1. Introduction

Neurofeedback training (NFT) has emerged as a promising intervention for enhancing athletic performance through self-regulation of brain activity patterns [

1,

2]. Recent meta-analyses demonstrate significant effects of electroencephalographic (EEG) neurofeedback on motor performance, with standardized mean differences (SMD; large effect: d ≥ 0.8, medium effect: d = 0.5–0.8) ranging from 0.42 to 0.85 [

3,

4], indicating moderate to large performance improvements in neurofeedback-trained versus control athletes. However, despite growing evidence supporting neurofeedback’s efficacy in sport contexts, critical gaps remain regarding optimal training periodization, specifically the timing intervals between sessions that maximize neuroplasticity and performance gains [

5,

6].

The theoretical foundation for neurofeedback-induced performance enhancement rests on principles of cortical plasticity and operant conditioning of neural oscillations [

7,

8]. Alpha oscillations in cortical–subcortical communication and attentional control [

7,

8] contribute significantly to cortical plasticity in motor regions, and their role has been demonstrated across both general populations and sport-specific contexts [

9,

10,

11]. In general populations, elevated alpha power has been consistently associated with enhanced cognitive performance and optimal arousal states conducive to motor learning [

9,

10,

11]. Alpha neurofeedback learning is characterized by increased incidence of alpha episodes rather than amplitude changes, suggesting volitional control over oscillation onset, a mechanism with direct implications for motor preparation and execution. These neuroplastic adaptations likely occur through mechanisms involving long-term potentiation (LTP) and homeostatic scaling, where repeated alpha enhancement strengthens synaptic connections and optimizes cortical function [

12,

13].

The temporal spacing of training sessions emerges as a critical factor, as spaced learning protocols consistently outperform massed training in promoting long-term memory consolidation and skill retention [

14,

15]. Recent neuroimaging evidence demonstrates that spaced learning produces distinct neural consolidation patterns compared to massed learning, with increased neural integration in cortical rather than hippocampal networks [

15]. These cortical consolidation mechanisms may explain the superior retention effects observed in extended inter-session intervals.

Critically, however, the temporal spacing of training sessions emerges as a fundamental yet systematically unexplored factor in neurofeedback protocol design. Spaced learning protocols, characterized by extended intervals between successive training repetitions, consistently outperform massed training in promoting long-term memory consolidation and skill retention across diverse learning domains [

14,

15,

16]. Yet whether this well-established principle of distributed practice extends to neurofeedback training in athletic populations remains unknown. Furthermore, individual variability in neurofeedback responsiveness remains largely unexplored in athletic populations, with no established phenotypic classifications for predicting treatment outcomes. This personalization gap, combined with the unknown periodization principles, limits the development of targeted interventions that account for differential neuroplastic capacities among elite athletes.

Combat sports present unique neurophysiological demands that may particularly benefit from neurofeedback interventions targeting cortical control and decision-making under pressure [

17,

18]. Elite martial artists demonstrate distinct neural efficiency patterns, including elevated resting alpha power and reduced event-related desynchronization during cognitive-motor tasks, suggesting superior cortical resource allocation [

19,

20]. Judo, characterized by rapid decision-making, spatial-temporal precision, and explosive power generation, exemplifies sports where optimal cortical states directly influence competitive outcomes [

21]. Previous neurofeedback research in judo athletes has shown promising results, with EEG biofeedback training producing significant improvements in visual reaction time and attention compared to control conditions [

22]. However, these studies employed fixed training schedules without systematic investigation of periodization effects. The intermittent, high-intensity nature of judo competition may require specific neuroplasticity protocols that balance adaptation stimuli with adequate recovery periods, a consideration absent from the current neurofeedback literature in combat sports. Despite promising initial findings, fundamental questions remain unanswered regarding the dissociation between neurophysiological adaptations and functional performance outcomes in neurofeedback training. The assumption that EEG changes directly translate to motor performance improvements has not been systematically validated in elite athletic populations, representing a critical theoretical and practical gap.

Current neurofeedback research in sports faces several critical, interconnected limitations that constrain evidence-based protocol development. Fundamentally, no studies have systematically compared different inter-session intervals to determine optimal spacing for neuroplastic consolidation and retention in athletes a knowledge gap that directly prevents understanding of WHEN and HOW neurophysiological adaptations occur. This periodization blindness creates a cascade of downstream problems: without knowing optimal training spacing, researchers cannot identify WHICH athletes respond well versus poorly to specific schedules, as individual response variability remains largely uncharacterized across different training intervals. Consequently, the temporal dynamics of neuroplastic adaptation—specifically when peak neurophysiological responses occur and how they relate to inter-session recovery—remain unexplored, further obscuring the mechanistic basis of training efficacy. Perhaps most problematic, this absence of periodization clarity has prevented systematic investigation of the fundamental relationship between measurable neurophysiological changes and functional performance outcomes. Without understanding optimal inter-session intervals or individual response patterns, researchers cannot establish whether observed strength improvements stem from the measured neural adaptations or occur through independent mechanisms. Together, these interconnected gaps, (1) unknown periodization, (2) uncharacterized individual variability, (3) unexplored temporal dynamics of neural adaptation, and (4) unvalidated neurophysiology-performance relationships, represent a fragmented knowledge base that prevents coherent, mechanism-based protocol design. These compounded limitations collectively impede the translation of neurofeedback from laboratory settings to applied sports environments. Notably, a recent meta-analysis incorporating 21 randomized controlled trials confirmed moderate positive effects of EEG neurofeedback on sport motor tasks (Hedges’s g = 0.78), while identifying several critical moderators including training session frequency, sport type, and personalized feedback approaches. However, systematic comparisons of inter-session periodization strategies across different athletic disciplines remain absent. Consequently, coaches and athletes lack evidence-based guidance on training frequency, individual responsiveness prediction, and whether optimal periodization protocols generalize across diverse sports or require sport-specific customization.

Applied to neurofeedback training scheduling, these theories generate distinct mechanistic predictions about peak adaptation timing: Massed training intervals (E15G-2d: 48 h) permit rapid successive reinforcement of alpha-enhancing behaviors, driving neurons quickly toward saturation thresholds where consolidation processes have insufficient recovery time between sessions. Consequently, peak neurophysiological responses (maximum alpha modulation) should emerge relatively early in the protocol (approximately sessions 5–7), followed by earlier performance plateau as homeostatic constraints limit further cortical modulation. Conversely, spaced training intervals (E15G-3d: 72 h) provide extended consolidation windows during inter-session periods, allowing synaptic weight stabilization through protein synthesis and genetic transcription processes [

12] before subsequent reinforcement. This extended consolidation period delays the onset of homeostatic saturation, permitting sustained cortical modulation across a longer training window, with peak responses expected later in the protocol (approximately sessions 8–12 or later) and more gradual saturation trajectory.

Critically, peak timing represents the session number at which maximum neurophysiological modulation occurs, reflecting the balance between accelerating adaptation drive (produced by successive neurofeedback reinforcement) and accumulating homeostatic constraints (which increase proportionally with training stimulus intensity and repetition frequency). Earlier peaks in massed schedules reflect the faster accumulation of homeostatic load, while later peaks in spaced schedules reflect the extended consolidation windows that delay homeostatic saturation thresholds.

Based on these complementary theoretical frameworks, we formulated four specific predictions. First, we predicted that the E15G-2d protocol (2-day inter-session intervals) will demonstrate peak neurophysiological responses at earlier training sessions (predicted: sessions 5–7), reflecting rapid successive reinforcement and accelerated homeostatic saturation. Following peak achievement, E15G-2d will show earlier stabilization and diminished further gains during sessions 8–15 as homeostatic constraints limit additional neural modulation. Second, we predicted that the E15G-3d protocol (3-day inter-session intervals) will demonstrate peak neurophysiological responses at later training sessions (predicted: sessions 8–12 or later), reflecting extended consolidation windows that delay homeostatic saturation. E15G-3d will show more gradual stabilization and sustained higher neurophysiological values across more training sessions compared to E15G-2d. Third, we predicted that retention assessments will reveal distinct consolidation trajectories: the E15G-2d group will demonstrate maximal retention at 48 h post-training (reflecting massed learning consolidation kinetics), whereas the E15G-3d group will maintain superior retention percentages at 72 h post-training, reflecting enhanced long-term consolidation characteristic of spaced learning protocols [

14,

15]. Fourth, we predicted that the control condition receiving pseudo-neurofeedback will demonstrate negligible changes in neurophysiological and performance measures across all sessions and retention assessments, confirming that observed E15G-2d and E15G-3d effects represent contingent neurofeedback-induced adaptations rather than non-specific training effects.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

Thirty-one elite judo athletes (27 males [87.1%] and four females [12.9%]; age: 22.4 ± 3.1 years; training experience: 8.7 ± 2.3 years; national/international ranking) were recruited from certified judo centers between January and March 2024. The predominantly male composition reflects the current gender representation in competitive elite judo at the national level in Poland during the recruitment period. All held at least a brown belt (1st dan) and competed regularly at national championships.

Inclusion criteria: (1) ≥5 years competitive experience, (2) ≥12 h/week training, (3) no neurological/psychiatric disorders, (4) no psychoactive medication, (5) normal or corrected vision, (6) signed informed consent. Exclusion criteria: (1) history of traumatic brain injury, (2) current use of performance-enhancing substances, (3) neurofeedback in prior 6 months, (4) pregnancy, (5) inability to complete protocol.

Randomization stratified by sex ensured balanced distribution across groups: E15G-2d (n = 12): 10 males and 2 females; E15G-3d (n = 12): 11 males and 1 female; Control (n = 7): 6 males and 1 female. Given the small number of female participants, sex-based subgroup analyses were not performed; however, such analyses remain an important direction for future research in mixed-sex athletic populations.

Anthropometric characteristics (body mass, height, BMI) were assessed using standardized procedures. Baseline neurophysiological status at the C3 training electrode (resting alpha power) showed no significant between-group differences (F(2,29) = 1.24,

p = 0.302), confirming successful stratified randomization for the primary training site. However, secondary baseline measurements at frontal electrodes (F3, F4) used for outcome assessment revealed significant between-group differences in frontal alpha frequencies (detailed in

Section 2.8), which were subsequently controlled as covariates in all primary analyses using linear mixed-effects models with baseline values included as fixed effects.

2.2. Participant Flow and Sample Size

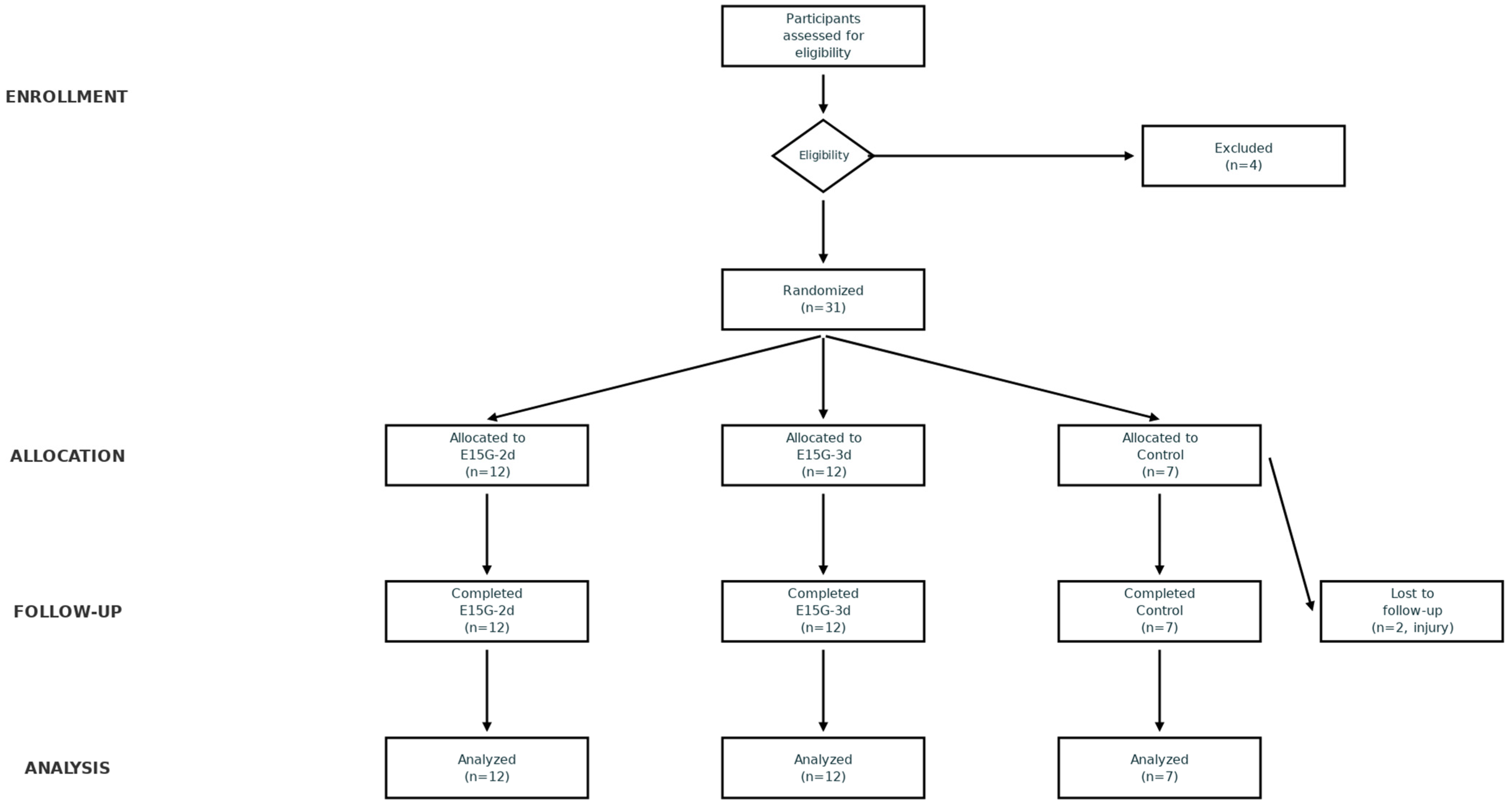

Recruitment, exclusions n = 4, dropouts n = 2 (injury), and final analyzed sample (E15G-2d n = 12, E15G-3d n = 12, active control n = 7) are depicted in the CONSORT flow diagram (

Appendix A,

Figure A1). The control group received pseudo-neurofeedback (randomized, non-contingent feedback signals) with identical session structure, electrode placement, and feedback modalities to active intervention groups, enabling control for non-specific effects (expectancy, device familiarity, attention).

An a priori sample size calculation was conducted using G*Power 3.1.9.7 software to determine the minimum number of participants required to detect a statistically significant interaction effect. The calculation was based on the F-test family (ANOVA: Repeated measures, within-between interaction), which corresponds to the study’s primary design. The effect size was estimated at Cohen’s f = 0.40 (large effect, equivalent to Cohen’s d ≈ 0.8), based on previous meta-analyses indicating large effect sizes for neurofeedback interventions in motor performance. The input parameters were set as follows: significance level (α) = 0.05, statistical power (1 − β) = 0.80, number of groups = 3, and number of measurements = 15 (accounting for correlation among repeated measures). The analysis indicated a minimum required sample size of 27 participants. To account for a potential 10–15% attrition rate typical for longitudinal athletic protocols, the target recruitment was set at n = 31.

2.3. Handling of Measurements

The total measurement architecture comprised: 15 neurofeedback training sessions × 31 participants × 5 loading levels = 2325 total data points.

Loading levels refer to the relative intensity of squat weight loads expressed as a percentage of each participant’s individually determined one-repetition maximum (1RM): 35%, 55%, 70%, 85%, and 100% 1RM.

For each loading level, the measurement outcome was the number of repetitions completed before task failure (defined as inability to maintain proper biomechanical form per standardized criteria in

Section 2.7).

For example, if a participant’s 1RM was 100 kg:

- -

35% = 35 kg (light)

- -

55% = 55 kg (moderate)

- -

70% = 70 kg (heavy)

- -

85% = 85 kg (very heavy)

- -

100% = 100 kg (maximum)

2.4. Ethical Approval

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Bioethical Committee of the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Poland (ethics approval number: KB/11/2021). In line with open science principles and FAIR data standards, the full analysis pipeline and de-identified data supporting this research have been archived and are openly accessible via the Zenodo repository. It can be accessed at: 10.5281/zenodo.17471582. The dataset, includes raw EEG signals (F3, F4 channels and calculated FAI), pre- and post-intervention squat performance metrics across five relative loads (35–100% 1RM), training group stratification, delta indices, and all R scripts used for preprocessing, statistical modeling, and machine learning analysis. All procedures adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.5. Randomization and Blinding

Randomization used computer-generated sequences (randomizeR, R v4.3.1), 1:1:1 ratio, block size 6, stratified by sex and competitive experience.

Experience was stratified into two tiers (5–7 years vs. >7 years) to balance participants across the elite experience spectrum. Experience stratification was successful (F(2,28) = 0.48, p = 0.624).

Sex was included as a stratification control factor; however, strict sex balance could not be achieved given the small sample size (N = 31) and the predominantly male composition of elite competitive judo in Poland (87.1% male). Statistical testing confirmed that observed sex imbalances were random rather than systematic: Chi-square analysis showed no significant differences in sex distribution across groups (χ2(2) = 1.24, p = 0.537), indicating successful stratified randomization at the statistical level.

Distribution by group:

- -

E15G-2d: 10 males (83.3%), 2 females (16.7%)

- -

E15G-3d: 11 males (91.7%), 1 female (8.3%)

- -

Control: 6 males (85.7%), 1 female (14.7%)

Allocation concealment was maintained through sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes prepared by an independent statistician.

Single-blinding was implemented for outcome assessors and data analysts/statisticians. Participants could not be blinded due to intervention nature but were asked not to discuss group allocation.

2.6. Study Design and Timeline

This randomized controlled trial used a parallel-group design: (1) E15G-2d (Experimental 15-session Group with 2-day intervals; n = 12): neurofeedback sessions administered every 48 h across 5 weeks; (2) E15G-3d (Experimental 15-session Group with 3-day intervals; n = 12): neurofeedback sessions administered every 72 h across 8 weeks; and (3) active control (n = 7): pseudo-neurofeedback condition. Timeline: baseline (Week 0), 15-session intervention (Weeks 1–8), post-intervention testing (Week 8), retention at 48 h (E15G-2d) and 72 h (E15G-3d).

Primary endpoints: pre-, post-intervention, and retention. Secondary: session-by-session learning, individual response patterns, adverse events.

Participants were randomized using a computer-generated allocation sequence (random.org, accessed on 15 January 2024) in permuted blocks of six to ensure balanced group sizes. The randomization list was generated by an independent statistician not involved in data collection. Allocation concealment was maintained through sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes opened only after baseline assessments were completed. Research personnel conducting assessments were blinded to group assignment until intervention initiation.

2.7. Intervention Fidelity and Control Condition

Neurofeedback was delivered with a 32-channel EEG system (BrainAmp MR Plus, Brain Products GmbH, Gilching, Germany), electrodes per 10–20 system. Training electrode: C3; reference: FCz; ground: AFz; impedances < 5 kΩ. The C3 electrode was selected based on its anatomical positioning over the left sensorimotor cortex, which exhibits strong alpha oscillations related to motor preparation and execution [

23]. Previous neurofeedback studies in athletic populations have demonstrated that C3-derived alpha modulation correlates with enhanced motor performance and cortical excitability [

24,

25]. The choice of C3 is further supported by its optimal signal-to-noise ratio for alpha detection and minimal artifact contamination during motor tasks [

26].

The protocol targeted individual alpha frequency (IAF; 8–12 Hz, eyes closed, baseline), with target frequency IAF ± 1 Hz, reward threshold at 70th percentile of baseline alpha power [

8,

21]. Inhibit bands: 4–7 Hz (theta), 15–25 Hz (beta). Feedback modalities were strictly contingent on real-time alpha amplitude. Visual feedback consisted of a central green circle (RGB: 0, 255, 0) on a black background, where the radius was linearly modulated by the instantaneous alpha envelope (smoothed with a 250 ms moving average). The circle expanded proportionally when alpha power exceeded the threshold and contracted when below it.

Auditory feedback provided a continuous synthesized sine wave tone ranging from 200 Hz to 800 Hz, where pitch varied logarithmically with alpha amplitude.

Reward thresholds were individualized at baseline and adjusted every 5 training sessions to maintain operant conditioning efficacy (shaping). A stepwise titration protocol was applied: if the participant’s mean time-above-threshold exceeded 80% across the preceding 5-session block, the threshold was increased by 10% (relative to the previous level) to prevent ceiling effects. Conversely, if success rates fell below 60%, the threshold was lowered by 5% to maintain motivation.

Reward thresholds were individualized at baseline and adjusted every 5 training sessions. Sessions containing >20% artifact-contaminated epochs were excluded from analysis and rescheduled to maintain protocol integrity. This online-quality gate ensured that neurofeedback participants received clean neural feedback signals during training delivery.

Two distinct intervention schedules were implemented to examine periodization effects on neuroplastic consolidation while maintaining identical training stimulus volume. Critically, both the E15G-2d and E15G-3d protocols delivered exactly 15 training sessions (15 repetitions per session across both groups), ensuring that total training exposure was constant. The procedural difference concerned exclusively inter-session interval duration: the E15G-2d protocol administered training sessions every 48 h (Monday–Wednesday–Friday schedule across 5 weeks: 48 h × 15 sessions ≈ 34 calendar days), while the E15G-3d protocol administered sessions every 72 h (Monday–Thursday schedule across 8 weeks: 72 h × 15 sessions ≈ 50 calendar days).

This design manipulation permits direct examination of whether neuroplastic consolidation and retention depend on inter-session recovery interval duration (the primary hypothesis derived from spaced learning theory [

14,

15]) rather than total training repetitions or cumulative time-in-protocol. By holding session number constant (15 per group) while systematically varying interval spacing, we isolate the theoretically critical factor (consolidation time between sessions) from confounding variables (total stimulus frequency and calendar duration). This methodological approach directly addresses the central research question: optimal periodization cannot be established by increasing total repetitions alone; instead, the temporal distribution of identical training doses must be examined independently of cumulative stimulus load.

Sessions comprised a 5 min baseline period, 35 min of active training (structured as 7 × 5 min intervals with 1 min interstimulus breaks), and a 5 min post-training period. All participants were positioned in an electrically shielded, sound-attenuated recording chamber under standardized conditions with instructions emphasizing relaxed attention and minimal motor artifacts.

To establish intervention fidelity and control for non-specific effects, the control condition utilized pseudo-neurofeedback with randomized feedback signals that were visually and auditorily indistinguishable from active neurofeedback training (pilot-validated). Control participants completed identical session structure, electrode placement, and feedback modalities as active intervention groups, with the critical difference being that feedback bore no contingent relationship to actual neural activity. Session attendance and compliance were monitored electronically throughout the intervention period, yielding adherence rates of 97% for E15G-2d, 95% for E15G-3d, and 100% for control conditions. No serious adverse events occurred during the study; all reported deviations and minor adverse events are documented in

Appendix B Table A1.

Strength performance was assessed using a standardized Smith machine squat protocol (HUR Ltd., Kokkola, Finland) equipped with an integrated load cell for precise force measurement. All testing sessions were conducted at consistent times (±2 h) with participants maintaining standardized pre-testing nutrition and hydration protocols. Baseline one-repetition maximum (1RM) was determined following a standardized 5 min warm-up, followed by progressive loading increments (50%, 70%, 85%, 95% of estimated 1RM) with 3 min rest intervals between attempts. 1RM was operationally defined as the maximum load lifted through full range of motion with proper biomechanical form; if not achieved within 5 attempts, retesting occurred 72 h later. During retesting, the starting load was set at the highest successfully completed weight from the previous failed session to prevent cumulative fatigue. Subsequent load increments were modulated to 2.5–5% (approx. 2.5–5 kg) steps, smaller than the standard 5–10% increments used in the initial session, to precisely determine the maximum capacity without inducing premature failure. Submaximal strength testing employed a repetition-to-failure protocol at relative intensities of 35%, 55%, 70%, 85%, and 100% of individually determined 1RM, performed in randomized order with 10 min recovery intervals between load conditions. Standardized criteria for valid repetitions included a controlled 2 s eccentric phase and a 1 s isometric hold at the lowest position. Crucially, valid squat depth was rigorously defined as the point where the inguinal crease (hip fold) descended below the superior aspect of the patella (thighs parallel to or below the floor). This depth was visually verified by two independent assessors. The concentric phase was required to be explosive, maintaining full range of motion throughout. Test termination criteria defined as either incomplete repetition completion or breakdown in proper form.

Pre- and post-neurofeedback strength assessments were conducted within 5 and 10 min of intervention completion, respectively, using an abbreviated testing protocol consisting of two randomly selected load conditions per session, counterbalanced across participants to minimize fatigue and learning effects. Prior to baseline testing, all participants completed a familiarization session to acclimate to equipment and standardized testing procedures. Overall protocol reliability was established via intraclass correlation (ICC = 0.92, n = 10). Comprehensive quality control measures included standardized verbal encouragement, visual performance feedback on load and repetition completion, independent load verification, controlled environmental conditions (temperature 20 ± 2 °C, relative humidity 45 ± 10%), and regular equipment calibration according to manufacturer specifications.

Kinematic data were captured using three-dimensional motion capture (Vicon MX-T10, Oxford Metrics, Yarnton, UK) and triaxial force plate recordings (Kistler 9287BA, Kistler Instrumente AG, Winterthur, Switzerland, sampling rate 1000 Hz), synchronized with concurrent EEG acquisition to enable integrated brain-behavior analyses.

EEG signals were recorded continuously during all intervention sessions using a 32-channel actiCHamp system (Brain Products GmbH) with Ag/AgCl electrodes positioned per the 10–20 system, supplemented by electrooculography (EOG) and electromyography (EMG) electrodes for offline artifact detection and removal. Recording parameters included 1000 Hz sampling rate, 24-bit resolution, ±187.5 mV input range, analog bandpass filter (0.1–250 Hz), 50 Hz notch filter, and maintenance of electrode impedances <5 kΩ throughout acquisition.

EEG data were preprocessed using EEGLAB v2022.1 and MATLAB R2023a following standardized protocols: (1) visual inspection for gross artifacts, (2) high-pass filter (1 Hz, Butterworth), (3) low-pass filter (45 Hz, Butterworth), (4) independent component analysis (FastICA algorithm) with mean 2.3 ± 0.7 components removed per session, (5) bad channel interpolation using spherical spline methods, (6) re-referencing to average reference, and (7) epoching into 2 s segments with 50% overlap. Automated epoch rejection criteria included amplitude exceeding ±100 μV or kurtosis > 5 standard deviations (mean 12.4 ± 3.1% epochs rejected per participant), with maximum likelihood estimation applied for handling missing data. Power spectral density was computed via Welch’s method (2 s Hanning windows, 1 s overlap) to determine individual alpha frequency as the dominant peak within the 8–12 Hz band during eyes-closed baseline recording.

Primary outcome: Absolute alpha power was quantified at the C3 electrode (training site) as power spectral density within IAF ± 2 Hz (μV2). Secondary outcome: The Frontal Alpha Index (FAI) was calculated from bilateral frontal electrodes F3 and F4 as FAI = log(F4_alpha) − log(F3_alpha) to characterize asymmetric frontal alpha lateralization, providing a complementary measure of cortical activation asymmetry independent of the training electrode (C3). This secondary measure captures interhemispheric frontal coordination dynamics reflecting broader neuroplasticity effects beyond the localized sensorimotor training site.

Quality metrics throughout offline preprocessing included signal-to-noise ratio assessment, automated artifact rejection rates (quality target <20% of epochs rejected per participant; consistent with the online training-session exclusion criterion of >20% artifact contamination described in

Section 2.7), spectral power distribution analysis, inter-electrode coherence estimation, and test–retest reliability assessment (minimum ICC ≥ 0.75 for inclusion in analyses). This harmonized artifact-rejection protocol at both the training-delivery stage (>20% threshold for session exclusion) and post hoc analysis stage (<20% target for epoch retention) ensured data quality consistency throughout the study.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.3.1), employing the packages lme4 (v1.1-33), emmeans (v1.8.7), effectsize (v0.8.3), pwr (v1.3-0), and mice (v3.16.0). The primary analytical approach followed the intention-to-treat principle. Multiple imputation (mice package, v3.16.0, 20 imputations under MAR assumption) was pre-planned as a contingency protocol for any potential missing data. However, comprehensive data validation confirmed 100% data completeness for primary outcome variables (ΔFAI, ΔF3, ΔF4) across all participants and sessions, eliminating the need to apply imputation procedures. The complete dataset comprised 2325 data points (15 sessions × 31 participants × 5 loading levels) with no missing values. Diagnostics for imputation quality included convergence plots and distributional comparisons between observed and imputed values. We analyzed 2325 data points.

To evaluate group-by-session effects on neurophysiological and performance outcomes, linear mixed-effects models (LMMs) were constructed with fixed effects for group, session, and their interaction, and random intercepts and slopes at the participant level. Model selection was guided by likelihood ratio tests and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Model assumptions, including normality of residuals (Shapiro–Wilk test), homoscedasticity (Breusch–Pagan test), and independence (Durbin–Watson test), were systematically assessed, with robust standard errors or data transformation applied as necessary in the event of violations.

Learning trajectories were further characterized using non-linear mixed-effects models, specifically exponential and logistic growth functions, to capture individual variation in adaptation rates. Retention analyses employed exponential decay models of the form Y(t) = Y0 × e − λt, with group differences in decay parameters tested using likelihood ratio procedures.

Planned contrasts included comparisons between each experimental group and the control, direct comparison of E15G-2d and E15G-3d at peak performance time points, assessment of retention differences, and correlation analyses between neurophysiological and performance outcomes. Multiple testing correction was stratified by analysis priority to balance Type I error control with statistical power:

Primary outcomes (pre-specified, hypothesis-confirming): The Holm–Bonferroni sequential rejection method controlled Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) at α = 0.05 across the five primary pre-registered comparisons (E15G-2d vs. Control, E15G-3d vs. Control, E15G-2d vs. E15G-3d, retention analyses at 48 h and 72 h, and group × session interactions). This conservative approach was chosen because: (1) primary outcomes were pre-specified in the study protocol, (2) Type I errors in confirmatory analyses have high clinical consequences, and (3) Holm’s sequential rejection provides more power than standard Bonferroni while maintaining FWER control.

Secondary and exploratory outcomes (data-driven, post hoc): The False Discovery Rate (Benjamini–Hochberg) adjustment controlled q < 0.05 for session-by-session trajectories, individual response phenotyping, neurophysiological-performance correlations, and sensitivity analyses. FDR was selected for exploratory analyses because: (1) these tests were not pre-specified and serve hypothesis-generating purposes, (2) FDR balances Type I error protection with statistical power for high-dimensional discovery, preventing the overconservativism of FWER in exploratory settings, and (3) FDR is recommended by major statistical societies for secondary analyses where detection of novel patterns is valued. All p-values are explicitly labeled in the Results tables as “primary FWER-adjusted” or “secondary FDR-adjusted” to ensure transparency about correction method.

Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s d (using pooled standard deviations) for between-group differences and partial eta-squared (η2) for ANOVA models, with interpretation based on conventional benchmarks. Clinical significance was evaluated using minimal detectable change estimates derived from baseline variability and measurement error. Post hoc power analyses confirmed that the sample size provided at least 80% power to detect medium to large effects (d ≥ 0.5), and bootstrap resampling (n = 1000) was used to generate confidence intervals for effect size estimates. Baseline differences between groups were assessed using one-way ANOVA for FAI (Frontal Alpha Index) and frontal electrode frequencies (F3, F4) used for outcome measurement. Baseline values were included as fixed effects in all linear mixed-effects models for primary outcomes, ensuring that group-level baseline imbalances were statistically controlled. This covariate-adjusted approach is standard RCT methodology when baseline imbalances occur on secondary measurement variables despite successful randomization on primary variables.

Model diagnostics included examination of residuals, Cook’s distance, and leverage statistics to identify influential cases and potential outliers. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by excluding extreme values and protocol deviations, as detailed in

Appendix B Table A2.

All derived variables (ΔFAI, ΔF3, ΔF4, and strength changes) were calculated using the formula: POST-PRE for each measurement session. Neurophysiological changes were computed from pre- and post-session EEG recordings across all 15 training sessions (225 total data points). Strength performance changes were calculated as post-training minus pre-training values for each loading intensity. Data completeness was verified through automated validation procedures, confirming 100% data availability for primary outcome measures. All calculations underwent rigorous verification procedures including: (1) automated duplicate calculations for all primary derived variables (ΔFAI, ΔF3, ΔF4) performed independently by two analysts to verify computational accuracy; (2) reconciliation of independently derived values with tolerance threshold of zero difference (i.e., exact agreement required); (3) automated range and plausibility checks for all derived values; and (4) integrity checks on formulas using randomly selected test cases (n = 20 randomly selected participant × session combinations) manually verified against automated calculations. This multi-step verification approach eliminated computational errors and ensured accuracy of all statistical analyses.

No missing data were observed for primary outcome variables (ΔFAI, ΔF3, ΔF4) across all participants and sessions, eliminating the need for imputation procedures (as pre-planned in

Section 2.8). All participants completed the full 15-session protocol with 100% data completeness for neurophysiological and strength measures. Secondary analyses confirmed no systematic patterns of data availability related to group assignment or participant characteristics.

All data processing and analysis code, along with de-identified datasets, have been archived and are openly accessible via the Zenodo repository (

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17471582). The study adhered to CONSORT, TIDieR, and current EEG reporting guidelines [

21], with full protocols, scripts, and appendix tables and figures provided as

Appendix A,

Appendix B and

Appendix C.

4. Discussion

The present study systematically investigated neurofeedback training periodization in elite combat sport athletes, revealing complex neurophysiological and strength adaptation patterns that provide important insights into optimal training frequency protocols. Despite stratified randomization, baseline assessments revealed significant between-group differences in cortical alpha lateralization (FAI) and frontal electrode frequencies (F3, F4), necessitating careful statistical control in all primary analyses. These hypotheses were explicitly grounded in established principles of spaced learning [

14,

15], cortical plasticity dynamics [

12], and prior sport-specific neurofeedback research [

21]. The empirical findings presented below now provide direct evidence evaluating these theoretical predictions in an elite athletic population. Peak neurophysiological responses occurred early in both experimental groups (E15G-2d session 6, E15G-3d session 2; see

Table 2 for specific values), indicating rapid initial adaptation followed by stabilization. The aggregate mean ΔFAI across all 15 sessions was modest (see

Table 2), reflecting averaging across heterogeneous individual response trajectories that characterized the study population. The early peak timing suggests that neuroplastic changes occur rapidly in elite athletes, with subsequent sessions serving maintenance rather than progressive enhancement of cortical adaptations.

Differential retention patterns illuminate important periodization effects that extend beyond immediate training responses. The E15G-3d protocol demonstrated significantly superior retention of both neurophysiological and strength performance gains at 72 h post-intervention assessment compared to the E15G-2d group at 48 h (

p < 0.001; see

Table 5 for detailed retention percentages). These findings extend previous single-session neurofeedback studies, suggesting that longer inter-session intervals facilitate deeper consolidation of neuroplastic changes. This consolidation advantage aligns with well-established spaced learning theory, which emphasizes that distributed practice enhances neural adaptation through optimized synaptic stabilization and protein synthesis processes underlying long-term potentiation [

12,

27,

28,

29].

These findings contrast with some prior neurofeedback indications, such as those by Domingos et al. [

5], and clinical protocols reviewed by Rogala et al. [

13], which often suggest that higher training frequency (e.g., 3–4 sessions per week) maximizes reinforcement rates and accelerates initial acquisition. However, this discrepancy likely reflects fundamental differences between clinical restoration and peak performance optimization. While frequent “massed” practice may be superior for rapid symptom reduction in clinical populations, our data suggest that in elite athletes, who already sustain high cognitive and physiological loads from daily physical training, shorter intervals may induce “homeostatic saturation” [

28]. According to the metaplasticity framework, neural networks require adequate recovery time to reset excitability thresholds. Therefore, the 3-day interval appears to mitigate this saturation risk, allowing for superior consolidation despite a potentially slower initial acquisition rate compared to massed protocols.

From a hypothesis-testing perspective, the present findings provide only partial support for our pre-registered hypotheses H1–H4. H3, which predicted superior 72 h retention in the 3-day protocol compared with the 2-day schedule, and H4, which predicted negligible changes in the active control group, were clearly confirmed by the retention analyses and the stability of control trajectories. By contrast, H1 and H2, which specified distinct timing of peak neurophysiological responses in the E15G-2d and E15G-3d protocols, were not fully supported. As anticipated, both experimental groups displayed an early peak in FAI responses followed by a stabilization phase; however, the group-level peaks occurred at session 6 in E15G-2d and session 2 in E15G-3d, and the expected later peak in the spaced E15G-3d protocol did not emerge. These data therefore falsify the precise timing predictions of H1–H2, while supporting their broader premise that FAI responses would show an early peak followed by saturation.

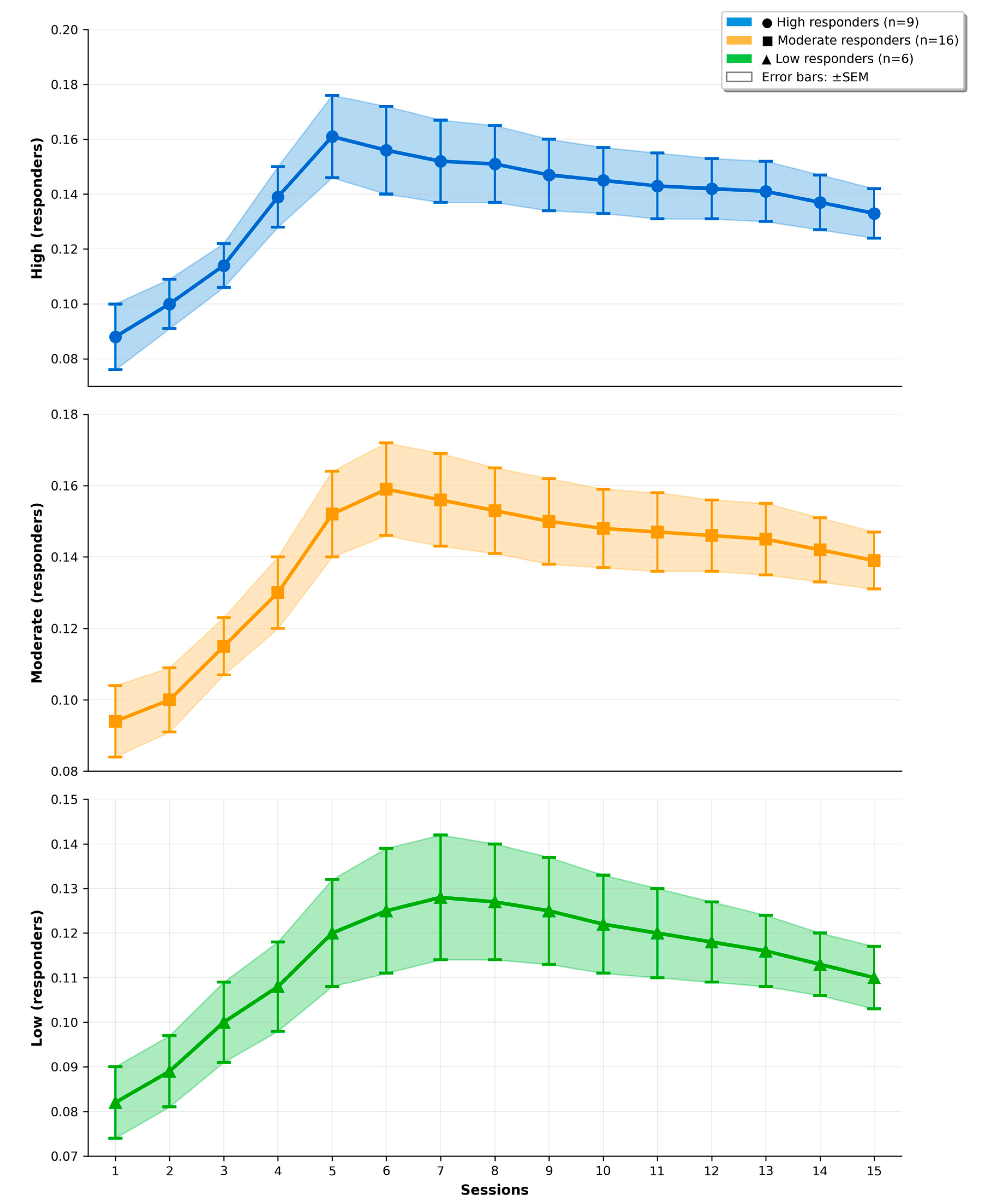

Several factors may explain why the peak FAI responses occurred earlier than predicted and why H1–H2 were not fully verified. First, elite judo athletes are characterized by pre-existing neural efficiency and rapid cortical tuning, including elevated baseline alpha power and optimized sensorimotor control, which can accelerate neurofeedback learning relative to novice or general populations [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. In such highly trained athletes, the window for neuroplastic adaptation may be compressed, leading to faster approach to ceiling levels and consequently earlier peak responses than anticipated. Second, phenotype-based analyses revealed substantial inter-individual heterogeneity, with high and moderate responders reaching maximal FAI between approximately sessions 5–7 and low responders peaking around session 8; this dispersion in individual timelines likely blurred any systematic between-protocol differences in peak timing at the group level. Third, the intensive concurrent physical training and competition demands typical for national-level judo may have constrained the extent to which longer inter-session intervals could further delay or amplify peak FAI responses. Together, these factors suggest that in elite combat athletes, neurofeedback-induced neuroplasticity may occur faster and within a narrower temporal window than originally hypothesized, limiting the discriminating power of H1–H2 regarding peak timing.

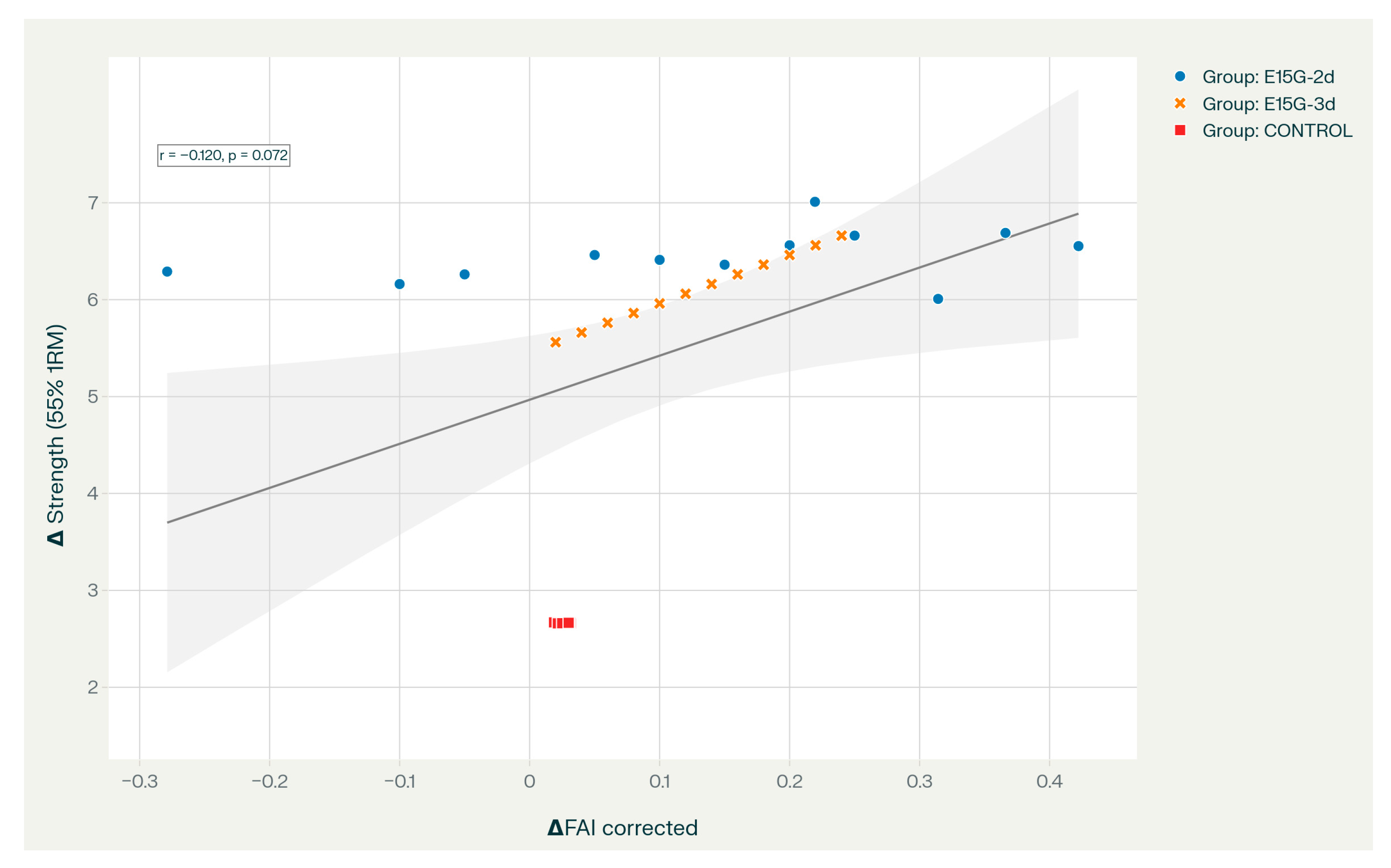

Although the direct correlation between ΔFAI and strength gains was not statistically significant (p > 0.072), this dissociation likely reflects the non-linear nature of neural adaptation in elite athletes rather than a lack of functional connection. We propose two specific mediating mechanisms to explain this outcome. First, the “Cortical Disinhibition Hypothesis”: enhanced alpha power may not directly drive force production but rather facilitates the reduction in antagonist muscle co-activation. In judo, this aligns with the principle of “explosive relaxation” (kime), where the suppression of cortical noise allows for more synchronized motor unit recruitment during the concentric phase. Second, the “Neural Efficiency Hypothesis”: elite athletes typically require less cortical activation to produce a given force output. Therefore, the strength gains observed in the experimental groups may stem from improved processing efficiency (doing more with the same neural “cost”) rather than a linear increase in total cortical drive. Consequently, FAI serves as a “permissive” state marker that enables these downstream neuromuscular adaptations, rather than a direct linear predictor of torque magnitude.

Elite Athlete Expertise and Physiological Considerations

The rapid early peak neurophysiological responses observed in both experimental groups may reflect the established neuroplastic capacity of elite athletes developed through intensive, long-term motor training. Extensive judo training, characterized by thousands of hours of deliberate practice, develops superior cortical efficiency, well-consolidated motor representations in primary and supplementary motor cortices, and optimized sensorimotor integration mechanisms that may facilitate rapid adaptation to novel neurofeedback stimuli [

17,

18,

20]. This expertise-dependent acceleration contrasts with observations in recreationally trained or sedentary populations, where neurofeedback-induced alpha modulation typically emerges more gradually over multiple training sessions [

1,

3]. However, the presence of ceiling effects must also be considered: having already achieved high-level motor optimization through years of competitive practice, elite athletes’ cortex may face inherent constraints on further neuroplastic gains, potentially explaining the plateau pattern observed in later training sessions (sessions 10–15) [

8,

12]. Future research should directly compare elite versus non-elite athlete cohorts while systematically varying neurofeedback difficulty to delineate expertise-dependent neuroplasticity boundaries and mechanisms.

Nutritional factors merit explicit consideration in interpreting the present findings and their translational implications for elite combat sports. Elite judo athletes, competing within strict weight categories, frequently employ weight management strategies, including controlled caloric restriction, macronutrient periodization (e.g., carbohydrate loading, protein timing), and strategic dehydration-rehydration cycles to optimize performance within their respective weight classes [

21,

22]. These dietary practices may substantially influence neuroplasticity mechanisms through multiple pathways. Specifically, caloric restriction and micronutrient availability affect synthesis and bioavailability of critical neurotrophic factors (e.g., brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF], nerve growth factor [NGF]) [

10,

16], modulate neuroendocrine function including growth hormone secretion and cortisol dynamics, and influence micronutrient status (e.g., iron, zinc, magnesium, B vitamins) essential for synaptic transmission, myelin formation, and neuroplastic processes [

11,

26]. Although the present study did not systematically assess nutritional intake, anthropometric measures, or body composition, future investigations incorporating detailed dietary assessment (via standardized food records or biomarkers such as vitamin D levels, iron markers), hormonal profiling, and body composition analysis would clarify whether nutritional optimization or correction of micronutrient deficiencies could enhance neurofeedback training efficacy in weight-classified sports. This mechanistic understanding could inform evidence-based nutritional periodization strategies specifically designed to support neurofeedback training in athletes managing weight constraints.

The observed strength performance gains, while not strongly correlated with FAI changes at the C3 electrode (see

Table 4, all

p > 0.072), likely reflect coordinated adaptations across multiple levels of the neuromuscular system, extending substantially beyond the localized cortical alpha modulation captured by single-electrode EEG. Strength improvements in elite athletes involve integrated adaptations including enhanced motor unit recruitment patterns and firing frequency synchronization [

23,

25], increased motor cortex output via corticospinal tract activation [

6,

9], and peripheral neuromuscular junction remodeling affecting acetylcholine receptor distribution and synaptic transmission efficiency [

2,

4]. At the muscular level, strength adaptations encompass changes in skeletal muscle fiber type composition (shifts toward glycolytic type II fiber recruitment and potential hypertrophic responses), increased myofibrillar protein synthesis and contractile apparatus organization [

14,

15], enhanced oxidative capacity and mitochondrial biogenesis particularly in oxidative type I fibers, and improved mechanical power output through optimized fascicle angle and pennation geometry. The marked dissociation between cortical neurophysiological changes (ΔFAI) and peripheral strength outcomes suggests that neurofeedback-mediated cortical alpha modulation may enhance performance through multiple descending pathways including the corticospinal tract, reticulospinal tract, and vestibulospinal pathways [

7,

13] and spinal motor mechanisms (Renshaw cell inhibition modulation, recurrent inhibition adjustment) without necessarily producing measurable alterations in the highly localized alpha oscillations monitored at the C3 electrode [

29,

30]. This multi-level neural organization suggests that global measures of descending motor drive may be present despite the absence of significant changes in regional alpha power. Future investigations employing motor unit action potential decomposition analysis, high-density surface electromyography, muscle ultrasound assessment of fascicle dynamics, or detailed 3D biomechanical analysis would provide direct evidence regarding muscular and neuromuscular contributions to the observed performance gains [

27,

31], yielding a more mechanistically comprehensive understanding of the multisystem adaptations underlying neurofeedback training effects in elite athletes.

In summary, while H3 and H4 were clearly supported, the present data falsified the specific timing predictions of H1–H2 and instead revealed earlier-than-expected neural peaks and substantial individual variability in elite judo athletes, underscoring the need for phenotype-tailored periodization in future neurofeedback protocols.