PLA-Based Films Reinforced with Cellulose Nanofibres from Salicornia ramosissima By-Product with Proof of Concept in High-Pressure Processing

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cellulose Nanofibres

2.2. PLA-Based Films and Processing Techniques

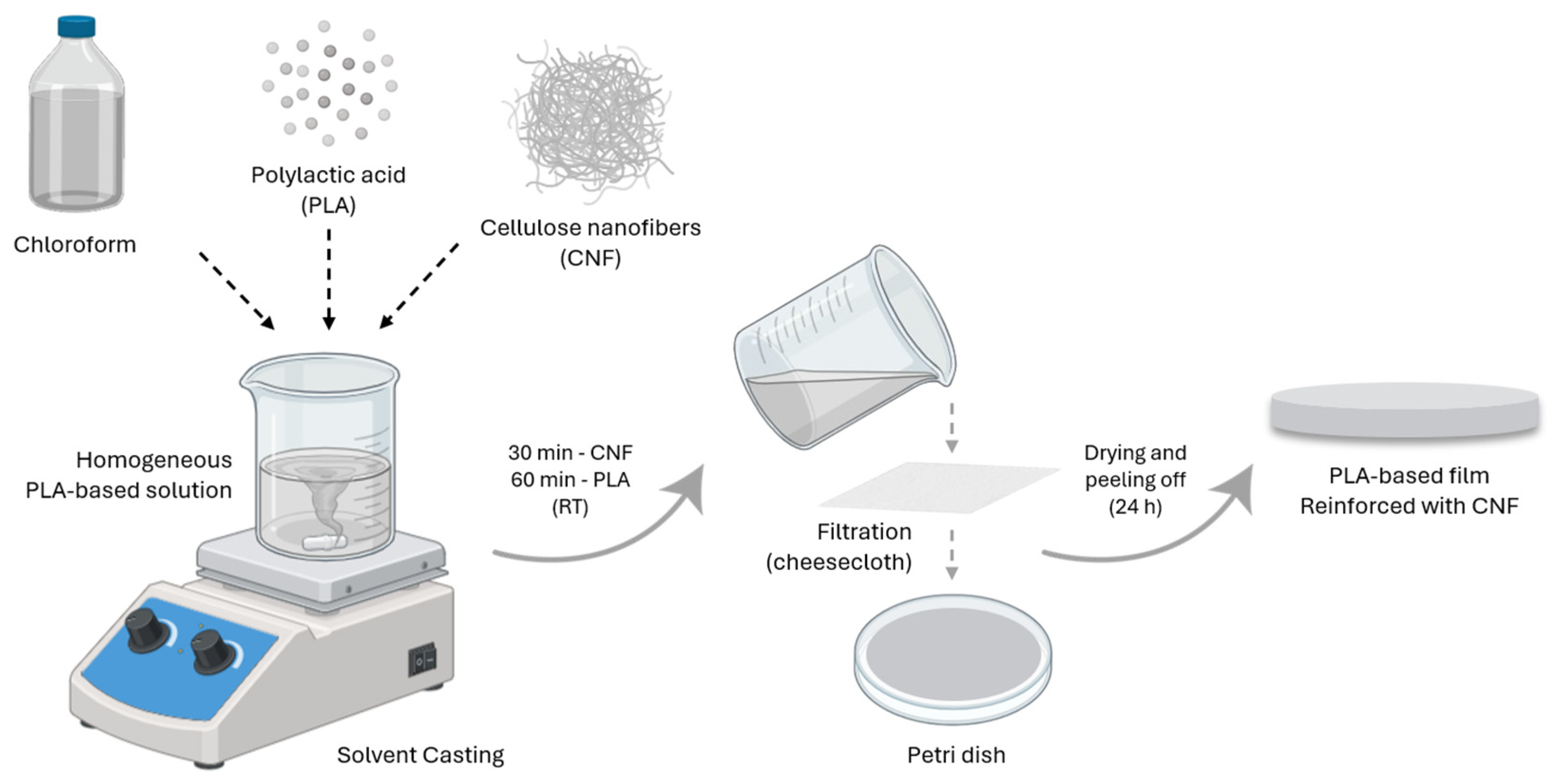

2.2.1. Solvent Casting (SC)

2.2.2. Electrospinning (ES)

2.3. Characterisation of Films

2.3.1. Colour and Opacity

2.3.2. Thickness and Mechanical Properties

2.3.3. Moisture and Solubility in Aqueous Medium

2.3.4. Water Vapour Permeability (WVP)

2.3.5. Water Contact Angle (WCA)

2.3.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.7. Thermogravimetry Analysis (TGA)

2.3.8. Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transformed Infrared (ATR-FTIR)

2.4. Food Packaging

2.5. High-Pressure Processing (HPP)

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

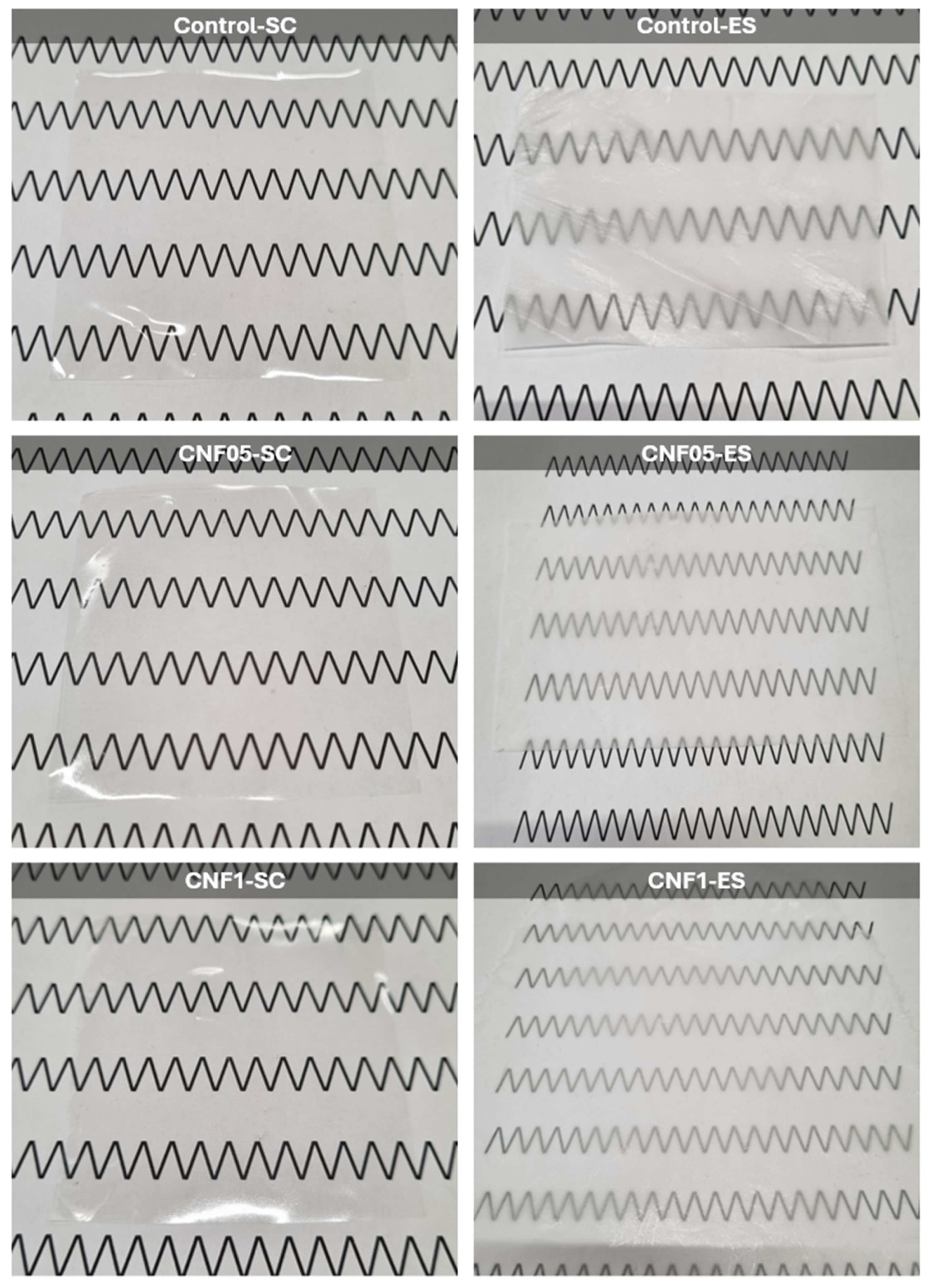

3.1. Optical Properties

3.2. Evaluation of Thickness and Mechanical Properties

3.3. Physical Characterisation

3.4. Evaluation of Water Contact Angle (WCA)

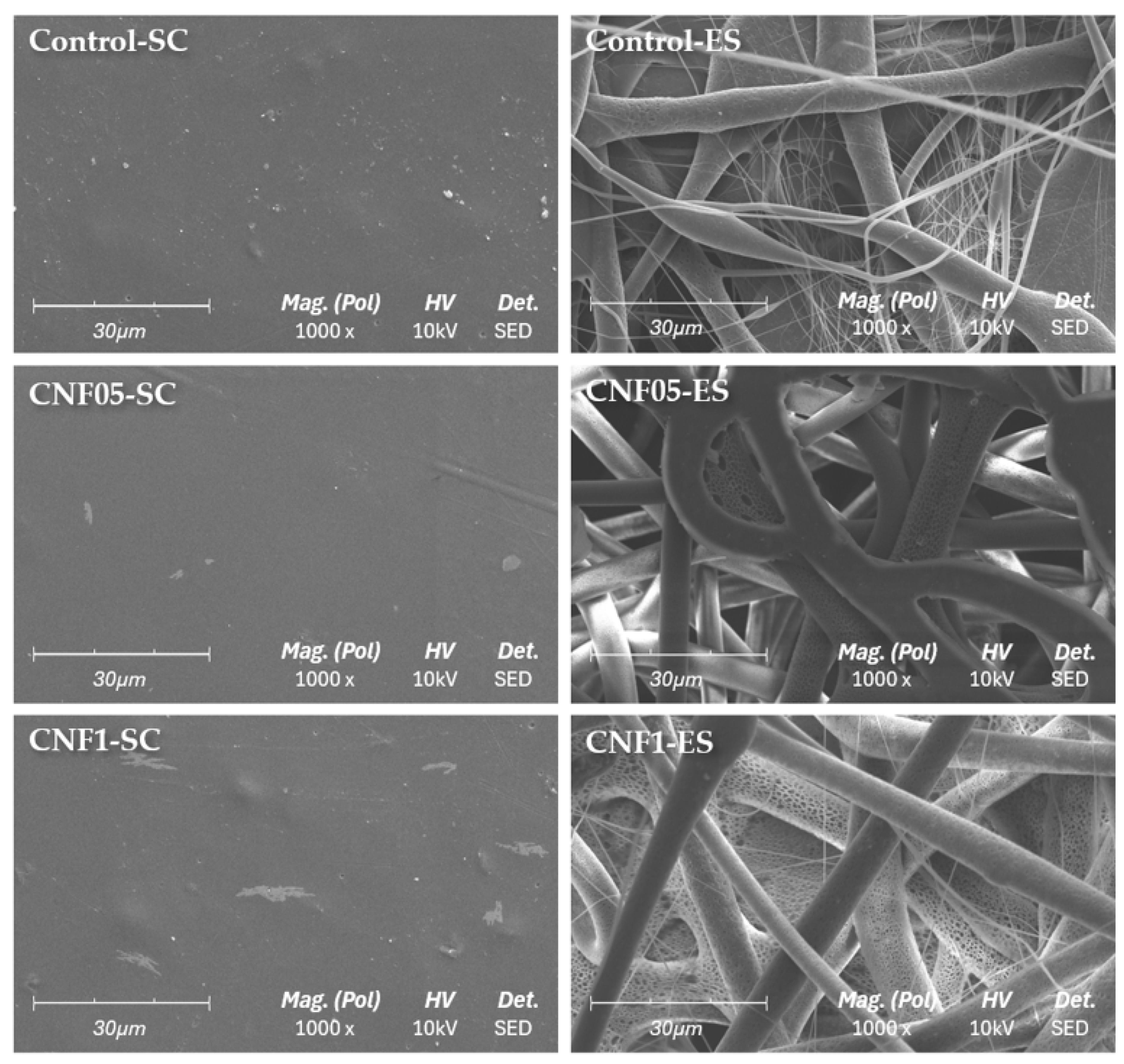

3.5. Morphological Characterisation

3.6. Thermal Stability

3.7. ATR-FTIR: Chemical and Structural Characterization

3.8. Assessment of the Performance of Packaging in HPP

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Parliament. Regulation (EU) 2025/40 of the European Parliament and the Council of 19 December 2024 on Packaging and Packaging Waste, Amending Regulation (EU) 2019/1020 and Directive (EU) 2019/904, and Repealing Directive 94/62/EC; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Volume 40. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Vinitskaia, N.; Lindstad, A.J.; Lev, R.; Kvikant, M.; Xu, C.; Leminen, V.; Li, K.D.; Pettersen, M.K.; Grönman, K. Environmental Sustainability, Food Quality and Convertibility of Bio-Based Barrier Coatings for Fibre-Based Food Packaging: A Semisystematic Review. Packg. Techn. and Sci. 2024, 38, 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofoli, N.L.; Lima, A.R.; Tchonkouang, R.D.N.; Quintino, A.C.; Vieira, M.C. Advances in the Food Packaging Production from Agri-Food Waste and By-Products: Market Trends for a Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, C.C.S.; Michelin, M.; Cerqueira, M.A.; Gonçalves, C.; Tonon, R.V.; Pastrana, L.M.; Freitas-Silva, O.; Vicente, A.A.; Cabral, L.M.C.; Teixeira, J.A. Cellulose Nanocrystals from Grape Pomace: Production, Properties and Cytotoxicity Assessment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 192, 327–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, A.R.; Cristofoli, N.L.; Rosa da Costa, A.M.; Saraiva, J.A.; Vieira, M.C. Comparative Study of the Production of Cellulose Nanofibers from Agro-Industrial Waste Streams of Salicornia Ramosissima by Acid and Enzymatic Treatment. Food and Bioprod. Process. 2023, 137, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibolla, H.; Pelissari, F.M.; Martins, J.T.; Vicente, A.A.; Menegalli, F.C. Cellulose Nanofibers Produced from Banana Peel by Chemical and Mechanical Treatments: Characterization and Cytotoxicity Assessment. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 75, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Cruz, S.; Tecante, A. Extraction and Characterization of Cellulose Nanofibers from Rose Stems (Rosa Spp.). Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 220, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebi, H.; Ghasemi, F.A.; Ashori, A. The Effect of Nanocellulose on Mechanical and Physical Properties of Chitosan-Based Biocomposites. J. Elast. Plast. 2022, 54, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Duan, G.; Zhang, G.; Yang, H.; Jiang, S.; He, S. Electrospun Functional Materials toward Food Packaging Applications: A Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamian, M.; Pajohi-Alamoti, M.; Azizian, S.; Nourian, A.; Tahzibi, H. An Electrospun Polylactic Acid Film Containing Silver Nanoparticles and Encapsulated Thymus Daenensis Essential Oil: Release Behavior, Physico-Mechanical and Antibacterial Studies. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 3450–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, N.M. Opportunities for Cellulose Nanomaterials in Packaging Films: A Review and Future Trends. J. Renew Mater. 2016, 4, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, A.; Monte, M.C.; Campano, C.; Balea, A.; Merayo, N.; Negro, C. Nanocellulose for Industrial Use: Cellulose Nanofibers (CNF), Cellulose Nanocrystals (CNC), and Bacterial Cellulose (BC); Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9780128133514. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, A.K.; Gupta, M.K.; Singh, H. PLA Based Biocomposites for Sustainable Products: A Review. Advan. Indust, and Eng. Polym. Resear. 2023, 6, 382–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani Ghomi, E.; Khosravi, F.; Saedi Ardahaei, A.; Dai, Y.; Neisiany, R.E.; Foroughi, F.; Wu, M.; Das, O.; Ramakrishna, S. The Life Cycle Assessment for Polylactic Acid (PLA) to Make It a Low-Carbon Material. Polymers 2021, 13, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.M.; Chaudry, S.; Thornton, A.W.; Haque, N.; Lau, D.; Bhuiyan, M.; Pramanik, B.K. Environmental Footprint of Polylactic Acid Production Utilizing Cane-Sugar and Microalgal Biomass: An LCA Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 496, 145132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Khan, S.M.; Shafiq, M.; Abbas, N. A Review on PLA-Based Biodegradable Materials for Biomedical Applications. Giant. 2024, 18, 100261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research Polylactic Acid Market Size & Trends. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/polylactic-acid-pla-market (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Ruz-Cruz, M.A.; Herrera-Franco, P.J.; Flores-Johnson, E.A.; Moreno-Chulim, M.V.; Galera-Manzano, L.M.; Valadez-González, A. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of PLA-Based Multiscale Cellulosic Biocomposites. J. Mater. Resear. Tech. 2022, 18, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Wu, M.; Wang, L.; Zheng, W.; Hikima, Y.; Semba, T.; Ohshima, M. Cellulose Nanofiber Reinforced Poly (Lactic Acid) with Enhanced Rheology, Crystallization and Foaming Ability. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 286, 191320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamadiala, I.; Croitoru, C.; Pop, M.A.; Roata, I.C. Enhancing Polylactic Acid (PLA) Performance: A Review of Additives in Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) Filaments. Polymers 2025, 17, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Wu, T.; Dai, Y.; Xia, Y. Electrospinning and Electrospun Nanofibers: Methods, Materials, and Applications. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 5298–5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thabet, Y.; Breitkreutz, J. Orodispersible Films: Product Transfer from Lab-Scale to Continuous Manufacturing. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 535, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, I.; Tshai, K.Y.; Enamul Hoque, M. Manufacturing of Natural Fibre-Reinforced Polymer Composites by Solvent Casting Method. In Manufacturing of Natural Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites; Salit, M., Jawaid, M., Yusoff, N., Hoque, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 331–349. ISBN 978-3-319-07944-8.

- Senthil Muthu Kumar, T.; Senthil Kumar, K.; Rajini, N.; Siengchin, S.; Ayrilmis, N.; Varada Rajulu, A. A Comprehensive Review of Electrospun Nanofibers: Food and Packaging Perspective. Compos. B Eng. 2019, 175, 107074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhussain, R.; Adebisi, A.; Conway, B.R.; Asare-Addo, K. Electrospun Nanofibers: Exploring Process Parameters, Polymer Selection, and Recent Applications in Pharmaceuticals and Drug Delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 90, 105156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, V.; Anandjiwala, R.D.; Maaza, M. The Influence of Electrospinning Parameters on the Structural Morphology and Diameter of Electrospun Nanofibers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 115, 3130–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduna, L.; Patnaik, A. Challenges Associated with the Production of Nanofibers. Processes 2024, 12, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, K.; Chandra, A.; Praveen, G.; Snigdha, S.; Roy, S.; Agatemor, C.; Thomas, S.; Provaznik, I. Electrospinning over Solvent Casting: Tuning of Mechanical Properties of Membranes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topuz, F.; Uyar, T. Electrospinning of Sustainable Polymers from Biomass for Active Food Packaging. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1266–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, A.R.; Hazarika, P.; Duarah, R.; Goswami, R.; Hazarika, S. Biodegradable Electrospun Membranes for Sustainable Industrial Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 11129–11147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Lin, X.; Ee, L.Y.; Li, S.F.Y.; Huang, M. A Review on Electrospinning as Versatile Supports for Diverse Nanofibers and Their Applications in Environmental Sensing. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2023, 5, 429–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, A.; Sadeghi, E.; Abdolmaleki, K.; Dabirian, F.; Shirvani, H.; Soltani, M. Eco-Friendly and Smart Electrospun Food Packaging Films Based on Polyvinyl Alcohol and Sumac Extract: Physicochemical, Mechanical, Antibacterial, and Antioxidant Properties. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melendez-Rodriguez, B.; Castro-Mayorga, J.L.; Reis, M.A.M.; Sammon, C.; Cabedo, L.; Torres-Giner, S.; Lagaron, J.M. Preparation and Characterization of Electrospun Food Biopackaging Films of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Derived From Fruit Pulp Biowaste. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsoumanis, K.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bolton, D.; Bover-Cid, S.; Chemaly, M.; Davies, R.; De Cesare, A.; Herman, L.; Hilbert, F.; Lindqvist, R.; et al. The Efficacy and Safety of High-Pressure Processing of Food. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Murtaza, A.; Pinto, C.A.; Saraiva, J.A.; Liu, X.; Zhu, Z. High-Pressure Processing for Food Preservation. In Innovative and Emerging Technologies in the Bio-Marine Food Sector-Applications, Regulations, and Prospects; Garcia-Vaquero, M., Rajauria, G., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 495–518. ISBN 9780128200964. [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran, C.; Jayachandran, L.E.; Kothakota, A.; Pandiselvam, R.; Balasubramaniam, V.M. Influence of High Pressure Pasteurization on Nutritional, Functional and Rheological Characteristics of Fruit and Vegetable Juices and Purees-an Updated Review. Food Control 2023, 146, 109516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.; Duarte, R.V.; Pinto, C.A.; Casal, S.; Lopes-da-Silva, J.A.; Saraiva, J.A. High Pressure and Pasteurization Effects on Dairy Cream. Foods 2023, 12, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scepankova, H.; Majtan, J.; Estevinho, L.M.; Saraiva, J.A. The High Pressure Preservation of Honey: A Comparative Study on Quality Changes during Storage. Foods 2024, 13, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM D882-18; Standard Test Method For Tensile Properties of Thin Plastic Sheeting. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM E96/E96M-15; Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- de Farias, P.M.; Barros de Vasconcelos, L.; da Silva Ferreira, M.E.; Alves Filho, E.G.; De Freitas, V.A.A.; Tapia-Blácido, D.R. Nopal Cladode as a Novel Reinforcing and Antioxidant Agent for Starch-Based Films: A Comparison with Lignin and Propolis Extract. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 614–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM E2550-21; Standard Test Method for Thermal Stability by Thermogravimetry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Liu, Y.; Liang, X.; Wang, S.; Qin, W.; Zhang, Q. Electrospun Antimicrobial Polylactic Acid/Tea Polyphenol Nanofibers For. Polymers 2018, 10, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Guan, M.; Bian, Y.; Yin, X. Multifunctional Electrospun Nanofibers for Biosensing and Biomedical Engineering Applications. Biosensors 2024, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, S.Y.; Wen, Y.; Dzenis, Y.; Leong, K.W. The Role of Electrospinning in the Emerging Field of Nanomedicine. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2006, 12, 4751–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmus, M.; Liu, J.; Wang, N.; Radacsi, N.; Zhao, Y. Nano Materials Science Hierarchically Electrospun Nano Fi Bers and Their Applications: A Review. Nano Mater. Sci. 2021, 3, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wannatong, L.; Sirivat, A.; Supaphol, P. Effects of Solvents on Electrospun Polymeric Fibers: Preliminary Study on Polystyrene. Polym. Sci. 2004, 1859, 1851–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Sun, J.; Chen, L.; Niu, P.; Yang, X.; Guo, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan Film Incorporated with Thinned Young Apple Polyphenols as an Active Packaging Material. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 163, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Luo, H.; Tang, R.; Hou, J. Preparation and Applications of Electrospun Optically Transparent Fibrous Membrane. Polymers 2021, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoll, L.; Domenek, S.; Flôres, S.H.; Marli, S.; Alessandro, B.N.; Rios, D.O. Polylactide Films Produced with Bixin and Acetyl Tributyl Citrate: Functional Properties for Active Packaging. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 138, 50302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and Mechanical Properties of PLA, and Their Functions in Widespread Applications—A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burg, K.J.L.; Holder, W.D.; Culberson, C.R.; Beiler, R.J.; Greene, K.G.; Loebsack, A.B.; Roland, W.D.; Mooney, D.J.; Halberstadt, C.R. Parameters Affecting Cellular Adhesion to Polylactide Films. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 1999, 10, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murariu, M.; Dubois, P. PLA Composites: From Production to Properties. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 17–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Bocharova, V.; Tekinalp, H.; Cheng, S.; Kisliuk, A.; Sokolov, A.P.; Kunc, V.; Peter, W.H.; Ozcan, S. Toughening of Nanocelluose/PLA Composites via Bio-Epoxy Interaction: Mechanistic Study. Mater. Des. 2018, 139, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin Rashid, A.; Haque, M.; Islam, S.M.M.; Uddin Labib, K.M.R. Nanotechnology-Enhanced Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites: Recent Advancements on Processing Techniques and Applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamróz, E.; Kulawik, P.; Kopel, P. The Effect of Nanofillers on the Functional Properties of Biopolymer-Based Films: A Review. Polymers 2019, 11, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.K.; Gupta, M.K. PLA Based Biodegradable Bionanocomposite Filaments Reinforced with Nanocellulose: Development and Analysis of Properties. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri, M.; Kim, J.T.; Shin, G.H. Synergistic Enhancement of PLA/PHA Bio-Based Films Using Tempo-Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibers, Graphene Oxide, and Clove Oil for Sustainable Packaging. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 42, 111531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Duan, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, R.; Qin, C.; Li, Q. Role of Silane Compatibilization on Cellulose Nanofiber Reinforced Poly (Lactic Acid) (PLA) Composites with Superior Mechanical Properties, Thermal Stability, and Tunable Degradation Rates. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 297, 139836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciotti, I.; Fortunati, E.; Puglia, D.; Kenny, J.M.; Nanni, F. Effect of Silver Nanoparticles and Cellulose Nanocrystals on Electrospun Poly(Lactic) Acid Mats: Morphology, Thermal Properties and Mechanical Behavior. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 103, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonoobi, M.; Harun, J.; Mathew, A.P.; Oksman, K. Mechanical Properties of Cellulose Nanofiber (CNF) Reinforced Polylactic Acid (PLA) Prepared by Twin Screw Extrusion. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2010, 70, 1742–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.P.; Yang, S.; Gao, X.R.; Chen, S.P.; Xu, L.; Zhong, G.J.; Huang, H.D.; Li, Z.M. Constructing Robust Chain Entanglement Network, Well-Defined Nanosized Crystals and Highly Aligned Graphene Oxide Nanosheets: Towards Strong, Ductile and High Barrier Poly(Lactic Acid) Nanocomposite Films for Green Packaging. Compos. B Eng. 2021, 222, 109048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.H.; Hu, M.H.; Wang, J.F.; Hu, J.J. Enhancing the Flexibility and Hydrophilicity of PLA via Polymer Blends: Electrospinning vs. Solvent Casting. Polymers 2025, 17, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwatake, A.; Nogi, M.; Yano, H. Cellulose Nanofiber-Reinforced Polylactic Acid. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 2103–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Ang, B.C.; Andriyana, A.; Afifi, A.M. A Review on Fabrication of Nanofibers via Electrospinning and Their Applications. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morel, A.; Domaschke, S.; Urundolil Kumaran, V.; Alexeev, D.; Sadeghpour, A.; Ramakrishna, S.N.; Ferguson, S.J.; Rossi, R.M.; Mazza, E.; Ehret, A.E.; et al. Correlating Diameter, Mechanical and Structural Properties of Poly(L-Lactide) Fibres from Needleless Electrospinning. Acta Biomater. 2018, 81, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guivier, M.; Chevigny, C.; Domenek, S.; Casalinho, J.; Perré, P.; Almeida, G. Water Vapor Transport Properties of Bio-Based Multilayer Materials Determined by Original and Complementary Methods. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gardner, D.J.; Stark, N.M.; Bousfield, D.W.; Tajvidi, M.; Cai, Z. Moisture and Oxygen Barrier Properties of Cellulose Nanomaterial-Based Films. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oesef, K.; Cranston, E.D.; Abdin, Y. Current Advances in Processing and Modification of Cellulose Nanofibrils for High-Performance Composite Applications. Mater. Des. 2024, 247, 113417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solhi, L.; Guccini, V.; Heise, K.; Solala, I.; Niinivaara, E.; Xu, W.; Mihhels, K.; Kröger, M.; Meng, Z.; Wohlert, J.; et al. Understanding Nanocellulose-Water Interactions: Turning a Detriment into an Asset. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 1925–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esakkimuthu, E.S.; Ponnuchamy, V.; Sipponen, M.H.; DeVallance, D. Elucidating Intermolecular Forces to Improve Compatibility of Kraft Lignin in Poly(Lactic Acid). Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1347147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bikiaris, N.D.; Koumentakou, I.; Samiotaki, C.; Meimaroglou, D.; Varytimidou, D.; Karatza, A.; Kalantzis, Z.; Roussou, M.; Bikiaris, R.D.; Papageorgiou, G.Z. Recent Advances in the Investigation of Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) Nanocomposites: Incorporation of Various Nanofillers and Their Properties and Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeratipinit, K.; Wijaranakul, P.; Wanmolee, W.; Hararak, B. Preparation of High-Toughness Cellulose Nanofiber/Polylactic Acid Bionanocomposite Films via Gel-like Cellulose Nanofibers. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 26159–26167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, E.S.; El Awad Azrak, S.M.; Ng, X.Y.; Cho, W.; Schueneman, G.T.; Moon, R.J.; Fox, D.M.; Youngblood, J.P. Mechanical Enhancement of Cellulose Nanofibril (CNF) Films through the Addition of Water-Soluble Polymers. Cellulose 2021, 28, 6449–6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeb, M.R.; Ramezani-Dakhel, H.; Khonakdar, H.A.; Heinrich, G.; Wagenknecht, U. A Comparative Study on Curing Characteristics and Thermomechanical Properties of Elastomeric Nanocomposites: The Effects of Eggshell and Calcium Carbonate Nanofillers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013, 127, 4241–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, J.A.A.; Benítez, J.J.; Guerrero, A.; Romero, A. Sustainable Integration of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Enhancing Properties of Poly(ε-Caprolactone) Electrospun Nanofibers and Cast Films. Coatings 2023, 13, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Wang, L.F.; Rhim, J.W. Effect of Melanin Nanoparticles on the Mechanical, Water Vapor Barrier, and Antioxidant Properties of Gelatin-Based Films for Food Packaging Application. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 21, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatafora Salazar, A.S.; Sáenz Cavazos, P.A.; Mújica Paz, H.; Valdez Fragoso, A. External Factors and Nanoparticles Effect on Water Vapor Permeability of Pectin-Based Films. J. Food Eng. 2019, 245, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argel-Pérez, S.; Velásquez-Cock, J.; Zuluaga, R.; Gómez-Hoyos, C. Improving Hydrophobicity and Water Vapor Barrier Properties in Paper Using Cellulose Nanofiber-Stabilized Cocoa Butter and PLA Emulsions. Coatings 2024, 14, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Kang, X.; Liu, Y.; Feng, F.; Zhang, H. Characterization of Gelatin/Zein Films Fabricated by Electrospinning vs Solvent Casting. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 74, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S.M.; Ferreira, D.P.; Teixeira, P.; Ballesteros, L.F.; Teixeira, J.A.; Fangueiro, R. Active Natural-Based Films for Food Packaging Applications: The Combined Effect of Chitosan and Nanocellulose. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 177, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.; Li, B. Impact of the Incorporation of Nano-Sized Cellulose Formate on the End Quality of Polylactic Acid Composite Film. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zeng, L.; Qiao, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Ding, J. Fabrication of Electrospun Polymer Nanofibers with Diverse Morphologies. Molecules 2019, 24, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ye, Z.; Hou, P. Biodegradable PLA/TPU Blends with Improved Mechanical Properties. Mater. Lett. 2025, 387, 138205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M.; Khan, S.M.; Shafiq, M.; Al-Dossari, M.; Alqsair, U.F.; Khan, S.U.; Khan, M.I. Comparative Study of PLA Composites Reinforced with Graphene Nanoplatelets, Graphene Oxides, and Carbon Nanotubes: Mechanical and Degradation Evaluation. Energy 2024, 308, 132917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Zainudin, E.S.; Zuhri, M.Y.M. Physical, Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Novel Bamboo/Kenaf Fiber-Reinforced Polylactic Acid (PLA) Hybrid Composites. Compos. Commun. 2024, 51, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaffaro, R.; Lopresti, F. Properties-Morphology Relationships in Electrospun Mats Based on Polylactic Acid and Graphene Nanoplatelets. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2018, 108, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.J.; Yu, X.T.; Huang, Z.; Liu, D.F. Interfacial Improvements in Cellulose Nanofibers Reinforced Polylactide Bionanocomposites Prepared by in Situ Reactive Extrusion. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 2352–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, S.; Liu, G.; Cheng, W.; Han, G.; Bai, L. Electrospun Poly(Lactic Acid)-Based Fibrous Nanocomposite Reinforced by Cellulose Nanocrystals: Impact of Fiber Uniaxial Alignment on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortunati, E.; Peltzer, M.; Armentano, I.; Torre, L.; Jiménez, A.; Kenny, J.M. Effects of Modified Cellulose Nanocrystals on the Barrier and Migration Properties of PLA Nano-Biocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 948–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafia-Araga, R.A.; Sabo, R.; Nabinejad, O.; Matuana, L.; Stark, N. Influence of Lactic Acid Surface Modification of Cellulose Nanofibrils on the Properties of Cellulose Nanofibril Films and Cellulose Nanofibril–Poly (Lactic Acid) Composites. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abera, G. Review on High-Pressure Processing of Foods. Cogent. Food Agric. 2019, 5, 1568725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muntean, M.-V.; Marian, O.; Barbieru, V.; Cătunescu, G.M.; Ranta, O.; Drocas, I.; Terhes, S. High Pressure Processing in Food Industry–Characteristics and Applications. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 10, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aganovic, K.; Hertel, C.; Vogel, R.F.; Johne, R.; Schlüter, O.; Schwarzenbolz, U.; Jäger, H.; Holzhauser, T.; Bergmair, J.; Roth, A.; et al. Aspects of High Hydrostatic Pressure Food Processing: Perspectives on Technology and Food Safety. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 3225–3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Rubio, A.; Lagarón, J.M.; Hernández-Muñoz, P.; Almenar, E.; Catalá, R.; Gavara, R.; Pascall, M.A. Effect of High Pressure Treatments on the Properties of EVOH-Based Food Packaging Materials. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2005, 6, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.; González-Martínez, C.; Chiralt, A. Combination Of Poly(Lactic) Acid and Starch for Biodegradable Food Packaging. Materials 2017, 10, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoine, N.; Desloges, I.; Dufresne, A.; Bras, J. Microfibrillated Cellulose-Its Barrier Properties and Applications in Cellulosic Materials: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 735–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulkhani, A.; Hosseinzadeh, J.; Ashori, A.; Dadashi, S. Preparation and Characterization of Modified Celllose Nanofibers Reinforced Polylactic Acid Nanocomposite. Polym. Test. 2014, 35, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreira, L.; Resek, E.; Rodrigues, M.J.; Rocha, M.I.; Pereira, H.; Bandarra, N.; da Silva, M.M.; Varela, J.; Custódio, L. Halophytes: Gourmet Food with Nutritional Health Benefits? J. Food Comp. Anal. 2017, 59, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.R.; Castañeda-Loaiza, V.; Salazar, M.; Nunes, C.; Quintas, C.; Gama, F.; Pestana, M.; Correia, P.J.; Santos, T.; Varela, J.; et al. Influence of Cultivation Salinity in the Nutritional Composition, Antioxidant Capacity and Microbial Quality of Salicornia Ramosissima Commercially Produced in Soilless Systems. Food. Chem. 2020, 333, 127525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Film | Opacity (%) | Colour | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | ΔE* | ||

| Control-SC | 7.98 ± 0.37 a | 33.1 ± 0.14 a | −0.51 ± 0.04 ab | 2.03 ± 0.08 b | |

| CNF05-SC | 8.57 ± 0.09 a | 33.4 ± 0.19 a | −0.52 ± 0.03 ab | 1.82 ± 0.20 b | 0.39 a |

| CNF1-SC | 8.49 ± 0.12 a | 33.5 ± 0.10 a | −0.51 ± 0.04 ab | 1.78 ± 0.10 b | 0.45 a |

| Control-ES | 37.0 ± 1.32 b | 54.1 ± 0.75 b | −0.38 ± 0.20 a | −1.42 ± 0.31 a | |

| 1CNF05-ES | 37.2 ± 1.02 b | 55.8 ± 0.05 b | −0.80 ± 0.06 a | −1.30 ± 0.13 a | 5.88 b |

| CNF1-ES | 42.2 ± 2.80 c | 68.7 ± 0.66 c | −0.46 ± 0.13 a | −1.08 ± 0.49 a | 8.90 c |

| Film | Thickness (mm) | TS (MPa) | EB (%) | YM (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control-SC | 0.06 ± 0.01 ab | 17.4 ± 1.66 ab | 48.8 ± 1.43 c | 35.6 ± 3.17 a |

| CNF05-SC | 0.07± 0.01 ab | 18.9 ± 0.21 ab | 44.7 ± 1.58 bc | 42.4 ± 1.17 a |

| CNF1-SC | 0.06 ± 0.02 a | 21.6 ± 1.98 bc | 41.8 ± 0.28 b | 51.7 ± 4.64 a |

| Control-ES | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 13.9 ± 2.41 a | 7.71 ± 0.17 a | 180 ± 32.4 ab |

| CNF05-ES | 0.11 ± 0.01 c | 25.7 ± 2.33 c | 6.89 ± 1.49 a | 400 ± 133.7 c |

| CNF1-ES | 0.15 ± 0.01 d | 23.6 ± 1.86 bc | 7.67 ± 1.62 a | 318 ± 55.7 d |

| Film | Moisture (%) | Solubility (%) | WVP * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control-SC | 7.49 ± 0.65 c | 0.90 ± 0.38 a | 0.07 ± 0.01 a |

| CNF05-SC | 8.15 ± 0.79 c | 0.90 ± 0.88 a | 0.08 ± 0.01 a |

| CNF1-SC | 7.95 ± 0.77 c | 0.45 ± 0.19 a | 0.06 ± 0.01 a |

| Control-ES | 3.51 ± 0.95 a | 2.16 ± 0.46 a | 1.28 ± 0.01 b |

| CNF05-ES | 6.42 ± 0.99 bc | 1.90 ± 0.51 a | 1.77 ± 0.01 c |

| CNF1-ES | 4.62 ± 0.93 ab | 1.81 ± 0.58 a | 2.39 ± 0.02 d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lima, A.R.; Cristofoli, N.L.; Delahousse, I.; Amaral, R.A.; Saraiva, J.A.; Vieira, M.C. PLA-Based Films Reinforced with Cellulose Nanofibres from Salicornia ramosissima By-Product with Proof of Concept in High-Pressure Processing. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13247. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413247

Lima AR, Cristofoli NL, Delahousse I, Amaral RA, Saraiva JA, Vieira MC. PLA-Based Films Reinforced with Cellulose Nanofibres from Salicornia ramosissima By-Product with Proof of Concept in High-Pressure Processing. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13247. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413247

Chicago/Turabian StyleLima, Alexandre R., Nathana L. Cristofoli, Inès Delahousse, Renata A. Amaral, Jorge A. Saraiva, and Margarida C. Vieira. 2025. "PLA-Based Films Reinforced with Cellulose Nanofibres from Salicornia ramosissima By-Product with Proof of Concept in High-Pressure Processing" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13247. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413247

APA StyleLima, A. R., Cristofoli, N. L., Delahousse, I., Amaral, R. A., Saraiva, J. A., & Vieira, M. C. (2025). PLA-Based Films Reinforced with Cellulose Nanofibres from Salicornia ramosissima By-Product with Proof of Concept in High-Pressure Processing. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13247. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413247