Acceptance Factors and Barriers to the Implementation of Digital Interventions in Older People with Dementia and/or Their Caregivers: An Umbrella Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- 1.

- What are the barriers to implementing digital interventions for people with dementia and/or their caregivers?

- 2.

- What are the facilitators to implementing digital interventions for people with dementia and/or their caregivers?

- 3.

- What technologies have been proposed for people with dementia and/or their caregivers?

- 4.

- How effective were these digital interventions in alleviating the targeted problems?

2. Methods

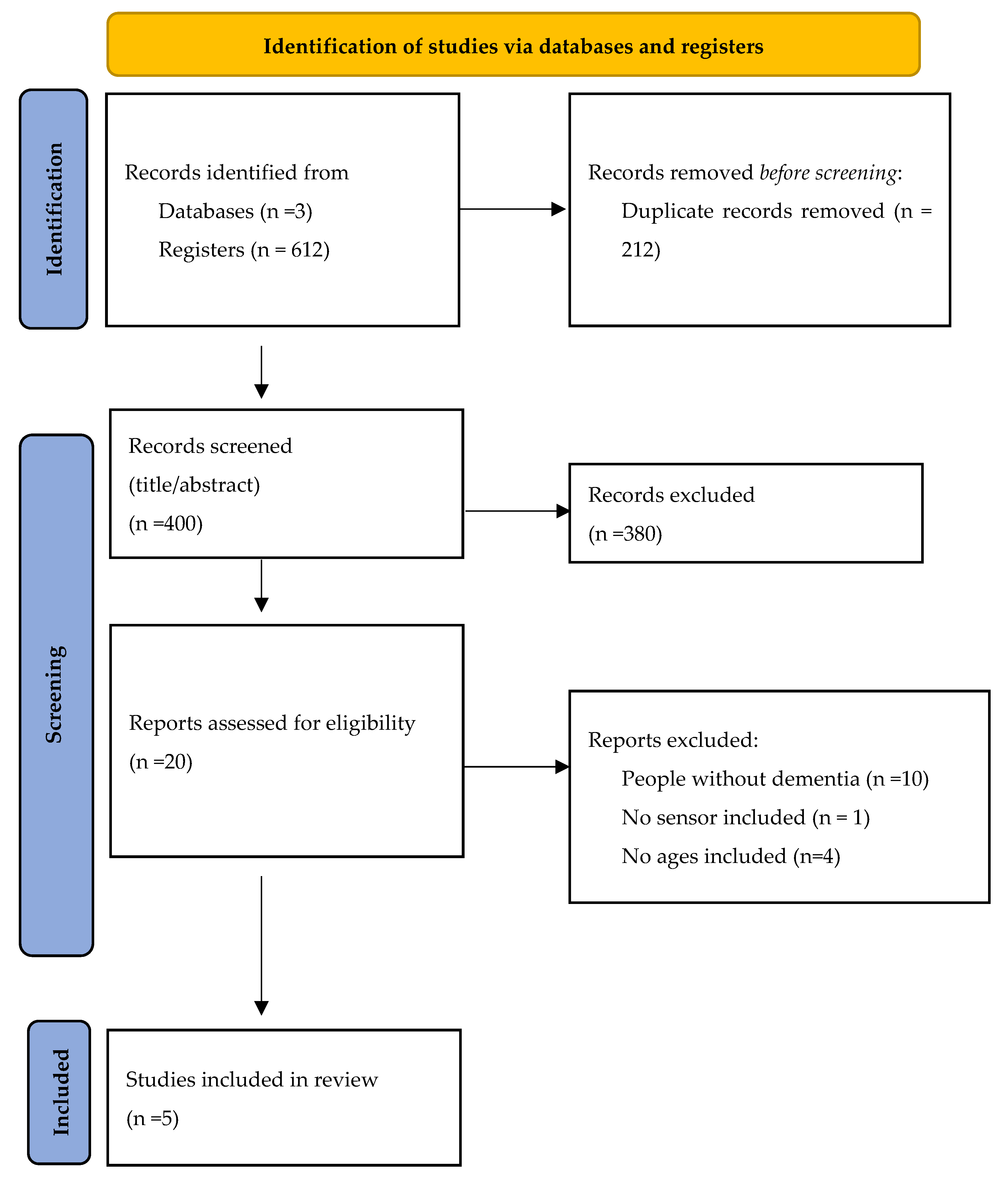

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Review Characteristics

3.2. Overlap Assessment Results

3.3. Study Characteristics

3.4. People with Dementia

3.4.1. Technology Intervention

3.4.2. Acceptance of Technologies

3.4.3. Barriers to Technologies

3.4.4. Findings for People with Dementia

3.5. Informal Caregivers

3.5.1. Technology Intervention

3.5.2. Acceptance of Technologies

3.5.3. Barriers to Technologies

3.6. Findings for Caregivers

Acceptance and Transversal Barriers to Technology

3.7. Cross-Cutting Findings

Critical Appraisal

3.8. Effectiveness of Digital Interventions

4. Discussion

5. Recommendations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses |

| PWD | People with Dementia |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

References

- Ganesan, B.; Gowda, T.; Al-Jumaily, A.; Fong, K.N.K.; Meena, S.K.; Tong, R.K.Y. Ambient assisted living technologies for older adults with cognitive and physical impairments: A review. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 10470–10481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, S.A.; Acar, D.; Daffner, K.R. Dementia. Am. J. Med. 2018, 131, 1161–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekhon, H.; Sekhon, K.; Launay, C.; Afililo, M.; Innocente, N.; Vahia, I.; Rej, S.; Beauchet, O. Telemedicine and the rural dementia population: A systematic review. Maturitas 2021, 143, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, S.; Bleijlevens, M.; Roe, B.; Saks, K.; Martin, M.S.; Stephan, A.; Suhonen, R.; Zabalegui, A.; Hallberg, I.R.; RightTimeCarePlace Consortium. Dementia care in European countries, from the perspective of people with dementia and their caregivers. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Jhoo, J.H.; Jang, J.W. The effect of telemedicine on cognitive decline in patients with dementia. J. Telemed. Telecare 2017, 23, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, M. Effectiveness of person-centered care on people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Interv. Aging 2017, 12, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, D.; Roberts, G.; Wu, M.L.; Ford, R.; Doyle, C. A systematic review of the effect of telephone, internet or combined support for carers of people living with Alzheimer’s, vascular or mixed dementia in the community. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2016, 66, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severs, E.; James, T.; Letrondo, P.; Løvland, L.; Marchant, N.L.; Mukadam, N. Traumatic life events and risk for dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, N.; Page, T.E.; Daley, S.; Brown, A.; Bowling, A.; Basset, T.; Livingston, G.; Knapp, M.; Murray, J.; Banerjee, S. Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s Dement. J. Alzheimer’s Assoc. 2017, 13, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Dementia. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 30 June 2023).

- Dogra, S.; Dunstan, D.W.; Sugiyama, T.; Stathi, A.; Gardiner, P.A.; Owen, N. Active Aging and Public Health: Evidence, Implications, and Opportunities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2022, 43, 439–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeken, F.; Rezo, A.; Hinz, M.; Discher, R.; Rapp, M.A. Evaluation of Technology-Based Interventions for Informal Caregivers of Patients With Dementia-A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry Off. J. Am. Assoc. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2019, 27, 426–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, M.; Zhao, Y.; Xiao, H.; Li, C.; Wang, Z. Internet-Based Supportive Interventions for Family Caregivers of People With Dementia: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayly, M.; Morgan, D.; Chow, A.F.; Kosteniuk, J.; Elliot, V. Dementia-Related Education and Support Service Availability, Accessibility, and Use in Rural Areas: Barriers and Solutions. Can. J. Aging La Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 2020, 39, 545–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Kim, S.K.; Kim, Y.; Go, Y. Effects of App-Based Mobile Interventions for Dementia Family Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2022, 51, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covinsky, K.E.; Newcomer, R.; Fox, P.; Wood, J.; Sands, L.; Dane, K.; Yaffe, K. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2003, 18, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, P.K.; Cheung, G.; Fung, R.; Koo, S.; Sit, E.; Pun, S.H.; Au, A. Patient and Caregiver Characteristics Associated with Depression in Dementia Caregivers. J. Psychol. Chin. Soc. 2008, 9, 195–224. [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli, T.; Mason, S.; Tetlow, H.; Reilly, S.; Giebel, C. Exploring the views and the use of information and communication technologies to access post-diagnostic support by people living with dementia and unpaid carers: A systematic review. Aging Ment. Health 2023, 27, 2329–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C.Y.; Wu, H.S.; Hsiao, C.Y. Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2015, 62, 340–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, R.; Beach, S.R. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA 1999, 282, 2215–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisdorfer, C.; Czaja, S.J.; Loewenstein, D.A.; Rubert, M.P.; Argüelles, S.; Mitrani, V.B.; Szapocznik, J. The effect of a family therapy and technology-based intervention on caregiver depression. Gerontol. 2003, 43, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flandorfer, P. Population ageing and socially assistive robots for elderly persons: The importance of sociodemographic factors for user acceptance. Int. J. Popul. Res. 2012, 2012, 829835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, M.M.; Zarit, S.H.; Groot Zwaaftink, R.B.; Cuijpers, P.; Pot, A.M. Effectiveness of an Internet intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: Results of a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czaja, S.J.; Charness, N.; Fisk, A.D.; Hertzog, C.; Nair, S.N.; Rogers, W.A.; Sharit, J. Factors predicting the use of technology: Findings from the Center for Research and Education on Aging and Technology Enhancement (CREATE). Psychol. Aging 2006, 21, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chan, A.H.S. Gerontechnology acceptance by elderly Hong Kong Chinese: A senior technology acceptance model (STAM). Ergonomics 2014, 57, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peek, S.T.M.; Wouters, E.J.M.; van Hoof, J.; Luijkx, K.G.; Boeije, H.R.; Vrijhoef, H.J.M. Factors influencing acceptance of technology for aging in place: A systematic review. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2014, 83, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charness, N.; Boot, W.R. Aging and information technology use: Potential and barriers. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuerbis, A.; Mulliken, A.; Muench, F.; Moore, A.A.; Gardner, D. Older adults and mobile technology: Factors that enhance and inhibit utilization in the context of behavioral health. Ment. Health Addict. Res. 2017, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, M.; Gates, A.; Pieper, D.; Fernandes, R.M.; Tricco, A.C.; Moher, D.; Brennan, S.E.; Li, T.; Pollock, M.; Lunny, C.; et al. Reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions: Development of the PRIOR statement. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2022, 378, e070849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Gerritzen, E.V.; McDermott, O.; Orrell, M. Exploring the Role of Web-Based Interventions in the Self-management of Dementia: Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piau, A.; Wild, K.; Mattek, N.; Kaye, J. Current State of Digital Biomarker Technologies for Real-Life, Home-Based Monitoring of Cognitive Function for Mild Cognitive Impairment to Mild Alzheimer Disease and Implications for Clinical Care: Systematic Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019, 21, e12785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de-Moraes-Ribeiro, F.E.; Moreno-Cámara, S.; da-Silva-Domingues, H.; Palomino-Moral, P.Á.; Del-Pino-Casado, R. Effectiveness of Internet-Based or Mobile App Interventions for Family Caregivers of Older Adults with Dementia: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieper, D.; Antoine, S.-L.; Mathes, T.; Neugebauer, E.A.M.; Eikermann, M. Systematic review finds overlapping reviews were not mentioned in every other overview. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 67, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhang, S.; Xin, M.; Zhu, M.; Lu, W.; Mo, P.K. Electronic health literacy and health-related outcomes among older adults: A systematic review. Prev. Med. 2022, 157, 106997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Saldanha, C.; Ellis, U.; Sattar, S.; Haase, K.R. eHealth literacy among older adults living with cancer and their caregivers: A scoping review. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2022, 13, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Hao, X.; Qin, Y.; Li, K. Benefits of and barriers to telehealth for the informal caregivers of elderly individuals in rural areas: A scoping review. Aust. J. Rural Health 2022, 30, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivunen, M.; Saranto, K. Nursing professionals’ experiences of the facilitators and barriers to the use of telehealth applications: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018, 32, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, A.; Thompson, H.; Demiris, G. A systematic review of the use of technology for reminiscence therapy. Health Educ. Behav. Off. Publ. Soc. Public Health Educ. 2014, 41 (Suppl. S1), 51S–61S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.S.; Pittman, C.A.; Price, C.L.; Nieman, C.L.; Oh, E.S. Telemedicine and Dementia Care: A Systematic Review of Barriers and Facilitators. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2021, 22, 1396–1402.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, A.K.; Yoshinaga, P.D.; Rittiphairoj, T.; Li, T. Telerehabilitation for people with low vision. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 1, CD011019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simblett, S.; Greer, B.; Matcham, F.; Curtis, H.; Polhemus, A.; Ferrão, J.; Gamble, P.; Wykes, T. Barriers to and Facilitators of Engagement With Remote Measurement Technology for Managing Health: Systematic Review and Content Analysis of Findings. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018, 20, e10480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Years | Sample, N | Population | Participant Characteristic | Location of Intervention | Intervention Time | Technology | Technology Category | Instrument | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deeken et al. [12] | 2018 | 29 studies | Informal Caregivers of PWD | Mean age 62 years. 11 to 299 Informal Caregivers | Home | 30 days to 12 months. | Telephone, web-based interventions, DVD/video, or a combination of telephone and computer or DVD/video | ICT | CES-D, BDI, GDS, PHQ, BSI, ZBI, RMBPC, ICS, CSI, CAIVAS | NS |

| Lee et al. [32] | 2021 | 11 Studies | PWD | 59–92 years. 11 to 116 participants; | Home, Day and activity centers | Intervention sessions varied | Smartphones or tablets, computers, smartwatches, and followed by earpieces or headphones, app | ICT | MMSE The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology Questionnaire | Denmark, Sweden, United Kingdom, Netherlands, United States |

| Piau et al. [33] | 2019 | 26 studies | PWD | Mean age 64 to 89 years. 12 to 279 participants | Home, Adult day care center, nursing home, Remote clinic, Hospital, academic center | 20 to 119 sessions 24 days to 9 months | Infrared motion sensors and magnetic contact door sensors; smart homes with combination motion and light sensors on the ceilings and combination door and temperature sensors on cabinets and doors; wrist-worn activity sensor device; GPS-enabled mobile phone; accelerometer; inertial sensors; IVRc technology; desktop computers; tablet; Nintendo Wii balance board; pill box | Smart home technologies and Smart car technologies, wearable ICT, game. | MMSE and CDR | NS |

| Shin et al. [15] | 2022 | 5 Studies | Informal Caregivers of PWD | 230 caregivers | Home | 2 weeks to 3 months | Smartphone and mini-pad | ICT | CES-D, PSS, SSCQ, ZBI, QoL: AIOS, HADS, and saliva cortisol levels | USA, Netherlands, UK and South Korea |

| de-Moraes-Ribeiro et al. [34] | 2024 | 22 Studies | Informal Caregivers of PWD | 2761 Informal caregivers | Home | 1 month to 2 years | Internet-based and mobile application | ICT | CES-D, ZBI, HADS, BDI, CCS, CSI, CGS, CSES, EQ5D-VAS, EQ5D+c, EuroQol, GHQ-12, GSE, HHI, ICECAP-O, IESS, MOS-SSS, MSPSS, NHP, NPI, PACS, PQOL, PSS, PSS-14, RCSS, RIS, RPFS, RSCSE, RSS, SF-12v2, SSCQ, STAI and WHOQOL-BREF | USA, Netherlands, France, UK, New Zealand, Canada, Germany, Spain, South Korea, Australia, India and Portugal |

| Authors | Intervention | Acceptance | Barriers | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al. [32] | Self-management concept, independence, activities of daily living, communication, and cognition | Positive impact on self-management | Difficulties in connecting, communicating, accessing, and using technology. Distrust and fear of being watched. Forgetting to use App. | Positive impact on the self-management concept |

| Piau et al. [33] | Real-life early detection and follow-up of cognitive function | NS | Distrust and fear of being watched. Forgetting to use and/or carry portable devices. Need for technical expertise. Dementia severity. | NS |

| Authors | Intervention | Acceptance | Barriers | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deeken et al. [12] | Treatments of behavioral activation, psychoeducation, coping strategies, supportive approaches, or cognitive behavioral therapy. Telephone-based cognitive behavioral therapy and used a telephone-based collaborative care management program with multiple modules, such as communication skills, stress management, and coping skills. | NS | Middle-aged and older adults have been shown to have lower self-efficacy and increased anxiety compared with younger adults | Positive impact on reducing depression and overload |

| Shin et al. [15] | Providing feedback on caregiving activities and monitoring emotions of caregivers with in-person meetings and phone calls for monitoring and feedback | More cost-effective than face-to-face interventions. The knowledge and skills needed to care for patients | Need for technical knowledge | Increased carer competence and quality of life. No significant effects on caregiver burden, depression or stress. |

| de-Moraes-Ribeiro et al. [34] | Psychoeducational, multicomponent and psychotherapeutic interventions | Psychoeducational interventions: The knowledge and skills needed to care for patients. Multicomponent interventions: Alleviates the emotional and physical burdens associated with caregiving. Psychotherapeutic interventions: improvements in depression and perceived social support. | NS | Psychotherapeutic interventions highlighted improvements in depression and perceived social support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madeira, R.; Esteves, D.; Pinto, N.; Vercelli, A.; Pato, M.V. Acceptance Factors and Barriers to the Implementation of Digital Interventions in Older People with Dementia and/or Their Caregivers: An Umbrella Review. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7974. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227974

Madeira R, Esteves D, Pinto N, Vercelli A, Pato MV. Acceptance Factors and Barriers to the Implementation of Digital Interventions in Older People with Dementia and/or Their Caregivers: An Umbrella Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):7974. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227974

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadeira, Ricardo, Dulce Esteves, Nuno Pinto, Alessandro Vercelli, and Maria Vaz Pato. 2025. "Acceptance Factors and Barriers to the Implementation of Digital Interventions in Older People with Dementia and/or Their Caregivers: An Umbrella Review" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 7974. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227974

APA StyleMadeira, R., Esteves, D., Pinto, N., Vercelli, A., & Pato, M. V. (2025). Acceptance Factors and Barriers to the Implementation of Digital Interventions in Older People with Dementia and/or Their Caregivers: An Umbrella Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 7974. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14227974