 6, and another set of sixteen on the lower register of the interior walls in the main chamber. |

| 31 | The motif is noticeably absent from any other stone works in the fifth century, indicating intentional neglect of it. For a comprehensive discussion of the Parinirvāṇa scene in Chinese Buddhist art tradition, see (Lee 2010, introduction, pp. 38–42, Figure 1.15). |

| 32 | The Chinese examples are not depicted in association with any other events of the Buddha’s life, departing from the South Asian and Central Asian traditions, in which the Parinirvāṇa image is always represented together with other episodes of the Buddha’s life story. |

| 33 | John S. Strong has translated the text’s surviving Sanskrit version to English. See (Strong 1983). |

| 34 | According to Victor Meir, the original text that the Xianyu jing was translated from has a Central Asian origin. Xianyu jing 賢愚經 (The Sutra of the Wise and the Foolish), trans., by Hui Jue 慧觉 et al. T no. 4: 202.368c. See (Junjirō 1901; Mair 1993). |

| 35 | Caves 5–11, 5–38, 25, 28, 29, 33, 33–34, and 34. For an overview of the story depicted in Yungang cave-temples, see (Yi 2017, chps. 5 and 6). For an example, see (Yungang Shiku Wenwu Baoguansuo 1991, Figure 197). |

| 36 | Hu Wenhe has provided a comprehensive discussion of the story. See (Hu 2005; Yi 2017, chp. 3). Regarding the narrative scenes carved on figured steles, Li Jingjie proposed a different identification of the scene. He argues for a representation of the Dīpaṃkara Jātaka instead of the offering dust story, according to several surviving inscriptions that point out the connection between the Buddha Dīpaṃkara and the children (儒童). See (Li 1996). |

| 37 | There are a series of research examining the pensive Buddha image in the fifth and the sixth century. This essay will not go into details. See (Rei 1975; Leidy 1990; Lee 1993; Hsu 2002). |

| 38 | The study of Nannieshui materials with Gephi was undertaken by the author in the workshop “Social Network Analysis in Buddhist Studies,” organized by “From the Ground Up” project in August 2018, National Singapore University. A more detailed discussion is forthcoming. For more discussion about using Gephi in the study of Buddhism, see (Bingenheimer 2020). |

| 39 | The Cao Tiandu Pagoda is also known for its turbulent history of displacement. Its base and body were looted from China and brought to Japan; later it was returned to Taiwan, now in preservation at the National Museum of History in Taipei. The chattra top was saved by a local person during the war and returned to Chongfu Monastery in 1953. |

| 40 | The county borders with the Pingcheng area and, throughout history, has been included in the Northern Shanxi cultural sphere. The Yu county belongs to the Kingdom Dai 代 in the fourth century, the precedent of Northern Wei. See (Yuxian Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui 1995; Huang 2015). |

| 41 | This claim is further affirmed by the absence of the Han mode of dresses that developed and entered the scene of the Pingcheng Buddhist art in the late 480s. The Han mode is a new dress style that features Sinicized traits, such as loose robes and wide girdles (baoyi bodai 褒衣博帶). It echoes the Sinicization reform in clothing promoted by Emperor Xiaowen 孝文 during the Taihe 太和 era (486–495). During the Taihe period, the “Era of Supreme Harmony,” Emperor Xiaowen and his court instituted a series of reforms that integrate intensively historical Chinese administrative institutions, rituals, urban design, etc. One of the defining features of this process is Hanhua, “becoming like the Han,” revealing the very nature of refashioning the Xianbei Northern Wei regime as an imperial Chinese dynasty. See (Bachhofer 1946, p. 66; Okada and Ishimatsu 1993, pp. 181–203; Abe 2002, p. 89). |

| 42 | The pagoda is preserved and on display in the recently founded Museum of Northern dynasties. It is said to be discovered at a local construction site. Yet no archaeological report is available at this moment. |

| 43 | It was first mentioned in the initial report on the discovery of the monastery in 1954. Yet it was reported stolen in 2000. See (Li 2008b). |

| 44 | For a proposed chronology of the three stone pagodas under discussion, see (Zhao 2020). |

| 45 | The Twin Buddhas motif signifies that more than one Buddha can exist at the same time in the cosmos. This is a new Mahāyāna theme, as early Buddhists believe there is only one Buddha in each age. See (Liu 1958; He 1992; Mizuno and Nagahiro 1951–1956, vols. 8 and 9, pp. 73–75). |

| 46 | For a detailed examination of narrative scenes on the miniature pagodas, see (Zhao 2020). |

| 47 | The Cao Tianhu pagoda was excavated in present-day Jiuquan 酒泉, Gansu province. The inscription on its pedestal records that it was commissioned in 499 by a local person named Cao Tianhu. Jiuquan is part of the east-west corridor of the Hexi region. The name exhibits a resemblance to Cao Tiandu of Pingcheng. Yet no further evidence shows connections between the two. Except for Chen Bingying’s description, the Cao Tianhu Pagoda has not been studied beyond a brief report. See (Chen 1988). |

| 48 | A similar arrangement is also found on a pagoda fragment preserved in the Palace Museum in Beijing. See (Li 1986). |

| 49 | |

| 50 | However, the epigraphic inscriptions of the pagodas of 514 and 518 are severely worn, leaving the donors’ identities unrecognizable. |

| 51 | Another factor to be considered in the study of this statue is the ethnic background of the local laity. The surnames of most of the donors may indicate their “Hu” identity. Yet the scarcity of textual records is not sufficient to support further discussion. See (Wang 2016). |

| 52 | There are two on the upper register and three on the lower. From left to right, the upper two are “deceased father Bu Waitong” 亡父卜外通 and “deceased mother Le Baozhu” 亡母樂保朱, while the lower three are “general Bu yong” 上將卜永, “deceased brother Bu An” 亡雄卜安, and “deceased sister Bu Yonghe” 亡妹卜永禾. |

| 53 | For a discussion of the procession scene on steles from Shanxi, see (Wong 2004, chp. 5). Such a unique way nevertheless reminds us of a parallel tradition in Chinese funerary art, which depicts exactly the deceased, or the owners of the tomb, in ox carts or on horses. Appearing as early as the Eastern Zhou, and continued in later periods, a funerary procession was usually depicted on side walls in tombs, representing the escorting of the “soul carriage” of the dead from his mundane life to the otherworldly abode. The tradition continued to flourish in the following centuries in tombs located in various regions in northern China. One finds exactly the same juxtaposition of horses and an ox chariot on the Zhuanglang Pagoda as well as the two other steles from eastern Gansu. In the Central Binyang Cave at Longmen, and the Gongxian cave-temples in northern Henan, the procession of the emperor and empress still astounds visitors with magnificent craftsmanship. See (Wu 2010, pp. 60–70). |

| 54 | With attendants flanking or not, donor images are usually separated from each other by cartouches of inscriptions. Kate Lingley has written extensively on donors of Buddhist art in the sixth century. For instance, see (Lingley 2006, 2010). |

| 55 | For instance, the Wei Wenlang 魏文朗 Stele of 424, one of the earliest surviving Buddhist steles from Shaanxi, features a donor figure riding on a horse with an attendant and an ox cart following. See (Li 2008a, p. 33). Another stele of 546 from Pingliang depicts two registers of horse and cart riders on the lower part of its façade. See (Zhang 2000, pp. 172–74). |

| 56 | See the Quan Daonu 權道奴 Stele dated to 563, the third year of the Baoding era, Northern Zhou, and the Wang Lingwei 王令猥 Stele from Zhangjiachuan. See (Zhang 2000, pp. 205–6, 222–23). |

| 57 | Yizi 邑子, villagers who were members of yiyi, also perform charitable works for the benefit of the entire community. For more on the history of yiyi during the Northern dynasties, see (Twitchett 1957; Michihata 1967; Tanigawa 1985; Hou 1998, 2005, 2007; Gernet 1995, pp. 259–77). |

| 58 | |

| 59 | For full inscription, see note 7. |

| 60 | This is found on the Quan 權 Pagoda from Qin’an 秦安. It was discovered by locals in Wujiachuan 吳家川 in 1941, according to notes written on a rubbing of its pedestal. Without any other records of its discovery, it remains in debate whether other parts of the pagoda were unearthed at the same site. This study follows the theory of Wen Jing and Wei Wenbin, who argue that while the upper stone block of the pagoda is the original part dated 536, Western Wei, the lower two are from a separate set due to their display of a typical Northern Zhou style. This theory also draws evidence from the incompatibility between the three blocks and the three eaves. Meanwhile, the names of donors indicate its provenance in situ, since the clan of Quan 權, the surname of most donors, is among the most prominent families in the region since the fifth century. See (Wen and Wei 2012; Zhang 2000, p. 213). |

| 61 | “於本鄉南北舊宅,上為二圣造三級浮圖各一區.” See (Yen 2008, no. 1). |

| 62 | The inscription mentions the construction date of the second year of Xiaochang era, 526. “以寺內有五級浮圖一區,建自永昌,後因兵劫…” (…for the reason that there was a five-story pagoda in the monastery. Built in the Yongchang era, and because of warfare…) See (Yen 2008, no. 25). |

| 63 | The usage of “shi” (stone) highlights the choice of medium and material. |

| 64 | A number of scholars have examined the rich corpus of domed stūpa imagery of the sixth century. Among many, see (Tsiang 2000; Su 2006, 2010). |

References

Primary Sources in Chinese

Guoqu xianzai yinguo jing 過去現在因果經 (Sūtra on Past and Present Causes and Effects). Translated by Guṇabhadra 求那跋陀羅 (394–468). T. no. 189.Hou Han shu 後漢書 (The History of the Later Han). Fan Ye 范曄 (398–445). Taipei: Taiwan shangwu yinshuguan, 1984.Luoyang qielan ji jiaoshi 洛阳伽蓝记校释 (A Record of Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang). Yang Xianzhi 楊衒之. Commented by Zhou Zumo 周祖谟. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1963.Miaofa lianhua jing 妙法蓮華經 (Skt. Saddharma-puṇḍarīka-sūtra). Translated by Kumārajīva 鳩摩羅什 (343/4–413). T. 262.Puyao jing 普曜經 (General Radiance Sūtra; Skt. Lalitavistara). Translated by Dharamarakṣa 竺法護 (239–316). T. no. 186.Shui jing zhu 水經註 (Commentary on the Water Classic). Li Daoyuan 酈道元 (~527). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 2007.Taizi ruiying benqi jing 太子瑞應本起經 (Sūtra on the Life of the Prince in Accordance with Good Omens). Translated by Zhi Qian 支谦 (222–252). T. no. 185.Wei shu 魏書. Wei Shou 魏收 (505–572) et al. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1974.Weimojie suoshuo jing 維摩詰所說經 (Skt. Vimalakīrti-Nirdeśa-Sūtra). Translated by Kumārajīva 鳩摩羅什 (343/4–413). T. 14, 0475.Xu gaoseng zhuan 續高僧傳 (Supplement to the Biographies of Eminent Monks). Daoxuan 道宣 (596–667). T. 2060, 50.Zheng fahua jing 正法華經 (Lotus Sūtra). Translated by Dharamarakṣa 竺法護 (239–316). T. no. 263.Secondary Sources

- Abe, Stanley K. 2001. Provenance, Patronage, and Desire: Northern Wei Sculpture from Shaanxi Province. Ars Orientalis 31: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, Stanley K. 2002. Ordinary Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andreeva, Petya. 2018. Fantastic Beasts of the Eurasian Steppes: Toward A Revisionist Approach to Animal-Style Art. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bachhofer, Ludwig. 1946. A Short History of Chinese Art. New York: Pantheon. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, Kurt. 2003. The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhāra. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Behrendt, Kurt, ed. 2007. The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bingenheimer, Marcus. 2020. On the Use of Historical Social Network Analysis in the Study of Chinese Buddhism: The Case of Dao’an, Huiyuan, and Kumārajīva. Journal of the Japanese Association of Digital Humanities 5: 84–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, Pia, and Kurt Behrendt, eds. 2006. Gandharan Buddhism: Archaeology, Art, Texts. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Xuexia. 2011. Nannieshui shike zaoxiang de minjian tese: Qiantan shike yishu zai qinxian de chuancheng yu fazhan 南涅水石刻造像的民間特色:淺談石刻藝術在沁縣的傳承與發展 (Features of the Nannieshui Stone Statues: On the Inheritance and Development of Stone Sculptures at County Qin). Wenwu Shijie 4: 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Caswell, James O. 1975. The ‘Thousand-Buddha’ Pattern in Caves XIX and XVI at Yün-Kang. Ars Orientalis 10: 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Bingying. 1988. Bei Wei Cao Tianhu zao fang shita 北魏曹天護造方石塔 (Square stone pagoda commissioned by Cao Tianhu in Northern Wei). Wenwu 3: 83–85, 93. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Yikai. 1996. Lvelun Bei Wei shiqi Yungang shiku, Longmen shiku fudiao taxing" 略論北魏時期雲岡石窟龍門石窟浮雕塔型 (On Typology of Northern Wei Pagodas in Relief in Yungang and Longmen Cave-temples). In Longmen shiku yiqian wubai zhounian guoji xueshu taolunhui lunwenji 龍門石窟一千五百週年國際學術研討會論文集 (Proceeding of the International Symposium upon the Fifty Hundred Years Anniversary of the Long-men Cave-Temple). Beiijng: Wenwu Chubanshe, pp. 220–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Xiaozhong. 1998. Zhuanglang Yunyasi shiku neirong zonglu 莊浪雲崖寺石窟內容總錄 (Zhuanglang Yunyasi Cave Temples). Dunhuang yanjiu 敦煌研究 1: 41. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Xiaozhong, and Guangxue Ding. 1997. Zhuanglang xian chutu Bei Wei shi zaoxiang ta 莊浪縣出土北魏石造像塔 (Northern Wei Stone Pagodas Discovered in Zhuanglang). Dunhuangxue jikan 敦煌學輯刊 2: 134. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Xiaozhong, and Fuxue Yang. 2003. Zhuanglang shiku 莊浪石窟 (Zhuanglang Cave-Temples). Lanzhou: Gansu Wenhua Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, J. Leroy. 1954. The Lotus Sutra in Chinese Art: A Study in Buddhist Art to the Year 1000. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davy, Jack, and Charlotte Dixon, eds. 2019. Worlds in Miniature: Contemplating Miniaturisation in Global Material Culture. London: University College London Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Detian. 2016. Jingchuan Fojiao Kaogu Yanjiu. Ph.D. dissertation, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, China. [Google Scholar]

- Dingxian County Museum 定縣博物館. 1972. Hebei Dingxian faxian liangzuo Songdai Taji 河北定縣發現兩座宋代塔基 (Two Pagoda Foundations of the Song Dynasty Discovered at County Ding, Hebei). Wenwu 文物 8: 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Guangqiang. 2008. Zhuanglang Yunyasi deng shiku de diaocha jianbao 莊浪雲崖寺等石窟的調查簡報 (Report on Zhuanglang Yunyasi Cave Temples). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 3: 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Yusheng. 1981. Beiwei Yongningsi taji fajue jianbao 北魏永寧寺塔基發掘簡報. Kaogu 考古 3: 223–24. [Google Scholar]

- E, Yunan. 2011. Gansu sheng bowuguan cang Bushi shita tuxiang diaocha yanjiu” 甘肅省博物館藏卜氏石塔圖像調查研究 (On Images of the Bu Pagoda in the Gansu Provincial Museum). Dunhuangxue Jikan 敦煌學輯刊 4: 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- E, Yunan, and Fuxue Yang. 2014a. Gansu sheng bowuguan shoucang de yijian weikan Beichao canta 甘肅省博物館收藏的一件未刊北朝殘塔 (An Unpublished Piece of Fragmentary Stupa in Gansu Provincial Museum). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 4: 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- E, Yunan, and Fuxue Yang. 2014b. Qin’an Xi Wei shita quansuo 秦安西魏石塔权索 (On Western Wei Stone Pagodas from Qin’an). Xinjiang Shifan Daxue Xuebao 新疆师范大学学报 1: 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jaś. 2020. Figurines: Figuration and the Sense of Scale. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fogelin, Lars. 2012. Material Practice and the Metamorphosis of a Sign: Early Buddhist Stupas and the Origin of Mahayana Buddhism. Asian Perspectives 51: 278–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogelin, Lars. 2015. An Archaeological History of Indian Buddhism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gansu Beishikusi Wenwu Baohu Yanjiusuo 甘肅北石窟寺文物保護研究所, ed. 2013. Qingyang Beishikusi neirong zonglu 慶陽北石窟寺內容總錄 (On the North Cave Temple of Qingyang). 2 vols. Beijing: wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Gansu Sheng Wenwu Gongzuodui 甘肅省文物工作隊, ed. 1987. Hexi Shiku 河西石窟 (Hexi Cave-Temples). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Gansu Sheng Wenwu Gongzuodui 甘肅省文物工作隊, and Qingyang Bei Shiku Wenwu Baoguansuo 慶陽北石窟文物保管所. 1987. Longdong Shiku 隴東石窟 (Eastern Gansu Cave Temples). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Gansu Sheng Wenwu Ju 甘肅文物局, ed. 2014. Gansu Gu Ta Yanjiu 甘肅古塔研究 (Gansu Pagodas); Beijing: Kexue Chuban She.

- Gao, Meng. 2012. Tuta yu lifo 圖塔與禮佛 (Decorated Pagodas and Buddhist Worship). Ph.D. dissertation, Zhongyang meishu xueyuan 中央美術學院, Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Gernet, Jacques. 1995. Buddhism in Chinese Society: An Economic History from the Fifth to Tenth Centuries. Translated by Franciscus Verellen. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graves, Margaret. 2018. Arts of Allusion: Object, Ornament, and Architecture in Medieval Islam. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, Eric M. 2018. The ‘Religion of Images’? Buddhist Image Worship in the Early Medieval Chinese Imagination. Journal of the American Oriental Society 138: 455–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Yong. 1959. Shanxi Qinxian Faxian le Yipi Shike Zaoxiang 山西沁縣發現了一批石刻造像 (A Group of Stone Statues Discovered in the County of Qin, Shanxi). Wenwu 文物 3: 54–5. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Tongde. 1979. Shanxi Qinxian Nannieshui de Beiwei Shike Zaoxiang 山西沁縣南涅水的北魏石刻造像 (Northern Wei Stone Statues from Nannieshui, County of Qin, Shan-Xi). Wenwu 文物 3: 91–2. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Qinghua. 2010. The Mingqi Pottery Buildings of Han Dynasty China, 206 BC–AD 220. Portland: Sussex Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes, Jason, and Akira Shimada, eds. 2009. Buddhist Stūpas in South Asia. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Shizhe. 1992. Guanyu Shiliuguo Beichao shiqi de sanshi Fo yu san Fo zaoxiang zhuwenti: 1 關於十六國北朝時期的三世佛與三佛造像諸問題(一) (On Buddhas of the Three Ages and images of three Buddhas during the period of the Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern Dynasties). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 4: 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hebei Sheng Wenhuaju Wenwu Gongzuodui 河北省文化局文物工作隊. 1966. Hebei Dingxian chutu de Beiwei shihan 河北定縣出土的北魏石函 (Northern Wei Stone Chamber Discovered from County Ding, Hebei). Kaogu 考古 5: 252–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Jeehee. 2015. Mechanism of Life for the Netherworld: Transformations of Mingqi in Middle-Period China. Journal of Chinese Religion 2: 161–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Xudong. 1998. Wu Liu Shiji Beifang Minzhong Fojiao Xinyang 五六世紀北方民眾佛教信仰 (Buddhist Worship in the North of the Fifth and the Sixth Centuries). Beijing: Zhongguo Shehui Kexue Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Xudong. 2005. Beichao cunmin de shenghuo shijie: Chaoting, zhouxian yu cunli 北朝村民的生活世界:朝廷,州縣與村裡 (On Hamlets in the Northern Dynasties). Beijing: Shangwu Yinshuguan. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Xudong. 2007. On Hamlets (Cun 村) in the Northern Dynasties. Early Medieval China 1: 99–141. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Xudong. 2008. Bei Wei jingnei huzu zhengce chutan: Cong ‘Da Dai chijie Binzhou cishi Shangongsi bei’ shuoqi 北魏境內胡族政策初探:從“大代持節豳州刺史山公寺碑”說起 (On the Barbarian Policy in the Northern Wei Dynasty). Zhongguo Shehui Kexue 中國社會科學 5: 168–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, Eileen Hsiang-Ling. 2002. Visualization Meditation and the Siwei Icon in Chinese Buddhist Sculpture. Artibus Asiae 1: 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Wenhe. 2005. Yungang shiku mouxie ticai neirong he zaoxing fengge de yuanliu tansuo 雲岡石窟某些題材內容和造型風格的源流探索 (A survey of the themes and stylistic features of stories depicted in the Yungang Grotto). In 2005 nian Yungang guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwenji 2005年雲岡國際學術研討會論文集 (Proceedings for the 2005 International Conference on Yungang). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, pp. 17–37. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Shaoxiong. 2015. Daiguo Daijun tongzhi 代國代郡通志 (History of Dai). Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Hurvitz, Leon. 2009. Scripture of the Lotus Blossom of the Fine Dharma (the Lotus Sutra). New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimatsu, Hinako 石松日奈子. 2005. Hokugi bukkyō zōzōshi no kenkyū 北魏仏教造像史の研究 (Studies on the History of Northern Wei Buddhist Sculpture). Kunitachi-shi: Buryukke. [Google Scholar]

- Jayne, Horace F. 1929. The Buddhist Caves of Ching Ho Valley, Eastern Art: Part. 1.

- Junjirō, Takakusu. 1901. Tales of the Wise Man and the Fool, in Tibetan and Chinese. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 3: 447–60. [Google Scholar]

- Seishi, Karashima. 2017. Stūpas Described in the Chinese Translations of the Vinayas. In Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology at Soka University for the Academic Year 2017. Tokyo: Soka University, pp. 439–70. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Minku. 2011. The Genesis of Image Worship: Epigraphic Evidence for Early Buddhist Art in China. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Minku. 2014. Claims of Buddhist Relics in the Eastern Han Tomb Murals at Horinger: Issues in the Historiography of the Introduction of Buddhism to China. Ars Orientalis 44: 134–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledderose, Lothar. 1980. Chinese Prototypes of the Pagoda. In Stūpa: Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance. Edited by Anna L. Dallapiccola. Wiesbaden: Steiner, pp. 238–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ledderose, Lothar. 1983. The Earthly Paradise: Religious Elements in Chinese Landscape Art. In Theories of the Arts in China. Edited by Susan Bush and Christian F. Murch. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 165–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ledderose, Lothar. 2000. Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Junghee. 1993. The Origin and Development of the Pensive Bodhisattva Images of Asia. Artibus Asiae 53: 311–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sonya. 2010. Surviving Nirvana: Death of the Buddha in Chinese Visual Culture. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leidy, Denise P. 1990. The Ssu-wei Figure in Sixth Century A.D. Chinese Buddhist Sculpture. Archives of Asian Art 43: 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Huaiyao. 1986. Bajian gudai tong shi zaoxiang 八件古代銅、石造像 (Eight pieces of bronze and stone sculptures). Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 4: 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Jingjie. 1996. Zaoxiangbei Fo bensheng benxing gushi diaoke 造像碑佛本生本行故事雕刻 (Narrative scenes from the Buddha’s life story and birth stories on figured steles). Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 4: 66–83. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Song. 2008a. Fojiao meishu quanji 8: Shaanxi fojiao yishu 佛教美術全集 8:陝西佛教藝術 (Buddhist Art Series 8: Shaanxi Buddhist Art). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Yuqun. 2008b. Wutaishan Nanchansi jiucang Bei Wei jingang baozuo shi ta 五台山南禪寺舊藏北魏金剛寶座石塔 (The Vajra-based Stone Pagoda Preserved in the Nanchan Monastery on Mount Wutai). Wenwu 文物 4: 82–99. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Sicheng. 1961. Zhongguo di Fojiao jianzhu 中國的佛教建築 (Chinese Buddhist Architecture). Qinghua Daxue Xuebao 清華大學學報 2: 51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Sicheng. 1962. Mantan fota 漫谈佛塔. Guangming Ribao 光明日报, May 26. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Wei-Cheng. 2016. Performing Center in a Vertical Rise: Multilevel Pagodas in China’s Medieval Period. Ars Orientalis 46: 100–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lingley, Kate. 2006. The Multivalent Donor: Zhang Yuanfei at Shuiyusi. Archives of Asian Art 56: 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingley, Kate. 2010. Patron and Community in Eastern Wei Shanxi: The Gaomiaoshan Cave Temple Yi-Society. Asia Major 1: 127–72. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Huida. 1958. Bei Wei shiku zhong de sanfo 北魏石窟中的三佛 (Three Buddhas in Northern Wei cave-temples). Kaogu Xuebao 考古學報 4: 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Jinbao. 2000. Huaerna jiqi Dunhuang kaochatuan lunshu 華爾納及其敦煌考察團論述 (On Warner and his Dunhuang Expedition). Zhongguo Bianjiang Shidi Yanjiu 中國邊疆史地研究 1: 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shufen. 2005. Bei Wei shiqi de Hedong Shu Xue 北魏時期的河東蜀薛 (The Xue Clan of Shu during the Northern Wei in Hedong Prefecture). In Jiazu Yu Shehui 家族與社會. Edited by Huang Kuanzhong and Liu Zenggui. Beijing: Zhongguo dabaike Quanshu Chubanshe, pp. 259–81. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Shufen. 2008. Zhonggu de Fojiao yu shehui 中古的佛教與社會 (Medieval Chinese Buddhism and Society). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Di. 2016. A Grain of Sand: Yingzao Fashi and the Miniaturization of Chinese Architecture. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Changshou. 1985. Beiming suo jian Qian Qin zhi Sui chu de Guanzhong buzu 碑銘所見前秦至隋初的關中部族 (Guanzhong Clans form the Former Qin to early Sui Dynasty in Inscription). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju. [Google Scholar]

- Mair, Victor H. 1993. The Linguistic and Textual Antecedents of the Sūtra of the Wise and the Foolish. In Sino-Platonic Papers. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S. Rebecca, and Stephanie M. Langin-Hooper, eds. 2018. The Tiny and the Fragmented: Miniature, Broken, or Otherwise Incomplete Objects in the Ancient World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Michihata, Ryōshū. 1967. Chūgoku Bukkyō to Shakai Fukushi Jigyō 中國仏教と社會福祉事業 (Chinese Buddhism and the Social Wellfare). Kyoto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Tracy. 2014. Perfecting the Mountain: On the Morphology of Towering Temples in East Asia. Journal of Chinese Architecture History 10: 419–49. [Google Scholar]

- Miu, Zhe. 2012. Chongfang louge 重訪樓閣 (Revisiting Towers and Pavilions). Meishushi Yanjiu Jikan 美術史研究集刊 33: 2–111. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Seiichi, and Toshio Nagahiro. 1951–1956. Unkō Sekkutsu 雲岡石窟 (Yungang Cave-Temples). 16 vols. Kyoto: Kyoto Daigaku Jimbun Kagaku Kenkyūsho. [Google Scholar]

- Mukai, Yūsuke. 2020. Chūgoku Shoki Buttō no Kenkyū 中国初期仏塔の研究 (On Early Chinese Buddhist Pagodas). Kyōto: Rinsen Shoten. [Google Scholar]

- Nickel, Lucas. 2002. Return of the Buddha: The Qingzhou Discoveries. London: Royal Academy of Arts. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, Ken, and Hinako Ishimatsu. 1993. Chūgoku Nanbokuchaō jidai no nyorai zōchakui no kenkyūs. Bijutsu Kenkyu 356: 181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rei, Sasaguchi. 1975. The Image of the Contemplating Bodhisattva in Chinese Buddhist Sculpture. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rhi, Juhyung. 2006. Some Textual Parallels for Gandhāran Art: Fasting Buddhas, Lalitavistara, and Karuṇāpuṇḍarīka. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 1: 125–53. [Google Scholar]

- Seckel, Dietrich. 1980. Stūpa Elements Surviving in East Asian Pagodas. In Stūpa: Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance. Edited by Anna L. Dallapiccola. Wiesbaden: Steiner, pp. 249–59. [Google Scholar]

- Selbitschka, Armin. 2005. Miniature Tomb Figurines and Models in Pre-imperial and Early Imperial China: Origins, Development and Significance. World Archaeology 1: 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanxi Sheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo 山西省考古研究所, ed. 1994. Shanxi Kaogu Sishi Nian 山西考古四十年 (Forty Years of the Archaeological Research in Shanxi). Taiyuan: Shanxi Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Shuqing. 1980. Beiwei Cao Tiandu zao qianfo shita 北魏曹天度造千佛石塔 (Thousand-Buddha stone pagoda commissioned by Cao Tiandu of Northern Wei). Wenwu 文物 1: 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Wenyu, ed. 2009. Beishikusi Lunwenji 北石窟寺論文集 (Collected Papers on the North Cave Temple). Qingyang: Gansu Beishikusi Wenwu Baohu Yanjiusuo. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Rolf A. 1990. The World in Miniature: Container Gardens and Dwellings in Far Eastern Religious Thought. Translated by Phyllis Brooks. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, Nancy S. 2011. The Sixth Century in East Asian Architecture. Ars Orientalis 41: 27–71. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, Nancy S. 2014. Chinese Architecture in an Age of Turmoil, 200–600. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhardt, Nancy S. 2019. Chinese Architecture: A History. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, Susan. 1993. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stockhammer, Philip W. 2013. From Hybridity to Entanglement, from Essentialism to Practice in Archaeology and Culture Mixture. Archaeological Review from Cambridge 28: 11–28. [Google Scholar]

- Strong, John S. 1983. The Legend of King Asoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Bai. 1996. Luoyang diqu Beichao shiku de chubu kaocha 洛陽地區北朝石窟的初步考察 (A Preliminary Study of Cave-temples of the Northern Dynasties near Luoyang). In Zhongguo shikusi yanjiu 中國石窟寺研究. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, pp. 153–76. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Xuanshu. 2006. Dong Wei Bei Qi baotawen yanjiu 東魏北齊寶塔紋研究 (On the Treasure Stūpa Pattern in Eastern Wei and Northern Qi). Yishushi yanjiu 藝術史研究 8: 323–64. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Xuanshu. 2010. Gudai Dongya zhuguo danceng fangta yanjiu 古代東亞諸國單層佛塔研究 (Study of the One-story Cubical Stūpas in East Asian). Wenwu 文物 11: 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Su, Bai. 2011. Donghan Weijin Nanbeichao Fosi buju chutan 东汉魏晋南北朝佛寺布局初探 (A Preliminary Study on the Layout of Buddhist Temples in the Eastern Han, Wei-Jin era, and Six Dynasties). In Weijin Nanbeichao Tangsong kaogu Wengao Jicong 魏晉南北朝唐宋考古文稿集成 (On Archaeology of the Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern Dynasties, Tang, and Song). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, pp. 230–47. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Ji. 1984. Zhongguo zaoqi gaoceng fota zaoxing de yuanyuan wenti 中国早期高层佛塔造型的渊源问题 (Issues on the Origin of Early Chinese Multistory Pagoda’s Structure). Zhongguo Lishi Bowuguan Guankan 中國歷史博物館館刊 6: 41–47, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Changru. 1955. Wei Jin Za hu kao 魏晉雜胡考 (Barbarians of Wei and Jin). In Wei Jin Nan Bei Chao Shi Luncong 魏晉南北朝史論叢. Beijing: Sanlian Shudian, pp. 403–14. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Zhongming. 2016. Zhongyuan diqu Beichao Fo ta yanjiu 中原地区北朝佛塔研究 (Study on Buddhist Pagodas of the Northern Dynasties in the Central Plain). Kaogu 考古 11: 95–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tanigawa, Michio. 1985. Medieval Chinese Society and the Local “Community”. Translated by Joshua A. Fogel. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiang, Katherine. 2000. Miraculous Flying Stupas in Qingzhou Sculpture. Orientations 31: 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Twitchett, Denis. 1957. The Monasteries and China’s Economy in Medieval Times. BSOAS 3: 526–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zonghui. 1985. Handai Lushui Hu De Zuming Yu Judi Wenti 漢代盧水胡的族名與居地問題 (On the name and territory of Lushui hu during the Han dynasty). Xibei shidi 西北史地 1: 25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Qing. 1997. Ye lun Lushui hu yiji Yuezhi hu de juchu he zuyuan 也論盧水胡以及月氏胡的居處和族源 (On Habitat and Origin of the Lushui hu and Rouzhi hu). Xibei Shidi 西北史地 2: 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Eugene Y. 1999. What do Trigrams have to do with Buddhas? The Northern Liang Stupas as a Hybrid Spatial Model. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 1: 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiaohong. 2004. Gansu sheng bowuguan cang liangjian Beichao fojiao shike 甘肅省博物館藏兩件北朝佛教石刻 (Two Pieces of Buddhist Stone Sculptures of the Northern Dynasties in Gansu Provincial Museum). Sichou Zhi Lu 絲綢之路 1: 31–33. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Eugene Y. 2005. Shaping the Lotus Sutra: Buddhist Visual Culture in Medieval China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yuanlin. 2006. Bei Wei zhong xiao xing zaoxiang shi ta de xingzhi yu neirong 北魏中小型造像石塔的形製與內容 (The typology and content of images on Northern Wei stone pagodas of the medium and small sizes). In 2005 Nian Yungang Guoji Xueshu Yantaohui Lunwen Ji 2005 年雲岡國際學術研討會論文集研究卷. Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, pp. 547–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Guixiang. 2011a. Lve lun Zhongguo gudai gaoceng jianzhu de fazhan 略論中國古代高層建築的發展 (On the Development of Multi-level Buildings in Classical China). In Zhongguo Gudai Mugou Jianzhu Bili Yu Chidu Yanjiu 中國古代木構建築比例與尺度研究 (Study on the Ratio of Classical Chinese Wooden Buildings). Beijing: Zhongguo Jianzhu Gongye Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Miaozhen. 2011b. Bei Wei Cao Tiandu jiuceng shita xiyi 北魏曹天度九層石塔析疑 (On the nine-story Cao Tiandu pagoda of Northern Wei). Heihe Xuekan 黑河學刊 2: 79–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Huaiyou. 2015. Pingliang chutu Bei Wei fojiao shike zaoxiang tanxi 平涼出土北魏佛教石刻造像探析 (Northern Wei Buddhist Stone Statues Excavated at Pingliang). Sichou Zhi Lu 絲綢之路 4: 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Huaiyou. 2016. Gansu Huating xian chutu Beichao fojiao shike zaoxiang gongyangren zushu kao 甘肅華亭縣出土北朝佛教石刻造像供養人族屬考 (On the Ethnicity of Donors of Buddhist Stone Statues Excavated in Huating, Gansu). Dunhuangxue jikan 敦煌學輯刊 2: 133–145. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Jiqing, and Susan Elizabeth Mrozowski. 1990. Dunhuang shoucang de Dunhuang yu Zhongya yishupin 敦煌收藏的敦煌與中亞藝術品. Dunhuangxue Jikan 1: 116–28. [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Longdon. 1926. The Long Old Road in China. Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Campany. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Wenbin. 2005. 20 shiji zao zhongqi Gansu shiku de kaocha yu yanjiu zongshu 20世紀早中期甘肅石窟的考察與研究綜述 (On the Investigationa and Study on Gansu Cave-temples in the early- and mid-20th Century). Dunhuangxue Jikan 敦煌學輯刊 1: 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, Wenbin, and Hong Wu. 2009. Gansu Fojiao Shiku Kaogu Lunji 甘肅佛教石窟考古論集 (Archaeology of the Buddhist Cave-temples of Gansu). Beijing: Minzu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Jing, and Wenbin Wei. 2012. Gansu guancang fojiao zaoxiang diaocha yu yanjiu zhiyi 甘肅館藏佛教造像調查與研究之一 (Investigation and Research on Buddhist Statues from Gansu Collections, part 1). Dunhuang Yanjiu 敦煌研究 4: 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Paul. 2009. Mahāyāna Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Dorothy C. 2004. Chinese Steles: Pre-Buddhist and Buddhist Use of a Symbolic Form. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 2010. The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs. London: Reaktion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Hung. 2015. The Invisible Miniature: Framing the Soul in Chinese Art and Architecture. Art History 2: 286–303. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Nai. 1966. Hebei Dingxian taji shelihan zhong Bosi Sashan chao yinbi 河北定縣塔基舍利函中波斯薩珊朝銀幣 (Persian Silver Coins from the Relic Chamber Excavated from the Pagoda Foundation at County Ding, Hebei). Kaogu 考古 5: 267–70. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Mo. 1989. Dunhuang Jianzhu Yanjiu 敦煌建築研究 (Dunhuang Architecture). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Zhicheng. 1987. Sichuan Handai huaxiangzhuan shang de fota xingxiang 四川汉代画像砖上的佛塔形象 (Pagoda Image on Sichuan Pictorial Bricks of the Han Dynasty). Sichuan Wenwu 四川文物 4: 62–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Pingfang. 1994. Zhongguo sheli taji kaoshu 中国舍利塔基考述 (On Chinese Pagoda Foundations with Relics). Chuantong Wenhua Yu Xiandaixing 傳統文化與現代性 4: 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Yitao. 2016. Gongyuan wu zhi shisan shiji Zhongguo zhuanshi Fo ta tabi Zhuangshi leixing fenqi yanjiu 公元5至13世紀中國磚石佛塔塔壁裝飾類型分期研究 (Study on the Categorization of Decorations on Exterior of Chinese Brick and Stone Pagodas). Gugong Bowuyuan Yuankan 故宮博物院院刊 2: 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yagi, Haruo. 2004. Chūgoku Bukkyō bijutsu to Kan minzokuka: Hokugi jidai kōki o chūshin to shite 中国美術と漢民族化—北魏時代後期を中心として (Sinicization of Chinese Buddhist art in late Northern Wei). Kyōto: Hōzōkan. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Wenru. 1984. Maijishan Shiku 麥積山石窟. Lanzhou: Gansu Renmin Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yen, Chuan-Ying. 2008. Beichao Fojiao Shike Tapian Baipin 北朝佛教石刻拓片百品 (Rubbings of Buddhist Stone Carvings from the Northern Dynasties). Taipei: Zhongyang Yanjiuyuan. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Lidu. 2017. Yungang: Art, History, Archaeology, Liturgy. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Guangming. 2000. Bei Liang Shita Yanjiu 北涼石塔研究 (On Northern Liang Stone Stūpas). Xinzhu: Chueh-Feng Buddhist Art & Cultural Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Yungang Shiku Wenwu Baoguansuo 雲岡石窟文物保管所. 1991. Zhongguo Shiku: Yungang Shiku 中國石窟:雲岡石窟 (Chinese Cave-Temples: Yungang). Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Yuxian Difangzhi Bianzuan Weiyuanhui 蔚縣地方志編纂委員會. 1995. Yuxian Zhi 蔚縣志 (Records of the County Yu). Beijing: Zhongguo Sanxia Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Baoxi, ed. 1994. Gansu Shiku Yishu: Diaosu Bian 甘肅石窟藝術:雕塑編 (Gansu Cave-Temple Art: Sculpture). Lanzhou: Gansu Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Baoxi, ed. 2000. Gansu Fojiao Shike Zaoxiang 甘肅佛教石刻造像 (Gansu Buddhist Stone Statues). Lanzhou: Gansu renmin Meishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Mingyuan. 2005. Shanxi Shike Zaoxiang Yishu Jicui 山西石刻造像藝術集萃 (Selected Stone Sculptures from Shanxi). Taiyuan: Shanxi Kexue Jishu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Yongfu. 1986. Guanyu Lushui hu zu de zuyuan ji qianyi 關於盧水胡的族源及遷移 (On the Origin and Migration of the Lushui hu). Xibei Shidi 西北史地 4: 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Jinchao. 2020. Reconfiguring the Buddha’s Realm: Pictorial Programs on Fifth-century Chinese Miniature Pagodas. In Tradition, Transmission, and Transformation: Perspectives on East Asian Buddhist Art. Edited by Dorothy C. Wong. Delaware: Vernon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Binglin, Yingchun Wei, and Qingshan Zhao, eds. 2014. Longdong Hexi Shiku Yanjiu Wenji 隴東河西石窟研究文集 (Collected Papers on the Hexi Cave-Temples of Eastern Gansu). 2 vols. Lanzhou: Gansu Wenhua Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo 中国社会科学院考古研究所. 1996. Bei Wei Luoyang Yongningsi: 1979–1994 nian kaogu fajue baogao 北魏洛阳永宁寺: 1979–1994年考古发掘报告 (Northern Wei Yong-ning Monastery in Luoyang: A Report on Archaeological Excavations from 1979 to 1994). Beijing: Zhongguo Dabaike Quanshu Chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo 中国社会科学院考古研究所, and Hebei Sheng Wenwu Yanjiusuo Yecheng Kaogudui 河北省文物研究所鄴城考古隊. 2010. Hebei Linzhangxian Yecheng yizhi Zhaopengcheng beichao fosi yizhi de kantan yu fajue 河北臨漳縣鄴城遺址趙彭城北朝佛寺遺址的勘探與發掘 (Excavations at the Monastic Sites of the Northern Dynasties at Zhanpengcheng site, Yecheng, in present-day Linzhang, Hebei). Kaogu 考古 7: 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Zhongguo Shehui Kexueyuan Kaogu Yanjiusuo 中国社会科学院考古研究所, and Hebei Sheng Wenwu Yanjiusuo 河北省文物研究所. 2013. Hebei Yecheng yizhi Zhaopengcheng Beichao fosi yu Beiwuzhuang fojiao zaoxiang maicangkeng 河北鄴城遺址趙彭城北朝佛寺與北吳莊佛教造像埋藏坑 (The Zhaopengcheng Buddhist Temple and the Beiwuzhuang Buddhist Sculptures Hoarding Pit from the site of Yecheng, Hebei). Kaogu 考古 7: 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Yiliang. 1963. Beichao de minzu wenti yu minzu zhengce 北朝的民族問題與民族政策 (Ethnicity and Regulations of the Northern Dynasties). In Wei Jin Nan Beichao Shi Lunji 魏晉南北朝史論集. Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, pp. 117–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 1972. The Buddhist Conquest of China: The Spread and Adaptation of Buddhism in Early Medieval China. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, J. Generating Sacred Space beyond Architecture: Stacked Stone Pagodas in Sixth-Century Northern China. Religions 2021, 12, 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090730

Zhao J. Generating Sacred Space beyond Architecture: Stacked Stone Pagodas in Sixth-Century Northern China. Religions. 2021; 12(9):730. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090730

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Jinchao. 2021. "Generating Sacred Space beyond Architecture: Stacked Stone Pagodas in Sixth-Century Northern China" Religions 12, no. 9: 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090730

APA StyleZhao, J. (2021). Generating Sacred Space beyond Architecture: Stacked Stone Pagodas in Sixth-Century Northern China. Religions, 12(9), 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12090730