1. Introduction

Active Magnetic Bearings (AMBs) are high-performance support devices that use controllable electromagnetic forces to achieve non-contact rotor suspension. The most prominent advantage of AMBs is their active controllability. Compared to conventional mechanical bearings, AMBs require no mechanical contact, thereby eliminating wear and the need for lubrication, which enables their application under extreme conditions such as vacuum, high temperature, and high rotational speed. Furthermore, during operation the AMB stiff ness and damping can be adjusted in real time [

1]. Because of this active controllability, AMB systems are capable of online diagnostics and suppression of various vibrations and are particularly effective at compensating for rotor mass imbalance, which is a primary source of excitation [

2]. As a result, AMB technology has been widely applied in areas demanding extremely high rotational speeds and precision, including high-speed turbomachinery, aerospace engines, flywheel energy storage systems, and molecular pumps [

3].

However, the engineering application of AMB technology still faces inherent challenges, such as highly complex control systems, high hardware cost, and stringent demands on system reliability and robustness [

4]. A schematic of a typical five-degree of-freedom AMB rotor system is shown in

Figure 1, where its core components are radial and axial magnetic bearings, displacement sensors, power amplifiers, and digital controllers—working together to precisely suspend and control the rotor.

Rotor mass imbalance is an unavoidable core issue in AMB design and operation, originating from manufacturing tolerances, material in homogeneity, and wear [

6]. When an imbalanced rotor spins at high speed, it generates a periodic centrifugal force that is synchronous with the rotational speed, which is commonly referred to as the imbalance excitation force. The magnitude of this force is proportional to the imbalanced mass and the square of the rotational speed, typically expressed as

where m is the imbalanced mass, e is the eccentricity, ω is the angular speed, and φ is the imbalance phase angle. If left uncontrolled, imbalance vibration can severely degrade system performance: it reduces rotational accuracy, causes excessive machine vibration and noise, and may induce resonance near critical speeds. Such resonance may lead to rotor collision with backup bearings and catastrophic failure. These potential hazards provide direct motivation for introducing imbalance vibration control techniques. In the field of imbalance vibration control, two fundamental strategies have been developed: inertia force minimization control (often called automatic balancing) and vibration displacement minimization control (imbalance compensation). Inertia force minimization control aims to make the magnetic bearing insensitive to synchronous excitation forces, thereby allowing the rotor to rotate freely around its principal axis of inertia. The primary benefit of this strategy is that it significantly attenuates the synchronous excitation force transmitted to the base—theoretically approaching zero—thereby minimizing power consumption and enhancing system reliability. Although the rotor’s geometric center will exhibit a steady-state offset, the low power consumption and minimal base vibration make this strategy particularly suitable for scenarios with strict energy efficiency requirements [

7].

Conversely, vibration displacement minimization control actively applies an electromagnetic force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to the imbalance force, forcing the rotor’s geometric center to coincide with the center of the stator [

8]. The objective is to achieve extremely high rotational precision, theoretically realizing zero displacement. However, this requires high power consumption and imposes stringent demands on control bandwidth and hardware performance. Therefore, this strategy is primarily used in applications requiring extremely high precision, such as machine tool spindles and high-precision optical systems.

The above comparison is summarized in

Table 1. This paper focuses on rotor imbalance vibration control and systematically reviews related techniques. The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 and

Section 3, respectively, detail the key techniques of the two core control strategies inertia force minimization control and vibration displacement minimization controllaying the theoretical foundation for the subsequent content.

Section 4 discusses advanced and intelligent algorithms, including adaptive control and machine learning, highlighting their potential to enhance system performance and robustness.

Section 5 concludes the paper and presents future research directions and challenges stringent requirements on control bandwidth and hardware performance.

In addition to summarizing the theoretical foundations, this review also discusses practical examples and engineering advantages associated with the implementation of these control strategies, aiming to provide valuable guidance for real-world magnetic bearing applications.

2. Inertia Force Minimization Control Techniques

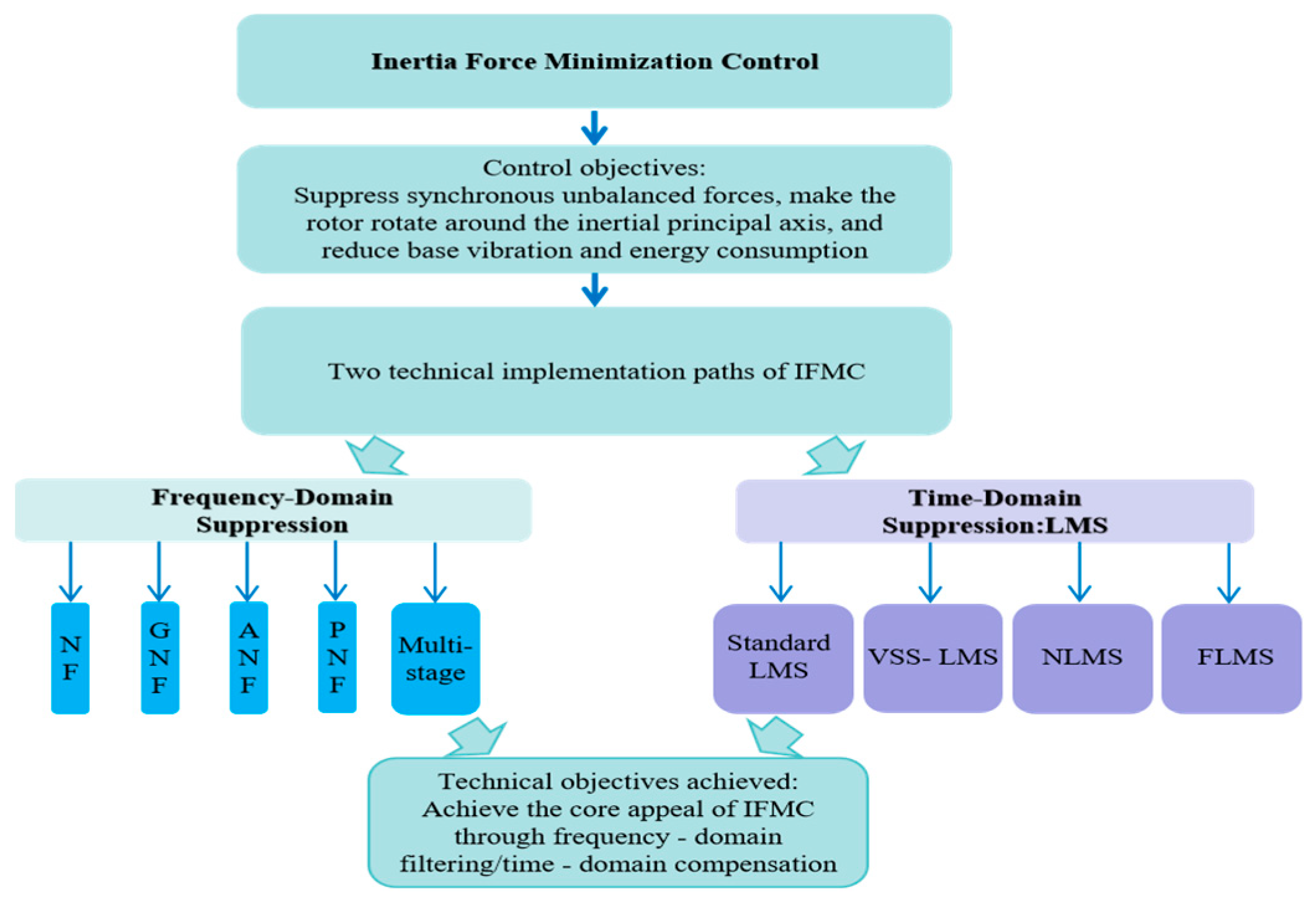

Inertia Force Minimization Control (IFMC), also referred to as automatic balancing, aims to minimize the synchronous electromagnetic forces exerted by the magnetic bearings in response to rotor imbalance. Rather than actively canceling the unbalance force, IFMC desensitizes the control system to synchronous displacement components, allowing the rotor to rotate freely about its principal axis of inertia.

As a result, the forces transmitted to the bearing housing are significantly reduced, leading to lower power consumption and minimized base vibration. This approach is particularly suitable for applications where energy efficiency and structural vibration suppression are prioritized over strict rotational accuracy.

This Section focuses on two mainstream methods: frequency-domain suppression—specifically, notch filters—and time-domain suppression—namely, adaptive filtering algorithms (the Least Mean Square, LMS, algorithm and its variants). These two approaches represent an evolutionary path from fixed-structure solutions to methods with enhanced adaptability to complex dynamic conditions, reflecting an ongoing trade-off among performance, robustness, and complexity.

Figure 2 provides a block diagram of IFMC and summarizes its two implementation paths.

2.1. Frequency-Domain Suppression

In AMB rotor systems, imbalance force is a major source of synchronous vibration. Because the imbalance components are concentrated in narrow frequency bands around the rotational frequency and its harmonics, frequency-domain selective suppression becomes highly effective. Notch filters are one of the most widely used tools for this purpose. Their core principle is to generate deep attenuation at specific frequencies, thereby weakening or eliminating synchronous components while leaving the remaining frequency spectrum largely unaffected.

The development of notch filtering techniques has progressed from the Standard Notch Filter (NF) to more advanced structures such as the Generalized Notch Filter (GNF), the Adaptive Notch Filter (ANF), and the Phase-Notch Filter (PNF), and further toward multi-stage and multi-channel implementations. These advancements reflect continuous improvements in parameter tuning, adaptability, and system robustness. Overall, this evolution demonstrates the engineering community’s pursuit of an optimal balance between performance, robustness, and implementation complexity. The following subsection provides a detailed review of the application and development of notch filters in AMB systems in chronological and technical order.

2.1.1. Historical Background and Standard Notch Filter (NF)

Notch filters can trace their origins to the early 20th century. In 1922, Campbell introduced the concept of wave filters, opening the door to research on frequency-selective filters [

9]. In 1923, Zobel refined the design methods for constant-K and composite filters, leading these filter types gradually into engineering practice [

10]. These early developments were primarily applied to communications and signal processing but laid a solid theoretical foundation for later adoption in vibration control.

With the emergence and development of magnetic bearings, researchers such as Schweitzer and Maslen were the first to introduce notch filters into AMB systems [

11]. They found that adding a notch filter element into the feedback loop can effectively attenuate synchronous components in displacement or current signals, thereby preventing the controller from responding excessively to imbalance forces. This approach quickly gained widespread adoption due to its simple structure, ease of implementation, and good real-time performance.

A standard notch filter is a narrowband band-stop filter whose transfer function is determined by its center frequency and damping ratio. The center frequency sets the notch location, while the damping ratio determines the bandwidth and depth of attenuation. The advantage of this filter is its ability to achieve deep attenuation of a specific frequency component while keeping other frequency bands largely unaffected. For example, Zhou et al. applied a notch filter-based control strategy in high-speed AMB operation and significantly suppressed synchronous vibration, improving system stability and robustness [

12]. However, the limitations of the standard notch filter are also evident:

Fixed frequency: when the rotor speed changes cause the synchronous frequency to shift, the filtering effect quickly deteriorates.

Phase lag: increasing the notch depth introduces significant phase delay, reducing the phase margin of the closed-loop system.

Therefore, the standard notch filter is more suitable for constant-speed operation and shows insufficient robustness under variable-speed and across-critical conditions.

In summary, the standard notch filter represents a “high performance, low complexity” strategy, but its limited robustness motivates further development.

2.1.2. Generalized Notch Filter (GNF): Introduction of Frequency-Adaptive Mechanisms

To address the shortcomings of the standard notch filter under variable-speed conditions, researchers proposed the Generalized Notch Filter (GNF). The GNF retains the notch filtering functionality while adding parameter adaptation and frequency estimation mechanisms, enabling the notch center to dynamically adjust with rotor speed and thereby improving suppression performance over a wide speed range.

To overcome the limitations of fixed-frequency filtering, the Generalized Notch Filter (GNF) was developed to introduce frequency adaptability. Early implementations, such as the adjustable notch design by Beex [

13] and its application to periodic disturbance control by Smith et al. [

14], demonstrated effectiveness in SISO systems. However, as AMB applications moved towards complex rotor dynamics, the need for spatial decoupling became apparent. Consequently, Herzog et al. [

15] extended the GNF framework to Multi-Input Multi-Output (MIMO) systems, utilizing a sensitivity adjustment matrix to optimize pole placement. This transition marked a shift from simple signal filtering to comprehensive system-level stability control.

There have been a series of significant contributions by other researchers. For example, Sun et al. proposed an online estimation method based on measured sensitivity functions that does not rely on an exact system model, achieving frequency adaptation and excellent performance over a wide speed range [

16]. Borio proposed a real-time parameter update method based on the stochastic gradient algorithm, improving the filter’s response speed to frequency drift [

17]. Ye utilized pole-zero configuration and trajectory analysis to establish a systematic stability design framework, providing clearer theoretical guidance for filter design [

18]. More recent work includes Nevaranta’s adaptive MIMO-GNF to handle model uncertainties [

19] and Li Ming’s fast frequency-tracking algorithm for non-stationary disturbances [

20]. These studies enable the GNF to handle more complex operating conditions.

Compared to the standard NF, the GNF has significantly enhanced robustness and remains effective under variable-speed and non-stationary conditions; however, its computational complexity and implementation difficulty are also higher, especially in multivariable and real-time control contexts where hardware and algorithm overhead increase markedly.

2.1.3. Adaptive Notch Filter (ANF): Dynamic Frequency Locking

Although the GNF improved the filter’s adaptability to frequency drift, its parameter adjustment still has delays. To further improve performance, researchers proposed the Adaptive Notch Filter (ANF). The ANF’s core feature is the use of real-time frequency estimation algorithms (such as phase-locked loops (PLL), LMS-based estimators, second-order generalized integrator frequency-locked loops (SOGI-FLL), etc.) to dynamically adjust the notch filter parameters, thereby ensuring synchronous disturbance suppression in non-stationary conditions like start-up and acceleration.

For instance, one method based on an improved dual second-order generalized integrator frequency-locked loop covers the full speed range and achieves efficient imbalance suppression even if the speed sensor fails [

21]. Another optimized notch filter significantly reduced housing vibration in high-speed motor experiments, enhancing system stability at high speeds [

22]. A strategy combining a state observer with an ANF-based current suppression was shown to effectively mitigate the impact of current distortion on AMB performance [

23]. Yet another approach combined zero-displacement control with notch compensation, achieving a dual suppression mechanism of displacement notching and feedforward compensation, and significantly reducing the amplitude of the resultant force [

24].

The ANF exhibits strong robustness over a wide speed range and in start-stop and non-stationary conditions, marking a significant advancement in notch filter technology. However, its disadvantages are also evident: it is sensitive to parameter tuning, its performance degrades in noisy environments, and its adaptive convergence speed is difficult to guarantee. In the trade-off among performance, robustness, and complexity, the ANF improves robustness relative to GNF but also introduces additional complexity.

2.1.4. Phase-Shifted Notch Filter (PNF): Phase Compensation Across Critical Speeds

Another core challenge of notch filters is phase lag. As the notch depth increases, the system’s phase margin significantly decreases, and instability is especially likely during across-critical-speed operation [

25]. This phase delay issue has been identified as a common obstacle in engineering applications of notch filters.

To address this problem, researchers proposed the Phase-Shifted Notch Filter (PNF). The PNF adds a phase-shifting adjustment and signal recombination stage to the traditional notch filter structure, ensuring that the compensation signal is strictly out-of-phase with the imbalance force, thereby achieving effective cancellation.

In practice, various PNF-based methods have been developed. For example, one PNF design effectively avoided oscillations near the critical speed [

26]; another approach combining complex-phase-shift notch filtering with feedforward control achieved a 94.1% imbalance suppression rate in experiments [

27]. Further developments include a full-frequency adaptive method based on PNF [

28] and a control strategy combining PNF with feedforward compensation [

29]. Both significantly enhanced the dynamic response capability of the system under frequency drift and complex conditions.

Compared with NF, GNF, and ANF, the PNF introduces a phase compensation mechanism and addresses the long-standing phase lag problem that has troubled engineering practice. However, its design complexity and parameter tuning difficulty are also higher, requiring more precise modeling and experimental validation.

2.1.5. Multi-Stage and Multi-Channel Structures: Systematic Solutions for Complex Conditions

In wide speed ranges and non-stationary conditions, a magnetic bearing rotor often encounters multiple mode excitations and multiple harmonic disturbances simultaneously. A single notch filter struggles to balance suppression depth, control bandwidth, and closed-loop stability. Therefore, research has gradually shifted to systematic strategies involving multi-stage and multi-channel designs.

In multi-stage designs, one study proposed a two-stage notch scheme that uses different filter parameters for low- and high-speed ranges to ensure effective suppression across speeds [

30]. Another approach combined cross-feedback notch filters with distributed notch filters to achieve effective imbalance suppression over a wide speed range, balancing vibration suppression precision with stability [

31].

In multi-channel designs, parallel arrangements of notch filters have been explored. For instance, a parallel-phase-shift notch filter was proposed to enhance suppression of synchronous vibrations in different directions [

32]. Researchers have also used a parallel LMS-based multi-harmonic suppression method to simultaneously control multi-frequency imbalance vibrations, and combined parallel adaptive notch filters with cascaded multi-frequency notch filters to significantly improve overall suppression of synchronous currents and vibrations [

33].

These studies indicate that multi-stage and multi-channel designs, through modular and collaborative operation, can simultaneously improve suppression effectiveness, convergence speed, and system stability under complex conditions, but at the cost of significantly increased algorithmic and implementation complexity.

2.1.6. Parameter Tuning and Structural Innovations

The performance of a notch filter depends not only on its core mechanism but also heavily on key parameter tuning and dynamic adjustment capabilities. Recent research has moved from “static design” towards “dynamic optimization”, significantly enhancing adaptability and robustness. As summarized in

Table 2, different notch filter variants exhibit distinct trade-offs in implementation complexity, robustness, and applicable operating conditions.

For example, Peng et al. proposed a universal structural design method that flexibly adjusts the center frequency, bandwidth, and pole-zero distribution to adapt to different dynamic characteristics [

34]. Li et al. introduced a T-matrix approach to finely coordinate the poles and zeros of the notch filter, improving stability margins across different systems [

35]. Cai et al. proposed an adjustable notch filter capable of dynamically tuning its depth and center frequency, effectively suppressing synchronous harmonic currents caused by mass imbalance in AMB systems and significantly enhancing system precision [

36]. Gong et al. developed a dual-parameter tunable notch filter that independently adjusts the center frequency and damping ratio, and combined it with optimization methods like fuzzy control to achieve sustained effective suppression over a wide speed range [

37].

These developments indicate that notch filter design has evolved from single-parameter tuning to multi-parameter coordinated optimization and is gradually integrating intelligent methods to achieve higher levels of adaptability and robustness.

2.2. Time-Domain Suppression: Adaptive Filtering Algorithms (LMS and Variants)

In contrast to the fixed-structure frequency-domain notch filter methods, time-domain suppression methods emphasize real-time modeling and compensation of imbalance components through online learning and iterative adjustment. Among these, the Least Mean Square (LMS) algorithm and its derived variants are the most representative approaches. With their simple structure, high computational efficiency, and ease of hardware implementation, LMS algorithms have been widely researched and applied in AMB imbalance vibration control.

However, as the application environment has expanded from constant-speed to complex conditions such as variable speed, across-critical operation, and multiple harmonics, the limitations of the traditional LMS have become apparent. This has driven the development of various improved algorithms, including variable step-size, normalized, secondary-path compensation, and nonlinear extensions. These evolutions reflect the trade-offs and optimizations among convergence speed, steady-state accuracy, robustness, and implementation complexity—the core concerns of time-domain suppression research.

2.2.1. Standard LMS Algorithm and Limitations

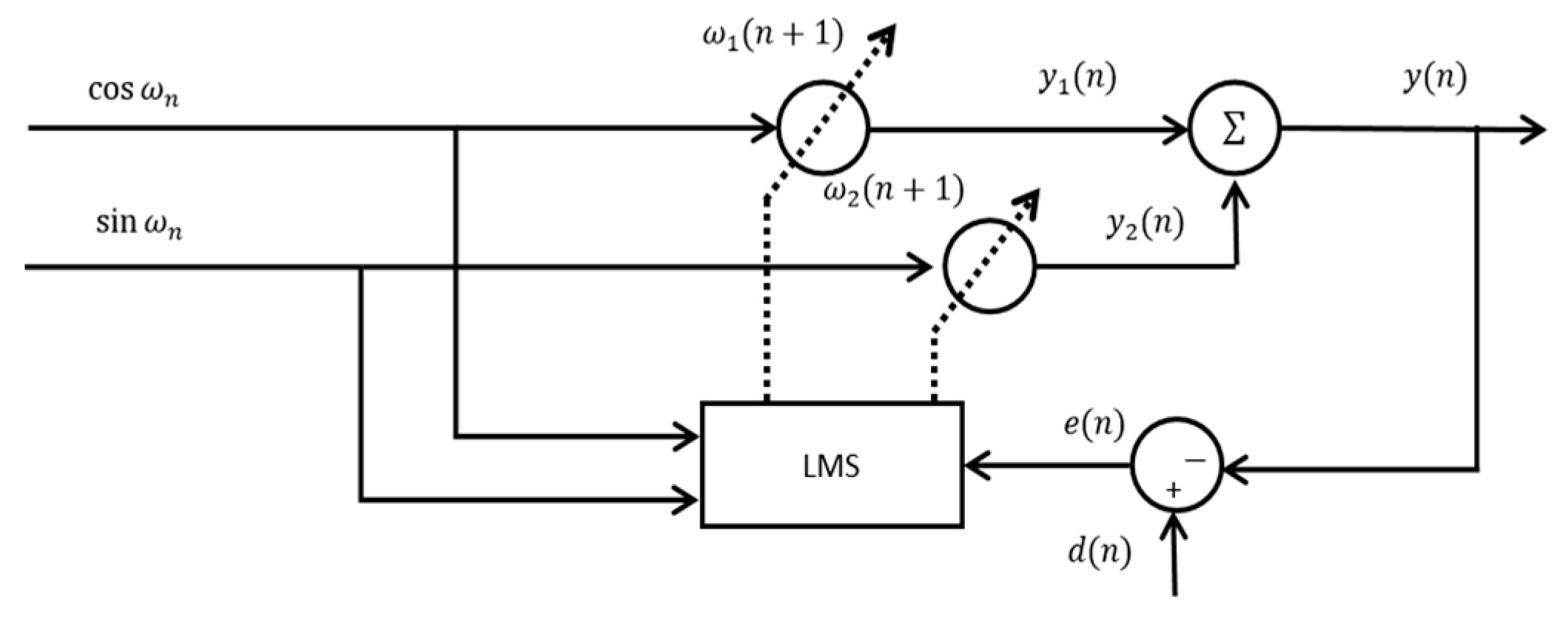

Figure 3 illustrates the basic structure of the LMS-based time-domain suppression method. A rotor-speed-synchronous signal is used as the reference input u(n). The adaptive filter generates the compensation output y(n), which represents the estimated synchronous vibration component. By comparing the measured displacement signal d(n) with the compensation output, the error signal e(n) is obtained and used to update the filter weights according to the gradient descent rule. This iterative learning process enables the controller to gradually converge to the optimal compensation parameters and effectively attenuate the imbalance-induced synchronous vibration.

The standard LMS algorithm, proposed by Widrow and Hoff [

38], is based on the minimum mean-square error criterion and iteratively updates the filter weights to approximate the desired signal. Its basic update formula is

where e(n) is the current error, μ is the step-size parameter, and u(n) is the input signal. The algorithm iteratively reduces the mean-square error via a gradient descent approach.

In AMB systems, the LMS is typically implemented by using a rotational-speed synchronous signal as the reference input, and the filter generates a compensation signal to cancel the rotor’s synchronous vibration. Experiments and simulations have shown that the LMS effectively suppresses the first-order synchronous component under constant-speed conditions. For example, several studies demonstrated the efficacy of the standard LMS in compensating for imbalance vibration in constant-speed conditions, thereby validating its utility in AMB applications [

39,

40]. These studies laid the foundation for the application of LMS in AMB systems.

However, the standard LMS also has significant limitations:

Convergence speed depends on input power: Under high-power input, the algorithm may diverge, while under low-power input, convergence is much slower.

Sensitivity to input autocorrelation: When the input signal is highly correlated, convergence slows and the algorithm may get trapped in local minima.

Step-size selection trade-off: A large step size favors fast convergence but results in large steady-state error, whereas a small step size yields high steady-state precision but poor dynamic performance.

Frequency mismatch problem: During speed fluctuations or frequency drift, a fixed-structure LMS struggles to maintain stable suppression. These issues limit the practicality of the standard LMS in complex conditions, spurring the development of various improved algorithms.

2.2.2. LMS Algorithm Improvement Directions

The conventional least mean square (LMS) algorithm, while simple and widely used, often faces challenges such as a trade-off between convergence speed and steady-state accuracy, sensitivity to signal amplitude, and limited adaptability under time-varying or nonlinear conditions. To overcome these limitations, various improved LMS algorithms have been developed. These improvements generally focus on dynamically adjusting the step size, normalizing input energy, compensating for secondary dynamic paths, and integrating intelligent optimization mechanisms. The main categories of these enhancements are summarized as follows:

- (a)

Variable Step-Size LMS (VSS-LMS)

To address the inability of a fixed step size to balance convergence speed and steady-state accuracy, the variable step-size LMS was proposed. The basic idea is to dynamically adjust the step size based on the error signal: increase the step size when the error is large to speed up convergence, and decrease it as the error diminishes to reduce steady-state error.

For example, one method uses the instantaneous error energy to adjust the step size, significantly improving convergence speed and steady-state accuracy [

41]. Nonlinear step-size adjustment functions have been designed to maintain good adaptability under rapid speed changes during start-up and shutdown [

42]. There are also approaches that couple the step size with the frequency domain characteristics to improve robustness against multi-frequency disturbances [

43].

In addition, fuzzy logic has been introduced into the VSS-LMS framework: for instance, the error and its rate of change can be fed into a fuzzy system to predict the step size, rapidly increasing it during sudden error transients and smoothly decreasing it at steady state, thus reducing step-size jitter [

44]. Multi-channel LMS structures with adaptive gain tuning have also been proposed to enhance stability under multi-axis, multi-frequency disturbances [

45].

These studies indicate that VSS-LMS has clear advantages in handling non-stationary conditions and frequency drift.

- (b)

Normalized LMS (NLMS)

The normalized LMS (NLMS) algorithm improves the stability of the standard LMS method by normalizing the step size with respect to the instantaneous input signal energy. This prevents convergence instability caused by variations in signal amplitude. The weight update equation is given by

where

is the input signal vector,

represents the squared norm (energy) of the input vector at iteration k, and

is a small positive constant introduced to avoid division by zero.

The instantaneous error signal is computed as

where

denotes the desired reference signal and

is the filter output.

Compared with the standard LMS algorithm, the NLMS algorithm exhibits improved stability, especially when the amplitude of the input signal varies dynamically. It has been shown to perform effectively under variable-speed conditions, and normalization schemes based on instantaneous frequency have been proposed to further enhance its adaptability. Such extensions allow the algorithm to automatically adjust its bandwidth according to the operating frequency, thereby improving its dynamic response capability [

46].

- (c)

Filtered-X LMS (FXLMS)

The Filtered-X LMS is an important extension of the LMS algorithm in active noise and vibration control. Its core idea is to explicitly account for the secondary path of the control signal (through the power amplifier, actuator, and rotor dynamics) and filter the reference signal accordingly, ensuring convergence under complex dynamic paths.

In AMB systems, FXLMS is particularly well-suited for suppressing periodic disturbances. For example, an active control scheme combining block-filtered LMS (FBLMS) effectively suppressed imbalance vibration in an electric-spindle–grinding-wheel system, achieving better control performance than a conventional PID controller [

47]. Another study designed an optimal acceleration feedforward compensator combined with FXLMS, significantly reducing the effect of base motion on magnetic bearing performance in experiments [

48]. In a floating-raft isolation system, combining notch filter preprocessing with FXLMS was shown to significantly improve convergence speed and cancel multi-harmonic disturbances [

49]. A variable-step block-filtered LMS algorithm was also proposed, which successfully suppressed harmonic currents in a practical AMB system, demonstrating its engineering feasibility [

50].

- (d)

Other Nonlinear and Intelligent Improvements

Beyond VSS-LMS, NLMS, and FXLMS, researchers have proposed various further improvements. For example, a normalized variable-step LMS algorithm based on the inverse hyperbolic sine function (arsinh-NLMS) adaptively adjusts the step size for different frequency components, maintaining low steady-state error and high convergence speed under multi-harmonic disturbances [

51]. Another approach incorporates an iterative search mechanism into the LMS weight update, effectively improving precision and robustness in complex dynamic cases [

52]. These improvements indicate that combining nonlinear dynamics and intelligent mechanisms offers a promising direction for enhancing LMS adaptability and performance.

2.3. Practical Applications and Advantages of IFMC

Inertia-force minimization techniques have been widely applied in high-speed turbomolecular pumps and AMB-supported compressors. For example, several studies have reported that notch filtering or repetitive control can reduce synchronous vibration components by more than 60–80% during steady-state operation. These methods are particularly advantageous due to their simple implementation and strong suppression of fixed-frequency disturbances, making them suitable for industrial AMB systems where synchronous imbalance is dominant.

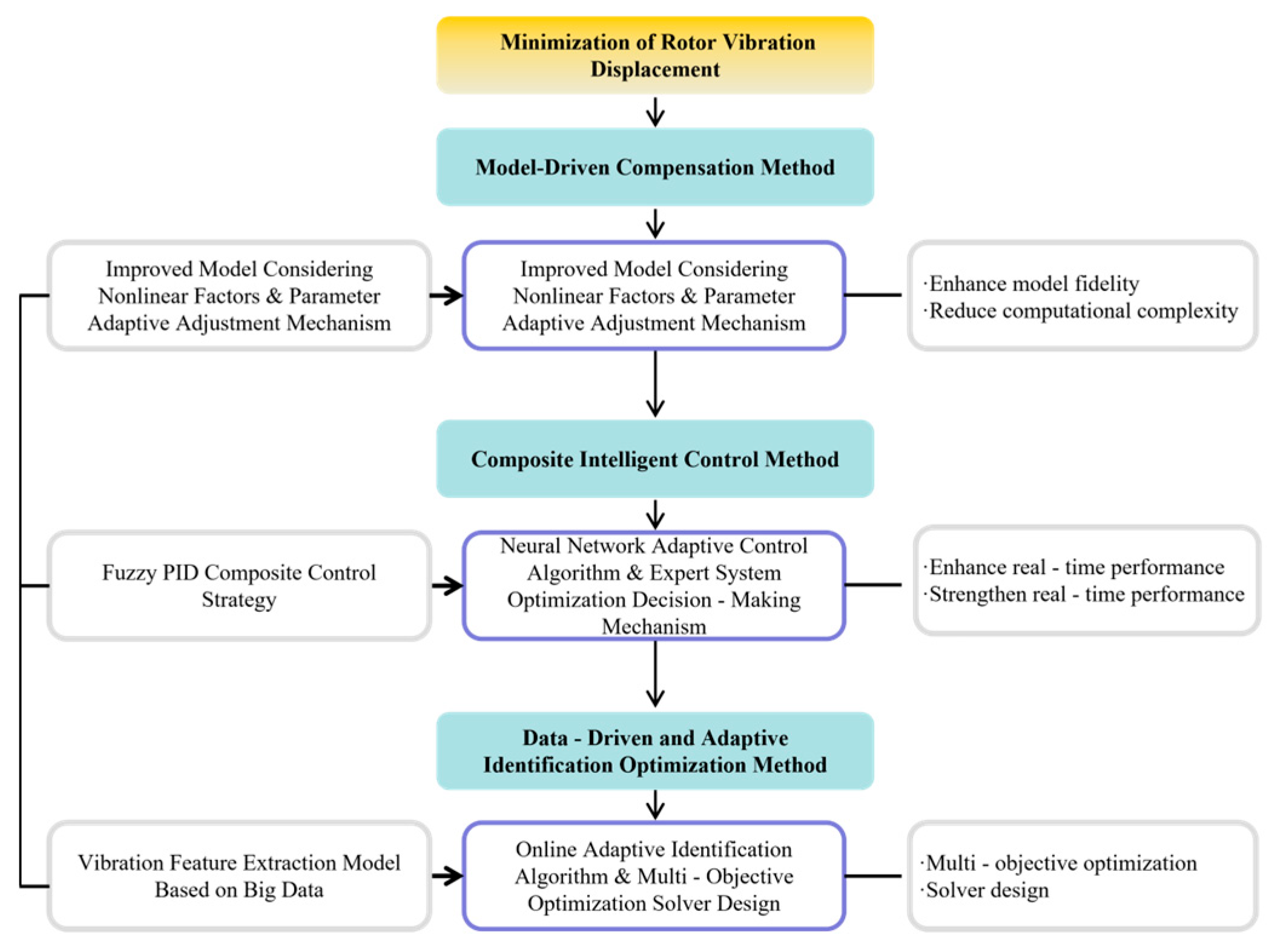

3. Active Imbalance Compensation Strategy for Rotor Vibration Displacement Minimization

Compared to inertia force minimization control (reducing bearing force), rotor displacement minimization control is more challenging due to the difficulty in accurately obtaining the magnitude and phase of the system’s imbalanced force.

Although rotational speed can be measured, the core challenge in achieving displacement minimization control lies in the ability to accurately and dynamically obtain the magnitude and phase of the imbalanced force and actively compensate for it. To address this challenge, recent advancements in AMB systems have primarily led to three main approaches: model-driven methods, control structure optimization, and data-driven identification. The following sections provide a systematic review of these three approaches.As shown in

Figure 4, the active imbalance compensation strategy for rotor displacement minimization can be categorized into model-driven methods, control structure optimization, and data-driven identification approaches.

3.1. Model-Based Compensation Methods

Model-driven approaches rely on physical modeling and theoretical analysis, using the dynamic model of the rotor–bearing system to guide imbalance force compensation control. Such methods include the classical influence coefficient method and its improvements, as well as modal-based parameter identification and compensation. They emphasize achieving minimum displacement control through deterministic model relationships.

In AMB systems, model-driven imbalance compensation has laid the theoretical foundation for the development of various new techniques. Its main advantage lies in its clear physical interpretation and the ease with which it can be optimized by incorporating engineering experience. The following sections introduce model-driven strategies such as the influence coefficient method and its extensions, as well as modal identification and parameter correction approaches.

3.1.1. Influence Coefficient Method (ICM) and Improvements

The Influence Coefficient Method (ICM) is one of the most classic and representative model-driven methods for active imbalance compensation. Based on linear system theory, ICM establishes a linear relationship (influence coefficient matrix) between excitation (trial weights or equivalent electromagnetic forces) and vibration response, calculating the required compensation force, thus achieving dynamic balance control of the rotor without stopping. As early as 1983, Burrows et al. applied the least squares method to identify the influence coefficient matrix and used open-loop feedforward control to successfully suppress rotor imbalance response [

53], introducing the concept of influence coefficient balancing into the AMB active control field, laying the foundation for subsequent research.

In recent years, researchers have made various improvements to ICM to enhance its practicality and accuracy. For instance, Ranjan G. proposed the generalized influence coefficient method (GICM), which iteratively optimizes the influence coefficients by repeatedly adding masses, significantly improving compensation precision at high speeds [

54]. Experimental results showed that in rigid rotor dual-plane compensation, the residual imbalance vibration amplitude was reduced by approximately 55% after dynamic balancing. Zhou J. and colleagues used AMB to directly apply compensation current online, replacing traditional physical weighting, and combined the Least Mean Square (LMS) algorithm to extract vibration amplitude and phase in real-time [

55]. Under 3000 rpm conditions, after only three iterations, the overall vibration amplitude decreased by 68.6–84.5%, the main frequency amplitude dropped by 90–96.4%, and the main harmonic amplitude at some measurement points decreased by up to 28.8 dB, demonstrating highly efficient compensation.

In terms of enhancing engineering practicality, Jiang Feng et al. proposed completing online compensation with only two trial signals [

56]. Their experiments at 3000 rpm and 6000 rpm achieved significant vibration reduction: after compensation, the rotor’s axis trajectory noticeably shrank from an elliptical shape, and the fundamental frequency amplitude of the vibration signal significantly attenuated. Guan et al. [

57] combined the Adaptive Notch Filter (ANF) with ICM, using ANF to extract vibration amplitude and phase in real-time, then using ICM to calculate the compensation force. Under 70 Hz (approximately 4200 rpm) conditions, this method reduced the displacement amplitudes at four measurement points by 56.6%, 62.8%, 49.2%, and 63.7%, respectively, with a significant decrease in the spectral peak, demonstrating good robustness under various operating conditions. Moreover, Bala Murugan et al. proposed an improved ICM (IICM) method combined with simulated trial imbalance (STU) for high/low-pressure co-axial rotors in gas turbines [

58]. They used AMB to provide electromagnetic excitation without mechanical trial masses, enabling simultaneous online identification and compensation of both high-pressure and low-pressure rotors even under measurement noise interference. This approach also provides a viable solution for in-service rotor dynamic balancing in gas turbines.

For ease of comparison, this section lists typical results of ICM-based methods and their improvements (

Table 3). These studies mainly focus on rigid rotors or low-order modes, demonstrating significant imbalance vibration suppression effects in both experimental and simulation environments, fully proving the effectiveness of ICM-based methods in displacement minimization compensation.

3.1.2. Modal Identification and Parameter Correction Methods

With the increasing rotational speed and flexibility of rotor systems, the traditional Influence Coefficient Method (ICM), which relies on a single linear input–output relationship, has gradually shown limitations in dealing with complex modal coupling and multi-source imbalance. To achieve higher precision and more targeted compensation, researchers have proposed modal-based identification and parameter correction methods. These methods aim to optimize imbalance control by delving into the rotor dynamics.

For example, in the separation of multi-source imbalance, Hu Yefa and others adopted holographic spectrum analysis to decouple the initial imbalance into static imbalance and couple imbalance [

59], and combined modal shape information to compensate each type, thus achieving targeted suppression. This method distinguishes the influence of different imbalance sources on various modes, providing an approach for the classification compensation of multi-source imbalance.

Subsequently, Tiwari and colleagues proposed a joint identification algorithm based on rotor dynamics models, which synchronously estimates the system’s dynamic stiffness parameters and imbalance during the experiment, aligning the compensation parameters with the actual dynamic characteristics [

60]. This significantly improves the robustness in complex operating conditions. The method demonstrates that by introducing a more comprehensive physical model, updating system parameters while compensating for imbalance can enhance the effectiveness of compensation.

To address the uncertainty caused by operating environment and system parameter variations with changing conditions, Tong Yu and others developed an Imbalance Identification and Compensation Strategy based on the Model Reference Adaptive System (MRAS) [

61]. This method adjusts model parameters and compensation signals in real time during rotor operation, ensuring that the system maintains high compensation accuracy and adaptability under a wide range of rotational speeds and external disturbances. Simulation and experimental results from Tong Yu et al. showed that their algorithm could reduce the rotor’s synchronous amplitude at both bearing ends by more than 90% within 0.2 s and adapt to speed changes, providing fast and accurate vibration suppression.

In addition, researchers have explored joint identification methods for distributed imbalance and bearing characteristic parameters to address imbalance problems in high-order modes of flexible rotors. Dong Huimin and colleagues used the global eccentricity curve to represent the distributed imbalanced mass along the shaft and conducted experiments within the speed range of 2500–2800 r/min [

62]. Results indicated that after compensation, the bearing amplitude at the first-order rotor mode was reduced by 50–55%, validating the effectiveness of the distributed imbalance compensation method. Meanwhile, Li Chuanjiang and colleagues introduced Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) combined with the least squares method to process vibration signals under non-steady rotational conditions, allowing for more accurate extraction of imbalance response amplitude and phase [

63]. Experimental results showed that compared to the traditional Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) combined with phase-resampling methods, this method significantly reduced phase and amplitude extraction errors under variable speed conditions, providing more reliable data for subsequent modal compensation.

Finally, Zhang Anshi and others further expanded on this idea [

64]. They developed a finite element model of a gear-rotor system to simultaneously identify both the distributed imbalance parameters along the shaft and the bearing dynamic characteristics. Experimental results indicated that this method not only applies to single-rotor systems but also significantly reduces the imbalance response in various modes in dual parallel-axis gear-rotor systems, demonstrating strong engineering practicality.

Table 4 summarizes representative studies on modal identification and parameter correction methods. These approaches fully utilize the dynamic model of the rotor system and modal information, allowing for targeted compensation of different imbalance types (e.g., mass imbalance, couple imbalance), resulting in higher compensation precision and robustness in complex systems.

3.2. Composite Intelligent Control Methods

Composite intelligent control methods enhance the active suppression of imbalanced vibration by optimizing control structures and integrating advanced algorithms, all without relying on precise models. Typical examples include adaptive feedforward compensation, disturbance observers (DOB), and composite control schemes that combine traditional control strategies with intelligent algorithms.

These methods typically use observers, feedforward channels, and similar mechanisms to estimate and cancel imbalanced forces in real time, while introducing intelligent adjustment mechanisms to improve the system’s robustness under complex operating conditions. The following sections describe the applications of feedforward and phase compensation methods, disturbance observers, and their enhanced versions in the context of displacement minimization compensation.

3.2.1. Feedforward and Dynamic Phase Compensation Methods

Feedforward compensation involves real-time estimation of the imbalanced force and the active application of an equal-magnitude, opposite-phase control signal, enabling the compensation of disturbances before they affect the rotor. This method is considered one of the key means to improve the response speed and vibration suppression ability of AMB systems. Compared to pure feedback control, the introduction of a feedforward channel allows preemptive counteraction of periodic imbalanced forces, thus alleviating the burden on the closed-loop system. Recent developments in adaptive feedforward methods have further incorporated online learning and dynamic parameter adjustment mechanisms, enabling the automatic matching of the amplitude and phase of the compensation signal to the imbalanced force characteristics. These methods do not rely on precise models and can adapt to more complex operating conditions and parameter variations.

Fang et al. proposed an adaptive feedforward algorithm based on a gain-phase compensator, which uses a gradient descent rule to adjust the compensator’s gain and phase in real time [

65]. This approach significantly mitigates the gain attenuation and phase lag issues that are present in traditional feedforward systems. Experimental results show that this method can reduce the rotor’s synchronous vibration amplitude by over 80% at different speeds. Moreover, it features a low hardware cost and high adaptability, demonstrating excellent practical value. At the same time, to address the nonlinearity and time-varying characteristics of AMB actuators, An Fengyan et al. incorporated a Radial Basis Function (RBF) neural network into the feedforward compensation structure, using a stochastic gradient method to optimize the neural network parameters in real time, which more efficiently suppressed periodic vibration energy [

66]. This type of intelligent feedforward method effectively enhances adaptive compensation capabilities in complex nonlinear environments, reflecting the latest trend of integrating feedforward control with intelligent algorithms for better imbalance suppression.

Additionally, dynamic phase compensation has also become a widely studied topic in recent years. Besides compensating for the amplitude of the force, it is equally crucial to maintain the precise opposite-phase relationship between the compensation signal and the imbalanced force. If the phase matching is inaccurate, it not only weakens the compensation effect but can also cause “phase dead zones” that lead to compensation failure. Therefore, various online phase correction strategies have been proposed to ensure that the compensation signal remains oppositely synchronized with the imbalanced force across the full speed range.

For example, Xiao Weihui et al. proposed an active sweep frequency correction method: when speed changes, a small sweep frequency excitation is applied to dynamically measure the phase difference between the imbalanced force and the compensation signal, and the compensation phase is adjusted in real time, achieving optimal integrated control of both amplitude and phase across a wide speed range [

67]. Lu Jintao et al. designed a self-learning mapping strategy to train the “phase–frequency–speed” relationship model online, enabling the system to quickly obtain approximately optimal compensation phase at different operating conditions [

68]. Zhao Haoyu et al. incorporated a feedforward adaptive phase correction step into the control loop, using real-time adjustments to maintain the compensation current in opposition phase, even in environments with complex interference, significantly enhancing the compensation robustness at high-speed conditions [

69]. Gong Lei et al. proposed a polarity-switching adaptive notch filter, which dynamically switches the phase polarity of the output signal according to the speed range, ensuring that the compensation signal is always opposite to the imbalanced force across the full speed range, effectively covering compensation dead zones caused by phase changes near the critical speed [

70].

3.2.2. Disturbance Observer (DOB) and Enhanced Methods

The Disturbance Observer (DOB) is a method that combines system models with real-time measurements to estimate external disturbances. When applied to AMB systems, DOB can observe and estimate imbalanced force disturbances in real time and generate an equivalent feedforward compensation signal to be applied to the control input, thereby suppressing vibrations. In essence, DOB provides the control system with a “virtual sensor,” enabling it to sense and counteract synchronous imbalanced forces without the need for additional hardware, significantly improving the system’s vibration suppression performance.

The DOB strategy was first introduced into the magnetic levitation rotor imbalance control field by Chen et al., who applied DOB to actively estimate and compensate for imbalanced forces, verifying its basic feasibility [

71]. Later, Wei Jingbo et al. developed the Terminal Sliding Mode DOB, which introduced sliding mode variable structure into the observer, improving disturbance estimation accuracy and system robustness [

72]. Simulation results showed that this method led to faster rotor levitation response and significantly reduced steady-state vibration amplitude. This achievement demonstrated that combining DOB with nonlinear control techniques (such as sliding mode) further enhances imbalance compensation effects.

In practical engineering applications, the Disturbance Observer (DOB) also demonstrates excellent adaptability and practical value. Wei-Lung Lee et al. applied the DOB in a high-speed flywheel AMB system, achieving sensorless spin-up control and active suppression of synchronous vibration, thereby proving that the DOB can effectively control imbalance vibration even without a rotor speed sensor [

73]. Noshadi et al. further integrated H∞ robust control with the DOB framework, enhancing the system’s robustness against model uncertainties and external disturbances [

74]. Kim et al. combined the Internal Model Control (IMC) strategy with the DOB, successfully attenuating periodic vibration disturbances in a high-speed rotating mirror system and improving overall system stability [

75].

These studies collectively demonstrate that the DOB framework can be effectively integrated with multiple control strategies, significantly improving the imbalance vibration suppression performance of AMB systems under complex operating conditions.

It is important to note that the effectiveness of the DOB method heavily relies on the accuracy of the system model. If there are model deviations, the accuracy of disturbance observation and compensation will be affected. Therefore, in engineering practice, DOB is often combined with adaptive correction or robust control strategies to mitigate performance degradation caused by model inaccuracies. This reflects a key feature of composite intelligent methods: integrating observers, feedforward structures, and adaptive/robust algorithms to complement each other and ensure stable and reliable system operation.

3.3. Data-Driven and Adaptive Identification Optimization Methods

With the increasing demand for higher precision and adaptive performance in AMB systems, data-driven and intelligent optimization methods are becoming an important direction of development for active imbalance compensation. These methods break free from the reliance on precise models, making full use of experimental data and online identification to optimize compensation strategies, including vibration amplitude iterative optimization and model-assisted parameter identification. Their common feature is significantly enhanced system adaptability and compensation accuracy under complex working conditions. The following sections introduce several types of data-driven and adaptive optimization methods.

3.3.1. Amplitude Iterative Optimization Method

The amplitude iterative optimization method aims to minimize rotor vibration by dynamically adjusting the compensation force magnitude through an online iterative algorithm, gradually approaching the optimal value. Its advantage is that it does not rely on precise models, instead utilizing trial excitations and real-time measurement data for adaptive optimization. This makes it insensitive to the system’s parameters and suitable for various types of rotor systems.

Among these, Mao Chuan et al. proposed a real-time variable step size polygonal search algorithm [

76], which uses the phase of the compensation current as a reference and implements efficient imbalance suppression across critical speeds through polygonal iteration. Experimental results show that during the crossing of critical speeds, this method can quickly find the optimal compensation force amplitude, effectively reducing synchronous vibration amplitude. Building upon this, Zhu Changsheng et al. introduced adaptive step-size and direction-update strategies. The algorithm automatically adjusts its iteration step size under different rotational speed conditions, which significantly improves convergence speed and the accuracy of imbalance parameter identification [

77]. This method is especially suitable for rigid and low-order mode rotor systems and can rapidly address the fundamental frequency imbalance issue.

Additionally, some studies have expanded the optimization target from compensation force amplitude to directly identifying imbalance parameters (such as imbalance mass and phase) for more precise compensation. Jiang Kejian et al. proposed a recursive optimization algorithm, which does not require known initial values and can online determine the equivalent imbalance mass and phase of the rotor, thus achieving high robustness compensation under variable speed conditions [

78]. In comparison, Chen Liangliang et al. further improved the convergence efficiency of the parameters through a variable step size and angle search strategy, making the algorithm suitable for frequently performed dynamic balancing [

79].

Overall, the data-driven iterative optimization method has a simple structure and is easy to implement, making it especially suitable for systems that do not involve strong nonlinearity or complex high-order modes. However, when dealing with high-order modes or strongly nonlinear systems, a single iterative algorithm may experience slow convergence or get trapped in local optima. Therefore, it is typically necessary to combine global optimization algorithms or introduce prior knowledge to improve robustness and ensure that the system can fully suppress imbalanced vibrations under complex operating conditions.

3.3.2. Model-Assisted Online Identification of Imbalance Parameters

Unlike purely data-driven methods, model-assisted strategies enhance the accuracy and robustness of imbalance parameter identification by integrating rotor dynamics modeling with real-time measurement data. This approach estimates the system’s dynamic parameters online while simultaneously extracting imbalance quantities, enabling active compensation tailored to the dynamic characteristics of different modes. By combining system modeling with real-time data, this method effectively utilizes physical laws to precisely calibrate imbalance compensation.

For example, Hu Yefa et al. used holographic spectrum analysis to distinguish static imbalance components from couple imbalance sources, applying reverse electromagnetic forces for targeted compensation. This method differentiates between different types of imbalanced forces and rotor vibration modes, enabling mode-specific compensation. Schuhmann T et al. employed Extended Kalman Filtering (EKF) to estimate rotor dynamic parameters (such as rotor stiffness and damping) in real time while simultaneously extracting imbalance information [

80]. This method effectively addresses imbalance suppression tasks under variable speed conditions, offering strong adaptability and robustness.

Lum et al. proposed an adaptive auto-calibration strategy, using bias current to automatically adjust the system’s compensation parameters [

81]. This strategy allows for adaptive compensation even in the presence of unknown imbalance, providing real-time adjustment capability that ensures the AMB system maintains high performance under unstable or unknown operating conditions.

3.4. Practical Applications and Advantages of Active Compensation Methods

Active compensation strategies have been successfully adopted in high-speed rotor test rigs and precision AMB platforms. Experimental results reported in the literature show that adaptive feedforward compensation can effectively track speed-varying imbalance and achieve significant vibration reduction during critical speed passages. The main practical advantage of these strategies lies in their ability to maintain robustness under parameter variations and to adapt in real time to changing imbalance levels.

3.5. Summary of This Section

This section provided a classification and review of the minimum displacement compensation strategies in active magnetic levitation (AMB) rotor systems, focusing on data-driven, model-assisted identification, and dynamic phase compensation methods. Both data-driven iterative optimization methods and model-assisted strategies offer high adaptability and robustness, effectively suppressing imbalance vibrations under complex operating conditions. Dynamic phase compensation, in addition to optimizing compensation force amplitude, further improves the system’s compensation accuracy and robustness under multiple rotational speeds.

Current research has increasingly shifted toward intelligent optimization and composite control structures, such as combining feedforward compensation with intelligent algorithms to enhance the efficiency and applicability of imbalance suppression.

However, many challenges remain: for instance, ensuring full-range minimum displacement compensation for high-order mode rotors and variable-speed conditions, as well as reducing algorithmic complexity and enhancing the feasibility of engineering applications. Future research could focus on integrated compensation for multi-modal systems, the application of novel intelligent algorithms, and the combination of on-site testing and feedback from industry.

4. Applications and Developments of Intelligent Control Methods

Unlike conventional model-based or fixed-parameter controllers, intelligent control strategies emphasize learning capability, adaptability, and structural innovation to cope with repetitive operating conditions, nonlinear dynamics, and parameter uncertainties.

This section first introduces iterative learning control (ILC) as a representative data-driven approach that exploits operational repetitiveness to achieve high-precision imbalance compensation. It then discusses the emerging role of neural network and deep learning techniques, highlighting their advantages and implementation challenges in real-time AMB control.

Furthermore, structural innovations in the frequency domain, particularly the synchronous rotating frame (SRF) method, are reviewed as an efficient means of synchronous disturbance extraction and compensation.

Finally, practical examples are summarized to illustrate the advantages and future potential of intelligent control strategies in next-generation AMB systems.

4.1. Application of Iterative Learning Control (ILC) in Imbalance Compensation

Iterative Learning Control (ILC) has emerged as an effective intelligent strategy for suppressing synchronous vibrations in AMB systems, particularly under repetitive or periodic operating conditions. By exploiting the tracking errors from previous operating cycles, ILC progressively refines the control input so that the imbalance response is asymptotically reduced across iterations. This mechanism is particularly advantageous during repeated start-ups, shutdowns, and critical speed crossings, where vibration patterns exhibit strong periodicity. The typical ILC updating law adjusts the compensation signal at each iteration using error-based feedback, and advanced schemes introduce forgetting factors, adaptive learning rates, or robust filtering to enhance stability against noise and speed variations.

Recent developments include the integration of ILC with extended state observers to improve disturbance estimation and compensation [

82], and the design of composite ILC structures to coordinate imbalance suppression with automatic balancing [

83]. Furthermore, some researchers combined ILC with PID feedback and investigated the role of filtering and forgetting factors, validating the approach’s superior performance across a wide speed range [

84].

Collectively, these studies confirm that ILC leverages operational repetitiveness to achieve high-accuracy imbalance suppression without requiring precise physical models, making it a representative paradigm of intelligent control in AMB applications.

4.2. Exploration of Neural Network and Deep Learning Approaches

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) provide a novel avenue for AMB imbalance control by harnessing their strong nonlinear modeling capacity and self-learning ability to adapt to complex dynamical conditions. The core strength of ANNs lies in their ability to extract salient features from operational data and establish nonlinear mappings that yield optimized compensation signals. While traditional PID and adaptive filtering remain dominant, data-driven approaches are gaining traction for handling high-order nonlinearities. Yao [

85] demonstrated that a Deep Neural Network (DNN) integrated with PID feedback could effectively map complex vibration patterns that linear controllers fail to capture. However, a critical challenge in these implementations is the computational burden imposed by deep networks on real-time controllers. To address this, Zhou et al. [

86] utilized a lighter-weight Radial Basis Function (RBF) network optimized via Genetic Algorithms. Current research trends suggest that future breakthroughs will likely rely on Edge Computing or FPGA-accelerated neural networks to reconcile the trade-off between inference accuracy and control loop bandwidth.

4.3. Structural Innovation in the Frequency Domain: Synchronous Rotating Frame (SRF)

The Synchronous Rotating Frame (SRF) transformation represents a significant structural innovation in the frequency domain for synchronous vibration suppression in AMB systems, characterized by its simplicity, high computational efficiency, and clear physical interpretation. Its fundamental principle is to employ orthogonal transformation to convert periodic synchronous components in the stationary stator frame into direct current (DC) signals in the rotating frame, thereby greatly simplifying synchronous disturbance extraction and targeted compensation.

Mu et al. first demonstrated the feasibility of SRF for isolating synchronous components in imbalance suppression [

87]. Building upon this foundation, Chen et al. introduced lead–lag compensation to address phase lag in high-speed flywheel systems [

88], while Peng et al. extended the SRF framework to the accurate extraction and suppression of synchronous torque, enhancing both compensation precision and system robustness [

89].

These advancements illustrate that SRF, by providing efficient synchronous signal decoupling, has become a key component of high-efficiency, highly integrated AMB compensation strategies, particularly suitable for variable-speed and high-speed conditions.

4.4. Practical Applications and Advantages of Intelligent Control Strategies

Advanced control strategies such as model predictive control and machine-learning-assisted identification have begun to see applications in next-generation AMB systems. These methods enable more accurate disturbance estimation and stronger robustness to multi-source uncertainties. Their practical value is particularly evident in hybrid support structures, where complex coupling effects require high adaptability and multi-variable optimization.

5. Conclusions

This paper has systematically reviewed the theoretical foundations, technical pathways, and engineering progress of two major imbalance suppression strategies in AMB systems: inertia force minimization and displacement minimization. Driven by the growing demand for high-speed and high-precision equipment, a wide range of methodologies—including model-driven approaches, data-driven schemes, structural optimization, and intelligent algorithms—have undergone rapid development.

These methods have demonstrated remarkable achievements in synchronous disturbance rejection, adaptability across full operating ranges, and efficient online compensation. However, challenges remain in achieving higher compensation accuracy, robustness, and real-time responsiveness when dealing with complex rotor dynamics, nonlinear operating conditions, and multi-bearing coupling. Consequently, the integration of multi-objective cooperative compensation with intelligent optimization has become a critical direction for advancing high-performance AMB operation.

Looking ahead, significant breakthroughs in imbalance suppression for AMB systems are expected in several key directions. First, developing more robust adaptive compensation strategies will be essential to dynamically optimize control parameters under rapidly varying operating conditions, particularly during critical speed crossings. Second, to mitigate the influence of complex background noise and external disturbances, future research should focus on high-precision signal extraction and multi-source information fusion, thereby improving the reliability and accuracy of imbalance identification. Third, as multi-support configurations—such as magnetic–gas hybrid systems or magnetic–mechanical combined bearings—become increasingly common, dynamic modeling and control strategies must be expanded to address strongly coupled multi-physics behaviors. Achieving this will require a deeper integration of theoretical developments with real engineering practices.

In addition, the imbalance control techniques reviewed in this work demonstrate substantial practical value in high-speed rotor applications. Adaptive and feedforward methods offer clear advantages in managing varying imbalance levels, while notch filtering and repetitive control provide highly effective suppression of synchronous disturbances in industrial AMB systems. These practical insights further reinforce the engineering relevance and applicability of the synthesized techniques.

Author Contributions

X.S. (Xinyan Song): Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing—Original draft preparation, Visualization; H.W.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition; Z.W.: Investigation, Data curation, Writing—Original draft preparation; Y.Z.: Investigation, Resources; X.S. (Xingwei Sa): Investigation, Resources; Z.Z.: Resources, Writing—Review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Research Start-up Fund of North China University of Technology (NCUT) (Fund number: 11005136025XN076-018).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by North China University of Technology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial or non-financial interests, competing interests, or affiliations with any organization that could influence the content of this manuscript.

References

- Han, B.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, S.; Li, M.; Xie, J. Whirl mode suppression for amb-rotor systems in control moment gyros considering significant gyroscopic effects. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 4249–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Y.; Lin, C. Current application and prospect of magnetic bearings in vibration control of marine propulsion shafting. Ship Mech. 2022, 26, 448–458. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Han, B.; Guo, L. Composite hierarchical ant disturbance control for magnetic bearing system subject to multiple external disturbances. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 61, 7004–7012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Huang, S.; Cao, G.; Hu, Z.; Fan, X. A review of vibration suppression methods for magnetic levitation systems. Micromotors 2023, 56, 60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Siva Srinivas, R.; Tiwari, R.; Kannababu, C. Application of active magnetic bearings in flexible rotordynamic systems–a state-of-the-art review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 106, 537–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, X. Research progress on unbalance control technology of magnetic bearings. China Mech. Eng. 2010, 7, 3222. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Tu, X.; Zhou, J.; Yang, K.; Xiao, W.U. A review of unbalance vibration control for magnetically levitated rotors. Bearing 2022, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Cai, Y.; Han, W.; Yin, Z.; Yu, C. Review on active vibration control method of magnetically suspended system. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 108117–108125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, G.A. Physical theory of the electric wave-filter. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1922, 1, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobel, O.J. Theory and design of uniform and composite electric wave-filters. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 1923, 2, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, G.; Maslen, E.H. (Eds.) Magnetic Bearings: Theory, Design, and Application to Rotating Machinery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zheng, S.; Han, B.; Fang, J. Effects of notch filters on imbalance rejection with heteropolar and homopolar magnetic bearings in a 30-kw 60,000-r/min motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 8033–8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beex, A. Moving-average notch filter. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1981, 69, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutknecht, M.; Smith, J.; Trefethen, L. The carathéodory-fejér method for recursive digital filter design. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1983, 31, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, R.; Buhler, P.; Gahler, C.; Larsonneur, R. Unbalance compensation using generalized notch filters in the multivariable feedback of magnetic bearings. IEEE Trans. Control Sys. Tech 1996, 4, 580–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Luo, M.; Yu, L. Unbalance compensation method for electromagnetic bearings based on adaptive notch filter. J. Vib. Eng. 2000, 13, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borio, D. Fast and flexible tracking and mitigating a jamming signal with an adaptive notch filter. Inside GNSS 2014, 9, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Z.; Mohamadian, H. Application of modern control theory on performance analysis of generalized notch filters. In Proceedings of the 2016 5th International Conference on Modern Circuits and Systems Technologies (MOCAST), Thessaloniki, Greece, 12–14 May 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nevaranta, N.; Jaatinen, P.; Vuojolainen, J.; Sillanpää, T.; Pyhrönen, O. Adaptive mimo pole placement control for commissioning of a rotor system with active magnetic bearings. Mechatronics 2020, 65, 102313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tu, Y.; Xiao, W.; Wan, P.; Yang, H. Fast frequency estimation method with unbiased term design based on fir adaptive notch filter. In Proceedings of the 2020 7th International Conference on Information Science and Control Engineering (ICISCE), Changsha, China, 18–20 December 2020; pp. 607–611. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, P.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Du, L.; Wu, Y. Synchronous vibration force suppression of magnetically suspended cmg based on modified double sogi-fill. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 70, 11566–11575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J. Active Vibration Control Method and Experimental Research for Magnetic Levitation High-Speed Motors. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Nanjing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, C.; Xu, X.; Liu, Q. Modeling of magnetic bearings with rotor unbalance and synchronous current suppression. J. Vib. Meas. Diagn. 2015, 34, 1057–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Liu, G.; Zhao, G. Automatic balancing control of active-passive magnetic suspended high-speed rotor systems. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2015, 23, 714–722. [Google Scholar]

- Knospe, C.; Humphris, R. Control of unbalance response with magnetic bearings. In Proceedings of the 1992 American Control Conference, Chicago, IL, USA, 24–26 June 1992; pp. 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Peng, L.; Yu, Y. Simulation analysis of unbalance control for magnetic bearings based on phase-shift notch filter. Househ. Electr. Appl. 2024, 39, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y. Self-balancing control of magnetic suspension rotor systems based on complex phase-shift notch filter. Opt. Precis. Eng. 2016, 24, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, P.; Zhao, G.; Fang, J.; Li, H. Full-frequency adaptive control of unbalance vibration for magnetic bearings based on phase-shift notch filter. Vib. Shock 2015, 34, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Li, H.; Peng, C.; Wang, Y. Experimental investigations of resonance vibration control for noncollocated amb flexible rotor systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 64, 2226–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R. Active Vibration Control Methods and Experimental Research for Magnetic Bearing Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Henan University of Technology, Zhengzhou, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C.; Zhu, M.; Wang, K.; Ren, Y.; Deng, Z. A two-stage synchronous vibration control for magnetically suspended rotor system in the full speed range. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 67, 480–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Chen, Q.; Ren, H. Active balancing control of amb-rotor systems using a phase-shift notch filter connected in parallel mode. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 3777–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tang, J.; Zhou, J.; Han, X.; Wang, K. Vibration suppression of multi-stage-blade amb-rotor using parallel adaptive and cascaded multi-frequency notch filters. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Gao, Z.; Wang, Y. Design method of notch filter for suppressing unbalance vibration in electromagnetic bearings. J. Mech. Eng. 2006, 42, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Research on Unbalance Vibration Control Methods for Electrostatic Bearing Rotors. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Yin, Z.; Ren, Y.; Wang, W.; Fu, B.; Yu, C.; Han, W.; Han, W. A novel attitude angular velocity measurement method based on mass unbalance vibration suppression of magnetic bearing. IEEE Sens. J. 2022, 22, 7717–7726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Hua, Z. Rotor unbalanced vibration control of active magnetic bearing high-speed motor via adaptive fuzzy controller based on switching notch filter. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widrow, B.; Hoff, M. Adaptive Switching Circuits; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Zmood, R.; Qin, L. The direct method for adaptive feed-forward vibration control of magnetic bearing systems. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Control, Automation, Robotics and Vision, ICARCV, Singapore, 2–5 December 2002; Volume 2, pp. 675–680. [Google Scholar]

- Vahedforough, E.; Shafai, B.; Beale, S. Estimation and rejection of unknown sinusoidal disturbances using a generalized adaptive forced balancing method. In Proceedings of the 2007 American Control Conference, New York, NY, USA, 11–13 July 2007; pp. 3529–3534. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Hu, W. Vibration control of active magnetic bearing system based on lqg and lms. J. Mech. Electr. Eng. 2022, 39, 210–216. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Teng, W.; Liu, Y. Vibration control of flywheel energy storage active magnetic bearing–rotor system based on improved variable step-size lms algorithm. Bearing 2024, 7, 99–105. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, G.; Zheng, S. Automatic balancing method for magnetically suspended motor based on adaptive variable step-size lms algorithm. J. Mech. Eng. 2015, 51, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Tang, M. A feed-forward control strategy for compensating rotor vibration of six-pole radial hybrid magnetic bearing with fuzzy adaptive filter. Prog. Electromagn. Res. C 2021, 109, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, W.; Huang, Y.; Lu, H.; Shi, H. Unbalanced displacement lms extraction algorithm and vibration control of a bearingless induction motor. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2018, 56, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yu, M.; Song, C.; Wang, N. Unbalance vibration suppression of maglev high-speed motor based on the least-mean-square algorithm. Actuators 2022, 11, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Zhu, C. An active multiple frequency vibration control scheme of grinding wheel in permanent magnet(pm) electric spindle rotor system. China Mech. Eng. 2014, 25, 162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, W.H.; Kang, M.S. Acceleration feedforward control in active magnetic bearing system subject to base motion by filtered-x lms algorithm. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2006, 14, 134–140. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Song, C.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Q. Research on active isolation feedforward control for magnetic suspension floating raft based on notch filter. China Mech. Eng. 2013, 24, 2341–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.X.; Chen, C.; Tian, J.M.; Zhao, Z.L.; Zhao, H.Q. Design and construction of the first prototype of liquid scintillator detector for fast beam loss monitor(fblm) system. Nucl. Electron. Detect. Technol. 2011, 31, 344–347. [Google Scholar]

- Han, W.; Cai, Y.; Han, W.; Ren, Y.; Wang, W.; Yu, C.; Yin, Z. Harmonic vibration suppression of mscsg based on normalized variable step-size lms algorithm. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 5433–5442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.H.; Shi, D.; Qi, Y.S.; Gao, J.H.; Shen, J.X. Vibration suppression for active magnetic bearings using adaptive filter with iterative search algorithm. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2024, 8, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, C.; Sahinkaya, M.; Clements, S. Active vibration control of flexible rotors: An experimental and theoretical study. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1989, 422, 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, G.; Tiwari, R.; Nemade, H.B. Experimental identification of residual unbalances for two-plane balancing in a rigid rotor system integrated with amb. In Machines, Mechanism and Robotics: Proceedings of iNaCoMM 2019; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 697–709. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Yang, K.; Hu, Y.; Guo, X.; Song, C. Online unbalance compensation of a maglev rotor with two active magnetic bearings based on the LMS algorithm and the influence coefficient method. J. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 166, 108460. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, F.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; Wang, K. Unbalance compensation control of magnetically suspended rotor based on influence coefficient method. Digit. Manuf. Sci. 2020, 8, 12988–12998. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, X.; Peng, H.; Li, H.; Zhang, J. Dynamic balance correction of active magnetic rotor based on adaptive notch filter and influence coefficient method. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, S.B.; Behera, R. Co-axial rotor aero-engine system: A hybrid modeling and dynamic in situ residual balancing between high and small frequencies along simulated trial unbalances with active magnetic bearing integration. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2023, 147, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Gao, X.; Wu, H. Study on unbalance compensation of magnetically suspended rotor. Mach. Manuf. 2006, 44, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, R.; Chougle, A. Identification of bearing dynamic parameters and unbalance states in a flexible rotor system fully levitated on active magnetic bearings. Mechatronics 2014, 24, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Tian, Z.; Sun, Y.; Cao, J. Unbalance identification and vibration suppression of rotor supported by electromagnetic bearings based on model reference adaptive system. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2022, 56, 56–64. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, A.; Shu, H.; Zhang, C. Simultaneous identification method of distributed rotor unbalance and bearing characteristic parameters. J. Harbin Inst. Technol. 2022, 54, 8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Fei, M.; Zhang, Z. A method for extracting unbalance signal under non-stationary rotational speed. J. Vib. Meas. Diagn. 2016, 36, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, A. Modal Balancing Method for Single and Dual Rotor Systems Based on Parameter Identification. Ph.D. Thesis, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, J.; Xu, X.; Tang, J.; Liu, H. Adaptive complete suppression of imbalance vibration in amb systems using gain phase modifier. J. Sound Vib. 2013, 332, 6203–6215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, F.; Sun, H.; Xiao, C.; Xu, J.; Li, X. Research on adaptive active vibration control based on magnetic suspension actuator. Acta Acust. 2010, 35, 161–168. [Google Scholar]