Melatonin at the Crossroads of Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Cancer Therapy

Abstract

1. Introduction

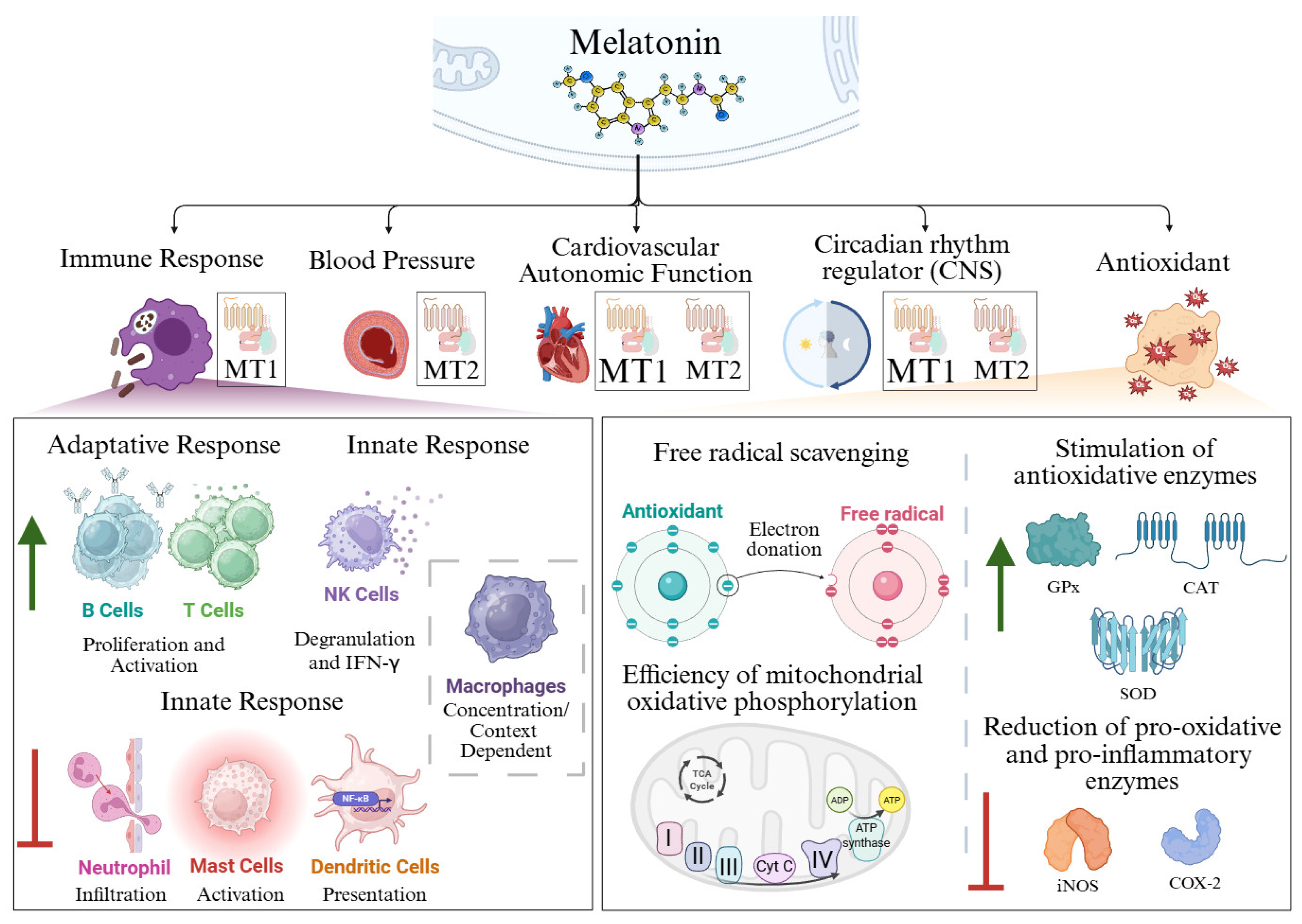

2. Antioxidant Function of Melatonin

- (a)

- (b)

- (c)

2.1. Free Radical Scavenging

2.2. Stimulation of Antioxidative Enzymes

2.3. Efficiency of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation

3. Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Melatonin

3.1. Adaptative Immune Response

3.1.1. T Cells

3.1.2. B Cells

3.2. Innate Immune Response

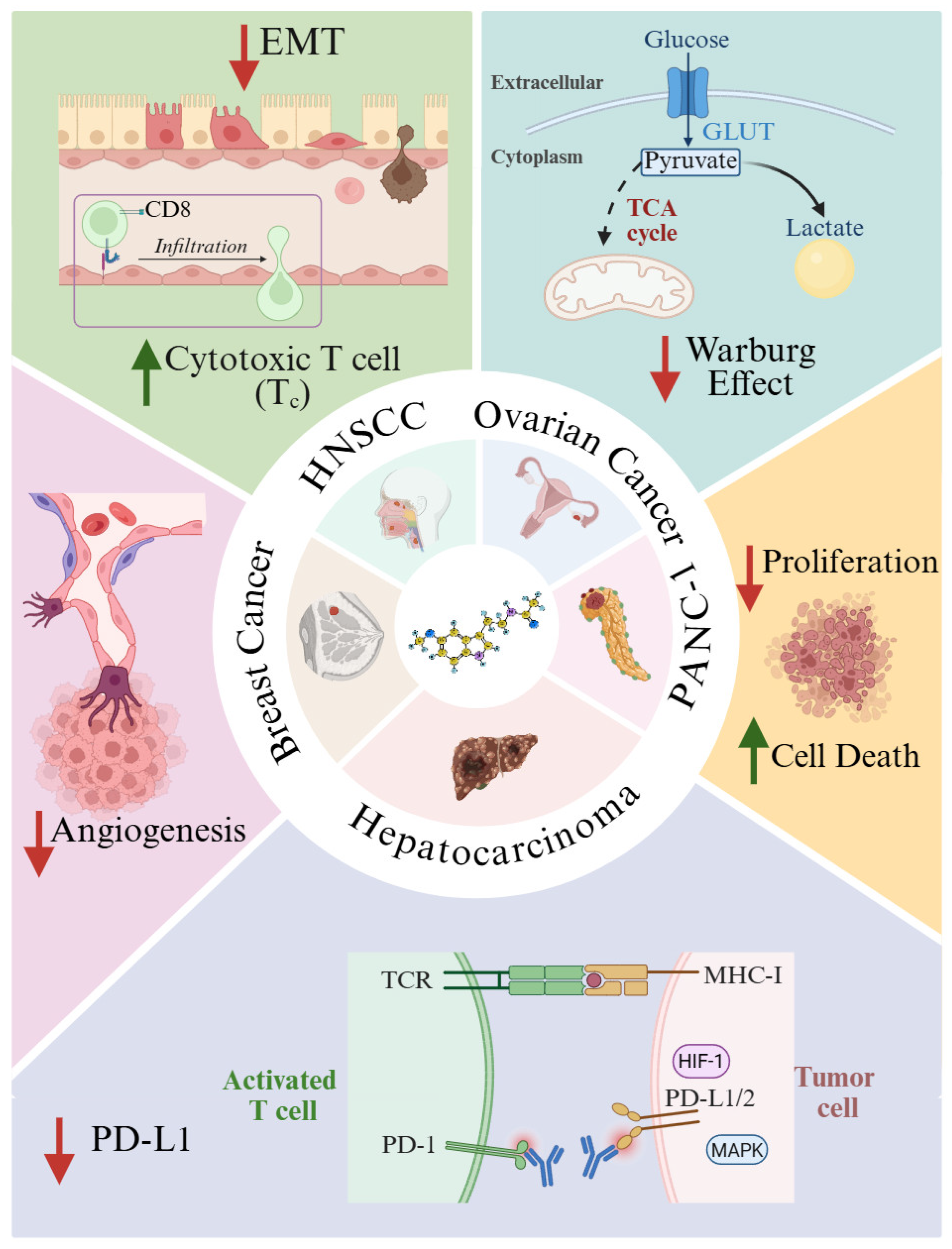

4. Melatonin in Cancer: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential

5. Modulation of the Tumor Immune Microenvironment

- Elimination. Innate and adaptive immune components act to eradicate emerging tumor cells.

- Equilibrium. Tumor cells with low immunogenicity survive immune pressure and continue unchecked proliferation.

- Escape. Tumor cells downregulate MHC-I expression, impairing immune recognition and culminating in the emergence of clinically detectable tumors.

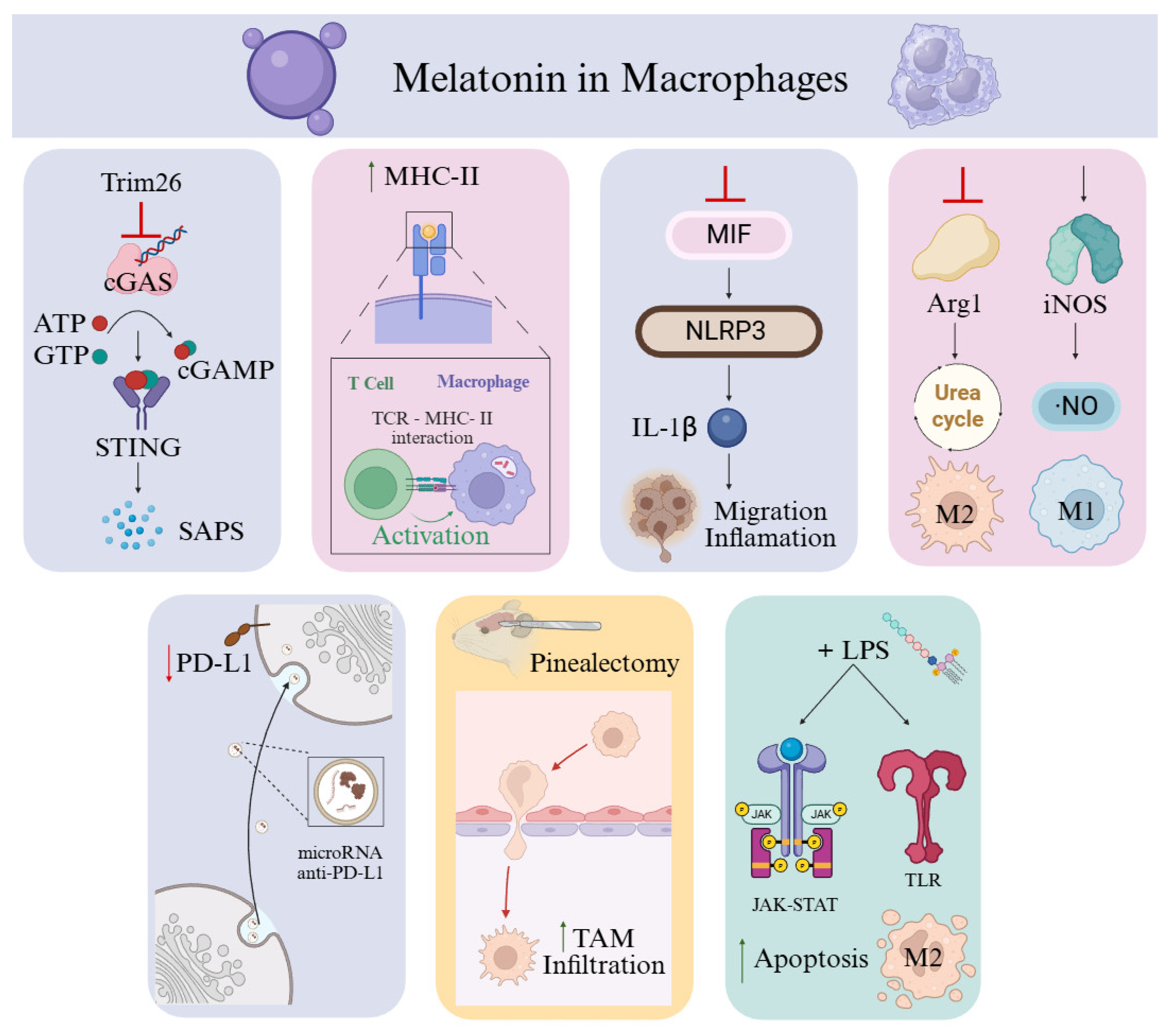

6. Macrophages as a Therapeutic Target of Melatonin in Cancer

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AANAT | Aralkylamine N-Acetyltransferase |

| ABST | 2,2′-Azino-Bis(3-Ethylbenzthiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid) |

| ADCC | Antibody-Dependent Cellular Cytotoxicity |

| AFMK | N-Acetyl-N-Formyl-5-Methoxyquinuramine |

| AMK | N-Acetyl-5-Methoxyquinuramine |

| Arg1 | Arginase 1 |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| Bcl-2 | B-Cell Lymphoma 2 |

| BCR | B Cell Receptor |

| bFGF | Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| BMAL1 | Brain And Muscle ARNT-Like Protein 1 |

| BReg | Regulatory B Cells |

| CAFs | Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts |

| CAT | Catalase |

| cGAMP | Cyclic GMP–AMP |

| cGAS | Cyclic GMP–AMP Synthase |

| CD8 | Cluster Of Differentiation 8 (Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte Marker) |

| COX-2 | Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CRF | Cancer-Related Fatigue |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12 |

| Cyt C | Cytochrome C |

| DC | Dendritic Cells |

| EAE | Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis |

| EC | Endothelial Cells |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix |

| EMT | Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition |

| ERK1/2–FOSL1 | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinases 1 And 2—Fos-Like Antigen 1 |

| FasL | Fas Ligand (CD95 Ligand) |

| GLUT | Glucose Transporter |

| GLUT1 | Glucose Transporter 1 |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte–Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor |

| GPx | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| GR | Glutathione Reductase |

| GSH | Reduced Glutathione |

| GSSG | Oxidized Glutathione |

| GTP | Guanosine Triphosphate |

| GzmB | Granzyme B |

| HIF | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor |

| HNSCC | Head And Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

| HUVECs | Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells |

| iNOS | Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase |

| IL-1β | Interleukin-1 Beta |

| JAK-STAT | Janus Kinase And Signal Transducer And Activator Of Transcription |

| Ki67 | Proliferation Marker Protein Ki-67 |

| KIR | Killer Immunoglobulin-Like Receptors |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MCF-7 | Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells |

| MHC-I/II | Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I/II |

| MiaPaCa-2 | Human Pancreatic Cancer |

| MIF | Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor |

| MT1R | Melatonin Receptor Type 1 |

| NKG2D | Natural Killer Group 2, Member D |

| NK | Natural Killer |

| NKp30 | Natural Killer Cell P30-Related Protein (NCR3) |

| NLRP3 | NOD-Like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain-Containing 3 |

| NO | Nitric Oxide Radical |

| NO/NO | Nitric Oxide |

| O2− | Superoxide Anions |

| OH | Hydroxyl Radicals |

| ONOO− | Peroxynitrite Anions |

| PANC-1 | Human Pancreatic Carcinoma Cell Line |

| PCNA | Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen |

| PDC | Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex |

| PD-1 | Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 |

| PDCA | Programmed Cell Death Activator |

| PDGFC | Platelet Derived Growth Factor C |

| PD-L1 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1 |

| PD-L1/2 | Programmed Death-Ligand 1/2 |

| PEPT1/2 | Peptide Transporter 1/2 |

| RFA | Radiofrequency Ablation |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| ROR-α | Retinoic Acid-Related Orphan Receptor Alpha |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RZR-β | Orphan Receptor Retinoid Z Receptor Beta |

| SAPS | Serum Amyloid P Component |

| SIRT3 | Stimulates Sirtuin 3 |

| siRNA | Small Interfering RNA |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| STRING | Search Tool For The Retrieval Of Interacting Genes/Proteins |

| TAM | Tumor-Associated Macrophage |

| TANs | Tumor-Associated Neutrophils |

| TCA Cycle | Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle (Krebs Cycle) |

| TCR | T-Cell Receptor |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor Beta |

| THP-1 Cells | Human Monocytic Cell Line Derived From A Patient With Acute Monocytic Leukemia |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| TRAIL | TNF-Related Apoptosis-Inducing Ligand |

| TRIM26 | Tripartite Motif-Containing Protein 26 |

| Treg | Regulatory T Cells |

| TSCM | Memory Stem T Cells |

| TFH | Follicular Memory T Cells |

| TEM | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TEM | Effector Memory T Cells |

| TM | Memory T Cells |

| TRM | Resident Memory T Cells |

| UCP | Uncoupling Proteins |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| VEGFA | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A |

| Δψ | Membrane Potential |

| 1O2 | Singlet Oxygen |

References

- Minich, D.M.; Henning, M.; Darley, C.; Fahoum, M.; Schuler, C.B.; Frame, J. Is Melatonin the “Next Vitamin D”?: A Review of Emerging Science, Clinical Uses, Safety, and Dietary Supplements. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.B.; Case, J.D.; Takahashi, Y.; Lee, T.H.; Mori, W. Isolation of Melatonin, the Pineal Gland Factor that Lightens Melanocytes1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 80, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.B.; Case, J.D.; Takahashi, Y. Isolation of Melatonin and 5-Methoxyindole-3-Acetic Acid from Bovine Pineal Glands. J. Biol. Chem. 1960, 235, 1992–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.B.; Case, J.D.; Mori, W.; Wright, M.R. Melatonin in Peripheral Nerve. Nature 1959, 183, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, D.X.; Manchester, L.C.; Esteban-Zubero, E.; Zhou, Z.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin as a Potent and Inducible Endogenous Antioxidant: Synthesis and Metabolism. Molecules 2015, 20, 18886–18906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnao, M.B.; Giraldo-Acosta, M.; Castejón-Castillejo, A.; Losada-Lorán, M.; Sánchez-Herrerías, P.; El Mihyaoui, A.; Cano, A.; Hernández-Ruiz, J. Melatonin from Microorganisms, Algae, and Plants as Possible Alternatives to Synthetic Melatonin. Metabolites 2023, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Mayo, J.C.; Tan, D.X.; Sainz, R.M.; Alatorre-Jimenez, M.; Qin, L. Melatonin as an Antioxidant: Under Promises but over Delivers. J. Pineal Res. 2016, 61, 253–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Tian, X.; Ma, T.; Tao, J.; Zhu, K.; Song, Y.; et al. Mitochondria Synthesize Melatonin to Ameliorate Its Function and Improve Mice Oocyte’s Quality under in Vitro Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Sharma, R.N.; Chuffa, L.G.D.E.A.; Silva, D.G.H.D.A.; Rosales-Corral, S. Intrinsically Synthesized Melatonin in Mitochondria and Factors Controlling Its Production. Histol. Histopathol. 2025, 40, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suofu, Y.; Li, W.; Jean-Alphonse, F.G.; Jia, J.; Khattar, N.K.; Li, J.; Baranov, S.V.; Leronni, D.; Mihalik, A.C.; He, Y.; et al. Dual Role of Mitochondria in Producing Melatonin and Driving GPCR Signaling to Block Cytochrome c Release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E7997–E8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Choi, G.H.; Back, K. Functional Characterization of Serotonin N-Acetyltransferase in Archaeon Thermoplasma Volcanium. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Kurth, S.; Pugin, B.; Bokulich, N.A. Microbial Melatonin Metabolism in the Human Intestine as a Therapeutic Target for Dysbiosis and Rhythm Disorders. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Yu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Sharma, R.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin Synthesis and Function: Evolutionary History in Animals and Plants. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, R.J.; Carneiro, R.C.; Oh, C.S. Melatonin in Relation to Cellular Antioxidative Defense Mechanisms. Horm. Metab. Res. 1997, 29, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajwa, V.S.; Shukla, M.R.; Sherif, S.M.; Murch, S.J.; Saxena, P.K. Role of Melatonin in Alleviating Cold Stress in Arabidopsis Thaliana. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 56, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tordjman, S.; Chokron, S.; Delorme, R.; Charrier, A.; Bellissant, E.; Jaafari, N.; Fougerou, C. Melatonin: Pharmacology, Functions and Therapeutic Benefits. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooley, J.J.; Chamberlain, K.; Smith, K.A.; Khalsa, S.B.S.; Rajaratnam, S.M.W.; Van Reen, E.; Zeitzer, J.M.; Czeisler, C.A.; Lockley, S.W. Exposure to Room Light before Bedtime Suppresses Melatonin Onset and Shortens Melatonin Duration in Humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, E463–E472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Giménez, V.M.; de las Heras, N.; Lahera, V.; Tresguerres, J.A.F.; Reiter, R.J.; Manucha, W. Melatonin as an Anti-Aging Therapy for Age-Related Cardiovascular and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 888292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.-F.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Tsai, W.-C.; Su, C.-W.; Hsu, C.-W.; Yuan, S.-S.F. Decreased Circulating Melatonin with Loss of Age-Related Biphasic Change in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühlwein, E.; Hauger, R.L.; Irwin, M.R. Abnormal Nocturnal Melatonin Secretion and Disordered Sleep in Abstinent Alcoholics. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pieri, C.; Marra, M.; Moroni, F.; Recchioni, R.; Marcheselli, F. Melatonin: A Peroxyl Radical Scavenger More Effective than Vitamin E. Life Sci. 1994, 55, PL271–PL276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeggeler, B.; Thuermann, S.; Dose, A.; Schoenke, M.; Burkhardt, S.; Hardeland, R. Melatonin’s Unique Radical Scavenging Properties—Roles of Its Functional Substituents as Revealed by a Comparison with its Structural Analogs. J. Pineal Res. 2002, 33, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.B.; Ali, A.; Bilal, M.; Rashid, S.M.; Wani, A.B.; Bhat, R.R.; Rehman, M.U. Melatonin and Health: Insights of Melatonin Action, Biological Functions, and Associated Disorders. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 2437–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, J.; Aulinas, A. Physiology of the Pineal Gland and Melatonin. Endotext 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ekmekcioglu, C. Melatonin Receptors in Humans: Biological Role and Clinical Relevance. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2006, 60, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klosen, P.; Lapmanee, S.; Schuster, C.; Guardiola, B.; Hicks, D.; Pevet, P.; Felder-Schmittbuhl, M.P. MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors are expressed in nonoverlapping neuronal populations. J. Pineal Res. 2019, 67, e12575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvo, J.R.; Maldonado, M.D. Immunoregulatory Properties of Melatonin in the Humoral Immune System: A Narrative Review. Immunol. Lett. 2024, 269, 106901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitimus, D.M.; Popescu, M.R.; Voiculescu, S.E.; Panaitescu, A.M.; Pavel, B.; Zagrean, L.; Zagrean, A.M. Melatonin’s Impact on Antioxidative and Anti-Inflammatory Reprogramming in Homeostasis and Disease. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Xin, Y.; Hou, Y.; Xiang, X.; Deng, Y.; Yang, B.; Yu, W. Melatonin-Derived Carbon Dots with Free Radical Scavenging Property for Effective Periodontitis Treatment via the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 8307–8324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Reiter, R.; Manchester, L.; Yan, M.; El-Sawi, M.; Sainz, R.; Mayo, J.; Kohen, R.; Allegra, M.; Hardelan, R. Chemical and Physical Properties and Potential Mechanisms: Melatonin as a Broad Spectrum Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenger. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005, 2, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, C.E.; Steketee, J.D.; Saphier, D. Antioxidant Properties of Melatonin—An Emerging Mystery. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998, 56, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocheva, G.; Bakalov, D.; Iliev, P.; Tafradjiiska-Hadjiolova, R. The Vital Role of Melatonin and Its Metabolites in the Neuroprotection and Retardation of Brain Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafati-Chaleshtori, R.; Shirzad, H.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M.; Soltani, A. Melatonin and Human Mitochondrial Diseases. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2017, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urata, Y.; Honma, S.; Goto, S.; Todoroki, S.; Iida, T.; Cho, S.; Honma, K.; Kondo, T. Melatonin Induces γ-Glutamylcysteine Synthetase Mediated by Activator Protein-1 in Human Vascular Endothelial Cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999, 27, 838–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiter, R.J.; Rosales-Corral, S.; Tan, D.X.; Jou, M.J.; Galano, A.; Xu, B. Melatonin as a Mitochondria-Targeted Antioxidant: One of Evolution’s Best Ideas. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 3863–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.X.; Manchester, L.C.; Qin, L.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin: A Mitochondrial Targeting Molecule Involving Mitochondrial Protection and Dynamics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galano, A.; Medina, M.E.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. Melatonin and its Metabolites as Copper Chelating Agents and Their Role in Inhibiting Oxidative Stress: A Physicochemical Analysis. J. Pineal Res. 2015, 58, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galano, A.; Tan, D.X.; Reiter, R.J. On the Free Radical Scavenging Activities of Melatonin’s Metabolites, AFMK and AMK. J. Pineal Res. 2013, 54, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Zhang, Y. Melatonin: A Well-Documented Antioxidant with Conditional pro-Oxidant Actions. J. Pineal Res. 2014, 57, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeggeler, B.; Saarela, S.; Reiter, R.J.; Tan, D.-X.; Chen, L.-D.; Manchester, L.C.; Barlow-Walden, L.R. Melatonin—A Highly Potent Endogenous Radical Scavenger and Electron Donor: New Aspects of the Oxidation Chemistry of This Indole Accessed in Vitro. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 738, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, K.K.A.C.; Shiroma, M.E.; Damous, L.L.; Simões Mde, J.; Simões Rdos, S.; Cipolla-Neto, J.; Baracat, E.C.; Soares-Jr., J.M. Antioxidant Actions of Melatonin: A Systematic Review of Animal Studies. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; An, S.; Fang, H.; Han, Y.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zeng, Z. Melatonin Attenuates Sepsis-Induced Small-Intestine Injury by Upregulating SIRT3-Mediated Oxidative-Stress Inhibition, Mitochondrial Protection, and Autophagy Induction. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 625627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.K.; Chhabra, G.; Ndiaye, M.A.; Garcia-Peterson, L.M.; Mack, N.J.; Ahmad, N. The Role of Sirtuins in Antioxidant and Redox Signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, J. Melatonin Attenuates Anoxia/Reoxygenation Injury by Inhibiting Excessive Mitophagy Through the MT2/SIRT3/FoxO3a Signaling Pathway in H9c2 Cells. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2020, 14, 2047–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Sirianni, A.; Pei, Z.; Cormier, K.; Smith, K.; Jiang, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, R.; Yano, H.; et al. The Melatonin MT1 Receptor Axis Modulates Mutant Huntingtin-Mediated Toxicity. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 14496–14507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahluwalia, A.; Brzozowska, I.M.; Hoa, N.; Jones, M.K.; Tarnawski, A.S. Melatonin Signaling in Mitochondria Extends beyond Neurons and Neuroprotection: Implications for Angiogenesis and Cardio/Gastroprotection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E1942–E1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okatani, Y.; Wakatsuki, A.; Reiter, R.J.; Enzan, H.; Miyahara, Y. Protective Effect of Melatonin against Mitochondrial Injury Induced by Ischemia and Reperfusion of Rat Liver. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 469, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, Y.L.; Ng, K.Y.; Koh, R.Y.; Ponnudurai, G.; Chye, S.M. Melatonin Prevents Oxidative Stress-Induced Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Apoptosis in High Glucose-Treated Schwann Cells via Upregulation of Bcl2, NF-ΚB, MTOR, Wnt Signalling Pathways. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, M.; Ustoyev, Y. Cancer and the Immune System: The History and Background of Immunotherapy. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 35, 150923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillion, S.; Arleevskaya, M.I.; Blanco, P.; Bordron, A.; Brooks, W.H.; Cesbron, J.Y.; Kaveri, S.; Vivier, E.; Renaudineau, Y. The Innate Part of the Adaptive Immune System. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2020, 58, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruterbusch, M.; Pruner, K.B.; Shehata, L.; Pepper, M. In Vivo CD4+ T Cell Differentiation and Function: Revisiting the Th1/Th2 Paradigm. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 38, 705–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zefferino, R.; Di Gioia, S.; Conese, M. Molecular Links between Endocrine, Nervous and Immune System during Chronic Stress. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e01960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühlwein, E.; Irwin, M. Melatonin Modulation of Lymphocyte Proliferation and Th1/Th2 Cytokine Expression. J. Neuroimmunol. 2001, 117, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestroni, G.J.M.; Conti, A.; Pierpaoli, W. Role of the Pineal Gland in Immunity. Circadian Synthesis and Release of Melatonin Modulates the Antibody Response and Antagonizes the Immunosuppressive Effect of Corticosterone. J. Neuroimmunol. 1986, 13, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelzer, I.A.; Arck, P.C. Immunity and the Endocrine System. In Encyclopedia of Immunobiology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 5, pp. 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Su, Y.; Jiao, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B. T Cells in Health and Disease. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrillo-Vico, A.; Lardone, P.J.; Álvarez-Śnchez, N.; Rodrĩguez-Rodrĩguez, A.; Guerrero, J.M. Melatonin: Buffering the Immune System. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 8638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Liu, G.; Chen, S.; Yin, J.; Wang, J.; Tan, B.; Wu, G.; Bazer, F.W.; Peng, Y.; Li, T.; et al. Melatonin Signaling in T Cells: Functions and Applications. J. Pineal Res. 2017, 62, e12394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaji, A.V.; Kulkarni, S.K.; Agrewala, J.N. Regulation of Secretion of IL-4 and IgG1 Isotype by Melatonin-Stimulated Ovalbumin-Specific T Cells. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1998, 111, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Araghi-Niknam, M.; Liang, B.; Inserra, P.; Ardestani, S.K.; Jiang, S.; Chow, S.; Watson, R.R. Prevention of Immune Dysfunction and Vitamin E Loss by Dehydroepiandrosterone and Melatonin Supplementation during Murine Retrovirus Infection. Immunology 1999, 96, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künzli, M.; Masopust, D. CD4+ T Cell Memory. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Sánchez, N.; Cruz-Chamorro, I.; López-González, A.; Utrilla, J.C.; Fernández-Santos, J.M.; Martínez-López, A.; Lardone, P.J.; Guerrero, J.M.; Carrillo-Vico, A. Melatonin Controls Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis by Altering the T Effector/Regulatory Balance. Brain Behav. Immun. 2015, 50, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.; Niu, C.; Sun, C.; Ma, Y.; Guo, R.; Ruan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.; et al. Melatonin Exerts Immunoregulatory Effects by Balancing Peripheral Effector and Regulatory T Helper Cells in Myasthenia Gravis. Aging 2020, 12, 21147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, R.L.E.; Lopera, H.D.E. Introduction to T and B Lymphocytes; El Rosario University Press: Bogota, Colombia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Burrows, P.D.; Wang, J.Y. B Cell Development and Maturation. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 1254, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radogna, F.; Sestili, P.; Martinelli, C.; Paolillo, M.; Paternoster, L.; Albertini, M.C.; Accorsi, A.; Gualandi, G.; Ghibelli, L. Lipoxygenase-Mediated pro-Radical Effect of Melatonin via Stimulation of Arachidonic Acid Metabolism. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 238, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Miller, S.C.; Osmond, D.G. Melatonin Inhibits Apoptosis during Early B-Cell Development in Mouse Bone Marrow. J. Pineal Res. 2000, 29, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Song, J.; Chen, X.; Huang, J.; Lin, X.; Zhou, R. Effect of Melatonin on T/B Cell Activation and Immune Regulation in Pinealectomy Mice. Life Sci. 2020, 242, 117191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Song, R.; Zhang, J.; Yao, J.; Guan, Z.; Zeng, X. Melatonin Enhances NK Cell Function in Aged Mice by Increasing T-Bet Expression via the JAK3-STAT5 Signaling Pathway. Immun. Ageing 2024, 21, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mace, E.M. Human Natural Killer Cells: Form, Function, and Development. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2022, 151, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantoni, C.; Falco, M.; Vitale, M.; Pietra, G.; Munari, E.; Pende, D.; Mingari, M.C.; Sivori, S.; Moretta, L. Human NK Cells and Cancer. Oncoimmunology 2024, 13, 2378520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystel-Whittemore, M.; Dileepan, K.N.; Wood, J.G. Mast Cell: A Multi-Functional Master Cell. Front. Immunol. 2016, 6, 165675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Han, D.; Gu, Q.; Su, R.; Liu, Y.; Reiter, R.J.; Liu, G.; Hu, Y.; et al. Melatonin Alleviates Lung Injury in H1N1-Infected Mice by Mast Cell Inactivation and Cytokine Storm Suppression. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K. Dendritic Cells. Encycl. Cell Biol. 2015, 3, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Hong, Z.J.; Chen, M.F.; Tsai, M.W.; Chen, S.J.; Cheng, C.P.; Sytwu, H.K.; Lin, G.J. Melatonin Inhibits the Formation of Chemically Induced Experimental Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis through Modulation of T Cell Differentiation by Suppressing of NF-ΚB Activation in Dendritic Cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2024, 126, 111300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rungelrath, V.; Kobayashi, S.D.; DeLeo, F.R. Neutrophils in Innate Immunity and Systems Biology-Level Approaches: An Update. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Syst. Biol. Med. 2019, 12, e1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, S.H.; Hsu, H.H.; Huang, S.Y.; Chen, Y.N.; Chen, L.Y.; Lee, A.H.; Lee, A.C.; Lee, E.J. Melatonin Promotes B-Cell Maturation and Attenuates Post-Ischemic Immunodeficiency in a Murine Model of Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia. J. Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2025, 20, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in Immunoregulation and Therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunna, C.; Mengru, H.; Lei, W.; Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 Polarization. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 877, 173090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Tumor Immunity. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 583084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pergañeda, A.; Guerrero, J.M.; Rafii-El-Idrissi, M.; Paz Romero, M.; Pozo, D.; Calvo, J.R. Characterization of Membrane Melatonin Receptor in Mouse Peritoneal Macrophages: Inhibition of Adenylyl Cyclase by a Pertussis Toxin-Sensitive G Protein. J. Neuroimmunol. 1999, 95, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, S.; Zeng, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, C.; Deng, B.; Zhu, G.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W.; Hardeland, R.; et al. Melatonin in Macrophage Biology: Current Understanding and Future Perspectives. J. Pineal Res. 2019, 66, e12547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Choi, W.S. Use of Melatonin in Cancer Treatment: Where Are We? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrey, K.M.; McLachlan, J.A.; Serkin, C.D.; Bakouche, O. Activation of Human Monocytes by the Pineal Hormone Melatonin. J. Immunol. 1994, 153, 2671–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muxel, S.M.; Pires-Lapa, M.A.; Monteiro, A.W.A.; Cecon, E.; Tamura, E.K.; Floeter-Winter, L.M.; Markus, R.P. NF-ΚB Drives the Synthesis of Melatonin in RAW 264.7 Macrophages by Inducing the Transcription of the Arylalkylamine-N-Acetyltransferase (AA-NAT) Gene. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, W.; Pan, K.; Tao, L.; Zhu, Y. Melatonin Induces RAW264.7 Cell Apoptosis via the BMAL1/ROS/MAPK-P38 Pathway to Improve Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Bone Joint Res. 2023, 12, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Today. Available online: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/en/dataviz/bars?types=0_1&mode=population (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Schwartz, S.M. Epidemiology of Cancer. Clin. Chem. 2024, 70, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, S.H.; Dehghani, M. Review of Cancer from Perspective of Molecular. J. Cancer Res. Pract. 2017, 4, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaupel, P.; Multhoff, G.; Bennet, L.; Chan, J.; Vaupel, P.; Multhoff, G.; Physiol, J. Revisiting the Warburg Effect: Historical Dogma versus Current Understanding. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laborda-Illanes, A.; Sánchez-Alcoholado, L.; Castellano-Castillo, D.; Boutriq, S.; Plaza-Andrades, I.; Aranega-Martín, L.; Peralta-Linero, J.; Alba, E.; González-González, A.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I. Development of in Vitro and in Vivo Tools to Evaluate the Antiangiogenic Potential of Melatonin to Neutralize the Angiogenic Effects of VEGF and Breast Cancer Cells: CAM Assay and 3D Endothelial Cell Spheroids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 157, 114041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeppa, L.; Aguzzi, C.; Morelli, M.B.; Marinelli, O.; Amantini, C.; Giangrossi, M.; Santoni, G.; Fanelli, A.; Luongo, M.; Nabissi, M. In Vitro and In Vivo Effects of Melatonin-Containing Combinations in Human Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J. Pineal Res. 2024, 76, e12997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.K.; Lin, Z.; Tidwell, W.J.; Li, W.; Slominski, A.T. Melatonin and Its Metabolites Accumulate in the Human Epidermis in Vivo and Inhibit Proliferation and Tyrosinase Activity in Epidermal Melanocytes in Vitro. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2014, 404, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayahara, G.M.; Valente, V.B.; Pereira, R.B.; Lopes, F.Y.K.; Crivelini, M.M.; Miyahara, G.I.; Biasoli, É.R.; Oliveira, S.H.P.; Bernabé, D.G. Pineal Gland Protects against Chemically Induced Oral Carcinogenesis and Inhibits Tumor Progression in Rats. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 1816–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Q.; Dong, C.; Xu, H.; Khan, B.; Jin, J.; Liu, Q.; Shi, J.; Hou, Y. PD-L1 Degradation Pathway and Immunotherapy for Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Rao, P.G.; Liao, B.Z.; Luo, X.; Yang, W.W.; Lei, X.H.; Ye, J.M. Melatonin Suppresses PD-L1 Expression and Exerts Antitumor Activity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, Y.C.; Lee, K.Y.; Wu, S.M.; Kuo, D.Y.; Shueng, P.W.; Lin, C.W. Melatonin Downregulates Pd-L1 Expression and Modulates Tumor Immunity in Kras-Mutant Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Chen, Y.; Tang, H.; Wang, H.; Jiang, E.; Shao, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhou, X.; Shang, Z. Melatonin Inhibits EMT and PD-L1 Expression through the ERK1/2/FOSL1 Pathway and Regulates Anti-Tumor Immunity in HNSCC. Cancer Sci. 2022, 113, 2232–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Hou, Y.; Long, M.; Jiang, L.; Du, Y. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying the Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 α in Metabolic Reprogramming in Renal Fibrosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 927329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucielo, M.S.; Cesário, R.C.; Silveira, H.S.; Gaiotte, L.B.; Dos Santos, S.A.A.; de Campos Zuccari, D.A.P.; Seiva, F.R.F.; Reiter, R.J.; de Almeida Chuffa, L.G. Melatonin Reverses the Warburg-Type Metabolism and Reduces Mitochondrial Membrane Potential of Ovarian Cancer Cells Independent of MT1 Receptor Activation. Molecules 2022, 27, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Hao, B.; Zhang, M.; Reiter, R.J.; Lin, S.; Zheng, T.; Chen, X.; Ren, Y.; Yue, L.; Abay, B.; et al. Melatonin Enhances Radiofrequency-Induced NK Antitumor Immunity, Causing Cancer Metabolism Reprogramming and Inhibition of Multiple Pulmonary Tumor Development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedighi Pashaki, A.; Sheida, F.; Moaddab Shoar, L.; Hashem, T.; Fazilat-Panah, D.; Nemati Motehaver, A.; Ghanbari Motlagh, A.; Nikzad, S.; Bakhtiari, M.; Tapak, L.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled, Parallel-Group, Trial on the Long-Term Effects of Melatonin on Fatigue Associated with Breast Cancer and Its Adjuvant Treatments. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2023, 22, 15347354231168624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukhopadhyay, N.D.; Khorasanchi, A.; Pandey, S.; Nemani, S.; Parker, G.; Deng, X.; Arthur, D.W.; Urdaneta, A.; Del Fabbro, E. Melatonin Supplementation for Cancer-Related Fatigue in Patients with Early Stage Breast Cancer Receiving Radiotherapy: A Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial. Oncologist 2024, 29, E206–E212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, S.; Cenerini, G.; Lo Giudice, L.; Cruz-Sanabria, F.; Benedetti, D.; Crippa, A.; Fiori, S.; Ferri, R.; Masi, G.; Faraguna, U. Optimizing Timing and Dose of Exogenous Melatonin Administration in Neuropsychiatric Pediatric Populations: A Meta-Analysis on Sleep Outcomes. Sleep Med. Rev. 2025, 84, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickelsen, T.; Demisch, L.; Demisch, K.; Radermacher, B.; Schöffiing, K. Influence of Subchronic Intake of Melatonin at Various Times of the Day on Fatigue and Hormonal Levels: A Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Trial. J. Pineal Res. 1989, 6, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, D.; Gubin, M.M.; Schreiber, R.D.; Smyth, M.J. New Insights into Cancer Immunoediting and Its Three Component Phases —Elimination, Equilibrium and Escape. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2014, 27, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, G.P.; Old, L.J.; Schreiber, R.D. The Immunobiology of Cancer Immunosurveillance and Immunoediting. Immunity 2004, 21, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.-K.; Du, W.-X.; Li, R.-G.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Li, F.; Tan, H.-B. Immune Cells within the Tumor Microenvironment: Biological Functions and Roles in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2020, 470, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The Evolving Tumor Microenvironment: From Cancer Initiation to Metastatic Outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paget, S. The Distribution of Secondary Growths in Cancer of the Breast. Lancet 1889, 133, 571–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, G.; Vescio, G.; De Paola, G.; Sammarco, G. Therapeutic Targets and Tumor Microenvironment in Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, W. Tumor Microenvironment-Mediated Immune Tolerance in Development and Treatment of Gastric Cancer. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1016817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, C.U.; Haining, W.N.; Held, W.; Hogan, P.G.; Kallies, A.; Lugli, E.; Lynn, R.C.; Philip, M.; Rao, A.; Restifo, N.P.; et al. Defining ‘T Cell Exhaustion’. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montauti, E.; Oh, D.Y.; Fong, L. CD4+ T Cells in Antitumor Immunity. Trends Cancer 2024, 10, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.B.; Nixon, M.J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.Y.; Castellanos, E.; Estrada, M.V.; Ericsson-Gonzalez, P.I.; Cote, C.H.; Salgado, R.; Sanchez, V.; et al. Tumor-Specific MHC-II Expression Drives a Unique Pattern of Resistance to Immunotherapy via LAG-3/FCRL6 Engagement. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e120360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talib, W.H.; Alsayed, A.R.; Abuawad, A.; Daoud, S.; Mahmod, A.I. Melatonin in Cancer Treatment: Current Knowledge and Future Opportunities. Molecules 2021, 26, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortezaee, K.; Potes, Y.; Mirtavoos-Mahyari, H.; Motevaseli, E.; Shabeeb, D.; Musa, A.E.; Najafi, M.; Farhood, B. Boosting Immune System against Cancer by Melatonin: A Mechanistic Viewpoint. Life Sci. 2019, 238, 116960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, F.; Casares, N.; Martín-Otal, C.; Lasarte-Cía, A.; Gorraiz, M.; Sarrión, P.; Llopiz, D.; Reparaz, D.; Varo, N.; Rodriguez-Madoz, J.R.; et al. Overcoming T Cell Dysfunction in Acidic PH to Enhance Adoptive T Cell Transfer Immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 2022, 11, 2070337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrzadi, S.; Pourhanifeh, M.H.; Mirzaei, A.; Moradian, F.; Hosseinzadeh, A. An Updated Review of Mechanistic Potentials of Melatonin against Cancer: Pivotal Roles in Angiogenesis, Apoptosis, Autophagy, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Oxidative Stress. Cancer Cell Int. 2021, 21, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs-Canner, S.M.; Meier, J.; Vincent, B.G.; Serody, J.S. B Cell Function in the Tumor Microenvironment. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 40, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousalova, I.; Krepela, E. Granzyme B-Induced Apoptosis in Cancer Cells and Its Regulation (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2010, 37, 1361–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrén, I.; Orrantia, A.; Vitallé, J.; Zenarruzabeitia, O.; Borrego, F. NK Cell Metabolism and Tumor Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillerey, C. NK Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1273, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curti, A.; Ruggeri, L.; D’Addio, A.; Bontadini, A.; Dan, E.; Motta, M.R.; Trabanelli, S.; Giudice, V.; Urbani, E.; Martinelli, G.; et al. Successful Transfer of Alloreactive Haploidentical KIR Ligand-Mismatched Natural Killer Cells after Infusion in Elderly High Risk Acute Myeloid Leukemia Patients. Blood 2011, 118, 3273–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, L.; Saxena, S.; Singh, R.K. Neutrophils in the Tumor Microenvironment. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1224, pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadas, A.K.; Dilmac, S.; Aytac, G.; Tanriover, G. Melatonin Decreases Metastasis, Primary Tumor Growth and Angiogenesis in a Mice Model of Breast Cancer. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2021, 40, 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, K.; Shi, H.; Zhang, B.; Ou, X.; Ma, Q.; Chen, Y.; Shu, P.; Li, D.; Wang, Y. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells as Immunosuppressive Regulators and Therapeutic Targets in Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Chen, J. Melatonin: A Natural Guardian in Cancer Treatment. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1617508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, I.; Manic, G.; Coussens, L.M.; Kroemer, G.; Galluzzi, L. Macrophages and Metabolism in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cell Metab. 2019, 30, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yue, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, C.; Wu, W.; Zhang, N.; Liu, Z.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Cheng, Q.; et al. Define Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) in the Tumor Microenvironment: New Opportunities in Cancer Immunotherapy and Advances in Clinical Trials. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Shi, K.; Fu, M.; Chen, F. Melatonin Indirectly Decreases Gastric Cancer Cell Proliferation and Invasion via Effects on Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Life Sci. 2021, 277, 119497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, J.-J.; Xu, D.-P.; Li, H.-B. Melatonin for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 39896–39921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haston, S.; Gonzalez-Gualda, E.; Morsli, S.; Ge, J.; Reen, V.; Calderwood, A.; Moutsopoulos, I.; Panousopoulos, L.; Deletic, P.; Carreno, G.; et al. Clearance of Senescent Macrophages Ameliorates Tumorigenesis in KRAS-Driven Lung Cancer. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 1242–1260.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumitomo, R.; Hirai, T.; Fujita, M.; Murakami, H.; Otake, Y.; Huang, C.-L. M2 Tumor-Associated Macrophages Promote Tumor Progression in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 18, 4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Luo, J.; Guo, W.; Sun, L.; Lin, L. Targeting M2-like Tumor-Associated Macrophages Is a Potential Therapeutic Approach to Overcome Antitumor Drug Resistance. NPJ Precis. Oncol. 2024, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Tang, Z.; Huang, H.; Zhou, G.; Cui, C.; Weng, Y.; Liu, W.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Perez-Neut, M.; et al. Metabolic Regulation of Gene Expression by Histone Lactylation. Nature 2019, 574, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Zhu, B. Metabolic Regulatory Crosstalk between Tumor Microenvironment and Tumor-Associated Macrophages. Theranostics 2021, 11, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmatirad, S.; Moloudizargari, M.; Fallah, M.; Rahimi, A.; Poortahmasebi, V.; Asghari, M.H. Cancer-Associated Immune Cells and Their Modulation by Melatonin. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2023, 45, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhuang, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, X.; Yu, X.; Tao, J.; Liu, X. Melatonin-Mediated CGAS-STING Signal in Senescent Macrophages Promote TNBC Chemotherapy Resistance and Drive the SASP. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 108438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.K.; Bakhoum, S.F. The Cytosolic DNA-Sensing CGAS-STING Pathway in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2020, 10, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioli, C.; Caroleo, M.C.; Nistico’, G.; Doriac, G. Melatonin Increases Antigen Presentation and Amplifies Specific and Non Specific Signals for T-Cell Proliferation. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1993, 15, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, C.; Tao, Z.; Zhu, W.; Su, Y.; Choi, W.S. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Facilitate Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas Migration and Invasion by MIF/NLRP3/IL-1β Circuit: A Crosstalk Interrupted by Melatonin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2023, 1869, 166695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Syeda, S.; Rawat, K.; Kumari, R.; Shrivastava, A. Melatonin Modulates L-Arginine Metabolism in Tumor-Associated Macrophages by Targeting Arginase 1 in Lymphoma. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2024, 397, 1163–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, K.M.R.; França, D.C.H.; de Queiroz, A.A.; Fagundes-Triches, D.L.G.; de Marchi, P.G.F.; Morais, T.C.; Honorio-França, A.C.; França, E.L. Polarization of Melatonin-Modulated Colostrum Macrophages in the Presence of Breast Tumor Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Cai, R.; Fei, S.; Chen, X.; Feng, S.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Song, J.; Zhou, R. Melatonin Enhances Anti-Tumor Immunity by Targeting Macrophages PD-L1 via Exosomes Derived from Gastric Cancer Cells. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2023, 568, 111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Qureshi, M.Z.; Tahir, F.; Yilmaz, S.; Romero, M.A.; Attar, R.; Farooqi, A.A. Role of Melatonin in Carcinogenesis and Metastasis: From Mechanistic Insights to Intermeshed Networks of Noncoding RNAs. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2024, 42, e3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, G.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, M.; Niu, Y.; Sun, L.; Li, W.; Xia, H.; Lin, H.; Guo, Z.; Du, G. The Combination of LPS and Melatonin Induces M2 Macrophage Apoptosis to Prevent Lung Cancer. Explor. Res. Hypothesis Med. 2022, 7, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lavado-Fernández, E.; Pérez-Montes, C.; Robles-García, M.; Santos-Ledo, A.; García-Macia, M. Melatonin at the Crossroads of Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Cancer Therapy. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010064

Lavado-Fernández E, Pérez-Montes C, Robles-García M, Santos-Ledo A, García-Macia M. Melatonin at the Crossroads of Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Cancer Therapy. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleLavado-Fernández, Elena, Cristina Pérez-Montes, Miguel Robles-García, Adrián Santos-Ledo, and Marina García-Macia. 2026. "Melatonin at the Crossroads of Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Cancer Therapy" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010064

APA StyleLavado-Fernández, E., Pérez-Montes, C., Robles-García, M., Santos-Ledo, A., & García-Macia, M. (2026). Melatonin at the Crossroads of Oxidative Stress, Immunity, and Cancer Therapy. Antioxidants, 15(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010064