1. Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) is a technology that uses headsets to generate realistic sensations, simulating a user’s presence in real or imaginary environments [

1]. VR systems typically provide six degrees of freedom, allowing users to move and look around the virtual world [

1]. The concept of VR has evolved since the 1950s, with applications expanding into various fields such as medicine, entertainment, education, and tourism [

2]. VR technologies face challenges beyond compression, including depth acquisition and 3D rendering [

1]. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted VR’s potential for virtual communication and accelerating research [

2]. While VR offers immersive experiences, there is a lack of definitional precision for concepts like reality, perspective, and illusion in the field [

3]. As VR continues to develop, it is crucial for professionals and students to understand its various aspects and potential applications [

2,

4].

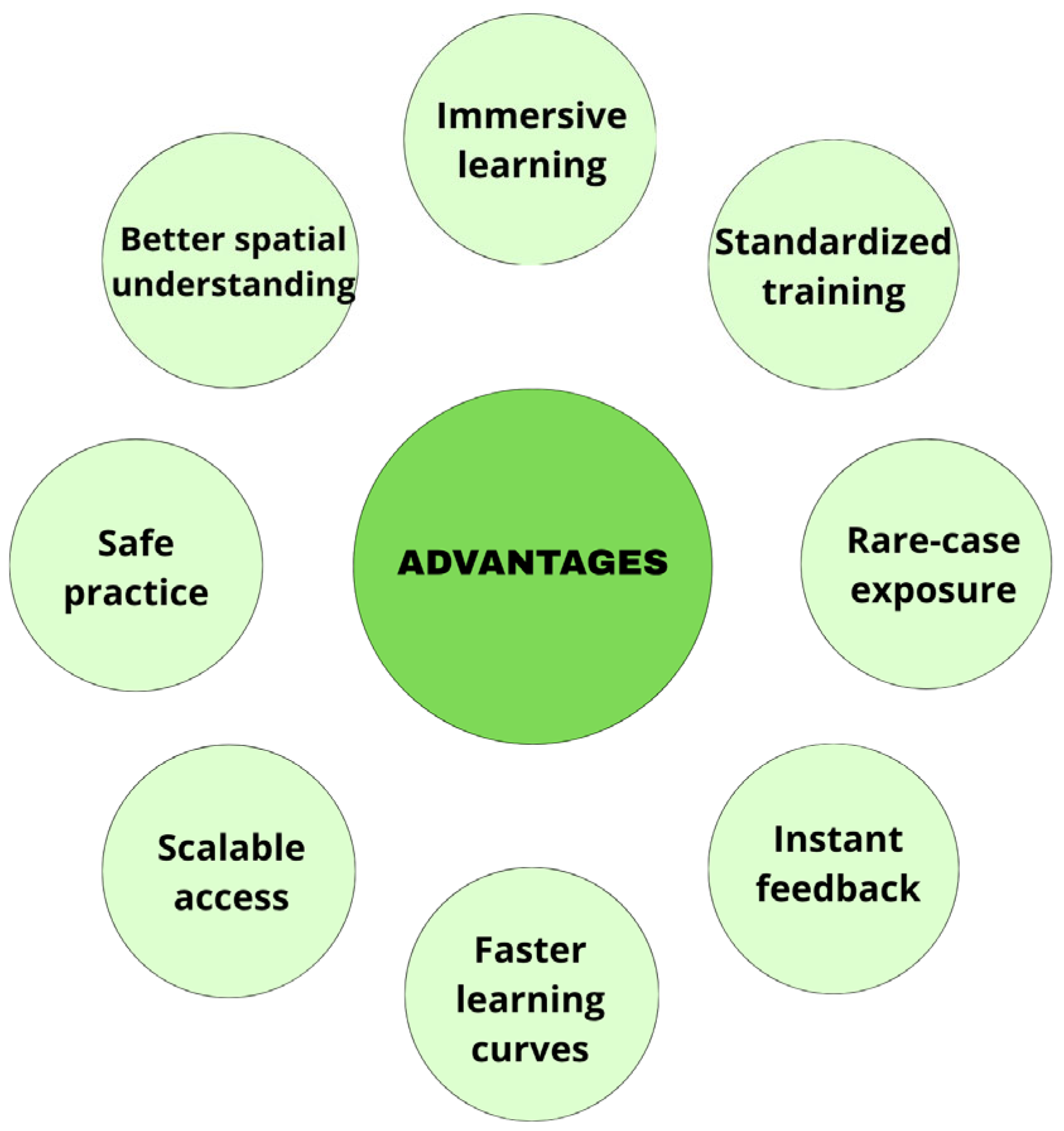

VR improves procedural accuracy, spatial understanding, and learner engagement across preclinical and clinical training, as shown in multiple randomized and observational studies. According to Arjun & Sachith Gowda and Meany et al., VR simulations allow medical students to develop and refine essential procedural skills, deepen their anatomical understanding, and achieve higher diagnostic accuracy. These tools also play a significant role in cultivating critical non-technical skills, such as effective communication, teamwork, and collaboration, which are essential for modern healthcare practice [

5,

6].

Grounded in adult learning principles, VR enables learners to actively apply theoretical knowledge in practical scenarios, supporting continuous improvement through repetitive practice and immediate feedback [

7]. This interactive approach makes VR a powerful educational tool, especially in scenarios requiring precision and decision-making under pressure.

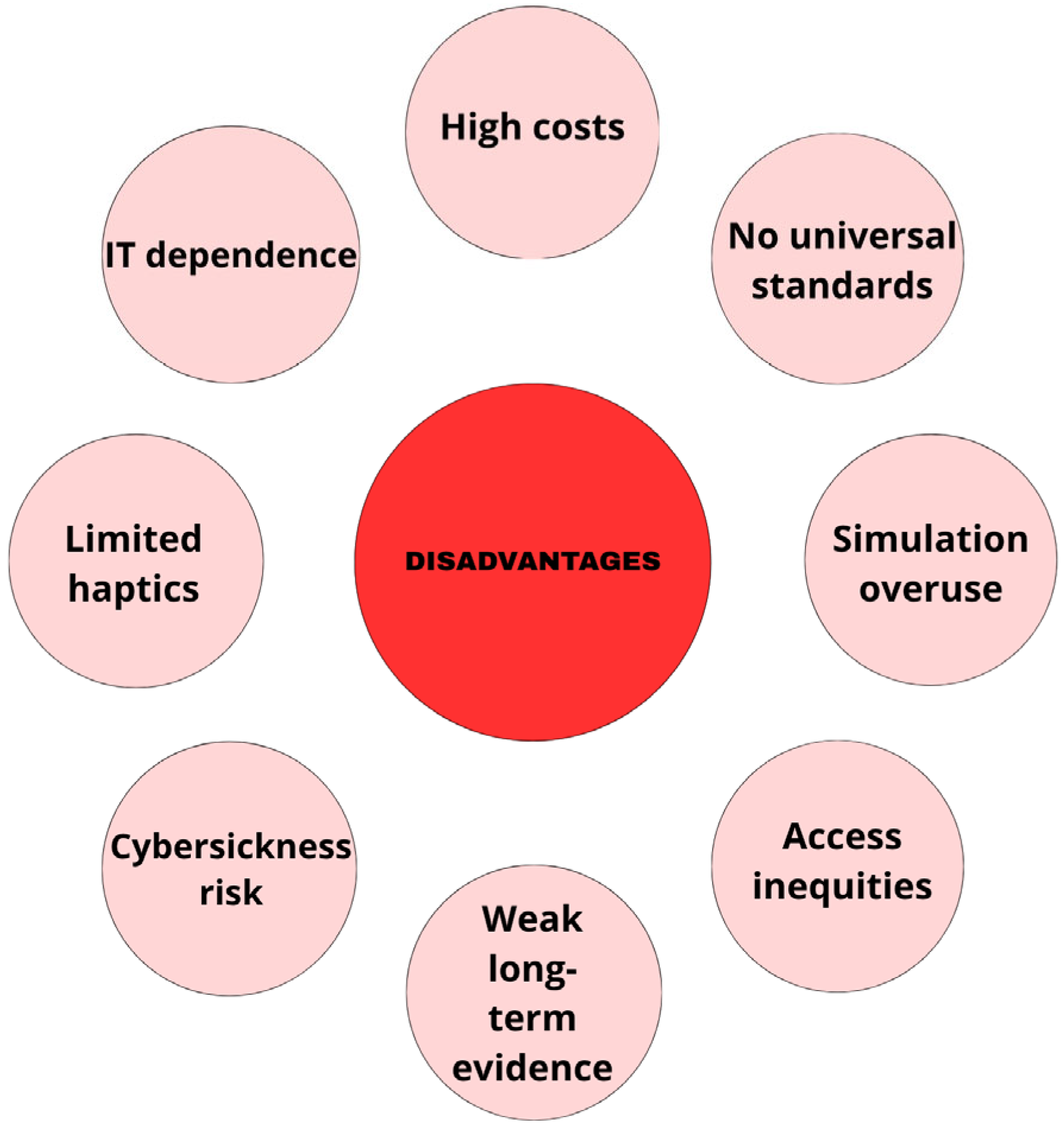

While high costs and technical requirements remain barriers to widespread implementation, VR presents a cost-effective solution in the long term. It offers repeatable, standardized, and on-demand clinical training opportunities that traditional methods struggle to replicate [

5,

8]. Additionally, VR can simulate rare or complex cases, enabling students to gain experience in situations they might not encounter during their regular training. As VR technology continues to evolve, its applications extend beyond education into various aspects of healthcare, including improving patient care, enhancing treatment planning, and advancing telemedicine services [

5]. The integration of VR into medical curricula is steadily gaining momentum worldwide, marking a significant shift in how future healthcare professionals are trained. This innovative approach promises to redefine the standards of medical education and improve the overall quality of healthcare delivery [

8].

The aim of this review was to provide a comprehensive synthesis of how virtual reality has been implemented across diverse domains of medical education, emphasizing both its pedagogical value and practical challenges. By examining evidence from preclinical and clinical disciplines-including anatomy, surgery, anesthesiology, cardiology, neurology, oncology, gastroenterology, ophthalmology, obstetrics and other fields, this review sought to identify overarching trends, strengths, and limitations in the current use of VR. In doing so, it offers an integrative perspective that moves beyond specialty-specific analyses to reveal common educational mechanisms and implementation barriers, such as cost, accessibility, standardization, and technology-induced discomfort. The novelty of this work lies in its cross-disciplinary approach and critical evaluation of VR’s dual role as both a learning enhancer and an organizational innovation within medical curricula. Rather than focusing narrowly on procedural training or single-field applications, this review consolidates data from multiple specialties to illuminate how immersive, interactive environments can support competency-based learning, improve scalability of training, and ultimately reshape the landscape of medical education.

2. Methods

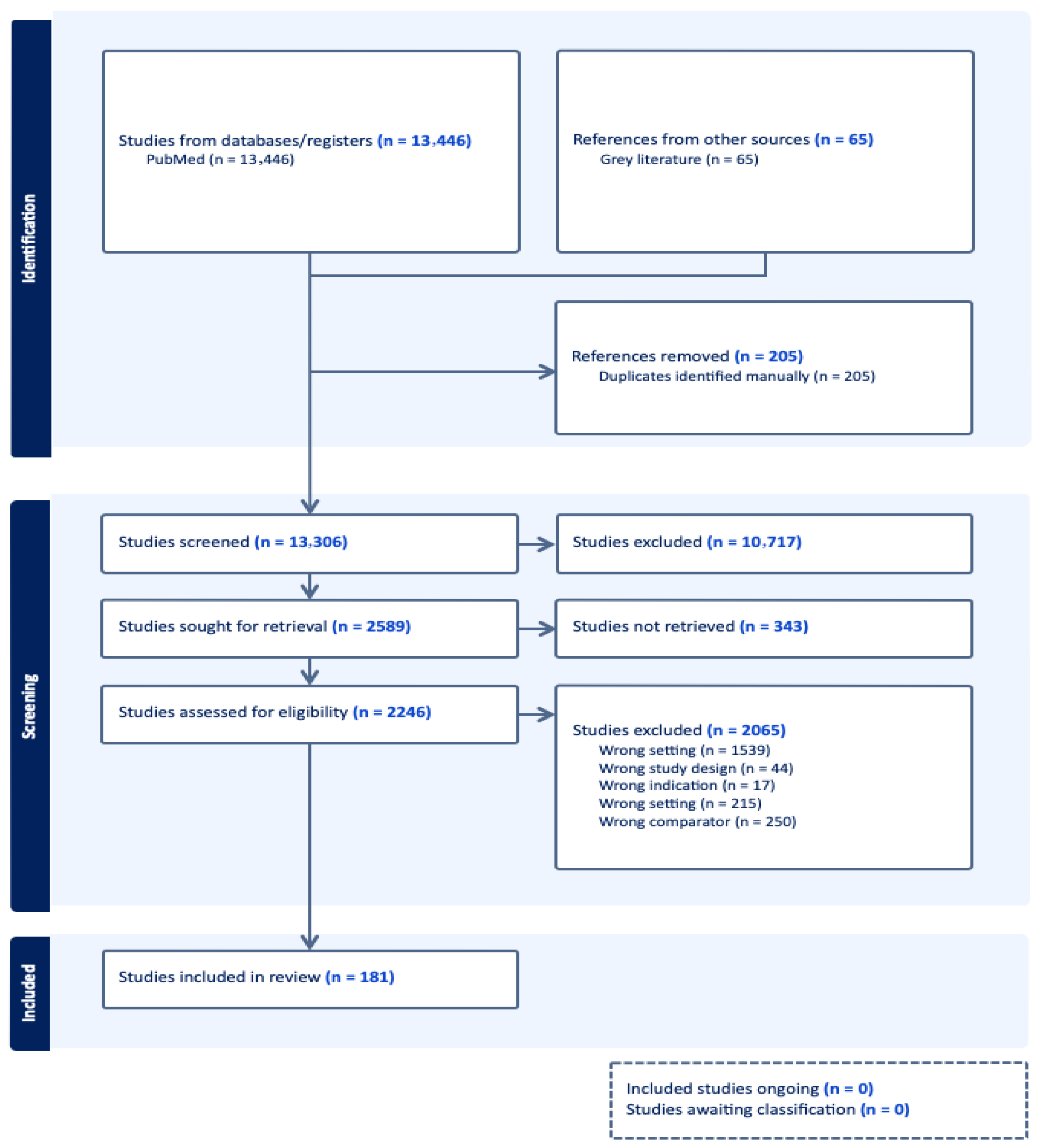

This systematic review was conducted to identify, map, and synthesize current applications of virtual reality (VR) technology in medical education, covering both preclinical and clinical training contexts. The review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2020) guidelines. The PRISMA flowchart illustrating the screening and selection process is presented in

Figure 1.

A comprehensive literature search was performed exclusively in the PubMed database between October 2024 and February 2025, using the following search string: (“virtual reality” OR “VR” OR “head-mounted display” OR “HMD” OR “augmented reality”) AND (“medical education” OR undergrad* OR “residency” OR clerkship* OR “curriculum” OR “simulation” OR “skills training”). The search was limited to English-language publications, with no restrictions on study design or year of publication. Reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles were also screened to identify additional sources. Studies were included if they (1) involved the use of immersive or semi-immersive VR systems in undergraduate, graduate, or continuing medical education; (2) reported measurable educational, technical, or clinical outcomes; (3) were available in full text in English. Exclusion criteria encompassed studies focused solely on augmented or mixed reality without a VR component, technical reports without educational evaluation, and conference abstracts lacking full-text data. Data were extracted on key variables including educational setting (discipline and learner level), type of VR intervention, study design, sample size, comparator (if applicable), outcome measures, and main findings. Particular attention was paid to reported limitations, accessibility and standardization, cybersickness, and cross-study variability in design and assessment methods. Given the heterogeneity of included studies, findings were synthesized narratively to identify overarching trends, benefits, and challenges associated with VR integration in medical education.

PubMed was selected as the sole database due to its exclusive focus on biomedical and clinical sciences, high indexing coverage of medical education research, and the prevalence of VR-related educational studies in journals indexed primarily in Medline. While the use of a single database may introduce a risk of missing records indexed only in Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, or Cochrane, this limitation is acknowledged and has been addressed by performing manual reference screening of all included articles.

The search strategy was intentionally focused on core VR terminology to ensure high specificity and avoid excessive retrieval of non-VR simulation literature. Terms such as ‘simulation-based education,’ ‘clinical skills training,’ or ‘virtual patient’ were not included because they frequently index studies involving mannequin simulators, standardized patients, or non-immersive screen-based tools rather than true virtual reality. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that excluding these broader terms may reduce sensitivity, and this limitation has been noted in the revised manuscript.

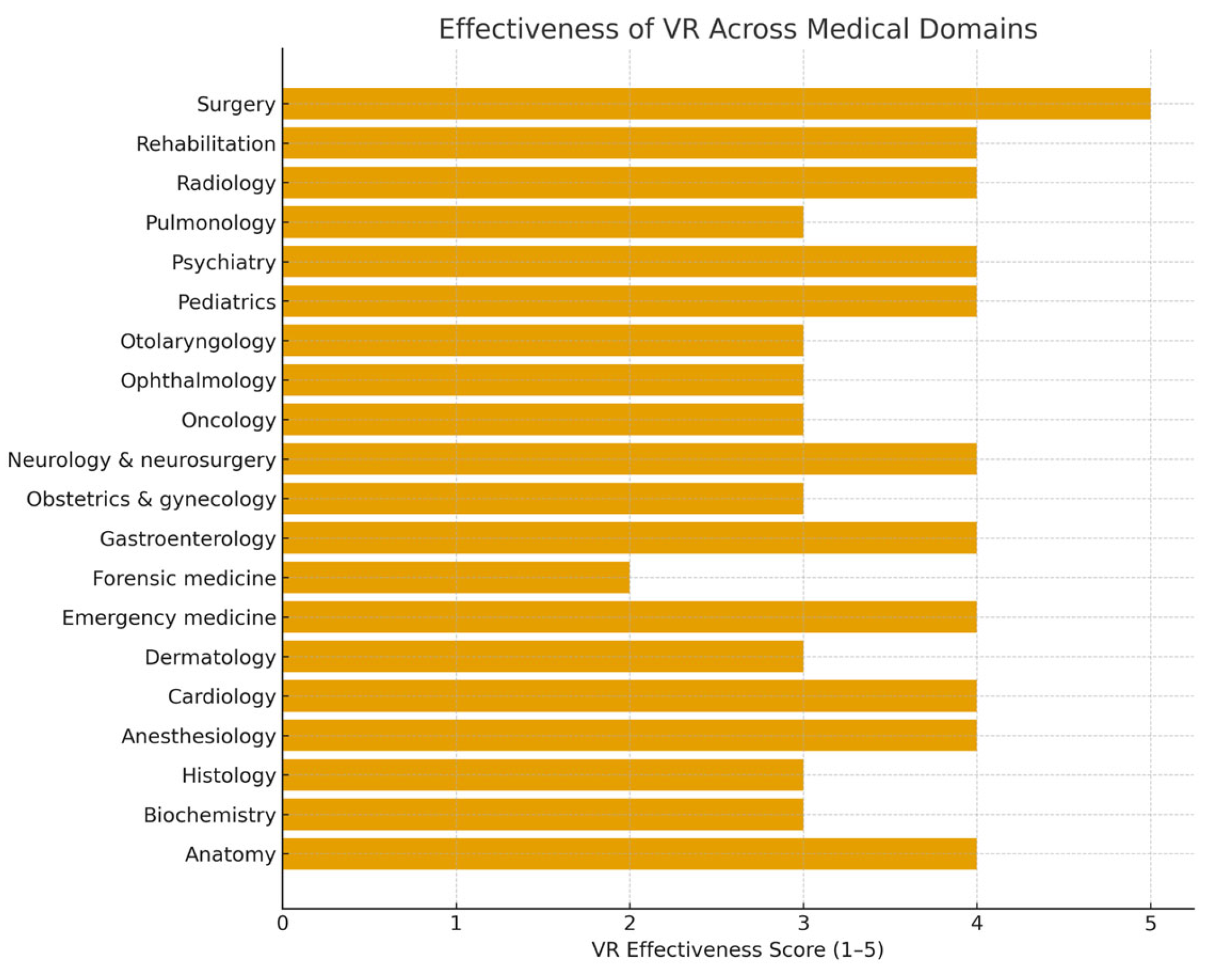

To enable structured comparison across heterogeneous educational domains, we developed a custom 5-point VR effectiveness scoring system. This scale was constructed using four predefined criteria commonly applied in evidence synthesis: (1) number of studies available within a domain, (2) consistency of reported findings across studies, (3) magnitude of educational or clinical effect, and (4) methodological quality based on study design and clarity of outcome reporting. Each criterion was assessed qualitatively, and domains were assigned a global score from 1 (very limited evidence) to 5 (strong, consistent evidence).

Established frameworks such as GRADE, AMSTAR, or MERSQI were not used because they are designed to evaluate the methodological quality of individual studies or systematic reviews rather than to compare multiple VR application domains with highly heterogeneous outcomes and study designs. The custom scale, therefore, provides a pragmatic and transparent approach for high-level cross-domain comparison.

A narrative synthesis approach was used to integrate the heterogeneous evidence. Thematic grouping was performed by categorizing studies into four predefined domains: (1) preclinical education, (2) clinical education, (3) patient-facing VR applications, and (4) cross-domain or multi-specialty uses. Data extraction followed a structured template including study design, learner level, VR modality, comparator, outcomes, and key findings. Coding was performed manually using these predefined thematic categories. To ensure accuracy and reduce extraction bias, all extracted data were independently verified by a second reviewer, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. This process aligns with recommended narrative synthesis practices for reviews where meta-analysis is not feasible due to heterogeneity.

3. Results

This section presents the main findings of the review, organized across both preclinical and clinical domains. The results summarize representative VR applications, their measured educational effects, and the strength of supporting evidence. The first group of findings concerns preclinical subjects, beginning with anatomy.

3.1. Preclinical Education

3.1.1. Anatomy

Virtual reality (VR) has rapidly become a transformative tool in the field of anatomy education, providing innovative methods for teaching and learning complex human anatomical structures. By offering immersive and interactive experiences, VR addresses some of the limitations of traditional approaches, such as reliance on cadaveric dissection and static 2D images. This technology allows learners to visualize, explore, and manipulate detailed 3D models of the human body, thereby enhancing their comprehension of spatial relationships and intricate biological systems [

9,

10,

11].

One of the most significant benefits of VR is its ability to create a safe, controlled, and customizable learning environment. Unlike cadaveric dissection, which requires physical specimens and specialized facilities, VR platforms enable students to practice repeatedly without the constraints of availability or ethical concerns. Users can zoom in, rotate, and dissect virtual models, gaining a deeper understanding of anatomical layers and structures that might be less accessible during traditional dissections [

10,

12]. VR is also particularly effective in addressing the challenges of understanding complex anatomical relationships. For example, students often struggle to visualize the 3D spatial positioning of organs, muscles, and vessels within the human body using only textbooks or 2D atlases. VR provides an intuitive and engaging way to overcome this challenge, offering a lifelike representation of anatomy that improves spatial awareness and knowledge retention [

12,

13]. Moreover, the adaptability of VR allows for various modes of implementation. Guided sessions led by instructors can provide structured learning experiences, while independent exploration fosters self-paced study. Additionally, VR enables real-time collaborative learning, where students and educators can interact within the same virtual space, enhancing teamwork and communication skills [

9].

Several studies have highlighted the positive impact of VR on anatomy education. Research indicates that students who engage with VR tools demonstrate improved knowledge retention and practical skills compared to those using traditional methods alone [

12]. VR has also been shown to boost students’ confidence in identifying and understanding anatomical structures, as the interactive nature of the technology promotes active learning and problem-solving [

14]. Beyond the classroom, VR holds promise for ongoing professional development in medical fields. Surgeons, for instance, can use VR to simulate procedures and refine their understanding of anatomical variations, leading to safer and more precise outcomes in clinical practice [

15].

3.1.2. Biochemistry

VR is emerging as a transformative tool in biochemistry education, offering immersive experiences that enhance student understanding, engagement, and retention of complex concepts. With its ability to simulate 3D environments, VR provides a dynamic platform for visualizing intricate biochemical processes and molecular interactions that are often challenging to grasp using traditional teaching methods. For instance, VR applications have been effectively employed to teach complex pathways such as the citric acid cycle, fostering deeper comprehension among students [

16]. One of the key strengths of VR lies in its capability to render interactive molecular visualizations. Utilizing Protein Data Bank (PDB) files, VR platforms allow students to explore detailed 3D models of biomolecules, including DNA, collagen, and hemoglobin, offering an unparalleled perspective on their spatial arrangements [

17,

18]. This interactive approach has been shown to significantly improve spatial recognition skills, which are essential for understanding molecular biology and biochemistry [

19]. Research has highlighted the positive impact of VR on student engagement and learning outcomes in undergraduate biochemistry courses. Students using VR tools report higher levels of motivation, improved spatial reasoning, and a greater intention to continue learning with the technology [

16]. Additionally, VR has proven effective in enhancing retention of abstract concepts by enabling students to manipulate and observe molecular structures in real time [

20].

Despite its numerous advantages, the application of VR in biochemistry education faces certain challenges. Studies suggest mixed results regarding its overall effectiveness in biomedical science education, particularly when compared to traditional methods [

21]. Moreover, scalability remains a concern, especially for large tertiary education cohorts, as the cost and technical requirements of VR hardware and software can be prohibitive [

22].

3.1.3. Histology

VR is revolutionizing histology education by offering students immersive and interactive ways to explore the microscopic structure and function of tissues. Unlike traditional teaching methods that rely on two-dimensional images from textbooks or slides, VR provides three-dimensional models of cells and tissues, allowing students to manipulate and examine structures from different perspectives. Studies have demonstrated that VR-based histology learning enhances students’ spatial understanding and ability to visualize complex cellular relationships, leading to improved comprehension and retention of key concepts [

23]. One significant advantage of VR in histology education is its ability to create a dynamic learning environment where students can interact with tissue models and simulate microscopic examination. For instance, a study found that VR applications allowed learners to practice identifying histological structures and diagnosing pathological changes, which significantly improved their diagnostic accuracy compared to traditional methods [

24]. Furthermore, VR’s capacity to simulate rare or complex histological samples ensures that students gain exposure to a broader range of tissue types, which is not always feasible in traditional laboratory settings due to limitations in slide availability [

25]. The interactive nature of VR-based histology tools also promotes active learning. By allowing students to manipulate digital tissue models and explore cellular features in detail, VR encourages engagement and critical thinking. In a study examining student perceptions, participants reported higher levels of satisfaction and motivation when using VR for histology compared to conventional methods. They emphasized that the immersive experience made learning more enjoyable and reduced the cognitive load associated with interpreting two-dimensional images [

23]. Additionally, VR has proven valuable in bridging the gap between theoretical and practical knowledge in histology. By simulating real-world scenarios, such as the histological analysis of tissue biopsies, VR helps students apply their knowledge to clinical contexts. This prepares them for future diagnostic and research roles, fostering a deeper understanding of the relevance of histology in medical practice [

26]. Another critical benefit of VR in histology education is its ability to accommodate diverse learning needs. Students with varying levels of prior knowledge or spatial reasoning skills can benefit from the customizable and self-paced nature of VR modules. This adaptability ensures that all learners can achieve mastery, regardless of their starting point. Research has shown that VR not only improves academic performance but also reduces anxiety associated with traditional histology exams by providing a supportive and non-intimidating learning environment [

27].

As the technology continues to advance, VR’s potential in histology education is expanding. Future developments may include integrating artificial intelligence into VR platforms to provide real-time feedback and personalized learning pathways. This would further enhance students’ ability to grasp complex histological concepts and apply them in clinical and research settings. By combining interactive 3D visualization with an engaging and flexible learning approach, VR is poised to become an indispensable tool in the teaching of histology [

23].

3.2. Clinical Education

3.2.1. Anesthesiology

An astounding 310 million major surgeries are conducted annually around the world, necessitating a large and skilled group of anesthesiologists [

28]. The use of mannequin-based simulation as the gold standard for training without endangering patients was pioneered by the discipline of anesthesiology, but because of the quick development of VR technology, these new tools are now easily accessible at a fair price [

29,

30]. By offering a realistic, dynamic, and interactive learning environment, they remove geographic barriers to medical education. Interactive sessions can be led asynchronously by bots with artificial intelligence-driven algorithms or synchronously by in-person trainers in real time. The patients (avatars) are safe, and it is simple to analyze the performance data for evaluation and feedback [

30].

Training simulations are the first issue that VR addresses. Lately, training in medicine has shifted away from time-based training and toward competency-based training. If it takes a trainee 50 attempts to become skilled at intubation, adopting a VR simulator that increases in complexity and variety could help them get there sooner. The changing scenarios would increase the learning curve. They do so more frequently and in less time than a conventional training approach, which would require the trainee to wait hours for each surgery to be finished before having the opportunity to do another intubation procedure [

29]. The only drawback of one-person VR instruction is that it might give students the impression that they can solve their own problems [

31].

Having effective communication in the operating room is one of the most important factors in a successful procedure. In a study by Chheang et al., two VR scenarios have been suggested to promote communication between the anesthesiologist and surgeons. A scenario called “undetected bleeding” occurs when a surgeon performs laparoscopic surgery and fails to notice a hemorrhage. So, only the anesthesiologist can spot the issue by focusing on changes in the vital signs. The surgeon can then recognize and stop the bleeding, for example, by placing a clip on the bleeding blood vessel, thanks to the anesthesiologist’s notification to them of the problem. In the second case, the anesthesiologist and surgeon must communicate since there is not enough muscle relaxant medicine. The purpose of this scenario is to get the surgeons to look for signs of low muscular relaxation and alert the anesthesiologist to adjust the dosage. This improves situation awareness, a vital cognitive skill, as well as nontechnical skills like teamwork [

31].

As head-mounted devices are inexpensive and simple to set up—in a study by Alaterre et al., the median set up time was 2 min, with a median session duration of 25 min—VR technology can also be utilized to reduce patients’ discomfort and anxiety during regional anesthesia. The patients experienced more short- and long-term satisfaction than the control group, who did not receive the quick intraoperative VR distraction procedure. Also, it was linked to a significant decline in the frequency of intraoperative hemodynamic abnormalities, which dropped from 16% in the sample without VR therapy to 2% in patients who received the distraction. As a result, the study led 94% of the participants to declare that they would like to use this technology again for future surgery under regional anesthesia [

32].

3.2.2. Cardiology

VR has two main applications in cardiology: first, it may be used to provide instruction and education for cardiologists in training, residents, and practicing cardiologists; and second, it can be utilized by patients to receive medical therapy and rehabilitation. For learning and practicing complex operations like cardiac catheterization, VR can offer a realistic and immersive experience. It has the potential to be a dynamic, interactive diagnostic and planning tool. The VR-to-OR programs have their roots in the Vascular Interventional System Training (VIST) simulator from the early 2000s, which mimics the human cardiovascular system [

33].

Another early study [

34] demonstrates that even a low-fidelity VR simulator can significantly boost clinical performance by 29%, and with technology advancing for more than 20 years, the new era of VR-to-OR may completely alter teaching methods; only doctors who can evidently perform the procedure successfully on the simulator will be permitted to perform it on actual patients. It will mark the end of a time when the “see one, do one, teach one” principle governed procedure-based specializations [

35]. This will reduce the hazards for patients and enable regular evaluations of a doctor’s technical abilities and even clinical judgment throughout their career. In the investigation of the viability of proficiency-based training in a coronary angiography simulator, it was observed that the group trained in VR exhibited reduced fluoroscopy and total procedure durations compared to the control group [

36].

Galvez et al. reported a high willingness to participate in VR training among undergraduate medical students, which, with the use of VR, allowed the researchers to present anatomical characteristics that are not readily discernible in deceased bodies [

37]. Since the patient’s scans may be easily transformed into the simulator, VR can also improve understanding of the anatomy specific to the patient before and during patient treatments. An immersive 3D visualization of a computer tomography scan provides the surgeon with a more accurate simulation of the patient’s heart in this scenario [

38].

VR has also emerged as a promising tool for CPR training. Cerezo Espinosa et al. reported higher theoretical scores in the VR group (9.28 vs. 7.78/10) and better CPR performance, including a higher compression rate (97.5 vs. 80.9/min) and greater compression depth (34.0 vs. 27.9 mm) compared with the control group [

39]. Additionally, the utilization of augmented reality picture guidance has been found to enhance navigational capabilities during beating heart mitral valve replacement procedures. In the study by Chu et al., AR reduced the tool-tip distance error from 16.8 ± 10.9 mm to 5.2 ± 2.4 mm, shortened navigation time from 92.0 ± 84.5 s to 16.7 ± 8.0 s, and decreased path length from 1128.9 ± 931.1 mm to 225.2 ± 120.3 mm. These quantitative gains provide clearer evidence of AR’s efficacy compared with transesophageal echocardiography alone [

40]. The utilization of VR and 3D-printed models has been observed as a viable approach in interventions aimed at addressing congenital heart disease, wherein a comprehensive comprehension of intricate anatomical structures is required [

41]. Clinical 3D modeling can be conducted by employing data generated from cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) or computed tomography (CT). The visualization of patient-specific anatomy was achieved by the utilization of 3D-printed models, digital flat-screen models, and VR techniques. The surgical repair solutions were developed through the utilization of both proprietary and open-source computer-aided design (CAD)-based modeling tools. According to the findings of Ghosh et al., a total of 112 individual cases involving 3D modeling were conducted at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Cardiac Center between 2018 and 2020. Out of the total, 16 instances were carried out with the intention of serving instructional objectives, while the remaining 96 examples were employed in a clinical context to facilitate surgical and/or procedural decision-making. The primary reasons for modeling in this study were difficult biventricular repair (n = 30, 31%) and correction of numerous ventricular septal defects (VSD) (n = 11, 12%). By employing a multidisciplinary approach, these techniques can be effectively included in pre-procedural care, thereby enabling children with very intricate cardiac disease to avail themselves of state-of-the-art diagnostic imaging tools [

41].

VR can also be used for patient counseling and education. The patient is given the chance to provide more informed consent by being made aware of their illness or the surgery they will soon undergo. More compliance, satisfaction, and engagement will follow greater understanding, which is ideal and advantageous for the patient. A systematic review by García-Bravo et al. suggests using VR to improve cardiovascular patients’ physical fitness during cardiac rehabilitation. Many of the studies analyzed indicated multiple positive results in the VR intervention group. The results include increased heart rate, lower pain perception, increased walking capacity, increased energy, improved physical activity, and increased rehabilitation motivation and compliance. The methodology ranged from excellent to bad in the analyzed studies, showing the need for further investigation [

42].

3.2.3. Dermatology

Skin diseases are among the most common health issues worldwide, ranging from mild conditions like acne to life-threatening illnesses such as melanoma. Their diagnosis and treatment often require a detailed understanding of skin anatomy and pathology, as well as precision during procedures. Despite advancements in dermatological care, challenges remain in providing efficient training for specialists, educating patients, and managing pain or anxiety during treatments. VR offers innovative solutions to these challenges by enhancing medical training, improving patient experiences, and supporting the development of new approaches to dermatological care.

As an example of VR use in training students or young doctors, the “VR Scenario Skin Cancer Screening” program utilized in dermatology courses at the University of Münster can be highlighted [

43]. In this created virtual environment, students interact with a virtual patient, performing tasks such as collecting medical history, obtaining consent, and examining skin lesions using tools like a dermatoscope. The program standardizes training conditions, ensuring that all participants are exposed to the same challenges, regardless of patient availability. Students found the VR simulation to be a valuable addition to their curriculum, particularly for building confidence and competence in identifying skin conditions such as melanomas. Despite the novelty of the technology, students rated the simulation as intuitive and easy to use. The immersive and interactive nature of VR also proved highly engaging, fostering emotional involvement, which research has shown to enhance learning and memory retention [

43].

Chou et al. conducted a similar prospective study in China to assess the Virtual Clinical Dermatological Decision Support System (VCDDSS) for its impact on diagnostic accuracy and medical education. Fifty-one sixth-year medical students, thirteen dermatology residents, and a consultant dermatologist diagnosed thirteen patients. After a brief 5 min VCDDSS introduction, students reviewed medical histories and conducted face-to-face exams, recording two preliminary diagnoses without the system. Next, they used VCDDSS to input clinical findings and receive ranked differential diagnoses, selecting two final diagnoses. The process added 4 min on average, with the total diagnostic time around 10 min. Diagnoses by the consultant dermatologist served as the standard. VCDDSS increased diagnostic accuracy by 18.75% (

p < 0.01), highlighting its potential to reduce errors, improve care, and optimize resources. Participants praised its accessibility, user-friendly interface, high-quality imaging, and functionality, demonstrating its value in medical training [

44].

VR can also directly influence the treatment of dermatological patients by addressing pain and anxiety associated with chronic conditions and painful procedures. In a case study focusing on a patient with gluteal hidradenitis, VR-induced hypnosis (VRH) significantly reduced pain intensity, pain unpleasantness, and anxiety [

45]. The patient, who experienced it, reported less time thinking about pain after VRH sessions. These effects were observed on each day of treatment, regardless of variations in opioid analgesic use, highlighting VRH’s potential as a complementary tool rather than a replacement for pharmacologic interventions [

45]. The simultaneous use of VR and audiovisual distractions (AVD) shows promise as a nonpharmacological method for managing pruritus by leveraging the brain’s ability to inhibit itch sensations through distraction. Both methods involve engaging patients with interactive computer games, which significantly reduce itch intensity and observed scratching behaviors. These effects occur almost immediately as patients focus on the game, transitioning from discomfort to relief. The mechanisms underlying this benefit include the activation of inhibitory pathways in the central nervous system, which counterbalance pruritic stimuli in ways similar to how distraction alleviates pain [

46].

VR can also play a significant role in promoting healthy habits, as demonstrated by Australian scientists who developed a VR game to encourage sun protection and melanoma prevention [

47]. The game proved to be highly engaging and effective in conveying complex health messages in a simplified manner. All 18 participants praised its immersive, gamified approach, with only 11% (2/18) reporting mild. Unlike traditional materials such as brochures, the VR experience fostered a deeper emotional connection and maintained participants’ attention more effectively, which indicates that VR can be an effective method for educating the public about skin diseases [

47].

3.2.4. Emergency Medicine

The clinical specialty of emergency medicine (EM) demands quick judgment in conditions that are frequently complicated and time-sensitive [

48]. Every six minutes on average, emergency physicians are interrupted. They must learn how to multitask in this hectic, risky, and disruptive setting because disturbances raise the chance of mistakes. Since the atmosphere and severity of trauma in a crisis may be unlike anything the doctor has encountered or been prepared for, entering this specialty can be particularly difficult. This discrepancy could cause dissonance, which can manifest as worry, guilt, shame, anger, or tension.

More practice in disaster drills would result in better patient outcomes because it would increase accuracy and efficiency in a mass casualty environment, which is a setting where cognitive dissonance among doctors caused by affective overload might interfere with the application of knowledge and skills [

49]. Because of this, it is critical for emergency physicians to be exposed to a wide range of situations; before the widespread usage of VR, this required expensive standardized patient (SP) disaster simulations.

According to pre- and post-test analysis [

50], the VR disaster drill in the cited study had a similar effect on learning, and there was no discernible difference in the physicians’ ability to execute Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (START) during an SP disaster simulation and while utilizing a VR disaster drill. For seriously injured patients, proper triage is crucial to their lives. Although the expenses of creating VR scenarios can be high (

$20,000–

$100,000), they are more cost-effective than real-life disaster drills when spread out over the number of possible students, applications, and recurring scenario use. Overall, research implies that VR, either individually or in conjunction with SP drills, can offer a realistic option for instructing EM staff in the management of mass casualties. With a focus on situational decision-making, VR may be ideally adapted for crisis medical situations. Learners may repeat these scenarios virtually endlessly in a safe setting that permits failure, provides feedback, and allows for a high number of trials. In a large-cohort implementation study of 129 medical students, 91% agreed that VR “can convey complex issues quickly”, 88% that VR is a useful addition to mannequin-based courses, and 72% believed it could even replace them [

48].

VR may also be used well in EM to lessen discomfort and suffering. While performing unpleasant bedside operations, including lumbar punctures, intravenous catheter placement, and laceration repair, the emergency department has examined the use of traditional passive tactics like TV, music, or other audiovisual stimuli as a diversion. Yet, since VR creates a sensation of “presence,” it is more effective at distracting. It immerses the patient in a three-dimensional world and engages all their senses [

51]. VR has been shown through fMRI tests to offer pain-relieving effects that are on par with a moderate dosage of opioids [

52]. According to a hypothesis outlining how VR works to lessen pain and anxiety, patients have limited attentional capacity, and if their attention can be distracted, they may react to pain signals more slowly. In support of this mechanism, one controlled study found that immersive VR increased children’s pressure-pain threshold by 136 kPa (95% CI 112–161;

p < 0.0001) and reduced anxiety scores by 7 points (modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale; 95% CI −8 to −5;

p < 0.0001) compared with control conditions [

53].

When exposed to VR during painful stimuli, healthy subjects’ functional magnetic resonance imaging revealed a higher than 50% decrease in pain-related brain activity in 5 regions of the brain [

52]. It may have an immediate effect and carries a minimal risk of negative side effects. Moreover, it restricts the use of drugs like opioids that might pose a risk of addiction. A meta-analysis [

54] focused on the usage of VR during wound care and rehabilitation after burns indicated a statistically significant distinction between VR treatment and standard care in terms of pain outcomes during wound care procedures (SMD = − 0.49; 95% CI [− 0.78, − 0.15]; I

2 = 41%). Furthermore, subgroup analysis revealed a similar significant difference when immersive VR was utilized (SMD = − 0.71; 95% CI [− 1.07, − 0.36]; I

2 = 0%).

The effect of VR on patients who presented with acute and subacute musculoskeletal pain, stomach discomfort, headaches, and other symptoms was examined in research by Birrenbach et al. [

55]. Regardless of gender, a substantial decrease in pain and anxiety was seen following the 20 min VR distraction simulation. Interestingly, the simulation performed well even when analgesics were given before the operation. VR is practical for use in the ED and may help ED patients feel less pain and anxiety. The subject’s ethnic background, level of education, and health all have an impact on how VR affects them [

51]. Even though each patient is affected differently, the overall impact is beneficial and gives patients hope for the future.

3.2.5. Forensic Medicine

Forensic medicine plays a crucial role in uncovering the truth behind criminal cases, disasters, and unexplained deaths, requiring meticulous investigation and precise interpretation of evidence. From crime scene analysis to courtroom presentations, the field demands highly specialized skills and technologies. Despite advancements in forensic techniques, challenges persist in training professionals, reconstructing complex scenarios, and effectively communicating findings in legal settings. VR has emerged as a groundbreaking tool to address these challenges, offering immersive simulations, enhanced visualization of evidence, and innovative methods for education and analysis. By integrating VR into forensic medicine, professionals can gain new insights, improve accuracy, and transform how justice is pursued.

Koller et al. demonstrated the potential of VR to enhance forensic medicine by improving injury analysis, though the approach has both strengths and limitations. Their study used VR to measure injuries on a 3D mannequin model, achieving greater precision than traditional forensic photography, though slightly less accurate than photogrammetry on a computer screen. VR excels in providing an immersive, detailed examination of complex or curved surfaces, supported by tools like point-to-point measurement and user scaling, which reduce errors and improve visualization. However, challenges include lower texture resolution in VR models compared to desktop software and the need for manual adjustments to enhance clarity [

56]. VR is increasingly being integrated into forensic science education as an innovative approach to teaching practical skills. By simulating realistic crime scene environments, VR allows students to engage in tasks such as identifying evidence, hypothesizing scenarios, and practicing documentation techniques, including photography.

These immersive experiences provide a controlled yet dynamic environment for learners to apply theoretical knowledge, bridging the gap between classroom instruction and real-world application. In one implementation, VR recreated a detailed crime scene where participants could navigate using intuitive controls, interact with objects, and follow investigative procedures. The set up included features like evidence markers and a photographic tool to mimic professional workflows. Such applications not only align with curricular learning outcomes but also offer scalable and versatile training opportunities, paving the way for broader adoption in forensic science programs [

57]. Japanese researchers have explored the application of VR to analyze and reconstruct accident scenarios, offering unique insights into the dynamics of injuries [

58]. By utilizing VR, investigators can create immersive 3D environments that replicate the scene of an incident, including the positioning of the victim, the vehicle or object involved, and the surrounding environment. This method allows for a detailed examination of how injuries may have occurred and provides a visual representation that can be shared with non-medical stakeholders such as law enforcement, attorneys, and jurors.

VR’s ability to simulate events with high precision enhances the understanding of complex injury mechanisms, supporting forensic pathologists in testing hypotheses and conveying findings more effectively. Although there are challenges related to computational demands and model simplification, advancements in VR technology are expected to address these issues, further improving its utility in forensic investigations [

58]. VR may also find application in ballistic analysis [

59]. Unlike traditional tools requiring a mouse and keyboard, this immersive system allows direct manipulation of point clouds using natural hand gestures, eliminating constraints and enabling greater precision. Forensic experts can examine evidence from any angle, even “inside” a casing, with detailed magnification and without losing clarity. This approach overcomes limitations of conventional 2D and 3D rendering, ensuring critical details are not obscured. A key strength of the system is its ability to analyze both 2D and 3D data simultaneously, addressing the limitations of current methods that focus exclusively on specific features like firing pin impressions or bullet striations. The system also supports comparisons of multiple point clouds at once, making it highly versatile and scalable. All actions performed by the expert are logged to ensure repeatability and validation, facilitating collaboration and consistency across law enforcement agencies. The immersive VR interface enhances the accuracy and efficiency of ballistics analysis while paving the way for international standardization. Experts in different locations can collaboratively analyze evidence in real time, creating a shared framework for firearm identification. Early experiments have shown promising results, and future work will focus on integrating machine learning to further automate and refine the analysis process. This innovative method sets a new standard for forensic ballistics, offering unparalleled accuracy and flexibility [

59].

3.2.6. Gastroenterology

The intricate nature of gastrointestinal anatomy and the growing prevalence of conditions such as colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and functional disorders present significant challenges to healthcare professionals. This highlights the importance of training both new and experienced gastroenterology specialists with increasing effectiveness, a goal where VR technology can provide significant support. Endoscopy simulators were first developed in the late 1960s with mechanical models, which were neither very realistic nor useful. These evolved into more advanced types, including live animal models, ex vivo simulators, and virtual simulators. While animal models offer the most realistic experience, their use is limited by ethical concerns, costs, and logistical challenges. Ex vivo simulators, using plastic materials and animal organs, are cost-effective for scenario-based training but require frequent tissue replacement, increasing costs and limiting accessibility.

Virtual simulators, introduced in the 1980s, are now the most promising tools for endoscopy training, benefiting from rapid advancements in computer technology [

60]. The GI Mentor is a great example of an evidence-based simulator for training of gastrointestinal upper and lower endoscopic procedures. It offers a comprehensive library of modules with more than 120 tasks and virtual patient cases. The simulators provide multiple training opportunities, starting with constructive endoscopy skill tasks, through true-to-life patient cases ranging from simple diagnostic procedures to advanced ERCP (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography), EUS (endoscopic ultrasound), and ESD (endoscopic submucosal dissection) procedures [

61]. The meta-analysis conducted by Mahmood et al. demonstrates that VR simulation has a significant positive impact on training gastroenterologists, particularly in endoscopic procedures like flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy. VR simulation enhances technical skills, including the ability to perform independent procedures, control the endoscope, and identify pathologies. It also contributes to faster procedure completion times and greater competence in reaching anatomical landmarks such as the transverse colon and cecum. Trainees who used VR simulation displayed higher levels of confidence and skill compared to those who received traditional or no simulation-based training. In addition to improving technical abilities, VR simulation positively affects patient outcomes by reducing procedure-related errors and, in some cases, improving patient comfort. Its benefits are especially pronounced during the early stages of training, where it accelerates the development of core competencies [

62].

Furthermore, VR simulation often matches or outperforms conventional teaching methods, making it an effective and valuable tool in gastroenterology training [

62]. However, it is worth noting that VR technology can bring benefits not only in the training of doctors, but also to patients undergoing, for example, a colonoscopy. Veldhuijzen et al. conducted a pilot study in which a group of patients undergoing colonoscopy wore VR glasses during the procedure, which displayed a relaxing video of tropical islands and forests in the Caribbean. The study showed that VR glasses during colonoscopy are acceptable to patients and do not compromise endoscopic technical success. Patients reported that the VR experience was pleasant and distracting, with 9 out of 10 participants in a pilot colonoscopy study describing the use of VR glasses as “positive” [

63]. Moreover, Siripongsaporn et al. conducted a similar randomized controlled trial in which VR goggles were used to educate patients scheduled for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) about the procedure and its purpose. While the results indicated that this form of education did not significantly reduce anxiety—for the VR group of 58 patients the mean anxiety score dropped from 41.4 ± 9.6 to 37.1 ± 10.8, while the control group (49 patients) fell from 41.9 ± 7.7 to 38.9 ± 8.07 (

p = 0.354)—it may have enhanced patients’ memory and understanding of the procedure for patients undergoing unsedated EGD; the recall-questionnaire scores were significantly higher in the VR group (4.7 ± 0.4) compared with control (3.9 ± 1.0;

p = 0.001) [

64].

What is more, VR can also serve as a viable treatment option as a standardized VR Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) program designed for patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [

65]. The program, structured as an 8-week self-administered protocol, consists of various VR environments arranged to resemble a virtual clinic. Each session lasts between 5 and 20 min and incorporates psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, relaxation strategies, and problem-solving techniques. Additional CBT exercises and daily messages were delivered via a web app to reinforce learning and encourage the application of skills to everyday life. The VR program features several “treatment rooms” with distinct purposes. For instance, the “Exam Room” helped patients better understand the connection between the brain and gut through visuals and psychoeducation. The “Chill Room” focused on relaxation, offering calming environments and guided breathing exercises. The “Theater of the Mind” targeted cognitive restructuring, helping participants reframe IBS-related thoughts through problem-solving and exposure techniques. Finally, the “Zoom Out Room” facilitated self-reflection, promoting perspective-taking and self-compassion through structured exercises. The results showed that the program effectively helped patients better understand their condition and adopt healthier thought patterns. Many participants found the sessions calming and relatable, reporting improvements in self-awareness, reduced self-blame, and a greater sense of connection to others with IBS. While further research is needed, these findings highlight the potential of VR-based CBT to provide accessible, cost-effective behavioral interventions for IBS and similar gastrointestinal conditions such as Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis [

65].

3.2.7. Obstetrics and Gynecology

VR is playing an increasingly significant role in gynecology and obstetrics education, offering medical students, residents, and specialists immersive environments to practice clinical skills and refine surgical techniques. VR-based simulators allow trainees to perform procedures like laparoscopic surgeries, hysteroscopy, and cesarean deliveries in a risk-free setting. For instance, a study demonstrated that VR simulation improved technical performance and reduced error rates among residents performing laparoscopic procedures, providing a safe and efficient way to acquire hands-on experience [

66].

Expanding on the use of immersive tools in gynecologic education, a quasi-experimental study evaluated a 27 min 360° VR video of a gentle Cesarean section among 89 medical students. Although VR exposure did not significantly improve long-term procedural or obstetric knowledge compared with conventional teaching (recall scores 74.6 vs. 73.6; internship grades 7.75 vs. 7.83), it elicited strong learner engagement: 100% of participants rated the material as useful, 90% as inspiring, and 83.4% expressed that more VR content should be incorporated. Moreover, fewer VR-trained students felt the need for additional in-person CS observations (46.4% vs. 68.8%;

p = 0.04), suggesting increased perceived preparedness. These findings indicate that, while knowledge gains may be comparable, VR offers notable qualitative and quantitative advantages in student engagement within gynecologic education [

67].

One of the significant advantages of VR is its ability to replicate rare or high-risk obstetric scenarios, such as shoulder dystocia or postpartum hemorrhage. These simulations allow learners to practice critical decision-making and teamwork in time-sensitive situations, improving their confidence and preparedness for real-world emergencies. For example, VR-based training for shoulder dystocia management was found to enhance knowledge retention and clinical performance among obstetrics trainees [

68,

69]. Additionally, studies have highlighted that VR training fosters non-technical skills such as communication and leadership, which are essential during multidisciplinary obstetric emergencies [

70].

VR also offers innovative solutions for patient-centered care. Simulations designed to teach patient counseling and shared decision-making have been shown to improve communication skills in scenarios like discussing contraceptive options or explaining prenatal diagnostic tests [

71]. Building on this, VR-enhanced training has also demonstrated measurable gains in learners’ clinical knowledge and decision-making performance. In a randomized controlled trial with 105 participants, students who completed a VR-based simulation achieved significantly higher scores on a post-training mini-test, with a median of 42 (IQR 37–48) compared to 36 (IQR 32–40) in the control group (

p < 0.001). Moreover, 83% of VR users reported that the immersive format improved their ability to integrate clinical information, and over 70% felt more prepared to apply these skills in patient encounters [

72].

In surgical education, VR simulators for hysteroscopy and laparoscopic gynecology have been shown to significantly enhance skills acquisition and transfer to the operating room [

67]. Similarly, VR has proven to reduce the learning curve for complex laparoscopic procedures like salpingectomy or myomectomy, helping trainees achieve proficiency in less time [

73].

Another notable benefit of VR is its capacity to improve clinical decision-making and procedural efficiency in high-stakes obstetric scenarios. In a randomized crossover study with 61 participants, a 360° VR training video on managing shoulder dystocia using the modified ALSO

® HELP-RER algorithm led to significantly higher post-training performance scores (median 7.0 vs. 6.5;

p = 0.01) and a reduction in diagnosis-to-delivery time from 99 s to 85.5 s (

p = 0.02). Participants also demonstrated a lower cognitive workload during the VR phase, with TLX scores decreasing from 68 to 57 (

p = 0.04) [

69]. In addition to these performance gains, large-scale evidence further supports VR’s effectiveness in clinically relevant training contexts. A recent meta-analysis of 92 randomized trials involving 7133 participants reported substantial reductions in procedural pain when VR was used, with a pooled standardized mean difference (SMD) of −0.78 (95% CI −1.00 to −0.57). Even greater effects were observed in pediatric populations (SMD −0.91, 95% CI −1.26 to −0.56) and during venepuncture procedures (SMD −0.99, 95% CI −1.52 to −0.46). These robust quantitative outcomes demonstrate VR’s capacity to enhance the realism and emotional fidelity of simulated clinical encounters, reinforcing its value within both preclinical and clinical education [

74].

Overall, VR is transforming gynecology and obstetrics education by enhancing technical proficiency, improving non-technical skills, and expanding access to training. Its ability to simulate complex scenarios and provide a safe, interactive learning environment makes it a powerful tool for advancing medical education in this field [

75].

3.2.8. Neurology and Neurosurgery

Virtual Reality and augmented reality are emerging as promising tools in neurosurgery and neurology, offering innovative methods to overcome challenges associated with traditional surgical and diagnostic approaches. AR and VR can simulate and replicate specific environments, enabling surgeons to train and plan complex procedures such as awake craniotomy (AC), which allows for the removal of pathological lesions from critical brain regions while monitoring cortical and subcortical functions simultaneously. There is evidence suggesting that both surgeons and patients benefit from the application of AR and VR in AC, with VR used for mapping language, vision, and social cognition, and AR employed in preoperative white matter dissection, visualization, and intraoperative navigation [

76]. By allowing neurosurgeons to explore artificial environments and interact within them, VR facilitates simulation-based training and preoperative planning for real-world craniotomies. Brain mapping through direct electrical stimulation of cortical and subcortical areas minimizes the risk of permanent neurological deficits by enabling real-time monitoring of motor, language, and visual functions. Additionally, VR helps overcome intraoperative limitations in assessing complex cognitive and social functions, such as facial expressions or gaze, providing an immersive training environment that shortens the learning curve. The distinction between AR and VR lies in the degree of immersion-AR overlays 2D and 3D computer-generated images onto the real-world view, whereas VR fully immerses the user in a computer-generated environment capable of assessing various cognitive domains, including auditory associations, working memory, and praxis.

In neurosurgery, AR overlays essential data, such as CT/MRI and functional imaging, onto the surgical field, providing critical information about tumor margins and adjacent structures, reducing surgical risk and cognitive load while improving team coordination. Projection techniques perform best for superficial tumors, whereas head-up AR techniques are more suitable for small, deeply located lesions. Studies indicate that patients undergoing AC experience reduced stress, anxiety, and depression, and VR may further alleviate intraoperative distress through interactions with virtual avatars. Gliomas, accounting for 78% of all malignant primary brain tumors, remain a major focus of AR-assisted surgery. AR effectively maps patient-specific neuroanatomy onto the surgical field, enhancing visualization of deep-seated structures, vascular systems, and hemodynamics, and addressing challenges such as brain shift during surgery by updating virtual scenes using multimodal imaging and functional data [

77]. The use of AR in surgery via Heads-Up Displays (HUD), Head-Mounted Displays (HMD), microscopes, and devices such as HoloLens or Magic Leap has improved surgical accuracy, focus, and safety.

Cerebrovascular and interventional neurosurgery also benefit from VR through immersive modeling and training, allowing for personalized visualization of complex anatomy and improved procedural precision. VR enhances diagnostic accuracy, reduces intraoperative cognitive load, and improves efficiency, particularly among novice surgeons. Moreover, VR facilitates teleproctoring, enabling global collaboration and remote surgical mentoring, which became particularly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic [

78]. Telemedicine applications of VR allow interactive consultations between surgeons and patients within a “connected reality,” supporting real-time verbal, visual, and manual communication. Compared to traditional human or animal models, VR-based training is low-cost, non-invasive, infinitely repeatable, and adaptable to numerous clinical scenarios, making it a valuable educational tool.

Several VR systems, such as the NeuroTouch simulator developed at McGill University, provide structured, multi-level neurosurgical training that assesses psychomotor aptitude, cognitive engagement, and technical proficiency [

79,

80,

81,

82,

83]. Similarly, Human Patient SimulatorTM and trauma craniotomy simulators have demonstrated significant educational benefits in neurosurgical critical care and emergency procedures, providing safe, realistic training environments [

84,

85,

86,

87,

88]. Preoperative planning software such as NeuroPlanner, utilizing 2D and 3D atlases of the brain, enhances stereotactic trajectory planning, segmentation, and visualization of complex anatomy [

89,

90,

91]. Clinical trials confirm that VR-based surgical planning improves anatomical comprehension, reduces operative time, shortens hospitalization, and lowers complication rates [

92,

93,

94]. Furthermore, VR’s ability to map optic radiations, language, and social cognition in awake craniotomy procedures has significantly advanced intraoperative monitoring and patient engagement [

95,

96,

97,

98].

Despite its advantages, VR sickness, manifesting as nausea or headaches, may limit its use; thus, identifying at-risk individuals remains essential [

96,

97,

98,

99]. Nevertheless, AR and VR continue to enhance medical education, preoperative planning, intraoperative assistance, and surgical precision. AR’s ability to integrate digital data directly into the operative field shortens decision-making time and enhances focus by minimizing shifts in attention between the surgical field and external screens. In addition, AR has applications in skull reconstruction, endoscopic surgery, and deep brain stimulation by providing real-time visualization of hidden anatomical structures, improving safety and efficiency [

100]. Collectively, these technologies accelerate learning, bridge knowledge gaps between trainees and experienced neurosurgeons, and promote equitable access to high-quality neurosurgical education worldwide [

101].

3.2.9. Oncology

VR and AR have been employed in the field of radiation oncology education as immersive digital learning tools. Unique learning experiences are facilitated by the utilization of first-person scenarios, wherein learners are afforded the opportunity to actively alter the surrounding environment. An example of Virtual Reality for Radiation Training (VERT) is a simulation that affords learners the opportunity to engage in practice sessions within a virtual treatment bunker, featuring a radiotherapy linear accelerator. AR, in contrast, superimposes digital things onto the physical environment, enhancing real-world experiences. Although the available evidence regarding the pedagogical efficacy of immersive VR and AR in the context of cancer education is limited, these technologies present several advantages, including the ability to engage in infinite practice sessions, receive rapid feedback, and enhance spatial conceptualization. The aforementioned technologies possess the capacity to significantly transform the field of oncology education through the provision of adaptable, captivating, and personalized learning opportunities [

102].

VR has also been used to support patient education in radiation oncology. In a prospective study involving 43 patients, 74% reported improved understanding of their radiotherapy plan and 57% reported reduced anxiety after viewing an individualized VR simulation of the treatment process. The VR environment enabled patients to visualize beam paths and treatment positioning based on their own imaging data, which enhanced engagement and clarified the rationale behind the procedure. This finding demonstrates the potential of VR technology as an effective supplementary instructional aid for cancer patients who are preparing to undergo radiotherapy [

103]. VR-based rehabilitation improves adherence and training intensity through gamified, multisensory environments and has demonstrated benefits for chronic pain, fatigue, lymphedema, motor function, and chemotherapy-induced neuropathy [

104,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113]. In cancer survivors, VR-based programs have also shown high adherence rates (over 90%) and a significant reduction in cancer-related fatigue, with a standardized mean difference of −0.77 (95% CI −1.04 to −0.50), further highlighting VR’s capacity to produce measurable clinical improvements [

104]. The favorable results provide evidence in favor of incorporating VR technology into cancer rehabilitation programs to improve patient outcomes and overall well-being. Rooney et al. assert that the utilization of simulation-based medical education (SBME) in the field of radiation oncology is primarily focused on the instruction of learners in the practice of contouring. This process entails the precise identification and delineation of tumor boundaries or pertinent organs by mapping [

114]. The precise delineation of contours is of utmost importance in the field of radiation oncology, as it ensures the accurate administration of therapeutic radiation to the desired target region while limiting the potential harm to adjacent healthy tissues. The function of treatment planning and execution is of utmost importance, as it significantly impacts the efficacy of radiation therapy and, subsequently, the results experienced by patients. In the realm of intensity-modulated radiation therapy, there exists data indicating that mistakes in contouring, specifically when performed by healthcare professionals who have limited exposure to only a handful of cases, may have a detrimental impact on patient outcomes [

115].

VR has recently been developed as an innovative method of nonpharmacological analgesic therapy for cancer-related medical procedures and chemotherapy.

The potential enduring repercussions of cancer and its treatment encompass a range of physical and psychological manifestations, including but not limited to pain, exhaustion, anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment [

116]. Research has revealed a negative correlation between psychological distress and cognitive function among individuals diagnosed with cancer [

117,

118,

119]. Previous studies have shown that cancer-related fatigue and mood changes, such as anxiety and sadness, significantly affect cognitive functioning and quality of life in cancer patients [

120,

121,

122]. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Hao et al. identified seventeen studies involving a total of 799 cancer patients. The findings of this study revealed that, based on within-group pooled analysis, patients exhibited significant improvements in pain (

p < 0.001), fatigue (

p < 0.001), anxiety (

p < 0.001), upper extremity function (

p < 0.001), and quality of life (

p = 0.008) following a VR intervention [

123]. Another systematic review [

124] investigated the use of immersive VR for pain management, specifically examining five studies. Only two investigations demonstrated statistical significance [

125,

126]. However, it is important to note that the power of their findings is compromised due to the limited sample sizes, with each study including fewer than 20 patients. Interestingly, the aforementioned research employed active VR in their software, enabling patients to actively engage and interact inside the virtual environment. In contrast, the remaining three studies utilized passive VR. One potential rationale for this observed positive impact is that increased patient engagement may result in heightened immersion and presence, facilitating a more pronounced cognitive diversion from the painful stimulus [

127].

3.2.10. Ophthalmology

VR is redefining ophthalmology by offering, e.g., immersive, hands-on training opportunities for medical students, residents, and practicing specialists or new diagnostic possibilities. Unlike traditional methods, VR-based simulations provide safe and controlled environments to practice essential skills, bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and clinical expertise. One such tool, the Eyesi Slit Lamp simulator, allows trainees to practice examination techniques in a stress-free setting, enhancing their ability to diagnose conditions and prepare for practical exams. Its ability to deliver consistent, realistic scenarios has proven invaluable in improving both accuracy and confidence among learners [

128]. Another notable platform is VRmNet (previously known as EyesiNET), which supports advanced ophthalmology training. This system includes modules on ophthalmoscopy and phacoemulsification, providing a structured learning pathway for trainees. Research has shown that users of these simulations not only gain surgical confidence but also require less time to master intricate surgical procedures such as cataract surgeries [

129]. These platforms are particularly effective in reducing the learning curve for complex techniques, allowing practitioners to gain proficiency more quickly compared to traditional methods.

Beyond surgical training, VR excels in the development of diagnostic skills. For example, simulation-based training has demonstrated significant improvements in diagnosing conditions such as strabismus, where VR’s interactive and repeatable nature allows users to refine their diagnostic acumen without the need for patient involvement [

130]. Moreover, VR has also been adapted for simulating routine examinations, such as pupil assessments. These applications provide trainees with practical, real-world skills while minimizing the risks associated with early clinical encounters [

131].

An essential advantage of VR is its ability to address the limitations of traditional educational tools. Unlike textbooks or live patient interactions, VR simulations offer a repeatable and interactive learning environment. Trainees can practice scenarios multiple times to gain mastery, correcting mistakes without fear of harm to patients. This flexibility makes VR particularly valuable in highly specialized fields like ophthalmology, where the stakes are high, and the margin for error is minimal [

132].

Furthermore, the effectiveness of VR as a teaching tool extends beyond the technical aspects of ophthalmology. By incorporating features such as three-dimensional visualization and real-time feedback, VR enhances spatial understanding and procedural precision, both of which are critical in this field. For instance, training modules on phacoemulsification allow students to experience complex procedures in a manner that mimics real-life scenarios, fostering both technical skills and confidence [

133].

Another significant contribution of VR is its ability to adapt to the evolving needs of ophthalmology education. While physical models or cadaver-based training may have limitations in terms of availability, cost, or variability, VR provides a scalable and accessible alternative. Institutions can implement VR training widely, ensuring that all learners receive standardized, high-quality educational experiences. This not only democratizes access to advanced training tools but also ensures a consistent level of competency among practitioners.

As the technology evolves, VR’s role in ophthalmology education continues to grow. Its application extends beyond skill acquisition to include assessment and certification, enabling educators to objectively evaluate performance through metrics like precision, completion time, and error rates. This data-driven approach further strengthens VR’s position as a cornerstone of modern medical education [

134].

By integrating VR into ophthalmology education, the field is poised to produce more skilled, confident, and well-prepared clinicians. The ability to repeatedly practice complex procedures and diagnoses in a safe, simulated environment is revolutionizing the way future specialists are trained, ultimately leading to improved patient outcomes [

129].

3.2.11. Otolaryngology

Temporal bone surgery is a technically demanding and high-risk procedure, especially in the anatomically complex area. Safe temporal bone surgery emphasizes a thorough understanding of anatomy and the development of techniques, requiring guidance from an experienced otologic surgeon and years of practice. Currently, the gold standard in temporal bone surgery training involves using cadaveric temporal bones, but this method has its limitations. In addition to cadaveric bones, two commonly used simulation platforms described in the literature are 3D-printed models and VR simulation platforms. The application of VR simulation in preoperative planning and training can not only increase the surgeon’s confidence but also reduce operating room time and potentially improve patient treatment outcomes. It allows the exploration of various approaches tailored to specific patient data. One specific area with significant potential impact is cochlear implantation. The effectiveness of patients with cochlear implants depends largely on the electrode placement and patient-specific factors such as cochlear anatomy, which varies among individuals. Preoperative imaging can facilitate the selection of an appropriate electrode array based on the length of the cochlear duct or the desired angle of insertion from the residual acoustic hearing degree. Furthermore, a preoperative surgical trial enables the surgeon to practice the transfacial approach and determine whether, in a particular patient, the orientation of the cochlear basal turn is suitable for the round window or for access through cochleostomy. Integrating VR simulation into preoperative planning and cochlear implant surgical trials would allow surgeons to experiment with different methods of placing cochlear implants based on patient-specific data to achieve optimal outcomes. Besides applications related to cochlear implantation, the use of VR simulation in preoperative planning and surgical trials should be extended to include additional procedures in anatomically complex areas, such as the mastoid apex. Optimizing the selection of the appropriate surgical approach, such as subcochlear access, sublabyrinthine access, or transmastoid access, can be achieved through experimenting with different trajectories, strongly dependent on the anatomy of the specific patient and the ventilation patterns of the mastoid/squamous part. In the case of patients with residual hearing, improving the choice of access to lateral skull base tumors is also possible through a better understanding of the anatomical details of the patient’s bone. Specific evaluation functions, fully automated by VR platforms, can compensate for the time constraints faced by experienced surgeons, whose time is limited by clinical duties. Technological progress will only increase the accuracy and functionality of simulations, allowing for better utilization in training and clinically significant purposes, such as preoperative planning and trials. In otologic surgery, given the diversity of complex procedures and the required technical skills in temporal bone surgeries, this technology finds a particular application [

135]. Technical simulation training replicates clinical tasks or events for educational purposes using cadaver models, physical replicas, or computer-generated VR systems. It allows trainees to practice and learn from mistakes safely, without risking patients or incurring operating room costs. Studies, such as those using the virtual reality temporal bone simulator, demonstrate that these systems can reliably differentiate skill levels among trainees and assess their readiness to perform real procedures.

The expert’s opinion correlated with previous drilling results during cadaveric procedures, and a tendency to differentiate based on experience with the VR TB simulator was observed. VR TB simulators can prove beneficial as they allow for both formative and summative assessment of participants’ performances. Analyzing the results, especially for residents divided by otology experience, we believe that the VR TB simulator is suitable for evaluating trainees in the transitional stage from laboratory learning to operative practice. Having an objective assessment at this stage can be particularly valuable in training programs, especially when participants have limited otology experience or a short time for staff training. Performance, measured based on hand movement analysis, was consistently better on the VR TB simulator than on actual cadavers. This may be due to inherent differences in hand movement measurements, such as the size of the operative field, drill movement range, or tactile feedback [

136,

137]. Most studies confirm that VR-based temporal bone simulation (TBS) is an effective training tool for otolaryngology residents. With advancing technology, improved imaging, automation, and gaming-based innovations will enhance simulation precision and realism, making preoperative VR training more accessible and effective. Although it cannot replace real surgical experience, VR remains a valuable and promising component of surgical education [

138].

3.2.12. Pediatrics

Medical procedures frequently cause discomfort, worry, and pain. These emotions, especially in children, not only have a negative impact on comfort levels during medical operations, but they are also linked to negative outcomes like efforts to flee, slow recovery, irregular feeding and sleeping patterns, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. Interventions are also required to deal with pain and anxiety in pediatric patients because they can cause patients to put off receiving medical care [

139]. VR provides preoperative anxiety reduction without physical or budgetary restrictions. It can be accomplished by educating patients about their conditions, treatments, and procedures, as well as by exposing them to unfamiliar settings like operating rooms or MRI scanners. This can lessen their anxiety and help them get desensitized to these worries. Due to its greater control over the stimulus’s anxiety level, VR exposure can be seen as a useful substitute for conventional exposure [

140]. A study by Ryu et al. attempted to simplify the process by introducing patients to the operating room (OR) and the induction of anesthesia, which is often the event during which anxiety in children peaks. This was performed since pre-operative anxiety in children is frequent (50 to 70%). Pediatric patients played a 5 min VR game that gave them a first-person view of the preoperative phase and general anesthesia induction [

140]. This, along with the appearance of well-known cartoon characters from “Hello Carbot,” encouraged teamwork and accustomed players to the process. The concept of game aspects like progression, exploration, difficulty, and rewards was introduced. The objective was to destroy the germ monster while engaging in and exploring the OR setting and learning how to breathe through a facial oxygen mask. Patients in the gamification group consequently demonstrated greater compliance than those in the control group. According to the findings of a meta-analysis [

141], it appears that interactive video games have a significant impact on reducing children’s procedural pain ([SMD] = −0.43; 95% CI: −0.67 to −0.20), anxiety (SMD = −0.61; 95% CI: −0.88 to −0.34), and caregivers’ procedural anxiety (SMD = −0.31; 95% CI: −0.58 to −0.04). It is important to notice that the number of studies regarding this topic is still severely limited and that the sample size is most often small, which only prompts further widespread investigation. VR also plays an important role in enhancing the lives of children with disabilities. Berg et al. found that the utilization of Wii games in children with Down syndrome has the potential to serve as a beneficial intervention for enhancing upper limb coordination, manual dexterity, balance, postural stability, and control over stability limits [

142]. Ip et al. conducted a study focusing on children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder, which revealed notable enhancements in the areas of emotion expression, regulation, and social–emotional reciprocity [

143]. Regrettably, despite the presence of certain studies that demonstrate encouraging outcomes, meta-analyses conducted on both subjects yield insufficient findings [

144,

145]. This lack of definite evidence prevents the assertion that VR-based treatments can enhance the efficacy of conventional treatments. The findings of a systematic review performed by Kothgassner et al. on the efficacy of virtual reality exposure therapy (VRET) for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents indicate that participants demonstrate significant clinical improvements in anxiety symptoms subsequent to undergoing VRET. However, the large absence of controlled studies contrasts with the significant promise of VR as a treatment for addressing anxiety problems in children and adolescents. Despite the existing evidence of VRET in adult populations, further study is warranted to investigate its efficacy in younger cohorts. Due to the limited research questions, such as: how long does the novelty of VR treatment last among pediatric patients? Cannot be confidently answered, which calls for further exploration of this topic [