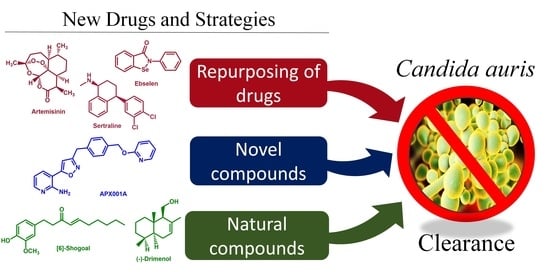

Promising Drug Candidates and New Strategies for Fighting against the Emerging Superbug Candida auris

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Candida auris Genomic Epidemiology and Virulence Factors

2.1. Global View

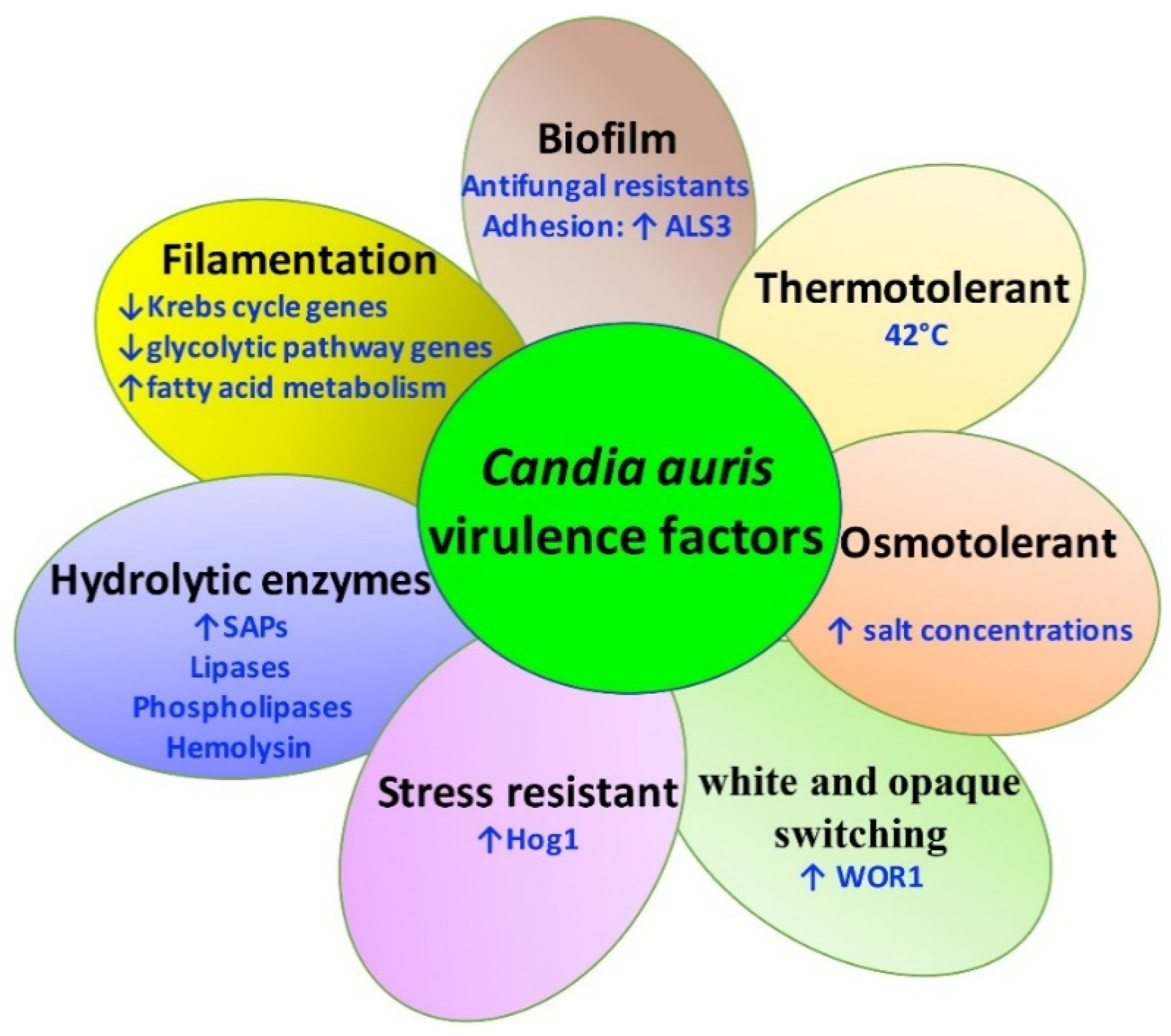

2.2. Virulence Factors of C. auris

3. Repurposing Drugs

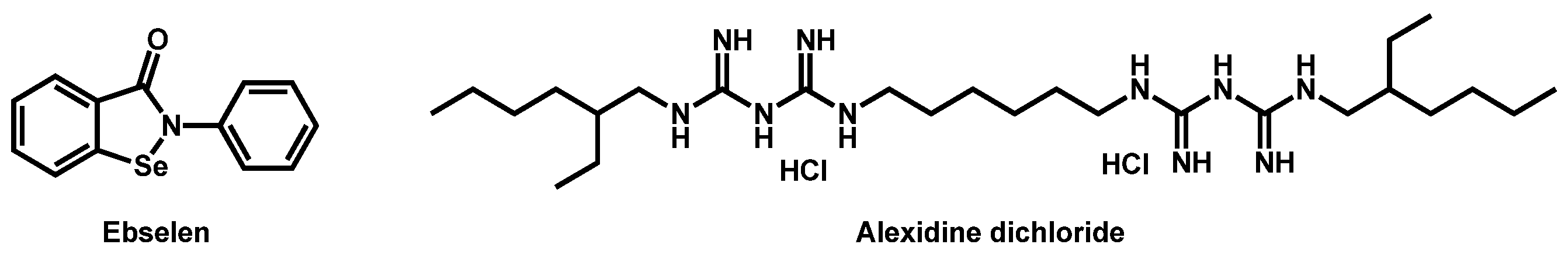

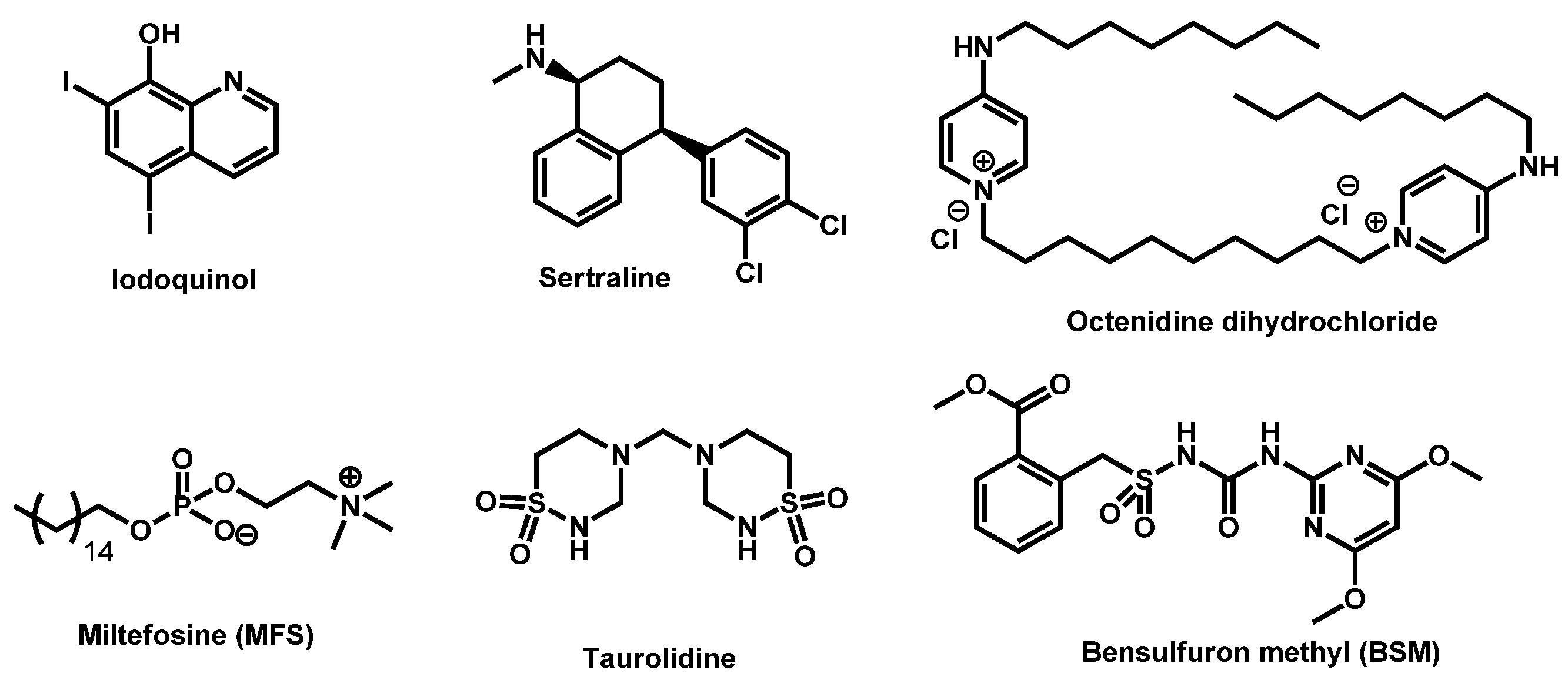

3.1. Drugs: In Vitro Screening

3.2. Drugs: In Vitro Screening and In Vivo Validation

3.3. Vaccines: In Vivo Evaluation

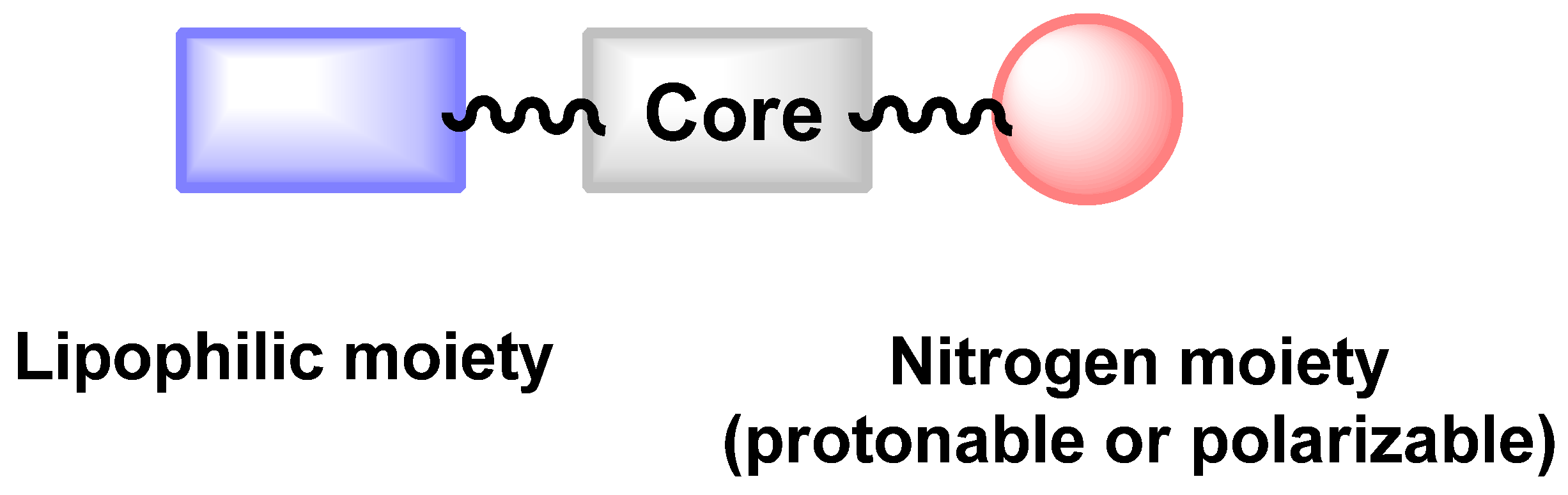

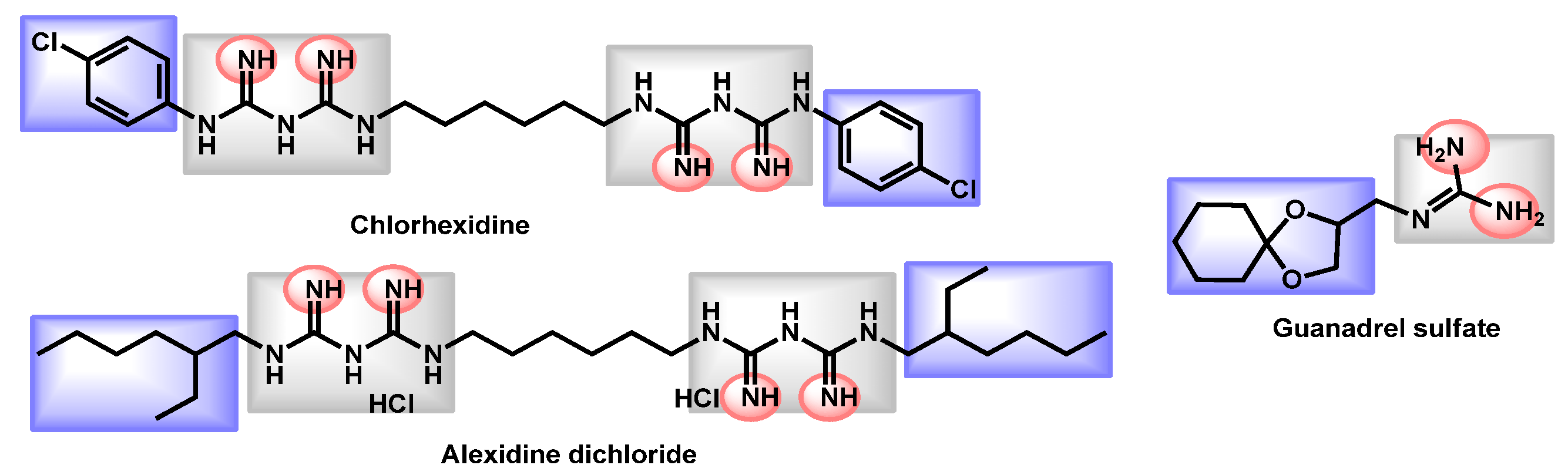

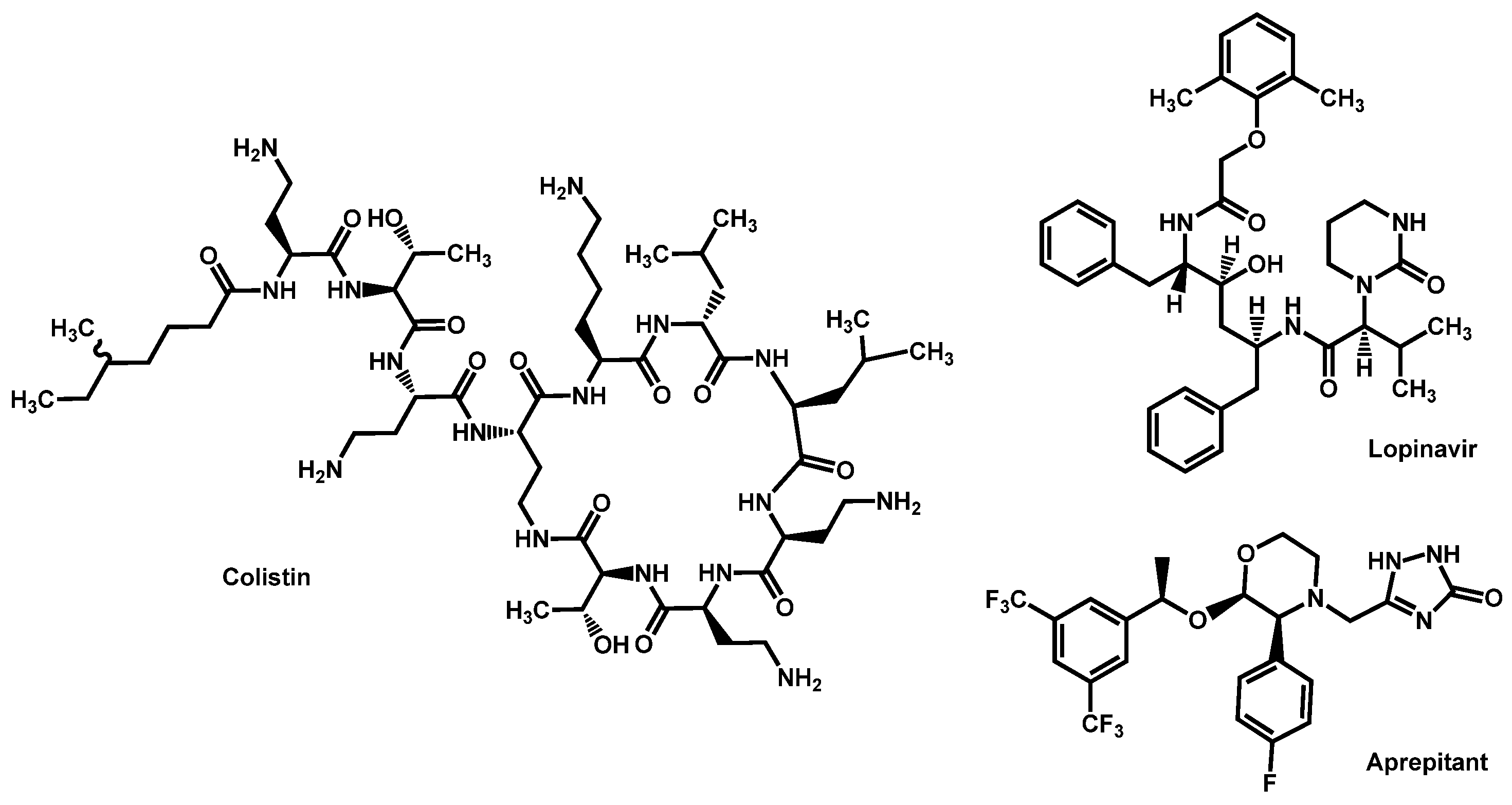

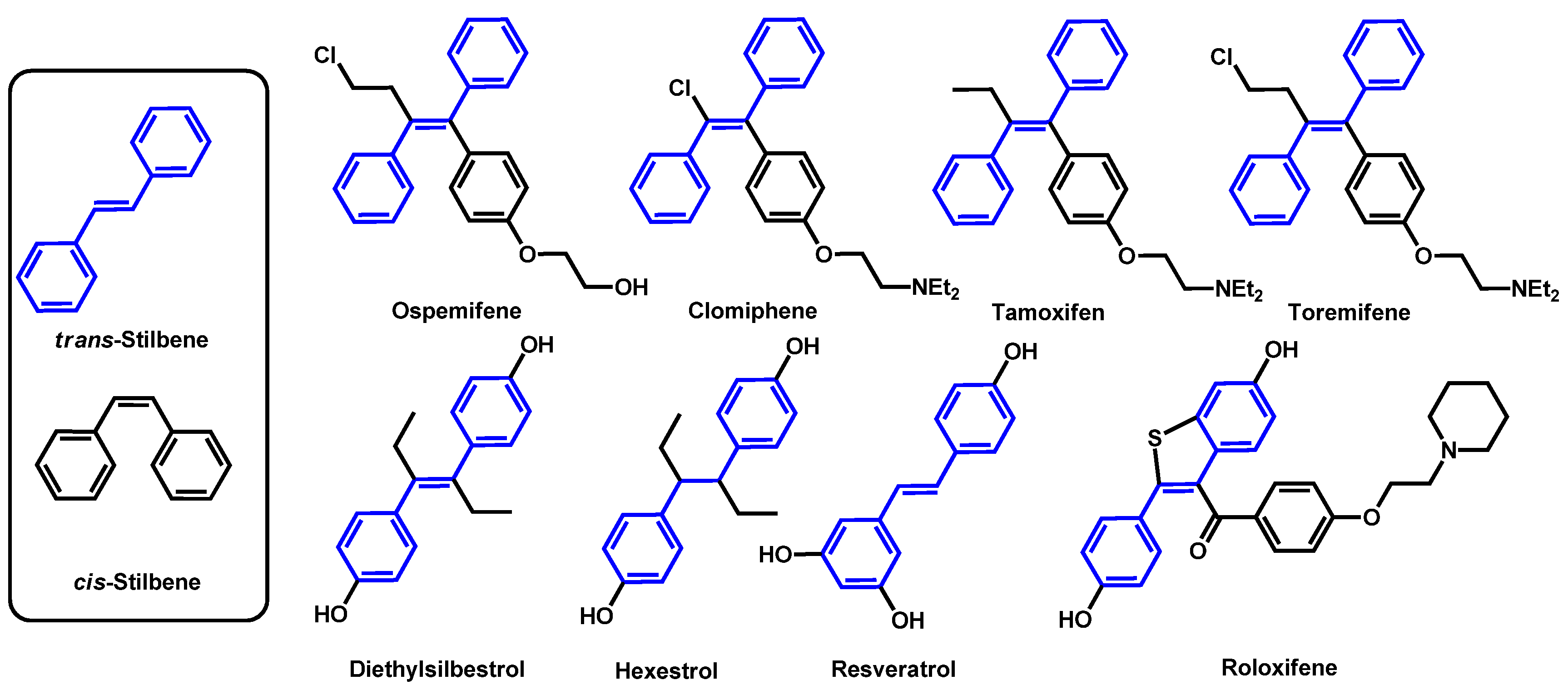

3.4. Critical Analysis of Repurposing Drugs from a Chemical/Physicochemical Point of View

4. Combination Drugs

4.1. Combination of Antifungal Drugs

4.2. Combinations of a Repositioning Drug with an Antifungal Drug

4.2.1. In Vitro Screening

4.2.2. In Vivo Confirmation

4.3. Combination of New Compounds and Old Drug: In Vitro Results

5. Novel Compounds

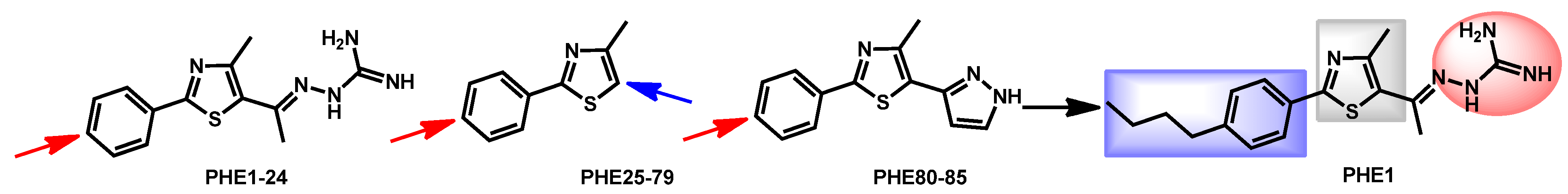

5.1. Small Molecules

5.1.1. In Vitro Evaluation

5.1.2. In Vitro Screening and In Vivo Validation

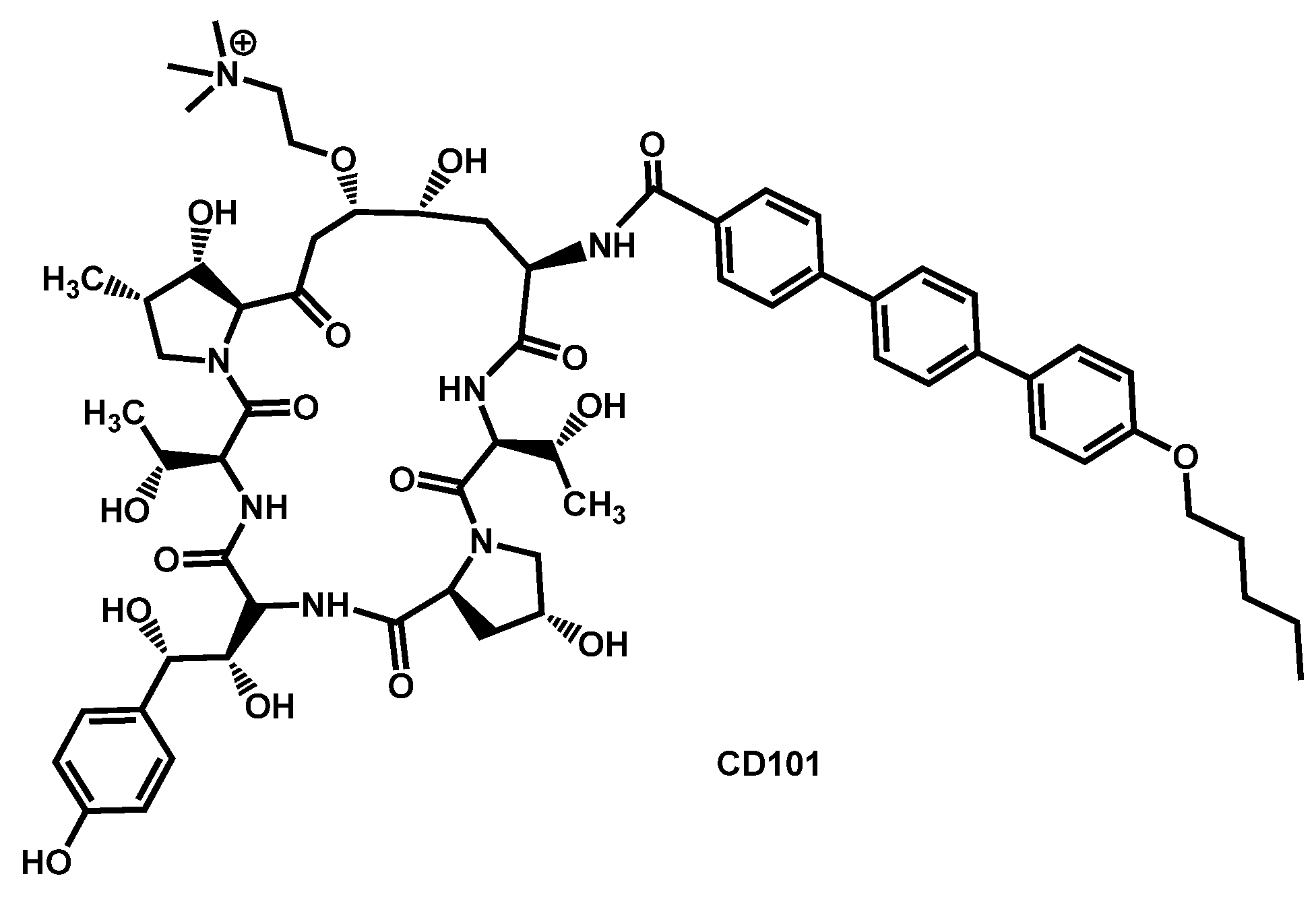

5.2. Echinocandins

5.3. Selvamycin Analogues

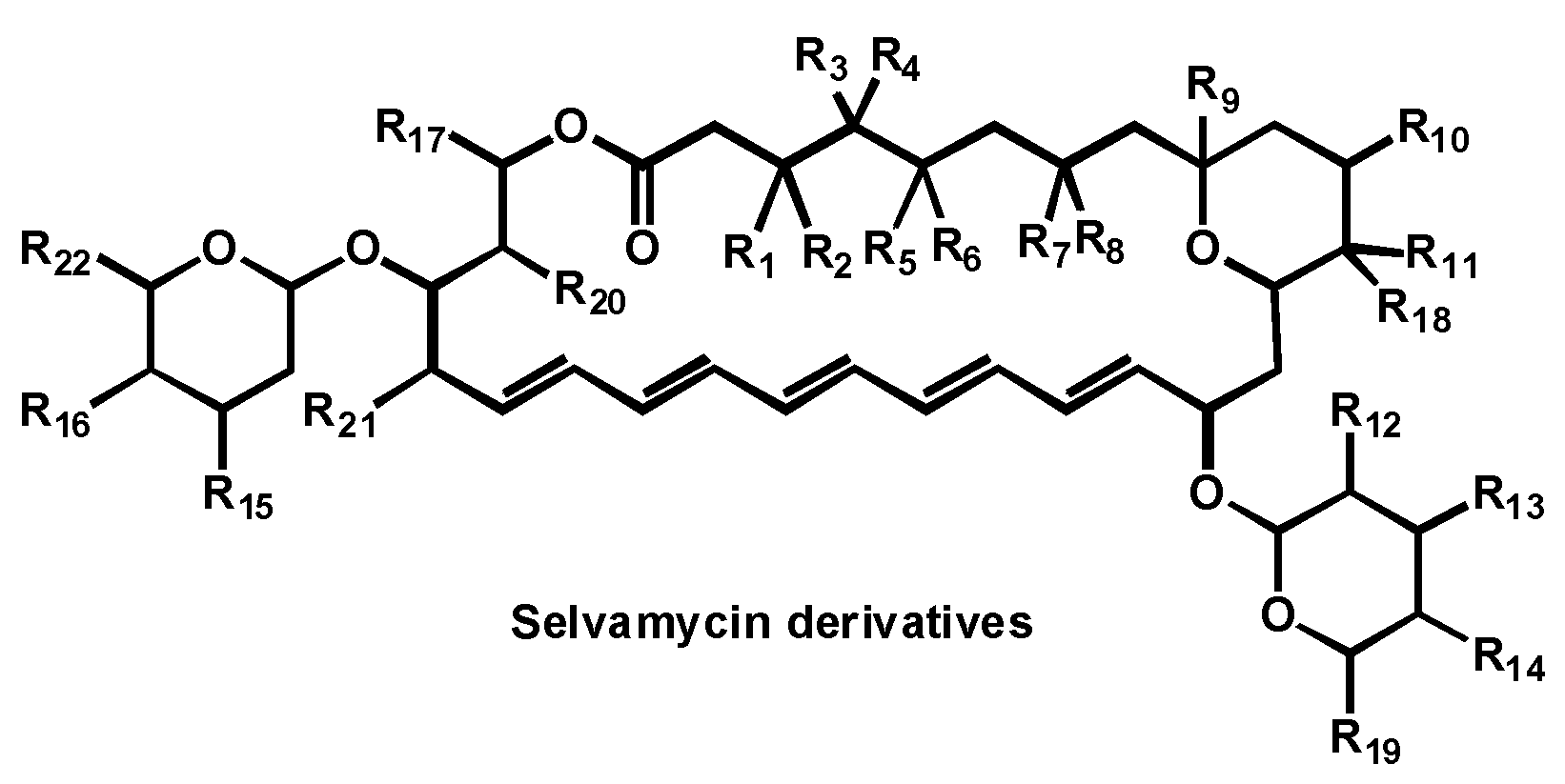

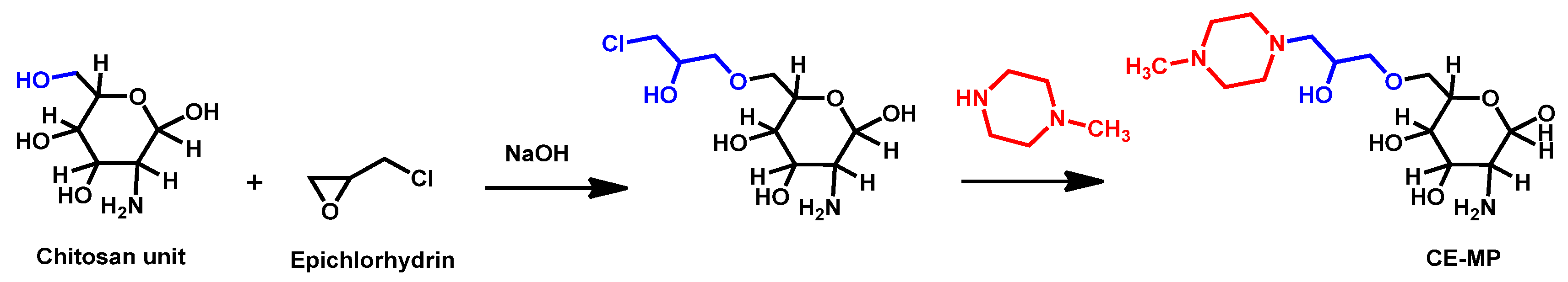

5.4. Polymers

5.5. Polyclonal Antibody

6. Traditional Medicines and Natural Compounds

6.1. Small Natural Compounds

6.2. Extracts of Natural Organisms

6.3. Peptides and Derivatives

6.4. Bioinspiration

6.5. Necrotrophic Mycoparasitism

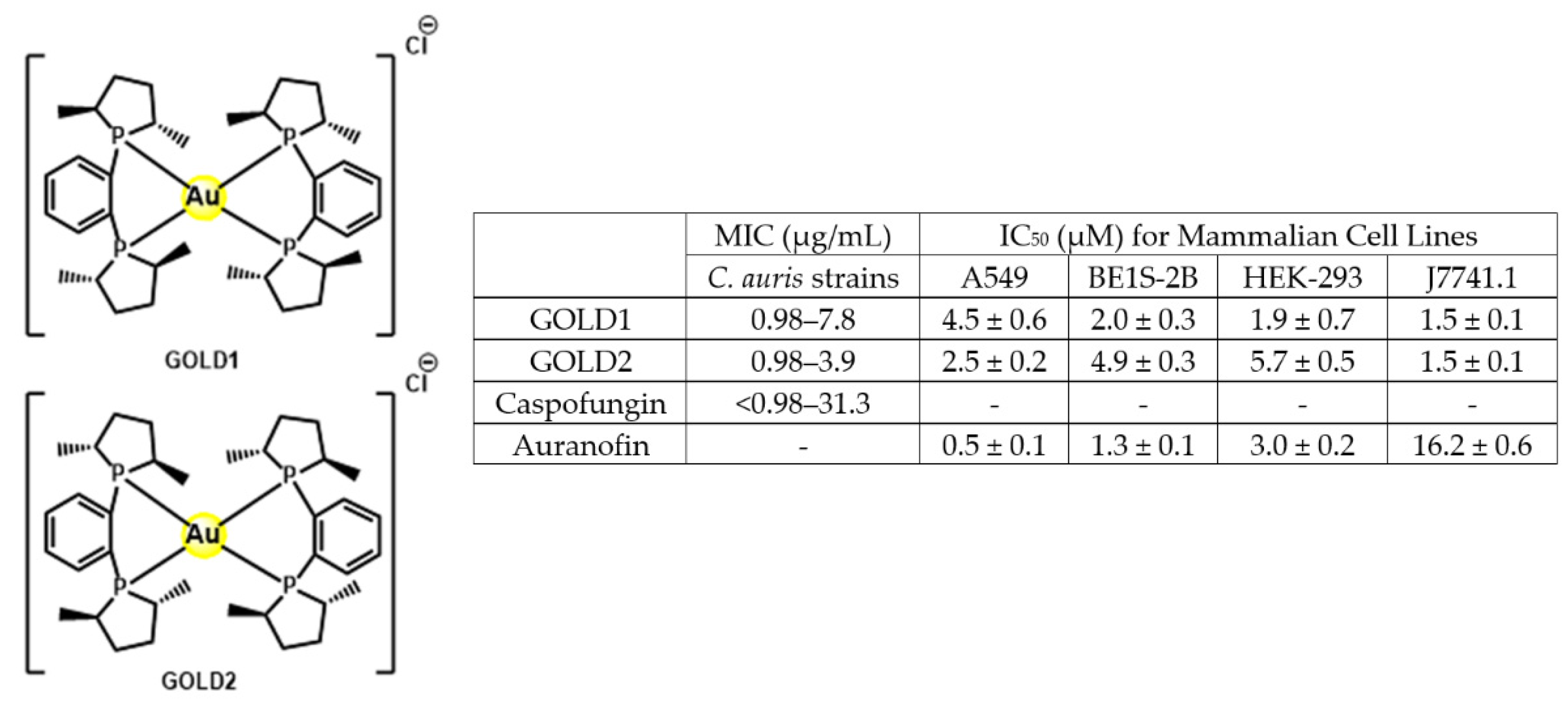

7. Metal, Metal Complexes and Metalloids

8. Others Approaches

8.1. Probiotics and Postbiotics

8.2. Nanoparticles and Coatings

8.3. Hydrogels

8.4. Irradiation

9. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satoh, K.; Makimura, K.; Hasumi, Y.; Nishiyama, Y.; Uchida, K.; Yamaguchi, H. Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009, 53, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Singh, S. Multidrug-resistant Candida auris: An epidemiological review. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2020, 18, 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, J.; Fisher, M.C. Global epidemiology of emerging Candida auris. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2019, 52, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz Gaitán, A.C.; Moret, A.; López Hontangas, J.L.; Molina, J.M.; Aleixandre López, A.I.; Hernández Cabezas, A.; Mollar Maseres, J.; Arcas, R.C.; Gómez Ruiz, M.D.; Chiveli, M.A.; et al. Nosocomial fungemia by Candida auris: First four reported cases in continental Europe. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2017, 34, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health England. Research and Analysis: Candida auris Identified in England. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/candida-auris-emergence-in-england/candida-auris-identified-in-england (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- ECDC. Candida in Healthcare Settings. 2016, p. 8. Available online: https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/Candida-in-healthcare-settings_19-Dec-2016.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Kim, M.N.; Shin, J.H.; Sung, H.; Lee, K.; Kim, E.-C.; Ryoo, N.; Lee, J.-S.; Jung, S.-I.; Park, K.H.; Kee, S.J.; et al. Candida haemulonii and closely related species at 5 university hospitals in Korea: Identification, antifungal susceptibility, and clinical features. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, e57–e61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.G.; Shin, J.H.; Uh, Y.; Kang, M.G.; Kim, S.H.; Park, K.H.; Jang, H.C. First three reported cases of nosocomial fungemia caused by Candida auris. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 3139–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, A.; Sharma, C.; Duggal, S.; Agarwal, K.; Prakash, A.; Singh, P.K.; Jain, S.; Kathuria, S.; Randhawa, H.S.; Hagen, F.; et al. New clonal strain of Candida auris, Delhi, India. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 1670–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Sood, P.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Chen, S.; Kaur, H.; Capoor, M.; Chhina, D.; Rao, R.; Eshwara, V.K.; Xess, I.; et al. Incidence, characteristics and outcome of ICU-acquired candidemia in India. Intensive Care Med. 2015, 41, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhary, A.; Anil Kumar, V.; Sharma, C.; Prakash, A.; Agarwal, K.; Babu, R.; Dinesh, K.R.; Karim, S.; Singh, S.K.; Hagen, F.; et al. Multidrug-resistant endemic clonal strain of Candida auris in India. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 33, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magobo, R.E.; Corcoran, C.; Seetharam, S.; Govender, N.P. Candida auris-associated candidemia, South Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1250–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emara, M.; Ahmad, S.; Khan, Z.; Joseph, L.; Al-Obaid, I.; Purohit, P.; Bafna, R. Candida auris candidemia in Kuwait, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1091–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arensman, K.; Miller, J.L.; Chiang, A.; Mai, N.; Levato, J.; LaChance, E.; Anderson, M.; Beganovic, M.; Dela Pena, J. Clinical Outcomes of Patients Treated for Candida auris Infections in a Multisite Health System, Illinois, USA. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y.; Bradley, N.; Brooks, S.; Burney, S.; Wassner, C. Management of Patients with Candida auris Fungemia at Community Hospital, Brooklyn, New York, USA, 2016-20181. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 601–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, N.A.; Gade, L.; Tsay, S.V.; Forsberg, K.; US Candida auris Investigation Team. Multiple introductions and subsequent transmission of multidrug-resistant Candida auris in the USA: A molecular Candida auris in contemporary mycology labs at epidemiological survey. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, B.; Melo, A.S.A.; Perozo-Mena, A.; Hernandez, M.; Francisco, E.C.; Hagen, F.; Meis, J.F.; Colombo, A.L. First report of Candida auris in America: Clinical and microbiological aspects of 18 episodes of candidemia. J Infect. 2016, 73, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taori, S.K.; Khonyongwa, K.; Hayden, I.; Dushyanthie, G.I.D.; Athukorala, A.D.; Letters, A.; Fife, A.; Desai, N.; Borman, A.M. Candida auris outbreak: Mortality, interventions and cost of sustaining control. J Infect. 2019, 79, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, C.J.; Nguyen, M.H. Emergence of Candida auris: An International Call to Arms. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, D.; Schwartz, B.S. Candida auris: An emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 63, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabino, R.; Verissimo, C.; Pereira, A.A.; Antunes, F. Candida auris, an agent of hospital-associated outbreaks: Which challenging issues do we need to have in mind? Microorganisms 2020, 8, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockhart, S.R.; Etienne, K.A.; Vallabhaneni, S.; Farooqi, J.; Chowdhary, A.; Govender, N.P.; Colombo, A.L.; Calvo, B.; Cuomo, C.A.; Desjardins, C.A.; et al. Simultaneous Emergence of Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris on 3 Continents Confirmed by Whole-Genome Sequencing and Epidemiological Analyses. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 64, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pristov, K.E.; Ghannoum, M.A. Resistance of Candida to azoles and echinocandins worldwide. Clin. Microbiol. Infection 2019, 25, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, J.F.; Gade, L.; Chow, N.A.; Loparev, V.N.; Juieng, P.; Berkow, E.L.; Farrer, R.A.; Litvintseva, A.P.; Cuomo, C.A. Genomic insights into multidrug-resistance, mating and virulence in Candida auris and related emerging species. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5346–5358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, N.A.; de Groot, T.; Badali, H.; Abastabar, M.; Chiller, T.M.; Meis, J.F. Potential Fifth Clade of Candida auris, Iran, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1780–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desoubeaux, G.; Bailly, E.; Guillaume, C.; De Kyvon, M.A.; Tellier, A.C.; Morange, V.; Bernard, L.; Salame, E.; Quentin, R.; Chandenier, J. Candida auris in contemporary mycology labs: A few practical tricks to identify it reliably according to one recent French experience. J. Mycol. Med. 2018, 28, 407–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J.; Turnidge, J.D.; Castanheira, M.; Jones, R.N. Twenty Years of the SENTRY Antifungal Surveillance Program: Results for Candida Species from 1997–2016. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6 (Suppl. S1), S79–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, B.R.; Chow, N.; Forsberg, K.; Litvintseva, A.P.; Lockhart, S.R.; Welsh, R.; Vallabhaneni, S.; Chiller, T. On the Origins of a Species: What Might Explain the Rise of Candida auris? J. Fungi 2019, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadevall, A.; Kontoyiannis, D.P.; Robert, V. On the Emergence of Candida auris: Climate Change, Azoles, Swamps, and Birds. mBio 2019, 10, e01397-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kean, R.; Sherry, L.; Townsend, E.; McKloud, E.; Short, B.; Akinbobola, A.; Mackay, W.G.; Williams, C.; Jones, B.L.; Ramage, G. Surface disinfection challenges for Candida auris: An in-vitro study. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 98, 433–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, H.; Bing, J.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, T.; Du, H.; Wang, H.; Huang, G. Filamentation in Candida auris, an emerging fungal pathogen of humans: Passage through the mammalian body induces a heritable phenotypic switch. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, M.L.; Sexton, D.J.; Welsh, R.M.; Litvintseva, A.P. Phenotypic switching in newly emerged multidrug-resistant patho, gen Candida auris. Med. Mycol. 2018, 57, 636–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvaal, C.; Lachke, S.A.; Srikantha, T.; Daniels, K.; McCoy, J.; Soll, D.R. Misexpression of the opaque-phase-specific gene PEP1 (SAP1) in the white phase of Candida albicans confers increased virulence in a mouse model of cutaneous infection. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 6652–6662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvaal, C.A.; Srikantha, T.; Soll, D.R. Misexpression of the white-phase-specific gene WH11 in the opaque phase of Candida albicans affects switching and virulence. Infect. Immun. 1997, 65, 4468–4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaffin, W.L. Candida albicans cell wall proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2008, 72, 495–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Bing, J.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Yue, H.; Tao, L.; Du, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; et al. The first isolate of Candida auris in China: Clinical and biological aspects. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2018, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, D.; Banerjee, T.; Pratap, C.B.; Tilak, R. Itraconazole-resistant Candida auris with phospholipase, proteinase and hemolysin activity from a case of vulvovaginitis. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries 2015, 9, 435–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghannoum, M.A. Potential role of phospholipases in virulence and fungal pathogenesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2000, 13, 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, E.; Hager, C.; Chandra, J.; Mukherjee, P.K.; Retuerto, M.; Salem, I.; Long, L.; Isham, N.; Kovanda, L.; Borroto-Esoda, K.-; et al. The Emerging Pathogen Candida auris: Growth Phenotype, Virulence Factors, Activity of Antifungals, and Effect of SCY-078, a Novel Glucan Synthesis Inhibitor, on Growth Morphology and Biofilm Formation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02396-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, A.P.; Green, B.J.; Beezhold, D.H. Fungal hemolysins. Med. Mycol. 2013, 51, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, A.V.; Prado, C.G.; Carvalho, R.R.; Dias, K.S.; Dias, A.L. Candida albicans and non-C. albicans Candida species: Comparison of biofilm production and metabolic activity in biofilms, and putative virulence properties of isolates from hospital environments and infections. Mycopathologia 2013, 175, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, A.M.; McNiff, M.M.; da Silva Dantas, A.; Gow, N.A.R.; Quinn, J. Hog1 Regulates Stress Tolerance and Virulence in the Emerging Fungal Pathogen Candida auris. mSphere 2018, 3, e00506-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Alampalli, S.V.; Nageshan, R.K.; Chettiar, S.T.; Joshi, S.; Tatu, U.S. Draft genome of a commonly misdiagnosed multidrug resistant pathogen Candida auris. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, C.; Kumar, N.; Pandey, R.; Meis, J.F.; Chowdhary, A. Whole genome sequencing of emerging multidrug resistant Candida auris isolates in India demonstrates low genetic variation. New Microbes New Infect. 2016, 13, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherry, L.; Ramage, G.; Kean, R.; Borman, A.; Johnson, E.M.; Richardson, M.D.; Rautemaa-Richardson, R. Biofilm-Forming Capability of Highly Virulent, Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Uppuluri, P.; Mamouei, Z.; Alqarihi, A.; Elhassan, H.; French, S.; Lockhart, S.R.; Chiller, T.; Edwards, J.E., Jr.; Ibrahim, A.S. The NDV-3A vaccine protects mice from multidrug resistant Candida auris infection. PLoS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pushpakom, S.; Iorio, F.; Eyers, P.; Escott, K.J.; Hopper, S.; Wells, A.; Doig, A.; Guilliams, T.; Latimer, J.; McNamee, C.; et al. Drug repurposing: Progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talevi, A.; Bellera, C.L. Challenges and opportunities with drug repurposing: Finding strategies to find alternative uses of therapeutics. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2020, 15, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Wormley, F.L., Jr.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, H.P.; Patterson, T.F. Screening a Repurposing Library for Inhibitors of Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris Identifies Ebselen as a Repositionable Candidate for Antifungal Drug Development. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01084-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

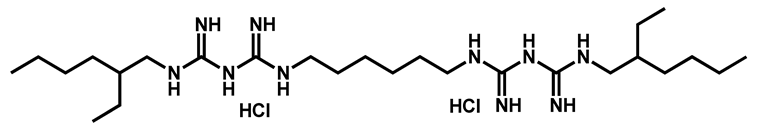

- Mamouei, Z.; Alqarihi, A.; Singh, S.; Xu, S.; Mansour, M.K.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Uppuluri, P. Alexidine Dihydrochloride Has Broad-Spectrum Activities against Diverse Fungal Pathogens. mSphere 2018, 3, e00539-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, H.C.; Monteiro, M.C.; Rossi, S.A.; Pemán, J.; Ruiz-Gaitán, A.; Mendes-Giannini, M.; Mellado, E.; Zaragoza, O. Identification of Off-Patent Compounds That Present Antifungal Activity Against the Emerging Fungal Pathogen Candida auris. Frontiers Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowri, M.; Jayashree, B.; Jeyakanthan, J.; Girija, E.K. Sertraline as a promising antifungal agent: Inhibition of growth and biofilm of Candida auris with special focus on the mechanism of action in vitro. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diluccio, R.; Reidenberg, B. Methods and pharmaceutical compositions for treating Candida auris in blood comprising administering taurolidine derivatives. PCT Int. Appl. (2019) WO 2019126695 A2 20190627. U.S. Patent 16/229,898, 27 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hübner, N.O.; Siebert, J.; Kramer, A. Octenidine Dihydrochloride, a Modern Antiseptic for Skin, Mucous Membranes and Wounds. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2010, 23, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponnachan, P.; Vinod, V.; Pullanhi, U.; Varma, P.; Singh, S.; Biswas, R.; Kumar, A. Antifungal activity of octenidine dihydrochloride and ultraviolet-C light against multidrug-resistant Candida auris. J Hosp Infect. 2019, 102, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew-Francis, K.A.; Tang, Y.; Lin, X.; Low, Y.S.; Wun, S.J.; Kuo, A.; Elias, S.; Lonhienne, T.; Condon, N.D.; Pimentel, B.; et al. Herbicides That Target Acetohydroxyacid Synthase Are Potent Inhibitors of the Growth of Drug-Resistant Candida auris. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020, 6, 2901–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, G.; Herrera, N.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Repositionable compounds with antifungal activity against multidrug resistant Candida auris identified in the medicines for malaria venture’s pathogen box. J. Fungi. 2019, 5, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Totten, M.; Memon, W.; Ying, C.; Zhang, S.X. In vitro antifungal susceptibility of the emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen Candida auris to miltefosine alone and in combination with amphotericin B. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, T.L.; de Freitas, A.L.D.; Ishida, K.; Rossato, L.; Colombo, A.L.; Meis, J.F.; Lopes, L.B. Miltefosine as an alternative strategy in the treatment of the emerging fungus Candida auris. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 106049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Uppuluri, P.; Alqarihi, A.; Elhassan, H.; French, S.; Lockhart, S.R.; Chiller, T.; Edwards, J.E., Jr.; Ibrahim, A.S. The NDV-3A vaccine protects mice from multidrug resistant Candida auris infection. bioRxiv Microbiol. 2018, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhim, H.; Chowdhary, A.; Prakash, A.; Vaezi, A.; Dannaoui, E.; Meis, J.F.; Badali, H. In Vitro Interactions of Echinocandins with Triazoles against Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01056-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, P.; Bidaud, A.L.; Dannaoui, E. In vitro synergy of isavuconazole in combination with colistin against Candida auris. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, B.; Chaturvedi, S.; Chaturvedi, V. In vitro evaluation of antifungal drug combinations against multidrug-resistant Candida auris isolates from New York outbreak. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bidaud, A.L.; Botterel, F.; Chowdhary, A.; Dannaoui, E. In vitro antifungal combination of flucytosine with amphotericin B, voriconazole, or micafungin against Candida auris shows no antagonism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, H.E.; Li, X.; Abutaleb, N.S.; Mohammad, H.; Seleem, M.N. Synergistic interactions of sulfamethoxazole and azole antifungal drugs against emerging multidrug-resistant Candida auris. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2018, 52, 754–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, H.E.; Salama, E.A.; Li, X.; Hazbun, T.R.; Mayhoub, A.S.; Seleem, M.N. Repurposing approach identifies pitavastatin as a potent azole chemosensitizing agent effective against azole-resistant Candida species. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Rezaie, S.; Daie Ghazvini, R.; Hashemi, S.J.; Badali, H.; Foroumadi, A.; Diba, K.; Chowdhary, A.; Meis, J.F.; Khodavaisy, S. In Vitro Interaction of Geldanamycin with Triazoles and Echinocandins against Common and Emerging Candida Species. Mycopathologia 2019, 184, 607–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidaud, A.L.; Djenontin, E.; Botterel, F.; Chowdhary, A.; Dannaoui, E. Colistin interacts synergistically with echinocandins against Candida auris. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

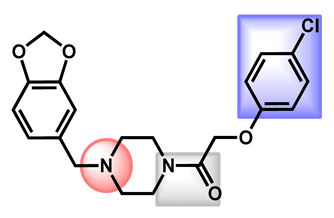

- Eldesouky, H.E.; Lanman, N.A.; Hazbun, T.R.; Seleem, M.N. Aprepitant, an antiemetic agent, interferes with metal ion homeostasis of Candida auris and displays potent synergistic interactions with azole drugs. Virulence 2020, 11, 1466–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, H.E.; Salama, E.A.; Lanman, N.A.; Hazbun, T.R.; Seleem, M.N. Potent Synergistic Interactions between Lopinavir and Azole Antifungal Drugs against Emerging Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 65, e00684-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revie, N.M.; Robbins, N.; Whitesell, L.; Frost, J.R.; Appavoo, S.D.; Yudin, A.K.; Cowen, L.E. Oxadiazole-containing macrocyclic peptides potentiate azole activity against pathogenic Candida species. mSphere 2020, 5, e00256-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, K.R.; Camara, K.; Daniel-Ivad, M.; Trilles, R.; Pimentel-Elardo, S.M.; Fossen, J.L.; Marchillo, K.; Liu, Z.; Singh, S.; Muñoz, J.F.; et al. An oxindole efflux inhibitor potentiates azoles and impairs virulence in the fungal pathogen Candida auris. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldesouky, H.E.; Salama, E.A.; Hazbun, T.R.; Mayhoub, A.S.; Seleem, M.N. Ospemifene displays broad-spectrum synergistic interactions with itraconazole through potent interference with fungal efflux activities. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

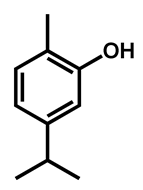

- Shaban, S.; Patel, M.; Ahmad, A. Improved efficacy of antifungal drugs in combination with monoterpene phenols against Candida auris. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

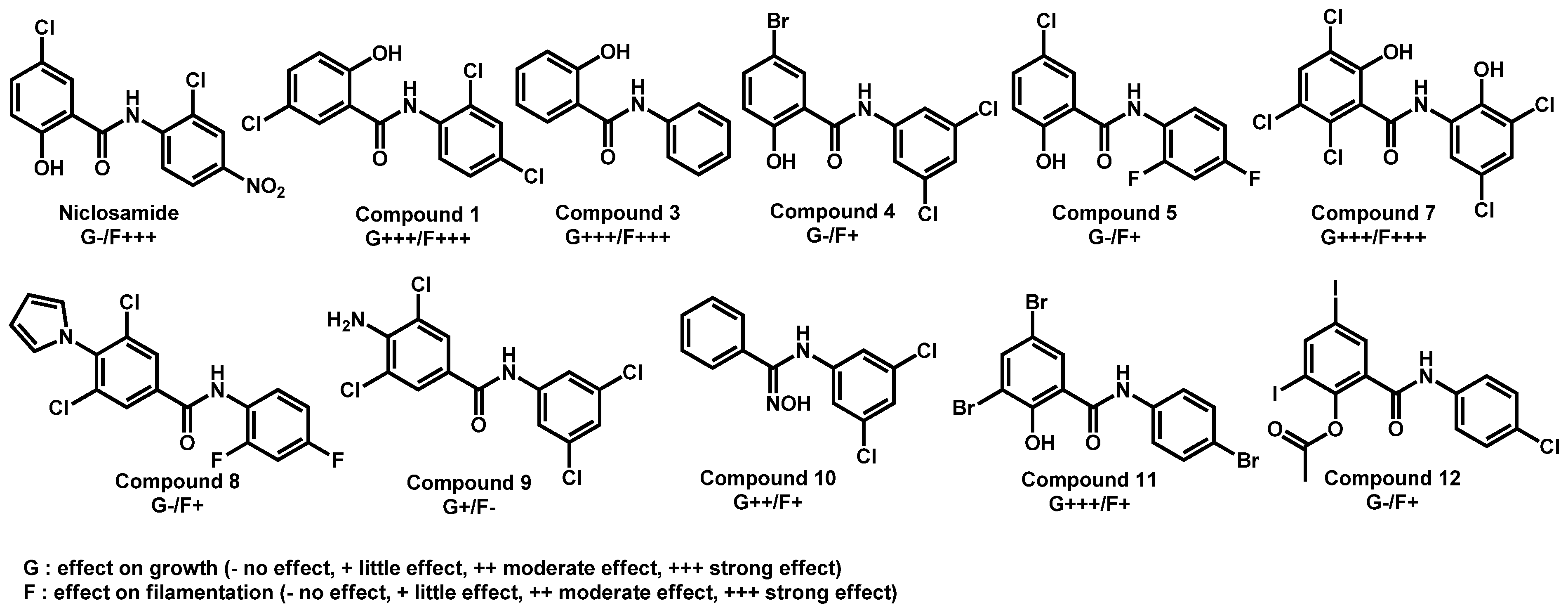

- Garcia, C.; Burgain, A.; Chaillot, J.; Pic, É.; Khemiri, I.; Sellam, A. A phenotypic small-molecule screen identifies halogenated salicylanilides as inhibitors of fungal morphogenesis biofilm formation and host cell invasion. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

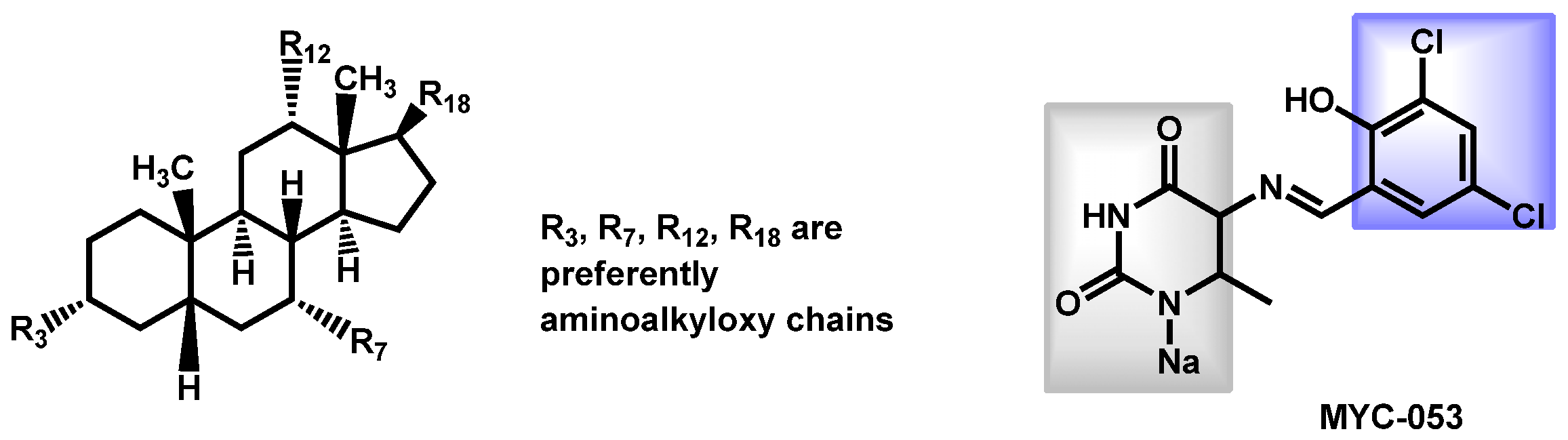

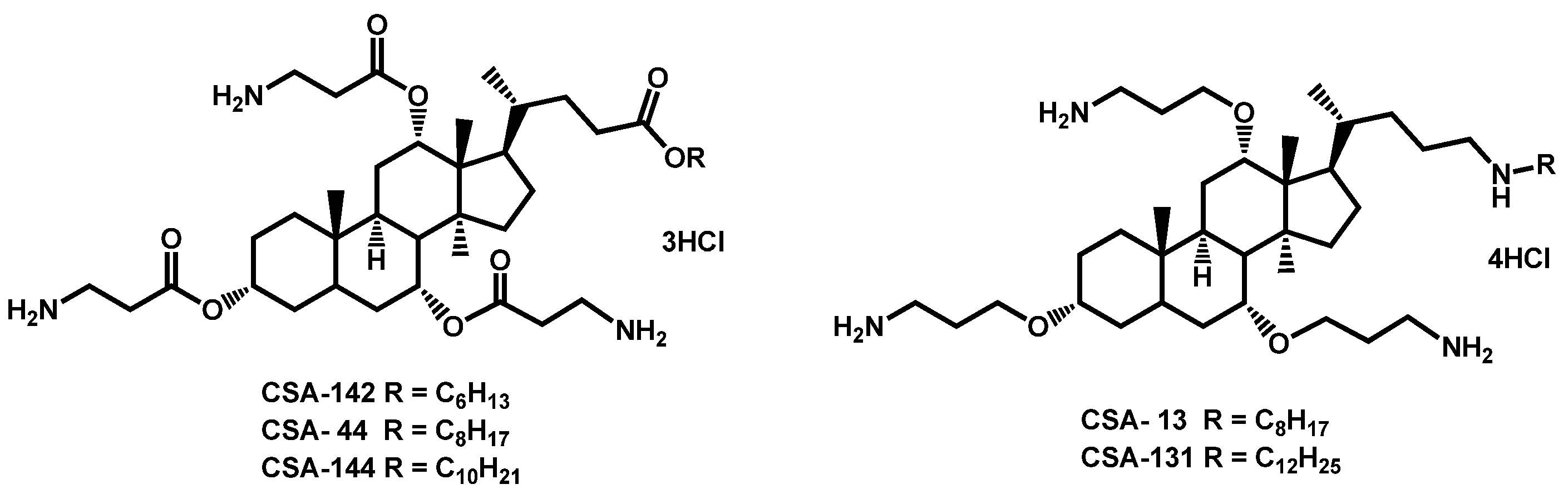

- Genberg, C.; Beus, C.S.; Savage, P.B. Methods for treating fungal infections using a cationic steroid antimicrobial. PCT Int. Appl. (2018) WO 2018204506 A1 20181108, 8 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tetz, G.; Collins, M.; Vikina, D.; Tetz, V. In Vitro Activity of a Novel Antifungal Compound MYC-053 against Clinically Significant Antifungal-Resistant Strains of Candida glabrata Candida auris Cryptococcus neoformans and Pneumocystis spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01975-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetz, G.; Collins, M.; Vikina, D.; Tetz, V. In vitro activity of a novel antifungal compound MYC-053 against clinically significant antifungal-resistant strains of Candida glabrata Candida auris Cryptococcus neoformans and Pneumocystis spp. bioRxiv Microbiol. 2018, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

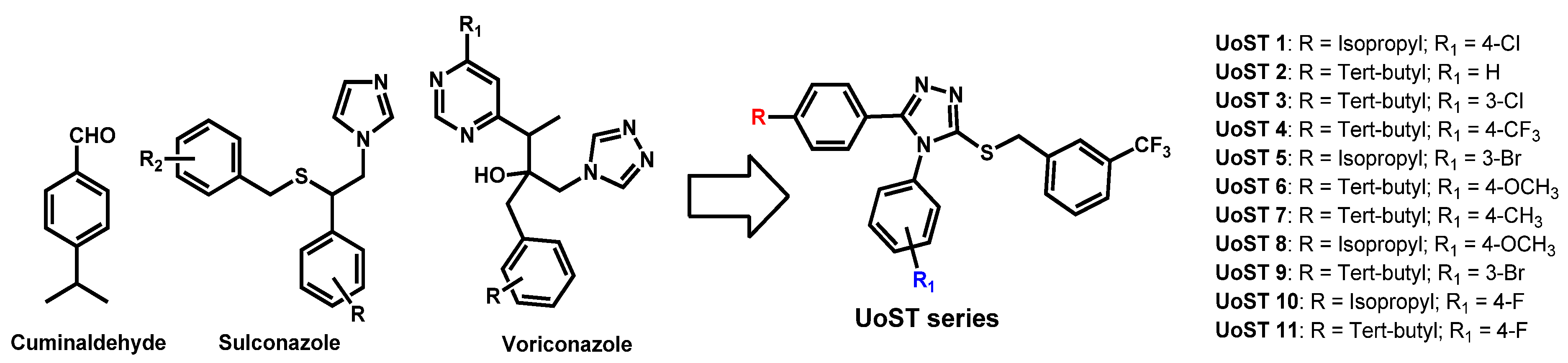

- Hamdy, R.; Fayed, B.; Hamoda, A.M.; Rawas-Qalaji, M.; Haider, M.; Soliman, S.S.M. Essential Oil-Based Design and Development of Novel Anti-Candida Azoles Formulation. Molecules 2020, 25, 1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, M.C.; Beattie, S.; Alden, K.M.; Krysan, D.J. Derivatives of the antimalarial drug mefloquine are broad spectrum antifungal molecules with activity against drug-resistant clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02331-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

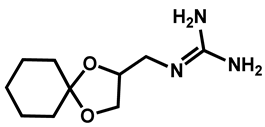

- Orofino, F.; Truglio, G.I.; Fiorucci, D.; D’Agostino, I.; Borgini, M.; Poggialini, F.; Zamperini, C.; Dreassi, E.; Maccari, L.; Torelli, R.; et al. In vitro characterization ADME analysis and histological and toxicological evaluation of BM1 a macrocyclic amidinourea active against azole-resistant Candida strains. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2020, 55, 105865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

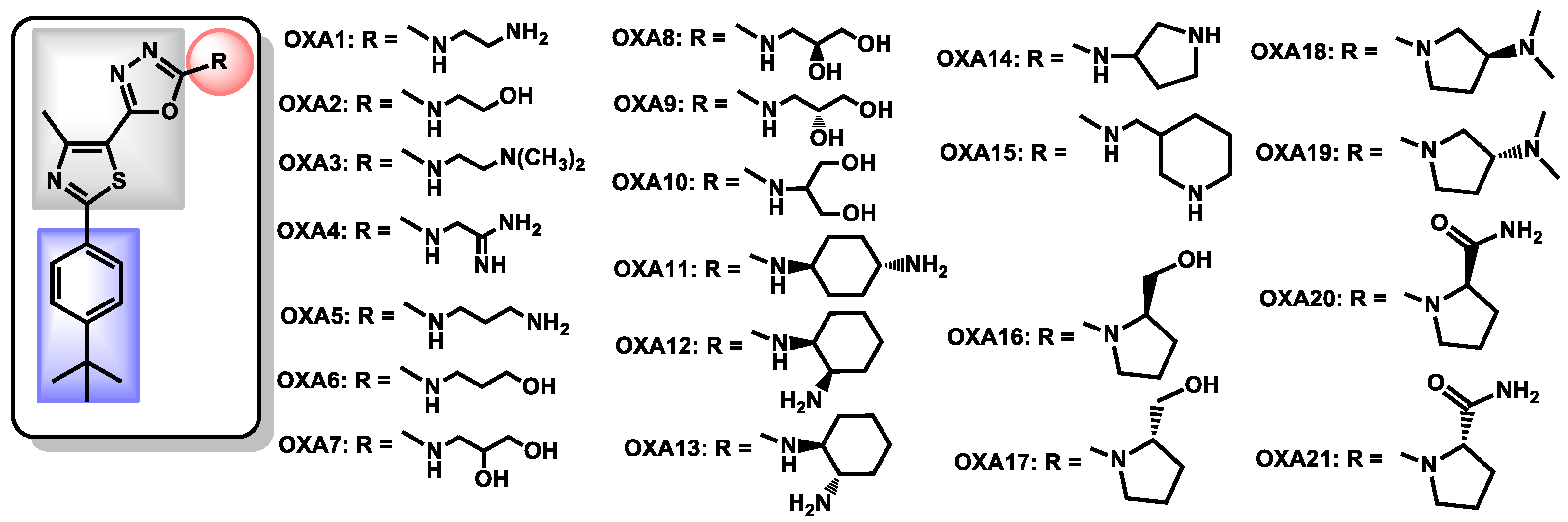

- Hagras, M.; Salama, E.A.; Sayed, A.M.; Abutaleb, N.S.; Kotb, A.; Seleem, M.N.; Mayhoub, A.S. Oxadiazolylthiazoles as novel and selective antifungal agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 189, 112046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Trawneh, S.A.; Al-Dawdieh, S.A.; Abutaleb, N.S.; Tarawneh, A.H.; Salama, E.A.; El-Abadelah, M.M.; Seleem, M.N. Synthesis of new pyrazolo[5-1-c][1-2-4]triazines with antifungal and antibiofilm activities. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

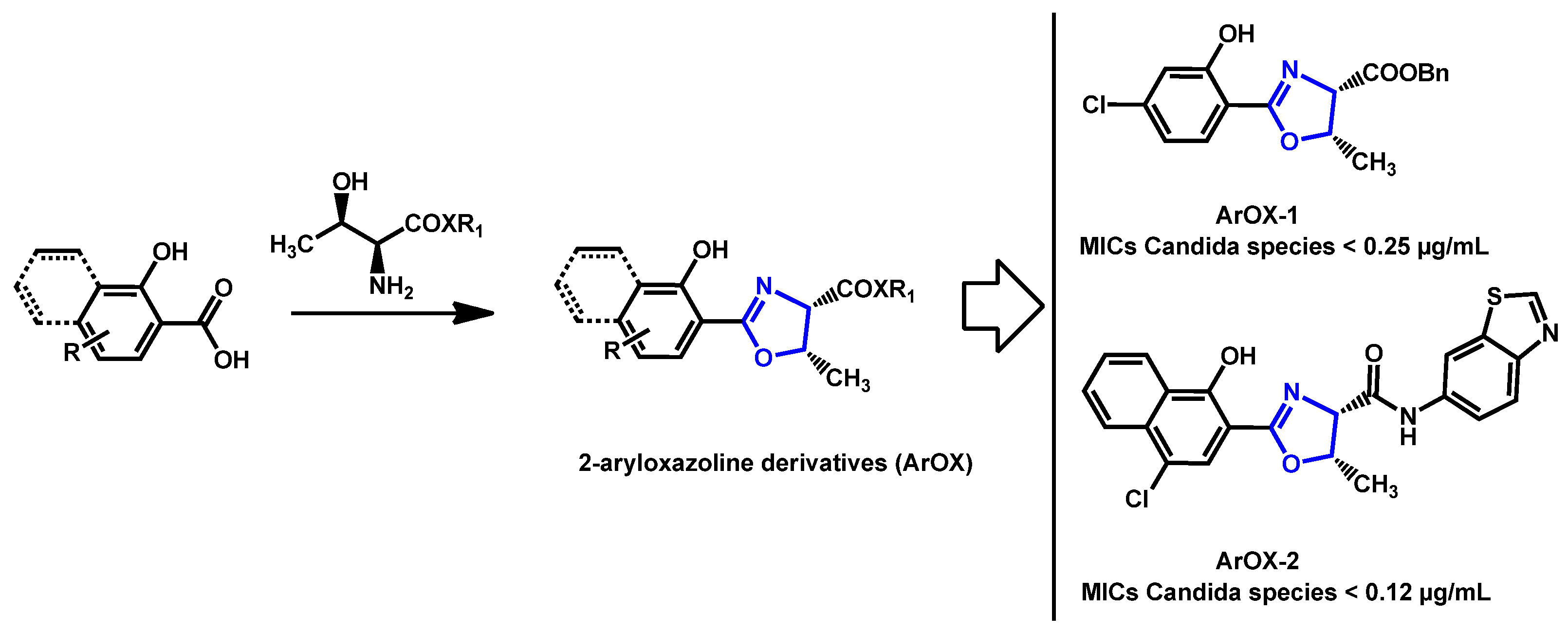

- Argomedo, L.; Barroso, V.M.; Barreiro, C.S.; Darbem, M.P.; Ishida, K.; Stefani, H.A. Novel 2-Aryloxazoline Compounds Exhibit an Inhibitory Effect on Candida spp. Including Antifungal-Resistant Isolates. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2470–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

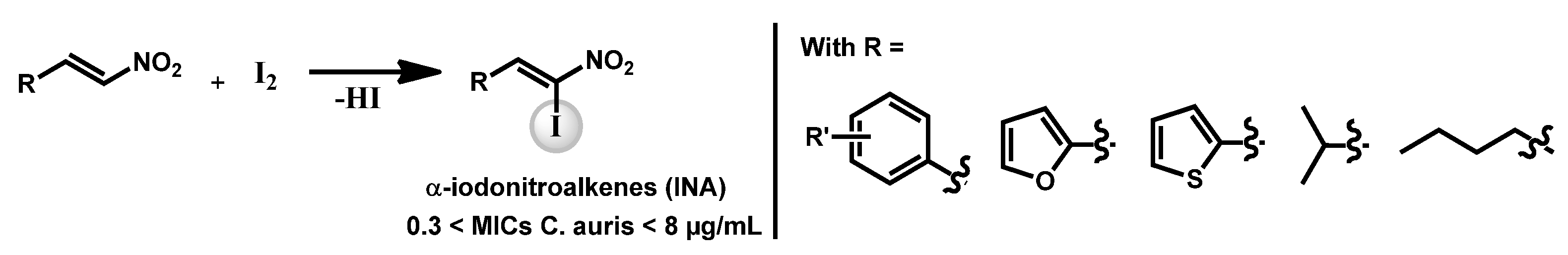

- Pamarthi, R.; Kumar, R.; Sankara, C.S.; Lowe, G.J.; Zuegg, J.; Singh, S.K.; Ganesh, M. α-Iodonitroalkenes as Potential Antifungal and Antitubercular Agents. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 12272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

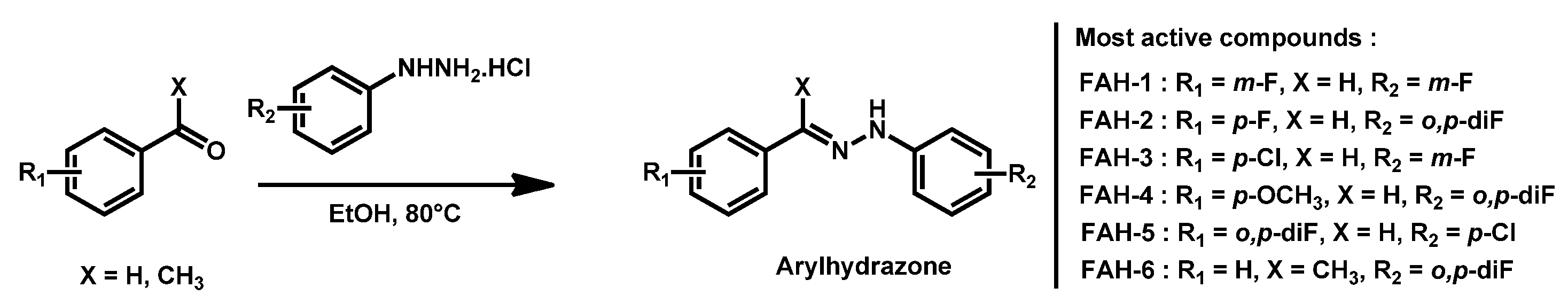

- Thamban Chandrika, N.; Dennis, E.K.; Brubaker, K.R.; Kwiatkowski, S.; Watt, D.S.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Agents: Fluorinated Aryl- and Heteroaryl-Substituted Hydrazones. ChemMedChem 2021, 16, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsuyama, J.; Nomura, N.; Hashimoto, K.; Yamada, E.; Nishikawa, H.; Kaeriyama, M.; Kimura, A.; Todo, Y.; Narita, H. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of T-2307, a novel arylamidine. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 1318–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Yamada, E.; Shibata, T.; Uchihashi, S.; Fan, H.; Hayakawa, H.; Nomura, N.; Mitsuyama, J. Uptake of T-2307, a novel arylamidine, in Candida albicans. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2010, 65, 1681–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Fothergill, A.W.; McCarthy, D.I.; Najvar, L.K.; Bocanegra, R.; Olivo, M.; Kirkpatrick, W.R.; Patterson, T.F.; Fukuda, Y.; Mitsuyama, J. The novel arylamidine T-2307 maintains in vitro and in vivo activity against echinocandin-resistant Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 1341–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Fothergill, A.W.; McCarthy, D.I.; Najvar, L.K.; Bocanegra, R.; Olivo, M.; Kirkpatrick, W.R.; Patterson, T.F.; Fukuda, Y.; Mitsuyama, J. The novel arylamidine T-2307 demonstrates in vitro and in vivo activity against echinocandin-resistant Candida glabrata. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 692–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Sakagami, T.; Yamada, E.; Fukuda, Y.; Hayakawa, H.; Nomura, N.; Mitsuyama, J.; Miyazaki, T.; Mukae, H.; Kohno, S. T-2307, a novel arylamidine, is transported into Candida albicans by a high-affinity spermine and spermidine carrier regulated by Agp2. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, T.; Takahashi, T.; Yamada, E.; Kimura, A.; Nishikawa, H.; Hayakawa, H.; Nomura, N.; Mitsuyama, J. T-2307 causes collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential in yeast. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 5892–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Najvar, L.K.; Jaramillo, R.; Olivo, M.; Patterson, H.; Connell, A.; Fukuda, Y.; Mitsuyama, J.; Catano, G.; Patterson, T.F. The novel arylamidine T-2307 demonstrates in vitro and in vivo activity against Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02198-19/1–e02198-19/5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkow, E.L.; Angulo, D.; Lockhart, S.R. In Vitro Activity of a Novel Glucan Synthase Inhibitor, SCY-078, against Clinical Isolates of Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00435-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.W.; Walsh, T.J. Drug development challenges and strategies to address emerging and resistant fungal pathogens. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2017, 15, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angulo Gonzalez, D.A.; Barat, S.A. Antifungal agents, like ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) for Candida auris decolonization. PCT Int. Appl. (2020) WO 2020232037 A1 20201119, 19 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Jørgensen, K.M.; Hare, R.K.; Chowdhary, A. In Vitro Activity of Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) against Candida auris Isolates as Determined by EUCAST Methodology and Comparison with Activity against C. albicans and C. glabrata and with the Activities of Six Comparator Agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02136-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.C.; Barat, S.A.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Angulo, D.; Chaturvedi, S.; Chaturvedi, V. Pan-resistant Candida auris isolates from the outbreak in New York are susceptible to ibrexafungerp (a glucan synthase inhibitor). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannoum, M.; Isham, N.; Angulo, D.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Long, L. Efficacy of Ibrexafungerp (SCY-078) against Candida auris in an In Vivo Guinea Pig Cutaneous Infection Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00854-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannoum, M.; Arendrup, M.C.; Chaturvedi, V.P.; Lockhart, S.R.; McCormick, T.S.; Chaturvedi, S.; Berkow, E.L.; Juneja, D.; Tarai, B.; Azie, N.; et al. Ibrexafungerp: A Novel Oral Triterpenoid Antifungal in Development for the Treatment of Candida auris Infections. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, S.; Long, L.; Sherif, R.; McCormick, T.S.; Borroto-Esoda, K.; Barat, S.; Ghannoum, M.A. A second generation fungerp analog SCY-247, shows potent in vitro activity against Candida auris and other clinically relevant fungal isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkow, E.L.; Lockhart, S.R. Activity of novel antifungal compound APX001A against a large collection of Candida auris. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 3060–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, C.L.; Larkin, E.L.; Long, L.; Abidi, F.Z.; Shaw, K.J.; Ghannoum, M.A. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of the Antifungal Activity of APX001A/APX001 against Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02319-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Chowdhary, A.; Astvad, K.M.T.; Joergensen, K.M. APX001A in vitro activity against contemporary blood isolates and Candida auris determined by the EUCAST reference method. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01225-18/1–e01225-18/9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Lee, M.H.; Paderu, P.; Lee, A.; Jimenez-Ortigosa, C.; Park, S.; Mansbach, R.S.; Shaw, K.J.; Perlin, D.S. Significantly Improved Pharmacokinetics Enhances In Vivo Efficacy of APX001 against Echinocandin- and Multidrug-Resistant Candida Isolates in a Mouse Model of Invasive Candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00425-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Lepak, A.J.; Andes, D.R.; VanScoy, B.; Bader, J.C.; Ambrose, P.G.; Marchillo, K.; Vanhecker, J.; Andes, D.R. In Vivo Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of APX001 against Candida spp. in a Neutropenic Disseminated Candidiasis Mouse Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02542-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Najvar, L.K.; Shaw, K.J.; Jaramillo, R.; Patterson, H.; Olivo, M.; Catano, G.; Patterson, T.F. Efficacy of delayed therapy with fosmanogepix (APX001) in a murine model of Candida auris invasive candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01120-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Chowdhary, A.; Jørgensen, K.M.; Meletiadis, J. Manogepix (APX001A) In Vitro Activity against Candida auris: Head-to-Head Comparison of EUCAST and CLSI MICs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00656-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Kilburn, S.; Kapoor, M.; Chaturvedi, S.; Shaw, K.J.; Chaturvedi, V. In Vitro Activity of Manogepix against Multidrug-Resistant and Panresistant Candida auris from the New York Outbreak. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01124-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

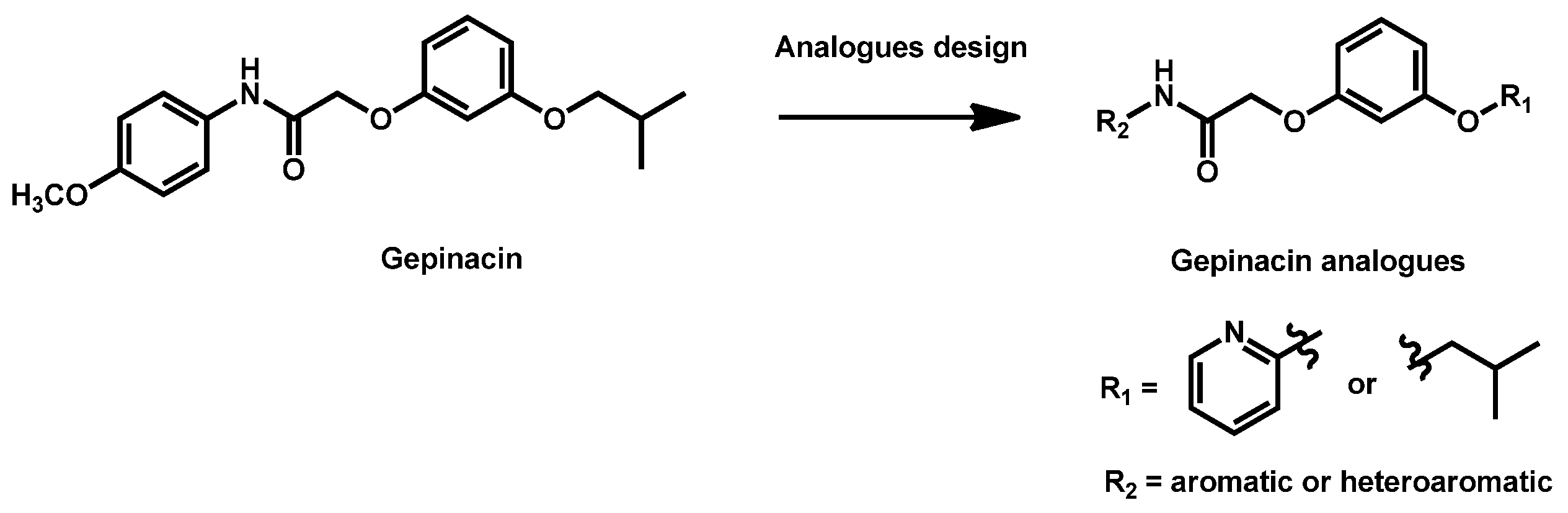

- Liston, S.D.; Whitesell, L.; McLellan, C.A.; Mazitschek, R.; Petraitis, V.; Petraitiene, R.; Kavaliauskas, P.; Walsh, T.J.; Cowen, L.E. Antifungal Activity of Gepinacin Scaffold Glycosylphosphatidylinositol Anchor Biosynthesis Inhibitors with Improved Metabolic Stability. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00899-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, H.; Eldesouky, H.E.; Hazbun, T.; Mayhoub, A.S.; Seleem, M.N. Identification of a Phenylthiazole Small Molecule with Dual Antifungal and Antibiofilm Activity Against Candida albicans and Candida auris. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Shawn, R.L.; Najvar, L.K.; Berkow, E.L.; Jaramillo, R.; Olivo, M.; Garvey, E.P.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Catano, G.; et al. The Fungal Cyp51-Specific Inhibitor VT-1598 Demonstrates In Vitro and In Vivo Activity against Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02233-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Break, T.J.; Desai, J.V.; Healey, K.R.; Natarajan, M.; Ferre, E.M.N.; Henderson, C.; Zelazny, A.; Siebenlist, U.; Yates, C.M.; Cohen, O.J.; et al. VT-1598 inhibits the in vitro growth of mucosal Candida strains and protects against fluconazole-susceptible and -resistant oral candidiasis in IL-17 signalling-deficient mice. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2089–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, H.P.; Tran, B.H.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Garvey, E.P. Fungal-specific Cyp51 inhibitor VT-1598 demonstrates in vitro activity against Candida and Cryptococcus species endemic fungi including Coccidioides species Aspergillus species and Rhizopus arrhizus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garvey, E.P.; Sharp, A.D.; Warn, P.A.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J. The novel fungal CYP51 inhibitor VT-1598 is efficacious alone and in combination with liposomal amphotericin B in a murine model of cryptococcal meningitis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2815–2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Shubitz, L.F.; Najvar, L.K.; Jaramillo, R.; Olivo, M.; Catano, G.; Trinh, H.T.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Garvey, E.P.; et al. The novel fungal Cyp51 inhibitor VT-1598 is efficacious in experimental models of central nervous system coccidioidomycosis caused by Coccidioides posadasii and Coccidioides immitis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02258-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudramurthy, S.M.; Colley, T.; Abdolrasouli, A.; Ashman, J.; Dhaliwal, M.; Kaur, H.; Armstrong-James, D.; Strong, P.; Rapeport, G.; Schelenz, S.; et al. In vitro antifungal activity of a novel topical triazole PC945 against emerging yeast Candida auris. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 2943–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartizal, K.; Daruwala, P.; Locke, J.B.; Ong, V.; Sandison, T.; Thye, D. Dosing regimens of CD101 acetate for the treatment of fungal infections. PCT Int. Appl. (2017) WO 2017161016 A1 20170921, 21 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bartizal, K.; Daruwala, P.; Ong, V. Methods for treating fungal infections by administering to the subject an antifungal compound CD101. PCT Int. Appl. (2018) WO 2018191692 A1 20181018, 18 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berkow, E.L.; Lockhart, S.R. Activity of CD101 a long-acting echinocandin against clinical isolates of Candida auris. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 90, 196–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hager, C.L.; Larkin, E.L.; Long, L.A.; Ghannoum, M.A. Evaluation of the efficacy of rezafungin a novel echinocandin in the treatment of disseminated Candida auris infection using an immunocompromised mouse model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2085–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepak, A.J.; Zhao, M.; Andes, D.R. Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of Rezafungin (CD101) against Candida auris in the Neutropenic Mouse Invasive Candidiasis Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01572-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tóth, Z.; Forgács, L.; Locke, J.B.; Kardos, G.; Nagy, F.; Kovács, R.; Szekely, A.; Borman, A.M.; Majoros, L. In vitro activity of rezafungin against common and rare Candida species and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 3505–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helleberg, M.; Jørgensen, K.M.; Krøger Hare, R.; Datcu, R.; Chowdhary, A.; Arendrup, M.A. Rezafungin In Vitro Activity against Contemporary Nordic Clinical Candida Isolates and Candida auris Determined by the EUCAST Reference Method. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02438-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03667690?term=rezafungin&draw=2&rank=2 (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- Van Arnam, E.; Sit, C.S.W.; Ruzzini, A.C.; Clardy, J.C.; Currie, C.; Pinto-Tomas, A.A. Antifungal compounds comprising selvamicin and anologs. PCT Int. Appl. (2017) WO 2017210565 A1 20171207, 7 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, L.S.; Butcher, M.C.; Short, B.; McKloud, E.; Delaney, C.; Kean, R.; Monteiro, D.R.; Williams, C.; Ramage, G.; Brown, J.L. Chitosan Ameliorates Candida auris Virulence in a Galleria mellonella Infection Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00476-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, R.; Loonker, S. Synthesis characterization and biological evaluation of chitosan epoxy n-methyl piperazine as antimicrobial agent. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2017, 45, 266–270. [Google Scholar]

- Dekkerová, J.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L.; Bujdáková, H. Activity of anti-CR3-RP polyclonal antibody against biofilms formed by Candida auris a multidrug-resistant emerging fungal pathogen. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 38, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

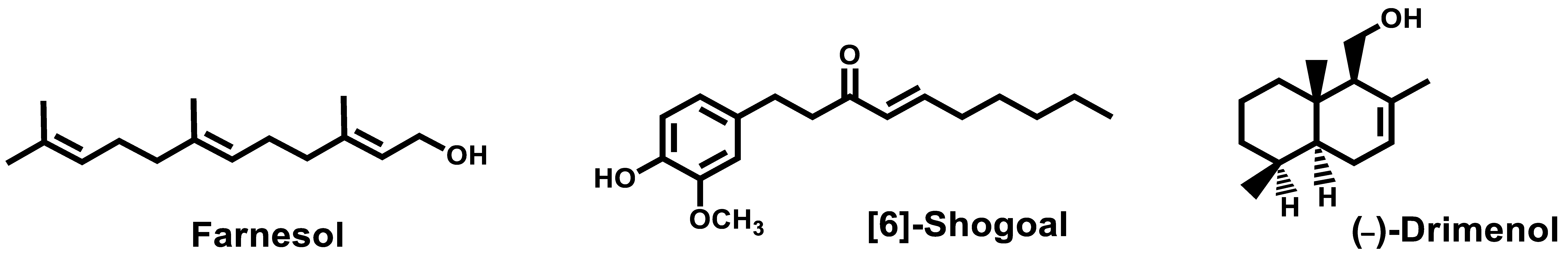

- Srivastava, V.; Ahmad, A. Abrogation of pathogenic attributes in drug resistant Candida auris strains by farnesol. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 0233102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, F.; Vitalis, E.; Jakab, A.; Borman, A.M.; Forgacs, L.; Toth, Z.; Majoros, L.; Kovacs, R. In vitro and in vivo Effect of Exogenous Farnesol Exposure Against Candida auris. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, F.; Toth, Z.; Daroczi, L.; Szekely, A.; Borman, A.M.; Majoros, L.; Kovacs, R. Farnesol increases the activity of echinocandins against Candida auris biofilms. Med. Mycol. 2020, 58, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-R.; Eom, Y.-B. Antifungal and anti-biofilm effects of 6-shogaol against Candida auris. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edouarzin, E.; Horn, C.; Paudyal, A.; Zhang, C.; Lu, J.; Tong, Z.; Giaever, G.; Nislow, C.; Veerapandian, R.; Hua, D.H.; et al. Broad-spectrum antifungal activities and mechanism of drimane sesquiterpenoids. Microb. Cell 2020, 7, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

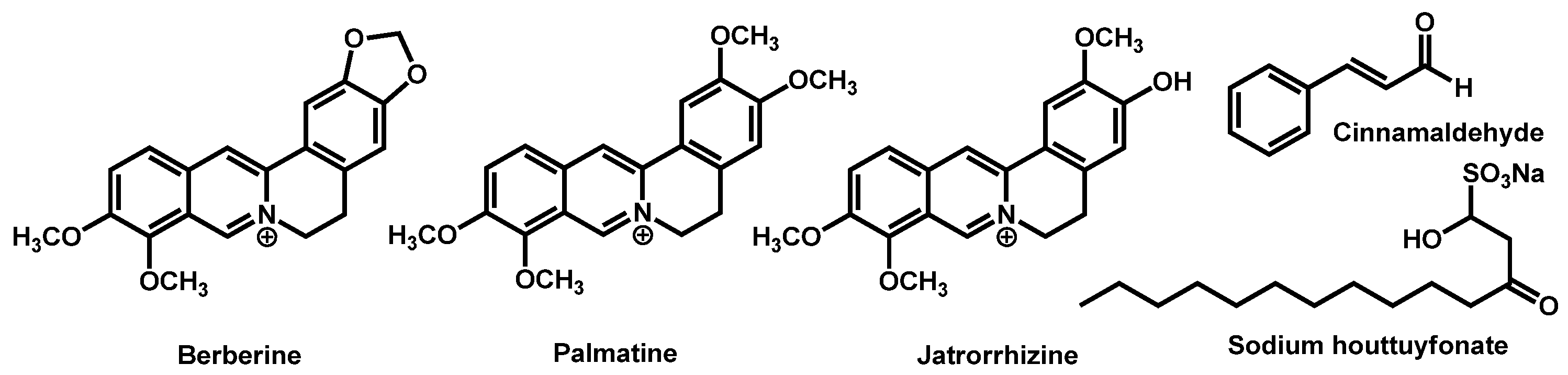

- Juanjuan, L.; Qianqian, L.; Changzhong, W.; Jing, S.; Tianming, W.; Daqiang, W.; Kelong, M.; Guiming, Y.; Dengke, Y. Antifungal evaluation of traditional herbal monomers and their potential for inducing cell wall remodeling in Candida albicans and Candida auris. Biofouling 2020, 36, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.H.; Graham, L.; Adukwu, E.C. In vitro antifungal activity of Cinnamomum zeylanicum bark and leaf essential oils against Candida albicans and Candida auris. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 8911–8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasaballah, A.I.; El-Naggar, H.A. Antimicrobial activities of some marine sponges and its biological repellent effects against Culex pipiens (Diptera: Culicidae). Ann. Res. Rev. Biol. 2017, 12, e1007460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

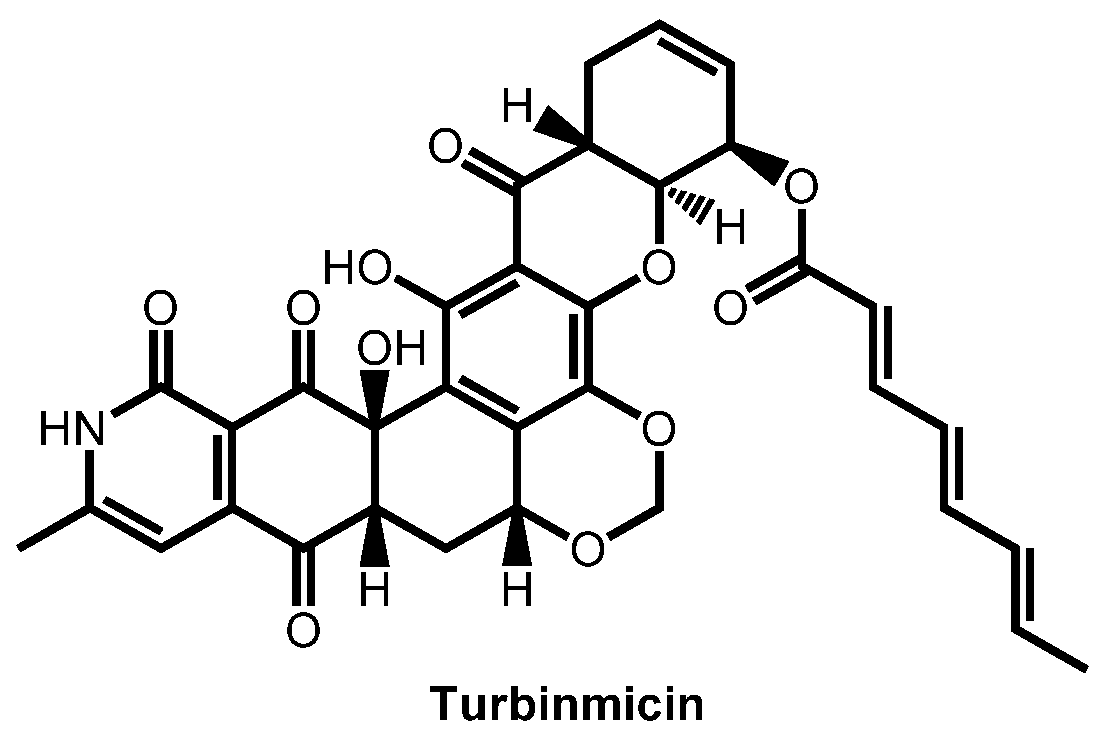

- Zhang, F.; Zhao, M.; Braun, D.R.; Ericksen, S.S.; Piotrowski, J.S.; Nelson, J.; Peng, J.; Ananiev, G.E.; Chanana, S.; Barns, K.; et al. A marine microbiome antifungal targets urgent-threat drug-resistant fungi. Science 2020, 370, 974–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, F.; Zarnowski, R.; Barns, K.J.; Jones, R.; Fossen, J.L.; Sanchez, H.; Rajski, S.R.; Audhya, A.; Bugni, T.S.; et al. Turbinmicin inhibits Candida biofilm growth by disrupting fungal vesicle-mediated trafficking. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e145123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugni, T.S.; Zhang, F.; Braun, D.R.; Andes, D.R.; Zhao, M. Turbinmicin compounds compositions and uses thereof. PCT Int. Appl. (2020) WO 2020146155 A1 20200716, 16 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- López-Abarrategui, C.; McBeth, C.; Mandal, S.M.; Sun, Z.J.; Heffron, G.; Alba-Menéndez, A.; Migliolo, L.; Reyes-Acosta, O.; García-Villarino, M.; Nolasco, D.O.; et al. Cm-p5: An antifungal hydrophilic peptide derived from the coastal mollusk Cenchritis muricatus (Gastropoda: Littorinidae). FASEB J. 2015, 29, 3315–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Vicente, F.E.; Gonzalez-Garcia, M.; Diaz Pico, E.; Moreno-Castillo, E.; Garay, H.E.; Rosi, P.E.; Jimenez, A.M.; Campos-Delgado, J.A.; Rivera, D.G.; Chinea, C.; et al. Design of a Helical-Stabilized Cyclic and Nontoxic Analogue of the Peptide Cm-p5 with Improved Antifungal Activity. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 19081–19095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiczek, D.; Raber, H.; Rosenau, F.; Gonzalez-Garcia, M.; Otero-Gonzalez, A.J.; Morales-Vicente, F.; Staendker, L. Derivates of the Antifungal Peptide Cm-p5 Inhibit Development of Candida auris Biofilms In Vitro. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Shrivastava, M.; Narayanan, N.N.; Thakur, R.L.; Chakrabarti, A.; Roy, U. Evaluation of Antifungal Efficacy of Three New Cyclic Lipopeptides of the Class Bacillomycin from Bacillus subtilis RLID 12.1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 62, e01457-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, P.M.; Goncalves, S.; Santos, N.C. Defensins: Antifungal lessons from eukaryotes. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swidergall, M.; Ernst, J.F. Interplay between Candida albicans and the antimicrobial peptide armory. Eukaryot. Cell 2014, 13, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, V.M.S.; O’Neil, D.A. Commercialization of antifungal peptides. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2013, 26, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vriens, K.; Cammue, B.P.A.; Thevissen, K. Antifungal plant defensins: Mechanisms of action and production. Molecules 2014, 19, 12280–12303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batoni, G.; Maisetta, G.; Brancatisano, F.L.; Esin, S.; Campa, M. Use of antimicrobial peptides against microbial biofilms: Advantages and limits. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 256–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathirana, R.U.; Friedman, J.; Norris, H.L.; Salvatori, O.; McCall, A.D.; Kay, J.; Edgerton, M. Fluconazole-Resistant Candida auris Is Susceptible to Salivary Histatin 5 Killing and to Intrinsic Host Defenses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01872-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, V.; Garcia, A.; Tran, D.Q.; Schaal, J.B.; Tran, P.; Ngole, D.; Aqeel, Y.; Tongaonkar, P.; Ouellette, A.J.; Selsted, M.E. Fungicidal Potency and Mechanisms of θ-Defensins against Multidrug-Resistant Candida Species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00111-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Mas, C.; Rossato, L.; Shimizu, T.; Oliveira, E.B.; da Silva Junior, P.I.; Meis, J.F.; Colombo, A.L.; Hayashi, M. Effects of the Natural Peptide Crotamine from a South American Rattlesnake on Candida auris an Emergent Multidrug Antifungal Resistant Human Pathogen. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eijk, M.; Boerefijn, S.; Cen, L.; Rosa, M.; Morren, M.J.H.; van der Ent, C.K.; Kraak, B.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Valdes, I.D.; Haagsman, H.P.; et al. Cathelicidin-inspired antimicrobial peptides as novel antifungal compounds. Med. Mycol. 2020, 58, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

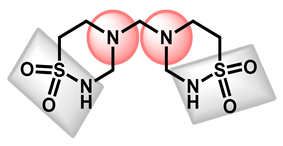

- Hashemi, M.M.; Rovig, J.; Holden, B.S.; Taylor, M.F.; Weber, S.; Wilson, J.; Hilton, B.; Zaugg, A.L.; Ellis, S.W.; Yost, C.D.; et al. Ceragenins are active against drug-resistant Candida auris clinical isolates in planktonic and biofilm forms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.; Atanasova, L.; Jensen, D.F.; Zeilinger, S. Necrotrophic Mycoparasites and Their Genomes. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, K.; Bravo Ruiz, G.; Lorenz, A.; Walker, L.; Gow, N.; Wendland, J. The mycoparasitic yeast Saccharomycopsis schoenii predates and kills multi-drug resistant Candida auris. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, R.W.; Rossato, L.; Valero, C.; Lagrou, K.; Colombo, A.L.; Goldman, G.H. Potential of Gallium as an Antifungal Agent. Front. Cell. Infecti. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, E.K.; Kim, J.H.; Parkin, S.; Awuah, S.G.; Garneau-Tsodikova, S. Distorted Gold(I)-Phosphine Complexes as Antifungal Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 2455–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosgey, J.C.; Jia, L.; Fang, Y.; Yang, J.; Gao, L.; Wang, J.; Nyamao, R.; Cheteu, M.; Tong, D.; Wekesa, V.; et al. Probiotics as antifungal agents: Experimental confirmation and future prospects. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2019, 162, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunyeit, L.; Kurrey, N.K.; Anu-Appaiah, K.A.; Rao, R.P. Probiotic Yeasts Inhibit Virulence of Non-albicans Candida Species. mBio 2019, 10, e02307-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, A. A probiotic for candidiasis? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossoni, R.D.; de Barros, P.P.; Mendonça, I.D.C.; Medina, R.P.; Silva, D.; Fuchs, B.B.; Junqueira, J.C.; Mylonakis, E. The Postbiotic Activity of Lactobacillus paracasei 28.4 Against Candida auris. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, P.; Kuriakose, S. Synthesis of Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Stabilized by Biocompatible Supramolecular β-Cyclodextrin for Biomedical Applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 11, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangadoo, S.; Elbourne, A.; Medvedev, A.E.; Cozzolino, D.; Truong, Y.B.; Crawford, R.J.; Wang, P.Y.; Truong, V.K.; Chapman, J. Facile Route of Fabricating Long-Term Microbicidal Silver Nanoparticle Clusters against Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Candida auris. Coatings 2020, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, H.H.; Ixtepan-Turrent, L.; Jose Yacaman, M.; Lopez-Ribot, J. Inhibition of Candida auris Biofilm Formation on Medical and Environmental Surfaces by Silver Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 21183–21191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleare, L.G.; Li, K.L.; Abuzeid, W.M.; Nacharaju, P.; Friedman, J.M.; Nosanchuk, J.D. NO Candida auris: Nitric Oxide in Nanotherapeutics to Combat Emerging Fungal Pathogen Candida auris. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Munoz, R.; Lopez, F.D.; Lopez-Ribot, J.L. Bismuth Nanoantibiotics Display Anticandidal Activity and Disrupt the Biofilm and Cell Morphology of the Emergent Pathogenic Yeast Candida auris. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Vera-Gonzalez, N. Aspartic protease-triggered antifungal hydrogel. U.S. Pat. Appl. Publ. (2019) US 20190151455 A1 20190523, 23 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kubiczek, D.; Flaig, C.; Raber, H.; Dietz, S.; Kissmann, A.K.; Heerde, T.; Bodenberger, N.; Wittgens, A.; González-Garcia, M.; Kang, F.; et al. A Cerberus-Inspired Anti-Infective Multicomponent Gatekeeper Hydrogel against Infections with the Emerging “Superbug” Yeast Candida auris. Macromol. Biosci. 2020, 20, 2000005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Briffa, S.M.; Swingler, S.; Gibson, H.; Kannappan, V.; Adamus, G.; Kowalczuk, M.; Martin, C.; Radecka, I. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Curcumin-Cyclodextrins Loaded into Bacterial Cellulose-Based Hydrogels for Wound Dressing Applications. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, J.L.; Rello, J.; Marshall, J.; Silva, E.; Anzueto, A.; Martin, C.D.; Moreno, R.; Lipman, J.; Gomersall, C.; Sakr, Y.; et al. EPIC II Group of Investigators. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 2009, 302, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadnum, J.L.; Shaikh, A.A.; Piedrahita, C.T.; Sankar, T.; Jencson, A.L.; Larkin, E.L.; Ghannoum, M.A.; Donskey, C.J. Effectiveness of disinfectants against Candida auris and other Candida species. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2017, 38, 1240–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabhaneni, S.; Kallen, A.; Tsay, S.; Chow, N.; Welsh, R.; Kerins, J.; Kemble, S.K.; Pacilli, M.; Black, S.R.; Landon, E.; et al. Investigation of the first seven reported cases of Candida auris a globally emerging invasive multidrug-resistant fungus-United States May 2013-August 2016. Am. J. Transplant. 2017, 17, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadnum, J.L.; Shaikh, A.A.; Piedrahita, C.T.; Jencson, A.L.; Larkin, E.L.; Ghannoum, M.A.; Donskey, C.J. Relative Resistance of the Emerging Fungal Pathogen Candida auris and Other Candida Species to Killing by Ultraviolet Light. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 2018, 39, 94–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslo, C.; du Plooy, M.; Coetzee, J. The efficacy of pulsed-xenon ultraviolet light technology on Candida auris. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, T.; Chowdhary, A.; Meis, J.F.; Voss, A. Killing of Candida auris by UV-C: Importance of exposure time and distance. Mycoses 2019, 62, 408–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemons, A.R.; McClelland, T.L.; Martin, S.B.; Lindsley, W.G.; Green, B.J. Inactivation of the multi-drug resistant pathogen Candida auris using ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI). J. Hosp. Infect. 2020, 105, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Structure | Name | Class | Growth Inhibition (%) at 50 µM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL 10093 | JCM 15448 | KCTC 17810 | |||

Alexidine dihydrochloride | Antibacterial | 97 | 97 | 97 | |

| Artemisinin | Antimalarial | 65 | 56 | 61 |

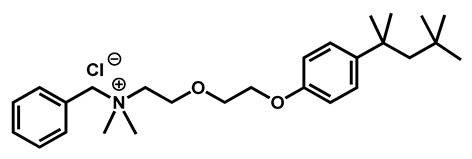

Benzethonium chloride | Antibacterial | 96 | 97 | 100 | |

Chlorhexidine | Antibacterial | 98 | 99 | 98 | |

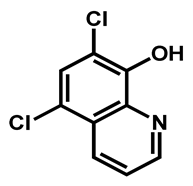

| Chloroxine | Antibacterial | 95 | 97 | 98 |

| Ciclopirox ethanolamine | Antibacterial/Antifungal | 94 | 97 | 94 |

| Clioquinol | Antiamebic/Antibacteria | 89 | 93 | 93 |

Dequalinium dichloride | Antibacterial | 81 | 86 | 89 | |

| Dimethisoquin hydrochloride | Antipruritic | 59 | 65 | 51 |

| Dyclonine hydrochloride | Local anesthetic | 63 | 63 | 54 |

| Ebselen | Anti-inflammatory | 87 | 91 | 92 |

| Fipexide hydrochloride | Anti-fatigue | 68 | 63 | 54 |

| Guanadrel sulfate | Antihypertensive | 97 | 97 | 97 |

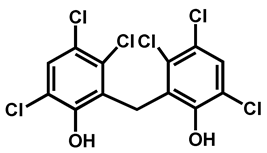

| Hexachlorophene | Antiseptic | 97 | 98 | 86 |

| Methyl benzethonium chloride | Antibacterial | 98 | 97 | 100 |

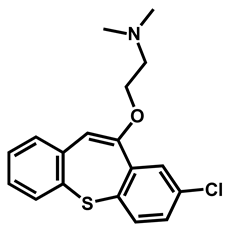

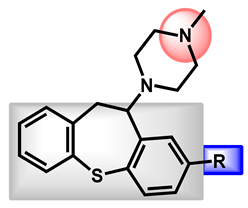

| Methiothepin maleate | Antipsychotic | 74 | 72 | 64 |

| MK 801 hydrogen maleate | Anticonvulsant | 98 | 98 | 97 |

Pyrvinium pamoate | Anthelmintic | 40 | 76 | 61 | |

| Prochlorperazine dimaleate | Antiemetic/Antipsychotic | 71 | 66 | 72 |

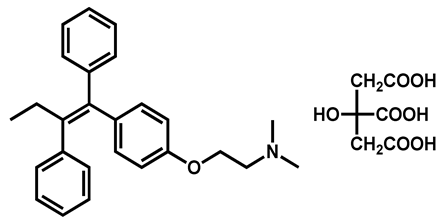

| Tamoxifen citrate | Antineoplastic | 98 | 98 | 90 |

| Thiethylperazine dimalate | Antiemetic | 68 | 90 | 86 |

Thonzonium bromide | Antiseptic | 98 | 98 | 98 | |

| Trifluoperazine dihydrochloride | Antiemetic | 54 | 88 | 61 |

| Rolipram | Antidepressant | 98 | 97 | 91 |

| Sertraline | Antidepressant | 59 | 88 | 56 |

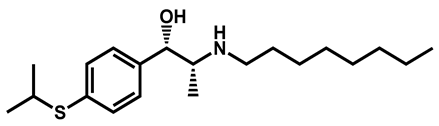

| Suloctidil | Antiplatelet | 96 | 99 | 78 |

| Zotepine | Antipsychotic | 59 | 63 | 56 |

| Entry | Structures | Log P 1 | TPSA 2 (Å) | M (g/mol) | Druglikeliness 3 (Alert) | BBB Permeant 4 | GI Absorption 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

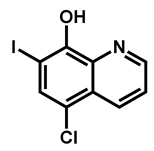

| 1 |  R = I = Clioquinol R = Cl = Chloroxine | 2.96 | 33.12 | 305.50 | XLOGP > 3.5 | Yes | High |

| 2 | 2.86 | 33.12 | 214.05 | MW < 250, XLOGP > 3.5 | Yes | High | |

| 3 |  Dimethisoquin Dimethisoquin | 3.66 | 25.36 | 272.39 | XLOGP > 3.5 | Yes | High |

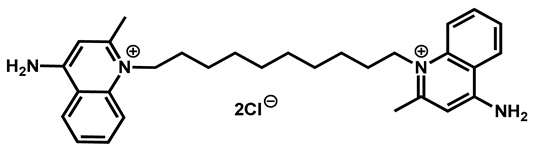

| 4 |  Dequalinium dichloride Dequalinium dichloride | 4.14 | 59.80 | 456.67 | MW > 350 Rotors > 7 XLOGP > 3.5 | No | High |

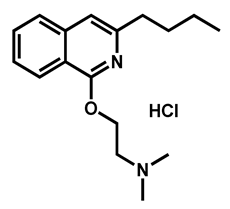

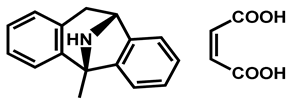

| 5 |  Pyrvinium active compound Pyrvinium active compound | 4.29 | 12.05 | 382.52 | MW > 350 XLOGP > 3.5 | Yes | High |

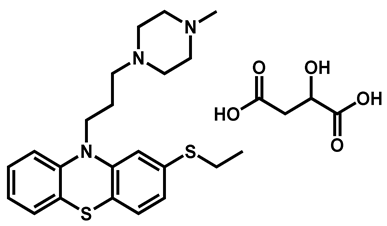

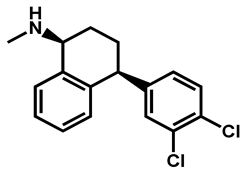

| Entry | Structure | R | LogP 1 | TPSA (Å) 2 | M (g/mol) | Druglikeliness (Alert) 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

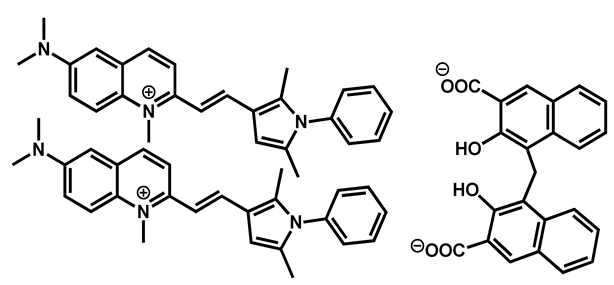

| 1 |  | -S-CH3 (Methiothepin) | 3.94 | 57.08 | 356.55 | MW > 350, XLOGP > 3.5 |

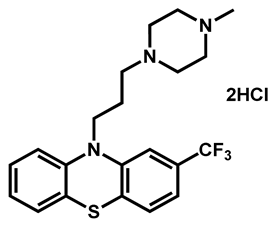

| 2 | -Cl (Zotepine) | 4.37 | 37.77 | 331.86 | XLOGP > 3.5 | |

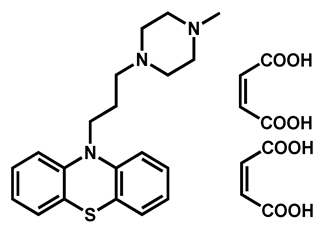

| 3 |  | -H (Prochlorperazine) | 3.47 | 35.02 | 339.50 | XLOGP > 3.5 |

| 4 | -S-CH2CH3 (Thiethylperazine) | 4.43 | 60.32 | 399.62 | MW > 350, XLOGP > 3.5 | |

| 5 | -CF3 (Trifluoperazine) | 4.53 | 35.02 | 407.50 | MW > 350, XLOGP > 3.5 |

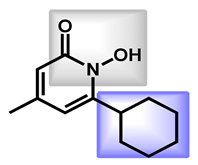

| Entry | Structures | LogP 1 | TPSA 2 (Å) | M (g/mol) | Druglikeliness 3 (Alert) | BBB Permeant 4 | GI 5 Absorption |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

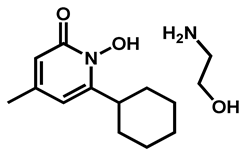

| 1 |  Ciclopirox | 2.38 | 42.23 | 207.27 | MW < 250 | Yes | High |

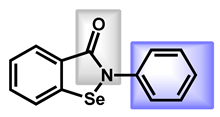

| 2 |  Ebselen | 1.75 | 22.0 | 274.18 | No alert | Yes | High |

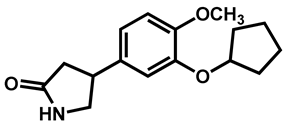

| 3 |  Rolipram Rolipram | 2.44 | 47.56 | 275.34 | No alert | Yes | High |

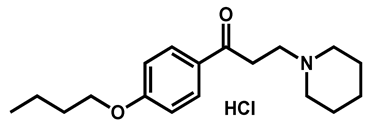

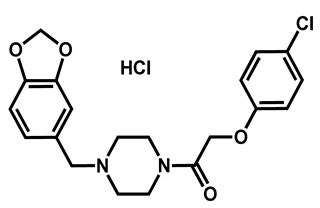

| 4 |  Fipexide Fipexide | 2.82 | 51.24 | 388.84 | MW > 350 | Yes | High |

| 5 |  Taurolidine | −1.53 | 115.58 | 284.36 | 0 alert | No | Low |

| Test Agents | Structure | MIC Values (µg/mL) (n = 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Range) | |||

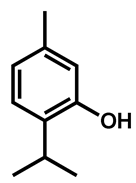

| C. auris | Carvacrol |  | 125 (62–250) |

| Thymol |  | 312 (156–625) | |

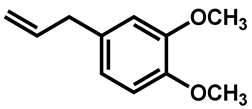

| Eugenol |  | 625 (312–1250) | |

| Methyl eugenol |  | 1250 (625–1250) |

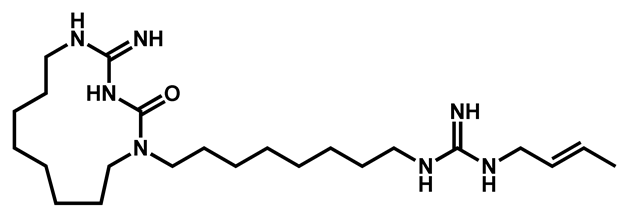

BM1 BM1 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC and MBC Rage (µg/mL) against Candida Species | |||||||||||

| C. albicans | C. tropicalis | C. parapsilosis | C. glabrata | C. krusei | C. auris | ||||||

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC |

| 0.125–2 | 2–4 | 2 | 2–4 | 8–16 | 32–64 | 32–64 | 8–64 | 8–64 | 64–128 | 8–64 | 128–256 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Billamboz, M.; Fatima, Z.; Hameed, S.; Jawhara, S. Promising Drug Candidates and New Strategies for Fighting against the Emerging Superbug Candida auris. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9030634

Billamboz M, Fatima Z, Hameed S, Jawhara S. Promising Drug Candidates and New Strategies for Fighting against the Emerging Superbug Candida auris. Microorganisms. 2021; 9(3):634. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9030634

Chicago/Turabian StyleBillamboz, Muriel, Zeeshan Fatima, Saif Hameed, and Samir Jawhara. 2021. "Promising Drug Candidates and New Strategies for Fighting against the Emerging Superbug Candida auris" Microorganisms 9, no. 3: 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9030634

APA StyleBillamboz, M., Fatima, Z., Hameed, S., & Jawhara, S. (2021). Promising Drug Candidates and New Strategies for Fighting against the Emerging Superbug Candida auris. Microorganisms, 9(3), 634. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9030634