1. Introduction

In contrast to physical sustainable measures carried out in homes, the installation of a Home Energy Management System (HEMS) has no direct and immediate energy-saving effect. By giving the user sound feedback, a HEMS is meant to lead to changes in behaviour. This should result in energy savings. Because a HEMS responds to the user’s behaviour, it is different from the more common energy-saving measures in the home. A HEMS is primarily a resource that should enable the homeowner to change his or her own behaviour and, in this way, achieve energy savings at home. But because there is a diverse range of HEMSs, the user functions, complexity, and costs vary greatly from one to another.

A HEMS is “a simple system that gives easily accessible insight into and control over a household’s energy consumption” [

1]. Kobus complements this definition by giving specific meanings for ’insight’ and ’control’: “A device that gives computerised real-time (visual) feedback on gas and/or electricity consumption.” [

2]. This means that “HEMS” is a general name for a collection of different devices that give the user insight into the current energy consumption in their home. A HEMS must not be confused with a smart meter. A smart meter is a digital gas and electricity meter which can not only be read on-site, but with which the data can also be sent to the energy supplier. In the Netherlands, the research context of our study, smart meters do not include any visualisation, monitoring, or management system [

3]. In the UK, installations of smart meters are combined with installations of in-home displays, being studied by Darby [

4]. These displays can take different forms, and it is up to the energy supplier to choose what type of display they provide the households with their smart meter.

There are many different types of HEMS which differ in a variety of areas. The method of use can differ greatly according to the type of user interface: compatibility with an app, a website, or an in-house display, for example. Consumption can be displayed in different ways, but the functions of a HEMS can also vary from one type to another. Some systems are self-learning; others can be linked to solar panels, enabling them to monitor energy yields, while yet others can analyse a user’s consumption and compare it with that of other users. HEMS are offered by various suppliers. Energy suppliers in different European countries have developed their own type of HEMS which are frequently offered in combination with a contract with the same energy supplier [

5].

This diversity of features, display types, and suppliers results in devices with differing levels of detail and different price classes. Comparison websites in the Netherlands distinguish nearly 50 different types that a consumer can choose from [

6,

7]. Although smart meters are not the same as HEMS, HEMS are often supported by smart meters. On various occasions, smart meters have been called into question in the Netherlands, in TV programmes such as Kassa [

8,

9], and Internet forums such as ’wijvertrouwenslimmemetersniet’ (we don’t trust smart meters). This also comes up sporadically in the literature [

10]. Privacy, possible health risks, and the degree of mistrust in government and energy suppliers play important roles in this resistance. The resistance prompts the question of whether this fear and resistance also exists among some homeowners in relation to the use of a HEMS.

All these differences make it difficult to talk about ’a HEMS’. Person A might associate a HEMS with an elaborate self-teaching device, which is accessible through an app, can be operated remotely, transfers measurement data from several rooms, and is connected to specific devices in the home. Person B might visualise a HEMS as a simple display on the wall that just shows the ‘real-time’ readings from the smart meter. Both people would be referring to a HEMS, although these could be two totally different devices as regards their features, complexity, and costs.

A HEMS gives insight into the resident’s behaviour regarding energy use. When this is linked to the appropriate feedback, the resident is in a position to change his or her behaviour. This should result in reduced gas and/or electricity consumption, and therefore, lower costs, contributing energy saving targets.

Various studies and experiments have been conducted in the Netherlands with different types of HEMS. A number of experiments with different devices by energy network supplier Stedin produced varying results [

11]. For example, in two experiments, savings of six and nearly nine per cent were measured [

12,

13]. Perich and Van Dam specifically observed a declining effect over time, although this will certainly not be true of all types of residents [

1,

8]. Chen et al., explored the web dashboard engagement during a year-long experiment using an electricity use feedback system by users of campus apartments [

14]. Their results indicate that 90% of dashboard activity was undertaken by 50% of the participants, and that website engagement was more likely in mid-day and more effective in combination with email reminders.

Strömbäck et al., did research on the potential gains and limits of various feedback and price systems made possible by smart meter technologies [

15]. After comparing 100 pilots involving more than 450,000 residents, they concluded that, on average, pilots using what are called in-house displays (IHD) deliver the greatest energy savings. Savings varied between three and 19 per cent, and the level was further shown to depend on environmental variables such as a household’s average consumption, the location, and the feedback provided, among other variables. According to them, success depends directly on maintaining the consumer’s commitment. They conclude that an approach using a combination of resources and methods obtains better long-term results than a stand-alone approach. In addition, a system that provides several types of information is often better than systems with just one type of information. They emphasise that results could be obtained by adding resources and information over time, thereby giving more detailed feedback.

Various classifications and associated approaches have been developed to persuade different types of residents to adopt sustainable measures in their homes [

16,

17,

18]. Commissioned by the Municipality of Rotterdam, W&I Group studied ways in which homeowners can be prompted to take energy-saving measures [

19]. They state that three factors play a role in the segmentation of this target group: gender, age and life phase. They also distinguish five chronological phases in which a homeowner can find himself or herself. A homeowner begins with phase 1, i.e., ’without interest’ and, after going through the phases ‘is open to it’, ’has an intention’, and ’takes action’, finishes with phase 5, i.e., ’takes a number of measures’.

These studies give an indication of possibly important factors in a HEMS target group classification. However, these factors are focused on sustainability in a way that is too general. Few studies have focused on the target group classification of HEMS explicitly. When this aspect has been looked at, it has only been among current users of HEMS [

1,

15]. There is limited literature available on HEMS users. It is possible that in the examples described, the user’s expectations and wishes were not in line with the operational features of the HEMS. Strömbäck et al., investigated how characteristics of participants played a role in the pilots studied. Most classifications were made on the basis of characteristics of installations in the dwelling, such as the type of heating and cooling system [

15]. In addition, classifications were made based on characteristics of residents and their homes, such as age, income, size of household, type of dwelling, and surface area of dwelling. They conclude that these classifications of residents did not produce any improved results, unless the presence of large installations in the dwelling was taken into account. They do state that it is noticeable that the wishes and ideas of the residents themselves were rarely examined, but only their installations and their resident’s profile. Van Dam also dedicates part of her research based on case studies to the classification of HEMS users [

1]. She identifies five clusters of users. These are the techie, the one-off user, the manager, the thrifty spender, and the joie de vivre. These five characters differ in their motives for using HEMS and taking part in the case study, their affinity with technology, the extent to which they used the HEMS, and the extent to which they focused on technical savings or savings through behaviour changes; they also differ as to whether their interest in HEMS was more short- or long-term, and in their specific requirements relating to the HEMS. All participants used a HEMS in their home for a number of months. It is not clear whether homeowners who have never used a HEMS are also to be included in these five clusters. It is also noticeable that privacy plays no significant role in any of the clusters.

Certain factors such as the degree of affinity to technology, which appears in the research by Van Dam [

1], do not emerge as decisive factors in existing general target group segmentations for adopting sustainable measures. Therefore, these target group segmentations do not appear to be directly applicable to the users of HEMS.

Because the homeowner personally has a clear role to play in the success of a HEMS, it is crucial that the HEMS meet the user’s needs, as otherwise there is a strong chance that he or she will not use the HEMS Classifications of homeowners in relation to taking sustainable measures. A study that focuses specifically on a classification of homeowners which also includes homeowners who do not yet have experience of using HEMS could therefore be of added value.

The aim of this study is to contribute towards the effective use of HEMS. In order to arrive at an effective approach, more information is needed about the various identifiable types of homeowners in relation to the use of HEMS. In order to address this knowledge gap, we posed the following research question: How can homeowners be classified on the basis of their perceptions, attitudes, and behaviour in relation to the use of Home Energy Management Systems (HEMS)?

This study employed both a qualitative and a quantitative approach to answering the research question. The views of homeowners on the use of HEMS were studied using the Q-method. The research method is further explained in

Section 2. The third section addresses the findings, resulting in five different types of homeowners. This is followed with a discussion in and conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

The Q-method was developed to enable researchers to understand people’s views in relation to a given subject [

20]. The basic idea behind the Q-method is that a view has to be understood from within the individual subject. This is done by having the subject (the homeowner) react to various propositions related to the topic, and then looking at the positions (i.e., reactions to propositions) adopted by the subject. In order to draw up these propositions, researchers first collect as many statements as possible that exist regarding the use of HEMS, called ’Concourse’. They then make a representative selection of these statements (Q-statements) [

20]. For the next step, a group of homeowners has to be selected in such a way that the greatest possible diversity of views can be expected (Selection of respondents). Each respondent then ranks the various statements (Q-sorting). By subsequently correlating and factoring the positions of this group of individuals, coherent systems of positions can be brought to light which indicate shared views within subgroups of residents of single-family homes (Q-analysis). In this way, the Q-method reveals the different views that are held by homeowners in relation to the use of HEMS [

20]. SPSS was used for the data analysis.

Based on academic literature, newspaper reports, and internet sources, an initial list was drawn up of 164 statements related to the use of HEMS. Because there is no theoretical framework into which the list of statements can logically be fitted, it was decided to choose an unstructured q-sample. By placing related statements together inductively, eight categories of statement types were ultimately formed (

Table 1). Duplicated statements were then eliminated, and propositions that had approximately the same connotation were combined. This left a selection of 58 statements. The provisional design of the Q-set was tested by six trial subjects to verify the completeness of the set and to correct any mistakes in the instructions to respondents. Changes were made to the formulation of some statements based on the feedback, and the number of statements was cut to 48 in order to reduce somewhat the complexity for the respondent. This resulted in the final set of statements in

Table 2.

To find a group of homeowners as respondents that was as diverse as possible, the survey was carried out among homeowners living in various different neighbourhoods of Rotterdam. Based on the criteria percentage of single-family homes, construction year of the dwelling, age and education level of the main resident, average electricity supply, and average gas consumption, seven neighbourhoods were selected which provided a diverse reflection of the owners of single-family homes. In these neighbourhoods, homeowners were telephoned in order to try and recruit them as participants in the survey. A total of 41 homeowners agreed to take part.

The literature review showed that HEMS can vary greatly from one system to another. It was important for the respondents to have the same idea of what a HEMS is. For this reason, the instructions for respondents gave a brief explanation of the key function of a HEMS, i.e., that a HEMS measures the amount of energy the dwelling uses and gives the user feedback on this. The instructions also provided examples of the various functions that a HEMS can have. The term HEMS was not used for the survey, but instead, the Dutch term ’Energiemonitorsysteem’ (Energy Monitoring System, EMS).

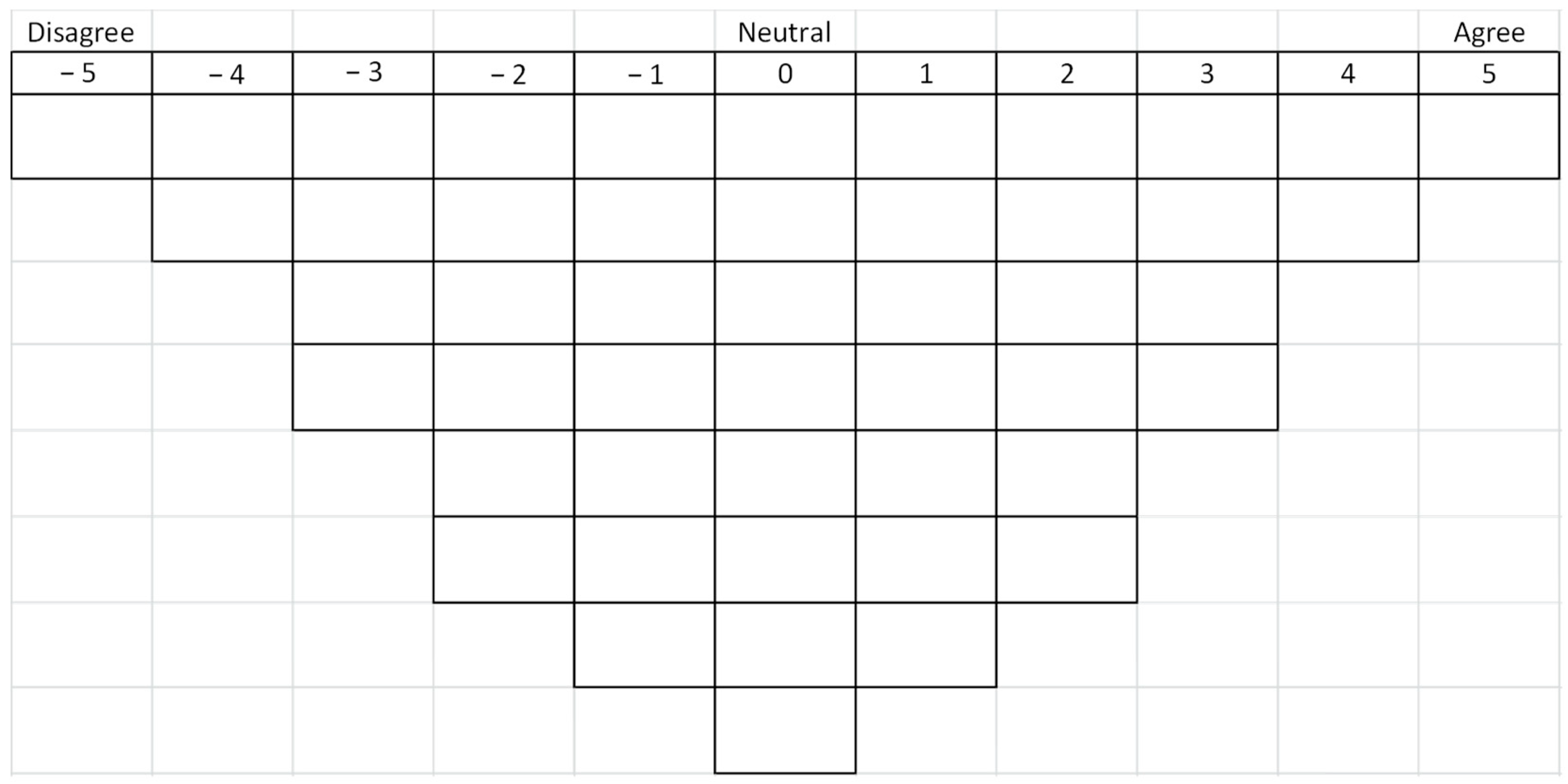

During the survey, respondents had to place each statement in one of the 48 boxes on the score sheet using 48 cards with the statements. A score sheet was used with a fixed distribution from “very strongly agree” (score 5) to “very strongly disagree” (score-5) (

Figure 1). Due to the fixed distribution, the participants were obliged to give a specific score to a limited number of statements. The aim of this distribution is for respondents to consider the statements in relation to the most extreme statements. All respondents were asked to elaborate on the statements they most strongly disagreed with and most strongly agreed with. First, the respondents had to divide the cards into statements they agreed with, they disagreed with, and they found neutral. Then, they had to rank the statement they agreed with from 5 to 1, and rank the statements they disagreed with from 5 to 1. Next, they had to the rank the statement they first ranked as neutral.

Where possible, the survey was completed in the presence of the researcher. This had the advantage that unclear points could be explained and questions could be put directly to the researcher. Because some participants said that they preferred to complete the survey in their own time, a guide was written to enable participants to do the survey independently. By subsequently making an appointment to pick up the survey, at which time questions could be asked if necessary, researchers tried to make the exercise as clear as possible.

Before the factor analyses were conducted, the data were first validated. Of the 41 respondents, two had not filled in the Q-sort completely or had not filled it in seriously. They were eliminated from the dataset. Of the other 39 respondents, not all of them kept to the model diagram. These respondents had completed the survey seriously, however, and were therefore retained in the dataset.

3. Results

The sample of 39 respondents scored diversely for the criteria of gender (19 men and 20 women) and age (before 1950: 4; 1950–1959: 7; 1960–1969: 10; 1970–1979: 8; 1980–1989: 9; 1 unknown). The size of the household is on average 3 persons. All respondents live in single-family dwellings. The year of construction of the dwellings is quite diverse, ranging between before 1945 (3) to after 2010 (1). Twenty-eight respondents are educated at higher education and university level, making them significantly different from the whole population. Twelve respondents had a HEMS, of whom 6 had a HEMS provided by the energy supplier. A relatively large number of respondents considered that they and their homes are quite sustainable. It is possible that highly-educated people are more willing to take part in this type of study than less well-educated people.

In the correlation matrix between the q-sorts of the respondents, mainly positive relationships were found. This means that, in general, there is more consensus between the q-sorts than clear contrasts. This led to the expectation that propositions could be found with which virtually every respondent either agrees or disagrees.

In order to obtain a statistically-sound answer to this question, a t-test was carried out of the average scores per proposition. By subsequently investigating whether the propositions with the highest averages also had the fewest respondents who awarded an opposite value to the proposition, it can be determined whether there are propositions with which the entire sample agreed or disagreed.

All respondents agreed with one proposition and they all disagreed with four propositions (

Table 3). A large number of homeowners in the sample are extremely energy-conscious. There are also people in the sample who have absolutely no interest in their energy consumption. However, this group of people is so small that this opinion is not clearly expressed. It is possible that people who are not interested in their energy consumption were less inclined to take part in the survey because they have less affinity to the subject.

3.1. Factor Analysis

In order to find shared views among respondents, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy and the Bartlett’s test of sphericity indicated that the data set was adequate to conduct a PCA. In SPSS, several PCAs were conducted to determine how many shared views could be distinguished in the sample.

Table 4 gives the propositions with the highest and lowest factor scores. This shows that a majority of the respondents have a fairly positive image of the use of the HEMS. The majority of people in the sample expect a HEMS to have a positive influence on controlling energy consumption in the home, and they see no major drawbacks from using one.

In order to increase the interpretability of factors, the factors were orthogonally rotated in the direction of a simple structure. For this purpose, a PCA was performed in which varimax rotation was applied so that principal components were distinguished that did not correlate with each other.

Five was the highest number of components with at least three respondents on each component weighted with a coefficient greater than or equal to 0.50. However, the question was whether the fifth component really added much in comparison with the fourth and the third components. For this reason, the PCA based on five components was compared with the PCAs based on four and three components. The total explained variance and the interpretation of the factors were decisive for all criteria. A PCA with five components was therefore chosen as the optimal solution. On the basis of this analysis, five different shared views were found: the ’optimists’, the ’privacy-conscious’, the ’technicians’, the ’sceptics’, and the ’indifferent’.

3.2. Target Group Segmentation

To determine the meaning of the various components, the propositions with the highest and the lowest factor scores were analysed. These are specifically the propositions that were important to the respondents and/or those that they agreed or disagreed with most.

The first component describes a group that is very positive about HEMS. These ’optimists’ expect that the advice a HEMS gives them helps to handle their energy consumption more intelligently and control this consumption better. Respondent 31 says: “Being able to handle my energy consumption more intelligently is the main reason for me to buy one.” Respondent 24: “I think that a HEMS can indicate more effectively when it is best for me to intervene; at the moment I don’t understand it very well.” This group is also curious to know the prognoses that a HEMS can provide regarding future energy consumption. They would greatly appreciate the useful services that a HEMS can provide, such as switching off the heating if you have forgotten to do so. Respondent 18 explains: “So that you can still switch your heating off when you’ve forgotten to do so. And switch it on if necessary when you come back from holiday.” These ’optimists’ are not afraid of potential drawbacks presented by a HEMS. They dismiss as ridiculous the possibility that a HEMS would actually cause higher energy consumption. The ’optimists’ are convinced that a HEMS does not have to have an adverse effect on the level of comfort in the home. In addition, they think it is nonsensical to suggest that dangerous radiation can be emitted, or that the HEMS is linked to major security risks. The ’xoptimists’ are certainly consciously involved with energy consumption, and they see a HEMS as a handy aid to deal more efficiently with their energy consumption. Some of them already have a HEMS, while others do not, but are thinking about it. For an ’optimist’, a HEMS is a good motivator to save even more energy in the home, and as such, a HEMS would fit in well with the lifestyle of an optimist.

’Privacy-conscious citizens’ are people who take an interest in their energy consumption, but who have concerns regarding the use of a HEMS. They believe that HEMSs can be hacked. They find this disturbing, because they believe that the data collected can be misused. Respondent 9 explains this as follows: “Hacking is a major weakness of current electronic devices. Research shows repeatedly that such devices are insufficiently protected. This puts privacy under pressure. It’s a bigger risk than people realise.” This is also one reason why people in this group do not want to compare their energy consumption with that of others in the neighbourhood. At the same time, the ‘privacy-conscious citizens’ recognise that a HEMS could be useful in some ways. They think that a HEMS can be helpful for overviews, and that it could help them to have more control over consumption in the home. If they used a HEMS, they could become accustomed to checking it regularly. They would most like to have a HEMS in a permanent place in their home. ‘Privacy-conscious citizens’ say that they would not quickly tire of a HEMS. They believe that ultimately you have to save energy yourself by means of the choices you make, based on the information provided by a HEMS. A HEMS will not bring about savings by itself. They are not interested in being able to program in advance when a device or appliance needs to be switched off. ‘Privacy-conscious citizens’ could potentially be HEMS users. They see the usefulness of a HEMS, but they have concerns regarding security. If they were to use a HEMS, the system would have to be proven to be secure, preferably not being linked to an energy supplier, and hassle-free.

The ’technicians’ group consists of people who are fairly technically minded. This is a group that sees a HEMS as a fun gadget, and therefore, wants to have access to a HEMS in several ways. They are interested in the numbers and graphics displayed by a HEMS, or even find them appealing. Respondent 19 articulates this as follows: “Whether or not a HEMS brings savings, colourful graphics and numbers in the living room: What’s not to like?” With their technical affinity, this group would have no trouble programming a HEMS themselves. They find it nonsensical to think that a HEMS could be dangerous due to radiation, and they are also not afraid of their HEMS being hacked. The ‘technician’ thinks that you can only save money with a HEMS if you still use a lot of energy, and technicians place themselves in the group that could still make some savings. This is in line with the answer they gave to the question of how energy-efficient they considered their own behaviour to be: the ’technicians’ classify their behaviour in a range from “not very energy-efficient” to “reasonably energy-efficient”. Technicians do not expect that saving with the help of a HEMS would lead to conflicts with the other members of their household. It would not trouble them if they were the only person in their household who dealt with energy consumption. Furthermore, they think that making savings does not have to lead to a reduction in comfort, so they see no reason for any conflict. This ’technicians’ group would be very happy to use a HEMS. The question is whether the ’technician’ could continue to be fascinated by a HEMS for long enough. Somewhat more advanced HEMSs could therefore be of interest to this group.

The fourth group, called the ’sceptics’, is somewhat more sceptical towards HEMS. This groups expects the learning effects of a HEMS to be fairly quickly exhausted. Respondent 11 explains: “I do make an effort to be energy-conscious, and at a certain point you reach the limits of what you can do. The same probably applies to a HEMS, too.” ’Sceptics’ prefer to keep control themselves; they do not want others to have access to their data. They would also find it very annoying to be constantly confronted with their consumption. Respondent 22 says: “I’m suffering a bit from information overload. Every month is interesting, but every day is really too much for me.” This group would therefore not be eagerly anticipating extra functions such as a weather radar. In addition, they find the purchase costs of a HEMS fairly high. As regards the effect of a HEMS, they do think that it can reduce energy consumption, and they would appreciate a number of handy HEMS functions, such as automatically switching off the heating. A ’sceptic’ would not be easily persuaded to use a HEMS. However, if the right preconditions are created, a HEMS could possibly be of interest. Important conditions are that users should be able to determine which information the HEMS provides and how frequently they see that information, and there should also be a guarantee that they themselves are the owners of their data.

The ’indifferent’ group is a group that has little interest in a HEMS. They consider that a HEMS is actually too technical and would have absolutely no interest in being able to export and further analyse information. Respondent 17 says: “I just wouldn’t do that; I have no interest at all in it.” A HEMS is not seen as an attractive gadget. This lack of interest in a HEMS also emerged in the unanimous response to the question about taking part in a pilot with a HEMS. This is the only group of which every member said they did not want to be approached about a pilot using a HEMS. This indifference is not the result of any fear of security risks, worries about potential conflicts at home, or the expectation that a HEMS would reduce comfort. It is not true that those in this group have no interest in their energy consumption, but compared with the other groups, they disagree less strongly with this proposition. If they purchased a HEMS, it would above all have to be simple and positioned in a fixed location, and they would mainly find it useful because of the overviews it provided.

4. Discussion

A HEMS is primarily a device that gives homeowners feedback on their energy consumption, and thus, puts them in a position to change their behaviour and thereby achieve energy savings at home. Studies into target group classification of HEMS only researched current users of HEMS [

1,

15]. Classifications of home-owners and tenants to persuade them to adopt sustainable measures in their homes [

16,

17,

18] are too general to classify HEMS users and to customize HEMSs to their needs.

’Privacy-conscious citizens’ could be a typical Dutch phenomenon, caused by debates about privacy concerns of smart meters in the Netherlands [

8,

9]. A specific group based on shared views of privacy and security could be non-existent in other countries. People who are fairly technically minded, the ‘technicans’, are also seen by other authors, e.g., Van Dam [

1] as a specific group. Indeed, HEMSs could appeal to the growing group of people that like all kinds of electronic gadgets.

Some authors stipulate that if the energy consumption is already very low, e.g., for households living in energy poverty, using HEMS will not make a difference. Also, people may not be willing to use a HEMS, having a lack of awareness of their energy consumption [

21,

22]. In this respect, the so-called ’indifferent group’ might be quite huge, depending on the income of the household, dwelling type, and age. Darby recognises that not all people are able or willing to use HEMS [

4]. She acknowledges here awareness of (1) Customers that do not care about their consumption, (2) Customers who feel that they already have reached the limit of what they can do to reduce their energy consumption, and (3) Customers living in dwellings that make it difficult and expensive to reduce their energy consumption. Van Elburg argues that sophisticated real-time web services on PC, tablet, and smartphone are potentially powerful to help reduce energy demand, but more so with already committed and technology minded subsets of the population [

9]. Less committed and/or less technology-minded consumers or less capable consumers prefer the accessibility of a simple yet visually appealing in-home display. Many others observe from their studies on consumption feedback that there is a need to customize the information to the intended users [

1,

2,

23].

5. Conclusions

The respondents appear to be generally quite energy-conscious and have a relatively positive view of the usefulness of a HEMS. A large majority of them disagree with the possible adverse effects of HEMS. Factors that emerge among the homeowners who appear to be open to the idea of using a HEMS are energy awareness, confidence in the effect of the HEMS, appreciation of the advice provided by a HEMS and, above all, no worries about possible drawbacks such as security and radiation risks or conflicts with other members of the household. The factors that make homeowners less keen to use a HEMS are high purchase costs, a lack of technical affinity, and concerns about security and privacy.

Five different types of homeowners have been found: the optimists, the privacy-conscious, the technicians, the sceptics, and the indifferent. This target group classification in relation to HEMS use offers first of all a basis of shared views among homeowners which must be taken into account. This segmentation can be used as input for a way in which e.g., a municipality can offer HEMSs that are in line with the wishes of the homeowner. Also, HEMSs could be tailored to those groups. Future research could benefit from designing different HEMSs for those groups, and to compare their effectiveness in the field to gain a more detailed understanding of the effect of certain design variations and interactions with users of HEMSs.

The survey was carried out among homeowners in the municipality of Rotterdam. There is no reason to presume that homeowners in Rotterdam use HEMSs significantly differently from homeowners in other cities. The results of this survey are therefore also applicable to homeowners in other cities. However, it is essential not to take for granted that the classification covers every viewpoint, as the sample is too highly-educated and too energy-conscious for that. Future research could address less educated and less energy-conscious people. Furthermore, the frequency of the found types of homeowners and also tenants has to be researched to know if the saved energy depends on the type of homeowners and the design of the HEMS.