Estimation of Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land Based on Improved CASA-CGC Model—A Case Study of Anhui Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection and Processing

2.3. Methods

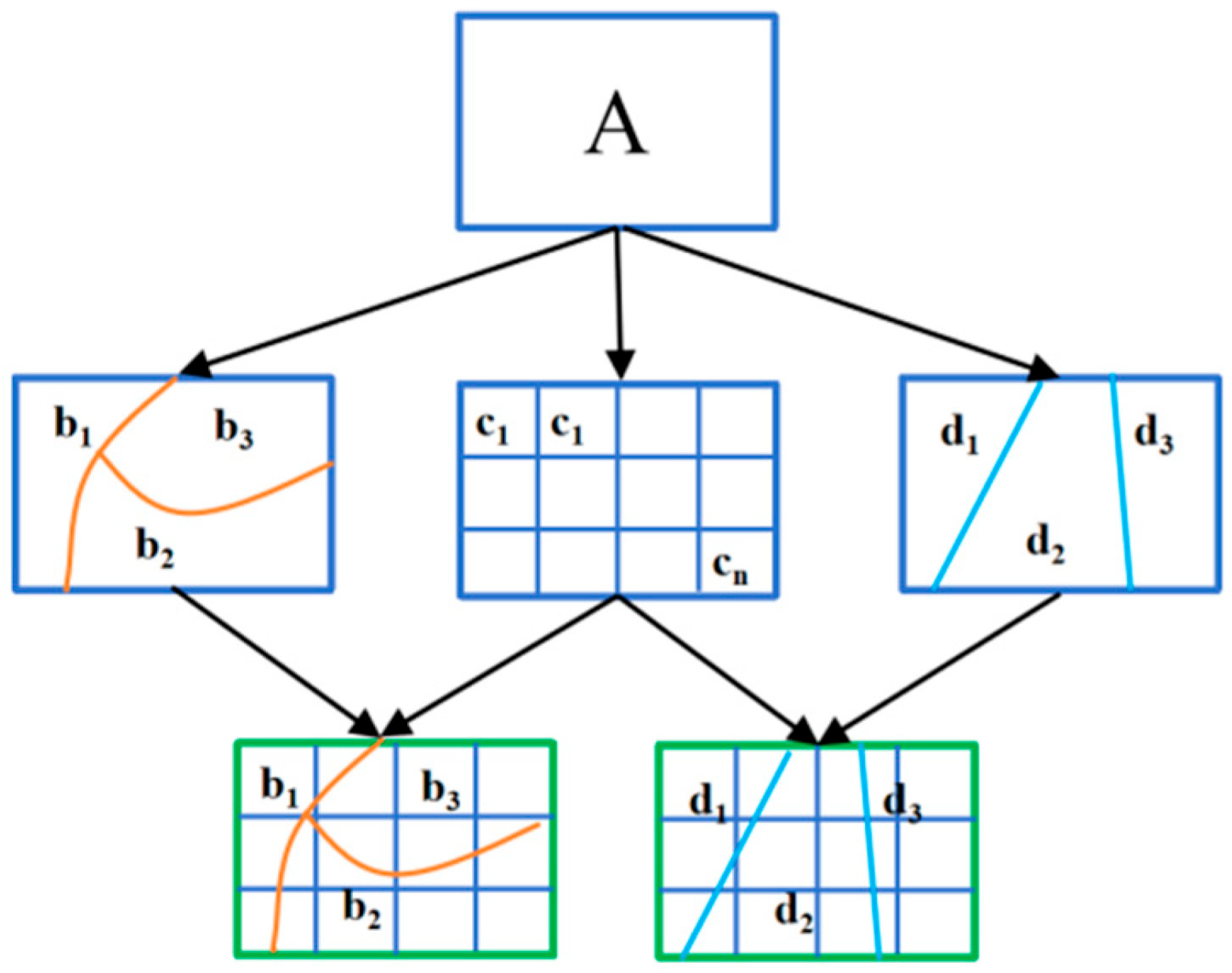

2.3.1. Theoretical Basis for Model Improvement

2.3.2. Calculation of Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land

Net Ecosystem Productivity (NEP) Estimation Model

- (1)

- Photosynthetically active radiation absorbed by vegetation ()

- (2)

- Light energy utilization rate ()

Rh Estimation Model

Determine the Growth Period of Different Crops

Accuracy Comparison of Estimation Models

2.3.3. One-Way ANOVA Method

2.3.4. Random Forest Model

2.3.5. Geographical Detector

3. Results

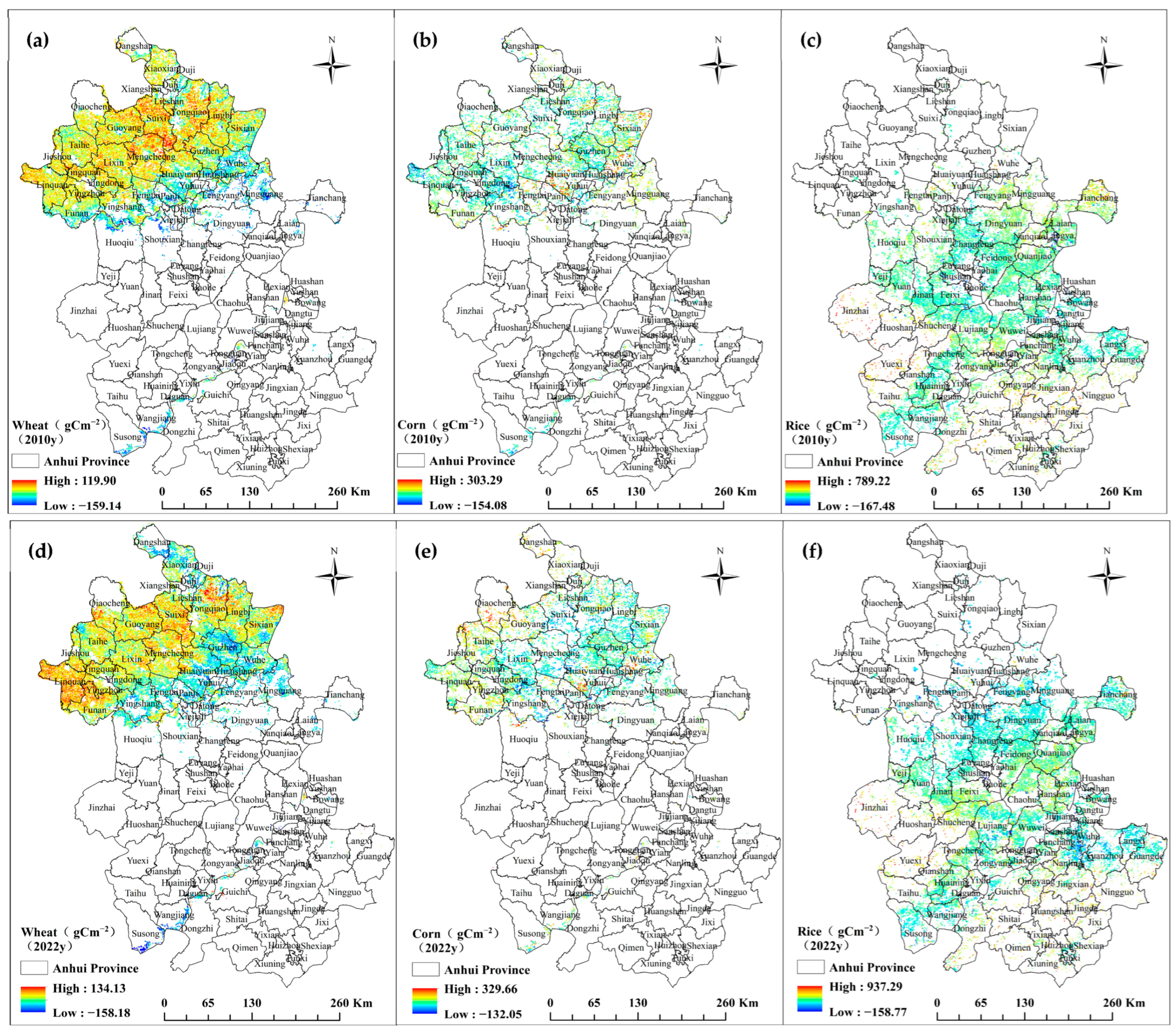

3.1. Calculation Results of Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land During Different Crop Growth Cycles

3.1.1. Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Different Crops from 2010 to 2022

3.1.2. The Variation in Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Different Crops from 2010 to 2022

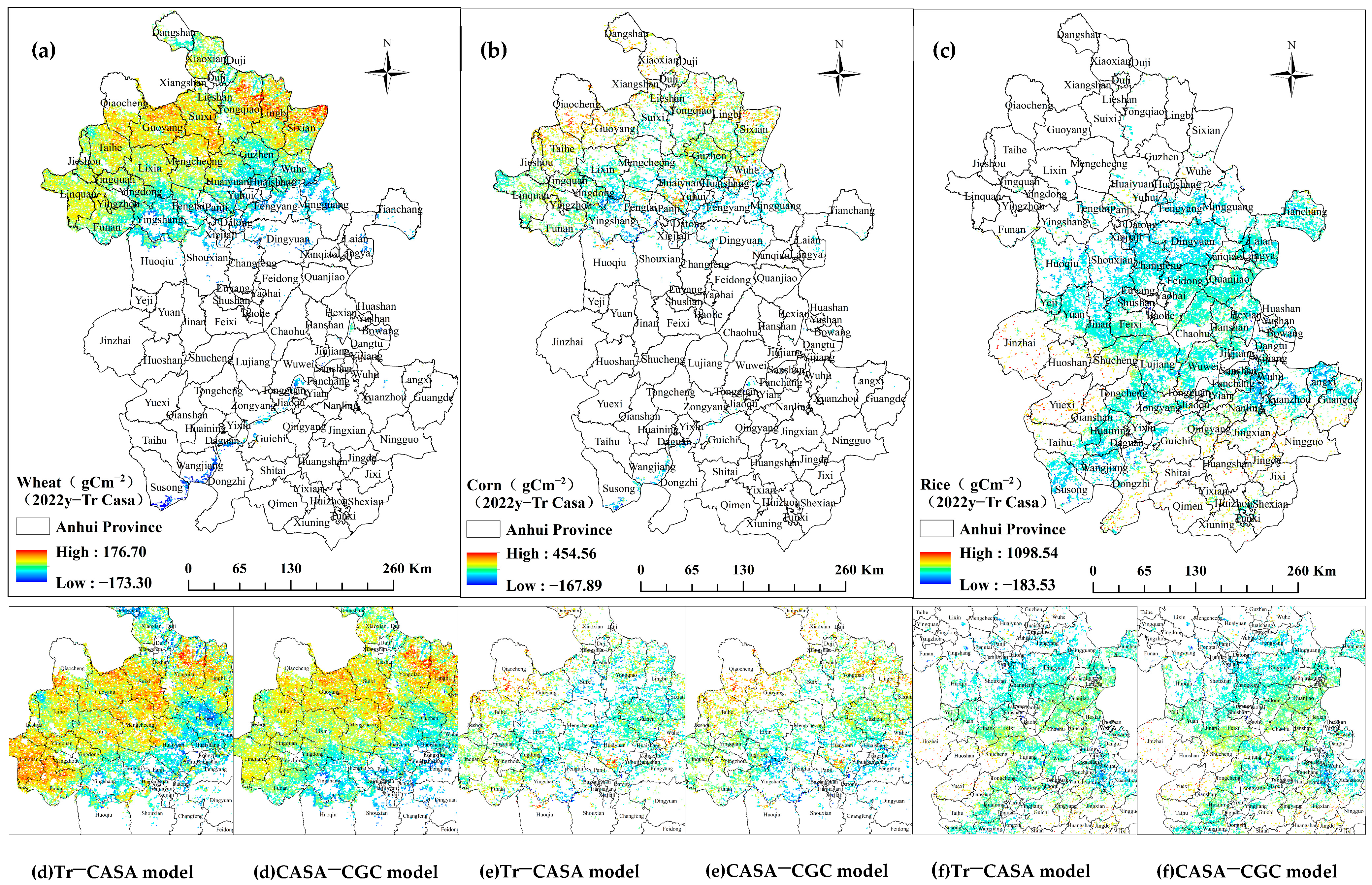

3.1.3. Comparison of Carbon Sequestration Results Between Tr-CASA Model and CASA-CGC Model for Different Crops

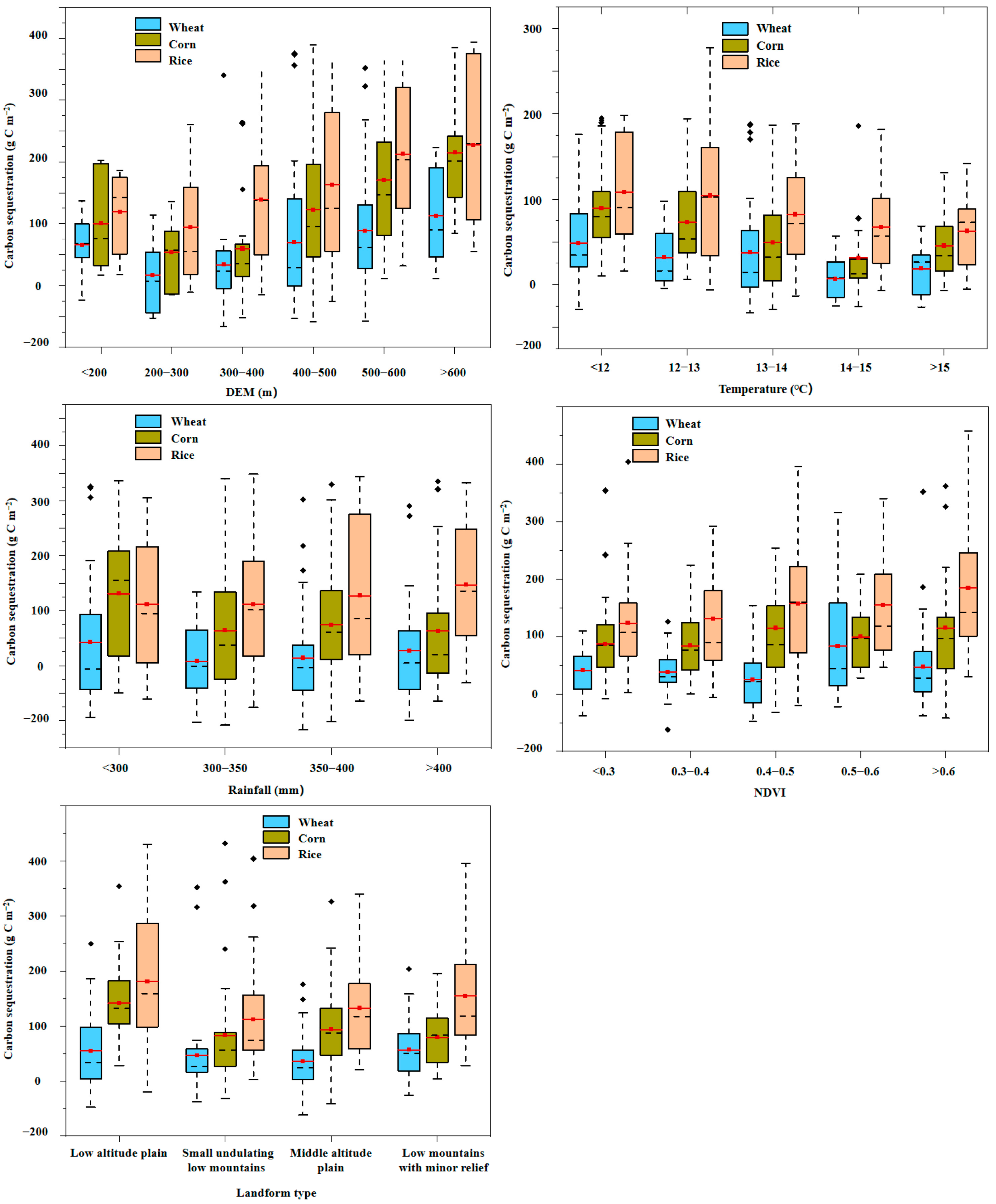

3.2. Analysis of the Impact of Single Factors on Crop Carbon Sequestration Capacity

3.2.1. Analysis of the Impact of Natural Environmental Factors on Crop Carbon Sequestration Capacity

3.2.2. Analysis of the Impact of Human Social Factors on Crop Carbon Sequestration Capacity

3.3. Interaction Effects of Influencing Factors on Crop Carbon Sequestration Capacity

3.3.1. Ranking of Impact Factor Importance

3.3.2. The Interaction Effect Between Influencing Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Accuracy of the Carbon Sequestration Capacity Accounting Model for Cultivated Land

4.2. Factors Affecting the Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land

4.2.1. The Impact of Various Regional Influencing Factors on the Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land

4.2.2. The Impact of Interactions Among Regional Influencing Factors on the Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land

4.3. Implications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, D.; Hussain, A.; Begum, F.; Lin, C.; Ali, S.; Ahsan, W.A.; Hussain, A.; Hussain, F. Assessing the impact of land use and land cover changes on soil properties and carbon sequestration in the upper Himalayan Region of Gilgit, Pakistan. Sustain. Chem. One World 2025, 5, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Shen, X.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y. Spatiotemporal characteristics and socio-ecological drivers of ecosystem service interactions in the Dongting Lake Ecological Economic Zone. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council. No. 1 Central Document; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2025.

- Cao, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Yang, J.; Song, Y. Land use spatial optimization for city clusters under changing climate and socioeconomic conditions: A perspective on the land-water-energy-carbon nexus. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 349, 119528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, C.; Guo, E.; Liu, Z.; Harrison, M.T.; Liu, K.; Zhang, T.; Yang, X. Adapting crop land-use in line with a changing climate improves productivity, prosperity and reduces greenhouse gas emissions. Agric. Syst. 2024, 217, 103905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parton, W.J.; Schimel, D.S.; Cole, C.V.; Ojima, D.S. Analysis of Factors Controlling Soil Organic Matter Levels in Great Plains Grasslands. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1987, 51, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, K.; Jenkinson, D.S. RothC-26.3—A Model for the turnover of carbon in soil. In Evaluation of Soil Organic Matter Models: Using Existing Long-Term Datasets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- West, T.O.; Post, W.M. Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration Rates by Tillage and Crop Rotation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 1930–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R.J.S. Soil Carbon Sequestration Impacts on Global Climate Change and Food Security. Science 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.; Martino, D.; Cai, Z.; Gwary, D.; Smith, J. Greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 789–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paustian, K.; Lehmann, J.; Ogle, S.; Reay, D.; Robertson, G.P.; Smith, P.J.N. Climate-smart soils. Nature 2016, 532, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Y. Impacts of cultivated land protection practices on farmers’ welfare: A dual quality and ecology perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 110, 107690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roba, Z.R.; Moisa, M.B.; Aymeku, T.G.; Daba, D.E.; Gemeda, D.O. Spatial analysis of land use and cover changes: Implications of green legacy initiative on climate action in Upper Awash Basin, Ethiopia. Trees For. People 2025, 20, 100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Qu, Z.; Li, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Huang, G.J.S.; Research, T. Contrasting effects of different straw return modes on net ecosystem carbon budget and carbon footprint in saline-alkali arid farmland. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 239, 106031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhen-Ming, G.E.; KELLOMÄKI, S.; Wang, K.Y.; Peltola, H.; Martikainen, P.J.G.B. Effects of elevated CO2 and temperature on leaf characteristics, photosynthesis and carbon storage in aboveground biomass of a boreal bioenergy crop (Phalaris arundinacea L.) under varying water regimes. GCB Bioenergy 2010, 3, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd-Brown, K.E.O.; Randerson, J.T.; Hopkins, F.; Arora, V.; Hajima, T.; Jones, C.; Shevliakova, E.; Tjiputra, J.; Volodin, E.; Wu, T.J.B. Changes in soil organic carbon storage predicted by Earth system models during the 21st century. Biogeosciences Discuss. 2014, 10, 18969–19004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayle, F.E.; Beerling, D.J.; Gosling, W.D.; Bush, M.B. Responses of Amazonian ecosystems to climatic and atmospheric carbon dioxide changes since the last glacial maximum. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2004, 359, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, W.J.A.E. Projected changes in soil organic carbon stocks of China’s croplands under different agricultural managements, 2011–2050. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 178, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haughey, E.; Neogi, S.; Portugal-Pereira, J.; Diemen, R.V.; Slade, R.B. Sustainable intensification and carbon sequestration research in agricultural systems: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Policy 2023, 143, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jien, S.-H.; Minasny, B.; Yang, B.-J.; Liu, Y.-T.; Yen, C.-C.; Ocba, M.A.; Zhang, Y.-T.; Syu, C.-H. Enhancing Soil Carbon Storage: Developing high-resolution maps of topsoil organic carbon sequestration potential in Taiwan. Geoderma 2025, 459, 117369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Adhikari, K.; He, N. Soil carbon sequestration potential of cultivated lands and its controlling factors in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; Xie, E.; Zhang, R.; Gao, B.; Li, L.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liao, Y.; Lei, M.; Kong, X. Spatial variations of organic matter concentration in cultivated land topsoil in North China based on updated soil databases. Soil Tillage Res. 2025, 248, 106445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; Yang, C.; Suo, X.; Zhang, Q. Climate extremes and land use carbon emissions: Insight from the perspective of sustainable land use in the eastern coast of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Ke, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Tao, R.; Wang, Y. Derived regional soil-environmental quality criteria of metals based on Anhui soil-crop systems at the regulated level. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 154060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Hu, R.; Cheng, T.; Zhou, Y.; Tu, D.; Ji, Y.; Xu, X.; Sun, X.; et al. Progress and challenges of rice ratooning technology in Anhui Province, China. Crop Environ. 2023, 2, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wan, Y.; Cao, W.; Yan, L.I.; Yao, L.I.; Zhang, P. Analysis and Evaluation of Grain Quality in Main Wheat Production Areas of Anhui Province. Asian Agric. Res. 2018, 10, 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Huang, S.; Liang, B. Spatiotemporal variation and prediction of NPP in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region by coupling PLUS and CASA models. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Qin, P.; Yue, W.; Guo, Y.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Yan, Z. High temporal and spatial estimation of grass yield by applying an improved Carnegie-Ames-Stanford approach (CASA)-NPP transformation method: A case study of Zhenglan Banner, Inner Mongolia, China. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 224, 109134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, R.; Guo, J.; Xu, H.; Miao, Y.; Niu, F.; Gao, Z.; Yang, X.; Xiong, F.; Zhang, J. Analysis of the spatiotemporal dynamics of grassland carbon sinks in Xinjiang via the improved CASA model. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Pan, Y.; He, H.; Yu, D.; Hu, H. Simulation of maximum light use efficiency for some typical vegetation types in China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2006, 51, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guan, Q.; Zhao, B.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, X.; Luo, H. Multi-objective optimal allocation of agricultural water and land resources in the Heihe River Basin: Coupling of climate and land use change. J. Hydrol. 2025, 653, 132783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yun, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, H. Northeastern China shelterbelt-farmland glomalin differences depend on geo-climates, soil depth, and microbial interaction: Carbon sequestration, nutrient retention and implication. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2023, 191, 105068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, N.; Peng, K.; Yan, X.; Lu, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, C.; Zhao, B. Towards interpreting machine learning models for understanding the relationship between vegetation growth and climate factors: A case study of the Anhui Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Gao, J.; Wang, Q.; Ning, Z.; Tan, X.; Lei, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zou, J.; Wang, L.; Yang, C.; et al. Light energy utilization and measurement methods in crop production. Crop Environ. 2024, 3, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.-H.; Yang, S.-S.; Wang, J.-W.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, S. Modelling the crop yield gap with a remote sensing-based process model: A case study of winter wheat in the North China Plain. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 2993–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Du, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, K.; Peng, X.; Song, W.; Gu, S.; et al. Responses of multi-trophic microbial communities to altered precipitation affected soil respiration in coastal wetlands. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 213, 106304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Guo, Y.; Liang, F.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Cao, W.; Song, H.; Chen, J.; Guo, J. Global integrative meta-analysis of the responses in soil organic carbon stock to biochar amendment. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Meng, H.; Xu, Q.; Sun, L.; Zhang, L.; Ba, Q.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Jiang, L. Contributions of microbial necromass and plant lignin to soil organic carbon stock in a paddy field under simulated conditions of long-term elevated CO2 and warming. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 201, 109649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Fang, M.; Yu, Q.; Niu, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, F.; Xu, C.; Ai, M.; Zhang, J. Study of spatialtemporal changes in Chinese forest eco-space and optimization strategies for enhancing carbon sequestration capacity through ecological spatial network theory. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 859, 160035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xu, E. Effects of agricultural land use on soil nutrients and its variation along altitude gradients in the downstream of the Yarlung Zangbo River Basin, Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gong, Z.; Liu, J. Quantitative assessment of vegetation carbon sequestration in typical natural secondary forests of the Loess Plateau: Incorporating the influences of human activities and climate variations. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 388, 126000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Lin, J.; Tian, Z.; Wu, G. Identifying driving mechanisms and relationships between supply and demand of ecosystem services based on structural equation model in the upstream segment of the Yangtze River. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 393, 127093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Setiawan, O.; Rahayu, A.A.D.; Samawandana, G.; Tata, H.L.; Dharmawan, I.W.S.; Rachmat, H.H.; Suharti, S.; Windyoningrum, A.; Khotimah, H. Unraveling land use land cover change, their driving factors, and implication on carbon storage through an integrated modelling approach. Egypt. J. Remote Sens. Space Sci. 2024, 27, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, L.; Liu, G.; Lyu, Y. Spatiotemporal variation in net primary productivity and factor detection in arid and semiarid regions of China. Ecol. Front. 2025, 45, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koimtzidis, M.; Makridis, A.; Fang, B.; Lakshmi, V.; Gemitzi, A.J. Modelling net primary productivity using near real-time land cover data and soil moisture information. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 15, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.K.; Patel, N.R.; Dadhwal, V.K. Estimation and analysis of terrestrial net primary productivity over India by remote-sensing-driven terrestrial biosphere model. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2010, 170, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Fang, J.; Yuan, J.J.P.O. Climate change and Land Use/Land Cover Change (LUCC) leading to spatial shifts in net primary productivity in Anhui Province, China. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesi, M.; Fibbi, L.; Vanucci, S.; Bottai, L.; Chirici, G.; Maselli, F. Simulating the Net Primary Production of Even-Aged Forests by the Use of Remote Sensing and Ecosystem Modelling Techniques. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Qin, J.; Lin, J. The ecological utility study on carbon metabolism of cultivated land: A case study of Hubei Province, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 365, 121531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, Y.; Singh, S.V.; Singh, S.K.; Upadhyay, S.; Nandan, R.; Rai, A.K.; Nandipamu, T.M.K.; Singh, R.K.; Chaturvedi, S.K.; Singh, A.K. Climate smart land configurations and cropping systems diversification sustaining soil–water–carbon synergy and resource use efficiency. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 21, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, W. Spatial optimization of land use and carbon storage prediction in urban agglomerations under climate change: Different scenarios and multiscale perspectives of CMIP6. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 116, 105920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Bai, Y.; Alatalo, J.M.; Shi, Y.; Yang, Z. Exploring an assessment framework for the supply–demand balance of carbon sequestration services under land use change: Towards carbon strategy. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 165, 112211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, O.A.; Sharma, V.; Kumar, S.S.; Babu, S.; Sharma, K.R.; Rathore, S.S.; Marwaha, S.; Ganai, N.A.; Dar, S.R.; Yeasin, M.; et al. Climate plays a dominant role over land management in governing soil carbon dynamics in North Western Himalayas. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 338, 117740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Bi, X.; Liu, X.; Sun, H.; Buysse, J. Exploring the application and decision optimization of climate-smart agriculture within land-energy-food-waste nexus. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 50, 536–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Guo, Z.; Askar, A.; Li, X.; Hu, Y.; Li, H.; Saria, A.E. Dynamic land cover and ecosystem service changes in global coastal deltas under future climate scenarios. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 258, 107384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazir, M.J.; Li, G.; Nazir, M.M.; Zulfiqar, F.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Iqbal, B.; Du, D. Harnessing soil carbon sequestration to address climate change challenges in agriculture. Soil Tillage Res. 2024, 237, 105959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.; Stark, F.; Fanchone, A. Modeling the effect of land use and manure management on soil carbon sequestration in tropical mixed crop-livestock systems: A case study in Guadeloupe (Caribbean). Geoderma Reg. 2025, 41, e00968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yue, W.; Wu, T.; Xiong, J.; Xia, H.; Huang, B. The Carbon Sink Conservation Areas (CSCAs) as a land use strategy for climate change mitigation. Sustain. Horiz. 2025, 15, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumara, K.; Pal, S.; Chand, P.; Kandpal, A. Carbon sequestration potential of sustainable agricultural practices to mitigate climate change in Indian agriculture: A meta-analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 697–708. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Zou, R.; Hu, Y.; Wang, L.; Xie, Y.; Tan, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, A.X.; Gong, J.; Mao, X. Sustainable utilization of cultivated land resources based on “element coupling-function synergy” analytical framework: A case study of Guangdong, China. Land Use Policy 2024, 146, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandy, A.S.; Strickland, M.S.; Lauber, C.L.; Bradford, M.A.; Fierer, N.J.G. The influence of microbial communities, management, and soil texture on soil organic matter chemistry. Geoderma 2009, 150, 278–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, R.; Kumar, A.; Mandal, D.; Tomar, J.M.S.; Jinger, D.; Islam, S.; Panwar, P.; Jayaprakash, J.; Uthappa, A.R.; Singhal, V.; et al. Mulberry based agroforestry system and canopy management practices to combat soil erosion and enhancing carbon sequestration in degraded lands of Himalayan foothills. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 24, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernadin, R.; Freddi, O.d.S.; Soares, M.B.; Rodrigues, D.d.J.; Marimon Junior, B.H.; de Lima, L.B.; Petter, F.A. Soil organic carbon dynamics in the Cerrado–Amazon ecotone: Effects of land-use change on organic carbon sequestration and losses. CATENA 2025, 259, 109366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-P.; Lin, P.-C.; Wuryandani, S.; Lin, C.-M.; Ros, G.H. Projecting food-energy-water sustainability through ecosystem service modeling under climate and land use change in a subtropical agricultural watershed. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 318, 109737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, D.; Gong, H.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Crop yield increments will enhance soil carbon sequestration in coastal arable lands by 2100. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 432, 139800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, W.W.; Philipsen, F.N.; Herold, L.; Kingsland-Mengi, A.; Laux, M.; Golestanifard, A.; Strobel, B.W.; Duboc, O. Carbon sequestration potential and fractionation in soils after conversion of cultivated land to hedgerows. Geoderma 2023, 435, 116501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Wang, Z. Multi-scenario simulation and carbon storage assessment of land use in a multi-mountainous city. Land Use Policy 2025, 153, 107529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Spatial Resolution | Source | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop distribution data | 1 km | The National Ecological Data Center | https://nesdc.org.cn/ |

| Phenological data | 1 km | ||

| Solar radiation data | 1 km | The Geographic Data Sharing Infrastructure, global resources data cloud | www.gis5g.com |

| Annual maximum Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) | 30 m | The Resources and Environmental Science and Data Center | http://www.resdc.cn/ |

| Rainfall and temperature data | 30 m | ||

| Elevation and geomorphic type data | 90 m | ||

| Crop maturity distribution data | 1 km | ||

| Potential and actual evapotranspiration data | 1 km | The National Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Science Data Center | https://www.tpdc.ac.cn/ |

| Types of Crops | (gC·MJ−1) |

|---|---|

| Wheat | 0.7 |

| Corn | 1.1 |

| Rice | 0.9 |

| Crops | Different Crop Growth Stages | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat | Sowing-overwintering | Overwintering | Greening stage | Jointing stage | Heading and flowering | Maturation stage | |

| Late October to late December | Early January to early February | Mid February to late February | Early March to late March | Early April to early May | Mid May to early June | ||

| Corn | Seedling emergence stage | Jointing stage | Boot stage | Tasseling stage | Milk ripening stage | Maturation stage | |

| Mid June to early July | Mid July | Late July to early August | Mid August | Late August to mid September | Late September | ||

| Rice | Greening stage | Early tillering stage | Late tillering stage | Boot stage | Heading stage | Milk ripening stage | Yellow ripening stage |

| Early June | Mid to late June | Early July | Mid July | late July to early August | Mid to late August | Early to mid September | |

| Influence Aspect | Evaluation Factors |

|---|---|

| Natural environmental factors | Elevation |

| Landform type | |

| Temperature | |

| Rainfall | |

| Vegetation coverage | |

| Human social factors | Crop type |

| Crop maturity |

| Illustration | Judgment Criteria | Interaction Type | |

|---|---|---|---|

| q(A ∩ B) < Min(q(A),q(B)) | nonlinear weakening | |

| Min(q(A),q(B)) < q(A ∩ B) < Max(q(A),q(B)) | single factor nonlinear weakening | |

| q(A ∩ B) > Max(q(A),q(B)) | double factor enhancement | |

| q(A ∩ B) = q(A) + q(B) | independent | |

| q(A ∩ B) > q(A) + q(B) | nonlinear enhancement | |

Min(q(A),q(B)) Min(q(A),q(B)) Max(q(A),q(B)) Max(q(A),q(B)) |  q(A) + q(B) q(A) + q(B) q(A ∩ B) q(A ∩ B) | ||

| Indicator | Crop Type | Tr-CASA Model | CASA-CGC Model | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moran’s I | Wheat | 0.49 | 0.58 | +18.4% |

| Corn | 0.52 | 0.61 | +17.3% | |

| Rice | 0.57 | 0.66 | +15.8% | |

| Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Wheat | 51.5% | 42.3% | −17.9% |

| Corn | 48.2% | 38.7% | −19.7% | |

| Rice | 43.8% | 35.4% | −19.2% |

| Carbon Sequestration Estimation Models | Tr-CASA Model | CASA-CGC Model | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | RMSE | R2 | RMSE | |

| Remote sensing inversion products | 0.62 | 18.63 | 0.79 | 14.29 |

| Ground-measured | 0.58 | 16.71 | 0.72 | 12.67 |

| Evaluation Factors | Elevation | Landform Type | Temperature | Rainfall | Vegetation Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop type | 0.289 ↑ | 0.254 ↑↑ | 0.291 ↑↑ | 0.297 ↑↑ | 0.293 ↑ |

| Crop maturity | 0.312 ↑ | 0.240 ↑↑ | 0.303 ↑ | 0.285 ↑↑ | 0.281 ↑↑ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Dong, C.; Zhang, R.; Shi, K.; Wang, Y.; Li, B. Estimation of Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land Based on Improved CASA-CGC Model—A Case Study of Anhui Province. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2462. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232462

Zhang L, Dong C, Zhang R, Shi K, Wang Y, Li B. Estimation of Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land Based on Improved CASA-CGC Model—A Case Study of Anhui Province. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2462. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232462

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lina, Chun Dong, Rui Zhang, Kaifang Shi, Yingchun Wang, and Bao Li. 2025. "Estimation of Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land Based on Improved CASA-CGC Model—A Case Study of Anhui Province" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2462. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232462

APA StyleZhang, L., Dong, C., Zhang, R., Shi, K., Wang, Y., & Li, B. (2025). Estimation of Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Cultivated Land Based on Improved CASA-CGC Model—A Case Study of Anhui Province. Agriculture, 15(23), 2462. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232462