Inhaled Corticosteroid Use and Risk of Haemophilus influenzae Isolation in Patients with Bronchiectasis: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

- The Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR), which includes all hospital admissions since 1977 and outpatient data since 1995, was applied to identify comorbidities in the study population [23].

- The Danish National Database of Reimbursed Prescriptions (DNDRP), used to identify prescriptions redeemed for inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs) and other medications at Danish community and hospital-based outpatient pharmacies since 1995 [24].

- Microbiological data from the Clinical Microbiology Departments in Eastern Denmark (Region Zealand and Capital Region), consisting of approximately 2.6 million inhabitants, used to identify patients with H. influenzae.

- The Danish register of Causes of Death, which provided mortality data [25].

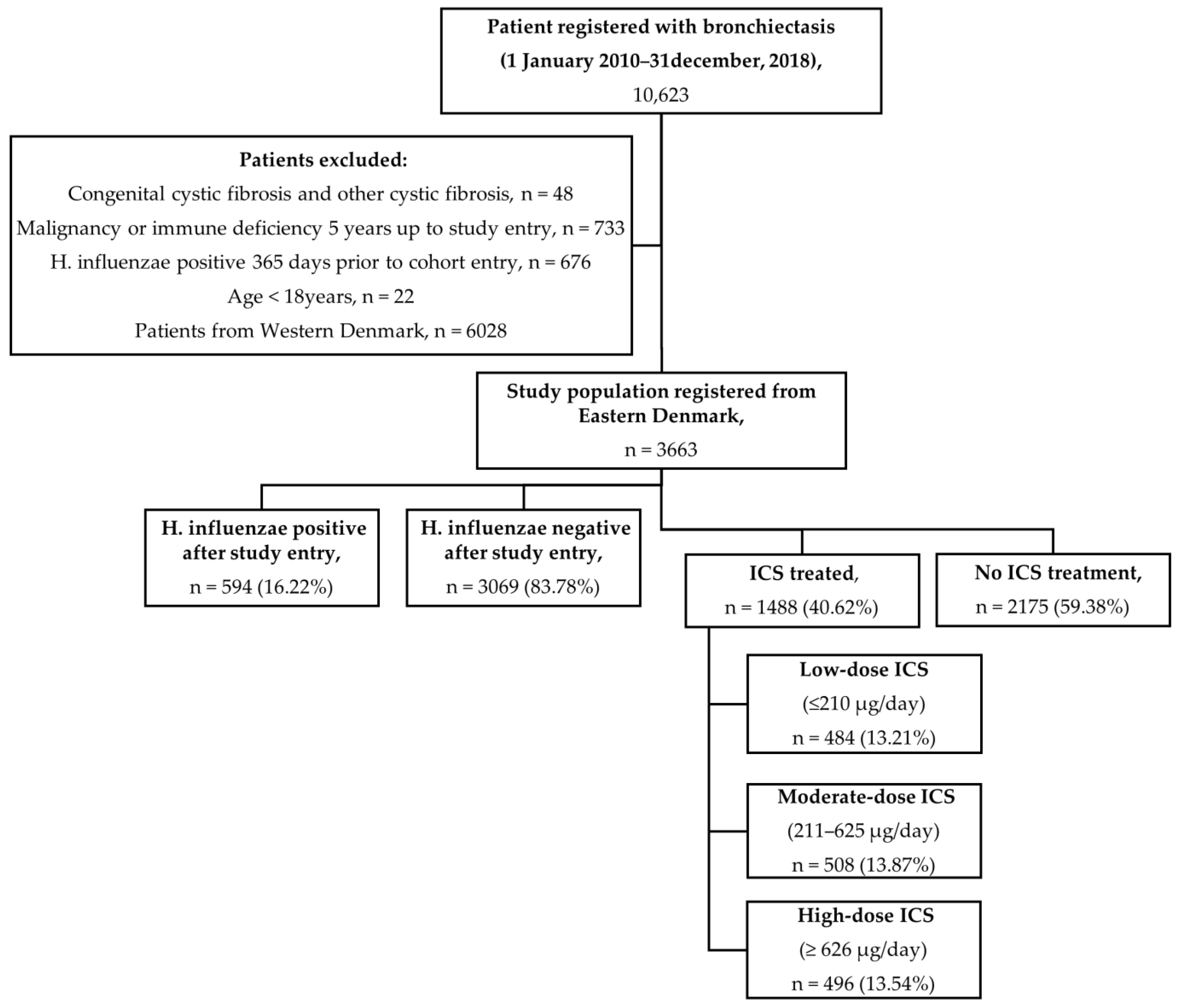

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Exposure to ICSs

2.4. Outcome and Follow-Up

2.5. Statistical Analysis

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

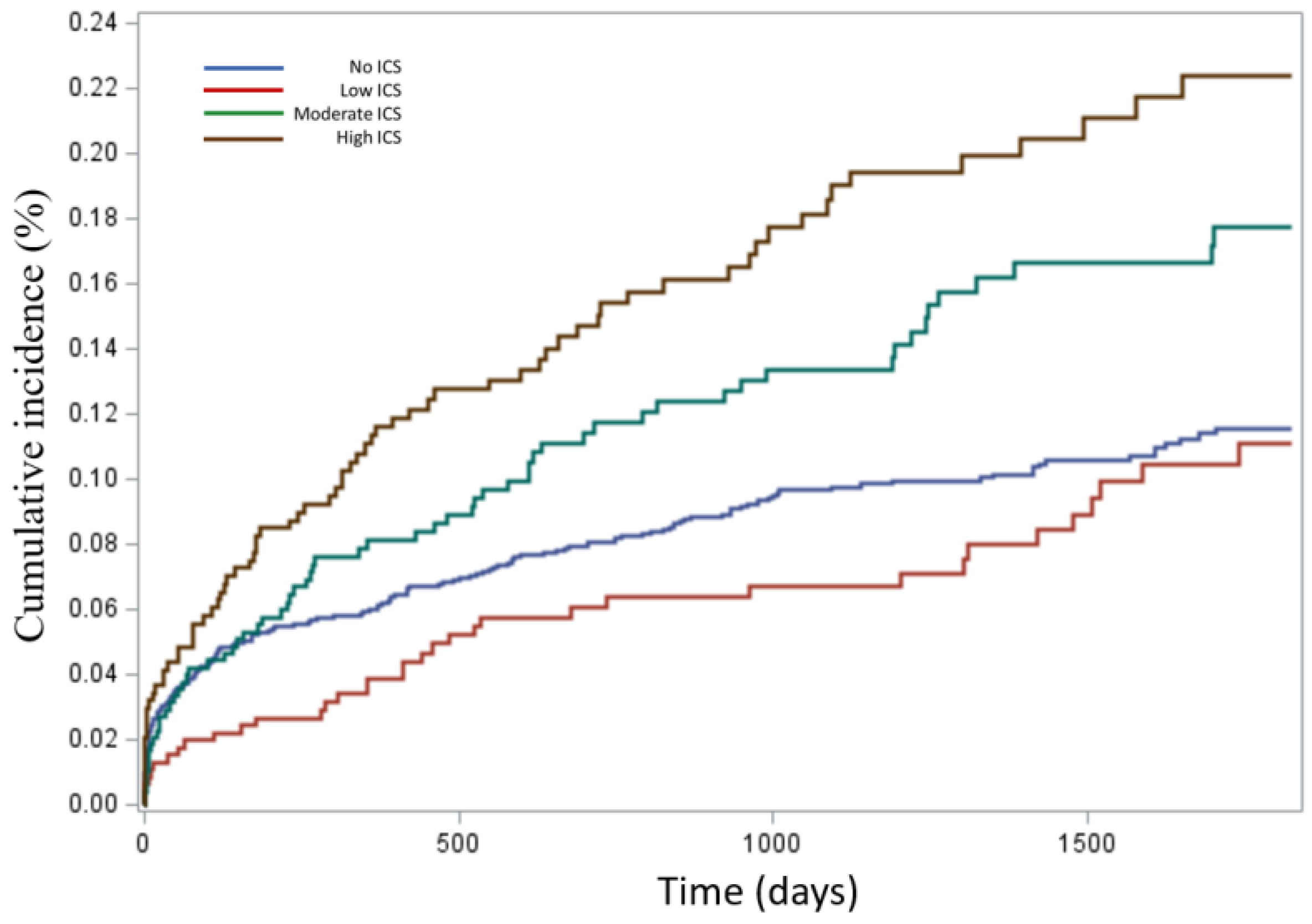

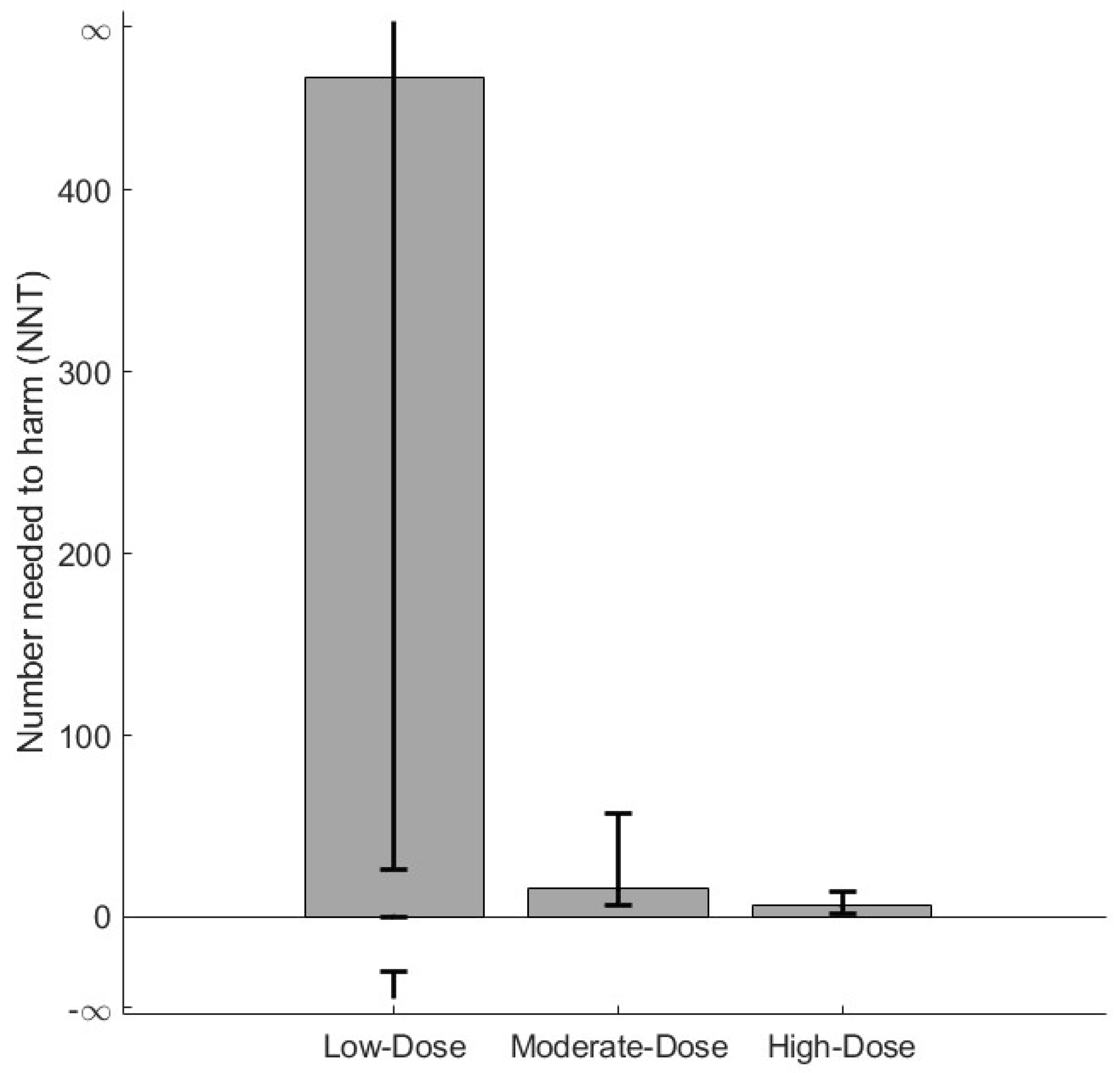

3.1. Outcome Results

3.2. Sensitivity Analyses

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATC-code | Anatomical therapeutic chemical code |

| BE | Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CRS | Danish Civil Registration System |

| DNDRP | Danish Database of Reimbursed Prescriptions |

| DNPR | Danish National Patient Register |

| H. influenzae | Haemophilus influenzae |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| ICD-10 | International classifications of disease 10th revision |

| ICSs | Inhaled corticosteroids |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| IPTW | Inverse probability-of-treatment weighting |

| LABA | Long-acting β2-agonist |

| LAMA | Long-acting muscarinic antagonist |

| OCSs | Oral corticosteroids |

References

- Barker, A.F. Bronchiectasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 1383–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, S.; Goeminne, P.C.; O’Donnell, A.E.; Aksamit, T.R.; Al-Jahdali, H.; Barker, A.F.; Blasi, F.; Boersma, W.G.; Crichton, M.L.; De Soyza, A.; et al. Criteria and definitions for the radiological and clinical diagnosis of bronchiectasis in adults for use in clinical trials: International consensus recommendations. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 298–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; McShane, P.J.; Aliberti, S.; Chalmers, J.D. Bronchiectasis management in adults: State of the art and future directions. Eur. Respir. J. 2024, 63, 2400518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keistinen, T.; Saynajakangas, O.; Tuuponen, T.; Kivela, S. Bronchiectasis: An orphan disease with a poorly-understood prognosis. Eur. Respir. J. 1997, 10, 2784–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, G.; Li, J. Prevalence of bronchiectasis in adults: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, J.S.; Duarte, A.G. Non-CF bronchiectasis: Orphan disease no longer. Respir. Med. 2020, 166, 105940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.F.; Karamooz, E. Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2025, 334, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crimi, C.; Ferri, S.; Campisi, R.; Crimi, N. The Link between Asthma and Bronchiectasis: State of the Art. Respiration 2020, 99, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Garcia, M.A.; Miravitlles, M. Bronchiectasis in COPD patients: More than a comorbidity? Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017, 12, 1401–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, P.J. Inflammation: A two-edged sword--the model of bronchiectasis. Eur. J. Respir. Dis. Suppl. 1986, 147, 6–15. [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson, K.E.J.; Fjaellegaard, K.; Browatzki, A.; Dönmez Sin, M.; Ulrik, C.S. Inhaled Corticosteroid Therapy in Bronchiectasis is Associated with All-Cause Mortality: A Prospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021, 16, 2119–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Mall, M.A.; McShane, P.J.; Nielsen, K.G.; Shteinberg, M.; Sullivan, S.D.; Chotirmall, S.H. A systematic literature review of the clinical and socioeconomic burden of bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2024, 33, 240049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, N.; Petsky, H.L.; Bell, S.; Kolbe, J.; Chang, A.B. Inhaled corticosteroids for bronchiectasis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 5, Cd000996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, M.Á.; Oscullo, G.; García-Ortega, A.; Matera, M.G.; Rogliani, P.; Cazzola, M. Inhaled Corticosteroids in Adults with Non-cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis: From Bench to Bedside. A Narrative Review. Drugs 2022, 82, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polverino, E.; Goeminne, P.C.; McDonnell, M.J.; Aliberti, S.; Marshall, S.E.; Loebinger, M.R.; Murris, M.; Cantón, R.; Torres, A.; Dimakou, K.; et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalmers, J.D.; Haworth, C.S.; Flume, P.; Long, M.B.; Burgel, P.R.; Dimakou, K.; Blasi, F.; Herrero-Cortina, B.; Dhar, R.; Chotirmall, S.H.; et al. European Respiratory Society Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adult Bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. J. 2025, 2501126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roland, N.J.; Bhalla, R.K.; Earis, J. The local side effects of inhaled corticosteroids: Current understanding and review of the literature. Chest 2004, 126, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C.; Goldmann, T.; Rohmann, K.; Rupp, J.; Marwitz, S.; Rotta Detto Loria, J.; Limmer, S.; Zabel, P.; Dalhoff, K.; Drömann, D. Budesonide Inhibits Intracellular Infection with Non-Typeable Haemophilus influenzae Despite Its Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Respiratory Cells and Human Lung Tissue: A Role for p38 MAP Kinase. Respiration 2015, 90, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, R.U.; Heerfordt, C.K.; Eklöf, J.; Sivapalan, P.; Saeed, M.I.; Ingebrigtsen, T.S.; Nielsen, S.D.; Harboe, Z.B.; Iversen, K.K.; Bangsborg, J.; et al. Use of Inhaled Corticosteroids and Risk of Acquiring Haemophilus influenzae in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziparasidis, G.; Kantar, A.; Grimwood, K. Pathogenesis of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae infections in chronic suppurative lung disease. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023, 58, 1849–1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, A.; Marchello, M.; Tramontano, A.; Cicchetti, M.; Nigro, M.; Simonetta, E.; Scarano, P.; Polelli, V.; Artuso, V.A.; Aliberti, S. Haemophilus influenzae in bronchiectasis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2025, 34, 250007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.-H.; Song, M.J.; Kim, Y.W.; Kwon, B.S.; Lim, S.Y.; Lee, Y.-J.; Park, J.S.; Cho, Y.-J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, C.-T.; et al. Understanding the effects of Haemophilus influenzae colonization on bronchiectasis: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynge, E.; Sandegaard, J.L.; Rebolj, M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39 (Suppl. 7), 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Schmidt, S.A.J.; Adelborg, K.; Sundbøll, J.; Laugesen, K.; Ehrenstein, V.; Sørensen, H.T. The Danish health care system and epidemiological research: From health care contacts to database records. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 11, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helweg-Larsen, K. The Danish Register of Causes of Death. Scand. J. Public Health 2011, 39 (Suppl. 7), 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronn, C.; Sivapalan, P.; Eklof, J.; Kamstrup, P.; Biering-Sorensen, T.; Bonnesen, B.; Harboe, Z.B.; Browatzki, A.; Kjærgaard, J.L.; Meyer, C.N.; et al. Hospitalization for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumonia: Association with the dose of inhaled corticosteroids. A nation-wide cohort study of 52 100 outpatients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipsen, A.A.; Frost, K.H.; Eklöf, J.; Tønnesen, L.L.; Vognsen, A.K.; Boel, J.B.; Pinholt, M.; Andersen, C.Ø.; Dessau, R.B.C.; Biering-Sørensen, T.; et al. Inhaled Corticosteroids and Risk of Staphylococcus aureus Isolation in Bronchiectasis: A Register-Based Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rønn, C.; Kamstrup, P.; Heerfordt, C.K.; Sivapalan, P.; Eklöf, J.; Boel, J.B.; Ostergaard, C.; Dessau, R.B.; Moberg, M.; Janner, J.; et al. Inhaled corticosteroids and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia in outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2024, 11, e001929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, R.H.; Heerfordt, C.K.; Boel, J.B.; Dessau, R.B.; Ostergaard, C.; Sivapalan, P.; Eklöf, J.; Jensen, J.-U.S. Inhaled corticosteroids and risk of lower respiratory tract infection with Moraxella catarrhalis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2023, 10, e001726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, B.R.; Fabbri, L.M.; Aaron, S.D.; Agusti, A.; Brook, R.D.; Criner, G.J.; Franssen, F.M.E.; Humbert, M.; Hurst, J.R.; de Oca, M.M.; et al. Differential Diagnosis of Suspected Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations in the Acute Care Setting: Best Practice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2023, 207, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrill, J.; Agustí, C.; de Celis, R.; Rañó, A.; Gonzalez, J.; Solé, T.; Xaubet, A.; Rodriguez-Roisin, R.; Torres, A. Bacterial colonisation in patients with bronchiectasis: Microbiological pattern and risk factors. Thorax 2002, 57, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borekci, S.; Halis, A.N.; Aygun, G.; Musellim, B. Bacterial colonization and associated factors in patients with bronchiectasis. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2016, 11, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, L.J.; Ritchie, A.; Pollard, E.; Johnston, S.L.; Mallia, P. Lower airway colonization and inflammatory response in COPD: A focus on Haemophilus influenzae. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2014, 9, 1119–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleimer, R.P. Glucocorticoids suppress inflammation but spare innate immune responses in airway epithelium. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2004, 1, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singanayagam, A.; Glanville, N.; Cuthbertson, L.; Bartlett, N.W.; Finney, L.J.; Turek, E.; Bakhsoliani, E.; Calderazzo, M.A.; Trujillo-Torralbo, M.-B.; Footitt, J.; et al. Inhaled corticosteroid suppression of cathelicidin drives dysbiosis and bacterial infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaav3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Su, L.; Huang, S.; Liu, L.; Ali, K.; Chen, Z. Epidemic Trends and Biofilm Formation Mechanisms of Haemophilus influenzae: Insights into Clinical Implications and Prevention Strategies. Infect Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 5359–5373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| H. influenzae Negative n = 3069 (83.78%) | H. influenzae Positive n = 594 (16.22%) | Total (n = 3663) | No ICSs (n = 2175, 59.38%) | Low-Dose ICSs (≤210 μg/day), (n = 484, 13.21%) | Moderate-Dose ICSs (211–625 μg/day), (n = 508, 13.87%) | High-Dose ICSs (≥626 μg/day), (n = 496, 13.54%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, Male, n (%) | 1213 39.52% | 219 36.87% | 1432 39.09% | 895 41.15% | 186 38.43% | 185 36.42% | 166 33.47% |

| Age group, years, n% | |||||||

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 66 (56–74) | 64 (53–71) | 66 (56–73) | 66 (57–74) | 64 (53–72) | 65 (55–73) | 65 (56–73) |

| <60 | 966 31.48% | 227 38.22% | 1193 32.57% | 663 30.48% | 188 38.84% | 171 33.66% | 171 34.47% |

| 60–69 | 927 30.21% | 184 30.98% | 1111 30.33% | 674 30.99% | 140 28.93% | 147 28.94% | 150 30.24% |

| 70–79 | 855 27.86% | 148 24.92% | 1003 27.38% | 615 16.79% | 113 23.35% | 144 28.35% | 131 26.41% |

| >79 | 321 10.46% | 35 5.89% | 356 9.72% | 223 10.25% | 43 8.88% | 46 9.06% | 44 8.87% |

| * Number of hospitalizations 12 months prior to cohort entry for all causes, n (%) | |||||||

| 1 | 2145 69.89% | 390 65.66% | 2535 71.47% | 1545 71.03% | 321 66.32% | 343 67.52% | 326 65.72% |

| ≥2 | 821 26.75% | 191 32.15% | 1012 28.53% | 559 25.7% | 155 32.02% | 144 28.35% | 154 31.04% |

| Comorbidities at cohort entry in the study population | |||||||

| COPD | 985 32.10% | 243 40.91% | 1228 33.52% | 507 23.31% | 156 32.23% | 258 50.79% | 307 61.89% |

| Asthma | 918 29.91% | 249 41.92% | 1167 31.86% | 329 15.13% | 185 32.22% | 303 59.65% | 350 70.56% |

| Hypertension | 888 28.93% | 165 27.78% | 1053 28.75% | 585 26.90% | 135 27.8% | 165 32.48% | 168 33.87% |

| Atrial fibrillation | 373 12.15% | 91 15.32% | 464 12.67% | 254 11.68% | 59 12.19% | 75 14.76% | 76 15.32% |

| Myocardial infarction | 200 6.52% | 32 5.38% | 232 6.33% | 144 6.62% | 29 5.99% | 28 5.51% | 31 6.25% |

| Heart failure | 270 8.80% | 58 9.76% | 328 8.95% | 173 7.95% | 39 8.05% | 60 11.81% | 56 11.29% |

| Renal failure | 120 3.91% | 31 5.21% | 151 4.12% | 86 3.95% | 16 3.30% | 23 4.53% | 26 5.24% |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 200 6.52% | 34 5.72% | 234 6.39% | 139 6.39% | 28 5.78% | 30 5.90% | 37 7.47% |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 323 10.52% | 67 11.28% | 390 10.65% | 239 10.99% | 48 9.92% | 54 10.63% | 49 9.88% |

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 | 101 3.29% | 19 3.20% | 120 3.28% | 68 3.13% | 18 3.72% | 17 3.35% | 17 3.43% |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 256 8.34% | 56 9.43% | 312 8.52% | 178 8.18% | 45 9.30% | 44 8.66% | 45 9.07% |

| Systemic connective tissue disease | 221 7.20% | 43 7.24% | 264 7.21% | 164 7.54% | 27 5.58% | 42 8.26% | 31 6.25% |

| Depression | 128 4.17% | 28 4.71% | 156 4.26% | 98 4.50% | 12 2.48% | 25 4.92% | 21 4.23% |

| Malignancy | 365 11.89% | 81 13.63% | 446 12.18% | 292 13.42% | 54 11.16% | 51 10.03% | 49 9.88% |

| Immune deficiency | 56 1.82% | 26 4.38% | 82 2.24% | 43 1.98% | 9 1.86% | 14 2.76% | 16 3.22% |

| ** Death within study period | 386 12.58% | 69 11.62% | 455 12.42% | 239 10.99% | 52 10.74% | 68 13.38% | 96 19.35% |

| Use of medication 12 months prior to cohort entry | |||||||

| OCSs, accumulated dose, mg, median (IQR) | 0 (0–500) | 250 (0–500) | 0 (0–500) | 0 (0–250) | 0 (0–500) | 250 (0–750) | 500 (250–1000) |

| No use, n (%) | 2494 81.26% | 441 74.24% | 2935 80.13% | 1955 89.88% | 380 78.51% | 325 63.98% | 275 55.44% |

| OCS use, n (%) | 575 18.74% | 153 25.76% | 728 19.87% | 220 10.11% | 104 21.49% | 183 36.02% | 221 44.55% |

| Low-dose OCSs (<625 mg), n (%) | 304 9.91% | 73 12.29% | 377 10.29% | 114 5.24% | 70 14.46% | 95 18.70% | 98 19.75% |

| High-dose OCSs (≥625 mg), n (%) | 271 8.84% | 80 13.47% | 351 9.58% | 106 4.87% | 34 7.02% | 88 17.32% | 123 34.80% |

| LABA, n (%) | 205 6.68% | 55 9.26% | 260 7.10% | 76 3.49% | 30 6.20% | 75 14.76% | 79 15.93% |

| LAMA, n (%) | 405 13.20% | 113 19.02% | 518 14.14% | 104 4.78% | 55 11.36% | 155 30.51% | 204 41.13% |

| Any use of antibiotics, n (%) | 2145 69.89% | 503 84.68% | 2648 72.29% | 1478 67.95% | 363 75% | 389 76.57% | 418 84.27% |

| H. influenzae-Positive ICS User (n = 305, 8.33%) | H. influenzae-Negative ICS User (n = 1183, 32.29%) | Total (n= 1488, 40.62%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accumulated equivalent ICS dose, mcg, median (IQR) * | 575.34 (210.41–986.30) | 328.77 (109.59–657.53) | 335.34 (157.80–762.74) |

| ICS users in defined tertiles **, n (%) | |||

| Low-dose ICSs (≤210 μg/day) | 69 22.62% | 414 35.00% | 483 32.46% |

| Moderate-dose ICSs (211–625 μg/day) | 95 31.15% | 414 35.00% | 509 34.21% |

| High-dose ICSs (≥626 μg/day) | 141 46.23% | 355 30.00% | 496 33.33% |

| Number of individual users by ICS type ***, n (%) | |||

| Budesonide | 246 80.66% | 1068 90.28% | 1314 88.30% |

| Fluticasone propionate | 130 42.62% | 394 33.30% | 524 35.21% |

| Fluticasone furoate | 11 3.60% | 44 3.72% | 55 3.70% |

| Beclomethasone | 20 6.56% | 125 3.41% | 145 9.75% |

| Mometasone | 4 1.31% | 13 10.57% | 17 1.14% |

| Ciclesonide | 5 1.64% | 59 4.99% | 64 4.30% |

| Number of mono- or combinations users, n (%) | |||

| Mono | 134 43.93% | 627 53.00% | 761 51.14% |

| 2-drugs combination | 263 86.23% | 1001 84.61% | 1264 84.95% |

| 3-drugs combination | 8 2.62% | 31 2.62% | 39 2.63% |

| Outcomes | No ICSs | Low-Dose ICSs (≤210 μg/day) | Moderate-Dose ICSs (211–625 μg/day) | High-Dose ICSs (≥626 μg/day) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-time Haemophilus influenzae isolation, n (%) | 277 7.56% | 63 1.72% | 93 2.54% | 137 3.74 | 570 15.56% |

| Death, n (%) | 188 5.13% | 39 1.06% | 51 1.39% | 55 1.50 | 333 9.09% |

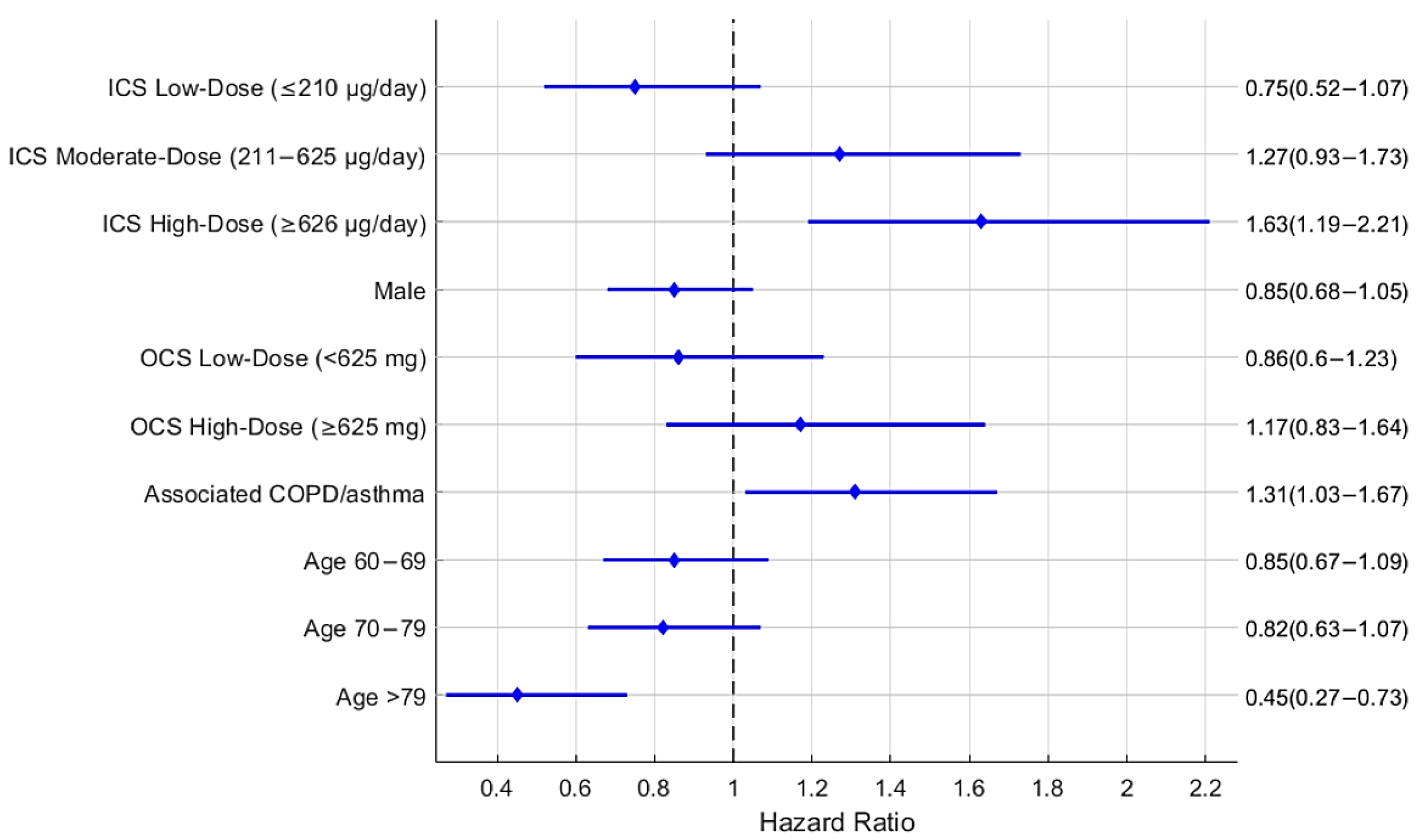

| Unadjusted Hazard Ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Hazard Ratio | 95%HR Confidence Interval | p-Value | Hazard Ratio | 95%HR Confidence Interval | p-Value | ||

| No ICS treatment | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

| Low-dose ICSs (≤210 μg/day) | 0.82 | 0.57 | 1.17 | 0.264 | 0.75 | 0.52 | 1.07 | 0.115 |

| Moderate-dose ICSs (211–625 μg/day) | 1.48 | 1.12 | 1.97 | 0.006 | 1.27 | 0.93 | 1.73 | 0.127 |

| High-dose ICSs (≥626 μg/day) | 1.97 | 1.51 | 2.58 | <0.0001 | 1.63 | 1.19 | 2.21 | <0.005 |

| Female | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Male | 0.83 | 0.67 | 1.03 | 0.096 | 0.85 | 0.68 | 1.05 | 0.132 |

| No OCSs | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Low-dose OCSs: <625 mg | 1.02 | 0.72 | 1.44 | 0.931 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 1.23 | 0.402 |

| High-dose OCSs: ≥625 mg | 1.46 | 1.06 | 2.01 | 0.022 | 1.17 | 0.83 | 1.64 | 0.376 |

| No associated COPD or asthma or both | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Associated COPD or asthma or both | 1.53 | 1.23 | 1.88 | <0.0001 | 1.31 | 1.03 | 1.67 | 0.023 |

| Age 18–59 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Age 60–69 | 0.85 | 0.66 | 1.09 | 0.190 | 0.85 | 0.67 | 1.09 | 0.210 |

| Age 70–79 | 0.82 | 0.64 | 1.06 | 0.135 | 0.82 | 0.63 | 1.07 | 0.140 |

| Age >79 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.74 | <0.005 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.73 | <0.005 |

| Parameter | 18–59 Years | 60–69 Years | 70–79 Years | >79 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No ICS treatment | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Low-dose ICSs (≤210 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.589 | 0.733 | <0.005 |

| Moderate-dose ICSs (211–625 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.016 | 0.607 | 0.006 |

| High-dose ICSs (≥626 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.348 | 0.082 | 0.945 |

| Parameter | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| No ICS treatment | Ref. | Ref. |

| Low-dose ICSs (≤210 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.388 |

| Moderate-dose ICSs (211–625 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.010 |

| High-dose ICSs (≥626 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.680 |

| Parameter | No OCS Treatment | Low-Dose OCSs <625 mg | High-Dose OCSs ≥625 mg |

|---|---|---|---|

| No ICS treatment | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Low-dose ICSs (≤210 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.608 | 0.619 |

| Moderate-dose ICSs (211–625 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.348 | 0.173 |

| High-dose ICSs (≥626 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.163 | 0.760 |

| Parameter | No Concomitant COPD or Asthma or Both | Concomitant COPD or Asthma or Both |

|---|---|---|

| No ICS treatment | Ref. | Ref. |

| Low-dose ICSs (≤210 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.476 |

| Moderate-dose ICSs (211–625 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.710 |

| High-dose ICSs (≥626 μg/day) | Ref. | 0.957 |

| Parameter | Hazard Ratio | 95%HR Confidence Interval | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No ICS treatment | Ref. | |||

| Low-dose ICSs (≤210 μg/day) | 0.87 | 0.59 | 1.27 | 0.46 |

| Moderate-dose ICSs (211–625 μg/day) | 1.31 | 0.91 | 1.87 | 0.14 |

| High-dose ICSs (≥626 μg/day) | 1.61 | 1.02 | 2.54 | 0.042 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Afrose, D.; Rønn, C.P.; Eklöf, J.; Vognsen, A.K.; Tønnesen, L.L.; Bertelsen, B.B.; Boel, J.B.; Andersen, C.Ø.; Dessau, R.B.C.; Pinholt, M.; et al. Inhaled Corticosteroid Use and Risk of Haemophilus influenzae Isolation in Patients with Bronchiectasis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8557. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238557

Afrose D, Rønn CP, Eklöf J, Vognsen AK, Tønnesen LL, Bertelsen BB, Boel JB, Andersen CØ, Dessau RBC, Pinholt M, et al. Inhaled Corticosteroid Use and Risk of Haemophilus influenzae Isolation in Patients with Bronchiectasis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8557. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238557

Chicago/Turabian StyleAfrose, Dil, Christian Philip Rønn, Josefin Eklöf, Anna Kubel Vognsen, Louise Lindhardt Tønnesen, Barbara Bonnesen Bertelsen, Jonas Bredtoft Boel, Christian Østergaard Andersen, Ram Benny Christian Dessau, Mette Pinholt, and et al. 2025. "Inhaled Corticosteroid Use and Risk of Haemophilus influenzae Isolation in Patients with Bronchiectasis: A Retrospective Cohort Study" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8557. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238557

APA StyleAfrose, D., Rønn, C. P., Eklöf, J., Vognsen, A. K., Tønnesen, L. L., Bertelsen, B. B., Boel, J. B., Andersen, C. Ø., Dessau, R. B. C., Pinholt, M., Jensen, J.-U., & Sivapalan, P. (2025). Inhaled Corticosteroid Use and Risk of Haemophilus influenzae Isolation in Patients with Bronchiectasis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8557. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238557