Exploratory LA-ICP-MS Imaging of Foliar-Applied Gold Nanoparticles and Nutrients in Lentil Leaves

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Lentil Cultivation

2.2. Foliar Application of Gold Nanoparticles by Leaf Submersion

2.3. Morphological and Physicochemical Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles

2.3.1. STEM/SEM Imaging of Gold Nanoparticles

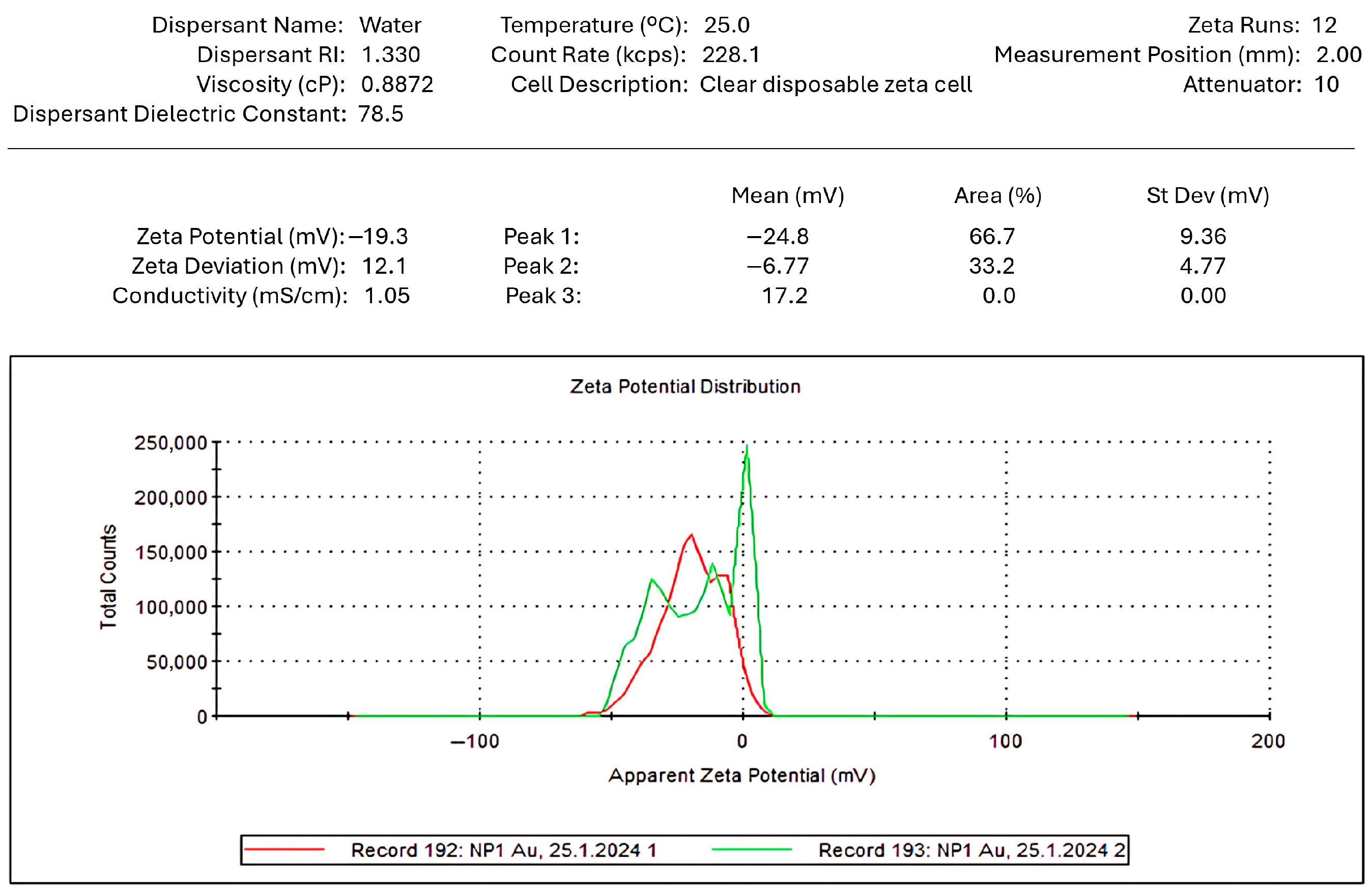

2.3.2. Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles by ζ-Potential

3. Results

3.1. Distribution of Gold Nanoparticles in Lentil Leaves Following Foliar Application by Leaf Submersion

3.2. Comparative LA-ICP-MS Mapping of Macro- and Micronutrients in Lentil Leaves

3.3. Morphological and Physicochemical Characterization of Gold Nanoparticles

3.3.1. STEM Structural and Morphological Analysis of Gold Nanoparticles

3.3.2. Colloidal Stability Assessment of Gold Nanoparticles via ζ-Potential Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Distribution of Gold Nanoparticles in Leaves After Submersion into Au-NP Suspension

4.2. Comparative LA-ICP-MS Mapping of Macro- and Micronutrients in Lentil Leaves

4.3. Morphology and Surface Properties of Gold Nanoparticles

4.3.1. Interpretation of STEM Images

4.3.2. Interpretation of ζ-Potential Results in the Context of Gold Nanoparticle Stability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Arora, S.; Sharma, P.; Kumar, S.; Nayan, R.; Khanna, P.K.; Zaidi, M.G.H. Gold-nanoparticle induced enhancement in growth and seed yield of Brassica juncea. Plant Growth Regul. 2012, 66, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, F.J.; Goh, N.S.; Demirer, G.S.; Matos, J.L.; Landry, M.P. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery towards advancing plant genetic engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 882–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Goh, N.S.; Wang, J.W.; Pinals, R.L.; González-Grandío, E.; Demirer, G.S.; Butrus, S.; Fakra, S.C.; del Rio Flores, A.; Zhai, R.; et al. Nanoparticle cellular internalization is not required for RNA delivery to mature plant leaves. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2022, 17, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, Y.; Pan, L.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X. Nanodelivery of nucleic acids for plant genetic engineering. Discov. Nano 2025, 20, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fan, S.; Chen, Q.; Lu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Xia, L.; Huang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Liu, X. Acute exposure to gold nanoparticles aggravates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury by amplifying apoptosis via ROS-mediated macrophage-hepatocyte crosstalk. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkam, N.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Akkam, Y.; Alrob, O.; Al Trad, B.; Alzoubi, H.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Al-Batayneh, K.M. Investigating the fate and toxicity of green synthesized gold nanoparticles in albino mice. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2023, 49, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chueh, P.J.; Liang, R.Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Zeng, Z.M.; Chuang, S.M. Differential cytotoxic effects of gold nanoparticles in different mammalian cell lines. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 264, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandhini, J.T.; Ezhilarasan, D.; Rajeshkumar, S. An ecofriendly synthesized gold nanoparticles induces cytotoxicity via apoptosis in HepG2 cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2021, 36, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellan, A.; Yun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Spielman-Sun, E.; Unrine, J.M.; Thieme, J.; Li, J.; Lombi, E.; Bland, G.; Lowry, G.V. Nanoparticle size and coating chemistry control foliar uptake pathways, translocation, and leaf-to-rhizosphere transport in wheat. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 5291–5305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malejko, J.; Godlewska-Żyłkiewicz, B.; Vaněk, T.; Landa, P.; Nath, J.; Dror, I.; Berkowitz, B. Uptake, translocation, weathering and speciation of gold nanoparticles in potato, radish, carrot and lettuce crops. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 418, 126219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshkova, A.; Zinicovscaia, I.; Cepoi, L.; Rudi, L.; Chiriac, T.; Yushin, N.; Anh, T.T.; Manh Dung, H.; Corcimaru, S. Effects of gold nanoparticles on Mentha spicata L., soil microbiota, and human health risks: Impact of exposure routes. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botteon, C.E.A.; Pereira, A.D.E.S.; de Castro, L.P.; Justino, I.A.; Fraceto, L.F.; Bastos, J.K.; Marcato, P.D. Toxicity assessment of biogenic gold nanoparticles on crop seeds and zebrafish embryos: Implications for agricultural and aquatic ecosystems. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 1032–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.; Seo, E.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.J. Adsorption of nanoparticles suspended in a drop on a leaf surface of Perilla frutescens and their infiltration through stomatal pathway. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshkova, A.; Zinicovscaia, I.; Rudi, L.; Chiriac, T.; Yushin, N.; Cepoi, L. Effects of foliar application of copper and gold nanoparticles on Petroselinum crispum (Mill.). Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtmeier, N.S.; Walther, P.; Leopold, K. Uptake, effects, and regeneration of barley plants exposed to gold nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 8549–8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yang, X.; Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Hou, C.; Gao, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Zinc oxide nanoparticles affect biomass accumulation and photosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 6, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, P.; Nauser, T.; Wiggenhauser, M.; Aeschlimann, B.; Frossard, E.; Günther, D. In vitro fossilization for high spatial resolution quantification of elements in plant-tissue using LA-ICP-TOFMS. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 4952–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Zoriy, M.; Chen, Y.; Becker, J.S. Imaging of nutrient elements in the leaves of Elsholtzia splendens by laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS). Talanta 2009, 78, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kötschau, A.; Büchel, G.; Einax, J.W.; Fischer, C.; von Tümpling, W.; Merten, D. Mapping of macro and micro elements in the leaves of sunflower (Helianthus annuus) by Laser Ablation-ICP-MS. Microchem. J. 2013, 110, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebesta, M.; Nemček, L.; Urík, M.; Kolenčík, M.; Bujdoš, M.; Vávra, I.; Dobročka, E.; Matúš, P. Partitioning and stability of ionic, nano- and microsized zinc in natural soil suspensions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 700, 134445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballikaya, P.; Brunner, I.; Cocozza, C.; Grolimund, D.; Kaegi, R.; Murazzi, M.E.; Schaub, M.; Schönbeck, L.C.; Sinnet, B.; Cherubini, P. First evidence of nanoparticle uptake through leaves and roots in beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) and pine (Pinus sylvestris L.). Tree Physiol. 2023, 43, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Sikandar, S.; Tasleem, S.; Abdullah, S.; Khan, A.U.; Arsad, N.U.A.; Bhatti, Z. Evaluation of insecticidal potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized by using river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) leaf extract. Insights J. Health Rehabil. 2025, 3, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, N.; Dhiman, R.C. Green silver nanoparticles against Helicoverpa armigera and its effects on biochemical, morphological and histological aspects. J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2022, 10, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmy, E.T.; Ali, M.A.; Ayyad, M.A.; Mohamedbakr, H.G.; Varma, R.S.; Pan, J.H. Molluscicidal and biochemical effects of green-synthesized F-doped ZnO nanoparticles against land snail Monacha cartusiana under laboratory and field conditions. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 308, 119691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellan, A.; Yun, J.; Morais, B.P.; Clement, E.T.; Rodrigues, S.M.; Lowry, G.V. Critical review: Role of inorganic nanoparticle properties on their foliar uptake and in planta translocation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 13417–13431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiede, K.; Hassellöv, M.; Breitbarth, E.; Chaudhry, Q.; Boxall, A.B.A. Considerations for environmental fate and ecotoxicity testing to support environmental risk assessments for engineered nanoparticles. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Peng, X.; Han, X.; Ren, J.; Sun, L.; Fu, Z. Comparison of the toxicity of silver nanoparticles and silver ions on the growth of terrestrial plant model Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Environ. Sci. 2013, 25, 1947–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Guleria, P.; Kumar, V.; Yadav, S.K. Gold nanoparticle exposure induces growth and yield enhancement in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 461–462, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunjan, B.; Zaidi, M.G.H.; Sandeep, A. Impact of gold nanoparticles on physiological and biochemical characteristics of Brassica juncea. J. Plant Biochem. Physiol. 2014, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskar, S.V.; Laware, S.L. Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on cytology and seed germination in onion. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2014, 3, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi, N.; Behbahani, M.; Dini, G.; Razmjou, A. Enhancing the secondary metabolite and anticancer activity of Echinacea purpurea callus extracts by treatment with biosynthesized ZnO nanoparticles. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2018, 9, 045009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venzhik, Y.; Deryabin, A.; Zhukova, K. Au-based nanoparticles enhance low temperature tolerance in wheat by regulating some physiological parameters and gene expression. Plants 2024, 13, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Zhang, H.; Lal, R. Effects of stabilized nanoparticles of copper, zinc, manganese, and iron oxides in low concentrations on lettuce (Lactuca sativa) seed germination: Nanotoxicants or nanonutrients? Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venzhik, Y.; Deryabin, A.; Popov, V.; Dykman, L.; Moshkov, I. Gold nanoparticles as adaptogens increazing the freezing tolerance of wheat seedlings. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 55235–55249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Watts, D.J. Particle surface characteristics may play an important role in phytotoxicity of alumina nanoparticles. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 158, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Xing, B. Root uptake and phytotoxicity of ZnO nanoparticles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5580–5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, C.M.; Majumdar, S.; Duarte-Gardea, M.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Interaction of nanoparticles with edible plants and their possible implications in the food chain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 3485–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Temsah, Y.S.; Joner, E.J. Impact of Fe and Ag nanoparticles on seed germination and differences in bioavailability during exposure in aqueous suspension and soil. Environ. Toxicol. 2012, 27, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Chen, D.; Hu, J.; Zheng, X.; Lin, Z.J.; Zhu, H. The application of coffee-ring effect in analytical chemistry. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2022, 157, 116752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargartalebi, H.; Hejazi, S.H.; Sanati-Nezhad, A. Self-assembly of highly ordered micro- and nanoparticle deposits. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, S.; Fariduddin, M.; Vaidya, S.S.; Thampi, S.P.; Basavaraj, M.G. Tuning evaporation driven deposition in sessile drops via electrostatic hetero-aggregation. Soft Matter 2025, 21, 5242–5254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Zhou, G.; Shimizu, H. Plant responses to drought and rewatering. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010, 5, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, G.; Yasutake, D.; Minami, K.; Kimura, K.; Marui, A.; Wu, Y.; Feng, J.; Wang, W.; Mori, M.; Kitano, M. Evaluation of the physiological significance of leaf wetting by dew as a supplemental water resource in semi-arid crop production. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 255, 106964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Shukla, D.; Kiiskila, J.; Jain, A.; Datta, R.; Sharma, N.; Sahi, S.V. Comparative transcriptome and proteome analysis to reveal the biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles in Arabidopsis. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, B.; Malitsky, S.; Rogachev, I.; Aharoni, A.; Kaftan, F.; Svatoš, A.; Franceschi, P. Sample preparation for mass spectrometry imaging of plant tissues: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hare, D.J.; Billings, J.L.; Bray, L.; Volitakis, I.; Vais, A.; Ryan, T.M.; Cherny, R.A.; Bush, A.I.; Masters, C.L.; Adlard, P.A.; et al. The effect of paraformaldehyde fixation and sucrose cryoprotection on metal concentration in murine neurological tissue. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2014, 29, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonta, M.; Török, S.; Hegedűs, B.; Döme, B.; Limbeck, A. A comparison of sample preparation strategies for biological tissues and subsequent trace element analysis using LA-ICP-MS. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 1805–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrena, R.; Casals, E.; Colón, J.; Font, X.; Sánchez, A.; Puntes, V. Evaluation of the ecotoxicity of model nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2009, 75, 850–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, E.; Barbero, F.; Busquets-Fité, M.; Franz-Wachtel, M.; Köhler, H.R.; Puntes, V.; Kemmerling, B. Growth-promoting gold nanoparticles decrease stress responses in arabidopsis seedlings. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaf, A.; Wang, X.; Tariq, F.; Jhanzab, H.M.; Bibi, Y.; Sher, A.; Razzaq, A.; Fiaz, S.; Tanveer, S.K.; Qayyum, A. Antioxidant enzyme activities correlated with growth parameters of wheat sprayed with silver and gold nanoparticle suspensions. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judy, J.D.; Unrine, J.M.; Rao, W.; Wirick, S.; Bertsch, P.M. Bioavailability of gold nanomaterials to plants: Importance of particle size and surface coating. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 8467–8474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, X.; Cao, J. Discovery of nano-sized gold particles in natural plant tissues. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2018, 16, 1441–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michen, B.; Geers, C.; Vanhecke, D.; Endes, C.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Balog, S.; Fink, A. Avoiding drying-artifacts in transmission electron microscopy: Characterizing the size and colloidal state of nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 9793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nemček, L.; Šebesta, M.; Afzal, S.; Bahelková, M.; Vaculovič, T.; Kollár, J.; Maťko, M.; Hagarová, I. Exploratory LA-ICP-MS Imaging of Foliar-Applied Gold Nanoparticles and Nutrients in Lentil Leaves. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020974

Nemček L, Šebesta M, Afzal S, Bahelková M, Vaculovič T, Kollár J, Maťko M, Hagarová I. Exploratory LA-ICP-MS Imaging of Foliar-Applied Gold Nanoparticles and Nutrients in Lentil Leaves. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(2):974. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020974

Chicago/Turabian StyleNemček, Lucia, Martin Šebesta, Shadma Afzal, Michaela Bahelková, Tomáš Vaculovič, Jozef Kollár, Matúš Maťko, and Ingrid Hagarová. 2026. "Exploratory LA-ICP-MS Imaging of Foliar-Applied Gold Nanoparticles and Nutrients in Lentil Leaves" Applied Sciences 16, no. 2: 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020974

APA StyleNemček, L., Šebesta, M., Afzal, S., Bahelková, M., Vaculovič, T., Kollár, J., Maťko, M., & Hagarová, I. (2026). Exploratory LA-ICP-MS Imaging of Foliar-Applied Gold Nanoparticles and Nutrients in Lentil Leaves. Applied Sciences, 16(2), 974. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16020974

.png)