An Analysis of Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Climate on the Supportive Leadership–Employee Wellbeing Linkage in the Lebanese Academic Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Hypotheses and Theories

2.1. Theoretical Setting

2.2. Supportive Leadership and Employees’ Wellbeing

2.3. Mediating Role of Organizational Climate

2.4. Moderating Role of Perceived Organizational Support

3. Research Design

3.1. Methodology and Approach

3.2. Measurements

3.3. Sample Characteristics

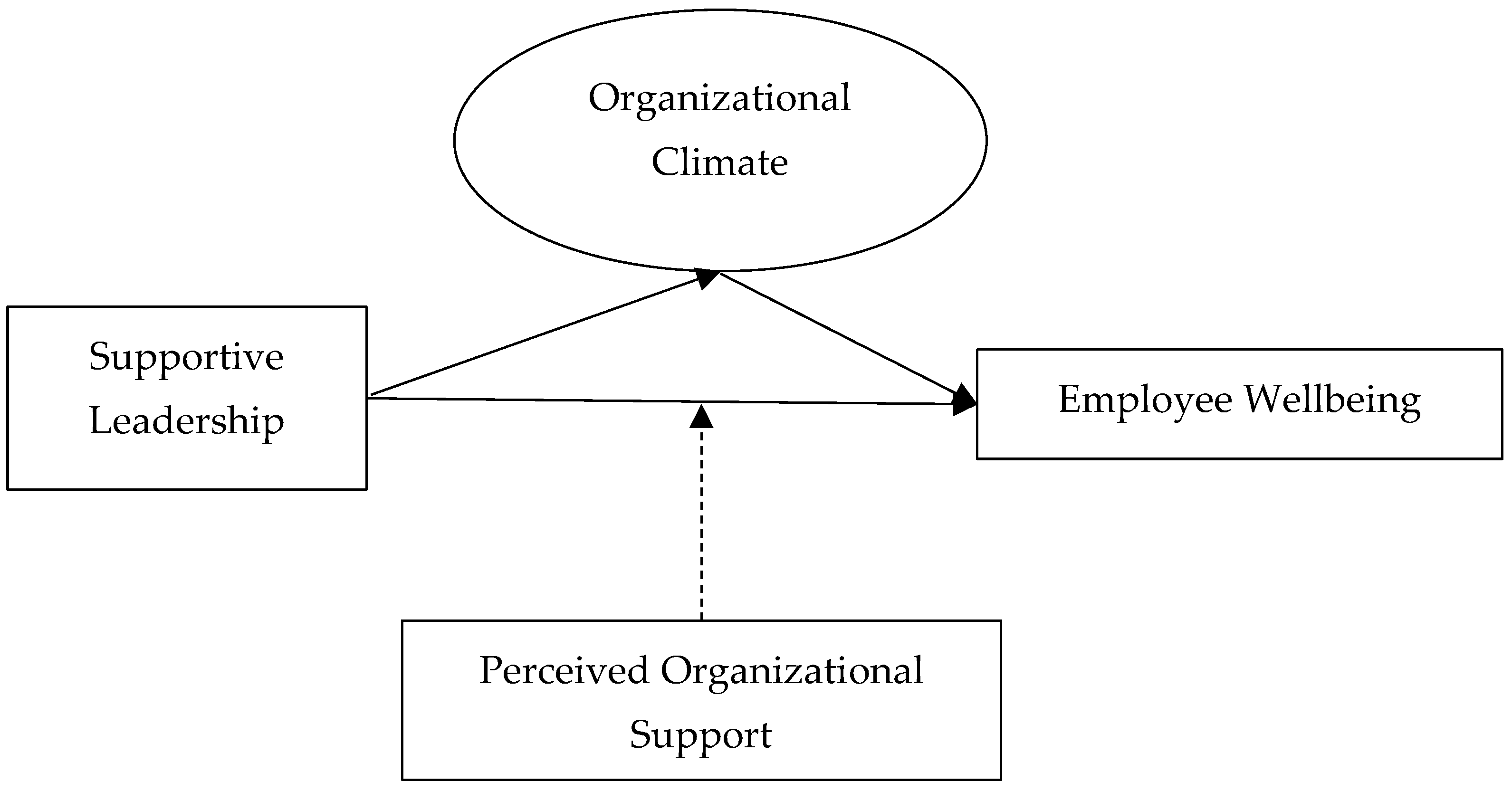

3.4. Research Model

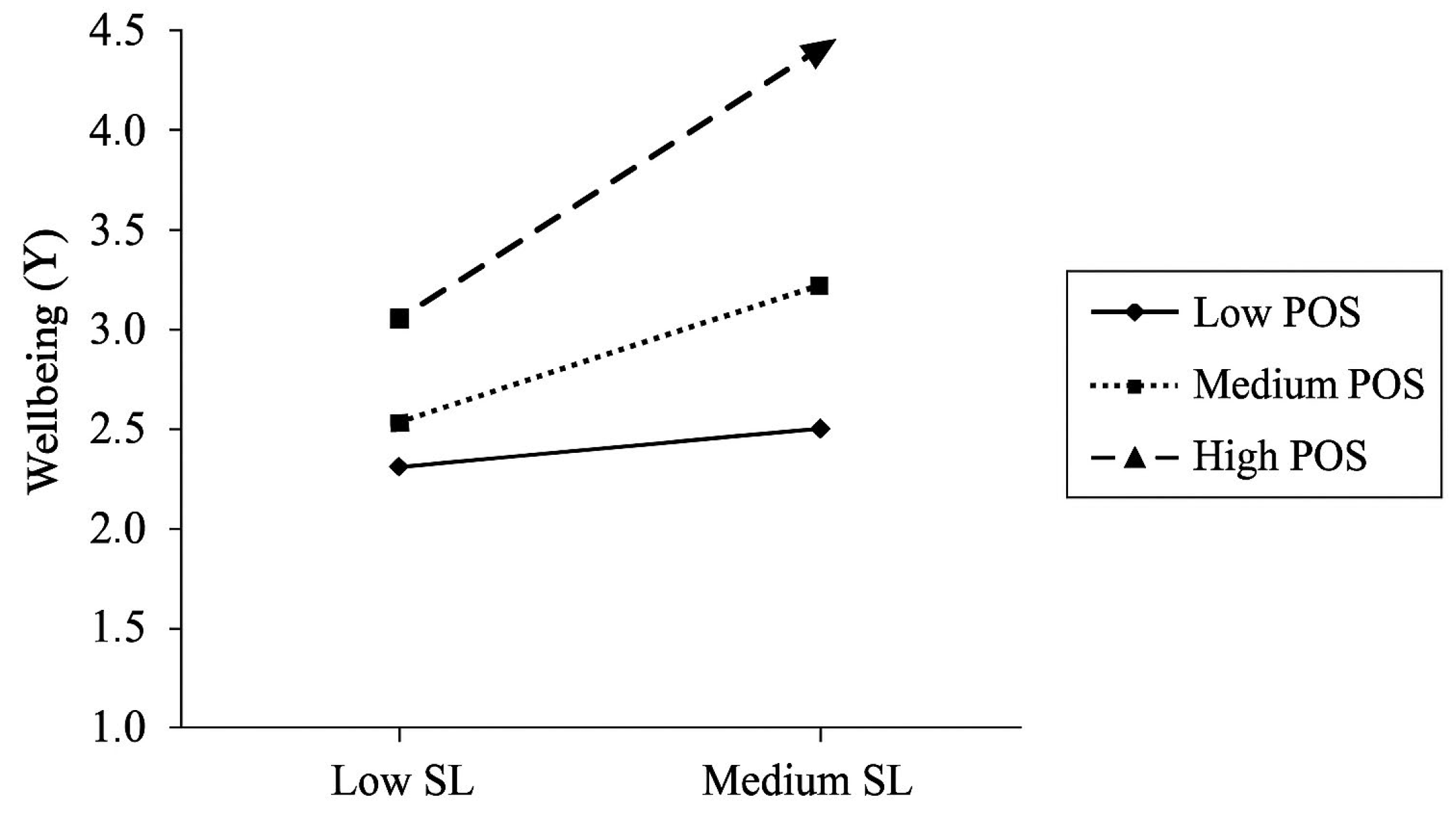

4. Findings

Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdelwahed, N. A. A., & Doghan, M. A. A. (2023). Developing employee productivity and performance through work engagement and organizational factors in an educational society. Societies, 13(3), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolnasser, M. S. A., Abdou, A. H., Hassan, T. H., & Salem, A. E. (2023). Transformational leadership, employee engagement, job satisfaction, and psychological well-being among hotel employees after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic: A serial mediation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, R., Nawaz, M. R., Ishaq, M. I., Khan, M. M., & Ashraf, H. A. (2023). Social exchange theory: Systematic review and future directions. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1015921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S. F., Alam, M. M., Rahmat, M. K., Mubarik, M. S., & Hyder, S. I. (2022). Academic and administrative role of artificial intelligence in education. Sustainability, 14(3), 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Hadrawi, R. H., Alasady, A. A. A., & Alkaseer, N. A. (2023). The role of supportive leadership practices in addressing electronic management obstacles—An analytical study at Al-Furat Al-Awsat Technical University-Republic of Iraq. International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(7), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arar, K. (2020). Educational administration in the Middle East. In Oxford research encyclopedia of education. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arar, K., & Oplatka, I. (2022). Advanced theories of educational leadership. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Asghar, M. Z., Barbera, E., Rasool, S. F., Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., & Mohelská, H. (2022). Adoption of social media-based knowledge-sharing behaviour and authentic leadership development: Evidence from the educational sector of Pakistan during COVID-19. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(1), 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen, T. (2024). A study on Lebanon’s competitive knowledge-based economy, relative strengths, and shortcomings. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 15, 15390–15417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bray, M., & Hajar, A. (2023). Shadow education in the Middle East: Private supplementary tutoring and its policy implications (p. 122). Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Caesens, G., Stinglhamber, F., & Ohana, M. (2021). Perceived organizational support and well-being: A weekly study. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 36(1), 1214–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canli, S., & Özdemir, Y. (2022). The impact of organizational climate on organizational creativity in educational institutions. i.e.: Inquiry in Education, 14(1), 6. [Google Scholar]

- Canto, J. M., & Vallejo-Martín, M. (2021). The effects of social identity and emotional connection on subjective well-being in times of the COVID-19 pandemic for a Spanish sample. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casula, M., Rangarajan, N., & Shields, P. (2021). The potential of working hypotheses for deductive exploratory re-search. Quality & Quantity, 55(5), 1703–1725. [Google Scholar]

- Chami-Malaeb, R., Menhem, N., & Abdulkhalek, R. (2024). Higher education leadership, quality of worklife and turnover intention among Lebanese academics in COVID-19: A moderated mediation model. European Journal of Training and Development, 48(5/6), 625–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., Zhang, L., Lin, Y., Guo, H., & Zhang, S. (2022). Enhancing employee wellbeing by ethical leadership in the construction industry: The role of perceived organizational support. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 935557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtin, M., Richards, H. L., & Fortune, D. G. (2022). Resilience among health care workers while working during a pandemic: A systematic review and meta synthesis of qualitative studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 95, 102173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., Huntington, R., Hutchison, S., & Sowa, D. (1986). Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R., Malone, G. P., & Presson, W. D. (2016). Optimizing perceived organizational support to enhance employee engagement. Society for Human Resource Management and Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Farid, T., Iqbal, S., Saeed, I., Irfan, S., & Akhtar, T. (2021). Impact of supportive leadership during COVID-19 on nurses’ well-being: The mediating role of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 695091. [Google Scholar]

- García-Cabrera, A. M., & García-Soto, M. G. (2021). Organizational climate as a mediator between transformational leadership and employee performance. European Management Journal, 39(2), 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y., & Wang, L. (2023). Teacher professional identity, work engagement, and emotion influence: How do they affect teachers’ career satisfaction. International Journal of Education, Science, Technology, and Engineering (IJESTE), 6(2), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, L. M., Porck, J. P., Walter, S. L., Scrimpshire, A. J., & Zabinski, A. M. (2022). A meta-analytic review of identification at work: Relative contribution of team, organizational, and professional identification. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(5), 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Gudergan, S. P. (2017). Advanced issues in partial least squares structural equation modeling. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, S. T., Perez, A. L., Lester, P. B., & Quick, J. C. (2020). Bolstering workplace psychological well-being through transactional and transformational leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 27(3), 222–240. [Google Scholar]

- Hayat, A., & Afshari, L. (2021). Supportive organizational climate: A moderated mediation model of workplace bullying and employee well-being. Personnel Review, 50(7/8), 1685–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based struc-tural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sinkovics, R. R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, H. C., & Chan, Y. C. (2022). Flourishing in the workplace: A one-year prospective study on the effects of perceived organizational support and psychological capital. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(2), 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horoub, I., & Zargar, P. (2022). Empowering leadership and job satisfaction of academic staff in Palestinian universities: Implications of leader-member exchange and trust in leader. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1065545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, S., Abid, G., & Ashfaq, F. (2023). The impact of perceived organizational support on professional commitment: A moderation of burnout and mediation of well-being. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 43(7/8), 710–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, R., & Anis-ul-Haque, M. (2011). Mediating effect of organizational climate between transformational leadership and innovative work behaviour. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 26, 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, K., Zhu, T., Zhang, W., Rasool, S. F., Asghar, A., & Chin, T. (2022). The linkage between ethical leadership, well-being, work engagement, and innovative work behavior: The empirical evidence from the higher education sector of China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z., & Probst, T. M. (2021). The mediating effect of organizational climate on the relationship between leadership and employee outcomes: A cross-cultural study. International Journal of Stress Management, 28(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1971). Simultaneous factor analysis in several populations. Psychometrika, 36(4), 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelloway, E. K., Turner, N., Barling, J., & Loughlin, C. (2012). Transformational leadership and employee psychological well-being: The mediating role of employee trust in leadership. Work & Stress, 26(1), 39–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kelloway, E. K., Weigand, H., Mckee, M. C., & Das, H. (2013). Positive leadership and employee well-being. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20(1), 107–117. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R. N. A., Masih, S., & Ali, W. (2021). Influence of transactional leadership and trust in leader on employee well-being and mediating role of organizational climate. International Journal of Business and Economic Affairs, 6(1), 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Krug, H., Haslam, S. A., Otto, K., & Steffens, N. K. (2021). Identity leadership, social identity continuity, and well-being at work during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 684475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J., Chu, H., & Yang, K. (2021). Roles and research trends of artificial intelligence in higher education: A systematic review of the top 50 most-cited articles. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 38(3), 22–42. [Google Scholar]

- Makwetta, J. J., Deli, Y., Sarpong, F. A., Sekei, V. S., Khan, K. Z., & Meena, M. E. (2021). Effects of empowering leadership on employee voice behavior: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Sciences, 10(4), 125–133. [Google Scholar]

- Malaeb, M., Dagher, G. K., & Canaan Messarra, L. (2023). The relationship between self-leadership and employee engagement in Lebanon and the UAE: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. Personnel Review, 52(9), 2284–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2022). The burnout challenge: Managing people’s relationships with their jobs. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Montano, D., Reeske, A., Franke, F., & Hüffmeier, J. (2017). Leadership, followers’ mental health and job performance in organizations: A comprehensive meta-analysis from an occupational health perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(3), 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D., Schleu, J. E., & Hüffmeier, J. (2023). A meta-analysis of the relative contribution of leadership styles to followers’ mental health. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 30(1), 90–107. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2009). Age, work experience, and the psychological contract. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(8), 1053–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinihuhta, M., & Häggman-Laitila, A. (2022). A systematic review of the relationships between nurse leaders’ leadership styles and nurses’ work-related well-being. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 28(5), e13040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C. P., Baltes, B. B., Young, S. A., Huff, J. W., Altmann, R. A., Lacost, H. A., & Roberts, J. E. (2003). Relationships between psychological climate perceptions and work outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(4), 389–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattali, S., Sankar, J. P., Al Qahtani, H., Menon, N., & Faizal, S. (2024). Effect of leadership styles on turnover intention among staff nurses in private hospitals: The moderating effect of perceived organizational support. BMC Health Services Research, 24(1), 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelled, L. H., Eisenhardt, K. M., & Xin, K. R. (1999). Exploring the black box: An analysis of work group diversity, conflict and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmad, Y. E. (2022). Psychological Leadership Theory. Journal of Leadership Studies, 15(2), 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Rajashekar, S., & Jain, A. (2024). A thematic analysis on “employee engagement in IT companies from the perspective of holistic well-being initiatives”. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 36(2), 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, S. F., Wang, M., Tang, M., Saeed, A., & Iqbal, J. (2021). How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: The mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, G. E. (2010). Servant leader workplace spiritual intelligence: A preliminary analysis. Journal of Strategic Leadership, 3(1), 52–69. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, C. W., Breevaart, K., & Zacher, H. (2022). Disentangling between-person and reciprocal within-person relations among perceived leadership and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(4), 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, P., Van den Broeck, A., Schreurs, B., Proost, K., & Germeys, F. (2022). Autonomy supportive and controlling leadership as antecedents of work design and employee well-being. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 25(1), 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar, H., Ishaq, M. I., Amin, A., & Ahmed, R. (2020). Ethical leadership, work engagement, employees’ well-being, and performance: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 2008–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B., Ehrhart, M. G., & Macey, W. H. (2013). Organizational climate and culture. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanock, L. R., & Eisenberger, R. (2006). When supervisors feel supported: Relationships with subordinates’ perceived supervisor support, perceived organizational support, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoss, M. K., Jiang, L., & Probst, T. M. (2021). Bending without breaking: A two-study examination of employee resilience in the face of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(2), 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, M., Schümann, M., Teetzen, F., Gregersen, S., Begemann, V., & Vincent-Höper, S. (2021). Supportive leadership training effects on employee social and hedonic well-being: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(6), 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Viitala, R., Tanskanen, J., & Säntti, R. (2015). The connection between organizational climate and well-being at work. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 23(4), 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuecheng, W., Ahmad, N. H., Iqbal, Q., & Saina, B. (2022). Responsible leadership and sustainable development in east asia economic group: Application of social exchange theory. Sustainability, 14(10), 6020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeb, A., Goh, G. G. G., Javaid, M., Khan, M. N., Khan, A. U., & Gul, S. (2023). The interplay between supervisor support and job performance: Implications of social exchange and social learning theories. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 15(2), 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Guo, Y., Zhang, M., Xu, S., Liu, X., & Newman, A. (2022). Antecedents and outcomes of authentic leadership across culture: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 39(4), 1399–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Liu, D., & Wang, J. (2021). How organizational climate mediates the relationship between leadership and employee well-being: A meta-analytic path analysis. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar, D., & Hofmann, D. A. (2012). Organizational culture and climate. In S. W. J. Kozlowski (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of organizational psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 643–666). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Age | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 25–30 | 46 | 32.62% |

| 31–36 | 45 | 31.92% |

| 37–45 | 34 | 24.12% |

| +45 | 16 | 11.34% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 68 | 48.22% |

| Female | 73 | 51.78% |

| Work Experience | ||

| <1 year | 46 | 32.62% |

| 1–4 years | 68 | 48.23% |

| +4 years | 27 | 19.15% |

| Construct | Dimensions | Indicator | Outer Loadings | α | Rho A | CR | AVE | VIF | Weights | t-Stat. | CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supportive Leadership α = 0.811 CV = 0.708 | Emotional | EM1 | 0.722 | 0.804 | 0.811 | 0.802 | 0.662 | 1.845 | 0.369 | 2.309 ** | 0.713 |

| EM2 | 0.797 | 0.411 | 2.220 ** | ||||||||

| EM3 | 0.774 | 0.366 | 2.188 ** | ||||||||

| Instrumental | IN1 | 0.840 | 0.775 | 0.785 | 0.744 | 0.721 | 1.741 | 0.376 | 2.112 * | 0.726 | |

| IN2 | 0.824 | 0.381 | 2.301 ** | ||||||||

| IN3 | 0.811 | 0.374 | 2.345 * | ||||||||

| Appreciative | AP1 | 0.821 | 0.742 | 0.745 | 0.719 | 0.715 | 2.348 | 0.523 | 3.308 ** | 0.730 | |

| AP2 | 0.749 | 0.440 | 2.304 * | ||||||||

| AP3 | 0.813 | 0.376 | 2.121 * | ||||||||

| Employee Wellbeing α = 0.802 CV = 0.711 | Emotional | EW1 | 0.841 | 0.834 | 0.867 | 0.808 | 0.748 | 1.864 | 0.413 | 2.431 * | 0.729 |

| EW2 | 0.815 | 0.446 | 2.235 * | ||||||||

| EW3 | 0.809 | 0.432 | 2.380 * | ||||||||

| Psychological | PS1 | 0.867 | 0.782 | 0.761 | 0.771 | 0.737 | 1.877 | 0.502 | 2.610 * | 0.711 | |

| PS2 | 0.725 | 0.389 | 2.546 * | ||||||||

| PS3 | 0.770 | 0.432 | 2.726 * | ||||||||

| Social | SW1 | 0.791 | 0.785 | 0.809 | 0.738 | 0.725 | 1.944 | 0.384 | 2.688 * | 0.733 | |

| SW2 | 0.788 | 0.361 | 2.764 * | ||||||||

| SW3 | 0.779 | 0.377 | 2.620 * | ||||||||

| Perceived Organizational Support | - | POS1 | 0.844 | 0.855 | 0.881 | 0.832 | 0.545 | - | |||

| POS2 | 0.826 | ||||||||||

| POS3 | 0.817 | ||||||||||

| Organizational Climate α = 0.796 CV = 0.726 | Leader Support | LS1 | 0.713 | 0.773 | 0.814 | 0.765 | 0.624 | 1.870 | 0.409 | 2.451 * | 0.721 |

| LS2 | 0.745 | 0.419 | 2.266 * | ||||||||

| LS3 | 0.721 | 0.413 | 2.73 * | ||||||||

| Role Clarity | RC1 | 0.719 | 0.801 | 0.833 | 0.841 | 0.708 | 1.921 | 0.349 | 2.135 * | 0.749 | |

| RC2 | 0.733 | 0.401 | 2.440 * | ||||||||

| RC3 | 0.729 | 0.367 | 2.391 ** | ||||||||

| Reward and Recognition | RR1 | 0.779 | 0.748 | 0.739 | 0.781 | 0.724 | 1.936 | 0.413 | 2.345 * | 0.739 | |

| RR2 | 0.815 | 0.415 | 2.301 * | ||||||||

| RR3 | 0.774 | 0.411 | 2.411 * | ||||||||

| EM | IN | AP | EW | PS | SW | POS | LS | RC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM | - | ||||||||

| IN | 0.711 | - | |||||||

| AP | 0.444 | 0.522 | - | ||||||

| EW | 0.722 | 0.604 | 0.723 | - | |||||

| PS | 0.631 | 0.637 | 0.621 | 0.645 | - | ||||

| SW | 0.607 | 0.609 | 0.644 | 0.634 | 0.705 | - | |||

| POS | 0.637 | 0.497 | 0.661 | 0.594 | 0.679 | 0.680 | - | ||

| LS | 0.519 | 0.537 | 0.608 | 0.581 | 0.544 | 0.671 | 0.677 | - | |

| RC | 0.607 | 0.610 | 0.577 | 0.613 | 0.598 | 0.479 | 0.616 | 0.620 | - |

| RR | 0.577 | 0.549 | 0.611 | 0.603 | 0.634 | 0.629 | 0.626 | 0.673 | 0.709 |

| Effects | Relations | β | t-Statistics | Ƒ2 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | |||||

| H1 | SL → EW | 0.318 | 4.918 *** | 0.134 | Supported |

| Mediation | |||||

| H2 | SL → OC → EW | 0.188 | 2.833 ** | 0.038 | Supported |

| Moderation | |||||

| H3 | SL*POS → EW | 0.183 | 2.716 ** | 0.037 | Supported |

| Control Variables | Age → EW | 0.120 | 2.021 * | ||

| Gender → EW | 0.123 | 2.203 * | |||

| Experience → EW | 0.119 | 2.177 * | |||

| R2IP = 0.44/Q2IP = 0.24 R2GI = 0.51/Q2GI = 0.27 SRMR: 0.023; NFI: 0.921 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassanein, F.R.; Daouk, A.; Bou Zakhem, N.; ElSayed, R.A.; Tahan, S.; Houmani, H.; Al Dilby, H.K. An Analysis of Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Climate on the Supportive Leadership–Employee Wellbeing Linkage in the Lebanese Academic Sector. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060204

Hassanein FR, Daouk A, Bou Zakhem N, ElSayed RA, Tahan S, Houmani H, Al Dilby HK. An Analysis of Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Climate on the Supportive Leadership–Employee Wellbeing Linkage in the Lebanese Academic Sector. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):204. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060204

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassanein, Fida Ragheb, Amira Daouk, Najib Bou Zakhem, Ranim Ahmad ElSayed, Suha Tahan, Hassan Houmani, and Hala Koleilat Al Dilby. 2025. "An Analysis of Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Climate on the Supportive Leadership–Employee Wellbeing Linkage in the Lebanese Academic Sector" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060204

APA StyleHassanein, F. R., Daouk, A., Bou Zakhem, N., ElSayed, R. A., Tahan, S., Houmani, H., & Al Dilby, H. K. (2025). An Analysis of Perceived Organizational Support and Organizational Climate on the Supportive Leadership–Employee Wellbeing Linkage in the Lebanese Academic Sector. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 204. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060204