Multi-Stage Topology Optimization for Structural Redesign of Railway Motor Bogie Frames

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology and Benchmark Description

2.1. Methodology

- (1)

- A high-fidelity finite element (FE) model of the bogie frame was developed, including all equipment supports and the fundamental load interfaces required to properly reproduce the interactions with adjacent and interconnected subsystems;

- (2)

- A complete mechanical assessment was performed, covering both static and fatigue verification in accordance with the applicable European standards. This step was followed by an extensive sensitivity analysis aimed at improving the efficiency and robustness of the computational procedure;

- (3)

- A first topology optimization analysis was conducted on the entire design volume available for the bogie frame. A comprehensive numerical testing campaign was carried out to identify the optimal optimization settings capable of delivering results aligned with the project objectives;

- (4)

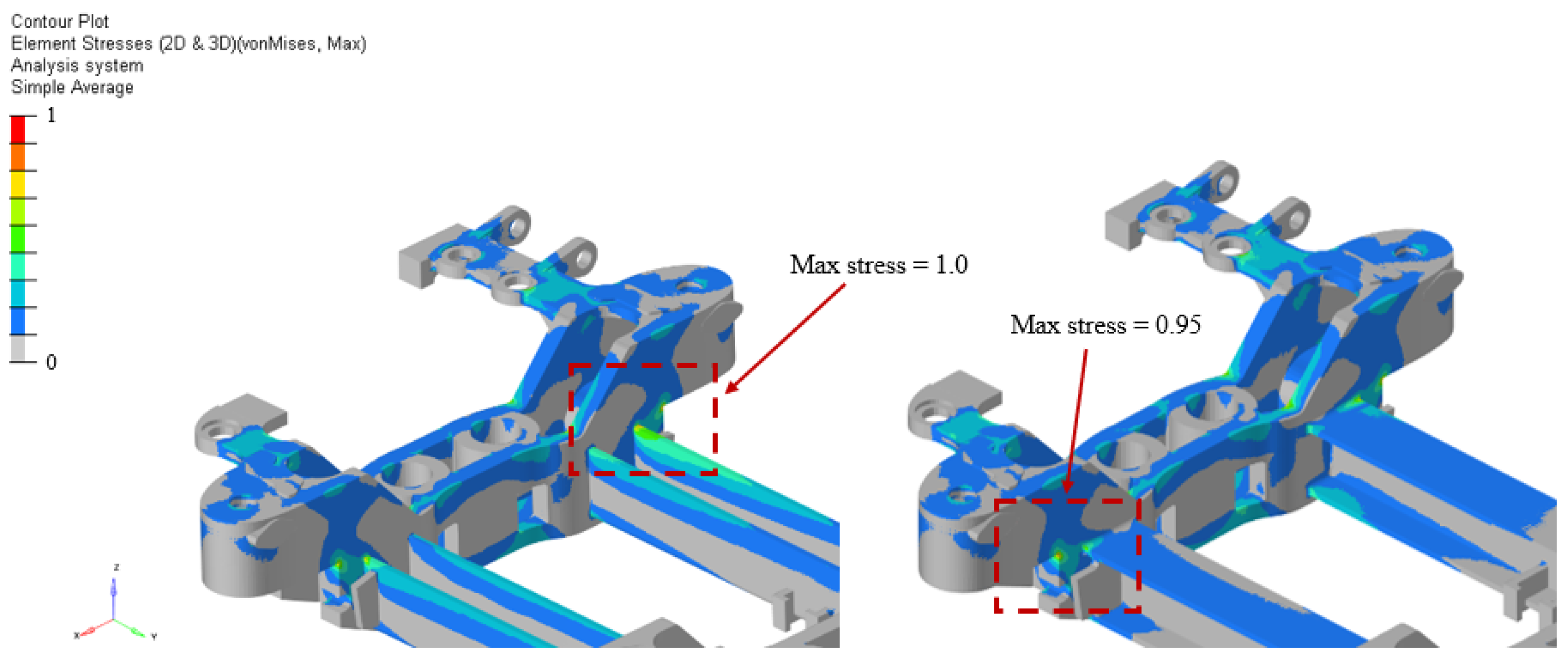

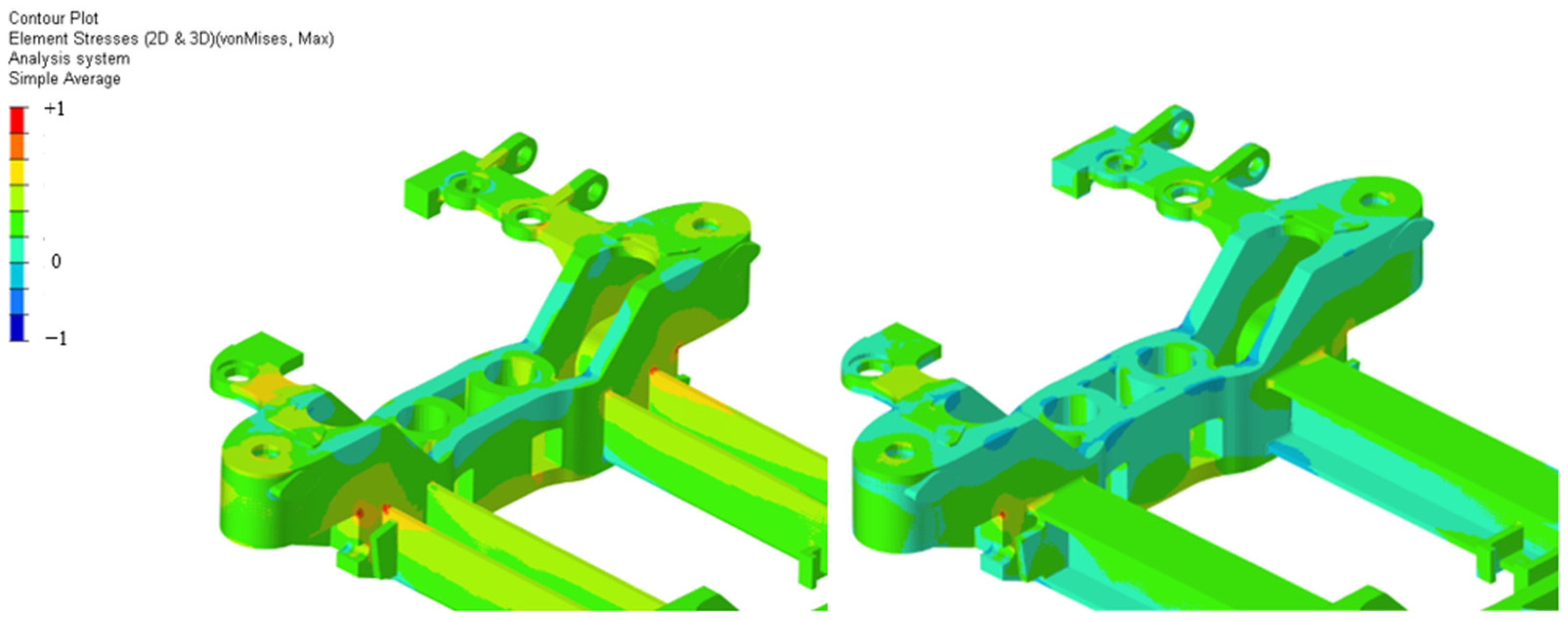

- An intermediate performance assessment of the newly generated bogie-frame geometry was executed according to the reference European standard, allowing the early identification of potential critical issues;

- (5)

- A second optimization cycle was then performed, this time targeting the redesign of the transversal beams, with the dual aim of improving both their mechanical performance and their geometric characteristics from a design-for-manufacturing perspective;

- (6)

- Finally, a complete evaluation of the performance of the optimized geometry was conducted to validate the effectiveness of the proposed design.

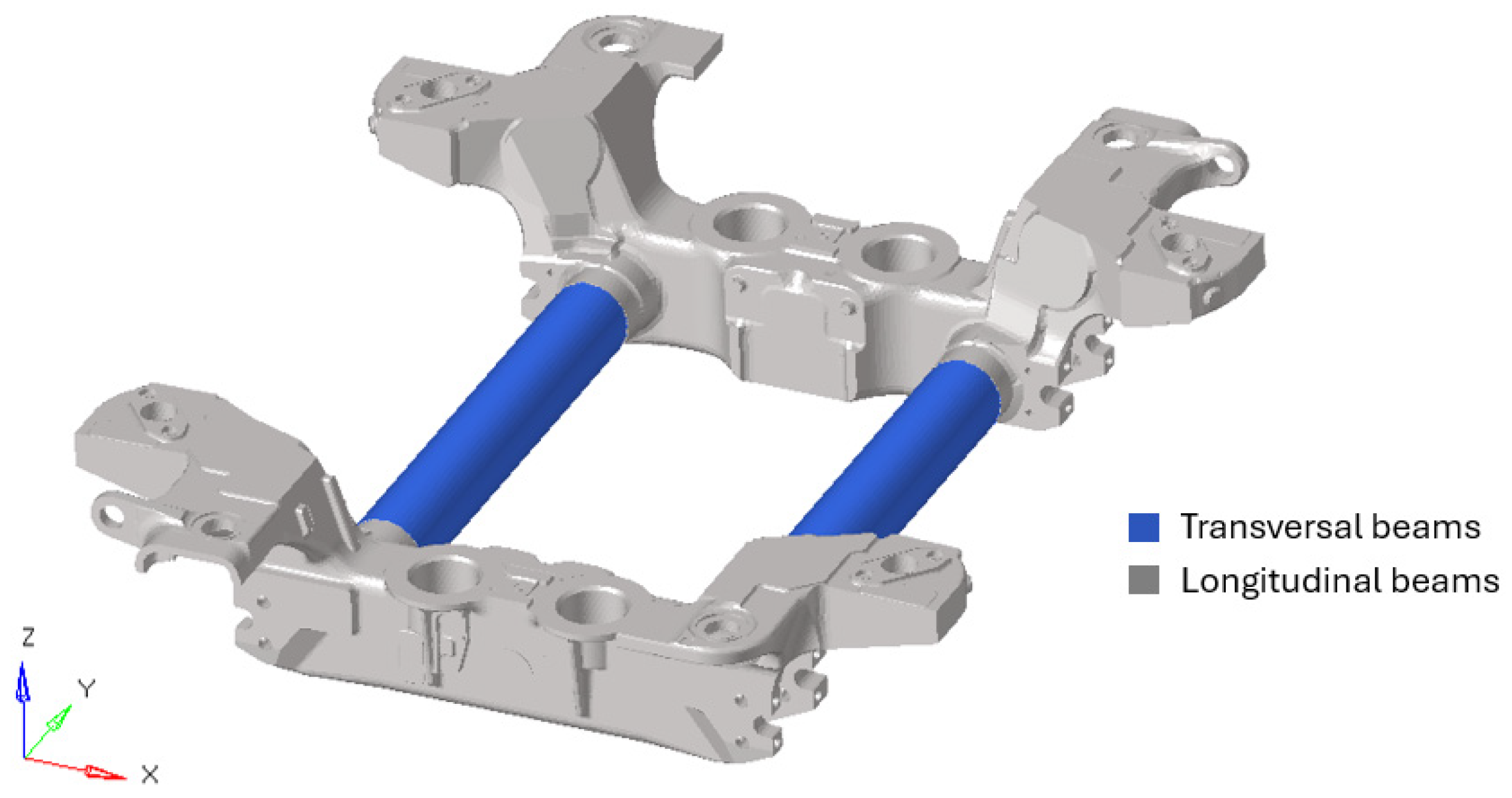

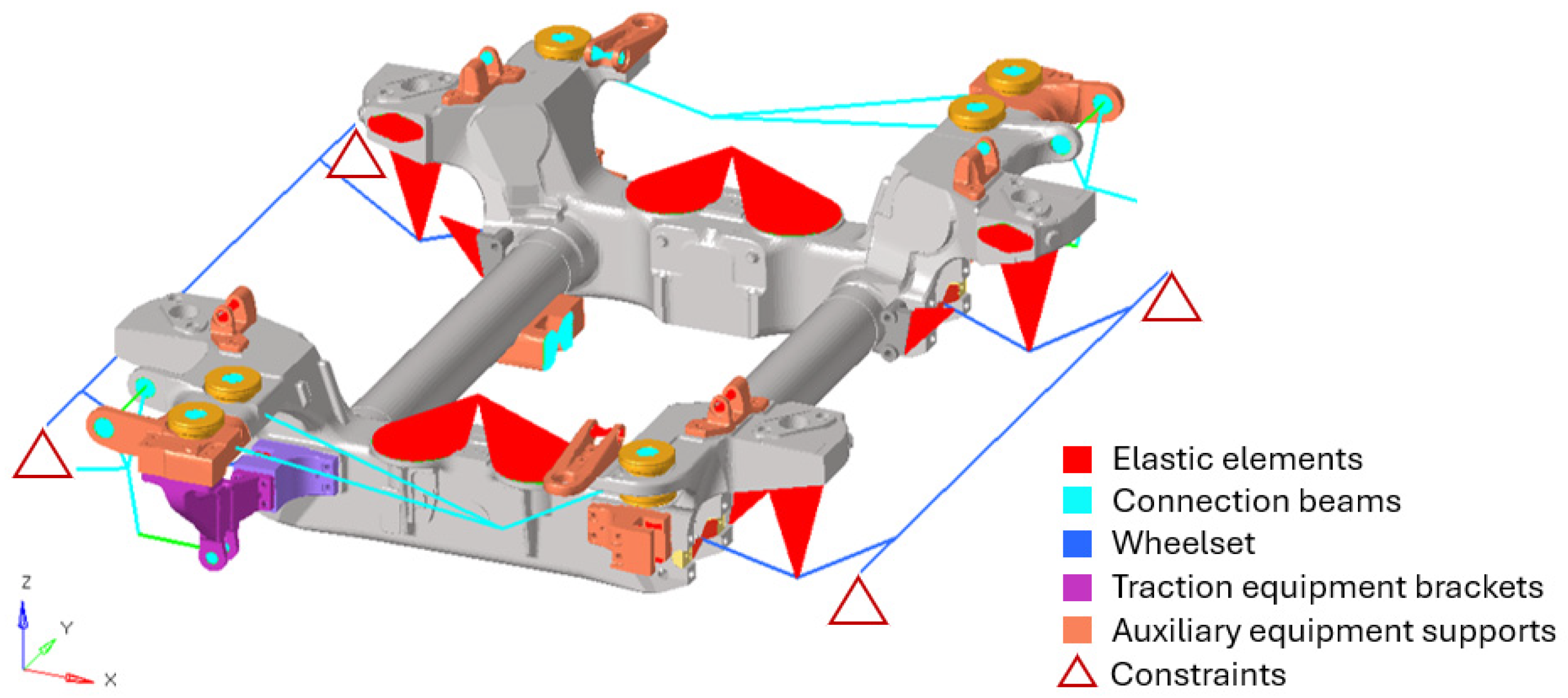

2.2. The Railway Motor Bogie Frame

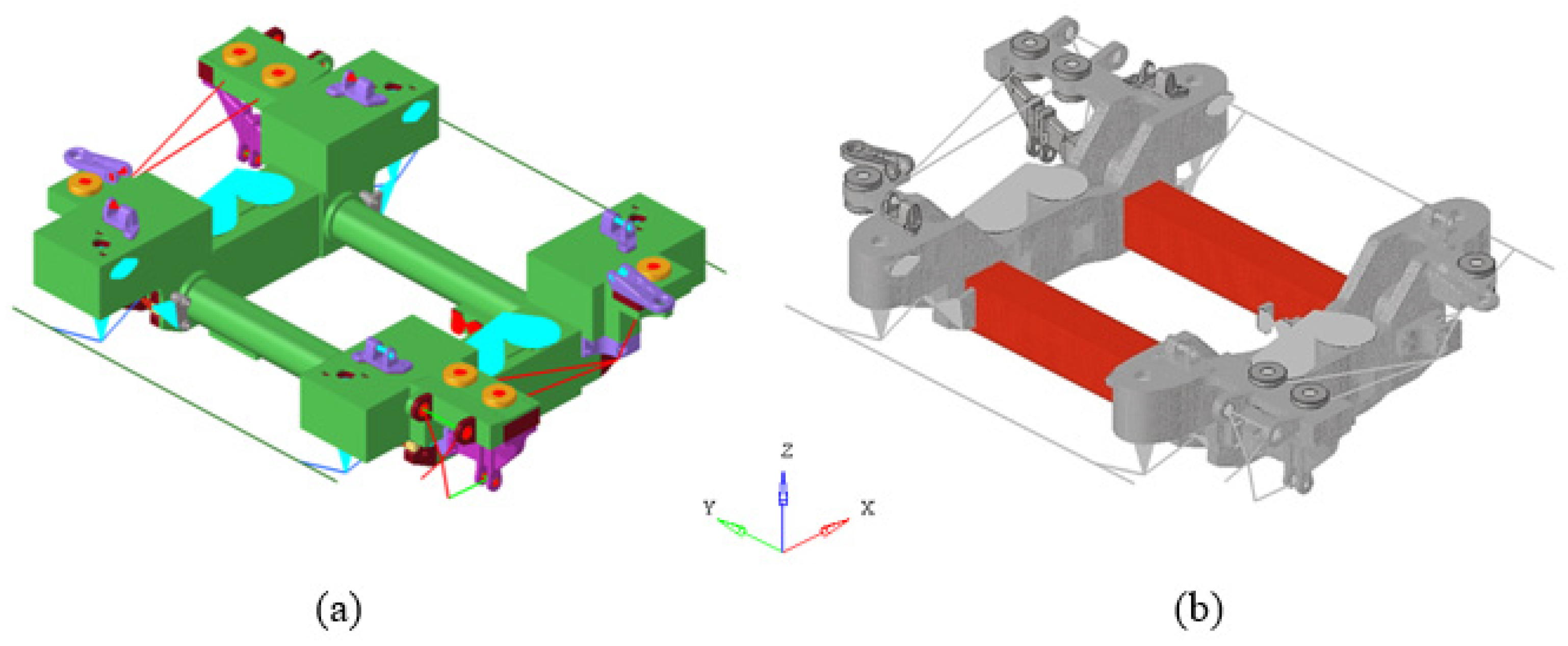

2.3. Topological Optimization Model and Settings

3. Results and Discussion

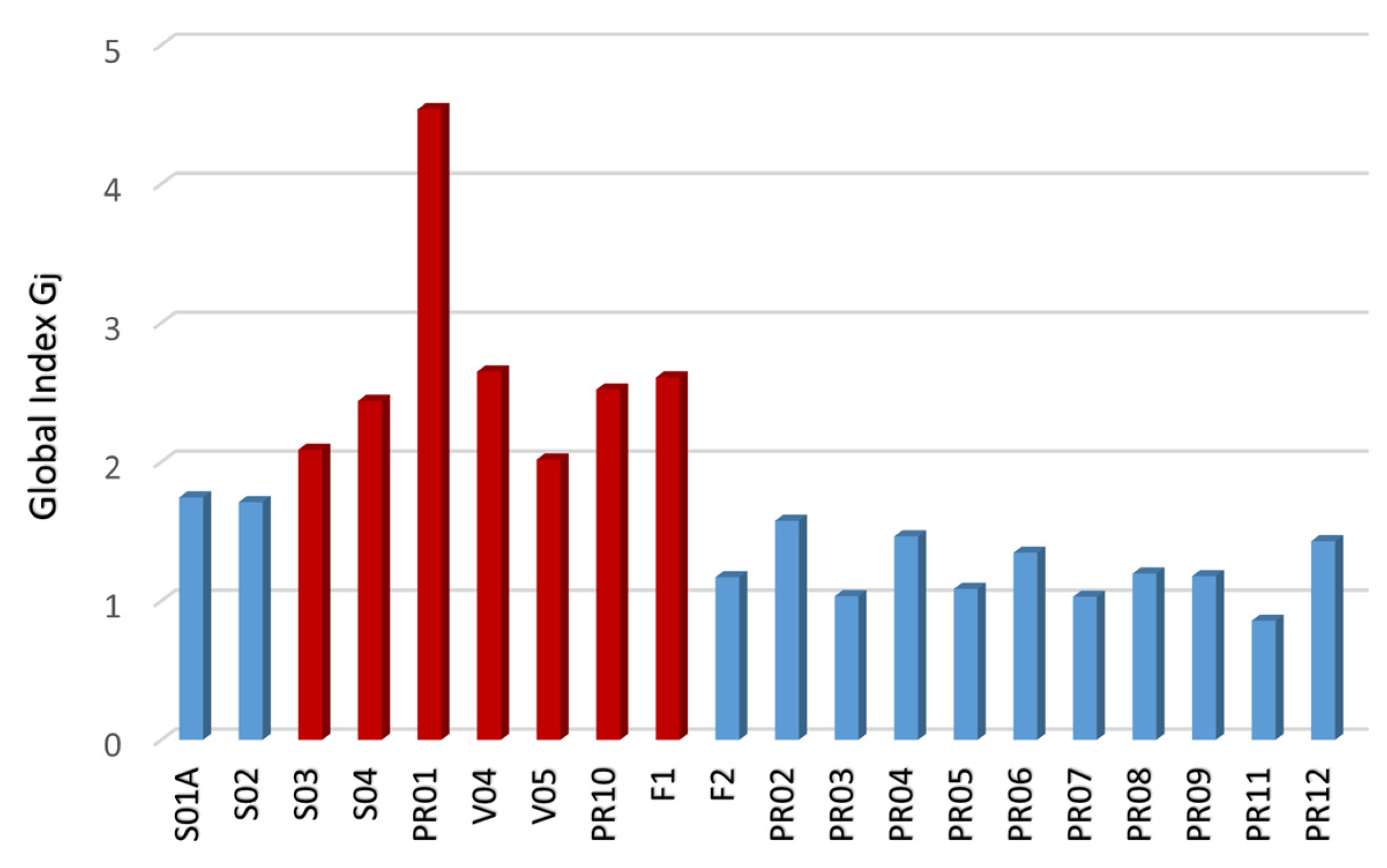

3.1. Load Scenario and Sensitivity Analysis

3.2. Topological Optimization Result and Innovative Bogie Frame Design

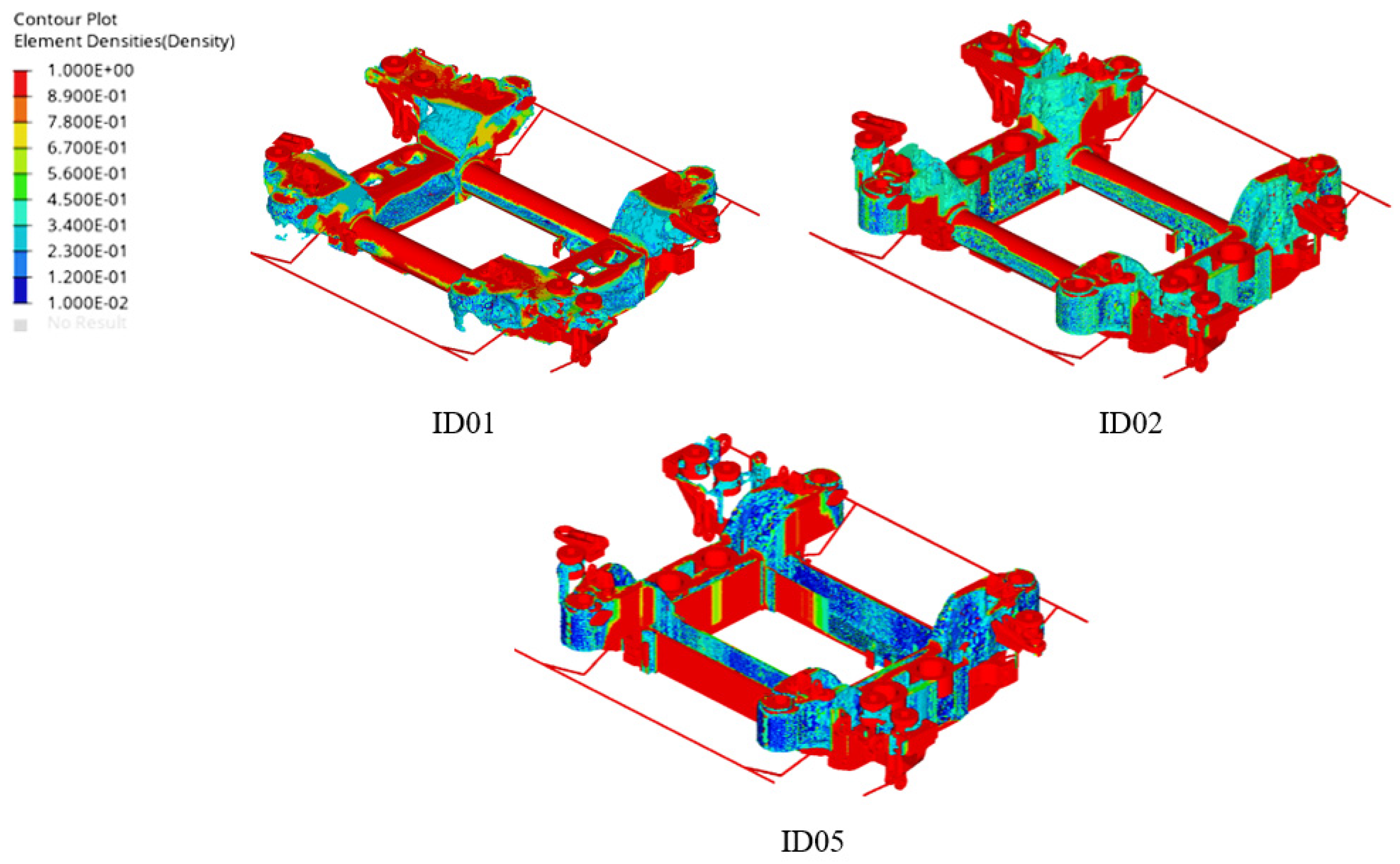

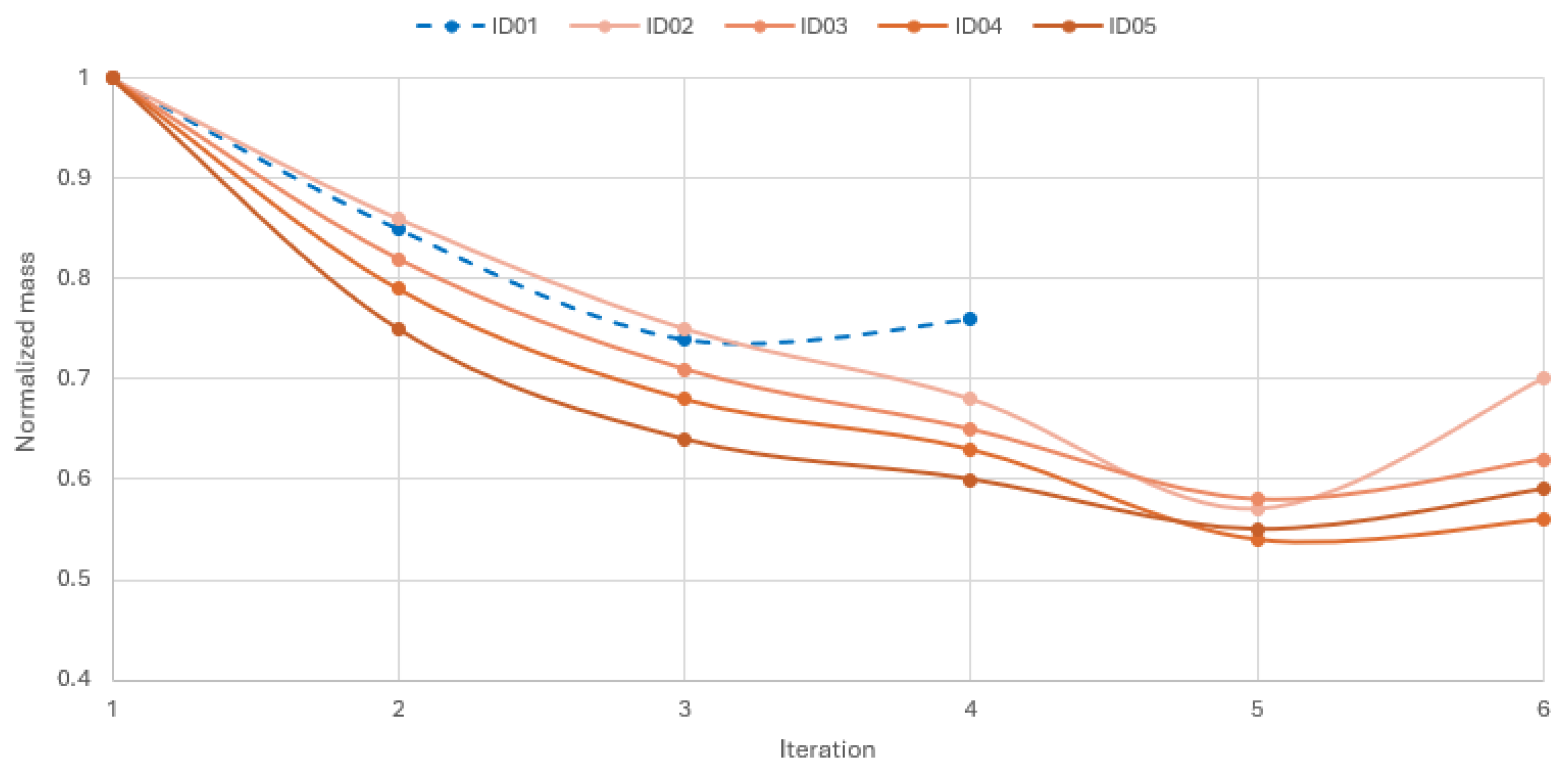

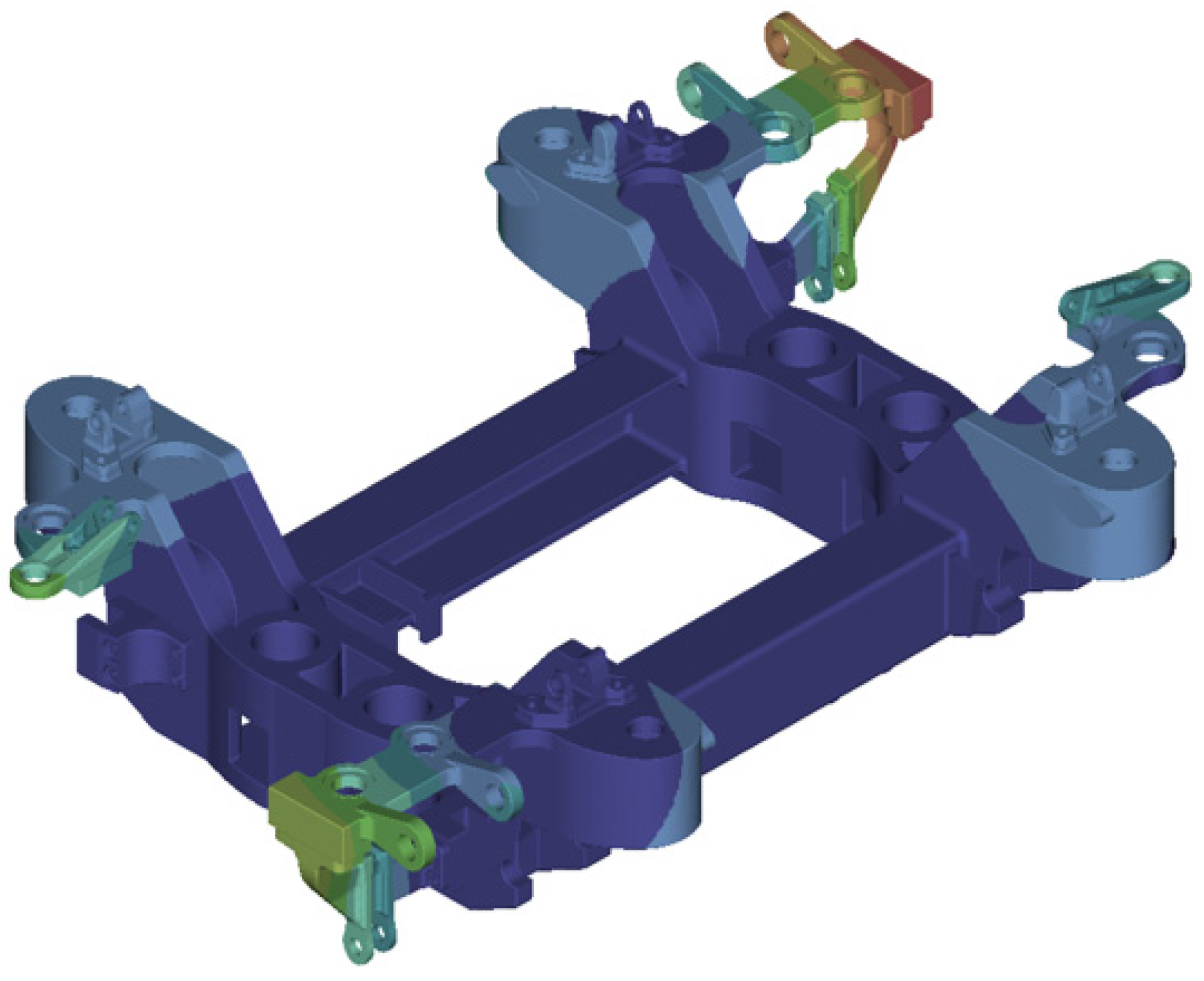

3.2.1. Global Optimization Results

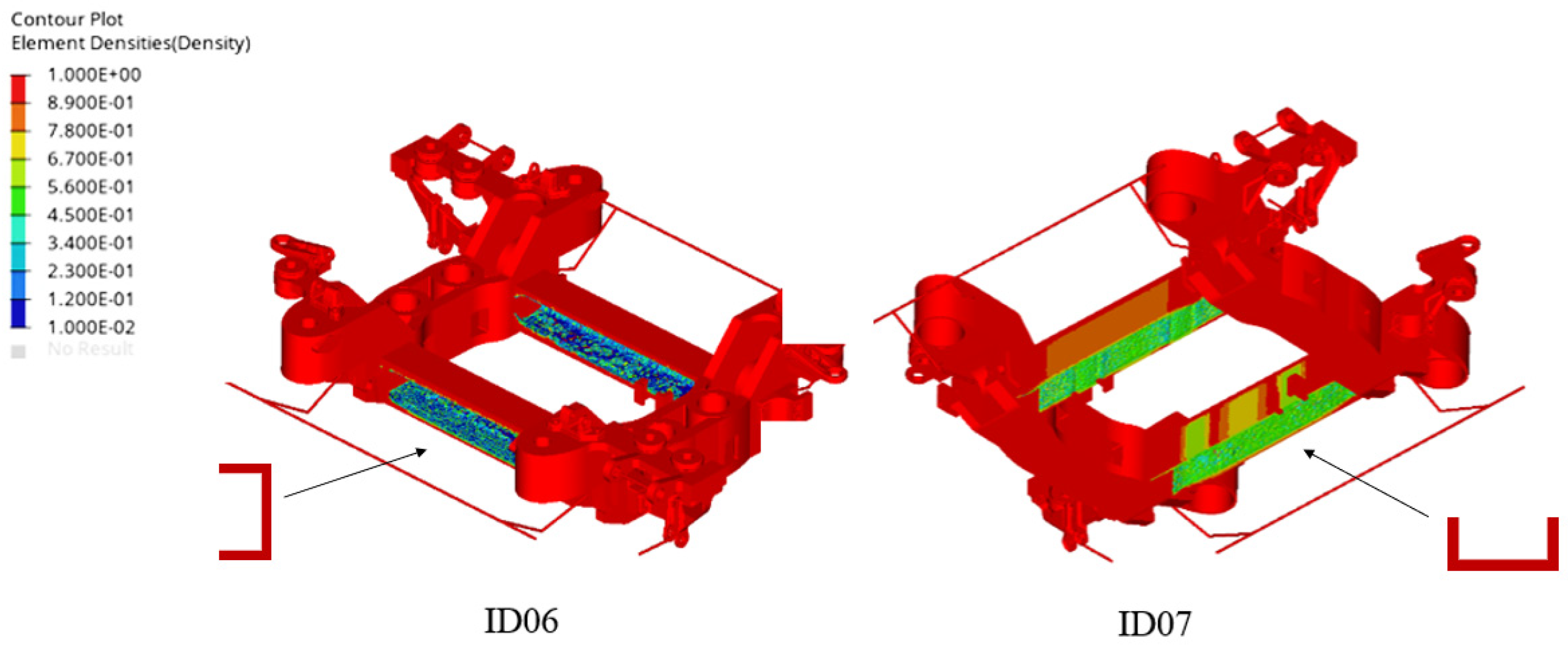

3.2.2. Local Optimization Results

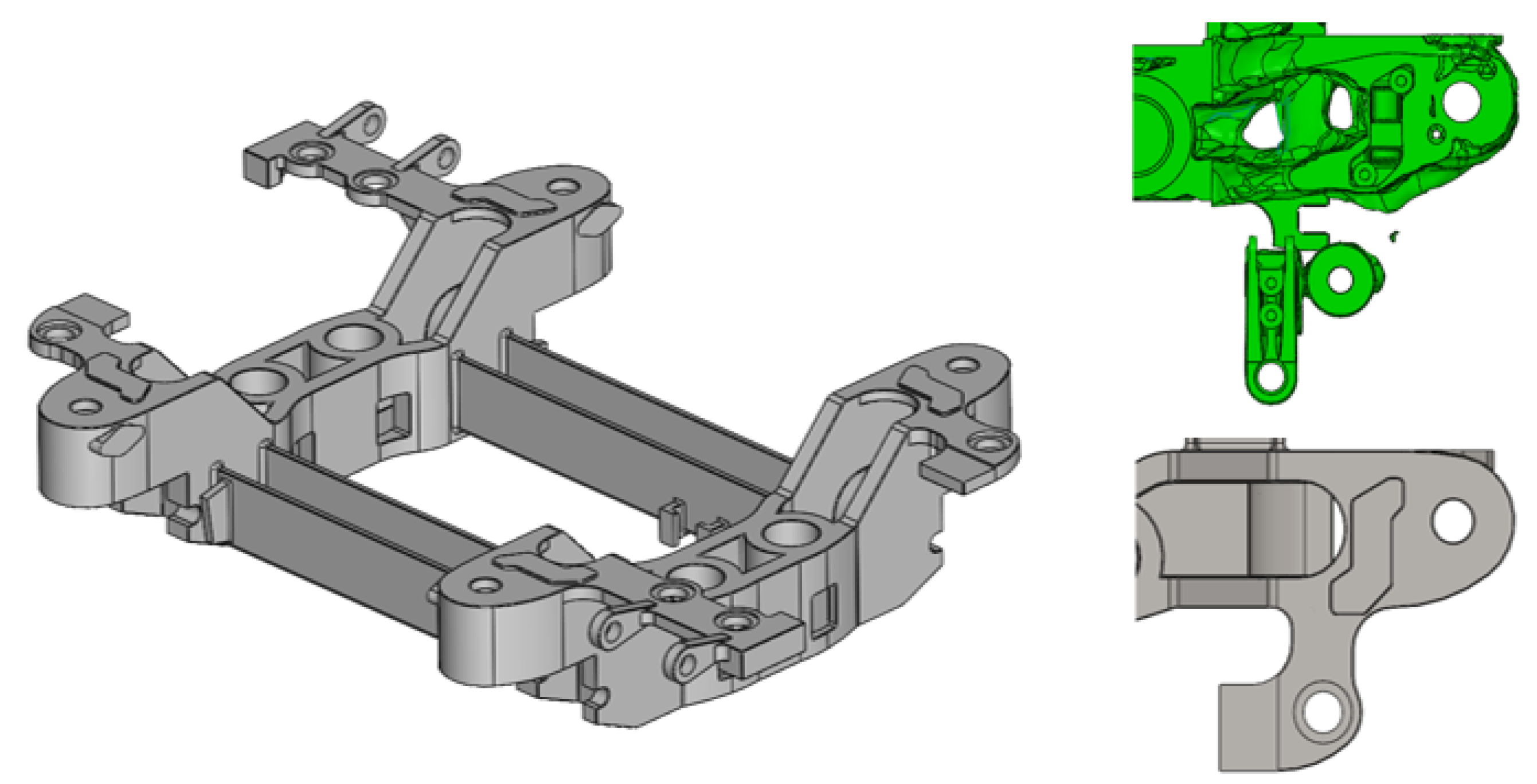

3.2.3. Railway Motor Bogie Frame: Innovative Design

3.3. Structural Performance Assessment

4. Conclusions and Future Developments

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kong, Y.; Abdullah, S.; Omar, M.; Haris, S. Topological and Topographical Optimization of Automotive Spring Lower Seat. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2016, 13, 1388–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovics, D.; Barari, A. Customization of Automotive Structural Components using Additive Manufacturing and Topology Optimization. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; An, D.; Ma, L.; He, Y. A survey of multi-scale optimization methods in fiber-reinforced polymer composites design for automobile applications. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2024, 09544070251327706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billur, S.; Raju, G.U. Mass Optimization of Automotive Radial Arm Using FEA for Modal and Static structural Analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1116, 012113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viqaruddin, M.; Reddy, D.R. Structural optimization of control arm for weight reduction and improved performance. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 9230–9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsimbi, M.; Nziu, P.K.; Masu, L.M.; Maringa, M. Topology optimization of automotive body structures: A review. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 4282–4296. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, L.; Guo, Q.; Yang, S.; Liao, X.; Qi, C. A size optimization procedure for irregularly spaced spot weld design of automotive structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2021, 166, 108015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Yan, L.; Qi, C. An adaptive multi-step varying-domain topology optimization method for spot weld design of automotive structures. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2018, 59, 291–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Qin, H.; Zhong, H.; Lv, C. An efficient structural optimization approach for the modular automotive body conceptual design. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2018, 58, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, J.; Lee, J.; Jang, W.; Han, D.; Kim, N.; Lee, H. Manufacturability-constrained optimization for enhancing quality and suitability of injection-molded short fiber-reinforced plastic/metal hybrid automotive structures. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2023, 66, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, W. A review of topology optimization for additive manufacturing: Status and challenges. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 34, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegard, T.; Paulino, G. Bridging topology optimization and additive manufacturing. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2016, 53, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Munro, D.; Wang, C.; van Keulen, F.; Wu, J. Space-time topology optimization for additive manufacturing. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2019, 61, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabiston, G.; Kim, I. 3D topology optimization for cost and time minimization in additive manufacturing. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2020, 61, 731–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandini, A.; Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Pinelli, L.; Marconcini, M. Improving Aeromechanical Performance of Compressor Rotor Blisk with Topology Optimization. Energies 2024, 17, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A.; Pucci, E.; Matoni, E. Experimental Validation and Dynamic Analysis of Additive Manufacturing Burner for Gas Turbine Applications. Machines 2025, 13, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietropaoli, M.; Ahlfeld, R.; Montomoli, F.; Ciani, A.; D’eRcole, M. Design for Additive Manufacturing: Internal Channel Optimization. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2016: Turbomachinery Technical Conference and Exposition, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 13–17 June 2016; ASME: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 5B: Heat Transfer, p. V05BT11A013. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, P.K.; Shukla, S. Topology Optimization: Weight Reduction of Indian Railway Freight Bogie Side Frame. Int. J. Mech. Eng. 2021, 6, 4374–4383. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, M. Non-parametric optimization of railway wheel web shape based on fatigue design criteria. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 134, 105463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Development of a Design Procedure Combining Topological Optimization and a Multibody Environment: Application to a Tram Motor Bogie Frame. Vehicles 2024, 6, 1843–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersborg, A.R.; Andreasen, C.S. An explicit parameterization for casting constraints in gradient driven topology optimization. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2011, 44, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Development of a Methodology for Railway Bolster Beam Design Enhancement Using Topological Optimization and Manufacturing Constraints. Eng 2024, 5, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Lightweight Design and Topology Optimization of a Railway Motor Support Under Manufacturing and Adaptive Stress Constraints. Vehicles 2026, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.; Radford, D.W. Design Optimization of a Composite Rail Vehicle Anchor Bracket. Urban Rail Transit 2021, 7, 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiu, R.; Spiryagin, M.; Wu, Q.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y. Fatigue life prediction for locomotive bogie frames using virtual prototype technique. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 2021, 235, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Wu, S.C.; Liu, J.X.; Zhang, W.; Qin, Q.B.; Yao, Y. Fatigue life assessment of bogie frames in high-speed railway vehicles considering gear meshing. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 132, 105353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.K.; Gabbitas, B.L.; Brickle, B.V. Fatigue Life Evaluation of a Railway Vehicle Bogie Using an Integrated Dynamic Simulation. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part F J. Rail Rapid Transit 1994, 208, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Gabbitas, B.; Brickle, B. Dynamic stress analysis of an open-shaped railway bogie frame. Eng. Fail. Anal. 1996, 3, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, C.; Li, W.; Xiao, X.; Jian, H.; Gu, Z.; Berto, F. Lifetime assessment and optimization of a welded a-type frame in a mining truck considering uncertainties of material properties and structural geometry and load. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, G.; Wang, H.; Peng, C.; Liu, X.; Xiao, H.; Liang, X. Experimental fatigue evaluation of bogie frames on metro trains. Machines 2022, 10, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Bai, J.; Wu, S.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, P. Experimental investigations on the effects of fatigue crack in urban metro welded bogie frame. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirsch, K.L.; Thole, K.A. Experimental Investigation of Numerically Optimized Wavy Microchannels Created Through Additive Manufacturing. J. Turbomach. 2018, 140, 021002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.G.; Koo, J.S.; Jung, H.S. A lightweight design approach for an EMU carbody using a material selection method and size optimization. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2016, 30, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, J. Integral consideration of the lightweight design for railway vehicles. In Young Researchers Seminar; Technical University of Denmark: Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. High-Fidelity Finite Element Modelling (FEM) and Dynamic Analysis of a Hybrid Aluminium–Honeycomb Railway Vehicle Carbody. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Design and Optimization of a Hybrid Railcar Structure with Multilayer Composite Panels. Materials 2025, 18, 5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, B.; Luo, Y.; Peng, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, H.; Yang, Z. Multidisciplinary design optimization of lightweight carbody for fatigue assessment. Mater. Des. 2020, 194, 108910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12663-1:2015; Railway Applications—Structural Requirements of Railway Vehicle Bodies—Part 1: Locomotives and Passenger Rolling Stock (and Alternative Method for Freight Wagons). German Institute for Standardisation: Berlin, Germany, 2015.

- UNI EN 15663:2019; Railway Applications—Vehicle Reference Masses. UNI (Ente Nazionale Italiano di Unificazione): Milan, Italy, 2019.

- Kumar, W.; Sharma, U.K.; Shome, M. Mechanical properties of conventional structural steel and fire-resistant steel at elevated temperatures. J. Constr. Steel Res. 2021, 181, 106615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, A. Gradient Based Optimization Methods; MAE Technical Report No. 2057; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bruggi, M.; Duysinx, P. Topology optimization for minimum weight with compliance and stress constraints. Struct. Multidiscip. Optim. 2012, 46, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Yeoh, K.; Cui, Y.; Zhao, A.; Luo, Y.; Zhong, Z. Integrated multiscale topology optimization of frame structures for minimizing compliance. Eng. Struct. 2025, 339, 120561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, P.; Kim, H. Robust Topology Optimization: Minimization of Expected and Variance of Compliance. AIAA J. 2013, 51, 2656–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 13749:2021; Railway Applications—Wheelsets and Bogies—Method of Specifying the Structural Requirements of Bogie Frames. The European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. A New Strategy for Railway Bogie Frame Designing Combining Structural–Topological Optimization and Sensitivity Analysis. Vehicles 2024, 6, 651–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Setting Name | Setting Description | Global Optimization | Local Optimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID01 | ID02 | ID03 | ID04 | ID05 | ID06 | ID07 | ||

| Optimization objective | Weighted compliance minimization | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Optimization constraint | Mass fraction lower than a reference value | <0.4 | <0.4 | <0.4 | <0.4 | <0.4 | <0.3 | <0.3 |

| Stress constraint | Calculated stress lower than a reference value | \ | <300 MPa | <300 MPa | <300 MPa | <240 MPa | <240 MPa | <240 MPa |

| Geometrical pattern | Symmetry respect to a plane | \ | plane xz | plane xz | plane xz | plane xz | plane xz | plane xz |

| Minimum feasible feature dimension | The minimum dimension acceptable for elements | \ | 25 mm | 20 mm | 15 mm | 15 mm | 15 mm | 15 mm |

| Extraction direction | Removing material along reference direction | \ | \ | y axis | y axis | y axis | \ | y axis |

| Load Scenario | Description |

|---|---|

| S03 | Lifting on 2 points positioned diagonally on the frame |

| S04 | Main and operative loads |

| PR01 | Main and operative loads, including main systems mass |

| V04 | Combination of loads focused on the principal supports |

| V05 | Exceptional load under truck twist condition |

| PR10 | Max load on secondary suspension (three wheels constrained) |

| F1 | Combination of main loads, operative loads, internal pressure of the air springs and truck twist |

| F2 | Combination of main loads, operative loads, internal pressure of the air springs and truck twist (opposite sign) |

| Mode Number | Original Design [Hz] | Optimized Design [Hz] | Δ % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 63.66 | 64.63 | +1.0 |

| 2 | 101.85 | 134.64 | +32.0 |

| 3 | 115.28 | 138.05 | +19.8 |

| 4 | 201.57 | 197.63 | −2.0 |

| 5 | 247.50 | 224.87 | −9.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cascino, A.; Meli, E.; Rindi, A. Multi-Stage Topology Optimization for Structural Redesign of Railway Motor Bogie Frames. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020973

Cascino A, Meli E, Rindi A. Multi-Stage Topology Optimization for Structural Redesign of Railway Motor Bogie Frames. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):973. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020973

Chicago/Turabian StyleCascino, Alessio, Enrico Meli, and Andrea Rindi. 2026. "Multi-Stage Topology Optimization for Structural Redesign of Railway Motor Bogie Frames" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020973

APA StyleCascino, A., Meli, E., & Rindi, A. (2026). Multi-Stage Topology Optimization for Structural Redesign of Railway Motor Bogie Frames. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 973. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020973