Design and Evaluation of an Automated Rod-Feeding Mechanism for Small Arch Shed Machine Based on Kinematics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

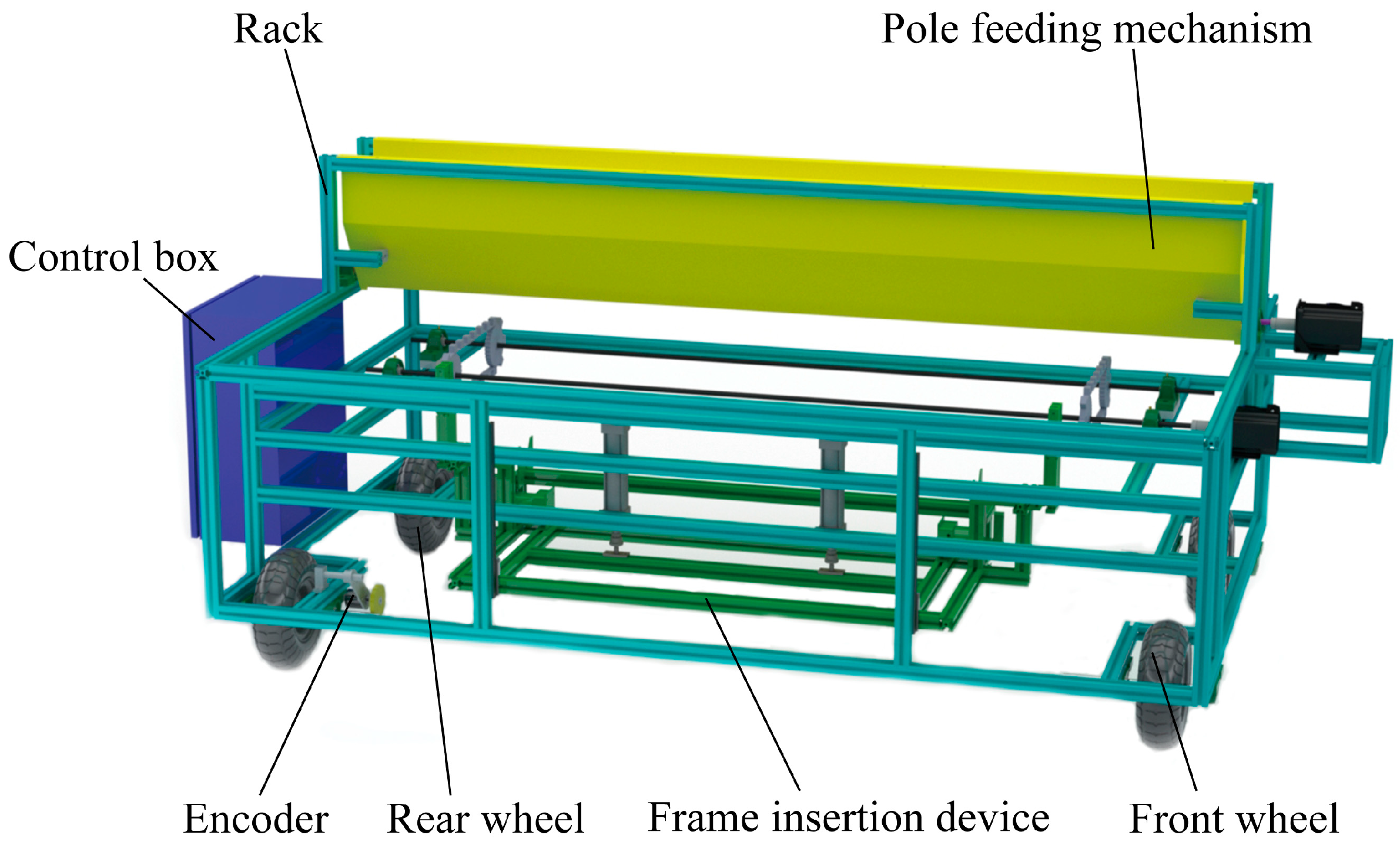

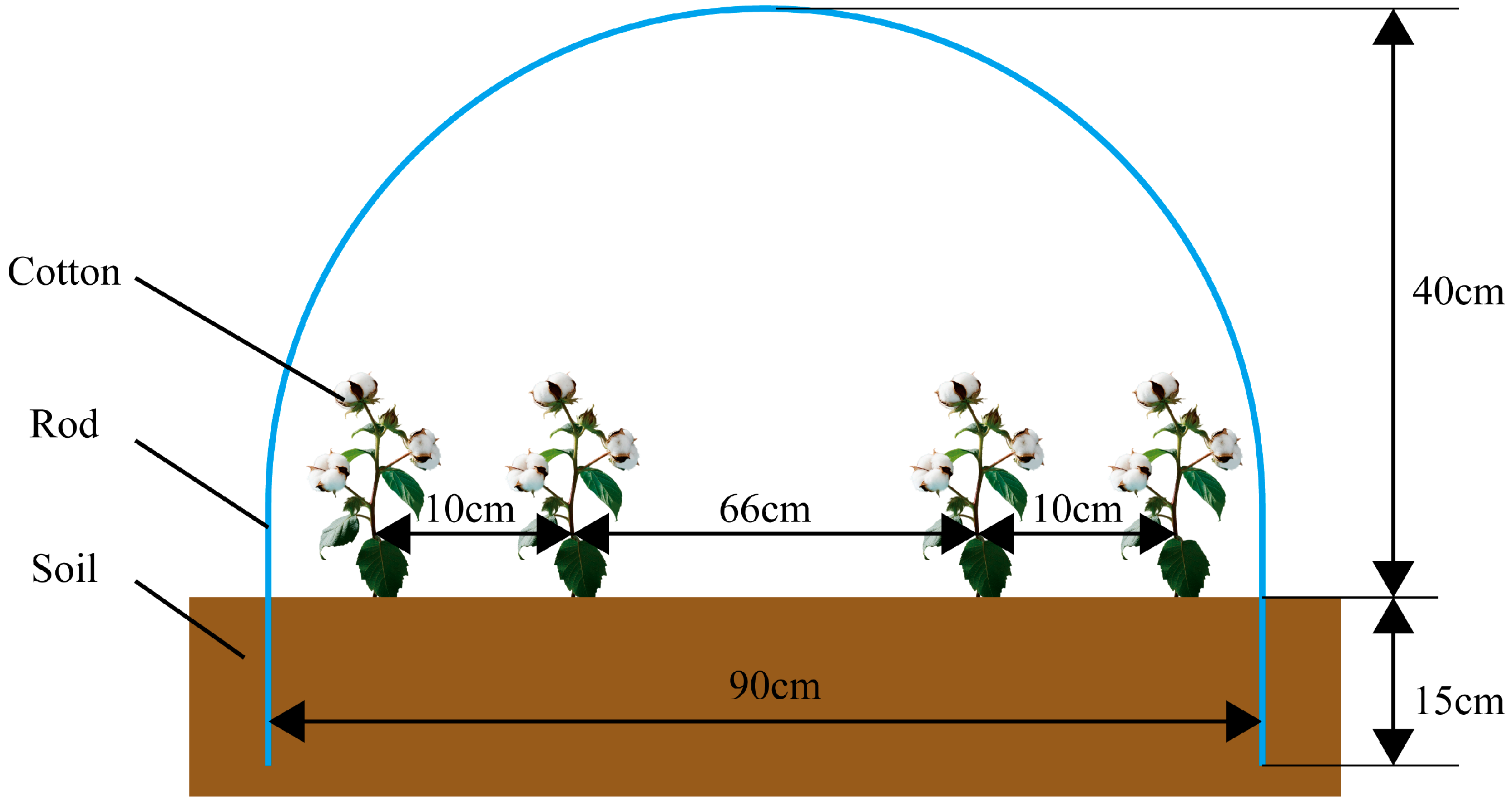

2.1. System Design and Functionality

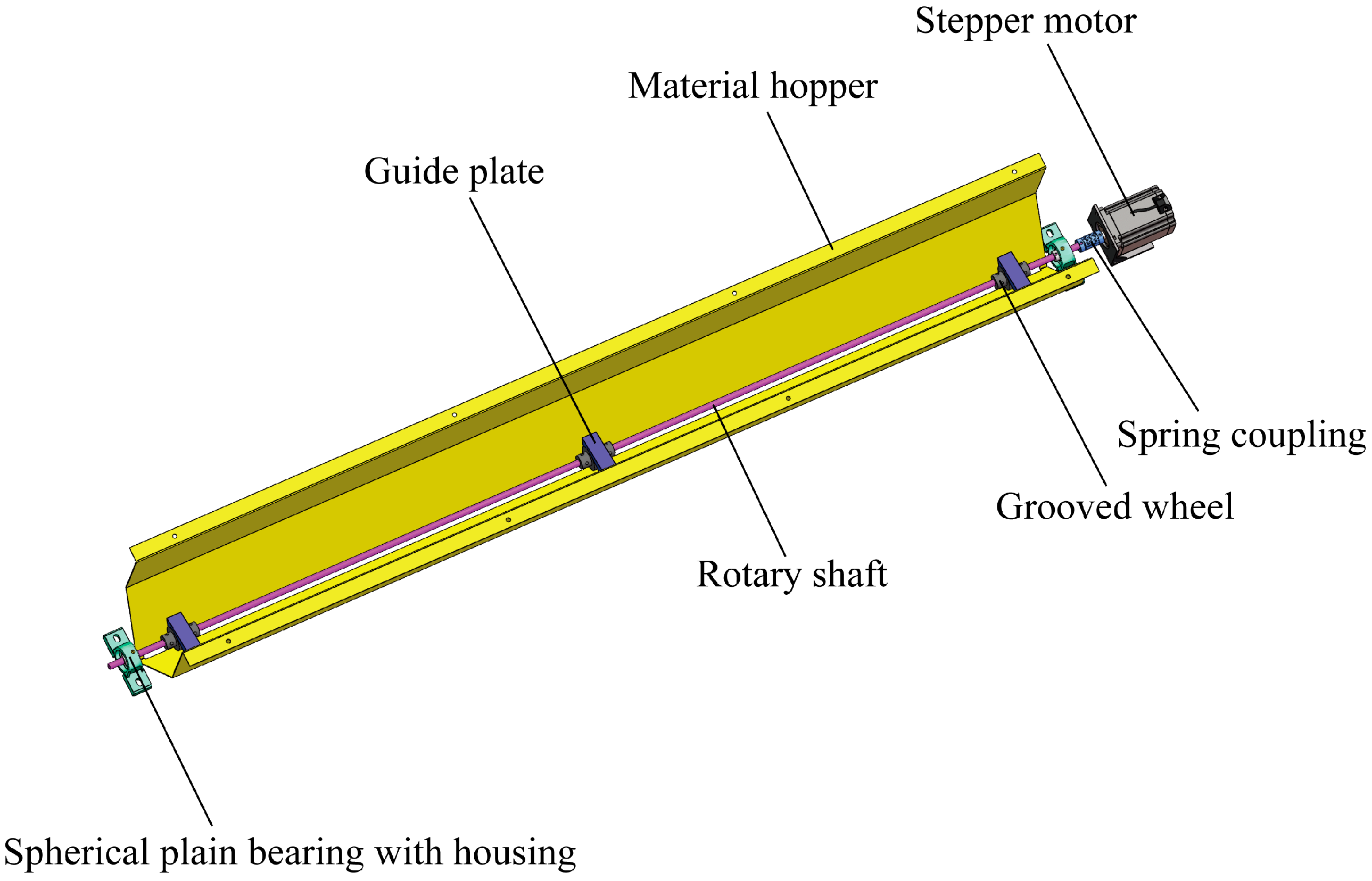

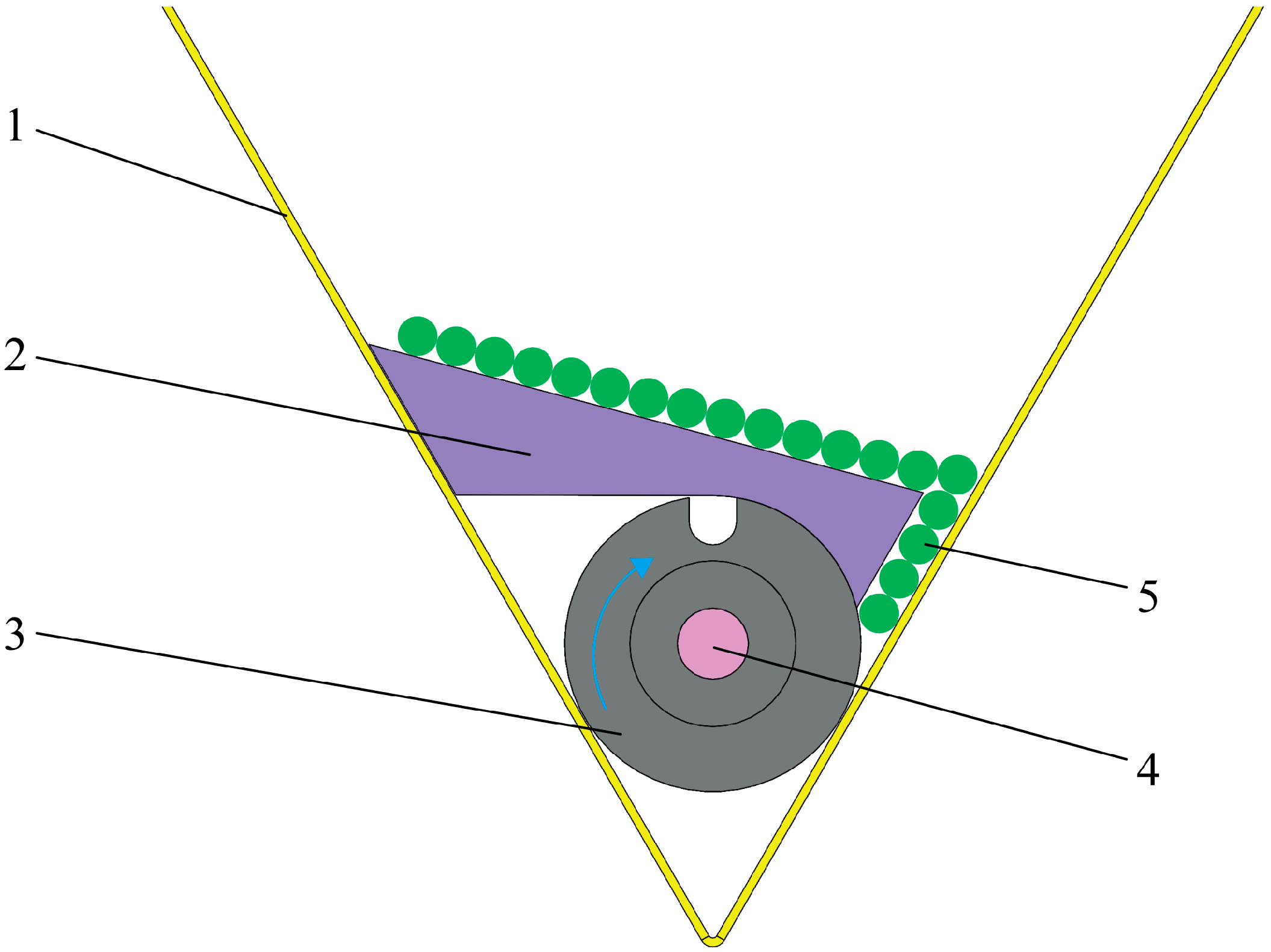

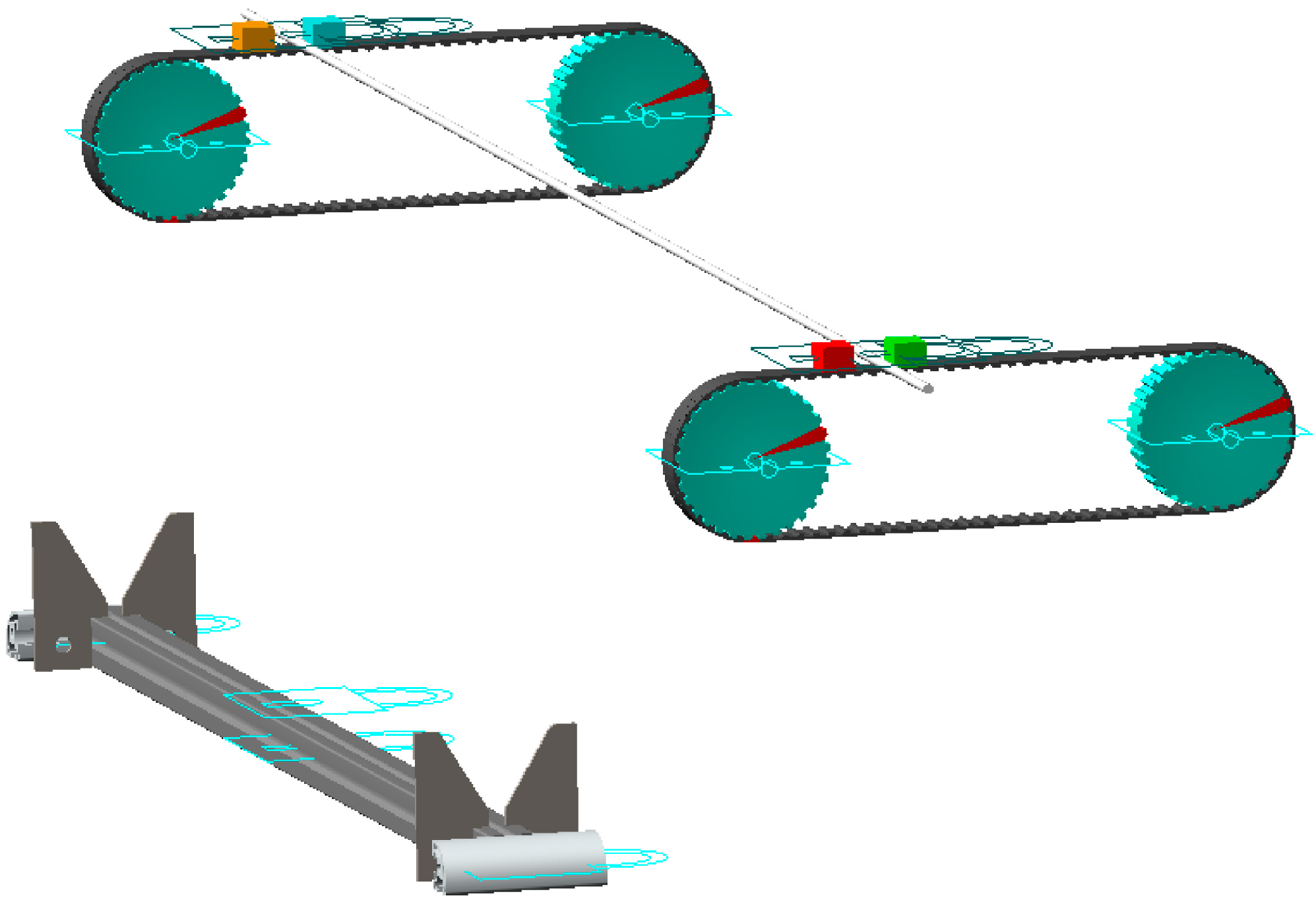

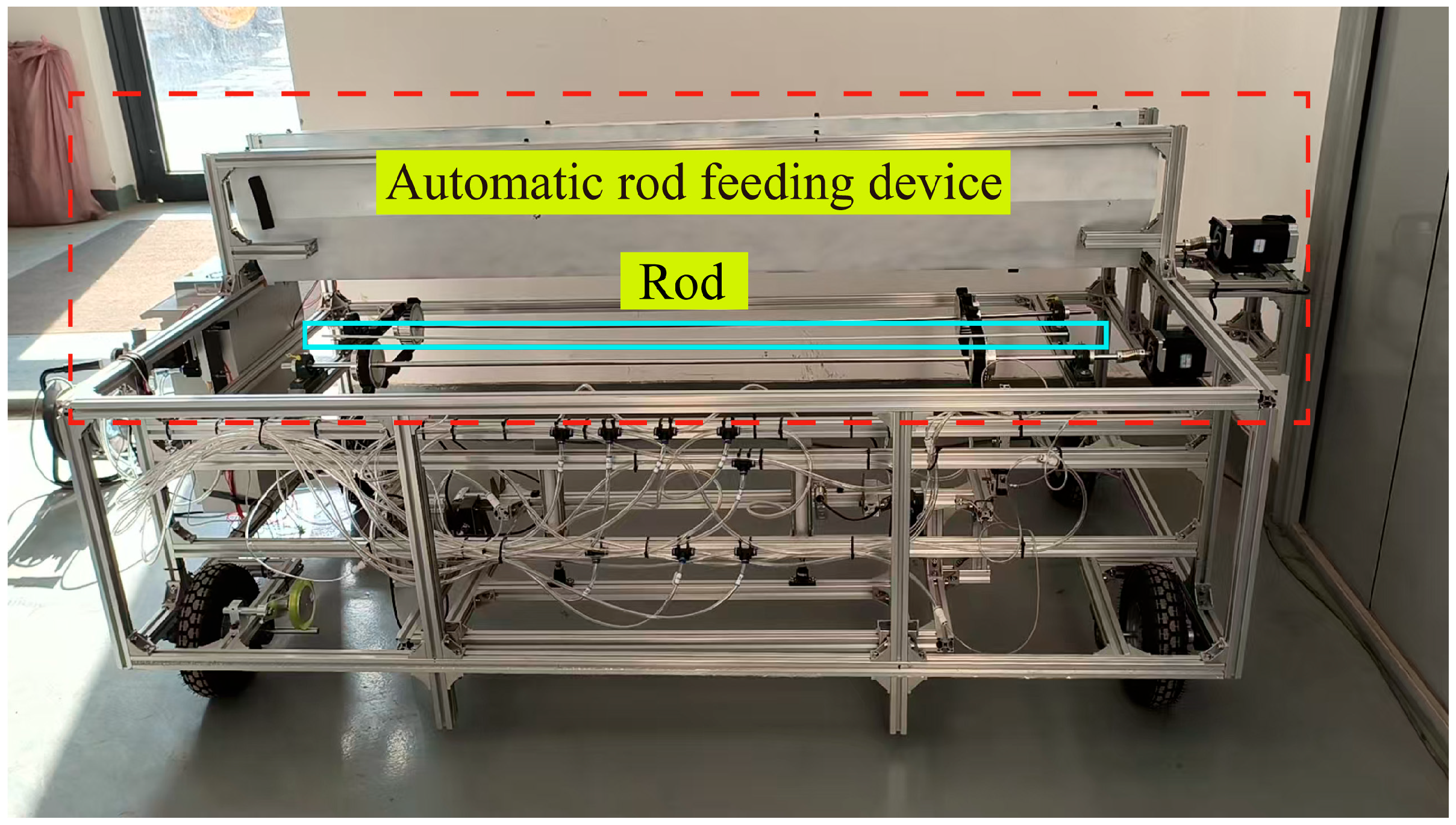

2.1.1. Automatic Rod Feeder

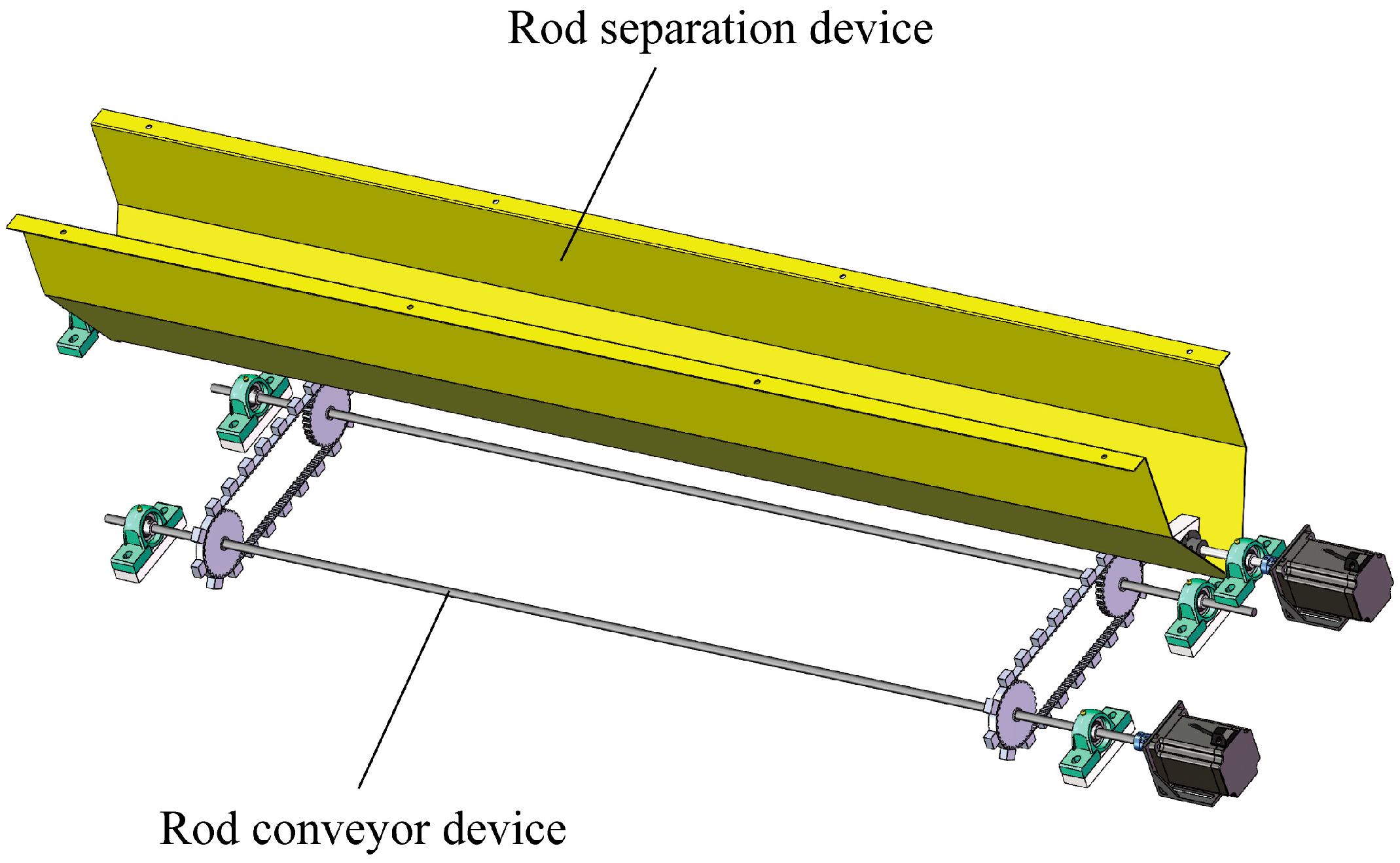

2.1.2. Rod Separation Mechanism

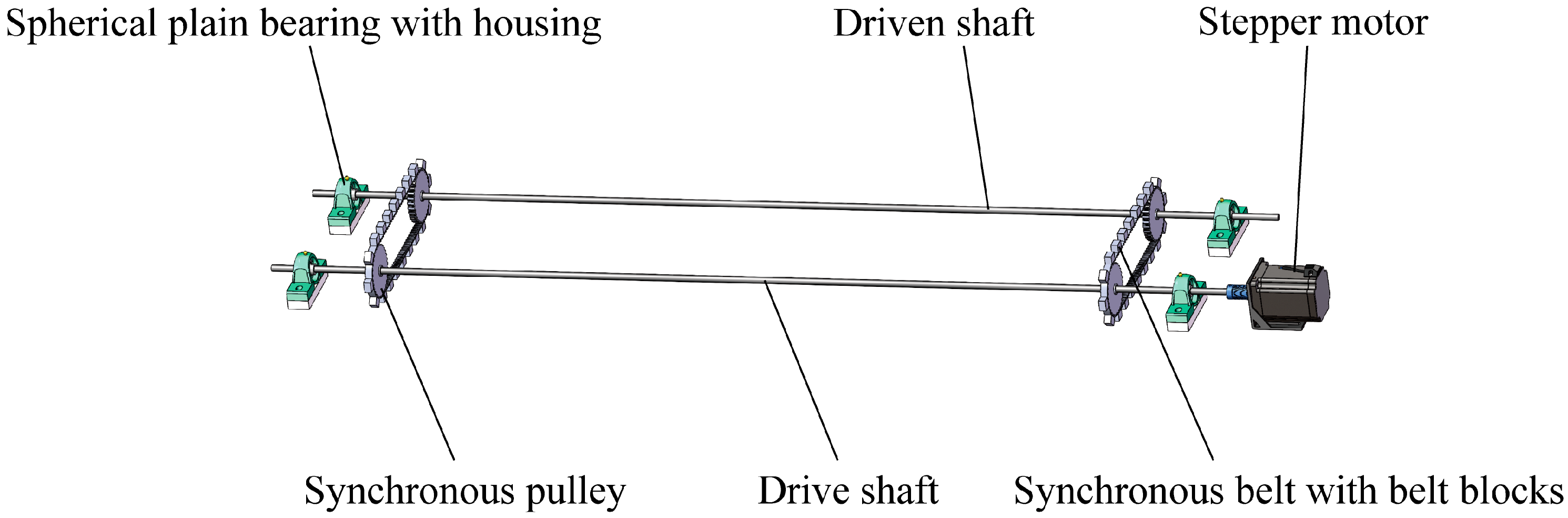

2.1.3. Rod Conveyor Mechanism

2.2. System Performance Test

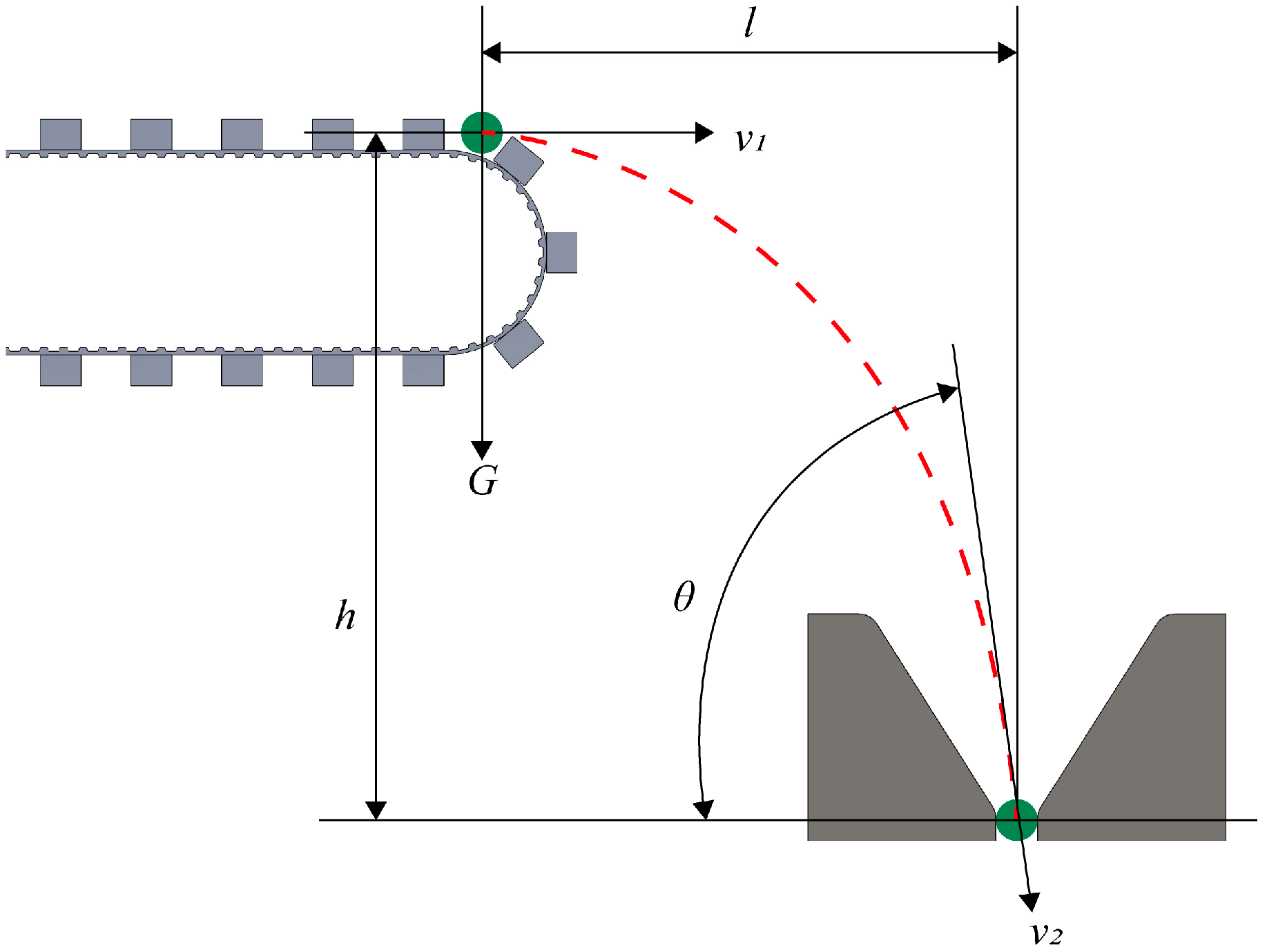

2.2.1. Kinematic Simulation Procedure

2.2.2. Kinematic Simulation Test

2.3. Measurements

3. Results

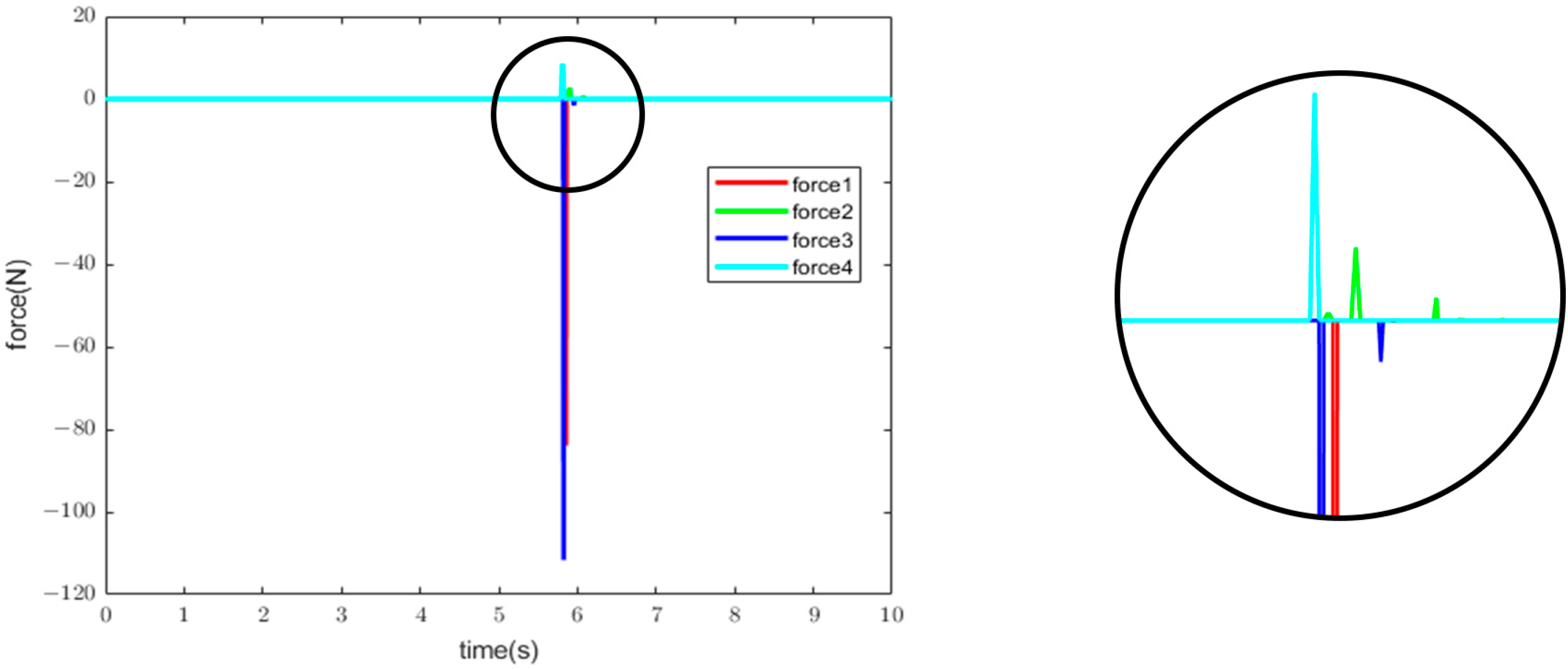

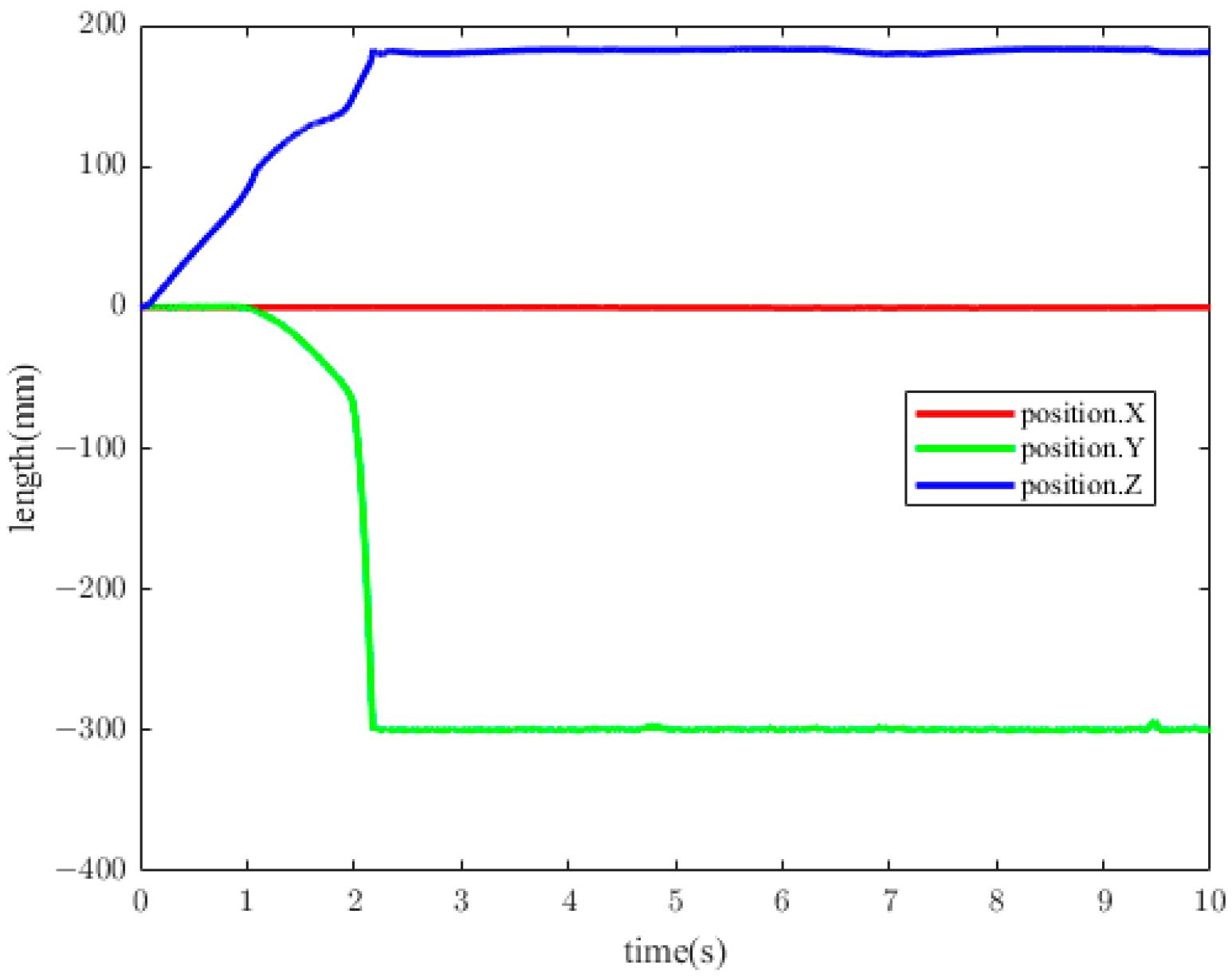

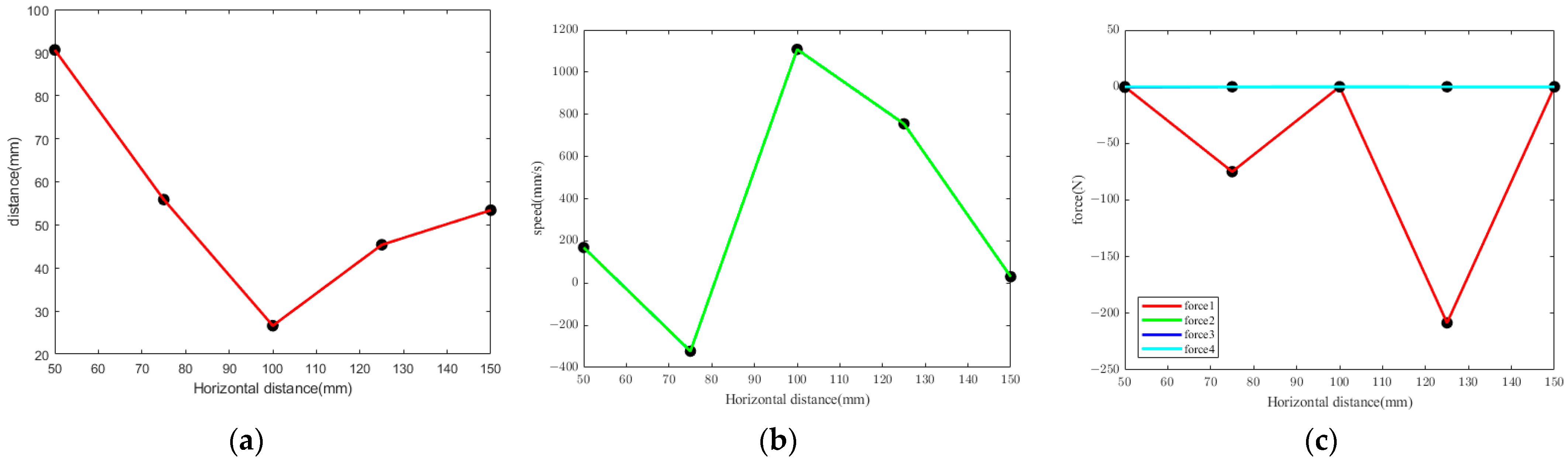

3.1. Kinematic Simulation

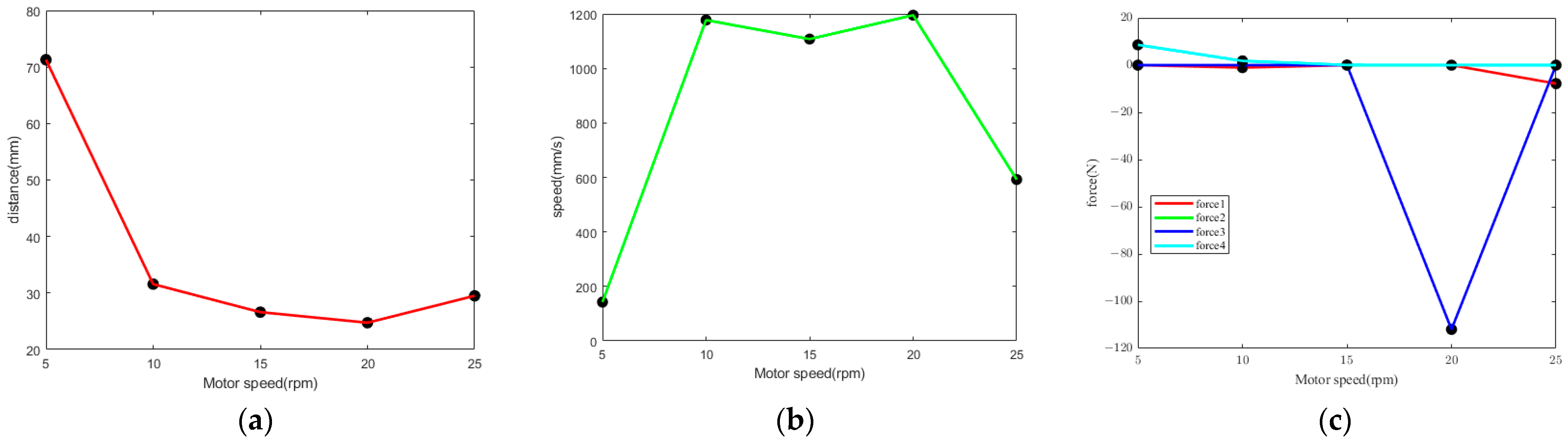

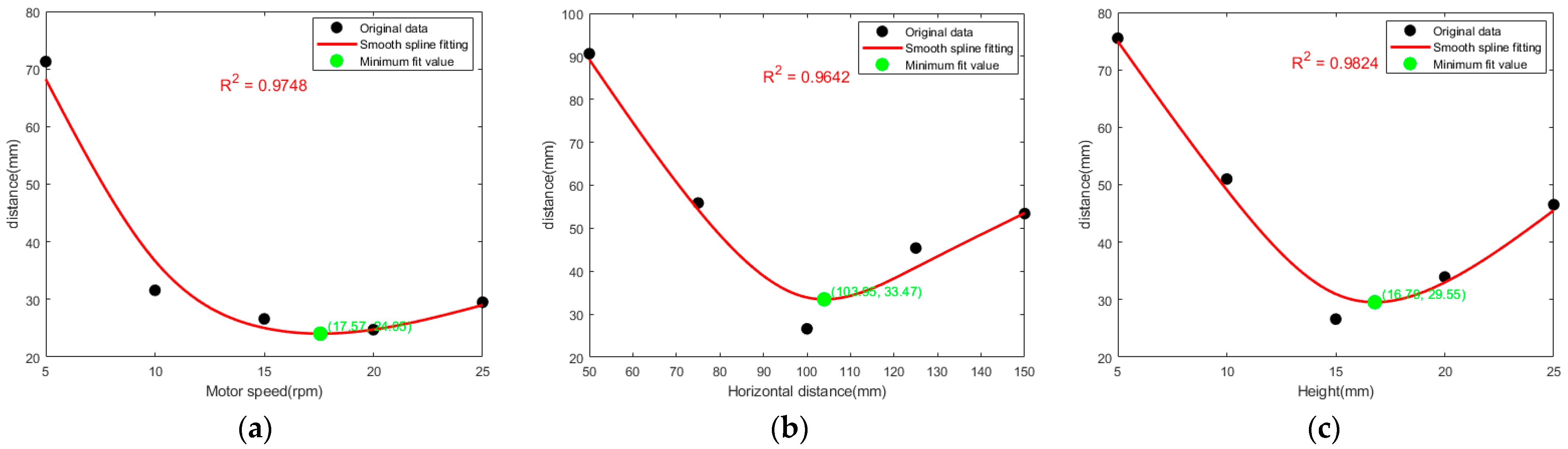

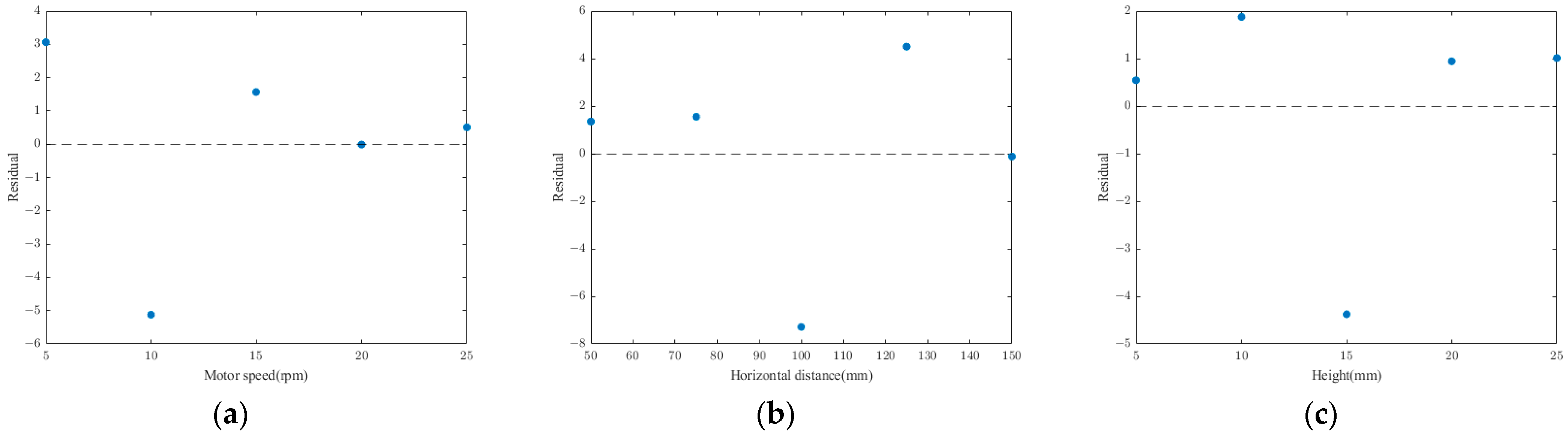

3.1.1. Motor Speed

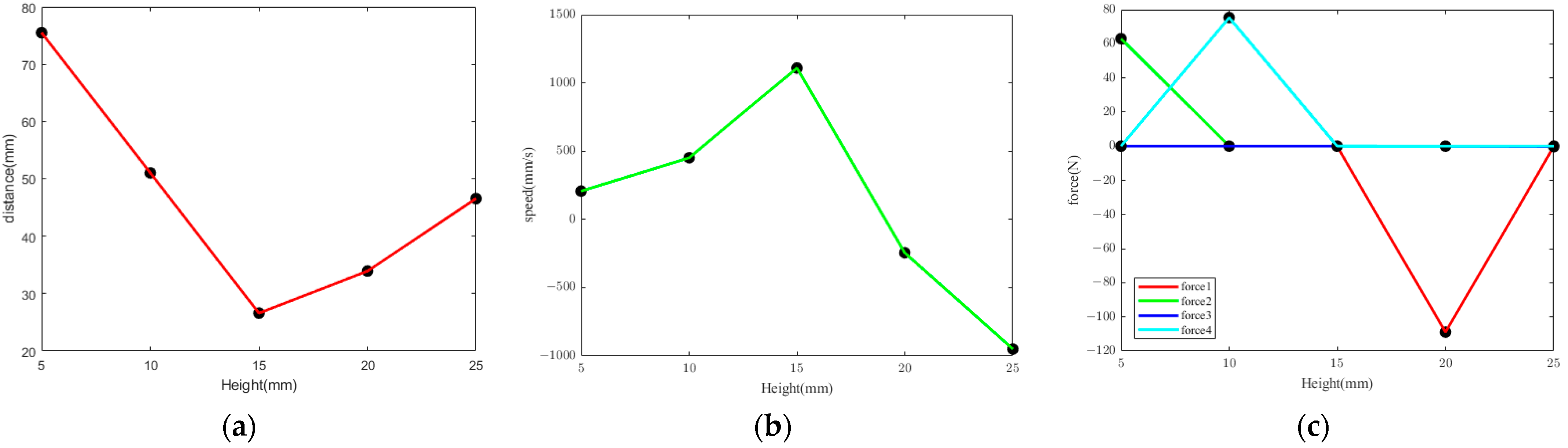

3.1.2. Stop Block Height

3.1.3. Horizontal Distance

3.1.4. Center-of-Mass Distance Curve Fitting

3.2. Bench Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on current cotton cultivation practices, an automated rod-feeding mechanism for small cotton arch sheds was proposed. This system enabled automatic separation of shed rods and orderly material feeding, effectively reducing labor costs and enhancing the efficiency of small cotton arch shed construction.

- (2)

- A kinematic analysis of the rod at the end of the synchronous belt revealed that the motor speed, synchronous belt stop block height, and horizontal distance were the primary influencing factors.

- (3)

- Kinematic simulation of the rod movement during the conveying process was conducted. The results indicated that motor speed, synchronous belt stop block height, and horizontal distance all exhibited similar trends in influencing the distance between the center of mass of the rod and the center of mass of the support frame. As the levels of these factors changed, the distance curve between the centers of mass first decreased and then increased. The optimal values were determined by fitting the centroid distance curve, where motor speed was 17.57 rpm, stop block height was 16.79 mm, and horizontal distance was 103.95 mm.

- (4)

- Bench tests were conducted in accordance with actual conditions. The results indicated that at a motor speed of 17 rpm, a stop block height of 15 mm, and a horizontal distance of 100 mm, the mechanism achieved missed rod and feeding rates of 19.2% and 80.8%, respectively. During the test, the automatic rod-feeding device operated smoothly without any abnormalities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.B.; Khan, A.; Zhu, D.S.; Zhang, Z.Y. Improving the productivity of Xinjiang cotton in heat-limited regions under two life history strategies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 363, 121374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.B.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, F.N.; Huang, W.X.; Wang, X.P.; Gao, Y. Irrigation modulates the effect of increasing temperatures under climate change on cotton production of drip irrigation under plastic film mulching in southern Xinjiang. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1069190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.F.; Zhu, A.L.; Liu, X.H.; Li, H.Y.; Tao, H.Y.; Guo, X.X.; Liu, J.F. Current status, challenges, and opportunities for sustainable crop production in Xinjiang. iScience 2025, 28, 112114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Liu, H.G.; Wang, T.G.; Gong, P.; Li, P.F.; Li, L.; Bai, Z.T. Deep vertical rotary tillage depths improved soil conditions and cotton yield for saline farmland in South Xinjiang. Eur. J. Agron. 2024, 156, 127166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, N.K.; Hao, C.C.; Liu, D.Z.; Maimaitiming, M.T.S.; Xiaokaitijiang, K.S.M.; Zhou, Y.P.; Li, Y.K. Modeling of cotton yield responses to different irrigation strategies in Southern Xinjiang Region, China. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 303, 109018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Z.Y.; Xu, Z.L.; Wang, Y. The spatio–temporal variation of spring frost in Xinjiang from 1971 to 2020. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimu, A.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Z.H. The response of biomass allocation in alfalfa and ryegrass to simulated spring frost. J. Plant Ecol. 2025, 18, rtaf073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, N.; Javed, T.; Pulatov, A.S.; Yang, Q.L. Cotton yield responses to climate change and adaptability of sowing date simulated by AquaCrop model. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 212, 118319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.Y.; Xie, Z.M.; Zhou, J.L.; Feng, H.J.; Zhang, T. Temperature impacts on cotton yield superposed by effects on plant growth and verticillium wilt infection in China. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2024, 68, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, W.Q.; Wu, B.J.; Wang, Y.X.; Xu, S.Z.; Chen, M.Z.; Liang, F.B.; Tian, J.S. Optimal row spacing configuration to improve cotton yield or quality is regulated by plant density and irrigation rate. Field Crop Res. 2024, 305, 109187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, M.H.; Wei, X.W.; Pan, Z.L.; Xu, Q.Q.; Qin, D.L.; Li, J.H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.Z.; Wang, K.F.; Duan, X.Y.; et al. Optimizing plant density and canopy structure to improve light use efficiency and cotton productivity: Two years of field evidence from two locations. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhou, B.; Zhang, Z.M.; Li, K.D.; Wang, J.Y.; Chen, J.F.; Papadakis, G. A critical review of the status of current greenhouse technology in China and development prospects. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Q.J.; Li, H.W.; Ji, C.C.; Peng, Y.; Li, T. Experimental study of ambient temperature and humidity distribution in large multi-span greenhouse based on different crop heights and ventilation conditions. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 248, 123176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemali, K. History of controlled environment horticulture: Greenhouses. HortScience 2022, 57, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.Q.; Chai, Z.P.; Bai, Y.G.; Zhang, J.H.; Liu, H.B.; Zheng, M.; Xiao, J. Effect of different mulching measures on cotton seedling stage in small arch shed. Water Sav. Irrig. 2023, 44–51+66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virk, G.; Snider, J.L.; Chee, P.; Jespersen, D.; Pilon, C.; Rains, G.; Roberts, P.; Kaur, N.; Ermanis, A.; Tishchenko, V. Extreme temperatures affect seedling growth and photosynthetic performance of advanced cotton genotypes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 172, 114025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.L. Green cultivation technology for deep winter market release of chives in small greenhouses. China Cucurbits Veg. 2019, 32, 98–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Hu, J.L.; Gong, Y.; Yu, Q.X.; Wang, Z.W.; Deng, X.Z.; Pang, X.G. Design and test of automatic feeding device for shed pole of small-arched insertion machine. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Wang, C.Y.; Qin, H.Z.; Hou, J.L. Design and test of automatic cottage device for arched shed. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Qin, H.Z.; Wang, Y.; Shao, R.R.; Wang, Y.H. Design and development of a low tunnel machine. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2021, 43, 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Wang, C.Y.; Qin, H.Z.; Hou, J.L.; Li, T.H. Design and experiment of single-row double cottage and film covering multi-functional machine for low tunnels. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.Z.; Liu, X.; Jin, S.T.; Li, L.F.; He, X.; Wang, T.; Mi, G.P.; Shi, Y.G.; Li, W. Design of and experiments with an automatic cuttage device for an arch shed pillar with force feedback. Agriculture 2022, 12, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.L.; Gong, Y.; Chen, X. Design and parameter optimization of rotary double-insertion device for small arched insertion machine. Agriculture 2024, 14, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.J.; Yao, K.H.; Zhong, C.Y.; Ma, S.M.; Deng, X.Z.; Aiwaili, S.D.K.J. Experimental study on performance of cotton small arch shed recovery machine. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Zhou, Y.Z.; Zhang, J.C.; Xu, Y.D.; Yao, J.T.; Zhao, Y.S. Kinematics and dynamics characteristics analysis of a double-ring truss deployable mechanism based on rectangular scissors unit. Eng. Struct. 2024, 307, 117900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbaś, A.; Augustynek, K.; Stadnicki, J. Dynamics analysis of a crane with consideration of a load geometry and a rope sling system. J. Sound Vib. 2024, 572, 118133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, K.; Hu, J.B.; Lou, J.J. Equilibrium analysis and simulation calculation of four-star type crank linkage mechanism. Machines 2023, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.C.; Liu, L.; Yan, J.; Wu, Z.J. Room-to-low temperature thermo-mechanical behavior and corresponding constitutive model of liquid oxygen compatible epoxy composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2024, 245, 110357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.M.; Wang, L.Q.; Tong, J.Z.; Tong, G.S.; Gao, W. Elastic buckling formulas of multi-stiffened corrugated steel plate shear walls. Eng. Struct. 2024, 300, 117218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.P.; Pan, J.; Zhang, C.D.; Zhang, S.W.; Fei, W.Z.; Pan, H.R. Optimization design and experiment on planetary gears planting mechanism of self-propelled transplanting machine. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2018, 49, 78–86. [Google Scholar]

| Level | Motor Speed (rpm) | Stop Block Height (mm) | Horizontal Distance (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 5 | 50 |

| 2 | 10 | 10 | 75 |

| 3 | 15 | 15 | 100 |

| 4 | 20 | 20 | 125 |

| 5 | 25 | 25 | 150 |

| Parameters | Numeric Value or Type |

|---|---|

| Static friction coefficient | 0.3 |

| Dynamic friction coefficient | 0.1 |

| Time step | 0.01 s |

| Rod material | Glass fiber plastic |

| Synchronous belt pulley tooth count | 32 |

| Stop block spacing | 24.26 mm |

| Contact stiffness 1 | 100 |

| Contact stiffness 2 | 1000 |

| Damping | 1.0 |

| Connected Parts | Connected Parts | Constraint Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Synchronous belt pulley | Ground | Rotary assembly |

| Rack | Ground | Joint |

| Limit plate | Rack | Joint |

| Stop block | Synchronous belt | Joint |

| Number of Tests | Number of Rods | Number of Rods Without Rods Inserted | Number of Rod Insertions | Missed Rod Rate (%) | Feeding Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | 6 | 44 | 12 | 88 |

| 2 | 50 | 6 | 44 | 12 | 88 |

| 3 | 50 | 11 | 39 | 22 | 78 |

| 4 | 50 | 11 | 39 | 22 | 78 |

| 5 | 50 | 14 | 36 | 28 | 72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yuan, P.; Wen, P.; You, J.; Aiwaili, S.; Zhu, X.; Peng, H.; Wang, Z. Design and Evaluation of an Automated Rod-Feeding Mechanism for Small Arch Shed Machine Based on Kinematics. Agriculture 2026, 16, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010030

Yuan P, Wen P, You J, Aiwaili S, Zhu X, Peng H, Wang Z. Design and Evaluation of an Automated Rod-Feeding Mechanism for Small Arch Shed Machine Based on Kinematics. Agriculture. 2026; 16(1):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010030

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Panpan, Pengfei Wen, Jia You, Sidikejiang Aiwaili, Xingliang Zhu, Huiqing Peng, and Zhikun Wang. 2026. "Design and Evaluation of an Automated Rod-Feeding Mechanism for Small Arch Shed Machine Based on Kinematics" Agriculture 16, no. 1: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010030

APA StyleYuan, P., Wen, P., You, J., Aiwaili, S., Zhu, X., Peng, H., & Wang, Z. (2026). Design and Evaluation of an Automated Rod-Feeding Mechanism for Small Arch Shed Machine Based on Kinematics. Agriculture, 16(1), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture16010030