Research on the Dynamic Behavior of Rotor–Stator Systems Considering Bearing Clearance in Aeroengines

Abstract

1. Introduction

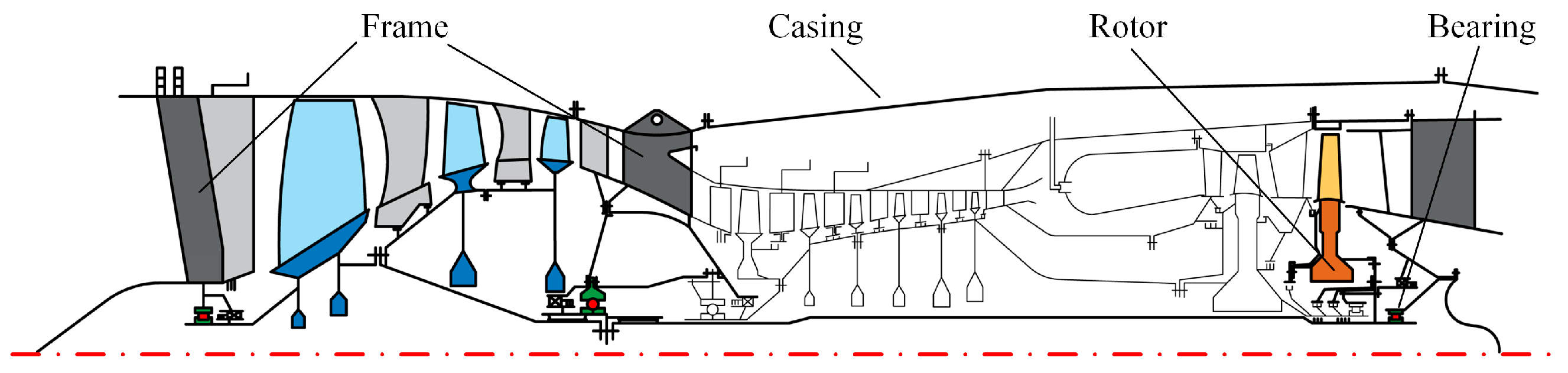

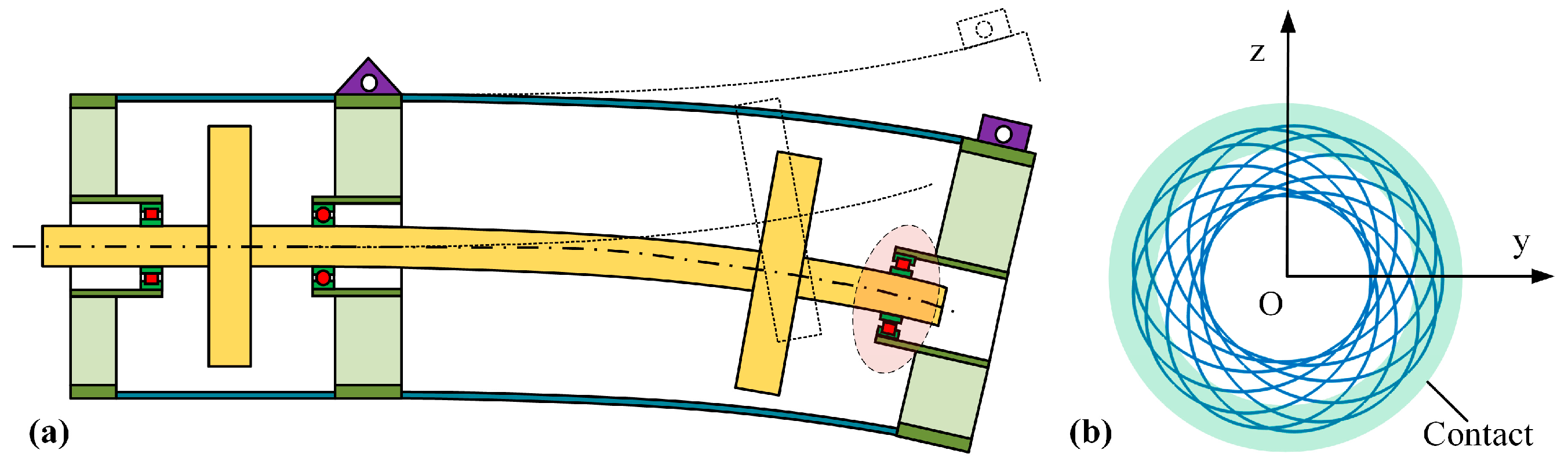

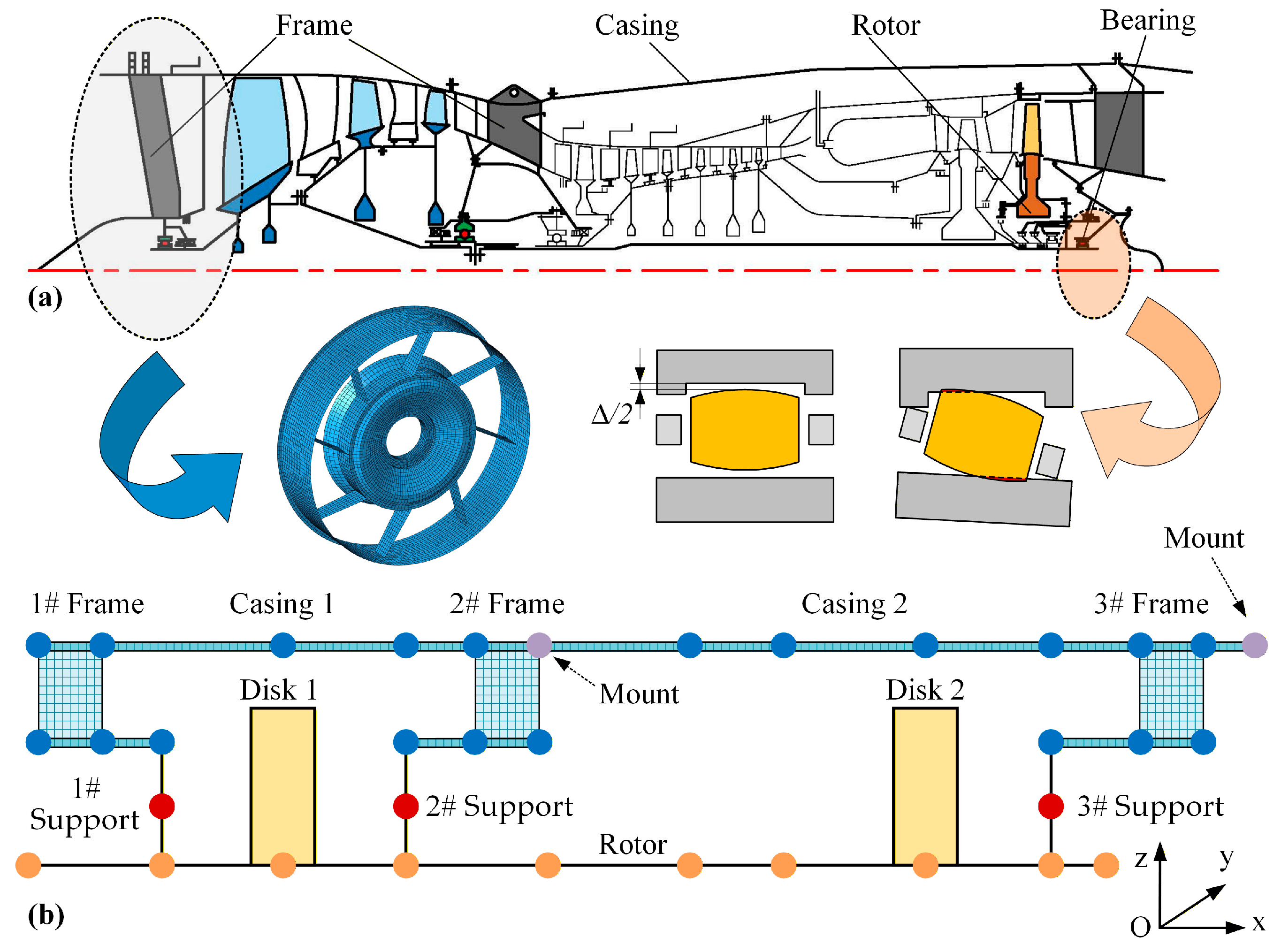

2. The Dynamic Model of the Rotor–Stator System

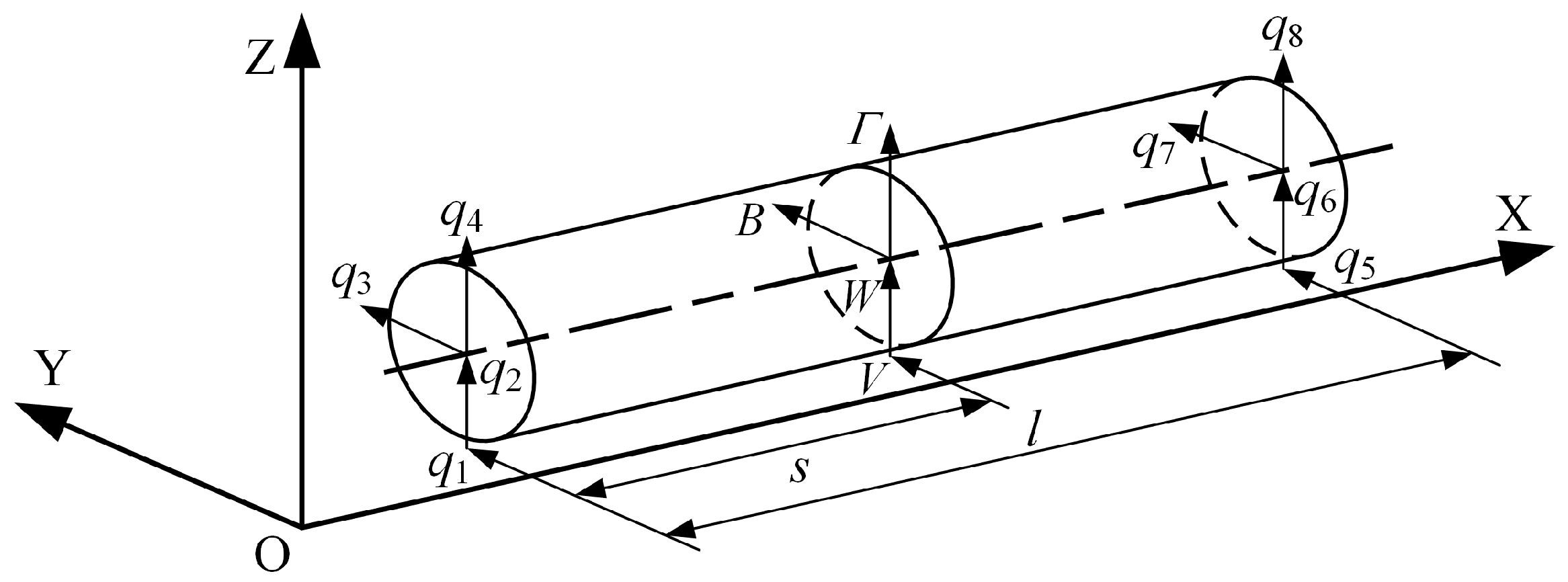

2.1. Rotor Modeling with Beam Element

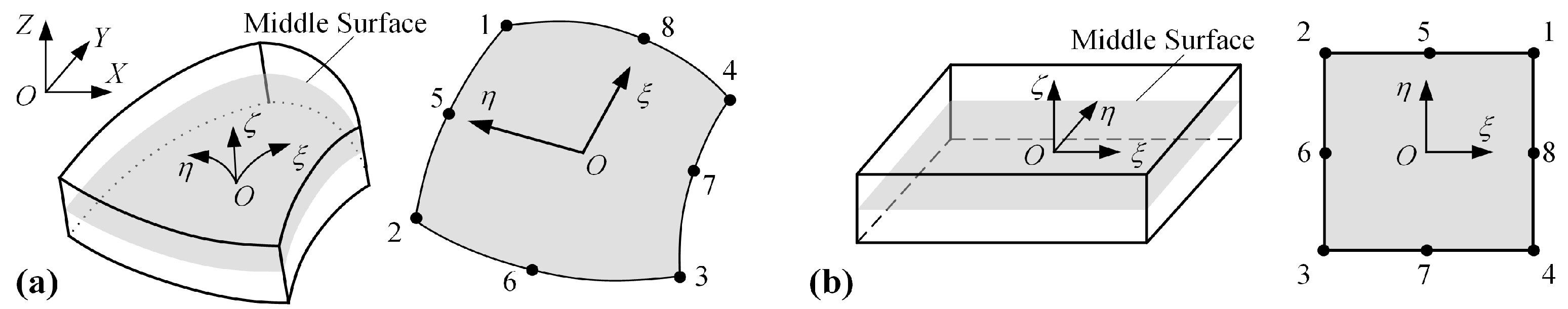

2.2. Stator Model with Shell Element

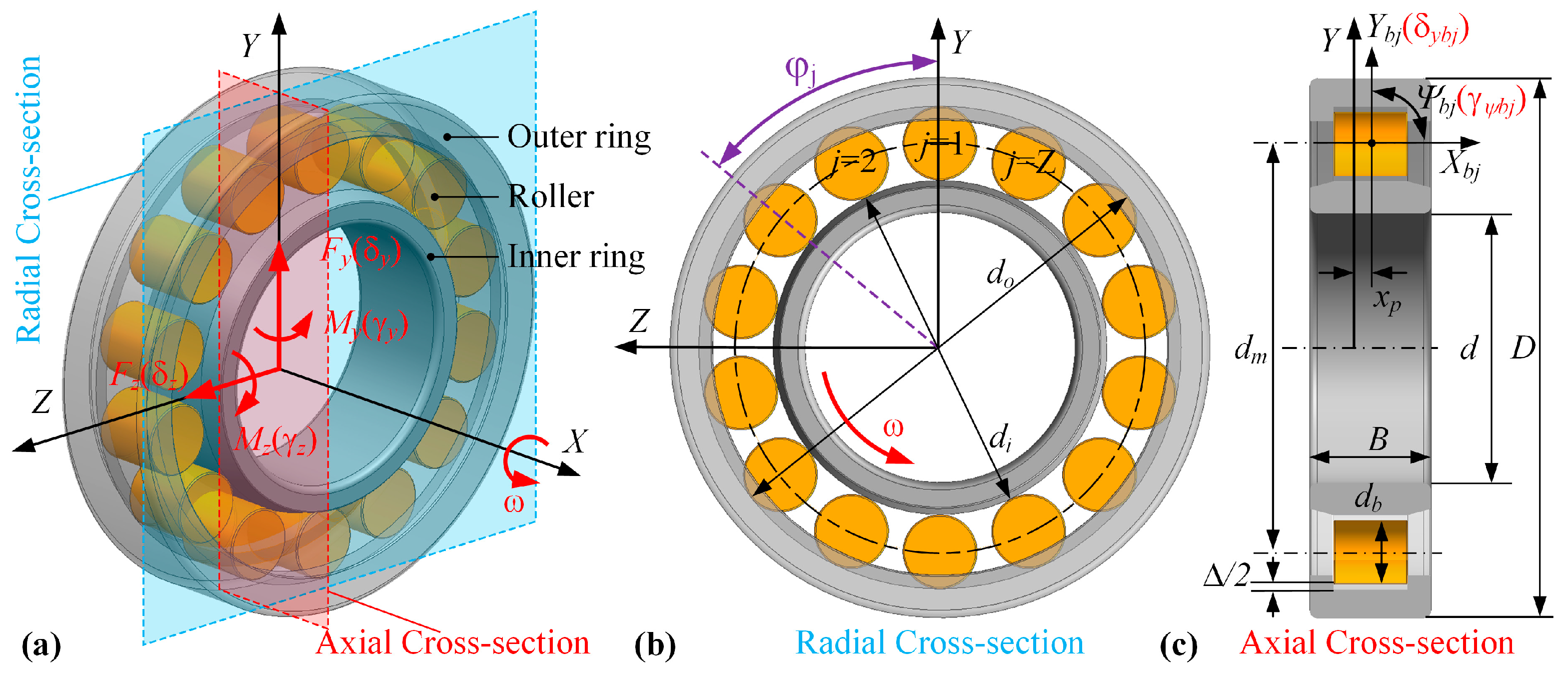

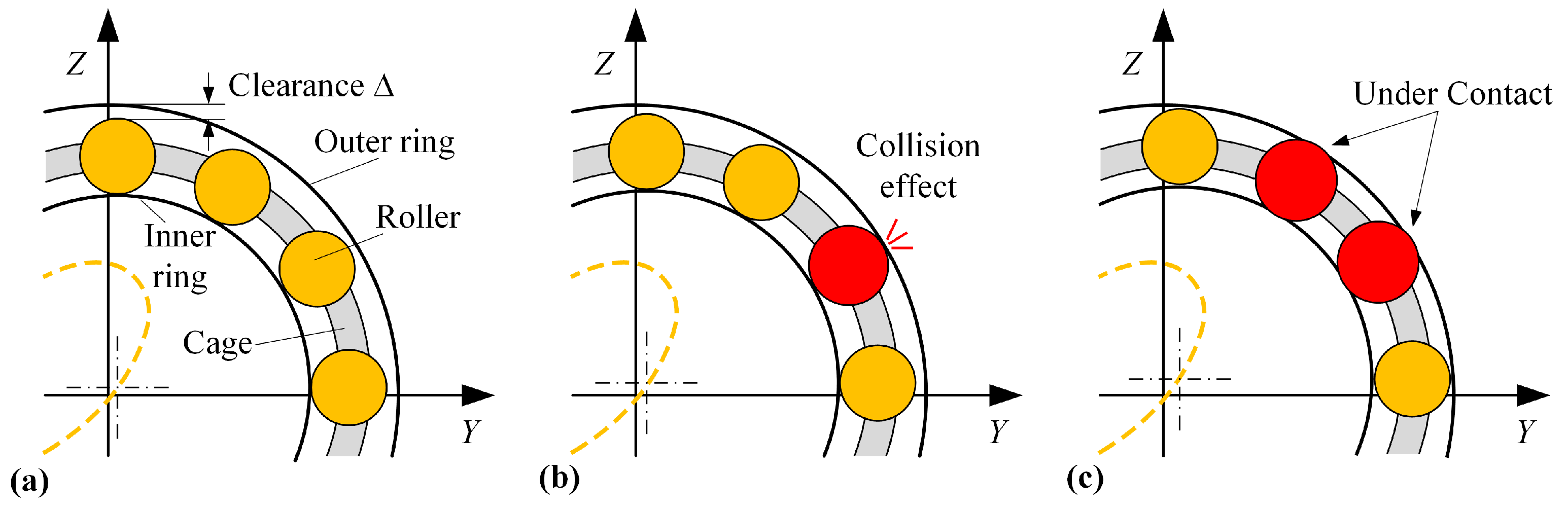

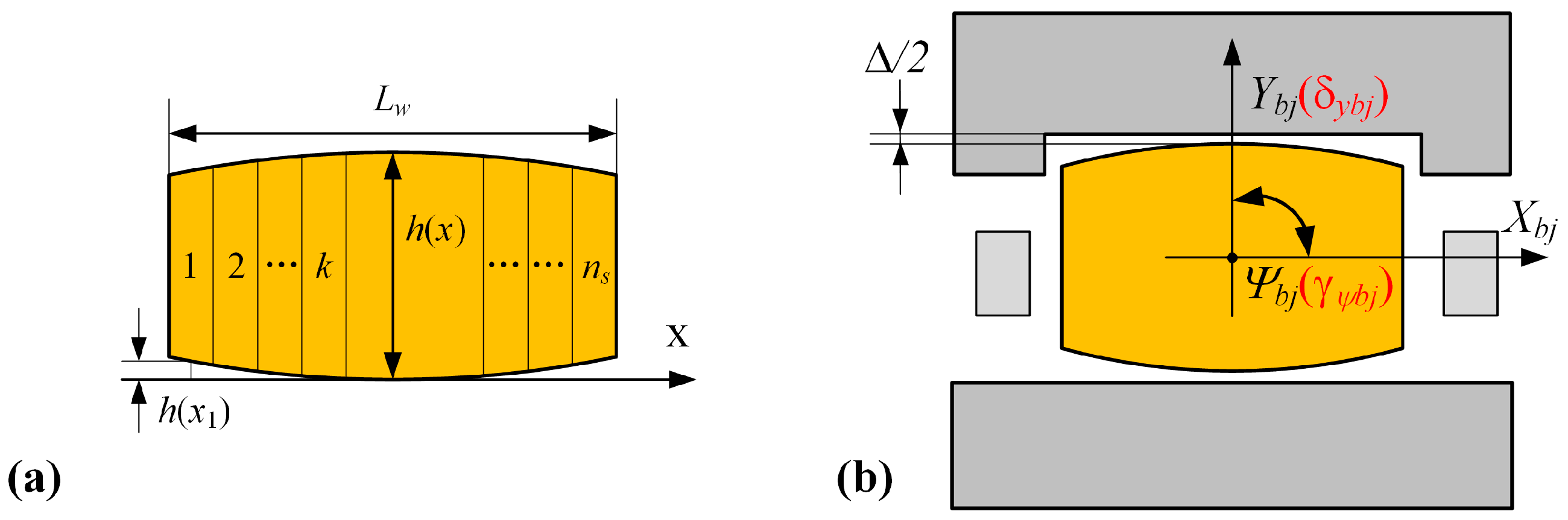

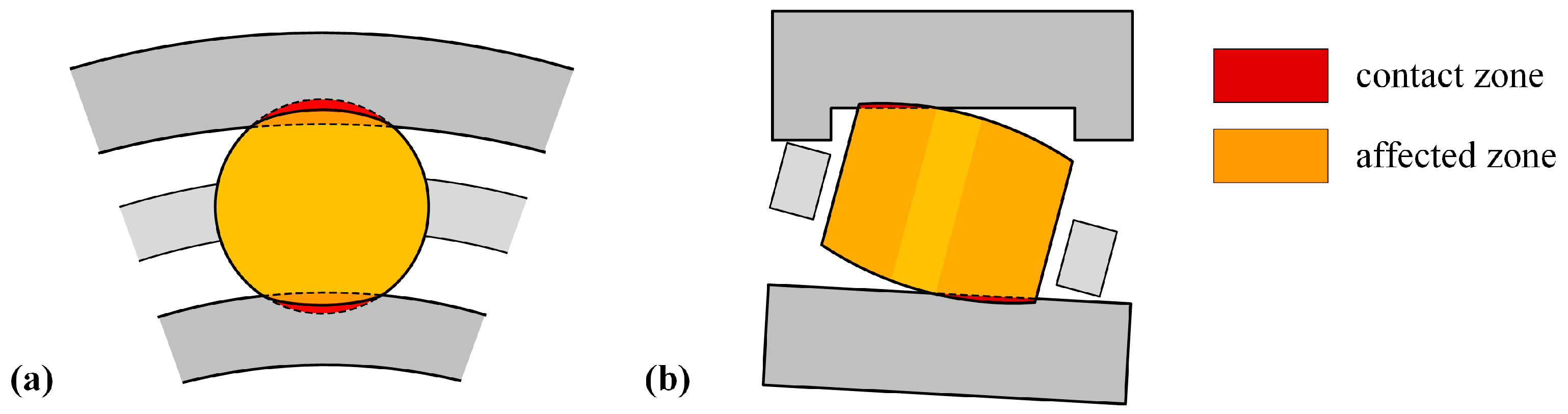

2.3. Quasi-Static Bearing Model

2.4. System Assembly and Equation of Motion

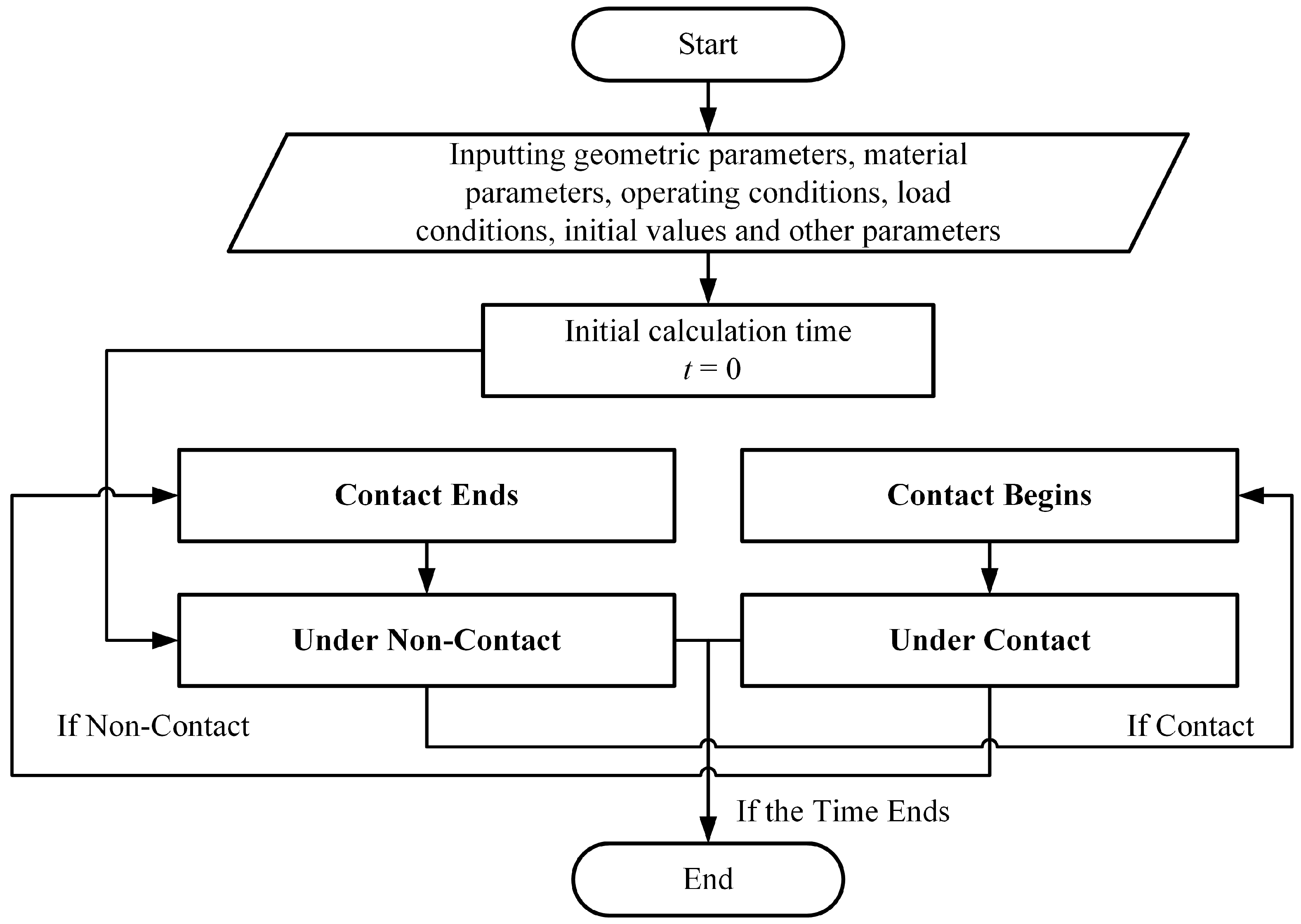

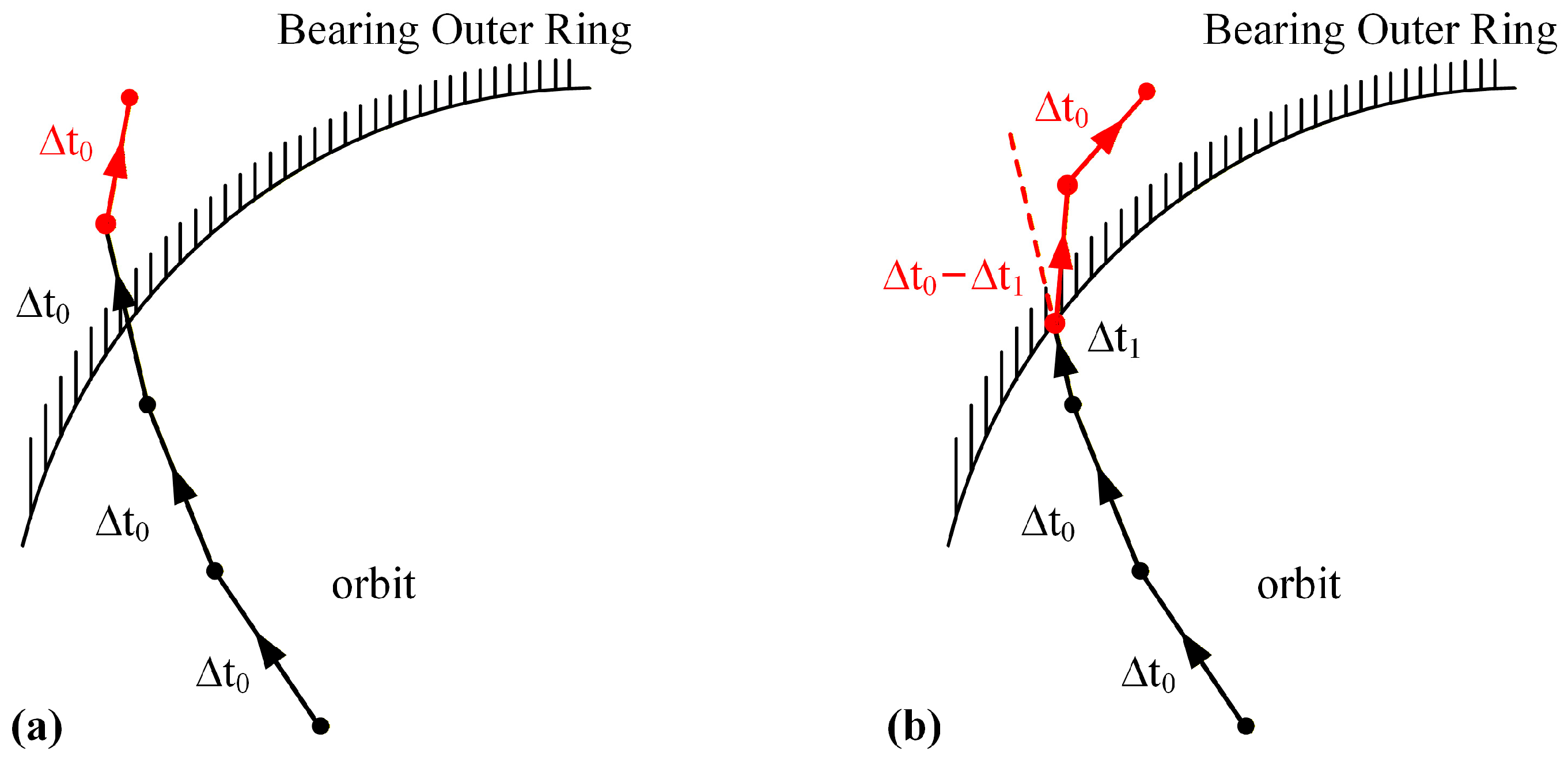

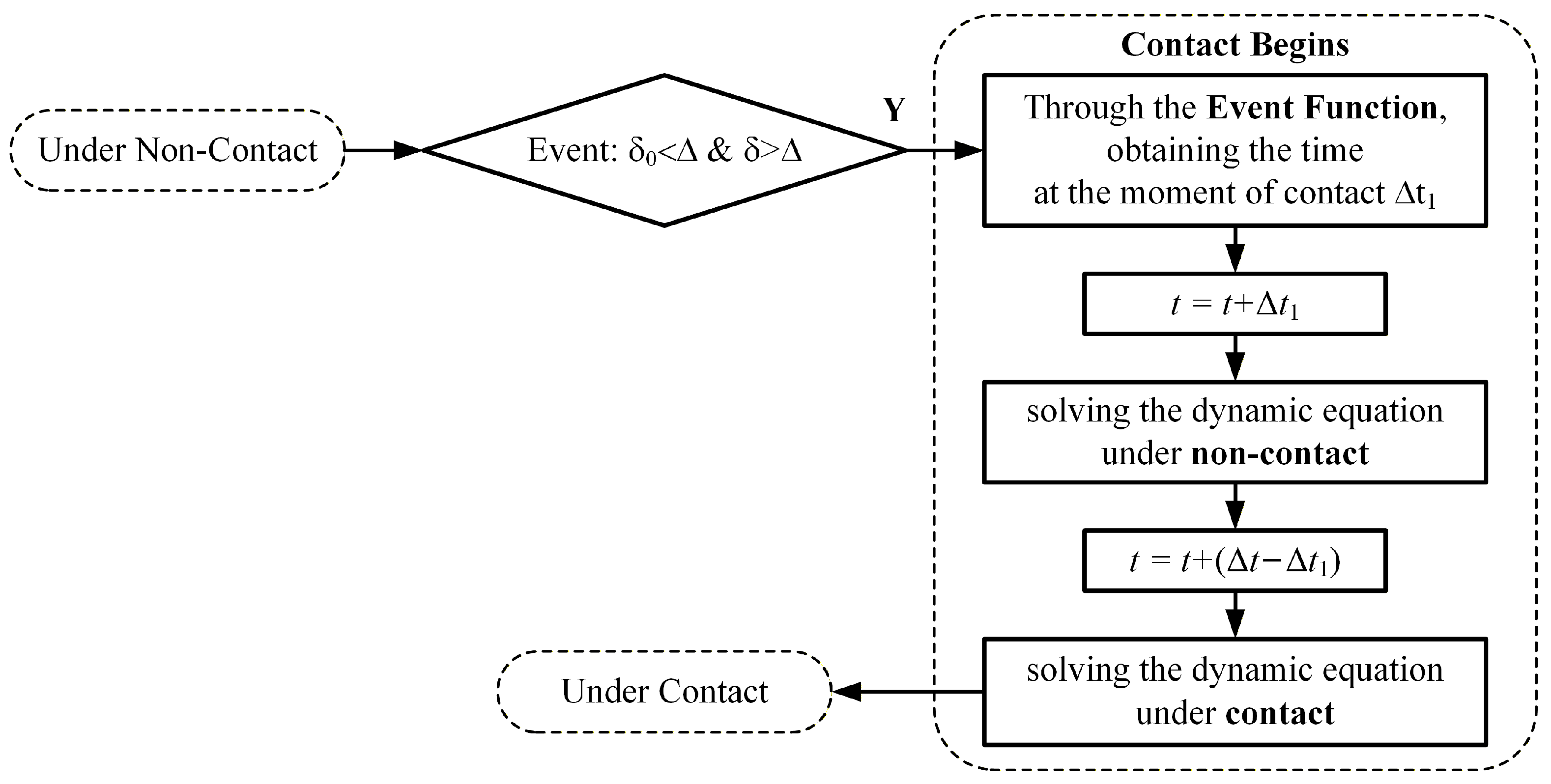

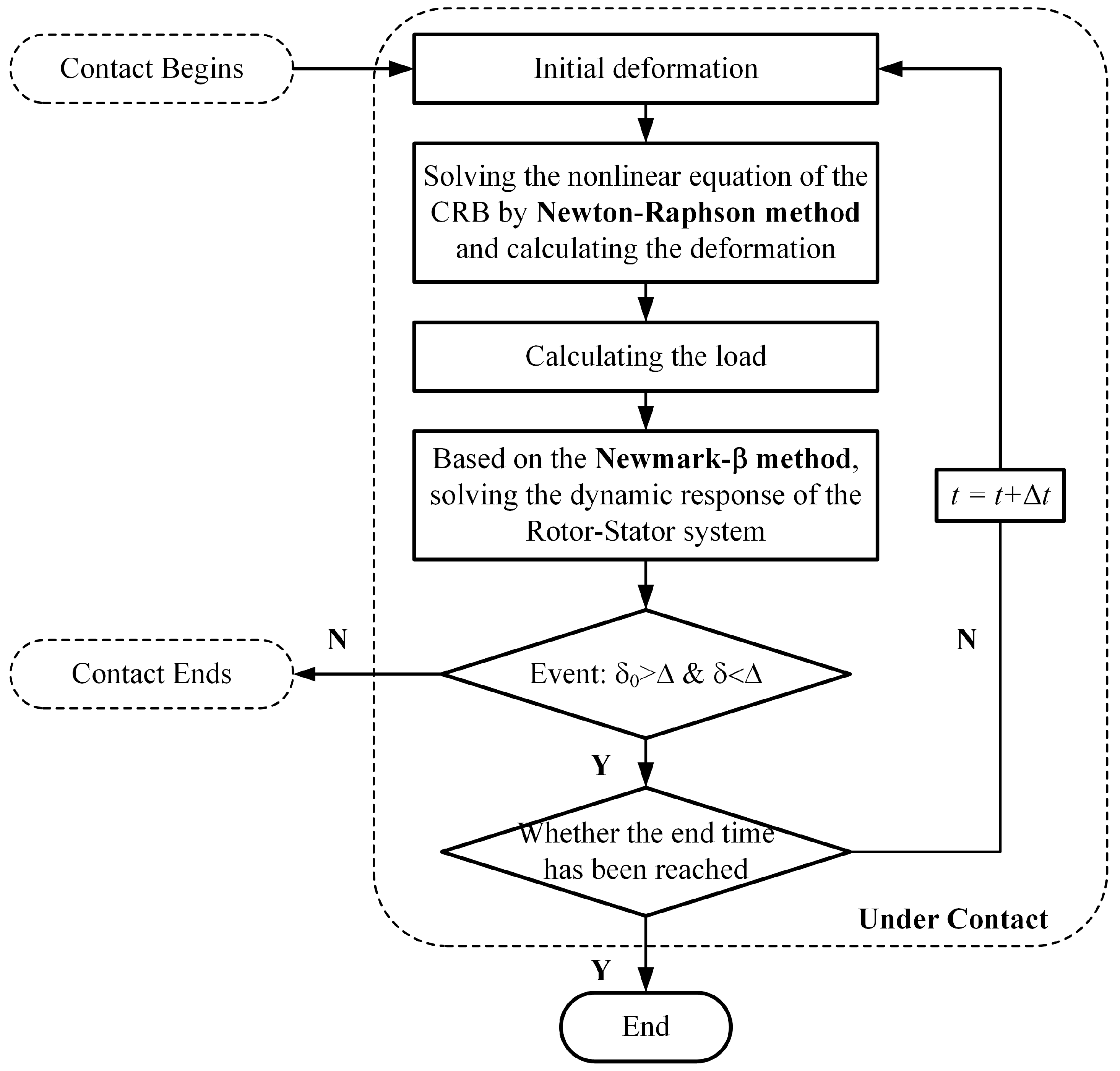

3. Numerical Calculation Method

4. Simulation Analysis

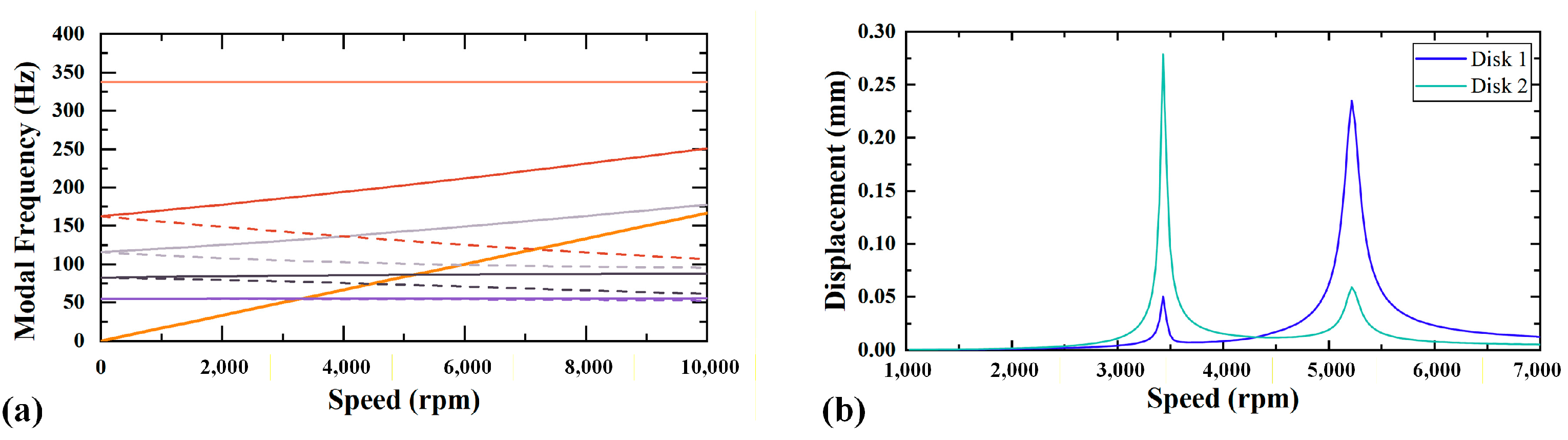

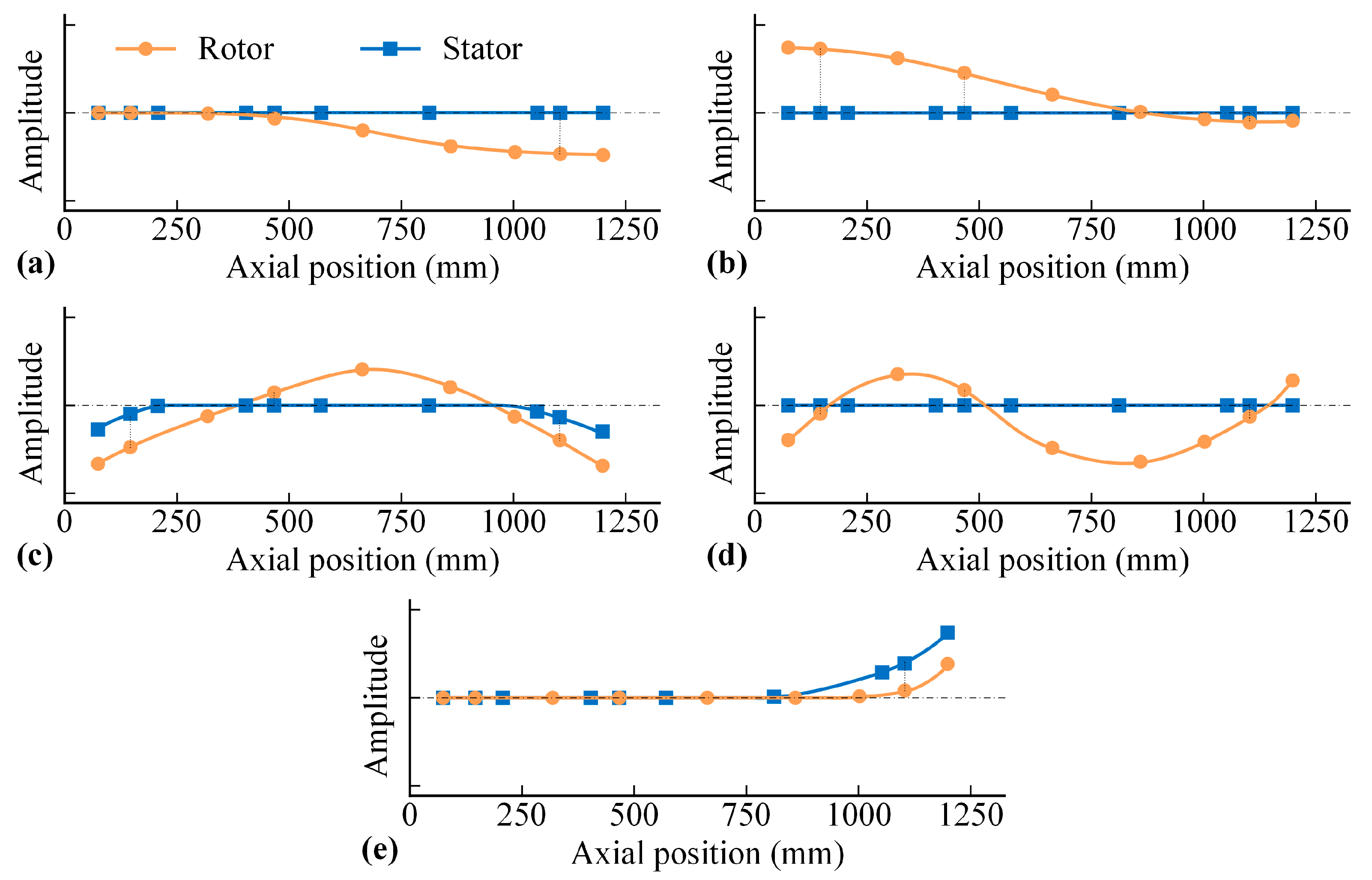

4.1. Dynamic Characteristics of the Rotor–Stator System

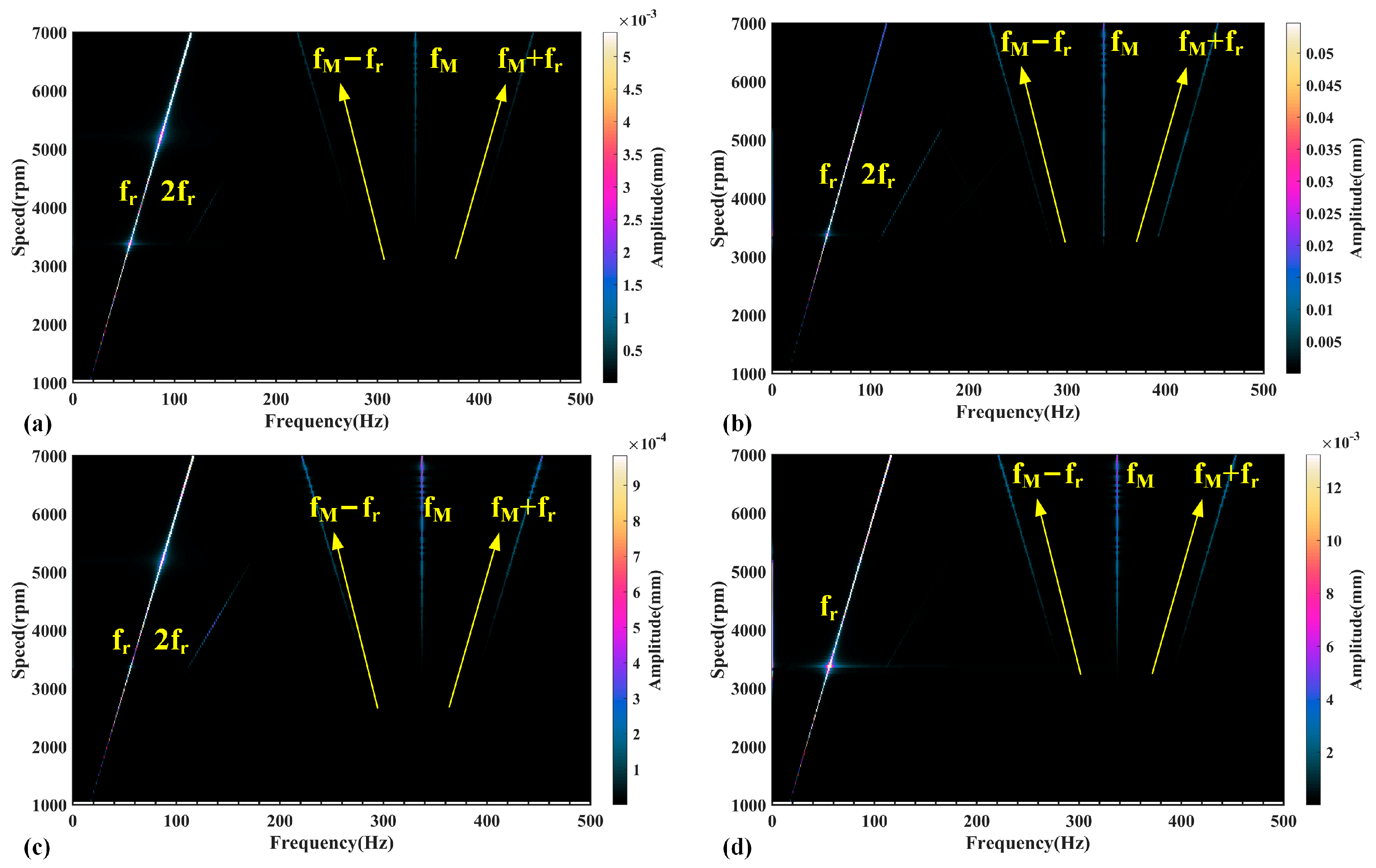

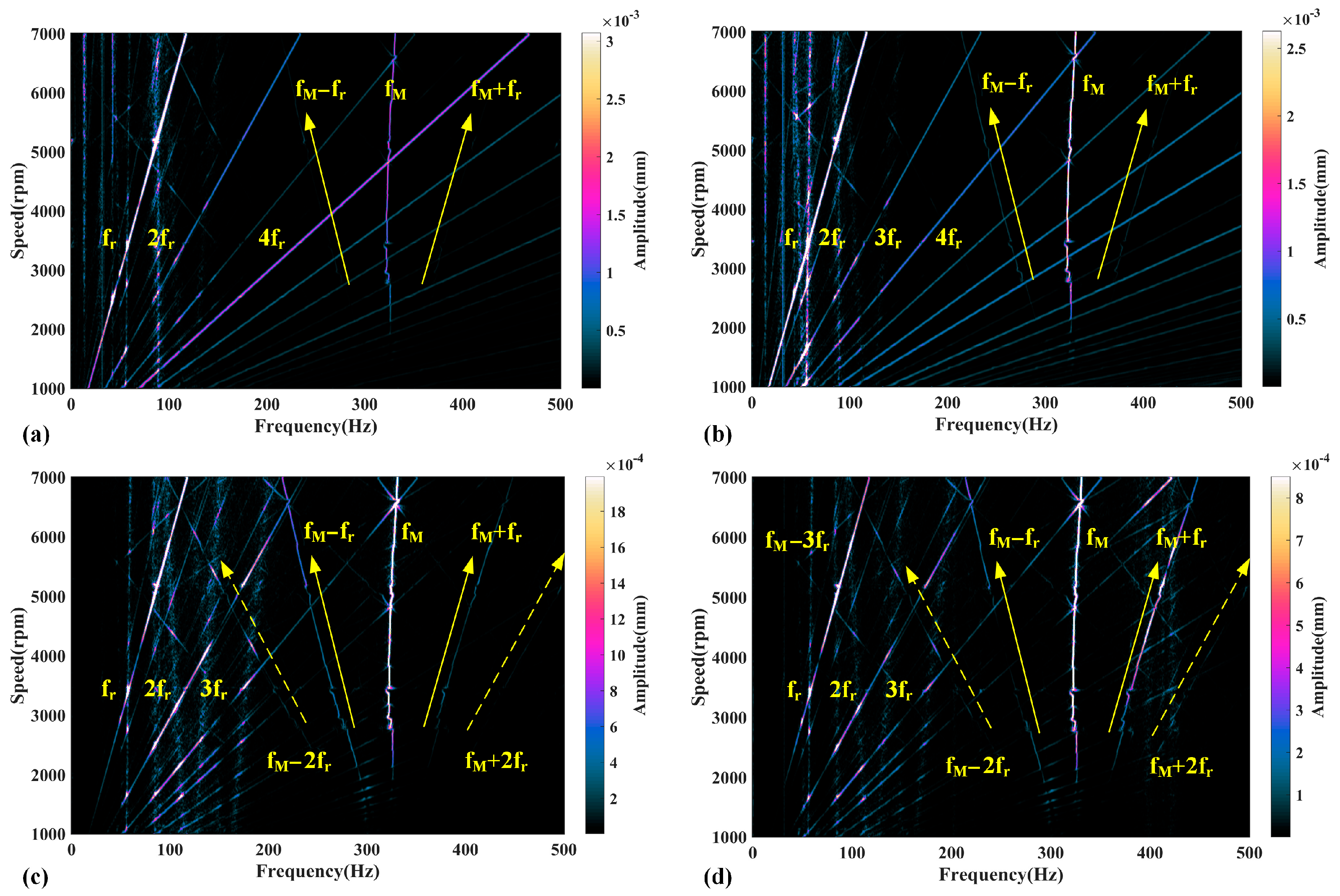

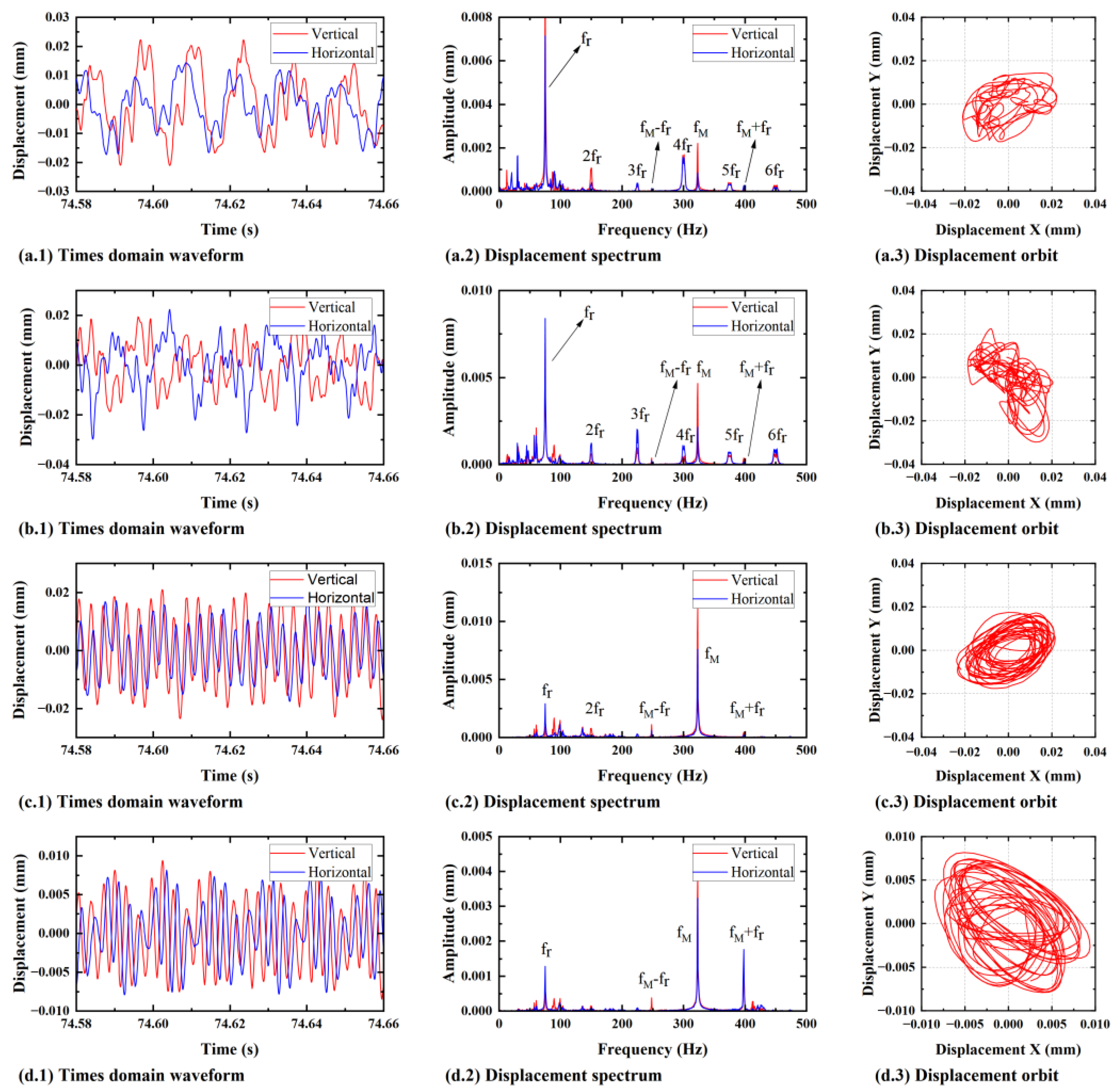

4.2. Results and Discussion

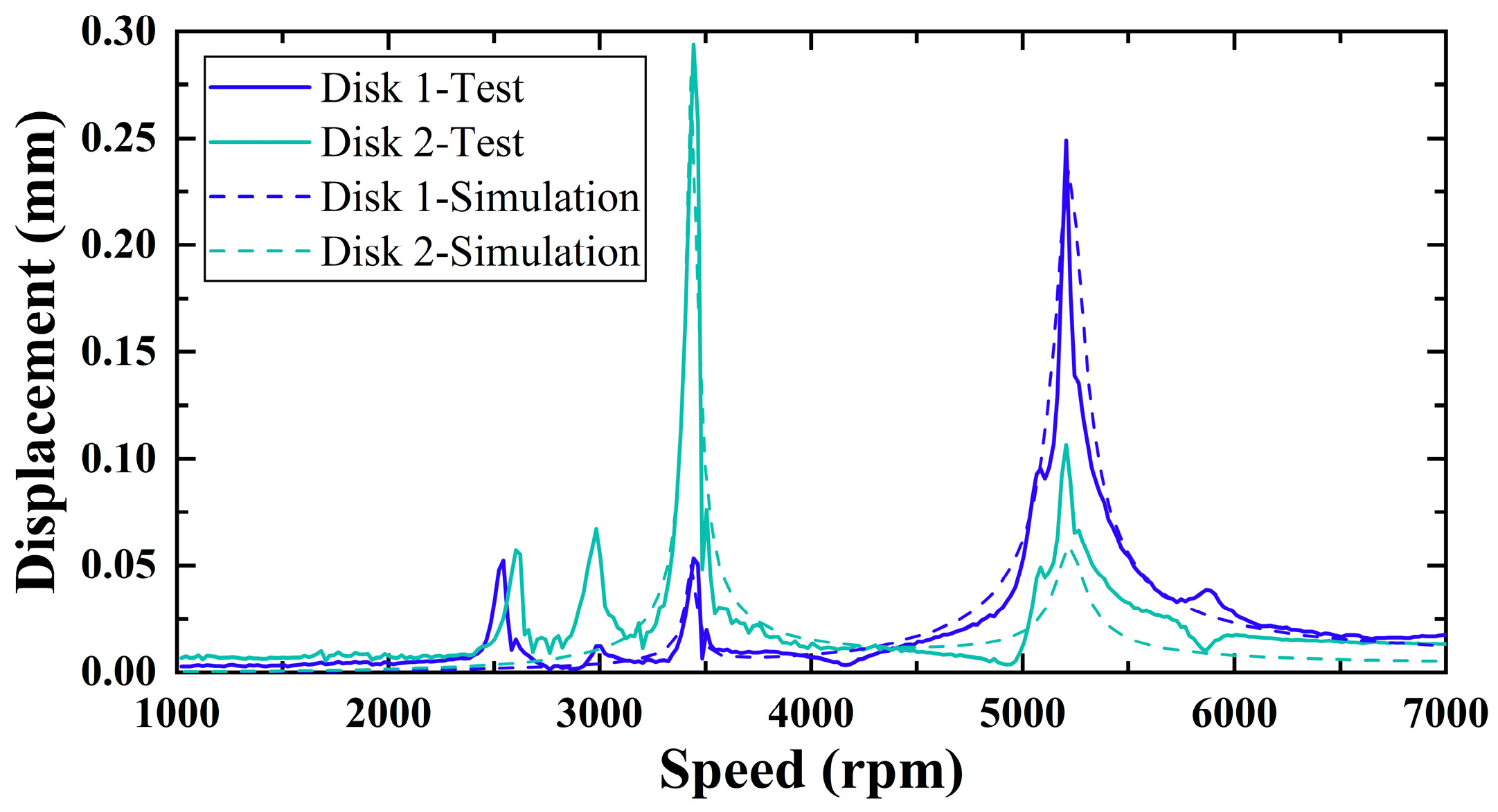

5. Experimental Verification

5.1. Experimental Test Rig Design and Instrumentation

5.2. Experimental Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heng, A.; Zhang, S.; Tan, A.C.C.; Mathew, J. Rotating Machinery Prognostics: State of the Art, Challenges and Opportunities. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2009, 23, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Sinou, J.-J.; Zhu, W.; Lu, K.; Yang, Y. A State-of-the-Art Review on Uncertainty Analysis of Rotor Systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 183, 109619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheli, F.; Cavalca, K.L.; Dedini, F.G.; Vania, A. Supporting Structure Effects on Rotating Machinery Vibrations; Medical Engineering Publications Ltd.: Glasgow, UK, 1992; Volume 6, p. 543. [Google Scholar]

- Oscar De Santiago, E.A. Rotordynamic Analysis of a Power Turbine Including Support Flexibility Effects. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2008: Power for Land, Sea, and Air, Berlin, Germany, 9–13 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Agrapart, Q.; Nyssen, F.; Lavazec, D.; Dufrénoy, P.; Batailly, A. Multi-Physics Numerical Simulation of an Experimentally Predicted Rubbing Event in Aircraft Engines. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 460, 114869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Lin, J.; He, Z.; Zuo, M.J. A Review on Empirical Mode Decomposition in Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machinery. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2013, 35, 108–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalca, K.L.; Cavalcante, P.F.; Okabe, E.P. An Investigation on the Influence of the Supporting Structure on the Dynamics of the Rotor System. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2005, 19, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.L.; Park, J.M. An Improved Rotor Model with Equivalent Dynamic Effects of the Support Structure. J. Sound Vib. 2001, 244, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyoti, K.; Sinha, A.W.L. The Estimation of Foundation Models of Flexible Machines. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference—Identification in Engineering Systems, Swansea, UK, 15–17 April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- De Felice, A.; Sorrentino, S. Frequency Analysis of Dynamic Systems Loaded by Both Parametric and External Excitations, with Application to Rotor Dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. 2025, 113, 20687–20710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, C.; Jiang, D.; Behdinan, K. Nonlinear Vibration Signatures for Localized Fault of Rolling Element Bearing in Rotor-Bearing-Casing System. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 173, 105449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabith, K.; Krishna, I.R.P. The Numerical Modeling of Rotor–Stator Rubbing in Rotating Machinery: A Comprehensive Review. Nonlinear Dyn. 2020, 101, 1317–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hong, J. Study on Dynamic Stiffness of Supporting Structure and its Influence on Vibration of Rotors. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2022, 35, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Luo, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Jiang, G.; Lu, L. Study on the Effect of Dynamic Stiffness of Supporting Structure on Dynamic Characteristics of the Rotor System. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2023, 237, 5273–5285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Luo, Z.; Li, L.; Ma, T.; Li, H. Numerical and Experimental Analysis of the Influence of Elastic Supports on Bearing-Rotor Systems. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Zhou, J.; Li, L.; Sun, K.; Li, H. An Analytical Method of Dynamic Stiffness of Combined Supporting Structure and Its Effects on Rotor Systems: Simulation and Experiment. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2024, 163, 104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Luo, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhou, J. Dynamic Stiffness Characteristics of Aero-Engine Elastic Support Structure and Its Effects on Rotor Systems: Mechanism and Numerical and Experimental Studies. Appl. Math. Mech. 2023, 44, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhao, C.; Ma, H.; Yu, K.; Wen, B. Rubbing Dynamic Characteristics of the Blisk-Casing System with Elastic Supports. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2019, 95, 105481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Ma, H.; Wen, B.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, Z.; Han, Q.; Wen, B. Dynamic Characteristics of Spindle-Bearing with Tilted Pedestal and Clearance fit. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 261, 108683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Wang, P.; Xiong, Q.; Ma, H.; Zhou, S.; Mu, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, Y. Modeling of Misaligned Bearing Induced by Coupling Misalignment and Assembly Errors and Vibration Analysis in Dual-Rotor System. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 230, 112656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, S.H.; Harsha, S.P.; Jain, S.C. Analysis of Nonlinear Phenomena in High Speed Ball Bearings Due to Radial Clearance and Unbalanced Rotor Effects. J. Vib. Control 2009, 16, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsha, S.P. Rolling Bearing Vibrations—The Effects of Surface Waviness and Radial Internal Clearance. Int. J. Comput. Methods Eng. Sci. Mech. 2006, 7, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Tohti, G.; He, H.; Geni, M. Study on the Dynamic Optimization and Design of a Flexible Rotationally Symmetric Tangential Support Plate Base. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehehalt, U.; Alber, O.; Markert, R.; Wegener, G. Experimental Observations on Rotor-to-Stator Contact. J. Sound Vib. 2019, 446, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipato, E.T.; Shaw, A.D.; Friswell, M.I.; Sánchez Crespo, R. Experimental Study of Rotor-Stator Contact Cycles. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 502, 116097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.O.T. On Stability of Rotordynamic Systems with Rotor–Stator Contact Interaction. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2008, 464, 3353–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, H.; Niu, H.; Song, R.; Wen, B. Nonlinear Dynamic Analysis of a Rotor-Bearing-Seal System under Two Loading Conditions. J. Sound Vib. 2013, 332, 6128–6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzad, M.; Alvandi, M. Unbalance-Induced Rub between Rotor and Compliant-Segmented Stator. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 429, 96–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Liang, X.; Li, J.; Wu, D.; Wang, F. Modeling Strategy and Mechanism Analysis for the Dual-Rotor-Disc-Bearing Coupled System with Unbalance Effect in Aeroengines. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fei, Q.; Wu, S.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, D. Nonlinear Vibration Response of a Complex Aeroengine under the Rubbing Fault. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 106, 1869–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, C.; Jiang, D. Prediction of Transient Vibration Response of Dual-Rotor-Blade-Casing System with Blade off. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng. 2019, 233, 5164–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Cheng, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Z. Nonlinear Dynamic Modeling and Transient Performance Evaluation of Dual-Rotor Aeroengine Support Systems. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 168, 110843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonisoli, E.; Venturini, S.; Cavallaro, S.P. Nonlinear Characterisation of a Rotor on Passive Magnetic Supports. Int. J. Mech. Control 2022, 23, 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- Chang-Jian, C.-W.; Chu, L.-M.; Chen, T.-C. Nonlinear Dynamic of Flexible Rotor Supported by Turbulent Bearings with Quadratic Damping and Temperature Dependent Viscosity. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2024, 16, 16878132241293957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Li, T.; Qu, S.; Huang, H.; Zhang, Z. Failure Analysis of Over-Temperature of Aero-Engine Bearing. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2023, 23, 1869–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Niu, L.; Xi, S.; Chen, X. Mechanical model development of rolling bearing-rotor systems: A review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 102, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breńkacz, Ł.; Witanowski, Ł.; Drosińska-Komor, M.; Szewczuk-Krypa, N. Research and Applications of Active Bearings: A State-of-the-Art Review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 151, 107423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, F.; Chen, Y. Nonlinear Vibrations of a Dual-Rotor-Bearing-Coupling Misalignment System with Blade-Casing Rubbing. J. Sound Vib. 2021, 497, 115948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrich, F.F. Observations of Nonlinear Phenomena in Rotordynamics. J. Syst. Des. Dyn. 2008, 2, 641–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yang, Z.; Hong, J.; Wang, D.; Cheng, R.; Ma, Y. Vibration Analysis of Rotor Systems with Bearing Clearance Using a Novel Conformal Contact Model. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 7951–7976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.Y.; Wang, P.F.; Ma, H.; Yang, Y.; Li, X.P.; Luo, Z.; Han, Q.K.; Wen, B.C. Dynamic Behaviors and Contact Characteristics of Ball Bearings in a Multi-Supported Rotor System under the Effects of 3D Clearance Fit. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 196, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, H.; Tang, K. A General Dynamic Model Coupled with EFEM and DBM of Rolling Bearing-Rotor System. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 134, 106322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xu, H.; Ma, H.; Han, H.; Yang, Y. Effects of Three Types of Bearing Misalignments on Dynamic Characteristics of Planetary Gear Set-Rotor System. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 169, 108736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Ma, H.; Luo, Z.; Han, Q.; Wen, B. Effects of Supporting Stiffness of Deep Groove Ball Bearings with Raceway Misalignment on Vibration Behaviors of a Gear-Rotor System. Mech. Mach. Theory 2022, 177, 105041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yang, Y.; Ma, H.; Luo, Z.; Li, X.; Han, Q.; Wen, B. Vibration Characteristics of Bearing-Rotor Systems with Inner Ring Dynamic Misalignment. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 230, 107536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huang, X.; Zheng, Z.; Ding, P.; Hao, J. Transient Characteristics of Misaligned Roller Bearing Considering Thermal-fluid-Solid Coupled. Tribol. Int. 2024, 196, 109693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hong, J.; Wang, D.; Ma, Y.; Cheng, R. Failure Analysis of an Aero-Engine Inter-Shaft Bearing Due to Clearance between the Outer Ring and Its Housing. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 150, 107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Liu, F.; Ma, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. Composite Failure Analysis of an Aero-Engine Inter-Shaft Bearing Inner Ring. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 165, 108707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Lv, J.; Tian, J.; Ai, Y.; Zhang, F.; Yao, Y. Modeling and Nonlinear Dynamic Characteristics Analysis of Fault Bearing Time-Varying Stiffness-Flexible Rotor Coupling System. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zeng, J.; Ma, H.; Zhao, C.; Yu, X.; Wen, B. A Dynamic Model for Simulating Rubbing between Blade and Flexible Casing. J. Sound Vib. 2020, 466, 115036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Li, S.; Du, S. Dynamic Reliability Analysis of Main Shaft Bearings in Wind Turbines. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2022, 235, 107721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, P.; Ambrósio, J.; Lankarani, H.M. Contact-Impact Events with Friction in Multibody Dynamics: Back to Basics. Mech. Mach. Theory 2023, 184, 105305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, R.; Ma, Y. Combination Resonances of Rotor Systems with Asymmetric Residual Preloads in Bolted Joints. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 183, 109626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Physical Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic modulus of the rotor and stator | 210 | GPa | |

| Density of the rotor and stator | 7900 | kg/m3 | |

| Poisson ratio of the rotor and stator | 0.3 | -- | |

| Length of the rotor and stator | 1058, 1205 | mm | |

| Position of Disk 1 and Disk 2 | 215, 945 | mm | |

| Position of the 1#, 2#, and 3# Support | 120, 310, 1020 | mm | |

| Length of the 1#, 2#, and 3# Frame | 75, 170, 200 | mm | |

| Length of Casing 1 and Casing 2 | 220, 540 | mm | |

| Outer and inner radius of the bearing seat | 65, 70 | mm | |

| Outer and inner radius of the casing | 115, 120 | mm | |

| Stiffness of the 1#, 2#, and 3# Support | 5, 8, 5 × 107 | N/m | |

| Mass of Disk 1 and Disk 2 | 10, 8 | kg | |

| Polar and diametral moment of inertia of Disk 1 | 0.06, 0.03 | kg·m2 | |

| Polar and diametral moment of inertia of Disk 2 | 0.04, 0.02 | kg·m2 |

| Physical Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outer and inner diameter | , | 80, 40 | mm |

| Outer and inner raceway diameter | 71.5, 49.5 | mm | |

| Number of the roller | 14 | -- | |

| Roller diameter | 11 | mm | |

| Effective length of the roller | 11 | mm | |

| Coefficient of profile | 0.00035 | -- | |

| Pitch diameter | 60.5 | mm | |

| Coefficient of contact stiffness | 1.12 × 1011 | N/m | |

| Clearance of the bearing | 0.2 | mm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Y.; Song, Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, C.; Ma, Y.; Hong, J. Research on the Dynamic Behavior of Rotor–Stator Systems Considering Bearing Clearance in Aeroengines. Actuators 2025, 14, 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120594

Ma Y, Song Z, Yang Z, Li C, Ma Y, Hong J. Research on the Dynamic Behavior of Rotor–Stator Systems Considering Bearing Clearance in Aeroengines. Actuators. 2025; 14(12):594. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120594

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Yongbo, Zhihong Song, Zhefu Yang, Chao Li, Yanhong Ma, and Jie Hong. 2025. "Research on the Dynamic Behavior of Rotor–Stator Systems Considering Bearing Clearance in Aeroengines" Actuators 14, no. 12: 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120594

APA StyleMa, Y., Song, Z., Yang, Z., Li, C., Ma, Y., & Hong, J. (2025). Research on the Dynamic Behavior of Rotor–Stator Systems Considering Bearing Clearance in Aeroengines. Actuators, 14(12), 594. https://doi.org/10.3390/act14120594