The Effects of Sand-Fixing Agents and Trichoderma longibrachiatum on Soil Quality and Alfalfa Growth in Wind-Sand Soil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Material

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Measurement Items and Methods

2.3.1. Determination of Crust Hardness of Sand Fixer

2.3.2. Determination of Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

2.3.3. Determination of Alfalfa Indicators

2.3.4. Soil Microbial Sequencing

2.3.5. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

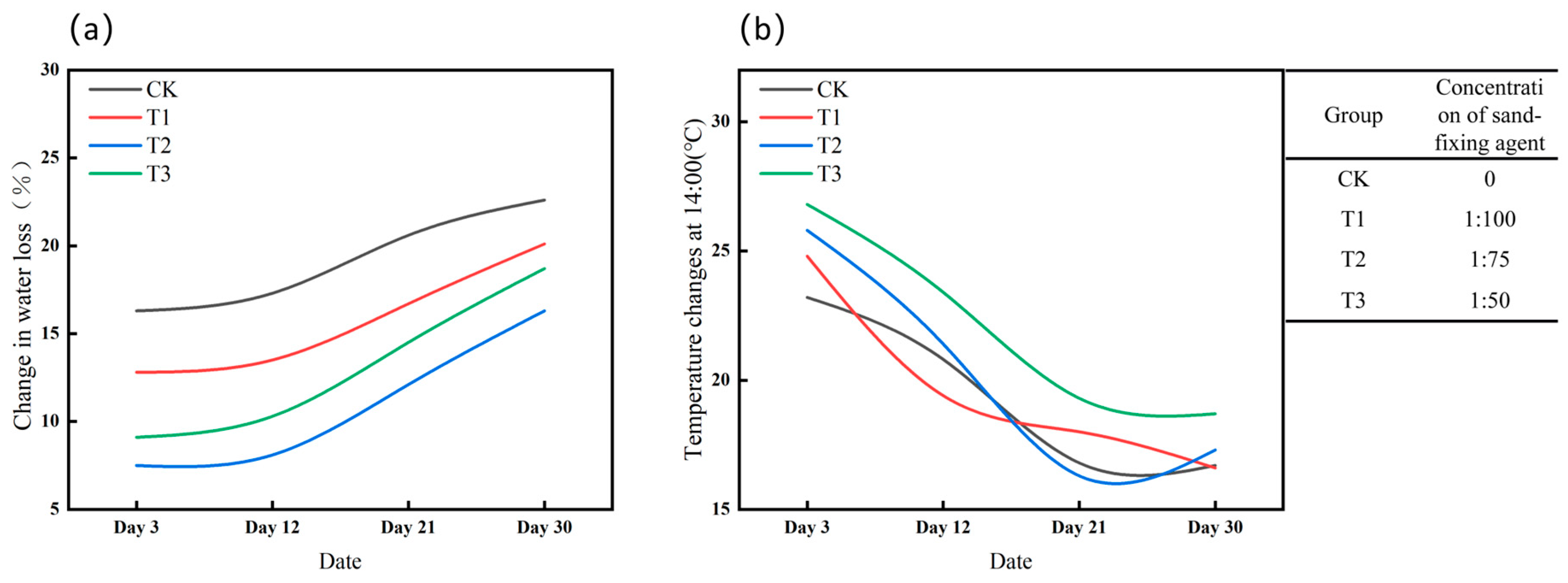

3.1. Effect of Sand-Fixing Agent Application on Soil Temperature and Humidity

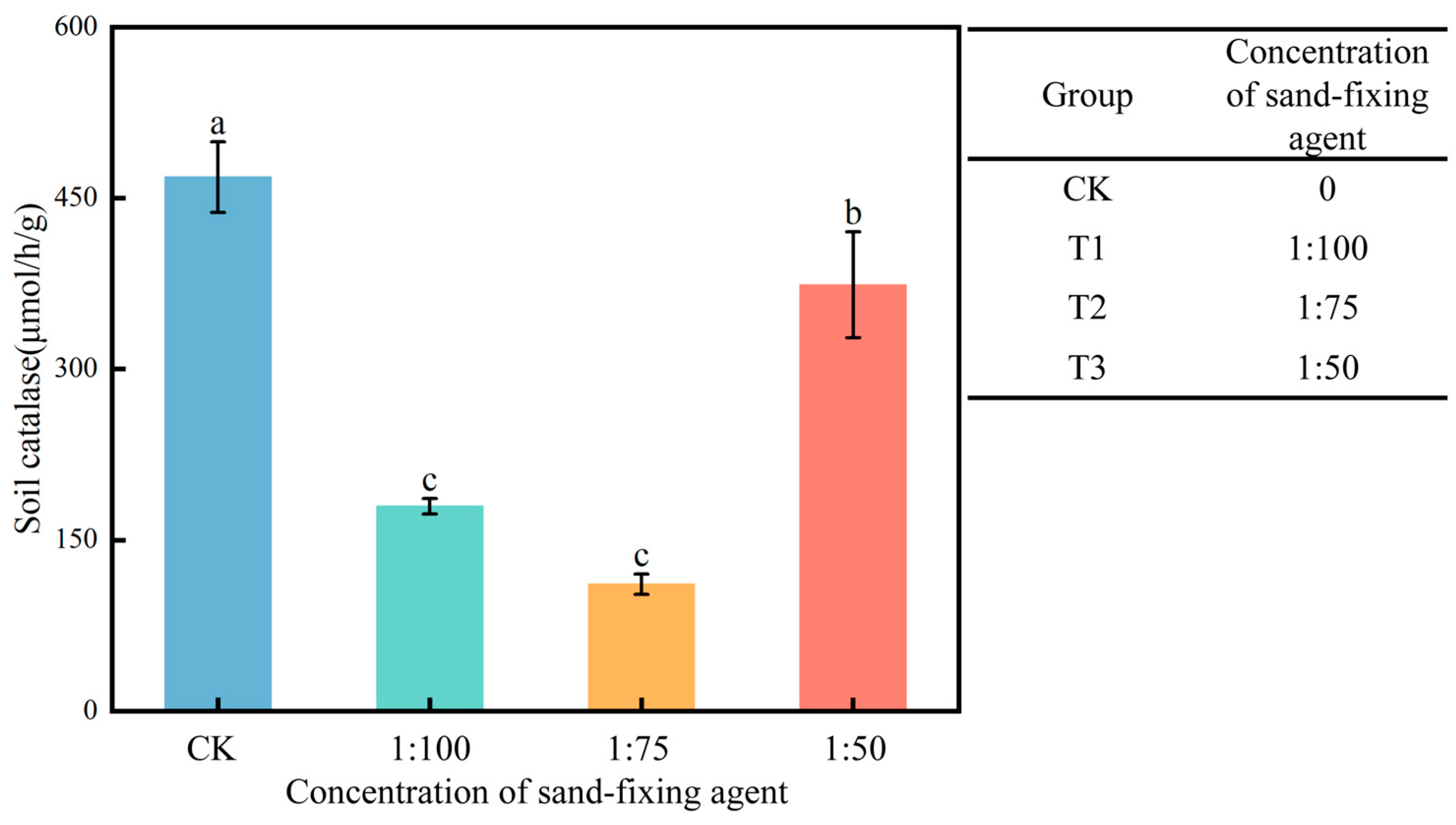

3.2. Soil Catalase

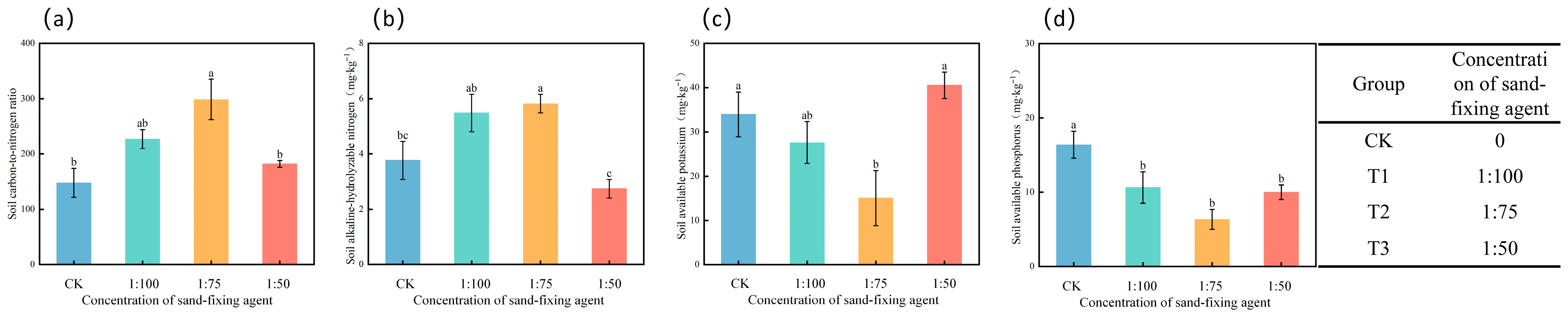

3.3. Soil Carbon-to-Nitrogen Ratio, Available Nitrogen, Available Phosphorus, and Available Potassium

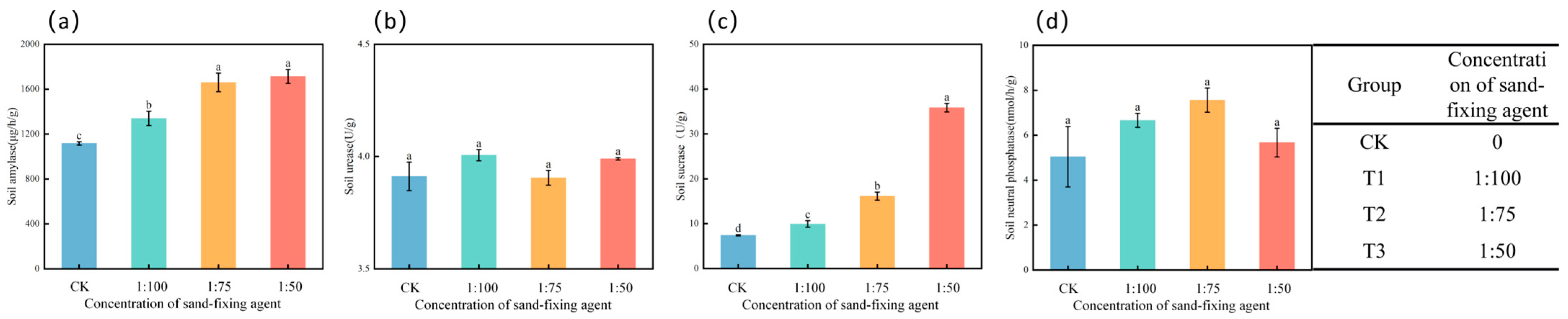

3.4. Effects of Different Treatments on Soil Enzymes

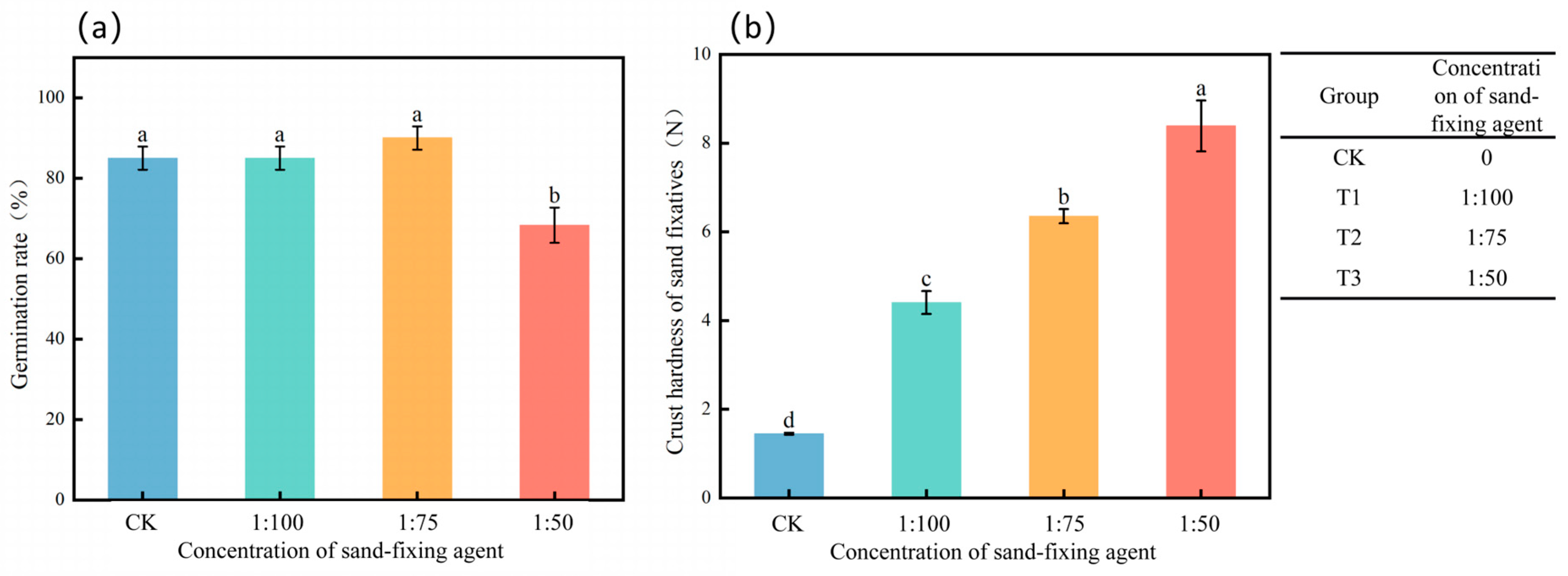

3.5. Effects of Different Treatments on the Germination Rate of Alfalfa

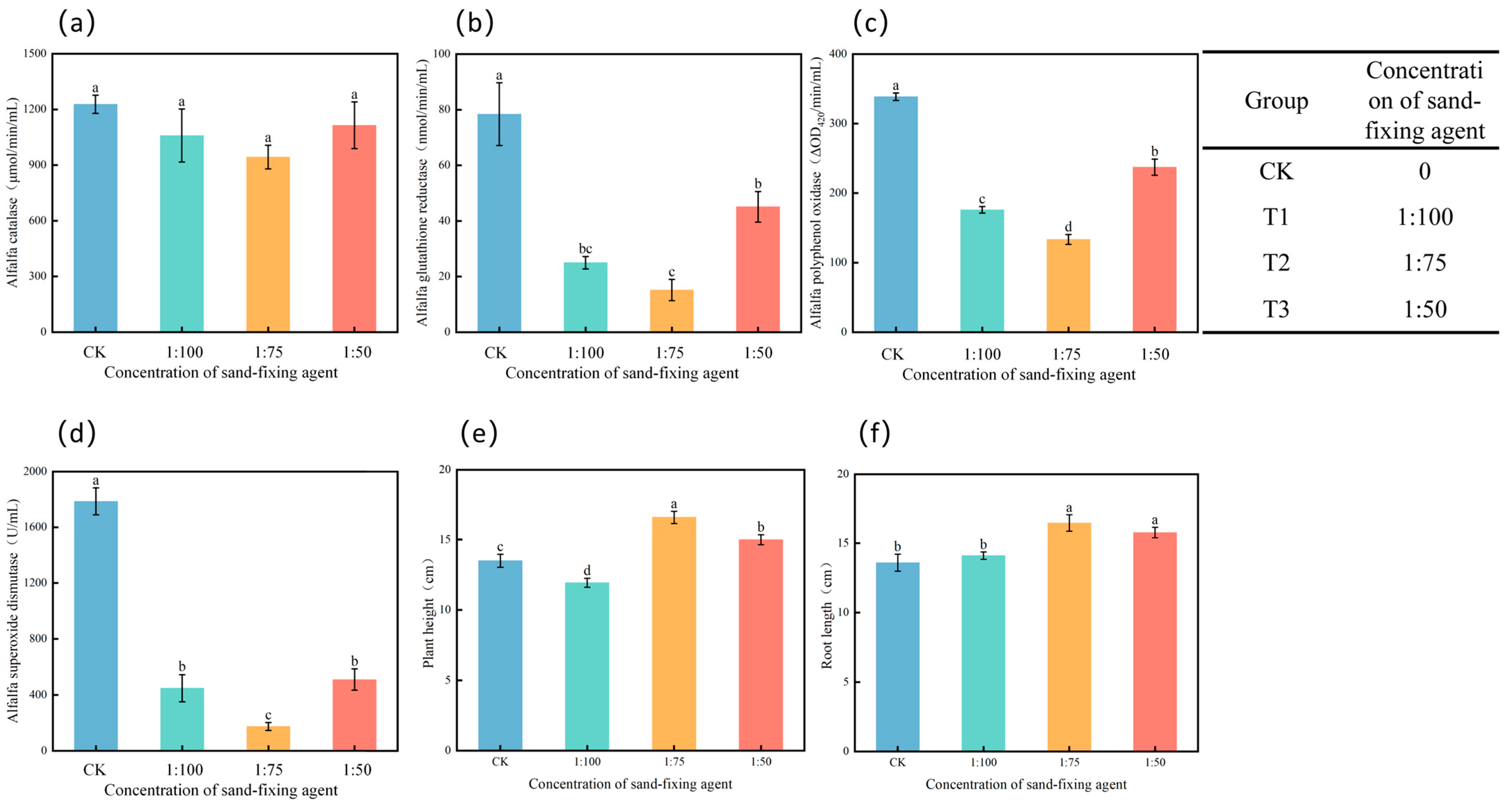

3.6. Effects of Different Treatments on Enzyme Activities and Growth Status in Alfalfa

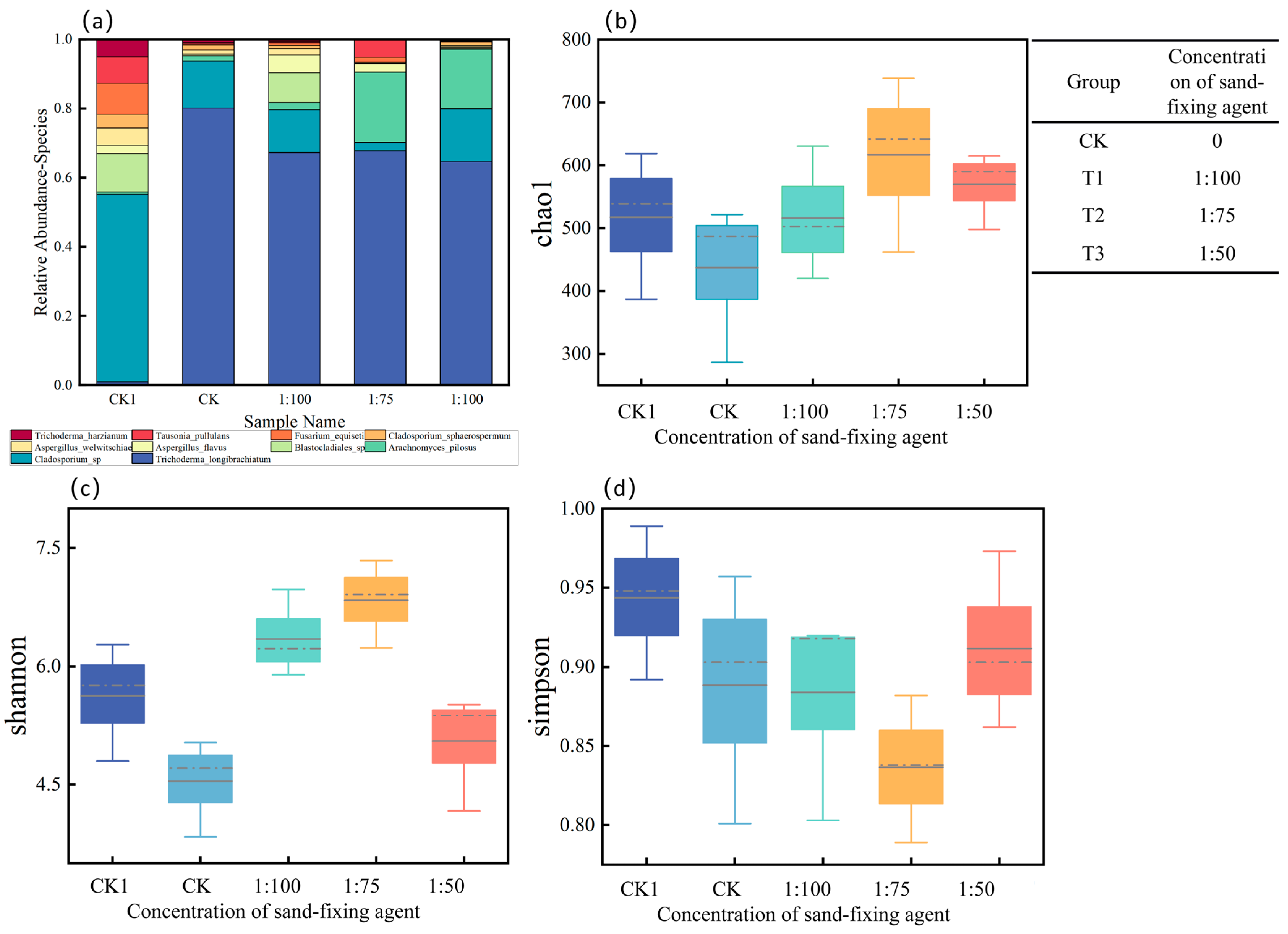

3.7. Soil Microorganisms

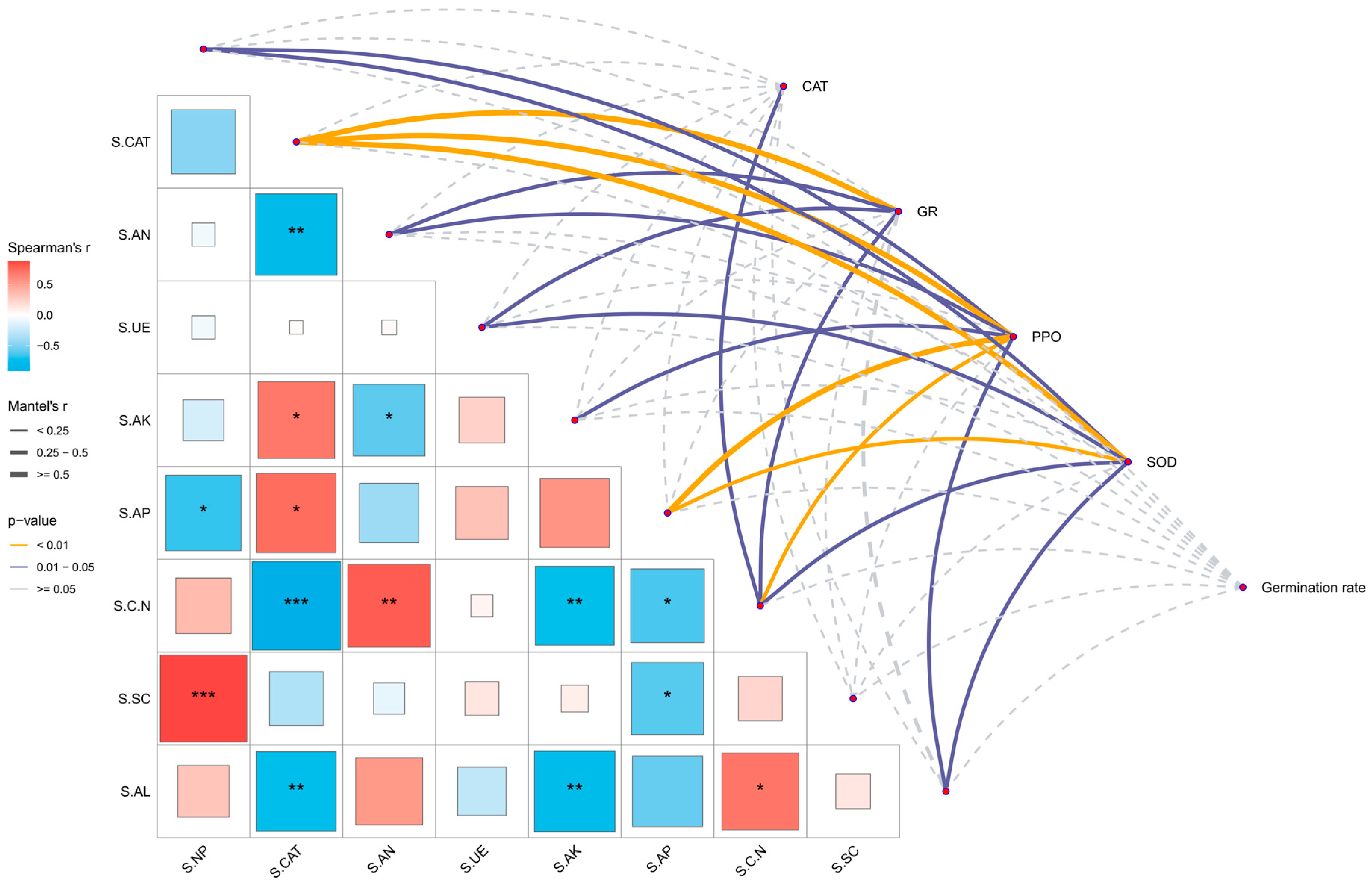

3.8. Correlation Analysis Between Stress-Resistant Protective Enzymes, Germination Rate of Alfalfa, and Soil Factors

3.9. Scoring Based on Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Dynamic Effect of Sand-Fixing Agent on Water and Heat Preservation

4.2. Effects of Sand-Fixing Agents on the Germination Rate of Alfalfa

4.3. Comprehensive Regulation of Sand-Fixing Agents on Soil Physical and Chemical Properties, Enzyme Activities, and Stress-Resistant Enzyme Activities of Alfalfa

4.4. Guiding Significance of Comprehensive Scores Based on Principal Component Analysis for Practical Applications

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The concentration of the sand-fixing agent critically influences water and heat retention. At a low concentration (1:100), the crust is thin and decomposes easily, initially providing some heat and water retention, but this effect diminishes over time. The medium concentration (1:75) offers optimal water retention by balancing evaporation suppression and water infiltration. Conversely, the high concentration (1:50) forms a dense crust that impedes water infiltration, while elevated surface temperatures increase evaporation, leading to poor water retention. The physical consolidation effect of the sand-fixing agent is temporary, hindering long-term stable microenvironment regulation.

- (2)

- The synergistic application of a sand-fixing agent and T. longibrachiatum improves soil physical and chemical properties and enzyme activities. A medium concentration of the sand-fixing agent, combined with Trichoderma, optimally regulates the soil carbon–nitrogen ratio and nutrient dynamics. Soil catalase activity indicates environmental stress levels: high activity under high-concentration treatment suggests strong stress, while medium-concentration treatment results in lower enzyme activity, indicating a more favorable environment. Low-concentration treatment shows intermediate enzyme activity.

- (3)

- The introduction of T. longibrachiatum markedly improved alfalfa’s stress resistance. The sand-fixing agent and Trichoderma exhibited complementary functions over time: initially, the sand-fixing agent retained water, facilitating Trichoderma colonization; subsequently, Trichoderma improved soil quality through metabolic activity, bolstering crop stress resistance.

- (4)

- Principal component analysis revealed that the combined application of a medium-concentration sand-fixing agent (1:75) and T. longibrachiatum exhibited superior performance in enhancing soil nutrients, enzyme activities, and crop stress resistance. This synergy of physical consolidation and biological regulation continuously optimized the sandy land microenvironment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jaeger, A.C.H.; Hartmann, M.; Six, J.; Solly, E.F. Contrasting sensitivity of soil bacterial and fungal community composition to one year of water limitation in Scots pine mesocosms. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2023, 99, fiad051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Q.; Qi, J.; Xin, X.; Xu, D.; Yan, R. Enhanced wind erosion control by alfalfa grassland compared to conventional crops in Northern China. Agronomy 2025, 15, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Sun, W. Natural recovery dynamics of alfalfa field soils under different degrees of mechanical compaction. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Bai, Y.; Song, Z.; Lu, Y.; Qian, W.; Kanungo, D.P. Evaluation of strength properties of sand modified with organic polymers. Polymers 2018, 10, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashan, Y.; Salazar, B.G.; Moreno, M.; Lopez, B.R.; Linderman, R.G. Restoration of eroded soil in the Sonoran Desert with native leguminous trees using plant growth-promoting microorganisms and limited amounts of compost and water. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 102, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Xu, F.; Yang, J. A novel approach to cost-effective utilization of flax polysaccharides: Sand fixation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 322 Pt 3, 146925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versino, F.; Urriza, M.; García, M.A. Eco-compatible cassava starch films for fertilizer controlled-release. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 134, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepasree, S.; Sasikumar, R.; Dilip, A.A.; Eldhose, A.; Radhika, N.; Sreekumar, K.; Senthilkumar, G. Valorization of waste foundry sand by squeezing with sustainable cardanol-starch modified binder for engineered stone. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Askar, A.A.; Rashad, E.M.; Moussa, Z.; El-Sayed, E.R.; Hamed, A.A.; Aboshosha, S.S.; Abdel-Rahim, I.R. A novel endophytic Trichoderma longibrachiatum WKA55 with biologically active metabolites for promoting germination and reducing mycotoxinogenic fungi of peanut. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 772417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halifu, S.; Deng, X.; Song, X.; Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Effects of two Trichoderma strains on plant growth, rhizosphere soil nutrients, and fungal community of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica annual seedlings. Forests 2019, 10, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inner Mongolia Forestry; Grassland Bureau. Microorganism–Soil–Crust–Plant Synergy Won Top Science-Technology Award. Available online: https://lcj.nmg.gov.cn/lckj/202309/t20230921_2383056.html (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Aili, R.; Deng, Y.; Yang, R.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Jia, S.; Yu, L.; Zhang, T. Molecular mechanisms of alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.) in response to combined drought and cold stresses. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y. Preliminary multi-objective optimization of mobile drip irrigation system design and deficit irrigation schedule: A full growth cycle simulation for alfalfa using HYDRUS-2D. Water 2025, 17, 966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Liu, L.; Gao, J.; Wu, S.; Liu, Y. Evaluation of the effectiveness of irrigation methods and fertilization strategies for alfalfa: A meta-analysis. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 2023, 209, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Q.; An, C.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; et al. Polydopamine-coated montmorillonite micro/nanoparticles enhanced pectin-based sprayable multifunctional liquid mulching films: Wind erosion resistance, water retention, and temperature increase/heat preservation properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 298, 139976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, C.; Gou, M.; Lei, L.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, N.; Zhu, S.; Hu, R.; Xiao, W. Contrasting change patterns of lignin and microbial necromass carbon and the determinants in a chronosequence of subtropical Pinus massoniana plantations. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 198, 105385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. J. Agric. Sci. 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil Agrochemical Analysis, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2000; Available online: https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=2539225 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Guan, S.Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, Z. Soil Enzymes and Their Research Methods; Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1986; p. 376. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J. Comprehensive evaluation of agricultural economic development level in Sichuan Province based on principal component analysis, China. Anhui Agric. Sci. Bull. 2018, 24, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-S.; Park, J.-W.; Yoon, K.-B.; Park, I.S.; Woo, S.-W.; Lee, D.-E. Evaluation of compressive strength and thermal conductivity of sand stabilized with epoxy emulsion and polymer solution. Polymers 2022, 14, 1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Gao, W.; Wu, Z.; Iwashita, K.; Yang, C. Synthesis and characterization of a novel chemical sand-fixing material of hydrophilic polyurethane. J. Soc. Mater. Sci. 2011, 60, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Qin, S.G.; Li, Y.L.; Yang, R. Sand fixation experiment of Artemisia sphaerocephala Krasch. gum with different concentrations. J. Arid Land 2016, 8, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, L.; Ren, T.; Emily, D. Effects of three plant-based sand-fixing agents on water infiltration and evaporation in aeolian sandy soil. Arid Zone Res. 2025, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Shi, W.J.; Wang, Y. Poly-γ-glutamic acid application rate effects on hydraulic properties of sandy soil under wetting–drying cycles. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2022, 86, 904–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zhang, B.; Dai, M.; Li, Y.; Fang, X. Improvement of grain weight and crop water productivity in winter wheat by light and frequent irrigation based on crop evapotranspiration. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 301, 108922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Du, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, J. Effects of several polymeric materials on the improvement of the sandy soil under rainfall simulation. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquah, K.; Chen, Y. Measurements and predictions of seedling emergence forces. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 247, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sheng, M. Responses of soil C, N, and P stoichiometrical characteristics, enzyme activities and microbes to land use changes in Southwest China Karst. Forests 2023, 14, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, C. Soil eco-enzymatic stoichiometry reveals microbial phosphorus limitation after vegetation restoration on the Loess Plateau, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galba, J.B.; Henrique, L.F.; Freitas, A.J.C.; Silva, I.R.; de Oliveira Mendes, I. Trichoderma strains accelerate maturation and increase available phosphorus during vermicomposting enriched with rock phosphate. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 130, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, B.; Khademian, R.; Sedaghati, B. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) confer drought resistance and stimulate biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium L.) under water shortage condition. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 263, 109132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogati, K.A.; Sewerniak, P.; Walczak, M. Unraveling the effect of soil moisture on microbial diversity and enzymatic activity in agricultural soils. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockett, B.F.T.; Prescott, C.E.; Grayston, S.J. Soil moisture is the major factor influencing microbial community structure and enzyme activities across seven biogeoclimatic zones in western Canada. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 44, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Concentration of Sand-Fixing Agent | Whether to Add Trichoderma longiflorum | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| CK | 0 | Yes | |

| T1 | 1:100 | Yes | |

| T2 | 1:75 | Yes | |

| T3 | 1:50 | Yes | |

| CK1 | 0 | No | For microbial sequencing only |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Li, X.; Shan, X.; Dong, Z.; An, C. The Effects of Sand-Fixing Agents and Trichoderma longibrachiatum on Soil Quality and Alfalfa Growth in Wind-Sand Soil. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232463

Chen X, Li X, Shan X, Dong Z, An C. The Effects of Sand-Fixing Agents and Trichoderma longibrachiatum on Soil Quality and Alfalfa Growth in Wind-Sand Soil. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232463

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xiaolong, Xu Li, Xiaofeng Shan, Zhi Dong, and Chunchun An. 2025. "The Effects of Sand-Fixing Agents and Trichoderma longibrachiatum on Soil Quality and Alfalfa Growth in Wind-Sand Soil" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232463

APA StyleChen, X., Li, X., Shan, X., Dong, Z., & An, C. (2025). The Effects of Sand-Fixing Agents and Trichoderma longibrachiatum on Soil Quality and Alfalfa Growth in Wind-Sand Soil. Agriculture, 15(23), 2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232463