Mechanism of Burial Depth Effect on Recovery Under Different Coupling Models: Response and Simplification

Abstract

1. Introduction

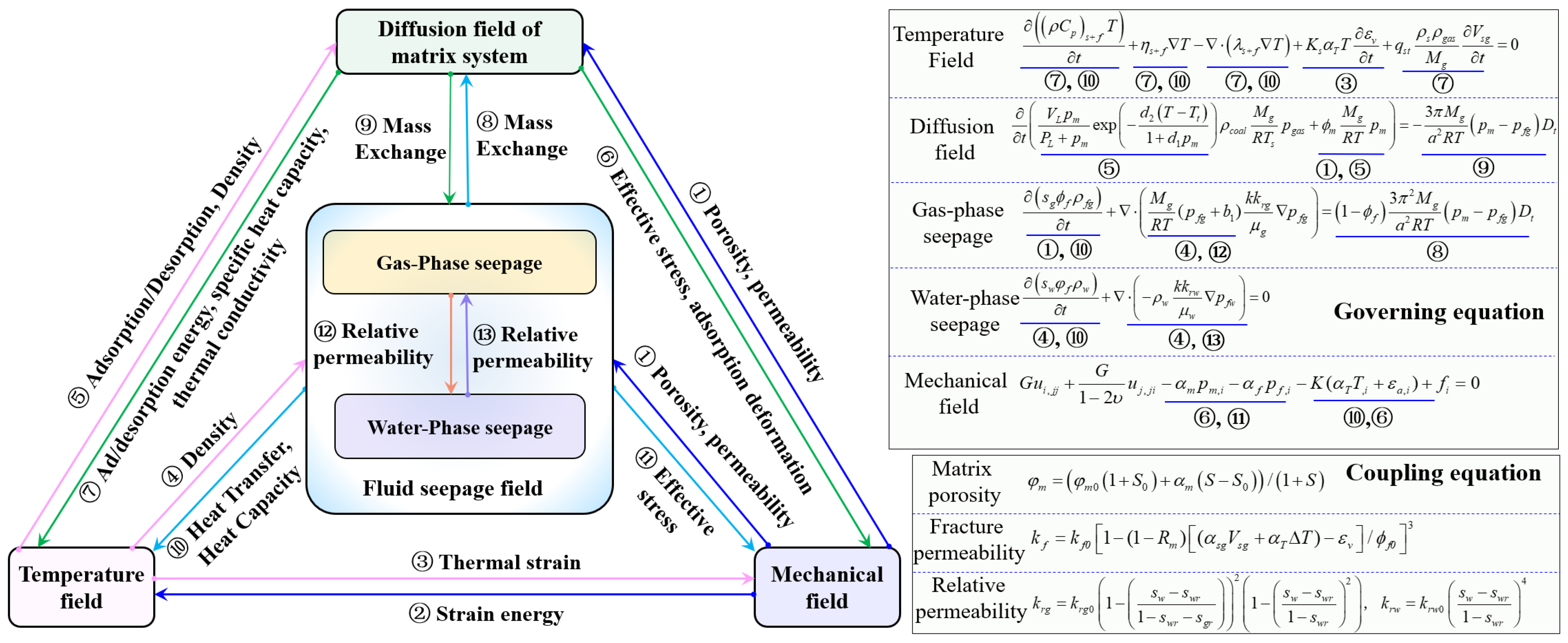

2. TP-D-THM Coupling Model

2.1. Model Assumptions

2.2. Fracture-System Fluid Transport Equation

2.3. Matrix-System Diffusion Equation

2.4. Governing Equation for the Temperature Field

2.5. Governing Equation for the Mechanical Field

2.6. Coupling Terms

3. Effects of Different Coupling Schemes on CBM Production

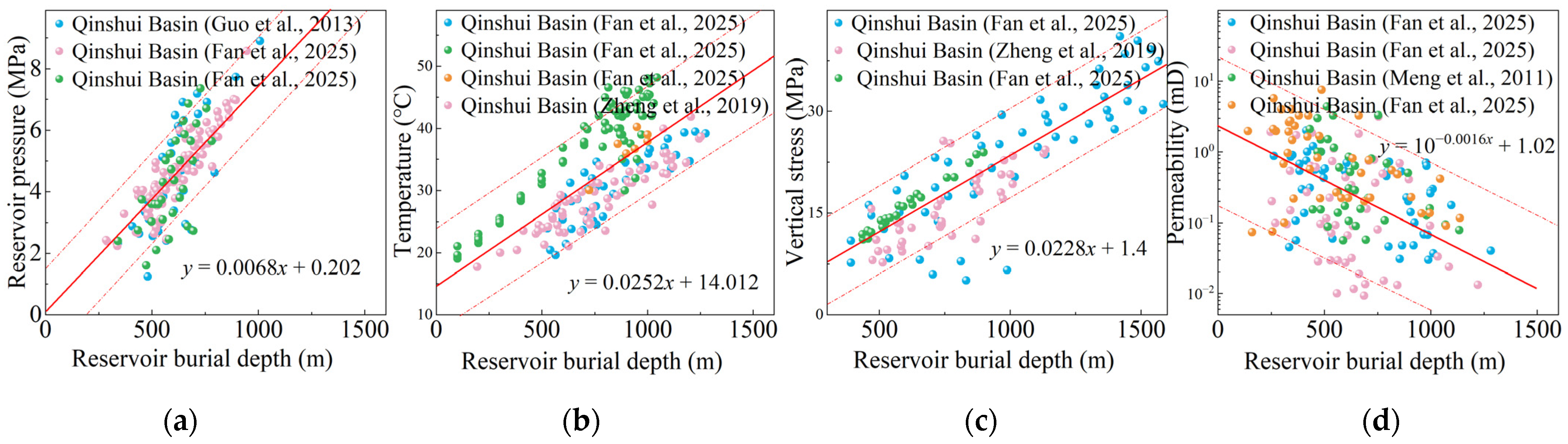

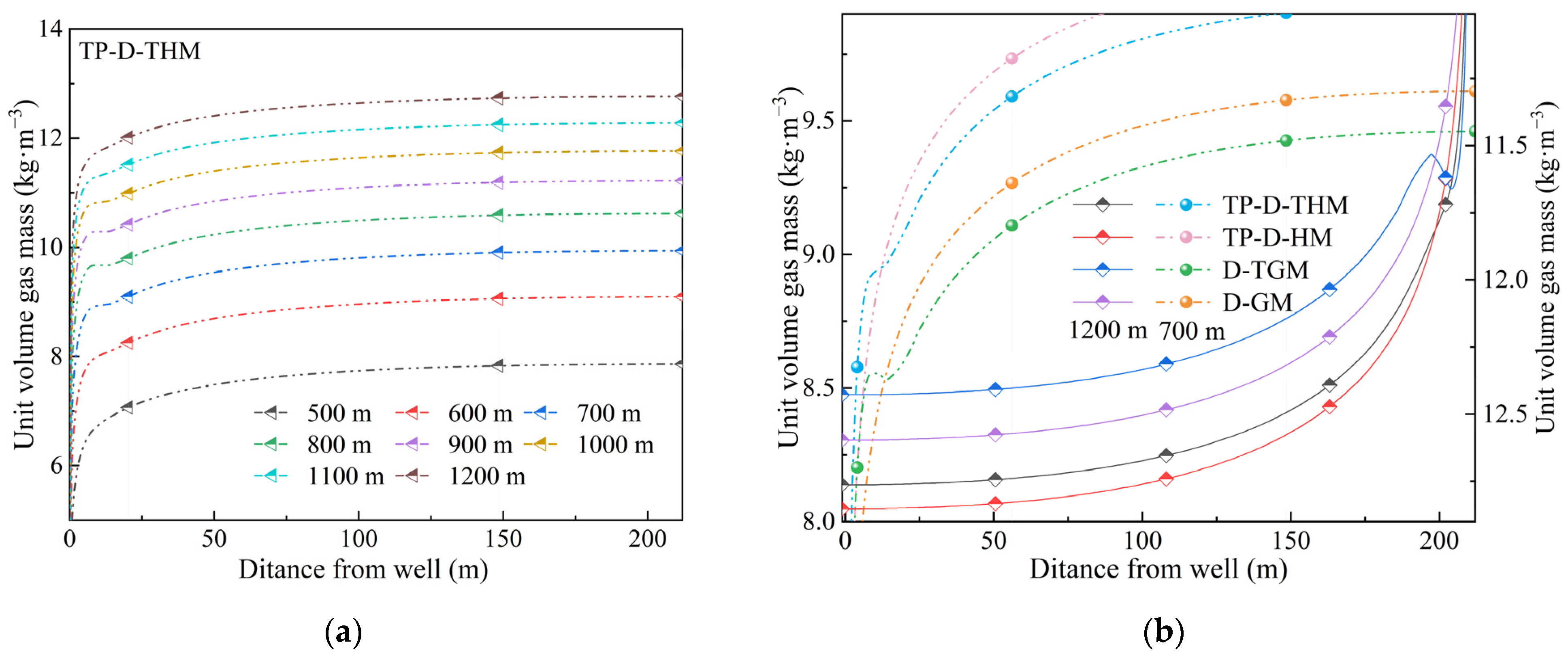

3.1. Reservoir Petrophysical Characteristics Under Varying Burial Depths

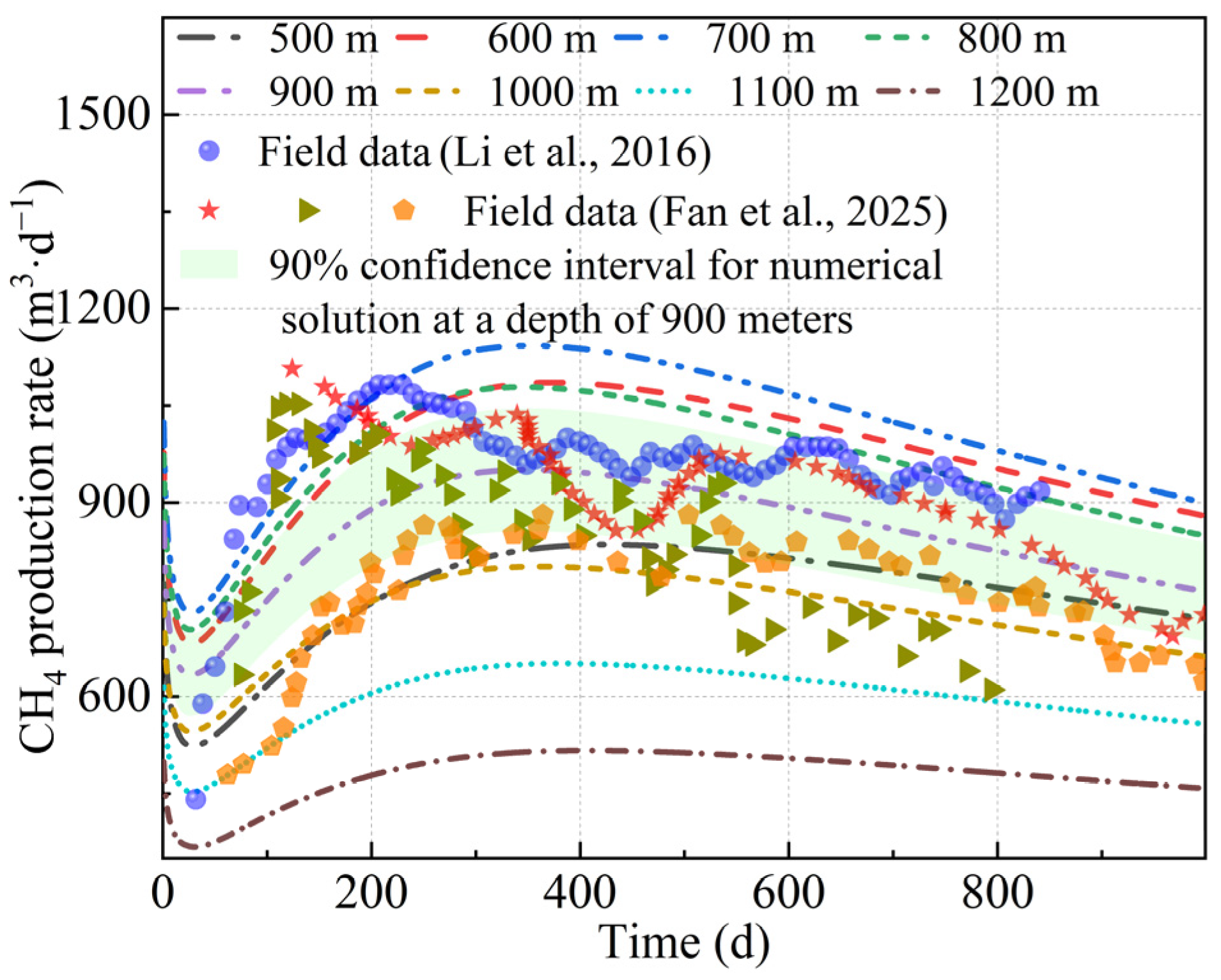

3.2. Numerical Schemes and Model Validation

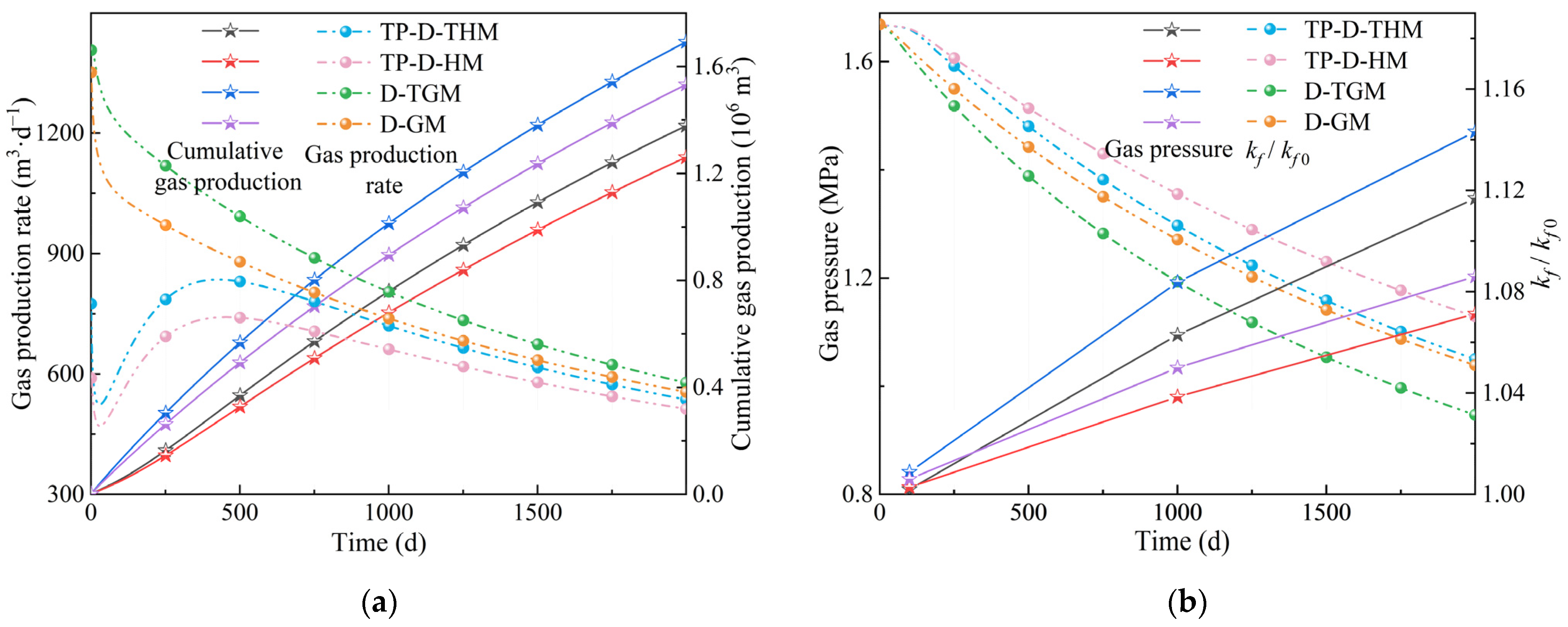

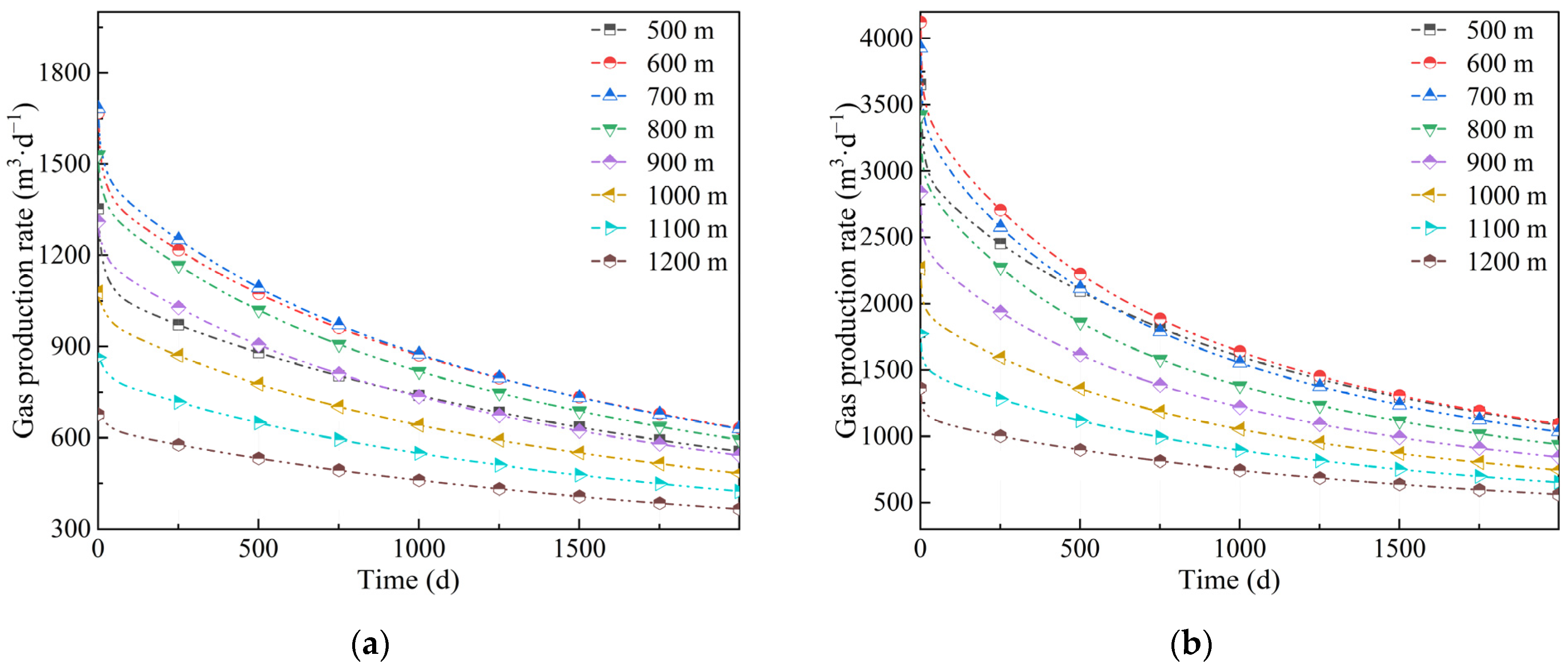

3.3. Effects of Coupling Models on CBM Production

3.4. Effects of Burial Depth on CBM Production

4. Discussion

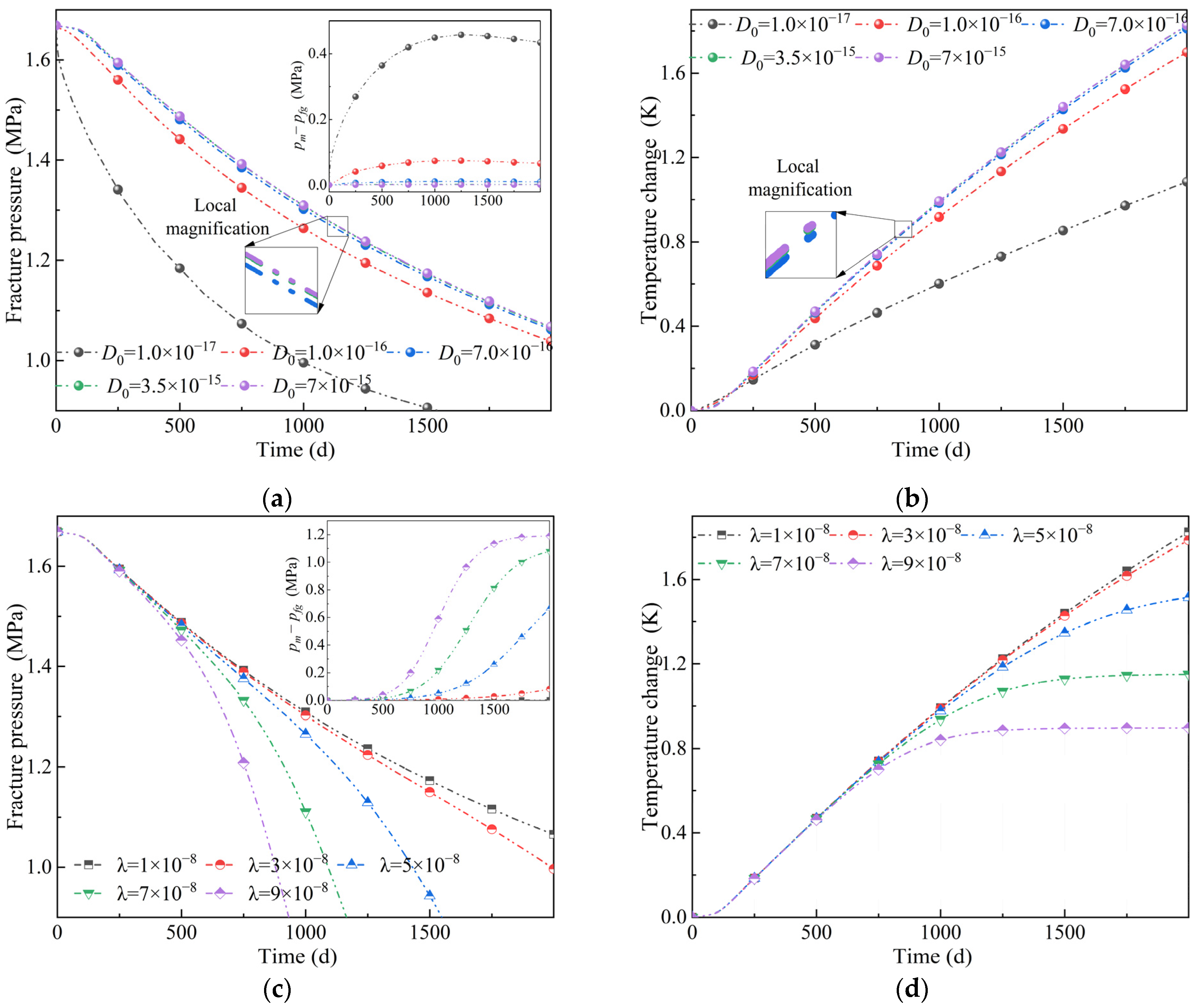

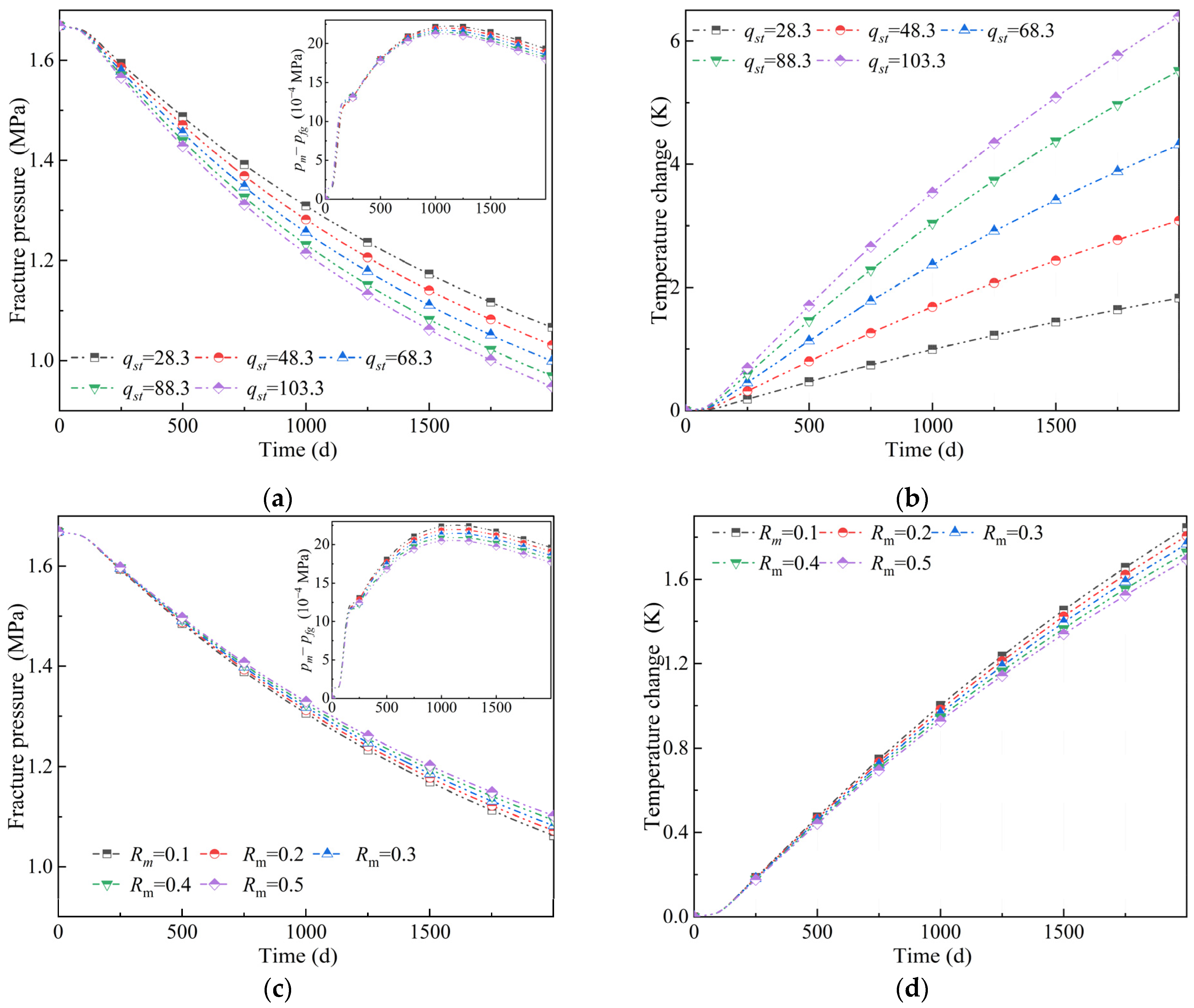

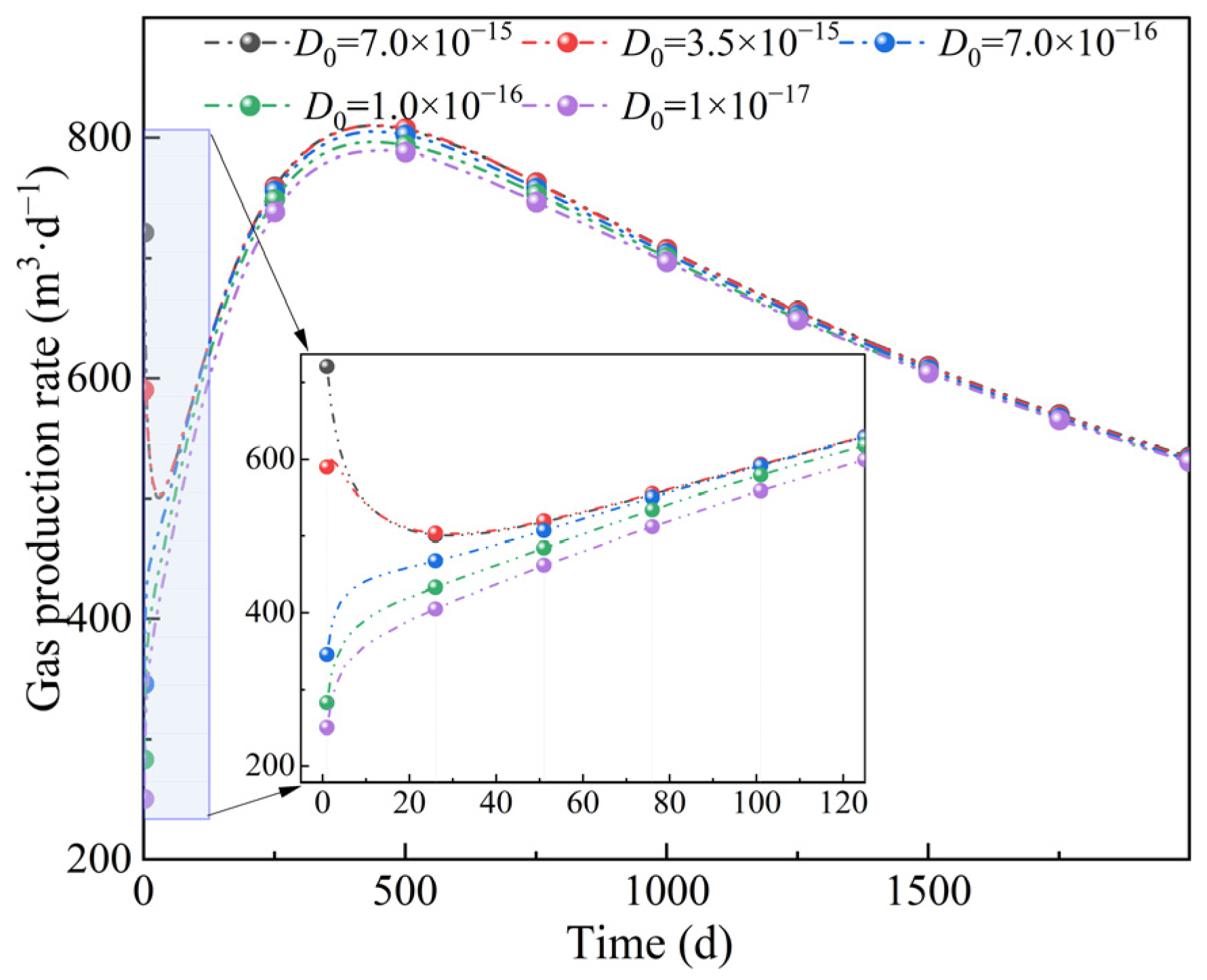

4.1. Sensitivity Analysis

4.2. Production Rate Curve Types

4.3. Existence of a Critical Burial Depth and Its Determination

4.4. Model Reducibility

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Temperature and burial depth do not change the qualitative trend of the production rate. For equilibrium permeability models, incorporating water effects and employing relatively large initial diffusion coefficients can generate a decrease-increase-decrease gas production trend. Using cumulative gas production as the metric, the critical burial depth was determined to be 700 m based on the competing positive and negative effects on coalbed methane recovery. This critical burial depth remains unchanged across different coupling models.

- (2)

- Omitting the temperature field leads to an underestimation of gas production, especially when water effects are also neglected. The underestimation increases gradually with burial depth and tends to plateau beyond 1000 m, with a magnitude of 8.55~16.33%. Conversely, neglecting water effects leads to an overestimation of gas production, particularly when the temperature field is included; the degree of overestimation first decreases and then increases with burial depth, ranging from 19.72% to 28.41%. Overall, water’s inhibitory effect consistently exceeds thermal promotion.

- (3)

- The pressure drop increases with depth and then decreases, peaking at 800 m. Matrix shrinkage driven by gas desorption and cooling dominates fracture compression caused by higher effective stress, so permeability shows an overall increasing trend. The permeability-increase ranking is D-TGM > TP-D-THM > D-GM > TP-D-HM. The temperature reduction value, permeability ratio, and cumulative gas production all exhibit a turning point at 700 m, increasing initially and then decreasing as burial depth increases.

- (4)

- Smaller diffusion coefficients and larger decay rates lead to greater fracture pressure decline and a larger matrix-fracture pressure difference. If the diffusion coefficient falls below 7 × 10−16 m2/s or the decay coefficient exceeds 3 × 10−8 s−1, a pronounced increase ensues in both the fracture pressure drawdown and the matrix-fracture pressure difference. Directly adopting laboratory desorption time overestimates matrix-fracture exchange capacity; simulations indicate that generating a matrix-fracture pressure difference on the order of 0.1 MPa requires hundreds of days. The effects of isosteric adsorption heat on pressure and temperature outweigh those of the modulus degradation rate.

- (5)

- A nondimensional critical-depth criterion integrating reservoir pressure, permeability, and the fractional coverage index is proposed and validated. The critical depth interval for model simplification is identified as 650–1350 m, within which the TP-D-THM model can be simplified to the D-GM model (neglecting water and temperature) for CBM production forecasting, with an error rate below 5%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| initial width of coal matrix | gas molar constant | ||

| width of coal matrix | modulus attenuation rate | ||

| initial fracture aperture | water saturation | ||

| fracture aperture | irreducible water saturation | ||

| Klinkenberg factor | gas saturation | ||

| temperature coefficients of water | residual gas saturation | ||

| temperature coefficients of water | temperature of coal seam | ||

| specific heat capacity of coal skeleton | reference temperature | ||

| specific heat capacity of CH4 | absorbed gas content | ||

| specific heat capacity of water | Langmuir volume constant of CH4 | ||

| pressure coefficient of gas sorption | Biot effective stress coefficient for fracture | ||

| temperature coefficient of gas sorption | Biot effective stress coefficient for matrix | ||

| initial diffusion coefficient | Volumetric adsorption-induced expansion coefficient | ||

| residual diffusion coefficient | coal skeleton’s thermal expansion coefficient | ||

| body force | adsorption strain | ||

| shear modulus | volume strain | ||

| bulk modulus | dynamic viscosity of water | ||

| skeleton bulk modulus | dynamic viscosity of CH4 | ||

| initial permeability of fracture | heat conductivity of coal skeleton | ||

| absolute permeability of the fracture | thermal conductivity of CH4 | ||

| endpoint relative permeability of the gas | conductivity of water | ||

| relative permeability of the gas | effective thermal conductivity of coal mass | ||

| endpoint relative permeability of the water | effective heat convection coefficient | ||

| relative permeability of the water | effective specific heat capacity of coal mass | ||

| molar mass of CH4 | density of CH4 | ||

| Langmuir pressure constant of CH4 | density of CH4 under standard state | ||

| gas pressure in matrix | density of coal skeleton | ||

| fluid pressure in fracture | attenuation coefficient | ||

| gas pressure in fracture | porosity in coal matrix | ||

| water pressure in fracture | initial porosity in coal matrix | ||

| capillary pressure | porosity of fracture | ||

| isosteric heat of gas adsorption | initial porosity of fracture | ||

| effective stress change | matrix width variation caused by temperature | ||

| matrix width changes caused by adsorption | change in crack width | ||

| Acronyms | |||

| THM | Thermo-hydro-mechanical | TP-D-THM | thermo-hydro-mechanical model accounts for gas–water two-phase flow and matrix dynamic diffusion |

| CBM | Coalbed methane | D-GM | gas-mechanical model accounts for matrix dynamic diffusion |

| TP-D-HM | hydro-mechanical model accounts for gas–water two-phase flow and matrix dynamic diffusion | D-GHM | thermo-gas-mechanical accounts for matrix dynamic diffusion |

| Subscript | |||

| 0 | initial value of variable | fracture | |

| matrix | |||

References

- Zhang, Y.; Li, D.; Xin, G.; Jiu, H.; Ren, S. An adsorption micro mechanism theoretical study of CO2-rich industrial waste gas for enhanced unconventional natural gas recovery: Comparison of coalbed methane, shale gas, and tight gas. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 353, 128414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohagheghian, E.; Hassanzadeh, H.; Chen, Z. CO2 sequestration coupled with enhanced gas recovery in shale gas reservoirs. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 34, 646–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basarir, H.; Sun, Y.; Li, G. Gateway stability analysis by global-local modeling approach. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2019, 113, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sang, S.; Zhou, X.; Liu, X. Numerical study on CO2 sequestration in low-permeability coal reservoirs to enhance CH4 recovery: Gas driving water and staged inhibition on CH4 output. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 214, 110478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, N.; Han, C.; Sun, C.; Song, G.; Sun, Y.; Sun, K. Stability Control of Deep Coal Roadway under the Pressure Relief Effect of Adjacent Roadway with Large Deformation: A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 8, 4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Liu, D.; Vandeginste, V.; Cai, Y.; Sun, F. Effects of CO2 injection pressure and confining pressure on CO2-enhanced coalbed methane recovery: Experimental observations at various simulated geological conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483, 149207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rene, N.; Liang, W.; Ali, A.; Butt, I.; Hussain, S. Modeling of thermo-hydro-mechanical coupling in coalbed seam seepage based on impact factor framework. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 055114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, O.; Fişne, A. A Comprehensive Study on Methane Adsorption Capacities and Pore Characteristics of Coal Seams: Implications for Efficient Coalbed Methane Development in the Soma Basin, Turkiye. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 57, 355–6375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Hou, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Ye, M.; Huang, S.; Zhang, H. Seepage Characteristics of 3D Micron Pore-Fracture in Coal and a Permeability Evolution Model Based on Structural Characteristics under CO2 Injection. Nat. Resour. Res. 2023, 32, 2883–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Wang, L.; Naveen, P.; Longinos, S.N.; Hazlett, R.; Ojha, K.; Panigrahi, D.C. Influence of competitive adsorption, diffusion, and dispersion of CH4 and CO2 gases during the CO2-ECBM process. Fuel 2024, 358, 130065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danesh, N.N.; Chen, Z.; Aminossadati, S.M.; Kizil, M.S.; Pan, Z.; Connell, L.D. Impact of creep on the evolution of coal permeability and gas drainage performance. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 469–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedel, T.; Voigt, H. Investigation of non-Darcy flow in tight-gas reservoirs with fractured wells. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2006, 54, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Liu, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Shi, R.; Leong, Y.; Elsworth, D. A critical review of coal permeability models. Fuel 2022, 326, 125124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lin, B.; Liu, T. Thermo-hydro-mechanical couplings controlling gas migration in heterogeneous and elastically-deformed coal. Comput. Geotech. 2020, 123, 103570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Fan, C.; Luo, M.; Wen, H.; Zhou, L.; Zou, Q.; Sun, H.; Wang, D. Permeability-driven optimization of carbon dioxide injection timing in enhanced coalbed methane recovery. Int. J. Coal Sci. Technol. 2025, 12, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, C.R.; Rahmanian, M.; Kantzas, A.; Morad, K. Relative permeability of CBM reservoirs: Controls on curve shape. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2011, 88, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Connell, L.D. Impact of coal seam as interlayer on CO2 storage in saline aquifers: A reservoir simulation study. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2011, 5, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Yu, H.; Xu, W.; Huang, H.; Huang, M.; Meng, S.; Liu, H.; Wu, H. A multi-physics coupled multi-scale transport model for CO2 sequestration and enhanced recovery in shale formation with fractal fracture networks. Energy 2023, 284, 129285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, W.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Han, H.; Cui, P. Modeling Study of Enhanced Coal Seam Gas Extraction via N2 Injection Under Thermal-Hydraulic-Mechanical Interactions. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 39051–39064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Fan, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Liang, S.; Yu, W.; Gao, S.; Guo, W. Non-Darcy thermal-hydraulic-mechanical damage model for enhancing coalbed methane extraction. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2021, 93, 104048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Verma, S.; Bhattacharjee, R.; Upadhyay, R.; Sahu, P. Geological and microstructural characterisation of coal seams for methane drainage from underground coal mines. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2023, 82, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, Q.; Lv, B.; Han, P.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, L. Numerical analysis of equilibrium control in various isothermal adsorption modes: Criteria for effective equilibrium determination. Adsorpt. J. Int. Adsorpt. Soc. 2025, 31, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Qin, Y.; Tang, D.; Shen, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. A comprehensive review of deep coalbed methane and recent developments in China. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2023, 279, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Lin, B.; Liu, T.; Zhao, Y. Modeling and Analysis on Coal Permeability Considering the Mineral Dissolution Caused by Flue Gas in Fractures. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 22848–22863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Li, B.; Ren, C.; Song, H.; Fu, J.; Wu, X. Investigation on damage-permeability model of dual-porosity coal under thermal-mechanical coupling effect. Gas Sci. Eng. 2024, 123, 205229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, M.; Zhao, Z.; Elsworth, D. Why does coal permeability time dependency matter? Fuel 2025, 381, 133373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Zheng, C.; Kizil, M.; Jiang, B.; Wang, Z.; Tang, M.; Chen, Z. Coal permeability models for enhancing performance of clean gas drainage: A review. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 199, 108283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Sheng, J.; Liu, J. A Non-Equilibrium multiphysics model for coal seam gas extraction. Fuel 2023, 331, 125942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Ye, Z. A new triple-porosity multiscale fractal model for gas transport in fractured shale gas reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 78, 103335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Liu, S.; Fan, L.; Blach, T.P.; Sang, G. Unraveling high-pressure gas storage mechanisms in shale nanopores through SANS. Environ. Sci. Nano 2021, 8, 276–2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Fan, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Liang, S.; Yu, W. Optimal injection timing and gas mixture proportion for enhancing coalbed methane recovery. Energy 2021, 222, 119880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Qin, Y.; Fu, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, R. Properties of deep coalbed methane reservoir-forming conditions and critical depth discussion. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2014, 25, 1470–1476. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Aaisal, U.; Farrokhrouz, M.; Akhondzadeh, H.; Iglauer, S.; Keshavarz, A. Experimental investigation on coal fines migration through proppant packs: Assessing variation of formation damage and filtration coefficients. Gas Sci. Eng. 2023, 117, 205073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratama, E.; Ismail, M.S.; Ridha, S. Identification of coal seams suitability for carbon dioxide sequestration with enhanced coalbed methane recovery: A case study in South Sumatera Basin, Indonesia. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2018, 20, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Xu, L.; Elsworth, D.; Luo, M.; Liu, T.; Li, S.; Zhou, L.; Su, W. Spatial-Temporal Evolution and Countermeasures for Coal and Gas Outbursts Represented as a Dynamic System. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2023, 56, 6855–6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Ahn, T.W.; Yoon, H.C.; Lee, J.; Yoon, S.; Moridis, G.J. Validation of strongly coupled geomechanics and gas hydrate reservoir simulation with multiscale laboratory tests. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2022, 149, 104958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yin, Z.Y.; Yan, X. Anisotropic continuum framework of coupled gas flow-adsorption-deformation in sedimentary rocks. Int. J. Numer. Anal. Methods Geomech. 2024, 48, 1018–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Fan, G.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L.; Chai, Y.; Yu, W. Modelling of flue gas injection and collaborative optimization of multi-injection parameters for efficient coal-based carbon sequestration combined with BP neural network parallel genetic algorithms. Fuel 2024, 368, 131536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, K.; Gai, Z. A new mathematical simulation model for gas injection enhanced coalbed methane recovery. Fuel 2016, 183, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, W.; Fu, S.; Ma, J.; Cao, J.; Wang, X.; Niu, B.; Lai, X. Molecular simulation study on the adsorption and storage behavior of CO2 in different matrix components of shale. Mol. Simul. 2024, 50, 1064–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Lin, B.; Fu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, Y.; Yang, W. Modeling coupled gas flow and geomechanics process in stimulated coal seam by hydraulic flushing. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2021, 142, 104769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Elsworth, D.; Pone, D. A dual poroelastic model for CO2-enhanced coalbed methane recovery. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2011, 86, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Elsworth, D.; Miao, X. Evolution of coal permeability from stress-controlled to displacement-controlled swelling conditions. Fuel 2011, 90, 2987–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Fan, G.; Zhang, D.; Han, X.; Ren, C.; Yue, X.; Fan, Y.; Yang, C.; Zhang, S. Depth-responsive mechanisms of carbon sequestration-enhanced gas recovery mechanisms and critical burial depth effects. J. China Coal Soc. 2025, 50, 4033–4053. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Guo, P.; Cheng, Y. Permeability Prediction in Deep Coal Seam: A Case Study on the No. 3 Coal Seam of the Southern Qinshui Basin in China. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 161457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, G.; Sun, B.; Lv, D.; Pan, Z.; Lian, H. Study on Reservoir Properties and Critical Depth in Deep Coal Seams in Qinshui Basin, China. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 1683413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R. In-situ stress, pore pressure and stress-dependent permeability in the Southern Qinshui Basin. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2011, 48, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fan, C.; Han, J.; Luo, M.; Yang, Z.; Bi, H. A fully coupled thermal-hydraulic-mechanical model with two-phase flow for coalbed methane extraction. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 33, 324–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, N.; Wang, J.; Deng, C.; Fan, Y.; Mu, Y.; Wang, T. Numerical study on enhancing coalbed methane recovery by injecting N2/CO2 mixtures and its geological significance. Energy Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 1104–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Elsworth, D.; Li, S.; Chen, Z.; Luo, M.; Song, Y.; Zhang, H. Modelling and optimization of enhanced coalbed methane recovery using CO2/N2 mixtures. Fuel 2019, 253, 1114–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thararoop, P.; Karpyn, Z.T.; Ertekin, T. Development of a multi-mechanistic, dual-porosity, dual-permeability, numerical flow model for coalbed methane reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2012, 8, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Sang, S.; Liu, S. The coupling mechanism of the thermal-hydraulic-mechanical fields in CH4-bearing coal and its application in the CO2-enhanced coalbed methane recovery. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 181, 106177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, E.; Wei, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Liang, Y.; Zou, Q.; Zhu, X. Effect of CO2 injection on Coalbed Permeability Based on a Thermal-Hydraulic-Mechanical Coupling Model. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 11078–11092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DZ/T 0378-2021; Assessment Specification of Coalbed Methane Resources. Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Li, H.; Zhou, G.; Chen, S.; Li, S.; Tang, D. In Situ Gas Content and Extraction Potential of Ultra-Deep Coalbed Methane in the Sichuan Basin, China. Nat. Resour. Res. 2025, 34, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, C.; Hu, J.; Chen, W. Feasibility of enhanced coalbed methane recovery by CO2, sequestration into deep coalbed of Oinshui Basin. J. China Coal Soc. 2016, 41, 156–161. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Basic Assumptions | Key Factors | Reference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal Deformation | Temperature | Water (Present Only in Fractures) | Seepage Field (Darcy’s Law) | Dynamic Diffusion (Fick’s Law) | Dissolved Gases/ Water Vapor | Heterogeneity | Equilibrium Permeability | Non-Equilibrium Permeability | ||

| Single porosity | √ | √ | √ | [11] | ||||||

| Single porosity | √ | √ | √ | √ | [12] | |||||

| Dual porosity | √ | √ | [28] | |||||||

| Dual porosity | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | [5,13,19] | ||

| Dual porosity | √ | √ | √ | [4,17] | ||||||

| Triple porosity | √ | √ | √ | [29] | ||||||

| Triple porosity | √ | √ | √ | √ | [30] | |||||

| Proposed (Double porosity) | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Variable | Value | Unit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coal-seam density; water density | 1470, 1000 | kg·m−3 | [4,13,15] |

| Elastic modulus of bulk coal; elastic modulus of coal skeleton | 2713, 8469 | MPa | [17,18] |

| Dynamic viscosity of CH4; dynamic viscosity of water | 1.03, 1.01 | 10−5 Pa⋅s | [17,18] |

| Residual gas saturation; irreducible (bound) water saturation | 0.05, 0.32 | [20,21] | |

| Gas endpoint relative permeability; water endpoint relative permeability | 1.00, 0.82 | [19,42] | |

| Langmuir volume constant | 0.02 | m3⋅kg−1 | [19,35,42] |

| Langmuir pressure constant | 1.82 | MPa | [26,31,33] |

| Thermal conductivity of CH4 | 0.031 | W/(m⋅K) | [26,48] |

| Thermal conductivity of water; thermal conductivity of coal skeleton | 0.598, 0.191 | W/(m⋅K) | [26,48] |

| Specific heat capacity of water; specific heat capacity of coal skeleton | 4200, 1350 | J/(kg⋅K) | [21,48] |

| Specific heat capacity of CH4 | 2160 | J/(kg⋅K) | [36,48] |

| Equivalent isosteric heat of adsorption of CH4 | 28.3 | kJ⋅mol 1 | [19] |

| Initial diffusion coefficient; residual diffusion coefficient | 3.30, 1.20 | 10−15 m2⋅s−1 | [19,48] |

| Decay coefficient | 1.7 × 10−8 | [19] | |

| Adsorption temperature coefficient; adsorption pressure coefficient | 0.02, 0.07 | K−1, MPa−1 | [12,23,31] |

| Matrix porosity; fracture porosity | 0.04, 0.01 | [16] | |

| Adsorption-strain coefficient | 0.0128 | [16,31] | |

| Volumetric thermal expansion coefficient of the skeleton | 2.4 | 10−5 K−1 | [16] |

| Modulus degradation rate | 0.2 | [31] |

| Coupling Model | Production Well Boundary Conditions | Reservoir Parameters | Reservoir Burial Depth | Number of Simulations | Corresponding Section |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP-D-THM (Model Validation) | References [44,48] | References [44,48] | References [44,48] | 8 | Section 3.2 |

| TP-D-THM | Pressure: 0.15 MPa Water saturation: 0.42 | Fitted value | 500~1200 m | 8 | Section 3.3 |

| TP-D-HM | 8 | ||||

| D-GHM | 8 | ||||

| D-GM | 8 | ||||

| TP-D-THM (Sensitivity Analysis) | Initial diffusion coefficient | 500 m | 5 | Section 4.1 | |

| Diffusion decay rate | 500 m | 5 | |||

| Isosteric heat of adsorption | 500 m | 5 | |||

| Modulus degradation rate | 500~1200 m | 5 | |||

| TP-D-THM (Critical-Depth Validation) | References [32,47] | 500~1200 m | 8 | Section 4.3 |

| Reservoir Location | Pressure/MPa | Temperature/K | Permeability/mD | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Fan Zhuang Block No. 1 Coalbed Methane Well | 5.2 | 312.5 | 0.50 | [48] |

| Hancheng Mining Area W7 Well | 5.2 | 300.0 | 0.50 | [44] |

| South Shizhuang Block IW Well | 4.3 | 296.0 | 1.00 | [44] |

| Zheng Zhuang Block Zheng San Well Area | 7.2 | 302.5 | 0.15 | [44] |

| TP-D-THM | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burial Depth (m) | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | 1100 | 1200 |

| Peak Gas Production Rate (m3/d) | 835.11 | 1085.50 | 1142.60 | 1078.50 | 950.62 | 801.06 | 651.17 | 516.70 |

| Time (d) | 424 | 379 | 358 | 349 | 350 | 360 | 381 | 407 |

| TP-D-HM | ||||||||

| Burial Depth (m) | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | 1100 | 1200 |

| Peak Gas Production Rate (m3/d) | 741.61 | 930.31 | 956.09 | 886.46 | 775.04 | 651.28 | 531.10 | 423.25 |

| Time (d) | 449 | 404 | 379 | 373 | 374 | 376 | 404 | 428 |

| D-TGM | ||||||||

| Burial Depth (m) | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | 1100 | 1200 |

| Peak Gas Production Rate (m3/d) | 1417.64 | 1811.56 | 1878.80 | 1755.18 | 1536.58 | 1288.03 | 1046.29 | 829.43 |

| Time (d) | 3 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| D-GM | ||||||||

| Burial Depth (m) | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 | 1000 | 1100 | 1200 |

| Peak Gas Production Rate (m3/d) | 1351.03 | 1665.75 | 1678.09 | 1525.85 | 1305.71 | 1073.74 | 858.75 | 673.40 |

| Time (d) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, Z.; Fan, G.; Zhang, D.; Luo, T.; Han, X.; Xu, G.; Tong, H. Mechanism of Burial Depth Effect on Recovery Under Different Coupling Models: Response and Simplification. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11657. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111657

Fan Z, Fan G, Zhang D, Luo T, Han X, Xu G, Tong H. Mechanism of Burial Depth Effect on Recovery Under Different Coupling Models: Response and Simplification. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(21):11657. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111657

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Zhanglei, Gangwei Fan, Dongsheng Zhang, Tao Luo, Xuesen Han, Guangzheng Xu, and Haochen Tong. 2025. "Mechanism of Burial Depth Effect on Recovery Under Different Coupling Models: Response and Simplification" Applied Sciences 15, no. 21: 11657. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111657

APA StyleFan, Z., Fan, G., Zhang, D., Luo, T., Han, X., Xu, G., & Tong, H. (2025). Mechanism of Burial Depth Effect on Recovery Under Different Coupling Models: Response and Simplification. Applied Sciences, 15(21), 11657. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152111657