Compliance with the Verification of Environmental Technologies for Agricultural Production Protocol in Ammonia and Particulate Matter Monitoring in Livestock Farming: Development and Validation of the Adherence VERA Index

Abstract

1. Introduction

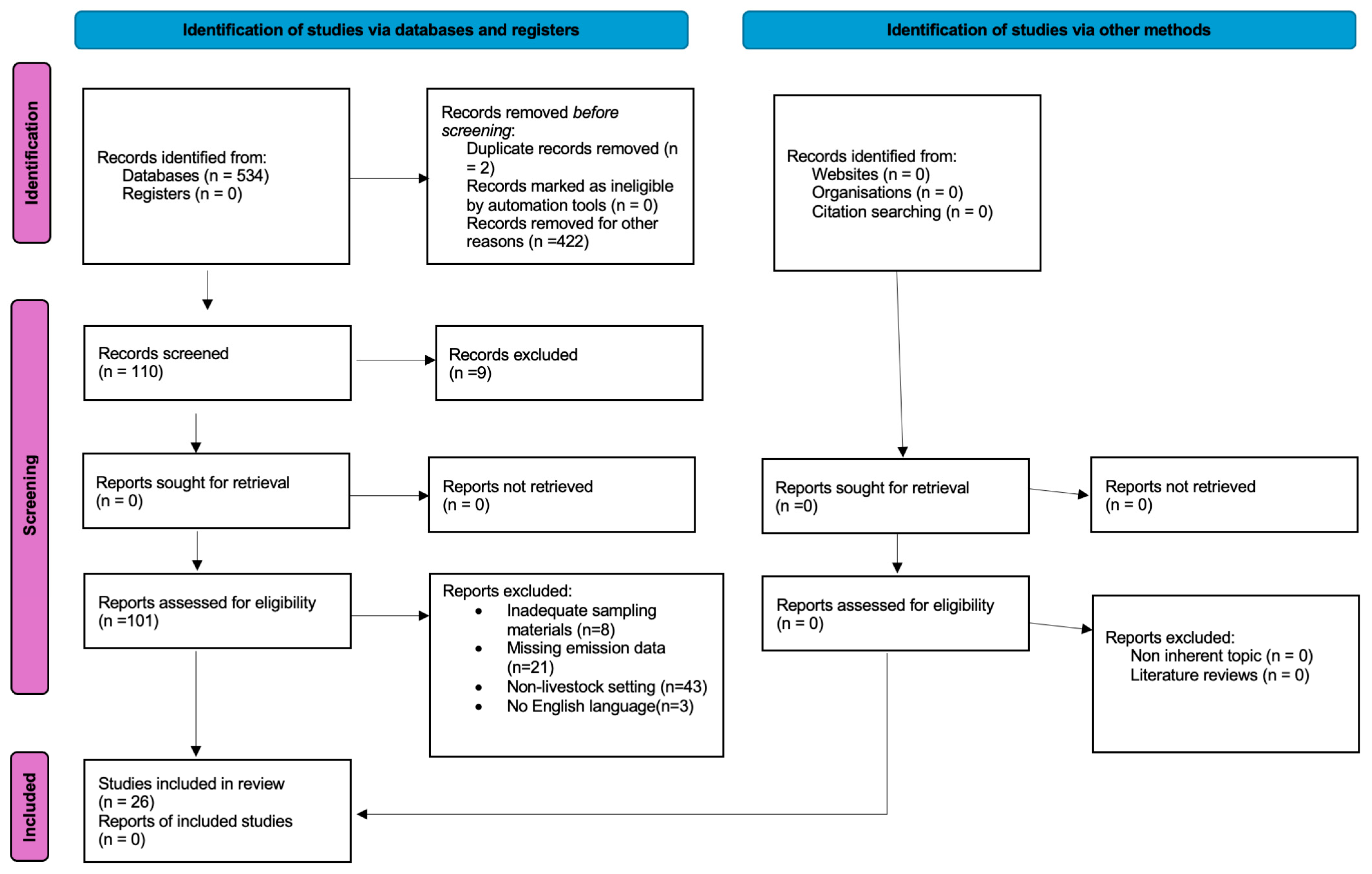

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Evaluation of Adherence to the VERA Protocol

2.4. Adherence VERA Index (AVI)

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics of the Monitored Sites

| Authors, Year | Place | Farm Type | General Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animals: -Number -Type | Feed, Type and Amount | Floor and Manure Management | Size Dimension (m) | Other Site Characteristics (Lighting, Temperature and Humidity, Ventilation) | |||

| 1. Choi et al., 2023 [25] | Jangseong City, South Korea | Commercial pig farm | -≈9000 -pig | NR | -Floor: Slotted floors -Manure management: liquid manure pit recirculation system | 75 × 13 × 4.7 m | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: HOBO probe -Ventilation: mechanical ventilation systems, monitored by flow hood (Model Testo 420). |

| 2. Ji Qin Ni et al., 2012 [26] | West Lafayette, USA | Commercial egg production farm | -NR -Hen | NR | -Floor: NR -Manure-management: slanted boards behind the cages | Area: 10,629.5 m2 | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: RH/T sensors and thermocouples -Ventilation: natural from the attic through three temperature-adjusted V-shaped baffled ceiling and mechanical from 55 exhausted fans |

| 3. Jihoon Park et al., 2019 [39] | Republic of Korea | Five commercial swine farms and five poultry farms | -NR -Finishing pig, Broiler and Laying hen | NR | Floor: slatted floors Manure management: manure storage and manure composting facilities. | 7139 m2 | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: Indoor air quality meter -Ventilation: Natural and mechanical ventilation. |

| 4. Qian-Feng Li et al., 2013 [41] | North Carolina, United States | Commercial egg production farm | -NR -Chickens and turkeys | NR | NR | NR | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: simultaneously monitored as part of the National Air Emissions Monitoring Study. -Ventilation: six mechanically ventilated houses and three naturally ventilated houses. |

| 5. Dan Shen et al., 2019 [33] | Zunyi city of Guizhou province, China | Swine barns | -352 -Nursery pigs -152 -Fattening pigs | Nursery pigs pelleted feed manually; the total amount of feed was 0.5 kg daily each. Fattening pigs 4.5 kg of pelleted feed using an automatic feeder | -Floor: slatted floor. -Manure management: manure down the floor and stored approximately 3 months | 26.0 m × 15.0 m | -High-rise nursery barn (HN) -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: Heat preservation lamp -Ventilation: mechanical ventilation system consisting of exhaust fans -High-rise fattening (HF) -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: No Heat preservation lamp -Ventilation: natural and mechanical |

| 6. Y. Zhao et al., 2015 [37] | Midwest, United States | Poultry house | -200,000 -Laying-hen | NR | -Floor: Slatted floor -Manure management: manure belts in all hen colonies and conveyed the accumulated manure out of the house | NR | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: type-T thermocouples and RH with capacitance-type humidity sensors -Ventilation: mechanical ventilation |

| 7. Yu Wang et al., 2020 [38] | Yanqing District of suburb Beijing, China. | Poultry house | -100,000 -Laying hen | Feed by rows of troughs, and water via nipple drinkers. | Floor: 2 slatted floors. Manure management: collected on wide plastic belts beneath each tier of cages. | 115 × 14 × 7.5 m | -Lighting: The Lighting period lasted from 4:00 to 20:00 daily. -Temperature and humidity: temperature-controlled sensors Ventilation: negative pressure ventilation system |

| 8. Yaomin Jin et al., 2012 [42] | State of Indiana, in the United States Missouri, Columbia | Swine finishing farm | -8000 -Pigs | NR | -Floor: fully slatted -Manure management: stored in a deep pit under the floor for about 6 months before removal. | 2 Farms: 126 × 25.5 m | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: NR -Ventilation: each room mechanically and naturally ventilated |

| 9. Li Q.-F. et al., 2013 [43] | North Carolina. Monitoring was recorded from 24 Sept 2007 to 27 October 2009 | Eggs production facility | -103,000 -Hy-Line W36 hens | NR | Floor: NR Manure management: skid loader | 177 × 18 m | Lighting: NR Temperature and humidity: temperature sensors Ventilation: mechanical and naturally ventilation |

| 10. Casey et al., 2012 [44] | Site OK4B was in the Panhandle region of Oklahoma (USA). | Sow stalls | -1200 -sows in six rows of sow stalls | Feed truck deliveries. | -Floor: slatted and concrete -Manure management: shallow pit allowing to drain in an anaerobic lagoon | 16 rooms: 129 × 18 m | Lighting: NR Temperature and humidity: temperature sensors Ventilation: mechanical |

| 11. Li et al., 2018 [45] | Zunyi city of Guizhou province, monitored from April1st to April 20th, 2017. | Swine farm: nursery and fattening stables | -Five commercial swine farms and five poultry farms were selected for monitoring. | Fed manually. | -Floor: slatted -Manure management: underneath the slatted floor and stored for about three months | 26 × 15 m | -Nursery Farm Lighting: Insulation lamp -Temperature and humidity: Sensors -Ventilation: No ventilation in nursery -Fattening Stable Lighting: Not insultation lamp -Temperature and humidity: Sensors -Ventilation: Mechanically |

| 12. Hayes et al., 2012 [32] | Iowa states from June 2010 to December 2011. | Two Aviary houses | -50,000 -hens (Hy-Line Brown) | Feed manually | -Floor: open litter -Manure management: 3 levels with manure belts and manure drying air duct | 167.6 m × 19.8 m | -Lighting: Fluorescent lamp used for 16 h light period -Temperature and humidity: Sensors -Ventilation: Mechanically |

| 13. Von Jasmund et al., 2020 [30] | University Bonn from March to July 2019 | Fattening stable | -11 -weaned and docked pigs | Feed a libitum on a wet feeder, including two nipple drinkers | Floor: Partly slatted concrete Manure management: NR | 6.00 × 2.54 m | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: Tinytag sensor -Ventilation: Mechanically |

| 14. Wu et al., 2020 [46] | Beijing, China in May 2017 | Dairy farm | -300 -cows | Feed manually | -Floor: Brick and a cowshed with a solid concrete floor. -Manure management: scrape every day and store in a vacant cowshed | NR | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: thermo-anemometer -Ventilation: mechanically |

| 15. Joo et al., 2015 [27] | Washington State, located in the United States Pacific Northwest | Dairy barns with curtains | -1250 -Dairy cows: B1: 400 cows B2: 850 cows | NR | NR | B1: 183 × 31 m B2: 213 × 39 m | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: RH/T sensor -Ventilation: mechanically |

| 16. Jin et al., 2010 [47] | Indiana, USA | Dairy farm | -3400 -Dairy cows | Feed and water provided at libitum | -Floor: a raised platform with beds and a lower walkway made of iron slat. -Manure management: with scrapers and sent to a reception pit | 472 m × 29 m | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and relative humidity: RH/T sensor -Ventilation: mechanically |

| 17. Garcia et al., 2013 [48] | California located in the Central Valley | 13 large dairies | -130,000 -Lactating cows | NR | NR | Area: 120–1320 m2 Median Area: 610 m2 | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: California Air Resources Board -Ventilation: mechanically |

| 18. Dai et al., 2018 [35] | South China (113°04.888′ E, 28°11.247′ N), | Hog houses | -600 -piglets | NR | -Floor: ground slatted floor with -Manure management: 4 methods: manual waterless, automatic waterless, automatic water flushing and fermentation bed. | 20 × 10 × 3.5 m | -Lighting: natural light -Temperature and humidity: T sensors -Ventilation: Naturally and mechanically ventilated |

| 19. Shepherd et al., 2015 [36] | US Midwest | 3 house egg production systems with a 200,000-hen capacity; | -NR -Lohmann white hens | Feed twice per day in each house Drinking ad libitum | -Floor: NR -Manure management: belts | CC: 141.2 × 26 m AV: 152.2 m × 21.3 m EC: 154.2 × 13.7 m | -Lighting: 12 h light and 12 h dark -Temperature and humidity: RH/T sensors -Ventilation: mechanically |

| 20. Tamar Tulp et al., 2024 [29] | Friesland, Netherlands | Dutch commercial dairy | -250 -cows | Feed manually | -Floor: NR -Manure management: NR | About 27,000 m2 | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: RH/T sensor -Ventilation: Mechanically |

| 21. Schmithauesen et al., 2018 [34] | Kleve, Germany | Dairy barn | -96 -lactating cows | Feed manually | -Floor: Slatted floors -Manure management: an under-floor concrete slurry storage system | 68 × 34 m. Height from 5.15 to 12.35 m. | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: an outside weather station at a height of 6 m on the rooftop -Ventilation: Mechanically and naturally |

| 22. Zenon Nieckarz et al., 2023 [49] | Kraków, Poland | Commercial dairy cattle | -84 -dairy cows | TMR Feed | -Floor: NR -Manure management: NR | 10.39 × 54.87 m height from 3.82 m to 5.37 m | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: RH/T sensors -Ventilation: Mechanically |

| 23. W. Zheng et al., 2020 [31] | Midwest, United States | Commercial laying hen house | -425,000 -laying hens | NR | -Floor: halfway between the ground and ceiling, forming the top and bottom floors. -Manure management: a belt under each cage | 27.8 × 164.6 × 10 m | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: RH/T sensors -Ventilation: Mechanically |

| 24. Zhifang Shi et al., 2019 [28] | Henan, China | Dairy farms | -1450 -Holstein cows. | Feed manually with a mixed ration (TMR) | NR | Farm1: 72 × 31 × 7 Farm2: 72 × 26 × 6 Farm3: 96 × 27 × 7 | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: RH/T sensors -Ventilation: Naturally |

| 25. Jannat A et al., 2025 [50] | Northen Colorado, USA | Dairy farms | -6000 -lactating cows | Feed manually every night | -Floor: NR -Manure management: vacuum machine pulled by a tractor | NR | -Lighting: NR -Temperature and humidity: RH/T 2.5% logger sensors -Ventilation: forced ventilation and misting systems, |

| 26. Li et al., 2024 [40] | Hebei Province, Northen China | Low profile, cross ventilated dairy barn | -2400 -lactating cows | 4 Feed delivery alleys | -Floor: NR -Manure management: manure removal alleys renewed by a mechanical truck | 408 × 92 m | -Lighting: artificially with LED -Temperature and humidity: portable particulate monitoring unit (PPMU) and a portable gas monitoring unit (PGMU) Ventilation: two positive-pressure ventilation pipes |

3.2. NH3 and PM Monitoring Data by Animal Species

3.2.1. Swine Farms

3.2.2. Poultry Farms

3.2.3. Dairy Farms

3.3. Monitoring Methods and Data Quality

3.4. Application of the VERA Protocol Parameters in the Included Studies

3.4.1. Housing System Description

3.4.2. Measuring System

3.4.3. Sampling Conditions

3.4.4. Emission Estimation Methods

3.4.5. Secondary Parameters Related to Gaseous Emissions

3.4.6. Adherence to the VERA Protocol by AVI

- −

- Ventilation assessment (not measured or insufficiently described in a substantial proportion of studies)

- −

- Sampling strategies (limited information on sampler placement and measurement frequency)

- −

- Emission estimation methods (restricted use of tracer gases or directly measured airflow rate)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses |

| AVI | Adherence VERA Index |

| TEOMS | Tapered element oscillating microbalances |

References

- Van Damme, M.; Clarisse, L.; Franco, B.; Sutton, M.A.; Erisman, J.W.; Wichink Kruit, R.; van Zanten, M.; Whitburn, S.; Hadji-Lazaro, J.; Hurtmans, D.; et al. Global, regional and national trends of atmospheric ammonia derived from a decadal (2008–2018) satellite record. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 094041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook 2019; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/emep-eea-guidebook-2019 (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- European Topic Centre on Human Health and the Environment (ETC HE). ETC HE Report 2022/21: Emissions of Ammonia and Methane from the Agricultural Sector. Emissions from Livestock Farming; ETC HE: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. Available online: https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-he/products/etc-he-products/etc-he-reports/etc-he-report-2022-21-emissions-of-ammonia-and-methane-from-the-agricultural-sector-emissions-from-livestock-farming (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- International VERA Secretariat. VERA Test Protocol for Livestock Housing and Management Systems; (Version 3: 2018-09); VERA: Brooklyn, NY, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.vera-verification.eu (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Poteko, J.; Zähner, M.; Schrade, S. Effects of housing system, floor type and temperature on ammonia and methane emissions from dairy farming: A meta-analysis. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 182, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldini, C.; Borgonovo, F.; Gardoni, D.; Guarino, M. Comparison among NH3 and GHGs emissive patterns from different housing solutions of dairy farms. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 141, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, L.B.; Pieters, J.G.; Snoek, D.; Ogink, N.W.; Brusselman, E.; Demeyer, P. Reduction of ammonia emissions from dairy cattle cubicle houses via improved management- or design-based strategies: A modeling approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 574, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, W. Impacts of nitrogen emissions on ecosystems and human health: A mini review. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 21, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A.N. Technical note: Contribution of ammonia emitted from livestock to atmospheric fine particulate matter (PM2.5) in the United States. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 3130–3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ndegwa, P.M.; Joo, H.; Neerackal, G.M.; Harrison, J.H.; Stöckle, C.O.; Liu, H. Reliable low-cost devices for monitoring ammonia concentrations and emissions in naturally ventilated dairy barns. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 208, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyer, K.E.; Kelleghan, D.B.; Blanes-Vidal, V.; Schauberger, G.; Curran, T.P. Ammonia emissions from agriculture and their contribution to fine particulate matter: A review of implications for human health. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 323, 116285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Effects Institute. State of Global Air 2024; Health Effects Institute: Boston, MA, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources/report/state-global-air-report-2024 (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345329 (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Directive (EU) 2016/2284 on the reduction of national emissions of certain atmospheric pollutants. Off. J. Eur. Union 2016, L 344, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Directive 2010/75/EU on industrial emissions (integrated pollution prevention and control). Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, L 334, 17–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bjerg, B.S.; Demeyer, P.; Hoyaux, J.; Didara, M.; Grönroos, J.; Hassouna, M.; Amon, B.; Bartzanas, T.; Sándor, R.; Fogarty, M.P.; et al. Review of legal requirements on ammonia and greenhouse gases emissions from animal production buildings in European countries. In Proceedings of the 2019 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Boston, MA, USA, 7–10 July 2019; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovarelli, D.; Bacenetti, J.; Guarino, M. A review on dairy cattle farming: Is precision livestock farming the compromise for an environmental, economic and social sustainable production? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullo, E.; Finzi, A.; Guarino, M. Environmental impact of livestock farming and Precision Livestock Farming as a mitigation strategy: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 2751–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassouna, M.; Heglin, A. Measuring Emissions from Livestock Farming: Greenhouse Gases, Ammonia and Nitrogen Oxides; ADEME and INRA: Paris, France, 2016; Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01567208 (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2019rf/index.html (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- International VERA Secretariat. General VERA Guidelines: Verification of Environmental Technologies for Agricultural Production; VERA: Delft, The Netherlands, 2022. Available online: https://www.vera-verification.eu/app/uploads/sites/9/2022/03/GeneralVERAGuidelines-2022-final-version.pdf (accessed on 29 February 2024).

- Ni, J.-Q.; Erasmus, M.A.; Croney, C.C.; Li, C.; Li, Y. A critical review of advancement in scientific research on food animal welfare-related air pollution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 408, 124468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wu, J.; Zhao, X. Review of measurement technologies for air pollutants at livestock and poultry farms. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2019, 52, 1458–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insausti, M.; Timmis, R.J.; Kinnersley, R.P.; Rufino, M.C. Advances in sensing ammonia from agricultural sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 706, 135124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, L.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Jeong, H.; Park, J.; Hong, S.W.; Kwon, K.S.; Song, M. Ammonia and particulate matter emissions at a Korean commercial pig farm and influencing factors. Animals 2023, 13, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.-Q.; Chai, L.; Chen, L.; Bogan, B.W.; Wang, K.; Cortus, E.L.; Heber, A.J.; Lim, T.-T.; Diehl, C.A. Characteristics of ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, and particulate matter concentrations in high-rise and manure-belt layer hen houses. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 57, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, H.; Park, K.; Lee, K.; Ndegwa, P.M. Mass concentration coupled with mass loading rate for evaluating PM2.5 pollution status in the atmosphere: A case study based on dairy barns. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 207, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Sun, X.; Lu, Y.; Xi, L.; Zhao, X. Emissions of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide from typical dairy barns in central China and major factors influencing the emissions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulp, T.; Tietema, A.; van Loon, E.E.; Ebben, B.; van Hall, R.L.; van Son, M.; Barmentlo, S.H. Biomonitoring of dairy farm emitted ammonia in surface waters using phytoplankton and periphyton. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Jasmund, N.; Wellnitz, A.; Krommweh, M.S.; Büscher, W. Using passive infrared detectors to record group activity and activity in certain focus areas in fattening pigs. Animals 2020, 10, 792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Xiong, Y.; Gates, R.S.; Wang, Y.; Koelkebeck, K.W. Air temperature, carbon dioxide, and ammonia assessment inside a commercial cage layer barn with manure-drying tunnels. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 3885–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M.; Xin, H.; Li, H.; Shepherd, T.; Zhao, Y.; Stinn, J. Ammonia, greenhouse gas, and particulate matter emissions of aviary layer houses in the Midwestern U.S. Trans. ASABE 2013, 56, 1921–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Wu, S.; Li, Z.; Tang, Q.; Dai, P.; Li, Y.; Li, C. Distribution and physicochemical properties of particulate matter in swine confinement barns. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 250, 746–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmithausen, A.J.; Schiefler, I.; Trimborn, M.; Gerlach, K.; Südekum, K.-H.; Pries, M.; Büscher, W. Quantification of methane and ammonia emissions in a naturally ventilated barn by using defined criteria to calculate emission rates. Animals 2018, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Huang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, B.; Peng, H.; Qin, P.; Wu, G. Concentrations and emissions of particulate matter and ammonia from extensive livestock farm in South China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 1871–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, T.A.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; Stinn, J.P.; Hayes, M.D.; Xin, H. Environmental assessment of three egg production systems—Part II: Ammonia, greenhouse gas, and particulate matter emissions. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Shepherd, T.A.; Swanson, J.C.; Mench, J.A.; Karcher, D.M.; Xin, H. Comparative evaluation of three egg production systems: Housing characteristics and management practices. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Niu, B.; Ni, J.Q.; Xue, W.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Zou, G. New insights into concentrations, sources and transformations of NH3, NOx, SO2 and PM at a commercial manure-belt layer house. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kang, T.; Heo, Y.; Lee, K.; Kim, K.; Lee, K.; Yoon, C. Evaluation of short-term exposure levels on ammonia and hydrogen sulfide during manure-handling processes at livestock farms. Saf. Health Work 2020, 11, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, X.; Lu, Y.; Liang, C.; Shi, Z.; Wang, C. Annual dynamics of concentrations and emission rates of particulate matter and ammonia in a large-sized, low-profile, cross-ventilated dairy building. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.F.; Wang-Li, L.; Shah, S.B.; Jayanty, R.K.; Bloomfield, P. Ammonia concentrations and modeling of inorganic particulate matter in the vicinity of an egg production facility in Southeastern USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 4675–4685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Lim, T.T.; Ni, J.Q.; Ha, J.H.; Heber, A.J. Emissions monitoring at a deep-pit swine finishing facility: Research methods and system performance. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2012, 62, 1264–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.F.; Wang, L.; Wang, K.; Chai, L.; Cortus, E.L.; Kilic, I.; Bogan, B.W.; Ni, J.Q.; Heber, A.J. The national air emissions monitoring study’s Southeast Layer Site: Part II. Particulate matter. Trans. ASABE 2013, 56, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, K.D.; Cortus, E.L.; Heber, A.J.; Caramanica, A.P. Ammonia emissions from a pig breeder facility in the Oklahoma Panhandle. In Proceedings of the IX International Livestock Environment Symposium (ILES IX), Valencia, Spain, 8–12 July 2012; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wu, S.; Shen, D. Comparison of airborne particulate matter and ammonia concentrations from nursery and fattening stables in large semi-enclosed swine house. In Proceedings of the 10th International Livestock Environment Symposium (ILES X), Omaha, NE, USA, 25–27 September 2018; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yang, F.; Brancher, M.; Liu, J.; Qu, C.; Piringer, M.; Schauberger, G. Determination of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide emissions from a commercial dairy farm with an exercise yard and the health-related impact for residents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 37684–37698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Lim, T.T.; Ni, J.; Heber, A.; Liu, R.; Bogan, B.; Hanni, S. Aerial emission monitoring at a dairy farm in Indiana. In Proceedings of the 2010 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 20–23 June 2010; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.; Bennett, D.H.; Tancredi, D.; Schenker, M.B.; Mitchell, D.; Mitloehner, F.M. A survey of particulate matter on California dairy farms. J. Environ. Qual. 2013, 42, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieckarz, Z.; Pawlak, K.; Baran, A.; Wieczorek, J.; Grzyb, J.; Plata, P. The concentration of particulate matter in the barn air and its influence on the content of heavy metals in milk. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannat, A.; Johnson, A.; Manriquez, D. Air quality monitoring in dairy farms: Description of air quality dynamics in a tunnel-ventilated housing barn and milking parlor of a commercial dairy farm. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 8567–8581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Annotated Table Z-1: Permissible Exposure Limits; U.S. Department of Labor: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.osha.gov/annotated-pels/table-z-1 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Davidson, M.E.; Schaeffer, J.; Clark, M.L.; Magzamen, S.; Brooks, E.J.; Keefe, T.J.; Bradford, M.; Roman-Muniz, N.; Mehaffy, J.; Dooley, G.; et al. Personal exposure of dairy workers to dust, endotoxin, muramic acid, ergosterol, and ammonia on large-scale dairies in the high plains Western United States. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2018, 15, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neghab, M.; Mirzaei, A.; Jalilian, H.; Jahangiri, M.; Zahedi, J.; Yousefinejad, S. Effects of Low-level Occupational Exposure to Ammonia on Hematological Parameters and Kidney Function. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2019, 10, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neghab, M.; Mirzaei, A.; Kargar Shouroki, F.; Jahangiri, M.; Zare, M.; Yousefinejad, S. Ventilatory disorders associated with occupational inhalation exposure to nitrogen trihydride (ammonia). Ind. Health 2018, 56, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrasa, M.; Lamosa, S.; Fernandez, M.D.; Fernandez, E. Occupational exposure to carbon dioxide, ammonia and hydrogen sulphide on livestock farms in north-west Spain. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2012, 19, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Viegas, S.; Mateus, V.; Almeida-Silva, M.; Carolino, E.; Viegas, C. Occupational exposure to particulate matter and respiratory symptoms in Portuguese swine barn workers. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health A 2013, 76, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Essen, S.; Romberger, D. The respiratory inflammatory response to the swine confinement building environment: The adaptation to respiratory exposures in the chronically exposed worker. J. Agric. Saf. Health 2003, 9, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Essen, S.; Donham, K. Illness and injury in animal confinement workers. Occup. Med. 1999, 14, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Donham, K.J.; Reynolds, S.J.; Whitten, P.; Merchant, J.A.; Burmeister, L.; Popendorf, W.J. Respiratory dysfunction in swine production facility workers: Dose-response relationships of environmental exposures and pulmonary function. Am. J. Ind. Med. 1995, 27, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.F.; Garcia, J.; Wu, D.; Mitchell, D.C.; Zhang, Y.; Kado, N.Y.; Wong, P.; Trujillo, D.A.; Lollies, A.; Bennet, D.; et al. Activation of inflammatory responses in human U937 macrophages by particulate matter collected from dairy farms: An in vitro expression analysis of pro-inflammatory markers. Environ. Health 2012, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Minimum Reporting Requirement | |

|---|---|---|

| Description of the Housing system | Animal category | Species and breed |

| Construction and dimensions | Materials, insulation, compartments, capacity, length, width and height | |

| Ventilation system and its design | Ventilation types, sizes and numbers of air inlets and outlets, capacity, set point values, air inlets/outlets | |

| Manure parameters | Amount [m3] (M), | |

| Feeding | Strategy and frequency | |

| Description of the measuring system (for ammonia and pm measurement) | Ammonia | Technical components: Material and characteristics, functional description and design |

| Ammonia | Operational parameters: Ranges | |

| PM10 | Technical components: Material and characteristics, functional description and design | |

| PM10 | Operational parameters: Ranges | |

| PM2.5 | Technical components: Material and characteristics, functional description and design | |

| PM2.5 | Operational parameters: Ranges | |

| Primary Parameter and Sampling conditions | Ammonia | Cumulative sampling up to 24 h or continuous measuring methods based on hourly values (24 samples) |

| Ammonia | Sampling location: see measuring strategy (i.e., if naturally or mechanically ventilated) | |

| Ammonia | Calibration of the measuring instruments | |

| PM10 | Cumulative sampling up to 24 h or continuous measuring methods based on hourly values (24 samples) | |

| PM10 | Sampling location: see measuring strategy (i.e., if naturally or mechanically ventilated) | |

| PM10 | Calibration of the measuring instruments | |

| PM2.5 | Cumulative sampling up to 24 h or continuous measuring methods based on hourly values (24 samples) | |

| PM2.5 | Sampling location: see measuring strategy (i.e., if naturally or mechanically ventilated) | |

| PM2.5 | Calibration of the measuring instruments |

| Authors, Year | Monitoring Data |

|---|---|

| 1. Choi et al., 2023 [25] | -NH3 emission piglets ± SD: 0.31 ± 0.21 kg/animal years; PM10 emission piglets ± SD: 0.03 ± 0.03 kg/animal years; PM2.5 emission piglets ± SD: 0.01 ± 0.01 kg/animal years; NH3 emission growing pigs ± SD: 1.85 ± 1.26 kg/animal years; PM10 emission growing pigs ± SD: 0.16 ± 0.17 kg/animal years; PM2.5 emission growing pigs ± SD: 0.09 ± 0.10 kg/animal years |

| 2. Ji Qin Ni et al., 2012 [26] | -NH3 emissions barns HA: 0.5–175.7 ppm 1st yr mean: 49.9 ± 39.6 ppm; 2st yr mean: 47.7 ± 38.3 ppm; HB: 1.2–182.0 ppm—1st yr mean: 55.5 ± 44.2 ppm; 2st yr mean: 48.0 ± 36.2 ppm BA: 1.1–61.3 ppm—1st yr mean: 14.6 ± 10.2 ppm; 2st yr mean: 12.0 ± 7.8 ppm; BB: 0.2–57.2 ppm—1st yr mean: 12.0 ± 10.2 ppm; 2st yr mean: 13.8 ± 10.6 ppm -PM10 emission barns: HA: 1–1719 ug/m3—1st yr mean: 473 ± 285 ug/m3; 2st yr mean: 616 ± 305 ug/m3; HB: 3–3270 ug/m3—1st yr mean: 443 ± 203 ug/m3; 2st yr mean: 668 ± 408 ug/m3 BA: 0–2702 ug/m3—1st yr mean: 438 ± 393 ug/m3; 2st yr mean: 402 ± 447 ug/m3; BB: 0–4039 ug/m3—1st yr mean: 929 ± 778 ug/m3; 2st yr mean: 629 ± 516 ug/m3 |

| 3. Jihoon Park et al., 2019 [39] | NH3 concentration: laying hens (GM range: 6.9 and 57.9 ppm); swine farms (GM range: 5.9 and 43.2 ppm); broiler hen farms (GM range: 2.6 and 8.6 ppm) |

| 4. Qian-Feng Li et al., 2013 [41] | PM Type; N (number of hourly means); Mean; SD Median PM2.5; 1035; 12.3 ± 9.1; 10.0 PM10 14,369; 35.0 ± 40.7; 28.2 |

| 5. Dan Shen et al., 2019 [33] | PM10 Mean ± SD: high-rise nursery burns = 0.388 ± 0.09; high-rise fattening burns = 0.338 ± 0.1; Outside = 0.111 ± 0.07; PM2.5 Mean ± SD: high-rise nursery burns = 0.210 ± 0.09; high-rise fattening burns = 0.144 ± 0.06; Outside = 0.0880 ± 0.05; NH3 Mean ± SD: high-rise nursery burns = 12.2 ± 3; high-rise fattening burns = 26.7 ± 7; Outside = 2.27 ± 1 |

| 6. Y. Zhao et Al., 2015 [37] | -NH3 Mean ± SD mg/m3: Ambient: 0.4 ± 0.5; CC 4.0 ± 2.4; AV 6.7 ± 5.9; EC 2.8 ± 1.7 PM10, Mean ± SD mg/m3: CC 0.59 ± 0.16; AV 3.95 ± 2.83; EC 0.44 ± 0.18 -PM2.5, Mean ± SD mg/m3: CC 0.035 ± 0.013; AV 0.410 ± 0.251; EC 0.056 ± 0.021 |

| 7. Yu Wang et al., 2020 [38] | -NH3 concentration: Mean ± SD mg/m3: Summer: 3.9 ± 1.2; Autumn: 3.7 ± 1.6; Winter: 5.0 ± 1.1 -PM2.5 concentration: Mean ± SD (mg/m3): Summer: 100 ± 21; Autumn: 1.07 ± 2.5; Winter: 1.44 ± 6.8 -PM10 concentration: Mean ± SD (mg/m3) (mg/m3): Summer: 35.4 ± 4.4; Autumn: 56.2 ± 4.8; Winter: 82.8 ± 9.7 |

| 8. Yaomin Jin et al., 2012. [42] | NH3 concentration (SD): 0.40 (0.09) |

| 9. Li Q.-F. et al., 2013 [43] | PM2.5 concentration: Mean ± SD: 0.37 ± 3.06 mg d−1 hen −1 PM10 concentration: Mean ± SD: 17.8 ± 14.9 mg d−1 hen −1 |

| 10. Casey et al., 2012 [44] | NH3 concentration: Mean ± SD—B1: 9.25 ± 1.85 g d−1 hen −1; B2: 9.61 ± 1.28 d−1 hen −1; F9: 19.1 ± 6.0 d−1 hen −1 |

| 11. Li et al., 2018 [45] | -Nursery Results concentration: Mean ± SD PM10: 0.39 ± 0.09 mg/m3, PM2.5: 0.21 ± 0.09 mg/m3, NH3: 12.18 ± 3.36 mg/m3 -Fattening Stable concentration: Mean ± SD PM10: 0.34 ± 0.10 mg/m3, PM2.5: 0.14 ± 0.06 mg/m3, NH3: 26.70 ± 6.78 mg/m3 |

| 12. Hayes et al., 2012 [32] | -Daily indoor aerial concentration: Mean ± SD NH3: 8.7 ± 8.4 ppm, PM10: 2.3 ± 1.6 mg m−3, PM2.5: 0.2 ± 0.3 mg m−3 -Daily emission rates: Mean ± SD (mg/m3)—NH3: 0.15 ± 0.08 g bird −1, PM10: 0.11 ± 0.04 g bird −1, PM2.5: 0.008 ± 0.006 g bird−1 |

| 13. Von Jasmund et al., 2020 [30] | NH3 concentration: Mean ± SD—NH3: 12.05 ± 6.94 ppm |

| 14. Wu et al., 2020 [46] | NH3 concentration: Mean-NH3: 61.6 g a−1 m−2, NH3: 8.63 kg a−1 AP−1, NH3: 7.19 kg a−1 AU−1 |

| 15. Joo et al., 2015 [27] | PM2.5 Mass concentration (ug/m3) B1: 72.6 ± 8.1; B2: 67.8 ± 12.1; Ambient: 30.7 ± 9.4; PM2.5 Emission rate (mg/min) B1: 2.8 ± 1.4 B2: 2.5 ± 1.3 PM10 Mass concentration (ug/m3) B1: 330 ± 162; B2: 577 ± 280; Ambient: 247 ± 132; PM10 Emission rate (mg/min) B1: 10.7 ± 6.3; B2: 17.0 ± 10.0 |

| 16. Jin et al., 2010 [47] | NH3 emission rate (ppm): From 18.53 to 20.13 ppm |

| 17. Garcia et al., 2013 [48] | PM2.5 emission rate Mean (range) [ug/m3] Geometric mean: 24 (2–116) ug/m3; Arithmetic mean: 30 (2–116) ug/m3 |

| 18. Dai et al., 2018 [35] | -NH3 emission rate (ug/s): H1: from 93.85 ± 0.13 to 416.75 ± 0.28; H2: from 48.01 ± 0.05 to 241.12 ± 0.11 -PM10 emission rate (ug/h): H1: 5.091 ± 0.285; H2: 5.187 ± 0.135; H3: 5.235 ± 0.559; H4: 5.379 ± 0.092 -PM2.5 emission rate (ug/h): H1: 0.096 ± 0.048; H2: 0.096 ± 0.048; H3: 0.096 ± 0.048; H4: 0.048 ± 0.048 -PM10 concentration (min–max; average) [ug/m3]: H1: 6–756; 91; H2: 3–2140; 82; H3: 2–674; 80; H4: 3–1160; 76 -PM2.5 concentration (min–max; average) [ug/m3]: H1: 6–355; 56; H2: 3–728; 47; H3: 2–270; 43; H4: 3–561; 42 |

| 19. Shepherd et al., 2015 [36] | -NH3 emission rate (g/hen/d): CC: from 0.068 ± 0.004 to 0.097 ± 0.01; AV: from 0.088 ± 0.006 to 0.136 ± 0.011; EC: from 0.049 ± 0.004 to 0.059 ± 0.006 -PM10 emission rate (mg/hen/d): CC: from 14.5 ± 0.90 to 16.9 ± 1.02; AV: from 87.6 ± 3.92 to 113.0 ± 5.07; EC: from 13.9 ± 0.66 to 17.3 ± 0.90 -NH2.5 emission rate (mg/hen/d): CC: from 0.9 ± 0.14 to 1.0 ± 0.24; AV: from 8.6 ± 0.32 to 9.1 ± 0.27; EC: from 1.5 ± 0.10 to 1.9 ± 0.15 |

| 20. Tamar Tulp et al., 2024 [29] | NH3 concentration: NE direction: 21–100 ug/m3; NW direction: 6.6–56.7 ug/m3; SE direction: 31.5–108.7 ug/m3; SW direction: 7.5–36.7 ug/m3 |

| 21. Schmithauesen et al., 2018 [34] | NH3 emission (g/LU/d): Control group: P1: 18.4 ± 4.1; P2: 24.2 ± 9.6; P3: 30.0 ± 4.9; P4: 27.4 ± 2.0 Experimental group: P1: 19.8 ± 2.3; P2: 23.0 ± 6.0; P3: 22.3 ± 2.5; P4: 22.2 ± 3.5 |

| 22. Zenon Nieckarz et al., 2023 [49] | -PM10 concentration (ug/m3) Average daily outside: 150; Average daily inside: 138.8 -PM2.5 concentration (ug/m3) Average daily outside: 106; Average daily inside: 119 |

| 23. W. Zheng et Al., 2020 [31] | NH3 concentration (mean ± SD) [ppm] A: from 0.0 ± 0.0 to 7.8 ± 2.8; B: from 2.0 ± 2.6 to 22.0 ± 3.2; C: from 0.8 ± 1.9 to 20.4 ± 4.5; D: from 1.2 ± 2.2 to 28.1 ± 4.7 |

| 24. Zhifang Shi et al., 2019 [28] | NH3 concentration barns: Mean 1.54 mg/m3; Lactating barns 2.13 mg/m3; Bon-lactating barns 0.83 mg/m3 |

| 25. Jannat A et al., 2025 [50] | -PM2.5 concentration [ug/m3]: TVB: 4.75 ± 0.03; MLP: 4.65 ± 0.03 -NH3 concentration (ppm) Average: 7.93 ± 0.34 ppm |

| 26. Li et al., 2024 [40] | -NH3 concentration (mg h−1 cow −1) Average: 3113.4 -PM2.5 concentration (mg h−1 cow −1) Average: 54.2 |

| Authors, Year [References] | Monitoring Sites and Time | Analytical Methods | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instruments Analysis | Filters and Flow Rate | Models | Data Quality | ||

| 1. Choi et al., 2023 [25] | -Monitoring sites: NR -Monitoring time: Piglet pens and growing finishing pig pens over a period of one and a half years in 2020 | NH3 and PM: portable gas detector (Gastiger 2000) and personal impactors connected to an Aircheck sampling pump. | PM10 and PM2.5: PTFE filter (37 mm, 2 um pore). Flow rate of 4 L per minute. | NR | NR |

| 2. Ji Qin Ni et al.,2012 [26] | -Monitoring sites: In the top and bottom of the high-rise houses -Monitoring time: NR | NH3: one multi-gas photoacoustic Field Gas-Monitor | NR | NR | NR |

| 3. Jihoon Park et al., 2019 [39] | NR | NH3: direct reading multigas monitor | NR | ANOVA | NR |

| 4. Qian-Feng Li et al., 2013 [41] | NR | NH3: a real-time analyzer PM2.5: Partisol Model 2300 chemical speciation samplers. | HCD Nylon filter. Flow rate: NR. | ISORROPIA-II | NR |

| 5. Dan Shen et al., 2019 [33] | -Monitoring sites: horizontal locations at different heights (0.5 m, 1.0 m and 1.5 m) in the middle of the barns. -Monitoring time: from 07:00 to 19:00 at 2 h intervals for 6 d (7 times per day). From 1st to 12th April 2017. | PM2.5: DustTrak™ II 8532 Handheld Aerosol Monitor | Prebaked quartz filters (47 mm diameter, Whatman Inc., Clifton, NJ, USA). PM2.5: Flow rate of 16.7 L/min for 12 h per day for 6 d | ANOVA | NR |

| 6. Y. Zhao et al., 2015 [37] | -Monitoring sites: NR -Monitoring time: 3-year CSES project covered 2 single-cycle production flocks. | NH3: fast response and precision photoacoustic multi-gas analyzer | Y-shaped sampling port with two dust filters and with two inline Teflon filters (47 mm filter membrane, 5 to 6 μm). Flow rate: NR | GLIMMIX model | NR |

| 7. Yu Wang et al., 2020 [38] | -Monitoring sites: NR -Monitoring time: August 2018, October 2018, and January 2019 | NH3: NH3-NO-NO2 analyzer. PM10 and PM2.5: four medium-volume air samplers | 6.26 mm-inside-diameter Teflon tubing. PM10 and PM2.5 samples were collected at a flow rate of 100 L/min. | ANOVA using Duncan’s LSD test | NH3 measurement range: 0–100 ppm, sensitivity: 1 ppb |

| 8. Yaomin Jin et al., 2012. [42] | -Monitoring sites: 17 gas-sampling locations (GSLs) were selected at the site -Monitoring time: NR. | Gas analyzer: a photoacoustic infrared CO2 analyzer, a fluorescence-based H2S analyzer and a photoacoustic multigas analyzer | To protect air using in-line membrane filters. Flow rate: NR | AirDAC software | NR |

| 9. Li Q-F. et al., 2013 [43] | -Monitoring sites: Concentration of PM was monitored in the exhaust air and at an outside location. -Monitoring time: NR | Inlet PM: beta attenuation PM monitor. PM concentration in the exhaust air: TEOM model 1400a. | TEOM filters Flow rate: NR | Strategy 1: Stream Method Strategy 2: Single Stream and Dual Stream Methods | NR |

| 10. Casey et al., 2012 [44] | -Monitoring sites: between gestation barns 1 and 2. -Monitoring time: NR | Gas analyzer: a photoacoustic IR multi-gas monitor INNOVA Model 1412 | NR | NR | NR |

| 11. Li Z et al., 2018 [45] | -Monitoring sites: various positions at 3 different heights -Monitoring time: for 3 days from 07 to 19 at an interval of 2 h | PM2.5—PM10: DustTrakTMII8532 NH3: JK40-IV portable gas detector | NR | ANOVA | NR |

| 12. Hayes et al., 2012 [32] | -Monitoring sites NH3: measured continually in 4 locations in each house. -Monitoring sites: PM 10 and 2.5: measured continuously inside the houses. -Monitoring time: NR | NH3: fast-response, high- precision infrared (IR) photoacoustic multi gas analyzer. PM10 and PM2.5: TEOM equipped with the respective PM head | FEP Teflon tubing (0.95 cm) was used for air sampling to avoid NH3 absorption: coarse filter and a fine dust filter (47 mm filter membrane, Savillex). Flow rate: NR | NR | NR |

| 13. Von Jasmund et al., 2020 [30] | -Monitoring sites: NH3 in the middle of the pen at a height of 1.47 m -Monitoring Time: from March to July 2019 | NH3 concentration: Polytron C300 equipped with a gas electrochemical sensor | NR | NR | Accuracy: 1.5 ppm ± 10% of the measured value |

| 14. Wu et al., 2020 [46] | -Monitoring sites: in the middle of the feedlot pen surface of the dairy farm -Monitoring Time: daylight hours in May 2017 for 7 consecutive days | NH3 concentration: UV/vis spectrophotometer | Filters: NR Flow rate: 5 L/min | AEROMOD | NR |

| 15. Joo et al., 2015 [27] | -Monitoring sites: At the centre of each barn, 3 m below the roof of the barn. -Monitoring time: July and August 2009, data were collected continuously during this period except for four days. | PM mass concentrations: 2 tapered element oscillating microbalances (TEOMs) and Beta ray attenuation particle monitor. | Filters: NR Flow rate: 3.0 L/min | NR | NR |

| 16. Jin et al., 2010 [47] | -Monitoring sites: 17 points in all the stable -Monitoring Time: NR | NH3 emission: photoacoustic multi-gas analyser. PM emission (PM10-PM2.5): TEOM tapered element oscillating microbalance. | Optical filter for each gas Flow rate: NR | NR | Measurement accuracy of 2–3%; detection thresholds ppm for NH3. TEOM (pulsed fluorescence analyser): detection limit of 6.0 ppb and precision 1 ppb. |

| 17. Garcia et al., 2013 [48] | -Monitoring sites: 6 Different point in the stables -Monitoring time: NR. | PM2.5 concentration: GK2.05SH cyclone sampler | Teflon Millipore filters (37 mm) with a pore size of 0.45 mm (Fisher Scientific) to collect PM. Flow rate: 3.5 L/min | NR | NR |

| 18. Dai et al., 2018 [35] | -Monitoring sites: not specified different points in houses -Monitoring Time: NR | NH3 concentration: air sampler (TH-110F). PM concentration: Dustrak Drx Aerosol Monitor 8533. | Filters: NR Flow rate: 0.8 L/min. | NR | NR |

| 19. Sheperd et al., 2014 [36] | -Monitoring sites: 9 in-house locations (3 locations per house) and one ambient location -Monitoring Time: NR | NH3 concentration: photoacoustic multi-gas analyzer. | Filters: Two dust filters in the air tubes, and with 2 inline Teflon filters Flow rate: NR | NR | NR |

| 20. Tamar Tulp et al., 2024 [29] | -Monitoring sites: samples point 500 m around the stable. -Monitoring time: between 4 August 2021 and 13 October 2021 with an interval of two weeks | NH3 concentration: a passive sampler: ‘ALPHA’, | A filter paper that was coated in citric acid, and a white PTFE (Teflon) membrane Flow rate: NR | ‘MuMIn’ and Akaike information criterion (AIC). | NR |

| 21. Schmithausen et al., 2018 [34] | -Monitoring sites: 2 points in Sections 1 and 2 of the houses -Monitoring time: from8 January to 25 June 2013 | NH3: photoacoustic multi-gas analyzer | NR | NR | Accuracy 2–3% detection limits: 0.14 mg/m3 |

| 22. Zenon Nieckarz et al., 2023 [49] | -Monitoring sites: 2 m above the floor, and the second one outside, 2 m above the ground -Monitoring time: NR | PM2.5, PM10 concentration: University Measure Systems with, laser sensor SEN0177 | NR | Gravimetric | The measurement error of the EDM107 analyzer is ±2 μg/m3 and not exceeding ±9 μg/m3 |

| 23. W. Zheng et al., 2020 [31] | Monitoring sites: Samples point in various directions in the house Monitoring time: from February to July 2016. | NH3 concentration: 4 Intelligent Portable Monitoring Units (iPMUs) | Filters: Dust cup Flow rate: NR | NR | NR |

| 24. Zhifang Shi et al., 2019 [28] | Monitoring sites: 2 outside locations and 5 inside locations at 1.5 m above the floor Monitoring time: from July 4 to August 21, 2017 | NH3 concentration: an integrated air sampler and a spectrophotometer | NR | NR | NR |

| 25. Jannat A et al., 2025 [50] | -Monitoring sites: TVB: in the center of the barn at 4 m from the ground. MKP: at the center of the rotary milking machine. -Monitoring time: continuously from 16 August to 22 December 2023 | IEQ Max (Denver, CO) multiple sensor platform system. NH3: electrochemical sensor PM2.5: mechanical sensor | NR | NR | NH3 electrochemical sensor: Accuracy: ±20% Range: from 0.4 to 60 (ppm) PM2.5: mechanical sensor Accuracy: ±20% Range: from 0 to 5000 ug/m3 |

| 26. Li et al., 2024 [40] | -Monitoring sites: NR -Monitoring time: NR | Two self-developed environment-monitoring devices, the portable particulate monitoring unit (PPMU) and the portable gas monitoring unit (PGMU) NH3: NE03-NH3 PM2.5: PMSX003N | NR | NH3: electrochemical PM2.5: Mie scattering | NH3 manufacture: Range: 0–50 ppm Resolution: 0.1 ppm Response time:/ Accuracy: ±10 F.S. PM2.5 manufacture: Range: 0–500 ug/m3 Resolution: 1 ug/m3 Response time: <1 ms Accuracy: ±10 ug/m3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Arcidiacono, C.; Rapisarda, P.; Palella, M.; Longo, M.V.; Moscato, A.; D’Urso, P.R.; Ferrante, M.; Fiore, M. Compliance with the Verification of Environmental Technologies for Agricultural Production Protocol in Ammonia and Particulate Matter Monitoring in Livestock Farming: Development and Validation of the Adherence VERA Index. Environments 2026, 13, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010024

Arcidiacono C, Rapisarda P, Palella M, Longo MV, Moscato A, D’Urso PR, Ferrante M, Fiore M. Compliance with the Verification of Environmental Technologies for Agricultural Production Protocol in Ammonia and Particulate Matter Monitoring in Livestock Farming: Development and Validation of the Adherence VERA Index. Environments. 2026; 13(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleArcidiacono, Claudia, Paola Rapisarda, Marco Palella, Maria Valentina Longo, Andrea Moscato, Provvidenza Rita D’Urso, Margherita Ferrante, and Maria Fiore. 2026. "Compliance with the Verification of Environmental Technologies for Agricultural Production Protocol in Ammonia and Particulate Matter Monitoring in Livestock Farming: Development and Validation of the Adherence VERA Index" Environments 13, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010024

APA StyleArcidiacono, C., Rapisarda, P., Palella, M., Longo, M. V., Moscato, A., D’Urso, P. R., Ferrante, M., & Fiore, M. (2026). Compliance with the Verification of Environmental Technologies for Agricultural Production Protocol in Ammonia and Particulate Matter Monitoring in Livestock Farming: Development and Validation of the Adherence VERA Index. Environments, 13(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments13010024