Unique Alcoholic Beverages Derived from Pear and Apple Juice Using Probiotic Yeast

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fruit Juices

2.2. Yeasts and Inoculum Preparation

2.3. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.4. Determination of pH and Total Extract

2.5. Juice Fermentation

2.6. Sample Designation

2.7. Sensory Evaluation

2.8. Chromatographic Analysis of Sugars, Organic Acids, and Alcohols

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Apple and Pear Juice Parameters

3.2. Composition of Fermented Apple and Pear Juices

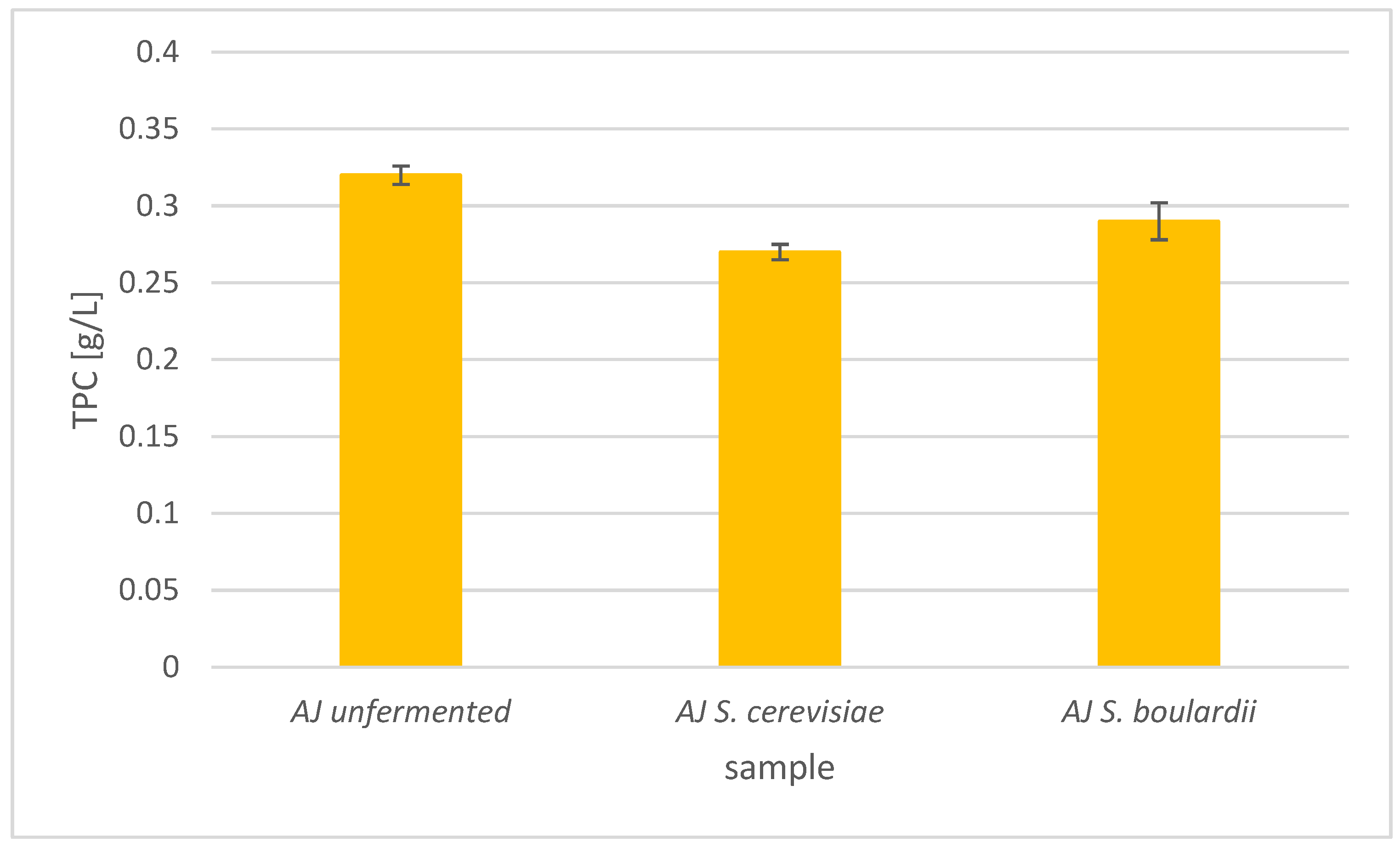

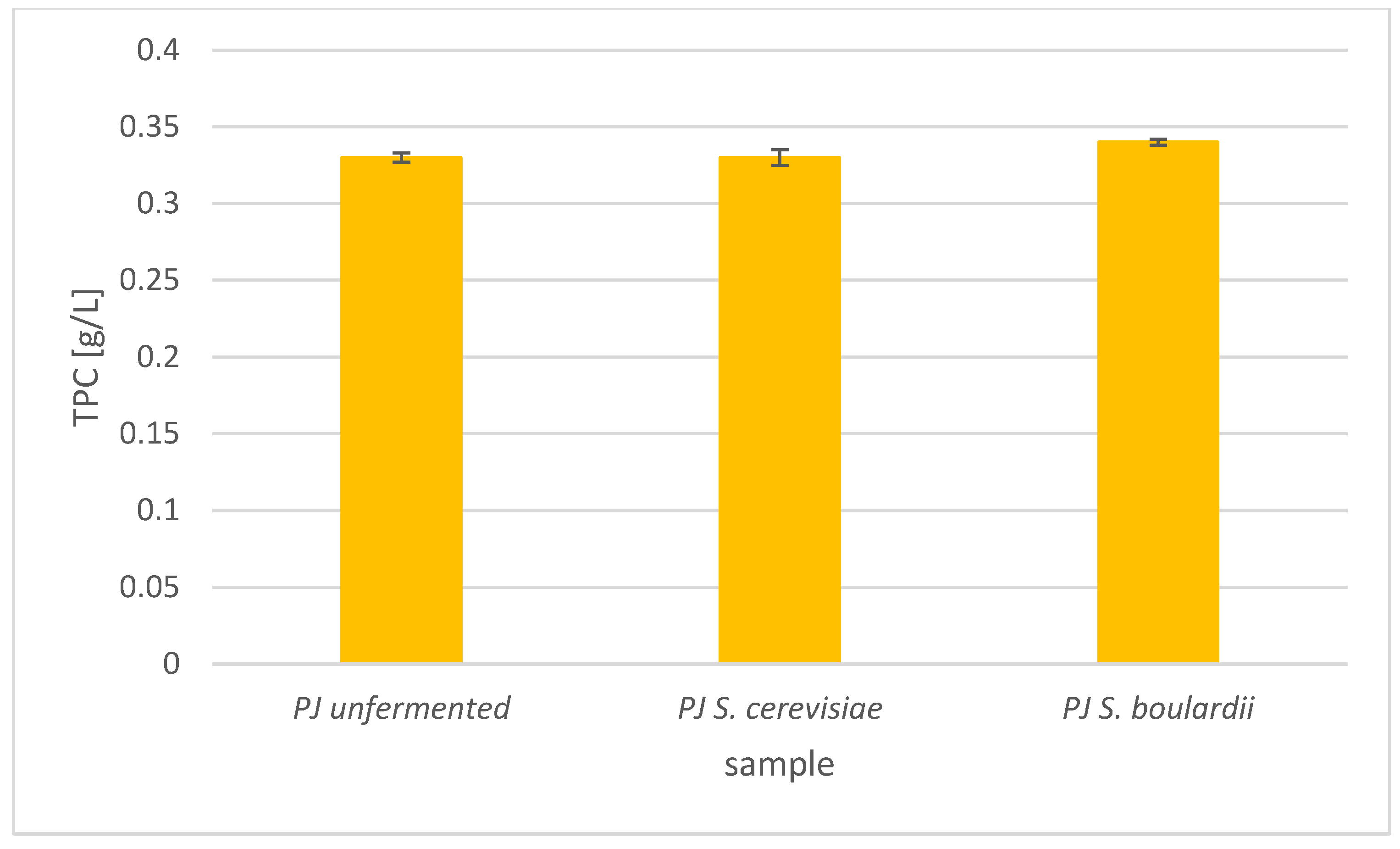

Total Phenolic Content in Apple and Pear Juices

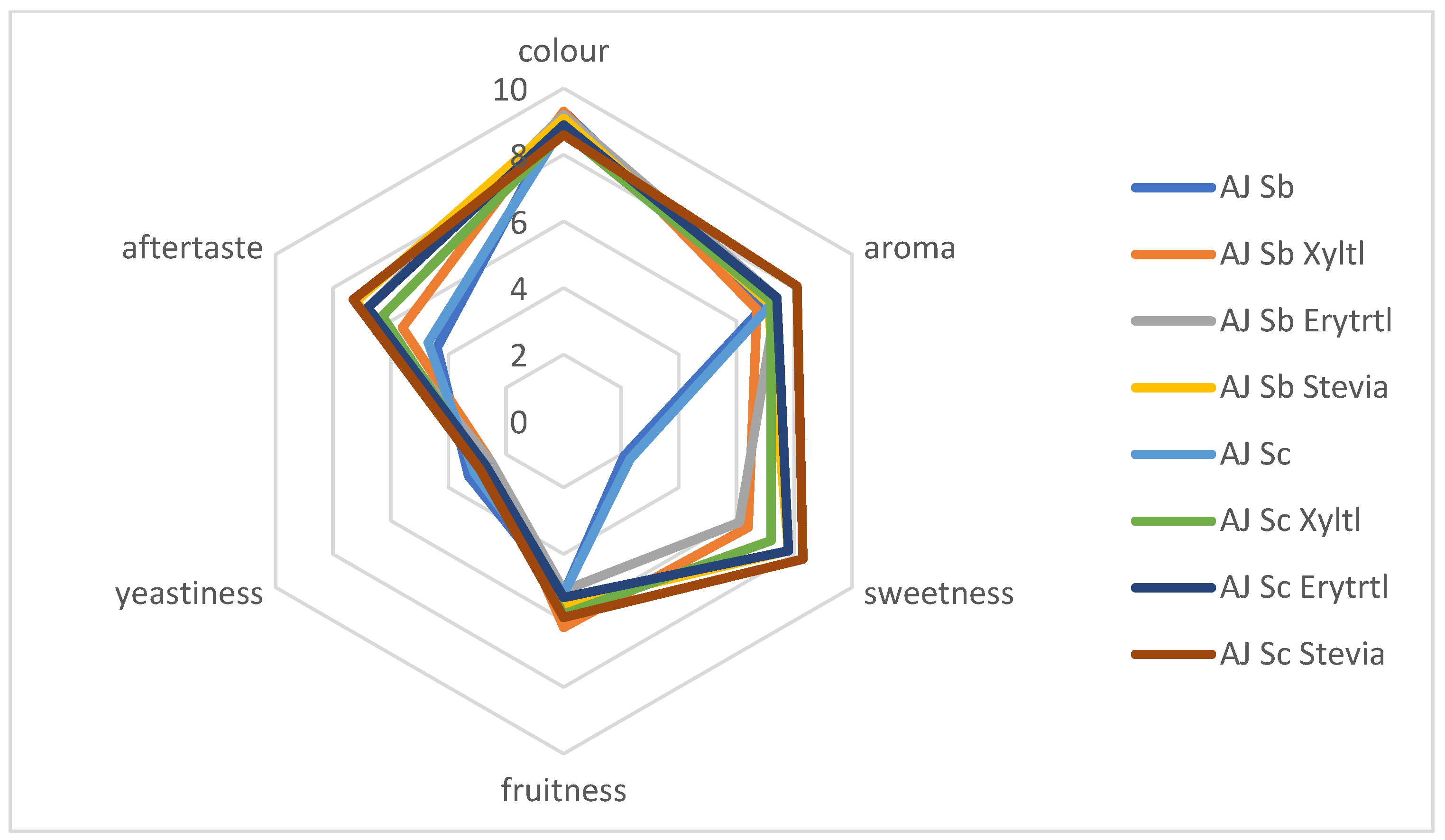

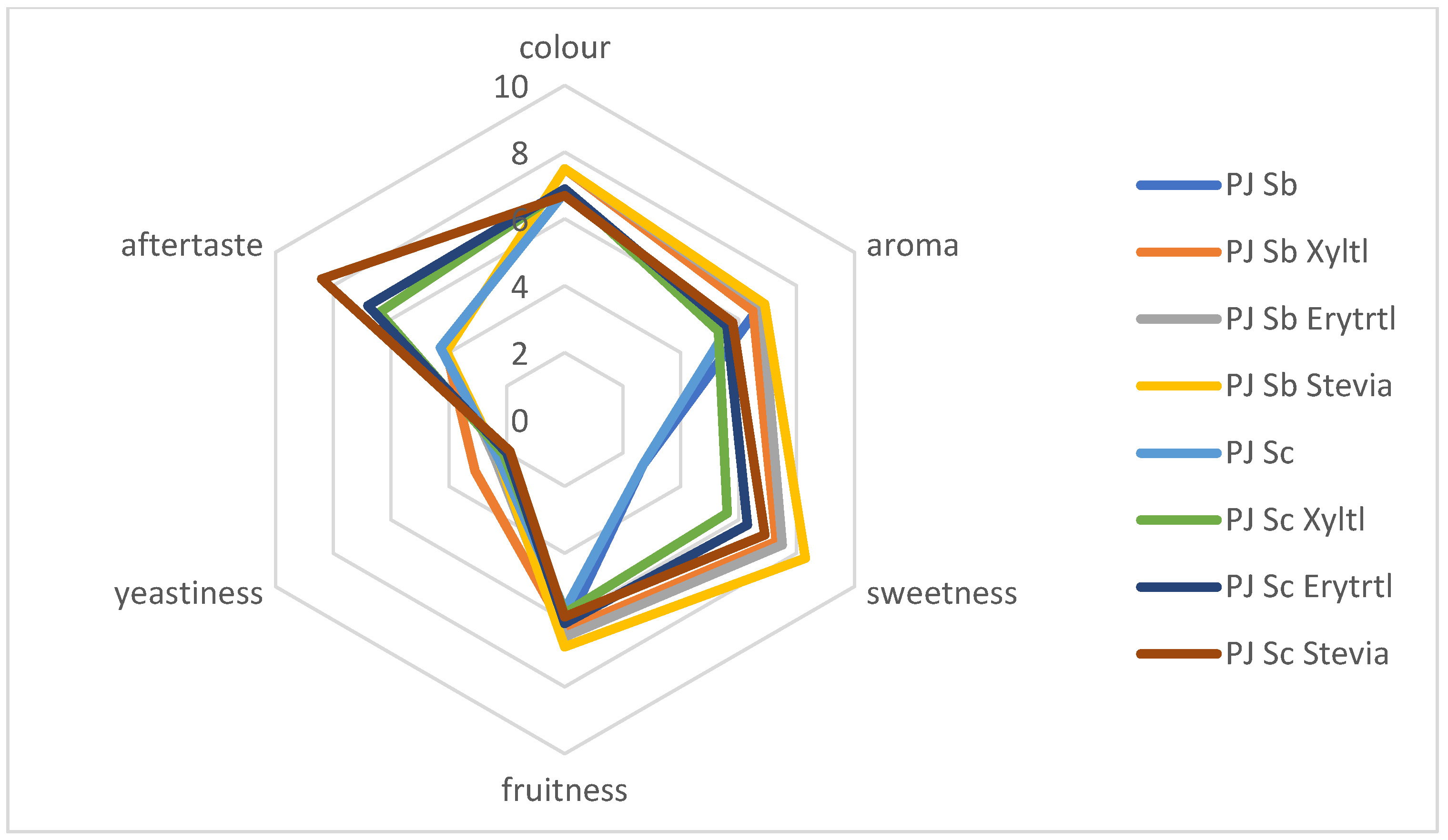

3.3. Sensory Properties of Fermented Apple and Pear Juices

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ashaolu, T.J.; Varga, L.; Greff, B. Nutritional and Functional Aspects of European Cereal-Based Fermented Foods and Beverages. Food Res. Int. 2025, 209, 116221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shazad, A.; Tlais, A.Z.A.; Gottardi, D.; Filannino, P.; Patrignani, F.; Lanciotti, R.; Gobbetti, M.; Di Cagno, R. Enhancing Bioactive Profiles of Elderberry Juice through Yeast Fermentation: A Pathway to Low-Sugar Functional Beverages. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 10, 101100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grembecka, M. Sugar Alcohols—Their Role in the Modern World of Sweeteners: A Review. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 241, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierczak, K.; Garus-Pakowska, A. An Overview of Apple Varieties and the Importance of Apple Consumption in the Prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases—A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobek, L.; Matić, P. Phenolic Compounds from Apples: From Natural Fruits to the Beneficial Effects in the Digestive System. Molecules 2024, 29, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricultural Production—Orchards. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agricultural_production_-_orchards (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- WAPA—The World Apple and Pear Association. Available online: https://www.wapa-association.org/asp/article_2.asp?doc_id=667 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Rutkowski, K.; Brzozowski, P.; Zmarlicki, K.; Warabieda, W.; Sekrecka Małgorzata Mieszczakowska, M.; Miszczak, A.; Buler, Z.; Kruczyńska, D.; Filipczak, J.; Głos, H. (Eds.) Opracowanie Podstaw Teoretycznych Założenia i Prowadzenia Modelowego Sadu, Dostarczającego Surowca Do Produkcji Soków; Instytut Ogrodnictwa—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Skierniewice, Poland, 2023; ISBN 978-83-67039-26-0. [Google Scholar]

- Juice Market Trends in Europe. Consumers Are Focusing on Immune. Available online: https://www.innovamarketinsights.com/trends/juice-market-trends-in-europe/ (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Francini, A.; Fidalgo-Illesca, C.; Raffaelli, A.; Sebastiani, L. Phenolics and Mineral Elements Composition in Underutilized Apple Varieties. Horticulturae 2021, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asma, U.; Morozova, K.; Ferrentino, G.; Scampicchio, M. Apples and Apple By-Products: Antioxidant Properties and Food Applications. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akagić, A.; Oras, A.; Gaši, F.; Meland, M.; Drkenda, P.; Memić, S.; Spaho, N.; Žuljević, S.O.; Jerković, I.; Musić, O.; et al. A Comparative Study of Ten Pear (Pyrus communis L.) Cultivars in Relation to the Content of Sugars, Organic Acids, and Polyphenol Compounds. Foods 2022, 11, 3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Tkacz, K.; Turkiewicz, I.P.; Santos, I.; Camoesas E Silva, M.; Lima, A.; Sousa, I. Exploring the Bioactive Properties and Therapeutic Benefits of Pear Pomace. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, P.; Almeida, V.; Yılmaz, M.; Teixeira, M.C. Saccharomyces boulardii: What Makes It Tick as Successful Probiotic? J. Fungi 2020, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, R.; Waseem, H.; Ali, J.; Ghazanfar, S.; Muhammad Ali, G.; Elasbali, A.M.; Alharethi, S.H. Probiotic Yeast Saccharomyces: Back to Nature to Improve Human Health. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierczak-Siedlecka, K.; Ruszkowski, J.; Fic, M.; Folwarski, M.; Makarewicz, W. Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM I-745: A Non-Bacterial Microorganism Used as Probiotic Agent in Supporting Treatment of Selected Diseases. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 1987–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards-Ingram, L.; Gitsham, P.; Burton, N.; Warhurst, G.; Clarke, I.; Hoyle, D.; Oliver, S.G.; Stateva, L. Genotypic and Physiological Characterization of Saccharomyces boulardii, the Probiotic Strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 2458–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czerucka, D.; Rampal, P. Experimental Effects of Saccharomyces boulardii on Diarrheal Pathogens. Microbes Infect. 2002, 4, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Manan, M. Progress in Probiotic Science: Prospects of Functional Probiotic-Based Foods and Beverages. Int. J. Food Sci. 2025, 2025, 5567567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wine Yeast RV002. Available online: https://en.angelyeast.com/products/distilled-spirits-and-biofuels/wine/wine-yeast-rv002.html (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Vo, H.T.; Nguyen, K.T.N.; Luu, C.M.; Bui, L.H.D.; Nguyen, T.N.; Doan, T.T.K.; Huynh, P.X. Optimization of Fruit Wine Production from Pineapple (Ananas comosus (L.) Merr.) Using Saccharomyces cerevisiae RV002. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment. 2025, 24, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazi, T.A.; Stanhope, K.L. Erythritol: An In-Depth Discussion of Its Potential to Be a Beneficial Dietary Component. Nutrients 2023, 15, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, V.; Macho, M.; Ewe, D.; Singh, M.; Saha, S.; Saurav, K. Biological and Pharmacological Potential of Xylitol: A Molecular Insight of Unique Metabolism. Foods 2020, 9, 1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re-evaluation of Erythritol (E 968) as a Food Additive | EFSA. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/efsajournal/pub/8430 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Anderson, J.C.; Carlson, T.L.; Fosmer, A.M. Cargill Inc. Fermentation methods for producing steviol glycosides. Patent WO2017024313A1, 9 February 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Food Safety Authority Panel on Food Additives and Nutrient Sources added to Food (ANS) Scientific Opinion on the Safety of Steviol Glycosides for the Proposed Uses as a Food Additive. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. J. 2010, 8, 1537. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.P.; Vilariño, J.M.L. Hop Bitterness in Beer Evaluated by Computational Analysis. J. Inst. Brew. 2023, 129, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gen Z Replace Alcohol and Coffee with Mushroom Shots and Kombucha. Available online: https://www.thetimes.com/uk/healthcare/article/gen-z-replace-alcohol-and-coffee-with-mushroom-shots-and-kombucha-dnbkktzj0 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Salminen, S.; Collado, M.C.; Endo, A.; Hill, C.; Lebeer, S.; Quigley, E.M.M.; Sanders, M.E.; Shamir, R.; Swann, J.R.; Szajewska, H.; et al. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on the Definition and Scope of Postbiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 649–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Torre, C.; Pino, R.; Fazio, A.; Plastina, P.; Loizzo, M.R. Synergistic Bioactive Potential of Combined Fermented Kombucha and Water Kefir. Beverages 2025, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; You, Y.; Huang, W.; Zhan, J. The High-Value and Sustainable Utilization of Grape Pomace: A Review. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awulachew, M.T. Probiotics and Thermal Processing: A Review of Challenges and Protective Strategies. Lett. Food Res. 2025, 1, e25057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, S.; Herzig, C.; Birringer, M. A Balancing Act—20 Years of Nutrition and Health Claims Regulation in Europe: A Historical Perspective and Reflection. Foods 2025, 14, 1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, F.; Lourenço, S.; Fidalgo, L.; Santos, S.; Silvestre, A.; Jerónimo, E.; Saraiva, J. Long-Term Effect on Bioactive Components and Antioxidant Activity of Thermal and High-Pressure Pasteurization of Orange Juice. Molecules 2018, 23, 2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patelski, A.M.; Dziekońska-Kubczak, U.; Ditrych, M. The Fermentation of Orange and Black Currant Juices by the Probiotic Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Var. Boulardii. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, V.W.K.; Wee, M.S.M.; Tomic, O.; Forde, C.G. Temporal Sweetness and Side Tastes Profiles of 16 Sweeteners Using Temporal Check-All-That-Apply (TCATA). Food Res. Int. 2019, 121, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwak, M.-J.; Chung, S.-J.; Kim, Y.J.; Lim, C.S. Relative Sweetness and Sensory Characteristics of Bulk and Intense Sweeteners. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2012, 21, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, M.; Tan, V.; Forde, C. A Comparison of Psychophysical Dose-Response Behaviour across 16 Sweeteners. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, F.; Ekşi, A. Sugar Composition of Apple Juices. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2002, 215, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Laaksonen, O.; Tian, Y.; Haikonen, T.; Yang, B. Chemical Composition of Juices Made from Cultivars and Breeding Selections of European Pear (Pyrus communis L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 5137–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, H.; Kruger-Steden, E.; Pats, C.D.; Will, F.; Rheinberger, A.; Hopf, I. Increase of Sorbitol in Pear and Apple Juice by Water Stress, a Consequence of Climatic Change? Fruit Process 2007, 6, 348–355. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Jiao, Z. Profiles of Sugar and Organic Acid of Fruit Juices: A Comparative Study and Implication for Authentication. J. Food Qual. 2020, 2020, 7236534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgus, E.; Hittinger, M.; Schrenk, D. Estimates of Ethanol Exposure in Children from Food Not Labeled as Alcohol-Containing. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2016, 40, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, A.; Iftikhar, S.; Tripathi, J.; Paroha, S. Production of Vinegar from Pear Juice and Comparative Analysis of Its Quality with Apple Juice Vinegar. Adv. Res. 2024, 25, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Way, M.L.; Jones, J.E.; Longo, R.; Dambergs, R.G.; Swarts, N.D. A Preliminary Study of Yeast Strain Influence on Chemical and Sensory Characteristics of Apple Cider. Fermentation 2022, 8, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhvir, S.; Kocher, G.S. Development of Apple Wine from Golden Delicious Cultivar Using a Local Yeast Isolate. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 56, 2959–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, S.; Galli, V.; Barbato, D.; Facchini, G.; Mangani, S.; Pierguidi, L.; Granchi, L. Effects of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Starmerella bacillaris on the Physicochemical and Sensory Characteristics of Sparkling Pear Cider (Perry). Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2023, 249, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aalst, A.C.A.; Mans, R.; Pronk, J.T. An Engineered Non-Oxidative Glycolytic Bypass Based on Calvin-Cycle Enzymes Enables Anaerobic Co-Fermentation of Glucose and Sorbitol by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2022, 15, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthels, N.J.; Cordero Otero, R.R.; Bauer, F.F.; Thevelein, J.M.; Pretorius, I.S. Discrepancy in Glucose and Fructose Utilisation during Fermentation by Saccharomyces cerevisiae Wine Yeast Strains. Fed. Eur. Microbiol. Soc. Yeast Res. 2004, 4, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, K.J.A.; Pardijs, I.H.; van Klaveren, H.M.; Wahl, S.A. A Dive into Yeast’s Sugar Diet—Comparing the Metabolic Response of Glucose, Fructose, Sucrose, and Maltose Under Dynamic Feast/Famine Conditions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2025, 122, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira de Paula, B.; de Souza Lago, H.; Firmino, L.; Fernandes Lemos Júnior, W.J.; Ferreira Dutra Corrêa, M.; Fioravante Guerra, A.; Signori Pereira, K.; Zarur Coelho, M.A. Technological Features of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Var. boulardii for Potential Probiotic Wheat Beer Development. LWT 2021, 135, 110233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fietto, J.L.R.; Araújo, R.S.; Valadão, F.N.; Fietto, L.G.; Brandão, R.L.; Neves, M.J.; Gomes, F.C.O.; Nicoli, J.R.; Castro, I.M. Molecular and Physiological Comparisons between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces boulardii. Can. J. Microbiol. 2004, 50, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vion, C.; Yeramian, N.; Hranilovic, A.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I.; Marullo, P. Influence of Yeasts on Wine Acidity: New Insights into Saccharomyces cerevisiae. OENO One 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.M.; Cordeiro, C.A.; Ponces Freire, A.M. In Situ Analysis of Methylglyoxal Metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Fed. Eur. Biochem. Soc. Lett. 2001, 499, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.M.; Mendes, P.; Cordeiro, C.; Freire, A.P. In Situ Kinetic Analysis of Glyoxalase I and Glyoxalase II in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur. J. Biochem. 2001, 268, 3930–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, B.J.; Navid, A.; Kulp, K.S.; Knaack, J.L.S.; Bench, G. D-Lactate Production as a Function of Glucose Metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast Chichester Engl. 2013, 30, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Пескoва, И.В.; Острoухoва, Е.В.; Луткoва, Н.Ю.; Зайцева, О.В. Влияние штамма дрoжжей на сoстав oрганических кислoт вина. Магарач Винoградарствo И Винoделие 2020, 22, 174–178. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.-T.; Lu, L.; Duan, C.-Q.; Yan, G.-L. The Contribution of Indigenous Non-Saccharomyces Wine Yeast to Improved Aromatic Quality of Cabernet Sauvignon Wines by Spontaneous Fermentation. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 71, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, R.; Wang, W.; Sun, T.; Han, X.; Ai, M.; Huang, S. Study on Nutritional Characteristics, Antioxidant Activity, and Volatile Compounds in Non-Saccharomyces cerevisiae–Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum Co-Fermented Prune Juice. Foods 2025, 14, 1966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Way, M.L.; Jones, J.E.; Longo, R.; Dambergs, R.G.; Swarts, N.D. Regionality of Australian Apple Cider: A Sensory, Chemical and Climate Study. Fermentation 2022, 8, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivit, N.N.; Longo, R.; Kemp, B. The Effect of Non-Saccharomyces and Saccharomyces Non-Cerevisiae Yeasts on Ethanol and Glycerol Levels in Wine. Fermentation 2020, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toure, N.; Atobla, K.; Cisse, M.; Dabonne, S. Bioethanol Production from Cashew (Anacardium occidentale L.) Apple Juice by Batch Fermentation Using Saccharomyces cerevisiae E450. Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2019, 13, 2546–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, N.; Rodrigue, N.; Champagne, C.P. Combined Effects of Sulfites, Temperature, and Agitation Time on Production of Glycerol in Grape Juice by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 2022–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, G.; Taurino, M.; Gerardi, C.; Tufariello, M.; Lenucci, M.; Grieco, F. Yeast Starter Culture Identification to Produce of Red Wines with Enhanced Antioxidant Content. Foods 2024, 13, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grieco, F.; Carluccio, M.A.; Giovinazzo, G. Autochthonous Saccharomyces cerevisiae Starter Cultures Enhance Polyphenols Content, Antioxidant Activity, and Anti-Inflammatory Response of Apulian Red Wines. Foods 2019, 8, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekoue Nguela, J.; Vernhet, A.; Sieczkowski, N.; Brillouet, J.-M. Interactions of Condensed Tannins with Saccharomyces cerevisiae Yeast Cells and Cell Walls: Tannin Location by Microscopy. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 7539–7545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fochesato, A.S.; Cristofolini, A.; Poloni, V.L.; Magnoli, A.; Merkis, C.I.; Dogi, C.A.; Cavaglieri, L.R. Culture Medium and Gastrointestinal Environment Positively Influence the Saccharomyces cerevisiae RC016 Cell Wall Polysaccharide Profile and Aflatoxin B1 Bioadsorption. LWT 2020, 126, 109306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.-R.; Lee, H.-J.; Jeong, K.-H.; Park, B.-R.; Kim, S.-J.; Seo, S.-O. Parabiotic Immunomodulatory Activity of Yeast Cell Wall Polysaccharides from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and S. boulardii. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 123, 106577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Timson, D.J.; Annapure, U.S. Antioxidant Properties and Global Metabolite Screening of the Probiotic Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Var. Boulardii. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 3039–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kliks, J.; Kawa-Rygielska, J.; Gasiński, A.; Rębas, J.; Szumny, A. Changes in the Volatile Composition of Apple and Apple/Pear Ciders Affected by the Different Dilution Rates in the Continuous Fermentation System. LWT 2021, 147, 111630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, C.; Angós, I.; Maté, J.I.; Cornejo, A. Effects of Polyols at Low Concentration on the Release of Sweet Aroma Compounds in Model Soda Beverages. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Arroyo, M.R.; González-Bonilla, S.M. Sensory Characterization and Acceptability of a New Lulo (Solanum quitoense Lam.) Powder-Based Soluble Beverage Using Rapid Evaluation Techniques with Consumers. Foods 2022, 11, 3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, I.; Dubois, G.E.; Clos, J.F.; Wilkens, K.L.; Fosdick, L.E. Development of Rebiana, a Natural, Non-Caloric Sweetener. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2008, 46 (Suppl. S7), S75–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, G.; San Miguel, R.; Hastings, R.; Chutasmit, P.; Trelokedsakul, A. Replication of the Taste of Sugar by Formulation of Noncaloric Sweeteners with Mineral Salt Taste Modulator Compositions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 9469–9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuBois, G.E.; Prakash, I. Non-Caloric Sweeteners, Sweetness Modulators, and Sweetener Enhancers. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 3, 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, K.; Kearsley, M. Sweeteners and Sugar Alternatives in Food Technology; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-1-118-37397-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Madrera, R.; Lobo, A.P.; Alonso, J.J.M. Effect of Cider Maturation on the Chemical and Sensory Characteristics of Fresh Cider Spirits. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Gui, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Tian, L.; Liu, Q.; Wu, Y. Aromatic and Sensorial Profiles of Guichang Kiwi Wine Fermented by Indigenous Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains. J. Food Sci. 2025, 90, e70067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Chen, Y.; Gao, B.; Lyu, X.; Mu, H.; Hao, D.; Qin, Y.; Song, Y.; Jiang, J.; Liu, Y. Impact of Indigenous Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains on Chemical and Sensory Profiles of Xinjiang and Ningxia Sauvignon Blanc Wines. Food Chem. X 2025, 28, 102575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Zou, S.; Dong, L.; Lin, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Ji, C.; Liang, H. Chemical Composition and Flavor Characteristics of Cider Fermented with Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Non-Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Foods 2023, 12, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulero-Cerezo, J.; Tuñón-Molina, A.; Cano-Vicent, A.; Pérez-Colomer, L.; Martí, M.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Probiotic Rosé Wine Made with Saccharomyces cerevisiae Var. boulardii. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 201, LIFE SCIENCES, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mulero-Cerezo, J.; Briz-Redón, Á.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Var. boulardii: Valuable Probiotic Starter for Craft Beer Production. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paula, B.P.; Chávez, D.W.H.; Lemos Junior, W.J.F.; Guerra, A.F.; Corrêa, M.F.D.; Pereira, K.S.; Coelho, M.A.Z. Growth Parameters and Survivability of Saccharomyces boulardii for Probiotic Alcoholic Beverages Development. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazo-Vélez, M.A.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O.; Rosales-Medina, M.F.; Tinoco-Alvear, M.; Briones-García, M. Application of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Var. boulardii in Food Processing: A Review. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 943–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, T.; Vilela, A.; Cosme, F. Chemical and Sensory Characteristics of Fruit Juice and Fruit Fermented Beverages and Their Consumer Acceptance. Beverages 2022, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Cota, G.Y.; López-Villegas, E.O.; Jiménez-Aparicio, A.R.; Hernández-Sánchez, H. Modeling the Ethanol Tolerance of the Probiotic Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Var. Boulardii CNCM I-745 for Its Possible Use in a Functional Beer. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2021, 13, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.P.; Hao, R.X.; Xiao, D.G.; Guo, L.L.; Gai, W.D. Research on the Characteristics and Culture Conditions of Saccharomyces boulardii . Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 343–344, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Apple Juice (AJ) | Pear Juice (PJ) |

|---|---|---|

| Total extract [°Brix] | 11.9 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 0.25 |

| pH [unit] | 3.16 ± 0.06 | 3.61 ± 0.11 |

| GLU [g/L] | 28.72 ± 1.993 | 19.52 ± 0.705 |

| FRU [g/L] | 69.98 ± 2.825 | 68.79 ± 4.123 |

| SucA [g/L] | n.d. | 0.28 ± 0.021 |

| CitA [g/L] | 0.04 ± 0.002 | 0.84 ± 0.043 |

| MalA [g/L] | 5.77 ± 0.406 | 2.01 ± 0.056 |

| LacA [g/L] | 0.03 ± 0.002 | n.d. |

| AceA [g/L] | n.d. | n.d. |

| TarA [g/L] | 0.6 ± 0.043 | n.d. |

| EtOH [g/L] | 0.32 ± 0.01 | 0.17 ± 0.009 |

| GlyOH [g/L] | 0.15 ± 0.013 | n.d. |

| SorOH [g/L] | 3.32 ± 0.327 | 18.25 ± 1.604 |

| Parameter | Fermented with S. boulardii | Fermented with S. cerevisiae | p-Value | Statistical Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLU | 0.05 ± 0.002 | 0.06 ± 0.005 | 0.022 | a/b |

| FRU | 0.62 ± 0.044 | 2.05 ± 0.156 | <0.001 | a/b |

| SucA | 0.54 ± 0.038 | 0.65 ± 0.033 | 0.012 | a/b |

| CitA | n.d. | n.d. | - | - |

| MalA | 5.12 ± 0.232 | 5.85 ± 0.3 | 0.042 | a/b |

| LacA | 0.15 ± 0.006 | 0.28 ± 0.009 | <0.001 | a/b |

| AceA | 0.25 ± 0.009 | 0.06 ± 0.002 | <0.001 | a/b |

| TarA | 1.07 ± 0.096 | 1.06 ± 0.057 | 0.999 | a/a |

| EtOH | 49.01 ± 0.6 | 47.98 ± 1.321 | 0.999 | a/a |

| GlyOH | 4.85 ± 0.172 | 4.38 ± 0.285 | 0.271 | a/a |

| SorOH | 2.96 ± 0.021 | 3.1 ± 0.282 | 0.999 | a/a |

| Parameter | Fermented with S. boulardii | Fermented with S. cerevisiae | p-Value | Statistical Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLU | 0.08 ± 0.008 | 0.01 ± 0.001 | <0.001 | a/b |

| FRU | 1.1 ± 0.059 | 0.98 ± 0.035 | 0.055 | a/a |

| SucA | 0.71 ± 0.063 | 0.69 ± 0.059 | >0.5 | a/a |

| CitA | n.d. | n.d. | - | - |

| MalA | 2.21 ± 0.085 | 2.28 ± 0.112 | >0.4 | a/a |

| LacA | 0.04 ± 0.002 | 0.08 ± 0.003 | <0.001 | a/b |

| AceA | 0.41 ± 0.038 | 0.14 ± 0.011 | <0.001 | a/b |

| TarA | 0.04 ± 0.003 | 0.03 ± 0.001 | 0.005–0.01 | a/b |

| EtOH | 41.28 ± 0.999 | 41.35 ± 3.335 | 0.97 | a/a |

| GlyOH | 4.05 ± 0.101 | 3.73 ± 0.312 | 0.18 | a/a |

| SorOH | 17.26 ± 0.808 | 17.88 ± 1.636 | 0.59 | a/a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Patelski, A.M.; Balcerek, M.; Dziekońska, U.; Pielech-Przybylska, K.; Raczyk, A.; Wasilewska, M.; Dębska, K. Unique Alcoholic Beverages Derived from Pear and Apple Juice Using Probiotic Yeast. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13039. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413039

Patelski AM, Balcerek M, Dziekońska U, Pielech-Przybylska K, Raczyk A, Wasilewska M, Dębska K. Unique Alcoholic Beverages Derived from Pear and Apple Juice Using Probiotic Yeast. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13039. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413039

Chicago/Turabian StylePatelski, Andrea Maria, Maria Balcerek, Urszula Dziekońska, Katarzyna Pielech-Przybylska, Aleksandra Raczyk, Michalina Wasilewska, and Katarzyna Dębska. 2025. "Unique Alcoholic Beverages Derived from Pear and Apple Juice Using Probiotic Yeast" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13039. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413039

APA StylePatelski, A. M., Balcerek, M., Dziekońska, U., Pielech-Przybylska, K., Raczyk, A., Wasilewska, M., & Dębska, K. (2025). Unique Alcoholic Beverages Derived from Pear and Apple Juice Using Probiotic Yeast. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13039. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413039