The Impact of Animated Mascot Displays on Consumer Evaluations in E-Commerce

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Anthropormorphism Theory and Mascots

2.2. The Effects of Humanized Mascots

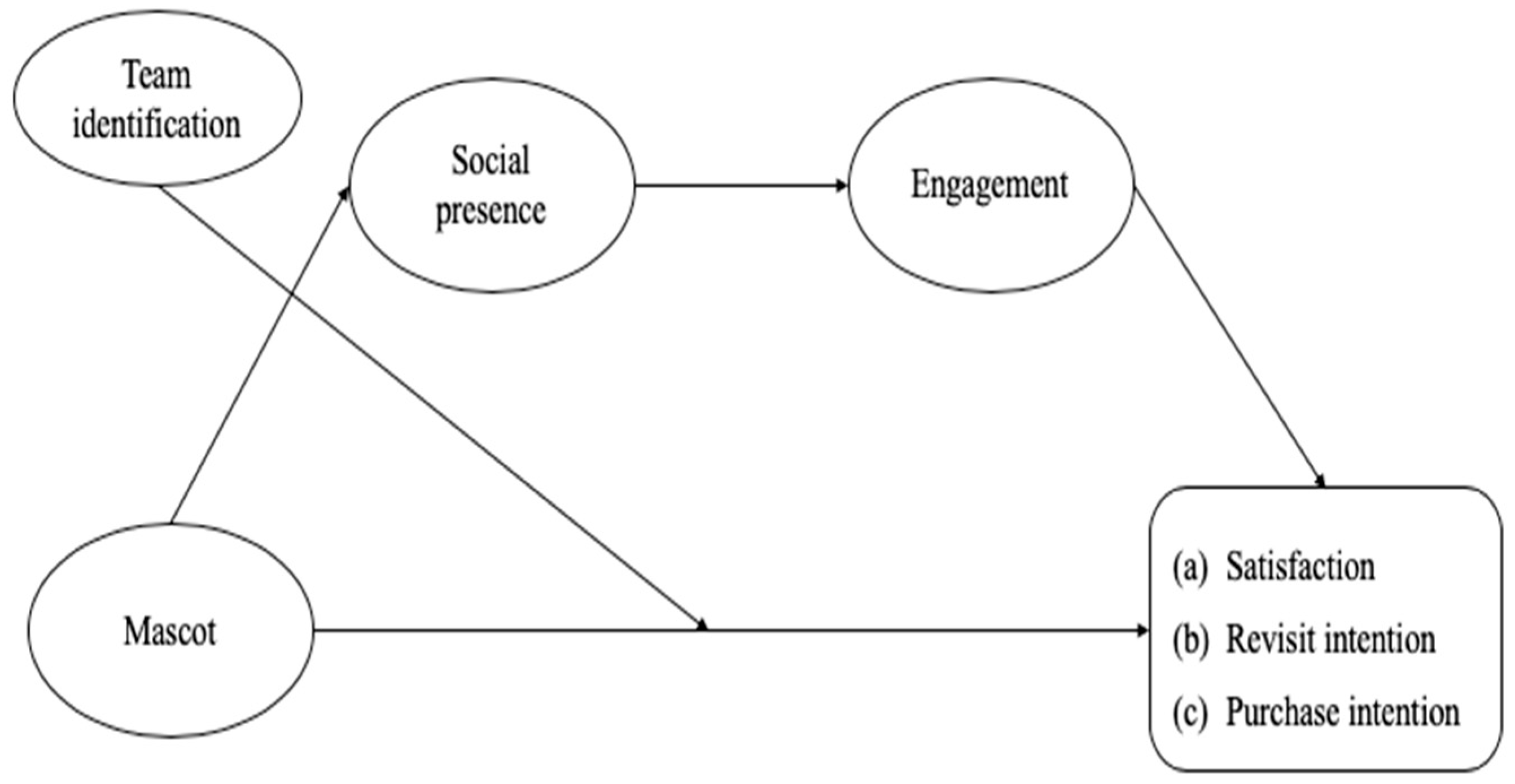

2.3. Social Presence and Engagement as a Key Underlying Mechanism

2.4. Movement in Mascot

2.5. Mascot Movement and Team Identification

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Design

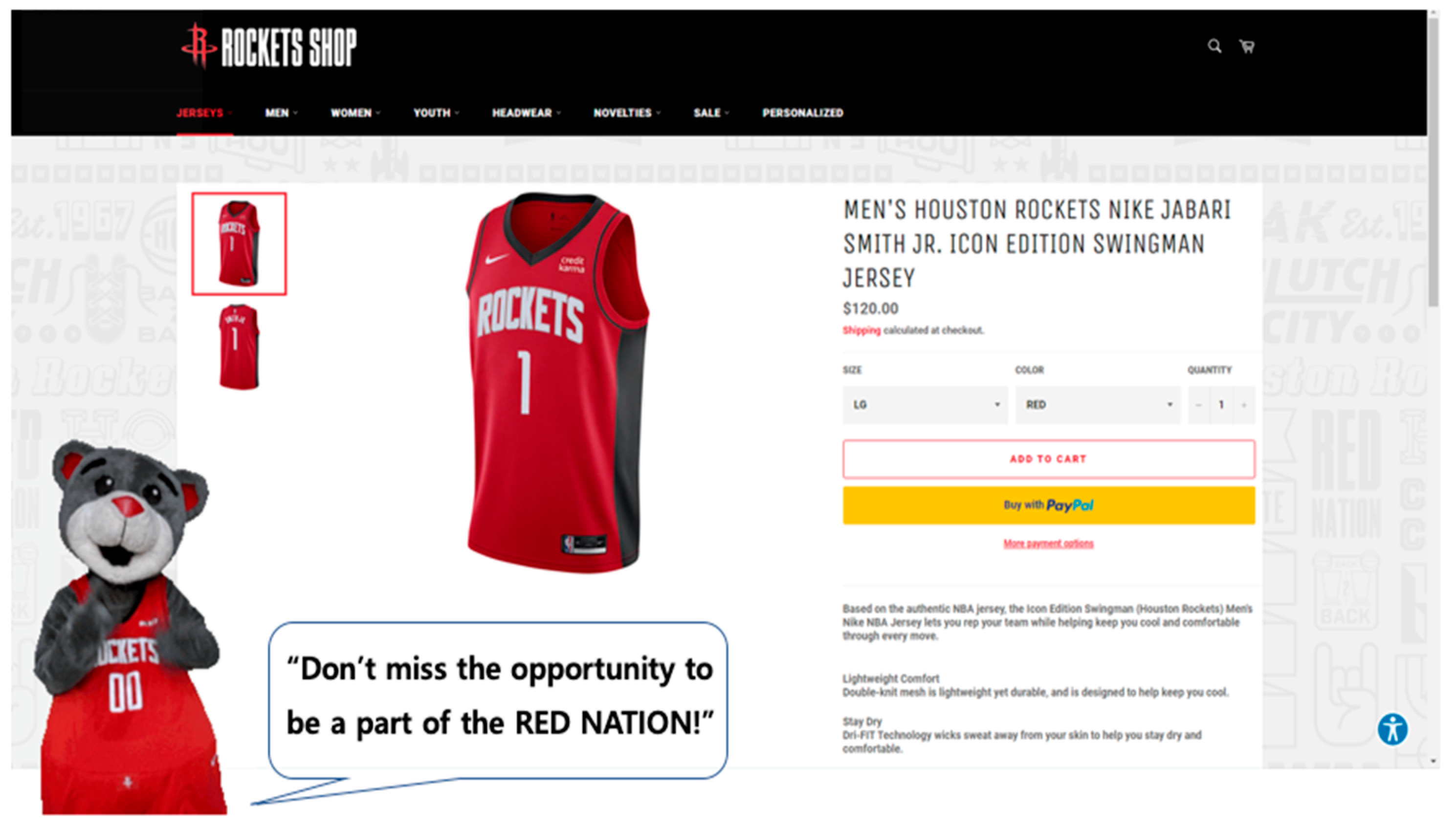

3.2. Manipulation of Different Types of Mascot on Team E-Commerce Website

3.3. Procedure

3.4. Measures

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Validation

4.2. Manipulation of Mascot Display

4.3. Testing H1 and H2

4.4. Testing H3 and H4

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Agenda

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aggarwal, P., & McGill, A. L. (2007). Is that car smiling at me? Schema congruity as a basis for evaluating anthropomorphized products. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(4), 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P., & McGill, A. L. (2012). When brands seem human, do humans act like brands? Automatic behavioral priming effects of brand anthropomorphism. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(2), 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, B. P., & Konstan, J. A. (2006). On the need for attention-aware systems: Measuring effects of interruption on task performance, error rate, and affective state. Computers in Human Behavior, 22(4), 685–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bente, G., Rüggenberg, S., Krämer, N. C., & Eschenburg, F. (2008). Avatar-mediated networking: Increasing social presence and interpersonal trust in net-based collaborations. Human Communication Research, 34(2), 287–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2001). Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Quarterly, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branscombe, N. R., Wann, D. L., Noel, J. G., & Coleman, J. (1993). In-group or out-group extremity: Importance of the threatened social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19(4), 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasel, S. A., & Hagtvedt, H. (2016). Living brands: Consumer responses to animated brand logos. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44, 639–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, E., Kumar, V., Li, X., Sollers, J., 3rd, Stafford, R. Q., MacDonald, B. A., & Wegner, D. M. (2013). Robots with display screens: A robot with a more humanlike face display is perceived to have more mind and a better personality. PLoS ONE, 8(8), 72589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Jurić, B., & Ilić, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruwer, B., Emsley, R., Kidd, M., Lochner, C., & Seedat, S. (2008). Psychometric properties of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in youth. Comprehensive & Psychiatry, 49(2), 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, R. J. (1984). Mentors in organizations. Group & Organization Studies, 9(3), 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- Callais, T. M. (2010). Controversial mascots: Authority and racial hegemony in the maintenance of deviant symbols. Sociological Focus, 43(1), 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Zhu, D. H. (2022). Effect of dynamic promotion display on purchase intention: The moderating role of involvement. Journal of Business Research, 148, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M. Y., Hong, W., & Thong, J. Y. (2017). Effects of animation on attentional resources of online consumers. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 18(8), 605–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. K., Miracle, G. E., & Biocca, F. (2001). The effects of anthropomorphic agents on advertising effectiveness and the mediating role of presence. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 2(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, E., Subramaniam, G., & Dass, L. C. (2020). Online learning readiness among university students in Malaysia amidst COVID-19. Asian Journal of University Education, 16(2), 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cian, L., Krishna, A., & Elder, R. S. (2014). This logo moves me: Dynamic imagery from static images. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(2), 84–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, P. M. (2013). The role of baseline physical similarity to humans in consumer responses to anthropomorphic animal images. Psychology & Marketing, 30(6), 461–468. [Google Scholar]

- Dalakas, V., & Rose, G. (2013). Developing brand identity in sport: Lions, and tigers, and bears oh my. In Leveraging brands in sport business (pp. 109–122). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Davou, K., Thwaites, D., & Chadwick, S. (2008). Emotional engagement and experiential marketing: A case study of the Athens Olympic Games. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 4(1), 102–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbaere, M., McQuarrie, E. F., & Phillips, B. J. (2011). Personification in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 40(1), 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Melo, C. M., Carnevale, P. J., Read, S. J., & Gratch, J. (2014). Reading people’s minds from emotion expressions in interdependent decision making. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 106(1), 73–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, D. R., & Dholakia, R. R. (2005). Interactivity and vividness effects on social presence and involvement with a web-based advertisement. Journal of Business Research, 58(3), 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, D. C., & James, J. D. (2001). The development of the Sport Interest Inventory: A tool for measuring fan identification. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 3(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y., Koufaris, M., & Ducoffe, R. H. (2004). An experimental study of the effects of promotional techniques in web-based commerce. Journal of Electronic Commerce in Organizations, 2(3), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2004). Consumer trust in B2C e-commerce and the importance of social presence: Experiments in e-products and e-services. Omega, 32(6), 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Go, E., & Sundar, S. S. (2019). Humanizing chatbots: The effects of visual, identity and conversational cues on humanness perceptions. Computers in Human Behavior, 97, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D. G., Suri, S., McAfee, R. P., Ekstrand-Abueg, M., & Diaz, F. (2014). The economic and cognitive costs of annoying display advertisements. Journal of Marketing Research, 51(6), 742–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigsby, J. L., Zamudio, C., & Jewell, R. D. (2022). Not so bad after all: How format influences review writers’ post-review evaluations. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 21(6), 1365–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, G., Pichierri, M., Nataraajan, R., & Pino, G. (2016). Animated logos in mobile marketing communications: The roles of logo movement directions and trajectories. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 6048–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gwinner, K., & Swanson, S. R. (2003). A model of fan identification: Antecedents and sponsorship outcomes. Journal of Services Marketing, 17(3), 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M. C. (2021). The impact of anthropomorphism on consumers’ purchase decision in chatbot commerce. Journal of Internet Commerce, 20(1), 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P., & Royne, M. B. (2017). Being human: How anthropomorphic presentations can enhance advertising effectiveness. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 38(2), 129–145. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heere, B., & James, J. D. (2007). Sports teams and their communities: Examining the influence of external group identities on team identity. Journal of Sport Management, 21(3), 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T., Gwinner, K. P., & Gremler, D. D. (2002). Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: An integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4(3), 230–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W., Thong, J. Y., & Tam, K. Y. (2004). Does animation attract online users’ attention? The effects of flash on information search performance and perceptions. Information Systems Research, 15(1), 60–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W., Thong, J. Y., & Tam, K. Y. (2007). How do Web users respond to non-banner-ads animation? The effects of task type and user experience. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(10), 1467–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F., Wong, V. C., & Wan, E. W. (2020). The influence of product anthropomorphism on comparative judgment. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(5), 936–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S. A. A. (2010). Effects of 3D virtual haptics force feedback on brand personality perception: The mediating role of physical presence in advergames. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(3), 307–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joosten, H., Sirin, A., Couwenberg, J., Laine, J., & Smith, P. (2016). The role of peatlands in climate regulation. In A. Bonn, T. Allott, M. Evans, H. Joosten, & R. Stoneman (Eds.), Peatland restoration and ecosystem services: Science, policy and practice (pp. 63–76). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanaraman, S., & Oliver, M. B. (2001, August 5–8). Technology or tradition: Exploring relative persuasive appeals of animation, endorser credibility, and argument strength in web advertising. Annual Conference of the Association of Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Washington, DC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kees, J., Berry, C., Burton, S., & Sheehan, K. (2017). An analysis of data quality: Professional panels, student subject pools, and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Journal of advertising, 46(1), 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, J. H., Silvestre, B. S., McCarthy, I. P., & Pitt, L. F. (2012). Unpacking the social media phenomenon: Towards a research agenda. Journal of Public Affairs, 12(2), 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & McGill, A. L. (2011). Gaming with Mr. Slot or gaming the slot machine? Power, anthropomorphism, and risk perception. Journal of Consumer Research, 38(1), 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., & Sundar, S. S. (2012). Anthropomorphism of computers: Is it mindful or mindless? Computers in Human Behavior, 28(1), 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. M., & Kim, S. (2009). The relationships between team attributes, team identification and sponsor image. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 10(3), 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W. R., & He, J. (2006). A meta-analysis of the technology acceptance model. Information & Management, 43(6), 740–755. [Google Scholar]

- Ko, Y. J., Asada, A., Jang, W., Kim, D., & Chang, Y. (2022). Do humanized team mascots attract new fans? Application and extension of the anthropomorphism theory. Sport Management Review, 25(5), 820–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompatsiari, K., Ciardo, F., De Tommaso, D., & Wykowska, A. (2019, November 3–8). Measuring engagement elicited by eye contact in human-robot interaction. 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS) (pp. 6979–6985), Macau, China. [Google Scholar]

- Kruikemeier, S., Van Noort, G., Vliegenthart, R., & De Vreese, C. H. (2013). Getting closer: The effects of personalized and interactive online political communication. European Journal of Communication, 28(1), 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. L., & Ahn, S. (2012). Discrimination against Latina/os: A meta-analysis of individual-level resources and outcomes. The Counseling Psychologist, 40(1), 28–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. A., & Oh, H. (2021). Anthropomorphism and its implications for advertising hotel brands. Journal of Business Research, 129, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P. O. (2001). A likelihood approach to estimating phylogeny from discrete morphological character data. Systematic Biology, 50(6), 913–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K., Huang, G., & Bente, G. (2016). The impacts of banner format and animation speed on banner effectiveness: Evidence from eye movements. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. A., & Kim, T. (2016). Predicting user response to sponsored advertising on social media via the technology acceptance model. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 710–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G., & Wilson, A. (2019). Shopping in the digital world: Examining customer engagement through augmented reality mobile applications. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 210–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, B. P., & Robinson, M. D. (2006). Does “feeling down” mean seeing down? Depressive symptoms and vertical selective attention. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(4), 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B., Kim, D., & Ko, Y. (2025). Effect of in-game situations and advertisement animation in eSports on visual attention, memory, brand attitude and behavioral intentions. Internet Research. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morewedge, C. K., Preston, J., & Wegner, D. M. (2007). Timescale bias in the attribution of mind. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nass, C. I., Lombard, M., Henriksen, L., & Steuer, J. (1995). Anthropocentrism and computers. Behaviour & Information Technology, 14(4), 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, H. L., Cairns, P., & Hall, M. (2018). A practical approach to measuring user engagement with the refined user engagement scale (UES) and new UES short form. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 112, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, C. K., & Srinivasan, K. (2022). Psychological impact and influence of animation on viewer’s visual attention and cognition: A systematic literature review, open challenges, and future research directions. Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 2022(1), 8802542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putrevu, S., & Lord, K. R. (1994). Comparative and noncomparative advertising: Attitudinal effects under cognitive and affective involvement conditions. Journal of Advertising, 23(2), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L., & Benbasat, I. (2009). Evaluating anthropomorphic product recommendation agents: A social relationship perspective to designing information systems. Journal of Management Information Systems, 25(4), 145–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramish, M. S., Zia, M. Q., Saraih, U. N., Suanda, J., & Ansari, J. (2023). Does visual appeal moderates the impact of attitude towards advertising on brand attitude, attachment and loyalty? ReMark-Revista Brasileira de Marketing, 22(3), 1250–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifurth, K. R., Wear, H. T., & Heere, B. (2020). Creating fans form scratch: A qualitative analysis of child consumer brand perceptions of a new sport team. Sport Management Review, 23(3), 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifon, N. J., & Bender, J. (2011). The effects of cartoon characters on children’s emotional responses to advertising. Journal of Advertising, 40(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, M., Eyssel, F., Rohlfing, K., Kopp, S., & Joublin, F. (2013). To err is human (-like): Effects of robot gesture on perceived anthropomorphism and likability. International Journal of Social Robotics, 5, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, E. B., Sosa, R., Cappuccio, M., & Bednarz, T. (2022). Human–robot creative interactions: Exploring creativity in artificial agents using a storytelling game. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 9, 695162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashi, C. M. (2012). Customer engagement, buyer-seller relationships, and social media. Management Decision, 50(2), 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, B., & Sheffer, M. L. (2018). The mascot that wouldn’t die: A case study of fan identification and mascot loyalty. Sport in Society, 21(3), 482–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, D., Burgard, W., Fox, D., & Cremers, A. B. (2001, December 8–14). Tracking multiple moving objects with a mobile robot. 2001 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. CVPR 2001 (Vol. 1, p. I), Kauai, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The social psychology of telecommunications. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- So, K. K. F., King, C., Sparks, B. A., & Wang, Y. (2014). The role of customer Brand engagement in building consumer loyalty to tourism brands. Journal of Travel Research, 55(1), 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Tao, D., & Luximon, Y. (2023). In robot we trust? The effect of emotional expressions and contextual cues on anthropomorphic trustworthiness. Applied Ergonomics, 109, 103967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieler, M., & Germelmann, C. C. (2016). The ties that bind us: Feelings of social connectedness in socio-emotional experiences. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(6), 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, S. S. (2008). The MAIN model: A heuristic approach to understanding technology effects on credibility (pp. 73–100). MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. E. (1978). Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tam, K. P., Lee, S. L., & Chao, M. M. (2013). Saving Mr. Nature: Anthropomorphism enhances connectedness to and protectiveness toward nature. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touré-Tillery, M., & McGill, A. L. (2015). Who or what to believe: Trust and the differential persuasiveness of human and anthropomorphized messengers. Journal of Marketing, 79(4), 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W. H. S., Liu, Y., & Chuan, C. H. (2021). How chatbots’ social presence communication enhances consumer engagement: The mediating role of parasocial interaction and dialogue. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15(3), 460–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J. C., & Oakes, P. J. (1986). The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. British Journal of Social Psychology, 25(3), 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, E., Alavi, S., & Bezençon, V. (2022). Trojan horse or useful helper? A relationship perspective on artificial intelligence assistants with humanlike features. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 50(6), 1153–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J., Mende, M., Noble, S. M., Hulland, J., Ostrom, A. L., Grewal, D., & Petersen, J. A. (2017). Domo arigato Mr. Roboto: Emergence of automated social presence in organizational frontlines and customers’ service experiences. Journal of Service Research, 20(1), 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P. (2021). The effect of brand engagement and brand love upon overall brand equity and purchase intention: A moderated–mediated model. Journal of Promotion Management, 27(1), 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wann, D., Bayens, C., & Driver, A. (2004). Likelihood of attending a sporting event as a function of ticket scarcity and team identification. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 13(4), 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Wann, D. L. (2006). Understanding the positive social psychological benefits of sport team identification: The team identification-social psychological health model. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, & Practice, 10(4), 272. [Google Scholar]

- Wann, D. L., Waddill, P. J., Brasher, M., & Ladd, S. (2015). Examining sport team identification, social connections, and social well-being among high school students. Journal of Amateur Sport, 1(2), 27–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Warren, C., Carter, E. P., & McGraw, A. P. (2021). Being funny is not enough: The influence of perceived humor and negative emotional reactions on brand attitudes. In Humor in advertising (pp. 117–137). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S., Lei, S. I., Shen, H., & Xiao, H. (2020). Social presence, telepresence and customers’ intention to purchase online peer-to-peer accommodation: A mediating model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 42, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L., Korneliussen, T., & Grønhaug, K. (2009). The effect of ad value, ad placement and ad execution on the perceived intrusiveness of web advertisements. International Journal of Advertising, 28(4), 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T., Tang, J., Ye, S., Tan, X., & Wei, W. (2022). Virtual reality in destination marketing: Telepresence, social presence, and tourists’ visit intentions. Journal of Travel Research, 61(8), 1738–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C. Y., & Kim, K. (2005). Processing of animation in online banner advertising: The roles of cognitive and emotional responses. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(4), 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y., & Alavi, M. (2001). Media and group cohesion: Relative influences on social presence, task participation, and group consensus. MIS Quarterly, 25, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Kaber, D. B., Zhu, B., Swangnetr, M., Mosaly, P., & Hodge, L. (2010). Service robot feature design effects on user perceptions and emotional responses. Intelligent Service Robotics, 3, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Group | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 78 | 38.4% |

| Female | 125 | 61.6% | |

| Education Level | Highschool or GED | 27 | 13.3% |

| Some college | 50 | 24.6% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 90 | 44.3% | |

| Graduate degree | 34 | 16.7% | |

| Others | 2 | 1.0% | |

| Ethnicity | African-American | 21 | 10.3% |

| Asian | 40 | 19.7% | |

| Caucasian | 112 | 55.2% | |

| Hispanic | 23 | 11.3% | |

| Others | 7 | 3.4% | |

| Household Income | USD 9999 or less | 13 | 6.4% |

| USD 10,000~USD 39,999 | 40 | 19.7% | |

| USD 40,000~USD 69,999 | 59 | 29.1% | |

| USD 70,000~USD 119,999 | 50 | 24.6% | |

| USD 120,000~USD 199,999 | 26 | 12.8% | |

| USD 200,000 or higher | 15 | 7.4% | |

| Total | 203 | 100% |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 social presence | 0.762 | |||||

| 2 engagement | 0.562 ** | 0.816 | ||||

| 3 satisfaction | 0.512 ** | 0.418 ** | 0.794 | |||

| 4 revisit intention | 0.440 ** | 0.340 ** | 0.549 ** | 0.888 | ||

| 5 purchas intention | 0.487 ** | 0.347 ** | 0.429 ** | 0.789 ** | 0.871 | |

| 6 team idenfication | 0.339 ** | 0.249 ** | 0.298 ** | 0.455 ** | 0.485 ** | 0.819 |

| Factors and Items | CR | |

|---|---|---|

| Social presence | 0.91 | |

| I felt a sense of human contact with this mascot | 0.90 | |

| I felt a sence of sociability with this mascot | 0.87 | |

| When I saw this mascot, I felt there were a person who was a real source of comfort to me | 0.87 | |

| Engagement | 0.93 | |

| What was your perception of the mascot while you were looking at the website? | ||

| Involving | 0.89 | |

| Engagning | 0.97 | |

| Stimulating | 0.85 | |

| Satisfaction | 0.92 | |

| Please indicate whether you are satisfied with the website | ||

| Dissatisfied to satisfied | 0.83 | |

| Frustrated to contendted | 0.90 | |

| Annoyed to pleased | 0.95 | |

| Revisit intention | 0.96 | |

| How likely are you to use this website in the future? | ||

| Unlikely to likely | 0.95 | |

| Improbable to probable | 0.97 | |

| Impossible to possible | 0.90 | |

| Purchase intention | 0.95 | |

| How likely are you to purchse this jersey? | ||

| Unlikely to likely | 0.95 | |

| Imporbable to porbable | 0.97 | |

| Impossible to possible | 0.87 | |

| Team identification | 0.93 | |

| I consider myself to be a “real” fan of the Houston Rockets | 0.81 | |

| I would experience a loss if I had to stop being a fan of the Houston Rockets | 0.92 | |

| Being a fan of the Houston Rockets is very important to me | 0.97 |

| Relationship | Results | |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | (a) display of mascot → website satisfaction | Reject |

| (b) display of mascot → revisit intention | Reject | |

| (c) display of mascot → purchase intention | Reject | |

| H2 | (a) social presence and engaement play a serial mediating role in the relationship between mascot and website satisfaction | Accept |

| (b) social presence and engaement play a serial mediating role in the relationship between mascot and revisit intention | Accept | |

| (c) social presence and engaement play a serial mediating role in the relationship between mascot and purchase intention | Accept | |

| H3 | (a) the moderating role of high team identifiaction in the relationship between animated mascot and website satisfaction | Reject |

| (b) the moderating role of high team identifiaction in the relationship between animated mascot and revisit intention | Accept | |

| (c) the moderating role of high team identifiaction in the relationship between animated mascot and purchase intention | Accept | |

| H4 | (a) the moderating role of low team identifiaction in the relationship between static mascot andwebsite satisfaction | Reject |

| (b) the moderating role of low team identifiaction in the relationship between static mascot and revisit intention | Reject | |

| (c) the moderating role of low team identifiaction in the relationship between static mascot and purchase inteion | Reject |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, J.; Kim, D. The Impact of Animated Mascot Displays on Consumer Evaluations in E-Commerce. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060203

Oh J, Kim D. The Impact of Animated Mascot Displays on Consumer Evaluations in E-Commerce. Administrative Sciences. 2025; 15(6):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060203

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Jihyeon, and Daehwan Kim. 2025. "The Impact of Animated Mascot Displays on Consumer Evaluations in E-Commerce" Administrative Sciences 15, no. 6: 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060203

APA StyleOh, J., & Kim, D. (2025). The Impact of Animated Mascot Displays on Consumer Evaluations in E-Commerce. Administrative Sciences, 15(6), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci15060203