Experimental Models of Acute Lung Injury to Study Inflammation and Pathophysiology: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

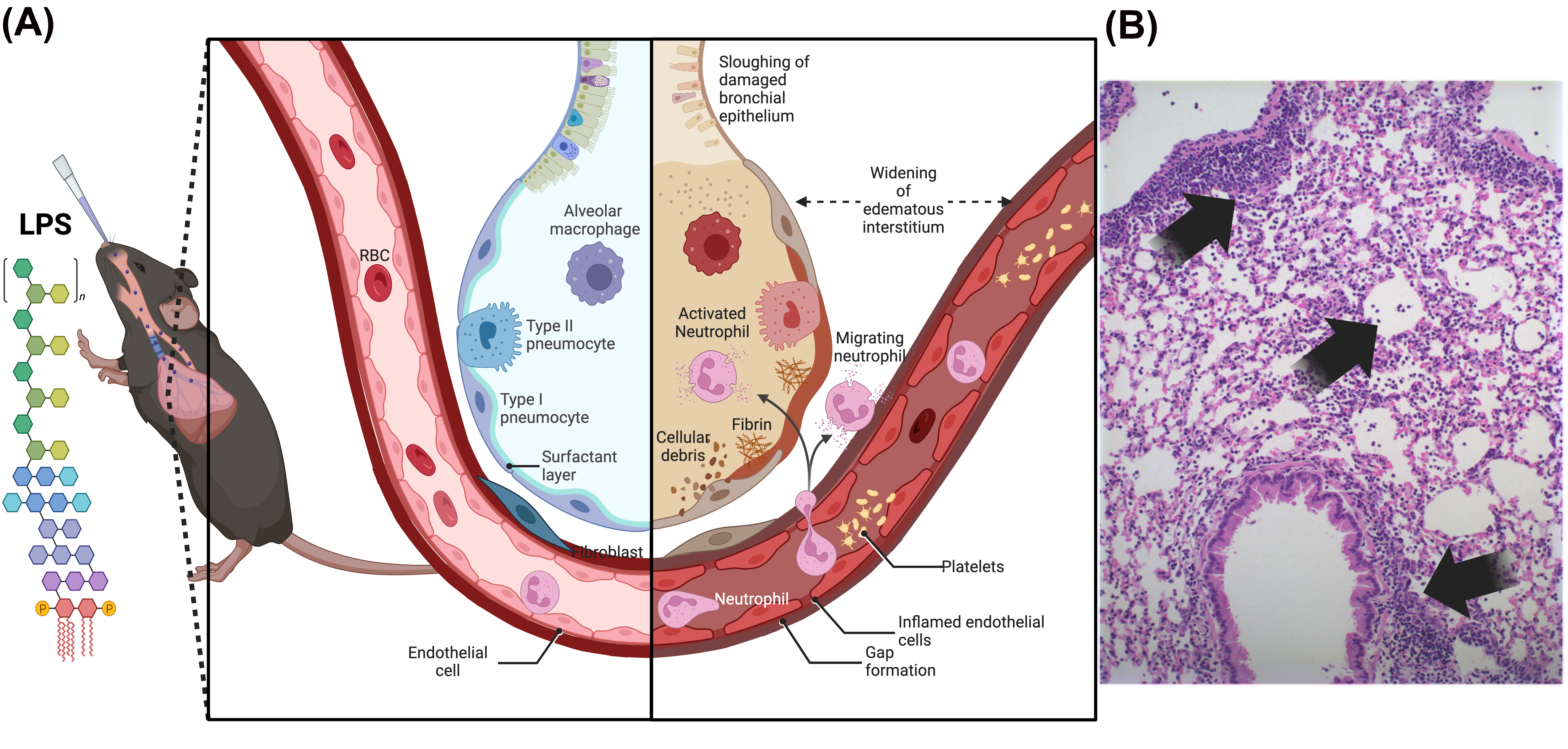

2. LPS (Lipopolysaccharide)-Induced Lung Injury Model

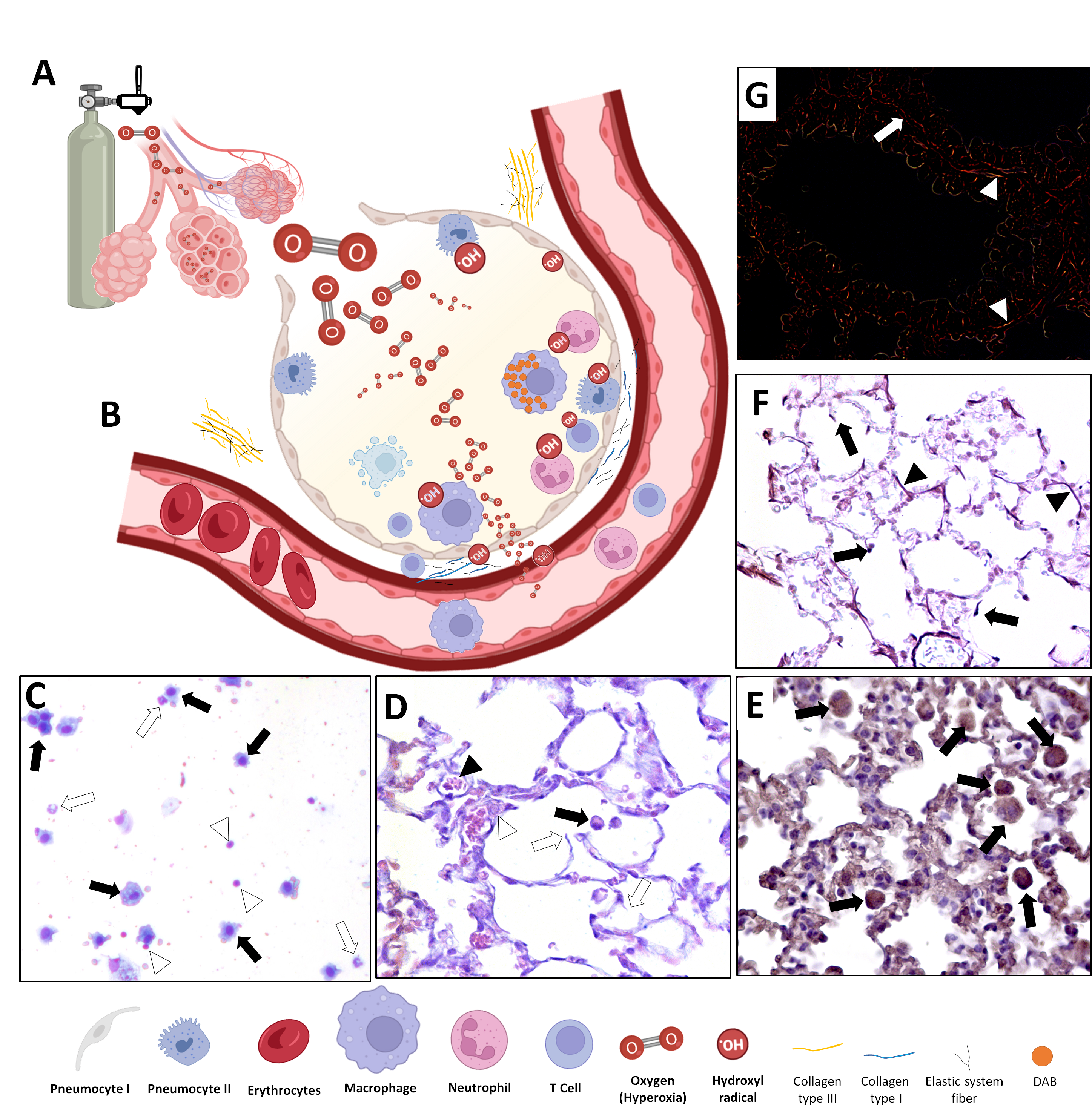

3. In Vivo Animal Model of Hyperoxic-Induced Oxidative Stress

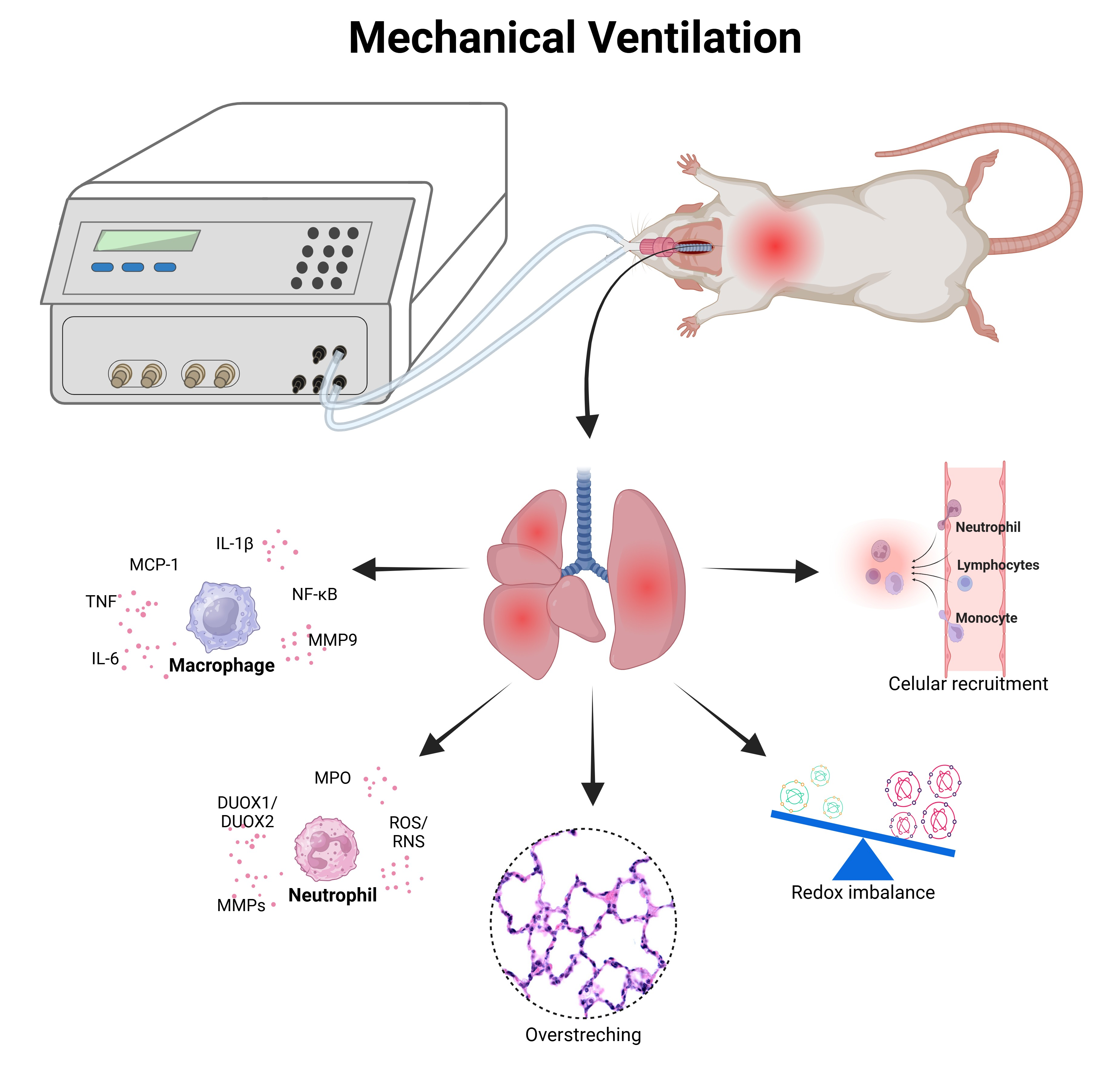

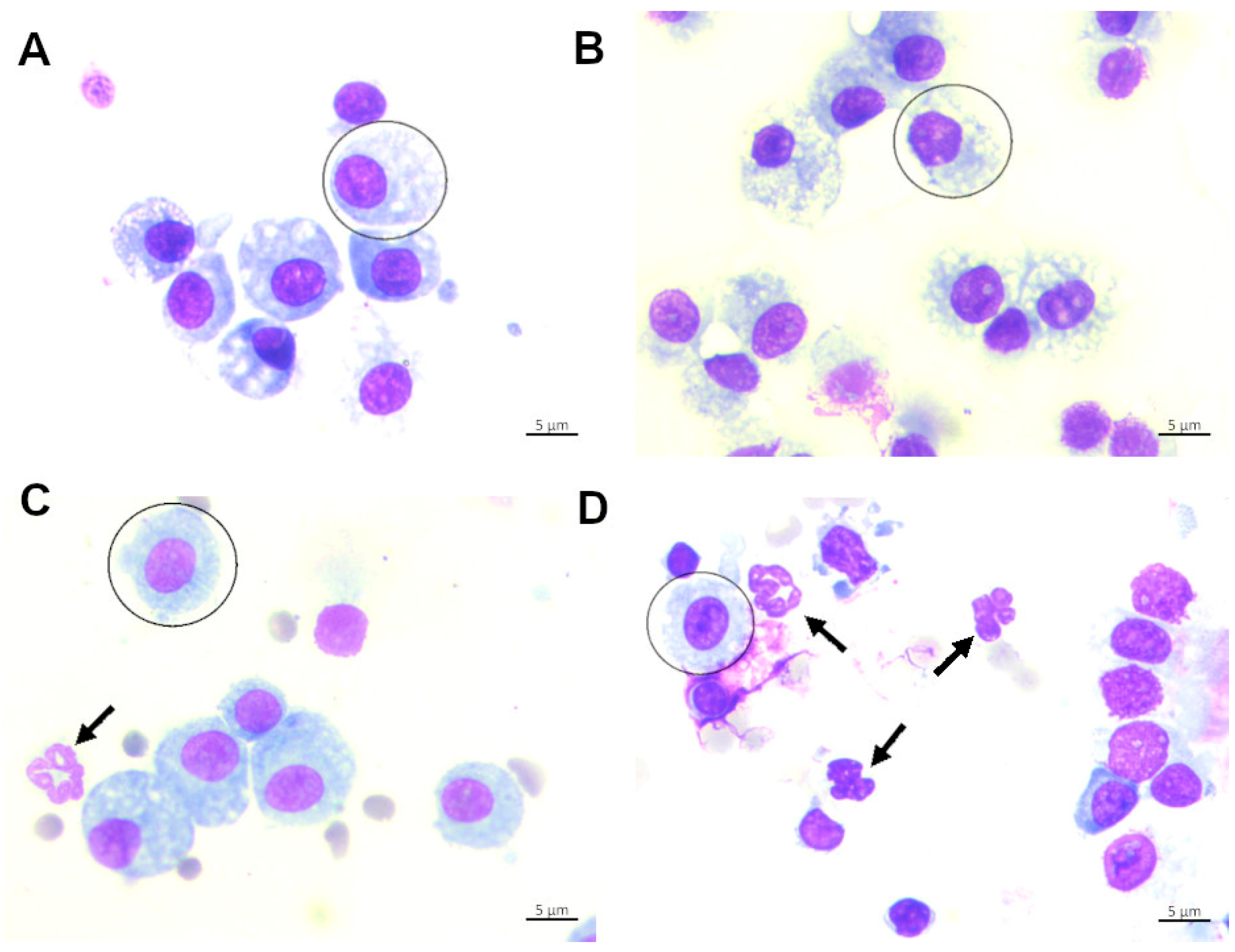

4. Experimental Models of Ventilator-Induced Lung Injury Model (VILI)

| Animal Models | Type of Injury | Dose | Route |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guinea-pigs | Physiological saline | 35 mL/kg [88] | Intratracheal |

| Mongrel dogs | Oleic acid | 0.06 mL/kg [89] | Intravenous |

| Mongrel dogs | Detergent dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate | 1.5 mg/kg [90] | Aerosolization |

| New Zealand white rabbits | Warm normal saline | 30 mL/kg [91] | Intratracheal |

| Mongrel dogs | Hydrochloric acid | 0.5 mL/kg [92] | Intratracheal |

| New Zealand white rabbits | Hydrochloric acid | 2.25 mL/kg [93] | Intratracheal |

| New Zealand white rabbits | Detergent dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate | 3.8 mg/kg [94] | Intratracheal |

| New Zealand white rabbits | Warm normal saline | 30 mL/kg [95] | Intratracheal |

| Wistar rats | α-naphthylthiourea | 1.3 mg/kg [96] | Intravenous |

| Yorkshire pigs | Warm saline solution | 50 mL/kg [97] | Intratracheal |

| Wistar rats | Paraquat | 15 mg/kg [98] | Intraperitoneally |

| Yorkshire pigs | Warmed saline 0.9% | 30 mL/kg [99] | Intratracheal |

| Wistar rats | Lipopolysaccharide | 200 μL [100] | Intratracheal |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALI | Acute lung injury |

| AECs | Alveolar epithelial cells |

| ARDS | Acute respiratory distress syndrome |

| BAL | Bronchoalveolar lavage |

| CAT | Catalase |

| GAGs | Glycosaminoglycans |

| GPx | Glutathione peroxidase |

| HMGB1 | High-mobility group box-1 |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MV | Mechanical ventilation |

| NOS | Nitrogen species |

| PEEP | Positive end-expiratory pressure |

| RBCs | Red blood cells |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| VILI | Ventilator-induced lung injury |

References

- Bhargava, M.; Wendt, C.H. Biomarkers in acute lung injury. Transl. Res. 2012, 159, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokra, D. Acute lung injury—From pathophysiology to treatment. Physiol. Res. 2020, 69, S353–S366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Fan, E.K.; Fan, J. Cell-Cell Interaction Mechanisms in Acute Lung Injury. Shock 2021, 55, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yu, X.; Yu, S.; Kou, J. Molecular mechanisms in lipopolysaccharide-induced pulmonary endothelial barrier dysfunction. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 29, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, Y.; Kurdowska, A.; Allen, T.C. Acute Lung Injury: A Clinical and Molecular Review. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2016, 140, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, J.; Lin, J.; Zakaria, N.; Yahaya, B.H. Acute Lung Injury: Disease Modelling and the Therapeutic Potential of Stem Cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1298, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matute-Bello, G.; Frevert, C.W.; Martin, T.R. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2008, 295, L379–L399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Dai, Q.; Huang, X. Neutrophils in acute lung injury. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 2012, 17, 2278–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Bai, C.; Wang, X. The value of the lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury model in respiratory medicine. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2010, 4, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarelle, L.; Quintela, L.; Hurtado, J.; Malacrida, L. Hyperoxia and Lungs: What We Have Learned From Animal Models. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 606678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, J.H.T.; Smith, B.J. Ventilator-induced lung injury and lung mechanics. Ann. Transl. Med. 2018, 6, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, H. Inhibiting toll-like receptor 4 signaling ameliorates pulmonary fibrosis during acute lung injury induced by lipopolysaccharide: An experimental study. Respir. Res. 2009, 10, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togbe, D.; Schnyder-Candrian, S.; Schnyder, B.; Doz, E.; Noulin, N.; Janot, L.; Secher, T.; Gasse, P.; Lima, C.; Coelho, F.R.; et al. Toll-like receptor and tumour necrosis factor dependent endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2007, 88, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, R.C.; Garcia, C.C.; Teixeira, M.M. Anti-inflammatory drug development: Broad or specific chemokine receptor antagonists? Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Dev. 2010, 13, 414–427. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, R.C.; Garcia, C.C.; Teixeira, M.M.; Amaral, F.A. The CXCL8/IL-8 chemokine family and its receptors in inflammatory diseases. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2014, 10, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reutershan, J.; Chang, D.; Hayes, J.K.; Ley, K. Protective effects of isoflurane pretreatment in endotoxin-induced lung injury. Anesthesiology 2006, 104, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarbock, A.; Allegretti, M.; Ley, K. Therapeutic inhibition of CXCR2 by Reparixin attenuates acute lung injury in mice. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 155, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, R.C.; Guabiraba, R.; Garcia, C.C.; Barcelos, L.S.; Roffe, E.; Souza, A.L.; Amaral, F.A.; Cisalpino, D.; Cassali, G.D.; Doni, A.; et al. Role of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 in bleomycin-induced pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2009, 40, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gschwandtner, M.; Strutzmann, E.; Teixeira, M.M.; Anders, H.J.; Diedrichs-Mohring, M.; Gerlza, T.; Wildner, G.; Russo, R.C.; Adage, T.; Kungl, A.J. Glycosaminoglycans are important mediators of neutrophilic inflammation in vivo. Cytokine 2017, 91, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boff, D.; Russo, R.C.; Crijns, H.; de Oliveira, V.L.S.; Mattos, M.S.; Marques, P.E.; Menezes, G.B.; Vieira, A.T.; Teixeira, M.M.; Proost, P.; et al. The Therapeutic Treatment with the GAG-Binding Chemokine Fragment CXCL9(74-103) Attenuates Neutrophilic Inflammation and Lung Dysfunction during Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deban, L.; Russo, R.C.; Sironi, M.; Moalli, F.; Scanziani, M.; Zambelli, V.; Cuccovillo, I.; Bastone, A.; Gobbi, M.; Valentino, S.; et al. Regulation of leukocyte recruitment by the long pentraxin PTX3. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilter, H.C.; Collison, A.; Russo, R.C.; Foot, J.S.; Yow, T.T.; Vieira, A.T.; Tavares, L.D.; Mattes, J.; Teixeira, M.M.; Jarolimek, W. Effects of an anti-inflammatory VAP-1/SSAO inhibitor, PXS-4728A, on pulmonary neutrophil migration. Respir. Res. 2015, 16, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, A.S.; Li, K.; Chen, H.; Wang, D.; Andersson, R.; Wang, X. Variation of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in eight strains of mice. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2010, 171, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, A.S.; Li, K.; Yang, D.; Andersson, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X. Varying susceptibility of pulmonary cytokine production to lipopolysaccharide in mice. Cytokine 2010, 49, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, K.W. Oxygen poisoning in man. Br. Med. J. 1947, 1, 667; passim. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severinghaus, J.W. Priestley, the furious free thinker of the enlightenment, and Scheele, the taciturn apothecary of Uppsala. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2002, 46, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, A.; Lavania, A.K. Oxygen Toxicity. Med. J. Armed Forces India 2001, 57, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donald, K.W. Oxygen poisoning in man; signs and symptoms of oxygen poisoning. Br. Med. J. 1947, 1, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, G.S.; Burch, L.H.; Berman, K.G.; Piantadosi, C.A.; Schwartz, D.A. Genetic basis of murine responses to hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Immunogenetics 2006, 58, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prows, D.R.; Hafertepen, A.P.; Gibbons, W.J., Jr.; Winterberg, A.V.; Nick, T.G. A genetic mouse model to investigate hyperoxic acute lung injury survival. Physiol. Genom. 2007, 30, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillbe, C.E.; Salt, J.C.; Branthwaite, M.A. Pulmonary function after prolonged mechanical ventilation with high concentrations of oxygen. Thorax 1980, 35, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkove, S.; Dhamapurkar, R.; Cui, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, J.; Cooper, D.; Eichacker, P.Q.; Torabi-Parizi, P. Effect of low-to-moderate hyperoxia on lung injury in preclinical animal models: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2023, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckl, C.; Kaestle, S.; Kerem, A.; Habazettl, H.; Krombach, F.; Kuppe, H.; Kuebler, W.M. Hyperoxia-induced reactive oxygen species formation in pulmonary capillary endothelial cells in situ. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2006, 34, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, L.P.; Delfino, F.C.; Faria, F.P.; Melo, G.F.; Carvalho Gde, A. Adequacy of oxygenation parameters in elderly patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. Einstein 2013, 11, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, L.B.; Matthay, M.A. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1334–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Driscoll, B.R.; Howard, L.S.; Davison, A.G.; British Thoracic, S. BTS guideline for emergency oxygen use in adult patients. Thorax 2008, 63, vi1–vi68, Erratum in Thorax 2008, 63, A8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, H.; Russell, D.J. Oxygen concentrations in tents and incubators in paediatric practice. Br. Med. J. 1967, 4, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bateman, N.T.; Leach, R.M. ABC of oxygen. Acute oxygen therapy. Br. Med. J. 1998, 317, 798–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagodich, T.A.; Bersenas, A.M.E.; Bateman, S.W.; Kerr, C.L. High-flow nasal cannula oxygen therapy in acute hypoxemic respiratory failure in 22 dogs requiring oxygen support escalation. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2020, 30, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, K.A.; Lane, N.L. Effect of in vivo hyperoxia on the glutathione system in neonatal rat lung. Exp. Lung Res. 1994, 20, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.W.; Ghezzi, P.; McMahon, S.; Dinarello, C.A.; Repine, J.E. Cytokines increase rat lung antioxidant enzymes during exposure to hyperoxia. J. Appl. Physiol. 1989, 66, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, J.H.; Codipilly, C.N.; Nasim, S.; Miller, E.J.; Ahmed, M.N. Synergistic protection against hyperoxia-induced lung injury by neutrophils blockade and EC-SOD overexpression. Respir. Res. 2012, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerurkar, L.S.; Zeligs, B.J.; Bellanti, J.A. Changes in superoxide dismutase, catalase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activities of rabbit alveolar macrophages: Induced by postnatal maturation and/or in vitro hyperoxia. Photochem. Photobiol. 1978, 28, 781–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, T.; Niu, C.; Sun, S.; Liu, D. ROS-activated MAPK/ERK pathway regulates crosstalk between Nrf2 and Hif-1alpha to promote IL-17D expression protecting the intestinal epithelial barrier under hyperoxia. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 116, 109763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrikov, D.; Elms, S.; Fulton, D.; Su, Y. eNOS-beta-actin interaction contributes to increased peroxynitrite formation during hyperoxia in pulmonary artery endothelial cells and mouse lungs. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 35479–35487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsotakos, N.; Ahmed, I.; Umstead, T.M.; Imamura, Y.; Yau, E.; Silveyra, P.; Chroneos, Z.C. All trans-retinoic acid modulates hyperoxia-induced suppression of NF-kB-dependent Wnt signaling in alveolar A549 epithelial cells. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, G.L.; Menendez, I.Y.; Ryan, M.A.; Mazor, R.L.; Wispe, J.R.; Fiedler, M.A.; Wong, H.R. Hyperoxia synergistically increases TNF-alpha-induced interleukin-8 gene expression in A549 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2000, 278, L253–L260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Li, X.; Wan, Q.; Han, W.; Deng, C.; Guo, C. High-Mobility Group Box-1 Protein Disrupts Alveolar Elastogenesis of Hyperoxia-Injured Newborn Lungs. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2016, 36, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Li, S.; Bai, W.; Li, Z.; Lou, F. Artesunate Alleviates Hyperoxia-Induced Lung Injury in Neonatal Mice by Inhibiting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2023, 2023, 7603943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turanlahti, M.; Pesonen, E.; Lassus, P.; Andersson, S. Nitric oxide and hyperoxia in oxidative lung injury. Acta Paediatr. 2000, 89, 966–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, S.; Pang, H.; Foster, D.C.; Rao, Z.; Wu, M. Human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase increases resistance to hyperoxic cytotoxicity in lung epithelial cells and involvement with altered MAPK activity. Cell Death Differ. 2006, 13, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Yuan, T.; Guo, X.; Jin, C.; Jin, Z.; Li, J. Glutamine inhibits inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis and ameliorates hyperoxic lung injury. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 79, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chang, L.W.; Li, W.B. Temporal expression and significance of caspase-3 and interleukin-8 in the lungs of preterm rats exposed to hyperoxia. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2008, 46, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner, C.; Wu, J.; Soto-Gonzalez, L.; Kaun, C.; Stojkovic, S.; Wojta, J.; Tretter, V.; Markstaller, K.; Klein, K.U. Moderate hyperoxia induces inflammation, apoptosis and necrosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: An in-vitro study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2017, 34, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagato, A.C.; Bezerra, F.S.; Talvani, A.; Aarestrup, B.J.; Aarestrup, F.M. Hyperoxia promotes polarization of the immune response in ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation, leading to a TH17 cell phenotype. Immun. Inflamm. Dis. 2015, 3, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, F.S.; Lanzetti, M.; Nesi, R.T.; Nagato, A.C.; Silva, C.P.E.; Kennedy-Feitosa, E.; Melo, A.C.; Cattani-Cavalieri, I.; Porto, L.C.; Valenca, S.S. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Acute and Chronic Lung Injuries. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyfuss, D.; Saumon, G. Ventilator-induced lung injury: Lessons from experimental studies. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 157, 294–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grune, J.; Tabuchi, A.; Kuebler, W.M. Alveolar dynamics during mechanical ventilation in the healthy and injured lung. Intensive Care Med. Exp. 2019, 7, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goligher, E.C.; Ferguson, N.D.; Brochard, L.J. Clinical challenges in mechanical ventilation. Lancet 2016, 387, 1856–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouza, C.; Martinez-Ales, G.; Lopez-Cuadrado, T. Recent trends of invasive mechanical ventilation in older adults: A nationwide population-based study. Age Ageing 2021, 50, 1607–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, C.C.; Slutsky, A.S. Invited review: Mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury: A perspective. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 89, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbaugh, D.G.; Bigelow, D.B.; Petty, T.L.; Levine, B.E. Acute respiratory distress in adults. Lancet 1967, 2, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, H.H.; Tierney, D.F. Experimental pulmonary edema due to intermittent positive pressure ventilation with high inflation pressures. Protection by positive end-expiratory pressure. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1974, 110, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, L.J.; Ebert, P.A.; Benson, D.W. Effect of Positive Pressure Ventilation on Surface Tension Properties of Lung Extracts. Anesthesiology 1964, 25, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, E.; Ermocilla, R.; Golden, J.; McDevitt, M.; Cassady, G. Effects of intermittent positive-pressure ventilation on lungs of normal rabbits. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1980, 61, 315–323. [Google Scholar]

- Kolobow, T.; Moretti, M.P.; Fumagalli, R.; Mascheroni, D.; Prato, P.; Chen, V.; Joris, M. Severe impairment in lung function induced by high peak airway pressure during mechanical ventilation. An experimental study. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1987, 135, 312–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.C.; Hernandez, L.A.; Longenecker, G.L.; Peevy, K.; Johnson, W. Lung edema caused by high peak inspiratory pressures in dogs. Role of increased microvascular filtration pressure and permeability. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990, 142, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuno, K.; Prato, P.; Kolobow, T. Acute lung injury from mechanical ventilation at moderately high airway pressures. J. Appl. Physiol. 1990, 69, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlton, D.P.; Cummings, J.J.; Scheerer, R.G.; Poulain, F.R.; Bland, R.D. Lung overexpansion increases pulmonary microvascular protein permeability in young lambs. J. Appl. Physiol. 1990, 69, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M.R.; Takata, M. Inflammatory mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury: A time to stop and think? Anaesthesia 2013, 68, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, N.; Brower, R.G.; Matthay, M.A.; Morris, A.; Schoenfeld, D.; Thompson, B.T.; Wheeler, A. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 1301–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, P.L.; Negrini, D.; Rocco, P.R. Mechanisms of ventilator-induced lung injury in healthy lungs. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2015, 29, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugin, J.; Verghese, G.; Widmer, M.C.; Matthay, M.A. The alveolar space is the site of intense inflammatory and profibrotic reactions in the early phase of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 1999, 27, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRitchie, D.I.; Isowa, N.; Edelson, J.D.; Xavier, A.M.; Cai, L.; Man, H.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Keshavjee, S.H.; Slutsky, A.S.; Liu, M. Production of tumour necrosis factor alpha by primary cultured rat alveolar epithelial cells. Cytokine 2000, 12, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spieth, P.M.; Bluth, T.; Gama De Abreu, M.; Bacelis, A.; Goetz, A.E.; Kiefmann, R. Mechanotransduction in the lungs. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014, 80, 933–941. [Google Scholar]

- Davidovich, N.; DiPaolo, B.C.; Lawrence, G.G.; Chhour, P.; Yehya, N.; Margulies, S.S. Cyclic stretch-induced oxidative stress increases pulmonary alveolar epithelial permeability. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiuza, C.; Bustin, M.; Talwar, S.; Tropea, M.; Gerstenberger, E.; Shelhamer, J.H.; Suffredini, A.F. Inflammation-promoting activity of HMGB1 on human microvascular endothelial cells. Blood 2003, 101, 2652–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grommes, J.; Soehnlein, O. Contribution of neutrophils to acute lung injury. Mol. Med. 2011, 17, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Vliet, A. NADPH oxidases in lung biology and pathology: Host defense enzymes, and more. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 938–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, M.; Lomas-Neira, J.; Venet, F.; Chung, C.S.; Ayala, A. Pathogenesis of indirect (secondary) acute lung injury. Expert. Rev. Respir. Med. 2011, 5, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, S.P.; Hassoun, P.M.; Brower, R. Redox imbalance and ventilator-induced lung injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal 2007, 9, 2003–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.C.; Souza, A.B.F.; Horta, J.G.; Paula Costa, G.; Talvani, A.; Cangussu, S.D.; Menezes, R.C.A.; Bezerra, F.S. Applying Positive End-Expiratory Pressure During Mechanical Ventilation Causes Pulmonary Redox Imbalance and Inflammation in Rats. Shock 2018, 50, 572–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, A.B.F.; Chirico, M.T.T.; Cartelle, C.T.; de Paula Costa, G.; Talvani, A.; Cangussu, S.D.; de Menezes, R.C.A.; Bezerra, F.S. High-Fat Diet Increases HMGB1 Expression and Promotes Lung Inflammation in Mice Subjected to Mechanical Ventilation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 7457054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, A.C.L.; de Matos, N.A.; de Souza, A.B.F.; Castro, T.F.; Candido, L.D.S.; Oliveira, M.; Costa, G.P.; Talvani, A.; Cangussu, S.D.; Bezerra, F.S. Sigh maneuver protects healthy lungs during mechanical ventilation in adult Wistar rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 1404–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candido, L.D.S.; de Matos, N.A.; Castro, T.F.; de Paula, L.C.; Dos Santos, A.M.; Costa, G.P.; Talvani, A.; Cangussu, S.D.; Zin, W.A.; Bezerra, F.S. Different Tidal Volumes May Jeopardize Pulmonary Redox and Inflammatory Status in Healthy Rats Undergoing Mechanical Ventilation. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2021, 2021, 5196896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.R.; Horta, J.G.A.; de Matos, N.A.; de Souza, A.B.F.; Castro, T.F.; Candido, L.D.S.; Andrade, M.C.; Cangussu, S.D.; Costa, G.P.; Talvani, A.; et al. The effects of different ventilatory modes in female adult rats submitted to mechanical ventilation. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2021, 284, 103583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, A.B.F.; de Matos, N.A.; Castro, T.F.; Costa, G.P.; Oliveira, L.A.M.; Nogueira, K.; Ribeiro, I.M.L.; Talvani, A.; Cangussu, S.D.; de Menezes, R.C.A.; et al. Effects in vitro and in vivo of hesperidin administration in an experimental model of acute lung inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022, 180, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachmann, B.; Robertson, B.; Vogel, J. In vivo lung lavage as an experimental model of the respiratory distress syndrome. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 1980, 24, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luce, J.M.; Huang, T.W.; Robertson, H.T.; Colley, P.S.; Gronka, R.; Nessly, M.L.; Cheney, F.W. The effects of prophylactic expiratory positive airway pressure on the resolution of oleic acid-induced lung injury in dogs. Ann. Surg. 1983, 197, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, G.F.; Bredenberg, C.E. High surface tension pulmonary edema induced by detergent aerosol. J. Appl. Physiol. 1985, 58, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, P.R.; Forkert, P.G.; Froese, A.B. Lung volume maintenance prevents lung injury during high frequency oscillatory ventilation in surfactant-deficient rabbits. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1988, 137, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbridge, T.C.; Wood, L.D.; Crawford, G.P.; Chudoba, M.J.; Yanos, J.; Sznajder, J.I. Adverse effects of large tidal volume and low PEEP in canine acid aspiration. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990, 142, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohma, A.; Brampton, W.J.; Dunnill, M.S.; Sykes, M.K. Effect of ventilation with positive end-expiratory pressure on the development of lung damage in experimental acid aspiration pneumonia in the rabbit. Intensive Care Med. 1992, 18, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coker, P.J.; Hernandez, L.A.; Peevy, K.J.; Adkins, K.; Parker, J.C. Increased sensitivity to mechanical ventilation after surfactant inactivation in young rabbit lungs. Crit. Care Med. 1992, 20, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiura, M.; McCulloch, P.R.; Wren, S.; Dawson, R.H.; Froese, A.B. Ventilator pattern influences neutrophil influx and activation in atelectasis-prone rabbit lung. J. Appl. Physiol. 1994, 77, 1355–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyfuss, D.; Soler, P.; Saumon, G. Mechanical ventilation-induced pulmonary edema. Interaction with previous lung alterations. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1995, 151, 1568–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunst, P.W.; Bohm, S.H.; Vazquez de Anda, G.; Amato, M.B.; Lachmann, B.; Postmus, P.E.; de Vries, P.M. Regional pressure volume curves by electrical impedance tomography in a model of acute lung injury. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 28, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaro, C.P.; Silva, P.L.; Rzezinski, A.F.; Abrantes, S.; Santiago, V.R.; Nardelli, L.; Santos, R.S.; Barbosa, C.M.; Morales, M.M.; Zin, W.A.; et al. Pulmonary lesion induced by low and high positive end-expiratory pressure levels during protective ventilation in experimental acute lung injury. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 37, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katira, B.H.; Osada, K.; Engelberts, D.; Bastia, L.; Damiani, L.F.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Yoshida, T.; Amato, M.B.P.; Ferguson, N.D.; et al. Positive End-Expiratory Pressure, Pleural Pressure, and Regional Compliance during Pronation: An Experimental Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 1266–1274, Erratum in Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 204, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, P.H.; Fonseca, A.C.F.; Goncalves, L.A.; de Sousa, G.C.; Silva, M.C.D.; Sacramento, R.F.M.; Samary, C.D.S.; Medeiros, M.; Cruz, F.F.; Capelozzi, V.L.; et al. Lung Injury Is Induced by Abrupt Increase in Respiratory Rate but Prevented by Recruitment Maneuver in Mild Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Rats. Anesthesiology 2023, 138, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slutsky, A.S.; Ranieri, V.M. Ventilator-induced lung injury. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2126–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nagato, A.C.; Machado-Junior, P.A.; Valenca, S.S.; Russo, R.C.; Bezerra, F.S. Experimental Models of Acute Lung Injury to Study Inflammation and Pathophysiology: A Narrative Review. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010063

Nagato AC, Machado-Junior PA, Valenca SS, Russo RC, Bezerra FS. Experimental Models of Acute Lung Injury to Study Inflammation and Pathophysiology: A Narrative Review. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010063

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagato, Akinori Cardozo, Pedro Alves Machado-Junior, Samuel Santos Valenca, Remo Castro Russo, and Frank Silva Bezerra. 2026. "Experimental Models of Acute Lung Injury to Study Inflammation and Pathophysiology: A Narrative Review" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010063

APA StyleNagato, A. C., Machado-Junior, P. A., Valenca, S. S., Russo, R. C., & Bezerra, F. S. (2026). Experimental Models of Acute Lung Injury to Study Inflammation and Pathophysiology: A Narrative Review. Antioxidants, 15(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010063