The Burden of Heart Failure in End-Stage Renal Disease: Insights from a Retrospective Cohort of Hemodialysis Patients

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

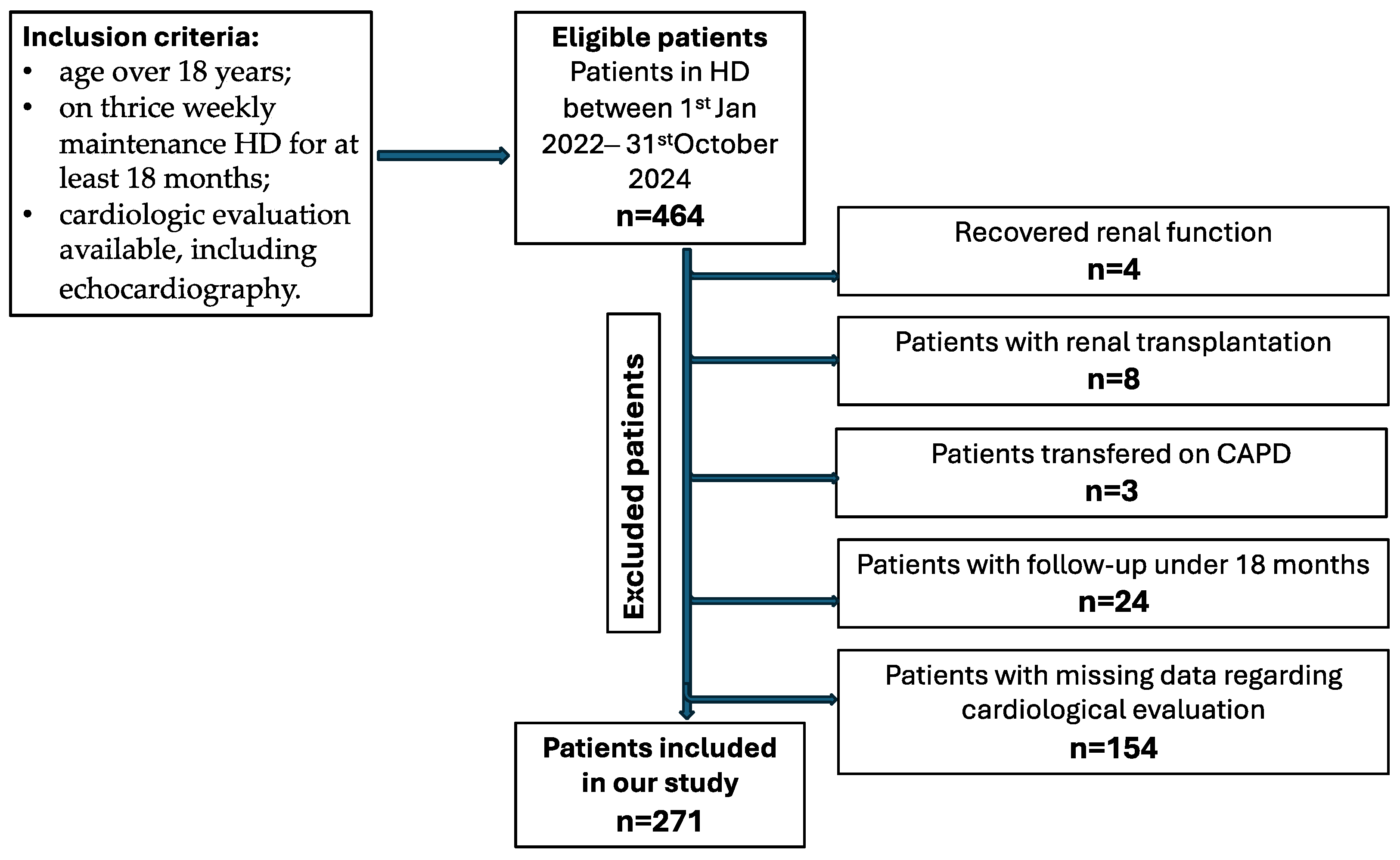

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. HF Definition and Classification

2.3. Study Objectives and Endpoints

- Primary objective: To evaluate the prevalence and main characteristics of HF in patients receiving chronic HD and assess clinical and laboratory characteristics associated with HF in this population and identification of independent predictors of HF (including comorbidities, dialysis-related parameters, and biomarkers).

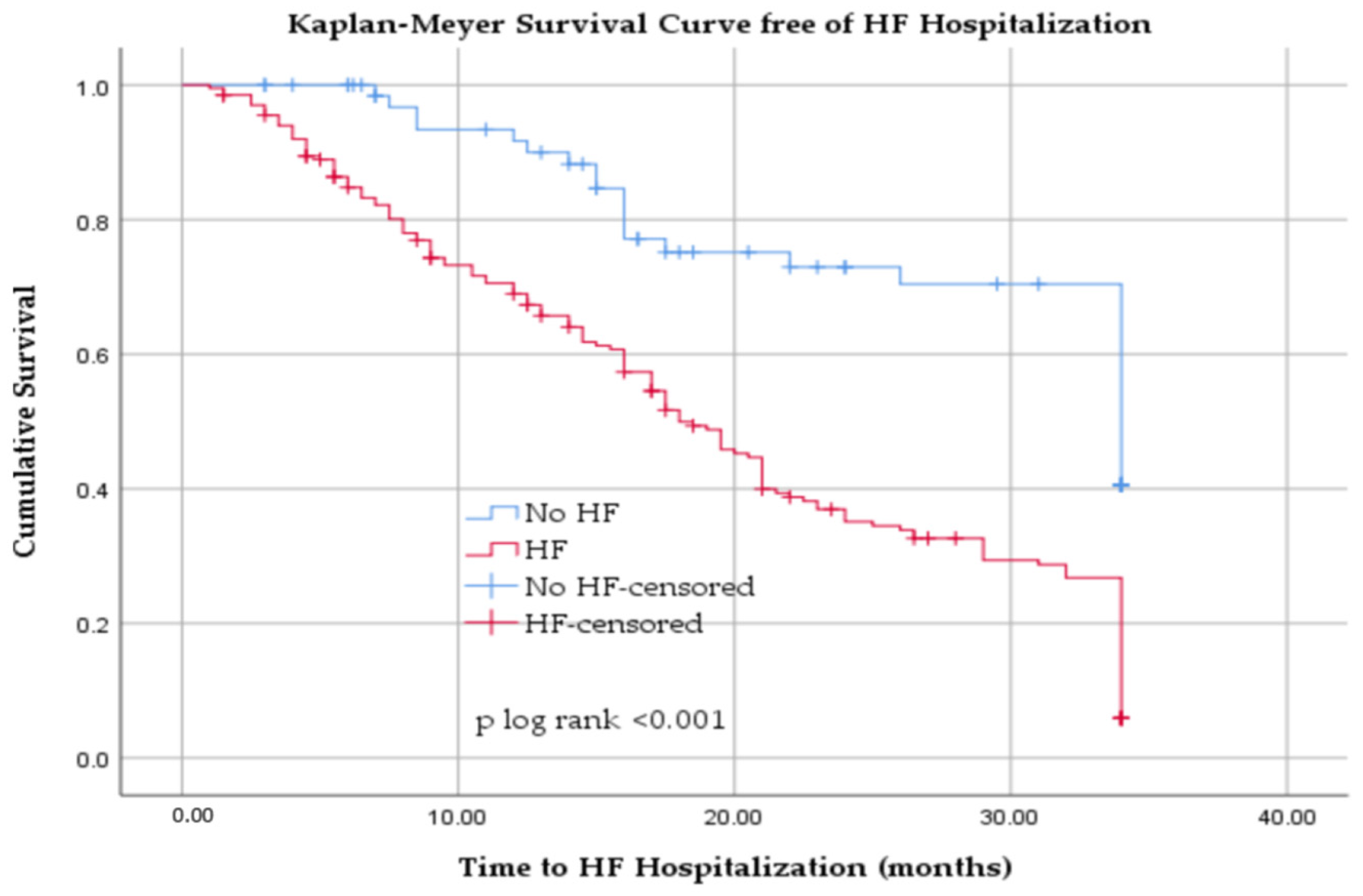

- Secondary objectives: To assess prognostic impact of HF among HD patients.

- (a)

- Primary endpoint: all-cause and cardiovascular mortality;

- (b)

- Secondary endpoint: hospitalization for HF defined as inpatient admission with principal HF diagnosis (e.g., I.50) including emergency stay over 24 h.

2.4. Data Sources and Collection

- (a)

- Demographic data: age, sex, body mass index (BMI).

- (b)

- Dialysis data: dialysis vintage (years), HD type (high flux/hemodiafiltration), dialysis efficacy (Kt/V), ultrafiltration rate mL/kg/h (UFR), interdialytic weight gain (%), UF net volume (Braun Dialog+ and Fresenius 4008s were the HD machines used during the study). The water-purifying stations supplied pure water under 0.1 UFC/mL. Polysulfone membrane dialyzers (Elisio/Nipro/Japan, FX-Fresenius, Diacap Pro Braun) were used, 1.9–2.1 m2 (ultrafiltration coefficient) Kuf 75–82 mL/h/mmHg, gamma-ray sterilization and helix one, 1.8–2.2 m2, UF coefficient 53–68 mL/h/mmHg, inline steam sterilization, at 121 degrees Celsius, 15 min. The recommended target Kt/V was set between 1.2 and 1.4 for patients receiving thrice-weekly HD.

- (c)

- Cardiac parameters: NT-proBNP, hs-troponin I, complete transthoracic echocardiographic evaluation. Both hs-troponin I (normal ranges 13.8–17.5 ng/L) and NT-proBNP (normal ranges 10.5–125 pg/mL) were assessed using chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) on an Abbott ALINITY Ac03837 analyzer (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL, USA). Transthoracic echocardiography was performed on a LOGIQ P7 Ultrasound System from General Electric Healthcare. The left ventricular EF was determined based on the modified Simpson rule. The measurements were carried out when patients were close to dry weight, preferably on a no-dialysis day. The patients were assessed echocardiographically by the cardiology team at our hospital, with all examinations conducted using the same equipment to ensure consistency. Additionally, to reduce potential bias resulting from volume overload in the evaluation of cardiac structure and performance, echocardiographic examinations were scheduled and performed after HD, usually on the day after the procedure.

- (d)

- Comorbidities: arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease (CAD), myocardial infarction (MI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), permanent AF.

- (e)

- Laboratory parameters: measurements for total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, calcium, phosphate were performed using CMIA technique on Abbott ALINITY AC06028 analyzer, whereas hemoglobin level was assessed on Abbott ALINITY HQ00687 analyzer (CMIA).

- (f)

- The use of medication: B-blockers (BB), statins, renin–angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of Study Cohort

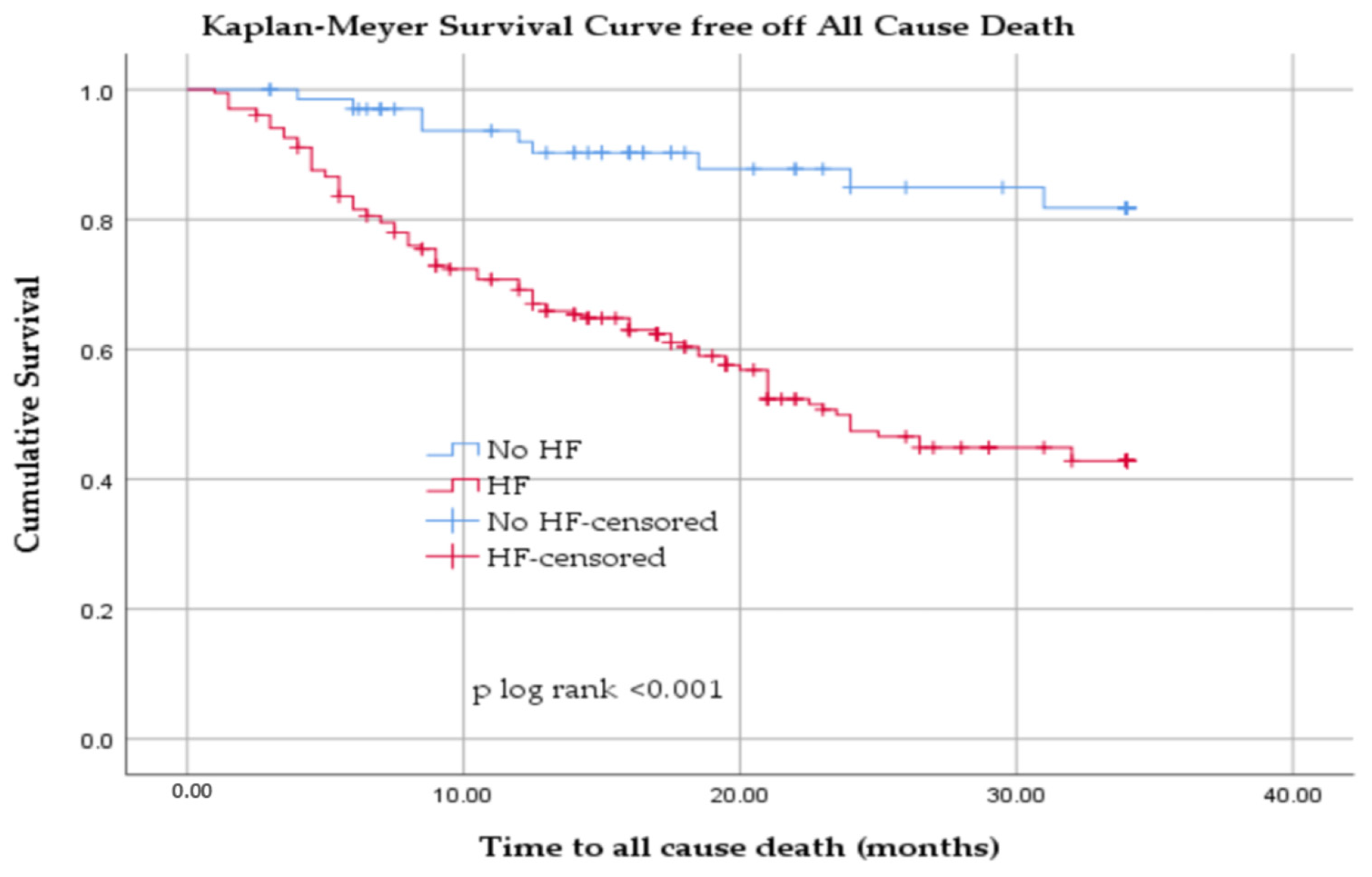

3.2. All-Cause Mortality in Hemodialyzed Patients with and Without HF

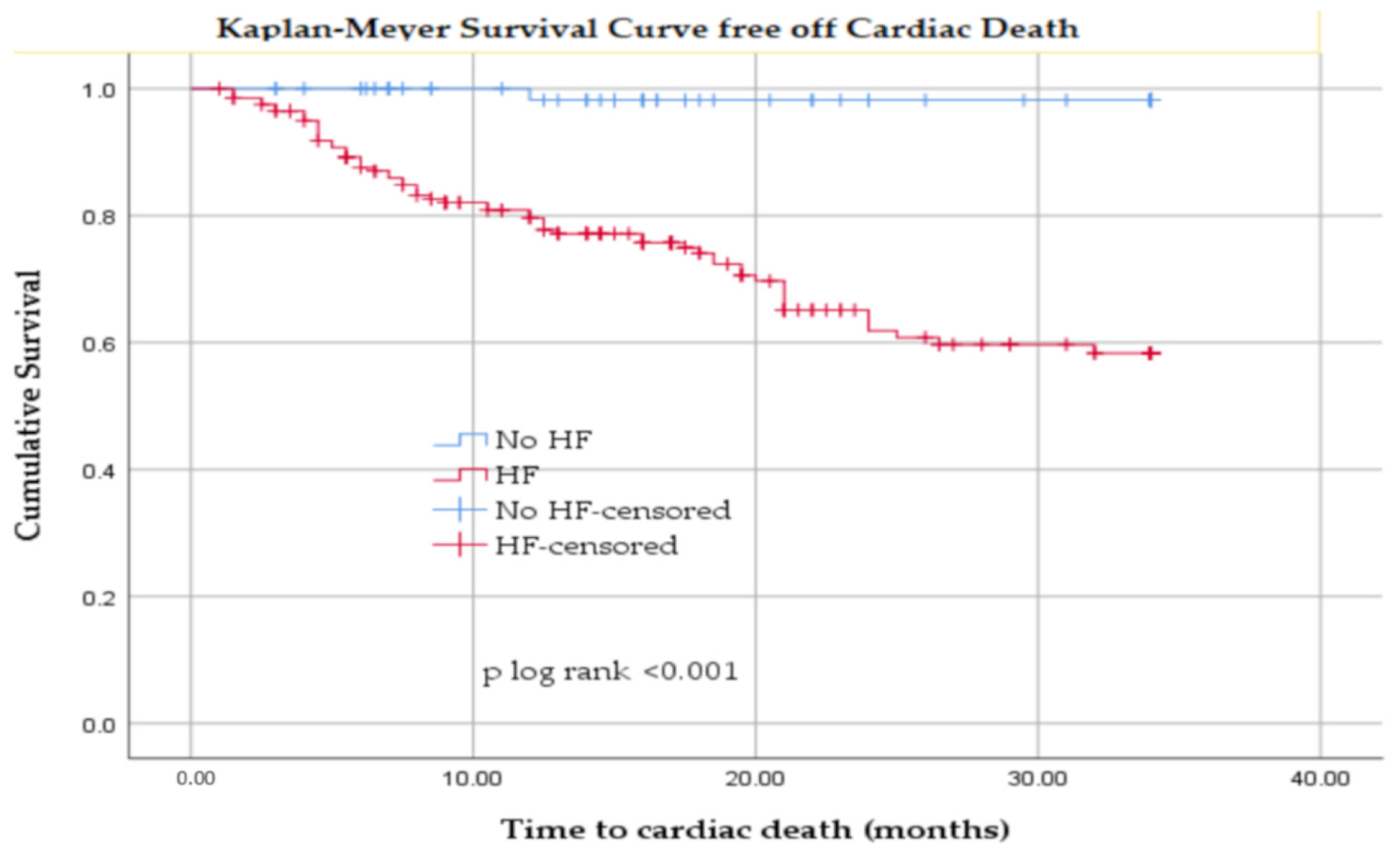

3.3. Cardiovascular Mortality in Hemodialyzed Patients with and Without HF

3.4. Hospitalization for Heart Failure in Hemodialyzed Patients

4. Discussion

4.1. Heart Failure Burden, Diagnosis and Management in Dialysis Patients

4.2. Cardiovascular Comorbidities as Drivers of Prognosis

4.3. Ejection Fraction and HF Phenotypes

4.4. Biomarkers of Cardiac Stress

4.5. Fluid Overload and Dialysis-Related Factors

4.6. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jager, K.J.; Åsberg, A.; Collart, F.; Couchoud, C.; Evans, M.; Finne, P.; Peride, I.; Rychlik, I.; Massy, Z.A. A Snapshot of European Registries on Chronic Kidney Disease Patients Not on Kidney Replacement Therapy. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2021, 37, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jager, K.J.; Kovesdy, C.; Langham, R.; Rosenberg, M.; Jha, V.; Zoccali, C. A Single Number for Advocacy and Communication—Worldwide More than 850 Million Individuals Have Kidney Diseases. Kidney Int. 2019, 96, 1048–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boenink, R.; Bonthuis, M.; Boerstra, B.A.; Astley, M.E.; Montez de Sousa, I.R.; Helve, J.; Komissarov, K.S.; Comas, J.; Radunovic, D.; Buchwinkler, L.; et al. The ERA Registry Annual Report 2022: Epidemiology of Kidney Replacement Therapy in Europe, with a Focus on Sex Comparisons. Clin. Kidney J. 2025, 18, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USRDS. United States Renal Data System Annual Data Report Incidence, Prevalence, End Stage Renal Disease: Chapter 1 Patient Characteristics, and Treatment Modalities. Available online: https://usrds-adr.niddk.nih.gov/2023/end-stage-renal-disease/1-incidence-prevalence-patient-characteristics-and-treatment-modalities (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Tumlin, J.A.; Koplan, B.A.; Costea, A.I.; Kher, V.; Williamson, D.; Pokhariyal, S.; Charytan, D.M.; Williamson, D.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; et al. Primary Outcomes of the Monitoring in Dialysis Study Indicate That Clinically Significant Arrhythmias Are Common in Hemodialysis Patients and Related to Dialytic Cycle. Kidney Int. 2018, 93, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccali, C.; Mallamaci, F.; Adamczak, M.; De Oliveira, R.B.; Massy, Z.A.; Sarafidis, P.; Agarwal, R.; Mark, P.B.; Kotanko, P.; Ferro, C.J.; et al. Cardiovascular Complications in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Review from the European Renal and Cardiovascular Medicine Working Group of the European Renal Association. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 2017–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonescu, A.; Vicas, S.I.; Teusdea, A.C.; Ratiu, I.; Antonescu, I.A.; Micle, O.; Vicas, L.; Muresan, M.; Gligor, F. The levels of serum biomarkers of inflammation in hemodialysis patients. Farmacia 2014, 62, 950–960. [Google Scholar]

- Micle, O.; Vicas, S.I.; Ratiu, I.; Vicas, L. Cystatin C, a low molecular weight protein in chronic renal failure—Farm. J. Available online: https://farmaciajournal.com/issue-articles/cystatin-c-a-low-molecular-weight-protein-in-chronic-renal-failure/ (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Ratiu, I.A.; Moisa, C.F.; Țiburcă, L.; Hagi-Islai, E.; Ratiu, A.; Bako, G.C.; Ratiu, C.A.; Stefan, L. Antimicrobial Treatment Challenges in the Management of Infective Spondylodiscitis Associated with Hemodialysis: A Comprehensive Review of Literature and Case Series Analysis. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, K.S.; Espersen, C.; Curtis, K.A.; Cunningham, J.W.; Jering, K.S.; Prasad, N.G.; Platz, E.; Causland, F.R.M. Temporal Changes in Electrolytes, Acid-Base, QTc Duration, and Point-of-Care Ultrasound during Inpatient Hemodialysis Sessions. Kidney360 2022, 3, 1217–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Rooij, E.N.M.; Dekker, F.W.; Le Cessie, S.; Hoorn, E.J.; de Fijter, J.W.; Hoogeveen, E.K.; Bijlsma, J.A.; Boekhout, M.; Boer, W.H.; van der Boog, P.J.M.; et al. Serum Potassium and Mortality Risk in Hemodialysis Patients: A Cohort Study. Kidney Med. 2022, 4, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Planchat, A.; Robert-Ebadi, H.; Saudan, P.; Jaques, D. Répercussions Hémodynamiques et Cardiovasculaires Des Fistules Artérioveineuses En Hémodialyse. Available online: https://www.revmed.ch/revue-medicale-suisse/2022/revue-medicale-suisse-771/repercussions-hemodynamiques-et-cardiovasculaires-des-fistules-arterioveineuses-en-hemodialyse (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Glerup, R.; Svensson, M.; Jensen, J.D.; Christensen, J.H. Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia Risk in Hemodialysis Patients Using the Buttonhole Cannulation Technique: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Kidney Med. 2019, 1, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, R.; Sousa, L.; Cristóvão, A.F. Cannulation Technique of Vascular Access in Haemodialysis and the Impact on the Arteriovenous Fistula Survival: Protocol of Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labriola, L.; Crott, R.; Desmet, C.; Romain, C.; Jadoul, M. Infectious Complications Associated with Buttonhole Cannulation of Native Arteriovenous Fistulas: A 22-Year Follow-Up. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2024, 39, 1000–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almenara-Tejederas, M.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.A.; Moyano-Franco, M.J.; de Cueto-López, M.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Salgueira-Lazo, M. Tunneled Catheter-Related Bacteremia in Hemodialysis Patients: Incidence, Risk Factors and Outcomes. A 14-Year Observational Study. J. Nephrol. 2023, 36, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rubio, M.; Lago-Rodríguez, M.O.; Ordieres-Ortega, L.; Oblitas, C.M.; Moragón-Ledesma, S.; Alonso-Beato, R.; Alvarez-Sala-Walther, L.A.; Galeano-Valle, F. A Comprehensive Review of Catheter-Related Thrombosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadi, R.; Sakr, F.; Aridi, H.; Alameddine, Z.; Dimachkie, R.; Assaad, M.; Asmar, S.; ElSayegh, S. Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 2023, 29, 10760296231177993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.R.; Hornig, C.; Canaud, B. Systematic Review to Compare the Outcomes Associated with the Modalities of Expanded Hemodialysis (HDx) versus High-Flux Hemodialysis and/or Hemodiafiltration (HDF) in Patients with End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD). Semin. Dial. 2023, 36, 86–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, N.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y. Variation of Brain Natriuretic Peptide Assists with Volume Management and Predicts Prognosis of Hemodialysis Patients. Postgrad. Med. J. 2025, 101, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzot, M.; Seris, P.; Maheas, C.; Vanmassenhove, J.; Langlois, A.L.; Moubakir, K.; Laplanche, S.; Petitclerc, T.; Ridel, C.; Lavielle, M. Mathematical Model to Predict B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Levels in Haemodialysis Patients. Nephrology 2020, 25, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laveborn, E.; Lindmark, K.; Skagerlind, M.; Stegmayr, B. NT-ProBNP and Troponin T Levels Differ after Haemodialysis with a Low versus High Flux Membrane. Int. J. Artif. Organs 2015, 38, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, L.H.; Van De Kerkhof, J.J.; Mingels, A.M.; Passos, V.L.; Kleijnen, V.W.; Mazairac, A.H.; Van Der Sande, F.M.; Wodzig, W.K.; Konings, C.J.; Leunissen, K.M.; et al. Inflammation, Overhydration and Cardiac Biomarkers in Haemodialysis Patients: A Longitudinal Study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2010, 25, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Kishimoto, H.; Tokumoto, M. Direct and Indirect Effects of Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 on the Heart. Front. Endocrinol 2023, 14, 1059179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisavu, L.; Ivan, V.M.; Mihaescu, A.; Chisavu, F.; Schiller, O.; Marc, L.; Bob, F.; Schiller, A. Novel Biomarkers in Evaluating Cardiac Function in Patients on Hemodialysis-A Pilot Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, A.; Burney, H.N.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Tomkins, C.; Siedlecki, A.M.; Lu, T.S.; Kalim, S.; Thadhani, R.; Moe, S.; et al. FGF23 and Cardiovascular Structure and Function in Advanced Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney360 2022, 3, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.; Misialek, J.R.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Selvin, E.; Coresh, J.; Chen, L.Y.; Soliman, E.Z.; Agarwal, S.K.; Lutsey, P.L. Circulating Fibroblast Growth Factor-23 and the Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e001082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Maaten, J.M.; Voors, A.A.; Damman, K.; van der Meer, P.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.; van der Harst, P.; Hillege, H.L.; et al. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 Is Related to Profiles Indicating Volume Overload, Poor Therapy Optimization and Prognosis in Patients with New-Onset and Worsening Heart Failure. Int. J. Cardiol. 2018, 253, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, L.; Bigotte Vieira, M.; Neves, J.S. Association of Combined Fractional Excretion of Phosphate and FGF23 with Heart Failure and Cardiovascular Events in Moderate and Advanced Renal Disease. J. Nephrol. 2023, 36, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untersteller, K.; Seiler-Mußler, S.; Mallamaci, F.; Fliser, D.; London, Ǵ.M.; Zoccali, C.; Heine, G.H. Validation of Echocardiographic Criteria for the Clinical Diagnosis of Heart Failure in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2018, 33, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- House, A.A.; Wanner, C.; Sarnak, M.J.; Piña, I.L.; McIntyre, C.W.; Komenda, P.; Kasiske, B.L.; Deswal, A.; deFilippi, C.R.; Cleland, J.G.F.; et al. Heart Failure in Chronic Kidney Disease: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2019, 95, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, L.S.; Bellomo, R.; Bihorac, A.; Goldstein, S.L.; Siew, E.D.; Bagshaw, S.M.; Bittleman, D.; Cruz, D.; Endre, Z.; Fitzgerald, R.L.; et al. Acute Kidney Disease and Renal Recovery: Consensus Report of the Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) 16 Workgroup. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2017, 13, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, T.A.; Metra, M.; Adamo, M.; Baumbach, A.; Böhm, M.; Burri, H.; Čelutkiene, J.; Chioncel, O.; Cleland, J.G.F.; Coats, A.J.S.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.Y.M. Clinical Utility of Natriuretic Peptides in Dialysis Patients. Semin. Dial. 2012, 25, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artunc, F.; Mueller, C.; Breidthardt, T.; Twerenbold, R.; Rettig, I.; Usta, E.; Häring, H.U.; Friedrich, B. Comparison of the Diagnostic Performance of Three Natriuretic Peptides in Hemodialysis Patients: Which Is the Appropriate Biomarker? Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2012, 36, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harnett, J.D.; Foley, R.N.; Kent, G.M.; Barre, P.E.; Murray, D.; Parfrey, P.S. Congestive Heart Failure in Dialysis Patients: Prevalence, Incidence, Prognosis and Risk Factors. Kidney Int. 1995, 47, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, N.K.; Karimi Galougahi, K.; Paz, Y.; Nazif, T.; Moses, J.W.; Leon, M.B.; Stone, G.W.; Kirtane, A.J.; Karmpaliotis, D.; Bokhari, S.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Cardiovascular Disease in Advanced and End-Stage Renal Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segall, L.; Nistor, I.; Covic, A. Heart Failure in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Integrative Review. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 937398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trespalacios, F.C.; Taylor, A.J.; Agodoa, L.Y.; Bakris, G.L.; Abbott, K.C. Heart Failure as a Cause for Hospitalization in Chronic Dialysis Patients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003, 41, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, J.; Valerianova, A.; Pesickova, S.S.; Michalickova, K.; Hladinova, Z.; Hruskova, Z.; Bednarova, V.; Rocinova, K.; Tothova, M.; Kratochvilova, M.; et al. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction Is the Most Frequent but Commonly Overlooked Phenotype in Patients on Chronic Hemodialysis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 10, 1130618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, S.; Kümpers, P.; Seidler, V.; Biertz, F.; Haller, H.; Fliser, D. Diagnostic Value of N-Terminal pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide (NT-ProBNP) for Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Stage 5 on Haemodialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 2008, 23, 1370–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, E.; Umukoro, P.E.; Burney, H.N.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Lane, K.A.; Sher, S.J.; Lu, T.S.; Moe, S.M.; Moorthi, R.; et al. Initiation of Dialysis Is Associated with Impaired Cardiovascular Functional Capacity. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, 25656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.H.; Tu, K.C.; Hung, K.C.; Chuang, M.H.; Chen, J.Y. Impact of Type of Dialyzable Beta-Blockers on Subsequent Risk of Mortality in Patients Receiving Dialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, A.K.; Duval, S.; Manske, C.; Vazquez, G.; Barber, C.; Miller, L.; Luepker, R.V. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers in Patients with Congestive Heart Failure and Chronic Kidney Disease. Am. Heart J. 2007, 153, 1064–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.E.; Lazarus, J.M.; Hakim, R.M. Digoxin Associates with Mortality in ESRD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 21, 1550–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.V.; Le, T.N.; Truong, B.Q.; Nguyen, H.T.T. Efficacy and Safety of Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure Patients with End-Stage Kidney Disease on Maintenance Dialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2025, 27, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovanovici, D.C.; Bungau, S.G.; Vesa, C.M.; Moisi, M.; Babes, E.E.; Tit, D.M.; Horvath, T.; Behl, T.; Rus, M. Reviewing the Modern Therapeutical Options and the Outcomes of Sacubitril/Valsartan in Heart Failure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratiu, I.A.; Filip, L.; Moisa, C.; Ratiu, C.A.; Olariu, N.; Grosu, I.D.; Bako, G.C.; Ratiu, A.; Indries, M.; Fratila, S.; et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on Long-Term Mortality in Maintenance Hemodialysis: 5 Years Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratiu, I.A.; Mihaescu, A.; Olariu, N.; Ratiu, C.A.; Cristian, B.G.; Ratiu, A.; Indries, M.; Fratila, S.; Dejeu, D.; Teusdea, A.; et al. Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Hemodialysis Patients in the Era of Direct-Acting Antiviral Treatment: Observational Study and Narrative Review. Medicina 2024, 60, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B.; Ławiński, J.; Gluba-Brzózka, A. Oxidative Stress in ESRD Patients on Dialysis and the Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotariu, D.; Babes, E.E.; Tit, D.M.; Moisi, M.; Bustea, C.; Stoicescu, M.; Radu, A.F.; Vesa, C.M.; Behl, T.; Bungau, A.F.; et al. Oxidative Stress—Complex Pathological Issues Concerning the Hallmark of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disorders. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 152, 113238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, C.A.; Asinger, R.W.; Berger, A.K.; Charytan, D.M.; Díez, J.; Hart, R.G.; Eckardt, K.U.; Kasiske, B.L.; McCullough, P.A.; Passman, R.S.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease. A Clinical Update from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 572–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaj-Tunduc, I.P.; Brisc, C.M.I.; Brisc, C.M.; Zaha, D.C.; Buştea, C.M.; Babeş, V.V.; Sirca-Tirla, T.; Muste, F.A.; Babeş, E.E. The Role of Myocardial Revascularization in Ischemic Heart Failure in the Era of Modern Optimal Medical Therapy. Medicina 2025, 61, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pun, P.H.; Herzog, C.A.; Middleton, J.P. Improving Ascertainment of Sudden Cardiac Death in Patients with End Stage Renal Disease. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2012, 7, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkelmayer, W.C.; Patrick, A.R.; Liu, J.; Brookhart, M.A.; Setoguchi, S. The Increasing Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation among Hemodialysis Patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2011, 22, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Qiu, L.; Long, M.; Zeng, H.; Lu, Z.; Liu, L.; Lin, Y.; Ye, K.; Qin, S.; Wu, Q.; et al. Prevalence and Prognostic Impact of Abnormal Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction in Hemodialysis Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease. BMC Nephrol. 2025, 26, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehm, B.; Gulati, G.; Weiner, D.E. Heart Failure Management in Dialysis Patients: Many Treatment Options with No Clear Evidence. Semin. Dial. 2020, 33, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antlanger, M.; Aschauer, S.; Kopecky, C.; Hecking, M.; Kovarik, J.J.; Werzowa, J.; Mascherbauer, J.; Genser, B.; Säemann, M.D.; Bonderman, D. Heart Failure with Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction in Hemodialysis Patients: Prevalence, Disease Prediction and Prognosis. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2017, 42, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, T.; Akamatsu, K. Echocardiographic Manifestations in End-Stage Renal Disease. Heart Fail. Rev. 2024, 29, 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, K.; Kinugawa, K. Diagnosis and Treatment of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in Patients on Hemodialysis. Ren. Replace. Ther. 2024, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, G.; Chen, S. Analysis of Risk Factors and Application of Risk Management Strategies in Hemodialysis Patients Complicated with Heart Failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1600223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, J.A.; Coca, S.G.; Moledina, D.G.; Gentry, M.; Testani, J.M.; Parikh, C.R. Amino-Terminal Pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide for Diagnosis and Prognosis in Patients with Renal Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Heart Fail. 2015, 3, 977–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriguchi, M.; Tsuruya, K.; Lopes, M.; Bieber, B.; McCullough, K.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Robinson, B.; Pisoni, R.; Kanda, E.; Iseki, K.; et al. Routinely Measured Cardiac Troponin I and N-Terminal pro-B-Type Natriuretic Peptide as Predictors of Mortality in Haemodialysis Patients. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 1138–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komaba, H.; Fuller, D.S.; Taniguchi, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Nomura, T.; Zhao, J.; Bieber, B.A.; Robinson, B.M.; Pisoni, R.L.; Fukagawa, M. Fibroblast Growth Factor 23 and Mortality Among Prevalent Hemodialysis Patients in the Japan Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int. Rep. 2020, 5, 1956–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breha, A.; Delcea, C.; Ivanescu, A.C.; Dan, G.A. NT-ProBNP as an Independent Predictor of Long-Term All-Cause Mortality in Heart Failure Across the Spectrum of Glomerular Filtration Rate. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breidthardt, T.; Kalbermatter, S.; Socrates, T.; Noveanu, M.; Klima, T.; Mebazaa, A.; Mueller, C.; Kiss, D. Increasing B-Type Natriuretic Peptide Levels Predict Mortality in Unselected Haemodialysis Patients. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2011, 13, 860–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoccali, C.; Mallamaci, F.; Benedetto, F.A.; Tripepi, G.; Parlongo, S.; Cataliotti, A.; Cutrupi, S.; Giacone, G.; Bellanuova, I.; Cottini, E.; et al. Cardiac Natriuretic Peptides Are Related to Left Ventricular Mass and Function and Predict Mortality in Dialysis Patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2001, 12, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, T.G.; Shukalek, C.B.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Zarnke, K.B.; Ronksley, P.E.; Iragorri, N.; Graham, M.M.; James, M.T. Association of NT-ProBNP and BNP with Future Clinical Outcomes in Patients with ESKD: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2020, 76, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noppakun, K.; Ratnachina, K.; Osataphan, N.; Phrommintikul, A.; Wongcharoen, W. Prognostic Values of High Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin T and I for Long-Term Mortality in Hemodialysis Patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snaedal, S.; Bárány, P.; Lund, S.H.; Qureshi, A.R.; Heimbürger, O.; Stenvinkel, P.; Löwbeer, C.; Szummer, K. High-Sensitivity Troponins in Dialysis Patients: Variation and Prognostic Value. Clin. Kidney J. 2020, 14, 1789–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, C.W.; Burton, J.O.; Selby, N.M.; Leccisotti, L.; Korsheed, S.; Baker, C.S.R.; Camici, P.G. Hemodialysis-Induced Cardiac Dysfunction Is Associated with an Acute Reduction in Global and Segmental Myocardial Blood Flow. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamei, K.; Yamada, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Konta, T.; Hamano, T.; Fukagawa, M. The Impact of Low and High Dialysate Calcium Concentrations on Cardiovascular Disease and Death in Patients Undergoing Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2024, 28, 557–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrelli, D.; Sharma, A.; Alexiuk, J.; Tays, Q.; Rossum, K.; Sharma, M.; Ford, E.; Iansavitchene, A.; Al-Jaishi, A.A.; Whitlock, R.; et al. Effect of Intradialytic Exercise on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Maintenance Hemodialysis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Kidney360 2024, 5, 390–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisavu, L.; Mihaescu, A.; Bob, F.; Motofelea, A.; Schiller, O.; Marc, L.; Dragota-Pascota, R.; Chisavu, F.; Schiller, A. Trends in Mortality and Comorbidities in Hemodialysis Patients between 2012 and 2017 in an East-European Country: A Retrospective Study. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2023, 55, 2579–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

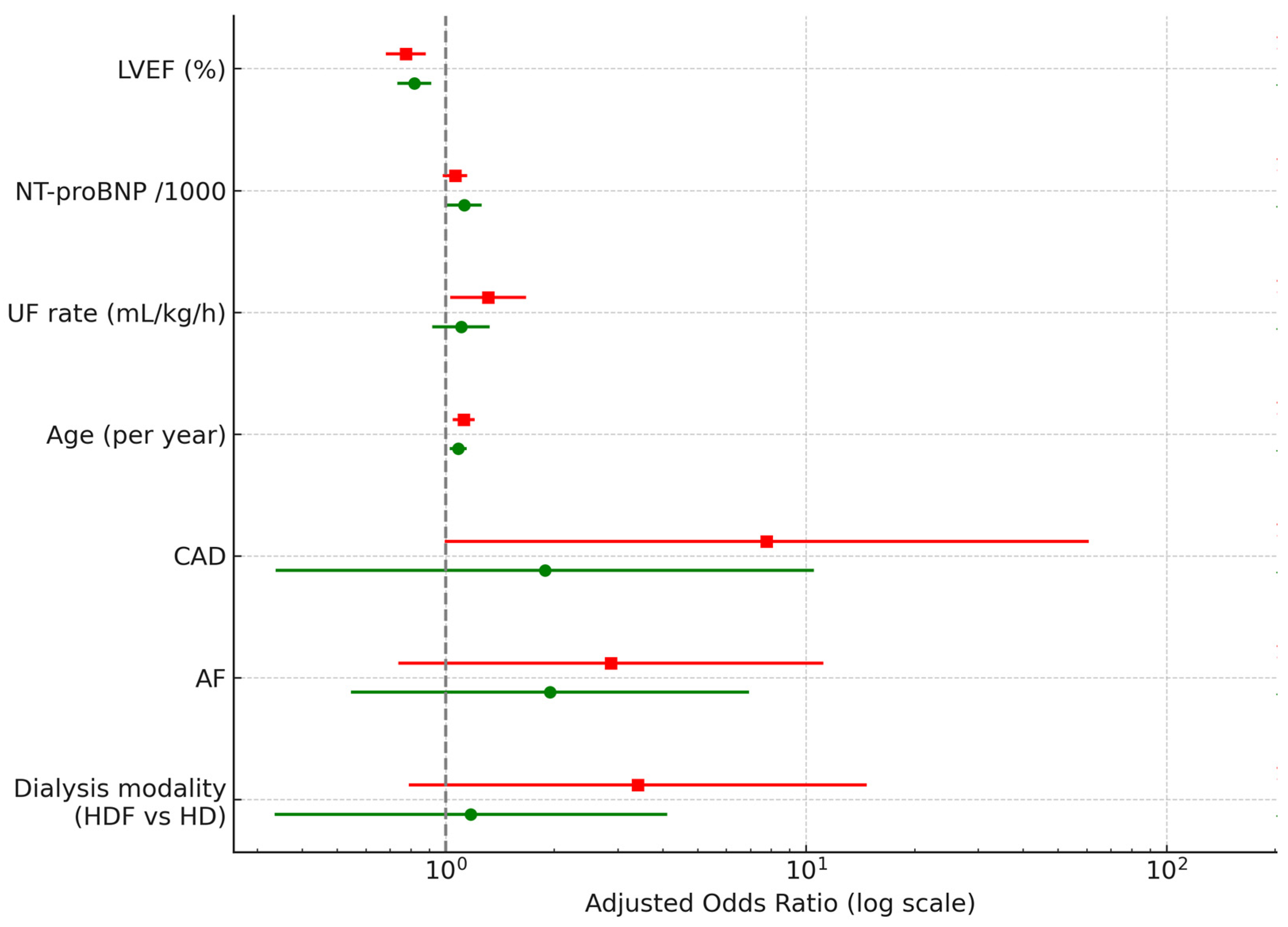

= NT-pro-BNP > 10,000;

= NT-pro-BNP > 10,000;  = NT-pro-BNP > 7000, CAD—coronary artery disease, LVEF—left ventricular ejection fraction, UF—ultrafiltration, AF—atrial fibrillation, HDF—hemodiafiltration, HD—hemodialysis. Green circles (7k) and red squares (10k) show estimates from models using NT-proBNP > 7000 pg/mL and >10,000 pg/mL, respectively. Numerical values for OR, 95% CI and p-value are displayed to the right of each predictor.

= NT-pro-BNP > 7000, CAD—coronary artery disease, LVEF—left ventricular ejection fraction, UF—ultrafiltration, AF—atrial fibrillation, HDF—hemodiafiltration, HD—hemodialysis. Green circles (7k) and red squares (10k) show estimates from models using NT-proBNP > 7000 pg/mL and >10,000 pg/mL, respectively. Numerical values for OR, 95% CI and p-value are displayed to the right of each predictor.

= NT-pro-BNP > 10,000;

= NT-pro-BNP > 10,000;  = NT-pro-BNP > 7000, CAD—coronary artery disease, LVEF—left ventricular ejection fraction, UF—ultrafiltration, AF—atrial fibrillation, HDF—hemodiafiltration, HD—hemodialysis. Green circles (7k) and red squares (10k) show estimates from models using NT-proBNP > 7000 pg/mL and >10,000 pg/mL, respectively. Numerical values for OR, 95% CI and p-value are displayed to the right of each predictor.

= NT-pro-BNP > 7000, CAD—coronary artery disease, LVEF—left ventricular ejection fraction, UF—ultrafiltration, AF—atrial fibrillation, HDF—hemodiafiltration, HD—hemodialysis. Green circles (7k) and red squares (10k) show estimates from models using NT-proBNP > 7000 pg/mL and >10,000 pg/mL, respectively. Numerical values for OR, 95% CI and p-value are displayed to the right of each predictor.

| Parameter | Entire Cohort 271 | Heart Failure 202 (74.5%) | No Heart Failure 69 (25.5%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD vintage (years) | 7.10 ± 5.42 | 7.11 ± 5.33 | 7.09 ± 5.68 | 0.97 |

| Age (years) | 64.61 ± 13.61 | 68.68 ± 10.51 | 52.68 ± 14.68 | <0.001 |

| Sex M | 146/271 (51.6%) | 108/202 (53.47%) | 38/69 (55.07%) | 0.81 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.27 ± 6.22 | 26.38 ± 6.24 | 26.35 ± 5.62 | 0.97 |

| HDF | 71/271 (26.2%) | 39/202 (19.31%) | 32/69 (46.38%) | <0.001 |

| AV fistula | 196/271 (72.32%) | 138/202 (68.32%) | 58/69 (84.06%) | 0.012 |

| Hypertension | 255/271 (90.1%) | 190/202 (94.06%) | 65/67 (97.01%) | 0.49 |

| Diabetes | 88/271 (31.1%) | 79/202 (39.11%) | 9/69 (13.04%) | <0.001 |

| CAD | 93/271 (32.9%) | 90/202 (44.55%) | 3/69 (4.35%) | <0.001 |

| MI | 57/271 (21%) | 53/202 (26.24%) | 4/69 (5.80%) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 33/271 (12.2%) | 32/202 (15.84%) | 1/69 (1.45%) | 0.002 |

| Aortic stenosis | 37/271 (1.7%) | 32/202 (15.84%) | 5/69 (7.25%) | 0.07 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 51/271 (18.8%) | 39/202 (19/31%) | 12/69 (17.39%) | 0.72 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 103/271 (38%) | 80/202 (39.60%) | 23/69 (33.33%) | 0.35 |

| T-Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 156.21 ± 43.83 | 152.541 ± 43.76 | 166.477 ± 42.67 | 0.88 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 106.75 ± 39.06 | 105.178 ± 39.33 | 110.394 ± 38.72 | 0.50 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 37.64 ± 12.37 | 35.169 ± 8.39 | 43.222 ± 17.41 | 0.004 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 153.67 ± 96.71 | 160.41 ± 106.691 | 136.84 ± 63.25 | 0.14 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 10.84 ± 3.11 | 10.85 ± 3.44 | 10.80 ± 1.85 | 0.908 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.49 ± 11.19 | 9.70 ± 12.90 | 8.83 ± 0.89 | 0.59 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 4.98 ± 1.78 | 4.83 ± 1.66 | 5.45 ± 2.03 | 0.017 |

| Kt/V | 1.59 ± 0.31 | 1.60 ± 0.32 | 1.57 ± 0.30 | 0.46 |

| hs-troponin (pg/mL) | 1829.88 ± 7464.62 | 1981.538 ± 7758.161 | 10.03 ± 2.51 | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 14,948.19 ± 14,293.15 | 20,684.35 ± 13,279.28 | 2570.18 ± 6373.59 | <0.001 |

| Paroxysmal AF | 100/271 (36.9%) | 85/202 (42.08%) | 15/69 (21.74%) | 0.002 |

| Permanent AF | 44/271 (16.2%) | 41/202 (20.30%) | 3/69 (4.35%) | 0.002 |

| LVEF (%) | 50.86 ± 10.76 | 47.07 ± 9.44 | 61.97 ± 5.34 | <0.001 |

| Preserved EF | 161/271 (59.40%) | 92/202 (45.54%) | 69/69 (100%) | <0.001 |

| Mildly reduced EF | 62/271 (22.88%) | 62/202 (30.69%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Reduced EF | 48/271 (17.71%) | 48/202 (23.76%) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Weight gain (kg) | 2.80 ± 1.35 | 2.96 ± 1.31 | 2.31 ± 1.35 | 0.001 |

| UF rate (mL/kg/h) | 7.10 ± 3.08 | 7.44 ± 2.98 | 6.11 ± 3.16 | 0.002 |

| UF mean volume (mL) | 2990.77 ± 682.09 | 3037.62 ± 632.432 | 2853.62 ± 833.063 | 0.056 |

| Parameter | NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LVEF% | >10,000 | 0.77 | 0.68–0.88 | <0.001 |

| >7000 | 0.82 | 0.73–0.91 | <0.001 | |

| NT-proBNP/1000 | >10,000 | 1.06 | 0.98–1.15 | 0.141 |

| >7000 | 1.12 | 1.01–1.26 | 0.038 | |

| UF rate(mL/kg/h) | >10,000 | 1.31 | 1.03–1.67 | 0.028 |

| >7000 | 1.10 | 0.92–1.32 | 0.293 | |

| Age(year) | >10,000 | 1.12 | 1.05–1.2 | 0.001 |

| >7000 | 1.08 | 1.02–1.14 | 0.004 | |

| CAD | >10,000 | 7.77 | 0.99–60.93 | 0.051 |

| >7000 | 1.88 | 0.34–10.52 | 0.471 | |

| AF | >10,000 | 2.87 | 0.74–11.15 | 0.128 |

| >7000 | 1.95 | 0.55–6.94 | 0.305 | |

| Dialysis modality (HDF vs HD) | >10,000 | 3.41 | 0.79–14.71 | 0.101 |

| >7000 | 1.17 | 0.34–4.12 | 0.801 |

| Parameter | Entire Cohort 271 | Deceased 107 (39.5%) | Survivors 164 (60.52%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD vintage (years) | 7.10 ± 5.42 | 8.41 ± 5.94 | 6.25 ± 4.86 | 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 64.61 ± 13.61 | 68.64 ± 11.98 | 61.98 ± 13.99 | <0.001 |

| Sex (M) | 146/271 (51.6%) | 58/107 (54.21%) | 88/164 (53.66%) | 0.93 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.27 ± 6.22 | 24.803 ± 6.36 | 27.395 ± 5.69 | 0.001 |

| HDF | 71/271 (26.2%) | 22/107 (20.56%) | 49/164 (29.88%) | 0.08 |

| AV fistula | 196/271 (72.32%) | 71/107 (66.36%) | 125/164 (76.22%) | 0.07 |

| Hypertension | 255/271 (90.1%) | 100/107 (93.46%) | 155/164 (94.51%) | 0.18 |

| Diabetes | 88/271 (31.1%) | 37/107 (34.58%) | 51/164 (31.10%) | 0.55 |

| CAD | 93/271 (32.9%) | 53/107 (49.53%) | 40/164 (24.39%) | <0.001 |

| MI | 57/271 (21%) | 48/107 (44.86%) | 9/164 (5.49%) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 33/271 (12.2%) | 18/107 (16.82%) | 15/164 (9.15%) | 0.05 |

| Aortic stenosis | 37/271 (1.7%) | 11/107 (10.28) | 26/164 (15.85%) | 0.19 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 51/271 (18.8%) | 12/107 (11.21%) | 39/164 (23.78%) | 0.01 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 103/271 (38%) | 31/107 (28.97%) | 72/164 (43.90%) | 0.01 |

| T-Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 156.21 ± 43.83 | 149.568 ± 47.92 | 160.288 ± 40.74 | 0.06 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 106.75 ± 39.06 | 112.850 ± 41.54 | 13.671 ± 27.63 | 0.22 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 37.64 ± 12.37 | 36.68 ± 10.07 | 38.19 ± 13.51 | 0.59 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 153.67 ± 96.71 | 148.15 78.90 | 156.63 ± 105.213 | 0.58 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 10.84 ± 3.11 | 10.76 ± 4.61 | 10.88 ± 1.48 | 0.75 |

| Ca (mg/dL) | 9.49 ± 11.19 | 10.42 ± 17.35 | 8.82 ± 0.97 | 0.25 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 4.98 ± 1.78 | 5.09 ± 1.96 | 4.90 ± 1.64 | 0.40 |

| Kt/V | 1.59 ± 0.31 | 1.55 ± 0.35 | 1.62 ± 0.28 | 0.07 |

| hs-troponin (pg/mL) | 1829.88 ± 7464.62 | 1607.57 ± 5528.749 | 2020.44 ± 8933.33 | 0.86 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 14,948.19 ± 14,293.15 | 25,123.79 ± 13,184.16 | 10,232.67 ± 12,213.15 | <0.001 |

| Paroxysmal AF | 100/271 (36.9%) | 55/107 (51.40%) | 45/164 (27.44%) | <0.001 |

| Permanent AF | 44/271 (16.2%) | 18/107 (16.82%) | 28/164 (17.07%) | 0.83 |

| HF | 202/271 (74.54%) | 98/107 (91.59%) | 104/164 (63.41%) | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 50.86 ± 10.76 | 45.42 ± 9.98 | 54.41 ± 9.74 | <0.001 |

| Preserved EF | 161/271 (59.40%) | 37/107 (34.58%) | 124/164 (75.61%) | <0.001 |

| Mildly reduced EF | 62/271 (22.88%) | 37/107 (34.58%) | 25/164 (15.24%) | <0.001 |

| Reduced EF | 48/271 (17.71%) | 33/107 (30.84%) | 15/164 (9.15%) | <0.001 |

| Weight gain (kg) | 2.80 ± 1.35 | 3.26 ± 1.25 | 2.50 ± 1.33 | <0.001 |

| UF rate (mL/kg/h) | 7.10 ± 3.08 | 8.18 ± 2.58 | 6.39 ± 3.18 | <0.001 |

| UF mean volume (mL) | 2990.77 ± 682.09 | 3005.61 ± 617.639 | 2981.10 ± 738.309 | 0.77 |

| B-Blockers | 218/271 (80.44%) | 87/107 (81.31%) | 131/164 (79.88%) | 0.77 |

| RAAs antagonists | 157/271 (57.93%) | 55/107 (51.40%) | 102/164 (65.20%) | 0.07 |

| Statins | 135/271 (49.82%) | 55/107 (51.40%) | 80/164 (48.78%) | 0.71 |

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 1.014 | 0.987–1.042 | 0.288 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.946 | 0.878–1.019 | 0.141 |

| CAD (yes/no) | 1.164 | 0.691–1.960 | 0.568 |

| AF (yes/no) | 1.151 | 0.606–2.186 | 0.665 |

| LVEF (%) | 0.962 | 0.931–0.994 | 0.019 |

| NT-proBNP (per 1000 pg/mL) | 1.030 | 1.003–1.057 | 0.029 |

| UF rate (mL/kg/h) | 1.056 | 0.924–1.206 | 0.431 |

| HD vintage (years) | 1.012 | 0.933–1.097 | 0.764 |

| Dialysis modality | 0.810 | 0.510–1.287 | 0.372 |

| Parameter | Cardiac Death 63 (23.2%) | Survivors 164 (60.52%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| HD vintage (years) | 9.06 ± 6.045 | 6.25 ± 4.86 | <0.001 |

| Age (years) | 69.06 ± 11.87 | 61.98 ± 13.99 | <0.001 |

| Sex M | 35 (55.6%) | 88/164 (53.66%) | 0.79 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.46 ± 6.45 | 27.395 ± 5.69 | 0.001 |

| HDF | 15/63 (23.8%) | 49/164 (29.88%) | 0.36 |

| AV fistula | 43/63 (68.3%) | 125/164 (76.22%) | 0.22 |

| Hypertension | 60/63 (95.2%) | 155/164 (94.51%) | 0.55 |

| Diabetes | 22/63 (34.9%) | 51/164 (31.10%) | 0.58 |

| CAD | 39/63 (61.9%) | 40/164 (24.39%) | <0.001 |

| MI | 37/63 (58.7%) | 9/164 (5.49%) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 16/63 (25.4%) | 15/164 (9.15%) | 0.001 |

| Aortic stenosis | 10/63 (15.9%) | 26/164 (15.85%) | 0.99 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 9/63 (14.3%) | 39/164 (23.78%) | 0.11 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 22/63 (34.9%) | 72/164 (43.90%) | 0.22 |

| T cholesterol (mg/dL) | 149.662 ± 40.21 | 160.288 ± 40.74 | 0.09 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 111.83 ± 37.19 | 103.671 ± 27.63 | 0.35 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 36.40 ± 8.15 | 38.19 ± 13.51 | 0.58 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 151 ± 69.77 | 156.63 ± 105.213 | 0.77 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 10.40 ± 1.60 | 10.88 ± 1.48 | 0.03 |

| Ca (mg/dL) | 8.84 ± 0.75 | 8.82 ± 0.97 | 0.88 |

| Phosphate (mg/dL) | 5.11 ± 1.98 | 4.90 ± 1.64 | 0.42 |

| Kt/V | 1.52 ± 0.36 | 1.62 ± 0.28 | 0.024 |

| hs-troponin (pg/mL) | 1924.78 ± 6039.06 | 2020.44 ± 8933.33 | 0.97 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 28,741.56 ± 10,058.72 | 10,232.67 ± 12,213.15 | <0.001 |

| Paroxysmal AF | 34/63 (54%) | 45/164 (27.44%) | <0.001 |

| Permanent AF | 12/63 (19%) | 28/164 (17.07%) | 0.56 |

| HF | 62/63(98.4%) | 104/164 (63.41%) | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 42.66 ± 9.48 | 54.41 ± 9.74 | <0.001 |

| Preserved EF | 16/63 (25.4%) | 124/164 (75.61%) | <0.001 |

| Mildly reduced EF | 20/63 (31.6%) | 25/164 (15.24%) | 0.005 |

| Reduced EF | 27/63 (42.9%) | 15/164 (9.15%) | <0.001 |

| Weight gain (kg) | 3.34 ± 1.30 | 2.50 ± 1.33 | <0.001 |

| UF rate (mL/kg/h) | 7.95 ± 2.48 | 6.39 ± 3.18 | 0.001 |

| UF mean volume (mL) | 3041.27 ± 649.971 | 2981.10 ± 738.309 | 0.571 |

| B-Blockers | 53/63 (84.1%) | 131/164 (79.88%) | 0.46 |

| RAAs antagonists | 31/63 (49.2%) | 102/164 (65.20%) | 0.07 |

| Statins | 34/63 (54%) | 80/164 (48.78%) | 0.48 |

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 0.994 | 0.964–1.025 | 0.697 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.929 | 0.870–0.992 | 0.028 |

| LVEF (%) | 0.933 | 0.894–0.973 | 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (per 1000 pg/mL) | 1.038 | 1.004–1.077 | 0.033 |

| AF (yes/no) | 2.318 | 0.957–5.616 | 0.063 |

| UF rate | 0.74 | 0.54–1.00 | 0.051 |

| Parameter | Entire Cohort 271 | Hospitalization for Heart Failure 191 (70.5%) | No Hospitalization for HF 80 (29.5%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD vintage (years) | 7.10 ± 5.42 | 7.01 ± 4.92 | 7.33 ± 6.46 | 0.664 |

| Age (years) | 64.61 ± 13.61 | 66.37 ± 11.55 | 60.40 ± 16.93 | 0.001 |

| Sex M | 146/271 (51.6%) | 101/191 (52.88%) | 45/80 (56.25%) | 0.61 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.27 ± 6.22 | 26.59 ± 6.35 | 25.85 ± 5.37 | 0.36 |

| HDF | 71/271 (26.2%) | 44/191 (23.03%) | 27/80 (33.75%) | 0.068 |

| AV fistula | 196 (72.32%) | 134/191 (70.16%) | 62/80 (77.5%) | 0.219 |

| Hypertension | 255/271 (90.1%) | 182/191 (95.29%) | 73/80 (91.25%) | 0.114 |

| Diabetes | 88/271 (31.1%) | 68/191 (35.60%) | 20/80 (25%) | 0.09 |

| CAD | 93/271 (32.9%) | 84/191 (43.98%) | 9/80 (11.25%) | <0.001 |

| MI | 57/271 (21%) | 50/191 (26.18%) | 7/80 (8.75%) | 0.001 |

| PCI | 33/271 (12.2%) | 31/191 (16.23%) | 2/80 (2.5%) | 0.002 |

| Aortic stenosis | 37/271 (1.7%) | 30/191 (15.71%) | 7/80 (8.75%) | 0.12 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 51/271 (18.8%) | 39/191 (20.42%) | 12/80 (15%) | 0.300 |

| Mitral regurgitation | 103/271 (38%) | 81/191 (42.41%) | 22/80 (27.5%) | 0.021 |

| T-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 156.21 ± 43.83 | 151.994 ± 42.27 | 165.170 ± 45.95 | 0.027 |

| LDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 106.75 ± 39.06 | 104.122 ± 38.72 | 112.59 ± 39.70 | 0.27 |

| HDL-cholesterol (mg/dL) | 37.64 ± 1 2.37 | 36.65 ± 10.24 | 40.00 ± 16.40 | 0.24 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 153.67 ± 96.71 | 153.53 ± 102.161 | 154.00 ± 84.47 | 0.97 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 10.84 ± 3.11 | 10.56 ± 1.68 | 11.51 ± 5.10 | 0.02 |

| Ca (mg/dL) | 9.49 ± 11.19 | 8.72 ± 0.92 | 11.38 ± 20.83 | 0.08 |

| Phos (mg/dL) | 4.98 ± 1.78 | 4.96 ± 1.62 | 5.04 ± 2.11 | 0.72 |

| Kt/V | 1.59 ± 0.31 | 1.58 ± 0.31 | 1.62 ± 0.31 | 0.304 |

| hs-troponin (pg/mL) | 1829.88 ± 7464.62 | 1980.15 ± 7758.52 | 26.73 ± 18.26 | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 14,948.19 ± 14,293.15 | 18,879.84 ± 13,949.42 | 5003.45 ± 9616.372 | <0.001 |

| Paroxysmal AF | 100/271 (36.9%) | 86/191 (45.02%) | 14/80 (17.5%) | <0.001 |

| Permanent AF | 44/271 (16.2%) | 42/191 (21.99%) | 2/80 (2.5%) | <0.001 |

| HF | 202/271 (74.54%) | 164/191 (85.86%) | 38/80 (47.5%) | <0.001 |

| LVEF (%) | 50.86 ± 10.76 | 48.36 ± 10.60 | 56.84 ± 8.50 | <0.001 |

| Preserved EF | 161/271 (59.40%) | 94/191 (49.21%) | 67/80 (83.75%) | <0.001 |

| Mildly reduced EF | 62/271(22.88%) | 52/191 (27.23%) | 10/80 (12.15%) | 0.008 |

| Reduced EF | 48/271(17.71%) | 45/191 (23.56%) | 3/80 (3.75%) | <0.001 |

| Weight gain (kg) | 2.80 ± 1.35 | 2.96 ± 1.33 | 2.39 ± 1.33 | 0.001 |

| UF rate (mL/min/kg) | 7.10 ± 3.08 | 7.36 ± 3.02 | 6.46 ± 3.14 | 0.029 |

| UF mean volume (mL) | 2990.77 ± 682.09 | 3073.30 ± 611.959 | 2793.75 ± 824.981 | 0.002 |

| B-Blockers | 218/271 (80.44%) | 155/191 (81.15%) | 63/80 (78.75%) | 0.65 |

| SRAA antagonists | 157/271 (57.93%) | 107/191 (56.02%) | 50/80 (62.5%) | 0.32 |

| Statins | 135/271 (49.82%) | 107/191 (56.02%) | 28/80 (35%) | 0.002 |

| Variable | OR | 95%CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 1.001 | 0.961–1.042 | 0.974 |

| CAD | 1.15 | 0.671–1.830 | 0.55 |

| LVEF (%) | 0.95 | 0.91–1.00 | 0.064 |

| NT-proBNP (per 1000 pg/mL) | 1.07 | 1.02–1.11 | 0.005 |

| AF (yes/no) | 1.506 | 0.562–4.032 | 0.415 |

| UF rate | 0.948 | 0.804–1.119 | 0.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ratiu, I.A.; Babes, V.V.; Hocopan, O.; Ratiu, C.A.; Croitoru, C.A.; Moisa, C.; Blaj-Tunduc, I.P.; Marian, A.M.; Babeș, E.E. The Burden of Heart Failure in End-Stage Renal Disease: Insights from a Retrospective Cohort of Hemodialysis Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8556. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238556

Ratiu IA, Babes VV, Hocopan O, Ratiu CA, Croitoru CA, Moisa C, Blaj-Tunduc IP, Marian AM, Babeș EE. The Burden of Heart Failure in End-Stage Renal Disease: Insights from a Retrospective Cohort of Hemodialysis Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8556. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238556

Chicago/Turabian StyleRatiu, Ioana Adela, Victor Vlad Babes, Ozana Hocopan, Cristian Adrian Ratiu, Camelia Anca Croitoru, Corina Moisa, Ioana Paula Blaj-Tunduc, Ana Marina Marian, and Elena Emilia Babeș. 2025. "The Burden of Heart Failure in End-Stage Renal Disease: Insights from a Retrospective Cohort of Hemodialysis Patients" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8556. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238556

APA StyleRatiu, I. A., Babes, V. V., Hocopan, O., Ratiu, C. A., Croitoru, C. A., Moisa, C., Blaj-Tunduc, I. P., Marian, A. M., & Babeș, E. E. (2025). The Burden of Heart Failure in End-Stage Renal Disease: Insights from a Retrospective Cohort of Hemodialysis Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8556. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238556