Building and Rebuilding Buddhist Monasteries in Tang China: The Reconstruction of the Kaiyuan Monastery in Sizhou

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Buddhist Monasteries in Tang China

2.1. Functions

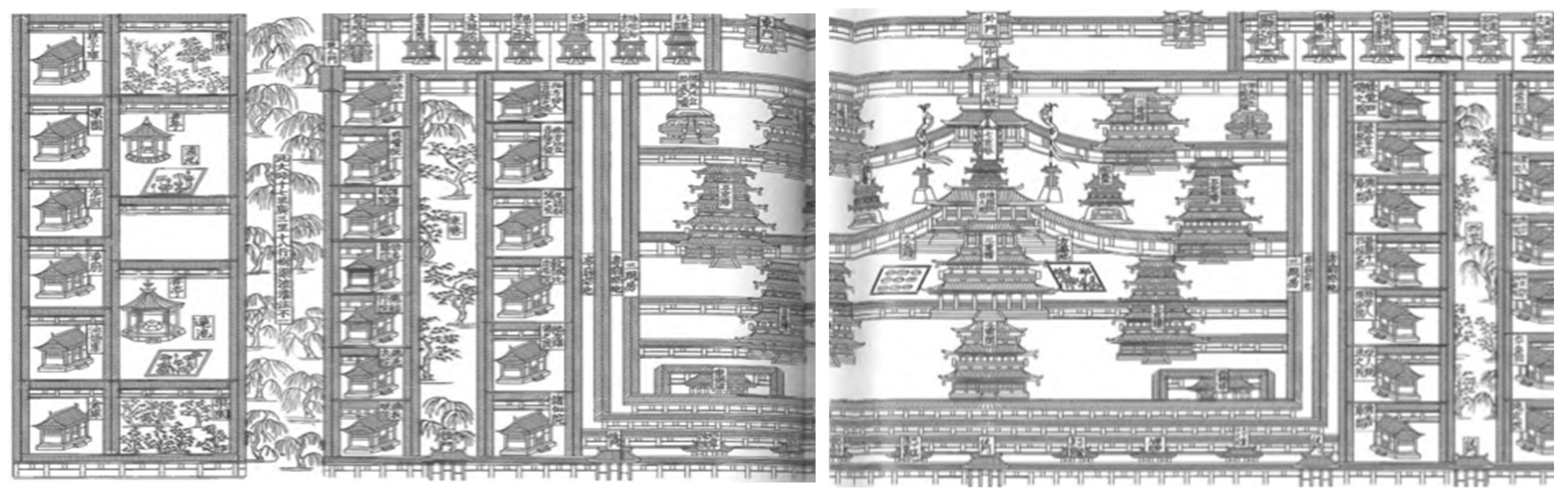

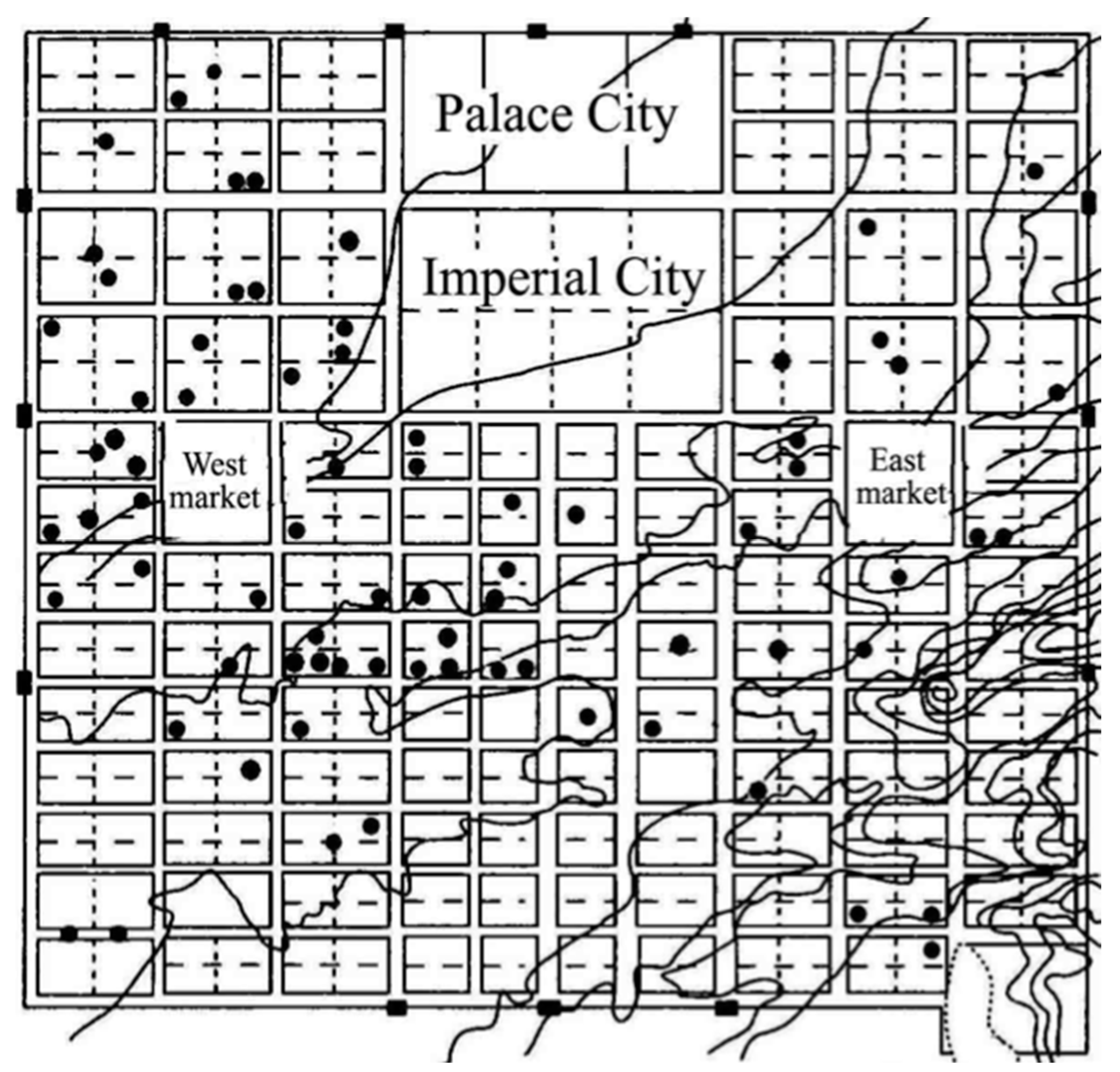

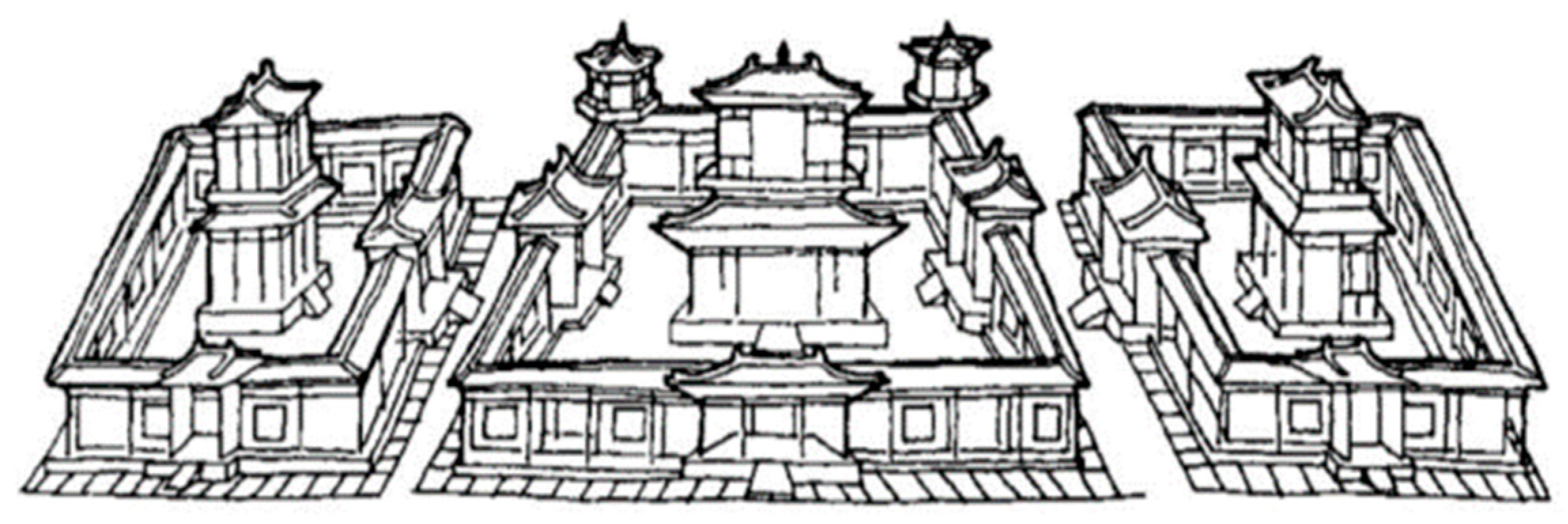

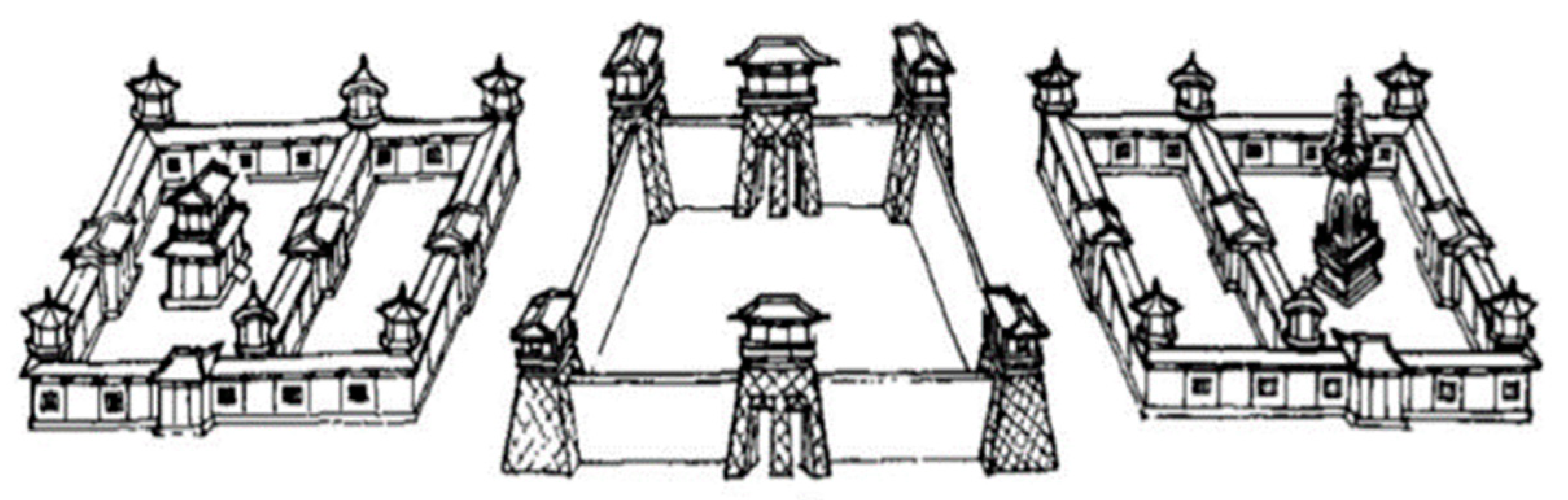

2.2. Architecture

Each ward contained one or several courtyards, depending on their size and function. Inside were public agencies, monasteries, ancestor temples, and countless larger and smaller residences … The similarities in the layout of the courtyards made it easy to exchange functions—for instance, to convert a private residence into a monastery or a monastery into a government office.

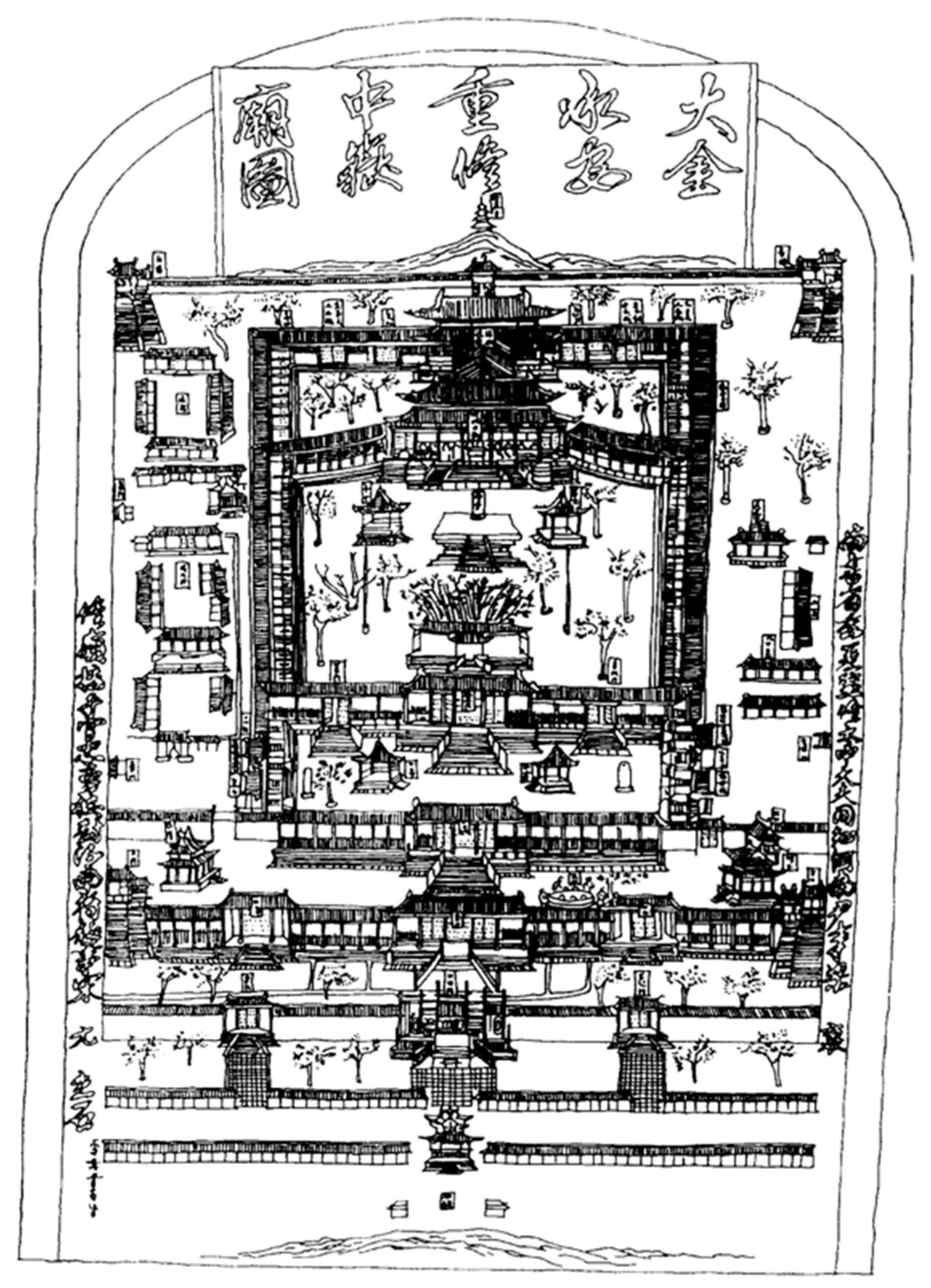

There were multi-story buildings, halls towering high, and densely built houses. A total of ten or more compounds with one thousand eight hundred and ninety-seven houses altogether.

重樓複殿,雲閣洞房。凡十餘院,總一千八百九十七間。

2.3. Textual Sources of Information on Regional Monasteries

3. The Kaiyuan Monastery in Sizhou, Jiangsu Province

3.1. Textual Sources

3.2. The First Phase of the Reconstruction: Master Chengguan

3.3. Further Reconstruction and Expansion under Mingyuan

3.3.1. Mingyuan’s Early Career: Expansion of the Kaiyuan Monastery and Its Function as a Flood Barrier

In the first year of the Yuanhe era (806), he was asked by the multitude to become the abbot of this monastery, the next year he was appointed by the government [authorities] as Great Monastic Rectifier in the region, overseeing the twelve divisions. Two hundred steps north from the Kaiyuan monastery, [he] built seven lecture halls [and] six monastic compounds.

元和元年,眾請充當寺上座,明年官補爲本州僧正,統十二部。開元寺北地二百步,作講堂七間,僧院六所。

There are heavy rains in the low land between the Huai and Si [prefectures]; they cause yearly floods. The Master [Mingyuan] planned with Su Yu, a commandery governor, [and] other [officials] to establish a monastic ward in the wasteland to the west of the Shahu [area] in order to prevent water flow. [They] constructed two hundred [buildings, including] gates, corridors, halls, kitchens, [and] stables; [they] planted ten thousand pine, cedar, willow, [and] cypress trees. Since then, the monks and the laity have been in no danger of flooding.

又淮,泗間地卑多雨潦,歲有水害,師與郡守蘇遇等謀於沙湖西隙地創避水僧坊,建門廊廳堂廚廄二百間,植松杉楠檉檜一萬本,由是僧與民無墊溺患。

3.3.2. The Ordination Platform and the New Complex

Soon after that, the monastery burned in a fire. For a few years, the monastery was in a state of disrepair, the statues were destroyed, [and] the monks scattered.

旋屬災焚本寺,寺殲像滅僧潰者數年。

The Master [Mingyuan] and Wang [Zhixing], a military commander in Xuzhou, were destined [to meet]. United in their intentions, [they] joined forces to rebuild the monastic compound. Thus, the master was invited to accept the position of Rectifier of Monks of the three prefectures [and] a petition was presented [to the emperor] with a request to establish an ordination platform without delay. The profits from the donations enabled [rebuilding] on a larger scale, the Palace Attendant [Wang Zhixing] also assisted [by donating] household goods amounting to ten thousand [in cash], [and the reconstruction] was completed.

師與徐州節度使王侍中有緣 ,遂合願叶力,再造寺宇,乃請師爲三郡僧正,奏乞連置戒壇,因其施利,廓其規度,侍中又以家財萬計助而成之。

From tower halls, residential halls, corridors, kitchens, [and] granaries to houses for monks, servants52, workers, [and] livestock. There were a total of two thousand and several hundred buildings. Inside [these buildings], there were ample statues [and] utensils … Star-shaped decorations adorned the buildings; [they seemed to have] emerged from beneath the earth, or descended from heaven. Donations arrived every single day; the sound of bells and chanting never ceased. The four varga53 know [where to find] refuge, [an] uncountable [number of] people [have] converted [to Buddhism].

自殿閣堂亭廊庖廪藏,洎僧徒臧獲傭保馬牛之舍,凡二千若干百十間,其中像設之儀,器用之具,一無闕者 … 輪奐莊嚴,星環棋布,如自地踴,若從天降。供施無虛日,鍾梵有常聲,四眾知歸,萬人改觀。

4. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

Primary Sources

Bai Juyi jijianjiao 白居易集箋校 (Annotated and Collated Edition of Bai Juyi’s Collected Works). Edited by Zhu Jincheng 朱金城. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1988.Cefu yuangui 册府元龜 (The Imperial Book Treasury as Grand Tortoise). Compiled by Wang Qingruo 王欽若. Nanjing: Fenghuang chubanshe, 2006.Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 (Old History of the Tang). Compiled by Liu Xu 劉昫. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1975.Nittō guhōjunrei kōki 入唐求法巡禮行記 (Record of a Pilgrimage to Tang China in Search of the Law). Composed by Ennin 圓仁. Guilin: Guangxi shifan daxue chubanshe, 2007.Quan Tang shi 全唐詩 (Complete Poems of the Tang). Compiled by Peng Dingqiu 彭定求.Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1960.Quan Tang wen 全唐文 (Complete Prose of the Tang). Compiled by Dong Hao 董浩. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1983.Siku quanshu cunmu congshu 四庫全書存目叢書 (Collectanea of Books that Were Noted in the Catalogue of the Complete Books in the Four Treasuries). Jinan: Qi Lu shushe chubanshe, 1996.Taishō shinshū daizōkyō 大正新修大藏經 (New Edition of the Buddhist Canon in the Taishō Era). Edited by Takakusu Junjirō 高楠順次郎 and Watanabe Kaikyoku 渡邊海旭. Tōkyō: Taishō Issaikyō Kankōkai, 1924–1932.Tang Wencui 唐文萃 (The Finest Prose of the Tang Dynasty). Compiled by Yao Xuan 姚铉. Changchun: Jilin renmin chubanshe, 1998.Wen Xuan 文選 (A Selection of Refined Literature). Compiled by Xiao Tong 蕭統. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1986.Wenyuan yinghua 文苑英華 (Blossoms from the Garden of Literature). Compiled by Li Fang 李昉. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1966.Zizhi tongjian 資治通鑑 (Comprehensive Mirror for the Aid of Government). Compiled by Sima Guang 司馬光. Beijing: Guji chubanshe, 1956.Secondary Sources

- Barrett, Timothy H. 1992. Li Ao: Buddhist, Taoist, or Neo-Confucian? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Timothy H. 2005. Buddhist Precepts in a Lawless World: Some Comments on the Linhuai Ordination Scandal. In Going Forth: Visions of Buddhist Vinaya. Edited by William Bodiford. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, pp. 101–22. [Google Scholar]

- Burdorf, Suzanne. 2019. Alerting the Masses: An Inquiry into Buddhist Communication through Bells in the Song Dynasty (960–1279): China from the Perspective of Material Culture and Sound. Monumenta Serica–Journal of Oriental Studies 67: 319–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ch’en, Kenneth Kuan Sheng. 1964. Buddhism in China: A Historical Survey. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Chiu Ming. 1991. Between the World and the Self-orientations in Po Chü-i’s (772–846) Life and Writings. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Jinhua. 2015. The Multiple Roles of the Twin Chanding Monasteries in Sui–Tang Chang’an. Studies in Chinese Religions 1: 344–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feifel, Eugène. 1961. Po Chü-i as a Censor: His Memorials Presented to Emperor Hsien-tsung during the Years 808–10. The Hague: Mouton. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Antonino. 1983. Daiji 大寺 (The Masters of Great Virtue). In Hōbōgirin—Dictionnaire encyclopédique du bouddhisme d’après les sources chinoises et japonaises. Paris and Tōkyō: L’Académie des Inscription et Belles-Lettres, Institute de France, vol. VIII, pp. 682–704. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Antonino. 1992. Chinese State Monasteries in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries. In Echō ō Go-Tenchikukyū den kenkyū 慧超往五天竺國伝研究. Edited by Kuwayama Shōshin 桑山正進. Kyoto: Jinbun kagaku kenkyūjo, pp. 213–58. [Google Scholar]

- Forte, Antonino. 2003. Daisōjō 大僧正 (The Grand Monastic Rectifier). In Hōbōgirin—Dictionnaire encyclopédique du bouddhisme d’après les sources chinoises et japonaises. Paris-Tōkyō: L’Académie des Inscription et Belles-Lettres, Institute de France, vol. VIII, pp. 1043–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gernet, Jacques. 1995. Buddhism in Chinese Society: An Economic History from the Fifth to the Tenth Centuries. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Guoqiang. 龔國強. 2006. Sui Tang Chang’an cheng fosi yangjiu 隋唐長安城佛寺研究. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Goossaert, Vincent. 2000. Dans Les Temples de la Chine: Histoire des cultes, vie des communautés. Paris: Albin Michel. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, Mark. 1997. Pieties and Responsibilities: Buddhism and the Chinese Literati: 780–1280. Ph.D. dissertation, University of California-Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, Mark. 2006. Out of the Cloister: Buddhism in Elite Lay Discourse in Sung China, 960–1279. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Hamar, Imre. 2002. A Religious Leader in the Tang: Chengguan’s Biography. Tokyo: International Institute for Buddhist Studies, International College for Advanced Buddhist Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Hargett, James M. 1996. Song Dynasty Local Gazetteers and Their Place in the History of Difangzhi Writing. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 56: 405–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, Charles. 1986. Han Yü and the T’ang Search for Unity. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Liqun. 2013a. Cong Beiwuzhuang foxiang maicangken lun Yecheng zhaoxiang de fazhan jieduan yu Yecheng moshi 從北吳莊佛像埋藏坑論鄴城造像的發展階段與“鄴城模式”. Kaogu 考古 5: 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- He, Liqun. 何利群. 2013b. Buddhist State Monasteries in Early Medieval China and their Impact on East Asia. Ph.D. dissertation, Heidelberg University, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, Ann, and Peter Bumbacher Stephan, eds. 2007. The Spread of Buddhism. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Heirman, Ann, and Mathieu Torck. 2012. A Pure Mind in a Clean Body: Bodily Care in the Buddhist Monasteries of Ancient India and China. Gent: Academia Press, Ginkgo. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Puay-peng. 1995. The Ideal Monastery: Daoxuan’s Description of the Central Indian Jetavana Vihāra. East Asian History 10: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ledderose, Lothar. 1980. Chinese Prototypes of the Pagoda. In The Stūpa: Its Religious, Historical and Architectural Significance. Edited by Anna Libera Dallapiccola and Stephanie Zingel-Ave Lallemant. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, pp. 238–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ledderose, Lothar. 2000. Ten Thousand Things: Module and Mass Production in Chinese Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Chaodong. 凌朝棟. 2005. Wenyuan yinghua yanjiu 文苑英華研究. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Mazanec, Thomas J. 2017. The Invention of Chinese Buddhist Poetry: Poet–Monks in Late Medieval China (c. 760–960 CE). Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, Princetoni, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- McMullen, David. 1988. State and Scholars in T’ang China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McRae, John R. 2005. Daoxuan’s Vision of Jetavana: The Ordination Platform Movement in Medieval Chinese Buddhism. In Going Forth: Visions of Buddhist Vinaya. Edited by William Bodiford. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, pp. 68–100. [Google Scholar]

- Mesnil, Evelyne. 2006. Didactic Paintings between Power and Devotion. In Essays on East Asian Religion and Culture. Edited by Christian Wittern and Shi Lishan. Kyoto: Festschrift Committee for Nishiwaki Tsuneo, pp. 97–148. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, Stephen. 2007. The Manuscript Legacy of the Tang: The Case of Literature. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 67: 259–326. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, Chengzhong. 2016. Slaves (nubi 奴婢) in Daoxuan’s Vinaya Writings. Studies in Chinese Religions 2: 18–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robson, James. 2009. Introduction: Neither too Far, nor too Near: The Historical and Cultural Contexts of Buddhist Monasteries in Medieval China and Japan. In Buddhist Monasticism in East Asia: Places of Practice. Edited by James Benn, Lori Meeks and James Robson. London: Routledge, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Tatsuhiko. 妹尾達彥. 1993. Haku Kyoi to Choan, Rakuyō 白居易と長安, 洛陽. In Haku Kyoi kenkyū kōza 白居易研究講座. Vol. I: Haku Kyoi bungaku to jinsei 白居易文学と人生. Edited by Ōta Tsugio 太田次男. Tokyo: Benseisha, pp. 270–96. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, Anna M. 2015. One who Knows Me: Friendship and Literary Culture in Mid-Tang China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, Anna M. 2017. The “Supplementary” Historian? Li Zhao’s Guo shi bu as Mid-Tang Political and Social Critique. T’oung Pao 103: 413–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, Anna. 2021. State, Bureaucracy, and the Formation of Regional Monastic Communities in Tang Buddhism. Ph.D. dissertation, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Tackett, Nicolas. 2014. The Destruction of the Medieval Chinese Aristocracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center. [Google Scholar]

- Teiser, Stephen F. 2006. Reinventing the Wheel: Paintings of Rebirth in Medieval Buddhist Temples. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Twitchett, Denis C. 1956. Monastic Estates in T’ang China. Asia Major 5: 123–46. [Google Scholar]

- Waley, Arthur. 1951. The Life and Times of Po Chü-i. London: George Allen and Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Yintian. 王銀田. 2000. Bei Wei Pingcheng mingtang yizhi yanjiu 北魏平城明堂遺址研究. Zhongguoshi yanjiu 中國史研究 1: 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein, Stanley. 1987. Buddhism under the T’ang. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Mo. 蕭默. 2003. Dunhuang jianzhu yanjiu 敦煌建築研究. Beijing: Jixie Gongye chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Siwei. 謝思煒. 1997. Bai Juyi ji zonglun 白居易集綜論. Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Chongguang. 謝重光, and Wengu Bai. 白文固. 1990. Zhongguo sengguan zhidu shi 中國僧官制度史. Qinghai: Qinghai Renmin chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Gengwang. 嚴耕望. 1992. Tangren xiye shanlin siyuan zhi fengshang 唐人習業山林寺院之風尚. In Yan Gengwang shixue lunwen ji 嚴耕望史學論文集. Taibei: Lianjing, pp. 271–316. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Lien-sheng. 1950. Buddhist Monasteries and Four Money-Raising Institutions in Chinese History. Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 13: 174–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Yuhuan. 張馭寰. 2008. Zhongguo Fojiao siyuan jianzhu jiangzuo 中國佛教寺院建築講座. Beijing: Dangdai zhongguo chubanshe. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Dewei. 2013. An Unforgettable Enterprise by Forgotten Figures: Making the Zhaocheng Canon 趙城藏 in North China under the Jurchen Jin Regime. ZINBUN: Memoirs of the Research Institute for Humanistic Studies (Kyoto University) 44: 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 1989. Buddhism and Education in T’ang Times. In Neo-Confucian Education: The Formative Stage. Edited by W. Theodore de Bary and John W. Chaffee. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 19–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zürcher, Erik. 2014. Buddhism in a Pre-modern Bureaucratic Empire: The Chinese Experience. In Buddhism in China: Collected Papers of Erik Zürcher. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk. Leiden: Brill, pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The literature on monasticism during this period is vast. See, among many other sources: (Goossaert 2000; Heirman and Stephan 2007; Xie and Bai 1990). |

| 2 | These are the official figures of monastic institutions that were dismantled and destroyed during the Huichang 會昌 persecution of Buddhism (840–46). See (Weinstein 1987, p. 134). |

| 3 | There are a handful of exceptions to this rule, including Evelyne Mesnil’s excellent study on the Dashengci monastery 大聖慈寺 in Chengdu (Mesnil 2006). |

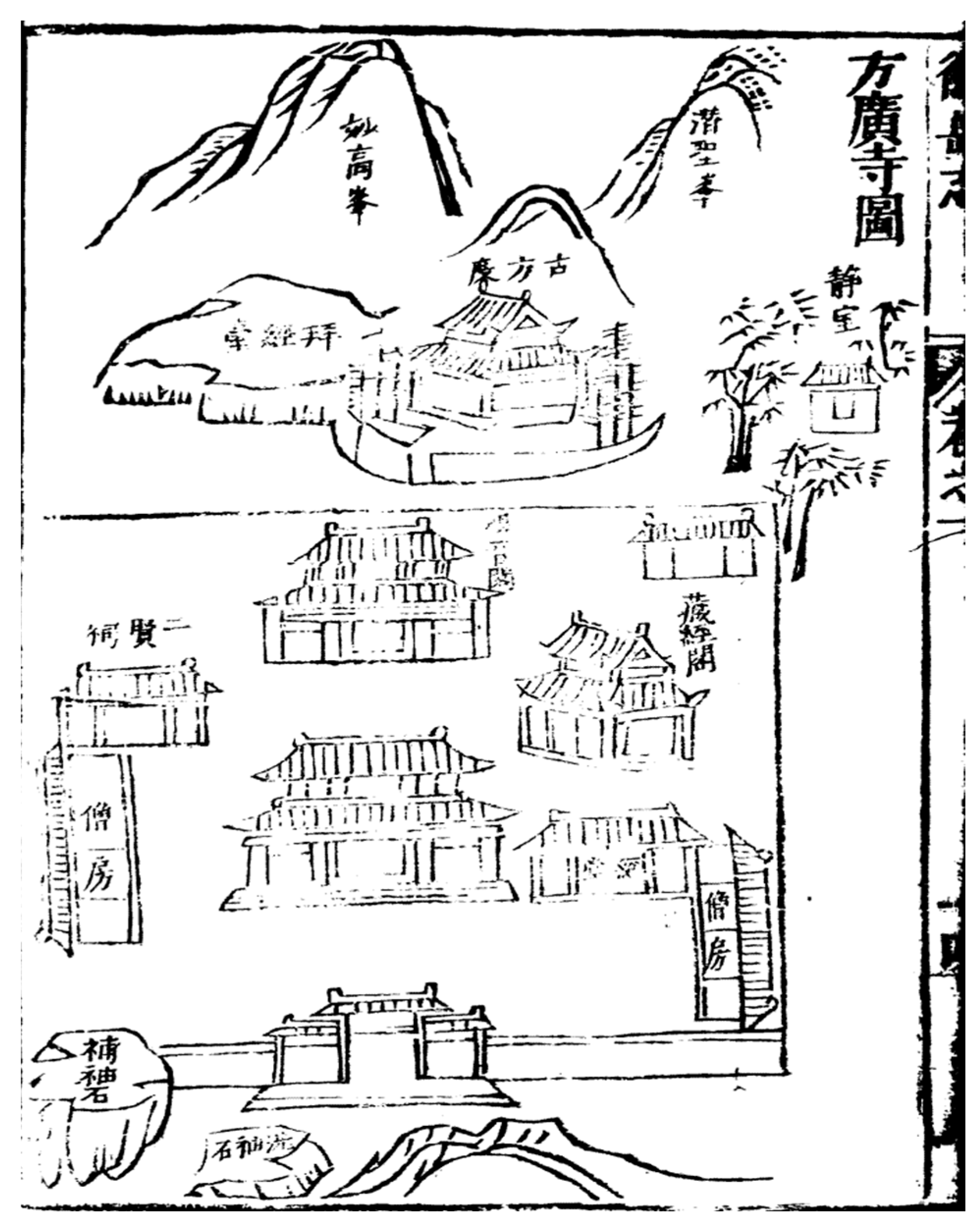

| 4 | See Daoxuan’s Zhong Tianzhu Sheweiguo Qihuansi tu jing 中天竺舍衛國祇洹寺圖經 (Diagram and Sūtra on the Jetavana Temple of Vaiśālī in Central India), which includes a sketch of his vision of the ideal monastery, the Jetavana monastery in India, where the Buddha lived and preached (Ho 1995). See (Teiser 2006, pp. 140–41) for descriptions of the individual buildings within the complex. |

| 5 | On Daoxuan’s inclusion of bath and toilet houses on his diagram, see (Heirman and Torck 2012, pp. 37–40). |

| 6 | Huili 慧立 (615–c. 677) and Yancong 彥悰 (fl. 688), Da Tang da Ciensi sanzang fashi zhuan 大唐大慈恩寺三藏法師傳 (Biography of the “Master of the Three Canons,” Dharma Master [Xuanzang] of Great Cien Monastery [under] the Great Tang), T no. 2053.50: 258a16–17 (translation by He 2013b, p. 71). |

| 7 | Local gazetteers are major sources of information on local monasteries from the Song Dynasty onwards. The term “local gazetteers” was often used collectively to refer to various kinds of geographical texts. These works played a crucial role in reinforcing the links between China’s central government and the provinces. Moreover, they provided vital information on strategic locations and military matters because they included comprehensive reports and maps of the whole empire. As a result, they were produced in vast quantities in China’s provinces. On the historical development of local gazetteers, see, among others, (Hargett 1996). |

| 8 | For a comprehensive study of monastic records and stelae inscriptions composed by literati during the Tang and Song dynasties, see (Halperin 1997, 2006). |

| 9 | For further information on the mid-Tang literati’s development of literary genres while in exile from the capital, see, for instance: (McMullen 1988; Tackett 2014; Shields 2015). |

| 10 | Wenyuan yinghua was compiled by a team of scholars led by Li Fang 李 昉 (925–996) after 980 but not published until 1201–1204. For details of the strategies used in the selection of texts for the Wenyuan yinghua as well as the anthology’s compilation and transmission, see: (Owen 2007, pp. 259–326; Ling 2005). |

| 11 | Tang Wencui was the work of a single compiler, Yao Xuan 姚 铉 (968–1020), who completed it in 1011. His son presented the manuscript to the emperor in 1020, but it was not published until 1039. See (Shields 2017, pp. 306–35) for recent research into this anthology. |

| 12 | The Wenyuan yinghua includes five scrolls of specifically Buddhist ji (juan 817–821). The Tang Wencui boasts a total of nine Buddhist ji on a single scroll (juan 76). |

| 13 | The Wenyuan yinghua contains no fewer than ninteen scrolls of monastic stelae inscriptions (juan 850–868). Five of the Tang Wencui’s total of fifteen scrolls of inscriptions cover Buddhist topics (juan 61–65). It is striking that the sixth-century literary anthology Wen Xuan 文選 (A Selection of Refined Literature), compiled by Xiao Tong 蕭統 (501–531), an important precursor to the Wenyuan yinghua and the Tang Wencui, contains no texts that could be described as ji. Moreover, it contains just five stelae inscriptions, only one of which—the “Toutuosi beiwen” 頭陀寺碑文 (“Stele Inscription for the Toutuo Monastery”), composed by Wang Jin 王巾 (?–505)—was written for a Buddhist monastery. This points to an unprecedented proliferation of both of these literary genres in the Tang era. For more details, see (Sokolova 2021, pp. 40–43). |

| 14 | Jiangnan (literally, “South of the River”) refers to the area south of the Yangtze River that stretches from Suzhou and Hangzhou in the east to Nanchang and Jiujiang in the west. This region provided a safe haven for thousands of intellectuals in the wake of An Lushan’s rebellion. |

| 15 | See Li Yong’s “Da Tang Sizhou Linhuai xian Puguangwangsi bei” 大唐泗州臨淮縣普光王寺碑 (“Stele Inscription for Puguangwang Monastery in Linhuai County in Sizhou of the Great Tang [Dynasty]”), Quan Tang wen 全唐文 263, pp. 2672–73. |

| 16 | Juean 覺岸 (1286–1355), Shishi jigu lüe 釋氏稽古略 (An Outline of Historical Researches into the Śākya Family Lineage), T no. 2037.49: 817c24–25. |

| 17 | This scandal is discussed later in this paper. |

| 18 | Nittō guhōjunrei kōki 4.137. |

| 19 | For a comprehensive study on Li Ao, including his ties with Buddhism, see (Barrett 1992). |

| 20 | Wenyuan yinghua 789, p. 4981; Quan Tang wen 637, p. 6427. The prominent Tang literatus Liang Su 梁肅 (753–793) composed an earlier inscription for the Kaiyuan monastery, as is documented by Cui Gong 崔恭 (?–?) (Tang Wencui 92, pp. 381–82; Wenyuan yinghua 789, p. 49881), but this was probably lost in the fire that destroyed the monastery itself. |

| 21 | (Tang Wencui 85, pp. 291–292; Wenyuan yinghua 688, p. 4269). |

| 22 | (Wenyuan yinghua 688, p. 4269; Quan Tang wen 637, pp. 6423–24). |

| 23 | For a study on Han Yu, see (Hartman 1986). |

| 24 | See Quan Tang shi 全唐詩 342, p. 3831. |

| 25 | Bai Juyi’s inscription for Mingyuan is missing from both the Tang Wencui and the Wenyuan yinghua. A version of the text is included in the Quan Tang wen 678, pp. 6935–6936, but I follow the version contained in the Bai Juyi jijianjiao 白居易集箋校 (ed. Zhu 1988, pp. 3729–30). |

| 26 | There has been extensive research into Bai Juyi’s life and work, as well as his involvement with Buddhism. For the best studies, see: (Chan 1991; Feifel 1961; Xie 1997; Waley 1951; and Seo 1993–1995). |

| 27 | Bai Juyi jijianjiao, p. 3729. |

| 28 | Jianzhen was originally from Guangling 廣陵 in Jiangsu. For his biography, see Zanning 贊寜 (919–1001), Song gaoseng zhuan 宋高僧傳 (Biographies of Eminent Monks [Compiled] under the Song Dynasty), T no. 50.2061: 797a24–c11. |

| 29 | Wenyuan yinghua 789, p. 4981. Quan Tang wen 637, p. 6427. |

| 30 | Quang Tang shi 342, p. 3831. |

| 31 | Typically, only abbots had sufficient authority to commission bells. See (Burdorf 2019, p. 325). |

| 32 | For Wang Zhixing’s biography, see Jiu Tangshu 舊唐書 156, pp. 4138–41. |

| 33 | Han Chong 韓崇, Baotiezhai jinshi wen bawei 寶 鐵 齋 金 石 文 跋 尾 (Colophons on Inscriptions on Bronze and Stone from the Baotiezhai [House]), cited in (Barrett 1992, p. 80). |

| 34 | Song gaoseng zhuan, T no. 2061.50: 737a6. |

| 35 | See the biography of Chengguan in Song gaoseng zhuan, T no. 2061.50: 737a5–6. |

| 36 | For a discussion of this network, see (Hamar 2002, pp. 31–42). |

| 37 | Daoxuan’s Sifen lü 四分律, Dharmaguptaka vinaya (Vinaya in Four Parts; T no. 1428.567), is frequently cited in stelae inscriptions and the biographies in Song gaoseng zhuan as a text that monks were required to study prior to ordination and to qualify as vinaya masters. |

| 38 | Xuanzang 玄奘 (600?–664) translated Vasubandhu’s fifth-century text Jushe lun 俱捨論 (Treasury of the Abhidharma; full title Apidamo jushe lun 阿毘達磨倶舍論; T no. 29.1558), one of the most important classical Indian works on abhidharma, into Chinese in 651. |

| 39 | Bai Juyi jijianjiao, p. 3728. |

| 40 | The Great Monastic Rectifier was a monastic supervisor whose principal responsibility was to maintain the moral standards of his fellow monks and nuns. He was recruited from within the saṃgha and appointed by the emperor. See (Forte 2003) for further details. |

| 41 | Bai Juyi jijianjiao, p. 3928. |

| 42 | Shu Sunju 叔孫矩 (?–?) “Da Tang Yangzhou Liuhexian Lingjusi bei” 大唐揚州六合縣靈居寺碑 (“Stele of the Lingju Monastery in the Lingju County in Yangzhou of the Great Tang [Dynasty]”), Quan Tang wen 745, p. 7714. |

| 43 | Bai juyi jianjiao, p. 3728. |

| 44 | Bai juyi jianjiao, p. 3728. |

| 45 | Jiu Tangshu 156, pp. 4139–40. |

| 46 | A commentary by Hu Sanxing 胡三省 (1230–1302) (Zizhi tongjian 資治通鑑 234, p. 7840) reads: “There is a stūpa of the Great Sage (Sengqie) in Sizhou, it is venerated by the people, therefore Wang Zhixing requested permission to establish an ordination platform right next to it” (泗州有大聖塔,人敬事之, 故王智興請於此置戒壇). According to the Shishi jigu lüe, T no. 2037.49: 835c14–15, Wang Zhixing established the platform in the twelfth month of the fourth year of the Changqing 長慶四年 era (i.e., 824) in honor of the emperor’s birthday. |

| 47 | See Li Deyu 李德裕 (787–859), “Wang Zhixing du sengni zhuang” 王智興度僧尼狀 (“Memorial on the Ordination of Buddhist Monks and Nuns by Wang Zhixing”), Quan Tang wen 706, pp. 7242–43. For English translations, see (Weinstein 1987, pp. 60–61; Barrett 2005, pp. 103–4). |

| 48 | See Cefu yuangui 册府元龜 689, p. 7940. |

| 49 | See Cefu yuangui 689, p. 7940. |

| 50 | Bai Juyi jijianjiao, p. 3928. |

| 51 | Bai Juyi jijianjiao, p. 3928. |

| 52 | The precise meanings of zang 臧 and huo 獲 are uncertain here, although both were used as abusive terms for slaves. Pu (2016) has demonstrated that individual monks and monasteries acquired slaves during the Tang Dynasty, and the Chang’an’s slave-market was the largest in the world at the time. It seems highly likely that Sizhou, which was an important center of trans-Asian trade during the Tang era, would have had a similar market. |

| 53 | The four groups of every monastic community: monks, nuns, male devotees, and female devotees. |

| 54 | Bai Juyi jijianjiao, pp. 3928–29. |

| 55 | Bai Juyi jijianjiao, p. 3929. |

| 56 | Bai Juyi jijianjiao, p. 3929. |

| 57 | On the history of the Kaiyuan monastery during the Song Dynasty, see (Zhang 2012–2013). |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sokolova, A. Building and Rebuilding Buddhist Monasteries in Tang China: The Reconstruction of the Kaiyuan Monastery in Sizhou. Religions 2021, 12, 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040253

Sokolova A. Building and Rebuilding Buddhist Monasteries in Tang China: The Reconstruction of the Kaiyuan Monastery in Sizhou. Religions. 2021; 12(4):253. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040253

Chicago/Turabian StyleSokolova, Anna. 2021. "Building and Rebuilding Buddhist Monasteries in Tang China: The Reconstruction of the Kaiyuan Monastery in Sizhou" Religions 12, no. 4: 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040253

APA StyleSokolova, A. (2021). Building and Rebuilding Buddhist Monasteries in Tang China: The Reconstruction of the Kaiyuan Monastery in Sizhou. Religions, 12(4), 253. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12040253