Fin Whale Balaenoptera physalus Historical Sightings and Strandings, Ship Strikes, Breeding Areas and Other Threats in the Mediterranean Sea: A Review (1624–2023)

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives

1.2. Feeding

1.3. Breeding Areas

1.4. Natural and Anthropogenic Hazards

2. Materials and Methods

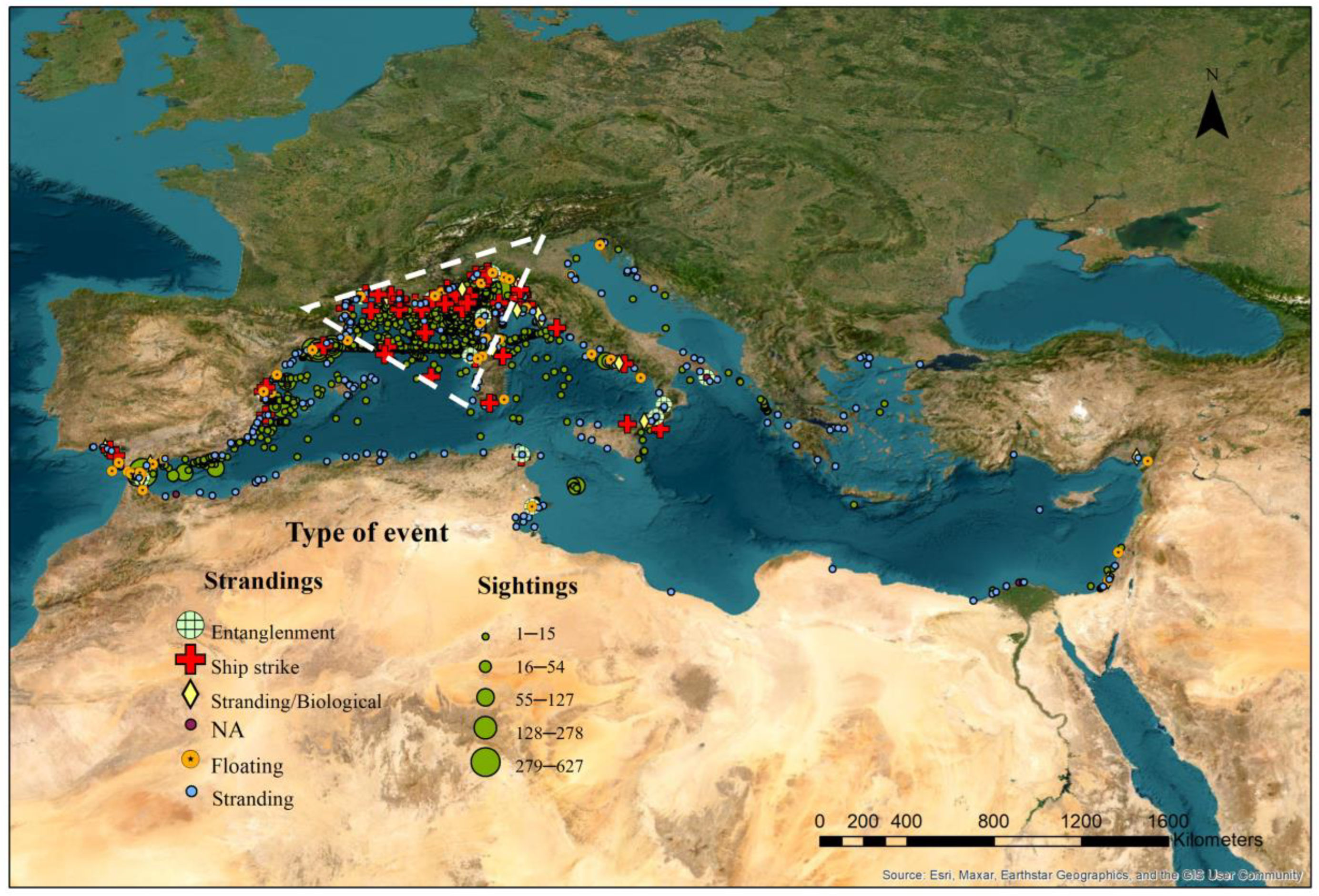

3. Results

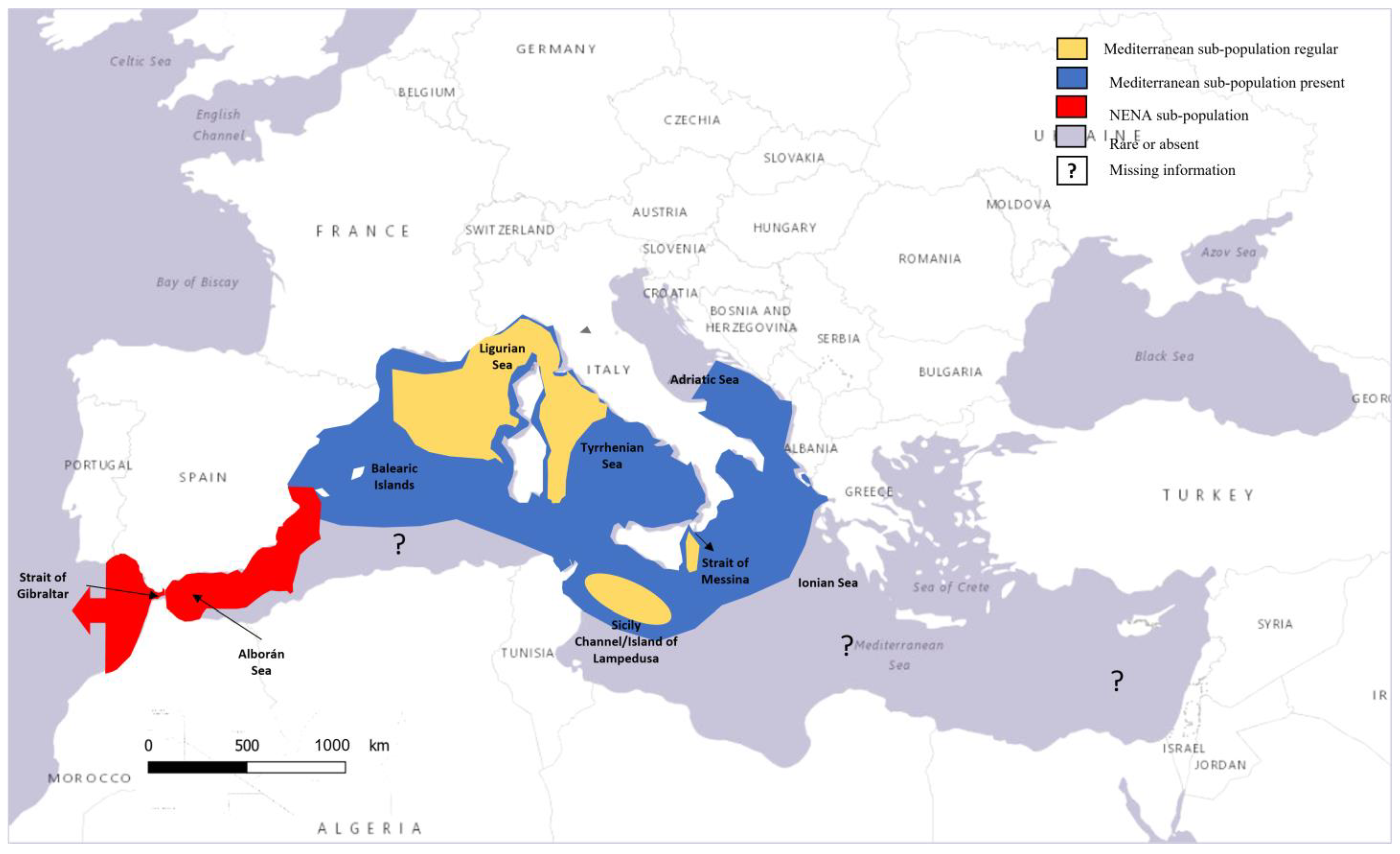

3.1. Fin Whales in the Mediterranean Sea

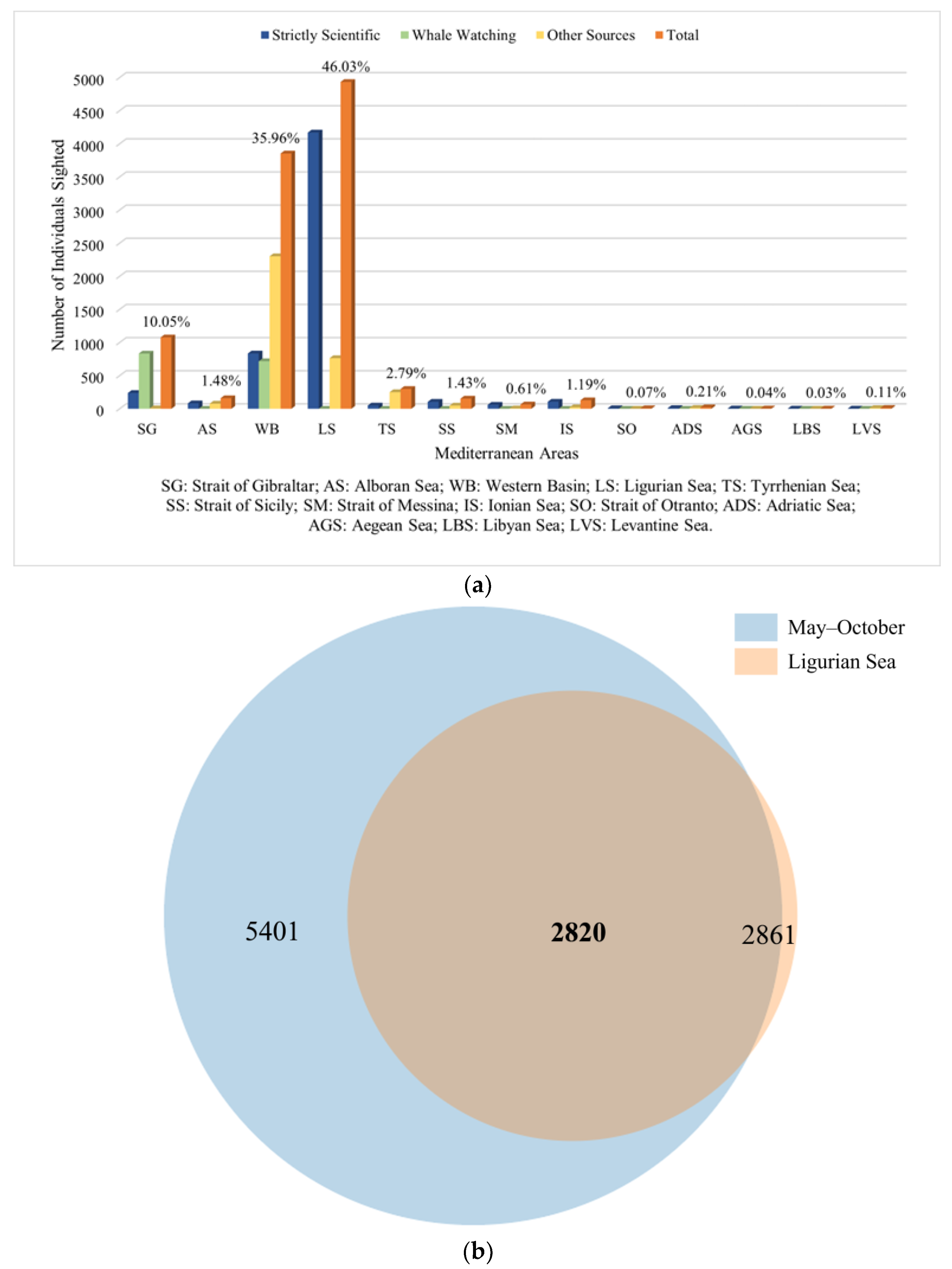

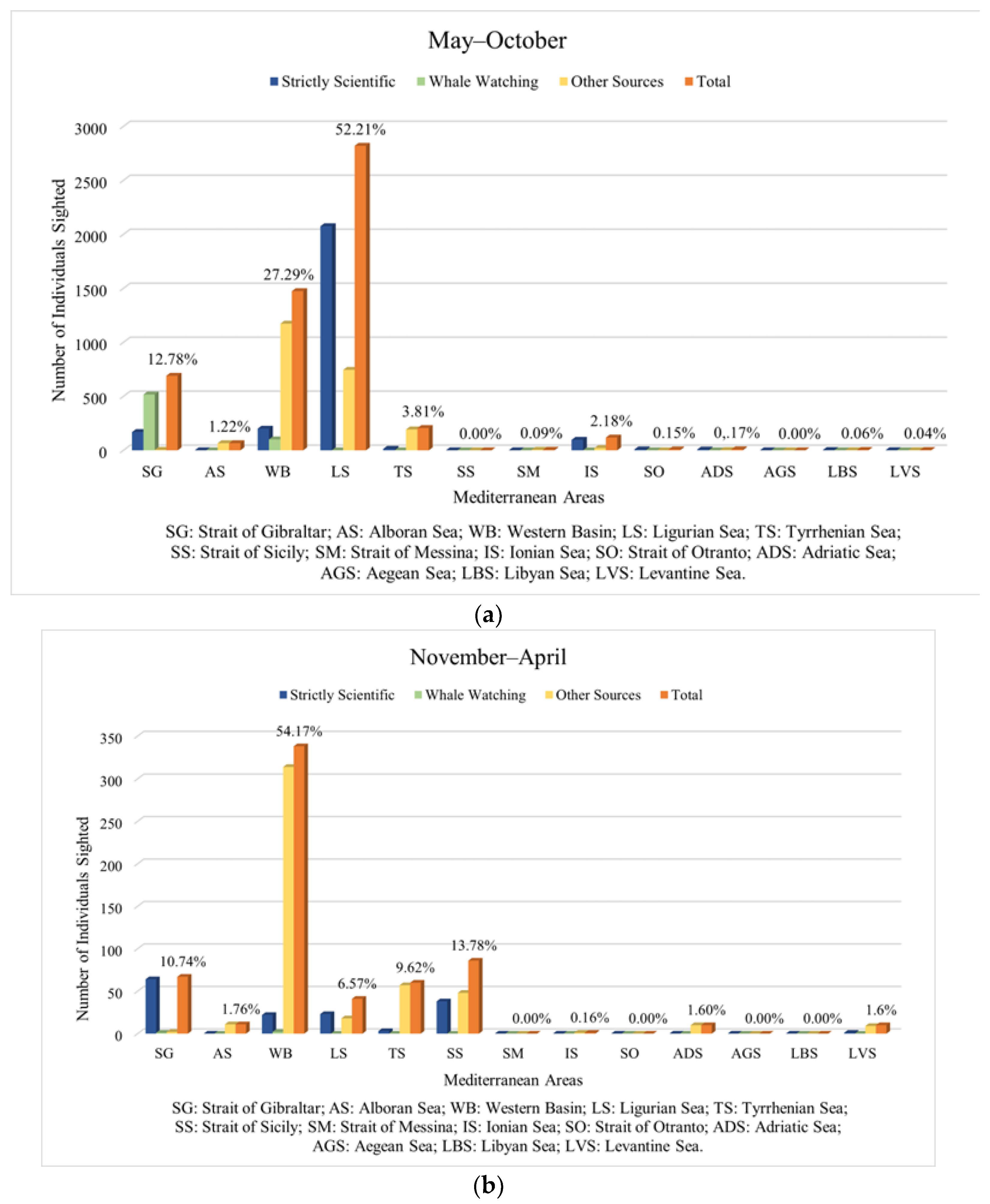

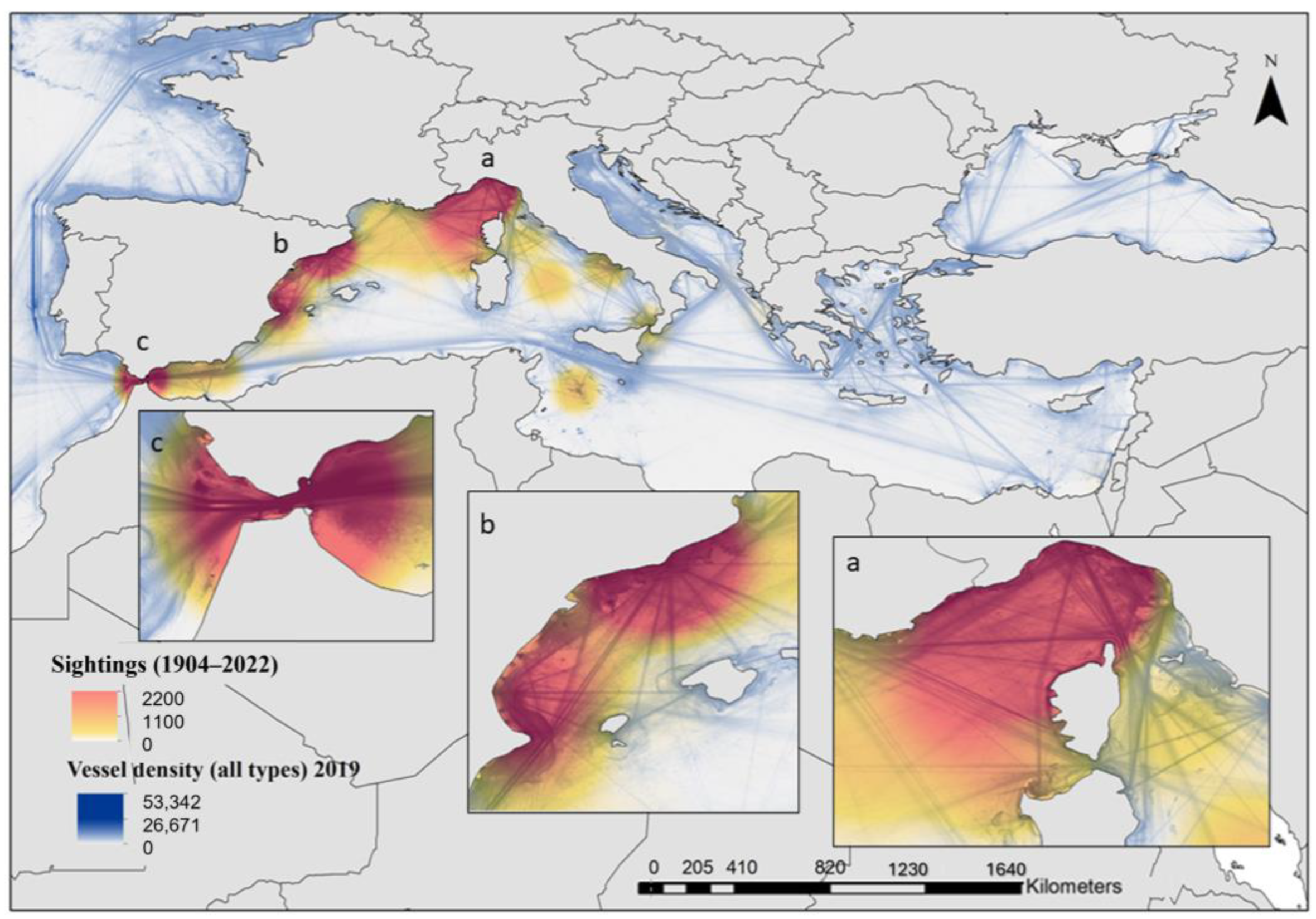

3.2. Chronology and Analysis of Sightings (1904–2022)

3.3. Sightings “Near–Far” from the Shore in the Mediterranean Sea

3.4. Why Atlantic–Mediterranean Migration?

3.5. Collisions, Strandings and Deaths at Sea

3.6. Acoustic Locations

3.7. Breeding Season and Calves’ Location Areas

3.8. Chemical Contamination

3.9. Diseases

4. Discussion

Conservation Strategies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stoett, P. Irreconcilable Differences: The International Whaling Commission and Cetacean Futures. Rev. Policy Res. 2011, 28, 631–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panigada, S.; Gauffier, P.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. Balaenoptera physalus (Mediterranean subpopulation). In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources: Gland, Switzerland, 2021; p. e.T16208224A50387979. [Google Scholar]

- Directive, H. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. Off. J. Eur. Union 1992, 206, 7–50. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe (CE). The Bern Convention (19 September 1979) on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats; Document 104; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- ACCOBAMS. Estimates of Abundance and Distribution of Cetaceans, Marine Mega-Fauna and Marine Litter in the Mediterranean Sea from 2018–2019 Surveys; Panigada, S., Boisseau, O., Canadas, A., Lambert, C., Laran, S., McLanaghan, R., Moscrop, A., Eds.; ACCOBAMS: Monaco City, Monaco, 2021; 177p. [Google Scholar]

- Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Agardy, T.; Hyrenbach, D.; Scovazzi, T.; Van Klaveren, P. The Pelagos sanctuary for 570 Mediterranean Marine Mammals. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2008, 18, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMO. Designation of the North-Western Mediterranean Sea as a Particularly Sensitive Mediterranean Sea Area; Resolut. MEPC38080; IMO: London, UK, 2023; Volume 26, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci, R.; Manea, E.; Ricci, P.; Cipriano, G.; Fanizza, C.; Maglietta, R.; Gissi, E. Managing Multiple Pressures for Cetaceans’ Conservation with an Ecosystem-Based Marine Spatial Planning Approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 287, 112240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, E.; Alfaro-Shigueto, J.; Aliaga-Rossel, E.; Beasley, I.; Briceño, Y.; Caballero, S.; da Silva, V.M.F.; Gilleman, C.; Gravena, W.; Hines, E.; et al. Challenges And Priorities For River Cetacean Conservation. Endanger. Species Res. 2022, 49, 13–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laran, S.; Pettex, E.; Authier, M.; Blanck, A.; David, L.; Dorémus, G.; Falchetto, H.; Monestiez, P.; Van Canneyt, O.; Ridoux, V. Seasonal Distribution and Abundance of Cetaceans within French Waters—Part I: The North-Western Mediterranean, Including The Pelagos Sanctuary. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2017, 141, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tort Castro, B.; Prieto González, R.; O’Callaghan, S.A.; Dominguez Rein-Loring, P.; Degollada Bastos, E. Ship Strike Risk for Fin Whales (Balaenoptera Physalus) off the Garraf Coast, Northwest Mediterranean Sea. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 867287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaussonie, G. Loi N◦ 2016-1087 Du 8 Août 2016 Pour La Reconquête de La Biodiversité, de La Nature et Des Paysages; Revue de Science Criminelle et de Droit Pénal Comparé: Tolouse, France, 2017; p. 814. Available online: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-02245415/ (accessed on 27 March 2024).

- Scoresby, W. An Account of the Arctic Regions, with a History and Description of the Northern Whale-Fishery; A. Constable & Co.: Edinburgh, UK, 1820. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, À. Chimán. La Pesca Ballenera Moderna En La Península Ibérica; Edicions Universitat Barcelona: Barcelona, Spain, 2013; ISBN 9788447537631. [Google Scholar]

- Gauffier, P.; Verborgh, P.; Giménez, J.; Esteban, R.; Salazar Sierra, J.; de Stephanis, R. Contemporary Migration of Fin Whales Through The Strait Of Gibraltar. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2018, 588, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, A.; García-Vernet, R. Fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus). In Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals, 3rd ed.; Würsig, B., Thewissen, J.G.M., Kovacs, K.M., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 368–371. [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé, M.; Aguilar, A.; Dendanto, D.; Larsen, F.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Sears, R.; Sigurjónsson, J.; Urban-R, J.; Palsbøll, P.J. Population Genetic Structure of North Atlantic, Mediterranean Sea and Sea of Cortez Fin Whales, Balaenoptera Physalus (Linnaeus 1758): Analysis of Mitochondrial and Nuclear Loci. Mol. Ecol. 1998, 7, 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, E.F.; Hall, C.; Moore, T.J.; Sheredy, C.; Redfern, J.V. Global Distribution of Fin Whales Balaenoptera Physalus in the Post-Whaling Era (1980–2012). Mamm. Rev. 2015, 45, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, G.; Zanardelli, M.; Jahoda, M.; Panigada, S.; Airoldi, S. The Fin Whale Balaenoptera physalus (L. 1758) in the Mediterranean Sea. Mamm. Rev. 2003, 33, 105–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Castellote, M.; Druon, J.-N.; Panigada, S. Fin Whales, Balaenoptera physalus. Adv. Mar. Biol. 2016, 75, 75–101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cooke, J.G. Balaenoptera physalus. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018. p. e. T2478A50349982. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T2478A50349982.en (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Panigada, S.; Pesante, G.; Zanardelli, M.; Capoulade, F.; Gannier, A.; Weinrich, M.T. Mediterranean Fin Whales at Risk from Fatal Ship Strikes. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 1287–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castellote, M.; Clark, C.W.; Lammers, M.O. Acoustic and Behavioural Changes by Fin Whales (Balaenoptera Physalus) in Response to Shipping and Airgun Noise. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 147, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellote, M.; Clark, C.W.; Lammers, M.O. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Population Identity in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2012, 28, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Wright, A.J.; Ashe, E.; Blight, L.K.; Bruintjes, R.; Canessa, R.; Clark, C.W.; Cullis-Suzuki, S.; Dakin, D.T.; Erbe, C.; et al. Impacts of Anthropogenic Noise on Marine Life: Publication Patterns, New Discoveries, and Future Directions in Research and Management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2015, 115, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Weelden, C.; Towers, J.R.; Bosker, T. Impacts of Climate Change on Cetacean Distribution, Habitat and Migration. Clim. Change Ecol. 2021, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, B.; Garcia-Garin, O.; Borrell, A.; Aguilar, A.; Víkingsson, G.A.; Eljarrat, E. Transplacental Transfer of Plasticizers and Flame Retardants in Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) from the North Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panigada, S.; Zanardelli, M.; Canese, S.; Jahoda, M. How Deep Can Baleen Whales Dive? Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999, 187, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Marsili, L.; Baini, M.; Giannetti, M.; Coppola, D.; Guerranti, C.; Caliani, I.; Minutoli, R.; Lauriano, G.; Finoia, M.G.; et al. Fin Whales and Microplastics: The Mediterranean Sea and the Sea of Cortez Scenarios. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 209, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canese, S.; Cardinali, A.; Fortuna, C.M.; Giusti, M.; Lauriano, G.; Salvati, E.; Greco, S. The First Identified Winter-Feeding Ground of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Mediterranean Sea. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. 2006, 86, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotté, C.; Guinet, C.; Taupier-Letage, I.; Mate, B.; Petiau, E. Scale-Dependent Habitat Use by a Large Free-Ranging Predator, the Mediterranean Fin Whale. Deep-Sea Res. I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2009, 56, 801–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentaleb, I.; Martin, C.; Vrac, M.; Mate, B.; Mayzaud, P.; Siret, D.; de Stephanis, R.; Guinet, C. Foraging Ecology of Mediterranean Fin Whales in a Changing Environment Elucidated by Satellite Tracking and Baleen Plate Stable Isotopes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 438, 285–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardou, J.; Etienne, M.; Andersen, V. Seasonal Abundance and Vertical Distributions of Macroplankton and Micronekton in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Oceanol. Acta 1996, 19, 645–656. [Google Scholar]

- Falk-Petersen, S.; Gatten, R.R.; Sargent, J.R.; Hopkins, C.C.E. Ecological Investigations on the Zooplankton Community in Balsfjorden, Northern Norway: Seasonal Changes in the Lipid Class Composition of Meganyctiphanes Norvegica (M. Sars), Thysanoessa Raschii (M. Sars), and T. Inermis (Krøyer). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1981, 54, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaartvedt, S.; Larsen, T.; Hjelmseth, K.; Onsrud, M.S.R. Is The Omnivorous Krill Meganyctiphanes Norvegica Primarily a Selectively Feeding Carnivore? Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002, 228, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, A. In-Situ Feeding in the Northern Krill, Meganyctiphanes norvegica: A DNA Analysis of Gut Contents. Master’s Thesis, University of Rhode Island, Kingston, RI, USA, 2010; p. 907. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K. Food and Feeding in Northern Krill (Meganyctiphanes norvegica Sars). Adv. Mar. Biol. 2010, 57, 127–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panigada, V.; Bodey, T.W.; Friedlaender, A.; Druon, J.N.; Huckstädt, L.A.; Pierantonio, N.; Degollada, E.; Tort, B.; Panigada, S. Targeting Fin Whale Conservation in the North-Western Mediterranean Sea: Insights on Movements and Behaviour from Biologging and Habitat Modelling. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2024, 11, 231783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panigada, S.; Donovan, G.P.; Druon, J.-N.; Lauriano, G.; Pierantonio, N.; Pirotta, E.; Zanardelli, M.; Zerbini, A.N.; di Sciara, G.N. Satellite Tagging of Mediterranean Fin Whales: Working towards the Identification of Critical Habitats and the Focussing of Mitigation Measures. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panigada, S.; Pierantonio, N.; Araújo, H.; David, L.; Di-Méglio, N.; Dorémus, G.; Gonzalvo, J.; Holcer, D.; Laran, S.; Lauriano, G.; et al. The ACCOBAMS survey initiative: The first synoptic assessment of cetacean abundance in the Mediterranean Sea through aerial surveys. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 10, 1270513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardelli, M.; Airoldi, S.; Bérubé, M.; Borsani, J.F.; Di-Meglio, N.; Gannier, A.; Hammond, P.S.; Jahoda, M.; Lauriano, G.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; et al. Long-term photo-identification study of fin whales in the Pelagos Sanctuary (NW Mediterranean) as a baseline for targeted conservation and mitigation measures. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2022, 32, 1457–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellote, M. Patrón Migratorio, Identidad Poblacional E Impacto Del Ruido En La Comunicación Del Rorcual Común (“Balaenoptera physalus” L. 1758) En El Mar Mediterráneo Occidental. Doctoral Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, L. Some Notes on the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Western Mediterranean Sea. In Proceedings of the Whales: Biology–Threats–Conservation, Brussels, Belgium, 5–7 June 1991; pp. 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, L.; Villetti, G.; Consiglio, C.; Evans, P.G.H.; Nice, H. Wintering Areas of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Mediterranean Sea: A Preliminary Survey. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1996, 9, 126–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cotte, C.; d’Ovidio, F.; Chaigneau, A.; Lèvy, M.; Taupier-Letage, I.; Mate, B.; Guinet, C. Scale-Dependent Interactions of Mediterranean Whales with Marine Dynamics. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2011, 56, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsi Relini, L. The Cetacean Sanctuary in the Ligurian Sea: A Further Reason. Biol. Mar. Medit 2000, 7, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Viale, D. Big Whale Populations on the Atlantic Coasts of Spain and the Western Mediterranean. Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 1977, 27, 235. [Google Scholar]

- Viale, D. Cetaceans in the Northwestern Mediterranean: Their Place in the Ecosystem. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. 1985, 23, 491–571. [Google Scholar]

- Van Bressem, M.-F.; Duignan, P.; Banyard, A.; Barbieri, M.; Colegrove, K.; De Guise, S.; Di Guardo, G.; Dobson, A.; Domingo, M.; Fauquier, D.; et al. Cetacean Morbillivirus: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Viruses 2014, 6, 5145–5181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzariol, S.; Marcer, F.; Mignone, W.; Serracca, L.; Goria, M.; Marsili, L.; Di Guardo, G.; Casalone, C. Dolphin Morbillivirus and Toxoplasma Gondii Coinfection in a Mediterranean Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus). BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzariol, S.; Centelleghe, C.; Beffagna, G.; Povinelli, M.; Terracciano, G.; Cocumelli, C.; Pintore, A.; Denurra, D.; Casalone, C.; Pautasso, A.; et al. Mediterranean Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) Threatened by Dolphin MorbilliVirus. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beffagna, G.; Centelleghe, C.; Franzo, G.; Di Guardo, G.; Mazzariol, S. Genomic and Structural Investigation on Dolphin Morbillivirus (DMV) in Mediterranean Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus). Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep41554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Guardo, D.; Mazzariol, G. Cetacean Morbillivirus in Northern and Southern Hemispheres. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agardy, T.; Aguilar, N.; Cañadas, A.; Engel, M.; Frantzis, A.; Hatch, L.; Hoyt, E.; Kaschner, K.; Labrecque, E.; Martin, V.; et al. A Global Scientific Workshop on Spatio-Temporal Management of Noise. 2007. Available online: http://www.pelagosinstitute.gr/en/pelagos/pdfs/Spatio-temporal%20management%20of%20noise.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- Billé, D.; Lowezanin, C. Yachting Centres in the Mediterranean Study N·26; Chamber of Commerce and Industry: Marseille, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cappato, A. Cruises and Recreational Boating in the Mediterranean; Secretary General of the IIC (Istituto Internazionale delle Comunicazioni): Nice, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Erbe, C.; Marley, S.A.; Schoeman, R.P.; Smith, J.N.; Trigg, L.E.; Embling, C.B. The Effects of Ship Noise on Marine Mammals—A Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 476898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, G.S.; Katona, S.K.; Mainwaring, M.; Allen, J.M.; Corbett, J.M. Respiration and Surfacing Rates of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) Observed from a Lighthouse Tower. Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. 1992, 42, 739–745. [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Carvallo, M.; Barilari, F.; Pérez-Alvarez, M.J.; Gutiérrez, L.; Pavez, G.; Araya, H.; Anguita, C.; Cerda, C.; Sepúlveda, M. Impacts of Whale-Watching on the Short-Term Behavior of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in a Marine Protected Area in the Southeastern Pacific. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 623954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz Lopez, D.; Mussi, B.; Miragliuolo, B.; Chiota, A.; Valerio, D. Respiration Patterns of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) off Ischia Island (Southern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy). In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society, Cork, Ireland, 2–5 April 2000; pp. 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Laist, D.W.; Knowlton, A.R.; Mead, J.G.; Collet, A.S.; Podesta, M. Collisions between Ships and Whales. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2001, 17, 35–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; O’Hara, P. Modelling Ship Strike Risk to Fin, Humpback and Killer Whales in British Columbia, Canada. J. Cetacean Res. Manage. 2023, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.O.; Reeves, R.R.; Brownell, R.L., Jr. Status of the World’s Baleen Whales. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 2016, 32, 682–734. [Google Scholar]

- Spitz, J.; Peltier, H.; Authier, M. Evaluationde l’état Écologique Desmammifères Marins En France Métropolitaine. Rapport Scientifique Pourl’évaluation 2018 Au Titre de La DCSMM. Obs. PELAGIS-UMS 2018, 3462, 173–358. [Google Scholar]

- Emergency Task Force: For a Coordinated Cetacean Stranding Response during Mortality Events Caused by Infectious Agents and Harmful Alga Blooms (Document Prepared by Dr. Marie-Francoise Van Bressem); CMED/CEPEC: Bogotá, Colombia, 2018.

- Tournadre, J. Anthropogenic Pressure on the Open Ocean: The Growth of Ship Traffic Revealed by Altimeter Data Analysis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 7924–7932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardain, A.; Sardain, E.; Leung, B. Global Forecasts of Shipping Traffic and Biological Invasions to 2050. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, J.R.; Bouchet, P.J.; Miller, D.L.; Evans, P.G.H.; Waggitt, J.; Ford, A.T.; Marley, S.A. Shipping in the North-East Atlantic: Identifying Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Change. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 179, 113681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirotta, E.; Booth, C.G.; Costa, D.P.; Fleishman, E.; Kraus, S.D.; Lusseau, D.; Moretti, D.; New, L.F.; Schick, R.S.; Schwarz, L.K.; et al. Understanding the Population Consequences of Disturbance. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 9934–9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, F.; Nicol, C.; Simmonds, M.P. Expert Assessment of the Impact of Ship-Strikesnon Cetacean Welfare Using the Welfare Assessment Tool for Wild Cetaceans. Anim. Welf 2023, 32, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, W.J.; Greene, C.R.; Malme, C.I.; Thomson, D.H. Marine Mammals and Noise; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt, R. Joint Industry Programme on Sound and Marine Life/Review of Existing Data on Underwater Sounds Produced by the Oil and Gas Industry; Seiche Measurements Ltd.: Holsworthy, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mechanics of Underwater Noise; Ross, D., Ed.; Pergamon Press: New York, NY, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Andrew, R.K.; Howe, B.M.; Mercer, J.A.; Dzieciuch, M.A. Ocean Ambient Sound: Comparing the 1960s with the 1990s for a Receiver off the California Coast. Acoust. Res. Lett. Online 2002, 3, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, R.K.; Howe, B.M.; Mercer, J.A. Long-Time Trends in Ship Traffic Noise for Four Sites off the North American West Coast. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2011, 129, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, N.R.; Price, A. Low Frequency Deep Ocean Ambient Noise Trend in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2011, 129, EL161–EL165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miksis-Olds, J.L.; Bradley, D.L.; Niu, X.M. Decadal Trends in Indian Ocean Ambient Sound. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2013, 134, 3464–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miksis-Olds, J.L.; Nichols, S.M. Is Low Frequency Ocean Sound Increasing Globally? J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2016, 139, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhardt, R.L.; Evans, W.E. Sound Activity of the California Gray Whale (Eschrichtius glaucus). J. Audio Eng. Soc. 1962, 10, 324–328. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings, W.C.; Thompson, P.O. Underwater Sounds from the Blue Whale, Balaenoptera Musculus. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1971, 50, 1193–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyack, P.L. Implications for Marine Mammals of Large-Scale Changes in the Marine Acoustic Environ-Ment. J. Mammal. 2008, 89, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.W.; Ellison, W.T.; Southall, B.L.; Hatch, L.; Van Parijs, S.M.; Frankel, A.; Ponirakis, D. Acoustic Masking in Marine Ecosystems: Intuitions, Analysis, and Implication. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2009, 395, 201–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyack, P.L.; Clark, C.W. Communicati4n and Acoustic Behavior of Dolphins and Whales. In Hearing by Whales and Dolphins; Au, W.W.L., Popper, A.N., Fay, R., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 156–224. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, C.D.G.; Randall Hughes, A.; Hultgren, K.M.; Miner, B.G.; Sorte, C.J.B.; Thornber, C.S.; Rodriguez, L.F.; Tomanek, L.; Williams, S.L. The Impacts of Climate Change in Coastal Marine Systems. Ecol. Lett. 2006, 9, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molinero, J.C.; Ibanez, F.; Souissi, S.; Licandro, P.; Buecher, E.; Dallot, S.; Nival, P. Northern Hemisphere Climate Impact on Mediterranean Zooplankton. In Proceedings of the 4th International Zooplankton Symposium: Human and Climate Forcing of Zooplankton Population, Temporal and Regional Responses of Zooplankton to Global Warming: Phenology and Poleward Displacement, Hiroshima, Japan, 28 May–1 June 2007; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Gambaiani, D.D.; Mayol, P.; Isaac, S.J.; Simmonds, M.P. Potential Impacts of Climate Change and Greenhouse Gas Emissions on Mediterranean Marine Ecosystems and Cetaceans. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. 2009, 89, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degollada, E.; Tort, B.; Amigó, N.; Martín, C.; Patón, D. A GIS Variability Model of Distribution of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus L.) Catalonian Coasts. In Cetaceans: Evolution, Behavior and Conservation; Patón, D., Ed.; Nova Science Publishing Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S.; Shimada, T.; Nakamura, S.; Nishiyama, N.; Yamashita, N.; Tanabe, S.; Tatsukawa, R. Specific Profile of Liver Microsomal Cytochrome P-450 in Dolphin and Whales. Mar. Environ. Res. 1989, 27, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, A.; Borrell, A.; Reijnders, P.J.H. Geographical and Temporal Variation in Levels of Organochlorine Contaminants in Marine Mammals. Mar. Environ. Res. 2002, 53, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar, A.; Borrell, A. DDT and PCB Reduction in the Western Mediterranean from 1987 to 2002, as Shown by Levels in Striped Dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba). Mar. Environ. Res. 2005, 59, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsili, L.; Jiménez, B.; Borrell, A. Persistent Organic Pollutants in Cetaceans Living in a Hotspot Area: The Mediterranean. In Marine Mammal Ecotoxicology; Fossi, C.M., Manti, C., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 185–212. [Google Scholar]

- Marsili, L.; Focardi, S. Organochlorine Levels in Subcutaneous Blubber Biopsies of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) and Striped Dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) from the Mediterranean Sea. Environ. Pollut. 1996, 91, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legler, J.; Brower, A. Are Brominated Flame Retardants Endocrine Disruptors? Environ. Int. 2003, 29, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnerud, P.O. Brominated Flame Retardants as Possible Endocrine Disrupters. Int. J. Androl. 2008, 31, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legler, J. New Insights into the Endocrine Disrupting Effects of Bromina-Ted Flame Retardants. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villanger, G.D.; Lydersen, C.; Kovacs, K.M.; Lie, E.; Skaare, J.U.; Jenssen, B.M. Disruptive Effects of Persistent Organohalogen Contaminants on Thyroid Function in White Whales (Delphinapterus leucas) from Svalbard. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 2511–2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simond, A.E.; Houde, M.; Lesage, V.; Michaud, R.; Zbinden, D.; Verreault, J. Associations between Organohalogen Exposure and Thyroid- and Steroid-Related Gene Responses in St. Lawrence Estuary Belugas and Minke Whales. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 145, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnerud, P. Toxic Effects of Brominated Flame Retardants in Man and in Wildlife. Environ. Int. 2003, 29, 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viberg, H. Neonatal Exposure to Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE 153) Disrupts Spontaneous Behaviour, Impairs Learning and Memory, and Decreases Hippocampal Cholinergic Receptors in Adult Mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2003, 192, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viberg, H.; Johansson, N.; Fredriksson, A.; Eriksson, J.; Marsh, G.; Eriksson, P. Neonatal Exposure to Higher Brominated Diphenyl Ethers, Hepta-, Octa-, or Nonabromodiphenyl Ether, Impairs Spontaneous Behavior and Learning and Memory Functions of Adult Mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2006, 92, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.; Giordano, G. Developmental Neurotoxicity of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE) Flame Retardants. Neurotoxicology 2007, 28, 1047–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, L.G.; de Laat, R.; Tagliaferri, S.; Pellacani, C. A Mechanistic View of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ether (PBDE) Developmental Neurotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 230, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirth, J.R.; Peden-Adams, M.M.; White, N.D.; Bossart, G.D.; Fair, P.A. In Vitro Exposure of DE-71, a penta-PBDE Mixture, on Immune Endpoints in Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and B6C3F1 Mice. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2015, 35, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsili, L.; Di Guardo, G.; Mazzariol, S.; Casini, S. Insights into Cetacean Immunology: Do Ecological and Biological Factors Make the Difference? Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, M.L.; Reif, J.S.; Bachand, A.; Ridgway, S.H. Opportunities for Using Navy Marine Mammals to Explore Associations between Organochlorine Contaminants and Unfavorable Effects on Reproduction. Sci. Total Environ. 2001, 274, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwacke, L.H.; Voit, E.O.; Hansen, L.J.; Wells, R.S.; Mitchum, G.B.; Hohn, A.A.; Fair, P.A. Probabilistic Risk Assessment of Reproductive Effects of Polychlorinated Biphenyls on Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from the Southeast United States Coast. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2002, 21, 2752–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khezri, A.; Lindeman, B.; Krogenæs, A.K.; Berntsen, H.F.; Zimmer, K.E.; Ropstad, E. Maternal Exposure to a Mixture of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) Affects Testis Histology, Epididymal Sperm Count and Induces Sperm DNA Fragmentation in Mice. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 329, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ylitalo, G.M.; Stein, J.E.; Hom, T.; Johnson, L.L.; Tilbury, K.L.; Hall, A.J.; Rowles, T.; Greig, D.; Lowenstine, L.J.; Gulland, F.M.D. The Role of Organochlorines in Cancer-Associated Mortality in California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 50, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, W.; He, P.; Wang, A.; Xia, T.; Xu, B.; Chen, X. Effects of PBDE-47 on Cytotoxicity and Genotoxicity in Human Neuroblastoma Cells in Vitro. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 2008, 649, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonefeld-Jorgensen, E.C.; Long, M.; Bossi, R.; Ayotte, P.; Asmund, G.; Krüger, T.; Ghisari, M.; Mulvad, G.; Kern, P.; Nzulumiki, P.; et al. Perfluorinated Compounds Are Related to Breast Cancer Risk in Greenlandic Inuit: A Case Control Study. Environ. Health 2011, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancia, A.; Abelli, L.; Fossi, M.C.; Panti, C. Skin Distress Associated with Xenobiotics Exposure: An Epigenetic Study in the Mediterranean Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus). Mar. Genom. 2021, 57, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowski, J.K.; Colemam, D.O. Environmental Hazards of Heavy Metals: Summary Evaluation of Lead, Cadmium and Mercury; MARC: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles, D. An Overview of the Concentrations and Effects of Metals in Cetacean Species. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 1999, 1, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Naggar, Y.; Khalil, M.S.; Ghorab, M.A. Environmental Pollution by Heavy Metals in the Aquatic Ecosystems of Egypt. Open Access J. Toxicol. 2018, 3, 555603. [Google Scholar]

- EEA—European Environment Agency. Contaminants in Europe’s Seas: Moving towards a Clean, Non-Toxic Marine Environment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, F.; Serrano, R.; Roig-Navarro, A.F.; Martínez-Bravo, Y.; López, F.J. Persistent Organochlorines and Organophosphorus Compounds and Heavy Elements in Common Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) from the Western Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2000, 40, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.M.K.; Bryan, C.E.; West, K.; Jensen, B.A. Trace Element Concentrations in Liver of 16 Species of Cetaceans Stranded on Pacific Islands from 1997 through 2013. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 70, 75–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Cegarra, A.M.; Jung, J.-L.; Orrego, R.; Padilha, J.d.A.; Malm, O.; Ferreira-Braz, B.; Santelli, R.E.; Pozo, K.; Pribylova, P.; Alvarado-Rybak, M.; et al. Persistence, Bioaccumulation and Vertical Transfer of Pollutants in Long-Finned Pilot Whales Stranded in Chilean Patagonia. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 770, 145259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, G.W. Pollution Due to Heavy Metals and Their Compounds. Mar. Ecol. 1984, 5, 1289–1431. [Google Scholar]

- Krone, C.; Robisch, P.; Tilbury, K.; Stein, J.; Mackey, E.; Becker, P.; Ohara, T.; Philo, L. Elements in Liver Tissues of Bowhead Whales (Balaena mysticetus). Mar. Mamm. Sci. 1999, 15, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Debacker, V.; Pillet, S.; Bouquegneau, J.-M. Heavy Metals in Marine Mammals. In Toxicology of Marine Mammals; Vos, J.G., Bossart, G.D., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2002; pp. 147–179. [Google Scholar]

- Kahle, J.; Zauke, G.P. Trace Metals in Antarctic Copepods from the Weddell Sea (Antarctica). Chemosphere 2003, 51, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Ikemoto, T.; Hokura, A.; Terada, Y.; Kunito, T.; Tanabe, S.; Nakai, I. Chemical Forms of Mercury and Cadmium Accumulated in Marine Mammals and Seabirds as Determined by XAFS Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 6468–6474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prowe, F.; Kirf, M.; Zauke, G.P. Heavy Metals in Crustaceans from the Iberian Deep-Sea Plain. Sci. Mar. 2006, 70, 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, J.P.; Santos, H.; Reis, A.T.; Falcao, J.; Rodrigues, E.T.; Pereira, M.E.; Duarte, A.C.; Pardal, M.A. Mercury Bioaccumulation in the Spotted Dogfish (Scyliorhinus canicula) from the Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2010, 60, 1372–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakimska, A.; Konieczka, P.; Skóra, K.; Namiésnik, J. Bioaccumulation of metals in tissues of marine animals, part I: The role and impact of heavy metals on organisms. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2011, 20, 1117–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Jakimska, A.; Konieczka, P.; Skóra, K.; Namiésnik, J. Introduction bioaccumulation of metals in tissues of marine animals, part II: Metal concentrations in animal tissues. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2011, 20, 1126–1127. [Google Scholar]

- Dehn, L.A.; Follmann, E.H.; Rosa, C.; Duffy, L.K.; Thomas, D.L.; Bratton, G.R.; Taylor, R.J.; Ohara, T.M. Stable Isotope and Trace Element Status of Subsistence-Hunted Bowhead and Beluga Whales in Alaska and Gray Whales in Chukotka. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2006, 52, 301–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Coppola, D.; Baini, M.; Giannetti, M.; Guerranti, C.; Marsili, L.; Panti, C.; De Sabata, E.; Cló, S. Large Filter Feeding Marine Organisms as Indicators of Microplastic in the Pelagic Environment: The Case Studies of the Mediterranean Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) and Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus). Mar. Environ. Res 2014, 100, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desforges, J.-P.W.; Galbraith, M.; Ross, P.S. Ingestion of Microplastics by Zooplankton in the Northeast Pacific Ocean. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2015, 69, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt-Holm, P.; N’Guyen, A. Ingestion of Microplastics by Fish and Other Prey Organisms of Cetaceans, Exemplified for Two Large Baleen Whale Species. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 144, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Germanov, E.S.; Marshall, A.D.; Bejder, L.; Fossi, M.C.; Loneragan, N.R. Microplastics: No Small Problem for Filter-Feeding Megafauna. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018, 33, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrini, F.; Mari, L.; Casagrandi, R. Modelling Plastics Exposure for the Marine Biota: Risk Maps for Fin Whales in the Pelagos Sanctuary (North-Western Mediterranean). Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fossi, M.C.; Panti, C.; Guerranti, C.; Coppola, D.; Giannetti, M.; Marsili, L.; Minutoli, R. Are Baleen Whales Exposed to the Threat of Microplastics? A Case Study of the Mediterranean Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 2374–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gómez, J.C.; Garrigós, M.; Garrigós, J. Plastic as a Vector of Dispersion for Marine Species with Invasive Potential. A Review. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 629756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, I.; Angeletti, D.; Giovani, G.; Paraboschi, M.; Arcangeli, A. Cetacean Sensitivity and Threats Analysis to Assess Effectiveness of Protection Measures: An Example of Integrated Approach for Cetacean Conservation in the Bonifacio Bouches. Biodivers. Conserv. 2022, 31, 517–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazau, D.; Nguyen Hong Duc, P.; Druon, J.-N.; Matwins, S.; Fablet, R. Multimodal Deep Learning for Cetacean Distribution Modeling of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Mach. Learn. 2023, 112, 2003–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A.; Harris, D.; Tyack, P.; Matias, L. Fin Whale Acoustic Presence and Song Characteristics in Seas to the Southwest of Portugal. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 147, 2235–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Stephanis, R.; Cornulier, T.; Verborgh, P.; Salazar Sierra, J.; Gimeno, N.P.; Guinet, C. Summer Spatial Distribution of Cetaceans in the Strait of Gibraltar in Relation to the Oceanographic Context. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2008, 353, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveros, J.C. Venny 2.1.0. Available online: https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/venny/index.html (accessed on 26 October 2020).

- Academo Venn Diagram Generator|Academo.org—Free, Interactive, Education. Available online: https://academo.org/demos/venn-diagram-generator/ (accessed on 13 December 2023).

- EMSA EU Vessel Density Map. EMOD Net-Human Activities. Es Detailed Method 2019. Available online: https://www.emodnethumanactivities.eu/documents/Vessel%20density%20maps_method_v1.5.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Lockyer, C. Body Weights of Some Species of Large Whales. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1976, 36, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigoni, M.; Manfredi, P.; Panigada, S.; Bramanti, L.; Santangelo, G. Life-history Tables of the Mediterranean Fin Whale from Stranding Data. Mar. Ecol. 2011, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geraci, J.R.; Lounsbury, V.J. Marine Mammals Ashore: A Field Guide for Strandings; National Aquarium: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- García-Barón, I.; Authier, M.; Caballero, A.; Vázquez, J.A.; Santos, M.B.; Murcia, J.L.; Louzao, M. Modelling the Spatial Abundance of a Migratory Predator: A Call for Transboundary Marine Protected Areas. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 346–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D. Using Oceanographic Features to Predict Areas of High Cetacean Diversity. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Wales, Bangor, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Geijer, C.K.A.; Notarbartolo di Sciara, G.; Panigada, S. Mysticete Migration Revisited: Are Mediterranean Fin Whales an Anomaly? Mamm. Rev. 2016, 46, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauffier, P.; Borrell, A.; Silva, M.A.; Víkingsson, G.A.; López, A.; Giménez, J.; Colaço, A.; Halldórsson, S.D.; Vighi, M.; Prieto, R.; et al. Wait Your Turn, North Atlantic Fin Whales Share a Common Feeding Ground Sequentially. Mar. Environ. Res. 2020, 155, 104884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez, J.; Gómez-Campos, E.; Borrell, A.; Cardona, L.; Aguilar, A. Isotopic Evidence of Limited Exchange between Mediterranean and Eastern North Atlantic Fin Whales. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2013, 27, 1801–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parona, C. Catture Recenti Di Grandi Cetacei Nei Mari Italiani. Atti Soc. Lingustica Sci. Nat. Geogr. 1908, 19, 173–205. [Google Scholar]

- Borri, C. Una Notabile Comparsa Di Grandi Cetacei Nell’Arcipelago Toscano. Monit. Zool. Ital. 1927, 38, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Richard, J. Documents Sur Les Cétacés et Les Pinnipèdes Provenant Des Campagnes de Prince Albert 1ére de Monaco. Résult. Camp. Scien. Albert 1ére 1936, 94, 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus, M. Les baleinoptères de la Méditerranée. Bull. Mus. Hist. Nat. Marseille 1966, 26, 117–139. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. V—Année 1975. Mammalia 1976, 40, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, E.; Aguilar, A.; Filella, S. Cetaceans Stranded, Captured or Sighted in the Spanish Coasts during 1976–1979. Butl. Inst. Catalana Hist. Nat 1980, 45, 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Marchessaux, D. A Review of the Current Knowledge of the Cetaceans in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. Vie Mar. 1980, 2, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzoli, I. Note Préliminaire: Étude Des Cétacés Dans Le Bassin Liguro-Provençal Par Observation Directe à La Mer. Rapport de La Commission Internationale Pour l’Exploration. Sci. De La Mer Méditerranée 1983, 28, 217–218. [Google Scholar]

- Raga, J.A.; Raduán, A.; Blanco, C. Contribución al estudio de la distribución de cetáceos en el Mediterráneo y Atlántico Ibérico. Misc. Zool. 1985, 9, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Viale, D. Une méthode synoptique de recherche des zones productives en mer: Détection simultanée des cétacés, des fronts thermiques et des biomasses sous-jacentes. Ann. Inst. Oceanogr. Monaco. 1991, 67, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, A. Nouvelles données sur Balaenoptera physalus en Méditerranée occidentale. A. Rapp. Comm. Int. Pour l’explor. Sci. Méditerranée 1986, 30, 244. [Google Scholar]

- Viale, D.; Moriaz, C.; Palazzoli, I.; Viale, A.; Viale, C. Repérage Aérien de Cétacés En Mer Ligure. Rapp. Comm. Int. Pour l’explor. Sci. Méditerranée 1986, 30, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Viale, D.; De Crescenzo, J.N.; Erlich, I.; Isetti, A.M. Cétacés En Méditerranée Orientale: Campagnes CETORIENT Sur N/O Le Surlot IFREMER. Rapp. Comm. Int. Pour l’explor. Sci. Méditerranée 1988, 31, 289. [Google Scholar]

- Gannier, A.; Gannier, O. Some Sightings of Cetaceans in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1989, 3, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gannier, A.; Gannier, O. Northwestern Mediterranean Survey: 4th Annual Report. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1992, 6, 56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gannier, A.; Gannier, O. The Winter Presence of the Fin Whale in the Liguro-Provençal Basin: Preliminary Study. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1993, 7, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Viale, D.; Terris, N. Indice d’abondance de La Megafaune En Méditerranée. Rapp. Comm. Int. Pour l’explor. Sci. Méditerranée 1990, 32, 76. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, D.D.K.; Adloff, B. Surface Frequency of Cetaceans in the Strait of Gibraltar. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1991, 5, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, F.; Lauriano, G. Greenpeace Report on Two-Year Research in the Ligurian Sea. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1992, 6, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Politi, E.; Bearzi, M.; Notarbartolo-Di-Sciara, G.; Cussino, E.; Gnone, G. Distribution and Frequency of Cetaceans in the Waters Adjacent to the Greek Ionian Islands. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1992, 6, 75–78. [Google Scholar]

- Relini, G.; Orsi Relini, L.; Cima, C.; Fasciana, C.; Fiorentino, F.; Palandri, G.; Relini, M.; Tartaglia, M.P.; Torchia, G.; Zamboni, A. Macroplancton, Meganyctiphanes Norvegica, and Fin Whales, Balaenoptera physalus, along Some Transects in the Ligurian Sea. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1992, 6, 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- Zanardelli, M.; Notarbartolo-Di-Sciara, G.; Jahoda, M. Photo-Identification and Behavioural Observations of Fin Whales Summering in the Ligurian Sea. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1992, 6, 86–89. [Google Scholar]

- Pulcini, M.; Angradi, A.M.; Sanna, A. Distribution and Frequency of Cetaceans in the Ligurian-Provençal Basin and in the North Tyrrhenian Sea (Mediterranean sea). Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1993, 7, 144–147. [Google Scholar]

- Boutiba, Z. Bilan de nos connaissances sur la présence des cétacés le long des côtes algériennes. Mammalia 1994, 58, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutiba, Z. Cetaceans in Algerian coastal waters. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1994, 8, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Politi, E.; Airoldi, S.; Notarbartolo-Di-Sciara, G. A Preliminary Study of the Ecology of Cetaceans in the Waters Adjacent to Greek Ionian Islands. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1994, 8, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Relini, G.; Orsi Relini, L.; Siccardi, A.; Fiorentino, F.; Palandri, G.; Torchia, G.; Relini, M.; Cima, C.; Cappello, M. Distribuzione Di Meganyctiphanes Norvegica e Balaenoptera physalus in Mar Ligure All’inizio Della Primavera. Biol. Mar. Mediterr. 1994, 1, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, A.; Arena, R.; Cane, A.; Guerrieri, G.; Petralia, R.; Trincali, L.M.; Vazzana, L. Risultati Della Ricerca Cetofauna Siciliana. Museo Del Mare Di Cefalù. Grup. Ric. Cetacei 1995, 6, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, B. Marine Mammals’ Inventory of Turkey. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1995, 9, 96–98. [Google Scholar]

- Boutiba, Z.; Hamoutene, D.; Merzoug, D.; Bouderbala, M.; Taleb, M.Z.; Abdelghani, F. Le Rorqual Commun (Balaenoptera physalus) Dans Le Bassin Sud de La Méditerranée Occidentale: État Actuel Des Observations. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference RIMMO, Antibes, France, 15–17 November 1996; pp. 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cerioni, S.; Forni, L.; Lo Tenero, A.; Nannarelli, S.; Pulcini, M. A Cetacean Survey in the Taranto Gulf: Work in Progress. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1996, 9, 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Guibourge, E.; Frodello, J.P.; Terris, N.; Viale, F. Les Baleines Ont-Elles La Rougeole? Unvirus Mortel s’attaque à l’unique Espèce de Baleine En Méditerranée. La Recherche 1996, 283, 34–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lauriano, G.; Notarbartolo-Di-Sciara, G. The Distribution of Cetaceans off North-Western Sardinia. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1996, 9, 104–106. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, L.; Carpentieri, P.; Consiglio, C. Presence and Distribution of the Cetological Fauna of the Aegean Sea: Preliminary Results. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1996, 9, 99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Barberis, S.; Davico, A.; Davico, L.; Massajoli, M.; Trucchi, R. The Third WWF Research Campaign in the Ligurian Sea. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1997, 11, 99. [Google Scholar]

- Beaubrun, P.; David, L.; Di Meglio, N.; Gannier, A.; Gannier, O. First Aerial Survey in the North-West Mediterranean: Preliminary Results. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1997, 11, 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Gannier, A. Summer Abundance Estimates of Striped Dolphins and Fin Whales in the Area of the Future International Marine Sanctuary. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1997, 11, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Lauriano, G. Preliminary Observations of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) off North-Western Sardinia. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1997, 11, 122–124. [Google Scholar]

- Stanzani, L.A.; Bonomi, L.; Bortolotto, A. Onde Dal Mare’: An Update on the Italian Network for Cetacean and Turtle Sightings. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1997, 11, 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Mussi, B.; Gabriele, R.; Miragliuolo, A.; Battaglia, M. Cetacean Sightings and Interactions with Fisheries in the Archipelago Pontino Campano, Southern Tyrrhenian Sea, 1991. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1998, 12, 63–65. [Google Scholar]

- Airoldi, S.; Azzellino, A.; Nani, B.; Ballardini, M.; Bastoni, C.; Notarbartolo-di-Sciara, G.; Sturlese, A. Whale-watching in Italy: Results of the first three years of activity. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1999, 13, 153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cañadas, A.; Sagarminaga, R.; Hernández-Falcón, L.; Fernández, E.; Fernández, M. Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Northern Part of the Alboran Sea and Strait of Gibraltar. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1999, 13, 300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Carpentieri, P.; Corsini, M.; Marini, L. Contribute to the Knowledge of the Presence and Distribution of Cetaceans in the Aegean Sea. Atti Soc. Ital. Sci. Nat. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Milano 1999, 140, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lauriano, G.; Tunesi, L.; Notarbartolo-Di-Sciara, G.; Salvati, E.; Cardinali, A. The Role of Cetaceans in the Zoning Proposal of Marine Protected Areas: The Case of the Asinara Island MPA. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1999, 13, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Mussi, B.; Miragliuolo, A.; Monzini, E.; Diaz Lopez, B.; Battaglia, M. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Feeding Ground in the Coastal Waters of Ischia (Archipelago campano). Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1999, 13, 330–335. [Google Scholar]

- Sanna, A.; Blasi, B.; Corain, D.; Falasconi, R.; Castañeda-Moreno, J.A. Cetaceans Sighting in the North-Western Mediterranena Sea. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1999, 13, 259. [Google Scholar]

- Trucchi, R.; Ottonello, C.; Tribocco, F. The First Experience of a Daily Whale Watching Activity to Collect Data and to Inform People about Cetacean Biology and Ecology Carried out by WWF—Liguria. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1999, 13, 271–273. [Google Scholar]

- Zanardelli, M.; Panigada, S.; Airoldi, S.; Borsani, J.F.; Jahoda, M.; Notarbartolo-Di-Sciara, G. Site Fidelity, Seasonal Residence and Sex Ratio of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Ligurian Sea Feeding Grounds. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 1999, 12, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Affronte, M. Balenottere a Frotte in Alto Adriatico. Cetacea Inf. 2000, 9, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Aïssi, M.; Celona, A.; Comparetto, G.; Mangano, R.; Würtz, M.; Moulins, A. Large-Scale Seasonal Distribution of Fin Whales (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Central Mediterranean Sea. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. 2008, 88, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laran, S.; Gannier, A. Spatial and Temporal Prediction of Fin Whale Distribution in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2008, 65, 1260–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerem, D. Update on the Cetacean Fauna of the Mediterranean Levantine Basin. Open Mar. Biol. J. 2012, 6, 6–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, R.; Sperone, E.; Tringali, M.L.; Pellegrino, G.; Giglio, G.; Tripepi, S.; Arcangeli, A. Summer Distribution, Relative Abindance and Encounter Rates of Cetaceans in the Mediterranean Waters off Southern Italy (Western Ionian Sea and Southern Tyrrhenian Sea). Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2015, 16, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorietti, M.; Atzori, F.; Carosso, L.; Frau, F.; Pellegrino, G.; Sarà, G.; Arcangeli, A. Cetacean Presence and Distribution in the Central Mediterranean Sea and Potential Risks Deriving from Plastic Pollution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 173, 112943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, F.; Lahaye, E.; Moulins, A.; Borroni, A.; Rosso, M.; Tepsich, P. Locating Ship Strike Risk Hotspots for Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) and Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus) along Main Shipping Lanes in the North-Western Mediterranean Sea. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 212, 105820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, G.S.; Lahaye, E.; Rosso, M.; Moulins, A.; Hines, E.; Tepsich, P. Predicting Summer Fin Whale Distribution in the Pelagos Sanctuary (North-western Mediterranean Sea) to Identify Dynamic Whale–Vessel Collision Risk Areas. Aquat. Conserv. 2021, 31, 2257–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.; Arcangeli, A.; Tepsich, P.; Di-Meglio, N.; Roul, M.; Campana, I.; Gregorietti, M.; Moulins, A.; Rosso, M.; Crosti, R. Computing Ship Strikes and near Miss Events of Fin Whales along the Main Ferry Routes in the Pelagos Sanctuary and Adjacent West Area, in Summer. Aquat. Conserv. 2022, 32, 442–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canales, R.M.; Méndez, A.; Giménez, F.; Mengual, R.M.; Férnandez, F. Avistamiento de Cetáceos En La Región de Murcia. In Proceedings of the Cuarto Congreso de la Naturaleza de la Región de Murcia y Primero del Sureste Ibérico, Murcia, Spain, 19–21 November 2008; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- FIRMM. Informe de Investigación Sobre Rorcuales Comunes en el Estrecho de Gibraltar. Available online: https://www.firmm.org/es/investigacion/rorcuales-comunes (accessed on 5 February 2023).

- Edmaktub. Resultados: Las Ballenas se Alimentan en la Costa del Garraf y en el Mar Balear. Available online: https://edmaktub.org/resultados/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Degollada, E.; Amigó, N.; O’Callaghan, S.; Varola, M.; Ruggero, K.; Tort, B. A Novel Technique for Photo-Identification of the Fin Whale, Balaenoptera physalus, as Determined by Drone Aerial Images. Drones 2023, 7, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada, R.; Feliu-Tena, B.; Tort-Castro, B.; Martin, E.; Olaya- Ponzone, L.; Patón, D.; Belda, E.; Anfruns, I.; Onrubia, A.; Degollada, E.; et al. Advances in the Knowledge of the Mediterranean- Atlantic Migration of the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Iberian Mediterranean Corridor. Data Collection, Migration, Periods, and Swimming Speeds. Eur. Cetacean Soc. O’Grove 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Rallo, G. I cetacei dell’Adriatico. WWF Veneto 1979, 4, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Marini, L.; Consiglio, C.; Angradi, A.M.; Catalano, B.; Sanna, A.; Valentini, T.; Finoia, M.G.; Villetti, G. Distribution, Abundance and Seasonality of Cetaceans Sighted during Scheduled Ferry Crossings in the Central Tyrrhenian Sea: 1989–1992. Ital. J. Zool. 1996, 63, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littaye, A.; Gannier, A.; Laran, S.; Wilson, J.P.F. The Relationship between Summer Aggregation of Fin Whales and Satellite-Derived Environmental Conditions in the Northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Remote Sens. Environ. 2004, 90, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmaktub Proyecto Rorcual y Biodiversidad En La Costa Catalana. Contribución a La Mejora Del Conocimiento Del Rorcual Común En Las Costas de Cataluña. Available online: https://edmaktub.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Proyecto-Rorcual-y-Biodiversidad.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Medio Ambiente. Las Ballenas Más Grandes Del Mediterráneo Pasan Por Torrevieja. Available online: https://cadenaser.com/emisora/2017/05/18/radio_alicante/1495111725_859581.html (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Bézie, G. Observation d’un Rorqual Commun Devant Bastia. Available online: https://france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr/corse/haute-corse/video-observation-rorqual-commun-devant-bastia-1462167.html (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Animaux. Méditerranée—Narbonne-Plage: Deux Baleines de 20 Mètres Filmées au Large du Littoral Audois. Available online: https://www.lindependant.fr/2020/08/18/mediterranee-narbonne-plage-deux-baleines-de-20-metres-filmees-au-large-du-littoral-audois-9024335.php (accessed on 3 June 2021).

- Frayssinet, C. A Marseille, Deux Rorquals Ont été Observés au Large des Calanques. Available online: https://www.geo.fr/environnement/a-marseille-deux-rorquals-ont-ete-observes-au-large-des-calanques-200427 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Insolite, P.-O. Un Rorqual Commun à L’entrée du Port de Sainte-Marie-la-Mer. Available online: https://www.lindependant.fr/2020/09/17/un-rorqual-commun-a-lentree-du-port-9078617.php (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Agustí, C. Una Ballena Visita la Playa de Barcelona. La Vanguardia. Available online: https://www.lavanguardia.com/participacion/las-fotos-de-loslectores/20210421/6987169/ballena-visita-playa-barcelona.html (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Romero, S. La Segunda Ballena Más Grande Del Mundo, Avistada En España. Available online: https://www.muyinteresante.es/naturaleza/articulo/la-segunda-ballena-mas-grande-del-mundo-avistada-en-espana-631625128089 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Sociedad. Avistadas las Primeras Ballenas del Año en la Costa de Barcelona. Available online: https://www.elperiodico.com/es/sociedad/20210215/video-avistadas-ballenas-barcelona-11522168 (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Vivir en Barcelona. VÍDEO: Dos Ballenas se Pasean Por la Costa de Barcelona. Available online: https://www.metropoliabierta.com/vivir-en-barcelona/ballenas-costa-barcelona_37580_102.html (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Elcacho, J. El Impresionante Salto de La Segunda Ballena Más Grande Del Mundo Frente a Barcelona. Available online: https://www.lavanguardia.com/natural/20220531/8305291/impresionante-salto-segunda-ballena-mas-grande-mundo-frente-barcelona.html (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Viale, D.; Frontier, S. Surface megafauna related to western Mediterranean circulation. Aquat. Living Resour. 1994, 7, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belenguer, R.; Kersting, D.K. Cetáceos En La Reserva Marina de Las Islas Columbretes (Mediterráneo noroccidental): 20 Años de Avistamientos Oportunistas. Mediterr. Ser. Estud. Biol. 2011, 22, 100–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrag, M.M.S. Marine Mammals on the Egyptian Mediterranean Coast “Records and Vulnerability. Int. J. Ecotoxicol. Ecobiol. 2019, 4, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Banco de Datos de Biodiversidad—Banco de Datos de Biodiversidad—Generalitat Valenciana. Available online: https://bdb.gva.es/es/ (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- Halpin, P.; Read, A.; Fujioka, E.; Best, B.; Donnelly, B.; Hazen, L.; Kot, C.; Urian, K.; LaBrecque, E.; Dimatteo, A.; et al. OBIS-SEAMAP: The World Data Center for Marine Mammal, Sea Bird, and Sea Turtle Distributions. Oceanography 2009, 22, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalbes, P. OBIS-SEAMAP. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/876 (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Cañadas, A. Alnitak-Alnilam Cetaceans and Sea Turtles Surveys Off Southern Spain. OBIS-SEAMAP. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/429 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Kerem, D. OBIS-SEAMAP. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/819 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Happywhale. Fin Whale in North Atlantic Ocean. OBIS-SEAMAP. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/1750 (accessed on 4 September 2022).

- Maughan, B.K.; Arnold. OBIS-SEAMAP. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/64 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Bedocchi, D.; Nuti, S. CE.TU.S. Research Cetacean Sightings in the North Tuscany and Tuscan Archipelago Waters, 1997–2011. OBIS-SEAMAP. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/732 (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Bellingeri, M. Acquario Di Genova, Delfini Metropolitani Project, Cetacean Sightings 2001–2009. OBIS-SEAMAP. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/761 (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Diaz Lopez, B.; Bottlenose Dolphin Research Institute (BDRI). Cetacean Sightings 2011. OBIS-SEAMAP. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/83 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Fanizza, C. Jonian Dolphin Conservation Di Taranto Marine Mammal Sightings 2009–2012. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/812 (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Boisseau, O. Visual Sightings from Song of the Whale 1993–2013. OBIS-SEAMAP. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/1158 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Fossati, C.; Romè, G. Visual Contacts from Research Cruises in the Med Sea, 1994–2001. OBIS-SEAMAP. 2014. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/1078 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Lanfredi, C.; di Sciara, N. Tethys Research Institute Aerial Survey Cetacean Sightings 2009–2011. OBIS-SEAMAP. 2011. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/776 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Lanfredi, C.; di Sciara, N. Tethys Research Institute Shipboard Survey Cetacean Sightings 1986-OBIS-SEAMAP. 2014. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/774 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Aissi, M.; Wdcs, A.A. Cetacean Coordinated Transborder Monitoring Using Ferries as Platforms of Observation off Tunisia 2013–2014 OBIS-SEAMAP. 2015. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/1263 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Tingali, M.L.; Wdcs, A.A. Cetacean Coordinated Transborder Monitoring Using Ferries as Platforms of Observation off Tunisia 2013–2014. OBIS-SEAMAP. 2015. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/1264-Ketos (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Arcangeli, A.; Campana, I.; Paraboschi, M.; ISPRA. Presence of Cetacean Species Collected through Fixed-Line-Transect Monitoring across the Western Mediterranean Sea (Civitavecchia-Barcelona Route) between 2014 and 2018; ISPRA: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, S. OceanCare Cetacean Sightings 2001-OBIS-SEAMAP. 2015. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/66 (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Frey, S. Ocean Care Cetacean Sightings in Sicily, Italy 2016–2019. OBIS-SEAMAP. 2019. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/2038 (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Azzolin, M. Adriatic and Ionian Sea Mega-Fauna Monitoring Employing Ferry as Platform of Observation along the Ancona-Igoumenitsa-Patras Lane from December 2014 to December 2018; Gaia Research Institute: Onlus, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://marineinfo.org/id/dataset/6546 (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Azzolin, M.; Giacoma, C. Dolphins and Sea Turtle Monitoring in the Pelagie Archipelago (Italy) from 2004 to 2006; Life and System Biology Department, University of Turin: Turin, Italy, 2020; Available online: https://marineinfo.org/id/dataset/ (accessed on 25 April 2023).

- Monaco, C.; Garofalo, D.; Raffa, A.; Mare Camp Association. Presence of Cetaceans and Sea Turtles in the Gulf of Catania, Eastern Sicily, Ionian Sea (Surveys 2015–2019). 2020. Available online: https://marineinfo.org/id/dataset/6529 (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Scuderi, A.; Martín, E. Cetacean Monitoring Programme along Fixed Transect Using Ferries as Platforms in the Strait of Gibraltar, 2018, FLT Med Network. 2020. Available online: https://marineinfo.org/id/dataset/6443 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Doremus, G. Observatoire Pelagis Boat Surveys 2003–2021. OBIS-SEAMAP. 2022. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/1403 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Van Canneyt, O. Observatoire Pelagis Aerial Surveys 2002–2021. OBIS-SEAMAP. 2022. Available online: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/dataset/1404 (accessed on 16 January 2022).

- Torreblanca, E.; Camiñas, J.A.; Macías, D.; García-Barcelona, S.; Real, R.; Báez, J.C. Using Opportunistic Sightings to Infer Differential Spatio-Temporal Use of Western Mediterranean Waters by the Fin Whale. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangi, M.; Airoldi, S.; Beneduce, L.; Zaccone, C. Wild Whale Faecal Samples as a Proxy of Anthropogenic Impact. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar Vila, A.; Forcada i Nogués, J.; Arderiu i Bofill, A.; Borrell i Thió, A.; Monnà Cano, A.; Aramburu Galeano, M.J.; PastorRamos, T.; Cantos i Font, G. Inventario de Los Cetáceos de Las Aguas Atlánticas Peninsulares: Aplicación de laDirectiva 92/43/CEE. 1997. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/content/dam/miteco/es/biodiversidad/publicaciones/bm_bbdd_inventario_atlanticas_tcm30-522305.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2021).

- Stockin, K.A.; Burgess, E.A. Opportunistic Feeding of an Adult Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) Migrating along the Coast of Southeastern Queensland, Australia. Aquat. Mamm. 2005, 31, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, J.; Lemckert, C.; Meynecke, J.-O. Coastal Fronts Utilized by Migrating Humpback Whales, Megaptera Novaeangliae, on the Gold Coast, Australia. J. Coast. Res. 2016, 75, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espada Ruíz, R.; Olaya-Ponzone, L.; García-Gómez, J.C. Humpback Whale in the Bay of Algeciras and a Mini-Review of This Species in the Mediterranean. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2018, 24, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero, J.C.; Ibanez, F.; Souissi, S.; Bosc, E.; Nival, P. Surface Patterns of Zooplankton Spatial Variability Detected by High Frequency Sampling in the NW Mediterranean. Role of Density Fronts. J. Mar. Syst. 2008, 69, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, D. Influence of Ocean Fronts on Cetacean Habitat Selection and Diversity within the CalCOFI Study Area; Center for Marine Biodiversity and Conservation: San Diego, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Ocean Ecology Laboratory, Ocean Biology Processing Group. MODIS-Aqua Level 3 Mapped Chlorophyll Data Version R2018. 2018. Available online: https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/10.5067/AQUA/MODIS/L3M/CHL/2018/ (accessed on 20 June 2022).

- Biswas, A.K.; Tortajada, C. Impacts of the High Aswan Dam. In Water Resources Development and Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 379–395. [Google Scholar]

- Ritter, F.; Panigada, S. World Seas-An Evironmental Evaluation-Volume III: Ecological Issues and Environmental Impacts; Shepperd, C., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, R.; Calvet, J. Recherches Faites Sur Le Cétacé Capturé a Cètte, Le 6 Octobre 1904—Balaenoptera physalus (Linné). Bull. De La Soc. Phil. 1905, 7, 72–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ficalbi, E. Una balenottera arenata sul litorale toscano. Monit. Zool. Ital. 1907, 18, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Lepri, G. Su di una balenottera arenatasi presso Ostia. Boll. Soc. Zool. Ital. 1914, 3, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ficalbi, E. Tre grandi cetacei dati in secco sul litorale toscano. Monit. Zool. Ital. 1919, 30, 199–200. [Google Scholar]

- Pierantoni, N. La Balaenoptera physalus (L.) arenatasi sulla spiaggia di S. Giovanni a Teduccio. Boll. Soc. Nat. Napoli. 1930, 41, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Flower, S.S. Notes on recent mammals of Egypt, with a list of the species recorded from that kingdom. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond. 1932, 102, 369–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamino, G. Note Sui Cetacei. VIII. Rinvenimento Di Una Giovane Balenottera Arenata Sulla Spiaggia Dei Maronti (Isola d’Ischia), Il 16 Novembre 1953. Atti Soc. Ital. Sci. Nat. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Milano 1953, 92, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Tamino, G. Ricupero Di Una Balenottera Arenata Sul Lido Di Salerno Il 10 Febbraio 1953. Boll. Zool. 1953, 20, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamino, G. Note Sui Cetacei Italiani: Rinvenimento Di Una Balenottera Nel Golfo Di La Spezia (9 Giugno 1955). Atti Soc. Ital. Sci. Nat. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Milano 1956, 95, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Postel, E. Echouage d’une baleinoptère aux Iles Kerkennah. Bull. SOS 1956, 53, 75–76. [Google Scholar]

- Parenzan, P. A proposito di una balenottera arenata nel gennaio 1957 nell’isola di Ponza. Thalass. Jonica. 1958, 1, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Pavletič, J.; Canadjija, S.; Magerle, A. Skelet Kita Perajara—Balaenoptera physalus (L.). Biolo Ki Glasnik. 1962, 15, 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Chakroun, F. Captures d’animaux rares en Tunisie. Bull. Inst. Natn. Scient. Tech. Océanogr. Pêche Salammbô. 1966, 1, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R.; Budker, P. Rapport Annuel Sur Les Cétacés Et Pinnnipèdes Trouvés Sur Les Côtes De Fance. Mammalia 1972, 36, 517–520. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. II—Année 1972. Mammalia 1973, 37, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. III—Année 1973. Mammalia 1974, 38, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. IV—Année 1974. Mammalia 1975, 39, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. VI—Année 1976. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit 1977, 6, 308–317. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. VII—Année 1977. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1978, 6, 333–344. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. VIII—Année 1978. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1979, 6, 463–474. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et les pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France, IX Année 1979. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1980, 6, 615–632. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. X—Année 1980. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1981, 6, 803–818. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. XI—Année 1981. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1982, 6, 969–984. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. XII—Année (1982). Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1983, 7, 121–135. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. XIV—Année 1984. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1985, 7, 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. XV—Année 1985. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1986, 7, 507–522. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. XVI—Année 1986. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1987, 7, 617–639. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. XVII—Année 1987. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1988, 7, 753–769. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur les cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur les côtes de France. XVIII—Année 1988. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1989, 7, 781–808. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur le cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur le côtes de France. XX—Année 1990. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1990, 7, 1017–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Duguy, R. Rapport annuel sur le cétacés et pinnipèdes trouvés sur le côtes de France. XXI—Année 1991. Ann. Soc. Sci. Nat. Charente-Marit. 1992, 8, 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Casinos, A.; Filella, S. Primer Recull Anual (1973) de La Comissió de Cetologia de La Institució Catalana d’Història Natural. Butl. Inst. Catalana Hist Nat. 1975, 39, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Casinos, A.; Vericad, J.S. The Cetaceans of the Spanish Coasts: A Survey. Mammalia 1976, 40, 267–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natale, D.; Giuffré, A. Su Di Un Esemplare Di Balaenoptera physalus L. (Cetacea, Misticeti) Arenato Lungo Il Litorale Tirrenico Della Sicilia. Mem. Biol. Mar. Ocean. 1976, 6, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Princi, M.; Bussani, M. Determinazione Di Hg in Un Esemplare Di Balaenoptera physalus L. Catturato Nel Porto Di Trieste. Boll. Pesca Piscic. Idrobiol. 1976, 31, 93–95. [Google Scholar]

- Pilleri, G.; Gihr, M. Some Records of Cetaceans in the Northern Adriatic Sea. N. Adriat. Sea. Investig. Cetacea 1977, 8, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrí, J. Recull de La Comisió de Cetologia de La Institució Catalana d’història Natural. II: Anys 1974 i 1975. Butl. Inst. Catalana Hist. Nat 1980, 45, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ktari-Chakroun, F. Nouvelles mentions de cétacés en Tunisie. Bull. Inst. Oceanogr. Pêche Salammbô. 1981, 8, 119–121. [Google Scholar]

- Spanier, E. Whales on Israel’s Coasts? Isr. Land Nat. 1981, 71, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Poggi, R. Recenti incrementi alla collezione cetologica del Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Genova (Mammalia, Cetacea). Ann. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Genova. 1982, 84, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Mustapha, K. Echouage d’un rorqual commun Balaenoptera physalus (Linné 1758) à Carthage Dermech dans le Golfe de Tunis. Bull. Inst. Natn. Scient. Tech. Océanogr. Pêche Salammbô. 1986, 13, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Cagnolaro, L.; Cozzi, B.; Magnaghi, L.; Podestà, M.; Poggi, R.; Tangerini, P. Su 18 cetacei spiaggiati sulle coste italiane dal 1981 al 1985: Rilevamento biometrico ed osservazioni necroscopiche (Mammalia: Cetacea). Atti Soc. Ital. Sci. Nat. Mus. Civ. Stor. Nat. Milano. 1986, 127, 79–106. [Google Scholar]

- Grau, E.; Filella, S.; Raga, J.A.; Raduán, A. Cetáceos varados en las costas del Mediterráneo ibérico, durante los años 1980–1981. Misc. Zool. 1986, 10, 353–358. [Google Scholar]

- El Bouali, M. Les cétacés du littoral ouest algérien. Ph.D. Thesis, Département de Biologie Animale, Option Biologie Marine, Université d’Óran, Oran, Algeria, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Mendelssohn, H.; Yom-Tov, Y. Plants and Animals of the Land of Israel. Mammals. Ministry of Defense; The Publishing House: Tel Aviv, Israel, 1987; Volume 7, pp. 1–295. [Google Scholar]

- Raga, J.A.; Raduán, A.; Balbuena, J.A.; Aguilar, A.; Grau, E.; Borrell, A. Varamientos de cetáceos en las costas españolas del Mediterráneo durante el período 1982–1988. Misc. Zool. 1991, 15, 215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Bradai, M.N. Nouvelles mentions de Delphinidae. Rev. Inst. Nat. Agronom. Tunis. 1991, 6, 169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzo, F.; Cancelli, F.; Baccetti, N. Catalogo Della Collezione Teriologica (Museo zoologico, Accademia dei fisiocritici). Atti Accad. Fisiocrit. Siena 1995, 15, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, B. Yunuslar ve Balinalar (Dolphins and Whales); Anahtar Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolosi, P.; Roselli, A.; Cagnolaro, L. Studio Dello Scheletro Di Balaenoptera physalus (L) Del Museo Di Storia Naturale Di Livorno. Museol. Sci. XIII 1997, 3, 245–266. [Google Scholar]

- Gruppo Ricerca Cetacei; Gomerčić, H.; Huber, D.; Gomerčić, A.; Gomerčić, T. Geographical and Historical Distribution of Cetaceans in Croatian Part of the Adriatic Sea. Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer Méed. Ée 1998, 35, 440–441. [Google Scholar]

- Bradai, N.M.; Ghorbel, M. Les Cétacés Dans Les Eaux Tunisiennes: Nouvelles Mentions D’éspèces Rares En Méditerranée. In Proceedings of the Actes de la 8ème Conference Intérnationale RIMMO, Sophia Antipolis, France, 19–21 November 1999; pp. 51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Alís, S.; Rivilla, J.C.; Ruiz, G.; Sancho, J.R. Varamiento de Un Rorcual Común (Balaenoptera physalus) Vivo En La Playa de Matalascañas, Huelva. Galemys Boletín Inf. Soc. Española Conserv. Estud. Mamíferos 2000, 12, 54–56. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell, A.; Aguilar, A.; Forcada, J.; Fernández, M.; Aznar, F.J.; Raga, J.A. Varamiento de cetáceos en las costas españolas del Mediterráneo durante el período 1989–2000. Misc. Zool. 2000, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Capoulade, F. Whales and Ferries in the Ligurian Sanctuary: Captain’s Experience and Owner’s Actions. Eur. Cetacean Soc. Newsl. 2002, 40, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzis, A.; Alexiadou, P.; Politi, E.; Gannier, A.; Corsini-Foka, M. Cetacean Fauna of the Greek Seas: Unexpectedly High Species Diversity. Eur. Res. Cetaceans 2004, 15, 421–425. [Google Scholar]

- Lipej, L.; Dulčić, J.; Kryštufek, B. On the Occurrence of the Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) in the Northern Adriatic. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2004, 84, 861–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braschi, S.; Cagnolaro, L.; Nicolosi, P. Catalogo Dei Cetacei Attuali Del Museo Di Storia Naturale e Del Territorio Dell’Università Di Pisa, Alla Certosa Di Calci. Mem. Ser. B 2007, 114, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ciçek, E.; Oktener, A.; Capar, O.B. First Report of Pennella Balaenopterae Koren and Danielssen, 1877 (Copepoda: Pennelidae) from Turkey. Turk. Parazitol. Derg. 2007, 31, 239–241. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, V.; Giovannotti, M. Haplotype Characterization of a Stranded Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus, 1758) from Ancona (Adriatic Sea, Central Italy). Hystrix It. J. Mamm. 2009, 20, 83–85. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Ríos, A.; Rodero, B.; Carretero, S. Estudios Veterinarios, in: Boletín de Estudios Sobre Tetrápodos Marinos Del Norte de África (Memoria de Varamientos de Cetáceos y Tortugas Marinas Ceuta, Septiembre 2006–Septiembre 2008). In Septem Nostra-Ecologistas en Acción; del Mar, M., Ed.; Alidrisia Marina, Fundación Museo del Mar de Ceuta: Ceuta, Spain, 2009; pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- De la Fuente, J. Estudio de Las Patologías Y Causas de Muerte de Cetáceos Varados En El Litoral de La Provincia de Cádiz (2001–2004). Doctoral Thesis, Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelli, G.; Bedocchi, D.; Cancelli, F.; Mancusi, C.; Marsili, L.; Nuti, S.; Mazzariol, S.; Renieri, T.; Ventrella, S. Resoconto degli spiaggiamenti di cetacei in toscana: L’attività dell’osservatorio toscano dei cetacei e del progetto gionha dal 2008 al 2010/report of cetacean strandings events in tuscany: The activity of the tuscan observatory for cetacean and gionha project in the last years. Biol. Mar. Mediter. 2011, 18, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Karaa, S.; Bradai, M.N.; Jribi, I.; Hili, H.A.E.; Bouain, A. Status of Cetaceans in Tunisia through Analysis of Stranding Data from 1937 to 2009. Mammalia 2012, 76, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocaña, O.; Rosa, J.A.; Pérez-Rivera, J.M. Seguimiento de Los Varamientos de Cetáceos y Tortugas Marinas de La Región de Ceuta (2013–2014). Alidrisia 2015, 4, 6–20. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo, M.; Alcántara, E.; Taverna, A.; Paredes, R.; Garcia-Franquesa, E. Descripción osteológica del rorcual común (Balaenoptera physalus, Linnaeus, 1758) del Museo de Ciencias Naturales de Barcelona. Arx. Misc. Zool. 2014, 12, 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maio, N.; Petraccioli, A.; De Stasio, R.; Federico, A.; Pollaro, F. I reperti cetologici conservati presso enti scientifici e religiosi della Campania. Museol. Sci. Mem. 2014, 12, 346–354. [Google Scholar]

- Masski, H.; De Stéphanis, R. Cetaceans of the Moroccan Coast: Information from a Reconstructed Strandings Database. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2018, 98, 1029–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melero, M.; Crespo-Picazo, J.L.; Rubio-Guerri, C.; García-Párraga, D.; Sánchez-Vizcaíno, J.M. First Molecular Determination of Herpesvirus from Two Mysticete Species Stranded in the Mediterranean Sea. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milani, C.B.; Vella, A.; Vidoris, P.; Christidis, A.; Koutrakis, E.; Frantzis, A.; Miliou, A.; Kallianiotis, A. Cetacean Stranding and Diet Analyses in the North Aegean Sea (Greece). J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2018, 98, 1011–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmim, M. Les Mammifères Sauvages d’Algérie. Répartition et Biologie de La Conservation; Les Éditions Du Net: Saint-Ouen, France, 2019; ISBN 978-2312068961. [Google Scholar]

- Marcer, F.; Marchiori, E.; Centelleghe, C.; Ajzenberg, D.; Gustinelli, A.; Meroni, V.; Mazzariol, S. Parasitological and Pathological Findings in Fin Whales Balaenoptera physalus Stranded along Italian Coastlines. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2019, 133, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltier, H.; Beaufils, A.; Cesarini, C.; Dabin, W.; Dars, C.; Demaret, F.; Dhermain, F.; Doremus, G.; Labach, L.; Van Canneyt, O.; et al. Monitoring of Marine Mammal Strandings along French Coasts Reveals the Importance of Ship Strikes on Large Cetaceans: A Challenge for the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvertoret-Sanz, M.; López-Figueroa, C.; O’Byrne, A.; Canturri, A.; Martí-Garcia, B.; Pintado, E.; Pérez, L.; Ganges, L.; Cobos, A.; Abarca, M.L.; et al. Causes of Cetacean Stranding and Death on the Catalonian Coast (Western Mediterranean Sea), 2012–2019. Dis. Aquat. Organ. 2020, 142, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizgalla, J. Live Stranded Fin Whale Balaenoptera physalus in Libyan Waters Reported via Social Media Platform. J. Black Sea/Mediterr. Environ. 2020, 26, 329–335. [Google Scholar]

- Tonay, A.M.; Dede, A.; Gül, B.; Öztürk, A.A. First record of a fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) stranding on the northern Aegean Sea coast of Turkey. J. Black Sea/Medit. Environ. 2020, 26, 223–230. [Google Scholar]

- Farrag, M.; Ahmed, H.O.; Tamsouri, N.; TouTou, M.M. Re-Identification of the Bryde’s Whale (Balaenoptera Edeni) and the Gervais’ Beaked Whale (Mesoplodon Europaeus) on the Mediterranean Coast of Egypt “Updating, Strandings in Opposite to Climatic and Anthropogenic Impacts. Egypt. J. Aquatic Biol. Fish 2022, 26, 125–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioravanti, T.; Maio, N.; Latini, L.; Splendiani, A.; Guarino, F.M.; Mezzasalma, M.; Petraccioli, A.; Cozzi, B.; Mazzariol, S.; Centelleghe, C.; et al. Nothing Is as It Seems: Genetic Analyses on Stranded Fin Whales Unveil the Presence of a Fin-Blue Whale Hybrid in the Mediterranean Sea (Balaenopteridae). Eur. Zool. J. 2022, 89, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfrini, V.; Pierantonio, N.; Giuliani, A.; De Pascalis, F.; Maio, N.A. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Mortality along the Italian Coast between 1624 and 2021. Animals 2022, 12, 3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández, C.; Arbelo, M.; Fernández, A.; Díaz, J.; Bernaldo, Y.; De la Fuente, J.; Arregui, M.; Sierra, E. Ship strikes: Two cases of fin whales stranded on the South Atlantic Spanish coast. In Proceedings of the 34th Annual Conference of the European Cetacean Society, O´Grove, Spain, 18–20 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Oren, S.; Edery, N.; Yasur-Landau, D.; King, R.; Leszkowicz Mazuz, M. First Report of Pennella Balaenopterae Infestation in a Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) Carcass Washed Ashore on the Israeli Coastline. Isr. J. Vet. Med. 2023, 78, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Abd Rabou, A.F.N.; Elkahlout, K.E.; Elnabris, K.J.; Attallah, A.J.; Salah, J.Y.; Aboutair, M.A.; Thabit, W.M.; Serri, S.K.; Abu Hatab, H.G.; Awadalah, S.M.; et al. An Inventory of Some Relatively Large Marine Mammals, Reptiles, and Fishes Sighted, Caught, by-Caught, or Stranded in the Mediterranean Coast of the Gaza Strip-Palestine. Open J. Ecol. 2023, 13, 119–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diorio, V. Il cetaceo de S. Marinella. Atti Accad. Pontif. Nuovi Lincei 1866, 19, 189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Heldt, H. Incursions de baleinoptères sur les côtes tunisiennes. Ann. Biol. Cph. 1949, 6, 80. [Google Scholar]