1. Introduction

Information literacy (IL), recognized as a paramount and transformative force in education (

Bruce, 2004;

Majid et al., 2020;

Naveed et al., 2023a), equips individuals with the ability to identify their information needs, locate, assess, and ethically apply pertinent information to specific situations (

Association of College and Research Libraries, 2000;

Foo et al., 2017;

Shipman et al., 2009). IL refers to a meta-literacy that involves a range of skills, including information seeking, retrieval, evaluation, management, reuse, and communication, regardless of the information’s genre or medium (

Machin-Mastromatteo, 2021). It empowers individuals with the capacity for critical thinking, informed perspectives, and well-balanced judgments regarding the information they encounter and utilize, fostering comprehensive societal engagement (

Charted Institute of Library & Information Professionals, 2018). The enhancement of students’ proficiency in handling information-related tasks, optimizing information utilization, and adopting appropriate information behaviors is boosted by their IL levels (

Naveed & Mahmood, 2022). IL not only improves students’ academic involvement and performance (

Banik & Kumar, 2019;

Jones & Mastrorilli, 2022;

Mughari et al., 2023) but also contributes to the development of students as lifelong learners and creative professionals (

Naveed et al., 2023b;

Naveed & Mahmood, 2019;

Saadia & Naveed, 2024).

The dynamic nature of modern enterprises calls for a workforce that must stay abreast of recent technological advancements to solve business problems innovatively (

London, 2011) and maintain a sustainable competitive advantage (

Kesici, 2022). Consequently, students are urged to foster skills for lifelong learning—an autonomous, voluntary, and continuous pursuit of knowledge to keep pace with technological developments and enhance organizational performance and effectiveness (

Coşkun & Demirel, 2010;

Dweck, 2016;

Naveed et al., 2023a,

2023b). In the context of entrepreneurship, IL is crucial for decision-making and problem-solving, as entrepreneurs often need to stay updated on market trends, technological advancements, and competitive information (

Syam et al., 2021). The entrepreneurial process involves environmental scanning for opportunities, assessing risks, and making strategic decisions that require extensive research and gathering of credible information (

Cardella et al., 2020;

Pascucci et al., 2024;

Pryor et al., 2016). IL not only equips entrepreneurs with the critical thinking and analytical skills needed to navigate the complexities of entrepreneurship (e.g., finding credible information, staying informed, making balanced judgments, etc.) but also enables them to stay updated and make informed decisions and contributes to shaping a positive entrepreneurial intention (

Syam et al., 2021) and the development of entrepreneurial skills (

Korani, 2022;

Mohammadinejad & Tirgar, 2023).

Information-literate entrepreneurs may feel more confident and prepared to embark on entrepreneurial ventures (

Bahrami & Jafariharandi, 2020;

Keshavarz, 2021). On the other hand, the increasing engagement in entrepreneurial activities can also enhance and intensify levels of IL. Thus, the nature of the relationship between IL, entrepreneurial intention, and skills is symbiotic, with each reinforcing and complementing the other. The practical application of IL skills in real-world business scenarios not only can deepen one’s understanding and proficiency but also may serve as a crucial groundwork for gaining and employing the skills essential for success in entrepreneurship. Determining the factors influencing entrepreneurial intention and skills has always been crucial for those involved in entrepreneurial education, aiming to bolster the potential for successful startup ventures (

Al-Qadasi et al., 2024;

Hou et al., 2023;

Kurjono et al., 2023). Launching a business relies heavily on information utilization, demanding the capability to efficiently locate, assess, and apply information (

Pryor et al., 2016). Therefore, it is alleged that IL should positively influence entrepreneurial intention and skills. In comparison, some studies have explored the relationship between IL and entrepreneurial intention (

Syam et al., 2021) and entrepreneurial skills (

Korani, 2022;

Mohammadinejad & Tirgar, 2023).

Evidence regarding the interconnectedness of IL, entrepreneurial intention, and skills remains limited. Moreover, research specifically examining the association between IL, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills among business students is scarce, with no studies appearing to address this area directly. Therefore, this study intends to examine the influence of IL on entrepreneurial intention and skills among business students in the District of Sargodha, Pakistan. A deeper understanding of these interrelationships may not only enhance recognition of the effectiveness of IL in business education but also inform policy and practice for business and entrepreneurial education. Specifically, examining the interplay between IL, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills offers pragmatic insights into the IL significance for business education, thereby enabling educators and policymakers to design more effective curricula for fostering entrepreneurial endeavors. The present research seeks to address the following research questions (RQ):

- RQ 1:

What is the nature of the association between information literacy, entrepreneurial intentions, and skills?

- RQ 2:

How does information literacy influence entrepreneurial intentions among business students?

- RQ 3:

How does information literacy influence entrepreneurial skills among business students?

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

There is a sizable body of research addressing IL in various ways and contexts (e.g., academia, workplace, health, and everyday life) both nationally and internationally (e.g.,

Atikuzzaman et al., 2025;

Naveed et al., 2023a,

2023b). Some studies appear to have been conducted to assess IL skills among business students (e.g.,

Naveed & Mahmood, 2019,

2022). The following paragraphs review the related literature, specifically focusing on the interrelationships between IL, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills.

2.1. Information Literacy and Entreprenurial Intentions

Entrepreneurial intention refers to one’s conscious and purposeful choice to engage in entrepreneurial pursuits (

Thompson, 2009). It reflects an inclination and commitment of a person to initiate and manage independent business ventures (

Esfandiar et al., 2019). It encompasses the cognitive process of identifying business opportunities, assessing risks and rewards, and making a deliberative decision to embark on an entrepreneurial path. This process requires credible information for making informed and competitive decisions, generating business value. In this regard, IL is strongly connected to the development and sustenance of an entrepreneurial mindset capable of initiating entrepreneurial ventures (

Bosman et al., 2023). Scholars have highlighted the positive role of IL in environmental scanning to identify business opportunities (e.g.,

Zhang et al., 2010a).

Entrepreneurs with advanced IL skills are better positioned to assimilate diverse sources of information, fostering a continuous learning orientation, and demonstrate a heightened capacity to recognize gaps in the market and to formulate innovative strategies (

Bae et al., 2014;

Foo et al., 2012). Additionally, IL influence on decision-making and risk management has also been emphasized, with research indicating that entrepreneurs with strong IL skills are better equipped to make informed choices and navigate uncertainties in the business environment (

Zhang et al., 2010b,

2014). This relationship also extends to the fostering of creativity and innovation within entrepreneurial endeavors, as IL-proficient individuals can leverage diverse information sources to stimulate novel ideas (

Naveed et al., 2023a,

2023b;

Saadia & Naveed, 2024;

Wu, 2019). The connection between IL and the entrepreneurial intention is symbiotic, with IL catalyzing the development and reinforcement of entrepreneurial attitudes and behaviors. Some studies also provided empirical evidence for the integral role of digital literacy, an element of IL, in shaping entrepreneurial intentions (e.g.,

Hutagalung et al., 2023;

Nugroho et al., 2023;

Onwubuya & Odogwu, 2023). However, only a few inquiries provided empirical evidence for a positive role of IL in shaping entrepreneurial intentions (e.g.,

Syam et al., 2021). However, the study of

Abaddi (

2024) reported a negative correlation between digital skills and entrepreneurial intentions of undergraduate university students in Jordan. There is still a lack of evidence about the interconnection between IL and entrepreneurial intentions. Furthermore, the results of existing studies also needed to be corroborated with varied samples from different geographical locations for theorization. Hence, the first research hypothesis was framed as given below:

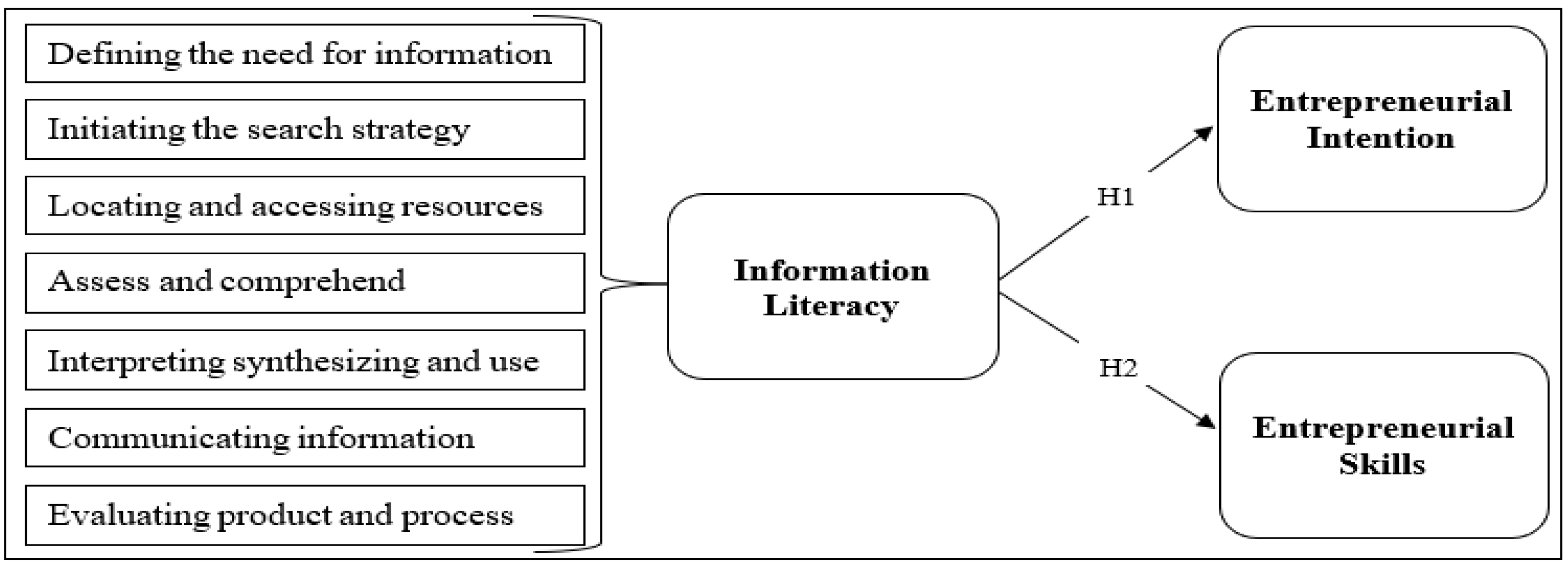

H1: Information literacy skills of business students positively influence their entrepreneurial intentions.

2.2. Information Literacy and Entrepreneurial Skills

Entrepreneurial skills refer to the ability to identify opportunities, innovate, take calculated risks, and effectively launch, manage, and grow successful ventures. Entrepreneurial pursuits require ambition as fuel, but IL and entrepreneurial skills are also essential to navigate the ever-changing landscape. Even though they are distinct in character, they intertwine and empower people to transform their aspirations into ventures. IL serves as a compass, empowering individuals to find credible information and equipping them in the identification of market opportunities, making strategic choices, and forging a valuable business network (

Solihin, 2023;

Chris-Israel et al., 2022;

Suryani & Chaniago, 2023). On the other hand, entrepreneurial skills are a toolkit of action-oriented abilities to conduct comprehensive market research, understand industry dynamics, identify lucrative opportunities, and take calculated risks (

Baldan & Hermawan, 2024;

Ndofirepi, 2024;

Saleh et al., 2024). The synergy between these two sets of skills is potent. IL empowers individuals with knowledge and direction, while entrepreneurial skills translate that knowledge into action. Therefore, the relationship between IL and entrepreneurial skills is synergistic, with one catalyzing the other, contributing significantly to the success and adaptability of entrepreneurs in a dynamic business landscape of the 21st century. The empirical evidence for this mutually reinforcing relationship was also provided by a few studies (e.g.,

Mohammadinejad & Tirgar, 2023;

Tatari & Mokhtari Dinani, 2018). More empirical evidence is still awaited using varied units of analysis from different geographical locations. Thus, the second research hypothesis was articulated as follows:

H2: Information Literacy skills of business students positively influence their entrepreneurial skills.

In view of the above discussion, IL, entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial skills are considered essential for startups and successful business ventures. Despite the crucial role of such skills, a relatively limited number of empirical studies have appeared so far to support a correlation between these constructs, especially among business students. There is a need for more empirical evidence for theorizing point of view about direct and positive IL influence on entrepreneurial intention and skills.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Model

This research primarily investigated the interrelations between IL, entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial skills using business students from the District of Sargodha, Pakistan. The following research model was proposed to depict the expected interrelationships between these constructs (

Figure 1).

3.2. Research Design and Method

A quantitative research approach utilizing a survey method was adopted for this study, with the aim of exploring the impact of IL on entrepreneurial intentions and skills among business students in Sargodha, Pakistan. Cresswell (

Creswell & Creswell, 2017) stated that a quantitative research approach is well-suited for assessing the beliefs, behaviors, and attitudes of individuals towards specific phenomena. Similar research designs have been employed in prior studies investigating IL among business students (e.g.,

Naveed & Mahmood, 2019,

2022).

3.3. Instrumentation

The study used the questionnaire as a data collection instrument. The questionnaire consisted of two sections, namely, the demographic section and the research variables section, such as IL literacy, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills. The scales to measure these research variables were adopted from the existing literature. The IL statements (28 in total) were sourced from the work of

Kurbanoglu et al. (

2006) and rated on a seven-point Likert scale (7 = almost always true, 6 = usually true, 5 = often true, 4 = occasionally true, 3 = sometimes but infrequently true, 2 = usually not true, 1 = almost never true). Meanwhile, entrepreneurial intention was evaluated using the scale developed by

Liñán & Chen (

2009), comprising six items, and entrepreneurial skills were assessed using the scale developed by

Liñán (

2008), also consisting of six statements. Each statement related to entrepreneurial intention and skills was rated on a five-point Likert scale (e.g., 5 = Strongly agree, 4 = Agree, 3 = Neutral, 2 = Disagree, 1 = Strongly Disagree). These scales were selected due to their widespread use in measuring IL, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills and their reported reliability and validity in existing literature (e.g.,

Kurbanoglu et al., 2006;

Liñán, 2008;

Liñán & Chen, 2009).

The initial version of the questionnaire underwent scrutiny by a panel of experts to assess its face and content validity, leading to revisions as necessary. The demographic section of the questionnaire encompassed aspects such as gender, age, program, and CGPA. The subsequent section of the questionnaire addressed the research inquiries concerning IL, entrepreneurial intentions, and entrepreneurial skills. Utilizing data from the present study, Cronbach’s alpha, a metric for gauging internal consistency, was employed to assess the reliability of the statements of IL, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills. The findings revealed that the measures utilized, including information literacy (28 items, CA = 0.861), entrepreneurial intentions (6 items, CA = 0.709), and entrepreneurial skills (6 items, CA = 0.656), demonstrated satisfactory levels of internal reliability, as indicated by their acceptable Cronbach’s alpha values.

3.4. Population and Sampling

The business students from the University of Lahore’s (Sargodha campus) and the University of Sargodha’s Noon Business School were considered as the population for this study. The size of the population was about 1093 students who enrolled in the universities of district Sargodha. The sample size was obtained using Yamane’s Formula n = N/1 + N (e)2, where e = 0.05. Applying the method, the sample size of 292 represented the entire population of 1093. The recruitment of the survey participants was made through a convenience sampling technique, as it is indeed an ideal method for choosing participants who are easily available at the moment of data collection (

Gay et al., 2012). Although random sampling methods are the best option for unbiased samples, it was challenging for researchers to choose samples at random due to no access to a comprehensive list of business students and time limitations.

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

The questionnaires were personally distributed to the survey participants by visiting their classrooms after getting approval from the academic heads. The survey questionnaires were distributed to participants during regular university hours. The process of data collection was completed in one to two months. The participation in the survey was voluntary. The involvement of humans as survey participants was cleared and approved by the ethical review board of the institution. A total of 277 responses were obtained, representing a response rate of 94%. After gathering data from the participants, the questionnaire was coded into an SPSS data sheet. Utilizing SPSS, descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentages, mean, and standard deviations were computed, alongside inferential statistics including Pearson correlation, independent samples t-test, one-way ANOVA, and simple linear regressions for data analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Participants’ Demographic Characteristics

Table 1 presented the demographic profile of the respondents. Of the 277 survey participants, there were 152 (54.9%) males and 125 (45.1%) females. The age range of survey participants spanned from 18 to 30 years. The majority of respondents (n = 192, 69.3%) fell within the age group of 21-25 years, with smaller proportions comprising those aged up to 20 years (n = 72, 25.9%) and over 26 years (n = 13, 4.7%). Additionally, a significant majority of participants (n = 258, 93.1%) were enrolled in 16-year programs (BS/MA), followed by MS/MPhil programs (n = 19, 6.9%). As far as their Cumulative Grade Point Average (CGPA) is concerned, most of these respondents (n = 157, 56.7%) scored a CGPA greater than 3.0, followed by those who scored a CGPA between 2.5 and 3.0 (n = 97, 35%) and up to 2.5 (n = 23, 8.3).

4.2. Relationship of IL Skills, Entrepreneurial Intention, and Entrepreneurial Skills with Personal and Academic Variables

Various statistical tests were employed to examine the association of IL skills, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills with personal factors among business students. The findings of these analyses are summarized in

Table 2. The results revealed no statistically significant relationship of IL skills, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills with personal or academic variables such as age, gender, and program of study (

p > 0.05). However, there was a statistically significant and positive correlation observed between the IL skills of business students and their CGPA (

p < 0.05). This suggests that an increase in the IL skills of business students corresponds to an increase in their CGPA.

4.3. Relationship of IL with Entrepreneurial Intentions and Entrepreneurial Skills

The Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to ascertain the nature of the relationship between information literacy, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills.

Table 3 provided a detailed overview of these results. The data indicated a statistically significant and positive correlation between information literacy and its components with entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial skills among the business students. The strength of the relationship of each component of IL with entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial skills ranged from moderate to large, as per the criteria suggested by

Cohen (

1988,

1992) for social sciences. However, there were substantial associations observed between overall IL skills and entrepreneurial intention, as well as entrepreneurial skills. Consequently, a simple linear regression analysis could be conducted to assess the impact of IL on entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial skills.

4.4. Effect of IL on Entrepreneurial Intentions and Entrepreneurial Skills

4.4.1. Effect of IL on Entrepreneurial Intention

Several simple linear regression analyses were conducted to assess the influence of IL and its components on entrepreneurial intention among business students. The detailed outcomes of these analyses are presented in

Table 4. Each of the eight models in

Table 4 will be discussed individually in the subsequent paragraphs.

Model 1: Defining the need for information (Component 1) on entrepreneurial intention. A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to predict entrepreneurial intention based on the first component of IL, namely, ‘defining the need for information’. They showed a significant regression equation [F (277) = 20.797,

p = 0.000, R

2 = 0.070]. According to

Table 4, ‘defining the need for information’ was a statistically significant and favorable component predicting the entrepreneurial intention among business students (β = 0.265,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 2: Initiating the search strategy (Component 2) on entrepreneurial intention. A simple linear regression analysis was done to predict entrepreneurial intention based on the second component, tagged as ‘initiating the search strategy’, which revealed a significant regression equation [F (277) = 23.391,

p = 0.000, R

2 = 0.279]. ‘Initiating the search strategy’ was a significant and favorably predictive factor of entrepreneurial intention among university students, as shown in

Table 4 (β = 0.391,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 3: Locating and accessing the resources (Component 3) on entrepreneurial intention. Table 4 also indicated a statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 98.528,

p = 0.000, R

2 = 0.264] to predict entrepreneurial intention based on the third component, such as ‘locating and accessing information’. Locating and accessing information also appeared to be a statistically significant predictor of entrepreneurial intention among business students (β = 0.514,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 4: Assessing and comprehending information (Component 4) on entrepreneurial intention. A statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 62.495,

p = 000, R

2 = 0.185] also appeared for entrepreneurial intention based on the fourth component, namely, ‘assessing and comprehending information’ (

Table 4). ‘Assessing and comprehending information’ (β = 0.430,

p = 0.000 < 0.05) also appeared to be a statistically significant predictor of entrepreneurial ambition among business students.

Model 5: Interpreting, synthesizing, and using information (Component 5) on entrepreneurial intention. The figures in

Table 4 also showed a statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 7.361,

p = 0.000, R

2 = 0.026] for entrepreneurial intention based on ‘interpreting, synthesizing, and using information’. The fifth component, such as ‘interpreting, synthesizing, and utilizing information,’ also appeared to predict entrepreneurial intention statistically among these business students (β = 0.161,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 6: Communicating information (Component 6) on entrepreneurial intention.Table 4 also showed a statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 42.778,

p = 0.000, R

2 = 0.135] for entrepreneurial intention based on ‘communicating information’. ‘Communicating information’ also appeared as a statistically significant and favorable predictor for entrepreneurial intention. (β = 0.367,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 7: Evaluating the product and process (Component 7) on entrepreneurial intention. A simple linear regression analysis was also carried out to predict entrepreneurial intention based on ‘evaluating the product and process’. The findings showed a significant regression equation (F (277) = 24.899,

p = 0.000), with an R

2 of 0.083 (

Table 4). ‘Evaluating the product and process’ was a strong predictor of entrepreneurial intention among business students (β = 0.288,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 8: Effect of IL skills (overall scale) on entrepreneurial intention. The figures in

Table 4 also indicated a statistically significant regression equation (F (277) = 104.396,

p = 0.000), with an R

2 of 0.275 to predict entrepreneurial intention based on overall IL skills. IL skills of business students appeared as a statistically significant predictor of entrepreneurial intention among business students (β = 0.525,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Based on the results in

Table 4, which show a positive relationship between overall IL scores and entrepreneurial intention, we can confirm that information literacy (IL) positively influences entrepreneurial intention among business students. This finding supports our research hypothesis (H1).

4.4.2. Effect of IL on Entrepreneurial Skills

Simple linear regression analyses were also conducted to examine the effect of IL and each of its sub-dimensions on entrepreneurial skills among business students. The detailed results of these analyses are provided in

Table 5.

Model 1: Defining the need for information (Factor 1) on entrepreneurial skills. The figures in

Table 5 revealed a statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 23.288,

p = 0.000] with an R2 of 0.078 to predict entrepreneurial skills based on factor 1, namely, ‘defining the need for information’. ‘Defining the need for information’ also appeared to be a statistically significant and favorable predictor of entrepreneurial skills among business students (β = 0.514,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 2: Initiating the search strategy (Factor 2) on entrepreneurial skills. A statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 21.389,

p = 0.000, R

2 = 0.271] also appeared for entrepreneurial intention based on the second factor of information literacy, namely, ‘initiating the search strategy’ (

Table 5). These figures also showed that ‘initiating the search strategy’ was a statistically significant and positive predictor of business students’ entrepreneurial skills (β = 0.387,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 3: Locating and accessing the resources (Factor 3) on entrepreneurial skills. The results of a simple linear regression analysis in

Table 4 for entrepreneurial skills based on the third factor, namely, ‘Locating and accessing the resources’, also showed a statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 118.323,

p = 0.000, R

2 = 0.301]. The third factor of information literacy also appeared to predict the entrepreneurial skills (β = 0.548,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 4: Assessing and comprehending information (Factor 4) on entrepreneurial skills. The results in

Table 5 showed a significant regression equation (F (277) = 72.813,

p = 0.000), with an R

2 of 0.209 for entrepreneurial skills based on the fourth factor, namely, ‘assessing and comprehending information’. This factor also predicted favorably the entrepreneurial skill of business students (β = 0.458,

p = 0.005 < 0.05).

Model 5: Interpreting, synthesizing, and using information (Factor 5) on entrepreneurial skills. Table 5 also showed a significant regression equation (F (277) = 21.444,

p = 0.000), with an R

2 of 0.072, for business students’ entrepreneurial skills based on the fifth IL factor labeled as ‘interpreting, synthesizing, and using information’. The results also showed ‘interpreting, synthesizing, and using information’ as a statistically significant predictor of entrepreneurial skills (β = 0.269,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 6: Communicating Information (Factor 6) on entrepreneurial skills. There was a statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 58.140,

p = 0.000, R

2 = 0.175] for entrepreneurial capabilities of university students based on the 6th IL factor, namely, ‘communicating information’ (

Table 5). ‘Communicate information’ also appeared as a statistically significant predictor of business students’ entrepreneurial skills (β = 0.418,

p = 0.000 < 0.05).

Model 7: Evaluating the product and process (Factor 7) on entrepreneurial skills. A simple linear regression analysis was conducted to predict entrepreneurial skills based on the seventh factor labeled ‘evaluating the product and process’ (

Table 5). The results indicated a statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 15.585,

p < 0.001]. ‘Evaluating the product and process’ emerged as a significant predictor of entrepreneurial skills (β = 0.232,

p < 0.001).

Model 8: Effect of IL Skills (overall scale) on entrepreneurial skills. Table 5 also indicated a statistically significant regression equation [F (277) = 131.755,

p = 0.000, R

2 = 0.324] to predict entrepreneurial skills based on overall IL skills. IL skills of business students appeared as a statistically significant predictor of entrepreneurial skills among business students (β = 0.569,

p = 0.000, 0.05).

Examining the figures presented in

Table 5, it is reasonable to assert that there is a positive effect of IL on entrepreneurial skills in business students. Consequently, the research hypothesis is supported.

5. Discussion

The primary objective of the proposed research was to investigate the effect of IL on entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial skills among business students in the Sargodha district of Pakistan, using a cross-sectional survey approach. The findings revealed that these business students did not possess an optimal level of IL, as they tended to rate themselves as occasionally true to often true for IL statements. This outcome was expected due to the absence of an effective IL instruction program in the selected universities. The current state of IL instruction programs in university libraries in Pakistan is still in its early stages, offering only basic levels of IL instruction (

Anwar & Naveed, 2019;

Hamid & Ahmad, 2016;

Kousar & Mahmood, 2015;

Naveed & Mahmood, 2019,

2022;

Ullah & Ameen, 2014). These findings align with previous studies, which also reported that the IL self-efficacy of business students was not at an optimal level, as they were less comfortable with advanced IL skills (

Naveed & Mahmood, 2019,

2022).

The results also showed IL as the predictor of entrepreneurial intention. This finding was expected, as the ability to find, access, and use the needed information can contribute to the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Several research scholars have emphasized the positive role of IL in effective environmental scanning and recognition of business opportunities (

Zhang et al., 2010a), identification of market gaps and formulation of innovative strategies (

Bae et al., 2014;

Foo et al., 2012) and evidence-based decision making and risk management (

Zhang et al., 2010b,

2014). The intricate nature of the relationship between IL and the entrepreneurial intention appears to be symbiotic, where IL plays a catalytic role for the development and reinforcement of entrepreneurial intentions. This finding appeared to be in line with that of

Syam et al. (

2021) who also reported IL as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions and corroborated the results of some other existing studies providing empirical evidence for a positive role of digital literacy, an IL element, in the development of entrepreneurial intentions (e.g.,

Hutagalung et al., 2023;

Nugroho et al., 2023;

Onwubuya & Odogwu, 2023). However, this finding contrasts with the results of

Abaddi (

2024), who reported an inverse relationship between digital skills and entrepreneurial intentions among undergraduate students in Jordanian universities.

A closer look at the results also revealed IL as a positive predictor of entrepreneurial skills.

These results were also expected, as the entrepreneurial process requires the information capabilities of efficient and effective environmental scanning, conducting marketing research, understanding market dynamics, recognizing lucrative business opportunities, developing entrepreneurial ventures, developing a business network, and achieving a sustainable competitive advantage (

Baldan & Hermawan, 2024;

Chris-Israel et al., 2022;

Ndofirepi, 2024;

Saleh et al., 2024;

Solihin, 2023;

Suryani & Chaniago, 2023). This finding corroborated the results of a few other previous studies reporting the positive effects of IL on entrepreneurial skills (e.g.,

Esmaeil Pounaki et al., 2016;

Mokhtari Dinani & Tatari, 2018;

Zardoshtian et al., 2018). Likewise,

Mohammadinejad and Tirgar (

2023) also reported a positive relationship of IL with entrepreneurial capabilities among students of technical art schools at Kerman, Iran. Another study from Iran by

Tatari and Mokhtari Dinani (

2018) reported a positive effect of IL on the entrepreneurial capability of physical education students at Tehran state universities in Iran.

6. Conclusions and Implications

Several conclusions can be derived from these findings. Firstly, there remains a need for improvement in the IL skills of business students, as they assessed themselves as often true to usually true for IL statements. Secondly, IL also exhibited a statistically significant but positive correlation with academic achievement. Thirdly, there was a positive and statistically significant correlation observed between IL, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills. Lastly, IL also appeared to have a positive effect on entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial skills. In other words, IL exerted a positive influence on both entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial skills. Lastly, IL also exhibited a positive correlation with academic achievement.

These findings carry both theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical standpoint, this study provided empirical evidence for IL as a predictor of entrepreneurial intentions and entrepreneurial skills, contributing to the theoretical understanding of the factors that foster entrepreneurial development. Moreover, these results provide pragmatic insight into IL effectiveness for business education, suggesting IL as a critical component rather than a general academic skill that contributes to specific professional outcomes like entrepreneurial success. These findings also demonstrated a positive correlation between IL and entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial skills, suggesting that future theoretical models of entrepreneurial development should explicitly incorporate IL as a significant antecedent or moderating variable. Furthermore, the replication of a positive correlation between IL and academic achievement reinforces existing theories about the broader benefits of IL in educational contexts. Although these results needed to be corroborated for generalization, they still have a significant contribution to the existing IL literature.

In terms of practical implications, this newfound knowledge can guide educators and policymakers in developing strategies to better equip students with the IL skills needed to thrive in business and entrepreneurship. These findings offer insights for policies and practices about business education in general and entrepreneurial education in particular, as these results can guide curriculum by shedding light on the connections between IL, entrepreneurial intentions, and entrepreneurial skills among business students. These findings may be used by policymakers in the education field to create and enhance educational programs that encourage students to develop their entrepreneurial and IL skills. To better prepare students for entrepreneurial endeavors, educators can integrate IL training and exercises into the curriculum. The study’s findings may point to particular areas where students’ entrepreneurial or IL skills are lacking. To successfully address these issues, specific interventions and support systems may be created using the information provided. In addition, these results have the potential to highlight specific areas where students’ entrepreneurial or IL abilities need improvement. Using the information supplied, specialized treatments and support systems may be developed to successfully address these difficulties. The study’s findings may be used to highlight the significance of IL in a variety of professional pathways by highlighting its usefulness for problem-solving, decision-making, and flexibility in a changing labor market. The study’s findings can provide direction for organizations and governments working to promote entrepreneurship through the efficiency of IL programs as a way to foster and encourage young entrepreneurs in the area.

These findings may encourage an innovative culture and ethical business practices in District Sargodha by placing more of a focus on entrepreneurship and IL. The research can further our understanding of IL and entrepreneurship in the particular setting of Pakistan’s District Sargodha. To further examine and expand our understanding of this relationship, researchers and academics may build on these results. As a whole, the study’s findings may be used as a basis for future investigation, the creation of public policy, and practical activities targeted at fostering entrepreneurship and IL among business students in District Sargodha, Pakistan.

7. Limitations

This research has several limitations that should be acknowledged when attempting to generalize its findings. Firstly, the study relied on self-reported measures to gauge information literacy (IL), entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills. Consequently, there is a possibility that participants may have overestimated their levels of IL, entrepreneurial intention, and entrepreneurial skills. Secondly, the research sites were purposely selected, and the survey respondents were recruited through a convenience sampling method, both belonging to non-probability sampling, which may have resulted in the inclusion of a non-representative sample for this study. Lastly, data collection was limited to only two institutions within the district of Sargodha, Punjab, Pakistan. Therefore, this research does not purport to represent the perspectives of all business students in Pakistan.

Author Contributions

I.B., conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, supervision, project administration. T., conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration. Vafa Asgarova, data curation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing, validation. M.A.N., conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration. M.Z.A., resources, methodology, supervision, writing—review and editing. S.F.R., visualization, funding acquisition, validation, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by the Internal Research Project (UoN/19/IF/2025), the University of Nizwa, Oman.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Department of Information Management, University of Sargodha (protocol code UoS/IM/061 and 23 April 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests or conflicts of interest associated with this research.

References

- Abaddi, S. (2024). Digital skills and entrepreneurial intentions for final-year undergraduates: Entrepreneurship education as a moderator and entrepreneurial alertness as a mediator. Management & Sustainability: An Arab Review, 3(3), 298–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadasi, N., Zhang, G., Al-Jubari, I., Al-Awlaqi, M. A., & Aamer, A. M. (2024). Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial behaviour: Do self-efficacy and attitude matter? The International Journal of Management Education, 22(1), 100945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M. A., & Naveed, M. A. (2019). Developments of information literacy in Pakistan: Background and research. Pakistan Library and Information Science Journal, 50(1), 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Association of College and Research Libraries. (2000). Information literacy competency standards for higher education. Association of College and Research Libraries. [Google Scholar]

- Atikuzzaman, M., Yesmin, S., & Abdul Karim, M. (2025). Measuring health information literacy in everyday life: A survey among tribal women in a developing country. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication, 74(1/2), 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, S., & Jafariharandi, R. (2020). Information literacy, knowledge sharing and entrepreneurial capabilities of Qom University students. Sciences and Techniques of Information Management, 6(3), 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Baldan, N., & Hermawan, A. (2024). The influence of entrepreneurial education and entrepreneurial skills on entrepreneurial intentions through the internship program as an intervening variable for vocational school students in Banyuwangi Regency. Formosa Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 3(1), 105–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banik, P., & Kumar, B. (2019). Impact of information literacy skill on students’ academic performance in Bangladesh. International Journal of European Studies, 3(1), 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosman, L., Kotla, B., Cuesta, C., Duhan, N., & Oladepo, T. (2023). The role of information literacy in promoting “discovery” to cultivate the entrepreneurial mindset. Journal of International Education in Business, 16(1), 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, C. (2004, November 10–12). Information literacy as a catalyst for educational change: A background paper. The 3rd International Lifelong Learning Conference, Yeppoon, QLD, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Cardella, G. M., Hernández-Sánchez, B. R., & Sánchez García, J. C. (2020). Entrepreneurship and family role: A systematic review of a growing research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charted Institute of Library & Information Professionals. (2018). What is information literacy? Available online: https://www.cilip.org.uk/news/421972/What-is-information-literacy.htm (accessed on 30 June 2024).

- Chris-Israel, H. O., Onuoha, U. D., & Ojokuku, B. Y. (2022). Influence of information literacy skills on infopreneurship intentions of library and information science undergraduates in public universities in South-West, Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice (ejournal), 7271. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/7271 (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coşkun, Y. D., & Demirel, M. (2010). Lifelong learning tendency scale: The study of validity and reliability. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. (2016). What having a “growth mindset” actually means. Harvard Business Review, 13(2), 2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Esfandiar, K., Sharifi-Tehrani, M., Pratt, S., & Altinay, L. (2019). Understanding entrepreneurial intentions: A developed integrated structural model approach. Journal of Business Research, 94, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeil Pounaki, E., Esmaili Givi, M. R., & Fahimnia, F. (2016). Media literacy and information literacy and its impact on entrepreneurial ability. Human Information Interaction, 2(4), 64–76. [Google Scholar]

- Foo, S., Majid, S., & Chang, Y. K. (2017). Assessing information literacy skills among young information age students in Singapore. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 69(3), 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, S., Majid, S., & Zhang, X. (2012). Perceived environmental uncertainty, information literacy and environmental scanning: Towards a refined framework. Information Research, 17(2), 515. Available online: http://InformationR.net/ir/17-2/paper515.html (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Gay, L. R., Mills, G. E., & Airasian, P. W. (2012). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and applications (10th ed.). Merrill/Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid, A., & Ahmad, Z. (2016). User education programs in university libraries: A survey. Pakistan Library and Information Science Journal, 47(1), 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, F., Qi, M. D., Su, Y., Wu, Y. J., & Tang, J. Y. (2023). How does university-based entrepreneurship education facilitate the development of entrepreneurial Intention? Integrating passion-and competency-based perspectives. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutagalung, T., Wibowo, A., & Zahra, S. F. (2023). The mediating effect of self-efficacy on the influence of economic literacy and digital literacy on digital entrepreneurship intentions of Jakarta State University students. International Journal of Current Economics & Business Ventures, 3(2), 186–203. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, W. L., & Mastrorilli, T. (2022). Assessing the impact of an information literacy course on students’ academic achievement: A mixed-methods study. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice, 17(2), 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, H. (2021). Entrepreneurial capabilities of librarians in university libraries: A cross-contextual study on the impact of information literacy. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship, 26(3–4), 200–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kesici, A. (2022). The effect of digital literacy on creative thinking disposition: The mediating role of lifelong learning disposition. Journal of Learning and Teaching in Digital Age, 7(2), 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korani, Z. (2022). The Relationship between presence knowledge and entrepreneurial capabilities of razi university agricultural students. Journal of Agricultural Education Administration Research, 14(60), 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousar, M., & Mahmood, K. (2015). Perceptions of faculty about information literacy skills of postgraduate engineering students. International Information & Library Review, 47(1–2), 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kurbanoglu, S. S., Akkoyunlu, B., & Umay, A. (2006). Developing the information literacy self-efficacy scale. Journal of documentation, 62(6), 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurjono, H. Y., Yohana, C., & Ferriady, M. (2023). Determinant of entrepreneurial intention at high education. Central European Management Journal, 31(1), 331–341. [Google Scholar]

- Liñán, F. (2008). Skill and value perceptions: How do they affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 4, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y.-W. (2009). Development and coss-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, M. (2011). Lifelong learning: Introduction. In The Oxford handbook of lifelong learning (pp. 3–11). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Machin-Mastromatteo, J. (2021). Information and digital literacy initiatives. Information Development, 37, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, S., Foo, S., & Chang, Y. K. (2020). Appraising information literacy skills of students in Singapore. Aslib Journal of Information Management, 72(3), 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadinejad, Y., & Tirgar, H. (2023). Study of the relationship between information literacy and entrepreneurship with the mediating role of social skills of the art students of technical art schools. Information and Communication Technology in Educational Sciences, 13(4), 108–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mokhtari Dinani, M., & Tatari, S. (2018). The relationship between information literacy and entrepreneurial capabilities of sports science graduated students of Tehran universities. Research on Educational Sport, 6(15), 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Mughari, S., Naveed, M. A., & Rafique, G. M. (2023). Effect of information literacy on academic performance of business students in Pakistan. Libri, 73(4), 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M. A., Iqbal, J., Asghar, M. Z., Shaukat, R., & Kishwer, R. (2023a). How information literacy influences creative skills among medical students? The mediating role of lifelong learning. Medical Education Online, 28(1), 2176734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M. A., Iqbal, J., Asghar, M. Z., Shaukat, R., & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. (2023b). Information literacy as a predictor of work performance: The mediating role of lifelong learning and creativity. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M. A., & Mahmood, M. (2019). Information literacy self-efficacy of business students in Pakistan. Libri, 69(4), 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, M. A., & Mahmood, M. (2022). Correlatives of business students’ perceived information literacy self-efficacy in the digital information environment. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 54(2), 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndofirepi, T. M. (2024). Examining the influence of entrepreneurial skills, human capital, and home country institutions on firm internationalization. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 43(5), 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A., Widjaja, S. U. M., & Utomo, S. H. (2023). the influence of digital literacy and academic support on entrepreneurship intention through internal locus of control (study of s1 students class of 2019 faculty of economics and business, state university of malang). International Journal of Economics, Business and Innovation Research, 2(3), 264–278. [Google Scholar]

- Onwubuya, U. N., & Odogwu, I. C. (2023). Digital literacy and entrepreneurial intentions of business education students in tertiary institutions. International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Research, 9(6), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascucci, T., Hernàndez Sànchez, B. R., & Sànchez Garcìa, J. C. (2024). The business angel, being both skilled and decent. Administrative Sciences, 14(11), 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, C., Webb, J. W., Ireland, R. D., & Ketchen, D. J., Jr. (2016). Toward an integration of the behavioral and cognitive influences on the entrepreneurship process. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 10(1), 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadia, H., & Naveed, M. A. (2024). Effect of information literacy on lifelong learning, creativity, and work performance among journalists. Online Information Review, 48(2), 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M. A. K., Rajappa, M. K., & Almasloukh, S. (2024). Imparting entrepreneurial skills among undergraduates in unstable environments: Evidence from Iraq, Syria and Yemen. International Journal of Knowledge and Learning, 17(1), 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipman, J. P., Kurtz-Rossi, S., & Funk, C. J. (2009). The health information literacy research project. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 97(4), 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solihin, R. (2023). Analysis entrepreneurial literacy and entrepreneurial leadership to entrepreneurial intention of students in Bandung city. Journal of Business and Finnance in Emerging Markets, 6(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryani, S., & Chaniago, H. (2023). Digital literacy and its impact on entrepreneurial intentions: Studies on vocational students. International Journal of Administration and Business Organization, 4(2), 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syam, A., Rakib, M., Jufri, M., Utami, N. F., & Sudarmi, S. (2021). Entrepreneurship education, information literacy, and entrepreneurial interests: An empirical study. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 27(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Tatari, S., & Mokhtari Dinani, M. (2018). Modeling the relationship between information literacy and creativity and entrepreneurial capability of higher education physical education students in Tehran Universities. New Trends in Sport Management, 6(22), 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(5), 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M., & Ameen, K. (2014). Current status of information literacy instruction practices in medical libraries of Pakistan. Journal of the Medical Library Association, 102(4), 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M. S. (2019). Information literacy, creativity and work performance. Information Development, 35(5), 676–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardoshtian, S., Abbasi, H., & Khanmoradi, S. (2018). The effect of media literacy on entrepreneurship capabilities with the mediator role of information literacy in students of sport sciences. Communication Management in Sport Media, 5(2), 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Majid, S., & Foo, S. (2010a). Environmental scanning: An application of information literacy skills at the workplace. Journal of Information Science, 36(6), 719–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Majid, S., & Foo, S. (2010b). The role of information literacy in environmental scanning as a strategic information system—A study of singapore SMEs. In S. Kurbanoğlu, U. Al, P. Lepon Erdoğan, Y. Tonta, & N. Uçak (Eds.), Technological convergence and social networks in information management. IMCW 2010. Communications in computer and information science (Vol. 96). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Majid, S., & Foo, S. (2014). Exploring workplace experiences of information literacy through environmental scanning process. In Library and information science research in Asia-Oceania: Theory and practice (pp. 124–140). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).