A Neutral Polysaccharide from Ginseng Berry Mitigates D-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Stress and Cognitive Deficits Through the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 Pathway

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Chemicals

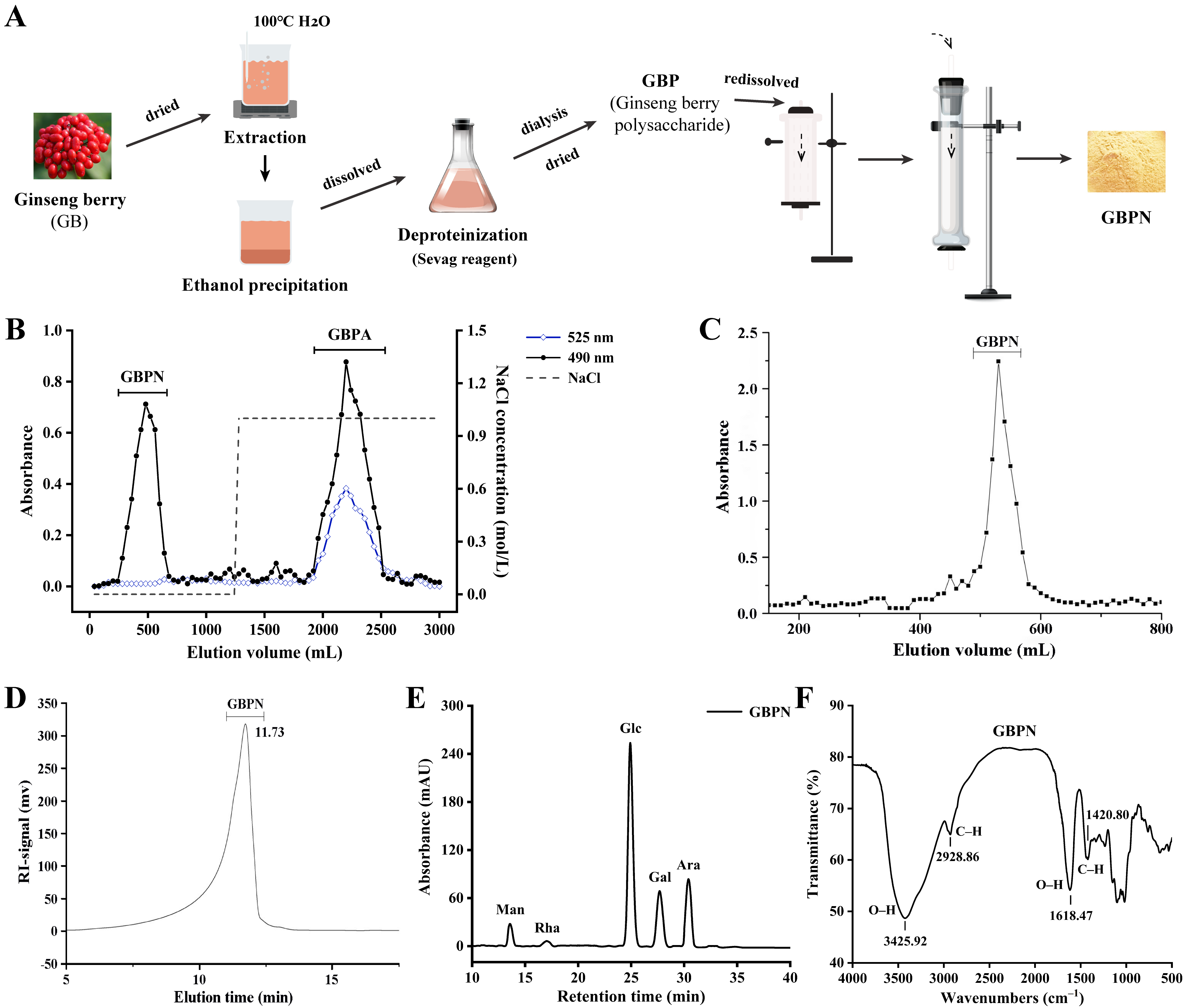

2.2. Extraction, Separation, and Purification of GBPN

2.3. Analysis of the Structural Characterization of GBPN

2.3.1. Determination of Homogeneity and Molecular Weight of GBPN

2.3.2. Monosaccharide Component Analysis of GBPN

2.3.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis of GBPN

2.3.4. Methylation and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis of GBPN

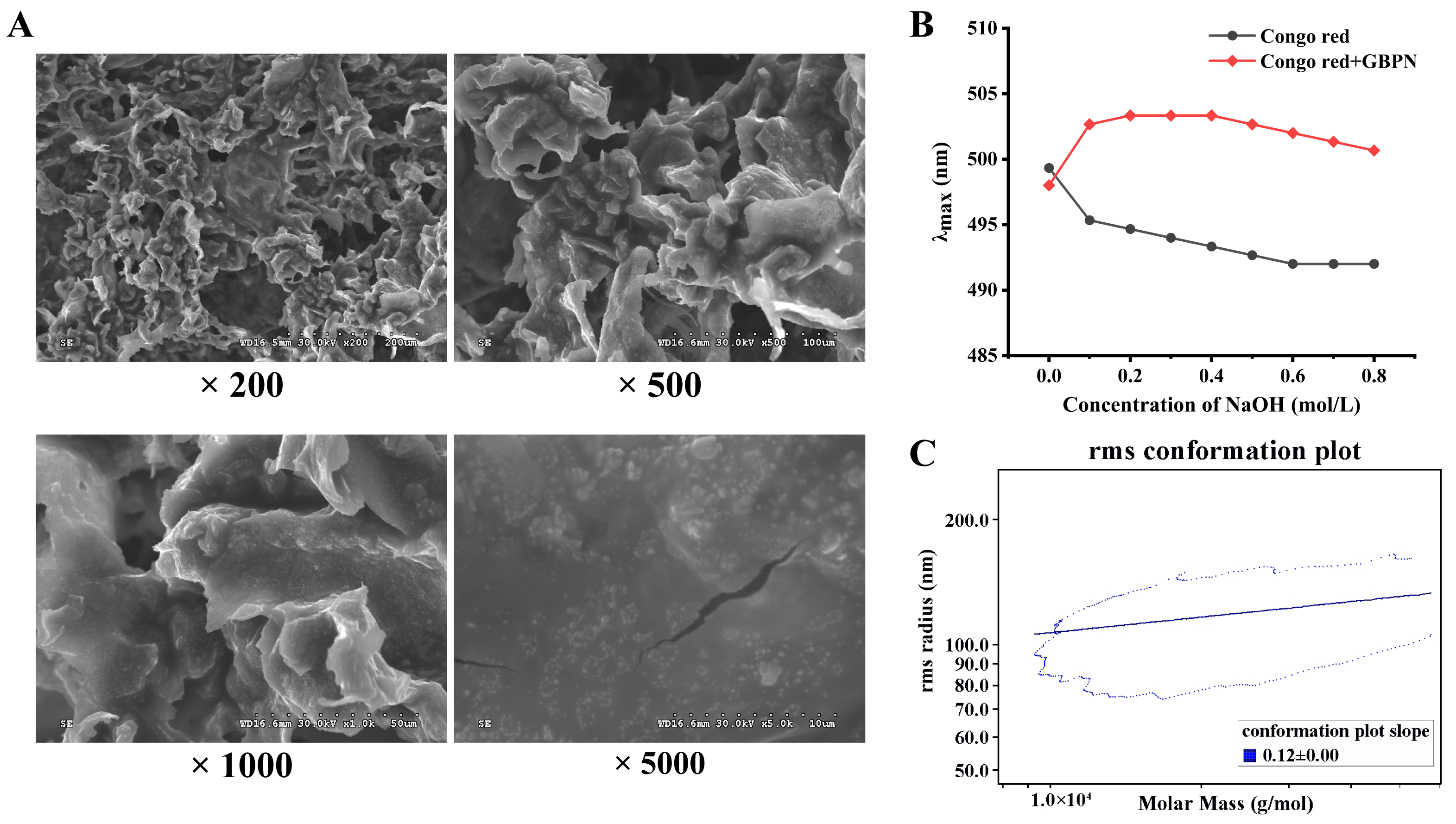

2.3.5. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Observation

2.3.6. Conformational Characteristics Analysis

2.4. Determination of Antioxidant Capacity In Vitro

2.4.1. Assay for DPPH Radical Scavenging Activity

2.4.2. Assay for Hydroxyl Radical (•OH) Scavenging Activity

2.4.3. Assay for Ferrous Ion Chelating Ability

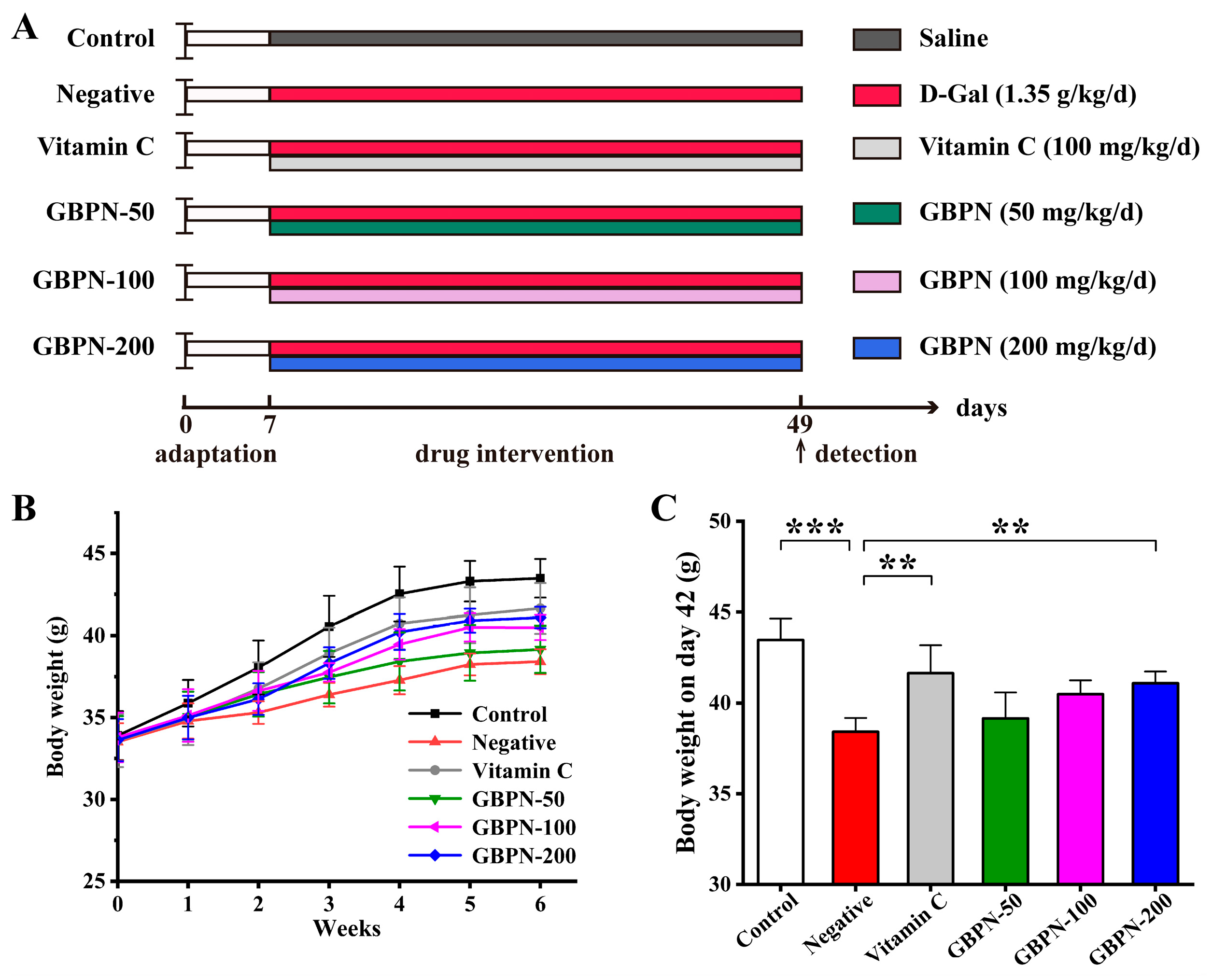

2.5. Evaluation of In Vivo Antioxidant and Anti-Brain Aging Activities

2.5.1. Animals and Treatment

2.5.2. Analysis of Oxidative Stress Indicators

2.5.3. Morris Water Maze (MWM) Test

2.5.4. Mechanism Analysis

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation and Purification of GBPN

3.2. Structural Characterization of GBPN

3.2.1. Primary Structural Characterization

3.2.2. Morphology and Conformation Analysis of GBPN

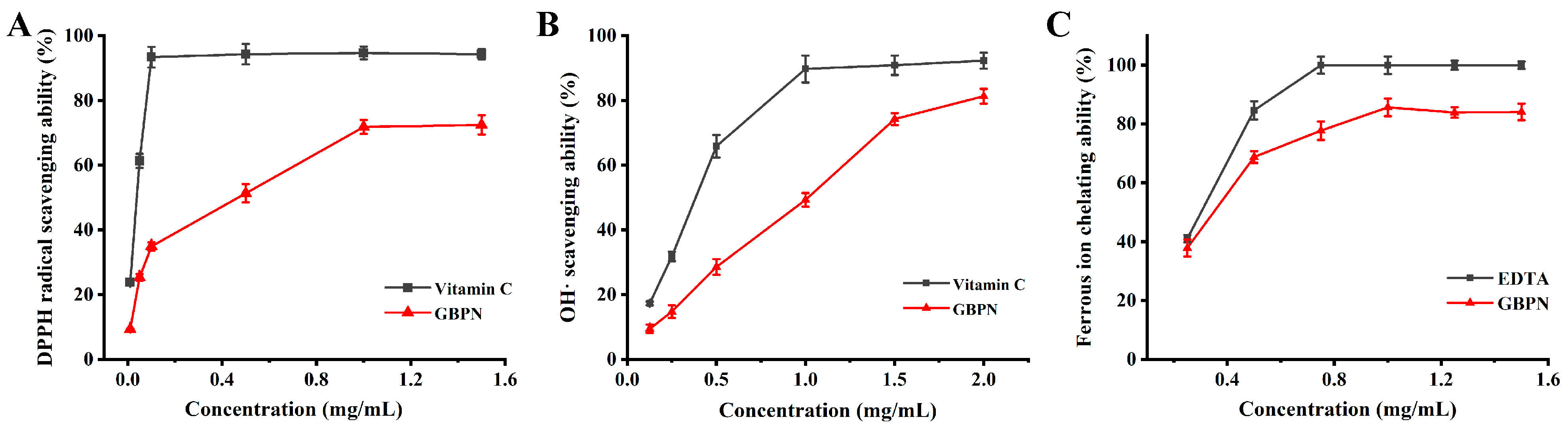

3.3. Antioxidant Activities of GBPN In Vitro

3.3.1. DPPH Radical Scavenging Ability

3.3.2. •OH Scavenging Ability

3.3.3. Ferrous Ion Chelating Ability

3.4. Effect of GBPN on D-Gal Induced Aged Mice

3.4.1. GBPN Improves Body Weight in D-Gal-Induced Aged Mice

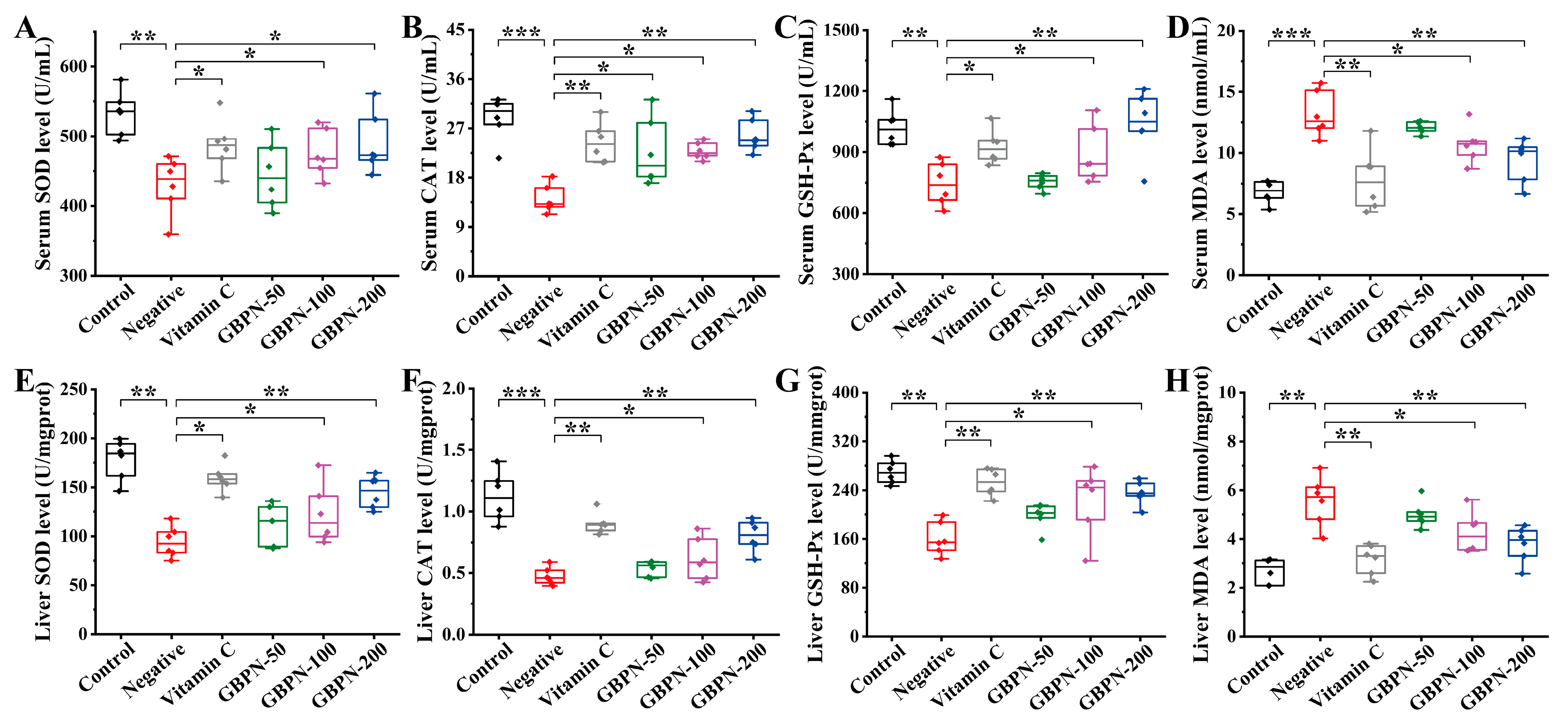

3.4.2. GBPN Downregulated Oxidative Stress Levels in D-Gal-Induced Aging-like Mice

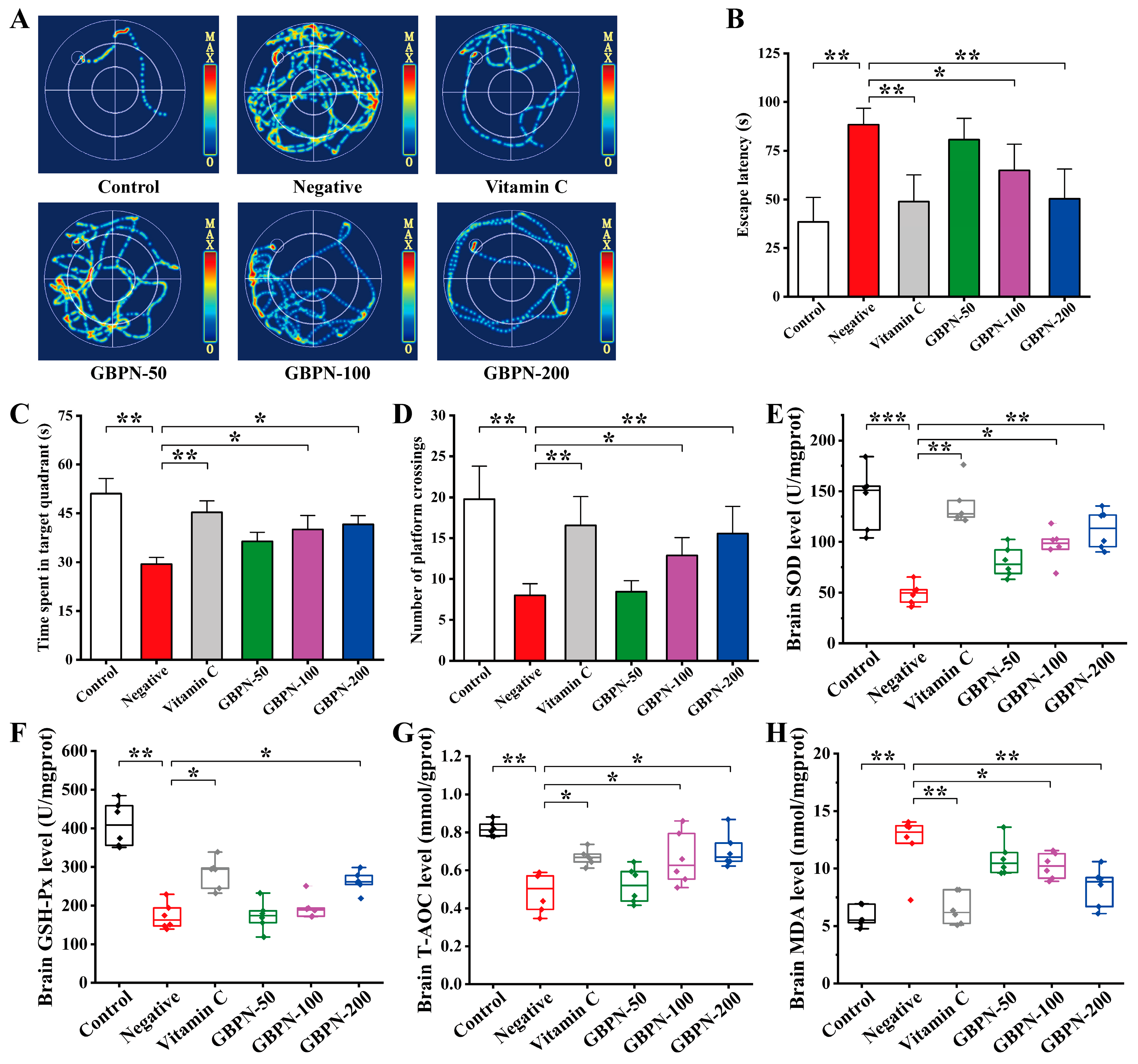

3.4.3. GBPN Ameliorates Spatial Memory Dysfunction and Brain Oxidative Stress Injury in D-Gal-Induced Mice

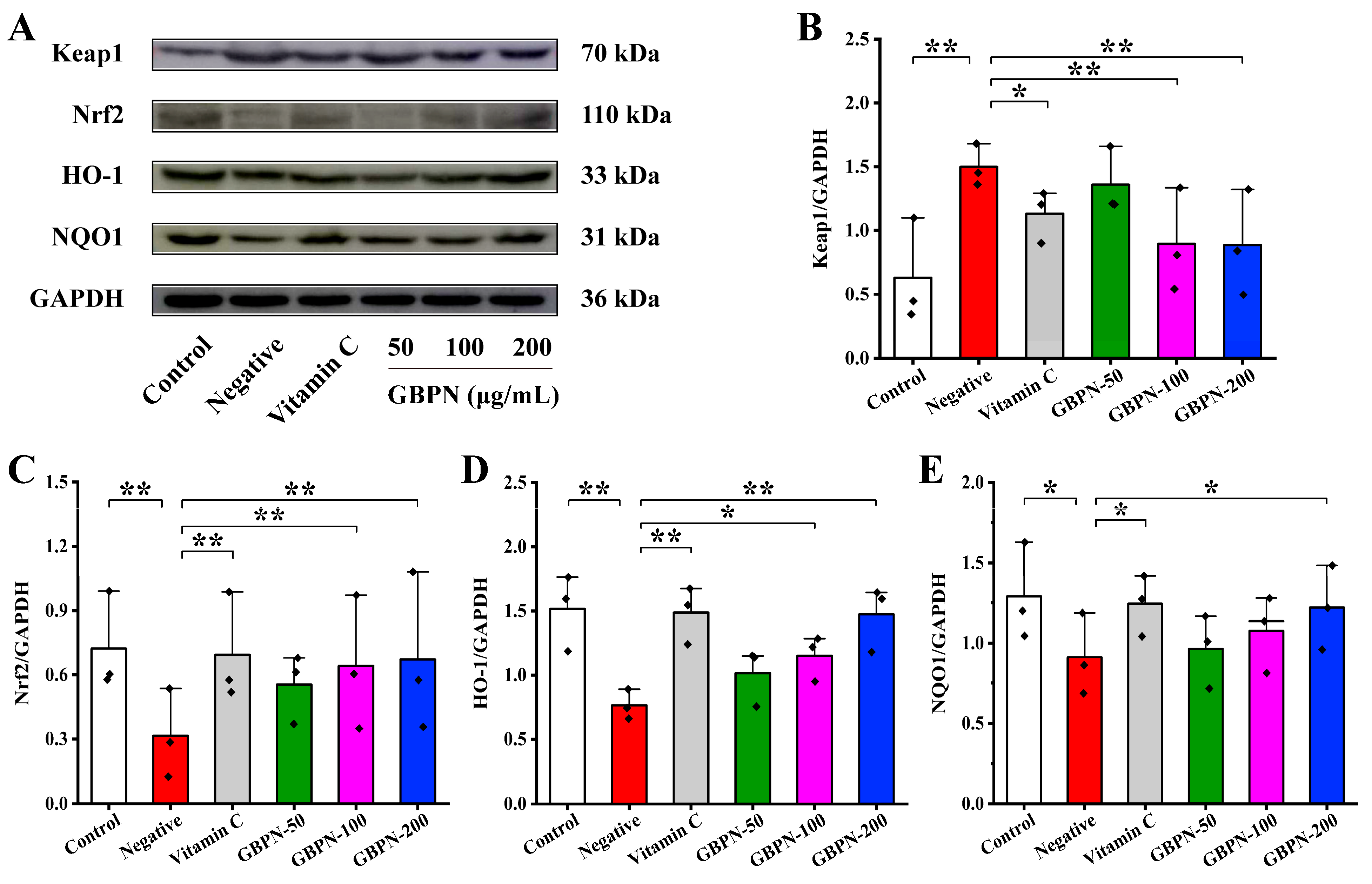

3.4.4. Association of GBPN with the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 Pathway in D-Gal-Induced Mice

3.4.5. Limitations of the Study

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Ara | Arabinose |

| CAT | Catalase |

| D-gal | D-Galactose |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| FT-IR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| Gal | Galactose |

| GB | Ginseng berry |

| GBP | Ginseng berry crude polysaccharide |

| GBPN | Ginseng berry neutral polysaccharide |

| GC-MS | Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry |

| Glc | Glucose |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione peroxidase |

| HO-1 | Heme oxygenase 1 |

| HPGPC | High-performance gel permeation chromatography |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| Keap1 | Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MWM | Morris water maze |

| NQO1 | NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1 |

| Nrf2 | Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| PMP | 1-phenyl-3-methyl-5-pyrazolone |

| PMAAs | Partially methylated alditol acetates |

| Rha | Rhamnose |

| SEC-MALLS | Size exclusion chromatography-multi-angle laser light scattering |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| T-AOC | Total antioxidant capacity |

References

- Stancu, A.; Khan, A.; Barratt, J. Driving the Life Course Approach to Vaccination through the Lens of Key Global Agendas. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1200397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Mills, K.; le Cessie, S.; Noordam, R.; van Heemst, D. Ageing, Age-Related Diseases and Oxidative Stress: What to Do Next? Ageing Res. Rev. 2020, 57, 100982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.J.; Chen, K.C.; Yin, J.Y.; Zheng, Y.N.; Chen, R.X.; Liu, W.; Tang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Z.; et al. AFG, an Important Maillard Reaction Product in Red Ginseng, Alleviates D-Galactose-Induced Brain Aging in Mice via Correcting Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induced by ROS Accumulation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 952, 175824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Hagberg, C.E.; Silva Cascales, H.; Lang, S.; Hyvonen, M.T.; Salehzadeh, F.; Chen, P.; Alexandersson, I.; Terezaki, E.; Harms, M.J.; et al. Obesity and Hyperinsulinemia Drive Adipocytes to Activate a Cell Cycle Program and Senesce. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partridge, L.; Fuentealba, M.; Kennedy, B.K. The Quest to Slow Ageing through Drug Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 19, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Hao, F. Advances in Natural Polysaccharides in Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease: Insights from the Brain-Gut Axis. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 153, 104678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Ren, T.; Gao, P.; Li, N.; Wu, Z.; Xia, J.; Jia, X.; Yuan, L.; Jiang, P. Characterization and Anti-Aging Effects of Polysaccharide from Gomphus clavatus Gray. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246, 125706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Fayyaz, S.; Zhao, D.; Yi, Z.; Huang, J.-h.; Zhou, R.-r.; Xie, J.; Liu, P.-a.; He, W.; Zhang, S.-h.; et al. Polygonatum sibiricum Polysaccharides Improve Cognitive Function in D-Galactose-Induced Aging Mice by Regulating the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. J. Funct. Foods 2023, 103, 105476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, M.; Wang, G.; Han, L. Atractylodes macrocephala Polysaccharides Shield a D-Galactose-Induced Aging Model via Gut Microbiota Modulation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Jiang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhou, L.; Ge, Y.; Yang, Z. Pseudostellaria heterophylla Polysaccharide Mitigates Alzheimer’s-Like Pathology via Regulating the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in 5× FAD Mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Zhu, G.; Zhang, J. Ginseng in Delaying Brain Aging: Progress and Perspectives. Phytomedicine 2025, 140, 156587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant Arya, R.K.; Kausar, M.; Bisht, D.; Keservani, R.K.; Kumar, A. Memory-boosting fruits and foods for elderly. In Nutraceutical Fruits and Foods for Neurodegenerative Disorders; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, D.; Chen, K.; Zhang, J.; Hou, Y.; Gao, X.; Cai, E.; Zhu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, R.; et al. Based on Molecular Docking to Evaluate the Protective Effect of Saponins from Ginseng Berry on D-gal-induced Brain Injury via Multiple Molecular Mechanisms in Mice. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 97, 105224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Giani, A.; Oldani, M.; Forcella, M.; Lasagni, M.; Fusi, P.; Di Gennaro, P. Synergistic Antioxidant Effect of Prebiotic Ginseng Berries Extract and Probiotic Strains on Healthy and Tumoral Colorectal Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yi, Y.S.; Kim, J.; Han, S.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Seo, D.B.; Cho, J.Y.; Shin, S.S. Effect of Polysaccharides from a Korean Ginseng Berry on the Immunosenescence of Aged Mice. J. Ginseng Res. 2018, 42, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, T.; Xu, M.; Zhou, S.; Ren, J.; Li, B.; Jiang, P.; Li, H.; Wu, W.; Chen, C.; Fan, M.; et al. Structural Characteristics of Mixed Pectin from Ginseng Berry and Its Anti-Obesity Effects by Regulating the Intestinal Flora. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Chen, J.; Liu, R.; Song, D.; Li, W.; Lin, N.; Zou, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Purification, Characterization, and In Vitro Antitumor Activity of a Novel Glucan from the Purple Sweet Potato Ipomoea Batatas (L.) Lam. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 257, 117605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Bi, C.; Shi, H.; Li, X. Structural Studies of a Mannoglucan from Cremastra appendiculata (Orchidaceae) by Chemical and Enzymatic Methods. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 272, 118524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Zhou, L.; Mou, Y.; Mao, Z. Extraction Optimization of Polysaccharide from Zanthoxylum bungeanum Using RSM and Its Antioxidant Activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 72, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Xiang, J.; Zheng, G.; Yan, R.; Min, X. Preliminary Characterization and Anti-Hyperglycemic Activity of a Pectic Polysaccharide from Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench). J. Funct. Foods 2018, 41, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Qiang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zou, J.; Niu, J.; Wang, Z. Structural Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of Polygonatum sibiricum Polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 291, 119524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Yan, H.; Feng, Y.; Cui, L.; Hussain, H.; Park, J.H.; Kwon, S.W.; Xie, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Characterization of the Structure, Anti-Inflammatory Activity and Molecular Docking of a Neutral Polysaccharide Separated from American Ginseng Berries. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, M.; Shi, T.; Monto, A.R.; Yuan, L.; Jin, W.; Gao, R. Enhancement of the Gelling Properties of Aristichthys nobilis: Insights into Intermolecular Interactions between Okra Polysaccharide and Myofibrillar Protein. Curr. Res. Food 2024, 9, 100814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, N.; Wang, D.X.; Jiao, L.; Tan, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wu, W.; Jiang, D.C. Structural Analysis and Antioxidant Activities of Neutral Polysaccharide Isolated from Epimedium koreanum Nakai. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 196, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, X.; Dong, Y.; Song, R.; Wei, J.; Yu, A.; Fan, Q.; Yao, J.; Shan, D.; Lv, F.; et al. Preparation, Structural Analysis, Antioxidant and Digestive Enzymes Inhibitory Activities of Polysaccharides from Thymus quinquecostatus Celak. Leaves. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2022, 175, 114288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Piao, C.; Yu, H.; Liu, J.; Li, Z. Structural Characterization of Polysaccharides after Fermentation from Ganoderma lucidum and Its Antioxidant Activity in HepG2 Cells Induced by H2O2. Food Chem. X 2023, 18, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Wu, J.; Shen, L.; Chen, G.; Jin, L.; Yan, M.; Wan, H.; He, Y. Microwave Assisted Extraction, Characterization of a Polysaccharide from Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge and Its Antioxidant Effects via Ferroptosis-Mediated Activation of the Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 215, 398–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Hou, J.; Liu, F.; Liu, W. Characterization, Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activity of Neutral Polysaccharides from Oyster (Crassostrea rivularis). LWT 2024, 212, 116961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Zheng, Q.; Duan, Y.; Cai, M.; Zhang, H. Effect of Subcritical Water Temperature on the Structure, Antioxidant Activity and Immune Activity of Polysaccharides from Glycyrrhiza inflata Batalin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Abdullah, M.F. Extraction of Polysaccharide Fraction from Cadamba (Neolamarckia cadamba) Fruits and Evaluation of Its In Vitro and In Vivo Antioxidant Activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bu, Y.; Yin, B.; Qiu, Z.; Li, L.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, Z.; Li, M. Structural Characterization and Antioxidant Activities of Polysaccharides Extracted from Polygonati rhizoma Pomace. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Li, J.; Liu, F.; Wang, J.; Jiang, P.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Chen, C.; Wu, W. Characterisation, Chain Conformation and Antifatigue Effect of Steamed Ginseng Polysaccharides with Different Molecular Weight. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 712836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandi, S.; Charles, A.L. Statistical Comparative Study between the Conventional DPPH Spectrophotometric and Dropping DPPH Analytical Method without Spectrophotometer: Evaluation for the Advancement of Antioxidant Activity Analysis. Food Chem. 2019, 287, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, A.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Xiong, B. Polysaccharide from Paris polyphylla Improves Learning and Memory Ability in D-galactose-induced Aging Model Mice Based on Antioxidation, p19/p53/p21, and Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 251, 126311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Yao, H.; Xiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Xiao, M.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, H.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Effect of Angelica Polysaccharide on Brain Senescence of Nestin-GFP Mice Induced by D-Galactose. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 122, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Guo, P.; Jin, Y.; Li, M.; Hu, X.; Wang, W.; Wei, X.; Qi, S. Momordica charantia Polysaccharide Ameliorates D-Galactose-Induced Aging through the Nrf2/Beta-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Metab. Brain Dis. 2023, 38, 1067–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Hu, M.; Jiang, T.; Xiao, P.; Duan, J.A. Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms, Structure-Activity Relationships and Application Prospects of Polysaccharides by Regulating Nrf2-Mediated Antioxidant Response. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 333, 122003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, X.; Luo, H.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Xia, L.; Ni, M.; Wang, J.; Peng, C.; Wu, X.; Tan, R.; et al. Structural Characterization, Anti-Aging Activity and Mechanisms Investigation In Vivo of a Polysaccharide from Anthriscus sylvestris. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, W.; Ding, C. Aronia melanocarpa Polysaccharide Ameliorates Inflammation and Aging in Mice by Modulating the AMPK/SIRT1/NF-kappaB Signaling Pathway and Gut Microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Time | PMAAs | Linkage Type | Molar Ratios (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13.49 | 2,3,5-Me3-Araf | →1)-Araf | 9.73 |

| 14.44 | 2,3,4-Me3-Arap | →1)-Arap | 5.82 |

| 15.73 | 3,4-Me2-Arap | →2)-Arap-(1→ | 0.66 |

| 16.37 | 2,3-Me2-Araf | →5)-Araf-(1→ | 7.62 |

| 17.23 | 2,3,4,6-Me4-Manp | →1)-Manp | 4.86 |

| 17.67 | 2,3,4,6-Me4-Galp | →1)-Galp | 3.58 |

| 18.04 | 2-Me1-Araf | →3,5)-Araf-(1→ | 1.69 |

| 18.27 | 3-Me1-Rhap | →2,4)-Rhap-(1→ | 1.34 |

| 19.13 | 2,3,6-Me3-Glcp | →4)-Glcp-(1→ | 32.95 |

| 19.80 | 2,4,6-Me3-Galp | →3)-Galp-(1→ | 1.59 |

| 20.13 | 2,3,4-Me3-Galp | →6)-Glcp-(1→ | 13.81 |

| 21.34 | 2,3-Me2-Galp | →4,6)-Glcp-(1→ | 3.70 |

| 21.82 | 2,4-Me2-Galp | →3,6)-Galp-(1→ | 12.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ren, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Song, R.; Li, X.; Gao, J.; Sun, X.; Jiao, L. A Neutral Polysaccharide from Ginseng Berry Mitigates D-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Stress and Cognitive Deficits Through the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 Pathway. Antioxidants 2026, 15, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010065

Ren T, Wang L, Zhang J, Song R, Li X, Gao J, Sun X, Jiao L. A Neutral Polysaccharide from Ginseng Berry Mitigates D-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Stress and Cognitive Deficits Through the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 Pathway. Antioxidants. 2026; 15(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Ting, Lina Wang, Jiaxin Zhang, Ruitong Song, Xin Li, Jiayue Gao, Xin Sun, and Lili Jiao. 2026. "A Neutral Polysaccharide from Ginseng Berry Mitigates D-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Stress and Cognitive Deficits Through the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 Pathway" Antioxidants 15, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010065

APA StyleRen, T., Wang, L., Zhang, J., Song, R., Li, X., Gao, J., Sun, X., & Jiao, L. (2026). A Neutral Polysaccharide from Ginseng Berry Mitigates D-Galactose-Induced Oxidative Stress and Cognitive Deficits Through the Keap1/Nrf2/HO-1/NQO1 Pathway. Antioxidants, 15(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox15010065