Probabilistic Deep Learning Framework for Greenhouse Microclimate Prediction with Time-Varying Uncertainty and Covariance Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- Building a probabilistic deep neural network for the temporal projection of important greenhouse microclimate variables (internal temperature, relative humidity, and CO2 concentration).

- -

- Integration of an NLL training objective enabling concurrent generation of projections and temporal covariance, thereby encoding model variability

- -

- Deriving model variability and dependence between nonlinear variables through temporal covariance analysis using Cholesky factorization.

- -

- Introducing analytical methods to quantify the variability and reliability of network output and support the assessment of predictive reliability and resilience.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

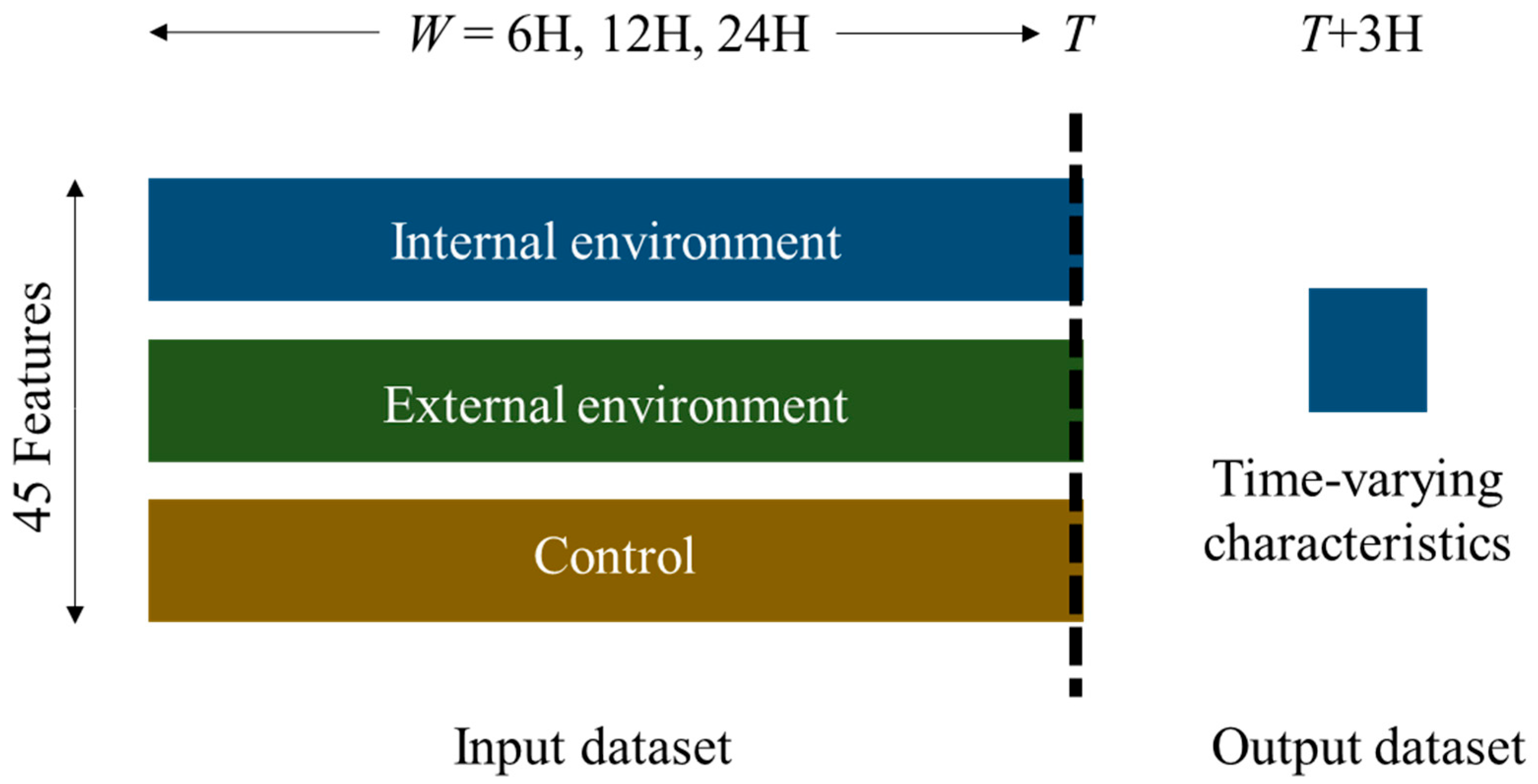

2.2. Deep Learning Model for Micro-Climate Prediction

2.2.1. Probabilistic Prediction Model Training

2.2.2. Deterministic Prediction Model Training

2.2.3. Model Performance Evaluation

2.2.4. Hyperparameters and Tuning Methods

2.3. Extracting Variance and Time-Varying Correlations

2.4. Computation

3. Results

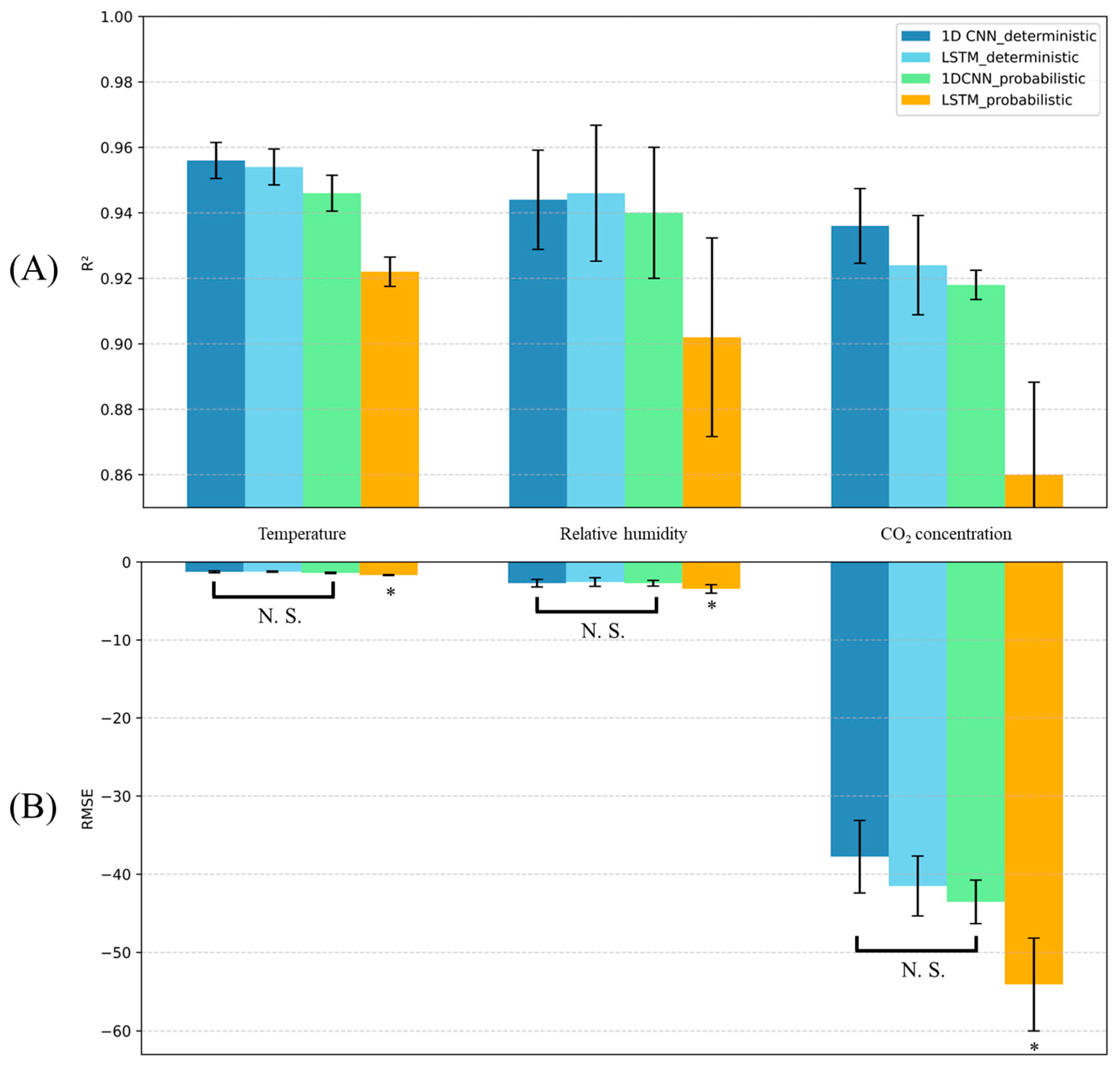

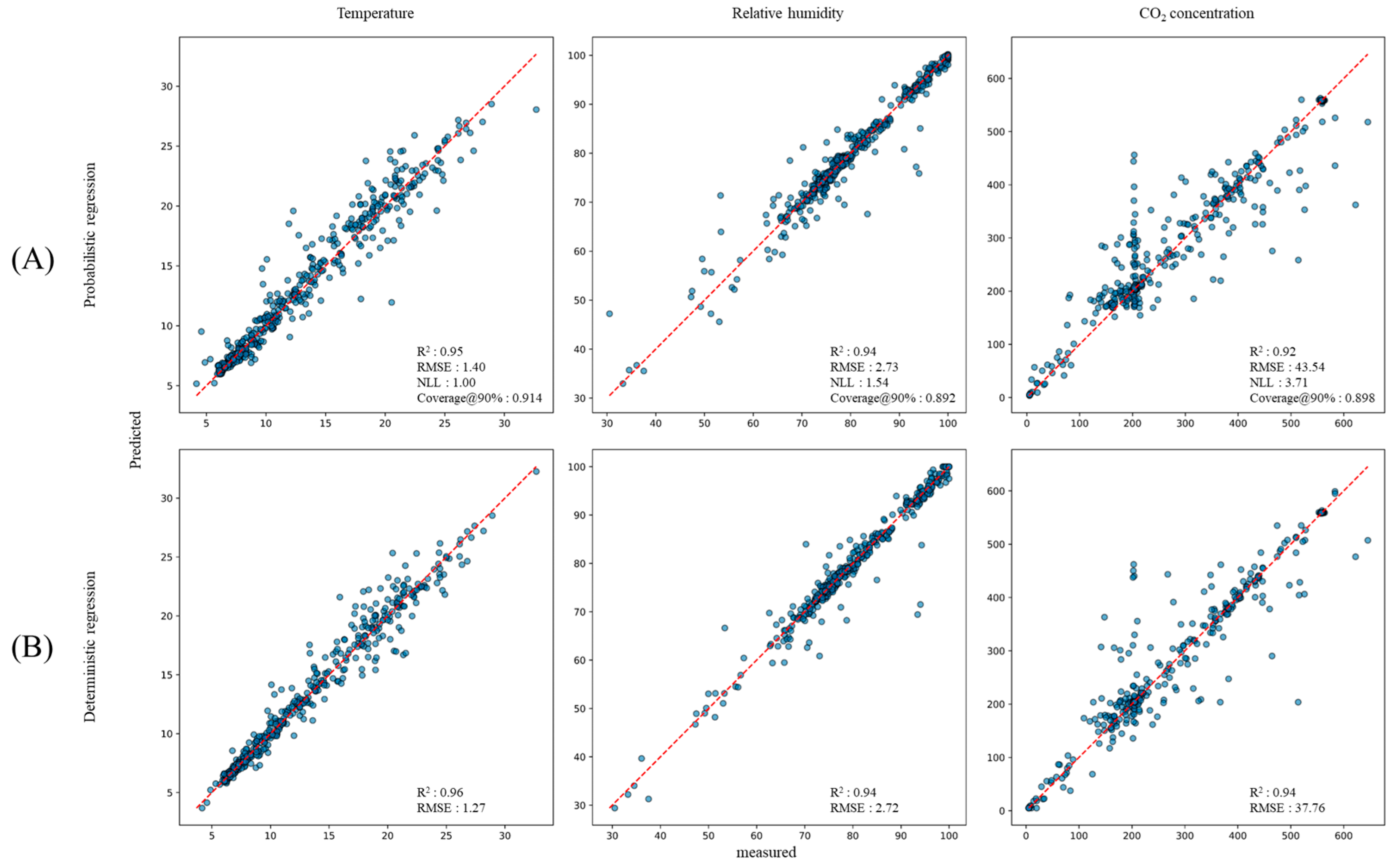

3.1. Micro-Climate Prediction Performance

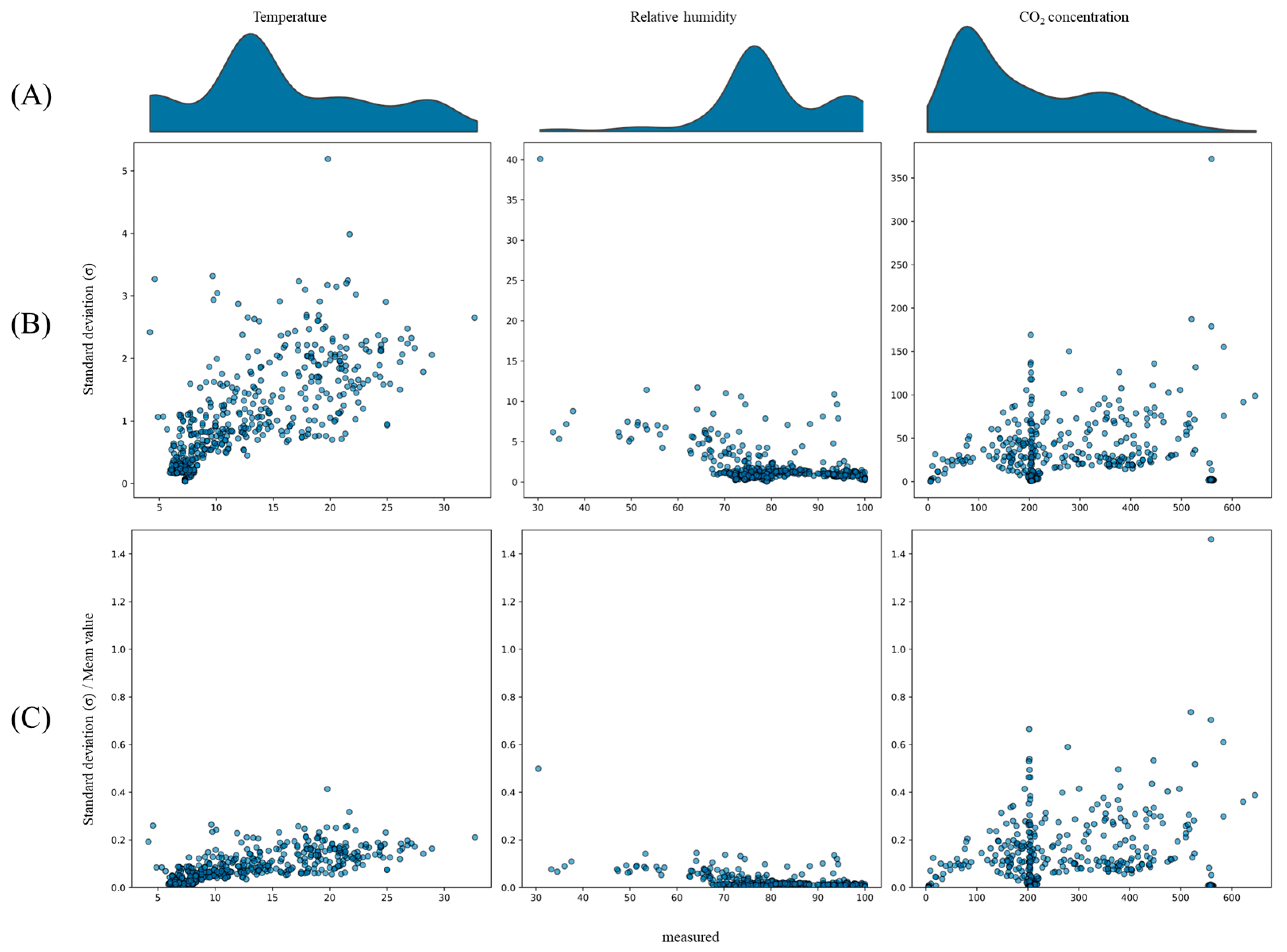

3.2. Quantitative Uncertainty Estimated from the Trained Probabilistic Model

3.3. Prediction of Time-Varying Correlations Among Microclimate Variables

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Sharpness and Calibration of the Probabilistic Model

4.2. Analysis of Uncertainty Distribution in Model Predictions

4.3. Interpretation of Time-Varying Correlations Among Microclimate Variables

4.4. Limitation and Toward Generalizable and Adaptive Greenhouse Micro-Climate Models

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sánchez-Molina, J.; Perez, N.; Rodríguez, F.; Guzmán, J.; López, J. Support system for decision making in the management of the greenhouse environmental based on growth model for sweet pepper. Agric. Syst. 2015, 139, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, S.; Zwart, F.d.; Elings, A.; Petropoulou, A.; Righini, I. Cherry tomato production in intelligent greenhouses—Sensors and AI for control of climate, irrigation, crop yield, and quality. Sensors 2020, 20, 6430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, A.; Tang, F.; Hou, P.; Lu, Y.; Yuan, P. A Review of Environmental Control Strategies and Models for Modern Agricultural Greenhouses. Sensors 2025, 25, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakis, T.; Kavga, A.; Thomopoulos, V.; Argiriou, A.A. Neural network model for greenhouse microclimate predictions. Agriculture 2022, 12, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Chang, F.-J. Empowering greenhouse cultivation: Dynamic factors and machine learning unite for advanced microclimate prediction. Water 2023, 15, 3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, O.S.; Usigbe, M.J.; Aboyeji, E.; Uyeh, D.D.; Ha, Y.; Park, T.; Mallipeddi, R. Greenhouse micro-climate prediction based on fixed sensor placements: A machine learning approach. Mathematics 2023, 11, 3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Yuan, P.; Liang, L.; Gao, L.; Li, M.; Diao, M. Integration of deep learning and sparrow search algorithms to optimize greenhouse microclimate prediction for seedling environment suitability. Agronomy 2024, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, M.; Daniels, A.; García-Mañas, F.; Rodríguez, F.; Leibold, M.; Wollherr, D. Learning-based model identification for greenhouse climate control. at-Automatisierungstechnik 2025, 73, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Sun, C.; Zhao, J.; Ma, L.; Zheng, W.; Xie, Q.; Wei, X. Prediction and control of greenhouse temperature: Methods, applications, and future directions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 237, 110603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajagekar, A.; Mattson, N.S.; You, F. Energy-efficient ai-based control of semi-closed greenhouses leveraging robust optimization in deep reinforcement learning. Adv. Appl. Energy 2023, 9, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, S.; Airaldi, F.; Dabiri, A.; Sun, C.; De Schutter, B. Reinforcement learning-based model predictive control for greenhouse climate control. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 10, 100751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, F.; Govindan, R.; Bermak, A.; Yang, D.; Al-Ansari, T. Data-driven robust model predictive control for greenhouse temperature control and energy utilisation assessment. Appl. Energy 2023, 343, 121190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; You, F. Efficient greenhouse temperature control with data-driven robust model predictive. In Proceedings of the 2020 American Control Conference (ACC), Denver, CO, USA, 1–3 July 2020; pp. 1986–1991. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Guo, X.; Ding, M.; Ye, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Li, J. SHAP values accurately explain the difference in modeling accuracy of convolution neural network between soil full-spectrum and feature-spectrum. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 217, 108627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, A.; Balaji, K.; Lalani, Z. Temporal encoding strategies for energy time series prediction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.15456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.Y.; Kim, Y.; Park, H.; Park, S.H.; Suh, H.K. Evaluating Time-Series Prediction of Temperature, Relative Humidity, and CO2 in the Greenhouse with Transformer-Based and RNN-Based Models. Agronomy 2024, 14, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Ercan, A.; Nagasato, T.; Kiyama, M.; Amagasaki, M. Use of 1D-CNN for input data size reduction of LSTM in Hourly Rainfall-Runoff modeling. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.04732. [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiranyaz, S.; Ince, T.; Gabbouj, M. Real-time patient-specific ECG classification by 1-D convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2015, 63, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangapuram, S.S.; Seeger, M.W.; Gasthaus, J.; Stella, L.; Wang, Y.; Januschowski, T. Deep state space models for time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018; Volume 31. [Google Scholar]

- Salinas, D.; Flunkert, V.; Gasthaus, J.; Januschowski, T. DeepAR: Probabilistic forecasting with autoregressive recurrent networks. Int. J. Forecast. 2020, 36, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, R.; Tung, F.; Oliveira, G.L. Heterogeneous multi-task learning with expert diversity. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 2022, 19, 3093–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebold, F.X.; Mariano, R.S. Comparing predictive accuracy. J. Bus. Econ. Stat. 2002, 20, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand. J. Stat. 1979, 6, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarayanan, B.; Pritzel, A.; Blundell, C. Simple and scalable predictive uncertainty estimation using deep ensembles. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Gneiting, T.; Balabdaoui, F.; Raftery, A.E. Probabilistic forecasts, calibration and sharpness. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 2007, 69, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovadia, Y.; Fertig, E.; Ren, J.; Nado, Z.; Sculley, D.; Nowozin, S.; Dillon, J.; Lakshminarayanan, B.; Snoek, J. Can you trust your model’s uncertainty? evaluating predictive uncertainty under dataset shift. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Kuleshov, V.; Fenner, N.; Ermon, S. Accurate uncertainties for deep learning using calibrated regression. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 2796–2804. [Google Scholar]

- Malinin, A.; Gales, M. Reverse KL-divergence training of prior networks: Improved uncertainty and adversarial robustness. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, D.; Carpenter, N.; Maki, H.; Rehman, T.U.; Tuinstra, M.R.; Jin, J. Greenhouse environment modeling and simulation for microclimate control. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, C.M.; Franses, P.H. A Generalized Dynamic Conditional Correlation Model for Many Asset Returns. 2003. Available online: https://repub.eur.nl/pub/1718/feweco20030708113101.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ding, Z.; Granger, C.W. Modeling volatility persistence of speculative returns: A new approach. J. Econom. 1996, 73, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.W.; Weiss, A.A. Time series analysis of error-correction models. In Studies in Econometrics, Time Series, and Multivariate Statistics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983; pp. 255–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, J.; Bot, G.; Challa, H.; Van de Braak, N. Greenhouse Climate Control: An Integrated Approach; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Eraliev, O.; Lee, C.-H. Performance analysis of time series deep learning models for climate prediction in indoor hydroponic greenhouses at different time intervals. Plants 2023, 12, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Deng, W. Deep visual domain adaptation: A survey. Neurocomputing 2018, 312, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Chandra, R.; Bansal, C.; Kalyanaraman, S.; Ganu, T.; Grant, M. Micro-climate prediction-multi scale encoder-decoder based deep learning framework. In Proceedings of the 27th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Virtual, 14–18 August 2021; pp. 3128–3138. [Google Scholar]

| Factor | Values | Outlier |

|---|---|---|

| Internal temperature (°C) | 2.75 to 32.67 | 18 |

| Internal relative humidity (%) | 28.92 to 99.33 | 37 |

| Internal CO2 concentration (ppm) | 120.5 to 671 | 23 |

| External temperature (°C) | −10.4 to 28.3 | 11 |

| External relative humidity (%) | 16 to 100 | 17 |

| Precipitation (mm) | 0 to 45.3 | 0 |

| Wind speed (m/s) | 0 to 6.7 | 9 |

| Wind direction (°) | 0 to 360 | 0 |

| Radiation (W/m2) | 0 to 850.83 | 39 |

| Snowfall (cm) | 0 to 5.7 | 0 |

| Ground temperature (°C) | −8 to 42.7 | 23 |

| Up window (left, right—01 to 04) (%) | 0, 50, 100 | 0 |

| Side window (left, right—01 to 04) (%) | 0, 50, 100 | 0 |

| Curtain (up, down, left, right—01 to 04) (%) | 0, 50, 100 | 0 |

| Algorithm | LSTM Probabilistic | 1D CNN Probabilistic |

|---|---|---|

| Input size | (N, W, 45) | |

| Hidden layers | LSTM (128) Layer normalization LSTM (128) Layer normalization Global average pooling Dense (512) Dense (512) | 1D Conv (128) Batch normalization Spatial dropout 1D Conv (128) Batch normalization Spatial dropout Global average pooling Dense (512) Dense (512) |

| outputs | Dense (9) | Dense (9) |

| Algorithm | LSTM Deterministic | 1D CNN Deterministic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input size | (N, W, 45) | |||||

| Hidden layers | LSTM (128) Layer normalization LSTM (128) Layer normalization Global average pooling | 1D Conv (128) Batch normalization Spatial dropout 1D Conv (128) Batch normalization Spatial dropout Global average pooling | ||||

| MTL | Dense (128) Dense (128) | Dense (128) Dense (128) | Dense (128) Dense (128) | Dense (128) Dense (128) | Dense (128) Dense (128) | Dense (128) Dense (128) |

| outputs | Dense (1) | Dense (1) | Dense (1) | Dense (1) | Dense (1) | Dense (1) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, W.-J.; Yang, M. Probabilistic Deep Learning Framework for Greenhouse Microclimate Prediction with Time-Varying Uncertainty and Covariance Analysis. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232461

Choi W-J, Yang M. Probabilistic Deep Learning Framework for Greenhouse Microclimate Prediction with Time-Varying Uncertainty and Covariance Analysis. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232461

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Woo-Joo, and Myongkyoon Yang. 2025. "Probabilistic Deep Learning Framework for Greenhouse Microclimate Prediction with Time-Varying Uncertainty and Covariance Analysis" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232461

APA StyleChoi, W.-J., & Yang, M. (2025). Probabilistic Deep Learning Framework for Greenhouse Microclimate Prediction with Time-Varying Uncertainty and Covariance Analysis. Agriculture, 15(23), 2461. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232461