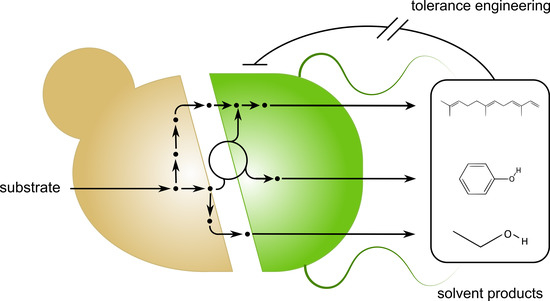

Increasing Solvent Tolerance to Improve Microbial Production of Alcohols, Terpenoids and Aromatics

Abstract

1. Introduction

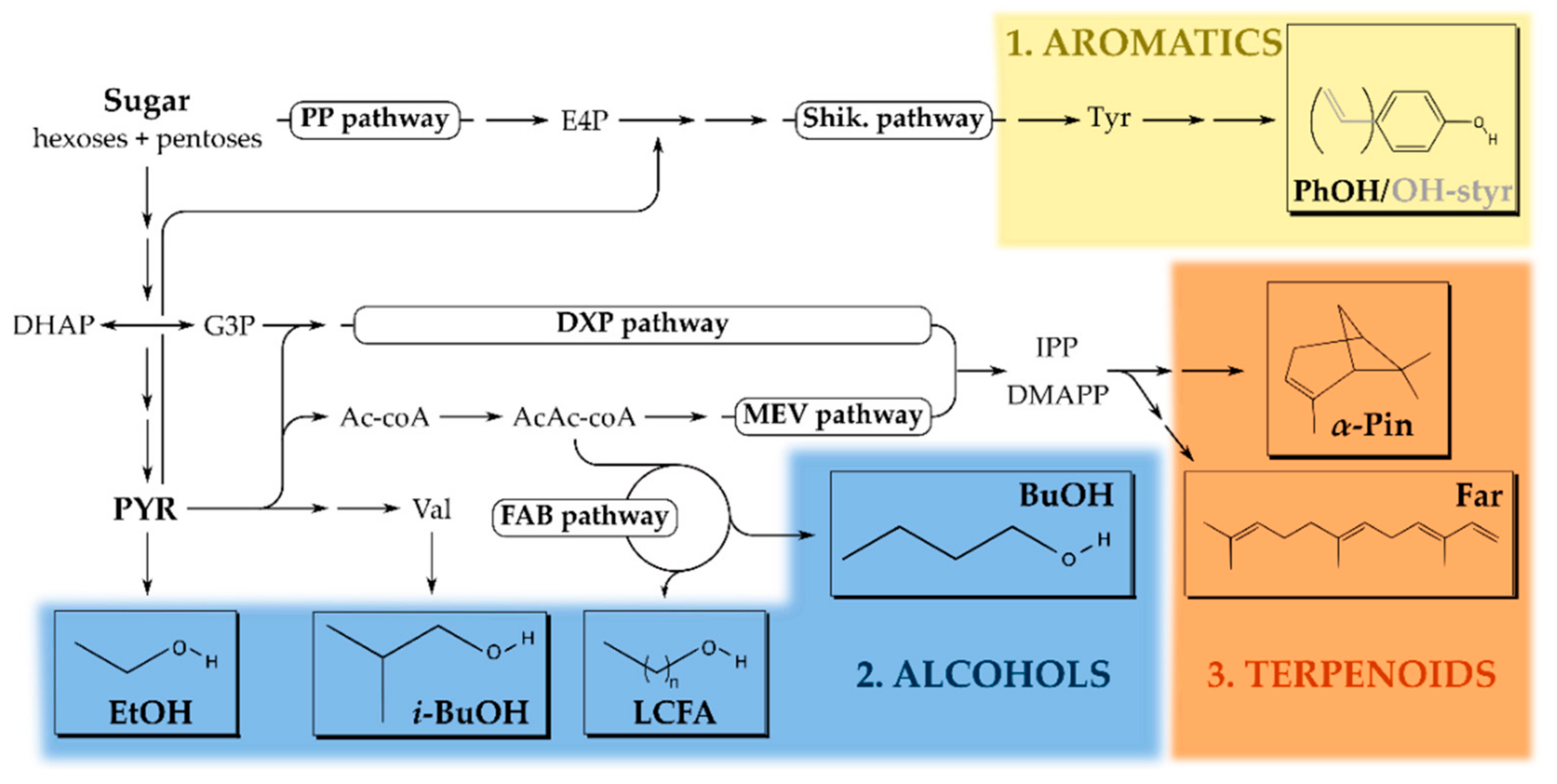

2. Production of Solvent Molecules Using Microorganisms

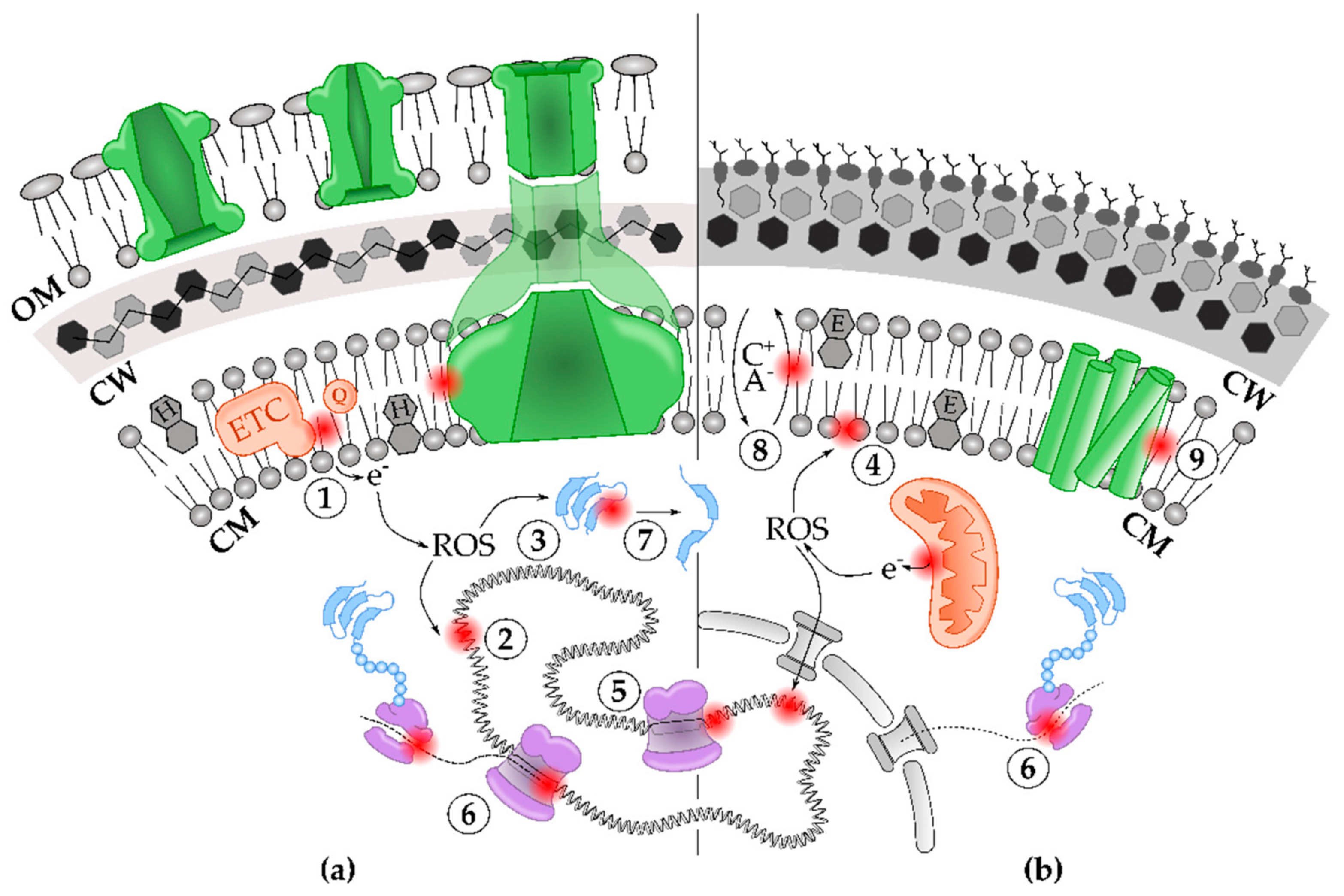

3. The Primary Cell Components and Processes Impacted by Solvent Toxicity

3.1. Solvents Disrupt Cell Envelope Integrity

3.2. Accumulation of ROS and Radicals during Solvent Stress Damage Biomolecules Inside the Cell

3.3. Solvents Damage DNA and Impede Transcription and Translation Processes

3.4. Solvents Affect the Structure and Function of Proteins

4. Adaptive Responses Protect Cells from Solvent Exposure

4.1. Increased Mutation Rates Accelerate Solvent Adaptation

4.2. Maintaining Cell Envelope Integrity to Overcome Solvent Stress

4.3. Adaptive Mutations Related to the Transcription and Translation Machinery Counter Solvent-Associated Aberrations

4.4. Protein Folding and Chaperone Activity Restore Protein Function

4.5. Cell Metabolism Is Reprogrammed during Solvent Exposure

4.6. Engaging Global Stress Responses Protects the Cell in the Presence of Solvent Molecules

5. Engineering Microorganisms for Improved Tolerance and Production

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liao, J.C.; Mi, L.; Pontrelli, S.; Luo, S. Fuelling the future: Microbial engineering for the production of sustainable biofuels. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, T.E.; Salazar, M.J.; Weng, L.L.; Palsson, B.O.; Feist, A.M. The emergence of adaptive laboratory evolution as an efficient tool for biological discovery and industrial biotechnology. Metab. Eng. 2019, 56, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Shen, X.; Jain, R.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.; Yan, Y.; Yuan, Q. Synthesis of chemicals by metabolic engineering of microbes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3760–3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Shao, Z.; Zhao, H. Engineering microbial factories for synthesis of value-added products. J. Ind. Microbiol. 2011, 38, 873–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, K.Y.; Araki, M.; Okai, N.; Wakai, S.; Hasunuma, T.; Kondo, A. Development of bio-based fine chemical production through synthetic bioengineering. Microb. Cell Factories 2014, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckner, M.; Ivey, M.L.; Phister, T.G. Microbial contamination of fuel ethanol fermentations. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 53, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, B.R.; Lawrence, S.J.; Leclaire, J.P.R.; Powell, C.D.; Smart, K.A. Yeast responses to stresses associated with industrial brewery handling. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 31, 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eardley, J.; Timson, D.J. Yeast Cellular Stress: Impacts on Bioethanol Production. Fermentation 2020, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Teo, W.; Chen, B.; Leong, S.S.J.; Chang, M.W. Microbial tolerance engineering toward biochemical production: From lignocellulose to products. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2014, 29, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.J.; De Bont, J.A.M. Adaptation mechanisms of microorganisms to the toxic effects of organic solvents on membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1996, 1286, 225–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.M.; Lee, N.R.; Woo, J.M.; Choi, W.; Zimmermann, M.; Blank, L.M.; Park, J.B. Ethanol reduces mitochondrial membrane integrity and thereby impacts carbon metabolism of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012, 12, 675–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Zhao, J.; Yu, L.; Tang, I.C.; Xue, C.; Yang, S.T. Engineering Clostridium acetobutylicum with a histidine kinase knockout for enhanced n-butanol tolerance and production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alper, H.; Moxley, J.; Nevoigt, E.; Fink, G.R.; Stephanopoulos, G. Engineering Yeast Transcription Machinery for Improved Ethanol Tolerance and Production. Science 2006, 314, 1565–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, L.; Tuyishime, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, K.; Gao, N.; Zhang, Z.; Ni, X.; Feng, J.; Yuan, Q.; et al. Adaptive laboratory evolution enhances methanol tolerance and conversion in engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, L.; Liu, R.; Foster, K.E.O.; Choudhury, A.; Cook, S.; Cameron, J.C.; Srubar, W.V.; Gill, R.T. Genome engineering of E. coli for improved styrene production. Metab. Eng. 2020, 57, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Khosla, C. Genetic Engineering of Escherichia coli for Biofuel Production. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2010, 44, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppolu, V.; Vasigala, V.K. Role of Escherichia coli in Biofuel Production. Microbiol. Insights 2016, 9, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swings, J.; De Ley, J. The biology of Zymomonas. Bacteriol. Rev. 1977, 41, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.X.; Wu, B.; Qin, H.; Ruan, Z.Y.; Tan, F.R.; Wang, J.L.; Shui, Z.X.; Dai, L.C.; Zhu, Q.L.; Pan, K.; et al. Zymomonas mobilis: A novel platform for future biorefineries. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2014, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fei, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Contreras, L.M.; Utturkar, S.M.; Brown, S.D.; Himmel, M.E.; Zhang, M. Zymomonas mobilis as a model system for production of biofuels and biochemicals. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 699–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Bao, T.; Yang, S.T. Engineering Clostridium for improved solvent production: Recent progress and perspective. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 5549–5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, H.G.; Jang, Y.S.; Cho, C.; Lee, J.; Binkley, R.; Lee, S.Y. One hundred years of clostridial butanol fermentation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.; Wittmann, C. Industrial Microorganisms: Corynebacterium glutamicum. In Industrial Biotechnology: Microorganisms, 1st ed.; Wittmann, C., Liao, J.C., Eds.; Wiley: Weinheim, Germany, 2016; pp. 183–220. [Google Scholar]

- Betteridge, A.; Grbin, P.; Jiranek, V. Improving Oenococcus oeni to overcome challenges of wine malolactic fermentation. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger-Weber, S.; Heras, J.M.; Suarez, C. Lactobacillus plantarum, a new biological tool to control malolactic fermentation: A review and an outlook. Beverages 2020, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.L.A.; Bracher, J.M.; Papapetridis, I.; Verhoeven, M.D.; De Bruijn, H.; De Waal, P.P.; Van Maris, A.J.A.; Klaassen, P.; Pronk, J.T. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains for second-generation ethanol production: From academic exploration to industrial implementation. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017, 17, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, G.M.; Stewart, G.G. Saccharomyces cerevisiae in the Production of Fermented Beverages. Beverages 2016, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, G.G.; Heinzle, E.; Wittmann, C.; Gombert, A.K. The yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus and its biotechnological potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 79, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, A.; Gerliani, N.; Aïder, M. Kluyveromyces marxianus: An emerging yeast cell factory for applications in food and biotechnology. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 333, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbogbo, F.K.; Coward-Kelly, G. Cellulosic ethanol production using the naturally occurring xylose-fermenting yeast, Pichia stipitis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2008, 30, 1515–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta-Yahya, P.P.; Zhang, F.; del Cardayre, S.B.; Keasling, J.D. Microbial engineering for the production of advanced biofuels. Nature 2012, 488, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Abdallah, Q.; Nixon, B.T.; Fortwendel, J.R. The enzymatic conversion of major algal and cyanobacterial carbohydrates to bioethanol. Front. Energy Res. 2016, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.T.; Liao, J.C. Frontiers in microbial 1-butanol and isobutanol production. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Lee, J.; Jang, Y.-S.; Lee, S.Y. Metabolic Engineering of Microorganisms for the Production of Higher Alcohols. mBio 2014, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gronenberg, L.S.; Marcheschi, R.J.; Liao, J.C. Next generation biofuel engineering in prokaryotes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013, 17, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, Y. Alcohol fuels: Current Status and Future Direction. In Alcohol Fuels—Current Technologies and Future Prospect; Yun, Y., Ed.; InTech Open: London, UK, 2020; p. 27. [Google Scholar]

- Isikgor, F.H.; Becer, C.R. Lignocellulosic biomass: A sustainable platform for the production of bio-based chemicals and polymers. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 4497–4559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascal, M. Chemicals from biobutanol: Technologies and markets. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2012, 6, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, B.G.; Meylemans, H.A.; Quintana, R.L. Synthesis of renewable plasticizer alcohols by formal anti-Markovnikov hydration of terminal branched chain alkenes via a borane-free oxidation/reduction sequence. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 2450–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Phulara, S.C. Metabolic engineering for isoprenoid-based biofuel production. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2015, 119, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phulara, S.C.; Chaturvedi, P.; Gupta, P. Isoprenoid-based biofuels: Homologous expression and Heterologous Expression in Prokaryotes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 5730–5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- George, K.W.; Alonso-Gutierrez, J.; Keasling, J.D.; Lee, T.S. Isoprenoid Drugs, Biofuels, and Chemicals—Artemisinin, Farnesene, and Beyond. In Biotechnology of Isoprenoids, 1st ed.; Schrader, J., Bohlmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 148, pp. 355–389. [Google Scholar]

- Perego, C.; Pollesel, P. Advances in aromatics processing using Zeolite catalysts. In Advances in Nanoporous Materials, 1st ed.; Ernst, S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 97–149. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad-Rezaei, R.; Massoumi, B.; Abbasian, M.; Jaymand, M. Novel strategies for the synthesis of hydroxylated and carboxylated polystyrenes. J. Polym. Res. 2018, 25, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.T.; Lee, W.J.; Chang, J.H.; Lim, A.R. Dependence of the physical properties and molecular dynamics of thermotropic liquid crystalline copolyesters on p-hydroxybenzoic acid content. Polymers 2020, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huccetogullari, D.; Luo, Z.W.; Lee, S.Y. Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for production of aromatic compounds. Microb. Cell Factories 2019, 18, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijnen, J.P.; Verhoef, S.; Briedjlal, A.A.; De Winde, J.H.; Ruijssenaars, H.J. Improved p-hydroxybenzoate production by engineered Pseudomonas putida S12 by using a mixed-substrate feeding strategy. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, S.; Wierckx, N.; Westerhof, R.G.M.; De Winde, J.H.; Ruijssenaars, H.J. Bioproduction of p-hydroxystyrene from glucose by the solvent-tolerant bacterium Pseudomonas putida S12 in a two-phase water-decanol fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buehler, E.A.; Mesbah, A. Kinetic study of acetone-butanol-ethanol fermentation in continuous culture. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0158243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atsumi, S.; Hanai, T.; Liao, J.C. Non-fermentative pathways for synthesis of branched-chain higher alcohols as biofuels. Nature 2008, 451, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beller, H.R.; Lee, T.S.; Katz, L. Natural products as biofuels and bio-based chemicals: Fatty acids and isoprenoids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 1508–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpenoid Backbone Biosynthesis. Available online: https://www.genome.jp/kegg-bin/show_pathway?map00900 (accessed on 13 October 2020).

- Silhavy, T.J.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. The Bacterial Cell Envelope. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalebina, T.S.; Rekstina, V.V. Molecular Organization of Yeast Cell Envelope. Mol. Biol. 2019, 53, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombek, K.M.; Ingram, L.O. Effects of ethanol on the Escherichia coli plasma membrane. J. Bacteriol. 1984, 157, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, L.O. Changes in Lipid Composition of Escherichia coli Resulting from Growth with Organic Solvents and with Food Additives. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1977, 33, 1233–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, S.E.; Brown, C.A.; Nizza, D.T.; Gawrisch, K. Nuclear Overhauser Enhancement Spectroscopy Cross-Relaxation Rates and Ethanol Distribution across Membranes. Biophys. J. 2002, 82, 1396–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtovenko, A.A.; Anwar, J. Interaction of Ethanol with Biological Membranes: The Formation of Non-bilayer Structures within the Membrane Interior and their Significance. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 1983–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patra, M.; Salonen, E.; Terama, E.; Vattulainen, I.; Faller, R.; Lee, B.W.; Holopainen, J.; Karttunen, M. Under the Influence of Alcohol: The Effect of Ethanol and Methanol on Lipid Bilayers. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, H.V.; Longo, M.L. The Influence of Short-Chain Alcohols on Interfacial Tension, Mechanical Properties, Area/Molecule, and Permeability of Fluid Lipid Bilayers. Biophys. J. 2004, 87, 1013–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranenburg, M.; Smit, B. Simulating the effect of alcohol on the structure of a membrane. FEBS Lett. 2004, 568, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vanegas, J.M.; Contreras, M.F.; Faller, R.; Longo, M.L. Role of Unsaturated Lipid and Ergosterol in Ethanol Tolerance of Model Yeast Biomembranes. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqil, M.; Ahad, A.; Sultana, Y.; Ali, A. Status of terpenes as skin penetration enhancers. Drug Discov. Today 2007, 12, 1061–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermaas, J.V.; Bentley, G.J.; Beckham, G.T.; Crowley, M.F. Membrane Permeability of Terpenoids Explored with Molecular Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 10349–10361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, T.C.R.; Krömer, J.O.; Nielsen, L.K. Physiological and transcriptional responses of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to d-limonene show changes to the cell wall but not to the plasma membrane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 3590–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Wei, D.; Yang, Y.; Shang, Y.; Li, G.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, Q.; Xu, Y. Systems-level understanding of ethanol-induced stresses and adaptation in E. coli. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, L.; Vreeland, N.S. Differential Effects of Ethanol and Hexanol on the Escherichia coli Cell Envelope. J. Bacteriol. 1980, 144, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linhová, M.; Patáková, P.; Lipovský, J.; Fribert, P.; Paulová, L.; Rychtera, M.; Melzoch, K. Development of flow cytometry technique for detection of thinning of peptidoglycan layer as a result of solvent production by Clostridium pasteurianum. Folia Microbiol. 2010, 55, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikaido, H. Molecular Basis of Bacterial Outer Membrane Permeability Revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1996, 67, 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, T.; Poddar, R.K. Ethanol-induced leaching of lipopolysaccharides from E. coli surface inhibits bacteriophage ΦX174 infection. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 1994, 3, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, K.L.; Silhavy, T.J. Making a membrane on the other side of the wall. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2018, 1862, 1386–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynildsen, M.P.; Liao, J.C. An integrated network approach identifies the isobutanol response network of Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uribe, S.; Ramirez, J.; Pena, A. Effects of beta-pinene on Yeast Membrane Functions. Yeast 1985, 161, 1195–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelo, C.; Uden, N. Van Effects of Ethanol and Other Alkanols on the General Amino Acid Permease of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1984, 26, 403–405. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, C.; Alonso, A.; Garcia, I.; Romay, C. Effect of Ethanol on Glucose Transport, Key Glycolytic Enzymes, and Proton Extrusion in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1988, 32, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treistman, S.N.; Martin, G.E. BK Channels: Mediators and models for alcohol tolerance. Trends Neurosci. 2009, 32, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kohanski, M.A.; Dwyer, D.J.; Hayete, B.; Lawrence, C.A.; Collins, J.J. A Common Mechanism of Cellular Death Induced by Bactericidal Antibiotics. Cell 2007, 130, 797–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladjouzi, R.; Bizzini, A.; Lebreton, F.; Sauvageot, N.; Rincé, A.; Benachour, A.; Hartke, A. Analysis of the tolerance of pathogenic enterococci and Staphylococcus aureus to cell wall active antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 2083–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imlay, J.A.; Fridovichs, I. Assay of Metabolic Superoxide Production in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1991, 266, 6957–6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Gao, J.; Song, H.; Tan, X. Ethanol Induces Autophagy Regulated by Mitochondrial ROS in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Microbiol. Biotecnol. 2018, 28, 1982–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, H.K.; Stickel, F. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-mediated carcinogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veith, A.; Moorthy, B. Role of cytochrome P450s In the generation and metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Oh, Y.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Lim, S.; Jo, K. Analysis of alcohol-induced DNA damage in Escherichia coli by visualizing single genomic. Analyst 2016, 141, 4326–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touati, D. Iron and Oxidative Stress in Bacteria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000, 373, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharwalova, L.; Sigler, K.; Dolezalova, J.; Masak, J.; Rezanka, T.; Kolouchova, I. Resveratrol suppresses ethanol stress in winery and bottom brewery yeast by affecting superoxide dismutase, lipid peroxidation and fatty acid profile. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 33, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, L.A. Spin trapping evidence for alcohol-associated oxidative stress. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 32, 953–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burphan, T.; Tatip, S.; Limcharoensuk, T.; Ka, K. Enhancement of ethanol production in very high gravity fermentation by reducing fermentation-induced oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Du, G.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J. Response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to D-limonene-induced oxidative stress. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 6467–6475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, M.C.; Kang, D.O.; Yoon, B.D.; Lee, K. Toluene degradation pathway from Pseudomonas putida F1: Substrate specificity and gene induction by 1-substituted benzenes. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 25, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.T.; Koch, J.R.; Kallio, R.E. Oxidative Degradation of Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Microorganisms. I. Enzymatic Formation of Catechol from Benzene. Biochemistry 1968, 7, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweigert, N.; Zehnder, A.J.B.; Eggen, R.I.L. Chemical properties of catechols and their molecular modes of toxic action in cells, from microorganisms to mammals. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 3, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuniga, M.A.; Dai, J.; Wehunt, M.P.; Zhou, Q. DNA oxidative damage by terpene catechols as analogues of natural terpene quinone methide precursors in the presence of Cu(II) and/or NADH. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 828–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristow, H.; Seyfarth, A. Chromosomal damages by ethanol and acetaldehyde in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as studied by pulsed field gel electrophoresis. Mutat. Res. 1995, 5107, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, J.J.; Devadoss, B.; Winkler, J.; Collins, J.; Walker, G. Oxidation of the Guanine. Science 2012, 336, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, C.C.; Walker, G.C. Incomplete base excision repair contributes to cell death from antibiotics and other stresses. DNA Repair 2018, 71, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, S.P.; Reddy, G.R.; Marnett, L.J. Mutagenicity in Escherichia coli of the major DNA adduct derived from the endogenous mutagen malondialdehyde. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 8652–8657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voordeckers, K.; Colding, C.; Grasso, L.; Pardo, B.; Hoes, L.; Kominek, J.; Gielens, K.; Dekoster, K.; Gordon, J.; Van der Zande, E.; et al. Ethanol exposure increases mutation rate through error-prone polymerases. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, S.; Takeo, I.; Kume, K.; Kanai, M.; Shitamukai, A.; Mizunuma, M.; Miyakawa, T.; Iefuji, H.; Hirata, D.; Hitamukai, A.S.; et al. Effect of Ethanol on Cell Growth of Budding Yeast: Genes That Are Important for Cell Growth in the Presence of Ethanol. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2004, 68, 968–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zore, G.B.; Thakre, A.D.; Jadhav, S.; Karuppayil, S.M. Terpenoids inhibit Candida albicans growth by affecting membrane integrity and arrest of cell cycle. Phytomedicine 2011, 18, 1181–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haft, R.J.F.; Keating, D.H.; Schwaegler, T.; Schwalbach, M.S.; Vinokur, J.; Tremaine, M.; Peters, J.M.; Kotlajich, M.V.; Pohlmann, E.L.; Ong, I.M.; et al. Correcting direct effects of ethanol on translation and transcription machinery confers ethanol tolerance in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E2576–E2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyson, H.J.; Wright, P.E.; Scheraga, H.A. The role of hydrophobic interactions in initiation and propagation of protein folding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 13057–13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabhakaran, E.; Scholtz, J.M.; Pace, C.N.; Trevin, S. Protein structure, stability and solubility in water and other solvents. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2004, 359, 1225–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Wang, J.; Shao, Q.; Shi, J.; Zhu, W. The effects of organic solvents on the folding pathway and associated thermodynamics of proteins: A microscopic view. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirota-nakaoka, N.; Goto, Y. Alcohol-induced Denaturation of β-Lactoglobulin: A Close Correlation to the Alcohol-induced α-Helix Formation of Melittin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1999, 7, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaidis, A.; Andreadis, M.; Moschakis, T. Effect of heat, pH, ultrasonication and ethanol on the denaturation of whey protein isolate using a newly developed approach in the analysis of difference-UV spectra. Food Chem. 2017, 232, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, D.G.; Griffiths-Smith, K.; Algar, E.; Scopes, R.K. Activity and stability of glycolytic enzymes in the presence of ethanol. Biotechnol. Lett. 1982, 4, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagodawithana, T.W.; Whitt, J.T.; Cutaia, A.J. Study of the Feedback Effect of Ethanol on Selected Enzymes of the Glycolytic Pathway. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 1977, 35, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, F.; Peinado, R.A.; Millán, C.; Ortega, J.M.; Mauricio, J.C. Relationship between ethanol tolerance, H+-ATPase activity and the lipid composition of the plasma membrane in different wine yeast strains. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 110, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, Y.A.; Ingram, L.O. Mechanism of Ethanol Inhibition of Fermentation in Zymomonas mobilis CP4. J. Bacteriol. 1985, 164, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabiscol, E.; Ros, J. Oxidative stress in bacteria and protein damage by reactive oxygen species. Int. Microbiol. 2000, 3, 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Bergh, B.; Swings, T.; Fauvart, M.; Michiels, J. Experimental Design, Population Dynamics, and Diversity in Microbial Experimental Evolution. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 82, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horinouchi, T.; Maeda, T.; Furusawa, C. Understanding and engineering alcohol-tolerant bacteria using OMICS technology. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 34, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslowska, K.H.; Makiela-Dzbenska, K.; Fijalkowska, I.J. The SOS system: A complex and tightly regulated response to DNA damage. Environ. Mol. Mutagen. 2019, 60, 368–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufi, B.; Krug, K.; Harst, A.; Macek, B. Characterization of the E. coli proteome and its modifications during growth and ethanol stres. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swings, T.; Van den Bergh, B.; Wuyts, S.; Oeyen, E.; Voordeckers, K.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Fauvart, M.; Verstraeten, N.; Michiels, J. Adaptive tuning of mutation rates allows fast response to lethal stress in Escherichia coli. eLife 2017, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voordeckers, K.; Kominek, J.; Das, A.; Espinosa-Cantú, A.; De Maeyer, D.; Arslan, A.; Van Pee, M.; van der Zande, E.; Meert, W.; Yang, Y.; et al. Adaptation to High Ethanol Reveals Complex Evolutionary Pathways. PLoS Genet. 2015, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, V.C.; Ingram, L.O. Lipid Composition of Zymomonas mobilis: Effects of Ethanol and Glucoset. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 154, 1291–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, P.L.; Lee, K.J.; Skotnicki, M.L.; Tribe, D.E. Ethanol production by Zymomonas mobilis. In Microbial Reactions. Advances in Biochemical Engineering, 1st ed.; Flechter, A., Ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1982; Volume 23, pp. 37–84. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram, L.O. Adaptation of Membrane Lipids to Alcohols. J. Bacteriol. 1976, 125, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, P.; Prasad, R. Relationship between ethanol tolerance and fatty acyl composition in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1989, 30, 294–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.M.; Rosenfield, C.; Knipple, D.C. Ethanol Tolerance in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Is Dependent on Cellular Oleic Acid Content. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 1499–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silveira, F.A.; de Oliveira Soares, D.L.; Bang, K.W.; Balbino, T.R.; de Moura Ferreira, M.A.; Diniz, R.H.S.; de Lima, L.A.; Brandão, M.M.; Villas-Bôas, S.G.; da Silveira, W.B. Assessment of ethanol tolerance of Kluyveromyces marxianus CCT 7735 selected by adaptive laboratory evolution. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 7483–7494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swings, T.; Weytjens, B.; Schalck, T.; Bonte, C.; Verstraeten, N.; Michiels, J.; Marchal, K. Network-based identification of adaptive pathways in evolved ethanol-tolerant bacterial populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 2927–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, S.H.; Blaschek, H.P.; Smith, T.L. Effect of Butanol Challenge and Temperature on Lipid Composition and Membrane Fluidity of Butanol-Tolerant Clostridium acetobutylicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987, 53, 2854–2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, L.M.; Lee, J.Y.; Geraldi, A.; Rahman, Z.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.C. Improved n-butanol tolerance in Escherichia coli by controlling membrane related functions. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 204, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Minty, J.J.; Lesnefsky, A.A.; Lin, F.; Chen, Y.; Zaroff, T.A.; Veloso, A.B.; Xie, B.; Mcconnell, C.A.; Ward, R.J.; Schwartz, D.R.; et al. Evolution combined with genomic study elucidates genetic bases of isobutanol tolerance in Escherichia coli. Microb. Cell Factories 2011, 10, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, M.; Katayama, T.; Tamaki, H.; Mitani, Y.; Meng, X.Y.; Hori, T.; Narihiro, T.; Morita, N.; Hoshino, T.; Yumoto, I.; et al. Isolation of butanol- and isobutanol-tolerant bacteria and physiological characterization of their butanol tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 6998–7005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Grandvalet, C.; Assad-García, J.S.; Chu-Ky, S.; Tollot, M.; Guzzo, J.; Gresti, J.; Tourdot-Maréchal, R. Changes in membrane lipid composition in ethanol- and acid-adapted Oenococcus oeni cells: Characterization of the cfa gene by heterologous complementation. Microbiology 2008, 154, 2611–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poger, D.; Mark, A.E. A ring to rule them all: The effect of cyclopropane fatty acids on the fluidity of lipid bilayers. J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 5487–5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junker, F.; Ramos, J.L. Involvement of the cis/trans isomerase Cti in solvent resistance of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 5693–5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pini, C.V.; Bernal, P.; Godoy, P.; Ramos, J.L.; Segura, A. Cyclopropane fatty acids are involved in organic solvent tolerance but not in acid stress resistance in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. Microb. Biotechnol. 2009, 2, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, L.O. Preferential inhibition of phosphatidyl ethanolamine synthesis in E. coli by alcohols. Can. J. Microbiol. 1977, 23, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Khakbaz, P.; Chen, Y.; Lombardo, J.; Yoon, J.M.; Shanks, J.V.; Klauda, J.B.; Jarboe, L.R. Engineering Escherichia coli membrane phospholipid head distribution improves tolerance and production of biorenewables. Metab. Eng. 2017, 44, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkart, H.C.; White, D.C. Phospholipid biosynthesis and solvent tolerance in Pseudomonas putida strains. J. Bacteriol. 1997, 179, 4219–4226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.L.; Duque, E.; Rodríguez-Herva, J.J.; Godoy, P.; Haïdour, A.; Reyes, F.; Fernández-Barrero, A. Mechanisms for solvent tolerance in bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 3887–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, P.; Segura, A.; Ramos, J.L. Compensatory role of the cis-trans-isomerase and cardiolipin synthase in the membrane fluidity of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 1658–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenac, L.; Baidoo, E.E.K. Distinct functional roles for hopanoid composition in the chemical tolerance of Zymomonas mobilis. Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 1564–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, C.; Ryu, S.; Trinh, C.T. Exceptional solvent tolerance in Yarrowia lipolytica is enhanced by sterols. Metab. Eng. 2019, 54, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atsumi, S.; Wu, T.-Y.; Machado, I.M.P.; Huang, W.-C.; Chen, P.-Y.; Pellegrini, M.; Liao, J.C. Evolution, genomic analysis, and reconstruction of isobutanol tolerance in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicolaou, S.A.; Gaida, S.M.; Papoutsakis, E.T. Exploring the combinatorial genomic space in Escherichia coli for ethanol tolerance. Biotechnol. J. 2012, 7, 1337–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Bi, C.; Nicolaou, S.A.; Zingaro, K.A.; Ralston, M.; Papoutsakis, E.T. Overexpression of the Lactobacillus plantarum peptidoglycan biosynthesis murA2 gene increases the tolerance of Escherichia coli to alcohols and enhances ethanol production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 8399–8411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bokhorst-van de Veen, H.; Abee, T.; Tempelaars, M.; Bron, P.A.; Kleerebezem, M.; Marco, M.L. Short- and long-term adaptation to ethanol stress and its cross-protective consequences in Lactobacillus plantarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 5247–5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udom, N.; Chansongkrow, P.; Charoensawan, V.; Auesukaree, C. Coordination of the cell wall integrity and highosmolarity glycerol pathways in response to ethanol stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, T.C.R.; Williams, T.C.; Schulz, B.L.; Palfreyman, R.W.; Krömer, J.O.; Nielsen, L.K. Evolutionary engineering improves tolerance for replacement jet fuels in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3316–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.; Tao, H.; Purvis, J.E.; York, S.W.; Shanmugam, K.T.; Ingram, L.O. Gene array-based identification of changes that contribute to ethanol tolerance in ethanologenic Escherichia coli: Comparison of KO11 (parent) to LY01 (resistant mutant). Biotechnol. Prog. 2003, 19, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, L.H.; Almario, M.P.; Winkler, J.; Orozco, M.M.; Kao, K.C. Visualizing evolution in real time to determine the molecular mechanisms of n -butanol tolerance in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2012, 14, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodruff, L.B.A.; Pandhal, J.; Ow, S.Y.; Karimpour-Fard, A.; Weiss, S.J.; Wright, P.C.; Gill, R.T. Genome-scale identification and characterization of ethanol tolerance genes in Escherichia coli. Metab. Eng. 2013, 15, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinkart, H.C.; Wolfram, J.W.; Rogers, R.; White, D.C. Cell envelope changes in solvent-tolerant and solvent-sensitive Pseudomonas putida strains following exposure to o-xylene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 1129–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asako, H.; Nakajima, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Aono, R. Organic solvent tolerance and antibiotic resistance increased by overexpression of marA in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 1428–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgarten, T.; Sperling, S.; Seifert, J.; von Bergen, M.; Steiniger, F.; Wick, L.Y.; Heipieper, H.J. Membrane vesicle formation as a multiple-stress response mechanism enhances Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E cell surface hydrophobicity and biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 6217–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberlein, C.; Baumgarten, T.; Starke, S.; Heipieper, H.J. Immediate response mechanisms of Gram-negative solvent-tolerant bacteria to cope with environmental stress: Cis-trans isomerization of unsaturated fatty acids and outer membrane vesicle secretion. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 2583–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koebnik, R.; Locher, K.P.; Van Gelder, P. Structure and function of bacterial outer membrane proteins: Barrels in a nutshell. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 37, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, U.; Lee, C.R. Distinct Roles of Outer Membrane Porins in Antibiotic Resistance and Membrane Integrity in Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.F.; Ye, J.Z.; Dai, H.H.; Lin, X.M.; Li, H.; Peng, X. Identification of ethanol tolerant outer membrane proteome reveals OmpC- dependent mechanism in a manner of EnvZ/OmpR regulation in Escherichia coli. J. Proteom. 2018, 179, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Komatsu, T.; Inoue, A.; Horikoshi, K. A Toluene-Tolerant Mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lacking the Outer Membrane Protein F. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1995, 59, 2358–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, J.L.; Jensen, H.M.; Dahl, R.H.; George, K.; Keasling, J.D.; Lee, T.S.; Leong, S.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Improving Microbial Biogasoline Production in Escherichia coli Using Tolerance Engineering. mBio 2014, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Liu, L.Z. Quantitative transcription dynamic analysis reveals candidate genes and key regulators for ethanol tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Tapia, E.; Nana, R.K.; Querol, A.; Pérez-Torrado, R. Ethanol cellular defense induce unfolded protein response in yeast. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Ramos, D.; Van Den Broek, M.; Van Maris, A.J.A.; Pronk, J.T.; Daran, J.M.G. Genome-scale analyses of butanol tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveal an essential role of protein degradation. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Ohtsu, I.; Fujimura, M.; Fukumori, F. A mutation in dnaK causes stabilization of the heat shock sigma factor σ32, accumulation of heat shock proteins and increase in toluene-resistance in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 13, 2007–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zingaro, K.A.; Papoutsakis, E.T. Toward a Semisynthetic Stress Response System To Engineer Microbial Solvent Tolerance. mBio 2012, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingaro, K.A.; Papoutsakis, E.T. GroESL overexpression imparts Escherichia coli tolerance to i-, n-, and 2-butanol, 1,2,4-butanetriol and ethanol with complex and unpredictable patterns. Metab. Eng. 2013, 15, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandvalet, C.; Coucheney, F.; Beltramo, C.; Guzzo, J. CtsR is the master regulator of stress response gene expression in Oenococcus oeni. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 5614–5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, M.G.; Di Tomaso, K.; Calabrone, L.; Salzano, G. Ethanol stress in Oenococcus oeni: Transcriptional response and complex physiological mechanisms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2018, 125, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.S.; Dragovic, Z.; Schirrmacher, G.; Lütke-Eversloh, T. Over-expression of stress protein-encoding genes helps Clostridium acetobutylicum to rapidly adapt to butanol stress. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 34, 1643–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingaro, K.A.; Nicolaou, S.A.; Yuan, Y.; Papoutsakis, E.T. Exploring the heterologous genomic space for building, stepwise, complex, multicomponent tolerance to toxic chemicals. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014, 3, 476–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, C.P.; Juroszek, J.-R.; Beavan, M.J.; Ruby, F.M.S.; De Morais, S.M.F.; Rose, A.H. Ethanol Dissipates the Proton-motive Force across the Plasma Membrane. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1986, 132, 369–377. [Google Scholar]

- Si, H.M.; Zhang, F.; Wu, A.N.; Han, R.Z.; Xu, G.C.; Ni, Y. DNA microarray of global transcription factor mutant reveals membrane-related proteins involved in n-butanol tolerance in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2016, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexandre, H.; Ansanay-Galeote, V.; Dequin, S.; Blondin, B. Global gene expression during short-term ethanol stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2001, 498, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkers, R.J.M.; Snoek, L.B.; Ruijssenaars, H.J.; De Winde, J.H. Dynamic response of Pseudomonas putida S12 to sudden addition of toluene and the potential role of the solvent tolerance gene trgI. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, L.H.; Almario, M.P.; Kao, K.C. Genomic Library Screens for Genes Involved in n-Butanol Tolerance in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, B.J.; Dahl, R.H.; Price, R.E.; Szmidt, H.L.; Benke, P.I.; Mukhopadhyay, A.; Keasling, J.D. Functional genomic study of exogenous n-butanol stress in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura, A.; Godoy, P.; Van Dillewijn, P.; Hurtado, A.; Arroyo, N.; Santacruz, S.; Ramos, J.L. Proteomic analysis reveals the participation of energy- and stress-related proteins in the response of Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E to toluene. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 5937–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, C.A.; Beamish, J.; Papoutsakis, E.T. Transcriptional Analysis of Butanol Stress and Tolerance in Clostridium acetobutylicum. J. Bacteriol. 2004, 186, 2006–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkers, R.J.M.; Ballerstedt, H.; Ruijssenaars, H.; De Bont, J.A.M.; De Winde, J.H.; Wery, J. TrgI, toluene repressed gene I, a novel gene involved in toluene-tolerance in Pseudomonas putida S12. Extremophiles 2009, 13, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lam, F.H.; Ghaderi, A.; Fink, G.R.; Stephanopoulos, G. Engineering alcohol tolerance in yeast. Science 2014, 346, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, A.; Fraser, S.; Chambers, P.J.; Stanley, G.A. Trehalose promotes the survival of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during lethal ethanol stress, but does not influence growth under sublethal ethanol stress. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009, 9, 1208–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, K.; Kitano, H.; Mizoguchi, H.; Hara, S. Effect of cellular inositol content on ethanol tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in sake brewing. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2004, 98, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.E.; Lee, K.S.; Yu, B.J.; Sung, Y.J.; Park, S.M.; Koo, H.M.; Kweon, D.H.; Park, J.C.; Jin, Y.S. Identification of gene targets eliciting improved alcohol tolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through inverse metabolic engineering. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 149, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansure, J.J.C.; Panek, A.D.; Crowe, L.M.; Crowe, J.H. Trehalose inhibits ethanol effects on intact yeast cells and liposomes. BBA Biomembr. 1994, 1191, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simola, M.; Hänninen, A.L.; Stranius, S.M.; Makarow, M. Trehalose is required for conformational repair of heat-denatured proteins in the yeast endoplasmic reticulum but not for maintenance of membrane traffic functions after severe heat stress. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 37, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Tian, J.; Ji, Z.H.; Song, M.Y.; Li, H. Intracellular metabolic changes of Clostridium acetobutylicum and promotion to butanol tolerance during biobutanol fermentation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 78, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horinouchi, T.; Tamaoka, K.; Furusawa, C.; Ono, N.; Suzuki, S.; Hirasawa, T.; Yomo, T.; Shimizu, H. Transcriptome analysis of parallel-evolved Escherichia coli strains under ethanol stress. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okochi, M.; Kurimoto, M.; Shimizu, K.; Honda, H. Increase of organic solvent tolerance by overexpression of manXYZ in Escherichia coli. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 73, 1394–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Du, Z.; Zhu, H.; Guo, X.; He, X. Protective Effects of Arginine on Saccharomyces cerevisiae Against Ethanol Stress. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodarzi, H.; Bennett, B.D.; Amini, S.; Reaves, M.L.; Hottes, A.K.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Tavazoie, S. Regulatory and metabolic rewiring during laboratory evolution of ethanol tolerance in E. coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2010, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.D.; Guss, A.M.; Karpinets, T.V.; Parks, J.M.; Smolin, N.; Yang, S.; Land, M.L.; Klingeman, D.M.; Bhandiwad, A.; Rodriguez, M.; et al. Mutant alcohol dehydrogenase leads to improved ethanol tolerance in Clostridium thermocellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 13752–13757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Cervenka, N.D.; Low, A.M.; Olson, D.G.; Lynd, L.R. A mutation in the AdhE alcohol dehydrogenase of Clostridium thermocellum increases tolerance to several primary alcohols, including isobutanol, n-butanol and ethanol. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosqueda, G.; Ramos-González, M.I.; Ramos, J.L. Toluene metabolism by the solvent-tolerant Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1 strain, and its role in solvent impermeabilization. Gene 1999, 232, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogales, J.; García, J.L.; Díaz, E. Degradation of Aromatic Compounds in Pseudomonas: A Systems Biology View. In Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology, 1st ed.; Timmis, K.N., McGenity, T.J., van der Meer, J.R., de Lorenzo, V., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 1, p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Brochado, A.R.; Patil, K.R. Overexpression of O-methyltransferase leads to improved vanillin production in baker’s yeast only when complemented with model-guided network engineering. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2013, 110, 656–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, E.H.; Møller, B.L.; Kock, G.R.; Bünner, C.M.; Kristensen, C.; Jensen, O.R.; Okkels, F.T.; Olsen, C.E.; Motawia, M.S.; Hansen, J. De Novo Biosynthesis of Vanillin in Fission Yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) and Baker’s Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 2765–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strucko, T.; Magdenoska, O.; Mortensen, U.H. Benchmarking two commonly used Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains for heterologous vanillin-β-glucoside production. Metab. Eng. Commun. 2015, 2, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Terán, F.; Perez-Amador, I.; López-Munguia, A. Enzymatic extraction and transformation of glucovanillin to vanillin from vanilla green pods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 5207–5209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isken, S.; Santos, P.M.A.C.; De Bont, J.A.M. Effect of solvent adaptation on the antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas putida S12. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1997, 48, 642–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oethinger, M.; Kern, W.V.; Goldman, J.D.; Levy, S.B. Association of organic solvent tolerance and fluoroquinolone resistance in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1998, 41, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, N.; Jing, D.; Kuroda, K.; Ueda, M. Activation of signaling pathways related to cell wall integrity and multidrug resistance by organic solvent in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 2014, 60, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, V.; Lister, I.M. MarA, SoxS and Rob of Escherichia coli—Global regulators of multidrug resistance, virulence and stress response. Int. J. Biotechnol. Wellness Ind. 2014, 2, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aono, R.; Tsukagoshi, N.; Yamamoto, M. Involvement of Outer Membrane Protein TolC, a Possible Member of the mar-sox Regulon, in Maintenance and Improvement of Organic Solvent Tolerance of Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Negishi, T.; Aono, R. soxRS Gene Increased the Level of Organic Solvent Tolerance in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1995, 59, 1323–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Asako, H.; Aono, R. Overexpression of the robA Gene Increases Organic Solvent Tolerance and Multiple Antibiotic and Heavy Metal Ion Resistance in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 2302–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, R.; Doukyu, N. Improvement of organic solvent tolerance by disruption of the lon gene in Escherichia coli. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2014, 118, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duque, E.; Segura, A.; Mosqueda, G.; Ramos, J.L. Global and cognate regulators control the expression of the organic solvent efflux pumps TtgABC and TtgDEF of Pseudomonas putida. Mol. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Z.; Zhang, L.; Poole, K. Role of the multidrug efflux systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in organic solvent tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 2987–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosqueda, G.; Ramos, J.L. A Set of Genes Encoding a Second Toluene Efflux System in Pseudomonas putida DOT-T1E Is Linked to the tod Genes for Toluene Metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, M.J.; Dossani, Z.Y.; Szmidt, H.L.; Chu, H.C.; Lee, T.S.; Keasling, J.D.; Hadi, M.Z.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Engineering microbial biofuel tolerance and export using efflux pumps. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.-X.; He, X.; Wu, Y.-Q.; Liu, J.-Z. Enhancing Production of Pinene in Escherichia coli by Using a Combination of Tolerance, Evolution, and Modular Co-culture Engineering. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Stephanopoulos, G.; Too, H.P. Efflux transporter engineering markedly improves amorphadiene production in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2016, 113, 1755–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, G.; Thompson, M.; Tullman-Ercek, D.; Keasling, J. A Pseudomonas putida efflux pump acts on short-chain alcohols. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2018, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.M.; Woo, J.M.; Lee, S.M.; Park, J.B. Improving ethanol tolerance of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by overexpressing an ATP-binding cassette efflux pump. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 103, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankarloo, J.; Wikman, S.; Nicholls, I.A. Escherichia coli mar and acrAB mutants display no tolerance to simple alcohols. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11, 1403–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, M.A.; Boyarskiy, S.; Yamada, M.R.; Kong, N.; Bauer, S.; Tullman-Ercek, D. Enhancing tolerance to short-chain alcohols by engineering the Escherichia coli AcrB efflux pump to secrete the non-native substrate n-butanol. Acs Synth. Biol. 2014, 3, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Yang, L.; Shah, A.A.; Choi, E.; Kim, S. Dynamic interplay of multidrug transporters with TolC for isoprenol tolerance in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2015, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Yoo, J.S.; Jeong, Y.K.; Joo, W.H. Involvement of antioxidant defense system in solvent tolerance of Pseudomonas putida BCNU 106. J. Basic Microbiol. 2014, 54, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margalef-Català, M.; Felis, G.E.; Reguant, C.; Stefanelli, E.; Torriani, S.; Bordons, A. Identification of variable genomic regions related to stress response in Oenococcus oeni. Food Res. Int. 2017, 102, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyrina, A.N.; Smirnova, E.A.; Markova, O.V.; Severin, F.F.; Knorre, D.A. Mitochondrial Superoxide Dismutase and Yap1p Act as a Signaling Module Contributing to Ethanol Tolerance of the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.C.; Lin, K.H.; Chang, J.J.; Huang, C.C. Improvement of n-butanol tolerance in Escherichia coli by membrane-targeted tilapia metallothionein. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2013, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Hindorff, L.A.; Chuang, A.; Monroe-Augustus, M.; Lyristis, M.; Harrison, M.L.; Rudolph, F.B.; Bennett, G.N. Expression of a cloned cyclopropane fatty acid synthase gene reduces solvent formation in Clostridium acetobutylicum ATCC 824. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 2831–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yomano, L.P.; York, S.W.; Ingram, L.O. Isolation and characterization of ethanol-tolerant mutants of Escherichia coli KO11 for fuel ethanol production. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1998, 20, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thammasittirong, S.N.R.; Thirasaktana, T.; Thammasittirong, A.; Srisodsuk, M. Improvement of ethanol production by ethanoltolerant Saccharomyces cerevisiae UVNR56. Springerplus 2013, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mo, W.; Wang, M.; Zhan, R.; Yu, Y.; He, Y.; Lu, H. Kluyveromyces marxianus developing ethanol tolerance during adaptive evolution with significant improvements of multiple pathways. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennen, R.; Jensen, K.; Mohammed, E.; Malla, S.; Börner, R.; Chekina, K.; Özdemir, E.; Bonde, I.; Koza, A.; Maury, J.; et al. Adaptive laboratory evolution reveals general and specific chemical tolerance mechanisms and enhances biochemical production. bioRxiv 2019, 19, 634105. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T.; Watanabe, I.; Yamamoto, M.; Ando, A.; Nakamura, T. A UV-induced mutant of Pichia stipitis with increased ethanol production from xylose and selection of a spontaneous mutant with increased ethanol tolerance. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 1844–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betteridge, A.L.; Sumby, K.M.; Sundstrom, J.F.; Grbin, P.R.; Jiranek, V. Application of directed evolution to develop ethanol tolerant Oenococcus oeni for more efficient malolactic fermentation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 921–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, M.H.; Calero, P.; Lennen, R.M.; Long, K.S.; Nielsen, A.T. Genome-wide Escherichia coli stress response and improved tolerance towards industrially relevant chemicals. Microb. Cell Factories 2016, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomas, C.A.; Welker, N.E.; Papoutsakis, E.T. Overexpression of groESL in Clostridium acetobutylicum results in increased solvent production and tolerance, prolonged metabolism, and changes in the cell’s transcriptional program. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 4951–4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Cao, Y.; Liu, W.; Xian, M.; Liu, H. Improving phloroglucinol tolerance and production in Escherichia coli by GroESL overexpression. Microb. Cell Factories 2017, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Wu, B.; Dai, L.; Qin, H.; Shui, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, G. Using global transcription machinery engineering (gTME) to improve ethanol tolerance of Zymomonas mobilis. Microb. Cell Factories 2016, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoek, T.; Picca Nicolino, M.; Van Den Bremt, S.; Mertens, S.; Saels, V.; Verplaetse, A.; Steensels, J.; Verstrepen, K.J. Large-scale robot-assisted genome shuffling yields industrial Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeasts with increased ethanol tolerance. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2015, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jetti, K.D.; Gns, R.R.; Garlapati, D.; Nammi, S.K. Improved ethanol productivity and ethanol tolerance through genome shuffling of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia stipitis. Int. Microbiol. 2019, 22, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Gérando, H.M.; Fayolle-Guichard, F.; Rudant, L.; Millah, S.K.; Monot, F.; Ferreira, N.L.; López-Contreras, A.M. Improving isopropanol tolerance and production of Clostridium beijerinckii DSM 6423 by random mutagenesis and genome shuffling. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 5427–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanza, A.M.; Alper, H.S. Global Strain Engineering by Mutant Transcription Factors. In Strain Engineering: Methods and Protocols, 1st ed.; Williams, J.A., Ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 765, pp. 253–274. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, H.; Geng, H.; Zhang, H.; Song, H.; Huang, L.; Jiang, R. Enhancing E. coli isobutanol tolerance through engineering its global transcription factor cAMP receptor protein (CRP). Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014, 111, 700–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, H.; Stephanopoulos, G. Global transcription machinery engineering: A new approach for improving cellular phenotype. Metab. Eng. 2007, 9, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wassarman, K.M. Small RNAs in bacteria: Diverse regulators of gene expression in response to environmental changes. Cell 2002, 109, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Haning, K.; Gonzalez-Rivera, J.C.; Yang, Y.; Li, R.; Cho, S.H.; Huang, J.; Simonsen, B.A.; Yang, S.; Contreras, L.M. Multiple Small RNAs Interact to Co-regulate Ethanol Tolerance in Zymomonas mobilis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-X.; Perry, K.; Vinci, V.; Powell, K.; Stemmer, W.P.C.; del Cardayré, S.B. Genome shuffling leads to rapid phenotypic improvement in bacteria. Nature 2002, 415, 644–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, X.; Zheng, D.; Liu, T.; Wang, P.; Zhao, W.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, X. A Novel Strategy to Construct Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae Strains for Very High Gravity Fermentation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli (B) | This γ-proteobacterium is by far the most studied (bacterial) model organism. Since E. coli is genetically and metabolically well-characterized, its potential in the production of fuels (alcohols and terpenoids, etc.), organic acids (e.g., hydroxybutyrate), and amino acids has been explored over recent decades. | [16,17] |

| Zymomonas mobilis (B) | Originally, this α-proteobacterium was isolated from tropical, fruit-or agave-based beverages and spoiled ciders. However, its remarkable ethanol tolerance and glucose consumption rate have promoted its use in the ethanol industry. Recently, extensive metabolic engineering resulted in industrial strains which are able to produce ethanol, sorbitol, and levan from lignocellulosic biomass (composed of nonedible sugars). | [18,19,20] |

| Clostridium sp. (B) | C. acetobutylicum and beijerinckii have the natural ability to metabolize sugars into acetone, butanol and ethanol simultaneously. Therefore, these strains have been used for over 100 years to produce this solvent mix on an industrial scale. | [21,22] |

| Corynebacterium glutamicum (B) | This actinobacterium is particularly suitable for the production of amino acids. Recently, researchers have successfully implemented (biogas-based) methanol as a carbon source for this purpose. | [14,23] |

| Lactic Acid Bacteria (B) | This group of bacteria (including Lactobacillus plantarum and Oenococcus oeni) are naturally present in wines. These microorganisms facilitate maturation of (red) wines as they are largely responsible for the conversion of lactate into malate. The latter improves the sensory qualities and ensures that these alcoholic drinks are microbiologically stable (on the long term). As they need to withstand ethanol percentages (>10%), lactic acid bacteria are suitable candidates to study alcohol tolerance. | [24,25] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Y) | This yeast species is without any doubt the most commonly used fermentation strain both in the food and fuel industries. Decades of research on metabolic engineering even expanded the application potential of S. cerevisiae towards lignocellulose-based ethanol production. | [26,27] |

| Kluyveromyces marxianus (Y) | This dairy yeast is traditionally used for the fermentation of milk into yoghurt, kefir, etc. Moreover, the strain has also been industrially exploited for the production of enzymes (e.g., pectinases and lipases). Recently, researchers have also implemented K. marxianus in bioethanol production as this yeast displays high thermotolerance and has a broad sugar utilization range. | [28,29] |

| Scheffersomyces stipitis (Y) | This respiratory yeast is also known as Pichia stipitis. In contrast to S. cerevisiae, S. stipitis naturally utilizes a whole arsenal of (hemi)cellulases to consume complex sugars (e.g., cellobiose). This feature is particularly interesting in lignocellulose-based bioethanol production settings. | [30] |

| Strategy | Solvent | Organism | Production Gain | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive laboratory evolution (ALE) | ethanol | E. coli | +3–16% | [219] |

| S. cerevisiae | +20–35% | [220] | ||

| K. marxianus | +120–730% | [221] | ||

| S. stipitis | +10% | [223] | ||

| butanediol | E. coli | +30–70% | [222] | |

| butanol | C. acetobutylicum | +44% | [12] | |

| methanol | C. glutamicum | +156% | [14] | |

| pinene | E. coli | +31% | [207] | |

| Overexpression of stress-response pathways or detoxification mechanisms | ethanol isopentenol | E. coli | +11–30% | [141] |

| S. cerevisiae | +20% | [210] | ||

| E. coli | +12–60% | [156] | ||

| butanol | C. acetobutylicum | +33–40% | [226] | |

| limonene | E. coli | +65% | [206] | |

| amorphadiene | E. coli | +286–308% | [208] | |

| phloroglucinol | E. coli | +39.5% | [227] | |

| vanillin | S. pombe | +25% | [192] | |

| Global transcription machinery engineering (gTME) | ethanol | S. cerevisiae | +15% | [13] |

| Z. mobilis | +90% | [228] | ||

| styrene | E. coli | +31–245% | [15] | |

| Genome shuffling | ethanol | S. cerevisiae | +2–7% | [229] |

| S. cerevisiae/S. stipitis | +4–14% | [230] | ||

| isopropanol | C. beijerinckii | +15% | [231] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schalck, T.; Bergh, B.V.d.; Michiels, J. Increasing Solvent Tolerance to Improve Microbial Production of Alcohols, Terpenoids and Aromatics. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020249

Schalck T, Bergh BVd, Michiels J. Increasing Solvent Tolerance to Improve Microbial Production of Alcohols, Terpenoids and Aromatics. Microorganisms. 2021; 9(2):249. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020249

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchalck, Thomas, Bram Van den Bergh, and Jan Michiels. 2021. "Increasing Solvent Tolerance to Improve Microbial Production of Alcohols, Terpenoids and Aromatics" Microorganisms 9, no. 2: 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020249

APA StyleSchalck, T., Bergh, B. V. d., & Michiels, J. (2021). Increasing Solvent Tolerance to Improve Microbial Production of Alcohols, Terpenoids and Aromatics. Microorganisms, 9(2), 249. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020249