Transcriptome and Metabolome-Based Analysis of Carbon–Nitrogen Co-Application Effects on Fe/Zn Contents in Dendrobium officinale and Its Metabolic Molecular Mechanisms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Materials and Treatment

2.2. Determination of Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism Indicators

2.2.1. Trace Elements Fe, Zn, Cu Content Determination

2.2.2. Determination of Nitrate Nitrogen Content

2.2.3. Determination of Soluble Protein Content

2.2.4. Determination of Citric Acid Content

2.3. Non-Targeted Metabolomics Determination

2.4. Transcriptome Sequencing

2.5. Data Processing

2.5.1. Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism Data Processing and Analysis

2.5.2. Metabolome Data Processing and Analysis

2.5.3. Transcriptome Data Processing and Analysis

3. Result

3.1. Carbon and Nitrogen Combined Application on the Fe Content in the Stems of D. officinale

3.2. Combined Application of Carbon and Nitrogen on Zn Content in Stems of D. officinale

3.3. Combined Application of Carbon and Nitrogen on Cu Content in Stems of D. officinale

3.4. Combined Application of Carbon and Nitrogen on the Contents of Nitrate Nitrogen, Soluble Protein, and Citric Acid in D. officinale

3.5. Metabolomics Analysis

3.5.1. Sample Correlation Analysis

3.5.2. PCA of Total Samples

3.5.3. Differential Metabolite Analysis

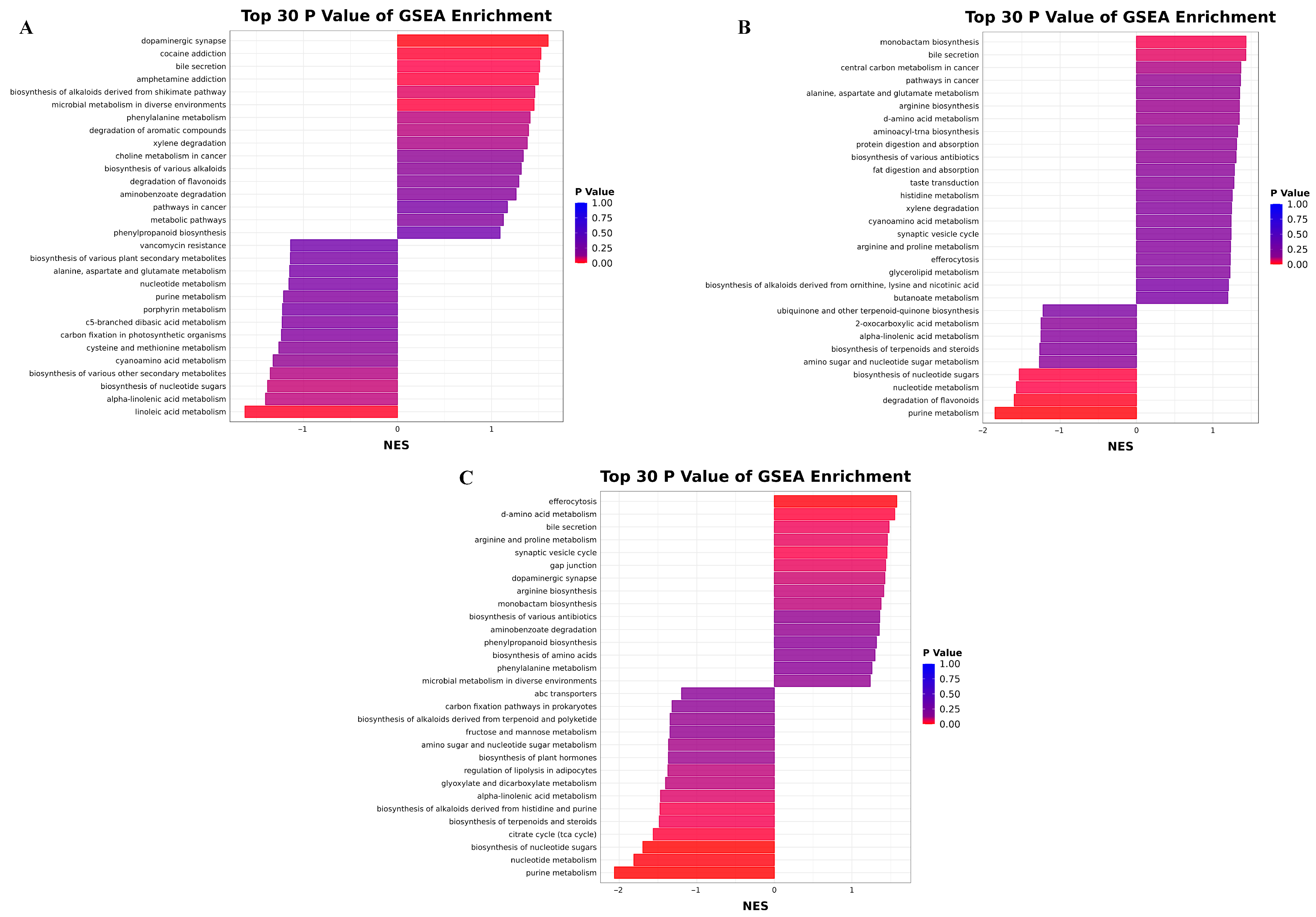

3.5.4. KEGG Enrichment Pathway Analysis

3.6. Transcriptome Analysis

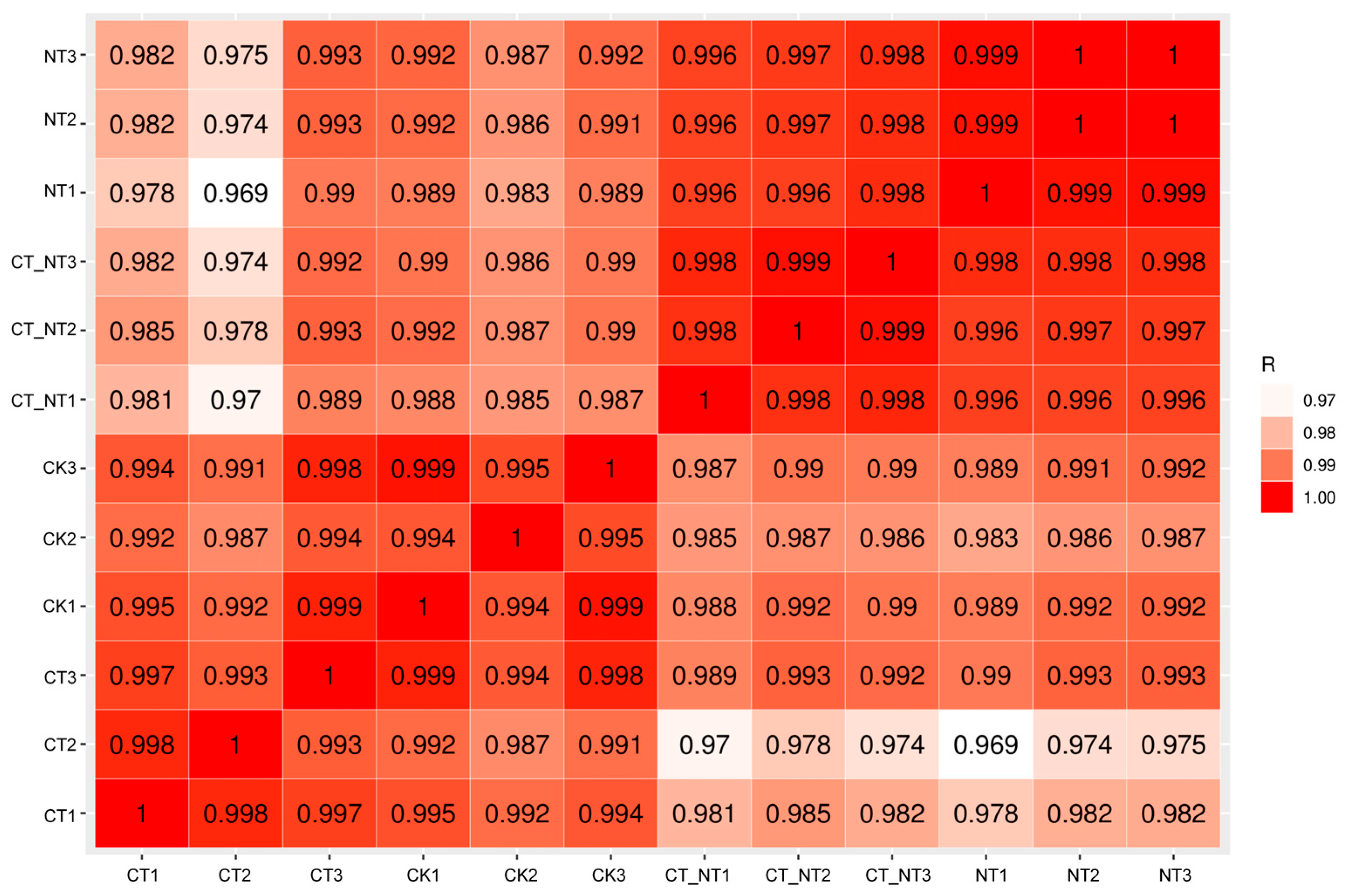

3.6.1. Illumina Sequencing and Correlation Between Samples

3.6.2. Differential Gene Expression Analysis

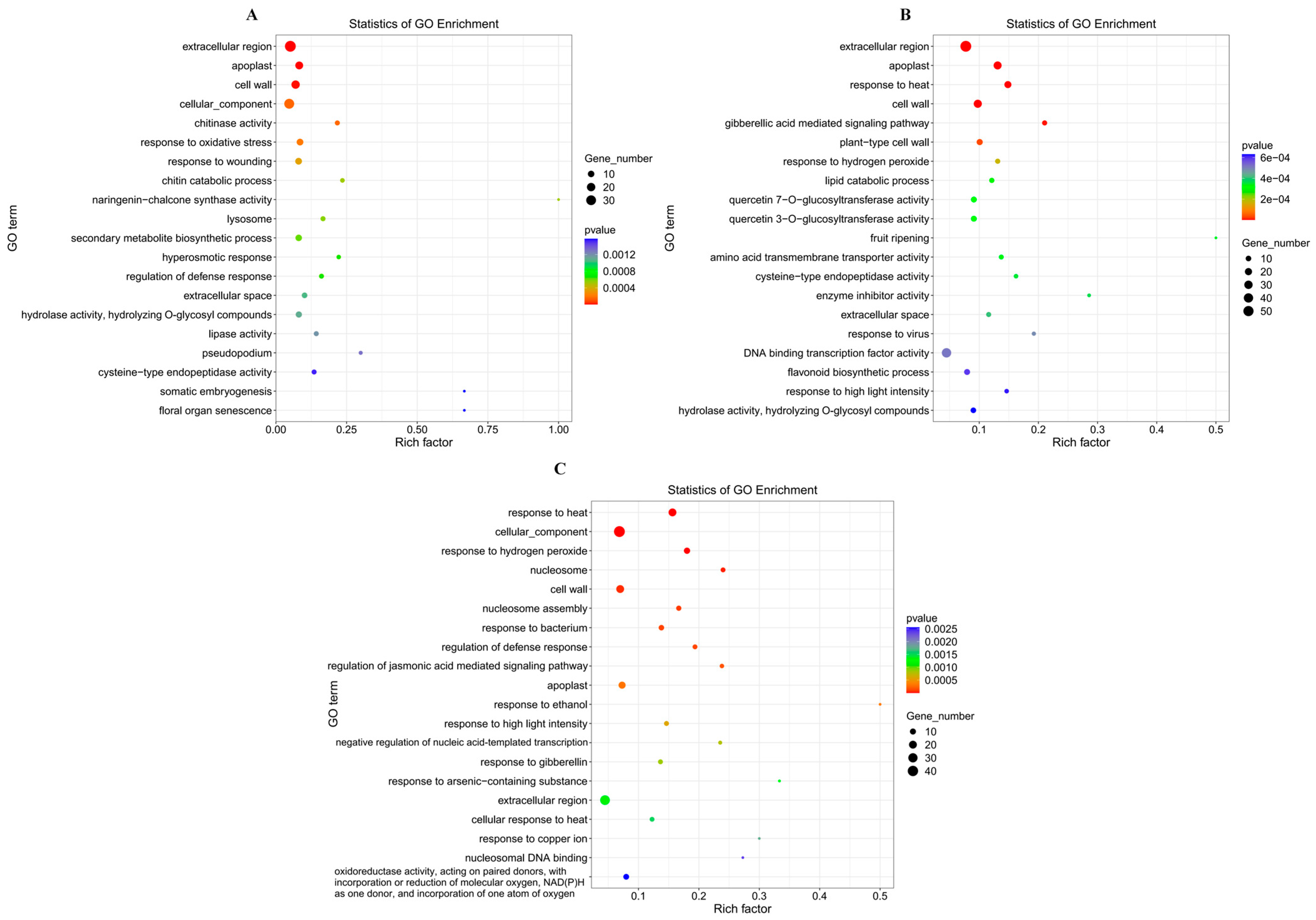

3.6.3. GO Enrichment Analysis

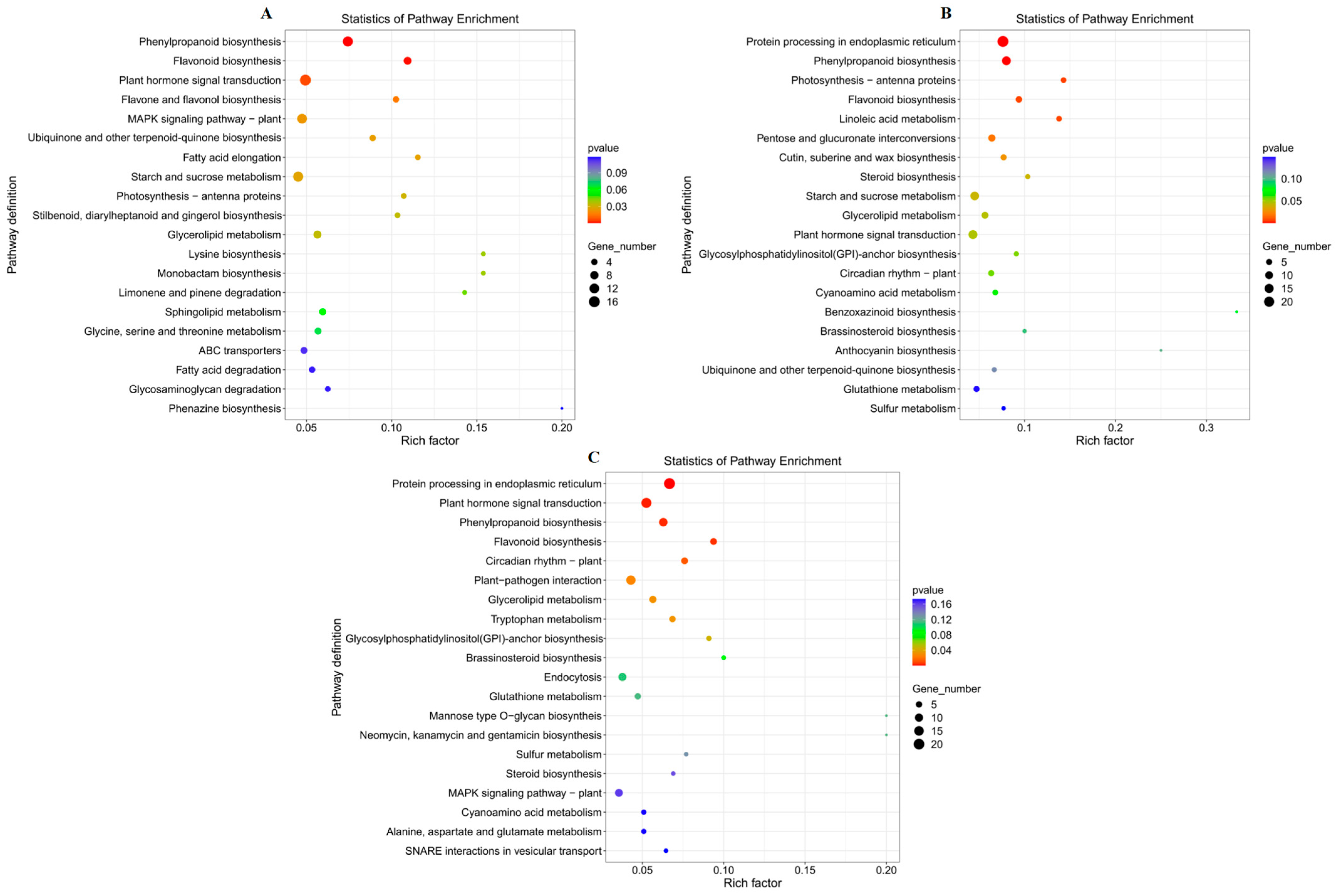

3.6.4. KEGG Enrichment Analysis

3.7. Transcriptome and Metabolome Joint Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Physiological Effects of Combined Carbon and Nitrogen Application on Fe and Zn Contents in Stems of D. officinale

4.2. Effect of AKG on Fe Content in Stems of D. officinale

4.3. Combined Application of Carbon and Nitrogen on D. officinale Stem Zn Content

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, L.; Duan, S.; Huang, J.; Hu, L.; Liu, S.; Lan, Q.; Wei, G. Integrated metabolomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals variation in the metabolites of Dendrobium officinale, Dendrobium huoshanense, Dendrobium nobile. Phytochem. Anal. PCA 2024, 36, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, W.N.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, H.; An, D.; Gui, C.; Ming, T.; Zeng, X. Effects of element deficiency and deficiency recovery on tissue culture seedlings of Dendrobium officinale. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 2024, 33, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J. A brief discussion on the functions and techniques of rational fertilization for crops. Friends Farmers Get. Rich. 2017, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes-Nesi, A.; Fernie, A.R.; Stitt, M. Metabolic and Signaling Aspects Underpinning the Regulation of Plant Carbon Nitrogen Interactions. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 973–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.C.; Pan, Y.Z.; Yang, Y.N.; Xian, X.L.; Chen, R.; Li, S.L. Effects of combined application of nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium fertilizers on flowering traits and contents of chlorophyll and nutrient elements in leaves of Osmanthus fragrans ‘Jinyu Taige’. J. J. Plant Resour. Environ. 2017, 26, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.Y. Nitrogen in plants: From nutrition to the modulation of abiotic stress adaptation. Stress Biol. 2022, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Chen, R.Y.; Liu, H.C.; Song, S.W.; Su, W.; Sun, G.W. Effects of Organic Carbon Fertilizer on Growth, Quality, and Metabolizing Enzymes Activities of Carbon and Nitrogen in Lettuce. China Veg. 2023, 1, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Xu, J.; Wang, X.; Fu, H.; Zhao, M.; Wang, H.; Shi, L. Photosynthetic characteristics and metabolic analyses of two soybean genotypes revealed adaptive strategies to low-nitrogen stress. J. Plant Physiol. 2018, 229, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, L.X.; Wang, P. Determination of C-N Metabolism Indices in Ear-leaf of Maize (Zea mays L.). Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2009, 25, 155–157. [Google Scholar]

- Sookoian, S.; Pirola, C.J. Liver enzymes, metabolomics and genome-wide association studies: From systems biology to the personalized medicine. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.B.; Ma, Z.Y.; Ding, Z.J.; Zheng, S.J. Research progresses on molecular mechanisms of storage, transportation and reutilization of plant seed iron. J. Zhejiang Univ. Agric. Life Sci. 2021, 47, 473–480. [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru, Y.; Suzuki, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Takahashi, M.; Nakanishi, H.; Mori, S.; Nishizawa, N.K. OsZIP4, a novel zinc-regulated zinc transporter in rice. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 3207–3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, P.; Chen, X.; Liao, Z.W.; Wang, L.M.; Zhong, X.J.; Mao, X.Y. Effect of organic carbon on carbon and nitrogen metabolism and the growth of water spinach as affected by soil nitrogen levels. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2016, 53, 746–756. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.X.; Jiang, Y.L.; He, Y.X.; Chen, Y.F.; Teng, Y.B.; Chen, Y.X.; Zhang, C.C.; Zhou, C.Z. Structural basis for the allosteric control of the global transcription factor NtcA by the nitrogen starvation signal 2-oxoglutarate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12487–12492. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.L.; Hu, J.X.; Chen, Y.X.; Zheng, B.S.; Yan, D.L. Effects of external application of α-ketoglutarate on growth, carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus accumulation and their stoichiometric relationships in Kosteletzkya virginica under salt stress. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2023, 25, 170–177. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, D.F.; Zeng, L.M.; Yao, K.; Kong, X.F.; Wu, G.Y.; Yin, Y.L. The glutamine-alpha-ketoglutarate (AKG) metabolism and its nutritional implications. Amino Acids 2016, 48, 2067–2080. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.T.; Chen, J.B.; Yuan, H.W.; Zheng, B.S.; Yan, D.L. Effects of foliar spraying organic carbon on carbohydrate metabolism and Fe, Zn content of Dendrobium officinale. Ecol. Sci. 2021, 40, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Kolberg, F.; Tóth, B.; Rana, D.; Arcoverde, C.; Gerényi, A.; Solti, Á.; Szalóki, I.; Sipos, G.; Fodor, F. Iron Status Affects the Zinc Accumulation in the Biomass Plant Szarvasi-1. Plants 2022, 11, 3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Millán, F.; Duy, D.; Philippar, K. Chloroplast Iron Transport Proteins—Function and Impact on Plant Physiology. J. Frontiers in Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 178. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq, S.; Ali, A.; Sajjad, Y.; Zeb, Q.; Shahzad, M.; Khan, A.; Nazir, R.; Widemann, E. The Interplay between Toxic and Essential Metals for Their Uptake and Translocation Is Likely Governed by DNA Methylation and Histone Deacetylation in Maize. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6959. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.M.; Gui, R.F.; Li, W.; Gao, Z.F.; Ashraf, U.; Tan, J.T.; Ye, Q.Y.; Chen, J.L.; Xie, H.J.; Mo, Z.W. Nitrogen and α-Ketoglutaric Acid Application Modulate Grain Yield, Aroma, Nutrient Uptake and Physiological Attributes in Fragrant Rice. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 40, 1613–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, A.A. Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP MS): A versatile tool. J. Mass Spectrom. 2007, 42, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, D.A.; Maroon, M.; Schrader, L.E.; Youngs, V.L. Rapid colorimetric determination of nitrate in plant tissue by nitration of salicylic acid. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 1975, 6, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapan, C.V.; Lundblad, R.L.; Price, N.C. Colorimetric protein assay techniques. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 1999, 29, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartford, C.G. Rapid spectrophotometric method for the determination of itaconic, citric, aconitic, and fumaric acids. Anal. Chem. 1962, 34, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Jin, C.G.; Ren, X.Y.; Fei, X.; Zhao, Q.; Pan, X.J.; Wu, Z.G.; Jiang, C.X. Flavonoid compound differences in Dendrobium officinale under different cultivation modes analyzed using UPLC-MS/MS-based Metabolomics technology. Chin. Tradit. Herb. Drugs 2022, 53, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Toubiana, D.; Xue, W.T.; Zhang, N.Y.; Kremling, K.; Gur, A.; Pilosof, S.; Gibon, Y.; Stitt, M.; Buckler, E.S.; Fernie, A.R.; et al. Correlation-Based Network Analysis of Metabolite and Enzyme Profiles Reveals a Role of Citrate Biosynthesis in Modulating Nand Metabolism in Zea mays. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.H.; Zhang, R.F.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Li, W.M.; Zhang, Y.S.; Zhang, M.W.; Yang, X.Z.; Yang, H.S. Improving maize carbon and nitrogen metabolic pathways and yield with nitrogen application rate and nitrogen forms. PeerJ 2024, 12, e16548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seck-Mbengue, M.F.; Müller, A.; Ngwene, B.; George, E. Transport of nitrogen and zinc to rhodes grass by arbuscular mycorrhiza and roots as affected by different nitrogen sources (NH4+-N and NO3−-N). Symbiosis 2017, 73, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamnér, K.; Weih, M.; Eriksson, J.; Kirchmann, H. Influence of nitrogen supply on macro- and micronutrient accumulation during growth ofwinter wheat. Field Crops Res. 2017, 213, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Zhang, D.; Sun, W.; Wang, T.Z. The Adaptive Mechanism of Plants to Iron Deficiency via Iron Uptake, Transport, and Homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, M.S.; Masuda, H.; Kobayashi, T.; Nishizawa, N.K. Physiological and transcriptomic analysis of responses to different levels of iron excess stress in various rice tissues. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2018, 64, 370–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.B.; Wang, X.; Bai, J.Y.; Wei, T.; Sun, M.L.; Zhu, L.; Wang, M.L.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, W. The kinase CIPK11 functions as a positive regulator in cadmium stress response in Arabidopsis. Gene 2021, 772, 145372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moy, A.; Nkongolo, K. Decrypting Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Counteracting Copper and Nickel Toxicity in Jack Pine (Pinus banksiana) Based on Transcriptomic Analysis. Plants 2024, 13, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lan, P. The Understanding of the Plant Iron Deficiency Responses in Strategy I Plants and the Role of Ethylene in This Process by Omic Approaches. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jie, H.D.; He, P.L.; Zhao, L.; Ma, Y.S.; Jie, Y.C. Molecular Mechanisms Regulating Phenylpropanoid Metabolism in Exogenously-Sprayed Ethylene Forage Ramie Based on Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analyses. Plants 2023, 12, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.-J.; He, J.-M.; Kong, J.-Q. Characterization of two flavonol synthases with iron-independent flavanone 3-hydroxylase activity from Ornithogalum caudatum Jacq. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringlis, I.A.; De Jonge, R.; Pieterse, C.M.J. The Age of Coumarins in Plant–Microbe Interactions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019, 60, 1405–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K.; Yonekura-Sakakibara, K.; Nakabayashi, R.; Higashi, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Tohge, T.; Fernie, A.R. The flavonoid biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis: Structural and genetic diversity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 72, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.K.; Pandit, E.; Pawar, S.; Pradhan, A.; Behera, L.; Das, S.R.; Pathak, H. Genetic regulation of homeostasis, uptake, bio-fortification and efficiency enhancement of iron in rice. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 177, 104066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenness, M.K.; Tayengwa, R.; Bate, G.A.; Tapken, W.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Pang, C.X.; Murphy, A.S. Loss of Multiple ABCB Auxin Transporters Recapitulates the Major twisted dwarf 1 Phenotypes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 840260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massafra, A.; Forlani, S.; Periccioli, L.; Rotasperti, L.; Mizzotti, C.; Mariotti, L.; Tagliani, A.; Masiero, S. NAC100 regulates silique growth during the initial phase of fruit development through the gibberellin biosynthetic pathway. Plant Sci. 2025, 352, 112344. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, Y.; Niu, T.T.; Zhang, M.; Fan, C.; Liang, W.W.; Shu, Y.J.; Guo, C.H.; Guo, D.L.; et al. GmABCG5, an ATP-binding cassette G transporter gene, is involved in the iron deficiency response in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1289801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, S.; Shimada, A. Reaction Mechanism of Cytochrome c Oxidase. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 1936–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, T.M.; Feussner, I. Diversity in sphingolipid metabolism across land plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2022, 73, 2785–2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.B.; Yang, L.Y.; Zhu, Q.K.; Wu, H.J.; He, Y.; Liu, Y.D.; Xu, J.; Jiang, D.A.; Zhang, S.Q. Active photosynthetic inhibition mediated by MPK3/MPK6 is critical to effector-triggered immunity. PLoS Biol. 2018, 16, e2004122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FiLiZ, E.; Tombuloğlu, H. Genome-wide distribution of superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene families inSorghum bicolor. Turk. J. Biol. 2015, 39, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Enzymes Involved in Ascorbate Biosynthesis and Metabolism in Plants. In Ascorbic Acid in Plants: Biosynthesis, Regulation and Enhancement; Springer New York: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Guerinot, M.L. The ZIP family of metal transporters. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA). Biomembranes 2000, 1465, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kozak, K.; Papierniak, A.; Barabasz, S.A.; Kendziorek, M.; Palusińska, M.; Williams, L.E.; Antosiewicz, D.M. NtZIP11, a new Zn transporter specifically upregulated in tobacco leaves by toxic Zn level. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2019, 157, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, X.S.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J. SlZIP11 mediates zinc accumulation and sugar storage in tomato fruits. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muro, K.; Segami, S.; Kawachi, M.; Horikawa, N.; Namiki, A.; Hashiguchi, K.; Maeshima, M.; Takano, J. Localization of the MTP4 transporter to trans-Golgi network in pollen tubes of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Plant Res. 2024, 137, 939–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsopoulou, S.V.; Kyriakidis, D.A. Phosphomannose isomerase of Xanthomonas campestris: A zinc activated enzyme. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1997, 177, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Yuan, L.; Xia, M.; Makaroff, C.A. Proper Levels of the Arabidopsis Cohesion Establishment Factor CTF7 Are Essential for Embryo and Megagametophyte, But Not Endosperm, Development. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, A.K.; Jha, S.K.; Agarwal, P.; Mallick, N.; Niranjana, M.; Vinod. Leaf rolling in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is controlled by the upregulation of a pair of closely linked/duplicate zinc finger homeodomain class transcription factors during moisture stress conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1038881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Yoshida, H.; Yano, K.; Kinoshita, S.; Kawai, K.; Koketsu, E.; Hattori, M.; Takehara, S.; Huang, J.; Hirano, K.; et al. OsIDD2, a zinc finger and INDETERMINATE DOMAIN protein, regulates secondary cell wall formation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, S.; Freeman, S.; Zveibil, A.; Yarden, O. A defect in nir1, a nirA -like transcription factor, confers morphological abnormalities and loss of pathogenicity in Colletotrichum acutatum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2006, 7, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primikyri, A.; Mazzone, G.; Lekka, C.; Tzakos, A.G.; Russo, N.; Gerothanassis, L.P. Understanding Zinc(II) Chelation with Quercetin and Luteolin: A Combined NMR and Theoretical Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Arif, Y.; Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. The role of quercetin in plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 166, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wang, B.; Zhu, L. DNA binding, cytotoxicity, apoptotic inducing activity, and molecular modeling study of quercetin zinc(II) complex. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Gao, T.; Zhao, Q.; Ma, C.; Ma, F. Effects of Exogenous Dopamine on the Uptake, Transport, and Resorption of Apple Ionome Under Moderate Drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibl, J.K.; Abdallah, Z.; Ross, G.M. Zinc–metallothionein: A potential mediator of antioxidant defence mechanisms in response to dopamine-induced stressThis review is one of a selection of papers published in a Special Issue on Oxidative Stress in Health and Disease. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2010, 88, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment Group | Name | Fertilization Treatment | Treatment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | CK | Deionized water | Deionized water every 3 days AKG every 3 days Urea every 7 days |

| AKG treatment | CT | 20 mg·L−1 AKG solution | |

| Urea treatment | NT | 0.2% urea solution | |

| AKG and urea combined treatment | CT_NT | 20 mg·L−1 AKG solution and 0.2% urea solution |

| Treatment Group | Total Identification Results of Metabolites | Total Number of Metabolites with Significant Differences | Total Number of Metabolites Significantly Upregulated | Total Number of Metabolites Significantly Downregulated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT vs. CK | 973 | 171 | 83 | 88 |

| NT vs. CK | 973 | 211 | 123 | 88 |

| CT_NT vs. CK | 973 | 230 | 116 | 114 |

| CT_NT vs. NT | 973 | 190 | 75 | 115 |

| CT_NT vs. CT | 973 | 199 | 101 | 98 |

| CT vs. NT | 973 | 239 | 99 | 140 |

| Sample | Raw_Reads | Raw_Bases | Valid_Reads | Valid_Bases | Valid% | Q20% | Q30% | GC% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT1 | 38,582,966 | 5.79 G | 37,450,586 | 5.52 G | 97.07 | 98.13 | 94.31 | 46.90 |

| CT2 | 41,541,784 | 6.23 G | 40,268,372 | 5.93 G | 96.93 | 98.18 | 94.47 | 46.81 |

| CT3 | 40,251,062 | 6.04 G | 39,077,422 | 5.76 G | 97.08 | 98.23 | 94.64 | 46.76 |

| CK1 | 40,904,976 | 6.14 G | 39,709,836 | 5.86 G | 97.08 | 98.14 | 94.34 | 46.88 |

| CK2 | 56,387,648 | 8.46 G | 53,719,034 | 7.89 G | 95.27 | 98.21 | 94.45 | 46.22 |

| CK3 | 40,269,572 | 6.04 G | 39,047,598 | 5.75 G | 96.97 | 98.21 | 94.53 | 46.62 |

| CT_NT1 | 53,990,186 | 8.10 G | 51,378,602 | 7.55 G | 95.16 | 98.01 | 93.92 | 47.09 |

| CT_NT2 | 41,454,772 | 6.22 G | 40,815,580 | 6.05 G | 98.46 | 98.71 | 95.99 | 46.59 |

| CT_NT3 | 40,878,620 | 6.13 G | 39,571,214 | 5.83 G | 96.80 | 98.14 | 94.36 | 46.96 |

| NT1 | 40,181,716 | 6.03 G | 39,231,226 | 5.79 G | 97.63 | 98.20 | 94.55 | 46.97 |

| NT2 | 42,100,920 | 6.32 G | 41,063,584 | 6.06 G | 97.54 | 98.17 | 94.49 | 46.93 |

| NT3 | 53,825,920 | 8.07 G | 52,125,152 | 7.69 G | 96.84 | 98.16 | 94.27 | 47.02 |

| DB | All | GO | KEGG | Pfam | Swissprot | eggNOG | NR | TF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Num | 42,491 | 18,169 | 7089 | 17,187 | 14,834 | 20,660 | 24,821 | 1262 |

| Ratio (%) | 100.00 | 42.76 | 16.68 | 40.45 | 34.91 | 48.62 | 58.41 | 2.97 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yan, D.; Xiang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Li, T.; Zheng, B. Transcriptome and Metabolome-Based Analysis of Carbon–Nitrogen Co-Application Effects on Fe/Zn Contents in Dendrobium officinale and Its Metabolic Molecular Mechanisms. Agriculture 2026, 16, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010029

Yan D, Xiang S, Cheng Y, Li T, Zheng B. Transcriptome and Metabolome-Based Analysis of Carbon–Nitrogen Co-Application Effects on Fe/Zn Contents in Dendrobium officinale and Its Metabolic Molecular Mechanisms. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Daoliang, Shang Xiang, Yutang Cheng, Tongyu Li, and Bingsong Zheng. 2026. "Transcriptome and Metabolome-Based Analysis of Carbon–Nitrogen Co-Application Effects on Fe/Zn Contents in Dendrobium officinale and Its Metabolic Molecular Mechanisms" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010029

APA StyleYan, D., Xiang, S., Cheng, Y., Li, T., & Zheng, B. (2026). Transcriptome and Metabolome-Based Analysis of Carbon–Nitrogen Co-Application Effects on Fe/Zn Contents in Dendrobium officinale and Its Metabolic Molecular Mechanisms. Agriculture, 16(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010029